This sculpture, which depicts Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of erotic love, sexuality, and fertility, is a Roman version of the renowned statuary type known as the Aphrodite of Knidos. The original sculpture, which was carved in the mid-fourth century B.C. by the famed Greek sculptor Praxiteles, was acclaimed for its daring and innovative representation of the goddess, the first monumental nude representation of a female deity in the classical Greek world. The statue was characterized not only by its nudity but also by its contrapposto stance, with the right hand placed over the genitalia. This pose, understood to be an innovation of Praxiteles, is one of the defining features of the Knidia, as the statue is frequently described by modern scholars. Rather than concealing her genitalia, the position of the hand calls attention to the source of the goddess’s power via her sexuality, fertility, and dominion over erotic love.

The original statue functioned as the cult image for the goddess’s worship at Knidos, a city located on the western coast of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), where it was installed in a temple or shrine. It was renowned not only as a cult statue but also as a local attraction, drawing attention from travelers, writers, and seafarers who marveled at its beauty and allure. From the late Hellenistic period onward, the statue from Knidos came to inspire numerous later sculptures of the goddess (both large and small scale) in a similarly unclothed state, thus making her nudity one of her most defining attributes. While many versions closely evoke the posture associated with the Knidia (seen in the Art Institute’s example), others display considerable variety in their poses. The Knidian statue’s popularity continued throughout the Roman empire, when the famed statuary type and the many variations on it were reproduced and adapted in new ways for distinctly Roman contexts. Even into late antiquity, the Aphrodite of Knidos continued to be held in such high esteem that the original statue was carried off to Constantinople to adorn the Palace of Lausos, where it was purportedly destroyed in a fire around A.D. 475.

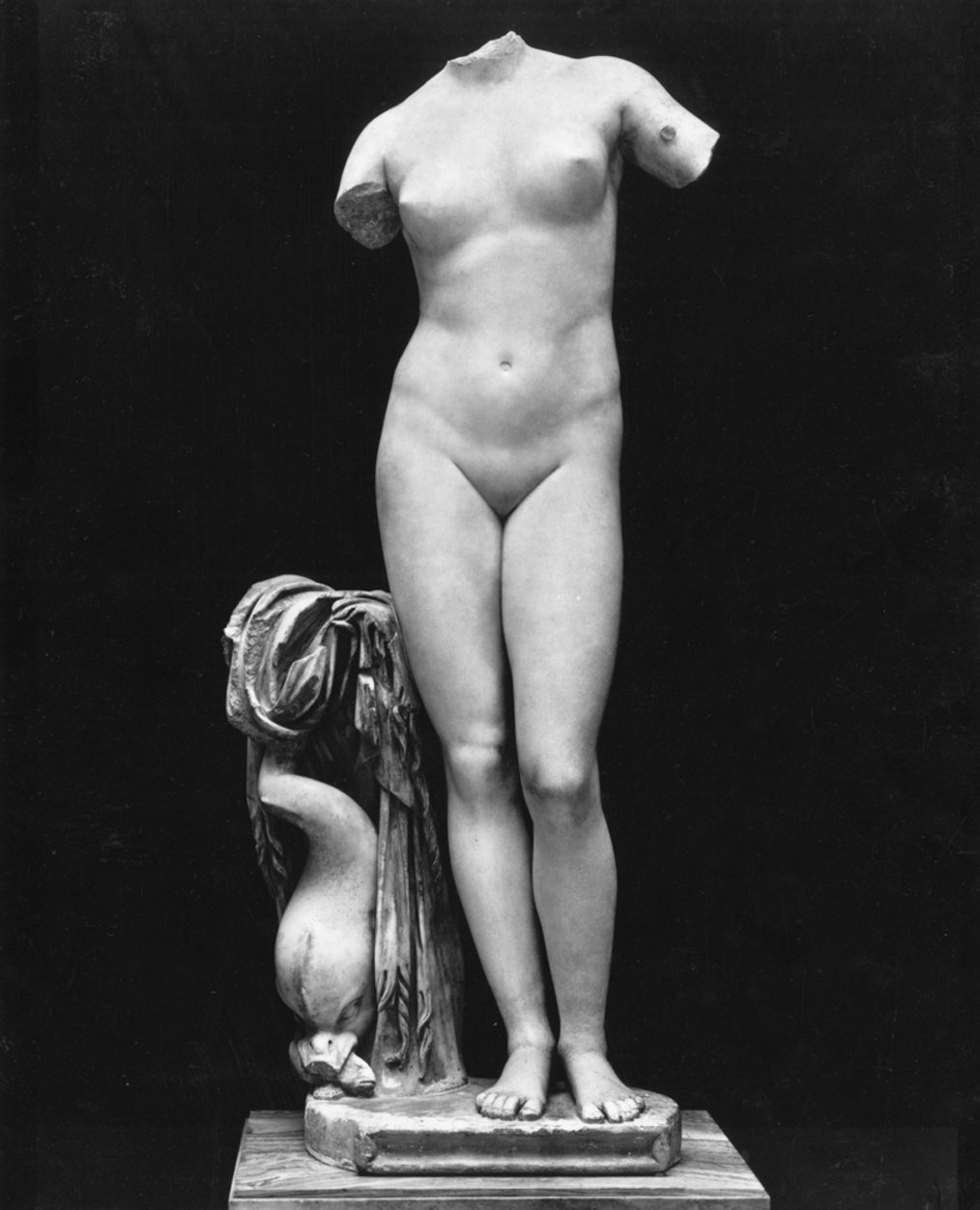

The Art Institute’s Statue of the Aphrodite of Knidos is a full-length representation of the famed cult statue of the goddess made during the Roman imperial period. To this author’s knowledge, the Chicago Aphrodite is the only over-life-size example currently in a museum collection in the United States. Carved from Pentelic marble, the statue is fragmentary but preserves much of the body, although it is missing its head, the majority of the proper left arm, the proper right wrist and hand, and the support that once stood to its proper left. Moreover, the surface of the statue is largely weathered and exhibits prominent vertical striations along the length of the body. Despite its fragmentary state and the poor surface condition, it is possible to identify the figure as a representation of the Knidia due to its nudity, contrapposto stance, and evidence of the now-missing proper right hand over the genitalia, the placement of which is indicated by the remains of a strut on the proper right thigh that would have supported the weight of the arm. More specifically, the placement of the hand is indicated by the remains of a strut on the proper right thigh, which would have supported the weight of the proper right arm. Additionally, there are three small struts on the proper left thigh, which would have provided support for the fingers of the proper right hand (fig. 13.1).

The fragmentary proper left upper arm, encircled by an armband carved in relief, points downward (fig. 13.2), apparently toward the now-missing support, which would have been attached to the body via the strut on the outer side of the proper left thigh (fig. 13.3). This support probably took the form of a swath of drapery held in the goddess’s left hand, which hung down over a hydria at her feet. It might have resembled the arrangement in the Colonna Aphrodite (fig. 13.4), an example of the Knidian type that is thought by some scholars to exhibit the greatest formal similarities to the long-lost Praxitelean statue.

The support in the form of a hydria also served an iconographic purpose. It not only alluded to the goddess’s origins in the sea, but it also might have suggested the goddess’s use of water in cleansing and rejuvenation. Additionally, it has been suggested that the hydria might reflect the classical Greek concept of the jar or container as a symbol for the womb, or more broadly, for the female body. Due to its associations with the traditional women’s responsibility of obtaining water, the hydria was especially emblematic of the female sphere. When employed in the image of the Knidian Aphrodite, the hydria’s rounded forms might similarly have evoked those of the goddess, highlighting her fecundity and sexuality.

No traces of pigment have been identified on the Chicago Aphrodite. However, it seems likely that details such as the hair, irises of the eyes, and lips could have been added in paint to enliven the sculpture. Moreover, the armband in relief on the proper left arm was likely gilded, not unlike what one finds in a statuette from Pompeii, which is adorned with a gilded necklace, bikini, and armbands (fig. 13.5). Additionally, the armband on the Chicago statue appears to have incorporated relief decoration, the appearance of which cannot be fully distinguished.

As a Roman version of an earlier, renowned Greek cult statue, it is important to consider not only where the Chicago Aphrodite might have been displayed in antiquity but also how it might have been understood by its audience.

Aphrodite Meets Venus

The Greek Aphrodite and the Roman Venus were best known in their respective cultures as goddesses of love, beauty, sexuality, and pleasure, although their roles within this larger sphere varied. Aphrodite was associated with the sensuous pleasures of erotic love as well as a more aggressive form of female sexuality. In the Greek world she was viewed as a skilled and often brazen seductress, who used her unrivaled beauty to attract her lovers, including the war god Ares (the Roman Mars), with whom she had a notorious extramarital affair. Venus, on the other hand, had long been construed as an exemplary Roman matron, who was associated with the chaste and modest sexuality of the marriage bed. Despite these distinctions, both goddesses served as models for brides and matrons in their respective cultures, guiding them to cultivate their appearance in ways that would make them sexually attractive and would thus encourage the production of children, thereby ensuring the continuation of society.

Over time, the general similarities between the two goddesses appear to have encouraged their association in the Roman consciousness. In particular, Venus had absorbed Aphrodite’s role as the mother of Aeneas, the Trojan hero who settled in Italy after the fall of Troy. Aeneas’s son, Ascanius (also known as Iulus), founded and ruled the city of Alba Longa, which made Aphrodite an ancestor of its royal line, and thereby of Romulus and Remus, the twins associated with the mythical founding of Rome. Aphrodite (and by extension, Venus) was therefore viewed as both the mother (genetrix) of the Roman people and the Julian family, the latter of whom traced their lineage to Ascanius/Iulus, which made the goddess their direct ancestor. By the early empire, a visual correlation between the two goddesses had also developed, through which the Hellenic forms and styles used in the representation of Aphrodite began to be employed in images of Venus, including the fully and partially nude types based on the Knidia. While the Roman representations of the nude Venus were predominantly Greek in appearance, such images also carried with them distinct messages pertaining to the goddess’s roles within the Roman context.

Display Contexts

The Public Sphere

It is possible that the Chicago Aphrodite may have been displayed in a large-scale civic building. In the imperial period, enormous architectural monuments such as bath complexes, libraries, theaters, and amphitheaters had begun to populate the Roman landscape. These enormous structures were found not only in the capital but also in the provinces, particularly in Asia Minor, where the richness of the marble resources helped facilitate their construction. Such buildings were typically constructed with rows of niches and projections flanked by columns, which were intended for the display of large-scale sculptures. The sculptural programs of these structures frequently included images of deities, mythological figures, and heroes, along with portrait statues representing members of the imperial family as well as local elites and benefactors.

Within public sculptural assemblages, specific subjects were often chosen to reinforce the particular function of the structure at hand. This approach to sculptural display was advocated by the Roman architect Vitruvius, who argued that statues should be of an appropriate type and subject for the building in which they were displayed in order to elucidate the space’s function. While many sculptural assemblages in Roman public buildings do not adhere closely to Vitruvius’s dictum, whether as a result of phases of renovation or variations in expected functions, it is nevertheless possible to identify some general trends in the selection of specific types of ideal statues for particular contexts.

For example, Venus found a special home in structures associated with water. Aphrodite’s origins in the sea appear to have been incorporated into Venus’s background, and this, coupled with an association with bathing, made images of Aphrodite/Venus a natural choice for watery contexts. Consequently, Venus was an especially popular subject in the context of the baths (thermae), as attested by the discovery of numerous nude or nearly nude statues of the goddess in complexes located in various regions of the empire, particularly in Rome, North Africa, and Asia Minor. One of the finest nude statues of the goddess was found in a bath complex at Cyrene, which was begun under Emperor Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117) and restored and completed by his successor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–38) (fig. 13.6). Although the statue is lacking its arms below the shoulders, its pose resembles that of another Knidian variant known as the Aphrodite Anadyomene, in which the goddess is shown wringing out her wet hair or tying it with a ribbon, along with a dolphin at her side—a further reference to her marine origins.

While Venus’s nude, attractive body undoubtedly contributed to the overall sense of pleasure that abounded in the baths, it might also have served a more instructive purpose. More specifically, her nudity might have reminded viewers of her use of water in the beautification process and also in her preparation before sexual activities and her cleansing afterward. Indeed, in examples of the Knidian sculptural type, the depiction of the hydria and drapery at the goddess’s side undoubtedly added further support (both structural and iconographic) to the theme of bathing (see fig. 13.4).

Statues of Venus are also attested on monumental fountain complexes (nymphaea). Such fountains not only provided the residents of Roman cities with much-needed fresh water and physical refreshment, but they could also reflect the symbolic and social ideals of a specific community. For example, statues of Venus are attested on two monumental fountains at Ephesus, where the goddess was also venerated as a local deity.

More broadly, the representation of Venus in such public settings could also convey specifically imperial messages to viewers. As the ancestress of the Romans and the imperial family, her Hellenized image was widely employed in the public sphere in an effort to provide “an attractive representation of imperial power for those who were subject to it.” Venus’s idealized, voluptuous body not only suggested her ability to guarantee the fertility of the empire and its continued success, but also identified her as the embodiment of felicitas temporum. Thus, Venus’s sensuous form, with its suggestion of the goddess’s fertility and sexuality that contributed to the growth and continuation of the Roman populace, reinforced the goals of both the family and the state.

The Private Sphere

As noted above, the beauty and eroticism of the Knidian type, as well as that of its later variants, undoubtedly made the image of Venus desirable for private enjoyment in the setting of the home, where it presumably contributed to the pleasurable experience of otium and the “good life” that was cultivated privately by many Romans. The sensuous, divinely nude body long associated with Aphrodite came to reinforce the Roman goddess’s own associations with the realm of beauty and sexuality. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the nude female sculptural forms associated with Aphrodite were popularized first in the domestic context, where they flourished the longest.

Images of the nude or nearly nude Venus were quite popular in Roman domestic contexts, where they presumably conveyed messages of beauty, sexuality, fertility, and pleasure (see fig. 13.5). Life-size and larger statues of Venus appear to have been rare in all but the most luxurious residences, undoubtedly due to the high cost of commissioning or purchasing large-scale versions of ideal sculptures. For instance, a life-size version of the Knidian type known as the Venus Braschi was found in the lavish Villa of the Quintilii outside of Rome (fig. 13.7). More frequently, the sculptures of Venus found in residential contexts take the form of marble or bronze statuettes, which likely served both decorative and religious functions as dedications used in the worship of the goddess at domestic shrines.

It is also possible that a patron might have deliberately selected a sculpture of the Knidian type for its ability to evoke the prestige and aesthetic appeal of the famed Greek cult statue, establishing the owner as a culturally refined and erudite individual. While it appears that many collectors did not desire exact copies of Greek prototypes, the selection of a statue that alluded to a renowned Greek work of art could have indicated that its owner was well versed in the language of earlier Greek and Hellenistic images that had become the “accepted visual currency” of the empire.

Images of Venus were especially popular in the setting of the garden (hortus), undoubtedly because of the goddess’s association with agriculture. In the Roman world, the garden was used not only for the production of fruits and vegetables but also for leisure and pleasure, particularly when set within a peristyle, a space associated with physical enjoyment and intellectual engagement. Here the goddess’s voluptuous female form and its associations with fertility were presumably equated with the growth and flourishing of vegetation and, more broadly, with the garden’s associations with pleasure.

Thus, if the Chicago Aphrodite was displayed in a residence, it seems reasonable that it might have been found in a lavish home or villa, likely in a peristyle. One can imagine it at home among the foliage of the garden as well as images of other deities associated with fecundity and pleasure, including Bacchus (equivalent to the Greek Dionysos) and their son, Priapus.

The Funerary Sphere: Matrons as Venus

It is also possible that the Chicago Aphrodite functioned as the statuary body of a woman in a theomorphic portrait. This genre combined the body of a deity or mythological figure, including its dress, attributes, and gestures, with an individualized portrait head. Nudity, which suggested the eternal youthfulness of the immortal body, was understood to function as a costume that replaced, rather than represented, the body of the subject.

The tradition of representing women in the guise of the goddess originated at the Julio-Claudian court, where the empress and other imperial women were initially represented as modestly draped Venuses, perhaps in order to liken them to the goddess in her role as the mother of the imperial family and the Roman populace. In the late first century A.D., Venus portraits became especially popular among private subjects, particularly the female family members of imperial freedmen, who gained significant wealth and prominence due to their connections to the court and the imperial administration. Some of these portraits include a fully or partially nude body, at least two of which evoke the Knidian statuary type (see fig. 13.8). However, several examples reflect the use of the Capitoline type, a close variation in which one arm is positioned to shield the breasts (see fig. 13.9).

Such portraits are largely associated with the funerary context, which appears to have been the only suitable setting for representing a matron in the nude. In this context, the Venus portraits would have served a commemorative function, praising the deceased woman’s feminine virtues and comparing them favorably with those of the goddess. Moreover, by incorporating a statuary body type that had its origins in a renowned cult image, it is possible that the portrait might have carried some sense of the sacred aura of the original statue.

In examples of the Venus-type portraits, the portrait head frequently includes an individualized visage, often depicting a mature woman wearing a composed expression that tempers the eroticism of the nubile, youthful body. In addition, the hairstyle is typically an elaborate, contemporary coiffure that attests not only to the fictive nature of the nude body but also to the subject’s careful maintenance of her appearance. For example, a portrait in Copenhagen depicting a woman (perhaps Marcia Furnilla?) in the guise of Venus combines the voluptuous, nude body of the Capitoline Aphrodite type with the likeness of a middle-aged matron (fig. 13.10). Here her carefully coiffed hairstyle, which was likely formed in part with a separately attached hairpiece, attests not only to her cultivation but also to her modesty, as the hairpiece would have partially disguised her actual appearance. When placed in a funerary context, such portraits might have identified the deceased as a model of womanly virtues, who had earned such elaborate commemoration by her family and household.

If the Chicago Aphrodite functioned as a portrait body depicting the subject in the guise of the goddess, it was likely carved from a single block of stone, as the neck is lacking a hole for the pin or dowel that would have attached a separately carved head. By the second century A.D., sculptors had begun to carve large-scale sculptures from single blocks of marble with greater frequency, in part due to an increasing availability of large blocks of high-quality marble for ideal sculptures and portrait statues alike. Thus, the absence of a hole does not preclude the possibility that this statue served as the portrait body of a Roman matron. However, given the very limited number of portraits in the guise of Venus in general, let alone as Aphrodite of Knidos, it seems less likely.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s Statue of the Aphrodite of Knidos clearly reflects the renowned Knidian statuary type. Due to its over-life-size scale, it was undoubtedly a costly and luxurious commission, which would likely have offered an appealing image of the goddess of love, sexuality, and fertility that would have been appropriate for a variety of contexts.

If the statue was displayed in a public setting, it would likely have been in the context of a structure associated with water. While Venus is frequently associated with baths, this statue may instead have adorned the facade of a major civic building, such as a monumental fountain complex. It is also possible that it was displayed in a elite residence, where the beauty and erotic appeal of the nude goddess would have contributed to the lavish setting. If this was the case, it would likely have been considered suitable for the setting of the peristyle garden due to Venus’s associations with vegetation, fertility, and pleasure. Alternatively, it is possible that the sculpture functioned as a statuary body for a funerary portrait of a Roman matron. However, such portraits appear to have been created primarily as commemorative portraits for funerary contexts and are attested in limited numbers.

Wherever the Chicago Aphrodite was ultimately displayed, it would have functioned as a multivalent image that evoked both the Greek artistic past and the distinctive roles of the Roman goddess.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This over-life-size sculpture, modeled on a fourth-century B.C. Greek original from Knidos, depicts the goddess Aphrodite nude, in a contrapposto stance (fig. 13.11). The object was carved in the round from a single block of fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Pentelic. The extensive weathering of the stone has obliterated any traces of toolmarks from the surface. The object is highly fragmentary and has sustained considerable losses, some of which have been restored with plaster. The fills were tooled and toned to match the surface texture of the stone, which is principally characterized by deep channels and grooves running vertically along the sculpture. These grooves are related to the original bedding plane of the parent limestone and indicate the grade of metamorphism achieved by the marble. No evidence of polychromy or gilding has been detected. No written records of treatment accompany the object in either the conservation or the curatorial files.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

Where it is visible in exposed areas, the interior of the stone is bright white. The fine, granular texture is accentuated by the pervasive glint of phyllosilicates. Burial in a presumably iron-rich soil has given the exterior of the object an overall orange-pink tone.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2 (present); graphite, C (abundant); K-mica, X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4 (present)

Petrographic Description

A sample roughly 0.6 cm high by 2 cm wide was removed from an area of incipient cleavage at the front bottom edge of the base, approximately 12 cm in from the front proper left corner. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.80 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: embayed

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some intercrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 13.12

Provenance

Marble type: Pentelic (marmor pentelicum)

Quarry site: Mount Pentelikon, Athens, Greece

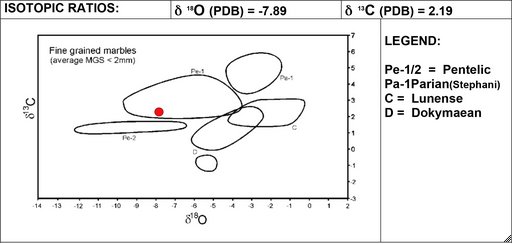

The determination of the marble as Pentelic was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 13.13

Fabrication

Method

The entire object was carved in the round from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Owing to the weathered condition of the stone, no traces of toolmarks are visible on the surface of the object.

To provide additional support for comparatively weak or suspended elements, the sculptor made use of struts. The remains of a strut are visible at the top of the proper right thigh near the groin (fig. 13.14). This projection of stone would have made contact with the inside of the proper right wrist and served to support the weight of the arm. Three small struts on the proper left thigh would have supported the fingers of the figure’s proper right hand as they covered her genitalia (fig. 13.15). Remains of a larger strut or bridge appear on the outside of the proper left thigh (fig. 13.16). Although the strut is heavily eroded and has taken on a wedge-like shape, its outline is a narrow, vertically oriented rectangle. This projection was perhaps once connected to a larger support structure to the figure’s proper left. Two concave depressions on the insides of both calves suggest that a bridge or strut once connected the legs in this area (fig. 13.17). This strut was presumably broken during the sculpture’s fragmentation prior to burial, leaving the resulting hollows. The proper right arm itself is joined to the abdomen and thus does not require additional support.

Close inspection of the armband reveals that it was once embellished with a relief decoration of some kind (fig. 13.18).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Visual examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The object is fragmentary and is composed of the following pieces: (1) the proper left portion of the base, including the proper left foot up to the ankle; (2) the proper right portion of the base, including the proper right foot up to the ankle; (3) the proper right lower leg from the ankle to below the knee; (4) the proper left lower leg from the ankle to below the knee; (5) the proper right thigh including the knee; (6) the proper left thigh including the knee; and (7) the upper body, including the groin and buttocks, the torso, the proper right arm, a portion of the proper left arm, and a portion of the neck.

The sculpture sustained a great many losses associated with fracture, some of which are considerable: around the proper right hip and thigh, below the proper right knee, around the proper left hip, across the proper left flank and buttock, around the center of the abdomen on the proper left side, around the proper left ankle, and on the outside of the proper left breast. These areas were filled using plaster or a very fine mortar and were toned and textured in an attempt to mimic the surrounding stone (see fig. 13.19). The stone around the margins of the fills appears heavily abraded, indicating that the restorer did not take particular care in protecting these areas during treatment. The wedge under the proper left foot was also replaced with a plaster or mortar fill (fig. 13.20). In front of this new wedge, the surface along the inside of the foot has been abraded with a scraping tool.

The object is missing the head, the proper right hand from above the wrist, the proper left arm from above the elbow, and the front portion and much of the proper left side of the base. Other minor losses are also in evidence. On the proper left foot, the big toe is missing, and the middle toe is badly eroded, giving the digit a triangular appearance (fig. 13.21). The outer edge of the proper right breast is missing. A loss on the outside of the proper left arm extends into the surface of the break edge and appears to be somewhat new.

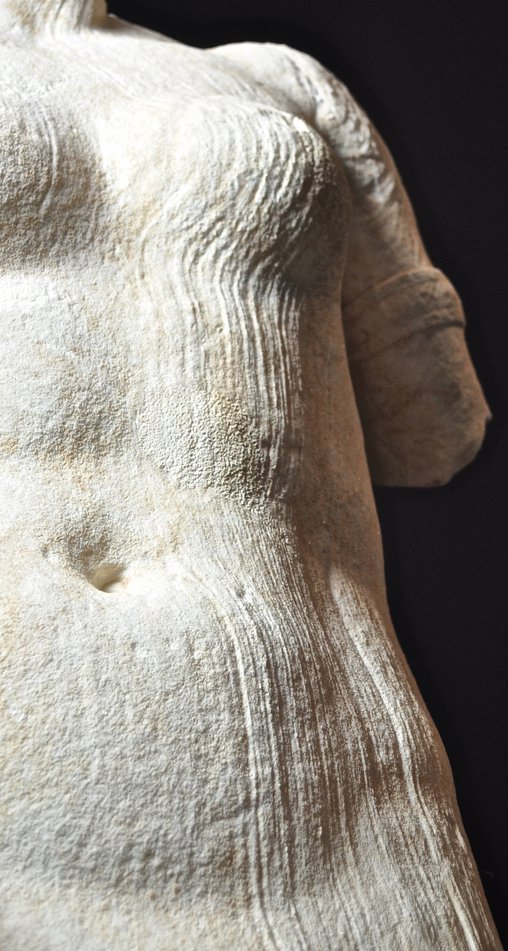

Prominent striations run vertically along the length of the body (fig. 13.22) and are especially deep on the back on the proper right side, on the back of the proper left thigh (fig. 13.23), and on the back and the outside of the proper left lower leg. The deepest of the striations on the back show incrustations of what appears to be redeposited calcium with a visible network of open pores (fig. 13.24). The proper right side of the object is relatively free of these surface features. The deep grooves and channels, related to the bedding plane of the original limestone, illustrate the relatively weak foliation of the stone, which indicates the comparatively low grade of regional metamorphism achieved by the parent rock.

Deep gouges and scratches are present overall. The most noticeable of these are along the proper right inner thigh, on the back near the neck, on the back of the proper left leg, on the proper right side of the chest, across the abdomen, below the proper left shoulder in the front, and across the instep of the proper right foot. These disfiguring marks are likely related to the object’s discovery. Three deep gouges on the top surface of the proper right forearm appear to be newer than the others.

Overall the surface of the object is heavily weathered. Spalls and lacunae, visible throughout, are also considerably eroded. Various ocher and dark-brown surface accretions and stains, with isolated patches of localized iron staining in the form of orange-red deposits, are also evident (see fig. 13.25). Many of the ocher-colored stains appear around the plaster fills and are thus likely associated with those repairs.

On the base, cracks with incipient cleavage are visible on the back proper right corner and the front proper right corner. On the back proper right corner, a deep furrow bisects the crack (fig. 13.26). This feature seems intentional rather than accidental, but it is unclear what its purpose might be.

Conservation History

There is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection.

The object was presumably unearthed in its fragmentary state and reassembled immediately thereafter. It is likely that both mechanical and adhesive means were used to rejoin the fragments. It is unknown whether the plaster fills were part of the original campaign of restoration following excavation or whether they were introduced at a later date.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini