Cat. 24

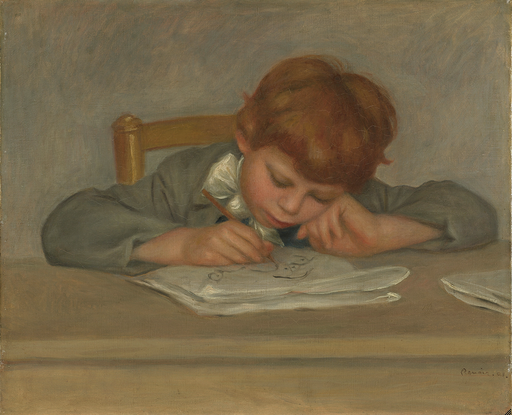

Jean Renoir Sewing

1899/1900

Oil on canvas; 55.4 × 46.3 cm (21 3/4 × 18 1/4 in.)

Signed and dated: Renoir. (lower left, in brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1937.1027

Renoir in Magagnosc

In his biography of his father, Jean Renoir wrote, “I remember quite clearly all the preparations for the picture now in the Art Institute in Chicago, showing me sewing. It was executed at Magagnosc, near Grasse, where my parents had rented a pretty villa on the side of the mountain.” Indeed, in January 1900 Renoir’s wife, Aline; their five-year-old son, Jean; his nanny, Gabrielle; and “La Boulangère” (Marie Dupuis, who served as both family cook and artist’s model) joined the artist at the Villa Raynaud, near Magagnosc, for a four-month stay. Renoir had been spending winters in the south of France for many years, seeking in the milder climate some relief from his advancing rheumatoid arthritis. His residence in Magagnosc followed treatment for this illness in Aix-les-Bains in the Savoie, which he procured on the advice of his doctor, Émile Baudot.

The year 1900 would prove a remarkable one for the artist. In January the Bernheim-Jeune brothers, Gaston and Josse, held their first Renoir exhibition of sixty-eight works in Paris; by March Renoir promised his art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, a crate of paintings for an exhibition planned the next year; and in May and June eleven of the artist’s paintings were featured at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. That August the artist was officially recognized by the French State with the prestigious Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. He then returned to Magagnosc with his family in November, where they apparently stayed until March or April 1901.

Jean Renoir as Artist’s Model

Jean was accustomed to modeling for his father (see, for example, fig. 6.29 [Dauberville 2377]), though when the boy was little Renoir would often wait until he was occupied with something on his own and then take the opportunity to capture the moment. As Jean later recorded, these impromptu sessions gave rise to paintings of him eating soup, playing with toy soldiers, or building blocks, looking at a picture book, and other such scenes of daily life.

In January 1900 Renoir presented a portrait of Jean (fig. 6.31 [Dauberville 2380]) to the mayor of Limoges, the city of the artist’s birth. Signed and dated 1899, this simple bust portrait seems a conservative choice for the second French public collection in which the renowned Impressionist painter was to be represented. However, Renoir ably demonstrates his skill as a colorist in this portrait, playing up the correspondence between Jean’s red-gold hair and the pink tones of the blouse, both of which contrast with the blue collar and the boy's large blue eyes.

Compared to the Limoges portrait, Jean Renoir Sewing shows the artist’s son more informally dressed in a pink smock. Here Jean is perhaps posed near a window, as he appears to be bathed in natural light. The boy is shown sewing, a subject Renoir usually reserved for female sitters in genre paintings. Jean later recalled that it was Gabrielle who suggested that, to keep himself occupied during this particular modeling session, he should sew a satinette coat for the painted tin camel given to him by Monsieur Raynaud, the owner of the villa in Magagnosc.

The Renoirs followed the bourgeois fashion of letting the hair of preschool-age boys grow long over the shoulders, and the artist took advantage of the opportunities for coloristic exploration afforded by his son’s abundant red-gold hair. While Jean’s parents thought nothing of tying the boy’s hair back with a brightly colored ribbon to keep it out of his eyes, Jean’s recollection of being teased about his long hair by the neighborhood children suggests that the Renoir family may have taken the fashion to an extreme. In Jean Renoir Sewing, Renoir combined a variety of earth tones with touches of rose and bright yellow highlights to give Jean’s hair an angelic glow, and the yellow of the bow serves as a striking accent.

The entire household was present in 1901 when seven-year-old Jean’s hair was cut, as required for his entry into the Jesuit Collège Sainte-Croix in Neuilly that autumn. This dramatic rite of passage in which Jean lost the beautiful red-gold locks that had obsessed his father did not diminish Jean’s charm as a young boy nor exempt him from further modeling duties. In October 1901 Renoir and his family moved into an apartment at 43, rue Caulaincourt, in Montmartre, where Jean remembered posing most frequently. One of the paintings executed there showing Jean with his schoolboy look, Jean Renoir Drawing (fig. 6.44 [Dauberville 2389]), is dominated by subdued earth tones—a concession, perhaps, to the reality that Jean’s hair could no longer inspire a colorist’s vivid palette.

A Second Version of Jean Renoir Sewing

In its dual role as portrait and genre scene, Jean Renoir Sewing was planned as a more ambitious undertaking than the smaller bust portrait of Jean that Renoir gave to Limoges. The artist chose a half-length format to portray his subject. The additional area of a no. 10 portrait (figure) standard-size canvas enabled him to accommodate the arms, the hands, and a larger portion of the torso. The positions of the arms anchor the composition, and apparent alterations to the arms, including narrowing the right sleeve to make it less voluminous and moving the left arm slightly outward (see Application/technique and artist’s revisions in the technical report), served to strengthen the triangular symmetry of the pose. Renoir originally painted a larger bow, as in the Limoges portrait. The long, animated tails are still visible through the blue background paint used to cover them. Reducing the size of the bow further enhanced the triangular line of the composition.

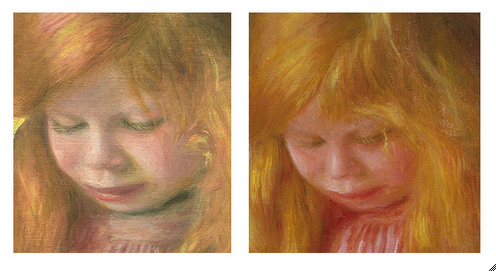

There exists a second version of Jean Renoir Sewing (fig. 6.43 [Dauberville 2375]), which now resides in the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne. Renoir made multiple versions of a painting on a few occasions. In 1876 he made a second version of Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876; Musée d’Orsay, Paris [Daulte 438; Dauberville 211]) that was acquired by the collector Victor Chocquet, and in 1892 he prepared five variations of Girls at the Piano for selection by Henri Roujon, the Minister of Fine Arts. There is no record of why Renoir felt compelled to paint two versions of Jean Renoir Sewing. The two paintings are generally thought to have been executed at about the same time. Both canvas supports are coated with two layers of commercially prepared ground and have very similar thread counts and variations in weave density, indicating that the canvases were probably purchased at the same time (see Weave in the technical report). Both paintings also feature numerous adjustments and compositional changes, which would not be expected in a later copy.

A close stylistic comparison of the two paintings reveals subtle differences. The poses vary slightly, and revisions indicate that the artist altered the composition in both works, specifically in the bow, hair, sleeves, hands, chin, and chair. Both also show evidence of similar techniques, such as scraping, repainting, and wrinkling of the paint due to the application of more paint before the previous layer had dried. Variations in brushwork, color, and modeling can also be seen in both works, for example, in the face and the hair around it (fig. 6.30). In the Chicago version Renoir used cooler tones to indicate shadows under the chin and around the nose and eyes. The warmth of these shadows in the Wallraf-Richartz version minimizes their abruptness, and as a result the details of the face appear more evenly blended and less sharply delineated. In the Chicago painting, the shadows are more saturated and there is greater red tonality in the smock and hair. In comparison, the flesh tones in the Wallraf-Richartz version appear subdued to a pinkish tone, with an overall lighter tonality in the face and smock. The backgrounds, too, are different; Renoir applied thin, translucent blue layers across the background in the Wallraf-Richartz painting, leaving some of the white ground visible for a watercolor-like appearance. In the Chicago version the background is slightly darker and more opaque, with less light on the right side of the picture. Perhaps the most striking difference between the portraits is the intensity and angle of the light: the Chicago version exhibits directional, almost raking light from the top left; in the Wallraf-Richartz version the figure is bathed in even, almost ambient light. The overall effect of the execution in the Wallraf-Richartz version is a more harmonious relationship between the figure and the ground.

Renoir as Children’s Portraitist

Throughout his career Renoir excelled at painting children, from the portrait of the nine-year-old Romaine Lacaux in 1864 (fig. 14.47 [Daulte 12; Dauberville 489]) to the inclusion of children in adult situations or genre paintings, such as Two Sisters (On the Terrace) (1881; cat. 11), which enhances the subject’s theme of lighthearted leisure. Renoir’s great gift as a painter of children was recognized at his first retrospective exhibition in April 1883, organized by Durand-Ruel, where the first gallery was devoted exclusively to images of children. Despite critical approval, not everyone understood Renoir’s portraits of children. The artist’s friend and patron Paul Berard claimed that Renoir’s 1883 portrait of his daughter Lucie (cat. 16) left visitors to his apartment with a feeling of unease, in spite of its privileged location in a prime spot in his study and its presentation in a specially made frame. Unlike children whose portraits were painted in the more traditional styles of the time, whose likenesses would perhaps have been more pleasing to Berard’s visitors, Renoir’s children occupy a world apart, a utopian realm free of adult expectations or responsibilities, an Impressionist world filled with light and color.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Renoir began this portrait of his son Jean on a no. 10 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size [glossary:canvas] that was [glossary:commercially primed] with a double preparation; now darkened from age and treatment, the ground was probably once a soft or semitranslucent white. A few lines visible in the infrared images suggest that the artist began with a contour sketch, possibly in charcoal or black chalk, but subsequent rubbing and scraping of the paint layers obscured the extent of this process and the exact nature of the [glossary:underdrawing] material. The work is marked by changes and reconsiderations, as Renoir repeatedly scraped back and painted over previous compositional choices throughout. In many places, the surface exhibits a strange, pockmarked texture that is the result of this scraping process: the paint covering the high points of the canvas was preferentially removed, leaving hard-edged, circular depressions. Elsewhere the high medium content and repeated applications of paint are evident in widespread wrinkling, especially in Jean’s hair. Renoir made numerous changes to the figure, including the placement of the hands and fingers, the curve of the arms and the volume of the sleeves, the length and arrangement of the child’s curls and bow, and the angle of his face. The painting is signed by the artist at the lower left and is currently lined and varnished.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 1.2).

Signature

Signed and dated: Renoir. (lower left, in brown paint) (fig. 1.1, fig. 5.11).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions of the canvas were approximately 55 × 46.3 cm, according to 1968 pretreatment measurements. This closely corresponds to a no. 10 portrait (figure) standard-size (55 × 46 cm) canvas.

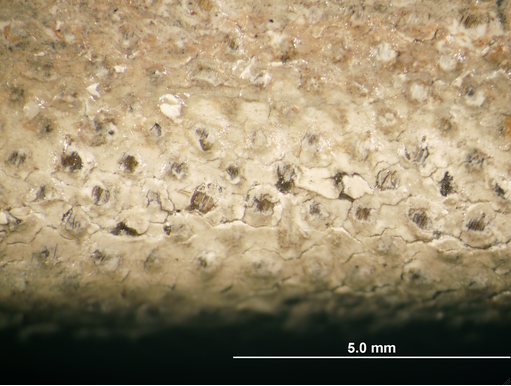

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 20.1V (0.5) × 16.4H (0.6) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

[glossary:Cusping] corresponds to the placement of the original tacks.

Stretching

Current stretching: When the painting was lined in 1972, the original dimensions were increased slightly on all sides (see Conservation History).

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the [glossary:X-ray], the original tacks were placed approximately 5–7 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Four-member redwood [glossary:ICA spring stretcher]. Depth: 2.4 cm.

Original stretcher: Five-member, blind mortise-and-tenon stretcher with a horizontal [glossary:crossbar]. Depth: Approximately 1.4 cm.

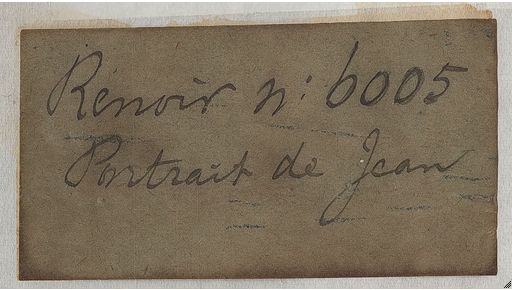

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

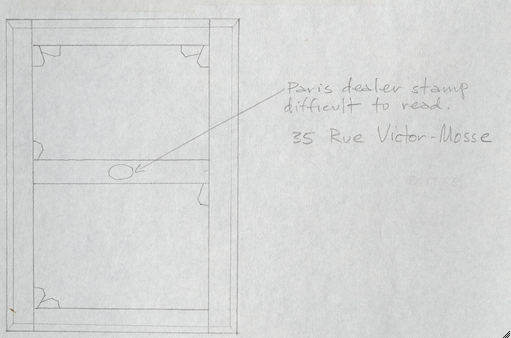

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); partial transcription in conservation file

Method: ovular stamp/stencil

Content: 35 Rue Victor-Mosse [sic] (fig. 1.3)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

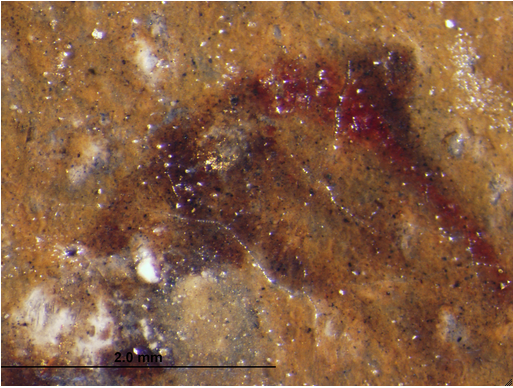

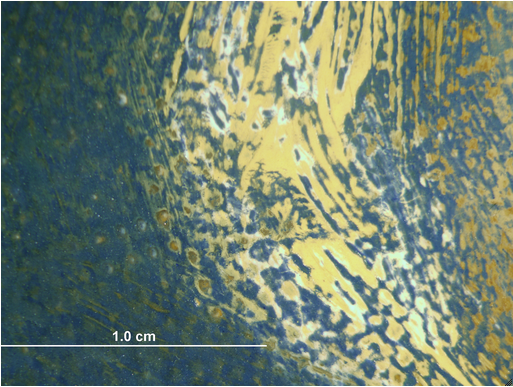

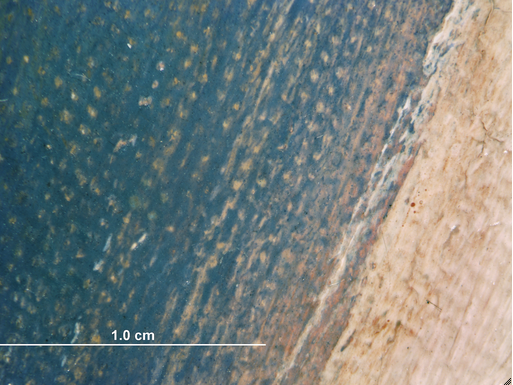

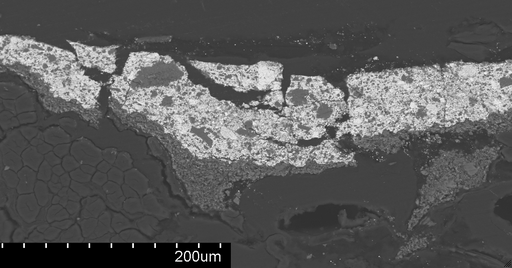

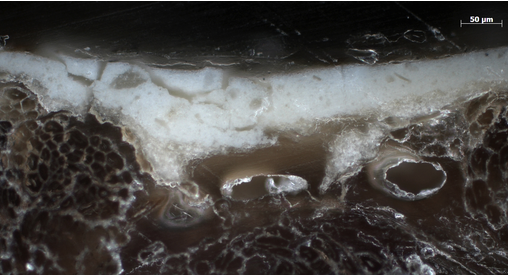

The [glossary:ground] is a two-layer commercial preparation that extends to the edges of the [glossary:tacking margins]. The first layer varies in thickness (approximately 5–60 µm) and somewhat fills the interstices of the weave, while the second is thicker (approximately 20–85 µm) and moderately coats the high points of the canvas (fig. 1.4).

Color

Due to saturation by both the ground medium and the [glossary:wax-resin lining] material, the first ground layer, revealed mostly over the thread tops in areas of abrasion, appears translucent under [glossary:stereomicroscopic examination]. This layer has a whitish haze and is heavily influenced by the color of the underlying canvas. The second ground layer appears almost beige; this is largely the combined effect of the darkening of the medium, the accumulation of grime, and saturation from the lining material and varnish, as almost no colored particles are visible under stereomicroscopic examination (fig. 6.38, fig. 6.37). Additionally, the perception of the translucent layers is affected by the color of the canvas, and the ground appears warmer as a result. It is likely that the ground was a brighter, but still soft, semitranslucent white during the artist’s lifetime (fig. 6.14).

Materials/composition

The first ground layer is composed primarily of calcium carbonate (chalk) with traces of complex magnesium- and aluminum-containing silicates, or clays. The second ground layer is a mixture of lead white and calcium carbonate (natural chalk with associated microfossils), with traces of associated complex silicates, silica, and alumina. The [glossary:binder] is estimated to be [glossary:oil].

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

The infrared image shows a few stray lines in a thin, dark medium that could be an underdrawing, but Renoir’s technique of scraping back the paint to make compositional changes obscured the nature of these lines as well as their prevalence (fig. 5.12). The lines appear predominantly in the figure’s lower curls and around his eyes.

Medium/technique

The infrared image suggests that the possible underdrawing consists of a very thin, dark medium, possibly charcoal or black chalk. It is, however, unclear at this time whether the material was applied in a dry or fluid medium.

Revisions

There is no evidence of changes in the compositional planning stage (see Paint Layer).

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

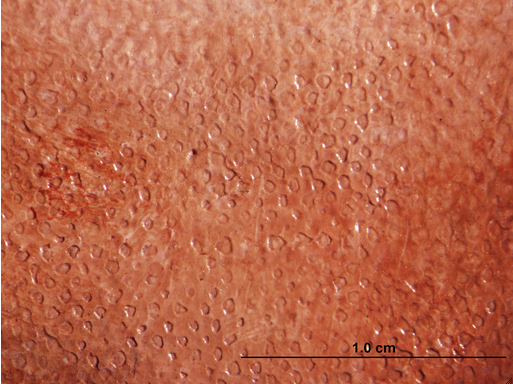

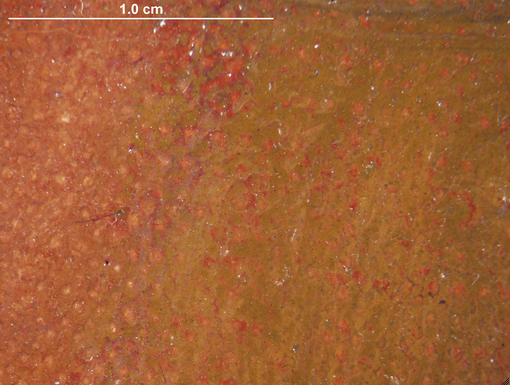

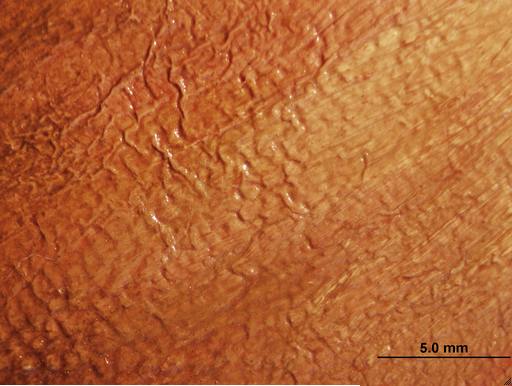

Renoir made numerous changes throughout the execution of this portrait of his son Jean, constantly painting over previous work, scraping back paint, and repainting. In many cases the sequence of changes is not immediately apparent; it is, however, clear that the artist made numerous small adjustments to the figure’s arms, smock-like garment, fingers, hair, and bow, as well as to the angle of his head. Repeated scraping to remove earlier compositional choices resulted in a strange, almost pockmarked surface texture in which the high points of the canvas weave form the low points in the painting: as the palette knife cut across the surface, the paint on the high points of the canvas was preferentially removed, while that in the interstices remained and was built up above the neighboring thread tops in successive layers (fig. 5.10). In other areas, Renoir used scraping to return to previous compositional choices he had painted out, as seen in the child’s hair bow (fig. 5.5). The artist also varied the medium content and the working of his paint, employing extra oil and using a soft brush for the flat first layers of the child’s hair, the flesh tones, and the blue background; thicker, paste-like paint and stiffer, flat brushes for the highlights throughout the hair and garment; and paint thinned with spirits, which sank into the preexisting paint and canvas textures, in the deep red and brown shadows in the garment.

The infrared, [glossary:transmitted-infrared], and X-ray images indicate that Renoir moved Jean’s arms many times, subtly adjusting them to bring the right arm closer to the body, while moving the left arm slightly away. The X-ray and transmitted-infrared images most clearly show the changes related to the figure’s right sleeve and arm: originally the sleeve was wider, extended further to the left, and belled out lower. Although scraped back and covered with blue background paint, some of the wider profile is still visible along the right edge of the sleeve (fig. 5.7). The child’s hands were at one point slightly to the right of their current position, with his left fingers more curled, and the fabric he sews covering more of his lap. Some hints of the fingers’ previous position can be seen under normal viewing conditions, especially around the thumbs (fig. 5.8). Jean’s left sleeve originally appeared slightly less voluminous and may have had a few more folds along the edges, as opposed to the generally round outline in the final composition. In addition to scraping back paint to adjust the volume and position of the sleeves, Renoir periodically reinforced the new contours with additional highlights. Stereomicroscopic examination of the surface also indicates that the child’s garment extended farther to the right near the bottom edge but was scraped back by the artist and painted over with yellow-brown paint (fig. 5.9). The chair, as well as the brown area on the lower left, may have been added later, as the blue background is visible beneath them in many areas, including to the immediate right of Jean’s shoulder. On the lower left, the volume of the garment was adjusted again and made larger, so that it covers both the blue background and earlier earthy browns.

Renoir also adjusted the angle of Jean’s face, as well as the volume and arrangement of his curls and the size and shape of the yellow bow in his hair. Faint underdrawing lines visible in the infrared image suggest that the curls were slightly longer initially; the infrared and transmitted-infrared images also indicate that the hair had slightly less volume on the right and more on the left and near the crown of the head. To the right of the head, thinly painted, gauzy curls were added on top of the preexisting background. On the left, the bow was adjusted and the hair was brought in more tightly toward it. The size and arrangement of the yellow bow may have been changed several times; it appears largest in the X-ray, with a prominent, round loop on the left and a long, diagonal piece of ribbon extending down to the level of the child’s chin. As the artist rearranged Jean’s curls to obscure more of the bow, he partially scraped back some of the earlier choices, then brought in additional blue background paint. Ultimately Renoir settled somewhere in the middle, scraping back some of the added blue paint to reveal the upper loop of the bow. The hair itself appears thickly painted and was adjusted numerous times. The extent of the wrinkling in the hair suggests that the artist did not scrape in this area but merely continued to add paint on top of still-soft, medium-rich paint layers to achieve the desired arrangement; the bright orange and yellow highlights throughout the hair, as well as the added ear on the right, show the most wrinkling (fig. 5.13).

Jean’s head appears slightly wider and perhaps more tucked toward his chest in the transmitted- and reflected-infrared images. His collar started lower and may have been more substantial, with a stiff, diagonal edge visible on the left. Other features of his face, especially the mouth, were probably adjusted as Renoir changed the angle of the head; the infrared images seem to show pentimenti in this area, but the specific nature of these changes is unclear.

Painting tools

Flat and round brushes with strokes up to 0.5 cm wide; very fine, soft brushes used for details such as the eyelashes; [glossary:palette knife] for scraping.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, cobalt blue, Naples yellow, iron oxide yellow, terre verte, vermilion, red lake, and bone black.

Pigment analysis suggests that the mixtures vary greatly in complexity, with some, such as those used in the child’s garment, quite simple. Three separate samples of the garment indicate the presence of vermilion, red lake, and lead white in various combinations. The flesh tones, similarly, are predominantly vermilion and lead white with possible additions of Naples yellow and trace amounts of black. The gray area of the fabric Jean sews, however, is a complex mixture including lead white, Naples yellow light, bone black, iron oxide yellow, cobalt blue, and vermilion.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting has a [glossary:synthetic varnish] with residues of [glossary:natural-resin varnish] in the interstices of the paint layer. The natural-resin varnish was applied at an unknown date and removed in 1972. It is unclear whether Renoir himself would have varnished this painting.

Conservation History

The painting’s condition was first documented in 1955, when it was described as having [glossary:rebate] abrasion around the perimeter and very thin paint overall. In September 1956, abrasion around the edges and paint losses along the right edge from contact with the frame rebate were noted, and the painting was keyed out to alleviate canvas buckling. At this time a white substance was seen to be accumulating in the interstices along the figure’s left elbow. In 1968, prior to treatment, the painting was more thoroughly examined and found to be attached to a five-member stretcher with a horizontal crossbar, and to have a discolored natural-resin varnish and an abraded, overpainted surface. The painting was grime cleaned, its surface coatings and retouching were thinned, and a synthetic varnish was applied. The work was treated again in 1972 to address both structural and aesthetic issues. Much of the garment and the fabric being sewn was extremely abraded and still much overpainted. During this treatment, grime and varnish were removed; some retouching was removed (particularly on the figure), while some was left intact; and the work was faced with mulberry-fiber paper and starch paste in preparation for [glossary:lining]. The old stretcher was discarded when the work was wax-resin lined, and the lined painting was tacked to a four-member redwood ICA spring stretcher. The work was inpainted and given a synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, inpainting, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, and a final coat of AYAA).

Condition Summary

The painting is in stable condition, wax-resin lined and planar; the texture of the [glossary:weave] is visually pronounced due to both the artist’s scraping technique and damage from the lining procedure. The canvas along the [glossary:foldover] edges is splitting on both sides but appears to be held in place by the lining at this time. An open tear just inside the right foldover along the chair back is also held by the lining and has associated fill and [glossary:retouching] material. The work has pronounced rebate abrasion around the perimeter from contact with the frame, especially along the sides and bottom edge. There are spots of retouching throughout to address areas of heavier abrasion, and some areas of matte retouching in the figure’s hair on the right. There may also be remnants throughout the painting of preexisting [glossary:overpaint] that was not removed in earlier treatments. The painting has a relatively even, semiglossy synthetic varnish, with light residues of natural-resin varnish in areas of [glossary:impasto].

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame appears to be original to the painting. It is a French, late-nineteenth-century, Durand-Ruel, Louis XVI Revival, gilt architrave frame with cast ribbon-and-stave ornament and beaded fillet sight molding. The frame has oil and water gilding over bole on cast plaster and gesso. The bole color varies throughout: there is red bole on the perimeter molding, cast ribbon-and-stave ornament, and beaded fillet sight molding; and orange bole on the fillet face. The gilding is toned with a casein or gouache raw umber [glossary:wash] with a gray overwash and whitish-gray flecking. At some point in its history, the frame was cleaned, removing most of the original surface and toning and damaging portions of the gilding. The pine molding is mitered and nailed. At some point the original verso was planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance, a back frame was added, and all back and interior surfaces were painted. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is fillet; cove side; fillet face with cast ribbon-and-stave ornament; and beaded fillet sight molding (fig. 5.6).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Possibly acquired from [unknown] by Durand-Ruel, Paris, by Apr. 1912.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, 1914.

By descent from Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), Chicago, to his wife, Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago.

Bequeathed by Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson (died 1937), to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1937.

Exhibition History

Paris, Durand-Ruel, Exposition de tableaux par Renoir, Apr. 27–May 15, 1912, cat. 14, as Portrait de Jean, 1900.

Paris, Durand-Ruel, Portraits par Renoir, June 5–20, 1912, cat. 16, as Portrait de Jean Renoir, 1900.

Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, Some Modern Primitives: International Exhibition of Paintings and Prints, Summer 1931, July 2–Aug. 16, 1931, cat. 72.

Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art, Paintings by French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, Nov. 7–Dec. 12, 1937, cat. 23 (ill.).

Los Angeles County Museum, Pierre Auguste Renoir 1841–1919: Paintings, Drawings, Prints and Sculpture, July 14–Aug. 21, 1955, cat. 58 (ill.); San Francisco Museum of Art, Sept. 1–Oct. 2, 1955.

Denver Art Museum, The Turn of the Century: Exhibition of Masterpieces, 1880–1920, Oct. 1–Nov. 18, 1956, cat. 38.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 69 (ill.).

Birmingham (Ala.) Museum of Art, Fifty Years of French Painting: The Emergence of Modern Art, Feb.1–Mar. 30, 1980, cat. 14 (ill.).

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, June 27–Sept. 14, 1997, not in cat.; Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 17, 1997–Jan. 4, 1998; Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, Feb. 8–Apr. 26, 1998 (Chicago and Fort Worth only). (fig. 6.25)

Sakura, Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art, Runowāru ten/Renoir: Modern Eyes, Apr. 3–May 16, 1999, cat. 67 (ill.); Sendai, Miyagi Museum of Art, May 25–July 4, 1999; Sapporo, Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, July 15–Aug. 29, 1999.

Columbia (S.C.) Museum of Art, Renoir!, Apr. 25–Oct. 1, 2007, no cat.

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, Impressionismus: Wie das Licht auf die Leinwand kam, Feb. 29–June 22, 2008, cat. 155 (ill.); Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, as Impressionismo: Dipingere la luce, le tecniche nascoste di Monet, Renoir, e van Gogh, July 11–Sept. 28, 2008 (Cologne only).

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 32 (ill.).

Selected References

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Exposition de tableaux par Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1912), p. 4, no. 14.

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Portraits par Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1912), p. 4, no. 16.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Notes,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 9, 3 (Mar. 1, 1915), p. 40.

Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, Some Modern Primitives: International Exhibition of Paintings and Prints, Summer 1931, exh. cat. (Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, 1931), cat. 72.

Claude Roger-Marx, Renoir (H. Floury, 1933), p. 157.

Michel Florisoone, Renoir (Hypérion, 1937), pp. 69 (ill.), 166. Translated by into English by George Frederic Lees as Renoir (Hyperion, 1938), pp. 69 (ill.), 166.

Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art, Paintings by French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, exh. cat. (Toledo Museum of Art, 1937), cat. 23 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Exhibition of the Ryerson Gift,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 32, 1 (Jan. 1938), p. 4.

Josephine L. Allen, “The Entire Ryerson Collection Goes to the Chicago Art Institute,” Art News 36, 21 (Feb. 19, 1938), p. 11.

Art Digest 16, 17 (June 1, 1942), p. 15 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Notes,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 42, 2, pt. 1 (Feb. 1948), p. 28 (ill.).

Peyton Boswell, “Comments,” Art Digest 23, 10 (Feb. 15, 1949), p. 8 (ill.).

Dorothy Bridaham, Renoir in the Art Institute of Chicago (Conzett & Huber, 1954), pl. 8.

Los Angeles County Museum and San Francisco Museum of Art, Pierre Auguste Renoir, 1841–1919: Paintings, Drawings, Prints, and Sculpture, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum, 1955), pp. 17, cat. 58 (ill.); 52.

Denver Art Museum, The Turn of the Century: Exhibition of Masterpieces, 1880–1920, exh. cat. (Denver Art Museum, 1956), cat. 38.

Bruno F. Schneider, Renoir (Safari, [1957]), p. 79 (ill.). Translated into English by Desmond and Camille Clayton as Renoir (Crown, 1978), p. 79 (ill.).

Raymond Cogniat, Renoir: Enfants (Fernand Hazan, 1958), pl. 3.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 398.

Jean Renoir, Renoir (Hachette, 1962), p. 390. Translated by Randolph and Dorothy Weaver as Renoir: My Father (Little, Brown, 1962), p. 391.

François Daulte, “Renoir: Son oeuvre regardé sous l’angle d’un album de famille,” Connaissance des arts 153 (Nov. 1964), p. 78, fig. 16.

Thomas Willis, “Renoir on Renoir,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 28, 1973, p. K55 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 164–65, cat. 69 (ill.); 184.

Roger Ebert, “Renoir’s Last, Fond Testament,” Chicago Sun Times, Aug. 30, 1974, p. 49 (ill.).

Walter Pach, Auguste Renoir: Leben und Werk (M. DuMont Schauberg, 1976), pp. 175; 183, fig. 75.

Birmingham (Ala.) Museum of Art, Fifty Years of French Painting: The Emergence of Modern Art, with a text by Barbara Chenoweth Shelton, exh. cat. (Birmingham Museum of Art, 1980), cat. 14 (ill.).

A. James Speyer and Courtney Graham Donnell, Twentieth-Century European Paintings (University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp. 12; 66, cat. 3E9; microfiche 3, no. E9 (ill.).

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 69; 72; 102, pl. 21; 111.

Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art, Miyagi Museum of Art, and Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Runowāru ten/Renoir: Modern Eyes, exh. cat. (Hokkaido Shinbunsha, 1999), pp. 160–61, cat. 67 (ill.).

Gail Carolyn Sirna, In Praise of the Needlewoman: Embroiderers, Knitters, Lacemakers, and Weavers in Art (Merrell, 2006), pp. 138–39 (ill.).

Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Impressionismus: Wie das Licht auf die Leinwand kam, exh. cat. (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud/Skira, 2008), pp. 144; 147, fig. 155; 235. Translated as Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Painting Light: The Hidden Techniques of the Impressionists, exh. cat. (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud/Skira, 2008), pp. 147, ill. 155; 151; 235.

Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Impressionismo: Dipingere la luce, le tecniche nascoste de Monet, Renoir, e van Gogh, ed. Monica Maroni, exh. cat. (Foundazione Palazzo Strozzi/Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Foundation Corboud/Skira, 2008), pp. 144; 147, ill. 155; 235.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), p. 79, cat. 32 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), p. 79, cat. 32 (ill.).

Katja Lewerentz, “Brief Report on Technology and Condition: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jean Renoir Sewing,” in Research Project: Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud/University of Applied Sciences, Cologne Institute for Conservation Sciences, 2008), pp. 2; 16, fig. 14 and fig. 15.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 3, 1895–1902 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2010), p. 391, cat. 2376 (ill.).

Daniel Marchesseau, Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Revoir Renoir, with contributions by Cécile Bertran, Augustin de Butler, Caroline Durand-Ruel Godfroy, et al., exh. cat. (Fondation Pierre Gianadda, 2014), p. 210 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite and black marker)

Content: 1937.1027 (fig. 6.15)

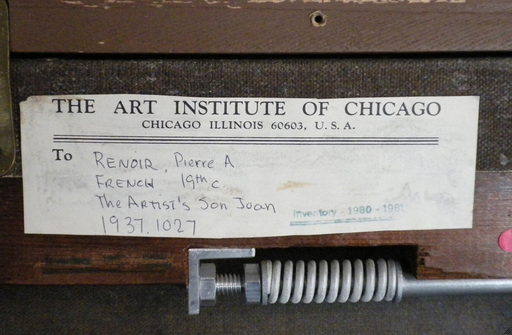

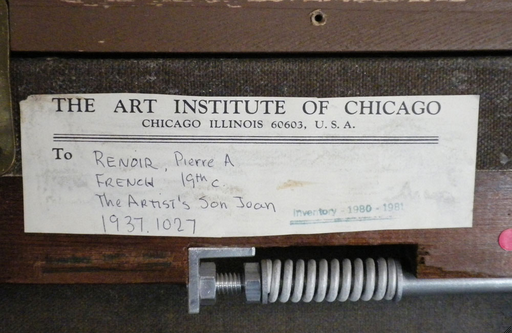

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (black pen?) on printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / To RENOIR, Pierre A / FRENCH 19th c. / The Artist’s Son Jean / 1937.1027 (fig. 6.17)

Pre-1980

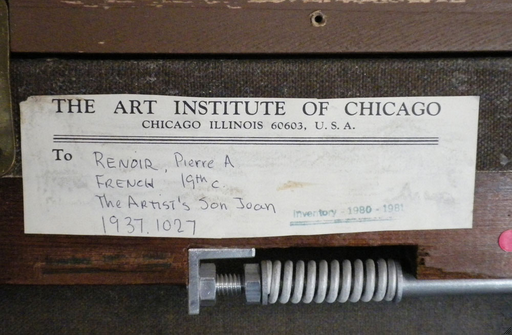

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script (ink) on brown paper label

Content: Renoir n: [b or 6]005 / Portrait de Jean (fig. 6.18)

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script (ink) on red-and-white paper label

Content: 14 / 718 (fig. 6.19)

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); partial transcription in conservation file

Method: ovular stamp/stencil

Content: 35 Rue Victor-Mosse [sic] (fig. 6.20)

Post-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher (on AIC label)

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory— 1980–1981 (fig. 6.21)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 6.22)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: Kimbell Art Museum / . . . serving the Fort Worth/Dallas metropolitan community / 3333 Camp Bowie Boulevard / Fort Worth, Texas 76107-2792 / RENOIR’S PORTRAITS: IMPRESSIONS OF AN AGE / February 8–April 26, 1998 / Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Jean Renoir Sewing, 1898 / Oil on canvas / 21-3/4 × 18-1/4" / The Art Institute of Chicago / Crate No. 53 (fig. 6.23)

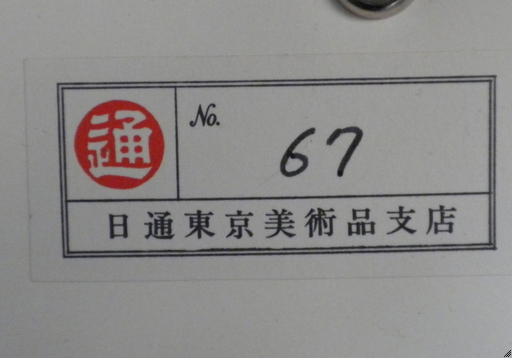

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir / title Jean Renoir Sewing / medium oil on canvas / credit / acc. # 1937.1027 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 6.26)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: [logo] No. 67 / [Japanese characters] (fig. 6.24)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (Kodak Wratten 2E filter, PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

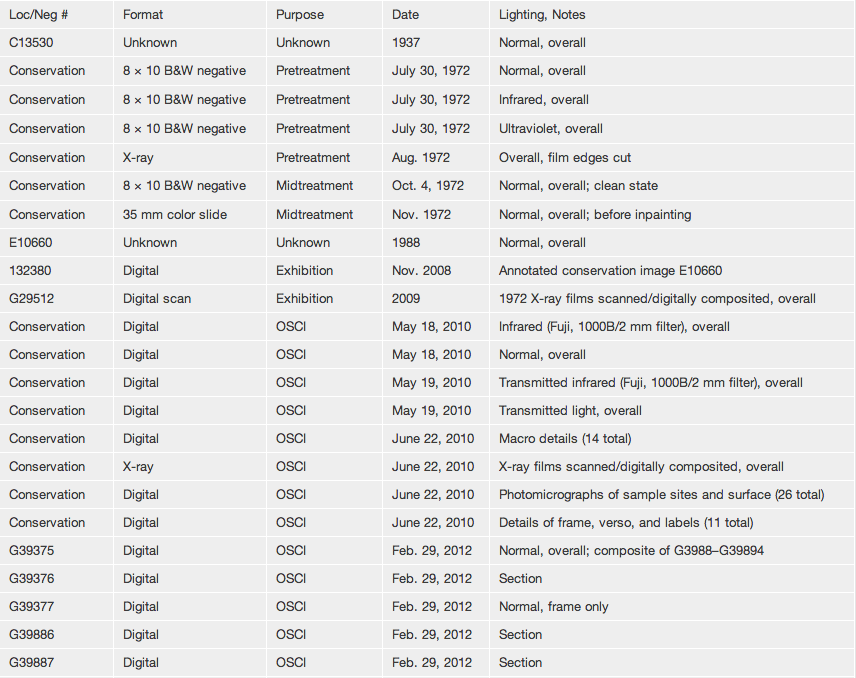

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 6.27).