James McNeill Whistler and Theodore Roussel: Linked Visions

In 1885 James McNeill Whistler sought an introduction to Theodore Roussel after seeing his work displayed at Dowdeswell and Dowdeswell’s London gallery. At the time, Whistler was already an established artist—even notorious, as a result of the libel suit he brought against the eminent art critic John Ruskin—and Roussel was just beginning to exhibit in London. Although only thirteen years apart in age, the two men developed a mentor-follower relationship by 1887, and Roussel remained a deferential disciple until the last years of Whistler’s life. During the period of their closest association in the late 1880s and 1890s, their interaction had a significant effect on their careers, as did their participation in a larger network of artists, models, writers, and other creative individuals. Within that web of connections, they sometimes led the way and at other times assimilated or reflected fashions and behaviors of the period.

Linked Biographies

Whistler and Roussel were both born into military families. Whistler’s father was the son and brother of army men and a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, as was a brother of Whistler’s mother. Whistler spent most of his boyhood in Russia and England; he returned to the United States when, at age seventeen, he received a commission to West Point himself. He read widely and excelled in drawing but was dismissed three years later after failing chemistry and accumulating an excessive number of demerits for poor conduct. In 1855 he traveled to Paris to study art. He spent more than three years there, first in classes at the École Imperiale et Spéciale de Dessin and then as a pupil in the studio of the Swiss painter Charles Gleyre before moving to London and establishing his home and work base there. From 1859 until his death in 1903, apart from breaks for travel to the Continent (and once to Chile) and more prolonged stays in Venice and Paris, Whistler spent most of his time in London. He never returned to the United States.

Roussel was born in Brittany in 1847 to a family whose men traditionally had careers in the army or navy. After completing his studies at the Collège Henri Quatre in Paris, which included art instruction under the marine painter Théodore Gudin, he was admitted to the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, the French national military academy, but a serious illness prevented him from enrolling. Roussel traveled to Rome to recuperate and was drafted into the Garde Nationale Mobile when he returned to France in 1869. He served during the Franco-Prussian War and remained in the guard until about 1872. Some five years after his discharge, he relocated to London, marrying the Englishwoman Frances Amelia Smithson Bull in 1880. He remained there until 1914, when he and his second wife, Ethel Melville, moved to St. Leonards-on-Sea, on the English Channel near Hastings. Roussel continued to live and work there until his death in 1926.

Linked Subjects

In 1862, after short stays in other parts of the city, Whistler settled in Chelsea, a neighborhood along the north bank of the River Thames in southwest London. He moved within the district a number of times, renting several properties near the river and building his own home and studio, the White House, between 1877 and 1879. In 1885, the year he met Roussel, Whistler leased a studio on Fulham Road, near the western edge of Chelsea, and a house in The Vale, farther to the east. Roussel’s first recorded London residences were located on Edith Grove, Burnaby Street, and Kings Road, all in Chelsea and all near Whistler’s Fulham Road space. While their formative experiences in Paris and shared fluency in French were important connectors—evidenced by their practice of corresponding in that language until the latter years of Whistler’s life—the two artists’ common interest in portraying local streets and nearby riverscapes brought them together and strengthened their relationship.

Whistler began focusing on the Thames in the late 1850s, when he recorded the bustling docks and crowded warehouses of London’s East End, first in etchings and then in oil. A Series of Sixteen Etchings of Scenes of the Thames, known as the Thames Set, dates from 1859, while his first oil painting of the river, Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge (Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass.), was commissioned in 1859 and likely completed in 1863. After his move to Chelsea in 1862, Whistler recorded more tranquil—but still often commercial—views along the riverside. Roussel, too, painted and drew such vistas when he became a resident of the neighborhood; influenced by Whistler, he also began to etch local scenes.

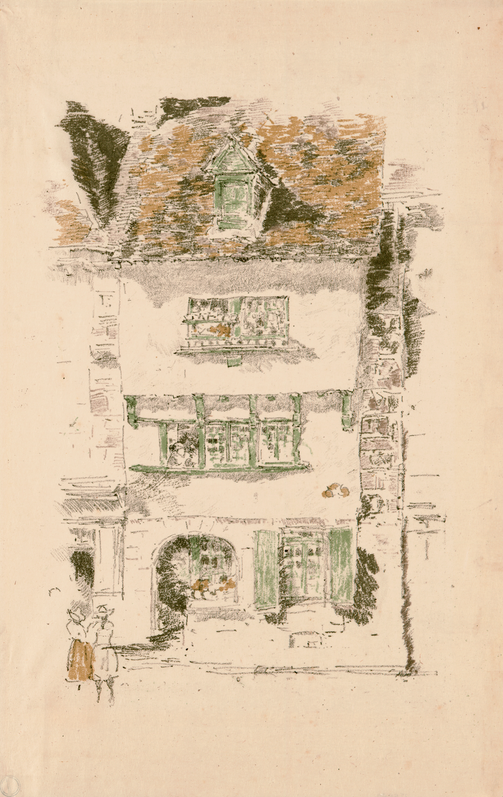

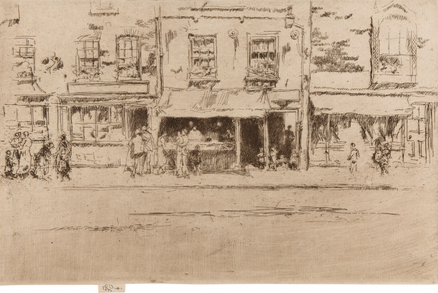

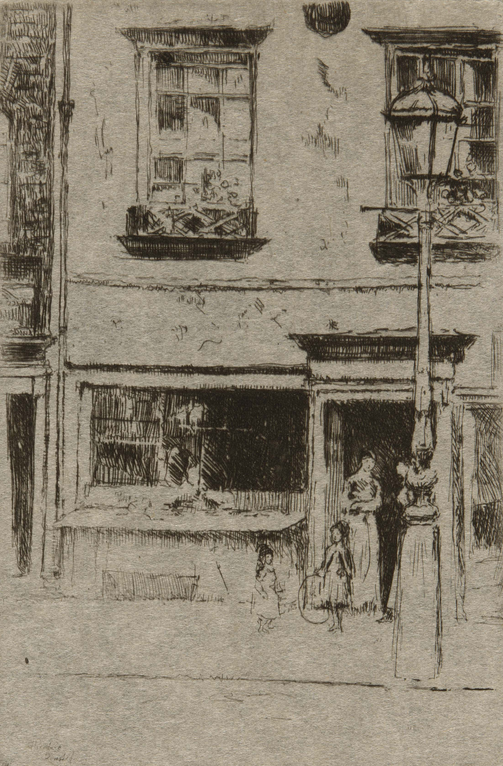

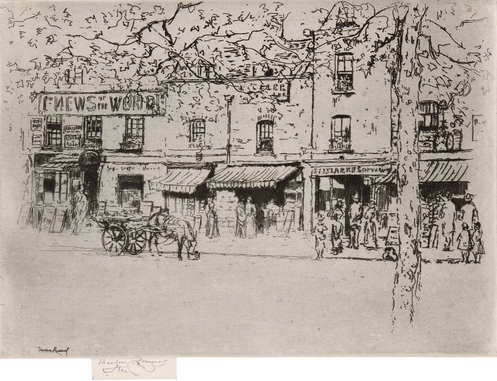

While both artists depicted Chelsea views of the Thames and the Battersea factories on the opposite bank, they also portrayed the district’s street life—adults and children strolling, lounging, selling, shopping, and playing against backdrops of storefronts, houses both humble and grand, and the railings of Chelsea Embankment. Some subjects, such as the store shown in Whistler’s diminutive painting known as Carlyle’s Sweetstuff Shop (fig. 1), conjure important local associations—in this instance, the haunts of the eminent philosopher, author, and neighborhood resident Thomas Carlyle. Other imagery is more mundane, like the fish shop on Cheyne Walk owned by Mrs. Elizabeth Maunder. It appears in Whistler’s Street in Old Chelsea (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) from 1880/85, a small oil on panel that shows the shop among a row of seven others. He also included the establishment in two etchings, Fish Shop, Chelsea (see fig. 2) from 1886, which is similar in format to the small oil, and Little Maunder’s from 1887, a freely drawn sketch of the store on its own. Whistler’s transfer lithograph Maunder’s Fish Shop, Chelsea (fig. 3) from 1890 corresponds closely to Roussel’s etching of the subject, The Little Fish Shop, Chelsea Embankment (fig. 4) of 1888/89; both works share a focused point of view that describes just two stories of the building. In contrast, Roussel’s The Street, Chelsea Embankment (fig. 5) is more expansive, showing the stretch of commercial premises then located on Cheyne Walk to the west of Mrs. Maunder’s shop; this treatment has more in common with Whistler’s Fish Shop, Chelsea.

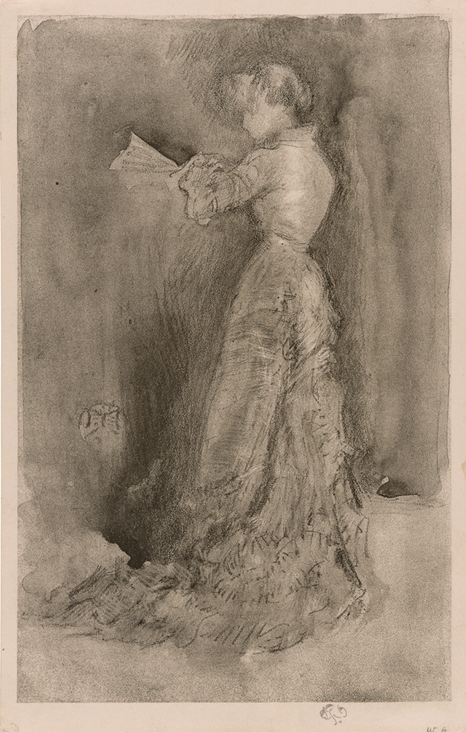

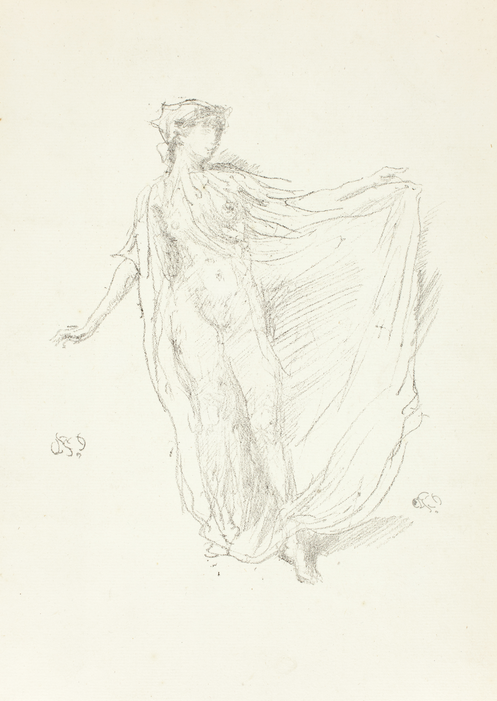

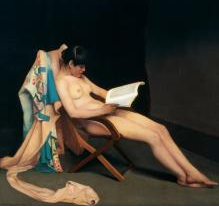

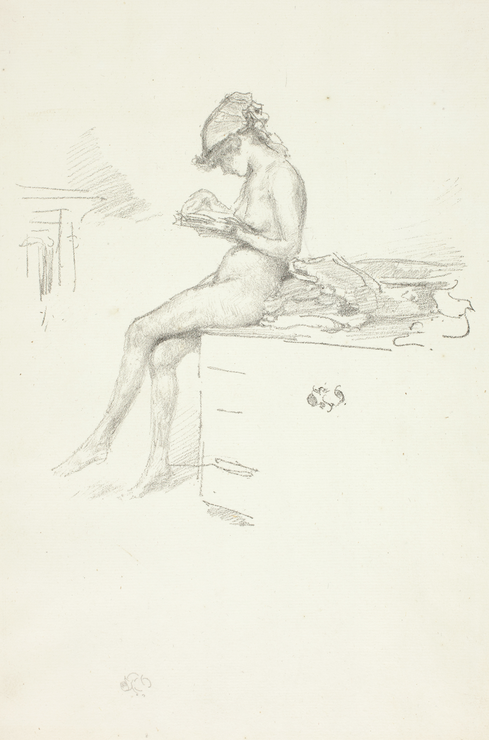

The two artists also focused on portraying both nude and draped figures. Whistler first depicted thinly clothed models in paintings and drawings from the 1860s, treating them as examples of ideal beauty. He took up the subject again in lithography between 1889 and 1895, creating works such as The Dancing Girl (fig. 6). Roussel’s best-known painting, The Reading Girl (fig. 7) of 1886/87, shows a seated studio model reading in the nude. Her stylized hairstyle, reminiscent of a geisha’s wig, suggests that she has just been posing in the embroidered Asian robe draped over her chair. The woman’s chapped, reddened hands and feet further establish her as a less than idealized figure, and the large scale of the work boldly asserts that an ordinary model, taking a break from posing, is a subject worthy of an exhibition picture. Whistler, who referred to The Reading Girl as “an extraordinary picture,” created a lithographic version of the subject in The Little Nude Model, Reading (fig. 8) of 1888/89, adapting it to a more spontaneous medium and intimate scale.

The two artists’ nude studies from the early 1890s, a period in which they likely worked side by side at times, demonstrate further parallels. Whistler’s Draped Figure, Reclining (fig. 9) of 1892 and Roussel’s Study from the Nude, Woman Asleep (fig. 10) of 1890–94 depict female figures posed in a similar way on a roll-arm studio couch.While one model is draped and the other unclothed, their closed eyes prevent contact with the viewer, positioning them as examples of idealized form rather than flesh-and-blood women. Whistler’s colorful and highly patterned pastel The Arabian (fig. 11) dates to the same period. It closely parallels Roussel’s Study from the Nude, Woman Asleep, depicting the model on what is likely the same sofa.

Linked Technical Experiments

Whistler devoted considerable time to transfer lithography, a medium that he favored from 1887 onward. In contrast to lithographs made directly on a lithographic stone, an image for transfer is drawn in lithographic crayon on paper that is specially coated to permit transfer of the drawing onto a stone for professional printing. The process allows unique drawings to be transformed into multiples outside the workshop and without need for technicians, chemicals, and cumbersome, heavy materials. Whistler found the method well matched to his skill as a draftsman and his artistic goals—ideal for spontaneous depictions that captured the essential qualities of views or sitters.

Roussel turned to transfer lithography in the early 1890s at Whistler’s encouragement. Both on his own and side by side with his mentor, Roussel made eleven transfer lithographs in a burst of activity that took place between 1890 and 1894. Several were exhibited in London in 1894 and then again in 1898 and 1899. While most of Whistler’s transfer drawings translated well into lithography, Roussel’s were less suited to the process. In many he attempted fairly dense shading, which seems to have created issues in printing (see fig. 12). A number of the artist’s completed lithographs show fine, scratched-out lines that help to define form in shaded areas. These delicate white marks are presumably adjustments that were made on the stones after the drawings had been transferred; the first proofs pulled must have revealed flat, dark areas that required further modeling.

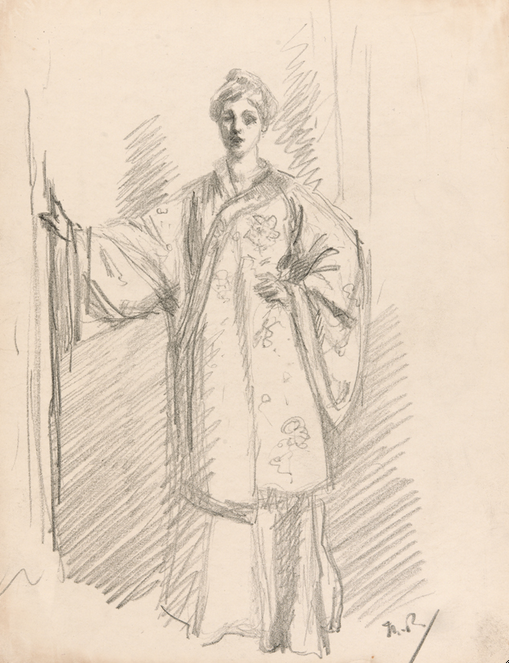

There is compelling evidence of collaboration as the two artists explored this medium together, apparently employing the same studio furniture and, as will be discussed below, the same model. For printing, Roussel turned to Thomas Way and his son Thomas Robert Way, who had a close, ongoing relationship with Whistler that extended from 1878 to 1896; they transferred Roussel’s drawings and printed the resulting lithographs in small numbers. Moreover, Roussel used the same type of fine-grained transfer paper that Whistler used in London, which both received from the Ways. One surviving untransferred drawing by Whistler, Reclining Draped Figure (fig. 13), and two by Roussel, Standing Figure in a Chinese Gown (fig. 14) and Portrait Head (H A.IV), date from this period. The same paper was used, and scientific analysis has determined that the sheets for both Reclining Draped Figure and Standing Figure in a Chinese Gown were coated with an identical lead white ground.

Color printmaking was another area of common interest during the 1890s. Whistler focused on color lithography from 1890 to 1893, while Roussel spent almost a decade on a set of color etchings that he exhibited in 1899 and continued to work on large-scale color intaglio prints until 1914. Whistler performed his color printmaking experiments in transfer lithography, resulting in just seven different color images. The impressions of those lithographs display a nuanced selection of ink color and paper, reflecting the artist’s quest for the type of subtle effects he achieved with pastel. In drawings such as Corte del Paradiso (fig. 15) of 1880, for instance, he used black pastel on brown paper to structure the composition and create a middle tone, enlivening the arrangement with carefully placed strokes of color. For his color transfer lithographs, he took a similar approach with printer’s ink: one proof of Yellow House, Lannion (fig. 16) of 1893 shows an intermediate state with black, green, yellow, gray, and medium-gray colors. In an impression of the final state of the same work (fig. 17), the effect is lighter due to reduction of dark shading and brighter thanks to a palette of black, greenish gray, brown, green, yellow, and gray inks. For assistance with such projects, the artist, who moved to Paris in 1892, depended upon the technical skills of the local printer Henry Belfond, who provided thin, transparent transfer paper and facilitated the use of multiple stones for printing different colors. Whistler’s work with color transfer lithographs paralleled developments in color printing in France, but given the relatively small number of his existing impressions and the great range of variation among them, it represents a period of exploration rather than a long-term commitment. The ultimate significance of his efforts is the inspiration they provided other artists, including Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, whose refined lithographs reflect Whistler’s sensitive approach to line and color.

In contrast to Whistler’s collaboration with Belfond and other professional printers, Roussel carried out his color experiments aided only by studio assistants. Unencumbered by the need for stones, a large press, or help transferring images, he was able to refine intaglio techniques, mix inks, and proof copper etching plates in his own studio. Nevertheless, the gestation of his set of nine color intaglio prints, which began in 1890, was described in a June 1897 newspaper article as a lengthy process:

Mr. Theodore Roussel, of whom the art world has heard very little of late, has for some time past been devoting himself to the perfecting of both means and medium for the production of etchings in colour. If all goes well it is probable the public will have an opportunity of seeing this unique work this season.

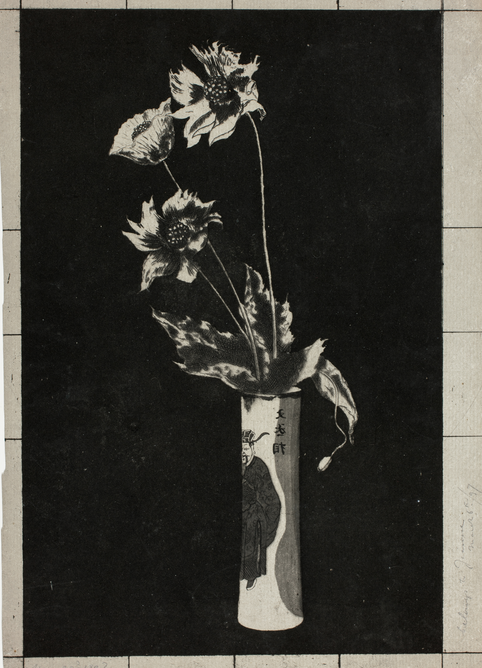

As it turned out, the etchings were not exhibited until July 1899. For these Roussel employed a number of techniques in varying combinations and mastered the precise registration required for impressions made from multiple plates or several inkings of the same plate. All the color prints incorporate line work in etching, drypoint, or both in conjunction with one or more tonal techniques for broad, dark areas and shading. Roussel used aquatint, lavis (open-bite etching), and soft-ground etching for such passages, and a monochrome proof for La chine (Color Version) (fig. 18) clearly shows the rich range of tones he worked so diligently to achieve. The artist also focused on mixing pigments and developing metallic printing inks that would not discolor after contact with copper etching plates.

The large number of extant trial proofs of the color intaglios in relation to the small quantity of finished impressions attests to the deliberate, painstaking approach Roussel took in refining techniques and color combinations. For his tranquil view of shore, sky, and water entitled The Sea at Bognor (fig. 19) of 1895, he tested different ink formulas for the bands of color, creating a series of proofs in which he inked only those portions of the plate (fig. 20). In 1920 these explorations led Roussel to develop a novel technique for producing more painterly multiples that were pulled from fabric plates to which a thick, opaque, water-based medium had been applied. He made such prints until 1925, the year before he died, and The Little Cloud (fig. 21) from 1923 is an example of this final phase of color experimentation.

Roussel was a pioneer in color printmaking in Britain, where he was among the first artists to focus on soft-ground etching in the late 1800s. While there were no clear successors to his methods other than his son Raphael and pupil Robertine Heriot, he did foster new developments in color printmaking through the Society of Graver-Printers in Colour, which was founded in his studio in 1909. The group, now known as the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers, continues to present annual exhibitions of members’ work.

Linked Presentation

Whistler had firm opinions about the appropriate scale and presentation of prints. He favored small portable copper etching plates that were ideal for sketching subjects on the spot either out of doors or in indoor locations away from the studio. Moreover, the artist believed that plate sizes should be appropriate to the subject matter depicted, rejecting the larger plates commonly used for reproductive engravings. He also trimmed etchings to their plate marks, leaving very small rectangles of paper below the bottom edge for his signatures. In his opinion, this compelled viewers to focus on the images rather than the quality or condition of the blank margins around them. Aligning himself with this approach, in his early etchings Roussel adopted Whistler’s practice of employing small plates and signed his works in the same way.

Whistler also considered frames to be either extensions of or essential complements to the works within them. Beginning in the 1860s, he created innovative designs that reveal his sensitivity to the entire ensemble. He was influenced by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites, whose rejection of the machine-made frames of the day was derived from the renewed value they placed on craftsmanship and unique housings for particular canvases and panels. Whistler’s designs for frames of paintings included flat, gilded surrounds with incised decoration; gold reeded moldings with painted embellishment; and simpler gold reeded examples that came to be known as “Whistler frames.” For exhibitions of etchings and lithographs, he designed narrow white frames with linear details.

Following his lead, Roussel created etched frames to surround some of his monochrome and most of his color prints. He expanded on his mentor’s ideas by creating etched patterns that were designed to be printed and then cut apart and pasted onto wooden frame moldings. Roussel’s black-and-white etched frame decorations were related to Whistler’s frames for etchings and lithographs, which had narrow moldings that were painted white or coated with white gesso and featured minimal linear decoration. His four frame designs for monochrome etchings were printed on white paper in black ink; the earlier two—including the Lily Pattern Frame of 1888/89 (fig. 22), with its narrow bands of subtly shaded flowers—incorporate delicate, Asian-inspired floral motifs, while the later two are more elaborate schemes that include figures from Classical mythology. These designs were trimmed and glued to slim moldings with rounded corners—the earlier ones with a rounded profile, the later ones flat—and the surfaces were then varnished, producing a patina similar to that of ivory.

Roussel’s ideas for mounting and framing his nine color prints were more closely aligned with Whistler’s frames for paintings, with decorative schemes that were specifically designed to enhance the works of art they contained. Roussel coordinated the decoration even further by creating two different etched mounts—the Scarab, Grecian Key, and Fly Pattern Mount (fig. 23) and the Shell Pattern Mount (H 168)—which were printed in a variety of hues to complement both his color frame designs and the nine etchings housed within them. As he explained, “I have adopted this arrangement in order that the central proof should, at least according to my own ideas, form with its mount and frame, always specially printed for it, a complete harmony of colour.” The designs, which incorporate Egyptian, Classical, and Renaissance motifs, are considerably more eclectic than Whistler’s, and, as evident in the assemblages for Summer (Color Version) (fig. 24 [H 143, 168, 162) and Last Poppies (fig. 25 [H 150, 167, 164), the highly patterned ensembles display ornamental qualities more commonly associated with decorative objects than works of fine art. The prints are virtually subjugated to the overall effect of layered color and pattern, but the combinations of image, mount, and frame are ultimately intriguing and visually arresting because of their carefully balanced relationships.

Linked Models

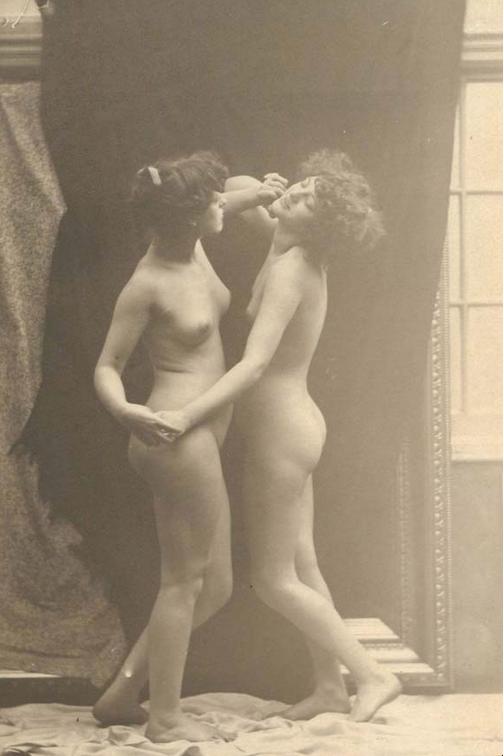

Whistler and Roussel also shared models for some of their prints, drawings, and paintings. During the period of their closest affiliation, the artists engaged Harriet (Hetty) Pettigrew—depicted in The Reading Girl (fig. 7)—as well as her sisters Lilian (Lily) and Rose. Three of the nine children of a Portsmouth cork cutter and seamstress, the girls came to London with their widowed mother to look for work as models. They approached the painter John Everett Millais, who was taken by their auburn hair and striking eyes, and began posing for him around 1884. They were soon sitting for other artists as well. Rose was most in demand, posing for Walter Sickert, Augustus John, Philip Wilson Steer, and Beatrice Whistler. All three sisters modeled for John William Godward, who specialized in Greco-Roman figure subjects, and for the Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne, who photographed them both clothed and nude (fig. 26, fig. 27). Hetty also posed for the sculptors Hamo Thornycroft and John Tweed, work that apparently coincided with her transition from sculptor’s model to sculptor.

Whistler employed all three sisters for transfer lithographs in the early 1890s, although it is difficult to distinguish one sibling from another. He depicted Hetty in one oil painting as well as in prints and pastels, Lily in at least one oil portrait, and Rose more often—in etchings, lithographs, pastels, and watercolors. In various works on paper, one or more of the sisters posed for Whistler along with a child who has been identified as a niece. Roussel, meanwhile, hired Hetty as his principal paid model; while her connection with Whistler appears to have been purely professional, she had a more complex one with Roussel. She also worked as his studio assistant, and an intimate relationship between the two led to the birth of a child, Iris, around 1900.

Whistler also had intimate relationships with several of his models, resulting in some studies of those women that are distinctly informal in character. This is true in the case of Maud Franklin, who began working for Whistler in the early 1870s and, within a few years, had settled into a domestic arrangement with him. In addition to formally posed works like The Toilet (fig. 28), a lithotint from 1878, Franklin appears in many drawings, etchings, and lithographs that were sketched in the sitting room or boudoir rather than the studio. The lithograph Study (fig. 29), from 1878, is one such work, while Maud on a Stairway (fig. 30), a watercolor from 1884/85, has elements of both the professional and the personal; it shows Franklin in a posed position, but the informality of her less-than-perfect posture and direct gaze convey the intimacy she and Whistler shared.

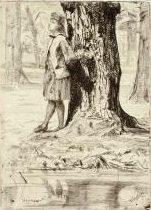

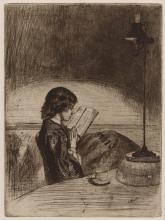

As was common with other artists of the period on both sides of the Atlantic—from William Merritt Chase in the United States to Claude Monet in France—Whistler and Roussel used nonpaid sitters as well. These included relatives and members of their households, who posed in prescribed positions as well as in informal settings. Whistler sketched, painted, etched, and made lithographs of his family throughout his career. During the 1850s, for instance, he depicted his London relations, focusing particularly on his half-sister, Deborah, who had married the surgeon and etcher Francis Seymour Haden, and three of their children, Annie, Seymour, and Arthur. While most etchings of his niece and nephews, including Little Arthur (fig. 31) and Seymour (fig. 32), were evidently posed, Reading by Lamplight (fig. 33) shows Deborah in a casual setting—nearsightedly reading, feet resting on a stool, with a lamp elevated on an overturned bowl and a cup of tea by her side. Whistler’s use of relatives as subject matter resulted in one of his best-known works, the iconic Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother (1871; Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

In 1888, after Whistler broke off his relationship with Franklin and married Beatrice Godwin, his portraiture expanded to include his wife, his mother-in-law, and two sisters-in-law in a range of media—quick sketches, oil paintings, etchings, and lithographs. The Duet (fig. 34), a transfer lithograph from 1894, shows Beatrice and her sister Ethel Philip Whibley at the piano in the comfortable, lamp-lit salon of the Whistlers’ house on the rue du Bac in Paris. It is one of a number of lithographs that depict the sisters in home and garden settings. Whibley also posed formally, on her own, for transfer lithographs and modeled for several of Whistler’s large oil paintings. These include The Winged Hat (fig. 35) and Gants de suède (fig. 36) from 1890 and A Lady Seated (fig. 37) from 1893.

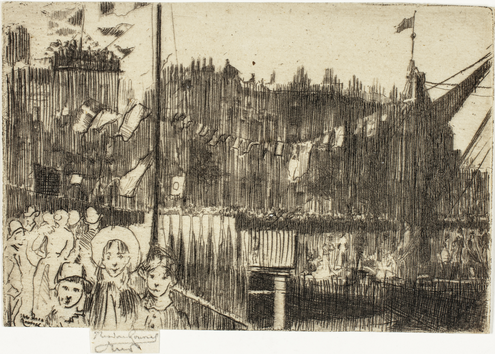

Like Whistler, Roussel used family members as models in a variety of media. In the early 1890s, he exhibited a highly finished pastel of his daughter, Jeanne, entitled Portrait of a Little Girl (Miss Roussel, Aged 7) (c. 1887; private collection) and a large oil painting of his first wife, Frances, Portrait of a Lady (Mrs. Theodore Roussel) (1890/94; private collection). He also depicted his older son in the pastel Raphael Roussel, Aged 6 (c. 1889; private collection) and made portraits in both drypoint and oil of his younger son, Little Paul (February 6th, 1889) (H 29) and Portrait of a Child (Little Paul) (c. 1890; private collection). Chelsea Regatta (fig. 38), an etching from 1888–89, shows the banners, raised oars, and crowd of spectators associated with a race along Chelsea Embankment. It also spotlights three small figures in the foreground whose relative sizes identify them as the Roussel children. Like Whistler’s, this focus on family models continued to the end of Roussel’s career and included prints, drawings, and paintings of a daughter-in-law and a granddaughter as well as his second wife and her niece. Close at hand and apparently obliging, family models were central to Roussel's work.

Social Links

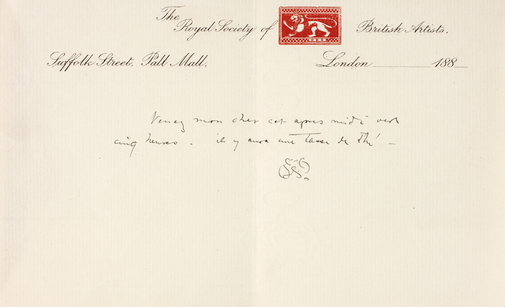

Professional societies, clubs, and social gathering places—realms of the art world outside studio and home—provided Whistler and Roussel with the stimulation and contacts that were necessary to develop and promote their work. Exhibiting societies afforded status, colleagues, and exchange of ideas as well as venues for marketing their art. Although Whistler’s ego and mercurial nature made him temperamentally unsuited to participating in any organization for the long term, he had a brief, high-profile association with the Society of British Artists. Recognizing that election to the Royal Academy of Arts—the most prestigious artists’ organization in England since its establishment in 1768—was unlikely, but desiring the imprimatur of affiliation with a professional group, he sought and gained membership to the Society of British Artists in 1884 and the following year began participating in its exhibitions. Soon appointed to the executive committee, he worked to raise the group’s visibility and address its financial problems. He also used the position to promote his friends and followers—Roussel among them—for membership and their work for exhibition. In 1886 Whistler was elected president, and, among his other efforts to advance the status of the organization, he successfully petitioned Queen Victoria to recognize the organization as the Royal Society of British Artists. He quickly designed a new logo in 1887, replacing the old circular emblem with a more striking rectangular one featuring a crowned lion passant (fig. 39). More significant initiatives included redecorating the galleries, limiting the number of pictures shown to raise exhibition quality, and promoting the membership of his cohorts from Europe, the United States, and Australia; these, however, were less popular with older members, and Whistler was ousted from the presidency in 1888. He resigned his membership in response, and Roussel and other loyal followers followed suit in solidarity, inspiring Whistler’s well-known quip about the society: “The ‘Artists’ have come out, and the ‘British’ remain.”

Roussel’s association with the New English Art Club provides a better example of the advantages of professional societies. That group was founded in 1886 by younger artists who had studied in France and shared an interest in contemporary French art—with an initial focus on realism and sound technique—and a conviction that the Royal Academy had not acknowledged the importance of new styles of painting. Roussel was not among the original members but was invited to show at the club’s second exhibition in 1887, where The Reading Girl (fig. 7) was on view along with his Portrait of Mortimer Menpes, Esq., “La Sortie du Club” (c. 1887; private collection), whose scale and style have affinities with French Salon paintings. The artist showed other art works with the club between 1889 and 1892, but The Reading Girl created the greatest stir; in an exhibition of just over one hundred works, the painting received considerable press. A review in the Spectator gave a scathing, attention-grabbing assessment:

There is one picture here of which we feel inclined to speak in terms of severe depreciation, if only because of its wantonness in taking a beautiful subject, and making it all at once odious and ugly. And this is M. Theodore Roussel[‘s] life-size work of an entirely nude model sitting reading the newspaper in a small folding-chair. Our imagination fails to conceive any adequate reason for a picture of this sort. It is realism of the worst kind, the artist’s eye seeing only the vulgar outside of his model, and reproducing that callously and brutally. No human being, we should imagine, could take any pleasure in such a picture as this; it is a degradation of Art.

The New English Art Club functioned on democratic principles, allowing members to control exhibition policy. This was quite different from the top-down decision making of both the Royal Society of British Artists under Whistler’s presidency and the jury system of the Royal Academy. Its exhibitions were smaller and more carefully curated in comparison, affording visibility to those who participated. Furthermore, interaction with a more youthful group of artists—and exposure to their ideas and enthusiasms—allowed for creative development separate from the influence of Whistler. Some of the club’s artists, including Roussel and Walter Sickert, moved toward Impressionism, painting with a brighter palette and more prominent strokes of color.

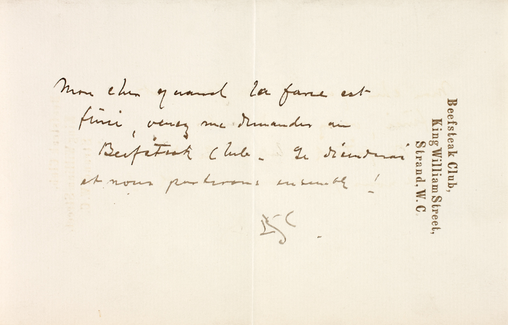

In contrast to the New English Art Club, which functioned as an exhibiting society, the gentlemen’s clubs in London offered congenial spaces to meet socially and make other connections. Many such establishments welcomed artists as members, and both Whistler and Roussel took part in the city’s fraternal life. By far the more outgoing of the two, Whistler held memberships in the Arts, Beefsteak, Hogarth, Savage, and St. Stephen’s Clubs and the Arundel Society as well as the more bohemian Chelsea Arts Club. Roussel was a member of the Savage and Chelsea Arts Clubs.

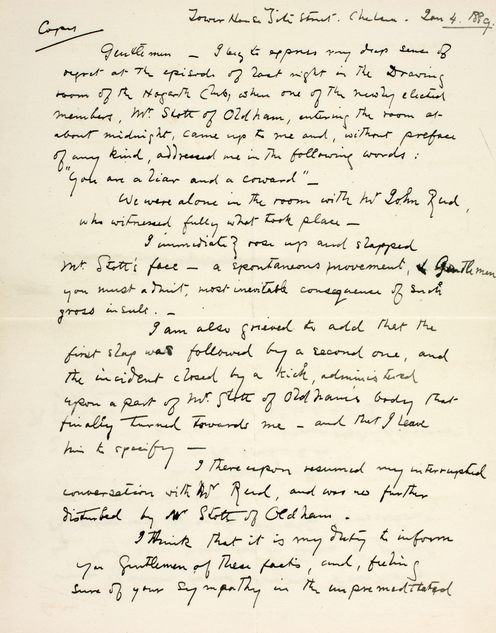

Whistler biographer Elizabeth Robins Pennell and her husband, Joseph Pennell—her coauthor as well as an etcher, lithographer, illustrator, and devoted follower of Whistler—recount of their subject, “If no one was coming to him, if no one had invited him, he dined at a club.” Whistler’s letters underscore his frequent visits to those meeting places. In a note to Roussel written on Beefsteak Club letterhead, he asks the younger artist to meet him there “quand la farce est fini” (“when the farce is over”), referring to the move to oust him from the presidency of the Royal Society of British Artists (fig. 40). In this case, the Beefsteak served as both a refuge from art world politics and a rendezvous. Another missive—a copy of a letter to the committee of the Hogarth Club that Whistler replicated for and sent to Roussel—relates to a confrontation that took place there. Whistler begins with a perfunctory expression of regret and continues with a justification for his behavior during a spat with a fellow member, the painter William Stott of Oldham; Stott insulted Whistler, who then slapped and kicked him (fig. 41). Although Whistler avidly collected club memberships, his interaction with fellow members could as easily be quarrelsome as congenial.

Both Whistler and Roussel were founding members of the Chelsea Arts Club, which was conceived in 1890 as an association of “professional Architects, Engravers, Painters, and Sculptors” and opened on the King’s Road in 1891. “Rule 3” of the group’s constitution stated that “the object of the Club shall be to advance the cause of art by means of exhibitions of works of art, life classes, and other kindred means and to promote social intercourse amongst its members.” Highly informal, fitted out with secondhand furniture and serving supper only on Monday nights, it offered space for chess, newspaper reading, and billiards, as well as life and drawing classes. Roussel had close friends among the members, such as the sculptors Basil Gotto and John Tweed. Around 1891 he also joined the Savage Club, whose members were required to be actors, artists, musicians, writers, scientists, or lawyers, with British monarchs from Edward VII to George VI as notable exceptions. According to his stepdaughter, Marion Melville, he went there “most evenings, and greatly enjoyed it. The members appreciated his wit and charm, and . . . he knew most of them, including writers and actors.” While also a member, Whistler was dismissive of the Savage, calling it “‘a club to belong to, never to go to.’”

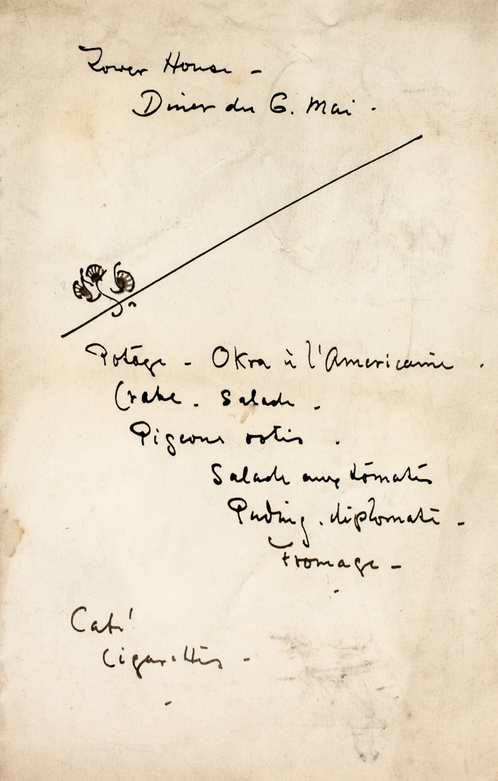

As the Pennells describe, Whistler did his best to eat in company every evening, and—in addition to club suppers—he held dinner parties at home with a frequency that could be astonishing. According to his most recent biographer, Whistler presided over at least twenty-seven dinner parties during the last four months of 1877 as well as the Sunday breakfasts he had begun hosting in the early 1870s as a way to foster relationships with dealers and collectors. Entertaining at home occurred through the 1880s; a copy of his handwritten dinner menu for May 6, 1889, details a six-course meal that included okra soup, American style; crab salad; and roast pigeon and concluded with coffee and cigarettes (fig. 42). This gathering took place at Tower House on Tite Street in Chelsea, where Whistler and his wife lived at the time. Roussel was evidently one of the guests that evening, as his copy of the menu was passed down and remains in a family collection.

Social connections—whether forged at clubs, during meals at home, or elsewhere—could lead to commissions and even inspiration. Lady Archibald Campbell, born Janey Sevilla Callander, was a fashionable patron of Whistler’s. Lady Archie, as she was called, asked the artist to paint her portrait around 1882, and he made two starts before arriving at an inspired, less formal version that portrayed her in both modern dress and an unconventional pose. Whistler also made an oil sketch of Lady Archie in the role of Orlando in Shakespeare’s As You Like It, which she performed out of doors near her country house in 1884; he was among the fashionable crowd in attendance.

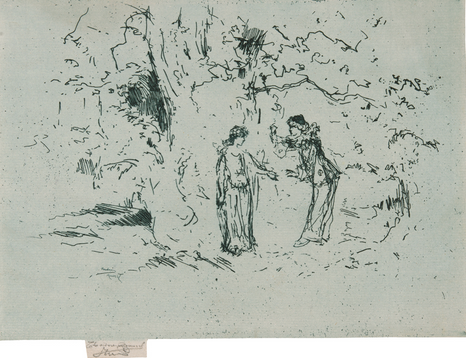

Lady Archie served briefly as a muse for Roussel after a probable introduction by Whistler. Four years later, as Lord and Lady Campbell continued to promote outdoor theater, he was in the audience for a performance of Théodore de Banville’s Le baiser, which was presented before “a large and fashionable audience” in Cannizaro Wood in suburban Wimbledon in August 1888. Roussel made two etchings, one drypoint, and one highly finished pastel showing Lady Archie in costume for her role as Pierrot. One etching, entitled The Pastoral Play—evidently sketched on the copper etching plate on the spot—portrays her in a scene with another actress (fig. 43), while the other works focus on details of her face and costume. The production also inspired the artist to arrange a formal sitting with Lady Archie to more carefully record the details and subtle effects of her all-white costume. Both the delicate drypoint Pierrot, Portrait of the Lady A. C. (fig. 44) and the related pastel, Ma fonction est d’être blanc (current location unknown), show Roussel working through challenges inherent in depicting the color white, a task that his mentor Whistler had assigned himself between 1861 and 1865 in his Symphony in White paintings.

Whistler and Roussel enjoyed a close relationship beginning in the late 1880s, and their parallel work in transfer lithography in the early 1890s is emblematic of their artistic links. The intensity of their association diminished, however, after Whistler moved to Paris in 1892 and was further weakened when he took offense at an imagined slight on the part of Roussel, whose letter of condolence following Beatrice Whistler’s death in 1896 was written in English rather than French, the language in which the two had habitually corresponded. A rapprochement came three years later, when Whistler broke the silence with a letter to Roussel—in English—and Roussel responded in French; their last recorded correspondence dates from 1901, two years before Whistler’s death, when his health was in serious decline. As Whistler faded and then disappeared from the scene, Roussel continued to experiment with color printmaking and strengthen his relationships with younger artists, extending their creative network to a new generation.

Meg Hausberg

![Detail of Roussel’s Study from the Nude, Woman Asleep (1890–94 [fig. 8]) showing thin white lines incised in the shading. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Meg and Mark Hausberg,](https://publications.artic.edu/whistler/sites/publications.artic.edu.whistler/files/figures/thumbnail/Screen%20Shot%202015-05-07%20at%203.19.29%20PM.png)