Cat. 9

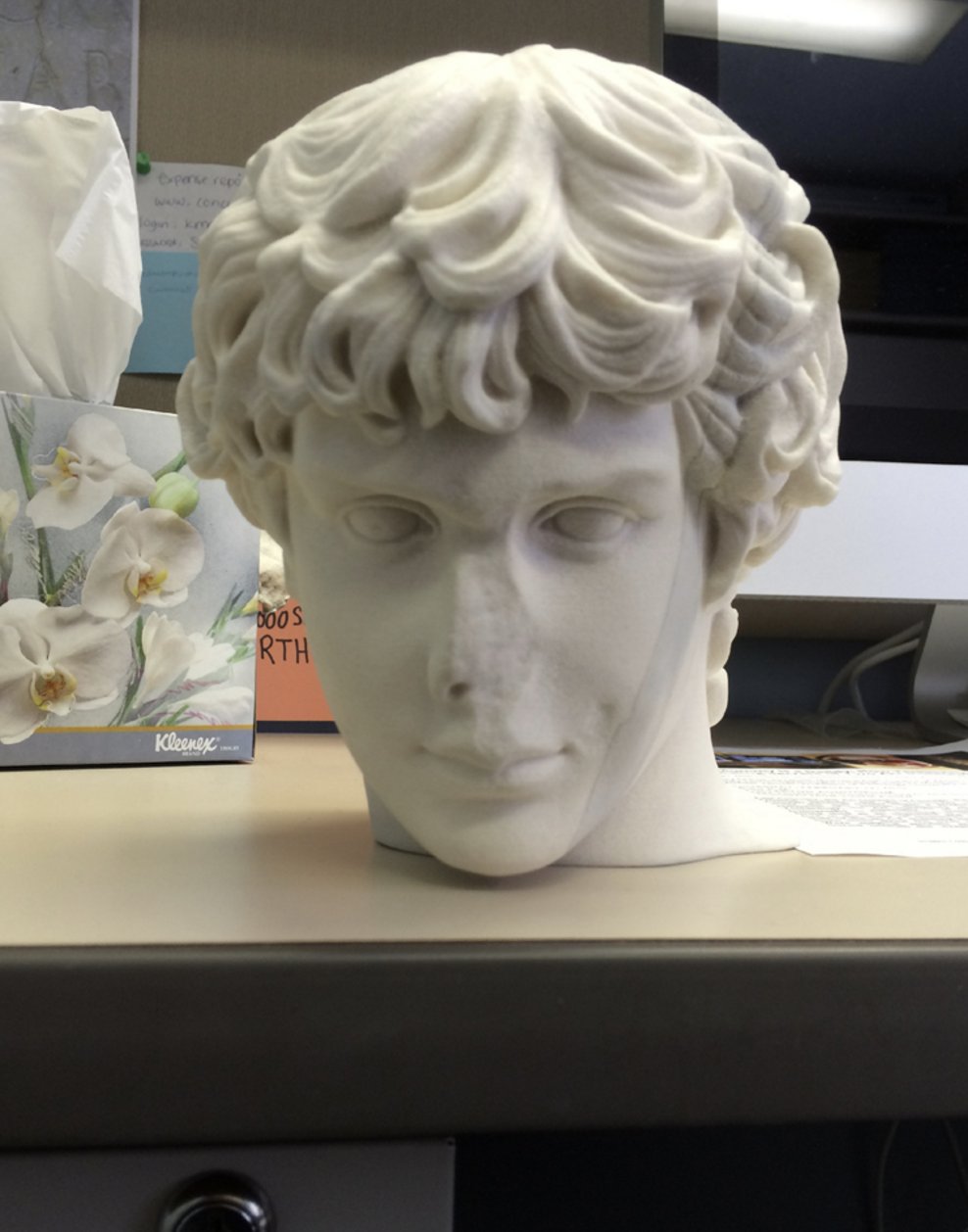

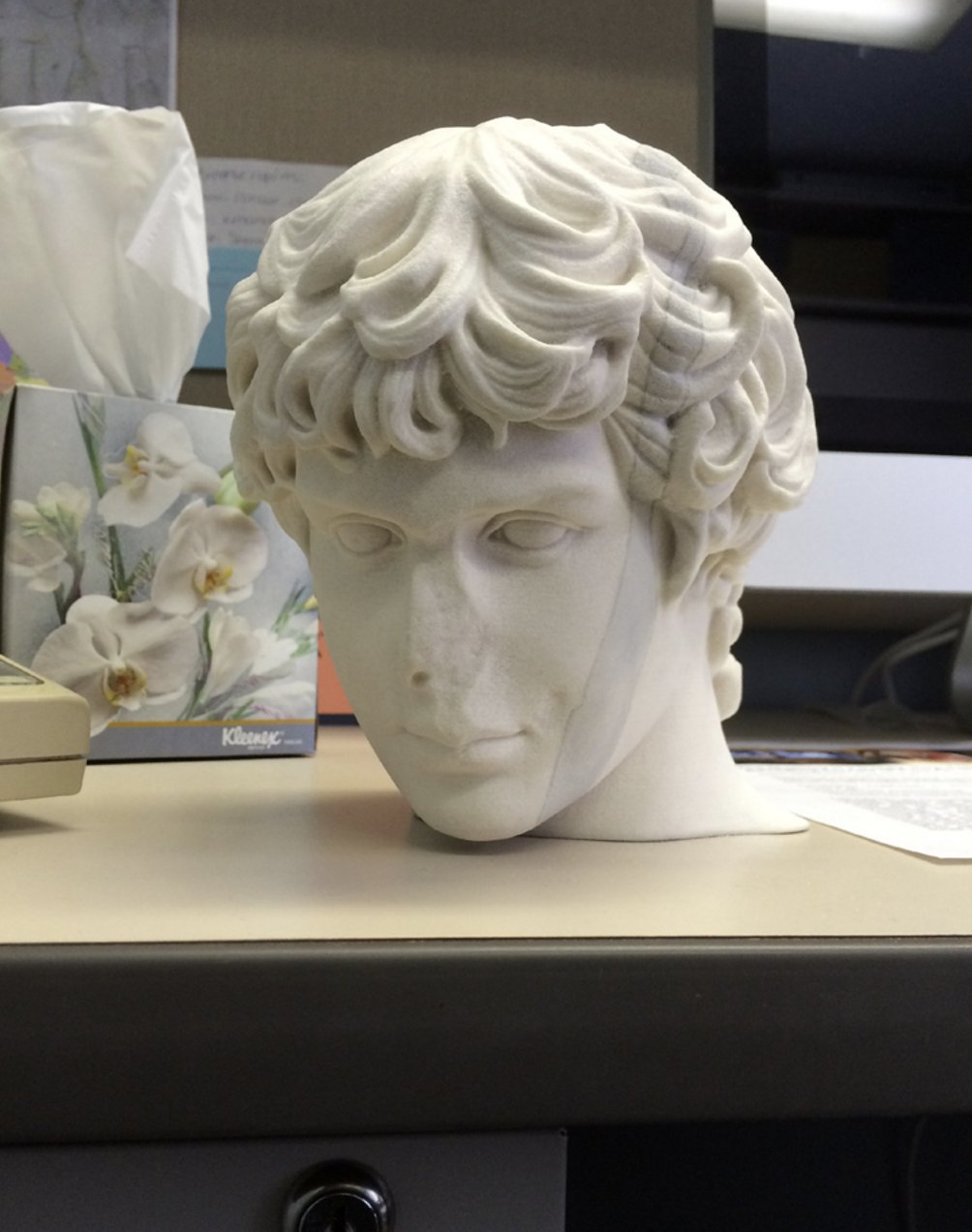

Fragment of a Portrait Head of Antinous

Mid-2nd century A.D.

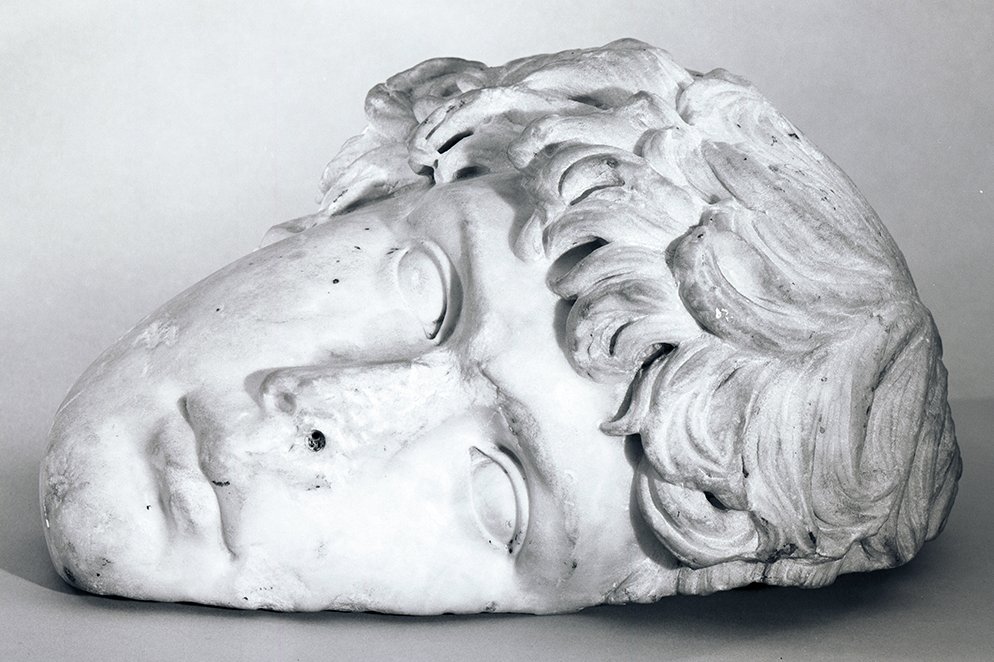

Marble; 31.7 × 31 × 17 cm (12 1/2 × 12 × 6 1/2 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mrs. Charles L. Hutchinson, 1924.979

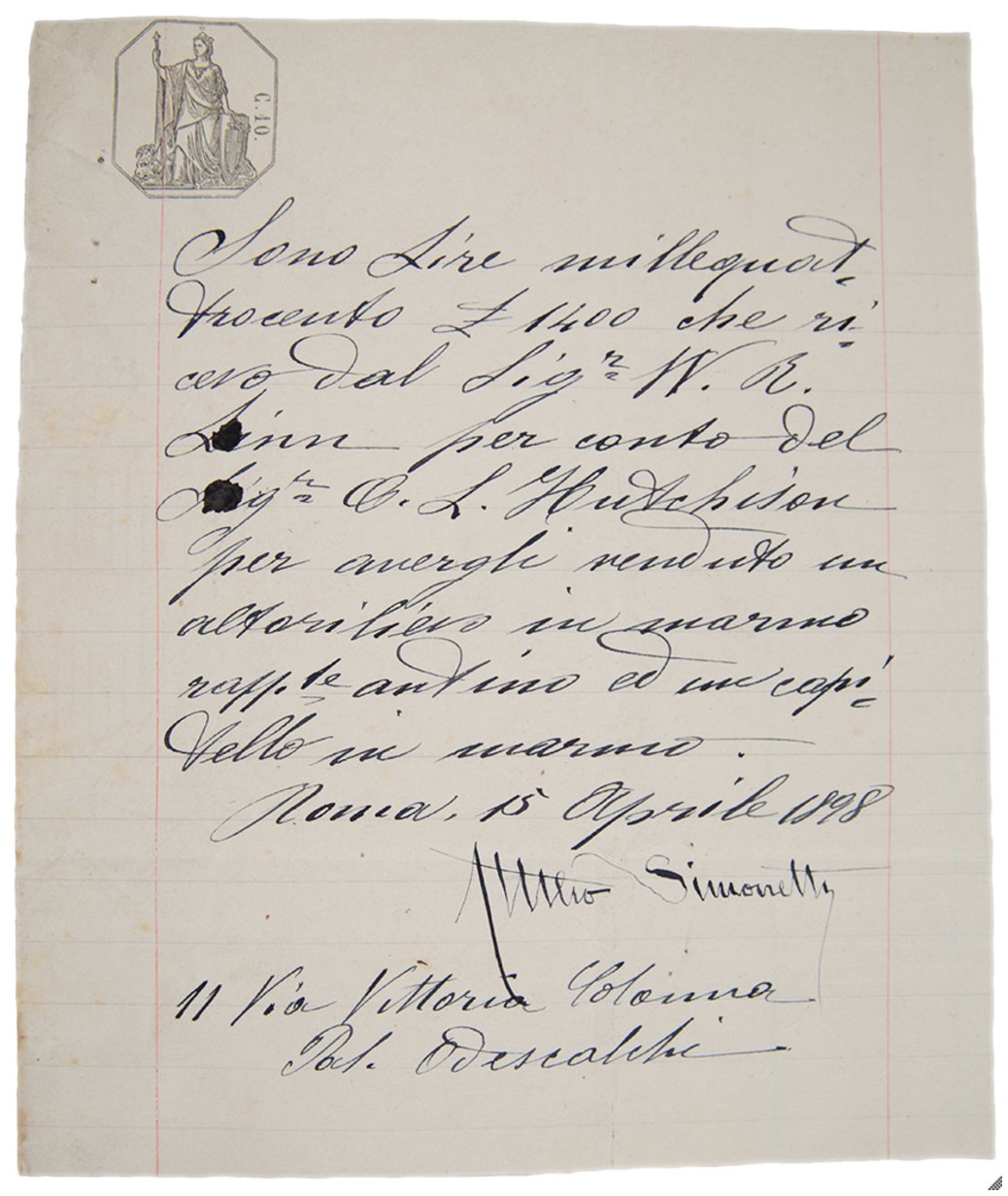

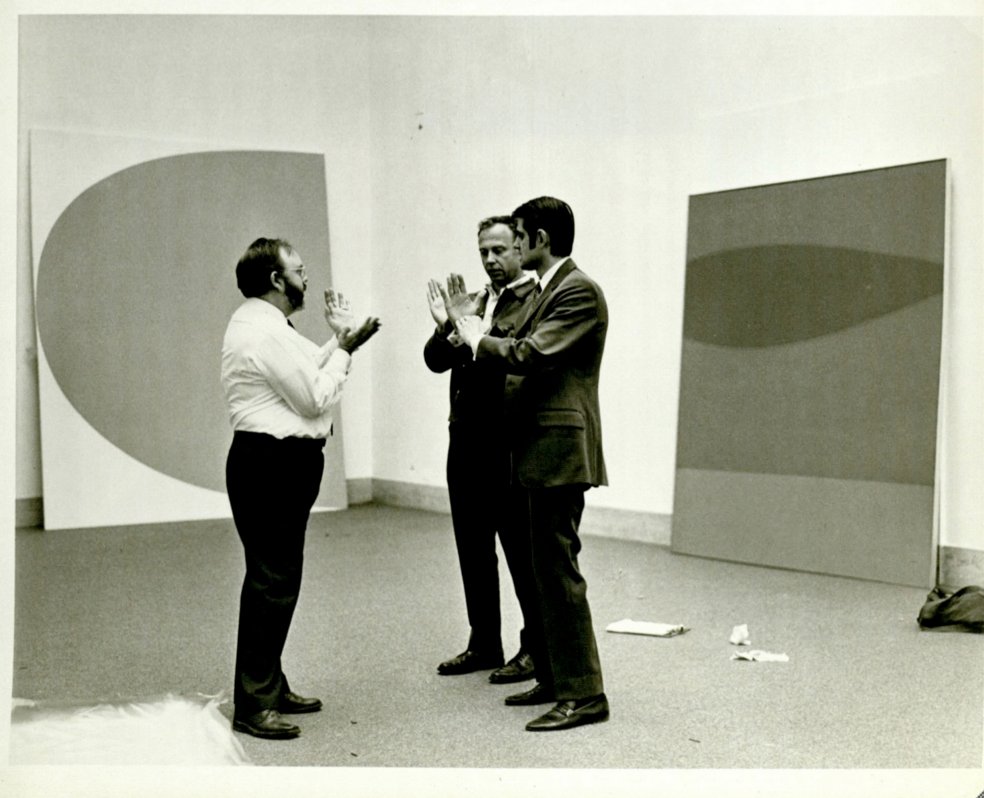

During his annual trips to Europe, Charles L. Hutchinson, the Art Institute of Chicago’s first and longest-serving president, regularly visited commercial galleries and dealers, always on the lookout for artworks (fig. 9.1). As one of the nascent museum’s most generous benefactors, he at times purchased pieces for its collection and either provided or raised funds for other acquisitions. While in Rome in April 1898 he stopped by the Palazzo Odescalchi to see the artist and antiquarian Attilio Simonetti; it was there that he bought this fragment of a portrait of Antinous, which, unusually, he kept for himself in his Prairie Avenue home for nearly twenty-five years.

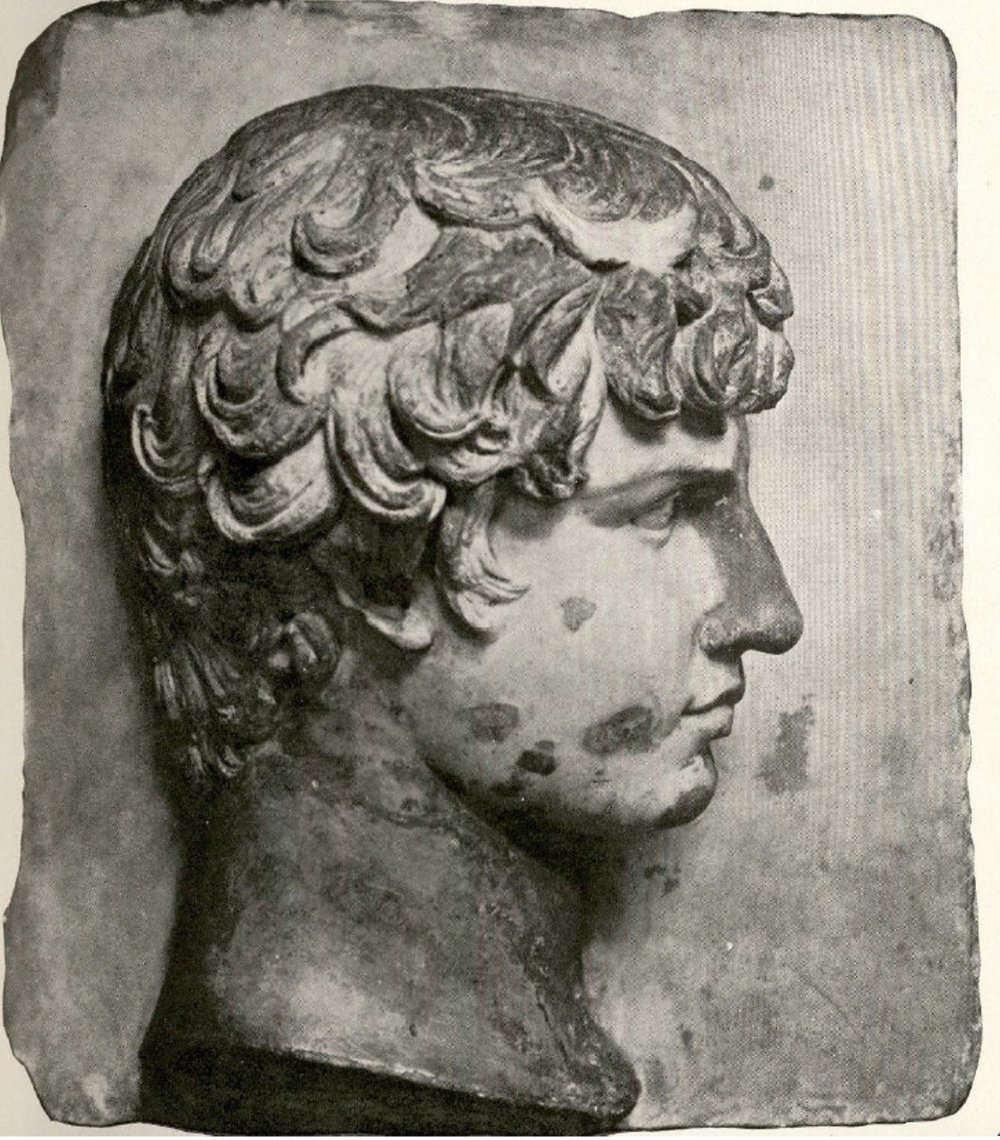

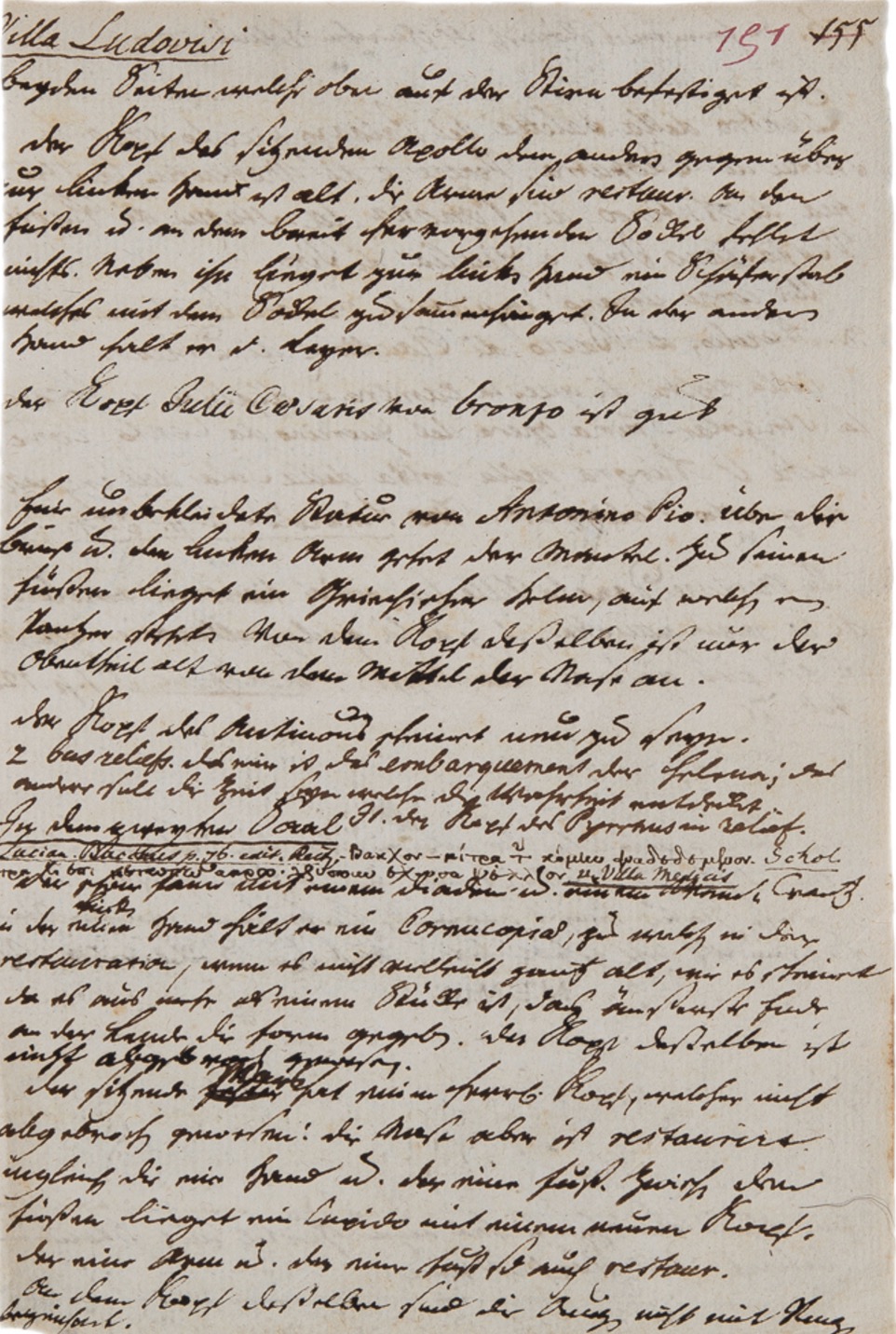

In December 1913 Art Institute curator Frank B. Tarbell published an article about the portrait in Art in America. The accompanying photograph depicts the youth’s head in right profile against a marble plaque with an irregular left edge (fig. 9.2). Its nose and neck are discolored restorations. Whereas Simonetti described the sculpture as a relief on the sales receipt (fig. 9.3), Tarbell insisted it was a fragment from a statue or bust carved in the round, identifying the plaster restorations that camouflaged its true form. He also explained that typologically the piece belonged to a group of portraits distinguished by a common hairstyle. In time he was shown to be right on both counts. Nevertheless, the portrait masqueraded as a relief when it was lent to the museum in 1922 and did so five or so years later, when it was photographed for the Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago following its donation by Hutchinson’s widow.

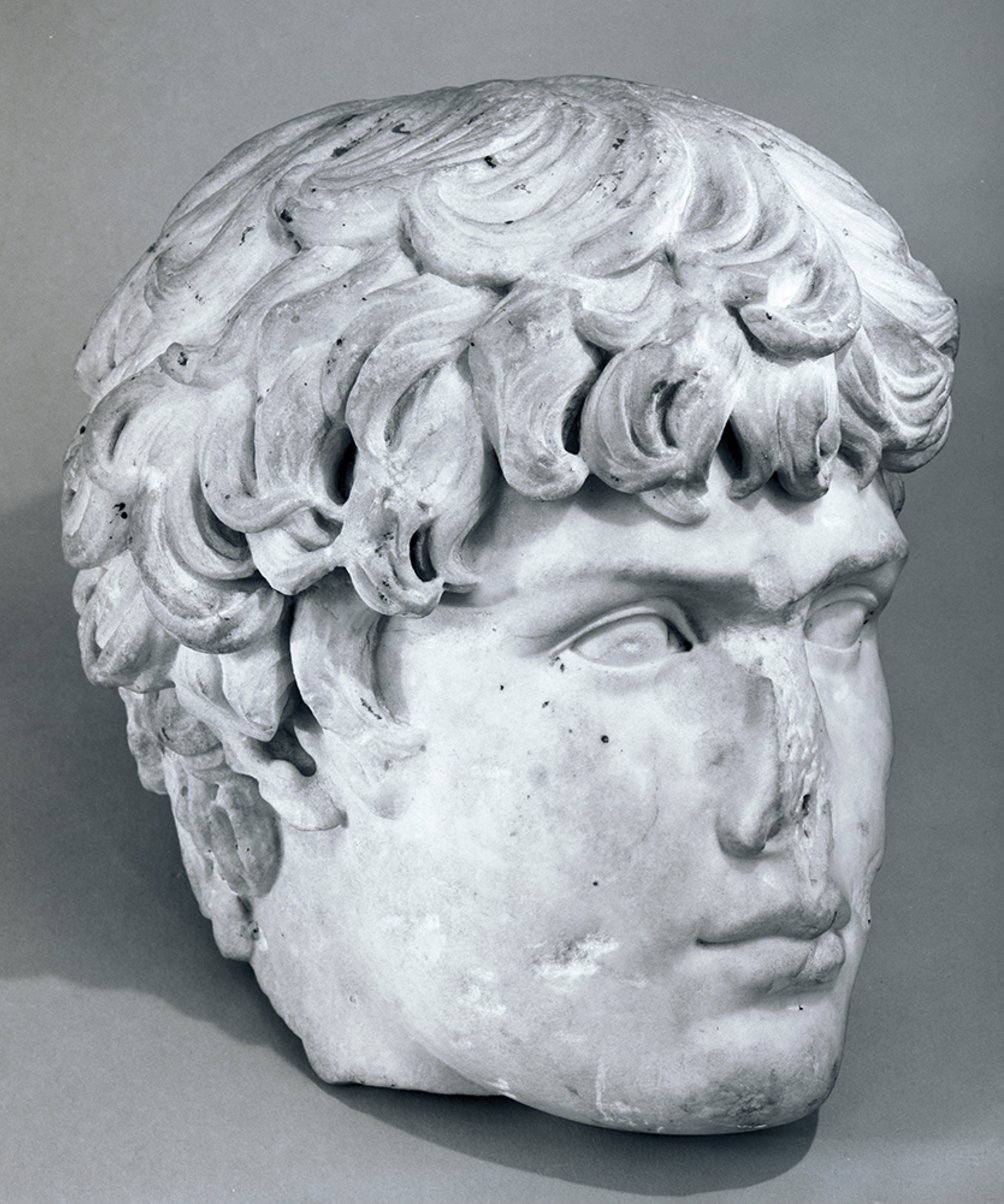

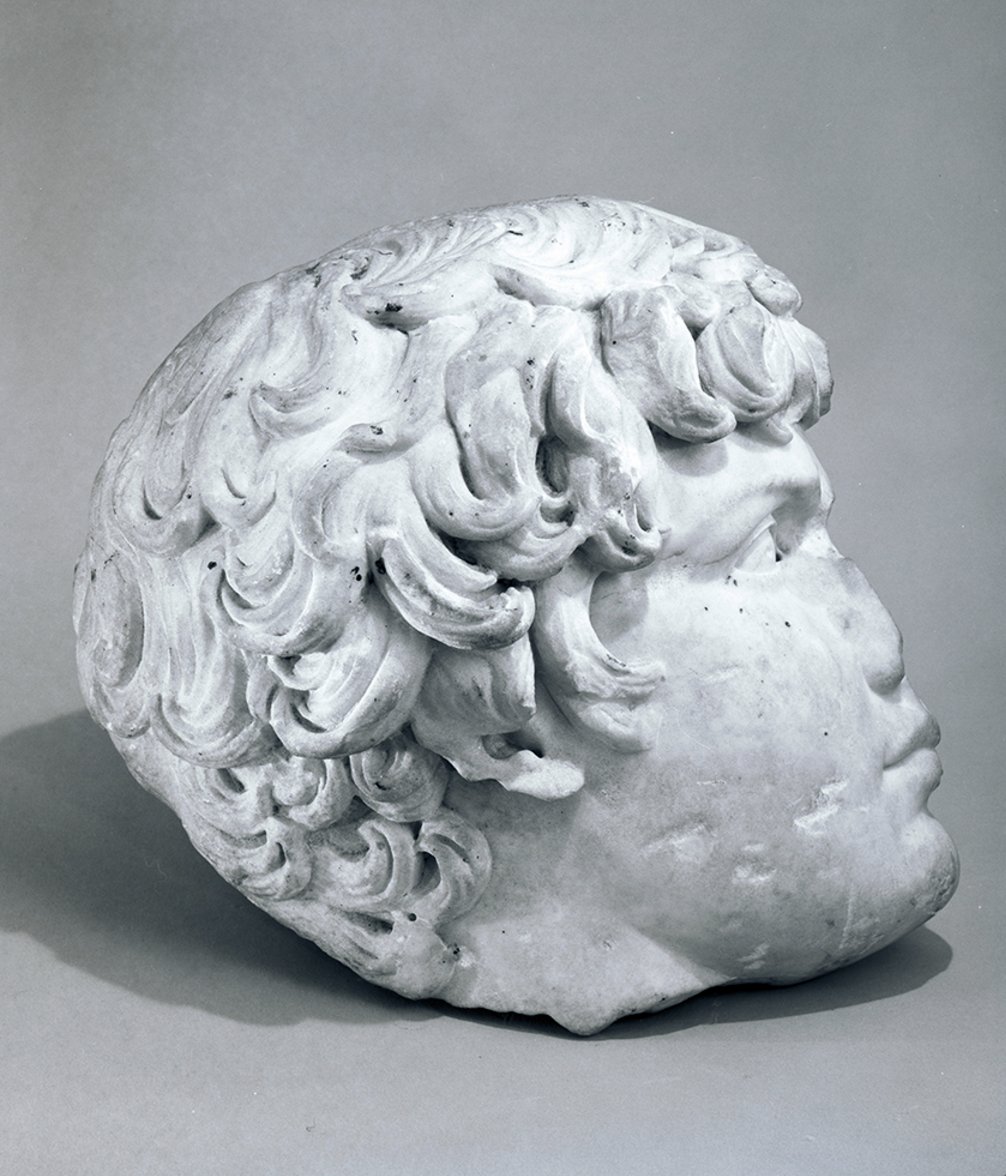

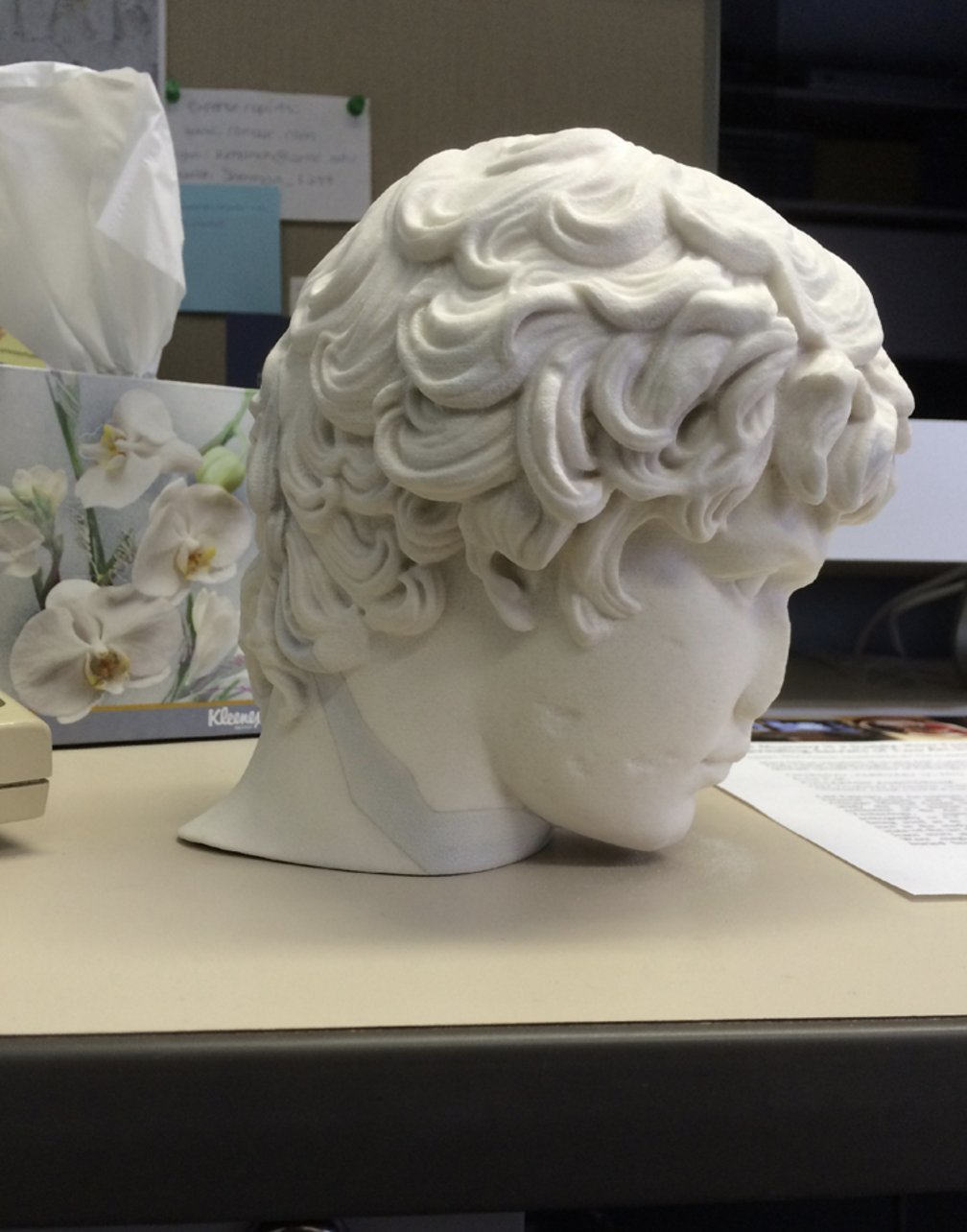

The restorations were gone by the early 1960s, however, as photographs of the portrait from this period show (fig. 9.4, fig. 9.5, and fig. 9.6). They show the extent, degree of preservation, and general condition of the ancient fragment. It is broken along a diagonal line extending from Antinous’s left jaw through the cheek, past the outer edge of the eye socket, and into the curls above the missing left ear. Its nose and neck are also gone, but most of the hair on the top, back, and right side of the head is preserved.

Although Simonetti’s claim that the Chicago portrait came from a relief was wrong—perhaps deceptively so—his identification of the subject was correct. Without a doubt, the person portrayed is Antinous (c. A.D. 111–30), the comely young companion of Emperor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–38), who drowned in the Nile River during an imperial tour of Egypt. In his grief Hadrian founded the city of Antinoupolis near the site of the youth’s death, elevated his status from human to divine, and mandated religious rites in his honor. But in creating hundreds, if not thousands, of portraits of Antinous, people all across the empire unwittingly ensured his immortality. In fact, so many of these images were rendered in paint, struck on coins, carved from stone, and cast in bronze that today Antinous is one of the most instantly recognizable individuals from antiquity.

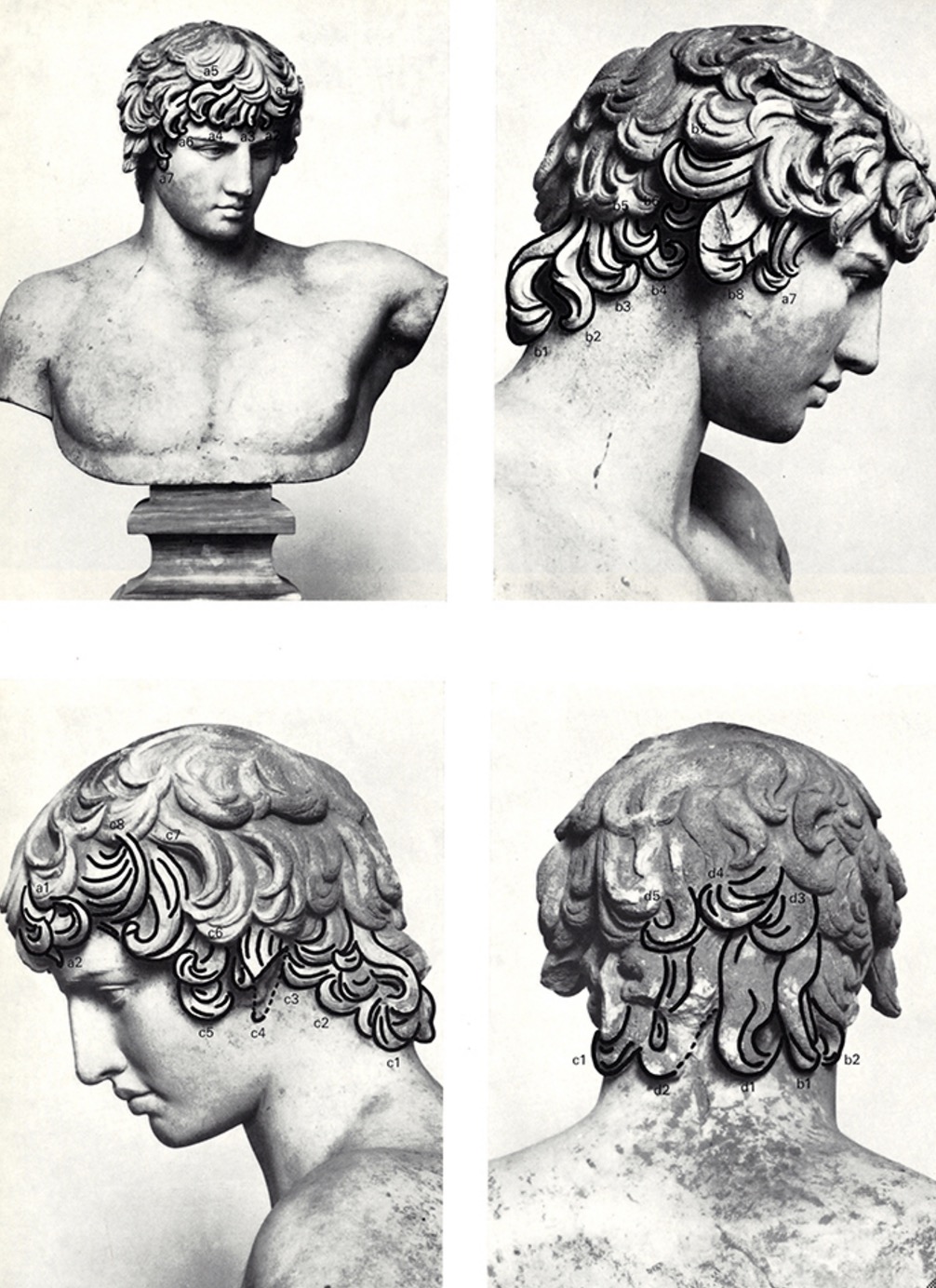

Currently about one hundred sculpted statues, busts, reliefs, and disembodied portraits of Antinous from across the Roman Empire survive in varying states of preservation. The classicizing versions of full-length statues and portrait busts depict the sensual young Bithynian in the prime of his youth, with an unusually broad chest. This example, like others of its type, shows Antinous with an oval face; smooth complexion; striated brows above unarticulated, deep-set eyes with thick lower lids; an aquiline nose (although here missing); and full lips. However, the most important feature of Antinous’s main portrait type is the hairstyle, and as Tarbell so perceptively recognized a century ago from the arrangement of Antinous’s hair, the Art Institute’s fragment came from a portrait bust of this main type. The thick curls cascading from the crown of the head over the ears and down the neck are uniformly arranged according to a fixed scheme, and the locks directly above his left eye are positioned in one of two known variations of his primary hairstyle.

Indeed, an over-life-size but faceless bust was restored with a portrait of Antinous solely on the basis of a few remaining locks of its ancient hairstyle. Currently this intriguing sculpture is displayed in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps in Rome (fig. 9.7, fig. 9.8, fig. 9.9, and fig. 9.10). Antinous’s pose is familiar: he gazes down, his head turned in the direction of his raised left shoulder. In addition to the surviving locks of hair on the back and left side of the head, other ancient parts of the sculpture include the neck and upper body, the latter once broken, its left edge now restored. Presumably the socle and the new face were added at the same time. While examining the Altemps bust, Egyptologist W. Raymond Johnson noticed that the angle of the join of the restored face was similar to the break on the Chicago portrait, and he brought his observation to the attention of the Art Institute.

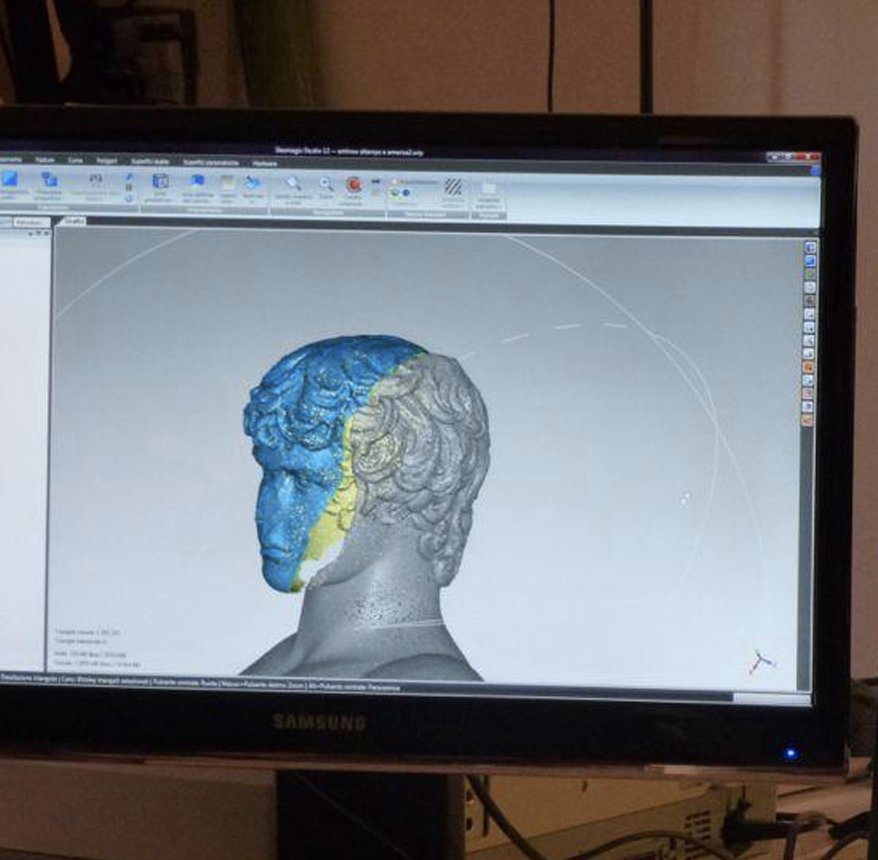

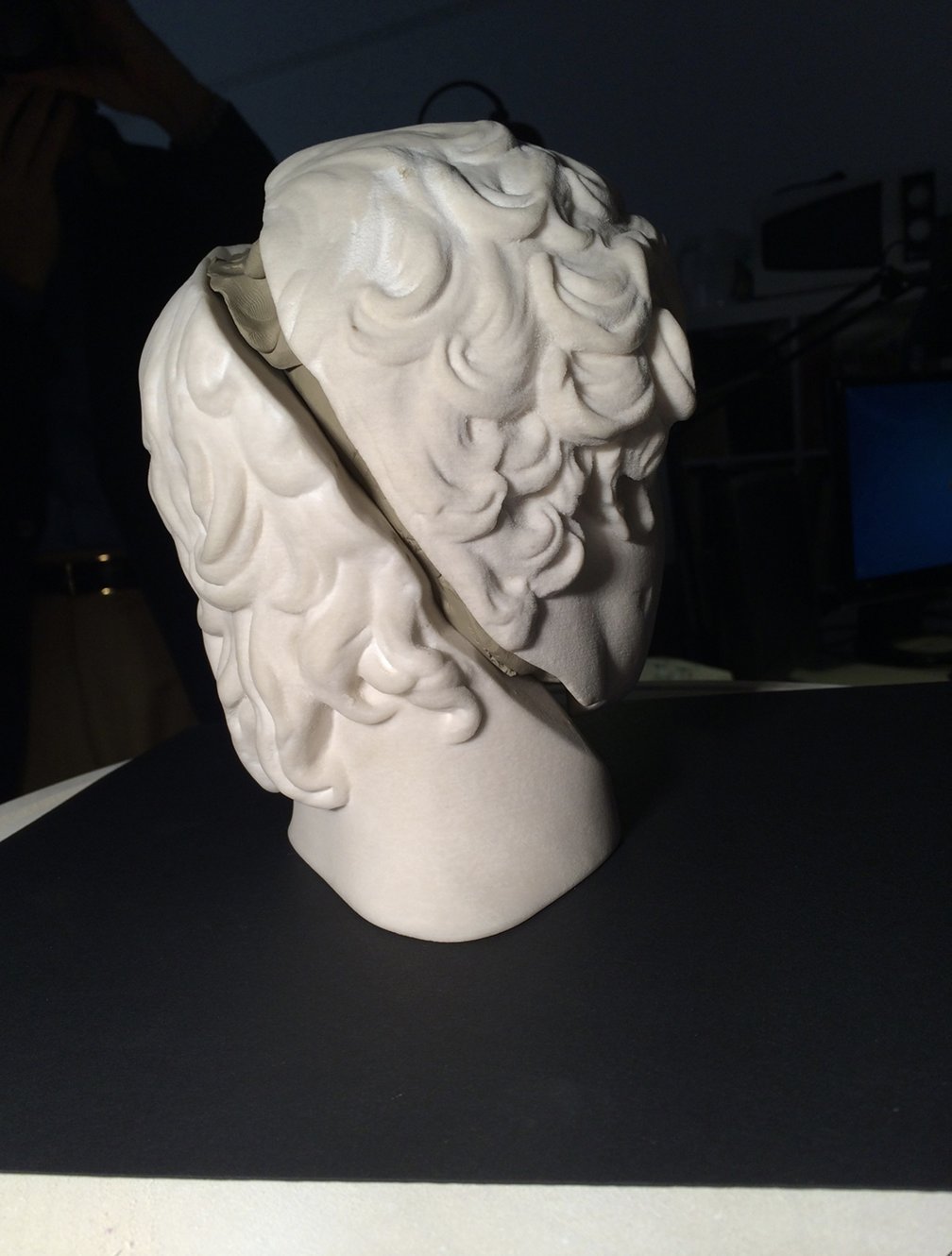

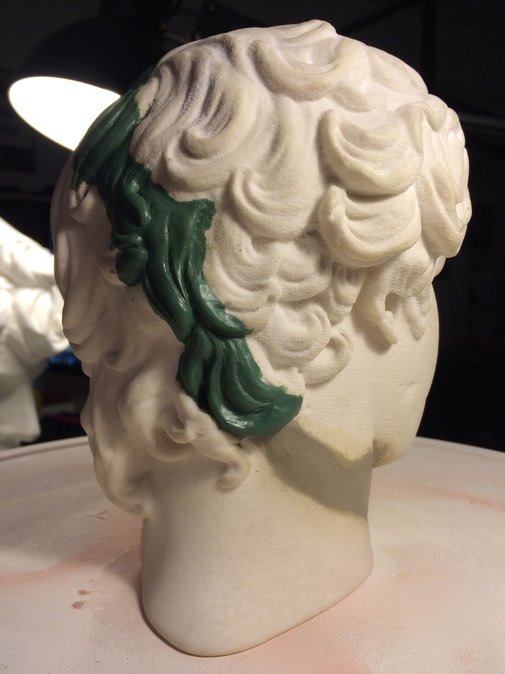

At the suggestion of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s senior conservator of antiquities, Jerry Podany, a cast of the Chicago portrait was made for comparison with the Altemps bust, which Podany subsequently organized with the Roman museum’s director, Alessandra Capodiferro. Placed side by side, the two pieces were remarkably similar in scale and general appearance (fig. 9.11). Thereafter three-dimensional measurements of the surviving ancient bust and cast were taken, and the early modern head was digitally removed along the presumed line of the join and replaced with an image of the Chicago portrait (fig. 9.12). Despite losses to the left jaw, the two pieces appeared to belong together. A three-dimensional one-third-scale model was made of both parts of the ancient head. Once aligned, the gap between the head and the face was filled with modeling clay (fig. 9.13 and fig. 9.14), and the lost sections of hair were carved using Christoph Clairmont’s diagram of Antinous’s curls as a guide (fig. 9.15 and fig. 9.16). Three-dimensional measurements were then taken of the new model, and the complete head was printed with the areas of loss clearly indicated (fig. 9.17, fig. 9.18, and fig. 9.19). A full-scale model of the bust incorporating the Chicago portrait was cast in plaster to re-create the appearance of the original second-century bust (fig. 9.20).

Also on Podany’s advice, samples of stone were extracted from the Chicago portrait and the Altemps bust for isotopic and petrographic analysis. Tests performed by the Laboratorio di Analisi dei Materiali Antichi in Venice, Italy, revealed that both pieces were carved from Carrara marble and are sufficiently similar that they could have come from the same block of stone. Based on the reconstructed model of the sculpture and the scientific assessment of its stone, it is all but certain that the Chicago fragment was once the face of the Altemps bust. Although it has taken a decade to test Johnson’s hypothesis, preparations are under way at this writing for an exhibition devoted to his important discovery.

The association of the Chicago portrait with the Altemps bust opened new avenues of exploration about the sculpture’s past. The latter once belonged to the Boncompagni Ludovisi family, keepers of perhaps the most prestigious collection of ancient sculptures in Rome. Begun in the early seventeenth century by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, it comprised purchases, gifts, and discoveries unearthed during the construction of his immense estate between the Pincian and Salarian Gates along the northwestern perimeter of the city. In antiquity this land belonged to the statesman and historian Sallust; either he or his son transformed it into a luxurious country retreat. In the following century these gardens passed into the hands of Emperor Tiberius and became a beautiful public park embellished with scores of fine sculptures, some of which ultimately formed the core of the Ludovisi collection.

The marriage in 1681 of Gregorio II Boncompagni, Duke of Sora, and Ippolita Ludovisi, Princess of Piombino, consolidated the resources of these two immensely wealthy clans, and the Boncompagni Ludovisi dynasty prospered for the next two centuries. However, in the decades following 1870, when Rome became the capital of Italy, the family’s fortunes took a turn for the worse; their celebrated estate was dismantled, and their land was sold off to become an elite residential quarter. In 1901 the Italian government purchased 104 sculptures from the Ludovisi collection. Included among these pieces, which were relocated to the Baths of Diocletian, was the bust of Antinous.

Since 1997 the bust has been displayed with other Boncompagni Ludovisi treasures in the renovated Palazzo Altemps. In her 2011 catalog of the museum’s sculpture holdings, Matilde De Angelis d’Ossat wrote that it is known to have been in the Boncompagni Ludovisi collection only as far back as 1794, presumably on the basis of its appearance in an edition of Giuseppe Vasi’s guidebook of the same year. However, Vasi’s earlier 1786 French edition of this guide likewise lists this piece, while Pietro Rossini’s book of 1693 also appears to refer to it. Rossini lists the subject as “Antino,” which may be an early modern spelling, a scribe’s error, or an indication that he was unfamiliar with Antinous. Rossini’s and Vasi’s references are scant and imprecise, but together they strongly suggest that a bust of Antinous, arguably the Altemps piece, was in the family’s possession as early as the late seventeenth century.

Possibly the most compelling evidence for believing that the sculpture described by Rossini and Vasi is the Altemps bust, however, is provided by no less an authority than Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Following his 1756 examination of the bust of Antinous at the Villa Ludovisi, he recorded two comments (fig. 9.21). The first emphatically asserts that the statue and the back of its head are old but the (rest of the) head is new, while the second states that the head appears to be new. In light of this description, there can be little doubt that he saw the Altemps bust in its present form. Despite—or perhaps because of—its restored face, the piece continued to be considered noteworthy and to be commented upon, both by editors of Winckelmann’s collected works and also more broadly. The earliest known photograph of the curious hybrid was taken around 1890 (fig. 9.22).

There is no mention in the literature reviewed so far of documents pertaining to the Ludovisi family’s acquisition of a bust of Antinous, but inventories of estate holdings made between the seventeenth and the late nineteenth centuries reference what is surely the Altemps piece. In fact, when examining a transcription of the 1641 inventory, Elizabeth Hahn Benge noticed a sculpture described as a larger-than-life-size head and chest of “Antonio” located in the Palazzo Grande and wondered it if might refer to the Altemps bust. Benge also observed that Rossini’s and Vasi’s accounts supported her contention, since the busts they mentioned were displayed in the first room of the palace; because the collections were relatively immobile, the tour books repeat the same order. Another reason to think that the sculpture cited in the 1641 inventory is the Altemps piece is the absence of any additional busts of Antinous—misspellings aside—in the inventories of and guides to the Villa Ludovisi. Further, like the recorder of the 1641 inventory, later authors noted the sculpture’s heroic rather than human scale.

If, as seems likely, Benge is right, one wonders whether Ludovico Ludovisi purchased the bust or otherwise obtained it from an earlier collection. Alas, the surviving records contain only vague descriptions. For example, the list of 120 artworks acquired from the famed Cesi collection only notes “twenty statues with five torsos and fifty minor fragments of statues, fifty-one heads and busts, thirty reliefs,” and so on. The inventory made at the time of the cardinal’s death is equally imprecise.

If not acquired by purchase or gift, was the bust found in fragments on the grounds of the estate during construction? It is tempting to wonder if the sculpture was knocked over by the Visigothic troops of Alaric I when they entered Rome through the Salarian Gate and sacked the city in A.D. 410, leaving its parts to lie scattered around the imperial gardens for centuries until they were recovered and reassembled. Had that been the case, however, the Chicago portrait would surely have been reattached to the Altemps bust then, too. Or was the head buried in the vicinity of the other fragments but missed by the excavators? Had it been discovered earlier and carted off elsewhere? Answers to these questions may never be known, but it should be noted here that most portraits of Antinous discovered in Rome and its environs were found in private rather than public settings.

Also unknown, at least for the time being, is when the ancient fragments of the Altemps bust were reassembled and who carved its early modern face. Despite considerable liberties taken with the arrangement of the locks above the youth’s forehead, it seems that the restorer was familiar with the pose, facial features, and disposition of other portraits of Antinous. Caroline Vout alluded to a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century date for the face, and Hugo Meyer suggested that Ippolito Buzzi, one of several restorers employed by Cardinal Ludovisi, may have created it. It is worth recalling that when Winckelmann saw the bust in 1756, well over a century after Buzzi’s death, he observed that the head was new. But in describing the face thus, was he simply remarking that it was not original to the ancient sculpture, or was he implying that it had been made in very recent times? This is another question without an answer.

Although an early modern history for the Altemps bust can be constructed with some confidence, all attempts to track a trajectory for the Chicago portrait have been unsuccessful. More than a century after Hutchinson purchased the head from Simonetti, the business is still in his family’s hands, although it now sells Asian rather than ancient art and operates under a different name on Rome’s prestigious Via Margutta. A search of its records, which are substantially incomplete, turned up a client book containing Hutchinson’s name and address. However, there were no documents indicating how the dealer came to have the portrait or who converted it from a fragment of sculpture in the round to a faux relief by attaching it to a plaque, restoring the nose and neck, and covering the losses with plaster.

Meanwhile, scientific analysis revealed that surface deposits on the back of the Chicago portrait “appear to be from a preindustrial cement such as the Romans used,” suggesting the likelihood that the Chicago portrait was separated from the Altemps bust in antiquity and lay in the earth near an ancient construction site. Since Hutchinson purchased the piece in Rome, there is good reason to think that it remained in the city from the time the original sculpture was fashioned in the mid-second century until he shipped the portrait to Chicago in 1898.

In America, the piece has led an adventurous life. On January 24, 1983, Kitty Hannaford, a research assistant for classical art at the Art Institute of Chicago, spoke twice by telephone with an unidentified male caller who reported that he knew the location of the museum’s “portrait of young man whose name began with A who accompanied the Roman emperor to Egypt,” which he also said “had been stolen by a night watchman” in the early 1960s, and he wanted to know if there was a reward for its return. Recalling a registration card for a portrait of Antinous, Hannaford found the department’s object file and discovered that next to the label “Antinous 1924.979” was a handwritten note reading, “Sculpture—where?” As there were no galleries of ancient art at the time, Hannaford searched the storage area the following morning. Unable to locate the portrait, she then took the issue to museum registrar Wallace Bradway, whose files also indicated that the whereabouts of the piece were unknown. A similar notation, “where,” in the hand of Bradway’s predecessor, who left in 1965, clearly indicates that the portrait’s disappearance was noted by the mid-1960s at the latest. Hannaford handed the matter over to Louise Berge, the Art Institute’s associate curator of classical art. She made contact with the mysterious caller, who subsequently identified himself as Jim Moran. He informed her that the portrait of Antinous was with Henry Geldzahler in New York.

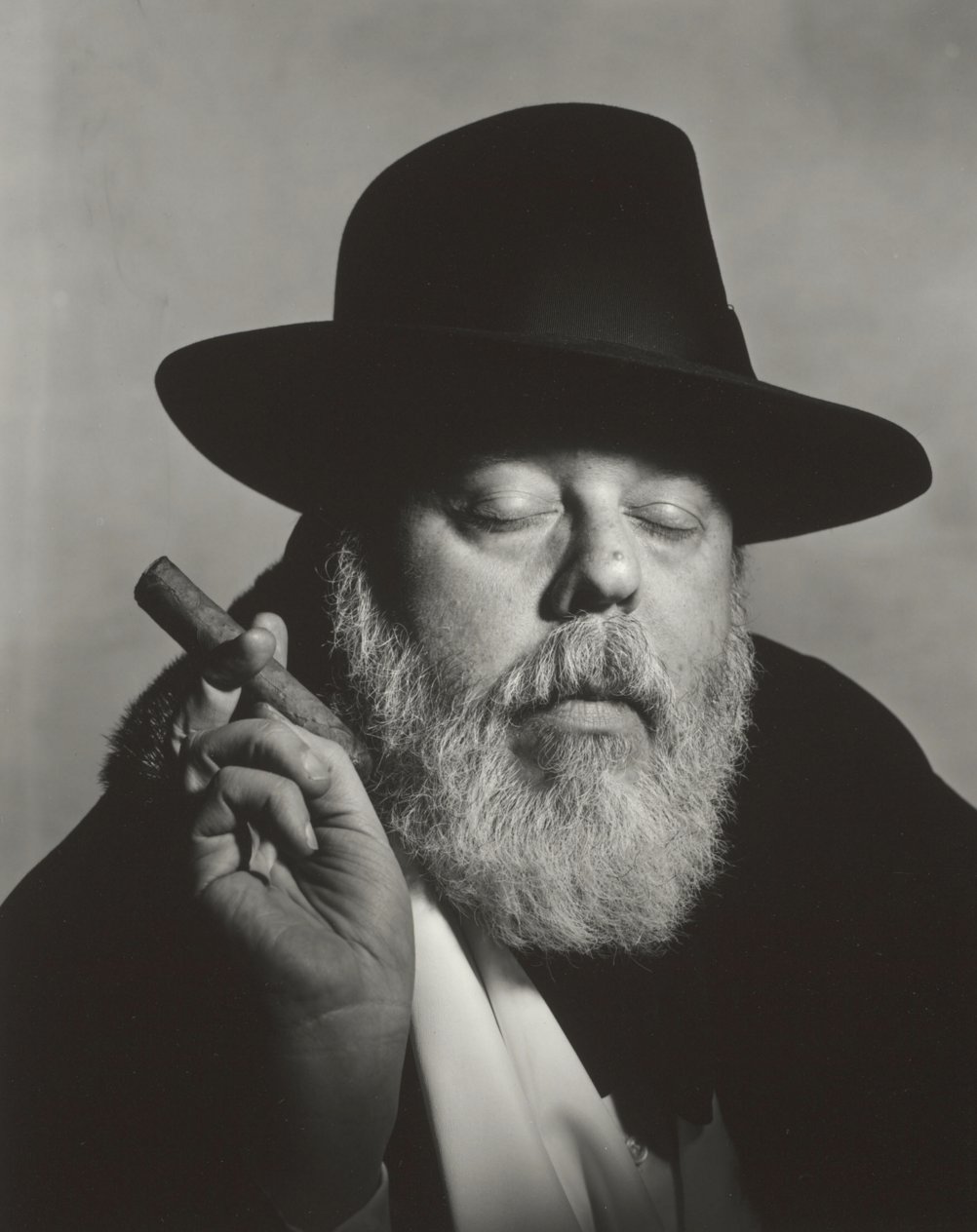

A highly influential personality on the American art scene from 1960 until his death in 1994, Geldzahler (fig. 9.23) was by 1983 a renowned art historian, critic, and public official who had become the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s first curator of contemporary arts by 1967. He was also the first director of the visual arts program at the National Endowment for the Arts, the U.S. commissioner for art at the Venice Biennale in 1966 and 1986, curator of the landmark 1969 exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970, and commissioner of cultural affairs for New York City. Closely involved with a number of artists in the 1960s, among them David Hockney, Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, Geldzahler will forever be inextricably linked with—if not partly responsible for—the ascendancy of Pop Art and Color Field painting on the New York cultural scene.

In a telephone call on February 3, 1983, Geldzahler provided Berge with several salient details: the portrait was given to him in Chicago; it had been in his possession for “some twenty years”; he undertook research that revealed it belonged to the Art Institute; and when he informed the museum in writing of its current whereabouts, “we wrote back that it was not ours.” He then consulted with Metropolitan Museum of Art director James Rorimer, and “it was decided that he hang on to the piece.”

Berge recounted what she learned to the Art Institute’s director, James N. Wood, who had worked under Geldzahler during his tenure at the Metropolitan (fig. 9.24). On February 4, 1983, Wood telephoned his former supervisor, and additional details appear in the notes he took during their conversation. Geldzahler reported that he received the piece from a Chicago artist whose “friend was a night guard at A.I.C.” He brought the portrait to the attention of Dietrich von Bothmer, curator of Greek and Roman art at the Metropolitan, and Peter von Blanckenhagen, professor of classical art history at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, who discovered that it had been published in the Art Institute’s annual report. Geldzahler recapped his earlier discussion with Berge, repeating that when he informed the Art Institute that he had the portrait in his possession, he was told “they had no department and it wasn’t theirs.” He also recalled his long-ago conversation with Rorimer, who advised him not to worry about the matter any further.

Geldzahler subsequently supplied Wood with photocopies of a letter dated March 2, 1961, that he addressed to John Maxon, the Art Institute’s director of fine arts, as well as three photographs of the piece. Arrangements were made for the portrait’s return; Berge and Bob Combs, assistant director of protection services, were dispatched to New York to retrieve it from Geldzahler’s home. While the portrait was being packed into a crate, Combs recalls, Geldzahler commented about how much he had enjoyed having the portrait over the years and how he had wondered when the Art Institute would take it back. The museum issued a receipt for its return on March 2, 1983, twenty-two years to the day after Geldzahler’s letter to Maxon.

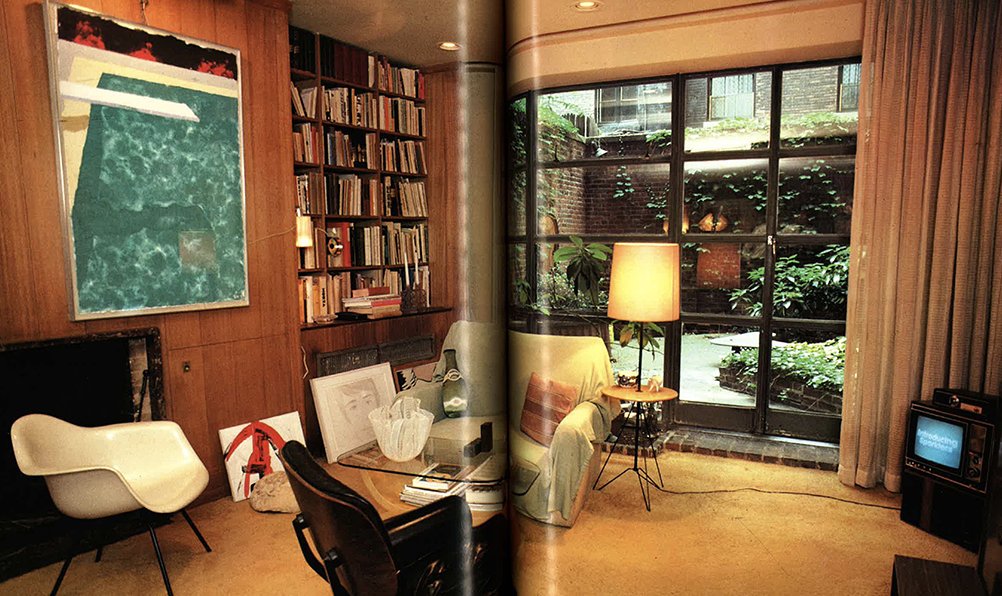

During the course of his career, Geldzahler received a number of artworks as gifts from painters and sculptors, and he displayed the portrait of Antinous alongside various pieces. A close friend, the writer and small press publisher Raymond Foye, recalled, “Henry kept the sculpture on the floor, on the carpet—next to a Warhol Brillo box, a Keith Haring vase, etc.” He also remembered that it attracted the attention of the artist Cy Twombly: “When he saw the head he picked it up and stroked the cheek—it was incredibly sensual.” An article about Geldzahler’s collection published in 1983 features an illustration showing the Chicago portrait in front of a version of Hammer and Sickle by Andy Warhol and below a painting of a swimming pool by David Hockney (fig. 9.25).

In a later letter to Geldzahler, Wood reported, “Antinous now graces the corner of my office . . . and inspires a sense of déjà vu you would appreciate.” Is this an allusion on Wood’s part to the fact that he had seen the portrait while it was in Geldzahler’s possession but did not know or recall that it belonged to a museum that he would direct for nearly twenty-five years?

The Fragment of a Portrait Head of Antinous is now displayed in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art alongside the museum’s Portrait Head of Emperor Hadrian (fig. 9.26; see cat. 6). In declaring Antinous a god and establishing religious rites and games in his honor, Hadrian took steps to secure his young companion’s immortality. Although the ancient cult of Antinous waned during the Middle Ages, he was never completely forgotten. Along with the reawakening of interest in antiquity in the early modern period came a renewed fascination with the youth that continues to this day. For example, on December 7, 2010, Lorne Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon bought a portrait bust of Antinous at auction for $23,800,000. More recently, a long-missing portrait bust of the youth in the guise of Osiris was purchased privately for an undisclosed amount. Furthermore, the dawn of the twenty-first century saw the emergence—on the Internet—of a new form of reverential worship of Antinous that glorifies the emperor’s young lover as a living god. The motto of the Ecclesia Antinoi is “Ave Vive Antinoe,” or “Hail, may you live Antinous!”

Karen Manchester

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Academic research and technical investigations carried out on this object have yielded a curatorial triumph: the portrait fragment is in all likelihood the original visage from a bust of Antinous currently housed in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Altemps in Rome (fig. 9.27 and fig. 9.8). The fragment was carved from a fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Carrara. While no traces of original toolmarks remain, the sculpted surfaces show evidence of recutting, in addition to the combined use of acid and repolishing. No indication of polychromy or gilding has been detected. Studies of multiple samples of encrusting material on the primary break surface reveal that the fragment was likely buried in sediments containing ancient mortar debris. The object is somewhat pockmarked and abraded overall, but, given its complex history, it is in remarkably good condition. Little evidence of documented conservation treatments can be found, despite the object’s long residence in the museum’s collection. Recent scholarship for this publication has, however, brought renewed attention to the object’s features, condition, and history. Petrographic and isotopic comparisons of the Chicago portrait fragment and the Altemps bust suggest that the two pieces could have been carved from the same parent block of stone. The bust and a cast of the portrait were laser scanned and mapped, and from these data three-dimensional models were rendered. With the assistance of a team of specialists in Rome, the two models were brought together and unified convincingly in accordance with established iconographical scholarship regarding Antinous’s appearance.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is an extremely dense, fine-grained variety with an overall ivory hue, free of visible veins or banding. Burial has conferred on the face a somewhat mottled, ocher appearance.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); iron oxides, specifically hematite (traces)

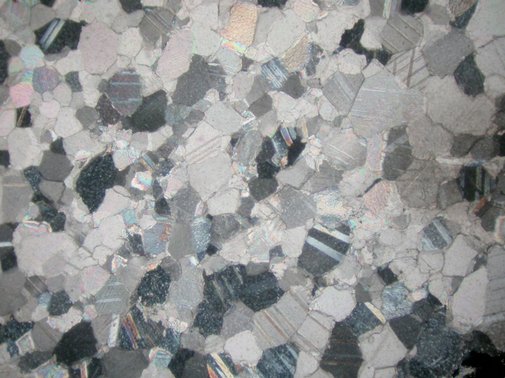

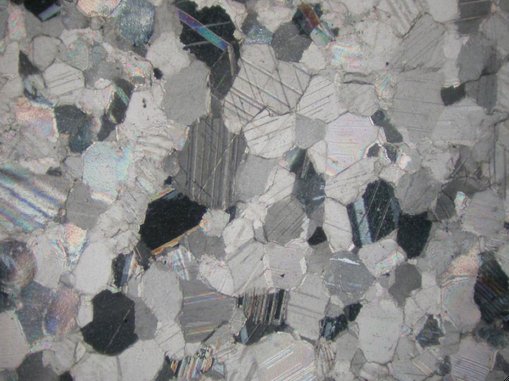

Petrographic Description

A semicircular fragment, approximately 2.5 cm high and 1 cm wide, was removed from the proper right edge of the primary break surface, level with the midline of the object. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 μm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.72 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: curved

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed strong decohesion.

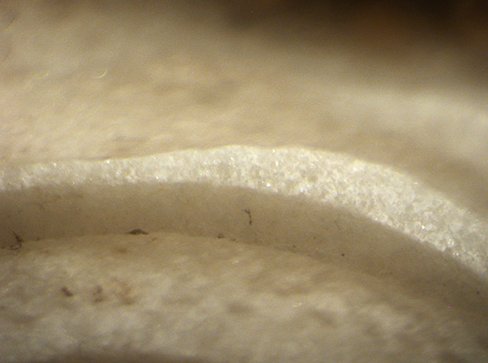

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 9.28

Provenance

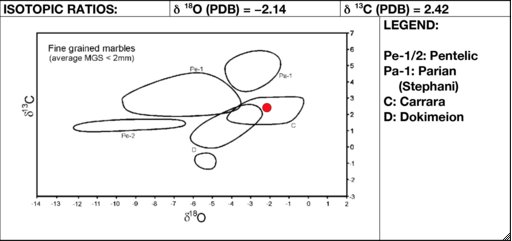

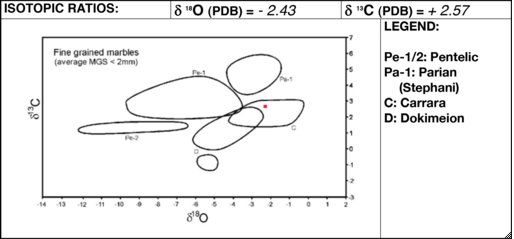

Marble type: Carrara (marmor lunense)

Quarry site: Carrara region, Apuan Alps, Italy

The determination of the marble as Carrara was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 9.29

Fabrication

Method

The object is a fragment of a portrait bust. The fragment was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The face and much of the hair were repolished subsequent to the rediscovery of the fragment. Therefore, little in the way of ancient toolmarks remains on the surface. Indeed, it seems unlikely that the ancient surface is completely preserved anywhere.

The carving of the hair shows a pronounced trend toward simplification proceeding from the edges of the face to the crown of the head. From fully formed curls, the hair becomes progressively more shallow, and chisel marks, completely absent on the locks near the forehead, become continuous over the entire surface (fig. 9.30). Although the hair on the top of the head is cursory, the marks of two types of chisel are discernible, one flat and the other slightly curved. The retention of these marks, the freshly cleaved appearance of the marble grains, and the absence of encrusting deposits suggest that this is recutting, rather than the ancient surface. Examination under ultraviolet radiation of a section of hair on the back of the head, where the same chisel marks are also visible, reveals a semicircular area that appears a noticeably darker violet color (fig. 9.31), lending support to the theory that these toolmarks are the result of more recent recutting.

Within the curls, drill marks 2 mm in diameter are visible (fig. 9.32 and fig. 9.33).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The head is in reasonably good condition, its fragmentary state notwithstanding. Prominent scratches and gouges are visible on the proper right cheek and jaw. Their violet coloration under ultraviolet radiation suggests that they are relatively recent, and indeed they look very much like excavation-related damage. Minor spalls and abrasions are present throughout, in particular on the lower portion of the proper left cheek, on the proper left eyebrow, at the center of the bottom lip, on the outside edge of the ear, and at the center of the chin. All along the outer margin of the object, losses, spalls, and lacunae associated with the primary fracture are evident. Various small losses are visible on the tips of the curls framing the face, and there is a larger loss to a lock of hair on the proper right side. A significant abrasion extends horizontally across the proper right temple.

The nose was at one point fractured, and the break edge was modified from a natural break to a flat, easily matched surface and provided with texturing to secure a restoration that has since been removed. Examination of the nose under ultraviolet radiation reveals that this attachment was secured with a pin or round dowel (fig. 9.34). There are minor associated losses to the bridge of the nose.

The marble exhibits many blind, hairline cracks. The most significant of them extends through the hair downward from the crown of the head on the proper right side (fig. 9.35). Other large cracks can be seen traveling vertically in line with the break edge near the back of the head on the proper right side. Smaller cracks are also in evidence: a network of fine cracks runs horizontally along the proper right temple, a fine crack extends vertically for approximately 6 cm down the center of the proper right cheek, and another can be seen at the bottom of the earlobe. A short but deep crack is present on the chin. Most of the cracks are stained gray, but the staining is superficial and confined to the fissures (i.e., it did not travel laterally into the marble after entering along the fissures). The gray coloration is not a consequence of trace minerals naturally present in veins or localized along the cracks (as it can be in Carrara marble, in which trace dolomite along tectonic fissures is often a cause of gray patterning).

The sculpted surfaces are almost entirely free of weathering. Instead they show several forms of reworking resulting from a thorough restoration campaign. Removal of surface deposits was no doubt one of the motivating factors for this work, along with the elimination of smaller scars and abrasions that would inevitably have affected the prominent parts of the face. The hair around the face, the eyes, and the face more generally all appear to have softened contours consistent with an acid treatment. Acid often acts more rapidly on marble than on encrusting materials, however, and can accentuate disparities of the surface condition. To ameliorate this effect, physical polishing must have been employed as well. The extremely muted eyebrows are probably a result of this dual activity (fig. 9.36). In comparison, the contours of the eyelids are sharper, suggesting that some selective recutting was done to redefine certain details (fig. 9.37). Although recutting was not used to remove chips from the cheek and jaw, a small region of sculpted surface near the left eyebrow along the break edge was flattened by repolishing, probably to remove a chip there.

The difference between the condition of the hair on the top of the head and the condition of the face presents a puzzle. The freshness of the toolmarks in the hair demonstrates that acid was not employed there subsequent to the recutting (fig. 9.38). It may not have been employed there at all. Why would recutting so extensive as to leave marks on every lock of hair be undertaken on the least important and least visible part of the fragment? One possible explanation is that the restorer exercised less restraint in recarving the hair near the top of the head precisely because of the lesser importance of this area. Or it could be that, if the top of the head was weathered to the same extent as the much fuller locks near the face, it might have appeared almost featureless prior to recarving, given the low relief of the hair in this area. The use of acid and of more-careful polishing in the hair around the face may have been governed by the fact that the high relief and undercuts in that area left little room for recutting to be done without adversely affecting the hair’s form and volume, coupled with the restorer’s desire that it not be so evidently reworked as the top of the head.

A series of small pits can be seen in some of the low-relief areas of the un-recut hair framing the face. These are typical of lichen colonization on marble, sometimes associated with lichen apothecia (fig. 9.39). Traces of oxalates were also detected in these un-recut areas, which in this instance could support a history of biological growth on the surface of the object, although it could equally indicate the use of oxalic acid in its cleaning.

Various accretions and superficial stains are distributed uniformly across the sculpted surface of the object.

The primary break surface bears enough remaining residues to give confidence that this was approximately the surface as found. However, the break has been worked in a fashion typical of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to simplify the joining of the fragment to another mass of stone or to the plaque onto which it had been mounted by the end of the nineteenth century (see Curatorial Entry, para. 3). The periphery of the break was smoothed down to allow greater ease in matching it to a new opposing piece, or, it could be argued, to allow space for the introduction of an adhesive in order to rejoin the fragment with the opposing break surface without displacing the fragment forward. The surface was also keyed with a chisel to provide tooth for an adhesive (fig. 9.40). Plaster remains embedded in some of the deeper sections of the keying (fig. 9.41), no doubt related to the attachment of the fragment to the plaque.

Three samples were taken of residues that remain on both the carved and the broken surfaces in an attempt to learn more about the object’s past environmental exposures—including burial—and treatment. The largest fragments of the collected material were prepared as cross sections; the remainder were analyzed as fracture fragments, without further preparation, in order to perform tests intended to relate their compositions to the complicated mixture of ingredients that they contain. The results showed that all three examples are deposits containing mineral grains bound in a dense, nonporous matrix of calcite. In addition, some of the grains within these deposits appear to be fired siliceous matter of the types used for preindustrial, partially hydraulic mortars, as were employed by the ancient Romans for construction. Their presence on the head suggests that, after it was separated from the bust, it was buried in sediments containing detritus from building. That detritus appears to have contained preindustrial mortar but did not include modern portland cement, for which different, highly specific microstructures would be expected. The possibility cannot be excluded that the head itself was used as fill material for construction.

The recrystallization of the calcite matrix is so thorough that it is not possible to tell whether these presumed mortar residues arrived on the surface in a freshly prepared state, to become attached as the mortar hardened, or whether they became bound there after a long period of intimate contact in burial, during which recrystallization of the previously formed calcite resulted in their attachment.

Conservation History

At some point in time, three holes were drilled into the break surface of the fragment, possibly in order to mount it to the plaque to which it was affixed when it entered the museum’s collection. By the early 1960s the plaque had been removed. In 1983 segments of threaded rod were inserted into these holes and secured in place with lead, in order to attach a new mount.

The first recorded treatment of the object took place in 1993, with the goal of improving its overall appearance in preparation for exhibition. The stone was first cleaned by the application of high-pressure steam. The drill hole associated with the previous repair to the nose was filled with a proprietary filler toned with acrylic emulsion paints. The repair to the nose was further refined with powder pigments where necessary.

In 2007, following an examination that necessitated removal of the fragment’s mount, minor adjustments were made to the lead fittings.

In 2013 a resin cast of the object was made. In preparation for making the mold from which the facsimile was cast, the entire surface of the marble was liberally coated with a dilute acrylic resin. Upon completion of the project, the resin was removed by solvent means.

Establishing a Relationship to the Altemps Bust

The precise circumstances by which the Chicago fragment and the Altemps bust might have been separated from one another are a mystery. The portrait fragment displays no clear evidence of a purposeful blow or imposed fracture leading to the break. The Altemps bust is itself fragmentary, with major breaks through both shoulders and across the neck. Lesser fragments are present in association with these breaks. The face and the socle are restorations. The degree of fragmentation raises the possibility that, in their original burial context, the pieces of the sculpture were dispersed so widely as to escape full recovery. Or perhaps the original find site was compromised, and some of the fragments were transferred to a different archaeological stratum. The precise reasons why the entire sculpture was not recovered simultaneously will likely never be known. Important information could be gleaned from an examination of the break surface of the head of the Altemps bust to determine more about the correspondence of the surfaces and the potential causes of the separation of the Chicago fragment, and from an analysis of any residues on that surface to discover whether the same burial deposits are present. Regrettably, such lines of inquiry are prohibited by the attachment of the restored head to the bust.

Collaborative Work with Palazzo Altemps

Visual comparison

As an initial step in trying to discern whether the Chicago fragment originally belonged to the Altemps bust, a resin cast of the fragment was made. Vital to the investigation was the precise reproduction of its perimeter and its break surface. The cast was taken to Rome for visual comparison with the bust, in the course of which many similarities in the overall appearance of the two objects, in addition to the scale and the angle of the break edges, became immediately apparent.

Petrographic and isotopic comparison

On the basis of the visual similarities between the cast of the Chicago fragment and the Altemps bust, a more systematic study of the two objects was undertaken. To that end, a second sample, a large triangular fragment approximately 1.8 cm high and 1.3 cm wide, was removed from the bottom proper right quadrant of the break surface of the portrait fragment. The sample was used to perform minero-petrographic analysis, in accordance with the procedure outlined above (see para. 32, note 65).

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant)

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.96 mm

Fabric: almost homeoblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: curved

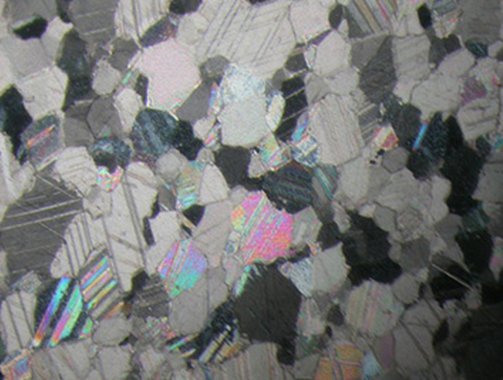

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 9.42

An ovoid fragment 2.5 cm high and 0.8 cm wide was removed from the verso of the Altemps bust, from the proper left edge of the pillar, approximately 8 cm up from the bottom edge of the top molding of the socle. This sample was also used to perform minero-petrographic analysis as described above.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant)

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.95 mm

Fabric: almost homeoblastic mosaic, slightly lineated

Calcite boundaries: curved

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 9.43

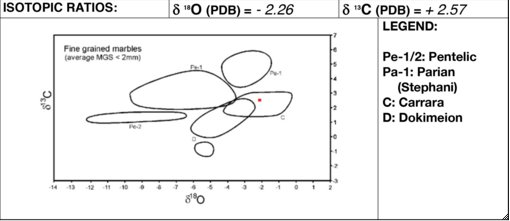

Isotopic analysis was also carried out on the two samples in accordance with the procedure laid out above (see para. 41, note 69). Both samples were determined to be Carrara marble, and the results of both the minero-petrographic and the isotopic analyses were sufficiently similar that the two pieces could have come from the same block of marble.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 9.44

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 9.45

Digital comparison: Laser scanning and computer modeling

To further test the theory, it was decided that an altogether new head would be created, composed of the Art Institute fragment and the Altemps bust. First, complete laser scans were made of both the bust and the resin cast of the fragment. For the method of laser scanning that was used, reflective, high-contrast targets are placed at various points on the surface of the object to be scanned (see fig. 9.46). The points are chosen to give the best representation of the object in three dimensions. The scanner emits monochromatic laser light that reflects off the targets and returns to the scanner. The scanning software processes the time it takes for the light to cycle to and from each point in order to define the distance of each point from the laser. The points are then recorded relative to the x, y, and z axes. At the same time, the scanner records the intensity of reflectivity of each target, whose angle relative to the direction of the light provides more information about the contours of the object. From this very dense cloud of data, a three-dimensional model of the object can be created with the assistance of specialized modeling software and a 3-D printer.

Once the cast of the fragment and the bust had been scanned, the restored face of the Altemps bust was digitally removed from the computer model along the presumed break line. Physical models of both the Chicago fragment and the original portion of the Altemps head were then printed at a 1:3 scale. Modeling clay was used to tack the two models together to permit evaluation and refinement of the positioning of the parts (fig. 9.13). Once their alignment was agreed upon, a void remained between the two parts, with the widest part of the gap occurring along the proper left jawline. This gap was filled with modeling clay, and the missing curls were sculpted in accordance with the existing hair and with reference to a treatise on Antinous’s portrait types (see fig. 9.16). Following feedback and suggestions from both institutions, minor corrections were made, and this finished, fully modeled copy was in turn scanned to produce a new model, also at a 1:3 scale.

In order to print a 1:1 model, whose dimensions could not be accommodated by the 3-D printer, the computer model of the fully integrated bust was digitally separated into fifteen parts, which were printed individually (see fig. 9.47). The printed parts were assembled on a specially designed support that allowed for very precise alignment. Once the parts were aligned, the seams were filled and the surface was refined and finished. A mold was made from this model, and a final model will be cast in plaster.

Rachel C. Sabino and John Twilley, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini

Exhibition History

Art Institute of Chicago, Sculpture from the Classical Collection, Sept. 1, 1987–Aug. 31, 1988, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago’s Dream, a World’s Treasure: The Art Institute, 1893–2007, Nov. 1, 1993–Jan. 9, 1994, not in cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Death on the Nile, Mar. 15–Apr. 17, 2008, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Portrait of Antinous, in Two Parts, Apr. 2–Sep. 5, 2016, no cat.

Museo Nazionale Romano in Palazzo Altemps, Rome, Italy, Antinoo, un ritratto in due parti, September 14, 2016–January 15, 2017, no cat.

Selected References

Frank B. Tarbell, “A Marble Head of Antinous Belonging to Mr. Charles L. Hutchinson of Chicago,” Art in America 2 (1914), pp. 68–71 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Back Matter,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 23, 1 (Jan. 1929), p. 12 (ill.).

“City Spaces: Henry Geldzahler,” Brutus (Burutasu) 50 (Sept. 15, 1982), p. 48 (ill.).

“La Casa delle Collezioni (The House of Collections),” Domus (Aug.–Sept. 1983), pp. 34–35 (ill.).

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Roman Imperial Persons in North America,” Celator 17, 12 (Dec. 2003), p. 30.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Faces of Empire,” Celator 19, 12 (Dec. 2005), p. 24, fig. 4.

Karen B. Alexander, “From Plaster to Stone: Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Karen Manchester (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 31, fig. 15.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

Visible Light

Normal-light and raking-light overalls: Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens

Normal-light and raking-light macrophotography: Nikon D5000 with an AF Micro NIKKOR 60 mm 1:2.8 D lens

Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens and a Kodak Wratten 2E filter

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

High-Resolution Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Canon EOS1D with a PECA 918 lens and a B+W 420 (2E) filter pack. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Visible-light microscopy: Zeiss OPMI-6 stereomicroscope fitted with a Nikon D5000 camera body

Reflected-light microscopy: Olympus wafer inspection microscope with metallurgical 5×, 20×, 50×, and 100× plan fluor objectives and polarized illumination

Petrographic and thin-section analysis: Leitz DMRXP polarizing microscope equipped with a Leica Wild MPS-52 camera head

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry

Finnigan MAT 5000 mass spectrometer

X-ray Diffraction

PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with vertical goniometer (CuKα/Ni at 40 kV, 20 mA)

Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy (FTIR)

Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrophotometer with a Hyperion 2000 Automated FTIR microscope fitted with a nitrogen-cooled MCT detector

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Scanning electron microscope: LEO 1550, with Schottky FEI source and both secondary and backscatter electron imaging modes. Beam accelerating voltage: 20 kV for backscatter imaging, 12 kV for secondary electron imaging.

X-ray spectrometer: EDAX energy-dispersive Si(Li) drift detector

Laser Scanning and 3-D Printing

Laser scanning: ZCorp ZScan 800 high-resolution handheld scanner (resolution 50 μm in all dimensions; sampling speed 25,000 measurements per second) with VXelements scanning software and Geomagic modeling software

3-D printer: ZCorp ZPrint 350 (20 mm/hour vertical build speed; resolution to 300 × 450 dpi on the x and y axes and to 0.004 inch on the z axis) using zp151 printing composite (calcium sulfate hemihydrate)