Origins and Innovations

The theme of the laundress was prevalent in the visual and literary culture of middle-class nineteenth-century France. Aside from Edgar Degas, however, the Impressionists did not regularly take up this subject in their paintings of modern life; when the theme did appear in Impressionist work, it was typically “subordinated to the atmospheric surroundings.” The Laundress is indeed an anomaly in the oeuvre of Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Although he returned to the subject in the mid-1880s and later—though only a handful of times—this canvas is likely the artist’s first and only incorporation of the motif during the time when he was actively engaged with the concerns of Impressionism.

As noted by Douglas Druick, Renoir probably made The Laundress—which is signed, but not dated—after completing his illustrations for Émile Zola’s gritty novel L’assommoir, a tragic tale centered around a laundress named Gervaise Macquart, which exposed the blight of poverty and alcoholism in contemporary working-class Paris. Originally published by Renoir’s patron, Georges Charpentier, in 1877, the first illustrated edition of L’assommoir appeared the following year. At Zola’s request, Renoir created four illustrations for it. But while Zola could present his vivid narrative with words, Renoir had to find a way to visualize select scenes in a two-dimensional format. As the Art Institute’s original drawing for one of the illustrations (fig. 1.2 (cat. 5) demonstrates, the artist—using pen, brown ink, and black chalk—combined areas of shading with a web of thin, scratchy lines in order to produce a vibrating surface that teems with an almost restless energy.

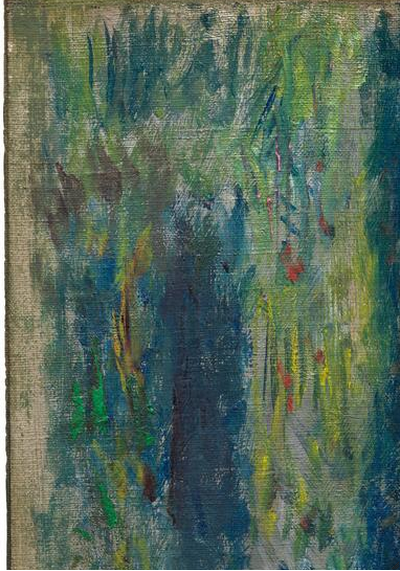

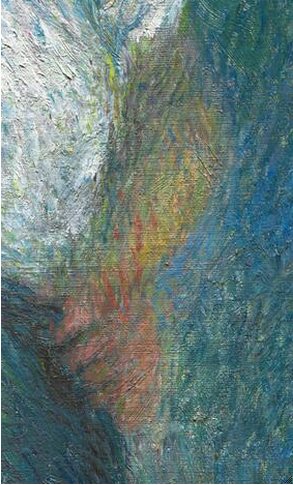

By the mid-1870s, Renoir was also creating similar effects in his paintings, as The Laundress exemplifies. Using a limited palette and a variety of techniques, he crafted a shimmering surface through a complex, built-up network of feathery brushstrokes. Combined with some areas of smooth modeling and heavy impasto, Renoir’s brushwork and use of complementary-color contrasts construct a tapestry of textures to suggest space and form. Precise contours were dissolved and details of the background were obscured as the artist decreased the density of his web of brushstrokes around the edges of the painting, allowing more of the warm gray ground layer to peek through (fig. 1.1).

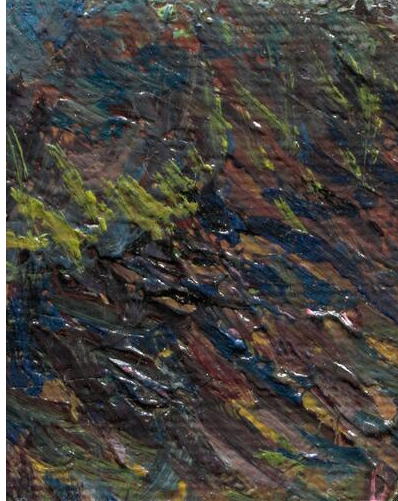

The casualness of Renoir’s brushstrokes and the confidence demonstrated by his use of [glossary:wet-in-wet] paint and his juxtaposition of individual strokes of unmixed, bold color to create areas like the figure’s hair (fig. 5.11) suggest that he executed this painting quickly. It seems that he actually developed it relatively systematically, however. The traditional triangular composition provides stability to the otherwise vibrating surface, and [glossary:X-ray] imaging indicates that the artist reinforced this form by straightening out the hemline of the model’s skirt (fig. 1.3).

Renoir also altered the posture of the model as he worked out his composition. In an earlier state of the painting, the figure was slightly more frontal, and her elbows projected out from her body more symmetrically. By adjusting her arms and both sides of her skirt, Renoir shifted her body ever so slightly to a three-quarter angle. The alteration he made to her left arm is still visible with the naked eye: flesh tones appear around the area where her wrist meets her awkwardly disproportionate hand (fig. 1.4). Renoir also lowered the height of her hair and the frothy pile of laundry beside her in order to achieve the exact balance that he was seeking.

Genre and Portraiture

There is something very deliberate and even disconcerting about the way Renoir constructed—or rather, deconstructed—his young laundress. The model for this painting was identified by François Daulte as Nini Lopez, whom Renoir employed regularly between approximately 1874 and 1880. A resident of Montmartre, the Parisian quarter where Renoir moved in the summer of 1876, Nini was characterized by critic Georges Rivière as the ideal model, for she was “punctual, serious, [and] discreet.” But while she can be identified in The Laundress, this is not a portrait; her features are generalized and dissolve into a frenzy of brushstrokes. Instead, Renoir depicted a Parisian type—in this case, a young, working-class girl.

Renoir also used Nini as his model in another, probably slightly earlier painting entitled First Step (Le premier pas) (fig. 6.14 [Daulte 347; Dauberville 250]). In this picture, however, Nini—who appears to be wearing the same blouse and skirt that she wore when posing for The Laundress—seems to embody a different type of Parisian woman. The figure that Renoir presented in Le premier pas is more refined and polished. Her facial features—though still generalized—are more delicate; using minimized brushstrokes, Renoir gave her skin a porcelain-like finish that glows like mother-of-pearl. Set in what appears to be the interior of a bourgeois dwelling—as indicated by the richly patterned, colorful carpet underfoot—she looks lovingly at a child, encouraging it to take its first steps. In many ways, Renoir made Nini a radiant, modern Madonna in this painting.

But, simultaneously, Renoir infused a degree of ambiguity in Le premier pas that makes us question this characterization. While both of Nini’s shoulders are covered, the hint of cleavage revealed as she leans toward the child highlights her sexuality; she is both demure and provocative. Her garment is simple and pulled together with the red sash at her waist, but its silhouette is not of the period. As a result of her pose, the waist appears to be cinched higher than was fashionable at the time, recalling instead coquettish Rococo fashion. Moreover, a white garment and striped socks draped over the chair suggest two possible identities for the woman. Perhaps she is the child’s mother and lady of the house awaiting the arrival of her laundress through the half-open door at right, or she might be a domestic caring for the child before undertaking her laundry chores, a woman who might even be sexually available. At this time, Renoir’s audience would have been aware that working women were known to sometimes supplement their incomes with prostitution.

Meaning and Method

As part of the Impressionist group, Renoir was interested in depicting themes of modern life, but his worldview was much more tempered than those of Zola and some of his other Naturalist and Impressionist colleagues. Even in his own era Renoir was accused of viewing the world with rose-colored glasses. As John House has explained, “Even in their original contexts, the vision of the world presented by Renoir’s canvases was escapist; his smiling world-view was an attempt to erase the fundamental anxieties of the late nineteenth century, about the breakdown of order and of the sense of social and personal identity in a society that was rapidly changing, with the emergence of industrialisation and urban capitalism.”

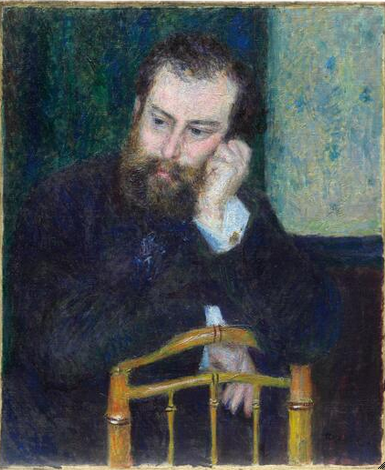

But however tame Renoir’s imagery may seem, the subtle ambiguities that he infused into Le premier pas remind us of the disconnects between class and gender in modern life and highlight the difficulty of expressing these ideas visually on a flat surface. Such uncertainties are even more exaggerated in The Laundress. Despite its similarities to Le premier pas, The Laundress is radically different in execution. The artist’s brushwork recalls the graphic, hatched quality of the drawings he made for Zola’s novel, which he also employed in a painted portrait of his friend and fellow Impressionist painter Alfred Sisley (fig. 5.12 [cat. 4]).

In large part because of the nature of the paint handling, much of the painting is impossible to read. Aside from the laundress, very few details of the composition can be definitively identified: the model stands next to a half-open door, on the other side of which is a completely illegible space; to the left of the laundress, there is only a vague impression of a yellow table or chair in what appears to be a hallway or another room; shadows on the floor do not consistently correspond with the light source coming from the upper left; and the clothes in the laundry basket—composed of swirls of paint—are not identifiable (fig. 5.10).

It is also curious that although the surface of The Laundress pulsates insistently, no substantial action is being depicted in the scene. With her flushed face, reddened hands, and basket of unfolded laundry sitting on the floor next to her, the laundress’s work is evident; this is perhaps the moment after the laundry was washed but before it was ironed, for the streaks of blue visible throughout the laundry pile may indicate that it has just been treated with bluing, a product used during laundering to enhance whitening. But in this particular moment, as Druick has observed, the laundress is not actively undertaking difficult labor, and there is no reason for her blouse to have slipped off of one of her shoulders. Renoir’s depiction of the young woman with décolletage—a motif he would feature in many other paintings of young women throughout his career—encourages a sexual, voyeuristic reading. At the same time that the young woman exhibits sexual and social vulnerability, however, she also conveys a sense of defiance. Solidly placed in the center of the composition with her hands on her hips, she has a certain resolve and confidence that suggests she is perhaps more in control of her own destiny than Zola’s laundress, Gervaise.

In the 1880s, Renoir abandoned his pursuit of urban, modern-life subjects and his broken, textured brushwork for more timeless, idyllic imagery inspired by the French countryside and the more precise forms and techniques of the Old Masters. When he picked up the theme of the laundress again nearly ten years later, his model was not Nini Lopez but rather his future wife, Aline Charigot, holding their first son, Pierre (fig. 5.5). Although his 1870s depiction speaks to the modern life of the city, Renoir—from the mid-1880s onward—related the theme of the laundress to the country, nature, hard work, and maternity.

Gloria Groom and Jill Shaw

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Renoir began this work on a warm-gray, [glossary:commercially primed] [glossary:canvas]; the color of the [glossary:priming] is visible in many areas of the background and gives the work a unifying undertone. The original size of the composition is unclear; however, it appears that the work may have been slightly larger than a standard size. Unfinished edges and individual brushstrokes that pass onto the tacking margin complicate an assessment of the painting’s original size. There is no discernible compositional planning, and the [glossary:X-ray] and infrared images show that the artist shifted the pose of the figure through a series of small alterations in the paint stages. Initially, the figure’s gaze was more frontal, her hair pulled tighter toward the top of the head, her hips pushed slightly to the right, and the hem of her skirt shorter on the sides, making her appear longer in relation to her surroundings than she does in the final composition. Renoir also made slight changes in the placement of her arms, especially her left one, some of which are visible under normal viewing conditions.

The artist used a limited [glossary:palette] and varied the size and concentration of brushstrokes throughout the work. In the figure, areas of very fine strokes of unmixed color placed side by side while still wet contrast with smoothly modeled areas and heavy [glossary:impasto] created by dragging stiff paint with a fine, soft brush. These effects are seen in the figure’s hair, skirt, and blouse, respectively. The flesh tones—primarily lead white with some vermilion and red lake—were modeled with a combination of these methods. As the artist moved from the figure to her surroundings, covering his compositional changes with strokes of background colors, the composition became less detailed, marked by broader brushstrokes and large areas of exposed ground.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 5.7).

Signature/Distinguishing Marks

Signed (lower left, in warm blue paint): Renoir. (fig. 5.8 and fig. 5.9).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

As there is no obvious painted edge, the original size of the canvas is unclear and depends largely on whether the [glossary:stretcher] is original. If this is the original stretcher, the dimensions appear to have been approximately 80.7 × 56 cm. The closest standard sizes are seascape ([glossary:marine]) 25 [glossary:haute] and [glossary:basse], which measure 81 × 54 cm and 81 × 56.7 cm, respectively.

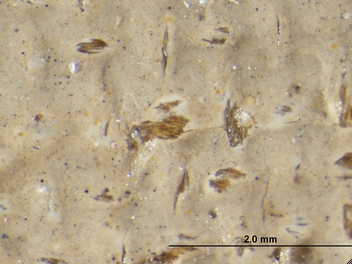

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 16.4V (0.7) × 13.8H (0.4) threads/cm. The horizontal threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the vertical threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

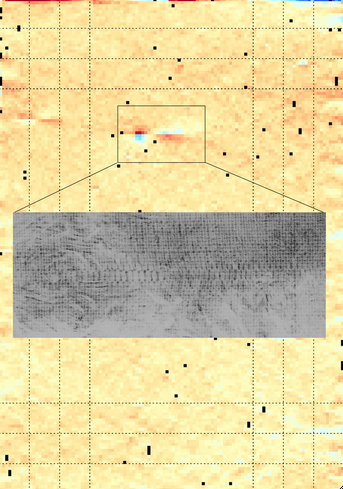

There is mild cusping along the top and bottom edges corresponding to the placement of the original tacks and some variation in thread thickness in both directions. The thread-count [glossary:weft-angle map] also indicates two places in the upper right quadrant where there was a [glossary:warp-thread repair], causing the perpendicular weft threads to distort around it (fig. 5.13).

Stretching

Current stretching: The painting was lined and restretched prior to 1956 (see Conservation History). It is unclear if the dimensions changed during this treatment. The X-ray indicates that although some of the old tack holes were reused at this time, cusping along the top and bottom edges does not correspond to current tack placement. Where the tacking margin is not obscured by paper tape, it appears the painting is currently attached with steel tacks through both the original and [glossary:lining] canvases.

Original stretching: As the edges are largely covered with paper tape, it is not clear how many times the painting was stretched. Based on cusping visible along the top and bottom in the X-ray, tacks were placed approximately 5–7 cm apart. There is almost no discernible scalloping in the weft-angle map or the X-ray for the left side and very little information on the right. Along the right edge, there is a crease approximately 0.5 cm from the edge, and a corresponding set of extra tack holes appears just beyond the current foldover. These holes are not always visible but may correspond to the faint angle changes illustrating cusping on the right edge in the weft-angle map (fig. 5.6). If this crease represents an earlier foldover, the width of the painting would be about 56 cm. Gaps between stretcher members on the verso suggest that closing the members of the current, expanded stretcher (tapping in) would accommodate this 0.5 cm.

While the height of this painting corresponds to a standard size, the width has a larger discrepancy. The edges of the composition are not clear, as they are often unfinished or have brushstrokes running over the foldover, but there is no physical evidence to suggest the work was ever smaller than 56 cm wide.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Six-member keyable mortise-and-tenon stretcher with vertical and horizontal crossbars.

The stretcher may be original to the painting, but this remains unclear, as the painting was lined, mounted to [glossary:hardboard], and restretched (see Conservation History). The stretcher’s structure and patina suggest that if it is not original to the painting, it was added early in the painting’s lifetime (fig. 6.15). Depth: 1.7 cm.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

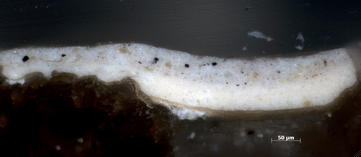

[glossary:Cross-sectional analysis] indicates a thin brownish layer of material between the paint and canvas that closely follows the canvas texture. This material is organic in nature and estimated to be glue (fig. 6.16).

Ground application/texture

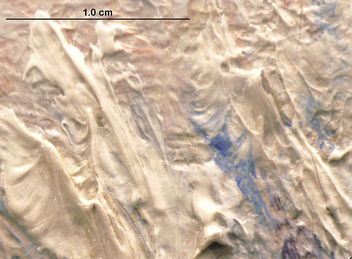

The preparation is a two-layered (or [glossary:lisse]), commercially applied [glossary:ground] that extends to the edges of the [glossary:tacking margins]. The lower layer of the ground has an approximate thickness of 10–60 µm, while the upper, toned layer is approximately 15–45 µm thick. It is smooth, somewhat fills the canvas weave, and is left visible throughout the background.

Color

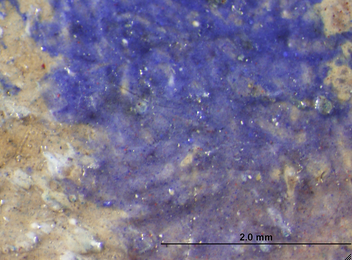

The upper ground layer is a warm gray, with black and yellow particles visible microscopically. Microscopic examination reveals the creamy white initial ground layer visible along the tops of some of the abraded threads (fig. 6.17).

Materials/composition

The commercial ground is a two-layered preparation with a whitish first layer consisting of primarily lead white with small amounts of iron oxide yellow, associated silicates, barium sulfate, and calcium sulfate. The upper layer is a warm gray made of a complex mixture of lead white, bone black, and iron oxide red and yellow, with associated complex silicates, quartz, calcium sulfate, and a trace amount of Naples yellow (fig. 6.18). Both layers are estimated to be bound in an [glossary:oil] medium.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No compositional planning visible with infrared or microscopy.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

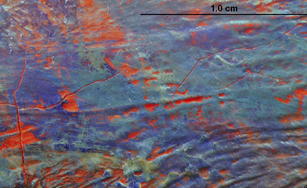

Renoir made many changes to the figure’s posture in The Laundress. There are heavy strokes of underpaint above and to the right of the figure that may mask some changes (fig. 6.19); however, a number of small later changes can still be discerned on the painting’s surface. X-ray analysis suggests that the skirt was originally placed slightly to the right, with a lower red waistband (fig. 6.20), as if the figure were shifting her weight slightly to one side. In response, the artist swung her left arm farther out to the side, while her right arm was placed slightly closer to her body (fig. 6.21). Some of the changes to the figure’s arms and hands were made quickly and remain visible on the work’s surface (fig. 6.22). The initial profile of the woman’s left arm and hand were roughly painted out with fine background strokes. Close examination of the surface reveals flesh tones visible between these fine strokes along the outer edge of the arm and hand. From the [glossary:infrared reflectogram] (IRR) and X-ray, it appears that the artist may have moved the figure’s left arm more than once, as the flesh tone extends under the background paint for a distance. Specific movements are difficult to discern, however. Renoir also quickly indicated an extension of the figure’s blouse at the neckline, bringing up the top slightly near her left shoulder. Initially, the skirt’s profile appeared thinner and the figure seemed to be turned more toward the viewer (fig. 5.7). [glossary:Raking light] and infrared examination also indicate changes to her hairstyle in the final version of the painting: her bun was higher on her head and more tightly held in place with a dark band. The general effect of these changes is that the figure appears bulkier, with a less defined waist. Renoir also reduced the laundry pile at the lower right, adding a bright red background to trim the upper edge of the pile.

Renoir used wider brushstrokes toward the edges of the picture, in the laundry, and along the right side, which broadly contrast with the densely applied, finer strokes associated with the figure (fig. 6.23) and her immediate surroundings. After masking some compositional changes with heavy strokes of paint that tonally mimic the ground color, he continued changing the figure’s posture. The composition’s background wraps around the figure in fine, separate strokes, often directly covering later pentimenti. Renoir alternated individual strokes of unmixed, bold color placed side by side, as in the figure’s hair (fig. 6.24), with more blended, softer transitions between colors and crisscross patterns, as in the skirt. In some areas, soft, fine brushes dragged stiff paint across the surface, leaving heavy impasto with small peaks from lifting the brush (fig. 6.25). The flesh tones appear to alternate between these three techniques; the artist began with a smoother modeling that he later textured with heavy impasto and directional strokes. In other areas, such as the laundry pile and the figure’s blouse, he utilized stiff-bristled brushes, leaving a heavy texture in the paint surface.

Painting tools

Very fine brushes, flat and round, up to 1 cm width.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, vermilion, two red lakes, chrome yellow, cobalt blue, cerulean blue, emerald green, iron oxide red and/or iron oxide yellow, and bone black.

[glossary:UV] examination suggests the presence of fluorescing red lake, particularly in the flesh tones and limited portions of the background, based on the observation of a characteristic, orange [glossary:fluorescence] (fig. 6.26). Visible through microscopic analysis of the surface and [glossary:cross sections] of other portions of the composition, such as the background along the left edge, is a second, nonfluorescing red lake.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The current [glossary:synthetic varnish] was applied in 1969 and replaced a different synthetic varnish from the 1956–57 treatment. Application of this earlier synthetic varnish followed removal of a discolored oil-resin [glossary:varnish]. As the painting was already lined at the time of this treatment (1956–57), it is unclear whether the oil-resin varnish was original to the painting.

Conservation History

The painting has had two documented treatments since acquisition. The earliest notes on the painting come from a 1937 memo indicating that the canvas was in good condition and the frame miters were opening. By 1956 the painting was noted as lined and mounted to a board (either a thin wooden panel or a Masonite-type hardboard), with a secondary, unprimed fabric on the verso of the board, indicating previous undocumented treatment. Although lined, the painting retained its stretcher; the stretcher is either original or evidence of a very early treatment. In January 1957, the work was treated, and an oil-resin varnish was removed along with a heavy layer of grime using a combination of solvent and mechanical cleaning. The work was given a spray coat of synthetic varnish (n/butyl isobutyl methacrylate copolymer resin); [glossary:retouching] was not deemed necessary at the time. In 1969 the work was given a second aesthetic treatment during which the 1957 varnish was removed and replaced with three coats of synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, and a final coat of AYAA).

Condition Summary

The work is in good condition, aqueously lined to a secondary canvas and mounted to an unidentified thin panel. The panel features unprimed canvas on its verso and therefore cannot be positively identified. The panel is concave, creating a slightly dished appearance, but appears stable at this time. There are minimal localized losses to the paint layer, cracking throughout the sections of blue paint (including the skirt and the background left of center), and stretcher-bar creases corresponding to the horizontal [glossary:crossbar]. Along the foldover on all sides, there is abrasion and grime, in addition to localized cracking of both the paint and the support resulting from the lining process.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

Current frame (installed after 1948): The frame is not original to the painting. It is a French, late-eighteenth-century, Louis XVI, scotia frame with acanthus leaves, beading, and leaf-and-tongue sight molding. The frame has water and oil gilding over red bole on gesso. The ornament and outer fillet are burnished. The frame sustained water damage and was subsequently painted with bronze powder paint. It retains most of the original gilding, except on the heavily damaged bottom section. The carved oak molding is mitered and joined with angled, dovetailed splines. At some point in the frame’s history, the original verso was planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance, a back frame was added, and all back and interior surfaces were painted. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is fillet; scotia side; stepped fillet; scotia with acanthus leaves and beaded fillet; frieze; fillet; ogee with leaf-and-tongue ornament; fillet with a cove sight edge; and an independent fillet liner with a cove sight edge that was added when the painting was paired with the frame (fig. 6.27).

Previous frame (installed by 1948): The work was previously housed in a late-nineteenth–early-twentieth-century, Louis XIV reproduction, reverse ogee frame with cast plaster anthemia corner cartouches and shell center cartouches linked by foliate scrollwork (fig. 6.28).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Possibly sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris, June 15, 1882.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, Aug. 3, 1905, for 8,500 francs.

Sold by Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, to the Prince de Wagram (Alexandre Berthier, 4th Prince de Wagram), Paris, by Feb. 24, 1906.

Resold by the Prince de Wagram (Alexandre Berthier, 4th Prince de Wagram), Paris, to Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, Feb. 24, 1906, for 9,000 francs.

Possibly sold by Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, to Léon Orosdi, Paris (died 1922), Mar. 2, 1906.

Acquired by Galérie Barbazanges, Paris, by Jan. 4, 1923.

Acquired by Meyer Goodfriend, New York and Paris, by Jan. 4, 1923.

Sold at the sale of Meyer Goodfriend, New York and Paris, New American Art Galleries, New York, Jan. 5, 1923, lot 109, to John Levy Galleries, New York, for $2,000.

Acquired by Howard Young, New York, by Mar. 28, 1923.

Sold by Howard Young, New York, to Charles H. Worcester, Chicago, by Mar. 28, 1923.

Given by Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1947.

Exhibition History

Paris, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Exposition A. Renoir, May 1892, cat. 8, as Laveuse.

Art Institute of Chicago, Exhibition of the Worcester Collection, July 24–Sept. 23, 1923, no cat.

Toledo Museum of Art, Paintings by French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, Nov. 7–Dec. 12, 1937, cat. 30 (ill.).

New York, Wildenstein, Renoir: A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the American Association of Museums in Commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of Renoir’s Death, Mar. 27–May 3, 1969, cat. 37 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 31 (ill.).

Atlanta, High Museum of Art, May 25, 1984–May 30, 1985, no cat.

Tokyo, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Renoir: From Outsider to Old Master, 1870–1892, Feb. 10–Apr. 15, 2001, cat. 13 (ill.); Nagoya City Art Museum, Apr. 21–June 24, 2001.

Columbus (Ohio) Museum of Art, Renoir’s Women, Sept. 23, 2005–Jan. 8, 2006, cat. 2.

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 25 (ill.).

Selected References

Galeries Durand-Ruel, Exposition A. Renoir, exh. cat. (Imp. de l’Art, E. Ménard et Cie, 1892), p. 37, cat. 8.

“Renoir Painting Sold for $7,000,” New York Times, Jan. 6, 1923, p. 13.

Toledo Museum of Art, Paintings by French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, exh. cat. (Toledo Museum of Art, 1937), n.pag., cat. 30 (ill.).

Daniel Catton Rich, Catalogue of the Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection of Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings (Lakeside, 1938), pp. 77–78; pl. 46/cat. 80.

Edith Weigle, “Gift of Art,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 25, 1947, p. C6 (ill.).

“Donor to Get Honor Degree at Art Institute,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 13, 1947, p. 21.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Complete List of Works,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 41, 5 [pt. 3] (Sept.–Oct. 1947), p. 63.

Art Institute of Chicago, “The Magnificent Worcester Gift,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, 42, 2, pt. 3 (Feb. 1948), p. 4 (ill.).

Frederick A. Sweet, “The Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 50, 3 (Sept. 15, 1956), p. 44.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961; reissue, 1968), p. 396.

Frederick A. Sweet, “Great Chicago Collectors,” Apollo 84, 55 (Sept. 1966), p. 203.

François Daulte, Renoir: A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the American Association of Museums in Commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of Renoir’s Death, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 1969), cat. 37 (ill.).

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1, Figures, 1860–1890 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), pp. 254–55, cat. 348 (ill.); 416.

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir, nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), p. 108, cat. 434 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 26; 86; 90–91, cat. 31 (ill.).

Sophie Monneret, Renoir, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1989), p. 153, cat. 8 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 79 (ill.).

Gerhard Gruitrooy, Renoir: A Master of Impressionism (Todtri Productions, 1994), p. 109 (ill.).

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 30; 37–38; 87, pl. 6; 108 (detail).

Katsunori Fukaya, “The Laundress,” in Bridgestone Museum of Art and Nagoya City Art Museum, Renoir: From Outsider to Old Master, 1870–1892, exh. cat. (Bridgestone Museum of Art/Nagoya City Art Museum/Chunichi Shimbun, 2001), pp. 82–83, cat. 13 (ill.).

Paul Hayes Tucker, “Renoir in the 1870s and ’80s: Modernity, Tradition, and Individuality,” in Bridgestone Museum of Art and Nagoya City Art Museum, Renoir: From Outsider to Old Master, 1870–1892, trans. Yumiko Yamazaki and Yuko Tatsuno, exh. cat. (Bridgestone Museum of Art/Nagoya City Art Museum/Chunichi Shimbun, 2001), pp. 37–38, 223.

Ann Dumas and John Collins, Renoir’s Women, exh. cat. (Columbus Museum of Art/Merrell, 2005), pp. 11, fig. 2; 118.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, with the collaboration of Camille Frémontier-Murphy, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, 1858–1881, vol. 1 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), p. 409, cat. 382 (ill.).

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 17; 68–69, cat. 25 (ill.). Simultaneoously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale Unversity Press, 2008), pp. 17; 68-69, cat. 25 (ill.).

Anne Distel, Renoir, Les Phares (Citadelles et Mazenod, 2009), pp. 158–59, ill. 142; 310.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 2464. Ce tableau a peut-être été acheté à l’artiste par Durand-Ruel le 15 juin 1882, livre de stock Paris 1880–84, stock no. 2464.

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 1520. Blanchisseuse, Livre de stock Paris 1891; Blanchisseuse, livre de stock Paris 1901.

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel Paris 1647. Blanchisseuse, photo entre 1899 et 1901.

Documentation from the Bernheim-Jeune Archives

Inventory number

No. de stock Bernheim-Jeune 1485352

Photograph number

Photographie Bernheim-Jeune no. 1066553

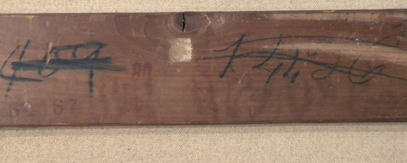

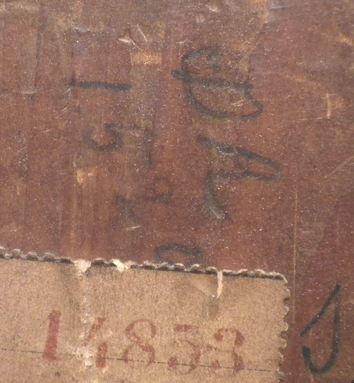

Labels and Inscriptions

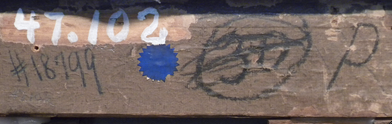

Undated

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: #18799 (fig. 6.29)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: blue label

Content: [blank] (fig. 6.29)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 30 [circled and crossed out] (fig. 6.29)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: P (fig. 6.29)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: red stamp

Content: 2096 (fig. 6.30)

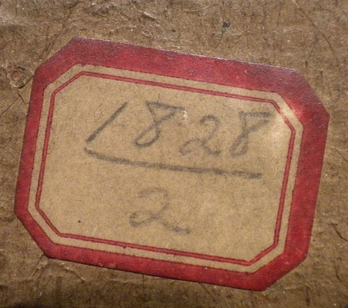

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite) on red-and-white label

Content: 1828/2 (fig. 6.31)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: stamp

Content: 341[6]7 (fig. 6.32)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 580 (fig. 6.33)

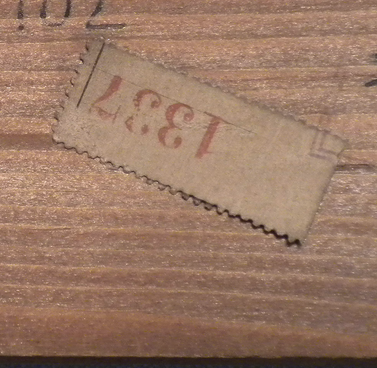

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 1337 [?] (fig. 6.34)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 2093 (fig. 6.35)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: red stamp on label

Content: 1337 (fig. 6.36)

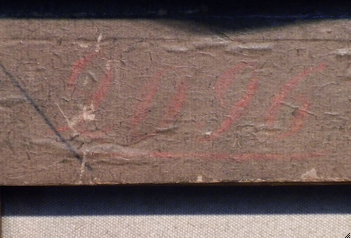

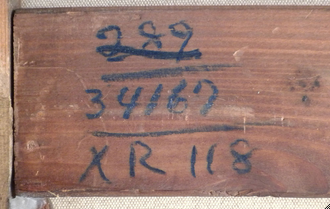

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 289 / 34167 / XR 118 (fig. 6.37)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 409 [crossed out] (fig. 6.38)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 14426 [crossed out] (fig. 6.38)

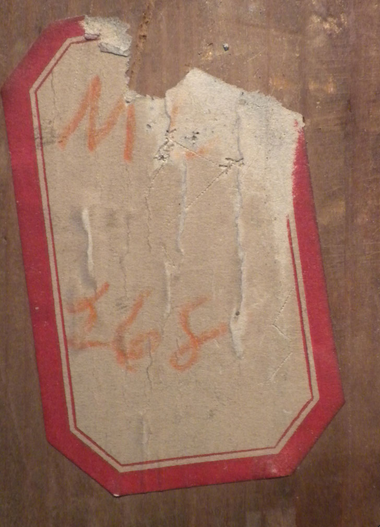

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (red pencil) on red-and-white label

Content: M [ . . . ] / 268 (fig. 6.39)

Pre-1980

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: DR [ . . . ] / 1520 (fig. 6.40)

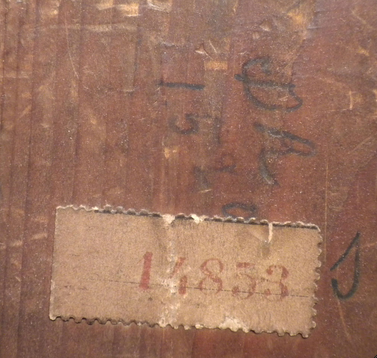

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: red stamp

Content: 14853 (fig. 6.41)

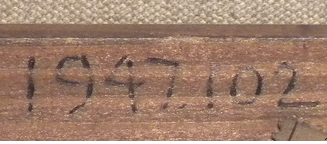

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (pen)

Content: 1947.102 (fig. 6.42)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: hand-painted script

Content: 47.102 (fig. 6.29)

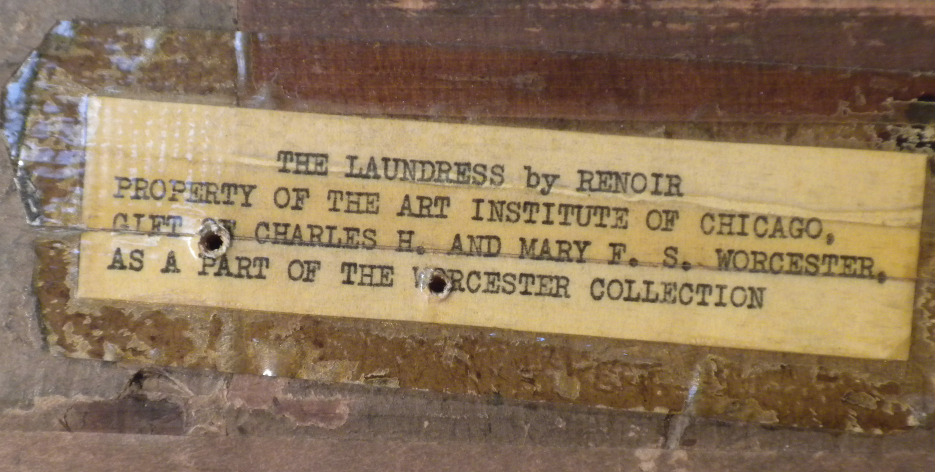

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: typed label

Content: THE LAUNDRESS by RENOIR / PROPERTY OF THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / GIFT CHARLES H. AND MARY F. S. WORCESTER, / AS PART OF THE [WOR]CESTER COLLECTION (fig. 6.43)

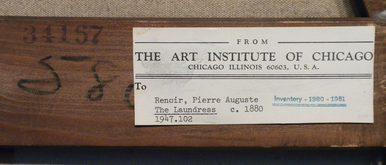

Post-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed/typed label

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / To / Renoir, Pierre Auguste / Inventory 1980–1981 / The Laundress c. 1880 / 1947.102 (fig. 6.44)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, films scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner.

Infrared Reflectography (IRR)

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) J filter (1.5–1.7 µm); X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.7 µm).

Visible light

Normal light, raking light, transmitted light overalls, and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet light

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-resolution visible light (and ultraviolet light)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (B+W 486 UV/IR cut MRC filter).

Microscopy and photomicrographs (sample and cross-section analysis)

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube ; Bruker ArTAX.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated thread counting

Thread count and weave information determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image registration

Overlay images registered by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., using a novel image-based correlation algorithm.

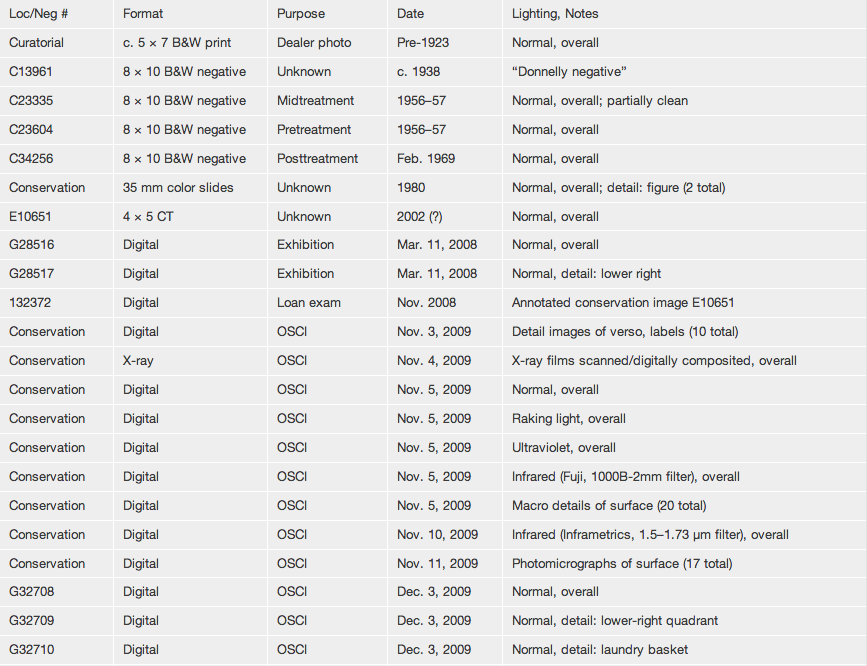

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 6.45).