The image of the emperor was omnipresent in Roman society. It appeared in a variety of formats and sizes, although it is known today primarily through portraits sculpted in the round, relief carvings produced for monumental public buildings, and coins. Imperial portraits served diverse purposes in a range of civic, religious, domestic, and funerary contexts, thus making them an important part of the visual landscape. The portrait head functioned as the embodiment of the emperor’s presence and was therefore expected to convey a powerful likeness that was clearly recognizable by viewers throughout the empire, not only during his lifetime but also after his death, following his apotheosis and subsequent veneration in the imperial cult.

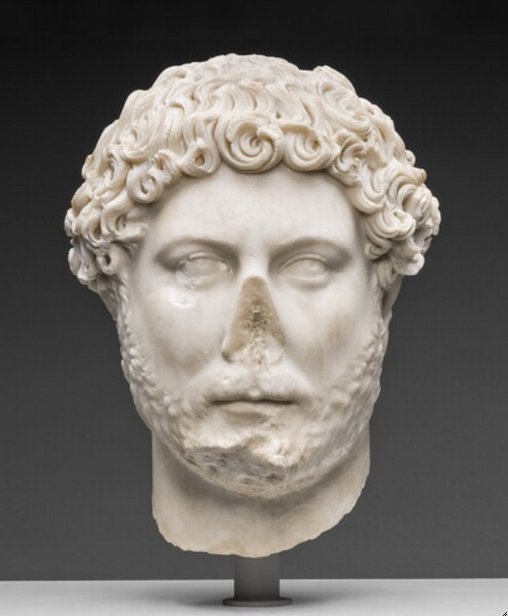

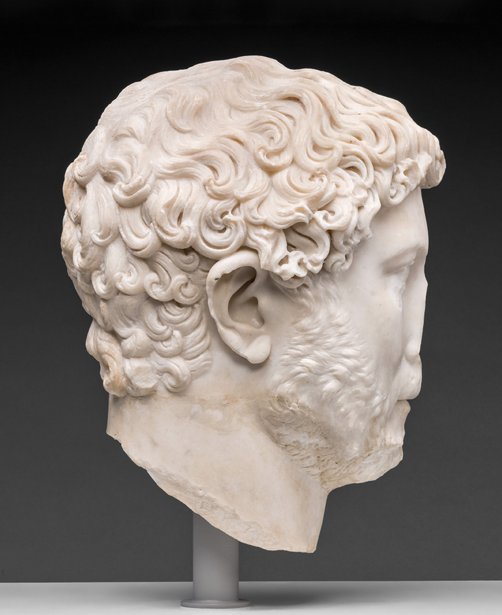

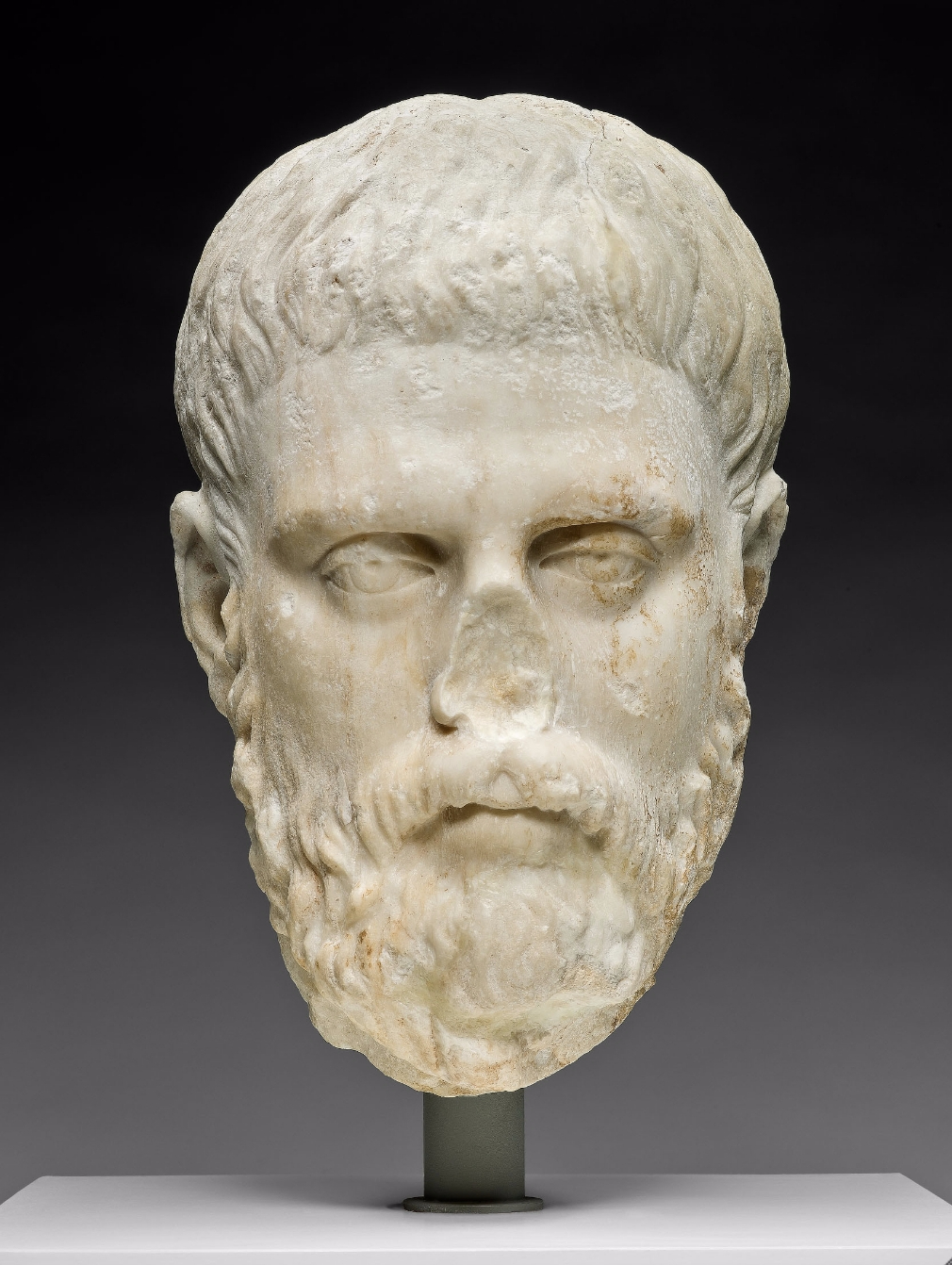

This over-life-size portrait, which is made of Carrara marble, depicts the emperor Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, more commonly known as Hadrian (A.D. 76–138; r. A.D. 117–38). Born in Rome to a senatorial family from Hispania, Hadrian was the second emperor with Spanish roots, after his predecessor Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), from whom he inherited the empire at its greatest extent. Rather than following Trajan’s expansionist policies, Hadrian worked to stabilize the strained empire by pulling back borders in some places and reforming the economic, legal, and military systems.

During the course of his nearly twenty-one-year reign, Hadrian traveled the empire widely, spending a considerable portion of his time visiting the provinces in order to oversee his reforms. His reign was also marked by an emphasis on building, not only in Rome but also in the provinces, where civic and religious structures were restored or built anew and engineering and infrastructure projects—including roads and water supplies—were undertaken. These building projects were intended not only to spread prosperity and the benefits of Roman civilization throughout the empire, but also to forge a sense of cultural unity across the numerous provinces. A noted philhellene, Hadrian was particularly fond of Greece and encouraged the architectural revitalization of Athens, which became under his rule the new spiritual center of the empire as well as the headquarters of the Panhellenion, a league of Greek city-states.

In A.D. 100, prior to his ascent to power, Hadrian married Trajan’s great-niece Sabina (A.D. 83/86–136/137), which in effect positioned him as the emperor’s successor. The marriage was childless and was characterized by later authors as unhappy. Hadrian treated Sabina with respect, however, and had her deified by the Senate following her death. The emperor is known to have favored the company of a young Bithynian man named Antinous, who drowned in the Nile River in A.D. 130.

Lacking an heir, the emperor ultimately adopted T. Aurelius Fulvius Boionius Arrius Antoninus, better known as Antoninus Pius, making him his successor. Following Hadrian’s death, Antoninus Pius (r. A.D. 138–61) obtained the Senate’s approval to grant the deceased emperor divine honors, which ensured his predecessor’s deification and continued veneration through the imperial cult, and also secured the legitimacy of his own accession.

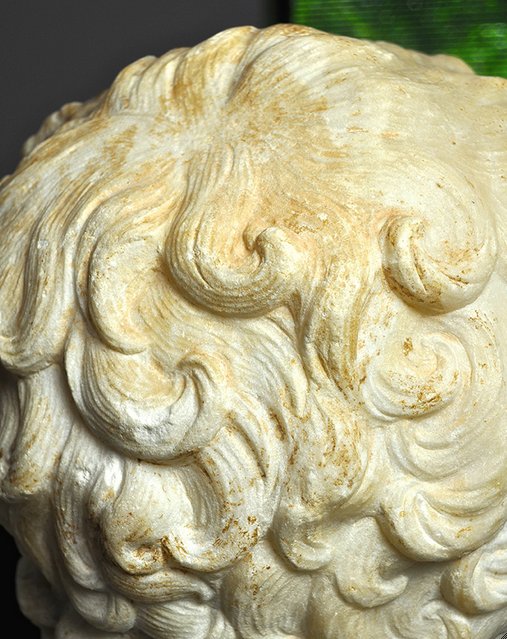

In this marble portrait, certain features have lost their crisp appearance due to a combination of minor damage and an acid cleaning, yet Hadrian is easily recognizable by his hairstyle, beard, and physiognomy. His characteristic coiffure of thick curls was made lifelike through the use of a drill in the front and on the sides to create volume and delineate individual locks. Over the forehead is an arc of rounded, upward-pointing curls that have been undercut so sharply that they stand out from the forehead below (fig. 6.1). On the back of the head, the locks are somewhat flatter, although many of the individual strands are clearly articulated, suggesting a high degree of attention on the part of the sculptor (fig. 6.2).

The distinctive cropped beard and moustache are formed by short, lightly carved tufts of hair interspersed with delicate, individual strands (fig. 6.3). Unlike the highly animated hairstyle, the beard is so subtly carved that it hardly augments the contours of the face. Both the hair and the beard reflect the sensitive hand of a highly skilled sculptor who was experienced in creating a naturalistic representation.

The rich textures of the hair and beard contrast with the smooth, unwrinkled appearance of the emperor’s broad face. Subtle signs of age are evident in the cheeks, which are somewhat more slender than those in other portraits, and in the nasolabial folds that flank the narrow lips.

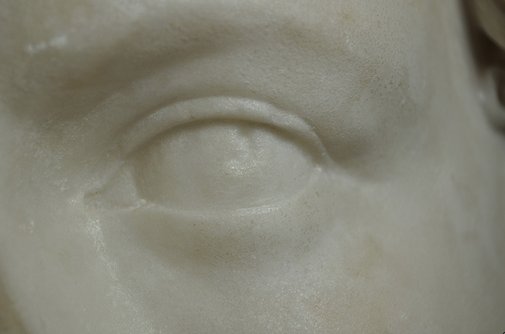

Another of Hadrian’s distinguishing traits is his narrow, almond-shaped eyes, which gaze toward his left. The eyes were enlivened through the drilling of the pupils and the incising of the irises, stylistic features that were introduced into portraiture during his reign, likely around A.D. 130. The detailed carving in the eyes and the eyebrows was largely obliterated by the acid cleaning. An additional element recurrent in images of Hadrian is the diagonal crease in each of his earlobes (fig. 6.4). Below the head are the remains of the neck, which suggests that the portrait was originally part of a full-length statue or a freestanding bust.

Imperial Portrait Typologies

The concept of the portrait type has long been the organizing principle of the study of representations of the emperor and his family. Following this methodology, extant images of an imperial personage are divided into groups that are thought to reflect a common prototype, examples of which share particular characteristics associated with the individual’s iconography, such as the arrangement of the locks of hair or specific facial features. These prototypes are generally believed to have been created in recognition of major events in the emperor’s life. They were presumably designed in Rome within the imperial circle, although it has been suggested that some were developed by competing workshops. The distribution of models may have been centrally controlled by the imperial bureaucracy, or models might have circulated from workshop to workshop through the private art trade.

In establishing the typology of an emperor’s portraits, modern scholars have traditionally focused on the hairstyle, particularly with regard to the arrangement of the front locks. Such details might have been easier for sculptors to replicate than the finer aspects of an individual’s physiognomy, which, if rendered incorrectly, might have hindered recognizability. Facial features are considered when identifying a portrait type, although sometimes to a lesser extent.

Examples of a given type are rarely identical to one another and are often understood to deviate to varying degrees from a now-missing prototype. Variations can be attributed to numerous factors, including local or regional tastes, the patron’s aesthetic goals for the work, and the sculptor’s technical prowess and familiarity with the emperor’s portrait types. It is generally accepted that portraits produced in Rome typically adhere more closely to the prototype than do those made in the provinces, where artists seem to have had greater flexibility. Certainly the ancient viewer paid less attention than the modern scholar does to the precise arrangement of the hairstyle or the rendering of the facial features on a given portrait. What mattered was that the emperor’s official likeness should be immediately identifiable.

The Vatican Busti 283 Type

Among the Roman emperors, only Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14) is represented in more surviving portraits than Hadrian, who is depicted in approximately 160 examples of sculpted portraits found to date. Hadrian’s likeness appears so frequently not only due to his long reign but also because of his extensive travels throughout the empire, during the course of which cities erected statues in honor of his visits.

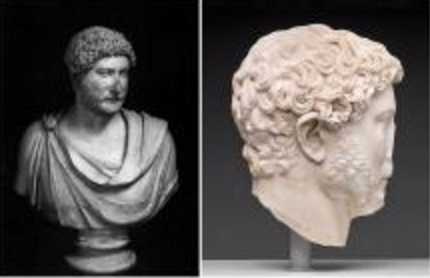

The typology of Hadrian’s portraiture was established in 1956 by Max Wegner, who identified six types representing the emperor, each of which is named after either the findspot or the location of the best-preserved example. To this list, two more types have since been added. The Art Institute’s portrait of Hadrian has been classified as an example of Wegner’s sixth type, the Typus Paludamentumbüste Vatikan Busti 283, the name piece for which is found in the Sala dei Busti of the Museo Pio Clementino in the Musei Vaticani, Rome (fig. 6.5). For the sake of brevity, this type will be referred to henceforth as the Vatican Busti 283 type.

The Chicago Hadrian is one of eight known portraits associated with the Vatican Busti 283 type. In addition to the name piece in Rome, examples in Copenhagen, Erbach (Germany), Naples, and Paris have traditionally been identified as canonical examples of the type, to the ranks of which the Chicago head has been added. The examples in Liverpool and Chania (Crete) have been less confidently assigned to the type, in part due to restorations carried out on the former and stylistic variations in the latter. While the majority of these examples are either cleaned or reworked to varying degrees, any changes that resulted from such interventions do not appear to have significantly affected the features that are used in the identification of the type.

Nearly all of these examples are believed to have originated in Italy, if not in Rome itself. While it is not known where the Chicago and Liverpool portraits were discovered, the portrait from Chania is the only one to have been found in the Greek East. Two of the examples, those in Erbach and Rome, are specifically associated with Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, suggesting that the prototype might have been created by a sculptor who was connected to the imperial court.

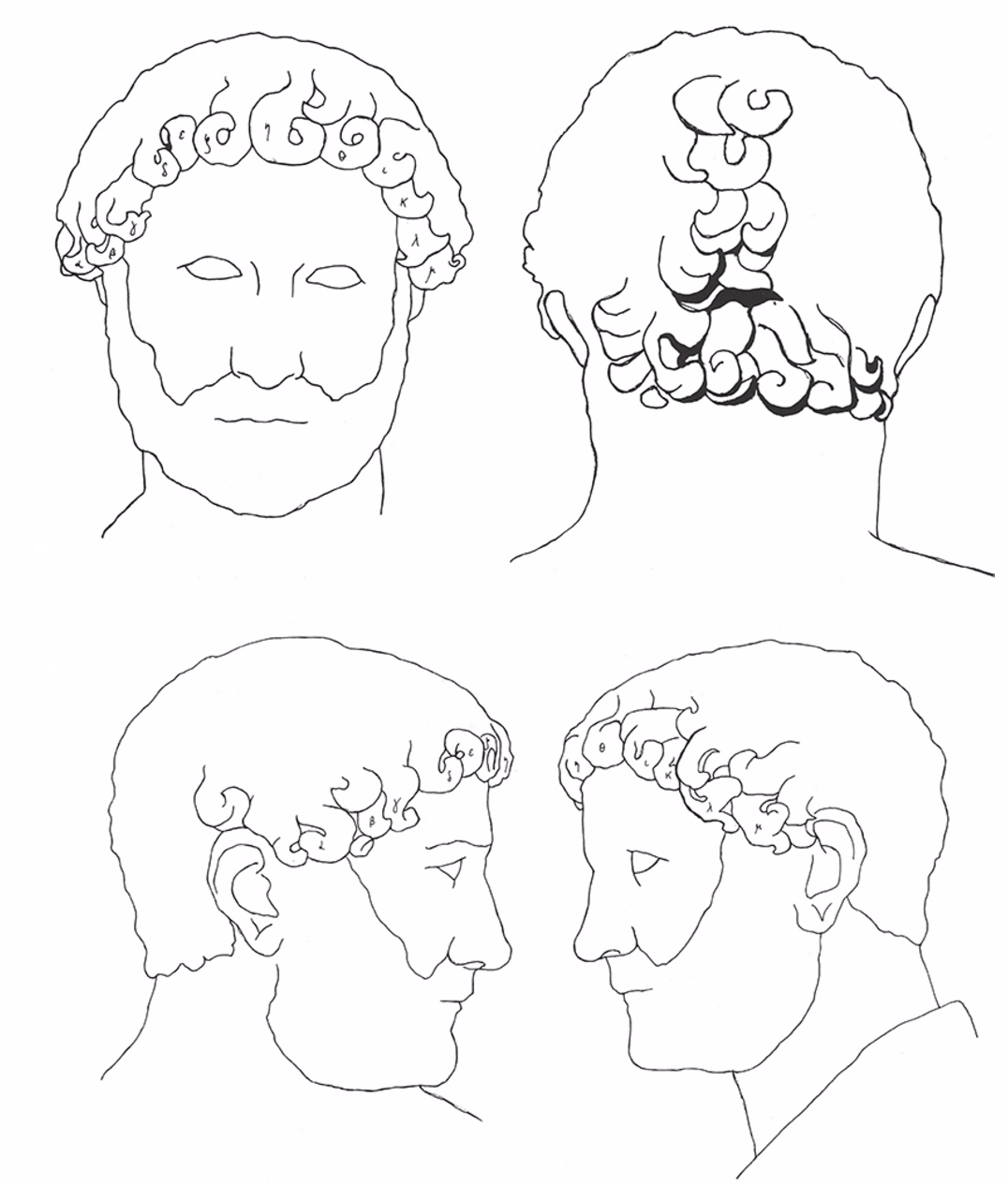

Hairstyle

Following the approach usually taken in establishing the typology of imperial portraits, the Vatican Busti 283 type was identified primarily on the basis of the distinct representation of Hadrian’s hairstyle. The coiffure of this type diverges from that of the emperor’s other portrait types in its voluminous appearance, its high degree of plasticity, and the detailed carving of the individual locks. In particular, the tight curls over the forehead are drilled at the interior, lightening what would otherwise be a dense mass of hair while also creating contrasting shadows. Based on the plasticity of the hairstyle, Wegner argued that the prototype was a work in bronze rather than in marble, although this claim is not supported by archaeological evidence.

The hair index of the Vatican Busti 283 type was mapped out by Cécile Evers, who identified approximately a dozen strands of different forms over the forehead, which are oriented in specific directions (fig. 6.6). According to Evers, the main variations among the different examples occur in the locks behind the ears and in the bottom row of curls at the back of the head. Such features may have been less visible to the ancient viewer, depending on the display context.

The hairstyle of the Chicago portrait is strikingly similar to the examples in Copenhagen, Erbach, Naples, Paris, and Rome in terms of the placement and rendering of the locks in the front and at the sides. The locks behind the ears are most similar to those of the portrait in Naples, as can be seen in a comparison of the right profile views (fig. 6.7). In both works, there are several nearly horizontal locks immediately behind the lower half of the ear, above which are small, tightly wound curls pointing toward the back of the head and a larger, drilled curl with an upward-pointing tip, which is connected to the top of the ear. Such distinct iconographic similarities could indicate that the two sculptures were made in the same workshop.

Beard

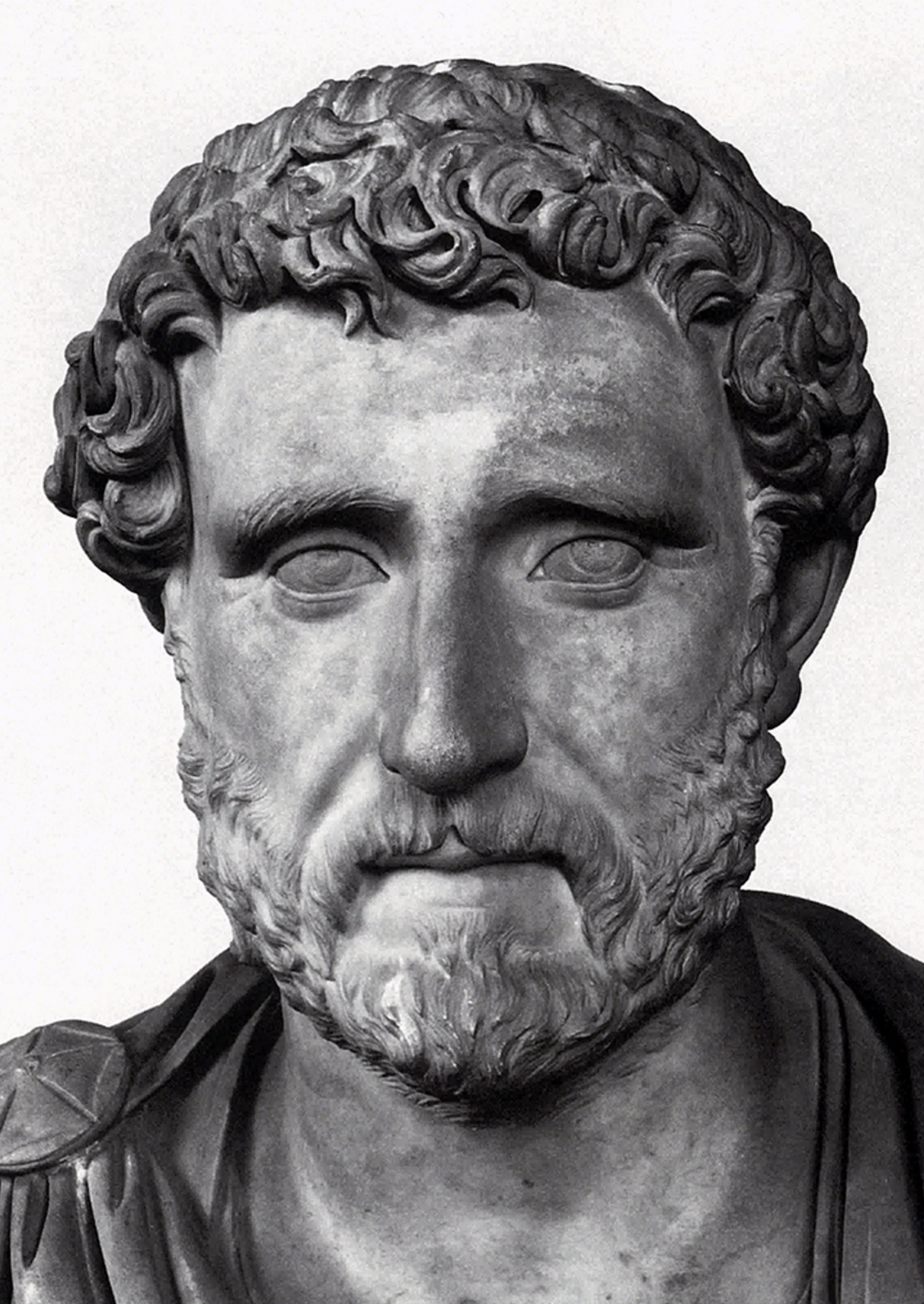

Hadrian’s beard was an equally important part of his image. It is generally accepted that Hadrian was the first emperor to consistently wear a full beard in his portraiture from the time of his accession onward, thereby distinguishing his likeness from the clean-shaven imperial visages prevalent since the reign of Augustus. The Roman tradition of shaving one’s facial hair seems to have begun as early as 300 B.C., thus making the beardless face a clear sign of Roman male identity. Yet, despite this apparent break with tradition, Hadrian’s choice established a new standard for imperial representation: the wearing of the beard was taken up by the majority of his successors until the emperor Constantine (r. A.D. 306–37), who returned to an unbearded appearance (see fig. 6.8). This fashion was also embraced by private individuals, whose likenesses similarly incorporated beards for roughly the next two centuries.

Beards had long been worn by specific groups and in specific circumstances. They were commonly worn by men on military campaign, as attested on Roman monumental reliefs, such as those on the Column of Trajan in Rome and on the Arch of Trajan at Beneventum, Italy. The look was also favored both by members of the lower classes and by younger, fashionable men. More generally, young men are thought to have worn the beard until they officially reached adulthood, when it was ritually shaven off as a sign of maturity and dedicated to the gods. It might also be worn as a sign of mourning.

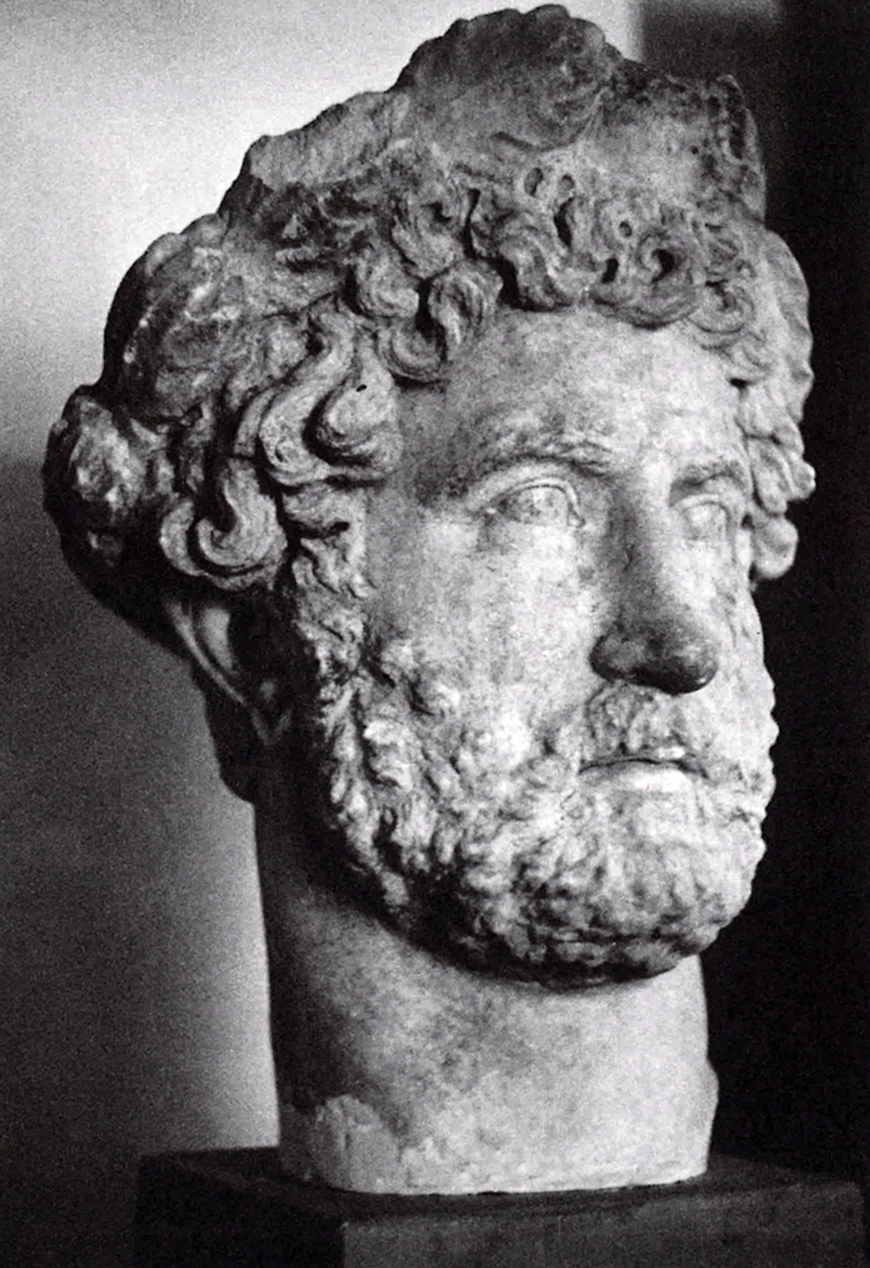

Why Hadrian wore a beard is not known for certain, but a number of theories have been proposed. On a practical level, it may have served to cover blemishes or scars. More frequently, it has been argued that the beard was an overt sign of his philhellenism. Nicknamed “Graeculus” (“the Greekling”), Hadrian had a passion for Greek culture, literature, and philosophy that has often been thought by modern scholars to explain his motivation for continuing to wear facial hair after becoming emperor. Indeed, the beard had long been viewed in the Roman world as “the mark of the Hellene.” Greek intellectuals and philosophers were often depicted with long facial hair, groomed to varying degrees (see fig. 6.9). It has been suggested that Hadrian’s beard might have been inspired in part by the words of the Greek philosopher Epictetus, who advised that facial hair was intended by nature to help distinguish men from women. However, Hadrian’s cropped beard did not resemble the long beard associated with Greek intellectuals. Contemporary Greek adult males of Hadrian’s time also often wore beards—neatly trimmed—and another possibility is that Hadrian’s beard reflected this “cultivated” Greek fashion. Hadrian’s beard is indeed typically characterized by a neat and trim appearance, and in the examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type it is especially light and closely cropped.

In recent years, the “Greekness” of Hadrian’s beard has been challenged. As noted above, in the Roman context beards could also carry military connotations. It has thus been proposed that the beard might have been part of a conscious political strategy concerning Rome’s relationship with the contemporary Greek world. Given the increasing importance of the Greek-speaking provinces, it was critical to demonstrate Rome’s ability to protect them and to maintain control over the empire, particularly in light of the Jewish revolt that had occurred in Cyrene in A.D. 115 and spread the following year to Alexandria and Cyprus, which resulted in thousands of deaths and considerable destruction of property. Consequently, the beard might be more appropriately read as the “mark of a military man of the younger generation,” especially on a portrait combined with a cuirassed body. Further, it has been suggested that Hadrian’s beard and overall appearance were intended to distinguish his likeness from that of Trajan, perhaps in order to reflect his renunciation of his predecessor’s expansionist policies.

As this scholarly debate implies, it is likely that the beard had no single message. Rather, its reception would have depended on the cultural perspective of any given viewer and the context in which a portrait was displayed; the beard might simultaneously convey both Hellenic cultural associations and Roman political concepts. A multivalent and novel feature for a standard imperial image, Hadrian’s beard is a defining characteristic of the emperor’s portrait typology.

Facial Features

To a lesser extent, physiognomic similarities among the portraits of Hadrian have also supported the idea that they are all based on a common sculptural model. In particular, scholars have noted the leftward orientation of the eyes, indicated by the incising of the irises and the drilling of the pupils, the latter of which are rendered as diagonally oriented crescents. The leaner face, with its more visible bone structure and subtle nasolabial folds, is also cited as a characteristic of this type. A comparison of the Chicago portrait with the example in Copenhagen clearly demonstrates the repetition of these features (fig. 6.10).

Dating

Following Wegner’s suggestion, it is generally believed that this portrait type was developed late in Hadrian’s reign. More specifically, it might have been created sometime after his return to Rome in A.D. 132, or perhaps even in A.D. 137 in celebration of his vicennalia, which occurred the year before his death. This interpretation is based in large part on a stylistic reading of the technique used to render the hairstyle. The deep carving and drilling, which creates an interplay between light and dark in the individual locks, seems to foreshadow the richly carved men’s coiffures of the Antonine period, as seen in the portraiture of Hadrian’s successor, the emperor Antoninus Pius (see fig. 6.11).

Hadrian’s facial features in examples of this type are thought to be suggestive of his advanced age. Some scholars have read the more slender face and pronounced cheekbones as signs of a loss of physical vitality, and the eyes, which gaze distantly to the left, as evoking a disheartened and melancholic attitude. A late date might also be reinforced by the drilling of the eyes in a number of the examples, given that innovation around A.D. 130. Yet elsewhere the type has been described as representing a “calm, powerful, intelligent Hadrian.” As the interpretation of Hadrian’s physiognomy is highly subjective, attempts to assign a date to the sculptural prototype on these grounds ought to be met with some skepticism. However, the small number of portraits of this type may support a late date; if the prototype was produced shortly before Hadrian’s death, its copies might not have been widely distributed.

With regard to the date of the Chicago portrait, it is apparent that it was created around A.D. 130 or after based on the articulation of the pupils and irises. Although the extant examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type have generally been dated to the Hadrianic period, if not to the latter part of Hadrian’s reign, it is not possible to rule out a slightly later date for the Chicago portrait, possibly in the years immediately following his death, in large part due to the Antonine stylistic features of his hair. Indeed, dates in the early Antonine period have been suggested for both the Liverpool and Rome portraits based on the comparable plasticity of the curls and the extensive drill work within the hairstyle, while a possible Antonine date has also been proposed for the Chania portrait due to its general similarities to the portraiture of Antoninus Pius. However, in the absence of further stylistic or contextual evidence suggesting the Chicago portrait’s posthumous creation, a date in the late Hadrianic period (A.D. 130/38) seems the most probable.

Portrait Formats: Freestanding Statues and Busts

Among the eight examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type, at least five can be clearly associated with either a full-figure statuary body or a freestanding bust. It is likely that the Chicago portrait was incorporated into one of these two formats.

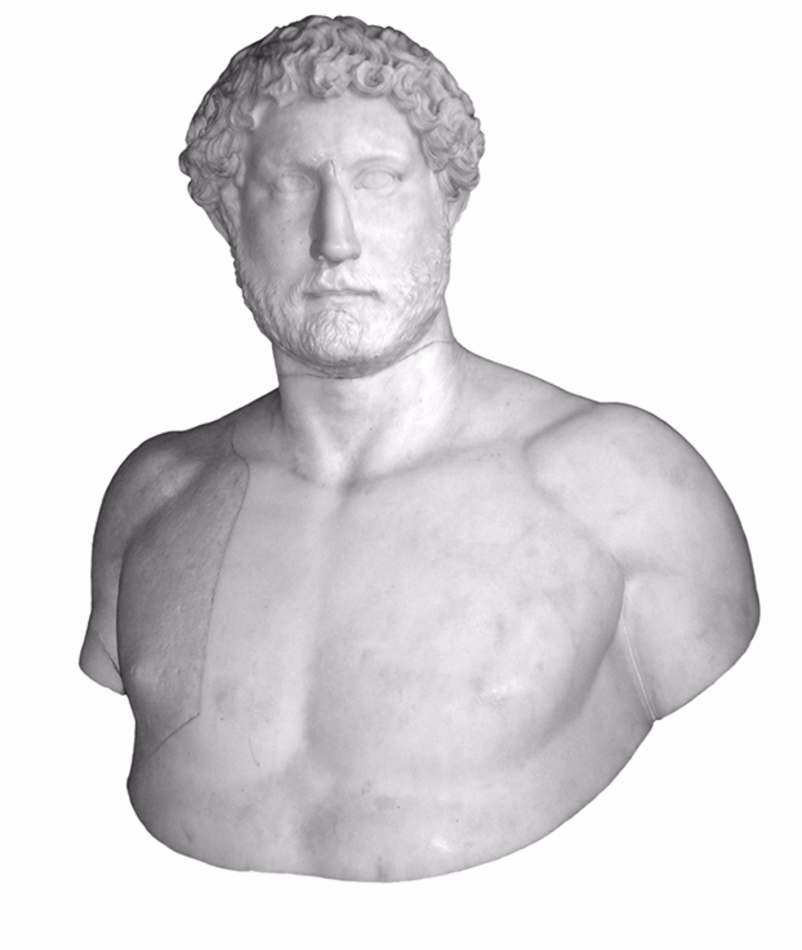

Statues

Portraits presented with full-length statuary bodies were frequently employed in the public sphere, where they typically served an honorific function. There were several basic body types available for use in imperial and private male portrait statues: wearing a toga, wearing a cuirass, or in the nude. These body types functioned as costumes that conveyed basic messages about the individual’s public roles, social status, virtues, and values. The toga identified the man as a Roman citizen or public officeholder. The cuirassed body type, complete with weapons and paludamentum, identified the subject as a military commander, an individual of military distinction (actual or honorary), or, in the case of the emperor, commander in chief. The nude body, which was considered an entirely artificial costume, informed the viewer of the individual’s virtuous character, masculinity, and strength. Less frequently, a statuary body might be clad in a pallium (the Roman version of the Greek himation) in order to identify a man as an intellectual, such as a philosopher or poet. Beyond these basic messages, the precise meaning of the likeness depended not only on the display context but also on the addition of attributes and gestures, through which the portrait of an emperor might be further distinguished from those of other individuals.

Fifteen full-length statues of Hadrian of all portrait types are documented in current scholarship. In these portraits, Hadrian is shown with all three of the standard body types: togate, cuirassed, and heroically nude. The only example of the Vatican Busti 283 type known to have been incorporated into a full-length body is the example from Chania, which was found in the Diktynnaion sanctuary at Menies, Crete (fig. 6.12). This head and its cuirassed statuary body were largely destroyed by fire over a decade after the portrait’s discovery in 1913.

Hadrian seems to have favored the cuirassed body type in his portraiture, possibly because he felt the need to project a strong military image to reinforce the impression of Rome’s strength and the security of its borders. Given the emperor’s role as the protector of the empire, his portraits may have been especially meaningful in the provinces of the Greek East, which bordered many of the conflict zones resulting from Trajan’s expansionist policies. The Chania portrait, with its cuirassed body and bearded head, might have conveyed to the viewer in Crete general messages of Hadrian’s military and political protection and potentially also a sense of his Greek cultural interests.

Busts

At least four examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type are freestanding busts. The freestanding bust, which was used for portraits of the imperial family and private individuals alike, has been described as the “quintessential Roman portrait format.” Unlike full-length portrait statues, which were primarily employed in the public sphere, the portrait bust could be displayed in a range of contexts, including public, domestic, and funerary settings. The same basic costumes that were used in statuary bodies of men also appear in busts, although there were some chronological and iconographic differences in their application in the two formats.

The abbreviated format of the bust, which reached its maximum size during the reign of Hadrian in the portrait busts of Antinous, encouraged a different kind of engagement with the artwork than was achieved with a statue. On one level, the bust might have made a portrait more portable, allowing it to be moved around within a space to best suit the decorative and ideological message of a given moment. The bust might also have encouraged a closer, more intimate experience of the portrait on the part of the viewer, who might focus on the head as an expression of the subject’s identity and personal qualities.

All four examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type that preserve traces of the bust are shown in some form of heroic nudity. The example in Rome , which preserves part of the proper right arm, shoulder, and chest but which is otherwise largely restored, might have been completely nude. It is possible, however, that there might have been a cloak over the missing proper left shoulder, a motif that appears in a portrait of Trajan of the so-called Dezennalientypus in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (fig. 6.13), the first clearly identified imperial type to be designed with the bust as an integral part of the portrait.

The busts in Copenhagen, Naples, and Paris all incorporate a cloak that is draped over both shoulders and pinned on the proper right shoulder with a fibula. The cloak has commonly been identified as a paludamentum, which was worn by commanders in full military costume. Such an interpretation might suggest that these portraits were intended to evoke the emperor’s military superiority. All three are lacking a cuirass, however, instead representing the subject partially nude. This was a motif used in depictions of Greek heroes, who were typically shown wearing a chlamys. This combination of idealized nudity and the cloak might therefore refer to more general heroic ideals of strength, courage, and virtus, rather than to military prowess specifically. A heroic reading of the emperor is more likely intended here.

Four of the five examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type that bear the closest similarities to the Chicago portrait in terms of hairstyle and physiognomy—those in Copenhagen, Naples, Paris, and Rome—are associated with nude or partially nude portrait busts. Consequently, it seems reasonable to surmise that the Chicago portrait might also have been part of a bust employing some form of the heroically nude costume.

Display Contexts

If the Chicago portrait was formerly part of a portrait bust, its abbreviated format would probably have encouraged its display in a setting that permitted the viewer’s close observation of and engagement with Hadrian’s likeness, such as an imperial villa. Imperial villas served simultaneously as residences and administrative centers. They were large complexes where the emperor conducted business, albeit perhaps in a more informal manner than would pertain elsewhere. Consequently, the viewing audience in this setting included not only family members but also friends and political elites.

Portrait busts of sitting emperors, their predecessors, and other members of the imperial family have been found in a number of imperial villas in addition to Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, including the villa of Antoninus Pius at Lanuvium, the villa of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Acquatraversa, and the villa of Maxentius on the Via Appia. Although the functions of such portraits in these settings are not entirely clear, it is possible that they were displayed in ancestral portrait galleries or created as gifts to be exchanged between the emperor and private individuals. Given the association of the Rome and Erbach portraits with Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, the Vatican Busti 283 type may well have been considered appropriate for display in a lavish villa that functioned as both an imperial residence and an administrative seat.

The Chicago portrait (if a bust) might also have been displayed in an elite private residence either outside of Rome or elsewhere in the empire. The domestic display of an imperial portrait might have reflected the owner’s strong loyalty toward the emperor while also conferring an air of prestige. Or it might have been employed in a household’s private veneration of the emperor; in this case, the bust’s approachable format would no doubt have enhanced the viewer’s engagement with the emperor’s image.

Alternatively, the portrait might instead have served an honorific purpose in a civic setting. Although there is little evidence for how busts were displayed on public monuments, the prevalence of the niche in different forms of imperial architecture, including civic structures such as theaters, baths (thermae), and monumental fountains (nymphaea), as well as in the back walls of colonnaded streets and squares, suggests that such works may well have been displayed in these settings alongside full-length statues.

A portrait bust might also have been displayed in a sanctuary or temple, whether one dedicated to a specific deity or to the imperial cult, where it could function as an honorific portraitor a cult image. Numismatic evidence sheds some light on the display of portrait busts and statues in religious settings. For example, in a bronze coin of Caracalla from Side (in modern-day Turkey), the reverse depicts a draped, cuirassed bust of the emperor on a pedestal or an altar, beside which stands the Greek god Ares (equivalent to the Roman Mars) holding a spear in his right hand (fig. 6.14). Although such coin representations cannot typically inform us of the size of the original images, they nevertheless illustrate the presence of imperial busts and statues in religious contexts. Additionally, imperial busts might also have been carried in religious processions at imperial festivals and on other occasions due to their portable nature, indicating their dynamic function at such events.

Conclusion

The success of the emperor’s image depended on the extent to which it was easily recognizable. Hadrian’s thick, curly hair and cropped beard undoubtedly played a critical role in his identification, as they helped to distinguish him from his predecessors with their forward-combed locks and clean-shaven visages. His broad, smooth face, almond-shaped eyes, and narrow lips were also defining features of his physiognomy.

Among the eight portrait types that depict Hadrian, the Vatican Busti 283 type is distinct for its voluminous, richly carved hairstyle, its equally skillful rendering of a closely cropped beard, and its relatively slender proportions. The Chicago portrait bears the hallmarks of the Vatican Busti 283 type, not only in its use of lavish, coloristic effects in the hair, which prefigure the styles employed in Antonine portraits, but also in the beard, which is so delicately carved that it barely augments the contours of the face. Although the face is unlined, the slightly more pronounced cheekbones and the subtle nasolabial folds hint at the emperor’s advancing age. Based on these features, as well as the fact that the eyes are enlivened with incised irises and drilled pupils—an innovation of around A.D. 130—it is likely that the portrait was created late in Hadrian’s reign.

While the portrait head functioned as the primary embodiment of the emperor’s identity, it was through its combination with a bust or full-length statuary body that the imperial image could convey a larger ideological message to the viewer that was specific to the context in which it was displayed. Among examples of the Vatican Busti 283 type, at least four portrait heads are attached to busts showing the emperor in some form of heroic nudity, conveying his masculinity and virtus. The Chicago portrait was therefore most probably part of a bust in antiquity, which may have been displayed in an imperial or private villa, or perhaps either in a public building or in the religious context of a sanctuary or temple.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This portrait head is a fragment of a bust or statue depicting Emperor Hadrian (fig. 6.15). It was carved from a single block of exceptionally fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Carrara. The carving itself is the work of a master sculptor whose artistry and adroit handling can be seen in the skillful use of drilling techniques and in the presence of decorative struts and bridges. An age-related patina and burial incrustations throughout the hair offer valuable evidence of antiquity. No indication of polychromy or gilding has been detected. During its time in the museum’s collection, the object has received one documented treatment, but, prior to its acquisition, the portrait underwent other campaigns of restoration, including the application of stone replacements at the nose and chin, as well as an acid cleaning.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The stone is a cool, bright white with a somewhat gray-green tone overall.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); opaque minerals (traces)

Petrographic Description

A triangular sample 1.8 cm high by 1 cm wide was removed from a small projection of stone at the bottom edge of the neck on the proper right side, approximately 5 cm in from the back. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.56 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic, polygonal with triple points

Calcite boundaries: straight-curved

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed slight decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 6.16

Provenance

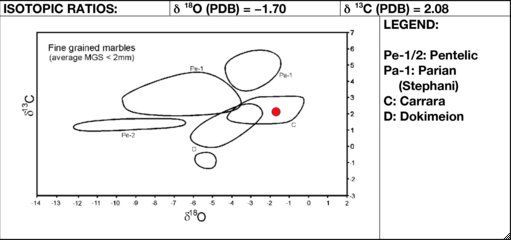

Marble type: Carrara (marmor lunense)

Quarry site: Carrara region, Apuan Alps, Italy

The determination of the marble as Carrara was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 6.17

Fabrication

Method

The object was carved in the round from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

The head is a fragment of a slightly over life-size bust or statue. The bottom of the neck is angled forward and is somewhat flat, reminiscent of a straight butt join. The surfaces of straight butt joins are often keyed to provide extra tooth for a mortar or adhesive. The surface of this break edge, however, is highly irregular and shows signs of intentional damage. Long drill holes extend from the outer margins of the neck toward the center (fig. 6.18), and deep gouges made with a flat chisel are also visible (fig. 6.19). Neither of these marks is characteristic of the keying seen on ancient join faces. In addition, the chisel marks extend into areas of adhesive residue. The adhesive is decidedly modern in appearance, and its copious application indicates that it was intended to fill gaps as well as bond. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the head was attached to something else in a modern restoration campaign and subsequently removed.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The portrait was finished to a high degree, and early stages of carving were fully removed from all areas that would have been visible in antiquity. The extent of the surface finish, compounded by the effects of a subsequent, overzealous cleaning, has left few discernible toolmarks on the surface.

The faint traces that do remain are a testament to the consummate skill of the sculptor. In order to render the depth and volume of Hadrian’s hair, the artist made extensive use of a drill and a channeling tool. Each curl was created by piercing the stone at intervals with a very narrow drill, approximately 2 mm in diameter. This network of holes was then excavated with a channeling tool or small roundel. In a few isolated areas, remnants of the drill holes can just barely be seen within the deepest of the carved lines (see fig. 6.20). In one instance it is clear that the sculptor applied a bit too much pressure, drilling too far into the stone and leaving behind a hole that could not be fully cleared (fig. 6.21).

A drill was used to delineate the contours of the ears, as evidenced by the circular depressions seen at the ends of the lines of carving (see fig. 6.22). Half of a drill hole is also visible in what remains of the proper right nostril.

At the back of the head, where the impression of depth and volume was less important, the sculptor rendered the curls using a small roundel, painstakingly delineating individual strands of hair. This workmanship is well preserved on the crown of the head, where it may have been protected by an overlying incrustation that has since been removed (fig. 6.23). Although the detail in the curls on the front of the head has been considerably diminished by exposure and aggressive cleaning, it is safe to assume that the front of the hair was originally carved to a similar degree of detail as the back.

The rendering of the beard, although much affected by the cleaning, is equally sensitive. The larger tufts of hair were also created with the roundel but were highlighted, and individual hairs emphasized, by the selective use of a flat chisel turned on its edge (fig. 6.24).

Within the carving of the hair, the sculptor left small bridges connecting several curls (see fig. 6.25 and fig. 6.26). Generally speaking, struts and bridges are employed where added strength or support is needed. Given the sizes and locations of these small projections, it seems very unlikely that such minuscule quantities of stone serve any structural function. Their purpose was more likely decorative, and they are a further display of virtuosity on the part of the artist.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The fragment is itself fragmentary. A break extends from the nape of the neck to the jawline and continues downward to the base of the throat. Along this trajectory, smaller fragments can be seen in association with the primary break. This damage is visible to the naked eye, but its extent becomes all the more apparent under ultraviolet radiation (fig. 6.27). These areas of damage were at some point cursorily restored by bonding and filling with a resin, now yellowed. In several places the resin was bulked with aggregates, most likely marble powder or dust, in an effort to mimic the stone, and in other places the surface of the repairs was retouched with what could be, judging by the way it has aged, an oil-based paint. Within the beard, particularly on the proper right side, the fills were crudely scratched or carved in an attempt to mimic the whorls in the hair, causing a great deal of associated damage to the surrounding stone.

The portrait is bereft of its nose and a large portion of the chin on the proper right side. These areas once bore stone replacements, as indicated by the presence of dowel holes. The vestiges of the nose were cut flat and smoothed prior to receiving the stone restoration. At a later point, the nose was removed, the centrally located dowel hole in the nose was filled with a resin, and the break edge was retouched in an effort to mimic age-related staining and soiling. For the restoration of the chin, the contour of the break was left rough, and three holes in a triangular configuration were drilled to accommodate the dowels. This restoration was also removed at some point. The dowel hole closest to the center of the chin was filled with resin, but the two holes on the proper right side remain plugged with the marble dowels (fig. 6.28).

Numerous losses are visible on the tips and high-relief areas of the curls framing the face and ears. The outside edges of both ears are missing. Chips and losses are visible all around the break edge of the neck, with two particularly conspicuous lacunae on the front of the neck. The underlying stone exposed in these lacunae displays a sugary texture.

Further damages and blemishes exist. A deep puncture with heavy associated bruising is visible just above the proper right tear duct (fig. 6.29). Aspects of this anomaly appear deliberate; it may have been a failed, initial attempt at recutting in an effort to resharpen the contours of the eyes. Large spalls can be seen below the proper right eye and on the lower lip on the proper left side. Elsewhere numerous small spots of blanching, bruises, pockmarks, and scratches are evident. An area of particularly heavy scratching is present within the beard near the proper left jawline.

Localized orange staining and reddish-brown incrustations, probably indicating an iron-rich burial environment, are visible on the back of the head, concentrated in a circular patch at the crown (fig. 6.23). Given the degree of preservation of the carving in this area, it seems likely that this circular patch was at one time a concretion that protected the underlying stone. A distinct yellowish-brown patina is visible throughout the hair, particularly atop the points of highest relief on the curls at the front of the head.

The surface of the stone bears the telltale soapy appearance of an acid cleaning. This waxy sheen is particularly noticeable within the beard along the sides of the face and inside the ears. The caustic action of this treatment obliterated much of the fine detail of the carving, in particular the incised details in the eyes (fig. 6.30). This aggressive cleaning notwithstanding, the surface of the stone imparts an overall impression of soiling and wear.

Conservation History

The object has received one documented treatment during its time in the museum’s collection, carried out shortly after acquisition. The goal of the treatment was to ameliorate the considerable dirt and soiling noted in the incoming statement of condition. The surface of the marble was first warmed and rinsed multiple times with an aqueous solution. To remove more-ingrained dirt, the surface was cleaned with a saponified and buffered solution of distilled water. Successive applications of a buffered aqueous gel were used to mitigate heavy incrustation and soiling around the crown of the head. A final poultice of distilled water was applied to the treated area to ensure complete removal of the gel from the stone.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini

Selected References

Art Institute of Chicago, “Acquisitions,” Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 1978–79 (Art Institute of Chicago, 1979), p. 35.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Report of the President,” Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 1978–79 (Art Institute of Chicago, 1979), p. 12 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Recent Accessions in the Department of Classical Art,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 74, 1 (Jan.–Mar. 1980), p. 8 (ill.).

Cornelius C. Vermuele III, Greek and Roman Sculpture in America: Masterpieces in Public Collections in the United States and Canada (University of California Press, 1981), p. 309, fig. 265.

Art Institute of Chicago, Pocketguide to the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1983), p. 17, fig. 13.

Max Wegner, “Verzeichnis der Bildnisse von Hadrian und Sabina.” Boreas: Münstersche Beiträge zur Archäologie 7 (1984), p. 113.

Klaus Fittschen and Paul Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts in den Capitolinischen Museen und den anderen Kommunalen Sammlungen der Stadt Rom, Band I: Kaiser- und Prinzenbildnisse (Zabern, 1985), p. 58, n. 1.

Art Institute of Chicago, Pocketguide to the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1988), p. 9, fig. 13.

Karen Alexander and Mary Greuel, Private Taste in Ancient Rome: Selections from Chicago Collections, exh. brochure (Art Institute of Chicago, 1990), cat. 10.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago: The Essential Guide, selected by James N. Wood and Teri J. Edelstein, entries written and compiled by Sally Ruth May (Art Institute of Chicago, 1993), pp. 94–95 (ill.).

Cécile Evers, Les portraits d’Hadrien: Typologie et ateliers (Académie Royale de Belgique, 1994), pp. 102, cat. 29; 259; 261; 263–64; 315, fig. 46; 316, fig. 48, 317.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Roman Art,” in “Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 1 (1994), p. 70, cat. 47 (ill.).

Karen Alexander, “The New Galleries of Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” Minerva 5, 3 (May–June 1994), p. 34, fig. 12.

Art Institute of Chicago, Pocketguide, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago, 1997), p. 9, fig. 13.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures from the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood, commentaries by Debra N. Mancoff (Art Institute of Chicago, 2000), p. 72 (ill.).

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Roman Imperial Persons in North America,” Celator 17, 12 (Dec. 2003), p. 30.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Faces of Empire (Julius Caesar to Justinian),” Celator 19, 12 (Dec. 2005), p. 22, fig. 2.

Jeff Ruby, “The Closer: Second Looks,” Chicago (June 2006), p. 228 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago: Pocketguide (Art Institute of Chicago, 2009), p. 23, fig. 44.

Karen B. Alexander, “From Plaster to Stone: Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Karen Manchester (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), pp. 32; 39, n. 134.