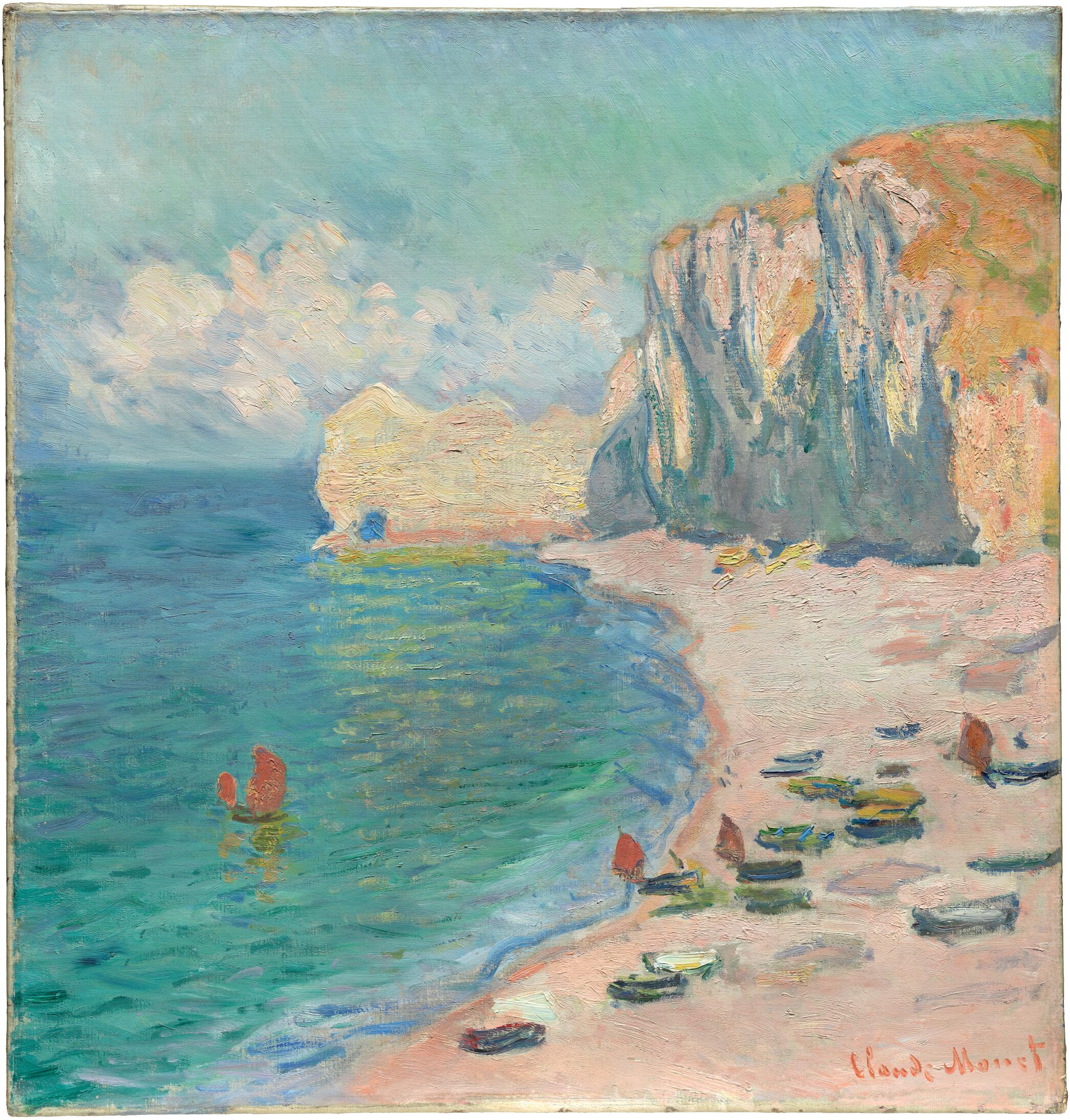

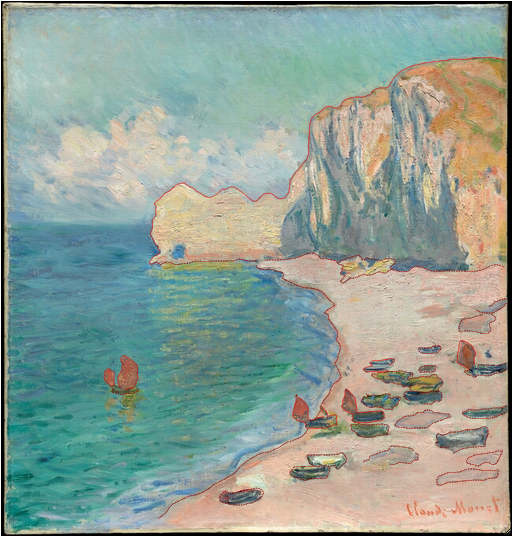

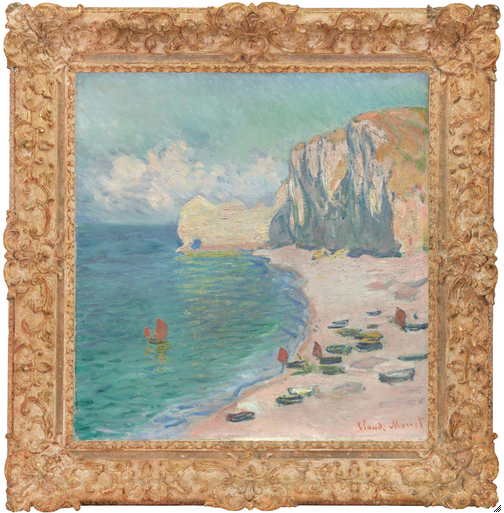

Cat. 21

Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont

1885

Oil on canvas; 69.3 × 66.1 cm (27 1/4 × 26 in.)

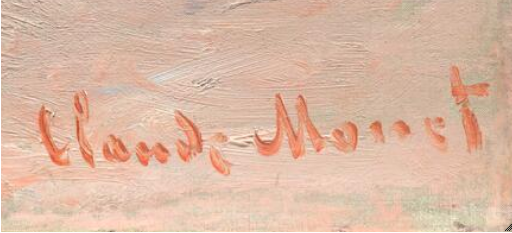

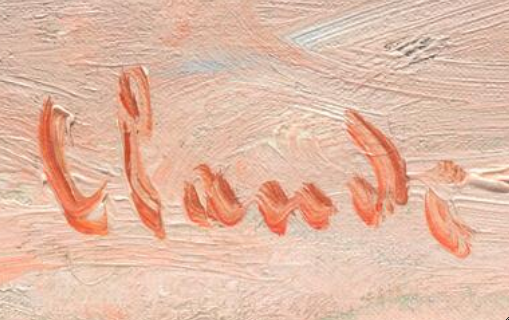

Signed: Claude Monet (lower right, in light-orange-red paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mrs. John H. (Anne R.) Winterbotham in memory of John H. Winterbotham; Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1964.204

Monet at Étretat in 1885

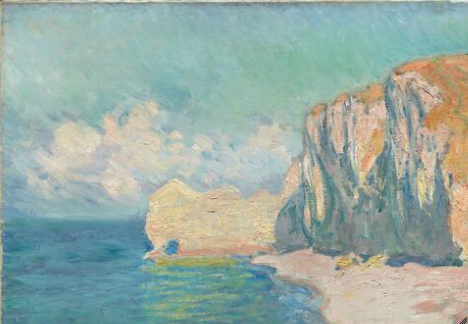

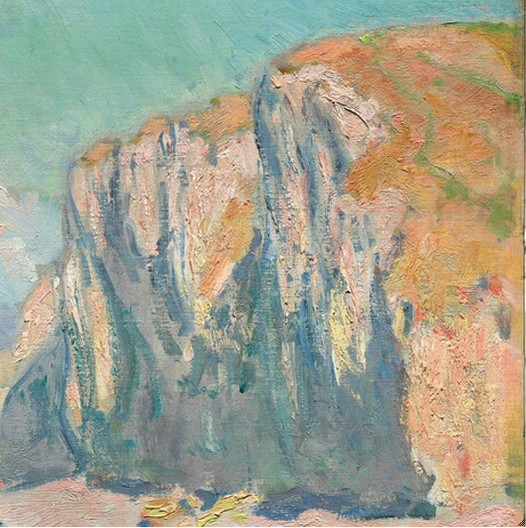

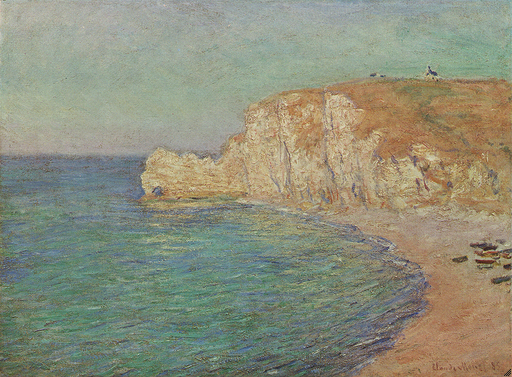

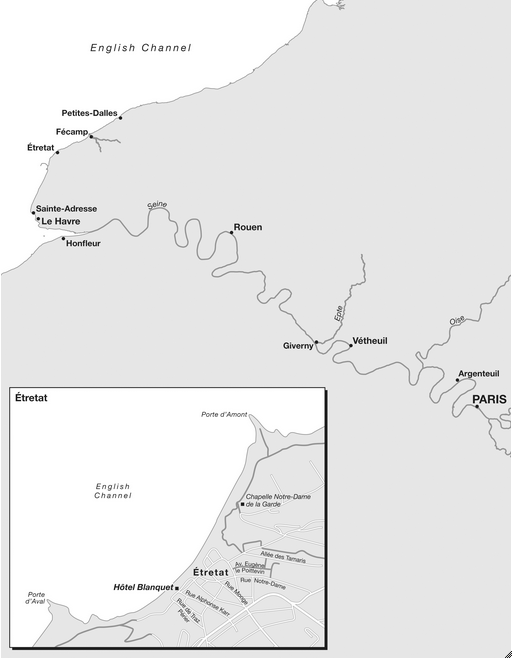

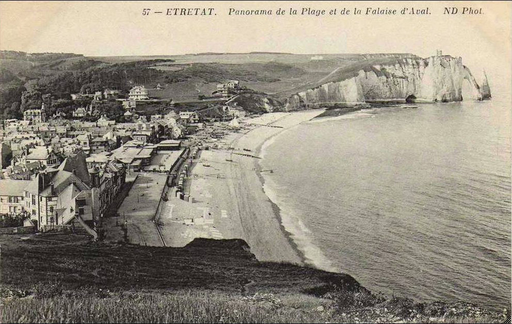

Claude Monet painted this classic tourist view of one of the two extraordinary falaises (“cliffs”)—Porte d’Amont, the upstream portal to the northeast, and Porte d’Aval, downstream to the southwest—that flank the bay at Étretat on the coast of Normandy (fig. 21.1). Monet spent several months in this scenic area on a working vacation, arriving with his two sons, companion Alice Hoschedé, and her six children. A precise sequence cannot be determined for the fifty-one canvases initiated between mid-September when the family arrived and Monet’s departure in mid-December—which depict topographical views of cliffs, landscapes, and boats on the beach of galets (shingles, pebbles). Despite staying in Étretat for three months, Monet himself was unsure whether he had anything finished as he prepared to leave. He returned in February 1886 with the intention of completing what he had started a few months earlier, but scholars agree that this was not a productive trip; by month’s end he was back at Giverny. The majority of paintings undertaken in the fall were either retouched or reworked in his studio.

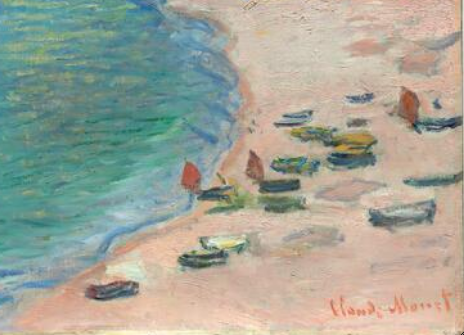

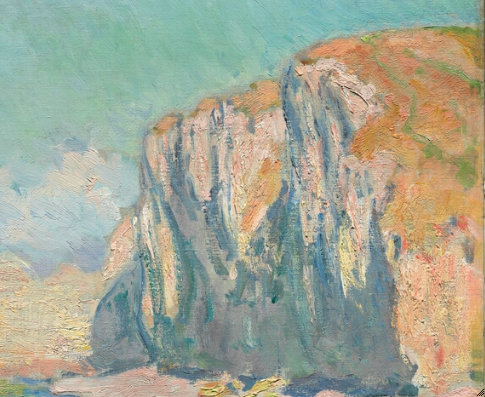

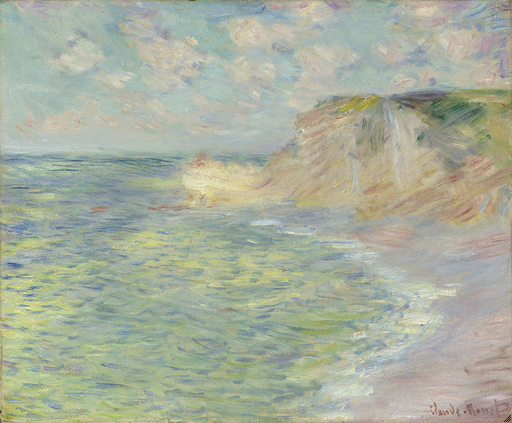

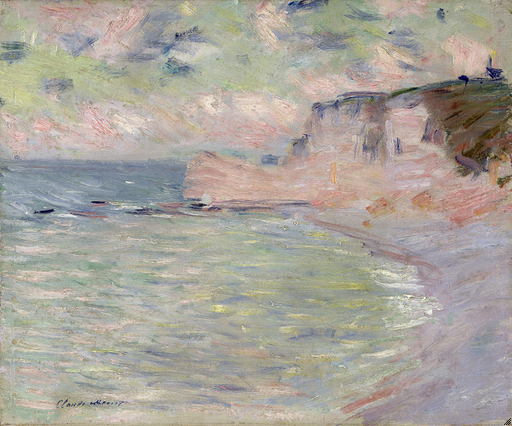

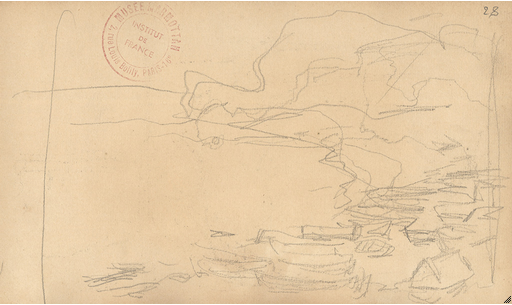

Of the Étretat canvases, only five were immediately sold, all in December 1885. One of the works purchased at this time, also titled Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont (fig. 21.2 [W1009]), depicts a viewpoint similar to the one in the Art Institute composition and two others (fig. 21.3 [W1010] and fig. 21.4 [W1011]). This version of the Falaise d’Amont was the most finished of the four, and was preceded by a pencil sketch (fig. 21.5 [D266]) of the cliff’s proportions as viewed from the Falaise d’Aval. The sketched horizon and cliff line resemble those seen in the painting; the wider beach area and boats are elements similar to those in the Chicago painting.

Although the spectacular vistas required rigorous hiking along designated paths (including a descent down a ladder that was, according to one contemporary guidebook, “impassable” for women), Monet was undeterred and enthusiastic. This was contrary to the tentativeness and self-consciousness he had voiced in letters home to Alice during his painting trip along the Italian Riviera the previous winter. Étretat was intimately familiar to the artist, who had grown up in Le Havre (fig. 21.6). He had painted in Étretat several times beginning in 1868, as had the older artist Gustave Courbet, whose dramatic scenes of the majestic cliffs Monet admired and reinterpreted (fig. 21.7 and fig. 21.8).

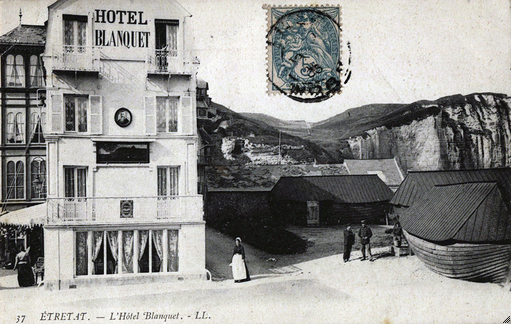

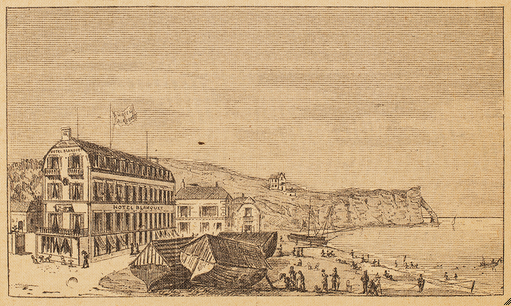

From the Hôtel Blanquet

The 1885 Étretat campaign can be divided into two phases. Monet arrived there with his family in mid-September, staying at a villa owned by the baritone and modern art collector Jean-Baptiste Faure. According to the writer Guy de Maupassant’s eyewitness account of the Monet family’s visit, which overlapped with his own, Monet was more than an artist; he was a “hunter,” whose children were put into the service of his art, carrying canvases up and down the cliffs. When his family departed on October 10, Monet took up residence at the Hôtel Blanquet (fig. 21.9 and fig. 21.10), one of Étretat’s oldest hotels. He had stayed at this beachfront establishment during his earlier 1883 trip. In the course of the second phase of his campaign, Monet worked intensely, sometimes keeping six different canvases going in the same day.

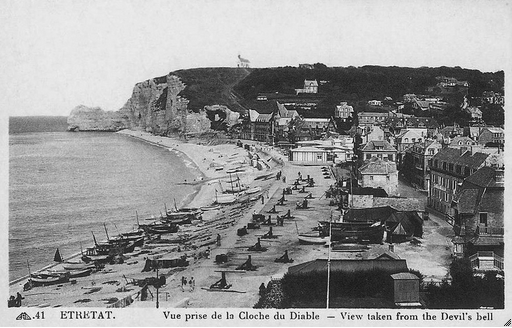

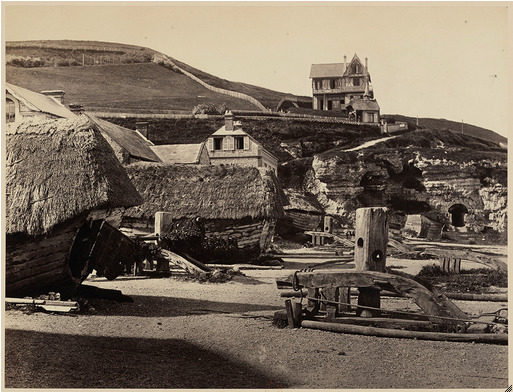

From his hotel room, Monet could see the Falaise d’Aval to the left, but the Falaise d’Amont, at the other end of the beach, would not have been visible; in order to paint this cliff he needed to venture outside. For a group of works Monet painted during his 1883 campaign showing a view of the Falaise d’Amont (e.g., fig. 21.11 [W828]), he climbed the path directly behind the hotel leading up to the summit of the Falaise d’Aval. The artist returned to a very similar spot along the same path in 1885 for the Chicago painting and its three related compositions. According to a recent reconstruction of the topographical and meteorological conditions in Monet’s paintings completed during his 1883 and 1885 campaigns, Monet’s location for the Chicago painting was on a promontory called la Cloche du Diable (Devil’s Bell), above the southwest end of the main Étretat beach, where the path just begins to climb up to the top of the Falaise d’Aval. This promontory is around an ornate residence, which is visible in a postcard from about 1900 (fig. 21.12) and in a photograph by Louis-Alphonse Davanne (fig. 21.13). The Cloche du Diable was the subject of tourist souvenir postcards (fig. 21.14), and is also the vantage point for a modern photograph (fig. 21.15) overlooking the main beach: both show the elevation of the Art Institute’s view of the Falaise d’Amont.

From this location Monet took in not only the beach but also the sky above the summit as well as the porte, which, in the Chicago painting, appears as a kind of blue tunnel. The Art Institute’s version is the only one of the four comparable 1885 compositions, however, that does not show the little chapel on the clifftop, Notre Dame de la Garde, dedicated to the Virgin Protectress of mariners. It is also painted from a vantage point that is less elevated than the three other canvases, one perhaps more comparable to the 1883 Falaise d’Amont group (see, e.g., fig. 21.11); this slightly lowered perspective allowed Monet a fuller view of the beach but a less-expansive treatment of the summit, which extends the beach and eliminates the chapel. The changes in the framing of the composition are due to Monet’s use of a nearly square, nonstandard canvas format, which he would use later for series such as Mornings on the Seine (see cat. 36 [W1475]), which were more readily associated with his interest in series, decoration, and ensembles.

Nature into Art, Sketch into Tableau

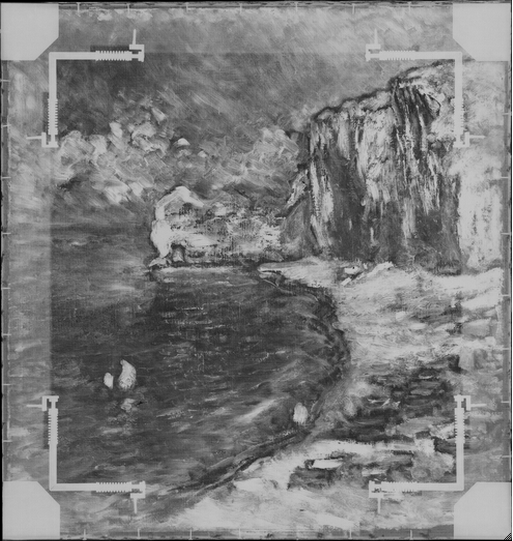

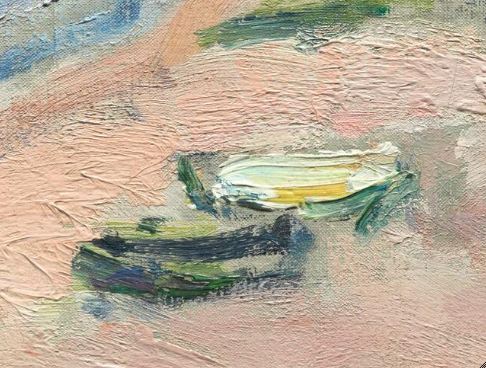

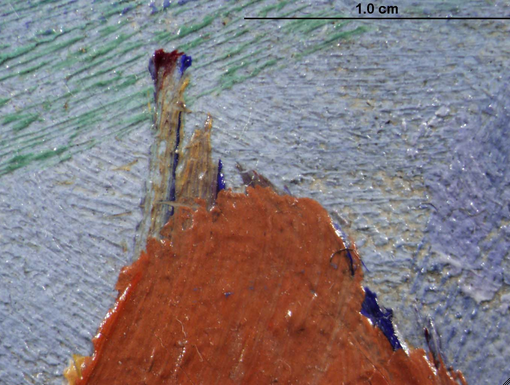

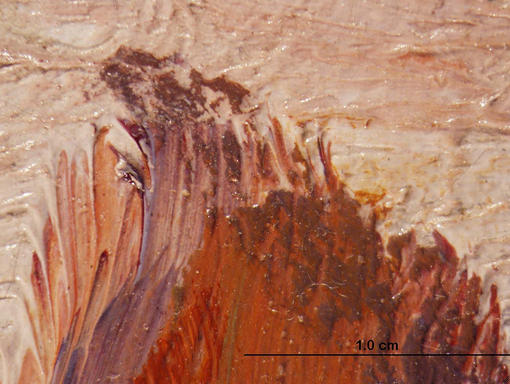

Among the versions of the Falaise d’Amont from the 1885 campaign, the Chicago painting is distinguished by its livelier distribution of boats, both those on the water and those decoratively arranged on the beach, and by its festive pink-and-blue palette, the same colors that he employed to capture “fairylike” Bordighera on the Italian Riviera (see cat. 20). Initially appearing as a one-off sketch from a morning’s session, it is deceptively simple. The surface of the painting shows the artist’s calculated reworking; the paint application ranges from heavy impasto and wet-on-wet brushstokes over areas where the ground is visible (fig. 21.16), to thinly painted areas created by a dry brush dragged over the canvas. As seen in an overlay detail of the X-ray and natural-light images (fig. 21.17), Monet left negative space for several of the boats, suggesting that these were part of his initial composition, while other boats painted directly on top of the already painted-in beach were later adjustments. Transmitted-light imaging (fig. 21.18) shows the areas of thinnest paint application to be around the contours of the coastline, where Monet went back in after the initial outlines had dried and applied a decorative rickrack edging to suggest waves lapping at the beach’s edge. In other thinly painted areas the ground shows through, including around the boats on the beach and where the sky meets the cliff, which contrasts with the thick impasto Monet used to suggest the clouds.

The signature, applied wet-into-wet at bottom right, underscores the spontaneous, improvisational quality and the lightness of touch throughout. While there is evidence of underdrawing, the work gives the impression of a painted sketch that involved minimal planning. It might have been later reinforced and enhanced in the studio; this was perhaps one of the paintings that Monet worried might be perceived as being too unfinished, although his choice of a square format and slightly lower vantage point suggests that this was a special, experimental canvas that required a different approach and treatment.

Monet undoubtedly worked quickly to capture what appears to be a perfectly calm sea at low tide. With its thick, impasted brushstrokes of yellow and white defining the chalky, sun-drenched cliffs, Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont approaches what Maupassant described as Monet’s ability to “catch a sparkling shaft of light on a white cliff and fix it to a rush of yellows that gave an eerily precise rendering of the blinding, ineffable effect of its radiance.”

In addition to capturing atmospheric effects, Monet was careful to articulate the essential topographical eccentricities of the area. A modern photograph shows chalk deposits on the beach (e.g., fig. 21.19), the result of flint discharged over time from the limestone cliffs. The shape and location, at the base of the cliff, of the yellow and orange strokes in the Art Institute’s composition (fig. 21.20) could suggest a deposit similar to what can be seen in the photograph. These strokes, which at first appear (or could be read) as boats within the logic of the scene, change meaning when weighed against the known topography and geological peculiarities of the area—specificities that Monet would have been aware of and that would have authenticated his choice of site.

As with most of the paintings Monet undertook of scenic views along the coast of Normandy, Monet eschewed portraying Étretat as a tourist destination, excluding the Hôtel Blanquet seen in postcards (fig. 21.9) and only hinting at the fishing trade. Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont both celebrates and transforms the guidebook descriptions of the site. With the exception of the picturesque chapel, which Monet eliminates in order to depict a longer stretch of the seashore, everything notable about the site—the dramatic cliff, the whiteness of its pebble and slate beach, the spectacular viewpoint from the opposite cliff—is here presented anew as “a famous place, seen in a new light.”

Gloria Groom

Technical Report

Technical Summary

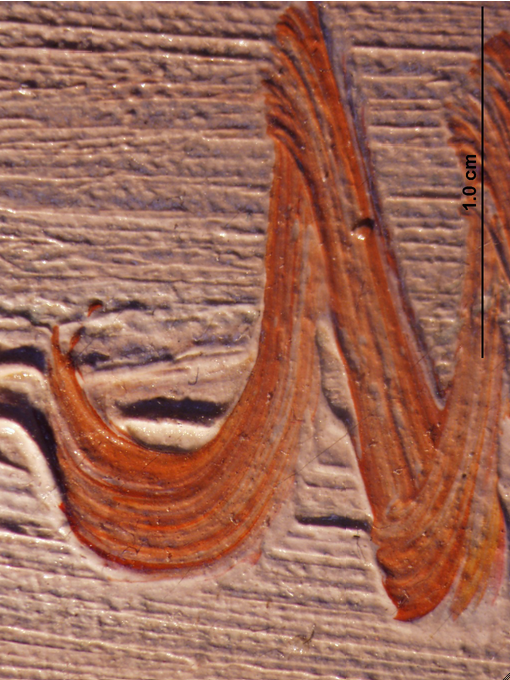

Claude Monet’s Étretat: The Beach and the Falaise d’Amont was painted on a non-standard-size, pre-primed linen canvas. There is a stamp from the color merchant Vieille & Troisgros on the back of the canvas. The ground consists of a single, off-white layer. The canvas weave exhibits a warp-thread match with Monet’s The Departure of the Boats, Étretat (1885; 1922.428 [W1025]) (cat. 23) and Rocks at Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île (1886; 1964.210 [W1095]) (cat. 24), suggesting that the fabric for these paintings came from the same bolt of fabric. The artist used some preliminary drawing to sketch in the composition. Charcoal particles were observed microscopically along the shoreline and the edge of the cliff. The boats were added to the beach at different stages of the painting process: many were incorporated in the initial lay-in of the composition and were painted directly over the ground layer, while others were added on top of the beach. Two boats appear to have been painted out of the composition near the lower right corner. The painting appears to have been executed relatively rapidly, consisting, for the most part, of a buildup of wet-on-wet paint application. The signature was added into the wet paint. One boat and some final touches were added when the paint surface was dry.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 21.21).

Signature

Signed: Claude Monet (lower right corner, in light-orange-red paint) (fig. 21.22). The signature was applied while the underlying paint of the beach was still wet (fig. 21.23, fig. 21.24).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions were approximately 68.5 × 65 cm. This almost-square format is not a standard size and was probably custom ordered.

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 28.6V (0.7) × 27.1H (0.7) threads/cm. The horizontal threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the vertical threads to the weft. The canvas is a warp-thread match with two other Monet works, The Departure of the Boats, Étretat (1885; 1922.428 [W1025]) (cat. 23) and Rocks at Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île (1886; 1964.210 [W1095]) (cat. 24).

Canvas characteristics

There is pronounced cusping along the top edge, mild cusping on the left and right edges, and very faint cusping along the bottom edge.

Stretching

Current stretching: Dates to the 1967 conservation treatment. The canvas is attached with copper tacks spaced approximately 6.5–8 cm apart (see Conservation History).

Original stretching: Tack holes, spaced approximately 6.5–9 cm apart, correspond to cusping in the canvas.

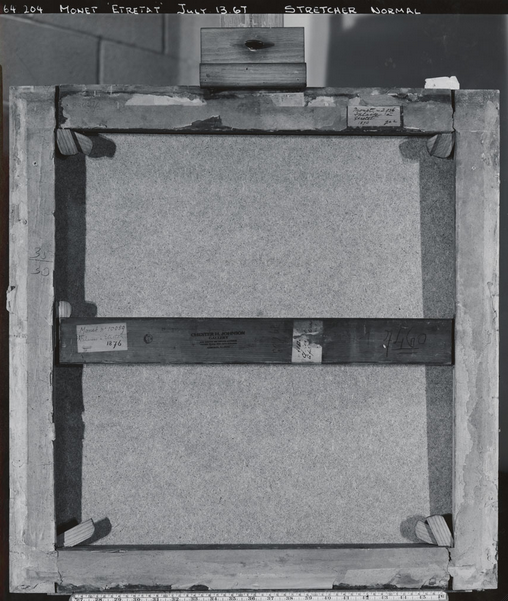

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Four-membered ICA spring stretcher. Depth: 2.7 cm.

Original stretcher: Discarded. The pre-1967-treatment stretcher, documented in a 1967 photograph, was probably the original stretcher. It consisted of five members, including a horizontal crossbar, with butt-ended joints and space for ten keys (fig. 21.25). Depth: Not documented. A crease in the tacking edges where the canvas appears to have been folded over the back edge of the original stretcher indicates that the original stretcher depth was approximately 1–1.5 cm.

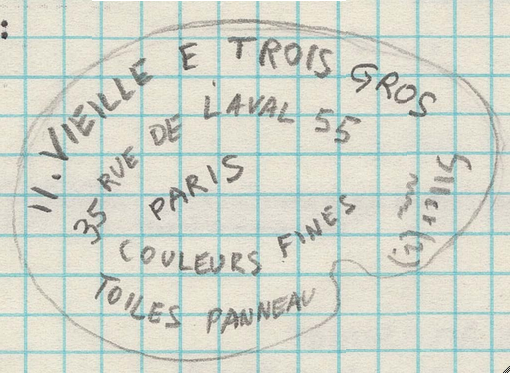

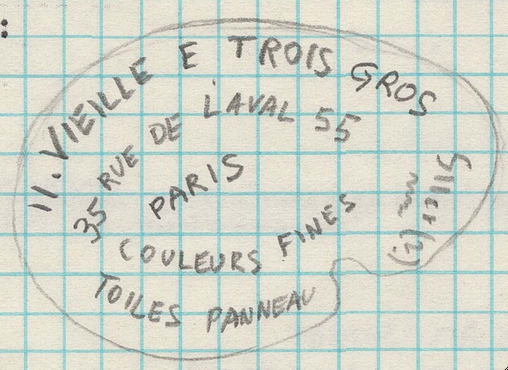

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

There is a supplier’s stamp on the back of the original canvas. Before the painting was lined in 1967 (see Conservation History), a tracing of the stamp was made; the text (not completely legible) is contained within a palette-shaped frame:

II. [sic] VIEILLE E TROIS GROS [sic] [. . .] / 35 RUE DE LAVAL 55 [] / PARIS / COULEURS FINES / TOILES PANNEAU [sic] (fig. 21.26)

The transmitted-infrared image shows traces of the stamp, which is located in the upper right quadrant of the painting (fig. 21.27).

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

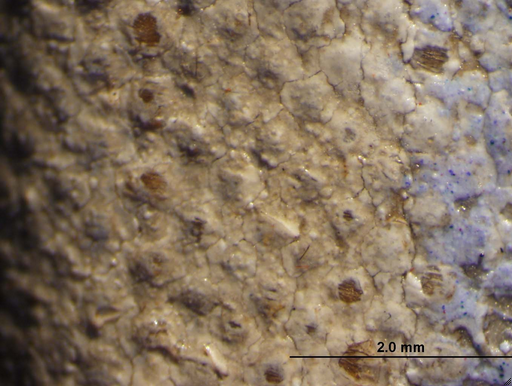

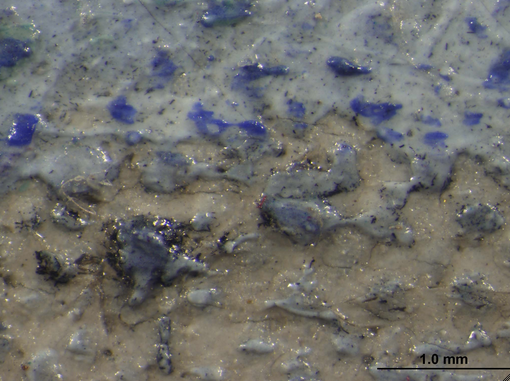

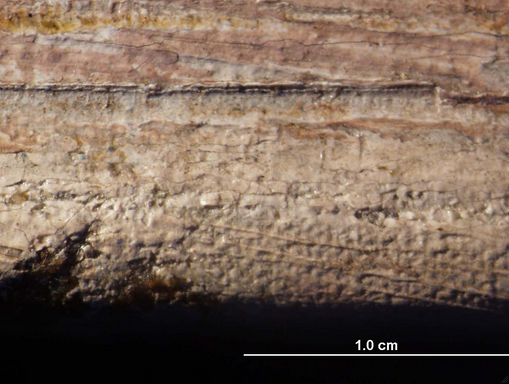

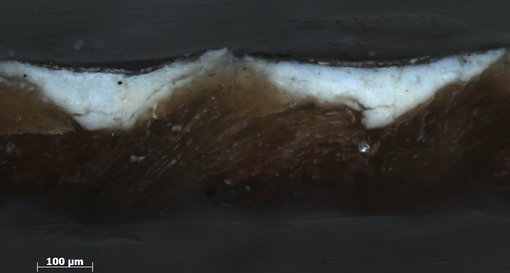

The ground layer extends to the edges of all four tacking margins, indicating that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed fabric that was probably commercially prepared. The ground layer is quite thin and brittle. It ranges from 10 to 100 µm in thickness (fig. 21.28).

Color

The ground is off-white with some black and red particles visible under magnification. There are numerous relatively large white clusters in the ground layer, which give it a slightly bumpy surface (fig. 21.29). Where the ground layer is exposed on the painted surface, the appearance is considerably grayer compared to the exposed ground on the tacking margins (fig. 21.30). This seems to be related to discoloration possibly caused by a combination of starch-paste residues from the facing used in the 1967 lining (see Conservation History) and imbibed dirt, rather than any kind of intentional toning layer.

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the ground contains lead white and calcium carbonate (chalk) with traces of bone black, iron oxide, alumina, silica, and various silicates. Binder: Oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR); however, some black particles were observed microscopically along the shoreline and the edge of the cliff. The black particles often appear to have been picked up and mixed into the paint applied on top (fig. 21.31).

Medium/technique

Charcoal.

Revisions

The charcoal particles correspond to the edges of the compositional forms as painted.

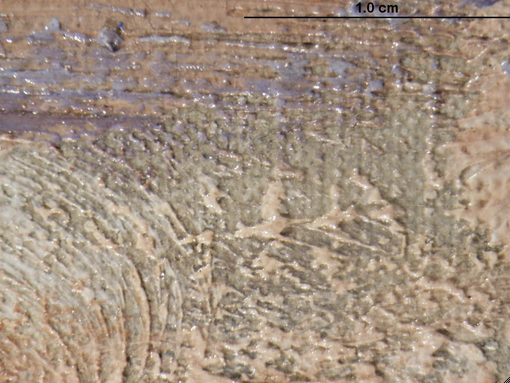

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revision

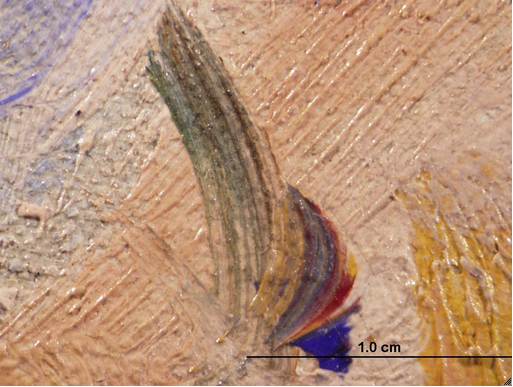

The work was painted largely wet-in-wet, with a few final touches, such as some of the strokes delineating the ripples of the water, added when the underlying layers were surface dry. Each of the main compositional areas (beach, cliffs, sea, and sky) was built up separately, and areas of exposed ground are readily apparent along the junctures of these compositional elements (fig. 21.32), for example, where the water meets the beach (fig. 21.33) and where the sky meets the upper edge of the cliff (fig. 21.34). In some areas, the artist has gone back in with strokes of paint that conceal these junctures, such as the deep-blue, horizontal strokes at the base of the cliff (fig. 21.35). At the left horizon, the strokes of the water and the sky are more blended, with no clear delineation where one ends and the other begins except for the tonal transition (fig. 21.36). In some areas, multiple colors were picked up on the brush and applied in strokes of incompletely mixed paint (fig. 21.37, fig. 21.38).

Most of the boats on the beach were planned from early on in the painting process, with the beach painted up to and around them. Areas of exposed ground between these boats and the paint of the beach are clearly visible (fig. 21.39). Some boats were added later in the painting process; for example, the “simple” boats farthest away on the beach—consisting of two or three horizontal strokes of blue and reddish-purple paint—were added wet-in-wet over the paint of the beach (fig. 21.40). The boat that overlaps the water’s edge was painted wet-in-wet into the pale-pink paint of the beach (fig. 21.41). Its sail was added over the thin, blue paint of the water’s edge when it was already surface dry (fig. 21.41); the tip of the mast, on the other hand, drags through the wet paint of the green diagonal stroke in the water above the sail (fig. 21.42). The boat in the left foreground (closest boat), on the other hand, was added on top of the beach when the beach paint was surface dry; it probably represents one of the final additions to the painting (fig. 21.43). The boat with the open sail at the right edge of the composition was painted directly over the ground in places but over the paint of the beach in others (fig. 21.44). For example, the lower part of the sail and the upper contour of the boat are directly on top of the ground, whereas the upper part of the sail was applied wet-in-wet over the thick pinkish-white stroke of the beach (fig. 21.45). All of these observations suggest that the artist moved back and forth between the various elements of the composition to some extent, probably working quite rapidly.

Where the waves hit the shoreline, the paint of the water consists mainly of admixtures of blue and white, with the ground layer left exposed in several places. The long, undulating strokes that run parallel to the shoreline help to convey the movement of the waves (fig. 21.46). Further away from the shoreline, the artist used more intensely colored strokes of blue, blue-green, and green paint; in the distance, the paint is more purplish-blue. Touches of yellow paint, mixed with blue, green, and white are used to create the reflection of the cliff in the water (fig. 21.47). The boat on the water seems to have been applied when the underlying greenish-blue paint of the water was surface dry. A few final blue strokes were added later to the water, coming up over the orange-red paint of the sails (fig. 21.48). These sails, like the others in the painting, are quite thickly built up, as evidenced by their relative radio-opacity in the X-ray and consist of a layering of colors, from lighter to more intense, with breaks in the upper strokes revealing the lighter hue beneath (fig. 21.49).

The sky seems to have been painted in two zones: the clouds above the horizon were painted in with relatively thick strokes of incompletely mixed color, and the upper green-blue area of sky was applied with some of those strokes extending down over the clouds (fig. 21.50). The artist used predominantly diagonal strokes in both areas. Paint from the sky comes down slightly over top of the upper edge of the tall cliffs (fig. 21.51). Although these cliffs appear to be quite thickly painted, it is really only the lighter areas, rich in lead white paint, that are composed of thick, impasted brushstrokes (fig. 21.52, fig. 21.53). The bluish-gray paint of the shadowed areas, on the other hand, is relatively thinly applied with exposed ground between brushstrokes (fig. 21.54).

Two areas consisting of dark brushstrokes (mixtures of blue and red paint) near the lower right corner just above the signature, were subsequently covered over by the pale-pink paint of the beach. These underlying forms are similar to some of the more cursorily painted boats and may have been conceived as boats themselves before being painted out; these are slightly more visible in the infrared image (fig. 21.55). These areas may be more apparent than they originally were due to increased transparency over time of the upper paint layers. Other than these two pentimenti, the work appears to have been rather directly painted. The predominance of wet-in-wet paint application, including the signature, as well as an impression in the paint around the edges that appears to have been caused by framing when the paint was still soft (fig. 21.56), suggest that the work was relatively rapidly executed, with a few final elements added [glossary:wet-on-dry].

Painting tools

Brushes, including approximately 1.0 cm width, flat ferrule (based on width and shape of brushstrokes), smaller and possibly pointed brushes for finer details.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cadmium yellow, chrome yellow, vermilion, red lake, emerald green, viridian, cobalt blue, and ultramarine blue. UV fluorescence of some of the pink and red strokes suggests the presence of red lake throughout the composition.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface finish

Varnish layer/media

In 1967, a yellowed natural-resin varnish was removed from the painting and a three-layer synthetic varnish was applied (see Conservation History). The synthetic coating is even but slightly glossy in places depending on the texture of the underlying paint. It is noted in the 1966 pretreatment report that previous conservation treatment of the painting probably included thinning of the preexisting varnish layer and revarnishing. There are residues of natural-resin varnish in the recesses of the paint texture.

Conservation History

The 1966 pretreatment report mentions that previous conservation treatment of the painting probably included thinning of a preexisting varnish layer and revarnishing.

In 1967, discolored surface films were removed. The canvas was wax-resin lined and restretched on an ICA spring stretcher. The surface was coated with polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA, followed by a spray coating of methacrylate resin L-46 and a final spray coating of AYAA.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition. The canvas is wax-resin lined and stretched taut on an ICA spring stretcher. There are some tiny losses of paint and ground, cracking and abrasion around all of the original foldovers and tacking margins. The paint layer is in good condition, with only a few tiny paint losses near the edges. There is a general network of light cracks over the paint surface, which is more pronounced in areas of thickly applied, lead white–rich paint. There is an indentation in the soft paint along the left edge, as well as a ridge of pushed paint at the bottom edge, which appear to be the result of framing when the paint was still soft. There is retouching around all of the edges of the painting, especially along the right edge where the composition has been extended by approximately 1 cm over the strip of exposed ground along that edge. Residues of discolored natural-resin varnish are visible throughout the paint surface under magnification. There are also small, localized areas of wax residues from the lining adhesive and starch paste from the facing over the paint surface. The work has an even, synthetic varnish, which is slightly glossy in areas depending on the texture of the underlying paint.

Frame

The current frame (installed by 1975) is not original to the painting. It is a French, late-seventeenth-century, Louis XIV, ogee frame with corner and center cartouches with fleurs-de-lis centers and linked foliate scrollwork on a quadrillage bed, a sanded frieze, and an ogee with linked strapwork and flower-head motif at the sight edge. The frame is water gilded over red-brown bole on gesso. The original gilded surface is very compromised, probably as a result of an imposed décapé finish. The carved oak moldings are mitered and joined with angled dovetails. The molding, from perimeter to interior, is fillet; scotia; ogee face with corner and center cartouches with fleur-de-lis centers and linked foliate scrollwork on a quadrillage bed; fillet; sanded frieze; and ogee with linked strapwork and flower-head motif on a recut ground (fig. 21.57).

Kimberley Muir

Provenance

Acquired from [unknown] by Bongniat et Cie.

Acquired by Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, by Aug. 1, 1912.

Half-share sold by Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Aug. 1, 1912, for 3,500 francs.

Remaining half-share sold by Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Jan. 13, 1916.

Sent by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Feb. 1916.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Chester Johnson, Chicago, June 29, 1929.

Acquired by Mrs. John H. (Anne R.) Winterbotham, Chicago, by 1964.

Given by Mrs. John H. (Anne R.) Winterbotham, Chicago, in memory of her husband, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1964.

Exhibition History

Boston, Brooks Reed Gallery, Tableaux Durand-Ruel, Oct. 1916.

Cincinnati Art Museum, French Painters So-Called Impressionist School, Nov. 1926.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors: An Exhibition Sponsored by the Men’s Council of the Art Institute, Sept. 20–Oct. 27, 1963, no cat. no.

Tulsa, (Okla.), Philbrook Art Center, French and American Impressionism, Oct. 2–Nov. 26, 1967, cat. 7.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 58 (ill.). (fig. 21.58)

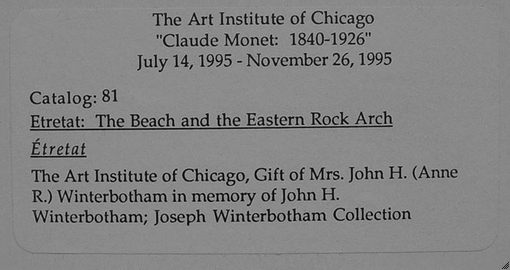

Art Institute of Chicago, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, July 22–Nov. 26, 1995, cat. 81 (ill.). (fig. 21.59)

Selected References

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors: An Exhibition Sponsored by the Men’s Council of the Art Institute, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, [1963]), p. 5.

Art Institute of Chicago, Annual Report, 1963–64 (Art Institute of Chicago, [1964]), pp. 3, 19.

Philbrook Art Center, French and American Impressionism, Sponsored by Tulsa Collectors Group, exh. cat. (Philbrook Art Center, 1967), p. 7, cat. 7.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Exhibitions,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 69, 4 (July–Aug. 1975), p. 7.

Grace Seiberling, “The Evolution of an Impressionist,” in Paintings by Monet, ed. Susan Wise, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 31.

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 112, cat. 58 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 2, Peintures, 1882–1886 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1979), pp. 168; 169, cat. 1012 (ill.).

Charles F. Stuckey, ed., Monet: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1985), p. 121 (ill.).

Lyn DelliQuadri, “A Living Tradition: The Winterbothams and Their Legacy,” in Art Institute of Chicago, The Joseph Winterbotham Collection: A Living Tradition (Art Institute of Chicago, 1986), p. 13.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Joseph Winterbotham Collection: A Living Tradition (Art Institute of Chicago, 1986), pp. 56 (ill.), 60.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Selected References and Index,” in “The Joseph Winterbotham Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 2 (1994), p. 192.

Lyn DelliQuadri, “A Living Tradition: The Winterbothams and Their Legacy,” in “The Joseph Winterbotham Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 2 (1994), p. 109.

Margherita Andreotti, “The Joseph Winterbotham Collection,” in “The Joseph Winterbotham Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 2 (1994), pp. 118–19 (ill.).

Robert L. Herbert, Monet on the Normandy Coast: Tourism and Painting, 1867–1886 (Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 101; 102–03, fig. 109; 104–05, fig. 114 (detail).

Sophia Shaw Pettus, “Checklist of the Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1921–1994,” in “The Joseph Winterbotham Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 2 (1994), p. 188 (ill.).

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), p. 102, cat. 81 (ill.).

Peter Neill, in collaboration with James A. Randall and Suzanne Demisch, On a Painted Ocean: Art of the Seven Seas, ed. Gareth L. Steen (New York University Press, 1995), pp. 2, 3 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 3, Nos. 969–1595 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), p. 381, cat. 1012 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

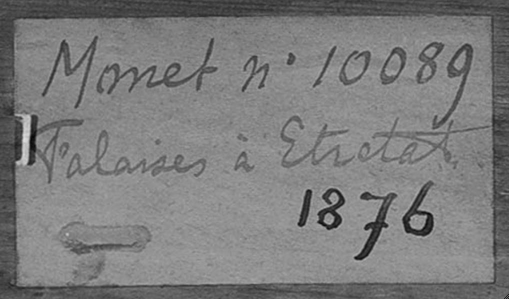

Inventory number

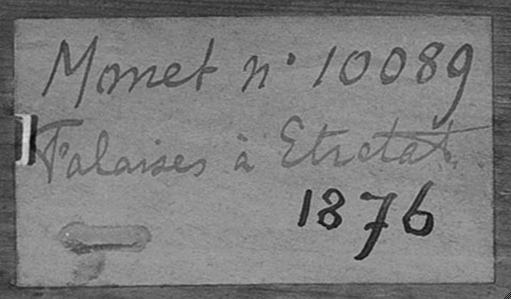

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 10089

Livre de stock Paris 1901

Inventory number

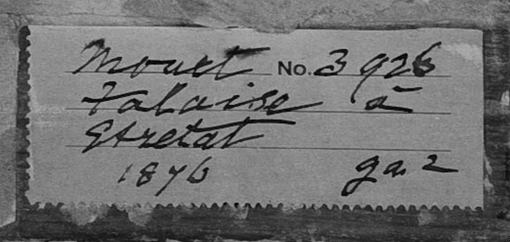

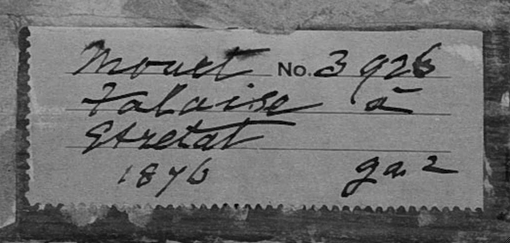

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 3926

Livre de stock New York 1904–24

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel Paris 7460

Other Documents

Label (fig. 21.60)

Label (fig. 21.61)

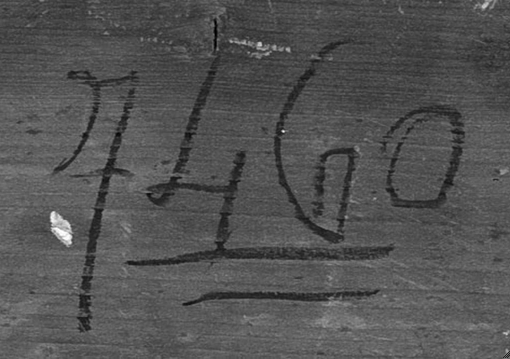

Inscription (fig. 21.62)

Inscription (fig. 21.63)

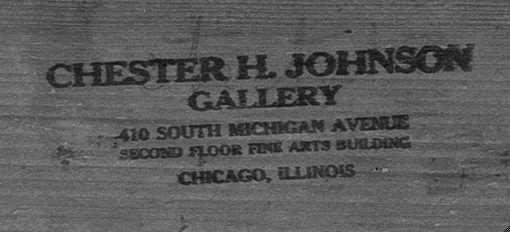

Chester Johnson Documentation

Stamp (fig. 21.64)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 64.204 (fig. 21.65)

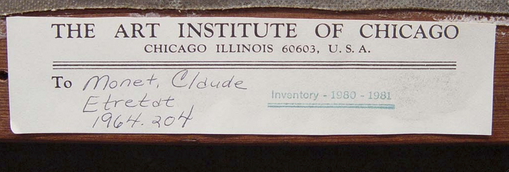

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script and green-ink inventory stamp

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / To Monet, Claude / Etretat / 1964.204

Stamp: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 21.66)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: canvas; transcription in conservation file

Method: not documented; text within palette-shaped frame

Content: II. [sic] VIEILLE E TROIS GROS [sic] [. . .] / 35 RUE DE LAVAL 55 [sic] / PARIS / COULEURS FINES / TOILES PANNEAU [sic] (fig. 21.67)

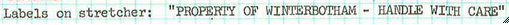

Label

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); transcription in conservation file

Method: not documented

Content: PROPERTY OF WINTERBOTHAM – HANDLE WITH CARE (fig. 21.68)

Label

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); transcription in conservation file

Method: not documented; on pink paper (4 × 6 cm) [according to transcription in conservation file]Content: No. 1976 . . . Etretat (fig. 21.69)

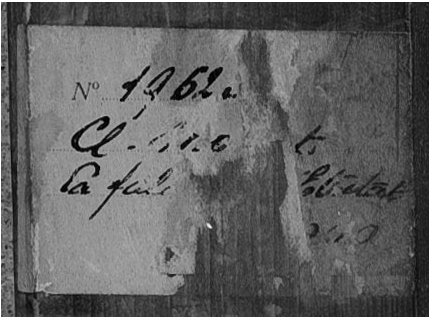

Label

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on printed label

Content: No 1962 . . . / Cl. Mo[ne]t / La fal . . . Etretat / . . . (fig. 21.70)

Label

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on white paper (3.5 × 6.5 cm)

Content: Monet n° 10089 / Falaises à Etretat / 1876(fig. 21.71)

Label

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on pink paper (3 × 7 cm)

Content: Monet No. 3926 / Falaise à / Etretat / 1876 / ga2 (fig. 21.72)

Stamp

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded), 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: ink stamp

Content: CHESTER H. JOHNSON / GALLERY / 410 SOUTH MICHIGAN AVENUE / SECOND FLOOR FINE ARTS BUILDING / CHICAGO, ILLINOIS (fig. 21.73)

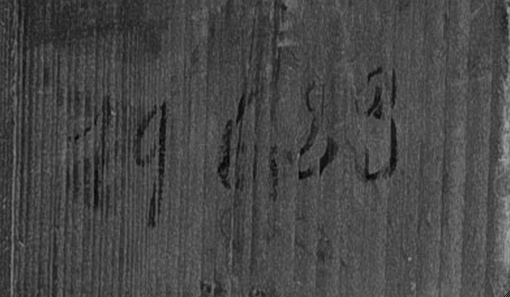

Stamp

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: ink stamp

Content: DOUANES / V-1 / + (fig. 21.74)

Label

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: printed label

Content: M . . . T . . . NATION (fig. 21.75)

Number

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

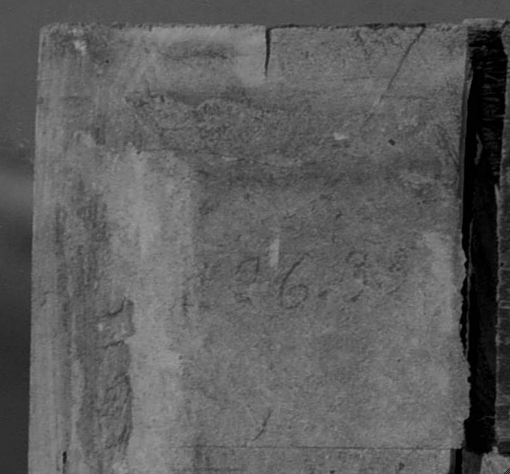

Content: . . . 6.33 (fig. 21.76)

Number

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

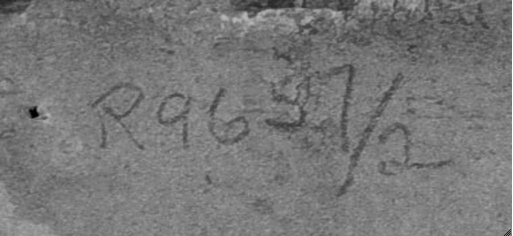

Method: handwritten script

Content: R9657/2 (fig. 21.77)

Number

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 19[6,83?] (fig. 21.78)

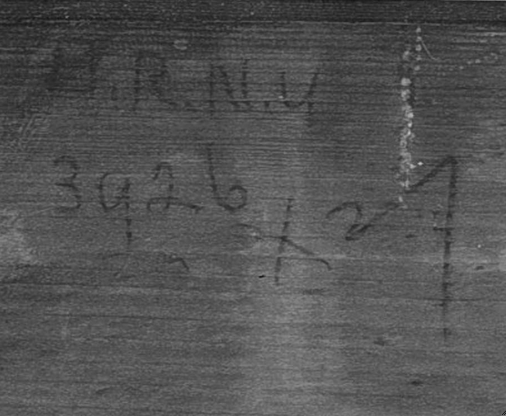

Number

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: D.R.N.Y / 3926/27 (fig. 21.79)

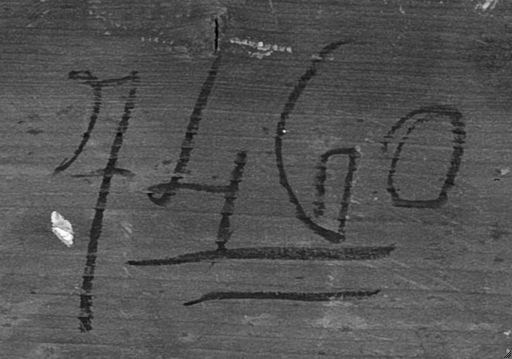

Number

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 7460 (fig. 21.80)

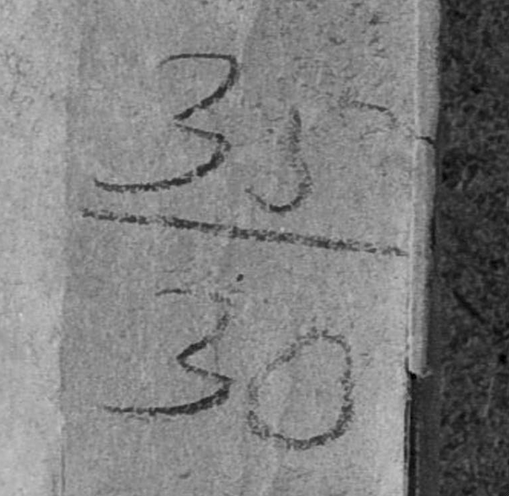

Number

Location: pre-1967-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1967 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 35 / 30 (fig. 21.81)

Post-1980

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / “Claude Monet: 1840–1926” / July 14, 1995–November 26, 1995 / Catalog: 81 / Etretat: The Beach and the Eastern Rock Arch / Étretat / The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. John H. (Anne / R.) Winterbotham in memory of John H. / Winterbotham; Joseph Winterbotham Collection (fig. 21.82)

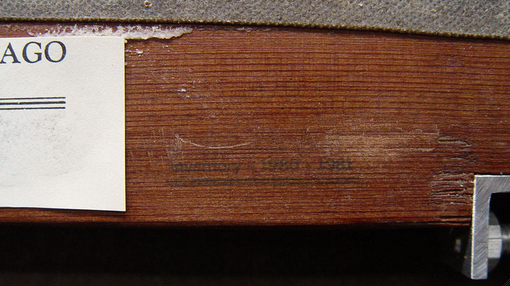

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: green-ink stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 21.83)

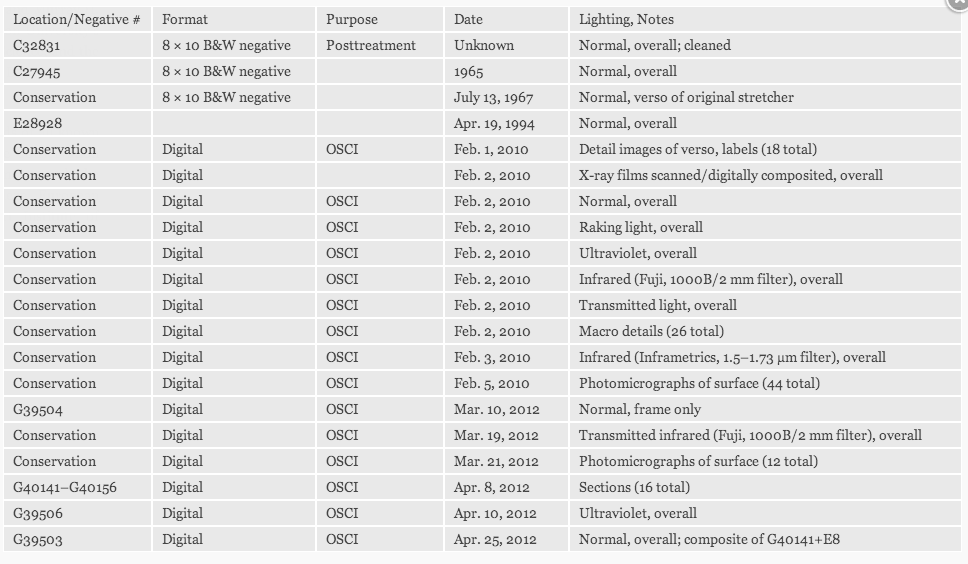

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 21.84).