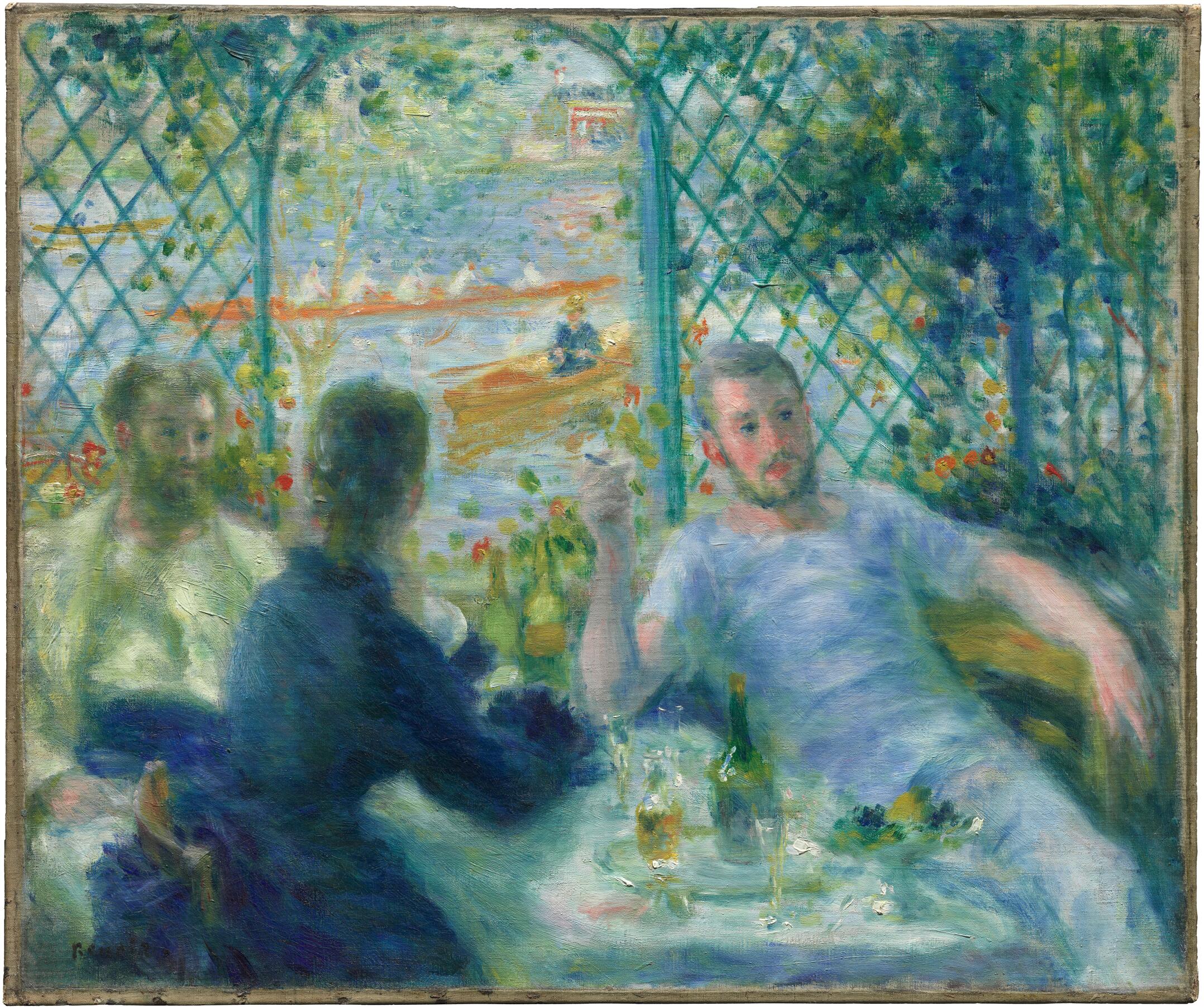

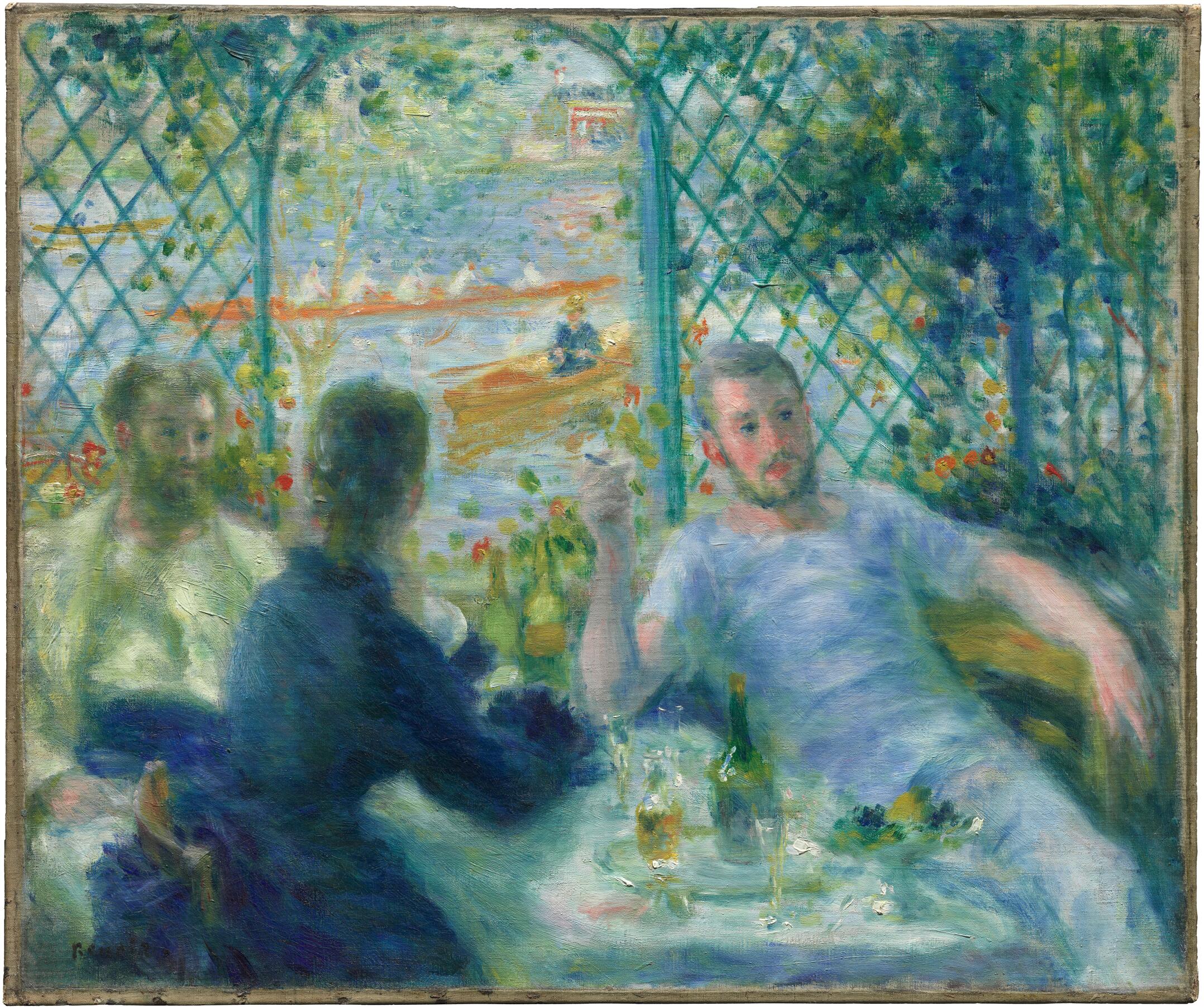

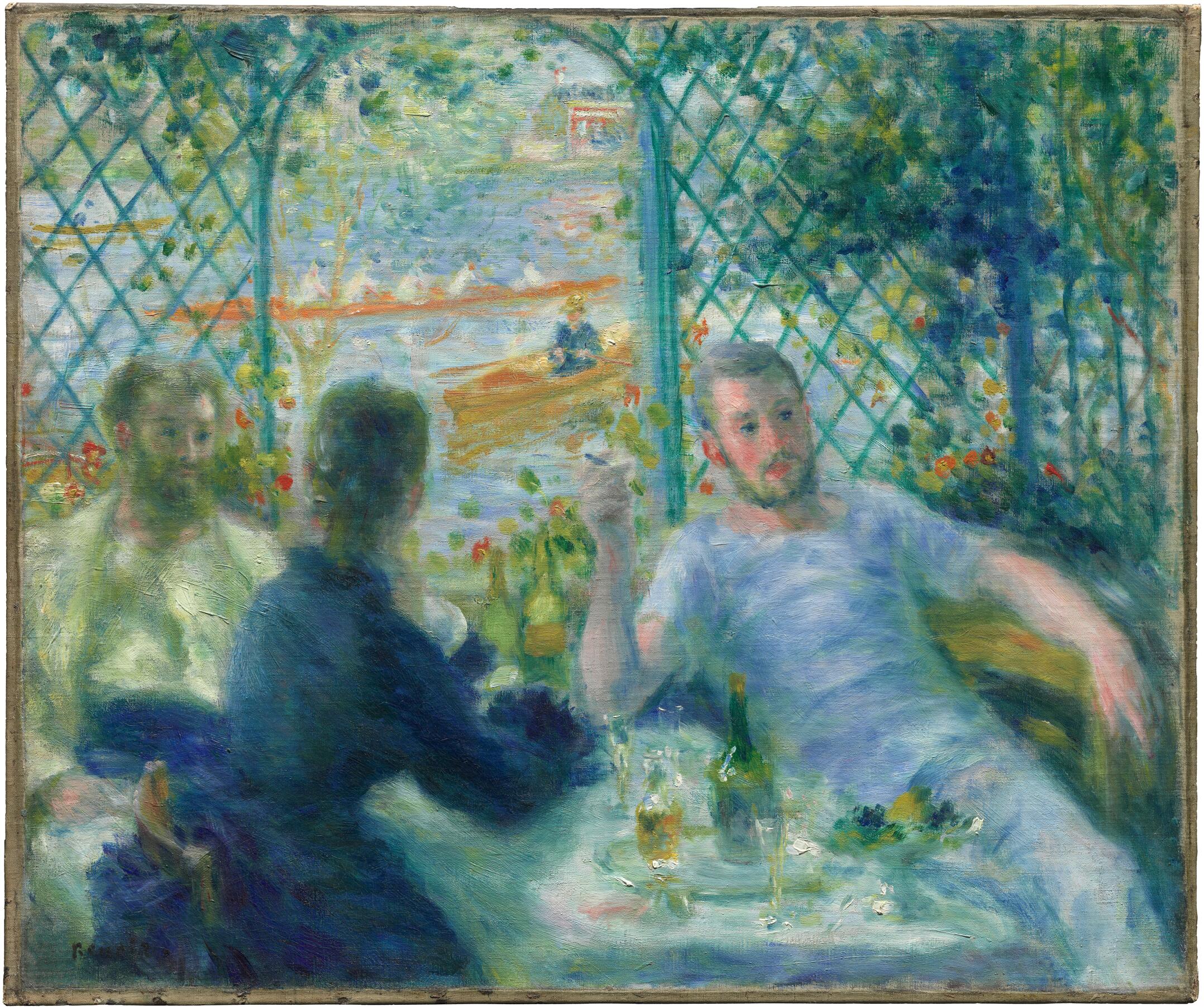

Cat. 2

Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise (The Rowers’ Lunch)

1875

Oil on canvas; 55 × 65.9 cm (21 5/8 × 25 15/16 in.)

Signed: Renoir. (lower left, in warm-black paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection, 1922.437

The Dating of Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise and Renoir at Chatou

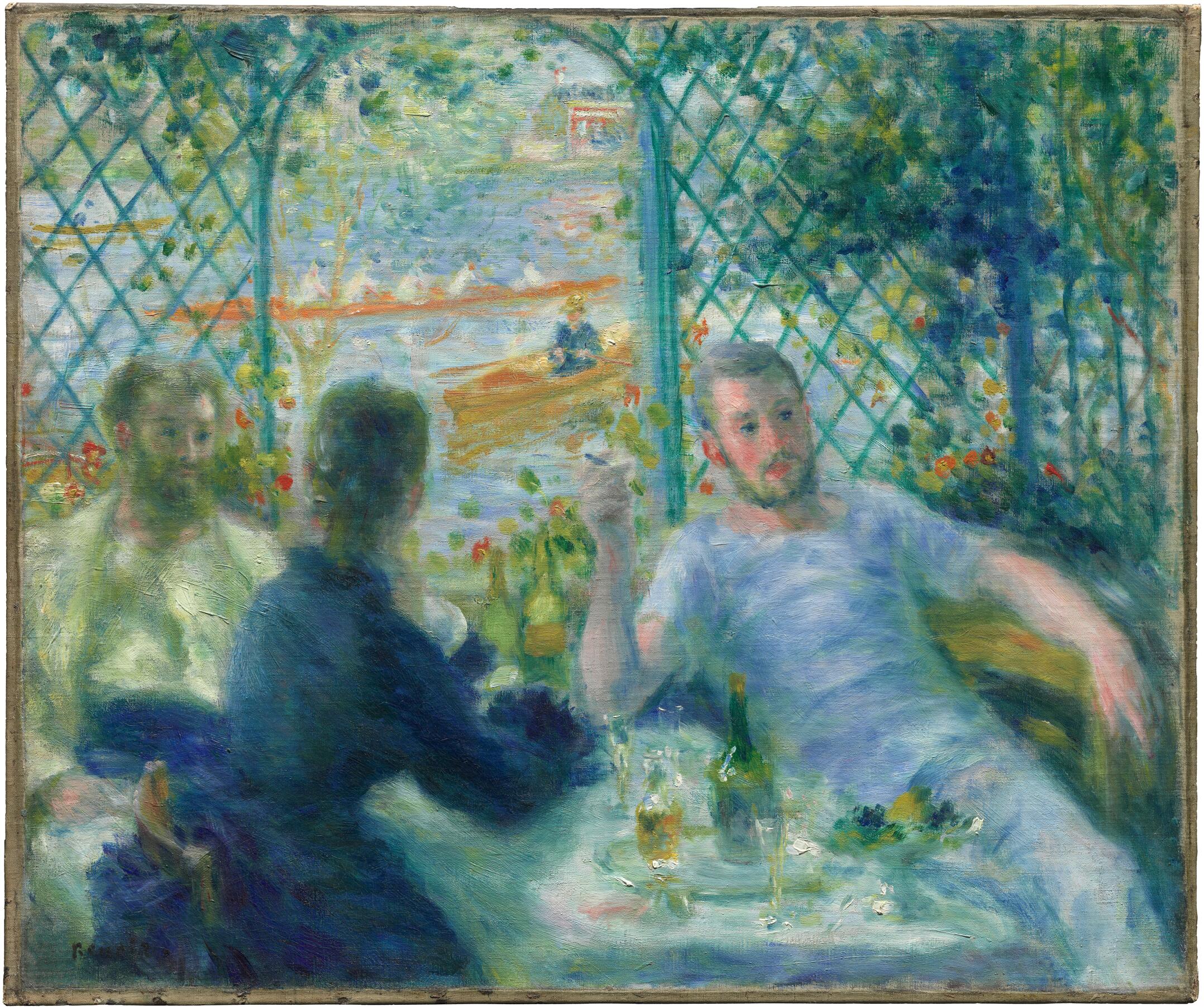

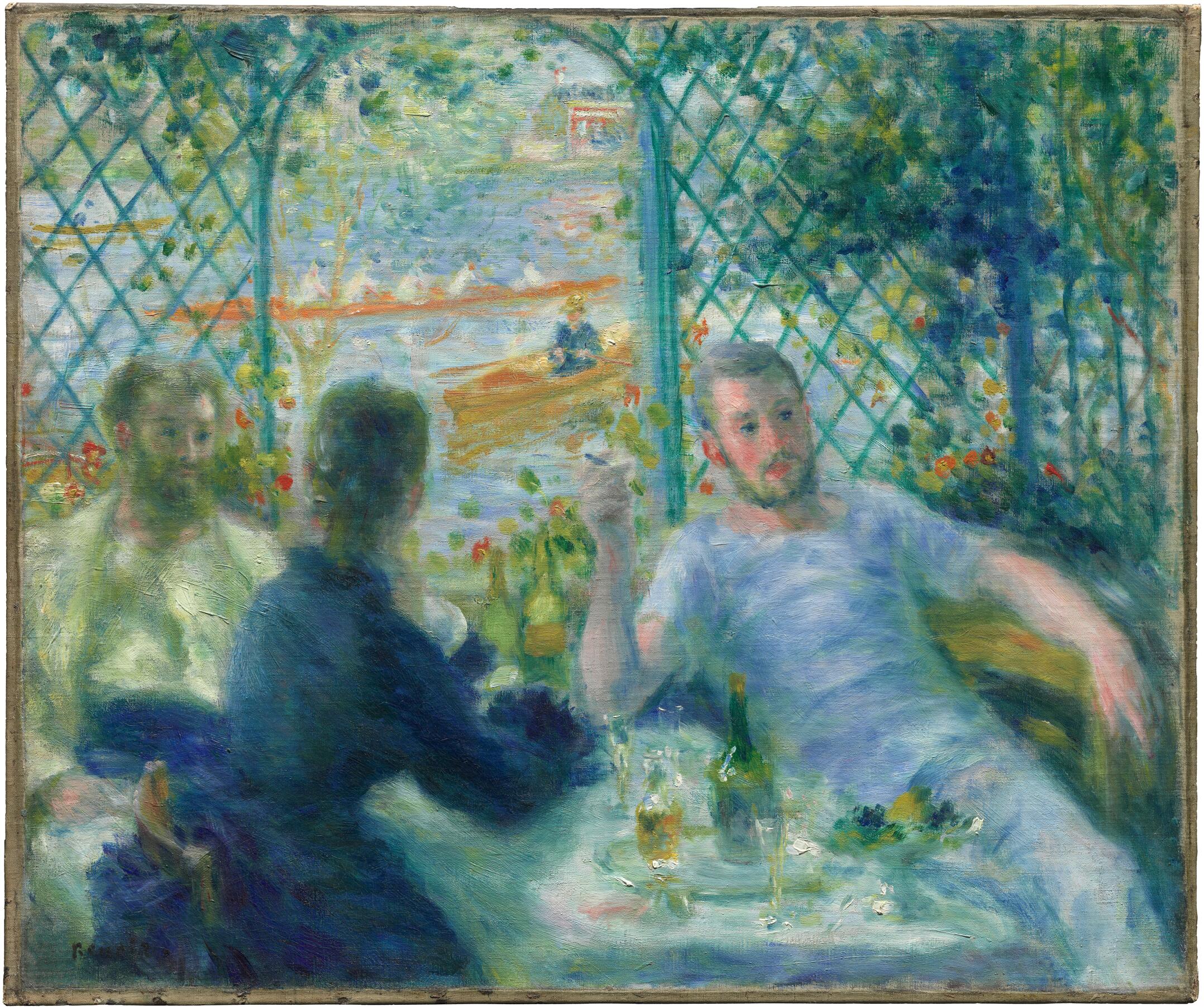

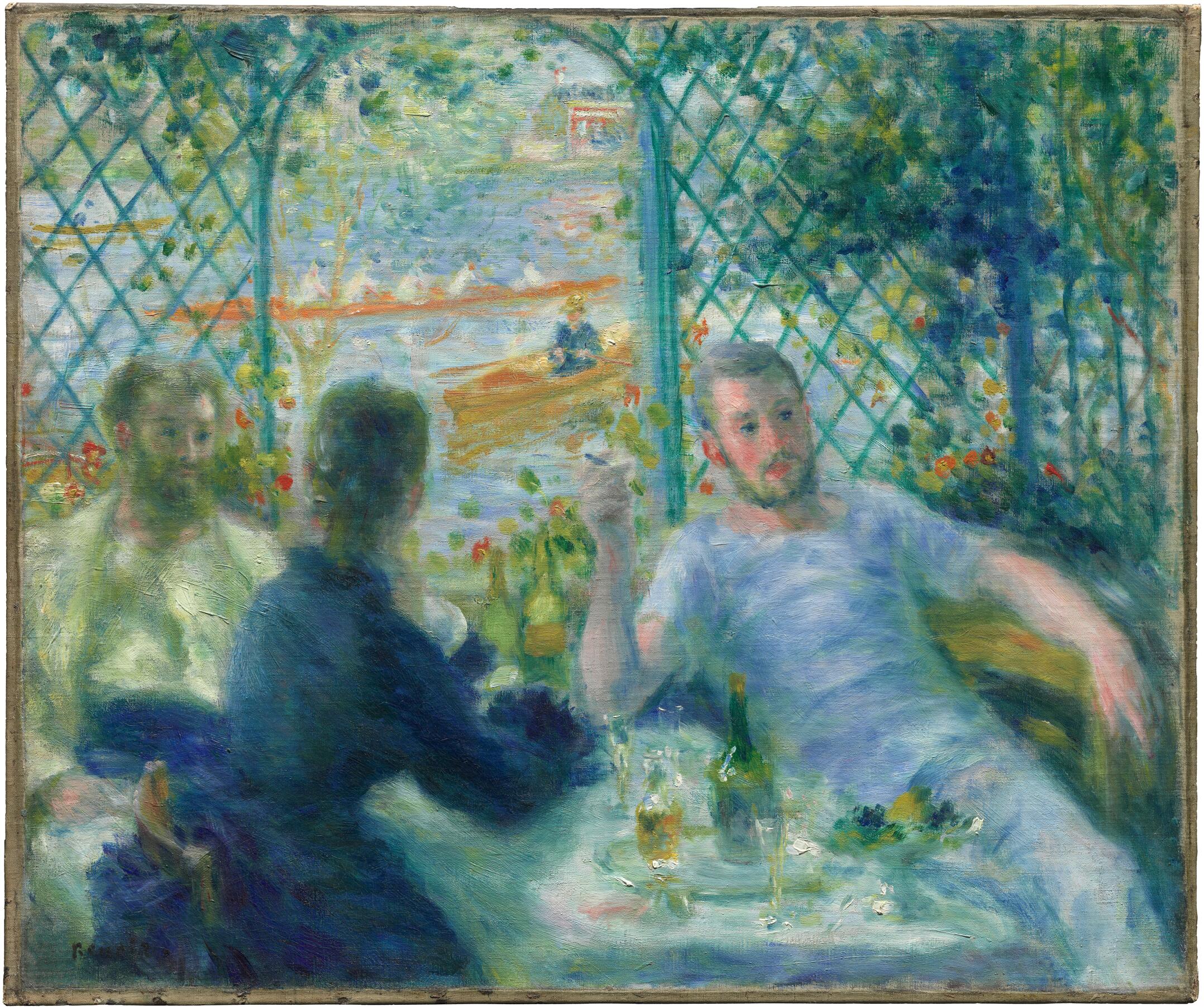

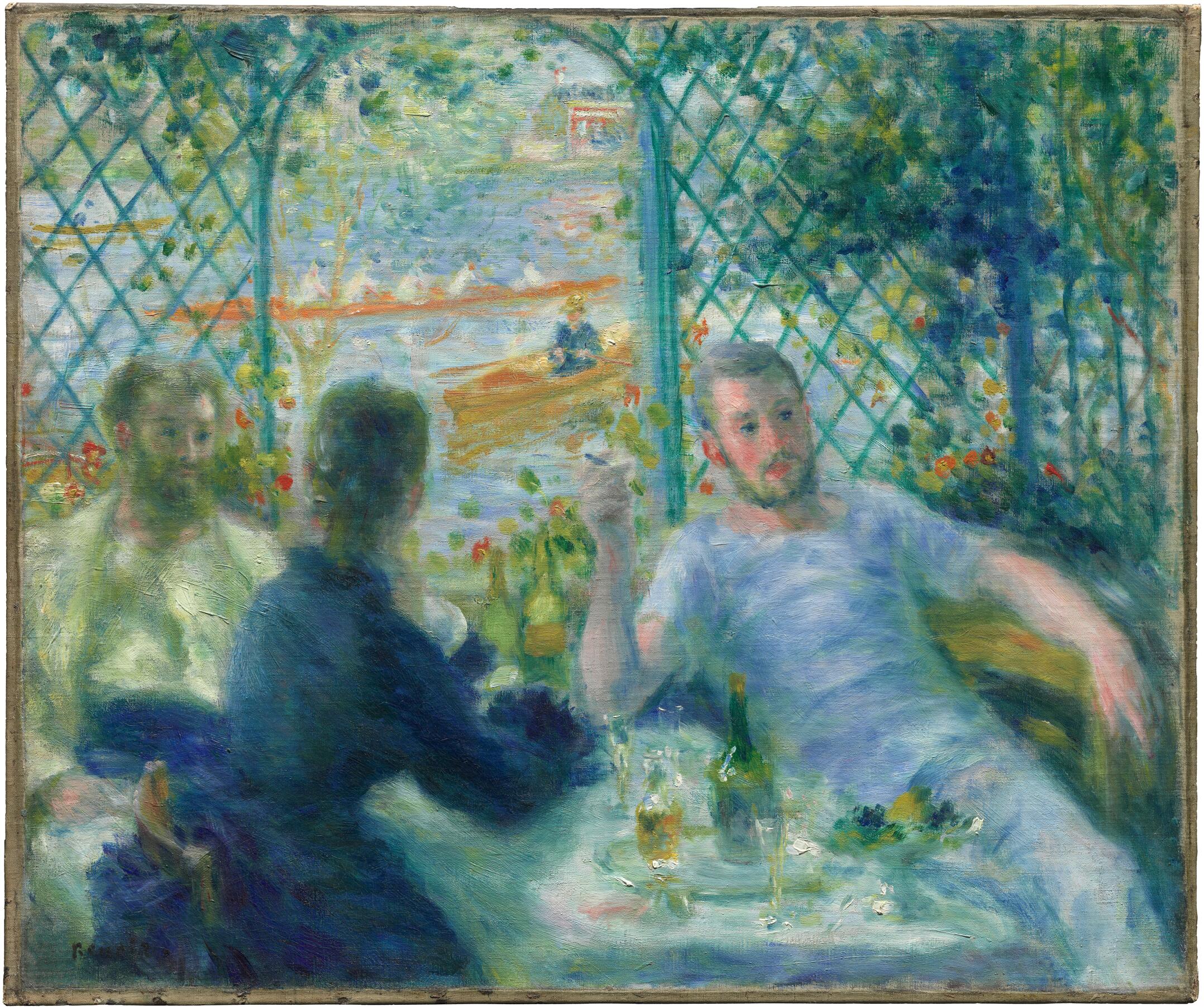

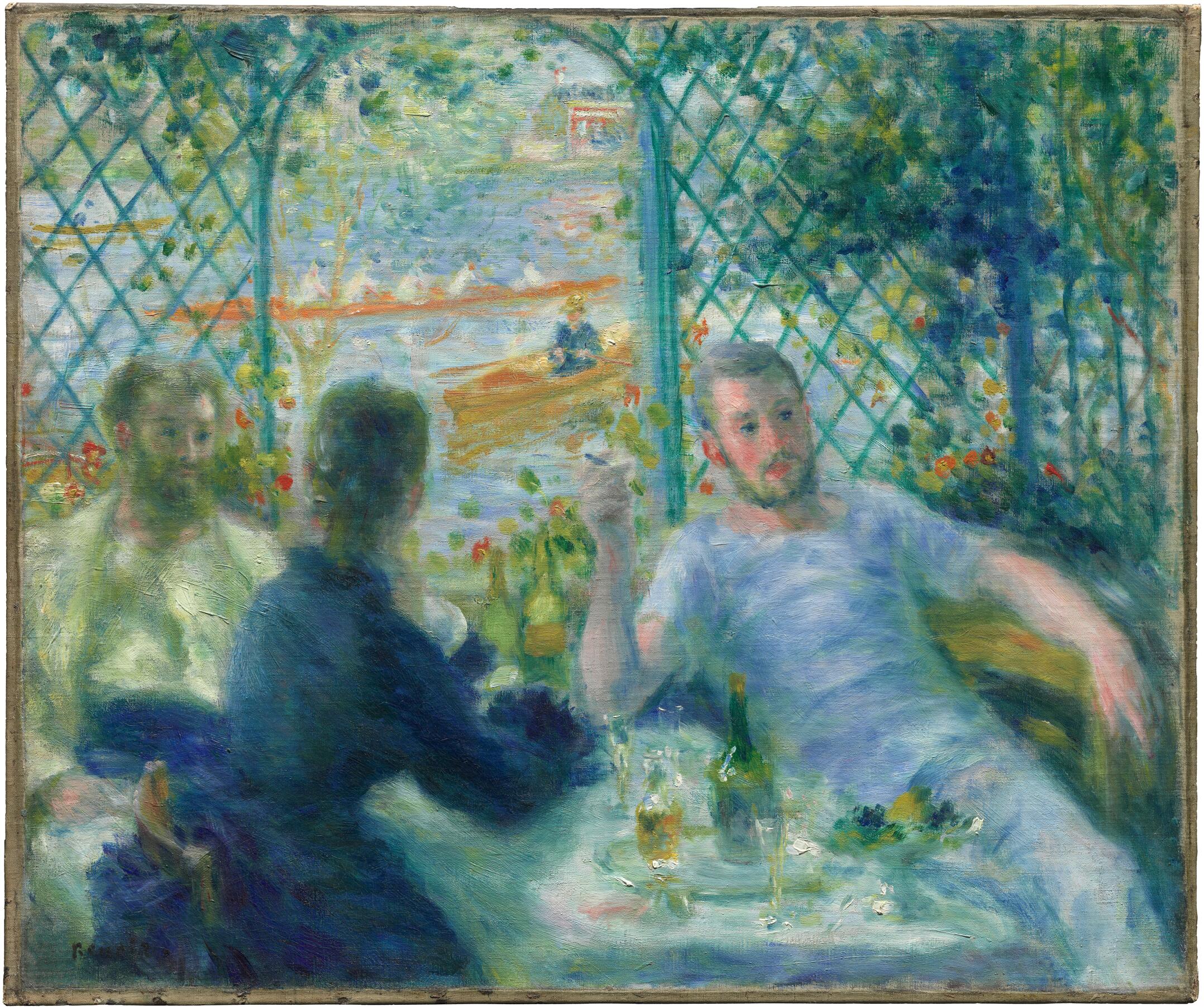

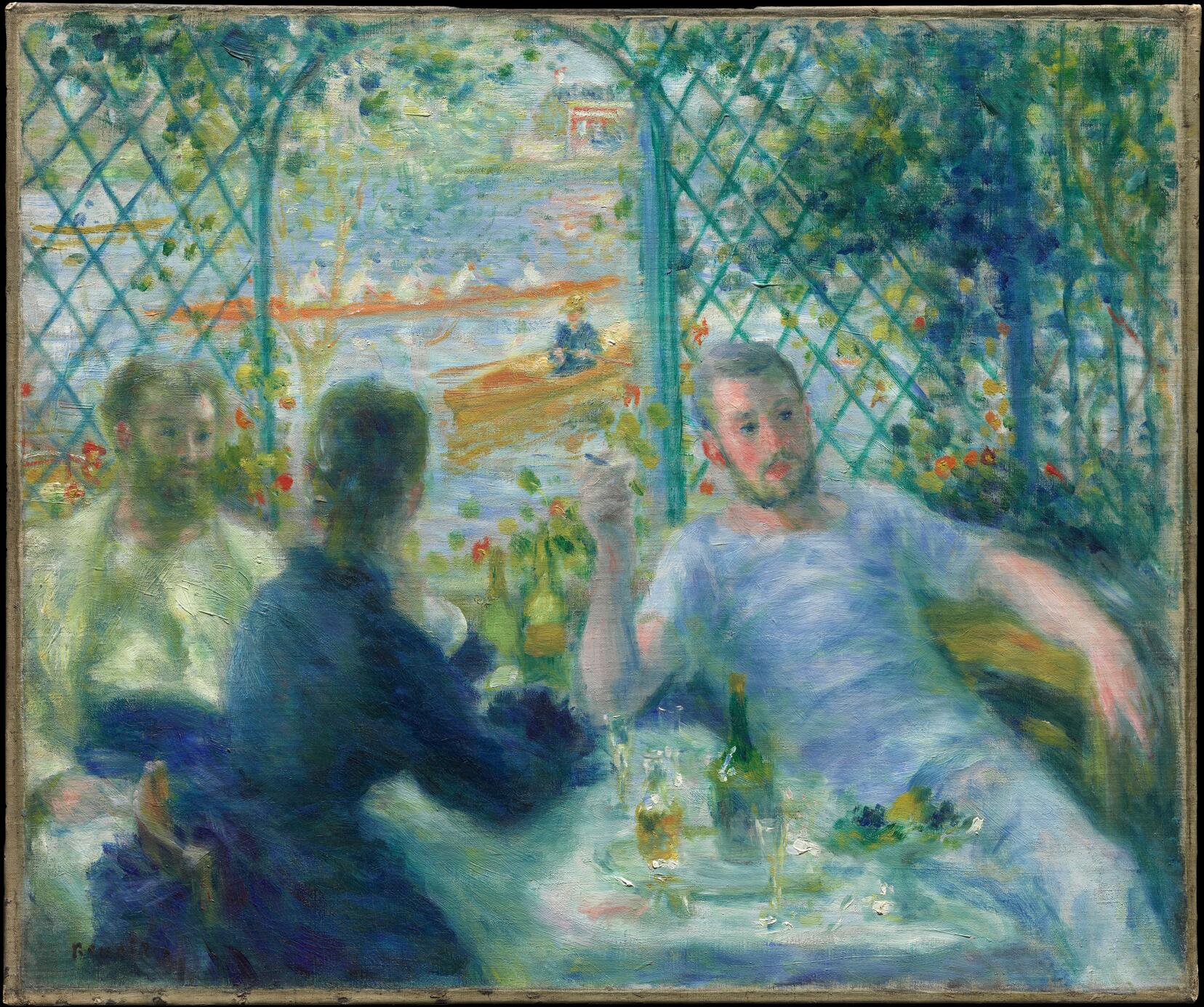

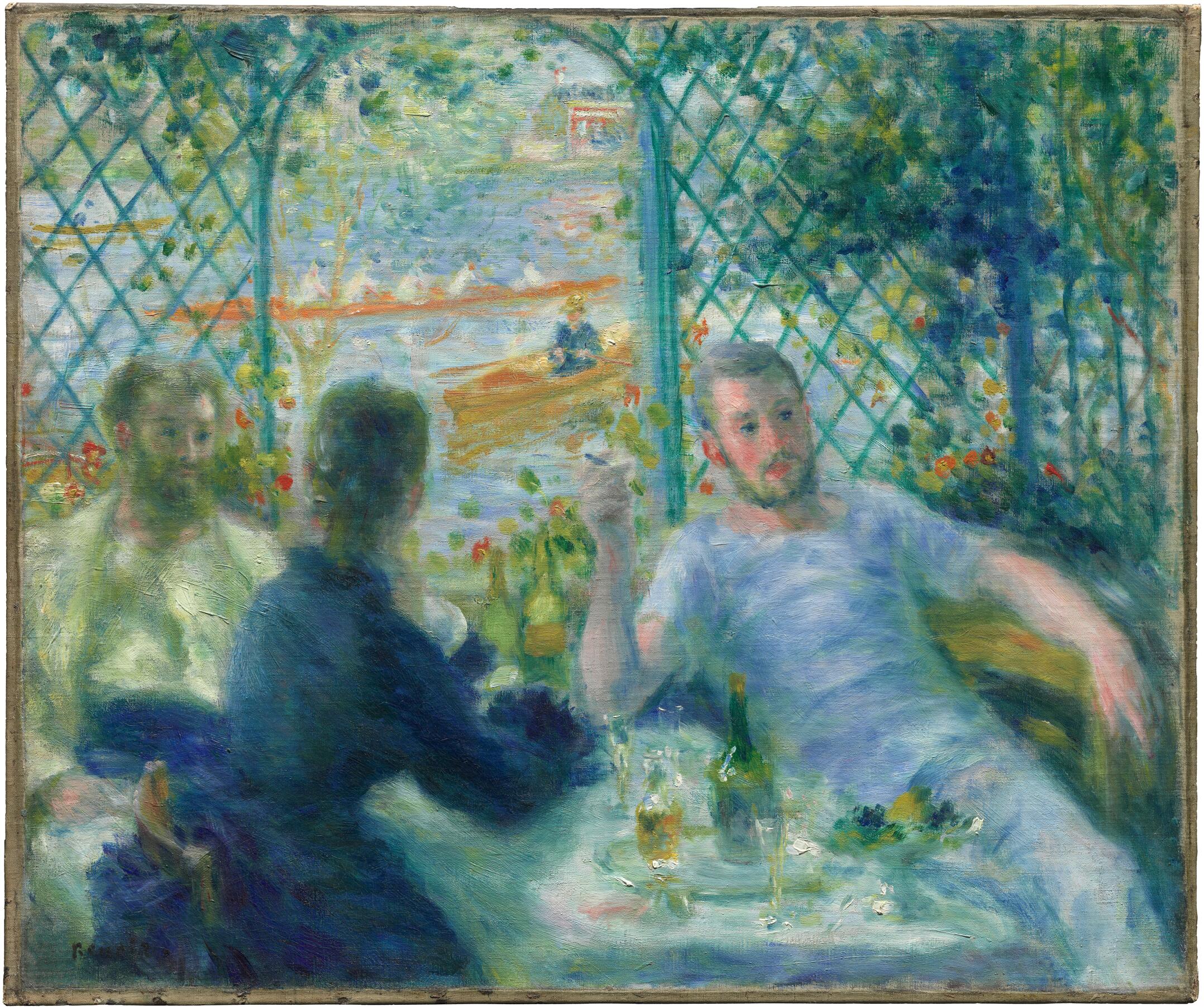

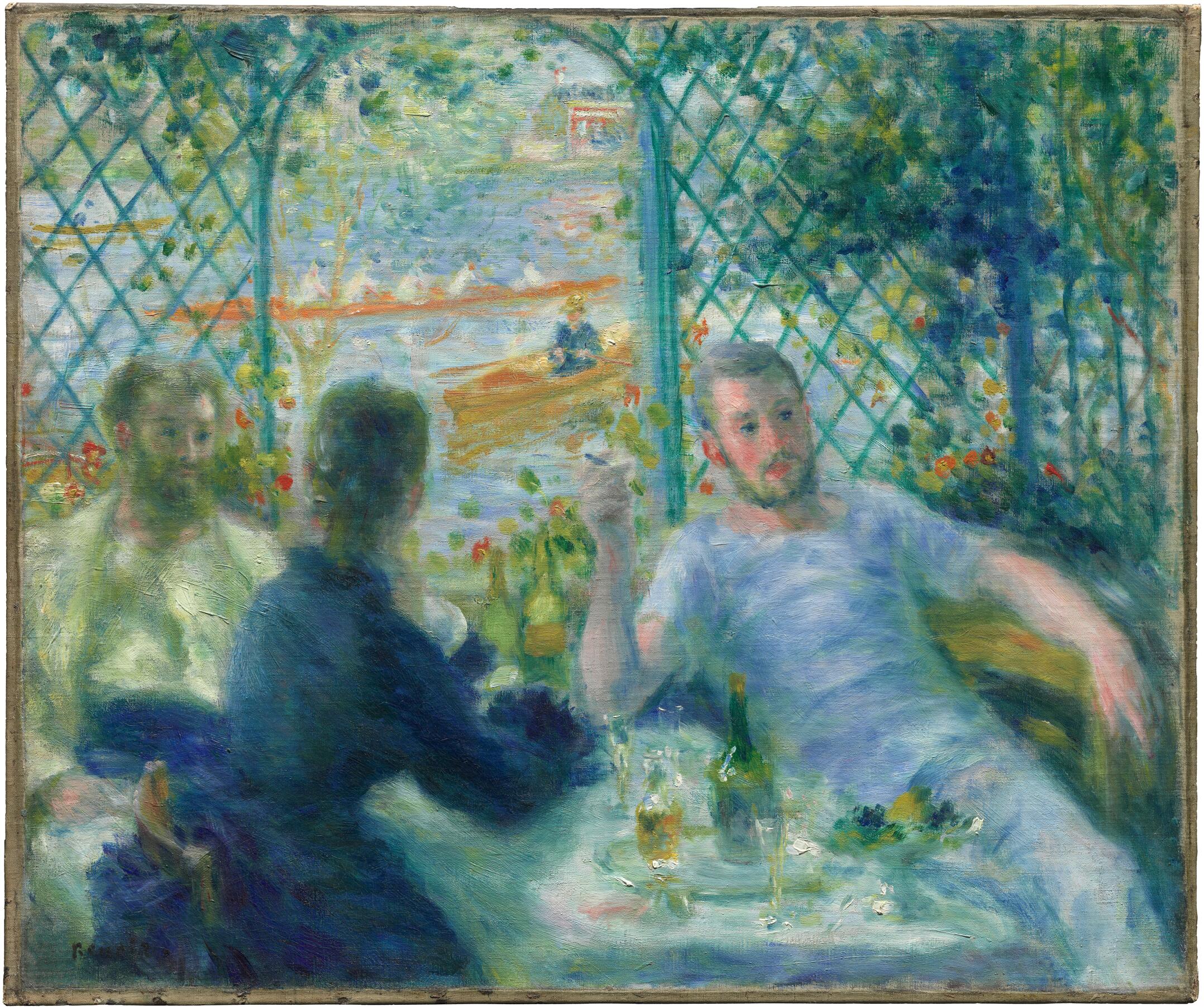

In this painting, Renoir shows a group of boaters—two oarsmen and a female companion (dressed for the water in blue flannel)—relishing an alfresco lunch. Bottles on a silver tray, fluted wine glasses, and a compote of fruit have been offered for their enjoyment on an astute white tablecloth. Judging from the bustle of boating traffic in the background, this is only one of many such groups that took to the waters of the Seine on a summer day, but Renoir transformed this commonplace scene into an idyllic episode of sensuality and pleasure. Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise was sold to Potter Palmer by Durand-Ruel, New York, on April 9, 1892, with the title Déjeuner de canotiers, just weeks before the May 1 opening of Renoir’s retrospective at the Durand-Ruel in Paris, which included the renowned scene of a boating luncheon along the Seine painted between 1880 and 1881, now in the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. (fig. 2.1 [Daulte 379; Dauberville 224]). In the catalogue that accompanied the retrospective, the Washington work was given the erroneous title Déjeuner à Bougival. Both the Chicago and Washington paintings, however, are set in the restaurant of the Maison Fournaise (fig. 2.2), located on what was then known as the Île du Chiard in the Seine, part of the municipality of Chatou, about one mile farther upriver and north of Bougival. The relationship of subject and site that the two paintings share determined for decades the dating of Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise to 1879. The earlier date of 1875 came to light in 1986, when the Chicago work was identified as that included in the second Impressionist exhibition held in April 1876. An astute connection was made between the catalogue title Déjeuner chez Fournaise and the snide though accurate description of it as “Tonnelle des Canotiers sans jambes” by the critic of Le soleil.

With the new dating, Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise can be placed with a group of paintings thought to be executed during Renoir’s extended stay at the Maison Fournaise in the summer of 1875, which opened an important chapter in his portrayal of boating along the Seine. The other paintings include an interior luncheon or breakfast (fig. 2.3); at least two landscapes, one of a rowing subject (fig. 2.4 [Dauberville 141]) and another showing the nearby bridge at Chatou (Dauberville 136); and portraits of the proprietor of the restaurant, Alphonse Fournaise (fig. 2.5) and his daughter Alphonsine, both of which are dated and share the loose, flowing brushwork that characterizes Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise. Why Renoir was drawn to the Maison Fournaise in the summer of 1875 remains a mystery, as he was no doubt aware of its local fame as a destination for boat rental before that time. His parents lived in Louveciennes just downriver, near Bougival, and he had been painting in the area since the mid-1860s, most significantly in the summer of 1869 at La Grenouillère on the Île de Croissy, where he and Claude Monet completed plein air sketches of visitors and moored boats at the popular restaurant and bathing establishment in preparation for the Salon of 1870. Renoir’s interest in the Fournaise establishment came to an end as abruptly as it began. After 1881 he produced no further paintings with Chatou subjects, and his letter to Théodore Duret on Easter Monday of that year, during the execution of Two Sisters (On the Terrace) (cat. 11), was written during his last recorded stay in the town. The restaurant and hotel would continue to thrive for many years, gaining celebrity in a short story by Guy de Maupassant as the Restaurant Grillon, a “stronghold of canotiers.”

Renoir and the Boating Theme

Renoir’s earliest depictions of leisure boating date to the 1860s and recall the paintings of Eugène Boudin and Gustave Courbet. In addition to peopling the landscape views of La Grenouillère in 1869 mentioned above, boaters continued to appear elliptically in such works as La promenade (fig. 2.6 [Daulte 55; Dauberville 257]), in which the male protagonist wears a boater’s straw hat decorated with red ribbon, and Bather with a Griffon Dog (fig. 2.7 [Daulte 54; Dauberville 596]), a classically posed scene of modern life that Renoir exhibited at the Salon of 1870, depicting two women who arrived at their secluded bathing spot by rowboat. Renoir also took a personal interest in rowing, boating, and regattas, a passion he shared with his Impressionist colleagues. In July 1865 he sailed down the Seine with Alfred Sisley’s brother, Henri, and a model from Édouard Manet’s studio to see the regattas at Le Havre, taking his paint box to make sketches along the way. Renoir wrote enthusiastically to his friend the artist Frédéric Bazille to join them in the adventure.

Renoir’s work alongside Monet on the shores of the Seine at Argenteuil during the summer of 1874 apparently rekindled his interest in depicting leisure life along the river and boating subjects. On July 22 Renoir and Monet were joined by Manet, who was summering across the river at Petit-Gennevilliers and also painted a number of pictures of boaters that summer. Manet sent one of these, an explicitly Impressionist work with a bright palette depicting a boater and his female companion sitting by the docks, titled Argenteuil (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tournai), to the Salon in May 1875. It received a lukewarm reception and was caricatured several times in the satiric journal Charivari. One caricature claimed that the pair of boaters had clearly run aground.

Thus Renoir’s decision to paint at the Restaurant Fournaise in the summer of 1875 was likely informed by his experience the previous summer on the banks of the Seine at Argenteuil and by Manet’s recent attempt to bring Impressionism to the Salon with a boating theme. The question for Renoir was how to make the theme his own: how to break free of Monet’s predominantly landscape example, how to be a figure painter and create a genre scene based in reality but open to broader readings of idyllic leisure. At Fournaise he found ideal subject matter and willing models. Fournaise was a family-run establishment with a long history in the community that attracted a serious sporting clientele, artists, and members of the Parisian theater world, as well as the odd aristocrat seeking the outdoor experience (who was invariably out of place). Its Parisian equivalent was the Moulin de la Galette, the Montmartre dance hall. As Renoir’s close friend and biographer Georges Rivière later commented, “The exuberant rowers and the grisettes who accompanied them resembled the young folk and dancers of Moulin de la Galette; the infectious gaiety of this carefree crowd, boastful without arrogance and mocking without malice, attracted the painter, for whom the spectacle of popular enjoyments had always been of interest.”

The subjects of boating and dancing shared an association with youthful bohemia and student life during the July Monarchy and inspired many treatments in popular culture, such as vaudeville theater, as early as 1845 (fig. 2.8). Before the expansion of the city during the Second Empire and the extension of the railway in the 1840s and 1850s, Parisians boated for pleasure at Bercy, on the east side of Paris near the current location of the finance ministry (fig. 2.9). Boating at Chatou became popular after the area was made accessible by rail and the land was acquired for commercial development by boatbuilder Alphonse Fournaise in 1857. The terrace upon which Renoir’s models sit for the Washington Luncheon of the Boating Party dates from 1867, when a Neoclassical, two-story, red-brick structure was constructed as a restaurant, a function it still serves today. Judging from the point of view of the Chicago Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise, the tonnelles or arbors were on the first floor under this terrace.

Renoir’s Models and Boating Fashion

As with many of Renoir’s genre paintings inspired by popular pastimes, the models for Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise were drawn from his immediate circle of acquaintances and may very well have been habitués of the place in which they are shown. The sunburned figure in the white shirt on the right has never been identified but may have been inspired by Renoir’s younger brother, the journalist Edmond Renoir, who served frequently as a model for his brother during the 1870s (fig. 2.10 [Daulte 319; Dauberville 554]). In a series of articles promoting the leisurely pleasures of Bougival and its environs, written for La vie moderne in 1883, Edmond wrote perceptively of boating on the Seine and insisted on extending his survey to Chatou and the Restaurant Fournaise because it reflected the “same world, same joviality, same insouciance.” The fact that the figure is sunburned suggests an intentional light mockery of the city dilettante who has forgotten his hat—license that one would expect a sibling of the modern family to take.

François Daulte first identified the figure on the left with the distinctive fan beard as “Monsieur de Lauradour,” a regular at La Grenouillère and the Restaurant Fournaise. This model appears in three closely dated Renoir paintings, including a bust portrait (The Rower of Bougival, c. 1876; Kunstmuseum Basel) in the same stipple technique used by the artist in Alfred Sisley (1876; cat. 4). Although the nature of their relationship is unclear, Renoir must have been on friendly terms with Lauradour, as at this time he rarely painted portraits of men he did not know. The third painting in which Lauradour appears is the Luncheon in the Barnes Collection (fig. 2.3), which is almost certainly an indoor scene set at the Restaurant Fournaise during a cooler time of day, as the woman in the picture wears the same blue dress, but under a white jacket.

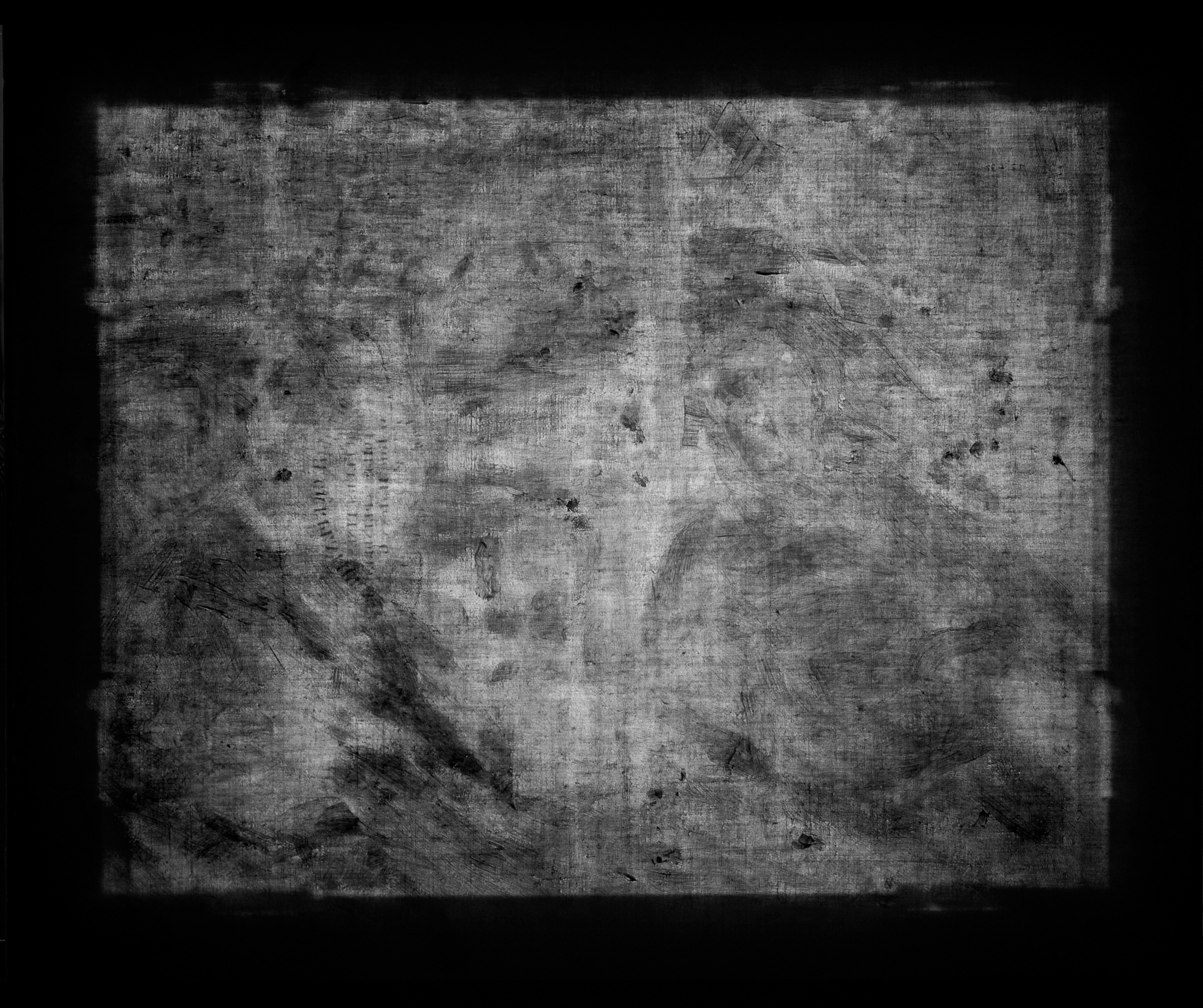

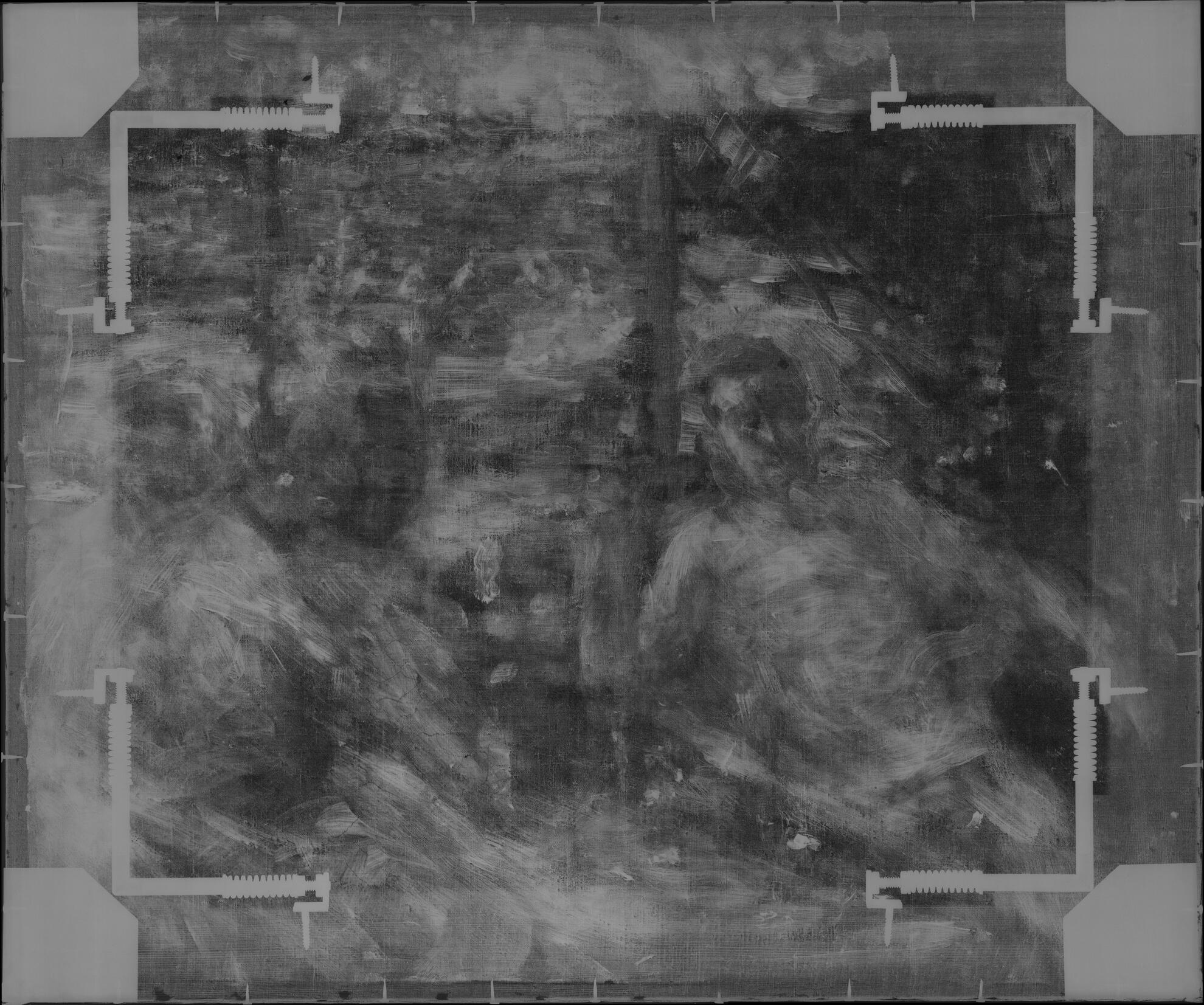

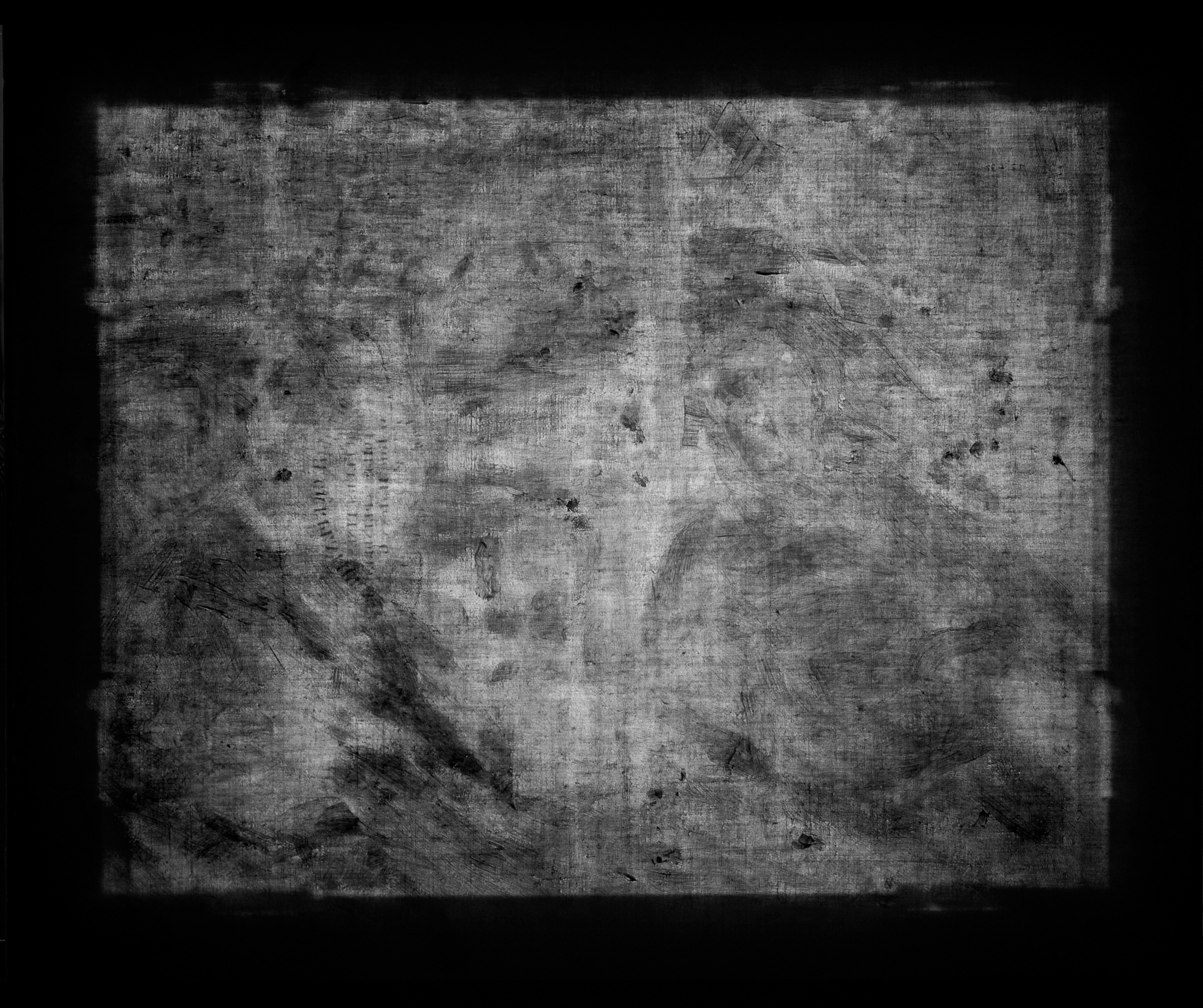

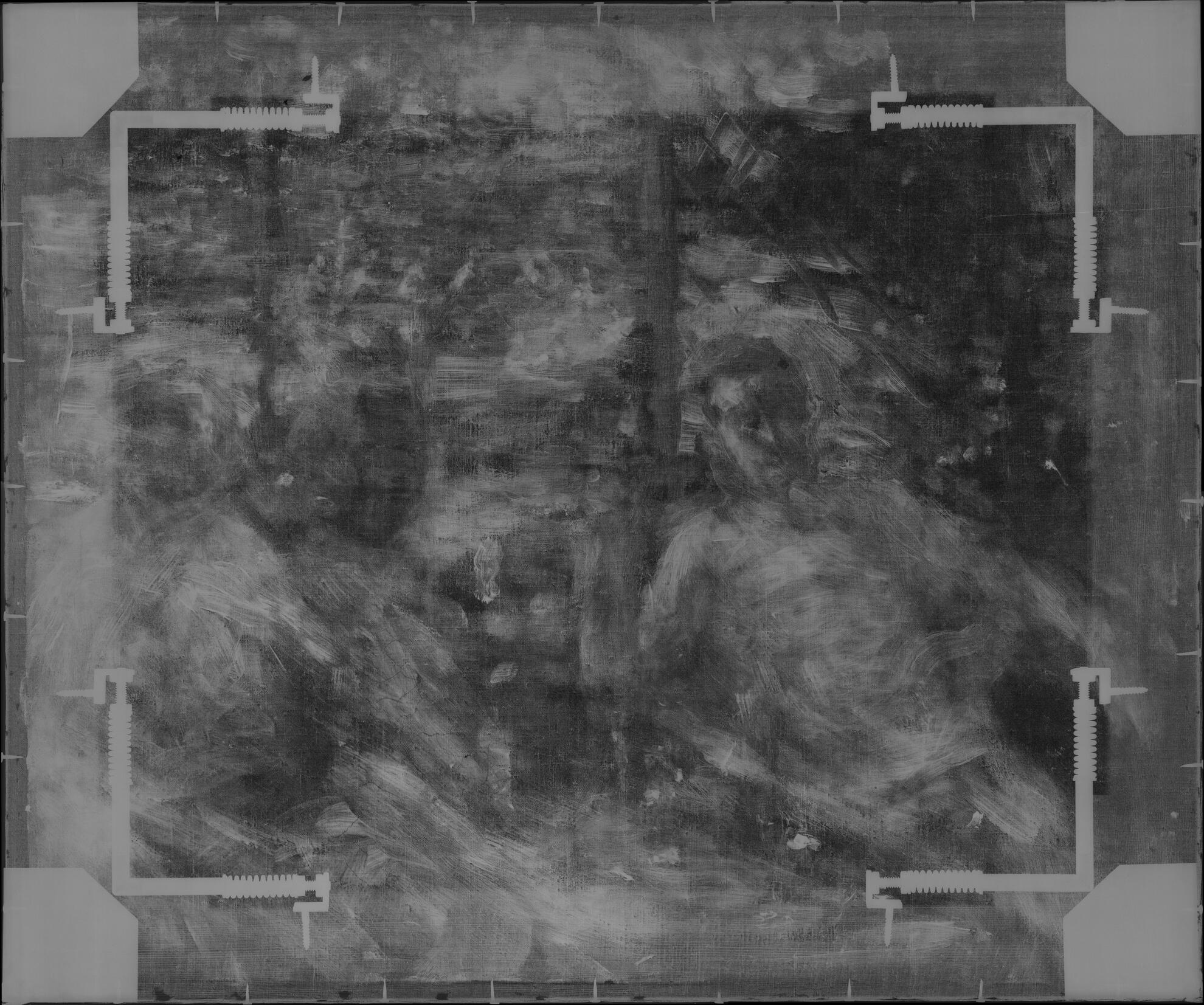

That Renoir used the same two models for a complementary theme raises the question of whether the Barnes Luncheon and Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise were conceived as pendants. Luncheon of the Boating Party is slightly smaller but shares a horizontal format. Significant changes to the number and position of the figures in Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise suggest that Renoir may have originally intended to include only two people, a male and a female, as in the Barnes Luncheon. Visible in the [glossary:X-ray] (fig. 2.11) is what seems to be the outline of a figure in profile; the shape of the head suggests a woman with her hair pulled up off her neck. Renoir was able to accommodate a second male with his final placement of the female closer to the center of the painting. He thus established a pyramidal arrangement with the woman resting her elbow on the table and the relaxed, smoking oarsman on the right. The pose of the seated figures, together with the perspectival lines of the table, acts to carry the eye diagonally toward a sun-filled river playground, resulting in a superbly balanced composition.

The comparison of Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise with contemporary caricature reveals that Renoir followed up-to-date trends in sport fashion. Both male models may be identified as rowers by their white costume and the rowboats seen on the river through the trellis. A woman in a skiff near the shoreline wears a blue flannel dress that matches the one worn by the female figure seated at the table. In J. Pelcoq’s satiric image of boaters modeling their clothes for the Journal amusant in 1875, a number of male and female costumes for nautical outings are displayed, such as the collarless shirt with buttons and the sleeveless shirt for men, and the half-length jacket for women (fig. 2.12). A more distinguished “outdoor gentleman’s” look “à l’anglaise,” as suggested by the caption, is modeled by the man wearing a dark jacket, wide-collared shirt with lavaliere, and visored cap. Around his waist this figure sports what appears to be a sash. In Renoir’s painting, Lauradour is portrayed in a combination of these fashions, including the collarless shirt, white jacket, and blue sash. Renoir’s bust portrait of Lauradour shows him to be as meticulous about the stylish trim of his moustache and beard as any of the sportsmen in Pelcoq’s illustration. It is worth noting that on the bank to the right of this scene of boaters sits a woman dressed in a jacket and pants—an outfit that would better accommodate outdoor physical activity.

Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise as a Bold Step Forward in Renoir’s Use of Color

In this relatively small canvas—a no. 15 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size canvas turned horizontally to become a landscape format—Renoir indulged his predilection for pure color. In a remarkably audacious move for the mid-1870s, the artist limited his palette to emphasize the primary colors (see Technical Report). Most distinctive in this regard is the contrasting treatment of the two male boaters. The folds and shadows in the shirt of the smoking figure on the right are rendered in cool blue tones, whereas the trim of Lauradour’s jacket and shirt is entirely yellow. The hair color of the two men is consistent with this yellow/blue color distinction (fig. 2.13). Yellow highlights are found throughout the painting, from the tablecloth and glassware to the flowers, the tree by the water, and the opposite shoreline. Generous application of lead white paint in the men’s shirts, the tablecloth, and the surface of the river behind them contributes to the striking luminosity of the scene (see Palette in the Technical Report). The brushwork of the shirt on the right (fig. 2.14) can be compared to that of the white shirt in the portrait of Alphonse Fournaise (fig. 2.5), in which a flat brush was used to apply the paint and model the folds of the sleeves. In this bold display of color, the blue of the woman’s dress acts as a neutral tone to anchor the composition, while yellow and white encourage movement of the eye over the picture plane.

The abrupt vertical of the trellis, with its flowering vine, divides interior from exterior, relaxation from physical activity—especially the focused task of navigating a boat. The riverscape in the background here functions to keep the active life of water sports at a distance from the main action of a contemplative smoke and casual conversation over an outdoor meal during summer. What we see in the considered composition and execution of Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise, though based in observed reality of a popular nineteenth-century pastime, has more to do with memory and ideals, with a peaceful utopian existence as envisioned by the artist. Robert Herbert has noted that Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise “has the air of a fable,” while Richard Brettell has likened it to the fêtes galantes of Jean-Antoine Watteau. This is not the place to address the degree to which eighteenth-century art influenced Renoir’s development of the modern genre subject, with its youthful cast of characters in quiet conversation, whose mundane moment of leisure has been infused with a decided sensuality. But Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise suggests a renewed appreciation of the art of the ancien régime and a revisiting of the pastoral tradition through the eyes of an indefatigable colorist.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Renoir’s Lunch at the Restaurant Fournaise (The Rowers’ Lunch) was painted in several [glossary:wet-in-wet] campaigns and shows evidence of a number of compositional changes. The artist began with a [glossary:commercially primed], no. 15 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size [glossary:canvas] turned on its side, onto which he probably added a selective preparatory layer covering specific parts of the compositional area. This selective layer has a warmer hue and probably contains added [glossary:oil] medium, which allowed for minimum absorption of subsequent paint layers and provided a warm background off of which Renoir could play the cool colors of the background and water.

There are significant compositional changes in the left half of the composition. [glossary:X-ray] and raking-light images suggest that, in an earlier version of the painting, there was a figure situated in the space between the two individuals who appear on the left in the final composition. Summary [glossary:underdrawing] lines in a dry medium may be related to this figure’s head; additional lines seem to indicate the left side of the trellis opening and the outer curve of the far-left visible figure’s leg, but the nature of these lines is rather intermittent and haphazard. The left side of the original composition seems to have featured only this single figure painted in profile. Heavy brushwork under the far-left visible figure suggests additional changes before the artist executed the forward-facing male figure.

There are also some minor and partially developed alterations to the right side of the canvas. In the X-ray, a curvilinear form beginning just to the right of the figure and continuing through the torso and a second form just below it may suggest elements of the back of a chair. As these elements were abandoned in their early stages, it is unclear how this placement would have affected the posture of the male figure.

Renoir used a limited [glossary:palette], and many of the hues were mixed on the surface of the painting. Instead of carefully blending mixtures before dabbing them onto the surface, the artist appears to have dipped his brush in two or more colors and applied them directly to the canvas, where they exist almost side by side; in other areas, he applied a new color into a still-wet stroke to create this effect. The structure of the paint layers suggests that the painting was probably executed in a limited number of sessions, with each wet-in-wet layer allowed to dry before the next layer was applied. The brushwork ranges from heavily blended and smooth to thick [glossary:impasto], and the heaviest texture appears primarily in the bottom half of the composition. Various small daubs and details, including the highlights on the bottles in the foreground and the small flowers above the figures’ heads, seem to be the final steps of the process.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 2.15).

Signature

Signed: Renoir. (lower left, in warm-black paint) (fig. 2.16, fig. 2.17).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions of the canvas were approximately 54 × 64.7 cm, according to 1971 pretreatment measurements. This probably corresponds to a no. 15 portrait (figure) standard-size (65 × 54 cm) canvas, turned horizontally.

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 22.0V (0.9) × 23.9H (0.8) threads/cm. The horizontal threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the vertical threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

The canvas has very mild [glossary:cusping] around the edges, especially on the left, corresponding to the placement of the original tacks.

Stretching

Current stretching: When the painting was lined in 1971, the original dimensions were slightly increased on all sides (see Conservation History).

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed 5–6 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Four-member redwood [glossary:ICA spring stretcher]. Depth: 2.6 cm.

Original stretcher: Five-member keyable stretcher with vertical [glossary:crossbar]. Depth: Approximately 1.8 cm (fig. 2.18).

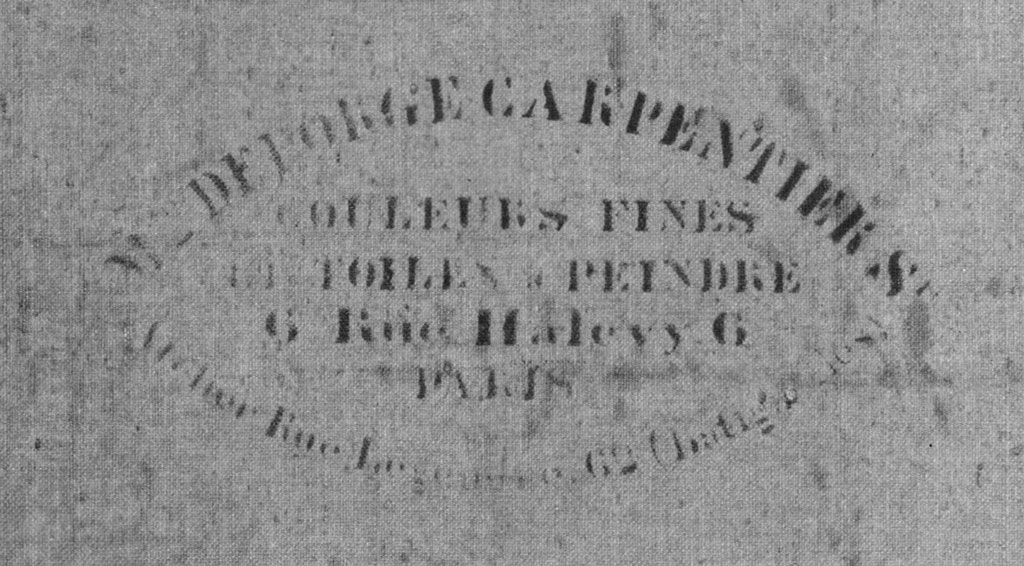

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

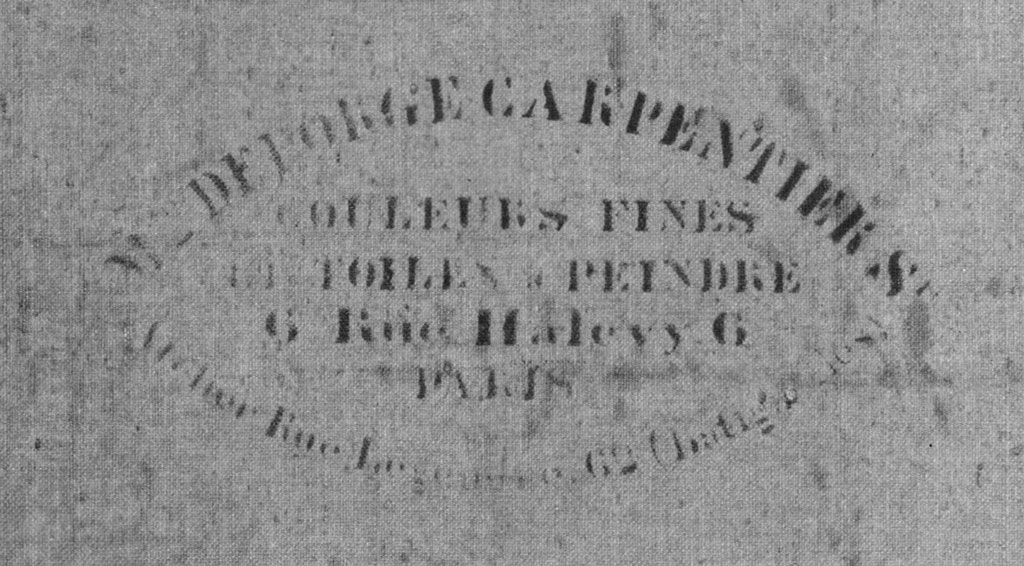

Stamp

Location: original canvas (covered by [glossary:lining])

Method: stamp

Content: M_DEFORGE CARPENTIER Sr / COULEURS FINES / ET TOILES [á] PEINDRE / 6 Rue Halevy 6 / PARIS / [. . .] Rue Legendre, 62 [. . .] (fig. 2.19; fig. 2.20)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

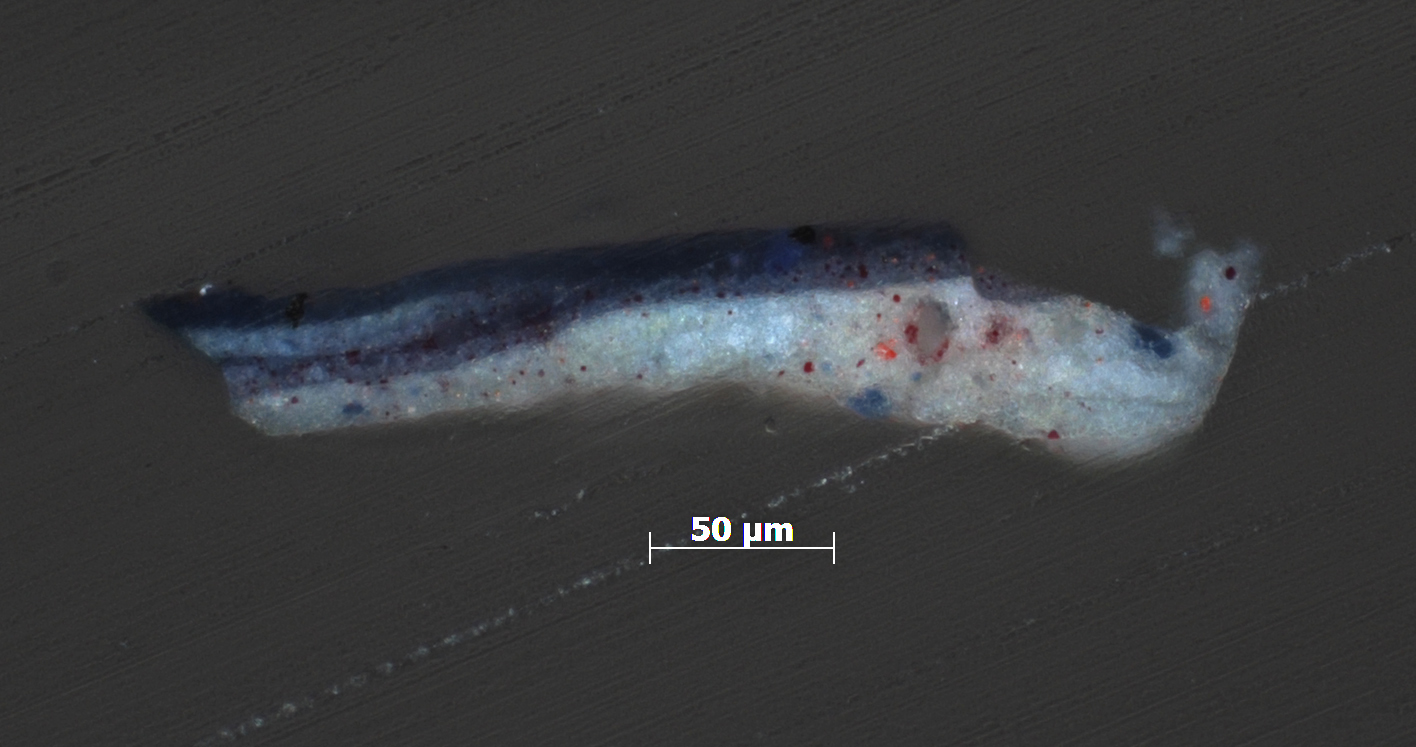

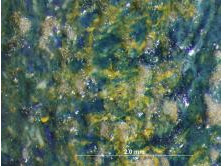

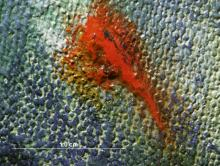

The canvas was prepared with commercially applied priming that extends to the edges of the [glossary:tacking margins]. This commercial priming appears to be a single layer, is rather thin and porous (measuring approximately 5–60 µm), and does not completely fill the [glossary:weave] (fig. 2.21).

Renoir appears to have added a selective preparatory layer to parts of the canvas, especially visible in the top half of the composition. This selective layer is thicker, smoother, and more medium-rich than the commercial [glossary:ground]; it leaves some of the canvas texture visible. The outer perimeter of this layer has a soft edge, suggesting that it was applied with a brush; however, the overall texture of this layer is very smooth with no discernible brushstrokes (fig. 2.22).

Color

The color of the commercially applied ground appears to be off-white, but it is difficult to determine. While from the surface there is no microscopic evidence of additional pigment particles in this layer, analysis indicates the presence of a small amount of an iron-containing pigment, such as iron oxide red or yellow. This commercial layer is slightly porous and has darkened due to the combined effects of accumulated grime and the saturation of the [glossary:wax-resin lining] material (see Condition Summary and Conservation History). Because of this discoloration, it is difficult to determine what effect this limited amount of colored pigment might have had on the overall tone of this layer.

The selective preparatory layer is slightly tinted to appear warm beige, and dark particles are visible in it under [glossary:stereomicroscopic examination] (fig. 2.23). In some areas, largely in the upper portions of the background, this layer was left exposed by the artist to provide a warm contrast to the cool tones of the river (fig. 2.24).

Materials/composition

The commercial ground is predominantly lead white with a significant amount of barium sulfate. There are also small amounts of iron oxide red or yellow, iron-containing aluminosilicates, silica, calcium-based whites, and trace amounts of bone black.

The selective preparatory layer is also predominantly lead white with iron oxide red or yellow and barium- and calcium-containing compounds. Stereomicroscopic examination of this layer suggests the presence of black or dark-brown particles. The [glossary:binder] for both layers is estimated to be oil.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

Infrared examination reveals very summary contour outlines that may relate to compositional elements in the left half of the painting, including the possible outline of a head (visible in the X-ray) located between the two visible figures (see Paint Layer and Technical Summary); the continuation of the vertical line that forms the left side of the trellis opening; and a faint, curved line near the bottom left corner that relates to the outer contour of the far-left visible figure’s leg (fig. 2.25).

Medium/technique

Dry media (chalk or charcoal?) (fig. 2.26).

Revisions

No compositional changes noted in drawing stage; see Paint Layer.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

It seems that Renoir began this composition with the figures, bringing up the background colors around them after they were painted and also after any major compositional changes. This is especially evident in the female figure, which was painted in relatively radio transparent [glossary:pigments] easily penetrated by the X-ray. [glossary:X-radiography] also indicates that landscape elements do not pass under the female figure’s head, and brushstrokes come up to and abruptly end around the figures, creating a kind of halo effect (fig. 2.27). The table in the center seems to be one of the earliest compositional elements, with the figures and much of the background brought in around it.

There is evidence that the artist made significant changes to this composition. Thick, directional brushwork visible in the lower left of the canvas does not match the final composition, suggesting that there are possible pentimenti in this area (fig. 2.28); these changes are clearer in [glossary:raking light] and X-radiography. The X-ray documents what appears to be a profile and head (perhaps corresponding with some of the underdrawing lines) situated between the two visible figures in the left half of the composition (fig. 2.29). The right arm of the figure in profile appears to extend to the table, along a line similar to that of the visible female figure. The thickness of the added paint layers in this area obscures the original colors of the underlying composition, making a clear identification difficult. [glossary:Cross-sectional analysis] in this area indicates that the lower part of the original figure’s costume was a light bluish-white, with areas of reddish and purple highlights, similar in tone to the clothing of the figure on the right side of the painting, but with greater impasto (fig. 2.30). The composition appears to have featured only two figures in this early stage: one on the right and one on the left (in profile). Examination of the left side of the painting in raking light calls attention to a ridge of paint that echoes the curved line of this figure’s back (though it is farther to the left). This may indicate movement of the original figure farther to the left or an adjustment to the position of the visible figure on the far left. Examination in raking light also suggests that Renoir painted out original compositional choices on the far left in thick, short, diagonal brushstrokes before he executed the almost forward-facing head of the figure in the final composition (fig. 2.31). The bulk of this original figure, however, does not appear to have been painted out, but merely covered in the process of executing the two visible figures.

Examination in raking light and X-radiography suggest that elements on the right side of the canvas may also have been altered. A horizontal, curvilinear form beginning just to the right of the figure and passing in front of his torso, with a smaller, horizontal element below it, suggests a change in the position of the chair. It is unclear how the placement of the chair would have affected the posture of the figure, and these elements appear to have been abandoned in their early stages (fig. 2.32). In natural light as well as in the X-ray, it appears that the angle of the right arm of this figure was also changed. The elbow was raised and the forearm made narrower in the final paint layers; however, the original position of the elbow is still visible on the surface. The exact placement of the figure’s left arm and hand also appear to have been slightly adjusted (fig. 2.33). Downward directional strokes through the torso as well as the thick strokes of background and [glossary:underpainting] across and around the head may hint at further changes to this figure’s posture.

In the top half of the composition, the background, the initial layers of the water, and the shoreline were painted first. The outline of the trellis opening was established next, followed by the boats and rowers, and finally the trellis and climbing foliage; each layer was allowed to dry before the subsequent elements were executed. Renoir developed the water with heavy, textured brushstrokes and added color throughout the process (generally before the trellis lattice and climbing foliage) (fig. 2.34); however, the initial layers seem relatively thin in most areas, passing under various compositional elements in the top half.

Overall, the paint was largely applied wet-in-wet over a few campaigns, and each layer was allowed to dry between sessions. Most of the colors were mixed directly on the canvas rather than on the palette (fig. 2.35). At times, the artist dipped his brush into two or three separate colors before applying a stroke to the canvas, and swirls of unmixed paint can be seen throughout the work (fig. 2.36).

The soft edges of the objects and figures—at times defined as much by the texture of the brushstroke, a physical ridge of paint, as by the color shift itself—indicate that Renoir alternated between thicker paint applied with a soft brush and more medium-rich or sometimes thinned paint applied with a stiffer brush (fig. 2.37). In some areas, soft, curled peaks of paint call attention not to the application of paint but to the lift of the brush (fig. 2.38). It is also noteworthy that he used medium-rich toning layers, sometimes called glazes. The glazes seem limited to the woman in the dark-blue dress, for which he layered translucent, oil-rich dark reds and greens over an opaque blue-and-white mixture to add tonal nuance and a sense of volume, incorporating pure blue, red lake, yellow, and perhaps black (fig. 2.39). This smoothness is countered by heavy brushwork elsewhere and by the artist’s manipulation of the canvas texture. Despite the smoother texture offered by a thick preparation, the artist accentuated the weave texture in many areas, dragging a loaded brush across the surface and catching only the thread tops (fig. 2.40).

Painting tools

Brushes, mostly soft to medium, flat and round, with strokes up to 1 cm wide.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cobalt blue, chrome yellow, viridian, emerald green, vermilion, two red lakes, and possibly chrome orange.

Stereomicroscopic examination of the surface suggests the presence of black.

The observation of a characteristic salmon-colored [glossary:fluorescence] under [glossary:UV] light indicates that Renoir used fluorescing red lake in areas of the female figure’s costume and chair, and mixed it with other colors in the signature and flesh tones (fig. 2.41). Cross-sectional analysis reveals that he used a second, nonfluorescing red lake in selected areas of the composition.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

A [glossary:natural-resin varnish] was removed and replaced with the current [glossary:synthetic varnish] in 1971. Pretreatment photographs of the verso indicate that the natural-resin varnish had penetrated cracks in the paint layer and stained the back of the canvas (fig. 2.42). This suggests that either the natural-resin varnish was applied after the painting had aged, or the work was cleaned in the past, causing partially dissolved varnish and solvent to stain the canvas (see Conservation History). There are residues of the earlier natural-resin varnish around the areas of impasto. Because the paint is medium rich and the artist-applied ground is nonporous, the current [glossary:varnish] has probably had minimal impact on the overall tonality of the painting. The thin, synthetic surface coating only slightly saturates the painting, adds more gloss, and emphasizes the overall texture of the work.

Conservation History

The painting’s condition was first documented in 1921, when it was noted that the darks were cracking. In 1971 the painting was cleaned, restretched, lined, and revarnished. The 1971 pretreatment condition notes indicate that the work was stretched on a five-member stretcher and had brittle fabric and a discolored varnish. Before the lining was applied, grime and the natural-resin varnish were removed with solvents, while additional overpaint on the right figure’s pants was removed mechanically. The lining process involved facing the work with starch paste, and then adhering a new piece of linen with wax resin. The painting was restretched on a redwood ICA spring stretcher slightly larger than the composition, leaving a small, unpainted border around the perimeter. The changes to the dimensions are as follows: in the pretreatment report, the work measured 21 5/16 × 25 1/2 in., while in the posttreatment report it was listed as 21 5/8 × 25 7/8 in. After the painting had been restretched and the facing removed, it was given three coats of synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, and a final coat of AYAA) and retouched.

Condition Summary

The work is in good condition. It is wax-resin lined and attached to a four-member spring stretcher with tacks. The wax resin has saturated the commercial priming layer and, in conjunction with accumulated grime, has altered the ground color from white to taupe, while the heat and pressure of the lining process slightly increased the textural presence of the weave. Due to the thickness of the selective preparatory layer and subsequent paint layers, the overall tonality of the painting does not appear to be affected. Some areas of thinner paint, areas of exposed commercial priming, and thinner areas of artist-applied priming were slightly pushed into the canvas by the pressure and heat of the lining process (microcracking is visible under the microscope). The original tacking margins were flattened when the painting was lined, and much abrasion is present around the original edges of the work. Some of this abrasion, as well as other mild abrasion throughout the work, is likely a result of the prelining cleaning. The restretching increased the dimensions on all sides, leaving an unpainted border almost one-quarter-inch wide around the edges of the composition. The paint layer is in very good condition, with few areas of cracking and localized minor losses. Pronounced cracking is limited to the dark-blue dress of the female figure on the left, where Renoir apparently employed medium-rich glazes. The work has a glossy synthetic varnish, and minor residues of discolored natural-resin varnish are present around areas of impasto.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

Current frame (2008): The frame is not original to the painting. It is a French (Paris), mid-nineteenth-century, Neoclassical Revival, cove frame with cabled fluting, acanthus leaves at the miters, and a stepped frieze. The frame has water and oil gilding over red bole on gesso and compo ornament. The ornament and sight molding are selectively burnished; the cove is burnished and retains its original gilding and glue sizing. The pine molding is mitered and joined with angled, dovetailed splines. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is guilloche outer molding; cove side; fillet; torus with molded, centered, imbricated laurel-and-berry ornament and acanthus leaves at the miters; fillet; cove with cabled fluting and buds and acanthus leaves at the miters; and stepped frieze in three sections: ribbon and stave followed by fillet, leaf tip followed by fillet and cove, and fillet with cove sight edge (fig. 2.43).

Previous frame (removed 2008): The painting was previously housed in an American (New York), mid-twentieth-century, French Regency, stylized frame of water-gilt, carved basswood with a décapé finish (fig. 2.44).

Previous frame (installed by 1933, removed sometime between 1960 and c. 1975): The work was previously housed in a late-nineteenth–early-twentieth-century, Louis XIV Revival, convex frame with deeply recessed cast plaster ornament of alternating flowers and pendent bellflowers, bracketed by foliate scrolls, with acanthus leaves at the miters. The frame had water and oil gilding on a dark red-brown bole over gesso and cast plaster. The sides and frieze were burnished, and the ornament was selectively burnished. The gilding was toned with raw umber and a white wash and speckled overall with black and white. The molding was mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, was ovolo with leaf-tip ornament; scotia side; convex face with alternating flower and pendent bellflower ornament, bracketed by foliate scrolls, with acanthus leaves at the miters; hollow frieze; ogee with leaf-tip ornament; cove; and fillet with cove sight edge (fig. 2.45).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris, July 8, 1881, for 600 francs.

Acquired by Alphonse Legrand, Paris, by Nov. 21, 1887.

Sold by Alphonse Legrand, Paris, to Boussod, Valadon & Cie (Theo van Gogh), Paris, Nov. 21, 1887, for 200 francs.

Sold by Boussod, Valadon & Cie (Theo van Gogh), Paris, to Guyotin, Paris, Nov. 22, 1887, for 350 francs.

Sold by Guyotin, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Mar. 21, 1892, for 1,300 francs.

Transferred from Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Mar. 22, 1892.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Potter Palmer, Chicago, Apr. 9, 1892, for $1,100.

By descent from Potter Palmer (died 1902), Chicago, to the Palmer family.

Given by the Palmer family to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1922.

Exhibition History

Paris, 11, rue Le Peletier, 2e exposition de peinture [second Impressionist exhibition], Apr. 1876, cat. 221, as Déjeûner chez Fournaise.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings from the Collection of Mrs. Potter Palmer, May 10–Nov. 1910, cat. 51, as Breakfast by the river.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, May 23–Nov. 1, 1933, cat. 350. (fig. 2.46)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Manet and Renoir, Nov. 29, 1933–Jan. 1, 1934, no cat. no. (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture for 1934, June 1–Oct. 31, 1934, cat. 239.

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Independent Painters of Nineteenth Century Paris, Mar. 15–Apr. 28, 1935, cat. 45 (ill.).

Arts Club of Chicago, Origins of Modern Art, Apr. 2–30, 1940, cat. 13.

Birmingham (Ala.) Museum of Art, Opening Exhibition, Apr. 8–June 3, 1951, no cat. no. (ill.).

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Apr. 4–May 18, 1952, no cat.

New York, Wildenstein, Olympia’s Progeny: French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings (1865–1905); Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Association for Mentally Ill Children in Manhattan, Inc., Oct. 28–Nov. 27, 1965, cat. 23 (ill.).

Milwaukee Art Center, The Inner Circle, Sept. 15–Oct. 23, 1966, cat. 81 (ill.).

Portland (Ore.) Art Museum, 75 Masterworks: An Exhibition of Paintings in Honor of the Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Portland Art Association, 1892–1967, Dec. 12, 1967–Jan. 21, 1968, cat. 13 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 28 (ill.).

Manchester, N.H., Currier Gallery of Art, Feb. 18–May 28, 1975, no cat.

Pasadena, Calif., Norton Simon Museum of Art, Jan. 27–Oct. 31, 1978, no cat.

Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, June 27–Aug. 31, 1980, cat. 21 (ill.).

London, Hayward Gallery, Renoir, Jan. 30–Apr. 21, 1985, cat. 48 (ill.); Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, May 14–Sept. 2, 1985, cat. 47 (ill.); Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Oct. 9, 1985–Jan. 5, 1986.

Art Institute of Chicago, Tour de France: Paintings, Photographs, Prints, and Drawings from the Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Dec. 9, 1989–Mar. 4, 1990, no cat. no. (ill.).

Washington, D.C., Phillips Collection, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” Sept. 21, 1996–Feb. 23, 1997, cat. 40 (ill.).

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, June 27–Sept. 14, 1997, not in cat.; Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 17, 1997–Jan. 4, 1998; Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, Feb. 8–Apr. 26, 1998 (Chicago only). (fig. 2.47)

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, Theo van Gogh (1857–1891): Art Dealer, Collector, and Brother of Vincent, June 24–Sept. 5, 1999, cat. 125 (ill.); Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Sept. 27, 1999–Jan. 9, 2000.<

Art Institute of Chicago, Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte,” June 16–Sept. 19, 2004, cat. 107 (ill.).

London, National Gallery, Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, Feb. 21–May 20, 2007, cat. 34 (ill.); Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, June 8–Sept. 9, 2007; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Oct. 4, 2007–Jan. 6, 2008.

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 23 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, A Case for Wine: From King Tut to Today, July 11–Sept. 20, 2009, no cat.

Kunstmuseum Basel, Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie; The Early Years, Apr. 1–Aug. 12, 2012, cat. 40 (ill.).

Selected References

Catalogue de la 2e exposition de peinture, exh. cat. (Alcan-Lévy, 1876), p. 21, cat. 221.

Émile Porcheron, “Promenades d’un flâneur: Les impressionnistes,” Le soleil, Apr. 4, 1876, pp. 2–3.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings from the Collection of Mrs. Potter Palmer, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1910), cat. 51.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Library Notes,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 15, 5 (Sep.–Oct. 1921), p. 161 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Handbook of Sculpture, Architecture, and Paintings, pt. 2, Paintings (Art Institute of Chicago, 1922), p. 69, cat. 844.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Accessions and Loans,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 16, 3 (May 1922), p. 47.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), pp. 67 (ill.); 150, cat. 844.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 3 (Mar. 1925), p. 33 (ill.).

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1929), p. 124, no. 102 (ill.).

Reginald Howard Wilenski, French Painting (Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1931), p. 262.

Daniel Catton Rich, “The Mrs. L. L. Coburn Collection,” in Exhibition of the Mrs. L. L. Coburn Collection: Modern Paintings and Watercolors, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1932), p. 7.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture; Lent from American Collections, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, 3rd ed., exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1933), p. 50, cat. 350.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für Freunde und Sammler der Kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), pp. 77–78. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, “The Rearrangement of the Paintings Galleries,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 27, 7 (Dec. 1933), p. 115.

Pennsylvania Museum of Art, “Manet and Renoir,” Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin 29, 158 (Dec. 1933), pp. 16 (ill.), 19.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), p. 40, cat. 239.

“Fourteen Notable Modern Paintings,” Fortune 9 (Jan. 1934), p. 33 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, A Brief Illustrated Guide to the Collections (Art Institute of Chicago, 1935), p. 28.

George Harold Edgell, Independent Painters of Nineteenth Century Paris, exh. cat. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1935), pp. 30, cat. 45; 73 (ill.).

Arts Club of Chicago, Origins of Modern Art, exh. cat. (Arts Club of Chicago, 1940), cat. 13.

Reginald Howard Wilenski, Modern French Painters (Reynal & Hitchcook, [1940]), p. 338.

Art Institute of Chicago, “The United States Now an Art Publishing Center,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 36, 2 (Feb. 1942), p. 30.

Frederick A. Sweet, “Potter Palmer and the Painting Department,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 37, 6 (Nov. 1943), p. 86.

Art Institute of Chicago, An Illustrated Guide to the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1945), p. 36.

Birmingham (Ala.) Museum of Art, Catalogue of the Opening Exhibition, exh. cat. (Birmingham Museum of Art, 1951), cover (ill.), p. 31.

Dorothy Bridaham, Renoir in the Art Institute of Chicago (Conzett & Huber, 1954), pl. 4.

Art Institute of Chicago, “The Artist Looks at People,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 52, 4 (Dec. 1, 1958), p. 100.

Raymond Cogniat, Le siècle des impressionnistes (Flammarion, 1959), cover (ill.).

Ishbel Ross, Silhouette in Diamonds: The Life of Mrs. Potter Palmer (Harper & Bros., 1960), p. 155.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), pp. 292 (ill.), 396.

Kermit S. Champa, “Olympia’s Progeny,” in Wildenstein, Olympia’s Progeny: French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings (1865–1905); Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Association for Mentally Ill Children in Manhattan, Inc., exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 1965), n.pag.

Wildenstein, Olympia’s Progeny: French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings (1865–1905); Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Association for Mentally Ill Children in Manhattan, Inc., exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 1965), cat. 23 (ill.).

J. M., “Art Israel: 26 Painters and Sculptors,” Calendar of the Art Institute of Chicago 59, 3 (May 1965), p. 8 (detail).

Milwaukee Art Center, The Inner Circle, exh. cat. (Milwaukee Art Center/Arrow, 1966), cat. 81 (ill.).

Charles C. Cunningham, Instituto de arte de Chicago, El mundo de los museos 2 (Editorial Codex, 1967), pp. 11, ill. 31; 58, fig. 1.

Portland (Ore.) Art Museum, 75 Masterworks: An Exhibition of Paintings in Honor of the Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Portland Art Association, 1892–1967, exh. cat. (Portland Art Museum/Graphic Arts Center, [1967]), cat. 13 (ill.).

André Parinaud and Charles C. Cunningham, Art Institute of Chicago, Grands Musées 2 (Hachette-Filipacchi, 1969), pp. 36, fig. 1; 69, no. 31 (ill.).

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 47, pl. 33; 159.

William Gaunt, Impressionism: A Visual History (Praeger, 1970), pp. 236–37, pl. 91.

William Gaunt, The Impressionists (Thames & Hudson, 1970), pp. 236–37, pl. 91; 242; 291.

John Maxon, The Art Institute of Chicago (Abrams, 1970), p. 86 (ill.).

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1, Figures, 1860–1890 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), pp. 232–33, cat. 305 (ill.).

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), pp. 65, pl. IL; 108–09, cat. 452 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 24; 84–85, cat. 28 (ill.).

John Rewald, “Theo van Gogh, Goupil, and the Impressionists,” Gazette des beaux-arts 81, 1248 (Jan. 1973), cover (detail); pp. 13, fig. 7; 14; 15.

John Rewald, “Theo van Gogh, Goupil, and the Impressionists—II,” Gazette des beaux-arts 81, 1249 (Feb. 1973), p. 103.

Mike Samuels and Nancy Samuels, Seeing with the Mind’s Eye: The History, Techniques, and Uses of Visualization (Random House, 1975), p. 71 (ill.).

Walter Pach, Auguste Renoir: Leben und Werk (M. DuMont Schauberg, 1976), pp. 115, fig. 51; 173.

Art Institute of Chicago, 100 Masterpieces (Art Institute of Chicago, 1978), pp. 20; 100–01, pl. 56.

Musée Toulouse-Lautrec and Art Institute of Chicago, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, exh. cat. (Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, 1980), pp. 15, no. 21 (ill.); 68.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Subscription Series,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 74, 1 (Jan.–Mar. 1980), p. 18 (ill.).

Joel Isaacson, “Impressionism and Journalistic Illustration,” Arts Magazine 56, 10 (June 1982), p. 105, fig. 37.

Hayward Gallery, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Renoir, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), pp. 166–67, cat. 47 (ill.); 168.

Hayward Gallery, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Renoir, exh. cat. (Arts Council of Great Britain, 1985), pp. 94, no. 48 (ill.); 216, no. 48 (ill.); 217.

Denys Sutton, “Renoir’s Kingdom,” Apollo 121, 278 (Apr. 1985), pp. 244; 247, fig. 8.

Charles S. Moffett, ed., with the assistance of Ruth Berson, Barbara Lee Williams, and Fronia E. Wissman, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), p. 164.

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 30–31 (detail), 32 (ill.), 119.

Françoise Cachin and Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, with the assistance of Monique Nonne, Van Gogh à Paris, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1988), p. 375 (ill.).

Robert L. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (Yale University Press, 1988), cover (ill.); pp. 246–47, pl. 250; 253.

Raffaele De Grada, Renoir (Giorgio Mondadori, 1989), p. 72, pl. 49.

Gloria Groom and J. Russell Harris, Tour de France: Paintings, Photographs, Prints, and Drawings from the Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1989), fig. 8.

Sophie Monneret, Renoir, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1989), p. 78, fig. 1.

Martha Kapos, ed., The Impressionists: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, 1991), p. 183, pl. 55.

Russell Ash and Bernard Higton, eds., The Impressionists’ River: Views of the Seine (Universe, 1992), p. 12 (ill.).

James Yood, Feasting: A Celebration of Food in Art; Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Universe, 1992), pp. 15 (detail); 50–51, pl. 16.

Anne Distel, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Luncheon (Le déjeuner),” in Richard J. Wattenmaker et al., Great French Paintings from the Barnes Foundation: Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Early Modern (Knopf/Lincoln University Press, 1993), p. 54, fig. 1.

Anne Distel, Renoir: “Il faut embellir,” Découvertes Gallimard: Peinture 177 (Gallimard/Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993), pp. 73 (detail), 169. Translated by Lory Frankel as Renoir: A Sensuous Vision (Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 73 (detail), 169.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), pp. 10, 64 (ill.).

Gerhard Gruitrooy, Renoir: A Master of Impressionism (Todtri, 1994), pp. 47 (ill.), 49, 73.

Tom Frederickson, Culinary Art: Recipes from Great Chicago Restaurants Illustrated with Works of Art from the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), p. 17 (ill.).

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 51, 103.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 2, Exhibited Works (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 44–45, 63 (ill.).

Francesca Castellani, Pierre-Auguste Renoir: La vita e l’opera (Mondadori, 1996), p. 129 (ill.).

Stephen Kern, Eyes of Love: The Gaze in English and French Paintings and Novels, 1840–1900 (Reaktion, 1996), pp. 59, ill. 25; 60.

Eliza E. Rathbone, “Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party: Tradition and the New,” in Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), p. 32.

Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), pp. 198, pl. 40; 258.

Katherine Rothkopf, “From Argenteuil to Bougival: Life and Leisure on the Seine, 1868–1882,” in Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), p. 73.

Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 186; 308, n. 8. Translated by Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, with support from Nada Kerpan for the texts by Linda Nochlin, as Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 186; 308, n. 8.

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 6; 8 (detail); 27–28; 30; 35; 47–48; 59; 72; 83, pl. 2; 109.

Charlotte Gere and Marina Vaizey, Great Woman Collectors (Philip Wilson/Abrams, 1999), p. 133.

Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art, Miyagi Museum of Art, and Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Runowāru ten/Renoir: Modern Eyes, exh. cat. (Hokkaido Shinbunsha, 1999), p. 185, fig. 5.

Chris Stolwijk and Richard Thomson, with a contribution by Sjraar van Heugten, Theo van Gogh (1857–1891): Art Dealer, Collector, and Brother of Vincent, exh. cat. (Van Gogh Museum/Waanders, 1999), p. 216, cat. 125.

Richard Thomson, “Theo van Gogh: An Honest Broker,” in Chris Stolwijk and Richard Thomson, with a contribution by Sjraar van Heugten, Theo van Gogh (1857–1891): Art Dealer, Collector, and Brother of Vincent, exh. cat. (Van Gogh Museum/Waanders, 1999), pp. 123; 125, cat. 125 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), pp. 9, 43, 45 (ill.), 50, 71, 77.

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), p. 130 (ill.).

Sylvie Patin, L’impressionisme (Bibliothèque des Arts, 2002), p. 119.

Christie’s, London, Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale, sale cat. (Christie’s, Feb. 3, 2003), p. 31 (ill.).

Robert L. Herbert et al., Seurat and the Making of “La Grande Jatte,” exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/University of California Press, 2004), pp. 112, cat. 107 (ill.); 113; 277.

Norio Shimada, Inshoha bijutsukan [The history of Impressionism] (Shogakukan, 2004), pp. 144–45 (ill.).

Eleanor Dwight, ed., The Letters of Pauline Palmer: A Great Lady of Chicago’s First Family (M. T. Train/Scala, 2005), pp. 301, 302–03 (ill.).

Kyoko Kagawa, Runowaru [Pierre-Auguste Renoir], Seiyo kaiga no kyosho [Great masters of Western art] 4 (Shogakukan, 2006), p. 70 (ill.).

Colin B. Bailey, “‘The Greatest Luminosity, Colour, and Harmony’: Renoir’s Landscapes, 1862–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), pp. 58, fig. 38; 59. Translated as Colin B. Bailey, “‘Un maximum de luminosité; de coloration, et d’harmonie”: Les paysages de Renoir, 1862–1883,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), pp. 58, fig. 38; 59.

Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, eds., Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), pp. 168; 170–71, cat. 34 (ill.); 210; 214. Translated by Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer as Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), pp. 168; 170–71, cat. 34 (ill.); 210; 214.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, with the collaboration of Camille Frémontier-Murphy, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 1, 1858–1881 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), p. 262, cat. 218 (ill.).

Robert McDonald Parker, “Topographical Chronology 1860–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), p. 275. Translated as Robert McDonald Parker, “Chronologie,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), p. 275.

Peter Bürger, “Media Differences: Caillebotte and Maupassant as Storytellers,” in Anne Birgitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen, and Gry Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Hatje Cantz, 2008), pp. 24; 25, fig. 3.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), cover (detail); pp. 20 (ill.); 64–65, cat. 23 (ill.); 73; 111. Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), front cover (detail); pp. 20 (ill.); 64–65, cat. 23 (ill.); 73; 111.

Anne Distel, Renoir (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2009), pp. 118–19, ill. 101; 190; 192.

Adrien Goetz, Comment Regarder . . . Renoir (Hazan, 2009), pp. 160–61 (ill.).

John House, The Genius of Renoir: Paintings from the Clark, with an essay by James A. Ganz, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Museo Nacional del Prado/Yale University Press, 2010), p. 59.

John House, “Catalogue 4: Luncheon (Le Déjeuner),” in Martha Lucy and John House, Renoir in the Barnes Foundation (Barnes Foundation/Yale University Press, 2012), p. 75, fig. 1.

Stefanie Manthey, “Chronology,” in Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie; The Early Years, ed. Nina Zimmer, exh. cat. (Kunstmuseum Basel/Hatje Cantz, 2012), p. 286.

Stefanie Manthey and Nina Zimmer, “Catalogue of Exhibited Works,” in Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie; The Early Years, ed. Nina Zimmer, exh. cat. (Kunstmuseum Basel/Hatje Cantz, 2012), pp. 114–15; 200–01, cat. 40 (ill.).

Christopher Lloyd, “Coastal Adventures, Riparian Pleasures: The Impressionists and Boating,” in Christopher Lloyd, Daniel Charles, and Phillip Dennis Cate, with a contribution by Giles Chardeau, Impressionists on the Water, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/Skira Rizzoli, 2013), pp. 28; 29, ill. 24.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 2064, Livre de stock Paris 1891

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 932, Livre de stock New York 1888–93

Other Documents

Label (fig. 2.48)

Documentation from the Boussod, Valadon & Cie Archives

Inventory number

Stock Boussod, Valadon & Cie Paris 18877

Stock book 12, 1887–1891

Labels and Inscriptions

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: verso of original canvas (covered by lining)

Method: stamp

Content: M_DEFORGE CARPENTIER Sr / COULEURS FINES / ET TOILES [á] PEINDRE / 6 Rue Halevy 6 / PARIS / [. . .] Rue Legendre, 62 [. . .] (fig. 2.49, fig. 2.50, fig. 2.51)

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on printed label

Content: DURAND-RUEL / PARIS, 16, Rue Laffitte / NEW YORK, 315 Fifth Avenue / Renoir No. 932 / déjeuner de canotiers / Moss (fig. 2.48)

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded), 1969 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on printed label

Content: [DURA]ND-RUEL / PA[RIS], 16, Rue Laffitte / NEW-Y[ORK], 315, Fifth avenu[e] / [. . .] No. [. . .] / [. . .] Canotiers / nsss (fig. 2.52)

Number

Location: original stretcher (discarded), 1969 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: [2]2.437 (fig. 2.53)

Number

Location: original stretcher (discarded), 1969 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 565 (fig. 2.54)

Stamp

Location: previous frame (removed), transcribed in curatorial file

Method: unknown

Content: 2987

Post-1980

Label

Location: [glossary:backing board]

Method: printed label

Content: THE NATIONAL GALLERY / Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN / Telephone 020 7839 3321 / Exhibition: Renoir Landscapes 1865–1881 / Venue(s): The National Gallery (London) 21/02/2007 to 20/05/2007 / National Gallery of Canada 08/06/2007 to 09/09/2007 / Philadelphia Museum of Art 30/09/2007 to 06/01/2008 / Number: X5651 Cat No: 34 / Artist: Pierre-Auguste RENOIR / Title: Luncheon at La Fournaise / Credit Line: The Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection, 1922.437 (fig. 2.55)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Pierre Auguste Renoir / title The Rowers Lunch / medium oil on cavas [sic] / credit Potter Palmer Collection / acc. # 1922.437 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 2.56)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with handwritten script and stamp

Content: [logo] Réunion des musées nationaux Paris / THEO VAN GOGH / Musée d’Orsay / 27 septembre 1999–10 janvier 2000 / Titre de l’œuvre: Pierre Auguste Renoir, Les Canotiers / Propriétaire: Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago / No du Catalogue: 64 (fig. 2.57)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: The Phillips Collection / America’s first museum of modern art / 1600 21st Street NW Washington, D.C. 20009-1090 / Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration / of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party” / September 21, 1996–February 9, 1997 / Artist Renoir / Title The Rowers’ Lunch / Date 1875 / Medium oil on canvas / Dimensions 21 5/8 x 25 7/8 in. (55.1 × 65.9 cm) / Lender Art Institute of Chicago / Reg # 1996.53.2 Plate # 40 (fig. 2.58)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and [glossary:transmitted-light] overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (B+W 486 UV/IR cut MRC filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/[glossary:UV fluorescence] and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: [glossary:darkfield], differential interference contrast ([glossary:DIC]), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

[glossary:Cross sections] were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state [glossary:BSE] detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 2.59).