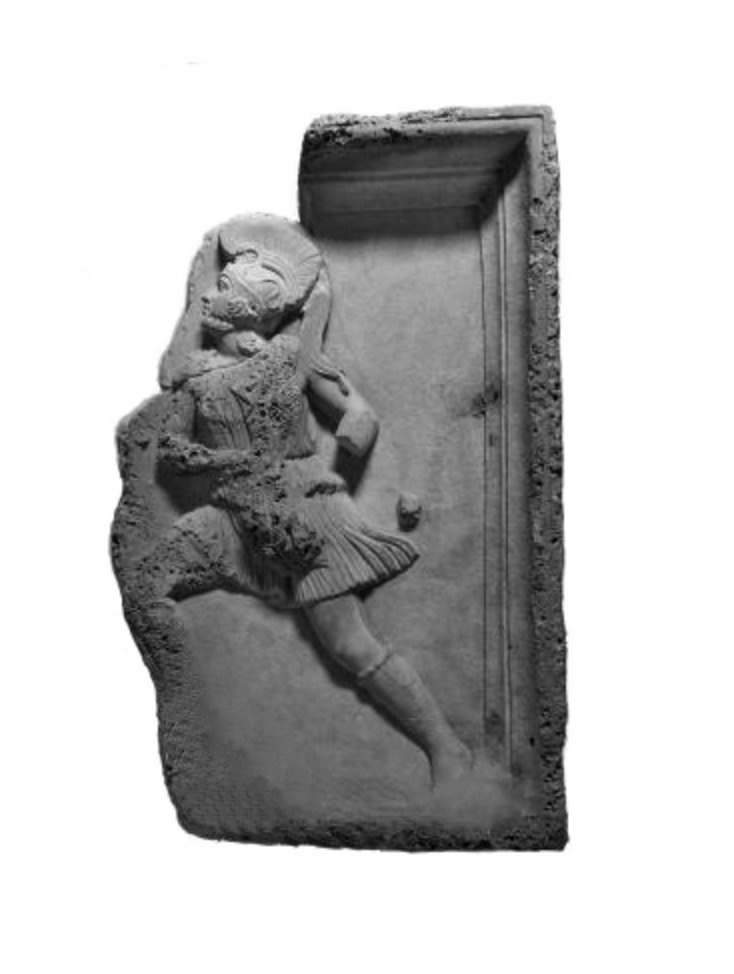

Cat. 11

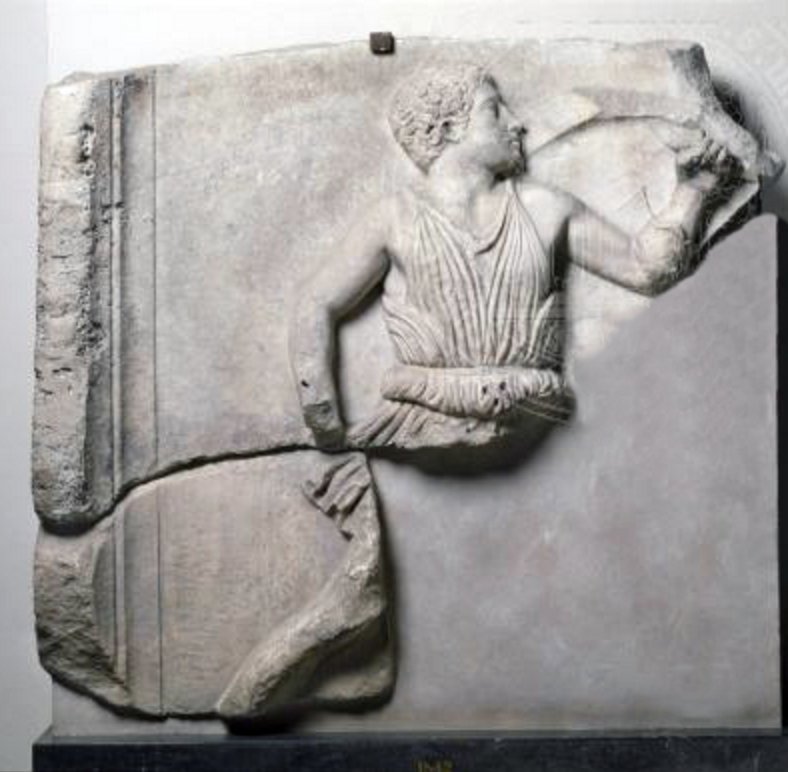

Relief of a Falling Warrior

2nd century A.D.

Roman

Marble; 53.3 × 81 × 17.5 cm (21 × 31 15/16 × 6 7/8 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Alfred E. Hamill, 1928.257

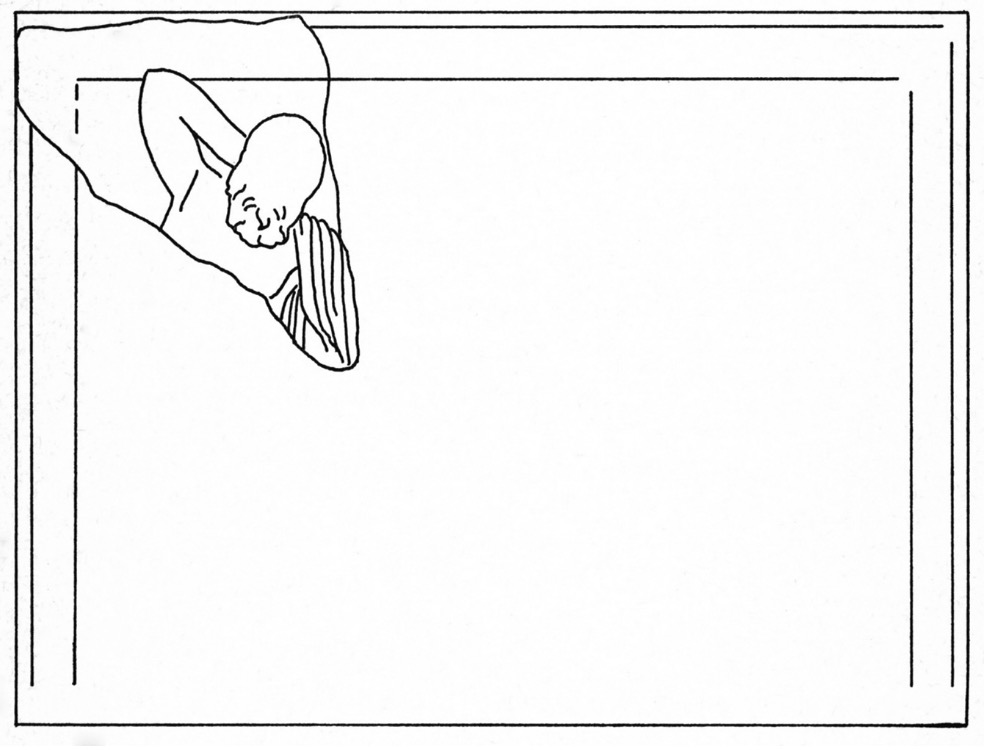

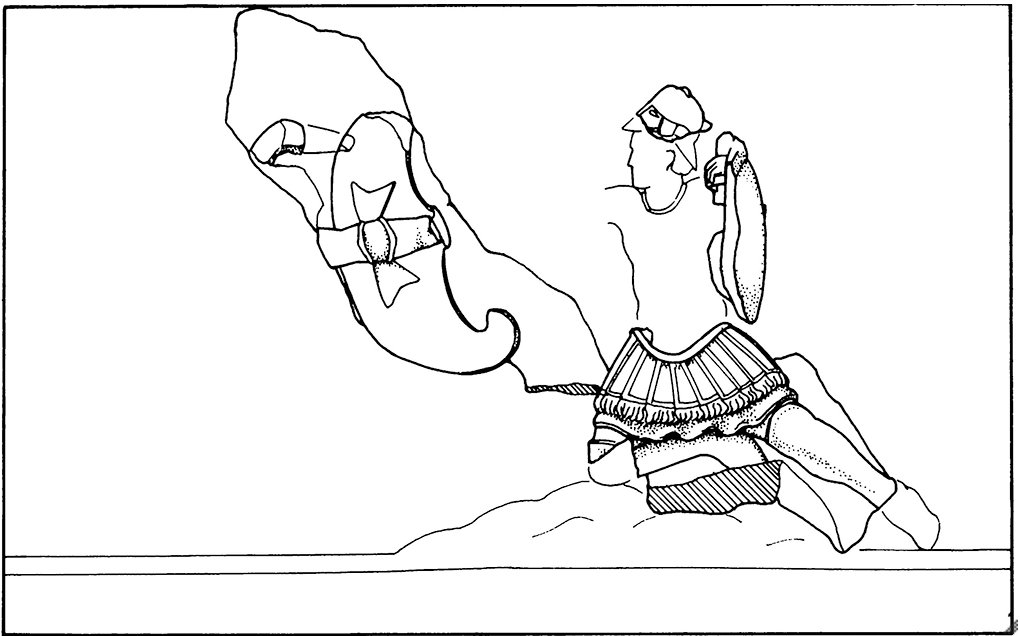

This Roman marble relief, which depicts a nearly nude, mature Greek warrior wearing a chlamys over his left shoulder and sinking to the ground onto his right knee, was discovered by 1925 at sea, off the coast of Athens (fig. 11.1). It was found along with another relief fragment, which depicts a Greek youth dressed in a chiton charging forward with a shield on his left arm (fig. 11.2).

Made of Pentelic marble, the Relief of a Falling Warrior is dated to the second century A.D. and is identified as a work of the Neo-Attic style. This term is used to describe artworks (primarily marble reliefs but also other marble objects of decorative and perhaps religious function) that were produced from approximately the mid-second century B.C. through the second century A.D. and that consciously evoked the classical styles of Greek sculpture produced in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.

As a Neo-Attic artwork, this relief displays a variety of classicizing features. For example, the figure exhibits an idealized, almost expressionless face, the primary sign of the warrior’s maturity being his thick, full beard (fig. 11.3). The shallow carving of the beard is echoed in that of the locks over his forehead, which are held back by a taenia. His muscular torso exhibits thoughtful and subtle modeling, which contrasts with the more simplified carving of the chlamys over his left shoulder and the shield in his left hand. The figure’s pose reflects a controlled movement of the body marked by restraint and composure despite his apparent descent. In this way, the relief recalls the classical style of the fifth-century B.C. Greek sculptor Pheidias, who was renowned in antiquity for his ability to create sculptures of an impressive scale, evoking dignity and gravity, as exemplified in the now-missing monumental cult statues of the Parthenon in Athens and the temple of Zeus at Olympia.

However, the relief also displays features that suggest its creation in the Roman imperial period. For example, the highly polished surface of the figure’s chest, a technique that was employed particularly in the sculpture of the Flavian period (A.D. 69–96) and into the second century A.D., suggests an imperial date. In addition, the remains of a profiled edge to the figure’s right indicate its creation as a panel (fig. 11.4). Based on its subject, style, scale, and form, it is likely that this panel served a predominantly decorative function in either a public context or a domestic setting.

Who Is the Falling Warrior?

Questions surrounding the subject matter of the Chicago relief abounded soon after its discovery, with scholars looking primarily to the position of the figure’s body as the main clue to his identity. Based on the warrior’s sinking pose and the placement of his right arm behind his head, it has generally been thought that he is falling to the ground after receiving a mortal blow from behind. Consequently, he has been interpreted as one of a number of different Greek mythological subjects who suffered a similar fate, particularly Capaneus, the mythical Greek king who was struck down by Zeus after boasting that the supreme god could not prevent him from invading the city of Thebes.

This interpretation, which has since been disproven, was originally applied to a strikingly similar relief in the collection of the Villa Albani in Rome. The Villa Albani relief, which had been known since at least the eighteenth century, depicts a nude Greek warrior sinking to the ground on his right knee in a nearly identical pose (fig. 11.5). To be sure, the two reliefs exhibit some technical variations in terms of the approaches taken to the rendering of the figure and his shield. Nevertheless, their notably similar appearances as well as their comparable dimensions suggested a common source of subject matter for both, which was identified several years after the discovery of the Chicago relief.

The Reliefs from Piraeus

The best clue about the subject matter of the Chicago relief came with the discovery of a large group of marble relief fragments in the harbor of Piraeus, the port city of ancient Athens, during dredging activities in the winter of 1930–31. A number of the Piraeus reliefs, which depict male and female figures engaged in combat, exhibit notable formal and stylistic similarities to the aforementioned relief fragments in Chicago, Berlin, and at the Villa Albani in Rome as well as additional examples in Copenhagen, Munich, and in other collections in Rome. More specifically, the Piraeus reliefs also reflect the use of classicizing features associated with the Neo-Attic style, as indicated by the depiction of idealized bodies and restrained expressions as well as the overall controlled sense of movement, even in moments of action—as for example in this largely complete relief of the so-called Hair-Pulling or Death-Leap group (fig. 11.6). Additionally, the cache from Piraeus yielded a largely fragmentary relief that appears to depict the upper body of the same figure of a falling warrior as that found on the reliefs in Chicago and the Villa Albani (see fig. 11.7), which suggests this figure’s association with the subjects represented on the other reliefs.

When considered as a group, the extant reliefs exhibit additional similarities. First, the relief panels and their figures are of comparable dimensions. According to Neda Leipen, the more complete panels average roughly 90 centimeters (35 7/16 in.) in height and 165 centimeters (65 in.) in width, while the individual figures measure (or are projected to measure) approximately 70–80 centimeters (27 1/2–31 1/2 in.) in height. Second, the majority of the fragments preserve traces of the thick, profiled edges that framed their compositions. While there is some minor formal variation among the frames, it seems likely that they were all intended to function as independent decorative panels. Third, the type of marble employed in the reliefs has generally been identified as Pentelic, a type of fine grained, brilliant white marble that was derived from the quarries of Mount Pentelikon, located some ten kilometers (6 1/4 miles) from the center of Athens. Although not widely used in Roman architecture, Pentelic marble was frequently employed during the imperial period in statuary and sarcophagi produced primarily in Athens.

Based on these stylistic and technical considerations, the reliefs are generally thought to date to the second century, specifically to the Hadrianic period (A.D. 117–38) or the early part of the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93). Consequently, it has been suggested that they might have been created in the same workshop. However, their minor technical variations, such as those noted above in the Chicago and Villa Albani reliefs, suggest more than one sculptor, either at the same time or over a period of time. Since the majority of the reliefs can be traced back to the harbor of Piraeus, it is presumed that they were on the same shipment of artworks either leaving Athens or awaiting shipment, which appears to have suffered some sort of catastrophe. It has been suggested that a fire might have been the cause of the ship’s destruction, although no traces of fire damage were conclusively identified on the Chicago relief in its most recent examination in 2013.

The Amazonomachy of Athena Parthenos

While the reason for the reliefs’ loss at sea remains a mystery, the question of their subject matter was resolved soon after their discovery, as they were identified as representing the mythical battle between Greek soldiers and Amazons known as the Amazonomachy. More specifically, they were recognized as copies of the figures from the Amazonomachy that once adorned the shield of the monumental chryselephantine statue of the goddess Athena Parthenos that stood in the Parthenon in Athens (see fig. 11.8). This enormous cult statue, which was created by the Greek sculptor Pheidias for the Parthenon from 447 to 438 B.C., is said by Pliny the Elder to have reached 26 cubits in height, or approximately 11.54 meters (37 ft. 10 5/16 in.). Although no dimensions of the shield are noted in the ancient sources, it is estimated to have measured at least 4 meters (13 ft. 1 1/2 in.) in diameter. Based on the proposed dimensions of the original shield, it has been suggested that the figures depicted on the reliefs might be represented at the same scale as their models.

The representation of the battle of the Greeks and Amazons on the original statue’s shield is thought by modern scholars to be more than a depiction of an ancient myth. Rather, it is often believed to have functioned as an allusion to the Greco-Persian Wars that raged in roughly the first half of the fifth century B.C. Although it has been suggested that the images of Amazons on the shield were thinly veiled representations of Persians, through which the latter were stigmatized as feminized men, it seems more likely that the former were instead viewed as ancient, mythical precursors of the Persian Empire.

While the original cult statue of Athena Parthenos does not survive, evidence of its appearance, including that of the shield, is attested in a limited number of ancient literary sources. Visual evidence of the shield’s appearance is more prevalent and is found in a number of marble statuettes that reproduce the goddess’s image as well as several independent marble reliefs depicting the shield itself (see fig. 11.9). Despite their reduced dimensions, it is clear that the shield reproductions include many of the same figures of battling Greeks and Amazons found on the reliefs in Chicago, Rome, Piraeus, and elsewhere, which I henceforth refer to collectively as the panel reliefs in order to distinguish them from the reduced-scale shield reliefs.

The Falling Warrior and the Amazon?

While the figure of the falling warrior is found on three of the panel reliefs (those in Chicago, the Villa Albani, and Piraeus), it also appears on three of the shield reliefs, including the shield of the Patras statuette (fig. 11.10), on which it is most clearly preserved; the Strangford Shield relief (fig. 11.11), where its left leg and perhaps part of its right leg remain; and the highly fragmentary relief formerly in Boston (fig. 11.12), on which he is the sole remaining figure. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the figure belongs to the Amazonomachy scene. More important, the evidence of the shield reliefs enables the identification of the falling warrior’s position within the shield composition, which in turn allows for a consideration of his relationship to the surrounding figures.

On the shield reliefs as well as a number of the panel reliefs, the majority of figures were depicted in pairs, each typically comprising a Greek and an Amazon engaged in battle (see fig. 11.13). While the Chicago relief does not preserve any traces of a second figure on the proper left side due to its fragmentary state, its dimensions support this possibility. More specifically, its width of 81 centimeters (31 15/16 in.) is roughly half of the total average width of 165 centimeters (65 in.), while its height of 53.3 centimeters (21 in.), although less than the average height of 90 centimeters (35 3/8 in.), suggests that it could accommodate the placement of a second figure placed on the lower proper left side. With whom, then, was the falling warrior paired?

On the Strangford Shield and the shield from Patras, the falling warrior is in the upper right quadrant, close to an Amazon, who draws her sword as she charges upward in his direction. Consequently, it has been suggested that the figures of the falling warrior and the Amazon were paired on the panel reliefs. This Amazon is attested on at least one fragment from Piraeus, on which she appears on the right side of the panel, standing in a similar pose (fig. 11.14). It seems unlikely that they originally came from the same panel because their frames differ: the innermost border of the frame of the Chicago relief is narrower than that of the Piraeus fragment. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable that this particular Amazon was the counterpart to the figure of the falling warrior in the Chicago relief in its original state.

The Warrior’s Pose

The pairing of the falling warrior with an advancing Amazon requires a reconsideration of the former’s pose, as it might affect our understanding of his function in the composition. As noted above, the warrior in the Chicago relief is generally thought to be sinking following a fatal blow from behind. However, due to the fragmentary nature of the shield reliefs and the distribution of figures on a circular composition, no figure can clearly be identified as his attacker. Consequently, it has been suggested that he was instead wounded by an arrow, which could have been shot by an archer from a great distance.

On the Chicago relief, the area behind the falling warrior’s head is no longer extant, so it is not possible to verify whether an arrow was once incorporated into the relief or added in paint. Moreover, to this author’s knowledge, no traces of arrows projecting from the warrior’s neck or back have been discerned on any other representations of this figure. Nevertheless, one can point to formal parallels that support this possibility.

In particular, the pose of the Chicago figure resembles in images of the Niobids, the children of the mortal woman Niobe, who boasted that she produced more children than Leto, the mother of the twin deities Artemis and Apollo. Following this transgression, her sons and daughters were slain by Artemis and Apollo with arrows. This episode was famously depicted on the throne of the chryselephantine cult statue of Zeus in his temple at Olympia, which was designed by Pheidias following his completion of the cult statue of Athena Parthenos. Although the throne does not survive, its imagery is known in part through later representations. For example, the episode appears on a fragmentary circular relief in the British Museum; on the lower left side is a nude male Niobid kneeling in a nearly identical pose, reaching his bent right arm toward his wounded back (fig. 11.15). Here, however, the Niobid’s head is angled upward, suggesting his pained reaction to the wound, which contrasts with the downward gaze and calm expression of the Chicago figure that was perhaps intended to convey the warrior’s honor and civic excellence.

Alternatively, one might also give the falling warrior a more active interpretation: perhaps he is instead grasping for his weapon in a valiant, final effort to fend off an approaching enemy with a powerful overhand blow. This gesture is best known from the Greek sculptural group called the Tyrannicides, which depicts the historical figures Harmodius and Aristogeiton advancing on a tyrant whom they are about to assassinate (see fig. 11.16). In this group, which is preserved in later Roman versions, Harmodius is shown holding a short sword in his right hand, with his arm held upward and cocked back in the moment before striking his enemy. No traces of the falling warrior’s hand or any weapon are present behind the figure’s head in the Chicago relief. However, if he was armed it is possible that he held a type of short slashing sword with a single-edged, curved blade, such as the kopis.

Given the restrictions of the relief format, it is possible that the falling warrior’s arm, which is bent to the figure’s right rather than backward, is a thoughtful sculptural solution to the problem of depicting an arm bent backward in the moment before striking a heavy blow. If this was the case, one could imagine that the significance of this gesture, which had long been associated with combat, was not lost on its viewers as representing one last valiant attempt at fighting back.

Display Contexts

Despite the lack of information about the intended setting of the Art Institute's Relief of a Falling Warrior, it seems reasonable that it could have been displayed in either a public context on a civic structure or monument, or in a domestic context, likely within a lavish home.

Public Context

Numerous examples of large-scale marble reliefs created for public structures have been found in the city of Rome, although provincial examples, which frequently exhibit greater variety in iconography, style, and artistic skill, are attested. Many such reliefs are quasi-historical in nature and typically represent seemingly real but potentially idealized events, in which historical personages, such as members of the imperial family, are frequently shown alongside allegorical personifications, other human subjects, and various motifs, sometimes in a recognizable locale. In this way, Roman monumental reliefs typically differ from classical Greek architectural reliefs, which commonly feature mythological scenes on a plain background.

However, some Roman monumental reliefs incorporated mythological subjects. In particular, the subject of the Amazonomachy is depicted on a number of marble reliefs associated with architectural monuments in various parts of the empire, particularly Greece and Asia Minor. For example, a number of second-century A.D. relief fragments depicting figures associated with the Amazonomachy of the Parthenos shield have been discovered in Athens in the Agora and the Kerameikos. It has been suggested that some of these reliefs might have been part of the frieze associated with a nonextant monument. Another significant example is found in a group of marble reliefs from the Hadrianic theater in Corinth, which incorporate pairs of battling Greeks and Amazons. While the Corinth reliefs do not clearly replicate the Pheidian figural types associated with the Parthenos Amazonomachy, some of the figures appear to draw on these prototypes in a more general way. For instance, the kneeling figure of a cuirassed Greek warrior depicted on one of the Corinth reliefs, although missing its arms, seems to recall the pose of the Chicago falling warrior (fig. 11.17). Moreover, the dimensions of the reliefs from Corinth correspond generally to those of the panel reliefs. Given the aforementioned examples, it is therefore possible that the Chicago relief and the related panel reliefs could have been intended for a public building, perhaps in Greece or Asia Minor, where Greek mythological subjects continued to adorn such structures.

On the other hand, it is important to consider that the corpus of panel reliefs includes multiple representations of specific figures associated with the Parthenos shield. In some cases, there are numerous pairs of the same battling figures. Consequently, the presence of duplicate reliefs would seem to discount the possibility that they were all intended as architectural decoration for a single building. Rather, they might have been intended for multiple buyers or an intermediary workshop at their final destination.

Domestic Context

The Roman house was truly a multimedia environment. Through the selection of artworks, which were often inspired to varying degrees by the subjects and styles of earlier Greek examples, domestic assemblages allowed patrons to demonstrate their cultural sophistication, personal taste, and wealth. Following the Roman principle of decor or decorum, such artworks were expected to complement and reinforce the function of the space at hand. Generalized versions of the Amazonomachy were found in a number of Roman homes in wall paintings and mosaics, and they might also have appeared on furnishings such as lamps and vessels. It therefore seems reasonable that the Chicago relief might have been intended for display in a domestic setting.

The Relief of a Falling Warrior might have been especially suited to a villa, where its subject and style might have enhanced the experience of otium. While otium generally referred to the peace and tranquility associated with retreating from one’s daily business (negotium), in the setting of the elite home or villa it was more specifically understood to refer to both the physical and intellectual pleasures associated with Greek culture and leisure, which included activities such as dining, bathing, participating in games, and engaging in conversation with friends and colleagues, which was often of a philosophical nature.

In particular, the relief might have been considered suitable for display on one of the walls of the peristyle of a residence, a form of covered colonnade that enclosed a courtyard (frequently containing a garden) at its center (see fig. 11.18). The form of the peristyle drew particularly on that of the Greek gymnasium, an institution of athletic training and philosophical discussion that was characterized by a large, open rectangular courtyard surrounded by a portico. The association between the two spaces was so strong that many Roman patrons were known to describe their peristyles as gymnasia, as for example the Roman orator Cicero, whose villa at Tusculum appears to have contained two “gymnasia” (possibly peristyles) that he named after the two main gymnasia in Athens, the Academy and the Lyceum.

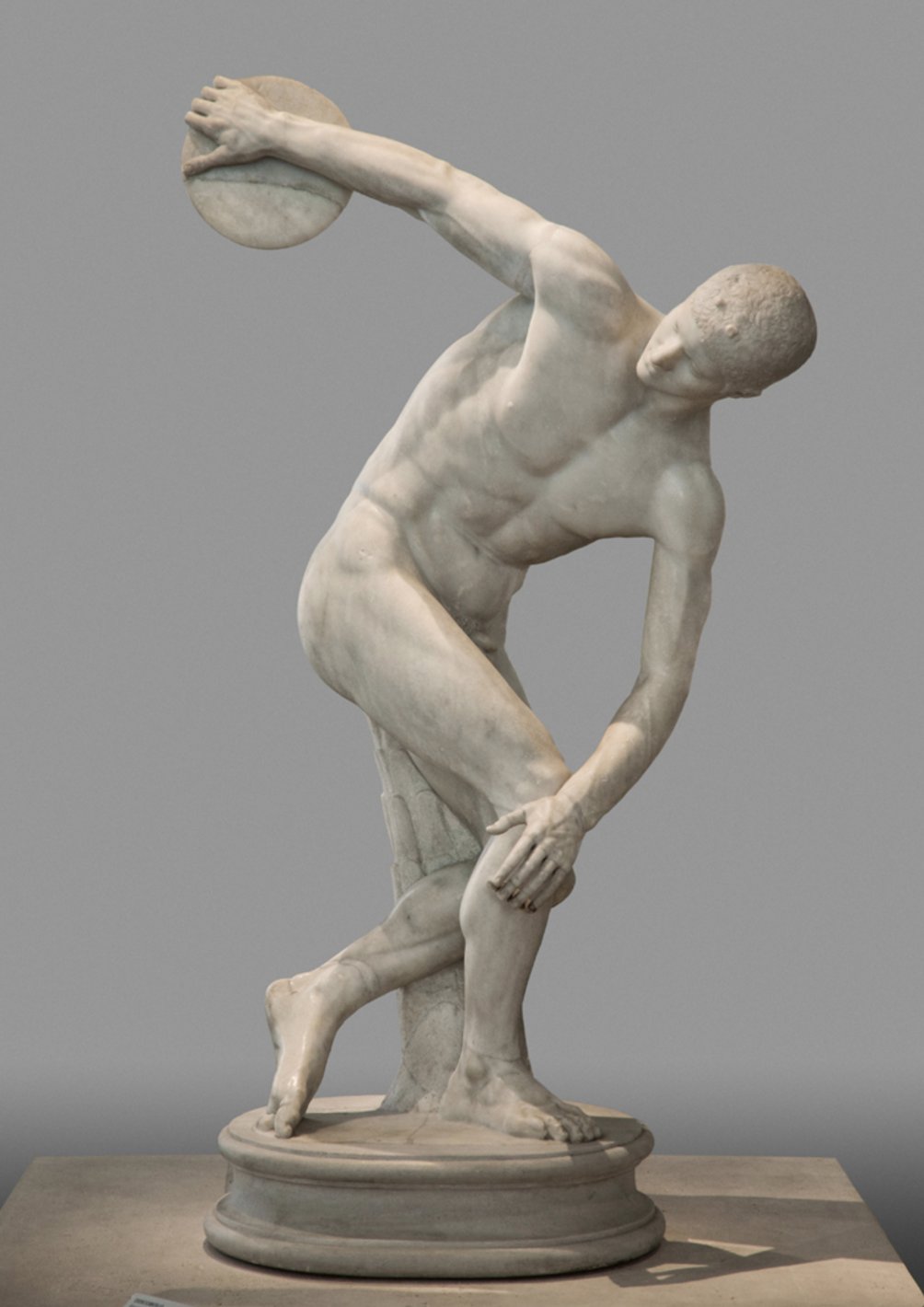

Based on the Roman peristyle’s associations with the physical enjoyment and intellectual engagement of the gymnasium, it seems reasonable that the Chicago relief would have been considered appropriate for this setting for several reasons. First, the falling warrior’s nude body and toned physique would have suggested the athletic nudity associated with the activities of the Greek gymnasium (literally, “place of nakedness”). It was customary for Greek athletes to exercise nude, which distinguished them from their Roman counterparts, who traditionally wore at least a covering over their loins. The representation of the nude male body in its idealized, muscular form suggested the Greek principle of kalokagathia (beauty and goodness, the latter in the sense of noble birth). Moreover, it reflected the Greek commitment to athletic training as well as the sense of discipline that it encouraged, both of which were critical to the development of warriors who were fit for battle (see fig. 11.19).

Additionally, the warrior’s muscular body evoked the similarly idealized heroic nudity of gods and mythological figures, an attribute that highlighted their arete. By entering battle in the nude (or nearly nude when equipped with a helmet, shield, or cloak), a hero demonstrated “a special kind of energy and transcendent fearlessness” that distinguished him from mere mortals. In the Roman villa, sculptures of attractive, nude male athletes are attested, some of which replicate famed sculptures of the classical period, such as the Diskobolos by Myron (see fig. 11.20) and the Doryphoros by Polykleitos. These Roman versions of works by Greek masters likely added a certain prestige to the owner’s collection due to their cultural cachet. While these sculptures collectively evoked the practice of Greek athletics and its increasing acceptance by Roman elites within the Hellenized sphere of the Roman villa, they also alluded to the intellectual activities of the gymnasium, which, by the late republican period, were viewed as an equally important function of this institution.

Second, the subject of the falling warrior might also have been considered appropriate to the intellectual associations of the peristyle due to its connection to the statue of Athena Parthenos. As the goddess of wisdom, Athena had long been associated with the Greek gymnasium as a setting for philosophical discussion, even serving as one of the tutelary deities of the Academy, the gymnasium in Athens where the Greek philosopher Plato taught. By extension, Athena (the Roman Minerva) was also a suitable subject for the Roman peristyle, as suggested by Cicero, who expresses his delight in acquiring a herm of Athena for his garden-gymnasium (fittingly named the Academy), a space that he even describes as an offering to the goddess. In this way, the falling warrior’s association with the cult statue might have reinforced the use of a peristyle as a setting for educated discussion while perhaps even imbuing the space with some sense of the sacred aura of the goddess.

Finally, as an image appropriated from a celebrated classical Greek statue, the relief also might have helped to demonstrate the owner’s cultural sophistication and refinement. By emulating a famed cult statue created approximately six hundred years earlier, the relief might have “established the owner as both visually learned and culturally au courant” through its associative value. It is possible that the Chicago relief was a costly and elaborate way of representing interest in and knowledge of the Parthenos. Alternatively, it might have evoked in a more general way the classical Greek style’s lofty associations.

It is unlikely that this relief would have been displayed in isolation. Rather, it may have been intended to accompany a number of the other panel reliefs depicting pairs of battling Greeks and Amazons. The panel format likely encouraged the display of multiple reliefs in a single space, such as the peristyle, where they would have provided viewers with ample topics for discussion during their leisurely walks under the porticoes. However, it is also plausible that the relief would have been displayed alongside artworks of more varied subject, style, scale, and medium. The eclectic nature of the artistic ensembles found in Roman villas appears to reflect a balance between the owner’s personal, cultural, intellectual, and religious interests and a general adherence to the conventions of decor. In turn, the relief’s meanings would have depended not only on its built context but also the viewer’s knowledge, interests, and social background.

Conclusion

In sum, as a Neo-Attic artwork, the Relief of a Falling Warrior exemplifies the Roman interest in the classical Greek style and its associated subject matter. In appropriating the falling warrior from the circular shield of the cult statue of Athena Parthenos and incorporating it into a rectangular relief, the sculptor transformed the figure from a religious image to one was that was likely intended for a Roman secular context. While its intended display context is unknown, it is possible that the relief was intended to serve as architectural decoration on a Roman public building, perhaps in the Greek East, where the tradition of depicting Greek mythological subjects on civic structures endured. However, it seems more likely that it was created to adorn the walls of an elite Roman home, such as a villa, where artworks reflecting earlier Greek subjects and styles were especially admired for their ability to enhance the experience of otium.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object, a fragment of a relief panel, depicts a warrior in the throes of battle. It was carved from a single block of fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Pentelic. Visual inspection of the stone reveals that the sculptor employed a variety of traditional carving tools and relied particularly heavily on the use of a drill. The most striking aspects of the object’s condition are those conferred on it during its long immersion in a marine environment. The fragment came to rest face down on the seabed, where its exposed surfaces were host to a variety of marine organisms. The figure of the warrior, as the portion of the object in highest relief, was pressed somewhat farther down into the sediment layer, which preserved it to a greater degree but also facilitated its colonization by anaerobic bacteria. No evidence of polychromy or gilding has been detected. During its time in the museum’s collection, the object has received three documented treatments of a restorative nature, and at least one undocumented treatment to mitigate the once-heavy incrustation of shells and calcified tubules.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The stone is cool in tone with a slightly green hue overall. Ocher discolorations are present across the surface, most notably on the torso and outstretched leg of the figure.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (very abundant); K-mica, X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4 (abundant); quartz, SiO2 (traces)

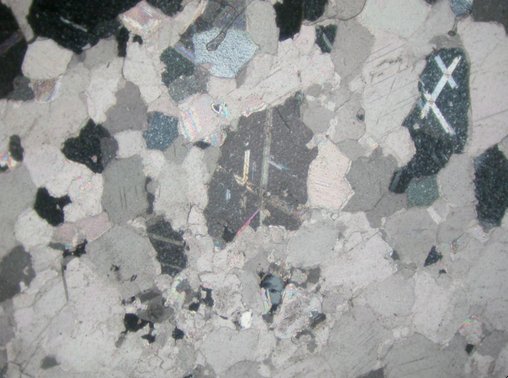

Petrographic Description

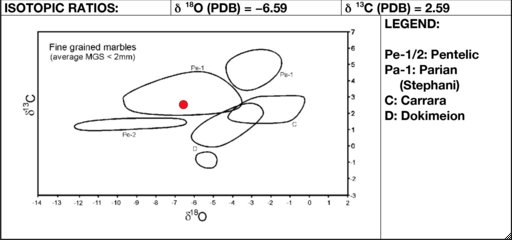

A sample roughly 2.3 cm high by 0.7 cm wide was removed from the proper left edge of the verso, approximately 4 cm from the bottom. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.80 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic, slightly lineated

Calcite boundaries: embayed

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed slight decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 11.21

Provenance

Marble type: Pentelic (marmor pentelicum)

Quarry site: Mount Pentelikon, Athens, Greece

The determination of the marble as Pentelic was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 11.22

Fabrication

Method

The object is a fragment of a relief carving that originally formed part of a panel. The remnant of a cove molding on the proper right side offers proof that the depicted scene was enclosed in a frame. The extant fragment was carved from a single block of stone that was presumably square or rectangular, using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers. The consistent thickness and the relatively planar surface of the verso suggest that the current state of preservation accurately reflects the original depth of the panel.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

A drill approximately 3 mm in diameter was employed to delineate almost all the figural elements, chiefly the shield, the chlamys, and the majority of the warrior’s body. On the proper right side of the body, a flat chisel was used at an oblique angle to sharply demarcate the torso from the background.

In several places, in particular along the top of the outstretched leg, it is clear that a drill was used during first-stage carving to render the primary outlines by piercing the stone at intervals, creating a network of deep tunnels; the masses of stone between these tunnels were then cleared with a chisel or channeling tool. This technique is readily identifiable by the circular depressions that punctuate the lines (fig. 11.23).

In other areas, such as behind the shield, the contours were described using the running drill technique, in which the drill was rotated at a sharp angle to the stone, cutting a groove as it was moved along. Lines with a distinct juddering quality provide evidence of the use of this method (fig. 11.24).

The chlamys was likely also created using these drilling methods, but its folds were refined with additional tools, such as a roundel or a rasp; clear evidence of the latter tool remains visible (fig. 11.25).

The sculptor employed a flat chisel held at an angle to skillfully render the contours of the hair, the beard, and the eyes and to bring out the small protrusions of stone that form the nipples (see fig. 11.26).

Marks made by rasps of varying fineness can be seen in multiple locations. The face of the shield—both the interior and the raised border—was roughly worked with a scraper or coarse rasp (fig. 11.27). Traces of a finer rasp are visible on the sides of the neck, in the locks of hair, and on the sides of the face (see fig. 11.28).

The sensitive modeling along the elegant curve of the brow ridge speaks to the sculptor’s virtuosity and control of the tools (see fig. 11.29). However, comparison of both sides reveals that the proper left eye and eyebrow appear to have been recut or sharpened (fig. 11.30). On this side a deep gouge bisects the brow ridge, and the desiccated appearance of the marble around the eye suggests more recent carving.

Owing to its preservation in the marine sediment, the torso appears to have retained its original polish, which would have been realized using a slurry of an abrasive material such as pumice (fig. 11.31).

An eroded remnant of a square-shaped bridge is present toward the bottom of the chlamys on the proper right side (fig. 11.32). It is not clear what purpose this bridge served or what might have been attached to the figure at this point.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The figure of the warrior is fragmentary: a large section of the proper right arm above and below the elbow is missing, as is the lower half of the body below the extended proper left leg. Most of the proper left hand has also been lost. Although all the fingers of that hand are missing, it is possible to see that it once gripped a still-visible handle inside the shield. Large ovoid lacunae can be seen on the proper left and topmost outer edges of the shield. Losses are also apparent at the top and bottom ends of the chlamys. A number of superficial scratches and gouges are present throughout, as are isolated orange stains where the stone may have come into contact with rusting iron (see fig. 11.33).

The most remarkable aspects of the object’s condition, however, are a direct result of its prolonged submersion in a marine environment. The eroded outer margins of the fragment and the gentle contours of the break edges bear witness to the ebb and flow of underwater currents. The liberally pockmarked surfaces of the stone, as well as the presence of partially adhered bivalves and calcified tunnels, are evidence of its colonization by marine organisms, most notably Pholas dactylus (see fig. 11.34 and fig. 11.35). Dark-brown stains, the result of organic acids from marine deposits, are present next to the figure’s chest on the proper right side, and nearby on the molding. Finally, the distinctive contrast between the surface condition of the figure itself and that of the rest of the relief offers clues about the object’s position on the seabed.

An archival photograph reveals that the surface of the object was once heavily encrusted with concretions, the majority of which consisted of the remains of marine organisms (fig. 11.36). Although the records are silent about when and how, it is clear that, sometime after this photograph was taken, most of these shells and tubules were removed, leaving behind only the deep pits and channels that the creatures had bored into the stone. Parallel grooves resembling the marks made by a flat chisel can be seen in the areas that once bore large concretions, which suggests that the shells were mechanically removed. These marks are most notable on the molding and along the flat face of the relief between the warrior’s torso and the edge of the frame. They are also readily apparent in the bottom proper left corner of the fragment (fig. 11.37). The archival photograph also reveals that the brown stains on the proper right side were once very dark brown or black; at some point they must have been reduced by a bleaching treatment.

The surface pitting is largely confined to a zone demarcated by the diagonal line of the warrior’s body (fig. 11.38). The shallower portion of the relief, to the proper left of the figure, extending to the top proper left corner and including the figure’s proper left arm, is much more heavily tunneled than the rest of the warrior’s body. The top of the chlamys across the warrior’s shoulder and the porpax at the center of the shield are considerably disfigured as a result of the extensive pitting. The degree of tunneling on the shield itself no doubt contributed to an overall weakening that led to the extensive losses at the outer margins. In addition, the top and proper left sides of the relief are much more heavily pitted than the proper right side, which is almost completely intact. On the bottom break edge of the relief, pitting extends across the back half; the front half is less affected.

The direct and indirect evidence of the presence of mollusks sheds light on the position of the relief on the seabed. All borers require aerobic respiration; their activity was thus restricted to exposed stone above the sediment line. Based on the concentrations of pitting and tunneling on the break edges and the verso, it is reasonable to conclude that the relief landed face down at an angle, with the verso, the top edge, and the proper left edge exposed. The areas of highest relief, as well as the front half of the bottom edge and the proper right edge, were pushed deeper into the sediment by the weight of the stone.

The facedown position is indicated not only by the torso’s remarkable state of preservation but by the fine network of tiny holes distributed uniformly across its surface (fig. 11.39). These holes were created by marine organisms that inhabit anaerobic environments, notably diatoms and sulfate-reducing bacteria.

A number of the pits and tunnels created by the various marine organisms appear to be filled with a cementitious matrix that has a slightly reddish-brown tone in contrast to the gray of the surrounding stone. This substance is most likely sediment from the seabed that hardened inside the cavities.

A well-executed restoration, only slightly visible to the naked eye, is present on the proper right side of the chest. When the object is viewed under ultraviolet radiation, the extent of the restoration becomes more legible (fig. 11.40). There is a rather large crack that traverses almost the entire width of the chest under the pectorals, from the far proper right edge of the figure to midway across the proper left side. Two secondary cracks extend downward. The longer of these ends below the proper right rib cage, and the shorter travels halfway down the linea alba toward the navel. A. D. Fraser suggested that this crack constitutes physical evidence of a fire that sank the ship carrying the relief and sent its contents to the bottom of the harbor. Cracking is certainly a possible outcome of heating marble to a high temperature and then immersing it in cold water. Visual inspection, however, is not an authoritative basis on which to draw such a conclusion. Only a petrographic examination of the affected area could securely determine whether the object was exposed to fire. If it was, the microstructure of the stone would be expected to reveal more visible and marked crystal boundaries as a result of the thermal forces.

Conservation History

During its time in the museum’s collection, the object has received three documented treatments, all of which were restorative in nature, and at least one undocumented treatment.

Sometime after 1939, the date of the archival photograph, the relief was cleaned of its concretions of shells, presumably by mechanical means.

The first recorded treatment was performed in 1982 in an effort to clean the object of ingrained dirt and soiling. Dry cleaning methods, aqueous solutions, and surfactants were all employed in this endeavor. A natural abrasive was used to clean stains identified as rust. The treatment report states as well that a small wooden implement was used “to remove bits of sea shells.”

That same year, the object was treated once again in order to remove handwritten marks on its top right edge. Following solubility tests, the black marks were removed by solvent means, although some mechanical action was also required to fully eradicate the blemishes. At the end of the treatment, the affected area was neutralized with water.

The final documented treatment, in 1988, was to repair a chip in the horizontal crack below the right pectoral. The crack itself was consolidated with an acrylic resin, and the loss was compensated with a tinted fill. The fill was further toned with water-soluble media and was itself consolidated with acrylic resin.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini

Exhibition History

Art Institute of Chicago, An Exhibition of Classical Art, c. Jan. 1927–?, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Myth and Legend in Classical Art, Feb. 28, 1987–Aug. 26, 1987, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Sculpture from the Classical Collection, Sept. 1, 1987–Aug. 31, 1988, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Human Figure in Greek and Roman Art: From the Permanent Collection, Part 2, Jan. 13, 1989–Feb. 21, 1990, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, What’s Greek about a Roman Copy?, Apr. 9–June 2, 2011, no cat.

Selected References

Helen Comstock, “Five Centuries of Greek Sculpture,” International Studio 84 (May–Aug. 1926), pp. 33–34 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “An Exhibition of Classical Art,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 21, 1 (Jan. 1927), pp. 9–10 (ill.).

Ralph Van Deman Magoffin and Emily Cleveland Davis, Magic Spades: The Romance of Archaeology (Holt, 1929), pp. 323 (ill.), 328.

Daniel Catton Rich, “A Late Greek Relief,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 23, 6 (Sept. 1929), cover (ill.), pp. 102–03.

A. D. Fraser, “The Sinking Warrior Relief,” in “General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America,” American Journal of Archaeology 31, 1 (Jan.–Mar. 1930), p. 58.

Hans Schrader, “[Bericht],” Vereinigung der Freunde Antiker Kunst in Berlin: Bericht über das XVIII und XIX Geschäftsjahr (Apr. 1, 1930–Mar. 31, 1932), p. 16.

Paul Jacobsthal, Die melischen Reliefs (Keller, 1931), p. 152.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Brief Illustrated Guide to the Collections (Art Institute of Chicago, 1935), p. 8 (ill.).

Hans Schrader, “Kopien nach dem Schildrelief,” in Corolla Ludwig Curtius zum sechzigsten Geburtstag dargebracht, ed. Heinrich Bulle (Kohlhammer, 1937), p. 87, pl. 20.2.

A. D. Fraser, “The ‘Capaneus’ Relief of the Villa Albani,” in “Thirty-Eighth General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America,” American Journal of Archaeology 41, 1 (Jan.–Mar. 1937), p. 109.

A. D. Fraser, “The ‘Capaneus’ Reliefs of the Villa Albani and the Art Institute of Chicago,” American Journal of Archaeology 43, 3 (July–Sept. 1939), pp. 447–57, fig. 2.

Vagn Häger Poulsen, “Die Verhüllte aus Hama und Einige Vermutungen,” Berytus: Archaeological Studies 6, 1 (1939–40), p. 13.

Frank Brommer, “Zu den Schildreliefs der Athena Parthenos des Phidias,” Marburger Winckelmann-Programm (1948), p. 18, n. 11.

Phoibus D. Stavropoullous, I aspis tis Athinas Parthenou tou Pheidiou (Archaiologika Etaireía, 1950), pp. 48–49, figs. 24–24a.

Giovanni Becatti, Problemi Fidiaci (Electa, 1951), p. 114, pl. 67, fig. 202.

Erwin Bielefeld, Amazonomachia: Beiträge zur Geschichte der Motivwanderung in der antiken Kunst (Neimeyer, 1951), p. 19.

Giulio Quirino Giglioli, Arte Greca: Arte Italico-Etrusca e Romana (Vallardi, 1955), pp. 407–08, fig. 338.

G. Hafner, “Anakreon und Xanthippos,” Jahrbuch des deutschen archäologischen Instituts (1956), pp. 7–8, fig. 4.

Dietrich von Bothmer, Amazons in Greek Art (Clarendon, 1957), p. 211, pl. 87, fig. 7.

Kristian Jeppesen, “Bild und Mythus an dem Parthenon,” Acta Archaeologica 34 (1963), p. 13, fig. 1s.

Barbara Schlorb, “Beitrage zur Schildamazonichie der Athena Parthenos,” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteiung 78 (1963), p. 168.

Adolf Furtwängler, Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture: A Series of Essays on the History of Art, 2nd ed. (Argonaut, 1964), pl. C, fig. C2; pl. F, fig. F1.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Sculptures in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” American Journal of Archaeology 68, 4 (Oct. 1964), p. 326.

Paolo Enrico Arias, Problemi di Scultura Greca (Pàtron, 1965), p. 377.

Evelyn B. Harrison, “The Composition of the Amazonomachy on the Shield of Athena Parthenos,” Hesperia 35, 2 (Apr.–June 1966), p. 115.

Volker Michael Strocka, Piräusreliefs und Parthenosschild: Versuch einer Wiederherstellung der Amazonomachie des Phidias (Wasmuth, 1967), pp. 69–71, cat. 13, fig. 27.

Neda Leipen, Athena Parthenos: A Reconstruction (Royal Ontario Museum, 1971), pp. 9, 45.

Theodosia Stephanidou, “Neoattika: hoi anaglyphoi pinakes apo to limani tou Peiraia” (PhD diss., University of Thessaloniki, 1979), pp. 15; 51, n. 5; 56, n. 3; 75, n. 3, 5–8; 76, n. 1–2; 78 n. 7; 109, pl. 42.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, Greek and Roman Sculpture in America: Masterpieces in Public Collections in the United States and Canada (University of California Press/J. Paul Getty Museum, 1981), pp. 21; 44, fig. 18, color pl. 4.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Calendar,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 75, 2 (Apr.–June 1981), p. 17 (ill.).

Evelyn B. Harrison, “Two Pheidian Heads: Nike and Amazon,” in The Eye of Greece: Studies in the Art of Athens, ed. Donna Kurtz and Brian Sparkes (Cambridge University Press, 1982), p. 58, pl. 16d.

Peter Bol, Forschungen zur Villa Albani: Katalog der antike Bildwerke, vol. 2 (Mann, 1990), pp. 106–07.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Roman Art,” in “Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 1 (1994), pp. 70–72, cat. 48 (ill.).

Karen Alexander, “The New Galleries of Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” Minerva 5, 3 (May–June 1994), p. 34, fig. 13.

Sally Vallongo, “Toledo Curator Gives Chicago a Hand with Its Old Treasures,” Toledo Blade, Aug. 17, 1994, p. P-1 (ill.).

Evelyn B. Harrison, “Pheidias,” in Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture, ed. Olga Palagia and J. J. Pollitt (Cambridge University Press, 1996), cover; fig. 14.

Claire Cullen Davison, Pheidias: The Sculptures and Ancient Sources, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, Supplement 105 (Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Studies, 2009), vol. 1, pp. 244–45, cat. 131; vol. 3, p. 1306, sec. 6, fig 56.

Antonio Blanco Freijeiro, Arte griego, 3rd ed. (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2011), p. 270, fig. 126.

Karen B. Alexander, “From Plaster to Stone: Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Karen Manchester (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 29.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

Visible Light

Normal-light and raking-light overalls: Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens

Normal-light and raking-light macrophotography: Nikon D5000 with an AF Micro NIKKOR 60 mm 1:2.8 D lens

Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens and a Kodak Wratten 2E filter

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

High-Resolution Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Canon EOS1D with a PECA 918 lens and a B+W 420 (2E) filter pack. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Visible-light microscopy: Zeiss OPMI-6 stereomicroscope fitted with a Nikon D5000 camera body

Petrographic and thin-section analysis: Leitz DMRXP polarizing microscope equipped with a Leica Wild MPS-52 camera head

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry

Finnigan MAT 5000 mass spectrometer

X-Ray Diffraction

PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with vertical goniometer (CuKα/Ni at 40 kV, 20 mA)