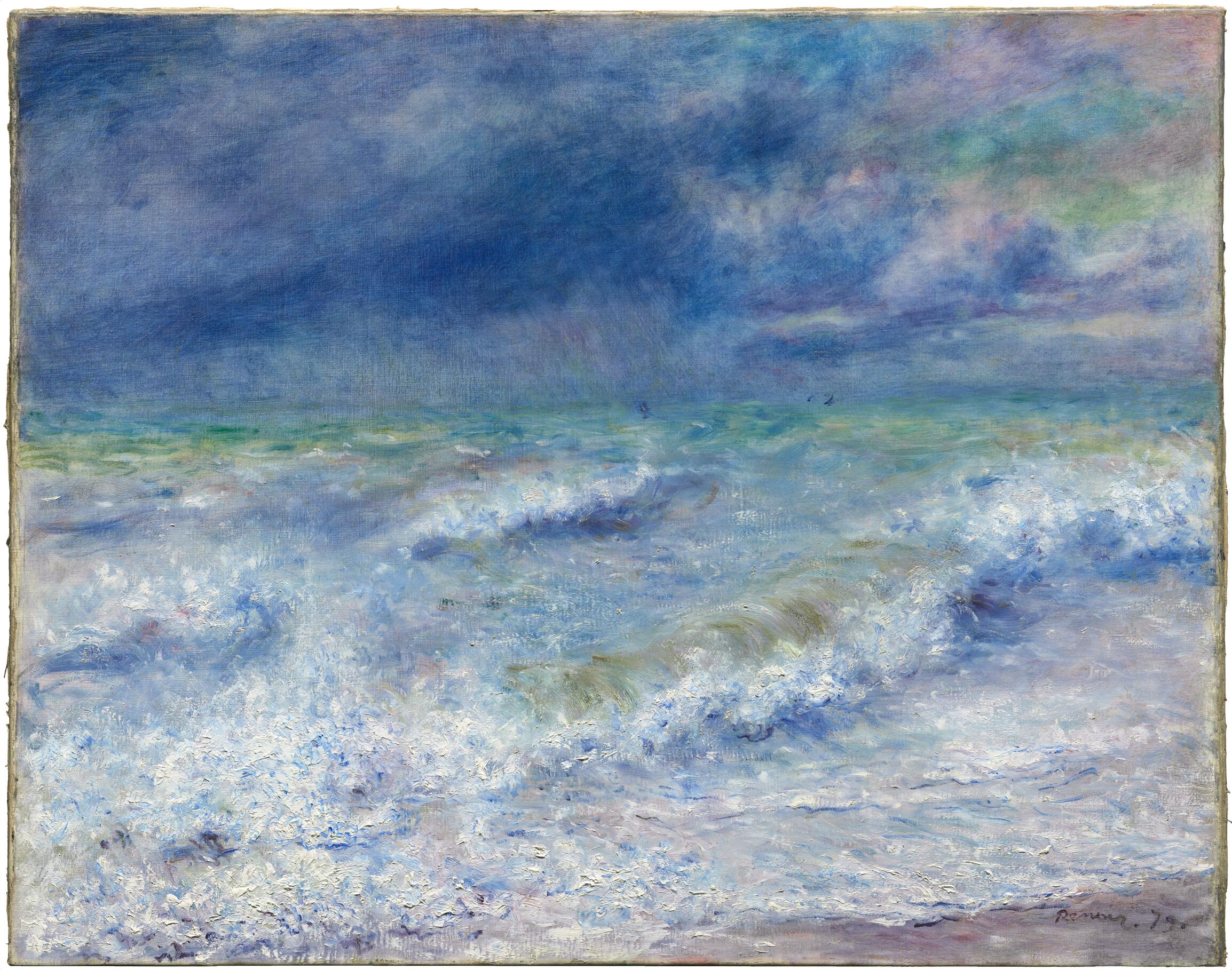

Cat. 8

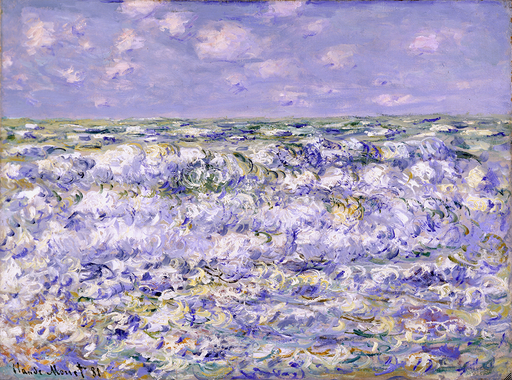

Seascape

1879

Oil on canvas; 72.6 × 91.6 cm (28 1/2 × 36 in.)

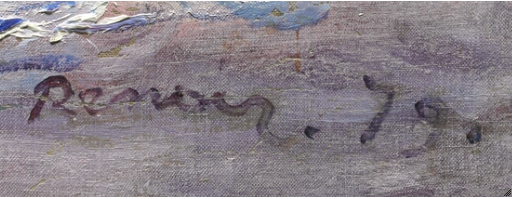

Signed and dated: Renoir. 79. (lower right, in purple paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection, 1922.438

The name Renoir is closely associated with paintings of dancers, boaters, women, the celebration of life, and the enjoyment of leisure, which makes Seascape and its storm-tossed ocean quite unusual and unexpected. For his landscapes, Renoir preferred sunny days with blue skies and calm winds; rarely do we see unsettled weather, and there are only four known winter scenes. Regarding his 1868 painting Skaters in the Bois de Boulogne (fig. 8.1 [Dauberville 110]), he commented to Ambroise Vollard, “I have never been able to stand the cold. . . . Even if you can bear the cold, why paint snow? It is a malady of Nature.” Nonetheless, in Seascape the bleak, overcast sky, churning surf, and dominant cool, blue tone convey a sense of vulnerable exposure and sea-drenched cold with astonishing effectiveness.

Renoir and Normandy in 1879

The year 1879 would prove pivotal in Renoir’s career. In May he sent four works to the Salon, achieving a major triumph with the monumental Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children (1878; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [Daulte 266; Dauberville 239]), which received an excellent hanging position thanks to Madame Charpentier’s sway with the jury. It also won high praise from the critics, albeit tempered by some skepticism about an Impressionist’s return to the fold. This success was followed in June by his solo exhibition of pastels and paintings in the offices of La vie moderne, a journal published by Madame Charpentier’s husband. That summer he returned to Chatou and the Restaurant Fournaise on the Seine to paint landscapes and portraits, and in August he arrived via supply wagon at Château de Wargemont, the Norman estate of Paul Berard. This was the first of many visits to the banking heir, who was well placed to assist the artist in obtaining commissions and new patrons. Earlier that year, Renoir had painted portraits of Berard’s eldest daughter, Marthe, and his son, André, dressed for school and carrying books. Over the course of his stay at Wargemont, Renoir completed portraits of the Berard family and staff in addition to landscapes (see fig. 8.2 [Dauberville 77]), still-life decorations for the château that were in keeping with its eighteenth-century architecture, and two genre paintings of Roma children. Renoir sent one of the genre works, Mussel Fishers at Berneval (1879; Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia [Daulte 292; Dauberville 215]), set on the Berards’ private beach on the English Channel, to the Salon in May of the next year. Two decorative panels illustrating the opera Tannhauser for the Dieppe home of Dr. Émile Blanche, a fan of the composer Richard Wagner, rounded out this lucrative period of commissions.

At this time Renoir also began mentoring Dr. Blanche’s eighteen-year-old son, Jacques-Émile, in painting. This relationship continued over the next two years, even though Madame Blanche had grave reservations about Renoir as a role model. During a visit Renoir made to Dieppe in July 1881, she became so disturbed by the artist’s table manners that she banished him from the household. At another point, she expressed exasperation when she learned that he had done a sunset in ten minutes, calling it a waste of paint.

The Wave as Impressionist Subject

Whether the portraits became too routine, or the bourgeois company of Normandy too constraining, Renoir’s choice of subject in Seascape allowed him an artistic freedom he did not enjoy with figure paintings intended for exhibition or resulting from commissions. Ocean views were already associated with modernism and the avant-garde. The Realist painter Gustave Courbet is reported to have reinvented the storm as a modernist theme in 1869 with a depiction of seawater blowing against the windows of his Étretat beach house. In treating the subject that year, Courbet was aware that he was attempting something new. An ambitious work resulting from his Étretat campaign, Stormy Sea (fig. 8.3), was exhibited to critical acclaim at the Salon of 1870 and became the first of Courbet’s paintings to enter the collection of the Musée du Luxembourg, in 1878. An enormous canvas measuring more than four feet high and six feet wide, and extensively worked with a palette knife, Stormy Sea no doubt made an indelible impression on Renoir, as it did on writer and critic Émile Zola when it was exhibited as part of the French Paintings section of the Exposition Universelle, which opened in May 1878. Angered that Courbet was represented by only one work when multiple paintings by academic painters William Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme were on view in the next gallery, Zola identified Stormy Sea as a rallying point for the avant-garde in his review of the Exposition Universelle. Another of Courbet’s wave paintings, one of a smaller scale, was included in the exhibition of French “modern masters” at Durand-Ruel, June 20–October 15, 1878, an exhibition reportedly intended to compensate for the underrepresentation of the school at the Exposition Universelle.

The sea took on profound metaphorical significance in the writings of Courbet’s contemporaries Charles Baudelaire, Victor Hugo, and Jules Michelet. Though inspired by direct observation, there is a literary sensibility to Courbet’s Stormy Sea, with its single powerful wave about to crash on the shore near wooden herring boats, thus emphasizing the potentially destructive power of nature. Renoir’s Seascape resists such narrative content. Rather, as John House has pointed out, Renoir “seems to have been more concerned with the visual spectacle before him than with any weightier significance in the theme.” Courbet maintained a certain distance from the shore, but Renoir dramatically shifted the point of view by placing the picture plane much closer to the water, thus transforming the viewing experience by emphasizing the visceral—a modern, secular approach to landscape akin to the idea of the individual “sensation,” which Camille Pissarro thought essential to an understanding of Impressionism.

Renoir’s Impressionist colleague Claude Monet also placed the viewer close to the water’s edge in the sea paintings he made in the early 1880s. Though Renoir’s Seascape preceded the first of Monet’s wave paintings by two years, it is useful to compare the two artists’ treatments, as the sea and water are so prevalent in Monet’s work, and he is so closely identified with the wave theme. There are distinct differences in the two artists’ approaches to the wave painting. Monet’s Waves Breaking (fig. 8.4), for example, shows a moment when the clouds are dispersed, allowing the sunlight to create diverse color and light effects. Judging by the indicated wind direction and clouds on the horizon in Seascape, Renoir instead strove to capture the brooding, ominous atmosphere of an approaching storm. The difference in viewpoint of the two paintings is also significant. Renoir positioned the viewer at an angle to the shoreline, looking down, so that the waves are seen following one another to the shore from the left. He depicted waves in various aspects, such as the upward surge of spray on the lower left where seawater crashes into a rock. In contrast, Monet’s canvas looks directly out to sea, waves roll in with rhythmic regularity, and there are fewer reference points for identifying a specific viewing position. The elimination of the shoreline altogether in Waves Breaking represented a bold departure from traditional sea painting and may have owed something to Japanese prints by Hokusai, as well as to Renoir’s example. Monet and Renoir had the opportunity to compare notes on wave painting when they met in Pourville during the summer of 1882 with the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Regardless of whether Renoir shared Monet’s opinions on wave painting at this meeting, his later treatment of the subject in 1882 (fig. 8.5 [Dauberville 798]) took further Monet’s gambit of the absent shoreline. Moreover, by devoting most of that picture to the crest of a single breaking wave, he produced a work that Christopher Riopelle has compared to twentieth-century action painting. Renoir’s 1882 Wave is like a detail of Seascape. The viewing angle is much more restricted, and the horizon has been raised so that the artist could take full advantage of the potential for painterly effects in the visual play of foam and sea spray. At this point, however, Renoir may have decided that the painting of waves lay on a path he did not want to pursue further. After 1882 he made no more pictures of the subject.

Seascape as a Modern Painting Intended for Exhibition and Sale

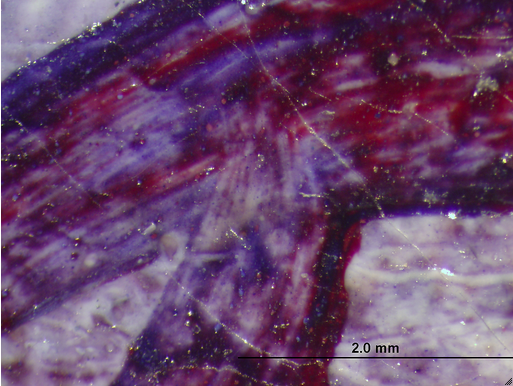

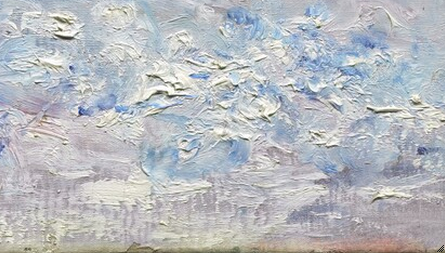

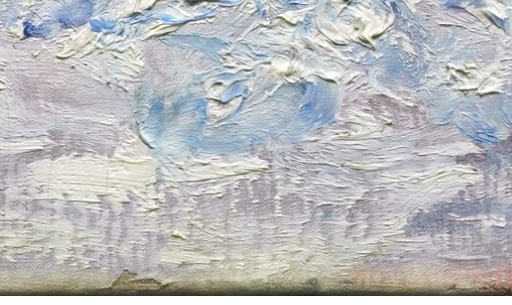

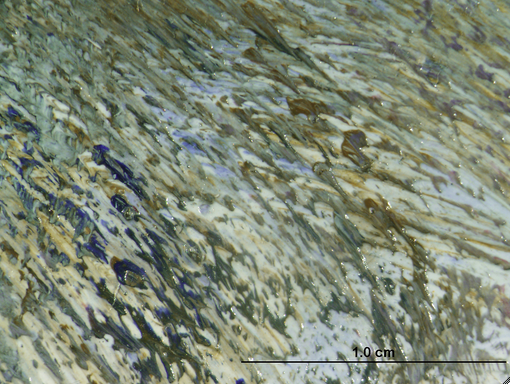

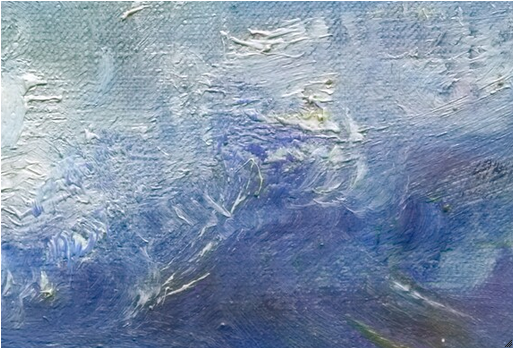

The anecdote about Renoir painting a sunset in ten minutes reinforces the common perception that the Impressionists worked rapidly and without concern for detail or accurate representation of the motif. But close examination of Seascape as outlined in the Technical Report reveals a surprisingly complex working process. In his choice of such a large canvas (corresponding to a no. 30 portrait [[glossary:figure]] standard-size canvas, turned horizontally), Renoir may have been emboldened by Courbet’s earlier wave painting. The size of Seascape’s canvas and its degree of finish suggest that it was intended for public view, possibly for the Salon, to which Renoir had returned in 1878. It seems unlikely that he could have worked in strong winds for any length of time on a canvas of this size without substantial shelter. Thus it seems possible that he only painted the wash-like underlayers of the scene on site and then worked from a smaller sketch, perhaps a second wave painting executed during his stay in Normandy in 1879 on a more diminutive no. 15 portrait (figure) standard-size canvas (fig. 8.6 [Dauberville 149]). This smaller work was painted in the cursory style of a preparatory sketch and shows different lighting conditions and possibly a different location. Most of the brushstrokes are clearly visible; they consist of long strokes with a flat brush, and little attempt was made to differentiate surface textures. Such treatment is typical of rapid execution. By contrast, Seascape displays an astounding variety of brush techniques and colors—subtleties that must have taken some time to consider and apply (fig. 8.7). Given the rather elusive nature of waves, the smaller work could have been executed as a preliminary study that later inspired the artist as he painted Seascape in his studio.

The sky in the top half of Seascape consists of broad washes of cobalt blue over a white ground, resulting in a brilliant atmospheric effect. Rain falling from low-hanging clouds on the horizon was rendered in a sure hand with diagonal strokes from a stiff-bristle brush (fig. 8.8). Renoir applied thicker layers of green and yellow paint over the blue washes along the horizon to suggest the depths of the sea. All these effects seem carefully considered and range dramatically in application technique. In the bottom half of the canvas, as the rolling surf approaches the shore and begins to form waves, the impasto layers gradually build and become more tactile. In the surging spout of foam in the left foreground, white paint was applied with such gusto that one can almost hear the hiss of the foam as it breaks from the cresting waves (fig. 8.9). Rich color accents are present throughout the canvas, including the red tones in the sand under the receding waves, and the rhythmic arcs of green and red defining the volumes of water that propel the frothy crests of the waves, masterfully linking the foreground with the deeper water near the horizon (see Palette in the technical report).

Whether Monet was aware of Renoir’s Seascape and influenced by it remains an unresolved question, as the history of the painting before 1890 is unknown. The first record of the painting is its sale by the art dealer Alphonse Legrand to Durand-Ruel on February 21, 1890, where it was listed simply as Marine and assigned the stock number 2637. Though the painting was an ideal size for the Salon, Renoir did not submit the work to its juries, nor did he include it in his 1883 retrospective on the boulevard de la Madeleine organized by Durand-Ruel. It is possible that Legrand held the work for years unsold or in reserve for his Impressionist painting venture with Knoedler and Company, New York. Alternatively, Legrand may not have acquired Seascape until later, as it is known that Renoir frequently held back his more experimental works, not showing them until they had been “bottled away” for at least a year. Renoir is not as closely identified with the sea as Monet, but like Monet he felt the burden of Courbet’s influence and, when he took on the motif, addressed it in an experimental way.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Renoir began this painting with a [glossary:commercially primed], standard-size [glossary:canvas] with a rich, white [glossary:ground]. Areas of the ground layer appear to have a fairly uniform, diagonal, brushy texture. In some places, a stronger diagonal texture appears in subsequent paint layers, as in the center, where the artist used strokes of thick white or light-blue paint that suggest rain, over which he applied a thin blue [glossary:wash] that sank into the depressions left by the brush. While the thin layers of paint in many parts of the background suggest a wider, stiff-bristle brush that scratched through the thin paint to reveal the ground, the foreground seems for the most part to have been articulated with fine, soft-bristle brushes that left very little impression on the thick paint. Many of the early layers are relatively thin, may have been wiped or rubbed, and were allowed to dry before the later layers were applied, suggesting a limited number of [glossary:wet-in-wet] campaigns. The sky is generally described through translucent films of color, while the foreground waves are smoothly blended, opaque combinations of pale pink, blue, and gray. Thinly painted deep blues and, sometimes, brown hint at the depth beyond the translucent waves. As a final step, Renoir employed heavy [glossary:impasto], often in pure white, to articulate the frothy, breaking waves.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 8.10).

Signature

Signed and dated: Renoir. 79. (lower right, in purple paint) (fig. 8.11, fig. 8.12).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions of the canvas were approximately 72 × 92.5 cm, measuring from the original foldover edge. This probably corresponds to a no. 30 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size (92 × 73 cm) canvas, turned horizontally.

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 30.2V (0.7) × 24.3H (0.9) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft].

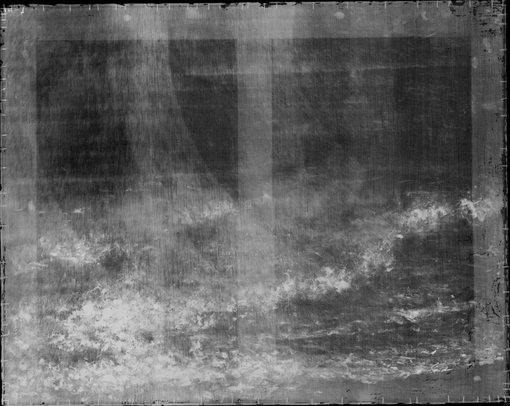

Canvas characteristics

The [glossary:X-ray] shows mild [glossary:cusping] corresponding to the placement of the original tacks. There are also some thread irregularities and double thread faults. The strongest fault appears in the X-ray as a horizontal line across the top of the painting (parallel to and below the top stretcher bar). Here the irregularity of the canvas caught more of the ground layer during preparation, resulting in a denser, more [glossary:radio-opaque] area. Similar horizontal bands are visible throughout the top half of the painting.

Stretching

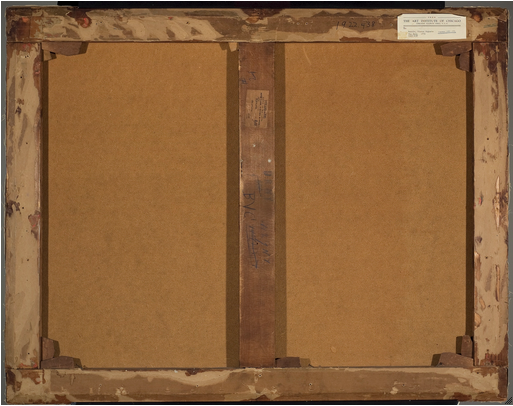

Current stretching: The painting was lined at an unknown date, and its dimensions appear slightly altered (extended horizontally and somewhat shortened vertically) as a result. In addition, a [glossary:hardboard] panel was placed between the lined painting and the stretcher; it is unclear whether the painting is attached to the hardboard (see Conservation History).

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed approximately 6.5 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Though the painting was lined as part of a previous, undocumented conservation treatment, it appears to have retained its original [glossary:stretcher] (see Conservation History). The canvas is tacked to a five-member, keyable, mortise-and-tenon stretcher with vertical [glossary:crossbar] (fig. 8.13). Depth: 1.5 cm.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

The artist began with a commercially primed canvas, with the preparation extending to the edges of the tacking margin. The X-ray shows sweeping, radio-opaque forms that extend from the top edge and curve downward and to the right, possibly suggesting that additional ground material was added to the compositional area by the artist or a color merchant. The shape of the sweeps suggests application with a [glossary:palette knife] (fig. 8.14). Additionally, there is a ridge of ground material at the right foldover edge, where a strong, curving stroke visible in the X-ray—starting along the top edge at the center and sweeping to the right edge—appears to end; it may be excess ground material that was pushed over during application (fig. 8.15). A close look at the surface reveals evidence of a brushy, diagonal texture (fig. 8.16). This texture was probably applied lightly to the surface of the ground after initial application and working, but while the preparation was still wet.

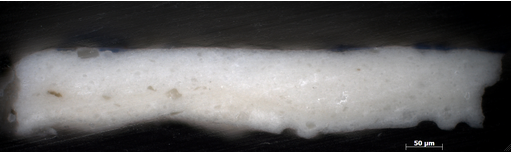

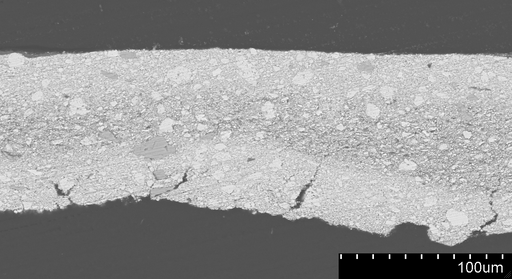

In the cross section, a clear distinction between the separate layers of ground material is not evident; rather, the ground appears to be either a very thick, single layer or two or more layers of a similar composition applied in quick succession (fig. 8.17). The overall thickness of the ground is approximately 10–90 µm.

Color

The ground appears white; no additional colored particles were observed under stereomicroscopic examination of the surface or in cross section (fig. 8.18).

Materials/composition

The ground is predominantly lead white with barium sulfate and small amounts of silicates, calcium compounds, and traces of bone black. The [glossary:binder] is estimated to be [glossary:oil].

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No [glossary:underdrawing] was observed with [glossary:infrared reflectography] or under microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

The work is very thinly painted in many areas, especially in the top half, where Renoir made use of the reflective qualities of the ground and [glossary:underpainting]. The thinness of the paint layer, the sketchy brushwork, and the impasto that is limited to the foreground suggest rapid execution and a limited number of wet-in-wet campaigns. The artist utilized translucent [glossary:pigments] such as red lake, emerald green, and cobalt blue, in addition to thinning his paint with turpentine for a wash (e.g., in the sky), and using additional medium for a glaze-like effect (fig. 8.19). Above the horizon line on the far right, Renoir may have used a cloth or similar tool to wipe away some of the paint, leaving an even thinner, more translucent film of color with a soft, indistinct edge. These kinds of thin applications also form the underlayers throughout most of the foreground, creating a play of colors between the translucent washes and the more opaque paints applied in later stages. In some areas, particularly in the center, Renoir used long, downward diagonal brushstrokes of white or light blue to establish texture and space, then crossed the pattern with dilute blue applied with a stiff-bristle brush. This directional underpaint can be seen in the X-ray, especially in the upper left quadrant (fig. 8.14). The fluid blue paint application produced two effects: first, the blue settled into the depressions of the underlying white paint, accentuating the diagonal texture; and second, the use of a stiff-bristle brush (which cut through the thin paint, exposing the white underpaint and ground) created a much finer, subtler set of diagonals, which sometimes run almost perpendicular to the textured strokes beneath (fig. 8.20). The effect was further complicated where the brush caught the thread tops, creating the illusion of droplets. In other areas of the sky and clouds, the artist applied paint with a stiff-bristle brush and used varying pressure to increase or decrease the presence of the stroke and overall texture.

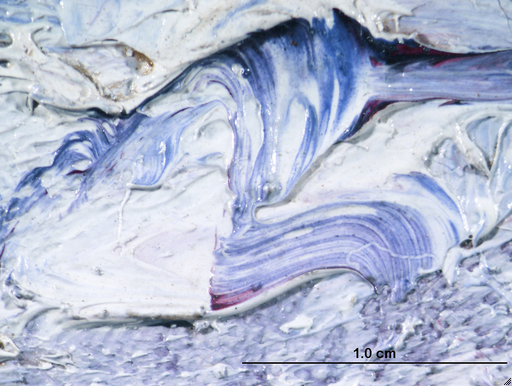

In the foreground, Renoir seems to have initially established the space with thin, opaque, modulated blue-grays, over which he layered extensive impasto with soft-bristle brushes to describe the crash and froth of the waves (fig. 8.21). In some areas, he appears to have used a palette knife initially to spread the paint onto the canvas, and then worked it further with a soft brush (fig. 8.22). Along the bottom edge to the left of center, the artist dragged a brush or possibly a palette knife loaded with thick, dry paint horizontally across the surface, catching just the tops of the vertical threads, to create the illusion of water pulling away from the beach (fig. 8.23). While the painting appears somewhat monochromatic, with shades of blue and blue-green throughout punctuated by the white froth of the waves, Renoir chose to emphasize and add depth to specific locations in the waves with a riot of color applied with a fine-tip brush (fig. 8.24).

Painting tools

Soft- and stiff-bristle brushes with strokes up to 1.5 cm wide; palette knife; possibly cloth for wiping.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cobalt blue, emerald green, iron oxide red and/or yellow, chrome-based yellow, bone black, and red lake.

The observation of a characteristic salmon-colored [glossary:fluorescence] under [glossary:UV] light suggests the presence of red lake in the upper right sky, foreground beach, and waves near the horizon on the left (fig. 8.25).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The work has a [glossary:synthetic varnish] with residues of natural resin in areas of impasto; these residues are readily visible under UV examination, appearing milky yellow-green. The current varnish was applied in 1962 and replaced a discolored [glossary:natural-resin varnish] applied in 1922. It is not clear whether the earliest documented natural-resin varnish was original to the painting.

Conservation History

The earliest documented treatment of the painting was near the time of its acquisition in 1922, when it was cleaned and varnished. A letter from 1921 recommending treatment suggests that the cleaning was a grime cleaning “to be sure the surface is free from smoke and dirt” and makes no mention of an existing varnish or varnish removal. The next documented treatment occurred in 1962. At this time, the painting was described as being lined with glue paste, stretched over a hardboard panel, and tacked to a five-member stretcher. The presence of French newspaper on the verso as an interleaf between the stretcher and a layer of brown paper tape may indicate that the work was first treated in France. Abrasions, [glossary:cleavage], and loss, especially on the right side of the painting, were also noted at this time, and the painting had a discolored natural-resin varnish. During the 1962 treatment, grime and varnish were removed, and areas of cleavage, mostly on the right, were consolidated with wax. Losses were retouched with oil methacrylate paints, and the work was given a synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, inpainting, and a final spray of L-46).

Condition Summary

The work is in good condition, with a stable [glossary:aqueous lining] and hardboard backing between the canvas and the stretcher. The board is slightly warped, causing the bottom left corner of the canvas to pull away from the stretcher and giving the painting a somewhat concave appearance. The stretcher is tapped out slightly, to dimensions a bit larger than the hardboard, and covered almost entirely with brown paper tape. Beneath this tape in many areas are spots of red adhesive that appear to be vermilion- and iron oxide–containing sealing wax, used here to hold an interleaf of French newspaper between the stretcher and the paper tape (fig. 8.26). Cleavage and loss have been noted repeatedly throughout the painting’s history and seem to relate to the ground separating from the canvas (especially on the right). This is probably the result of canvas shrinkage either before or during the lining process. There is also abrasion along raised canvas threads and rebate abrasion.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

Current frame (2004): The frame is not original to the painting. It is an Italian, eighteenth-century, gilt torus frame with a scotia frieze. The frame has water gilding over yellow-orange bole on gesso. The gilding is burnished overall, highly on the torus and ovolos and lightly in other areas. The frame retains its original gilding and glue sizing. The poplar molding is face and side mitered and joined with blind-bridled tenons. Parchment was glued over the face miters prior to gessoing. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is ovolo outer molding; scotia side; torus face with a three-quarter-round profile; fillet; scotia-edged frieze; ovolo; and fillet sight molding (fig. 8.27).

Previous frame (installed mid-1960s, removed 2004): The painting was previously housed in an American (New York), mid-twentieth-century reproduction of an Italian Baroque bolection frame with a centered, spiraled leaf outer molding and a fruit, flower, and husk sight molding. The frame had water gilding over red bole and gesso and was very heavily toned. The carved basswood molding was mitered and nailed (fig. 8.28).

Previous frame (installed by 1933, removed mid-1960s): The work was previously housed in a late-nineteenth–early-twentieth-century, Louis XIV Revival, convex frame with very deeply recessed cast plaster ornament of acanthus leaves at the miters and floral and foliate-scroll centers bracketed by undulating foliage and pendent bellflowers. The frame had water and oil gilding on a dark red-brown bole over gesso and cast plaster. The sides and frieze were burnished, and the ornament was selectively burnished. The gilding was toned with dark raw umber and a white wash and speckled with black and white. The molding was mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, was ovolo with leaf-tip ornament; scotia side; convex face with acanthus leaves at the miters, floral and foliate-scroll centers bracketed by undulating foliage and pendent bellflowers on a quadrillage bed; hollow frieze; ogee with leaf-tip ornament; cove; and fillet with cove sight edge (fig. 8.29).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Acquired from [unknown] by Alphonse Legrand, Paris, by Feb. 21, 1890.

Sold by Alphonse Legrand, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Feb. 21, 1890.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to W. C. Van Horne, Montreal, Apr. 19, 1892, for $1,000.

Acquired by Eugene Glaenzer, New York, by Dec. 14, 1892.

Sold by Eugene Glaenzer, New York, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Dec. 14, 1892.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Potter Palmer, Chicago, Dec. 14, 1892, for $1,250.

By descent from Potter Palmer (died 1902), Chicago, to the Palmer family.

Given by the Palmer family to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1922.

Exhibition History

Possibly Paris, Durand-Ruel, Exposition A. Renoir, May 1892, cat. 100.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 27 (ill.).

Highland Park, Ill., Neison Harris, Mar. 7–May 21, 1975, no cat.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, June 28–Sept. 16, 1984, cat. 120 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 23, 1984–Jan. 6, 1985; Paris, Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, as L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, Feb. 4–Apr. 22, 1985.

Edinburgh, Royal Scottish Academy, Monet: The Seine and the Sea, 1878–1883, Aug. 6–Oct. 26, 2003, cat. 89 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Manet and the Sea, Oct. 20, 2003–Jan. 19, 2004, cat. 117 (ill.); Philadelphia Museum of Art, Feb. 15–May 30, 2004; Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, June 18–Sept. 26, 2004.

London, National Gallery, Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, Feb. 21–May 20, 2007, cat. 45 (ill.); Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, June 8–Sept. 9, 2007; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Oct. 4, 2007–Jan. 6, 2008.

Selected References

Possibly Durand-Ruel, Paris, Exposition A. Renoir, exh. cat. (Imp. de l’Art/E. Ménard, 1892), p. 47, no. 100.

Art Institute of Chicago, Handbook of Sculpture, Architecture, and Paintings, pt. 2, Paintings (Art Institute of Chicago, 1922), p. 69, cat. 845.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Accessions and Loans,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 16, 3 (May 1922), p. 47.

Art Institute of Chicago, “The Potter Palmer Collection of Paintings,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 16, 3 (May 1922), p. 38.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 150, cat. 845.

Ambroise Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record, trans. Harold L. Van Doren and Randolph T. Weaver (Knopf, 1925), p. 239.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 3 (Mar. 1925), p. 32.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute (Continued),” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 4 (Apr. 1925), p. 47 (ill.).

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1929), p. 120, no. 109 (ill.).

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für Freunde und Sammler der Kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 78. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, “Renoir,” in Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler, vol. 28, Ramsden–Rosa (Seemann, 1934), p. 170.

Albert C. Barnes and Violette de Mazia, The Art of Renoir (Minton, Balch, 1935), pp. 74; 75; 451, no. 92.

Duveen Galleries, New York, Renoir: Centennial Loan Exhibition, 1841–1941; For the Benefit of the Free French Relief Committee, exh. cat. (Vilmorin/Bradford, 1941), p. 132.

Frederick A. Sweet, “Potter Palmer and the Painting Department,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 37, 6 (Nov. 1943), p. 86.

Florence Hope, “A Late Renoir Recently Added to the Institute’s Collection,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 39, 7 (Dec. 1945), p. 98.

Ishbel Ross, Silhouette in Diamonds: The Life of Mrs. Potter Palmer (Harper & Bros., 1960), p. 155.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 396.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 53, pl. 39; 160.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 80; 82–83, cat. 27 (ill.).

Andrea P. A. Belloli, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), p. 366.

Sylvie Gache-Patin and Scott Schaefer, “Impressionism and the Sea,” in A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, ed. Andrea P. A. Belloli, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 288; 290; 291, no. 120 (ill.).

Sylvie Gache-Patin and Scott Schaefer, “La mer,” in Réunion des Musées Nationaux, L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), pp. 308; 312–13, no. 120 (ill.).

Nicholas Wadley, ed., Renoir: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, 1987), p. 195, pl. 65.

Michael Howard, ed., The Impressionists by Themselves: A Selection of Their Paintings, Drawings, and Sketches with Extracts from Their Writings (Conran Octopus, 1991), pp. 256 (ill.), 320.

Lesley Stevenson, Renoir (Bison Group, 1991), pp. 100–01 (ill.).

Shigenobu Kimura et al., Seikimatsu no yume / The Dream of Fin de Siècle, Meigo e no tabi / Journey into the Masterpieces 21 (Kodansha, 1992), pp. 70, pl. 3-24; 144.

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), p. 204, fig. 36.

Francesca Castellani, Pierre-Auguste Renoir: La vita e l’opera (Mondadori, 1996), pp. 73, 137 (ill.).

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 33 (detail); 46; 72; 89, pl. 8; 110.

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), p. 121 (ill.).

Michael Clarke and Richard Thomson, Monet: The Seine and the Sea, 1878–1883, exh. cat. (National Galleries of Scotland, 2003), p. 165, cat. 89 (ill.).

Joseph J. Rishel, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir,” in Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener, Manet and the Sea, exh. cat. (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2003), p. 243.

Richard Thomson, “Looking to Paint: Monet 1878–1883,” in Michael Clarke and Richard Thomson, Monet: The Seine and the Sea, 1878–1883, exh. cat. (National Galleries of Scotland, 2003), p. 33.

Juliet Wilson-Bareau and David Degener, Manet and the Sea, exh. cat. (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2003), pp. 248, pl. 117; 261.

Frank Whitford, “A Lasting Impression,” Sunday Times (Scotland), Aug. 10, 2003, p. 17.

Isabelle Cahn, L’impressionnisme, ou l’oeil naturel, L’aventure de l’art (Chêne, 2005), pp. 52 (ill.), 219.

Kyoko Kagawa, Runowaru [Pierre-Auguste Renoir], Seiyo kaiga no kyosho [Great masters of Western art] 4 (Shogakukan, 2006), pp. 33–34 (ill.).

Heather Lemonedes, Lynn Federle Orr, and David Steel, eds., Monet in Normandy, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/North Carolina Museum of Art/Cleveland Museum of Art/Rizzoli, 2006), pp. 33; 34, fig. 21.

Colin B. Bailey, “‘The Greatest Luminosity, Colour and Harmony’: Renoir’s Landscapes, 1862–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), p. 65. Translated as Colin B. Bailey, “‘Un maximum de luminosité; de coloration, et d’harmonie”: Les paysages de Renoir, 1862–1883,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), p. 65.

Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, eds., Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), pp. 2–3 (detail); 4; 199–202, cat. 45 (ill.); 256. Translated by Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer as Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), pp. 2–3 (detail); 4; 199–202, cat. 45 (ill.); 256.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, with the collaboration of Camille Frémontier-Murphy, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 1, 1858–1881 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), p. 211, cat. 152 (ill.).

Robert McDonald Parker, “Topographical Chronology 1860–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), p. 276. Translated as Robert McDonald Parker, “Chronologie,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), p. 276.

Charles Stuckey, “The Predications and Implications of Monet’s Series,” in The Repeating Image: Multiples in French Painting from David to Matisse, ed. Eik Kahng, exh. cat. (Walters Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 122–23, n. 22.

Richard R. Brettell and C. D. Dickerson III, From the Private Collections of Texas: European Art, Ancient to Modern (Kimbell Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2009), p. 302, fig. 2.

John House, The Genius of Renoir: Paintings from the Clark, with an essay by James A. Ganz, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Museo Nacional del Prado/Yale University Press, 2010), p. 74.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 2637, livre de stock Paris 1884–90

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 900, livre de stock New York 1888–93

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 1011, livre de stock New York 1888–93

Other Documents

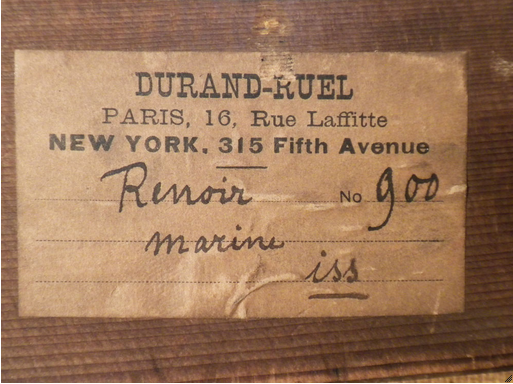

Label (fig. 8.30)

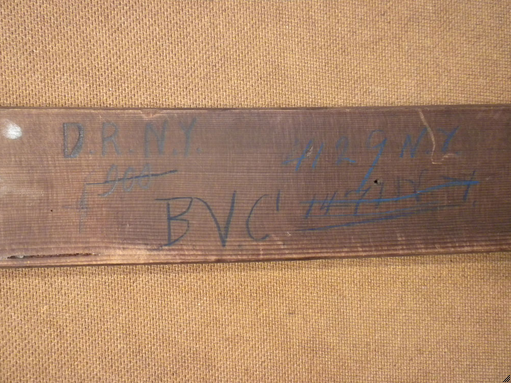

Inscription (fig. 8.31)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

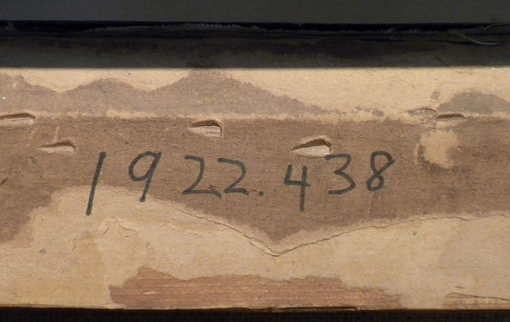

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (black marker)

Content: 1922.438 (fig. 8.32)

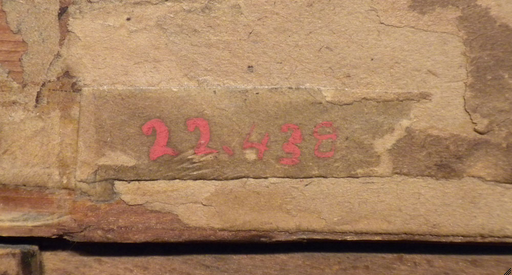

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (red paint)

Content: 22.438 (fig. 8.33)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: [#] 21 (fig. 8.34)

Pre-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: DURAND-RUEL / PARIS, 16, Rue Laffitte / NEW YORK, 315 Fifth Avenue / Renoir No 900 / marine / iss (fig. 8.30)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: D.R. N.Y. / 900 (fig. 8.31)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: BVC1 1471NY (fig. 8.31)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 4129N.Y. (fig. 8.31)

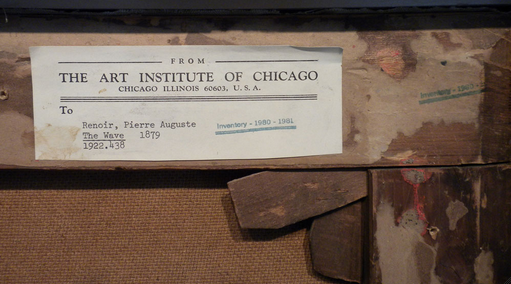

Post-1980

Label

Location: stretcher bar

Method: printed and typed label with blue stamp

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / To / Renoir, Pierre Auguste / The Wave 1879 / 1922.438 / [blue stamp, lower right] Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 8.35)

Stamp

Location: stretcher bar

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 8.35)

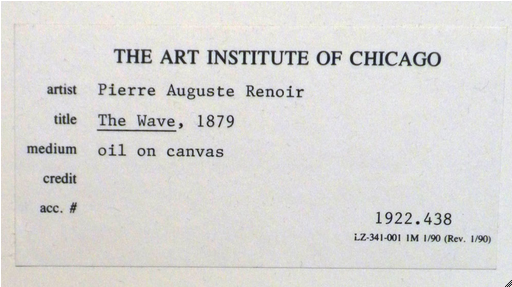

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Pierre Auguste Renoir / title The Wave, 1879 / medium oil on canvas / credit / acc. # 1922.438 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 8.36)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: Monet: THE SEINE AND THE SEA—Vétheuil and Normandy, / UK, Edinburgh, Royal Scottish Academy Crate 21 TELNG 03.068 / 089 / Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Seascape (The Wave) / Oil on canvas / 64.80 x 99.20 cm / USA, Chicago, The Art Institute (fig. 8.37)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / Manet and the Sea / The Art Institute of Chicago: 10/20/03–1/4/04 / Philadelphia Museum of Art: 2/15–5/30/04 / Van Gogh Museum: 6/18–9/26/04 / AIC/PMA/VGM / Cat. #: 117 / Pierre Auguste Renoir, French; 1841–1919 / SEASCAPE, 1879 / oil on canvas / 64.8 × 99.2 × cm., (25 1/2 × 39 1/8 in.) / The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA / Crate No 76 (fig. 8.38)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: THE NATIONAL GALLERY / Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN / Telephone 020 7839 3321 / Exhibition: Renoir Landscapes 1865–1881 / Venue(s): The National Gallery (London) 21/02/2007 to 20/05/2007 / National Gallery of Canada 08/06/2007 to 09/09/2007 / Philadelphia Museum of Art 30/09/2007 to 06/01/2008 / Number: X5663 Cat No: 45 / Artist: Pierre-Auguste RENOIR / Title: The Wave / Credit Line: The Art Institute of Chicago, Potter Palmer Collection, 1922.438 (fig. 8.39)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (B+W 486 UV/IR cut MRC filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

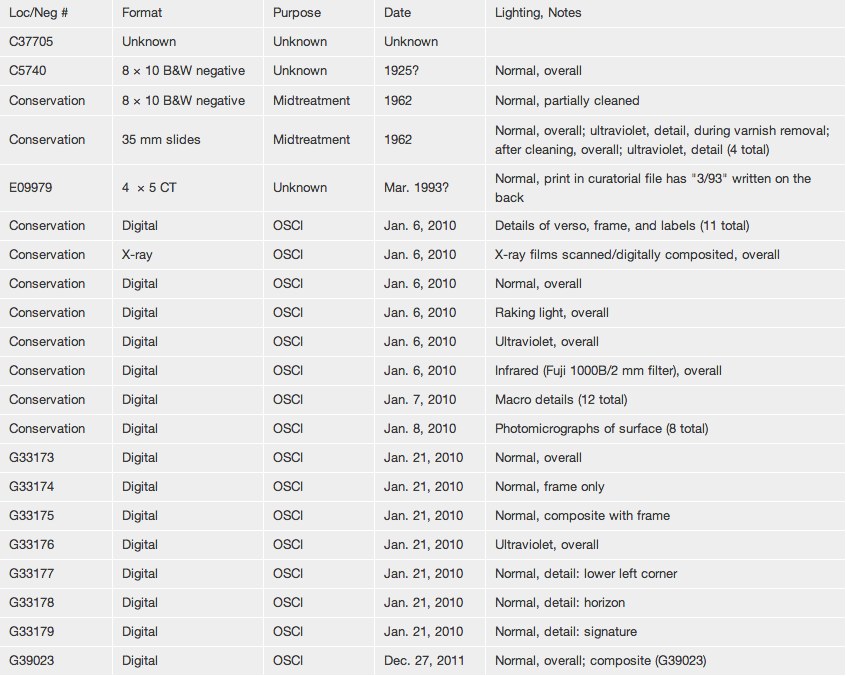

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 8.40).