Cat. 9

Bullfight

1865/66

Oil on canvas; 48 × 60.4 cm (18 7/8 × 23 3/4 in.)

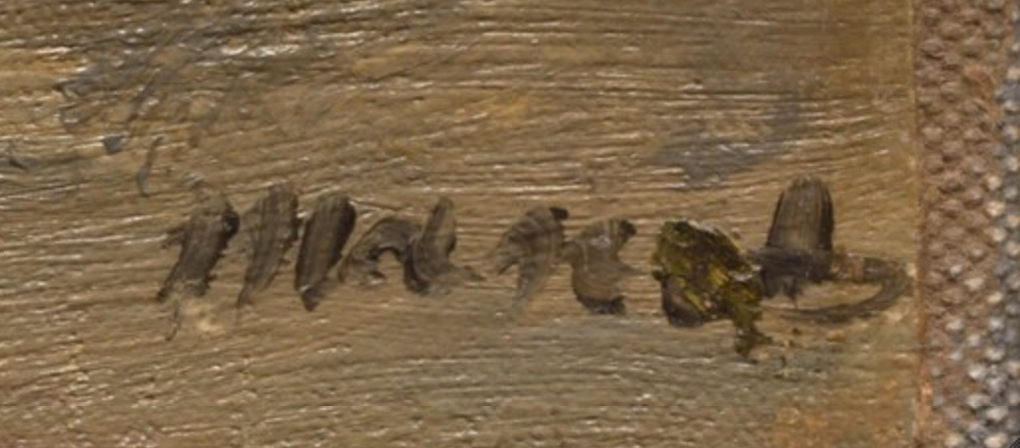

Signed: Manet (lower right corner, in grayish-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1937.1019

In the sunlit ring of Madrid’s old plaza de toros, Manet’s bullfight approaches its consummation. The second of three acts, or tercio de banderillas (literally the “third of little flags”), has ended, and the finale, the tercio de muerta (“third of death”) or faena, has just begun. The beast, stuck with paper-decked darts (banderillas) and switching its tail, forms a dark silhouette against the bright sand. His gaze is fixed on the red flag (or muleta) in the left hand of the matador, the star bullfighter, who turns his back to the picture plane, holding in his right hand a sword (or espada) poised for the kill. Here is a moment of action suspended, a great stillness amid the struggle. The eviscerated horse of a picador (lancer) in the middle distance at right reminds us of the violence already accomplished, while a smear of blood, painted wet-into-wet beside the artist’s signature, presages more to come (see fig. 9.1). Yet even the supernumerary bullfighters—perhaps a chulo (a kind of bullfighter’s assistant) at right, bearing away the dead horse’s saddle, and two smartly dressed peones (fighters who take part, on foot, in the tercio de banderillas) at left—seem curiously still. Emphatic horizontal bands—the wooden barrera (barrier), the double row of boxes, the tiled roof, and the ribbon of sky—lend weight and geometric structure to the composition, enlivened by Manet’s palpitating brushstrokes—the colorful crowd, the paper-decked banderillas, the matador’s glittering costume and glinting blade.

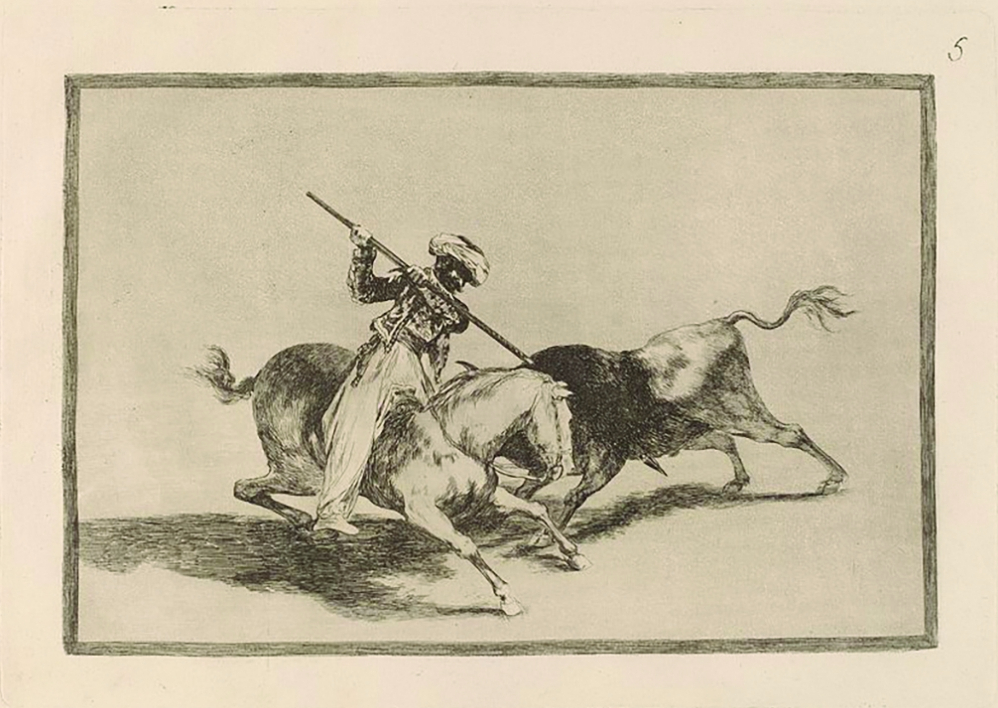

This canvas is one of three bullfight scenes Manet painted upon his return from a brief trip to Spain in 1865. The other two are a substantially larger, more dramatic composition (fig. 9.2; [RW I 107]) likely painted before the Art Institute picture, in late September or early October 1865, and a mid-sized canvas characterized by a light, feathery touch (fig. 9.3; [RW I 109]) probably either painted or extensively reworked in the 1870s. All three suggest their maker’s desire, in the words of Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, to “serve up still warm” the memory of a bullfight he had witnessed in Madrid. Manet’s approach to the theme in these works—airy, luminous, closely observed, and freely painted—diverged sharply from that in his earlier bullfighting pictures—artificially lit, emphatically posed, and carefully worked up from his own imagination. Most notable among these early works are Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada (fig. 9.4; [RW I 58]), a self-conscious studio travesty painted in 1862 and exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, and Episode at a Bullfight, an ambitious multifigure scene greeted with savage reviews at the Salon of 1864 and subsequently cut into pieces (see fig. 9.5; [RW I 72] and fig. 9.6; [RW I 73]). This cutting up may have occurred in early 1865, and there is some reason to believe that at least one of the fragments, the Frick Collection Bullfight, was reworked after the Spanish journey. Manet’s experience of an actual bullfight in Madrid was thus bookended by intense pictorial explorations of the theme, inspired by his interest in Goya; his friendship with the hispanophile writers Zacharie Astruc and Charles Baudelaire; and by his admiration for a somewhat unlikely picture at the Musée du Luxembourg: Alfred Dehodencq’s Bullfight in Spain (Los Novillos de la Corrida) (fig. 9.7), exhibited at the Salon of 1850–51 and purchased by the state. In its solemn face-off between man and beast, the Chicago Bullfight looks back to Dehodencq’s dusty provincial corrida, which, if Antonin Proust is to be believed, furnished the whole motive for Manet’s journey to Spain.

The artist probably left Paris on August 29, making stops at Burgos, Valladolid, Madrid, and Toledo, and returned to France before September 14, when he wrote to Baudelaire from a family house in the Sarthe with an account of the journey, enthusing, “One of the finest, most curious and most terrifying sights to be seen is a bullfight. When I get back I hope to put on canvas the brilliant, glittering effect and also the drama of the corrida I saw.” The bullfight described in such lyrical terms had taken place in Madrid on the afternoon of Sunday, September 3. The entertainment began at half past four and featured six bulls, considered by true aficionados unremarkable, if not disappointing. Several horses, however, were gored, and Manet remembered the corrida, along with his experience of Velázquez at the Muséo del Prado, as a highlight of his week in Madrid.

Théodore Duret apparently attended this fight with the artist. The future critic and biographer (fig. 9.8; [RW I 132]), traveling at that time in Spain on behalf of his family’s cognac business, had befriended Manet in the dining room of the Grand Hôtel de Paris at the Puerta del Sol the night of the artist’s arrival, and they spent subsequent days visiting the Prado and exploring the cafes of the Calle de Sevilla together; it was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Duret later reported that Manet had sketched throughout the corrida and used drawings made sur le motif as the basis for his three subsequent pictures. One of these may survive, a pencil drawing revisited in watercolor; the attribution of this sheet has been the object of some discussion (fig. 9.9; [RW II 530]). The drawing portrays a bull goring the horse of a picador, whose limp body is hoisted out of the saddle and over the barrera: here is all the “drama” suggested in the letter to Baudelaire. Indeed, the action in this drawing corresponds quite closely to that described in a second letter penned upon Manet’s return to France, this one to Astruc: “the outstanding sight is the bullfight. I saw a magnificent one, and when I get back to Paris I plan to put a quick impression on canvas: the colorful crowd, and the dramatic aspect as well, the picador and horse overturned, with the bull’s horns ploughing into them and the horde of chulos trying to draw the furious beast away.”

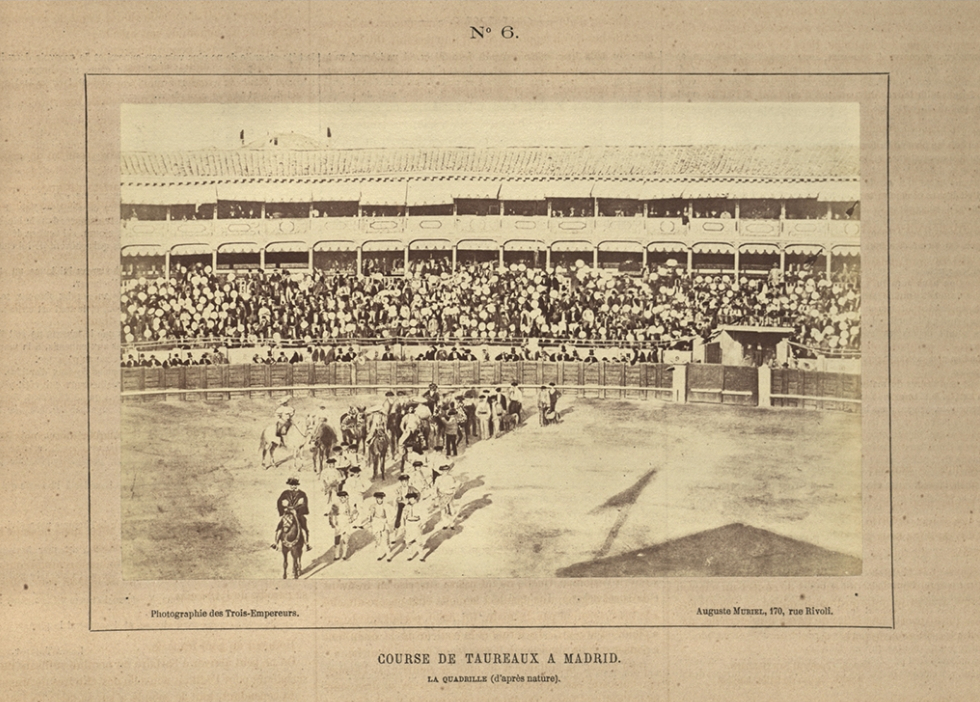

By October 13, the artist had made good on his plan, writing from Paris to Duret, “I have . . . already painted The Bullring in Madrid since my return; I would love to have your dauntingly frank opinion of it on your next trip to Paris.” This painting, today at the Musée d’Orsay (fig. 9.2), treats the subject described to Astruc at a far grander scale than the watercolor. The centripetal action converges on a white horse, into whose side the bull’s horns have plunged so far that his head disappears from view. A team of auxiliary fighters rushes to extract the rider from his dying mount, while two further picadors at left and an additional chulo, at right, gaze out of the picture with peculiar detachment. The composition is as close as Manet would ever come to the great lion hunts of his early idol Delacroix. As others have pointed out, the scene is fanciful in various respects (in reality, for example, two picadors, not three, appear in each tercio de varas (literally the “third of lances,” the first portion of the bullfight), but the precision with which Manet rendered the celebrated eighteenth-century arena, from its tiers and awnings to its tiled roof, suggests that he must have relied on published photographs (e.g., fig. 9.10) to provide a setting peopled with figures from his sketchbook.

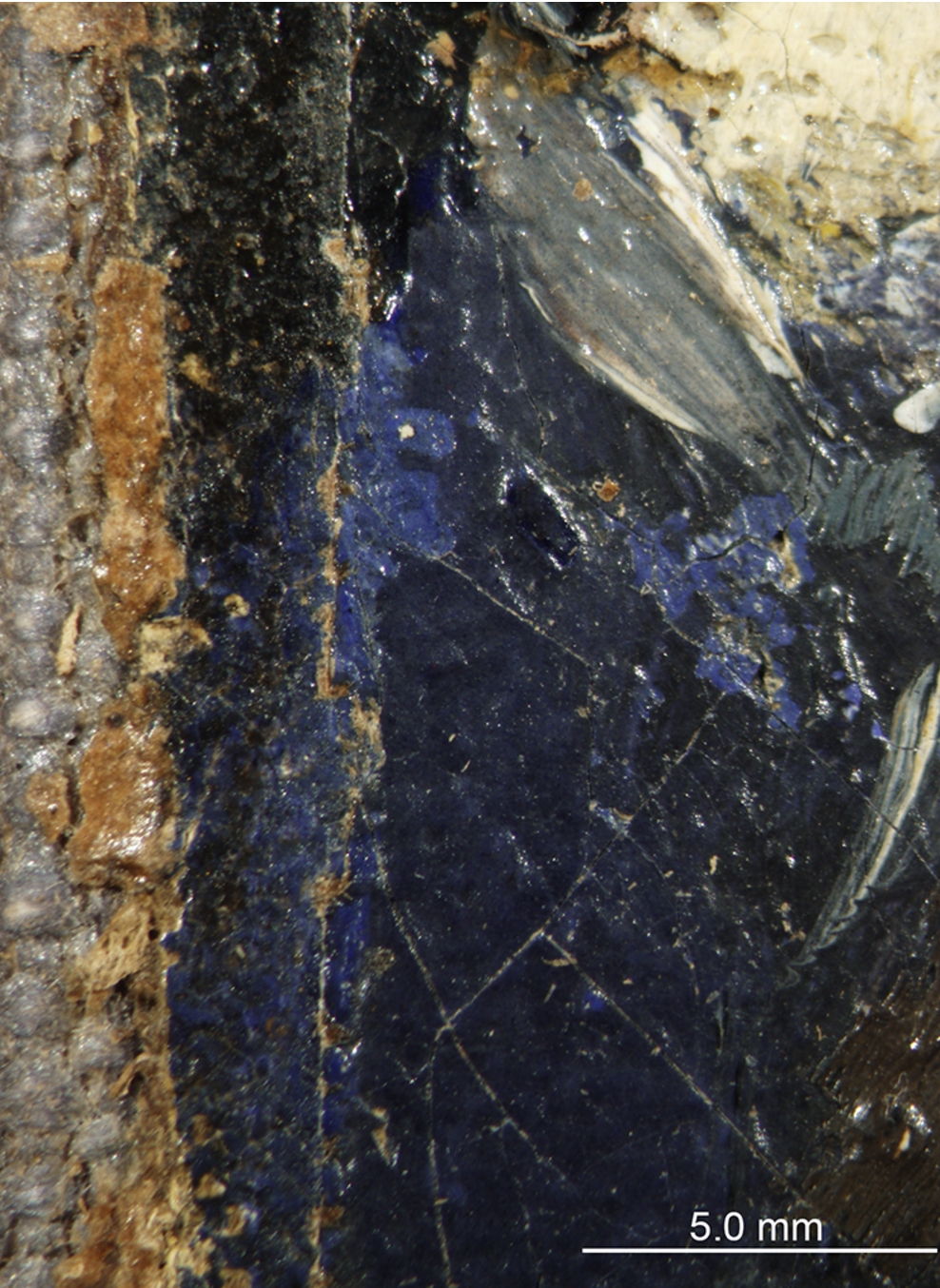

The influence of photography is likewise present in the Art Institute’s picture, here not so much in the architecture as in the play of light and shade in the foreground, where the bull and toreros cast slanting shadows (like those found in contemporary photographs) across the sand, and, perhaps, in the insistent cropping of both the matador’s ankles and the blue torero’s body at left. The canvas was literally cropped along its bottom edge (see fig. 9.11), most likely by the artist himself (who else would have dared make such a jagged, Exacto knife–style slice?), and so the matador could conceivably have possessed feet at one time. In the case of the torero in blue, however, a layer of light beige ground continues at left past the bisected figure (see fig. 9.12), indicating that Manet cropped him not with a knife but with his eye and his brush. The effect achieved is “photographic,” apparently calculated to suggest that this slice of reality at this moment in time was captured almost at random. Manet further enhanced the illusion of an instant arrested by exercising restraint and precision in his treatment of the matador and bull; this picture, markedly more faithful than its Parisian counterpart to the action of a real bullfight, portrays a quite specific moment at the beginning of the faena: not the matador’s flashy pases (dance-like misdirections of the bull using the muleta) or final death blow, but the calm before the storm.

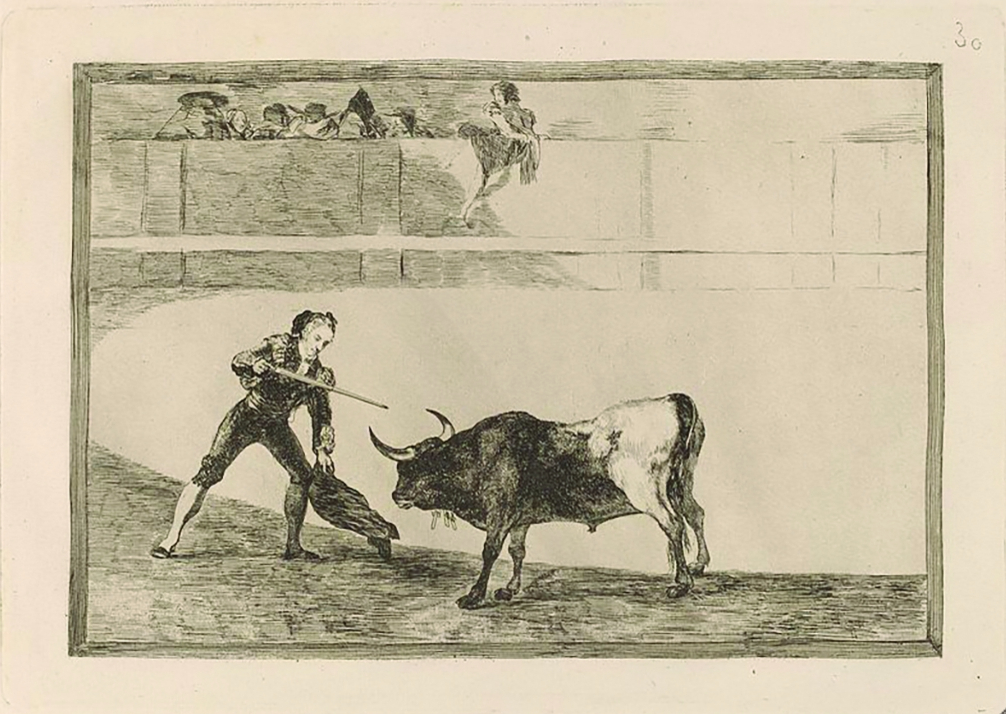

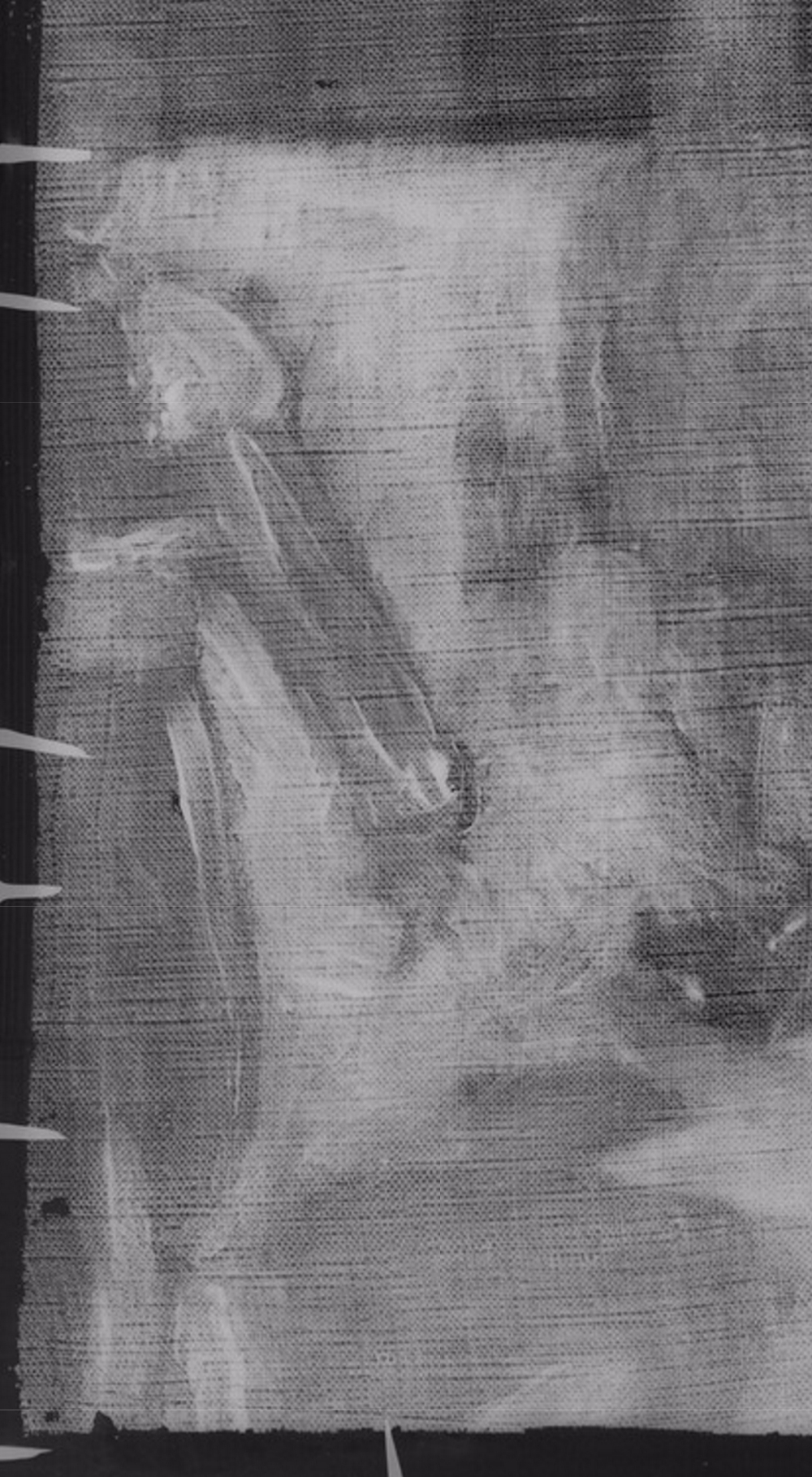

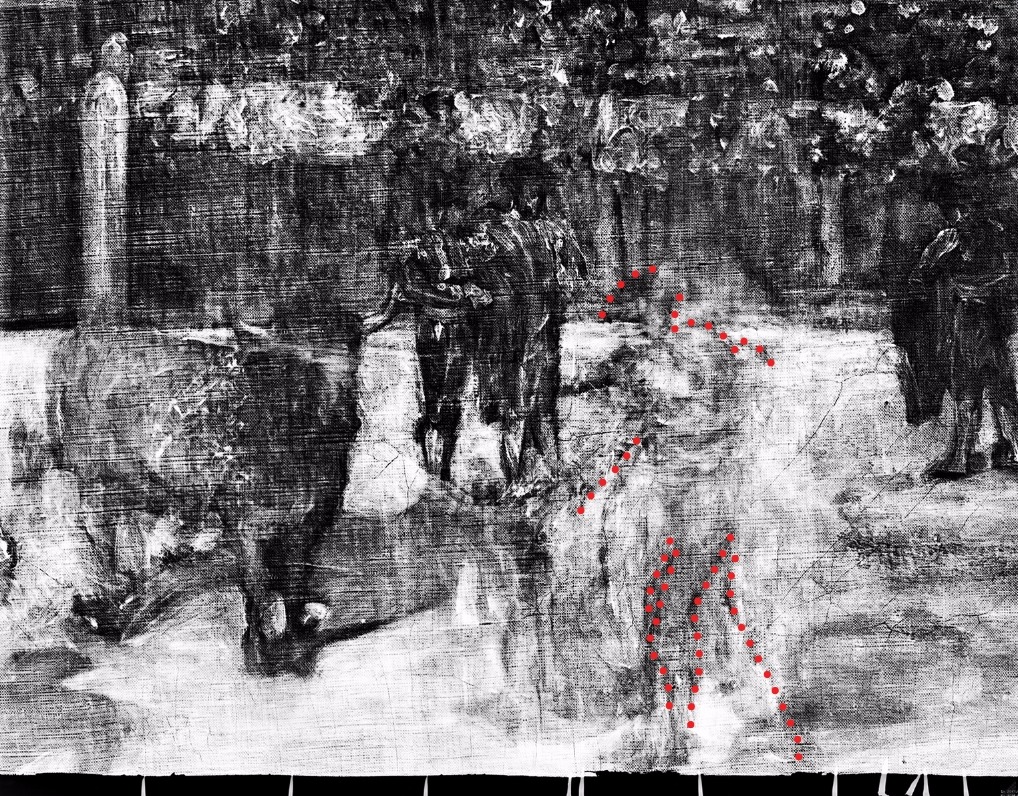

The artist, in other words, here sacrificed obvious drama in favor of apparent truth. An X-ray of the foreground lays bare this struggle (fig. 9.13), revealing that Manet at first envisioned a more active pose for his matador, lunging forward on his left leg with his arms extended before him, perhaps executing a paso. This treatment would have recalled plates from the end of Goya’s Tauromaquia (e.g., fig. 9.14), a suite of thirty-three etchings, first published in 1816, that Manet plainly knew and admired. As early as 1862, he had cited plate 5 from the series (fig. 9.15) in the background of Mademoiselle V. . . in the Costume of an Espada. His suppression of the original lunging, muleta-waving matador in the Art Institute’s canvas hence signals not only a turn away, in this second bullfight painted after the Spanish trip, from the romantic drama of the Orsay composition, but also an apparent rejection of the amateur theatrics found in pictures like Mademoiselle V. . . Having witnessed only one bullfight, Manet could not have had a sufficient grasp of the elaborate choreography for the matador’s pases to render them faithfully from memory. By eliminating the lunging figure and replacing him with a still one, Manet confined himself to painting what he knew.

Additional changes—somewhat more difficult to work out in the X-ray—were made to the bull, perhaps to accommodate the altered pose of the matador. No doubt in part to conceal the traces of these revisions, Manet also repainted the sand of the arena floor, brightening its color considerably (see Paint Layer in the technical report). Yellow paint skips over the contours of the matador; this change clearly occurred after that of his pose. A leftover strip of dark sand visible beside this figure’s ankles (see fig. 9.16) indicates how dramatic the shift must have been. The cumulative result of all this reworking is an unusually thick paint layer in the left foreground that stands in marked contrast to the airy treatment of the crowded stands.

If the Chicago picture is at pains to convey the action of the bullfight faithfully and without embellishment, it is apparently less concerned than its counterpart in Paris with architectural fidelity. Curved archways in the lower tier become square; the roof slopes off gently to the right; and the fence separating stands from stalls narrows to a thread of brown paint. Indeed, the whole background here is so thinly painted that the pale exposed ground can be glimpsed throughout (see fig. 9.17), lending the varicolored crowd and even the building itself a new lightness and sparkle, the very “brilliant, glittering effect” that Manet had suggested in his September 14 letter to Baudelaire. Painting the plaza de toros this second time, he could pay less attention to its architectural specifics, striving instead to convey the impression—of the crowd, the sunshine, the dust—that he had received there. The painting’s brisk, luminous setting, indeed, has led some modern art historians to identify this work with the first stirrings of Impressionism, predicting by nearly a decade the technical innovations of Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley.

It is fitting, therefore, that Bullfight was one of the twenty-three pictures purchased from Manet’s studio in January 1872 by Paul Durand-Ruel, the Impressionists’ future impresario. He wasted no time in exhibiting it, shipping it off to London the following summer for an Exhibition of French Artists that presented Manet as the Impressionists’ chef d’école, featuring twelve other works of his alongside smaller selections of pictures by Monet, Renoir, Sisley, and so on. Bullfight, however, apparently failed to find a buyer. After lending it to the posthumous show of Manet’s work held at the École des Beaux-Arts in January 1884, Durand-Ruel tried his luck in New York, where the picture appeared in the first dedicated Impressionist exhibition held in the United States in 1886. It was likely out of this show that James S. Inglis, an art dealer with the firm Cottier & Co., bought it. By 1895, however, Bullfight was back at Durand-Ruel’s New York gallery, where Martin A. Ryerson, the distinguished Chicago lawyer, collector, and philanthropist, bought it in 1911. It was Ryerson who lent the picture to the landmark Armory Show, an exhibition presented in New York, Chicago, and Boston in 1913, which introduced the American public to European modernism, including works by Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. With its fluttering brushstrokes and slice-of-life immediacy, this Bullfight, then half a century old, earned its place among the radicals of a quite different generation.

Emily A. Beeny

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Édouard Manet’s Bullfight was painted on a canvas that is close in size to a no. 12 landscape (paysage) standard-size canvas. The ground is off-white and appears to consist of two layers. The background and the sky are openly painted with areas of exposed ground throughout. The foreground is more densely built up, the result of the artist having reworked broad areas of the lower half of the composition. Manet originally painted the central matador in a more active pose, possibly with the bull directly in front of him. The artist then painted out this figure, probably with the original ocher-colored paint of the arena floor, which remains visible in a narrow band at the left bottom edge, and repainted the central matador in the upright position. At a later stage, Manet repainted the arena floor with the brighter, pale-yellow hue, along with other areas, including the costumes of the torero (at the left edge) and the matador, and the red muleta (the red flag). He also reworked areas around the first row of spectators.

The painting is currently lined and the original tacking edges have been cut off. The lining postdates damage that occurred to the painting in 1913; however, the presence of two layers of paper edge strips in places around the edges, as well as fragments of a very fine, open-weave fabric between the original canvas and the lining canvas, suggests that the work may have had an earlier lining. In two areas, original paint overlaps the lower layer of paper, suggesting that Manet may have had the canvas lined before reworking the lower half of the composition. This may have coincided with the removal of the tacking edges or possibly the cropping of the bottom edge of the composition. The edges are uneven and appear to have been rather crudely cut. Small areas of unpainted ground along the left, right, and top edges suggest that the composition was not cropped on those edges; the cut on the bottom edge, by contrast, was made entirely through the painting, although it is uncertain how much, if any, of the composition was cropped.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 9.18).

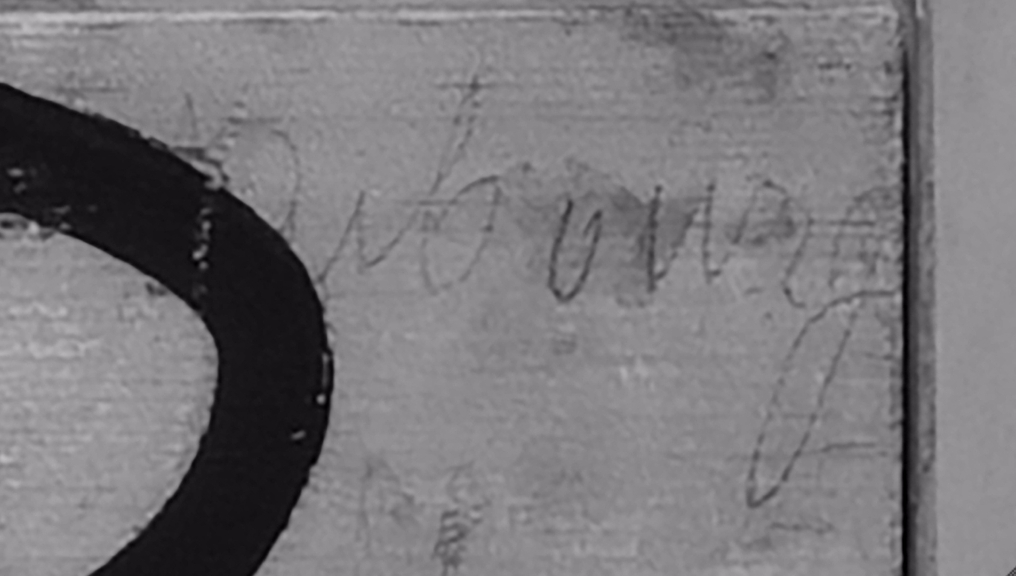

Signature

Signature/Stamp

Signed: Manet (lower right corner, in grayish-brown paint) (fig. 9.19). The work was signed when the underlying paint was still wet (fig. 9.20).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Linen (estimated).

Standard format

The original tacking margins have been cut off (see Conservation History). The current dimensions of the original canvas are approximately 47.0 × 59.5 cm. The closest standard-size stretcher is a no. 12 landscape (paysage), which measures 60 × 46 cm.

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 23.3V (0.6) × 20.4H (1.2) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft. No weave matches were determined with other Manet paintings analyzed for this project.

Canvas characteristics

There is strong cusping along the left edge, mild cusping on the right and bottom edges, and only slight cusping in places along the top edge. There are notable variations in the thickness of the threads.

Stretching

Current stretching: The current stretching probably dates to the 1913 aqueous lining (see Conservation History).

Original stretching: Not documented. The original tacking margins have been removed (see Application/Technique and Conservation History).

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: The current stretcher may be the original stretcher. It consists of five members, including a vertical crossbar, and has butt-ended, mortise and tenon, keyable corner joints; one key is present. Stretcher dimensions: overall, 48.0 × 60.4 cm; stretcher bar width, 5.5 cm; stretcher bar depth, 1.2 cm (inner), 1.8 cm (outer); crossbar width, 5.5 cm; crossbar depth, 1.2 cm (fig. 9.21).

Original stretcher: See above.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

None observed in current examination or documented in previous examinations.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

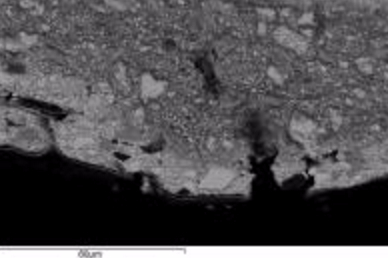

Because the original tacking edges have been cut off, it is not possible to determine whether the canvas was pre-primed. Based on cross-sectional analysis, the ground appears to consist of two layers. In the backscattered electron (BSE) images, the lower layer appears richer in lead white, as evidenced by its brighter white appearance, and more compact, with a finer particle size distribution compared to the upper layer (fig. 9.22). The lower layer ranges from approximately 10 to 30 µm in thickness. The upper layer ranges from less than 10 to approximately 60 µm.

Color

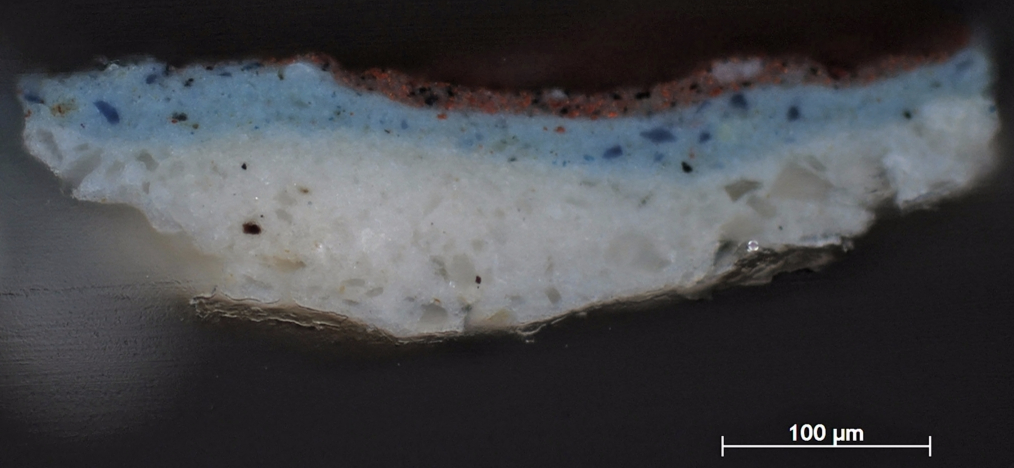

Off-white. Cross-sectional analysis shows that the lower layer has a similar tone to the top layer, and it is difficult to distinguish optically (fig. 9.23). The ground remains exposed in small areas throughout the painting (fig. 9.24).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the two ground layers have similar compositions, consisting mainly of lead white with trace to minor amounts of barium sulfate; however, differences in the lead to barium ratios and the trace components were indicated. The lower layer appears richer in lead white, with a smaller proportion of barium sulfate in the mixture, and it contains trace amounts of silicates and an iron oxide-containing pigment. The upper layer contains a higher proportion of barium sulfate, as well as trace amounts of silica. Traces of alumina were detected at the interface of the two layers.

Binding Media

Oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR) or microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revision

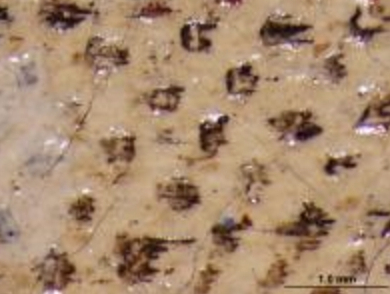

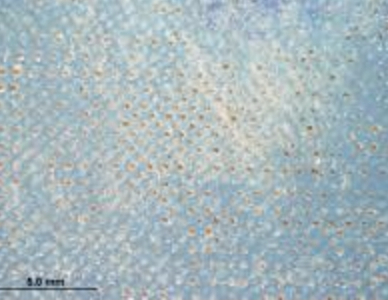

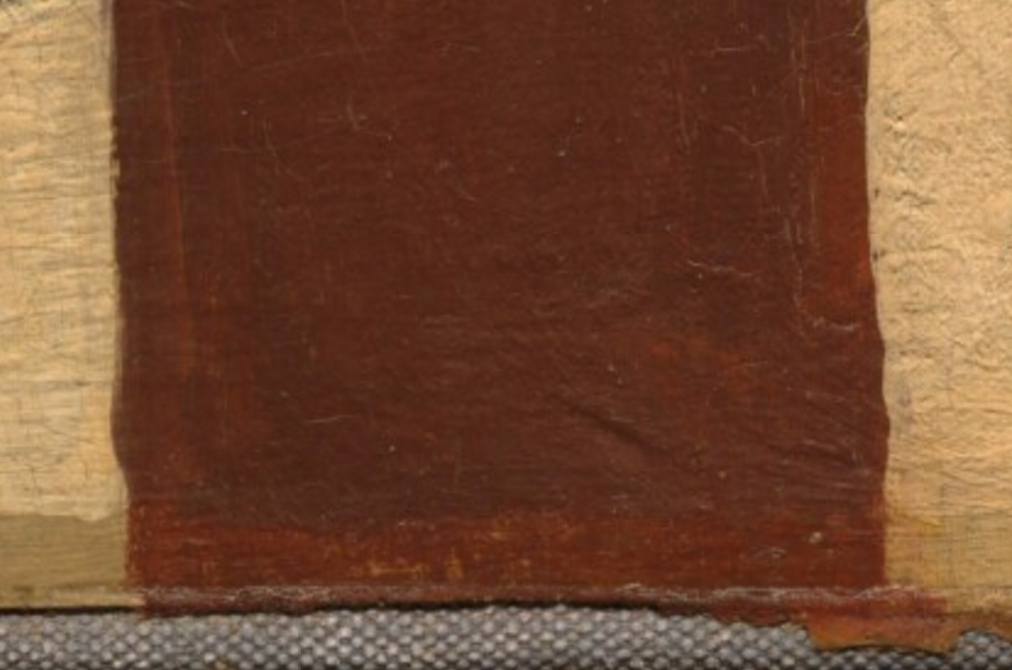

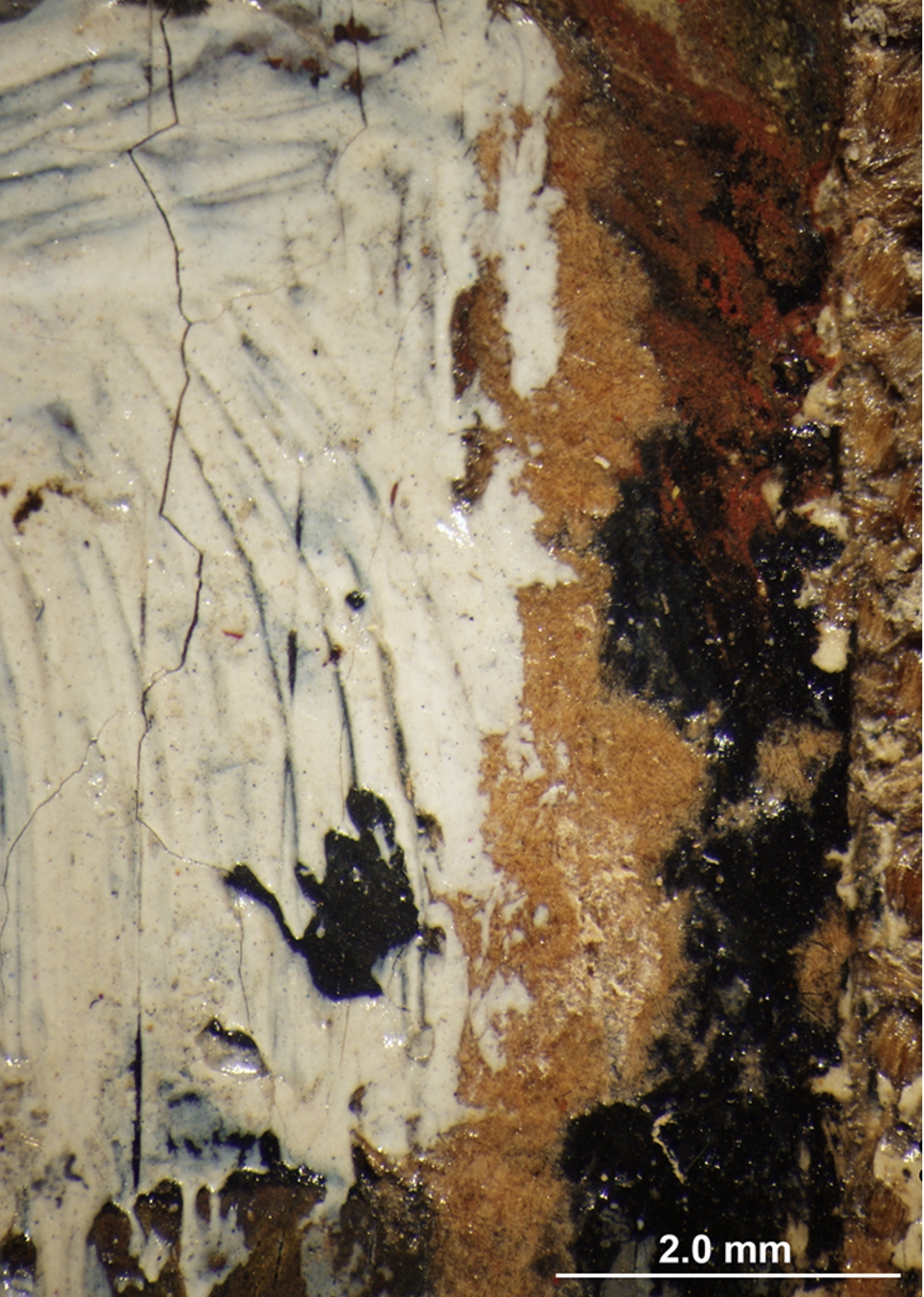

In building up the composition, Manet worked, generally, from background to foreground. The sky is very thinly painted with the ground layer visible throughout. The paint is abraded, sometimes down to the canvas (fig. 9.25), suggesting that the sky was scraped or wiped. The abrasion appears to be part of the artist’s process; it seems to be his method of rendering lighter areas or clouds in some places. The stadium was painted using loose, open brushwork with exposed ground contributing much of the light, off-white tone. The dark-brown paint of the shaded bays of the upper tiers of the stadium were painted first and then light-colored strokes were used to define the architecture. In some places the dark paint was more broadly applied and then the individual bays were delineated with a single vertical, off-white stroke to describe the columns that separate them; in other places the dark brown was applied in more discrete rectangular forms (fig. 9.26). In the background, the spectators are merely suggested by wet-in-wet daubs of brown and gray paint (fig. 9.27). Moving closer to the foreground, the crowd is rendered by overlapping touches of similar browns and grays, but Manet also incorporated more colorful hues (fig. 9.28 and fig. 9.29). The figures in the front row are painted with more individualized detail but still appear to have been rapidly executed with wet-in-wet paint applications (fig. 9.30, fig. 9.31, and fig. 9.32). The reddish-brown barrera was in place before most of these figures were painted (fig. 9.33). It was then reinforced in some areas with thicker paint that overlaps the lower edges of the figures (fig. 9.34).

Manet broadly reworked the lower half of the painting, probably in conjunction with a significant change made to the central matador. X-ray images indicate that the matador was originally in a more active pose (fig. 9.35 and fig. 9.36). Although the dense buildup of paint in this area makes it difficult to resolve the earlier figure, the legs appear to have been separated and the head and shoulders were tilted forward, as if in a lunging motion. Traces of dark paint are visible in the area of the head and legs of the earlier figure (fig. 9.37 and fig. 9.38). A diagonal line that has been partially painted over may indicate that the matador’s sword was originally painted at more of an angle (fig. 9.39 and fig. 9.40). Other outlines visible with transmitted-infrared imaging suggest another form in front of the figure. This area is also difficult to read, but the form just to the left of the matador’s leg is similar to the shape of the legs of the bull in the final painting (fig. 9.41). This could suggest that the bull was closer to the matador in the earlier version of the composition. The bull in the final painting is relatively transparent in the X-ray, especially the head and front quarters, which suggests that it was incorporated early in the painting process; however, it is difficult to know how far Manet developed the first version of the composition, or whether he scraped away paint layers before making changes in this area.

When Manet repainted the matador in the current upright position, the shadow of the bull extended farther to the right, underneath the red muleta (fig. 9.42). This seems to indicate that the muleta was not present or was perhaps in a different position. There is some brushwork visible in the X-ray that does not correspond to the surface image, which could suggest folds in a cloth that hung down vertically from the matador’s hand (fig. 9.43). At this stage in the painting process, the floor of the arena was a warm-ocher color, which can be seen in places along the bottom edge of the canvas and around the edges of the figures and animals (fig. 9.44, fig. 9.45, and fig. 9.46). At the ankles of the matador, the ocher-colored paint mixes wet-in-wet with the edge of the figure, indicating that the arena floor and the new version of the figure were painted simultaneously (fig. 9.47). When the muleta was added to the composition, it was painted on top of the ocher-colored floor (fig. 9.48), bringing the composition to its current configuration. The muleta originally extended a few millimeters further to the right (fig. 9.49). At a later moment, however, the artist repainted the arena floor with thick, pale-yellow paint that he brought up to and around the figures and animals. In places, the pale-yellow paint slightly modified the edges of the figures, for example, where it overlaps the leg of the peone (assistant) dressed in green (fig. 9.50). The shadowed region in the lower right corner was also reworked at this point, but this does not seem to extend all the way to the lower right edge and the signature may have been applied before the arena floor was repainted.

After the arena floor was repainted, some parts of the composition were reworked or reinforced. This includes the torero in the lower left corner, the matador, the muleta, the bull, and the horse. Curiously, this stage of the reworking stops approximately 5–6 mm short of the bottom edge on the left half of the painting. The absence of the artist’s reworking along this edge provides some information about the earlier versions of the two figures. The torero was originally painted with a white stocking, which was then covered with dull-brown paint; the shadow was also repainted, similarly stopping short of the edge of the painting (fig. 9.51). Further up the figure, brighter blue paint is visible along the edges where the thick yellow paint of the floor slightly overlaps the figure and at small breaks in the upper brushwork (fig. 9.52). The X-ray also reveals underlying brushwork that may indicate that the position of the figure’s leg was changed, but it is difficult to say at which stage of the painting process this occurred (fig. 9.53). Along the bottom edge, the matador shows a similar kind of repainting of the costume (fig. 9.54 and fig. 9.55). It is unclear if or how much the rest of the costume was reworked, but there appear to be some slight adjustments around the edges of the figure, especially the outstretched arm (fig. 9.56). Since some of the edges appear to have been worked wet-in-wet with the pale-yellow paint of the arena floor, it is likely that the matador and the floor were reworked simultaneously. The muleta was also repainted with a slightly darker red paint than in its initial painting, which remains exposed in a narrow band at the bottom edge (fig. 9.57). Changes to the bull were minimal, but the pale-yellow paint of the floor was used to slightly trim the size of the rump and the tail was reworked and overlaps the pale-yellow reworking of the floor (fig. 9.58). Similarly, the shadow on the right side of the horse overlaps the pale-yellow paint, indicating that it was reworked after the arena floor was repainted (fig. 9.59). Another change was made on the left side of the horse. Again, it is difficult to identify the underlying forms, but some distinct shapes are visible in the transmitted-infrared image (fig. 9.60).

Other minor modifications likely coincided with the reworking just described, such as the thick, off-white brushwork added behind the first row of spectators (fig. 9.61). Manet worked back and forth in this area, making it difficult to clearly follow the sequence of painting: some of the figures appear to mix wet-in-wet with the off-white background paint; some of the figures were painted over the top edge of the barrera, while in places the barrier overlaps the lower edges of the figures; and, similarly, paint from the figures from the row behind continues both underneath and on top of the off-white background paint from the lower tier. The transmitted-infrared image reveals some underlying shapes, but it is hard to know whether these represent changes to the composition or simply reflect the way the brushwork was built up (fig. 9.62).

There is evidence that an earlier lining of the painting may have been carried out during Manet’s lifetime. Remnants of paper edge strips and a very fine open-weave fabric between the original canvas and the current lining canvas (fig. 9.63) could be related to an earlier lining. In two areas, original paint overlaps the paper fragments, suggesting that the painting may have been lined before the artist completed work on it. At the bottom edge, the red muleta and the earlier ocher-colored floor extend over a fragment of the paper (fig. 9.64). On the right edge, the thick off-white paint of the wall behind the first row of spectators overlaps a small fragment of the paper (fig. 9.65). In both cases, the overlapping paint appears to be part of the reworking of the lower half of the painting. This raises the question of why an early lining of the canvas would have been necessary. Careful study of this painting and observations about Manet’s practice gained from the examination of other Art Institute paintings offers two possible explanations. As discussed above, the presence of areas of unpainted ground on the top, left, and right edges indicates that the composition was not cropped on those sides when the tacking margins were removed, but it is unknown if the bottom edge was cropped or by how much. The edges of the canvas are uneven and there are score marks along the bottom edge that appear to have been made when the paint was still soft, and that could be related to the cutting of the canvas, which was crudely executed (fig. 9.66). If Manet cropped the bottom edge of the composition, removing the tacking edge in the process, then lining would have been necessary in order to be able to stretch the canvas. (A similar hypothesis was drawn in the case of Manet’s Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers (see Application/Technique in cat. 5): the early lining of that canvas was probably necessitated by the fact that Manet incorporated the bottom tacking edge into the composition). Alternatively, if Manet executed the painting on unstretched canvas (as has been observed on other Art Institute paintings (see Application/Technique in cats. 2, 3, and 16), and there was insufficient material around the edges of the composition to tack the canvas to the stretcher, a lining canvas would have been necessary. It cannot be ruled out, however, that the tacking margins were cut during a later restoration campaign.

Painting tools

Brushes, including approximately 2–5 mm wide, flat ferrule (based on width and shape of brushstrokes).

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, chrome yellow, Naples yellow, red and yellow iron oxide-containing pigments, burnt umber, vermilion, cobalt blue, viridian, emerald green, and bone black.

Binding Media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting has a synthetic varnish that was applied in 1963. The surface is even and saturated.

Conservation History

There is evidence that the painting may have been lined before the artist completed work on it. In 2013, removal of the paper edge strips from the 1913 lining revealed remnants of another layer of paper underneath and fragments of a very fine open-weave fabric between the original canvas and the lining canvas (fig. 9.67). The fabric could be a cheesecloth interleaf related to an early lining. Original paint was found to pass over fragments of the paper in two places (fig. 9.68 and fig. 9.69). This suggests that the painting may have been lined and that the paper edge strips were added at some point during the painting process. The artist then continued to work on the composition, repainting areas of the foreground. Whether the bottom edge of the composition was cropped by the artist and whether the tacking margins were cut off before this lining or at a later date remains uncertain.

Correspondence in the conservation file indicates that the painting was lined in 1913, after it suffered damage in transit from the Armory Show in New York. The correspondence mentions that the glass from the frame was broken, resulting in tearing of the canvas and scratching of the paint layer. The current aqueous lining was probably applied at this time, along with the upper layer of paper edge strips, but there is no documentation of the treatment.

In 1963, discolored surface films and overpaint were removed. A spray coat of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA was applied. Inpainting was carried out. A final spray coat of methacrylate L-46 was applied. Based on photographs taken before and after this treatment, it appears that the paper edge strips were removed from the right edge of the painting at this time.

In 2013 the paper edge strips were removed from the top, bottom, and left foldover edges to reveal the edges of the original canvas. In the process, an earlier layer of paper was revealed, possibly related to an early lining or other treatment. Only fragments of this earlier paper remained, pressed slightly into the surface of the paint and covered by a layer of varnish. Much of what remained of the older tape was removed before it was noted that a couple of brushstrokes of original paint overlap the paper, indicating that the first layer of paper strips may have been applied before Manet finished the painting. It was decided not to pursue the removal of the remaining paper fragments.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition but has suffered from previous damage and restorations. The canvas is lined with an aqueous adhesive and stretched taut and in plane. The original tacking margins have been cut off. The painting was damaged in 1913 when glass from the frame broke in transit. At that time, it was noted that the glass had torn the canvas away from the stretcher. This probably referred to tears that occurred at the foldovers, since the canvas in the compositional area is intact with only a couple of small, localized damages. It appears that an earlier lining was present before the 1913 treatment; fragments of a fine open-weave fabric, possibly related to a cheesecloth interleaf from the earlier lining, are visible on the left edge. There are scores in the paint layer near the bottom edge. These appear to have occurred when the paint was still soft and may be related to the removal of the tacking margin or possibly to the cropping of the bottom edge of the composition. There are several scratches in the paint layer, mainly located in the sky, with associated retouching that is slightly mismatched. There is also a narrow band of retouching along the right edge. There are cracks in areas of thicker paint application, as well as localized areas of drying cracks apparently related to the layering of the paint, especially in areas of reworking such as the matador and the muleta. There are remnants of paper from two previous applications of paper edge strips in places around the edges. In two places, original brushwork overlaps paper fragments from the earlier edge strips. The painting is varnished with a thin, even, saturating synthetic varnish.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

Current frame (installed 1999): The frame is not original to the painting. It is a nineteenth-century French Second Empire Neoclassical fluted scotia frame with acanthus-leaf miters. The frame is water gilded over red bole on gesso and carved and composition ornament. The gilding is burnished on the sides, top fillets, and fluted scotia with the ornament and fillet-and-cove sight edge matte gilded. The frame retains its original gilding and glue size. The carved pine molding is mitered and joined with angled dovetailed splines. The molding from the perimeter to the interior is fillet, torus with a cable ornament, scotia side, fillet, ovolo with guilloche and flower, fillet, stopped fluted scotia, ogee with leaf-and-tongue ornament, and fillet with cove sight (fig. 9.70). The frame’s section width is 13.1 cm (5 1/8 in.).

Previous frame (installed by 1960; removed 1999): The painting was previously housed in a Louis XIII convex frame (fig. 9.71).

Previous frame (installed by 1933; removed by 1960): The painting was previously housed in a late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century Louis XIV ogee frame with swept sides and foliate rocaille cartouches, a hollow frieze, and an egg-and-dart sight molding. The frame had an independent fillet and cove liner (fig. 9.72).

Previous frame (1884; removal date unknown): The painting was previously housed in a nineteenth-century French Louis XIV Revival convex frame with deeply cast plaster acanthus-leaf corners and foliate ornament; a deep plain hollow and ogee-leaf tip sight; and an independent fillet and cove liner.

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Sold by the artist, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Jan. 1872, for 500 francs.

Transferred from Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, 1887.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York at the American Art Gallery, New York, Feb. 21–23, 1888, lot 147, for $435.

Acquired by Isaac Cook, Jr., New York, by Dec. 30, 1909.

Sold by Isaac Cook, Jr., New York, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Mar. 16, 1910, for 27,500 francs.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, Dec. 16, 1911, for $12,000.

By descent from Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), to his wife, Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago.

Bequeathed by Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson (died 1937), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1937.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Stock (1868–83): no. 970

Deposit Durand-Ruel, New York: no. 7562

Durand-Ruel, New York: no. 3379

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel, [New York], A 1107

Other Documentation

Lochard number 317

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Number

Location: stretcher (on top of brown paper)

Method: handwritten script

Content: 37.1019 (fig. 9.73)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: Dubourg (fig. 9.74 and fig. 9.75)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 2 [encircled] (fig. 9.76)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: O’BRIEN / 65483 / CHICAGO (fig. 9.77)

Label

Location: frame

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: GILL & LAGODICH / FINE PERIOD FRAME GALLERY / GILDING RESTORATION STUDIO / HAND-CARVED REPLICAS / 108 READE STREET / NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10013 / TEL (212) 619-0631 / FAX (212) 285-1353 / G&L FRAME INVENTORY NO: 3696 (fig. 9.78)

Number

Location: frame

Method: handwritten script

Content: 8 – 7 – 7 (fig. 9.79)

Label

Location: frame

Method: printed label

Content: […]SON CH.[…]IOT / VEU[…]ETITOT / Place […] DIJON / Glaces ric[…], des p[…] / modèles, Encad[r]ements dorés, in[…] / or et faux bois, Poli et étamage de g[…] / miroirs fantaisie en tous genres, Atelie[r] / spécial de dorure, Restaurations de[g…]es, / cadres, meubles et tableaux anciens. / GRAND CHOIX DE GRAV[…]S / Photogravures et Lith[…]es / 14 – Imp. régionale, 7, Petite rue du Cha[…]au, Dijon. (fig. 9.80)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist / Manet “Bullfight” / title / 1937.1019 / medium / credit / acc.# (fig. 9.81)

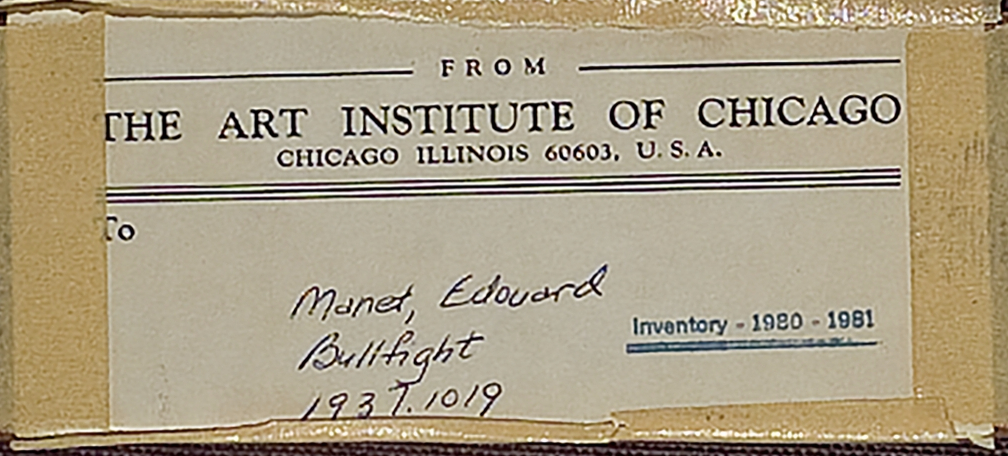

Pre-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script and green-ink stamp

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / TO / Manet, Edouard / Bullfight / 1937.1019

Stamp: Inventory – 1980–1981 (fig. 9.82)

Post-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher (on top of brown paper)

Method: green-ink stamp

Content: Inventory – 1980–1981 (fig. 9.83)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: THE NATIONAL GALLERY [Logo] / Trafalgar Square London WC2N 5DN / Telephone 071-839 3321 / EXHIBITION: Manet and the Execution of / Maximilian / NUMBER: X.265 / ARTIST: Manet / TITLE: “Bullfight” / OWNER: The Art Institute, Chicago (fig. 9.84)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: [Logo] / Exposition : Manet/Velàzquez. La manière espagnole au XIXème siècle / Musée d’Orsay, Paris [space] du 16 septembre 2002 au 5 janvier 2003 / Titre de l’oeuvre : Combat de taureaux / Auteur : Manet [space] No de Catalogue 89 / Propriétaire : Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 9.85)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: The Metropolitan Museum of Art / The French Taste for Spanish Painting (3/4/03 to 6/8/03) / Art Institute of Chicago / Edouard Manet / Bullfight / SL.1.2003.19.4 / Cat. No.: 148 (fig. 9.86)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, films scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; University of Amsterdam; and Radboud University, Nijmegen. The digital X-ray detail was recorded using a Konica Minolta Regius Σ imaging plate (FP-1S) and a Konica Minolta Direct Digitizer Regius ΣII computed radiography scanner with ImagePilot software set on high image processing intensity.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Normal-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

High Resolution Visible Light

Sinar P3 with Sinarback eXact.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

Sinar P3 with Sinarback eXact (PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter and B+W F-PRO filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs: Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with Rhodium tube.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) and a Hitachi solid-state BSE. Analysis was performed at the Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.