Renoir and Sisley

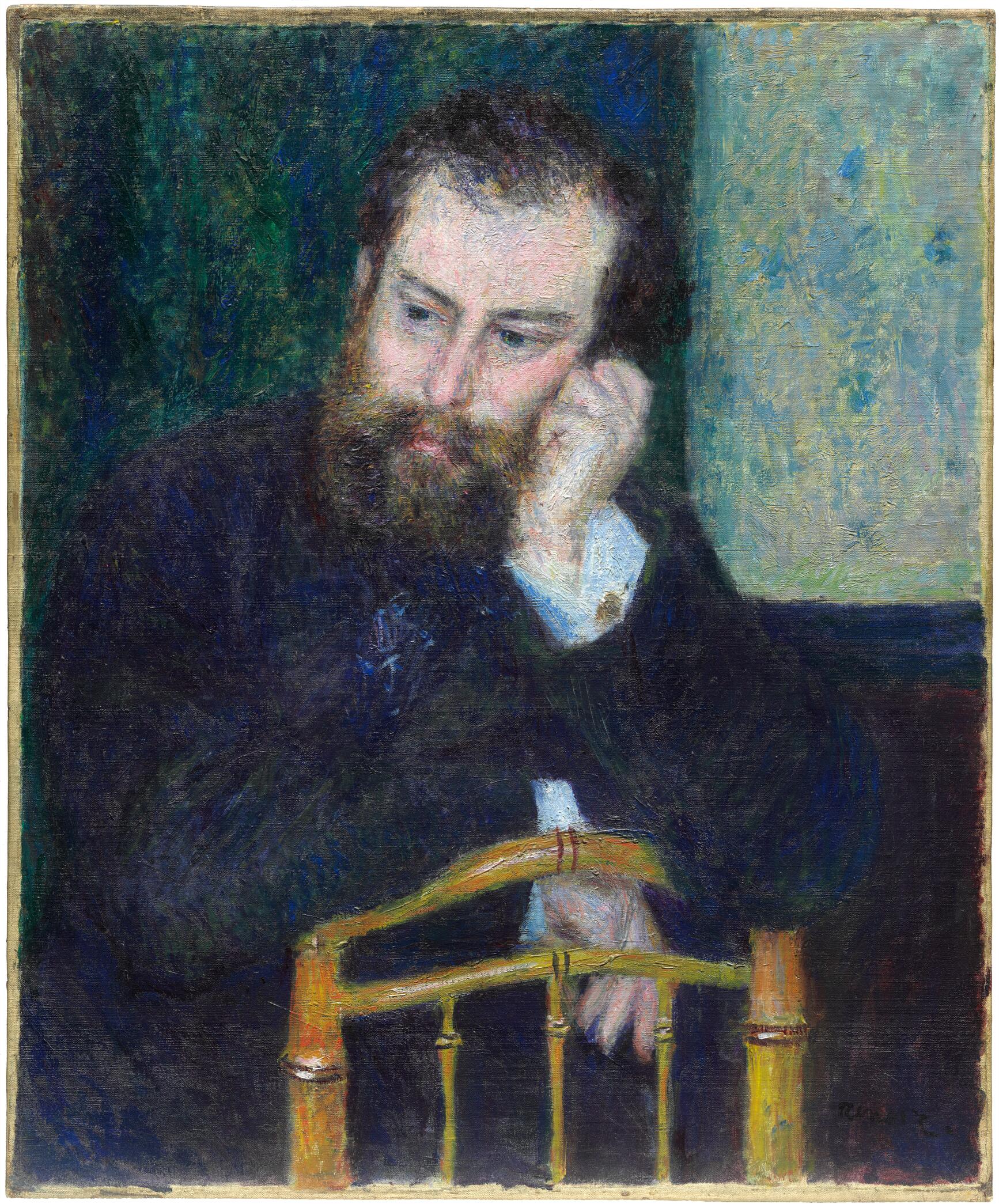

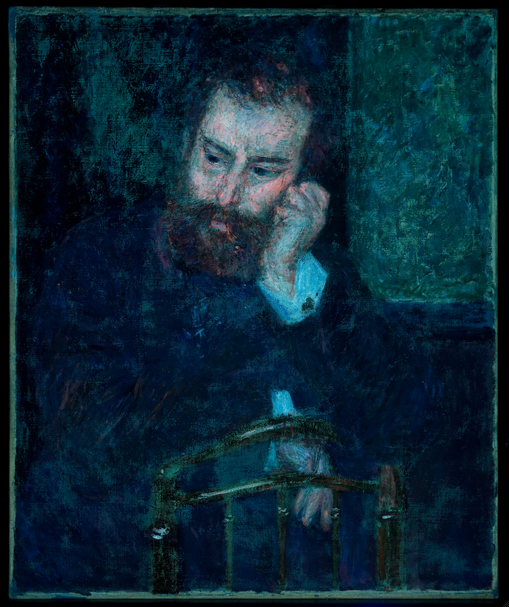

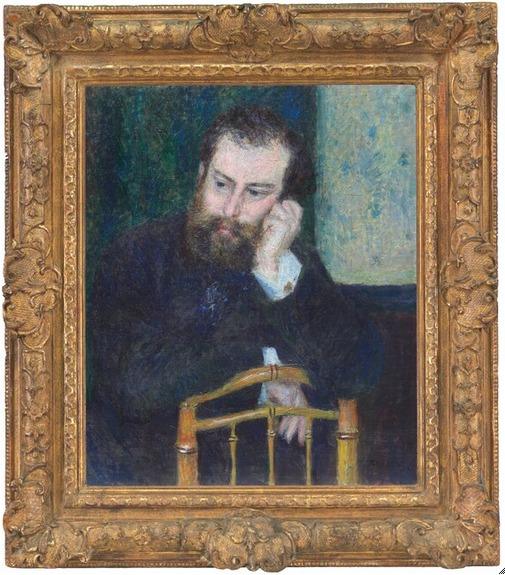

In this painting of a close friend, Renoir dispensed with the formality typical of male portraiture in favor of an audacious originality of pose and execution. Comparing this work to his first portrait of Alfred Sisley (fig. 4.1 [Daulte 37; Dauberville 525]) and his picture of Alfred’s father, William Sisley (fig. 4.2 [Daulte 11; Dauberville 524]), makes clear how much Renoir’s pursuit of Impressionism over more than a decade opened up innovative paths of exploration. The elder Sisley moved to Paris from London in 1839 to manage a company dealing in luxury goods, with a specialty in imported gloves. Alfred was born on October 30 of the same year. Renoir’s portraits of the two Sisley men, depicted at the height of their prosperity, were important early commissions for the young artist, and he did not stray far from convention in pose, handling, and color. The image of William was accepted at the Salon of 1865 and ably proclaimed Renoir’s competence and skill as a portraitist to the Parisian public.

Eleven years later, in 1876, Renoir presented Alfred in a very different aspect. No longer is he the self-assured son of a comfortable bourgeois family, confident of his future. Instead he sits casually, facing the back of a mass-produced, bamboo-style side chair, with a distracted gaze that conveys a thoughtful introspection uncharacteristic of representations of men in nineteenth-century France, which for the most part coded authority and action. In 1926, near the end of his life, Claude Monet remembered the circumstances of the portrait’s creation: “I know of only one portrait of Sisley by Renoir. It’s the one he did at my house at Argenteuil, where he’s sitting astride my chair.” This would have been Monet’s second home in the riverside town of Argenteuil, the newly built Pavillon Flament, into which he moved with his family in October 1874. Monet, Renoir, and Sisley’s gathering there in 1876 was undoubtedly the occasion for earnest discussion of the future of Impressionist group exhibitions. Alfred Sisley is a fundamentally Impressionist painting in its freedom of handling and novel treatment of subject. While not intended as a manifesto for the movement, the portrait nevertheless acted as an affirmation of shared aesthetic goals that the three artists had cultivated over a decade and a half.

Though the Chicago portrait would be the last of Renoir’s paintings for which Sisley posed, it was not the first time he had appeared in a painting that implied shared aesthetic views between the artist and the sitter. During the 1860s, he posed for a number of Renoir’s genre paintings. In 1868 he modeled with Renoir’s mistress Lise Tréhot for The Couple (fig. 4.3 [Daulte 34; Dauberville 256]), a bold demonstration of the artist’s awareness of the latest fashion trends and his mastery of colorful design. Firm adherents of the plein air school, Renoir and Sisley painted landscapes together in the forest of Fontainebleau during the summer of 1866. The occasion became the subject of Renoir’s first monumental group portrait, The Inn of Mère Antony (fig. 4.4 [Daulte 20; Dauberville 229]), in which Sisley is joined by fellow artist Jules Le Coeur and an unidentified figure. Sisley, dapper in a white felt hat and dark suit, engages his attentive companions in conversation. On the table before him sits a copy of L’événement, for which Émile Zola had been the art critic until that spring. The presence of the journal likely signifies Sisley’s involvement in progressive art debates of the day. His portrayal as a member of the avant-garde in The Inn of Mère Antony thus provides meaningful context for Renoir’s representation of him in the same capacity ten years later, though in the later work the point was made through provocative use of Impressionistic brushwork.

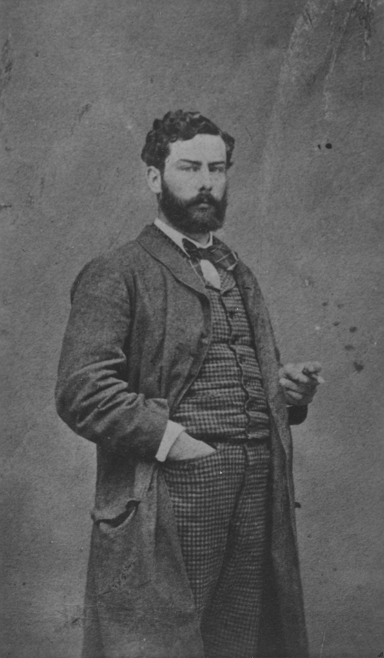

Monet, Renoir, and Sisley’s friendship began in 1862 in the studio of Charles Gleyre, where they first discovered that they shared common artistic interests. Recalling the first time she saw her future husband, probably in 1878 or 1879, Aline Charigot said that he was walking with Sisley and Monet on the rue Saint-Georges. Her description of the three as wearing their hair long and causing a spectacle by their appearance belies Sisley’s reputation for sporting elegant attire; in Renoir’s portrait he looks the perfect English gentleman, complete with starched shirt, cuff links, and lavaliere. Indeed, a photograph of Sisley usually dated to the early 1880s shows him meticulously clothed (fig. 4.5). Though Sisley may not have dressed the part of the struggling artist, there was no question about his aesthetic allegiances, allying himself as he did with Monet and Renoir to form a bloc within the Impressionist movement. In 1879 Renoir and Sisley declined to participate in the fourth Impressionist exhibition, choosing instead to send their paintings to the Salon that year (which Renoir had also done the year before). In 1880 Monet followed their example, exhibiting a landscape at the Salon (The Seine at Lavacourt, 1880; Dallas Museum of Art) rather than contributing to the fifth Impressionist exhibition in April. Sisley’s refusal by the Salon jury of 1879 weighed heavily on Renoir, whose portrait Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children (1878; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [Daulte 266; Dauberville 239]) encountered no such resistance. In June 1879 Renoir wrote a letter to Georges Charpentier encouraging the publisher to hold an exhibition of Sisley’s work at the offices of La vie moderne, but this did not come about until November 1881. Possibly feeling betrayed by what he perceived as careerism trumping group ideals, Sisley grew distant from Renoir, eventually becoming so bitter and withdrawn that he preferred to cross the road rather than meet his former friend on the sidewalk.

The Sisley Portrait in the Context of Impressionism

Though the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel had been buying Sisley’s paintings since 1872, the commencement of the Impressionist exhibitions in April 1874 brought Sisley critical attention and hopes of an improved financial situation, much needed after his father’s bankruptcy following the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. The second Impressionist exhibition in April 1876 also proved salutary for Sisley’s career. His submission consisted of eight landscape views of his home at the time, Marly-le-Roi, located fifteen miles west of Paris near Bougival. They included two winter scenes and a view of the notorious floods that struck in March. The paint could hardly have been dry, but the works were already on the market; all of Sisley’s paintings in the exhibition were borrowed from art dealers, suggesting a growing appreciation of and demand for his work. Indeed, at least two critics of the exhibition singled him out as an artist of notable talent. A sense of Sisley’s rising star is conveyed in Renoir’s portrait, which first appeared as part of Renoir’s submission to the third Impressionist exhibition in April 1877. That exhibition was also the occasion of an ambitious display of work by Sisley. The catalogue listed seventeen Sisley landscapes, eleven of which had owners, including some of the most important Impressionist collectors: Georges Charpentier, Théodore Duret, and Georges de Bellio.

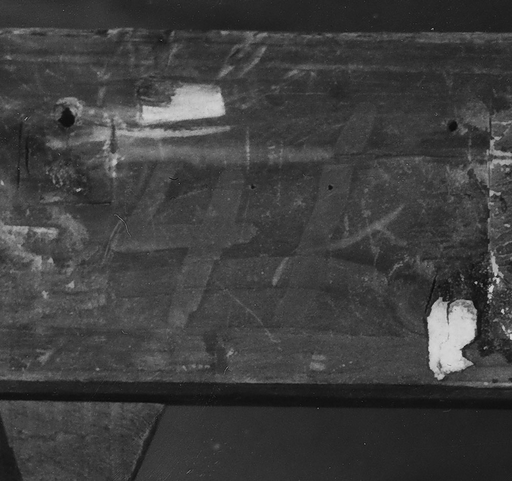

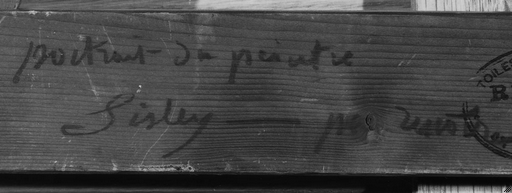

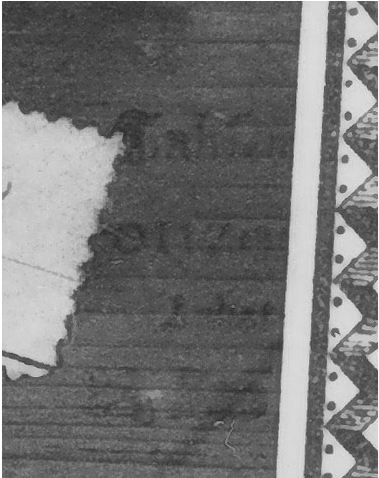

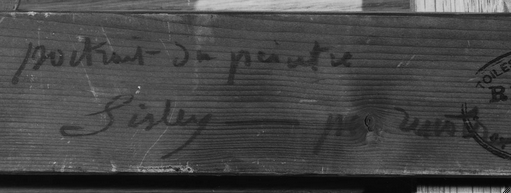

The portrait of Sisley probably remained in Renoir’s studio until it was sent to the exhibition. There is no evidence that Sisley himself ever owned the work. Indeed, an inscription on the original stretcher, portrait du peintre Sisley—par Renoir, displays characteristics of Renoir’s hand (in the formation of the p, for example) and may date from this time (fig. 4.6). The 1877 Impressionist exhibition included Renoir’s masterpiece Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876; Musée d’Orsay, Paris [Daulte 209; Dauberville 211]) and was pivotal to establishing his reputation as the preeminent Impressionist figure painter and portraitist. The portrait of Sisley was one of several to demonstrate Renoir’s ability in this genre. The others he exhibited represented a virtual assembly of the select members of Parisian society who supported him, including many of the same patrons who purchased work by Sisley: Marguerite Charpentier, wife of Georges (1876–77; Musée d’Orsay, Paris [Daulte 226; Dauberville 465]); Jeanne Samary (fig. 4.7 [Daulte 229; Dauberville 462]), actress of the Comédie Française; and Jacques-Eugène Spuller (c. 1877; private collection [Daulte 71; Dauberville 545]), a Republican politician who had been elected deputy of the Seine in March 1876. The emphasis on portrait painting in the context of an Impressionist exhibition was not simply self-promotion for Renoir; it was also an attempt to establish a new interest in the genre as an art form. Georges Rivière, one of Renoir’s closest friends at the time and his future biographer, provided one of the few contemporary comments on the Sisley portrait, highlighting its importance to Renoir’s development as an artist: “The series of portraits ends with one of Sisley, one of the establishment regulars. This portrait achieves an extraordinary likeness and possesses great value as a work of art.”

In claiming that the Sisley portrait was not only an accurate likeness but also artistically significant, Rivière expanded the usual critical discourse surrounding portraiture at the Salon, which was limited in breadth as the genre did not invite progressive approaches to painting. Renoir’s example at the 1877 exhibition also inspired critics close to the Impressionists to reconsider portraiture’s validity as a pursuit for progressive artists. In a brief but pioneering historical survey of Impressionism published as a brochure in 1878, Duret alluded to Renoir’s gifts as a portrait painter: “Renoir excels at portraits. Not only does he catch the external features, but through them he pinpoints the model’s character and inner self.” Duret’s comments suggest that there existed a level of familiarity between the sitter and the artist in Renoir’s work that was unusual in nineteenth-century portrait painting. Sisley’s pose, as if he has been caught in a moment of reflection, is remarkably original, but it also reveals that Renoir looked to the past in developing his innovative approach: Alfred Sisley shares the psychological awareness and spontaneity of pose visible in the work of Frans Hals and Dutch seventeenth-century portraiture more generally (see fig. 4.8).

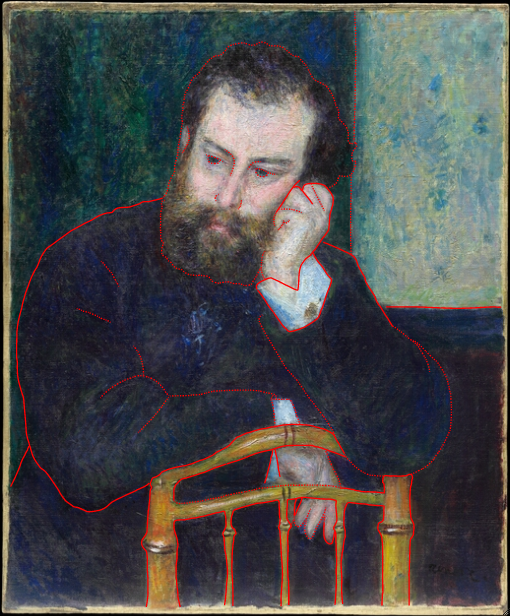

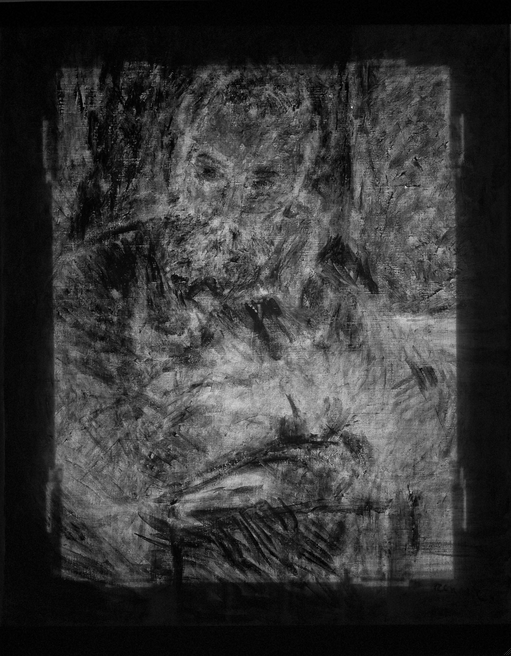

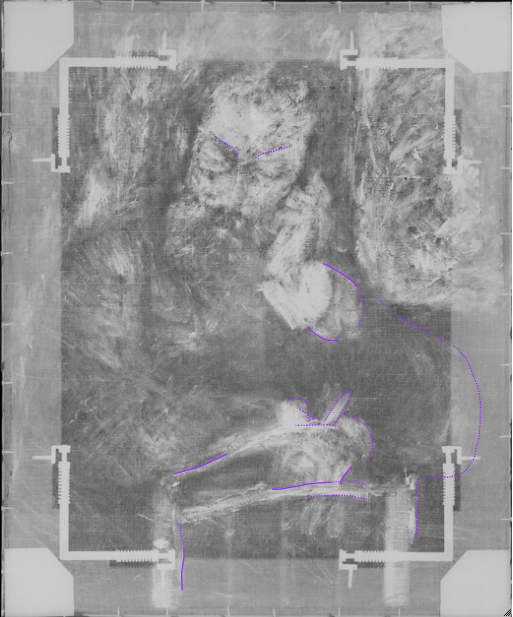

Renoir did not arrive easily at Sisley’s pose, however. [glossary:X-ray] and transmitted infrared images of the painting show that the artist made many changes to the position of the arms. It is possible that both arms were initially folded over the chair back (fig. 4.9; see Paint Layer in the technical report). But once resolved, the pose must have satisfied Renoir, as he returned to it in late 1877 for the commissioned portrait of the collector Eugène Murer (fig. 4.10 [Daulte 246; Dauberville 547]).

It was in 1876 or early 1877 that Renoir and Sisley made the acquaintance of Murer, a pastry cook turned artist, who became one of Sisley’s most devoted patrons. Alfred Sisley was among eleven Renoir paintings that Murer apparently purchased in a lot for 500 francs, probably not long after the close of the third Impressionist exhibition at the end of April 1877. This transaction had taken place by early 1883, when the artist approached Murer about borrowing the portrait for his retrospective exhibition, organized by Durand-Ruel and scheduled to open April 1 of that year. But the portrait is not identified in the catalogue of the retrospective, nor is Murer credited as a lender to that exhibition, and thus it may not have been on display or may have been exhibited but not catalogued. Renoir’s request for the Sisley portrait suggests that he still felt kindly toward his friend, though little is known about their relationship during this period. Sisley’s own show of some seventy works, held June 1–25, 1883, followed the solo exhibitions of Monet, Renoir, Eugène Boudin, and Camille Pissarro and completed the series of Impressionist exhibitions at Durand-Ruel’s boulevard de la Madeleine location. Sisley remained an important member of the Impressionist circle of artists promoted by Durand-Ruel and kept up regular contact with Pissarro.

Renoir’s Stipple-Brush Technique

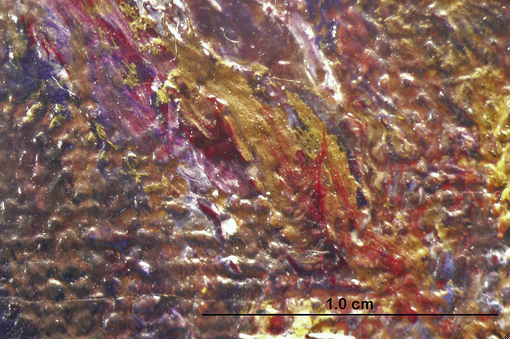

This undated portrait has been assigned dates ranging from 1874 to 1879, but it was most likely made shortly after the second Impressionist exhibition of 1876, for a variety of reasons. First, an earlier date would be inconsistent with Renoir’s tendency in the mid-1870s to exhibit his paintings soon after they were finished. Second, the distinctive stippled appearance of the work, in which short brushstrokes rich with paint were used to create a highly textured surface, is shared by many works executed in 1876 and 1877, including the five other oil portraits in the 1877 Impressionist exhibition. This visually dynamic technique did not sit well with one art critic: “Some of Renoir’s Portraits look all right—at a distance—so that you do not notice too much his way of applying brushstrokes like pastel hatchings and the peculiar scratches that make his style seem so painful.” The comparison of Renoir’s brushstrokes to “pastel hatchings” can most readily be read as referring to the crisscross strokes in the arms and the overall lighter tone of Jeanne Samary (fig. 4.7). The brazen handling of the pale flesh tones in Sisley’s face, where, in addition to fine brushes, the artist used a palette knife to bring up the bright reddish-orange hues below (fig. 4.11), contrasts with the impeccably bourgeois presentation of the sitter and identifies Renoir irrefutably as a member of the Impressionist circle.

In 1902 Camille Mauclair suggested that Alfred Sisley anticipated the pointillism of the Neo-Impressionists, but the portrait displays little of the controlled construction of form and scientific approach to color that define that movement. Rather, Renoir achieved volume and depth by using a small brush to apply a wide range of colors. This is particularly noticeable in the small directional strokes of the beard (fig. 4.12). In addition, Renoir assigned as much importance to the layering of colors as to their juxtaposition. Around the eyes, for example, he applied the paint using several different methods in order to produce a variety of surface textures, from visible canvas weave to thick impasto that yields a sculptural effect (fig. 4.13). This technique of unifying the entire canvas with a stippled effect is frequently seen in Renoir’s more experimental painting style during the mid-1870s and is especially evident on close examination, where the details seem so gestural.

Renoir’s portrait of Sisley has long been recognized as an honorable tribute to an important friendship and artistic alliance. A photograph of the portrait, reproduced en lettre (in the body of the paragraph), was the opening illustration for a lengthy obituary of Sisley published in the March 1899 issue of the Gazette des beaux-arts. Appearing at a sensitive time following the Musée du Luxembourg’s acceptance of Gustave Caillebotte’s collection of Impressionist paintings, the obituary included an assessment of Impressionism’s place in art history.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Renoir’s portrait of Alfred Sisley is heavily worked, making use of the various textures afforded by the [glossary:oil] medium. Beginning with a standard-size, commercially prepared [glossary:canvas], the artist appears to have sketched the initial contours of the figure in blue paint; some of these blue contours also initiated the painting process. Crosshatching and the play of competing textures and colors layered over one another are common throughout the background and the figure’s coat. The flesh tones show the heaviest working, especially in the face, where Renoir employed a [glossary:palette knife] to model the features, scraping away the paler layers to reveal the brighter paint beneath. The paint is often of a stiff consistency and contrasts with more traditional [glossary:wet-in-wet] modeling through its pronounced texture and limited intermixing. For the figure’s beard, the artist used a wide array of colors and very small brushes to create the sense of volume and depth. Lastly, small touches of bright color were added to the beard, eyes, and highlights of the chair.

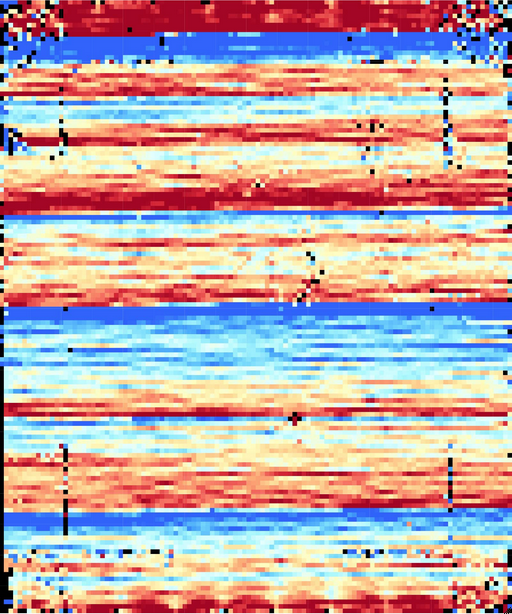

Renoir made alterations to the main contours of the figure’s body, widening both arms, moving both cuffs, and raising the right shoulder. Evidence in the [glossary:transmitted-infrared] and [glossary:X-ray] images also suggests that Sisley may initially have been portrayed with his right hand crossed over his left across the top of the chair back. The chair itself was also changed: the vertical stiles were moved slightly to the left, and the curved, horizontal rails were tapered and curved further downward on the right side. The X-ray, raking-light, and infrared images show a number of unidentified forms around Sisley’s right hand and on the far right, which may indicate other changes. The work is coated with a thin [glossary:natural-resin varnish], which serves to saturate the colors and visually differentiate them, especially in the coat, hair, and dark background, but it is not original to the painting.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 4.14).

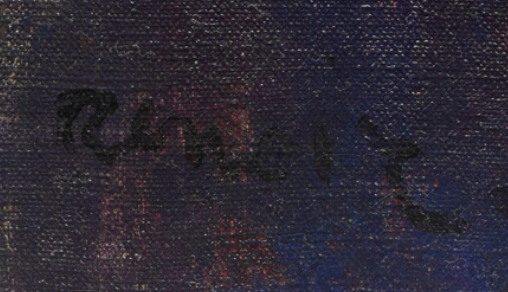

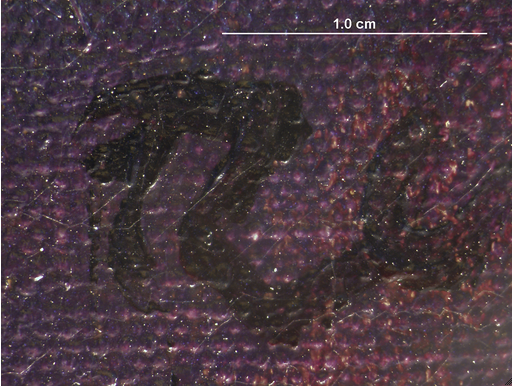

Signature

Signed: Renoir. (lower right, in dark-red paint) (fig. 4.15, fig. 4.16).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

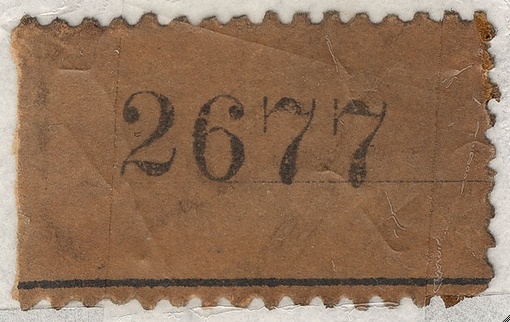

Standard format

The original dimensions of the canvas were approximately 65 × 53.8 cm, measuring from the original foldover. This is consistent with a no. 15 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size (65 × 54 cm) canvas; this is also the number stenciled on the verso of the original [glossary:stretcher] (fig. 4.17, fig. 4.18).

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 22.6V (0.7) × 16.8 (1.3) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

There is [glossary:cusping] around the perimeter of the canvas corresponding to the placement of the original tacks; cusping along the vertical warp threads is particularly pronounced. In addition, the canvas is marked by irregular thread thickness, especially the horizontal threads, resulting in a wide variation in thread density (6.9–32.9 threads/cm) (fig. 4.19).

Stretching

Current stretching: When the painting was lined in 1972, the original dimensions were increased by approximately 0.25 cm (1/10 in.) on all sides (see Conservation History).

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed approximately 4.5–6.5 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Four-member redwood ICA spring stretcher. Depth: 2.7 cm.

Original stretcher: Five-member keyable stretcher with blind mortise-and-tenon construction and a horizontal [glossary:crossbar]. Depth: 0.8 cm.

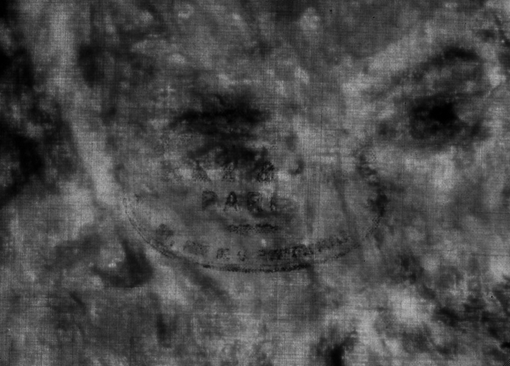

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: ovular stamp

Content: TOILES ET COULEURS FINES / REY & Cie / PARIS. / x [5]1 RUE DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULD x (fig. 4.20)

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: stamp

Content: 15 (fig. 4.18)

Stamp

Location: verso of original canvas (covered by lining)

Method: ovular stamp

Content: [. . .] / RE[Y] & [. . .] / PARI[S] / [. . .] RUE [. . .] (fig. 4.21)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

The canvas has a commercial [glossary:ground] layer that extends to the edges of the [glossary:tacking margins]. The preparation is smooth and thin, ranging from approximately 10–105 µm in depth, and partially fills the canvas [glossary:weave] (fig. 4.22).

Color

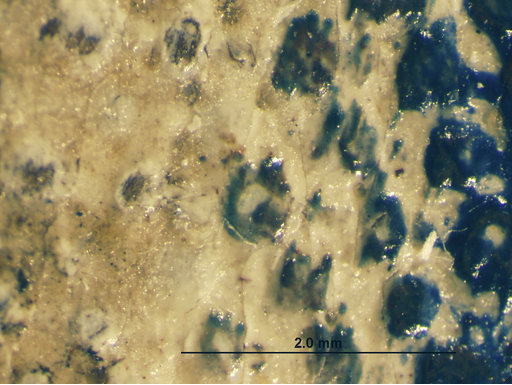

The commercial preparation appears to be almost white, with dark particles visible under [glossary:stereomicroscopic examination] (fig. 4.23). The ground remains visible in selected areas of the background, especially on the right (fig. 4.24).

Materials/composition

The ground is predominantly lead white with small amounts of barium sulfate; iron oxide yellow, orange, and/or brown; and associated silicates and clay minerals, calcium-based compounds, and traces of alumina. The binder is estimated to be oil.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

Reflected- and transmitted-infrared examinations indicate that Renoir outlined the figure’s coat and major contours; however, microscopic examination suggests that these contours also initiated the painting stage (fig. 4.25).

Medium/technique

Blue paint.

Revisions

No compositional changes noted in drawing stage; see Paint Layer.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

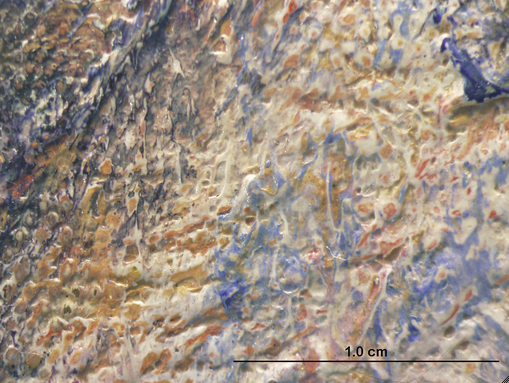

Renoir vigorously worked the paint throughout this composition, using various textures and exercising his ability to manipulate the medium. The work seems to have been executed in a number of stages, probably beginning with Sisley’s sitting for the artist while he established the basic composition, followed by further working up of the paint layers either with additional sittings or later in the studio; the paint layers appear to have mostly dried between painting campaigns. The paint in many areas is rather stiff, paste-like, and thick, reinforcing the textures of the canvas weave and underlying paint with each brushstroke. This is very evident on the upper right, where Renoir began with a heavy zigzag pattern in an ocher-beige color before layering blues and light greens over it (fig. 4.26). These cooler colors, which caught only the upper ridges of the texture beneath, contrast with the warmer undertones and create an interesting play of competing textures and directional strokes. A similar style of paint application, while less pronounced, can be seen in the background on the upper left (fig. 4.27). The crosshatched effect visible in the background, created with heavy strokes of a stiff-bristle brush, is characteristic of the modeling used throughout the work, and a comparable pattern of strokes in much flatter paint can be seen across the coat. As a finishing highlight on the figure’s left sleeve, the artist applied paint in thin, diagonal strokes that run against the curved contours of the arm. Here he allowed the bulk of the paint to load on one side of a flat brush, creating a thin line akin to that made by the edge of a palette knife.

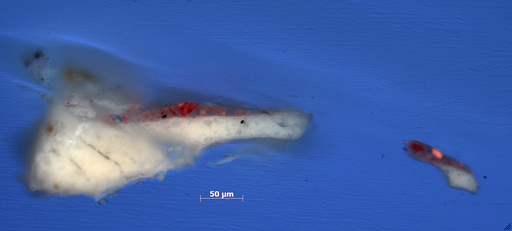

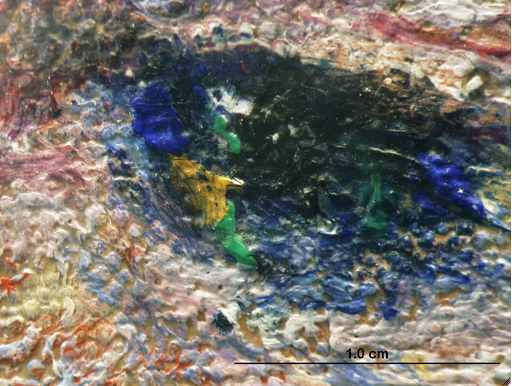

The flesh tones were heavily worked, especially in the face, where Renoir employed very thick paint that he scraped back with a palette knife in some areas. The artist began these areas with thin strokes using a fine brush and almost-dry paint; the paint in these areas—under the eyes, for example—skipped the depressions in the canvas weave and left the ground exposed. Once the contours were established, he applied strong reddish-orange and blue hues in selected areas of the face, over which he put down thin layers of pale-pink and peachy colors for the flesh; then he scraped the flat surface of the palette knife across the upper, still-soft paint layers, revealing the brighter colors below (fig. 4.28). The stiffer paint consistency overall lent itself to a different kind of wet-in-wet [glossary:modeling], in which each stroke with a soft-bristle brush picked up less of the surrounding and underlying colors, but more of the texture. This is very evident in the figure’s beard, where the artist seems to have used all the colors on his [glossary:palette] with very small brushes in a series of small, directional strokes that blend with one another to varying degrees. Within the beard, traditional wet-in-wet modeling with paint of a more liquid consistency appears side by side with the stiffer paint (fig. 4.29), and a few bright touches were applied as final details once the majority of the paint was dry. Renoir used similar small dabs of bright color or white throughout the work, for example, the bright orange-reds and white highlights on the bamboo chair in the foreground and the blue, green, and yellow in the figure’s eyes (fig. 4.30).

The artist changed some of the major contours in this composition, adjusting Sisley’s pose and the space he occupies. The head and the hair immediately around it were established early in the process and the background brought in before the feathering curls on the right were added. The X-ray suggests that there may have been slight changes to the figure’s face and the placement of the nose and eyes; however, the nature of these revisions is unclear. The figure’s right shoulder was raised, and his right arm widened along its outer edge. Comparing the finished painting with the X-ray and infrared images suggests that Renoir altered this outer contour more than once. Similarly, the figure’s left sleeve was also widened along the forearm; this and a slight repositioning caused the elbow to largely obscure the top right corner of the chair. The X-ray suggests that the cuff of this sleeve may originally have been farther away from the face and farther down, which may have affected the position of the hand. The cuff was then moved up toward the face, making the sleeve longer, and the heel of the hand and the cuff in their current position were widened to make them proportionate to the sleeve. The X-ray and transmitted- and reflected-infrared images show other forms near the dangling right hand and on the far right that suggest that the artist may have made other compositional changes; for instance, it is possible that Sisley was initially portrayed with both elbows out and hands crossed over the back of the chair. In the transmitted-infrared image it looks as if the top edge of the figure’s right arm might have been higher than its final placement, while the [glossary:infrared reflectogram] shows the faint outline of his elbow out toward the right edge of the painting. The area around the fingers in the infrared and X-ray images suggests that both hands were once toward the center of the work, possibly with the right hand crossed over the left; as there is little evidence of the top edge of the figure’s left arm in any of the technical images, this idea appears to have been abandoned early in the process in favor of the current pose.

While the thin, vertical spindles of the chair were executed over Sisley’s finished form, the larger elements—the vertical stiles and the horizontal rails—seem to have been established before Renoir brought in the dark-blue surroundings. After initially placing the two outer stiles and adjusting the figure’s coat and the background paint, the artist moved the chair slightly to the left. Under normal viewing conditions, the left edges of both stiles pass over the textured, diagonal strokes of the figure’s costume (fig. 4.31). The curved, horizontal rails of the chair back were also subtly altered; in front of the figure’s dangling right hand, the forms were slimmed and angled slightly further downward, to make them more symmetrical with the left side.

Painting tools

Stiff- and soft-bristle brushes with strokes up to 1 cm wide; small, round brushes; palette knife for scraping/removal of paint.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, cobalt blue, cerulean blue, chrome yellow, cadmium yellow, iron oxide yellow-brown, viridian, emerald green, carbon black, vermilion, madder lake, and a second red lake.

The observation of a characteristic salmon-colored [glossary:fluorescence] under [glossary:UV] light indicates that Renoir used fluorescing red lake in the flesh tones, hair, chair, and some areas of the coat (fig. 4.32). [glossary:Cross-sectional analysis] reveals that he used a second, nonfluorescing red lake in other areas (fig. 4.33). A small section from a sample containing both fluorescing and nonfluorescing red lakes was analyzed and found to contain madder lake.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The current very thin natural-resin varnish (damar) was applied during the 1996–97 treatment. UV examination reveals residues of an earlier natural-resin varnish around areas of thick [glossary:impasto] throughout the painting.

The work has been varnished at least three times in its history. The current [glossary:varnish] replaced a [glossary:synthetic varnish] applied during the 1972 treatment (see Conservation History). During that treatment, a discolored natural-resin varnish was removed. A 1968 condition report notes the presence of cleaning abrasions and subsequent “glazing” to hide them. Such abrasions indicate that the work was treated and cleaned prior to 1968, and therefore the natural-resin varnish present at that time was not original to the painting. In 1996 a very thin damar varnish was applied, locally blotted, and dry brushed to produce a lean surface while maintaining proper saturation.

Conservation History

The painting has been treated on three documented occasions since the Art Institute acquired it in 1933. In 1968 the work was observed to have a yellowed natural-resin varnish and to be generally abraded, with retouched glazes to minimize the appearance of damage. The abraded appearance noted at this time is thought to be the result of a previous, undocumented cleaning, possibly prior to acquisition. A pulpboard insert was placed between the canvas and the stretcher at an unknown date; however, labels and stamps indicate that the painting retained its original stretcher. During the 1968 treatment, the work was cleaned of grime, and the heavy varnish was slightly thinned with solvents. The more noticeable losses and abrasions were inpainted, and the painting was varnished with three coats of synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, and a final coat of AYAA).

The next treatment, in 1972, sought to address both structural and aesthetic issues. The work was cleaned of grime, varnish, and [glossary:overpaint] with solvents, then faced with starch paste in preparation for lining. The painting was wax-resin lined and attached to a new ICA spring stretcher of slightly larger dimensions. Pretreatment dimensions were listed as 65.5 × 54 cm, and the replacement stretcher measured 66 × 54.6 cm (26 × 21 1/2 in.). Before it was discarded, the original stretcher was photographed, labels were preserved, and stamps were documented with tracings. The work was inpainted and varnished with three coats of synthetic varnish, using the methods and materials of the 1968 treatment.

In 1996 the painting was treated in preparation for exhibition, and the synthetic surface coatings, [glossary:inpainting], and residual starch paste were removed. The painting was examined in its unvarnished state by a group of curators and conservators, who decided that the work was not intended to be completely unvarnished (see Surface Finish). While the flesh tones seemed improved by the cleaning, modeling of the figure’s dark coat and the background was obscured in the unvarnished state. The work was lightly varnished with damar, locally blotted, and dry brushed to achieve proper saturation and balance; finally, it was retouched.

Condition Summary

The work is in good condition, wax lined, planar, and stable. The ground layer has darkened slightly due to the combined effects of grime, age, and saturation of the fabric by the lining material. There is cracking in and around more thickly painted areas, including parts of the coat, flesh tones, and background on the upper left, and there is a concentric impact crack near the figure’s elbow on the lower right. Small, localized losses, some inpainted, occur throughout, and the work has some [glossary:retouching] along the edges. The painting has a thin natural-resin varnish, which imparts saturation and an even gloss.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame appears to be original to the painting. It is a French, late-nineteenth–early-twentieth-century, Louis XIV reproduction, gilt torus frame with cast plaster anthemia corner cartouches and fleur-de-lis center cartouches linked by foliate scrolls and strapwork. The frame has oil and water gilding over red bole on cast plaster and gesso. The sight moldings are burnished, and the ornament is selectively burnished. The gilding is heavily rubbed and toned with a casein or gouache raw umber wash with a gray overwash. The molding is constructed of several woods, including oak, pine, and possibly linden, and is mitered and nailed. At some point in the frame’s history, the original verso was planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance, a back frame was added, and all back and interior surfaces were painted. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is torus with dentil outer molding; sanded back frieze bordered with fillets; scotia side; torus face with anthemia corner cartouches and fleur-de-lis center cartouches on diamond beds, linked by scrolls and strapwork with flower heads on a quadrillage bed; fillet; sanded front frieze; ogee with leaf-tip ornament linked by c-scrolls and strapping on a recut bed; and quirked ogee sight molding (fig. 4.34, fig. 4.35).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Sold by the artist to Eugène Murer, Paris, by Apr. 1883, as part of a lot of eleven paintings sold for 500 francs.

Deposited by Eugène Murer, Paris, at Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1883.

Returned by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Eugène Murer, Paris, 1883.

Possibly sold by Eugène Murer, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1896.

Acquired by Ivan Shchukin, Paris, by Mar. 1899.

Sold at the Shchukin Sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Mar. 24, 1900, lot 17, to Dr. George Viau, Paris, for 6,100 francs.

Dr. George Viau, Paris, to at least June 20, 1912.

Acquired by Herman Heilbuth, by 1921.

Acquired by Howard Young, New York.

Acquired by Mrs. Lewis Larned (Annie Swan) Coburn, Chicago, by 1929.

Bequeathed by Mrs. Lewis Larned (Annie Swan) Coburn (died 1932), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Exhibition History

Paris, 6, rue Le Peletier, 3e exposition de peinture [third Impressionist exhibition], Apr. 1877, cat. 190, as Portrait de M. Sisley.

Rouen, Hôtel du Dauphin et d’Espagne, Magnifique collection d’impressionnistes dont 30 toiles du grand artiste Renoir, May 1896.

Expos. Rétrosp. 1900.

Dresden, Der Grosse Kunstausstellung Dresden 1904, Retrospekive Abteilung, May 1–end of Oct., 1904, cat. 2246, as Bildnis des Malers Sisley.

Possibly Paris, Grand Palais, Salon d’Automne, Oct. 15–Nov. 15, 1904.

Paris, Durand-Ruel, Portraits par Renoir, June 5–20, 1912, cat. 34, as Portrait de Sisley, 1876.

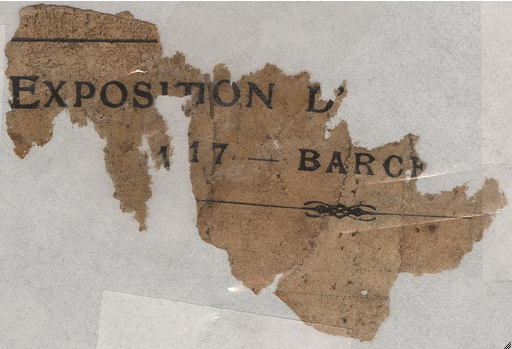

Barcelona, Palacio de Bellas Artes, Exposition d’arts Français, Salon d’automne, 1917, possibly exhibited, but not in cat.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Malerisale, August Renoir: Udstilling af hans Arbejder I Skandinavisk Eje samt Udlaan fra Franske Samlere, Mar. 17–Apr. 10, 1921, cat. 5.

Art Institute of Chicago, Exhibition of the Mrs. L. L. Coburn Collection: Modern Paintings and Watercolors, Apr. 6–Oct. 9, 1932, cat. 31 (ill.).

New York, Wildenstein and Company, Great Portraits from Impressionism to Modernism, Mar. 1–29, 1938, cat. 39.

Milwaukee Art Institute, Masters of Impressionism, Oct. 8–Nov. 15, 1948, cat. 39.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 16 (ill.).

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, Jan. 17–Apr. 6, 1986, cat. 63 (ill.); Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Apr. 19–July 6, 1986.

Tokyo, National Museum of Western Art, 1874 nen—Pari: (dai ikkai inshoha ten) to sono jidai/Paris en 1874: L’année de l’impressionnisme, Sept. 20–Nov. 27, 1994, cat. 44 (ill.).

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, June 27–Sept. 14, 1997, cat. 26 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 17, 1997–Jan. 4, 1998; Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, Feb. 8–Apr. 26, 1998. (fig. 4.36)

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 22 (ill.).

Selected References

Catalogue de la 3e exposition de peinture, exh. cat. (E. Capiomont et V. Renault, 1877), p. 13, cat. 190.

Georges Rivière, “L’exposition des impressionnistes,” L’impressionniste 1 (Apr. 6, 1877), p. 4.

Paul Sébillot, “Exposition des impressionnistes,” Le bien public, Apr. 7, 1877, p. 2. Reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), p. 190.

“Exposition des impressionnistes: 6, rue Le Peletier; 6,” La petite republique française, Apr. 10, 1877, p. 2. Reprinted in Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), p. 176.

Émile Bergerat, “Revue artistique: Les impressionistes et leur exposition,” Journal officiel de la république française 105 (Apr. 17, 1877), p. 2918.

Trublot [Paul Alexis], “La collection Murer,” Le cri du peuple 43 (Oct. 21, 1887). Reprinted in Paul Gachet, Le docteur Gachet et Murer: Deux amis des impressionnistes (Musées Nationaux, 1956), p. 172.

Julien Leclercq, “Alfred Sisley,” Gazette des beaux-arts 21, 3 (Mar. 1899), pp. 227 (ill.), 534.

“Collection d’un amateur,” Gazette de l’hôtel Drouot 86–87 (Mar. 27–28, 1900), n. pag.

Camille Mauclair, “L’oeuvre d’Auguste Renoir,” L’art décoratif 41, pt. 1 (Feb. 1902), pp. 180, 182 (ill.).

Camille Mauclair, L’impressionnisme: Son histoire, son esthétique, ses maîtres, 2nd ed. (Librairie de l’Art Ancien et Moderne, 1904), pp. 112, 229. Translated by P. G. Konody as The French Impressionists (1860–1900) (Duckworth/E. P. Dutton, [1903]), p. 120.

Grossen Kunstausstellung, Offizieller Katalog der Grossen Kunstausstellung Dresden 1904, exh. cat. (Alwin Arnold & Gröschel, Apr. 30, 1904), p. 123, cat. 2246.

Henry Morrison, “Auguste Renoir, Impressionist,” Brush and Pencil 17, 5 (May 1906), p. 202.

Louis Vauxcelles, “Portraits contemporains,” L’art et les artistes 6 (Oct. 1907–Mar. 1908), p. 536 (ill.).

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Portraits par Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1912), p. 5, cat. 34.

Ambroise Vollard, La vie and l’oeuvre de Pierre-Auguste Renoir (A. Vollard, 1919), p. 48. Translated by Harold L. Van Doren and Randolph T. Weaver as Renoir: An Intimate Record (Knopf, 1925), pp. 53, 237.

Georges Lecomte, “L’oeuvre de Renoir,” L’art et les artistes 4, 14 (Jan. 1920), p. 146 (ill.).

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Malerisale, Copenhagen, August Renoir: Udstilling af hans Arbejder I Skandinavisk Eje samt Udlaan fra Franske Samlere, exh. cat. (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Malerisale, 1921), p. 7, cat. 5.

Georges Rivière, Renoir et ses amis (H. Floury, 1921), opp. p. 50 (ill.).

Théodore Duret, Renoir (Bernheim-Jeune, 1924), p. 72. Translated into English by Madeleine Boyd as Renoir (Crown, 1937), p. 54.

Gustave Geffroy, Sisley (G. Crès, 1927), p. 4 (ill.).

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1929), pp. 99–100, no. 1; 136, no. 106 (ill.).

Reginald Howard Wilenski, French Painting (Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1931), p. 262.

Hans Heilmaier, “Alfred Sisley,” Die Kunst 63, 5 (Feb. 1931), p. 137 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Exhibition of the Mrs. L. L. Coburn Collection: Modern Paintings and Watercolors, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1932), pp. 6; 22, no. 31; 53, no. 31 (ill.).

“Mrs. Coburn Leaves 83 Pictures, $200,000 Funds, to Chicago,” Art Digest 6, 18 (July 1, 1932), p. 5 (ill.).

Daniel Catton Rich, “The Bequest of Mrs. L. L. Coburn,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 26, 6 (Nov. 1932), p. 68.

Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, “Renoir,” in Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler, vol. 28, Ramsden–Rosa (Seemann, 1934), p. 170.

Great Portraits from Impressionism to Modernism, with a foreword by Frank Crowninshield, exh. cat. (Wildenstein and Co./Marchbanks, 1938), p. 35, cat. 39.

Lionello Venturi, Les archives de l’impressionnisme: Lettres de Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, et autres; Mémoires de Paul Durand-Ruel; Documents, vol. 2 (Durand-Ruel, 1939), opp. p. 52 (ill.); pp. 261, 310.

Lo Duca, “Il centenario di Alfred Sisley (1839–1939),” Emporium 90, 539 (Nov. 1939), p. 236 (ill.).

Rosamund Frost, Pierre Auguste Renoir, ed. Aimèe Crane, Hyperion Art Monographs (Hyperion/Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1944), p. 21 (ill.).

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (Museum of Modern Art/Simon & Schuster, 1946), pp. 296 (ill.), 313. Translated by Nancy Goldet-Bouwens as Histoire de l’impressionisme (A. Michel, 1955), p. 243.

Milwaukee Art Institute, Masters of Impressionism (Milwaukee Art Institute, 1948), cat. 39.

Marcelle Berr de Turique, Renoir (Phaidon, [1953]), pl. 34.

Paul Gachet, Le docteur Gachet et Murer: Deux amis des impressionnistes (Musées Nationaux, 1956), opp. p. 28, fig. 19; pp. 172; 176.

Paul Gachet, Lettres impressionnistes: Pissarro, Cézanne, Guillaumin, Renoir, Monet, Sisley, Vignon, Van Gogh, et autres . . . (Grasset, 1957), opp. p. 120 (ill.); p. 92.

François Daulte, Alfred Sisley: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint (Durand-Ruel, 1959), p. 33, fig. 3.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 395.

François Fosca, Renoir: L’homme et son oeuvre (A. Somogy, 1961), p. 114. Translated by Mary I. Martin as Renoir: His Life and Work (Prentice-Hall, 1962), p. 114.

Frederick A. Sweet, “Great Chicago Collectors,” Apollo 84, 55 (Sept. 1966), p. 203.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), p. 163 (ill.).

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1, Figures, 1860–1890 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), pp. 136–37, cat. 117 (ill.).

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), p. 95, cat. 138 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 26; 60–61, cat. 16 (ill.); 66; 210; 211; 214.

Raymond Cogniat, Sisley, trans. Alice Sachs (Crown, 1978), pp. 3–4 (ill.).

J. Patrice Marandel, The Art Institute of Chicago: Favorite Impressionist Paintings (Cross River, 1979), pp. 66–67 (ill.).

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism (Abbeville, 1980), pp. 255 (ill.), 438.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism, Tiny Folios (Abbeville, 1980), p. 152, pl. 12.

Sylvie Gache-Patin and Jacques Lassaigne, Sisley (Nouvelles Éd. Françaises, 1983), pp. 51; 52, ill. 57.

Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (Abrams, 1984), pp. 51, 54 (ill.), 74.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 4, Peintures, 1899–1926 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1985), p. 421, letter 2623.

Richard R. Brettell, “The ‘First’ Exhibition of Impressionist Painters,” in The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, ed. Charles S. Moffett, with the assistance of Ruth Berson, Barbara Lee Williams, and Fronia E. Wissman, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), p. 194.

Melissa McQuillan, Impressionist Portraits (Thames & Hudson, 1986), pp. 110–11 (ill.), 197.

Charles S. Moffett, ed., with the assistance of Ruth Berson, Barbara Lee Williams, and Fronia E. Wissman, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), pp. 206; 237, cat. 63 (ill.).

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 36 (ill.), 37, 119.

Nicholas Wadley, ed., Renoir: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, 1987), p. 211 (ill.).

Sophie Monneret, Renoir, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1989), p. 150, cat. 17 (ill.).

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/Yale University Press, 1990), p. 203, fig. 94.

Isabelle Cahn, “Documentary Chronology,” in Alfred Sisley, ed. MaryAnne Stevens, exh. cat. (Royal Academy of Arts, London/Musée d’Orsay/Walters Art Gallery/Yale University Press, 1992), p. 264, fig. 140.

Vivienne Couldrey, Alfred Sisley: The English Impressionist (David & Charles, 1992), p. 47.

Iain Gale, Sisley (Studio, 1992), p. 28 (ill.).

Richard Shone, Sisley, Impressionists/Post-Impressionists (Phaidon, 1992), pp. 108–09, pl. 80; 110; 112; 122–23. Translated into French by Atelier d’Édition Européen as Richard Shone, Sisley (Phaidon, 2004), pp. 108–09, pl. 80; 110; 112; 122.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 66 (ill.).

Anne Distel, Renoir: “Il faut embellir,” Découvertes Gallimard: Peinture 177 (Gallimard/Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993), pp. 38 (ill.), 168. Translated by Lory Frankel as Renoir: A Sensuous Vision (Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 38 (ill.), 168.

Akiya Takahashi and Ruth Berson, 1874 nen—Pari: (dai ikkai inshoha ten) to sono jidai/Paris en 1874: L’année de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Kokuritsu Seiyo Bijutsukan/Yomiuri Shimbunsha, 1994), pp. 113, cat. 44 (ill.); 206.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 1, Reviews (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 120, 129, 176, 180, 190.

Ruth Berson, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886; Documentation, vol. 2, Exhibited Works (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 82, 101 (ill.).

Natalia Brodskaïa, Auguste Renoir: He Made Colour Sing, trans. Paul Williams, Great Painters (Parkstone/Aurora Art, 1996), p. 28 (ill.).

Eliza E. Rathbone, “Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party: Tradition and the New,” in Eliza E. Rathbone, Katherine Rothkopf, Richard R. Brettell, and Charles S. Moffett, Impressionists on the Seine: A Celebration of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” exh. cat. (Phillips Collection/Counterpoint, 1996), p. 31.

Colin B. Bailey, “Portrait of the Artist as a Portrait Painter,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 21; 51, n. 224. Translated as Colin B. Bailey, “Portrait de l’artiste en portraitiste,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, trans. Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), p. 21.

Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 149–51, cat. 26 (ill.); 290, cat. 26. Translated by Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, with support from Nada Kerpan for the texts by Linda Nochlin, as Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 50, n. 224; 149–51, cat. 26 (ill.); 290, cat. 26.

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 10–11; 30; 82, pl. 1; 109.

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), pp. 51 (ill.), 65.

John B. Collins, “Seeking l’Esprit Gaulois: Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette and Aspects of French Social History and Popular Culture” (Ph.D. diss., McGill University, 2001), p. 143.

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), pp. 188 (ill.), 202.

Sylvie Patin, L’impressionisme (Bibliothèque des Arts, 2002), pp. 164; 168, no. 128 (ill.); 299.

Norio Shimada, Inshoha bijutsukan [The history of impressionism] (Shogakukan, 2004), p. 91 (ill.).

Sylvie Patry, “L’invention du modèle,” in Serge Lemoine and Serge Toubiana, Renoir Renoir, exh. cat. (Martinière, 2005), p. 29, n. 8.

Susan Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Chatto & Windus, 2006), p. 211 (ill.).

Nathalia Brodskaïa, Impressionism, trans. Rebecca Brimacombe and Richard Swanson (Parkstone, 2007), pp. 170–71 (ill.).

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, with the collaboration of Camille Frémontier-Murphy, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 1, 1858–1881 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), p. 532, cat. 543 (ill.).

Frances Suzman Jowell, “Impressionism and the Golden Age of Dutch Art,” in Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, ed. Ann Dumas, exh. cat. (Denver Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 93; 104, fig. 40.

Robert McDonald Parker, “Topographical Chronology 1860–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), p. 275. Translated as Robert McDonald Parker, “Chronologie,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), p. 275.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 62 (detail); 63, cat. 22 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 62 (detail); 63, cat. 22 (ill.).

Adrien Goetz, Comment Regarder . . . Renoir (Hazan, 2009), p. 28 (ill.).

Peter Kropmanns, “Renoir’s Friendships with Fellow Artists,” in Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie; The Early Years, ed. Nina Zimmer, exh. cat. (Kunstmuseum Basel/Hatje Cantz, 2012), pp. 247 (ill.); 253, fig. 58; 254.

David Pullins, “Renoir and the Arts of Eighteenth-Century France,” in Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie; The Early Years, ed. Nina Zimmer, exh. cat. (Kunstmuseum Basel/Hatje Cantz, 2012), p. 264.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Deposit Durand-Ruel Paris 3913, livre de dépôt Paris 1879–84

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel Paris 1221

Bernheim-Jeune Documentation

Photograph number

Photo Bernheim-Jeune 10705

Labels and Inscriptions

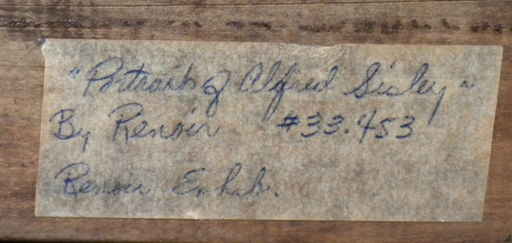

Undated

Inscription

Location: frame

Method: handwritten script (blue pen) on masking tape

Content: “Portrait of Alfred Sisley” / By Renoir #33.453 / Renoir Exhib. (fig. 4.37)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: ovular stamp

Content: TOILES ET COULEURS FINES / REY & Cie / PARIS. / x [5]1 RUE DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULD x (fig. 4.38)

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: stamp

Content: 15 (fig. 4.39)

Stamp

Location: verso of original canvas (covered by lining)

Method: ovular stamp

Content: [. . .] / RE[Y] & [. . .] / PARI[S] / [. . .] RUE [. . .] (fig. 4.40)

Number

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 33.453 (fig. 4.41)

Number

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 41 (fig. 4.42)

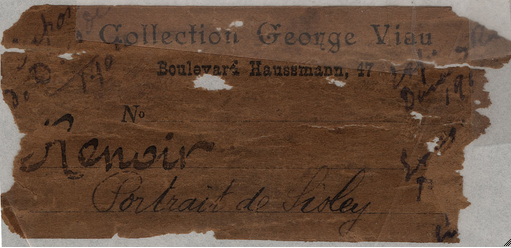

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on printed label

Content: Collection George Viau / Boulevard Haussmann, 47 / No / Renoir / Portrait de Sisley [top left, partial script] Expos[. . .] / de Dresde[. . .] / 1904 [top right, partial script] Expo. / Durand Ru[. . .] / 191[. . .] [center right, partial script] Ex[. . .] (fig. 4.43)

Number

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 01442 (fig. 4.44)

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); fragment preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on blue-and-white label

Content: 41 / Renoir. / [. . .] 00 (fig. 4.45)

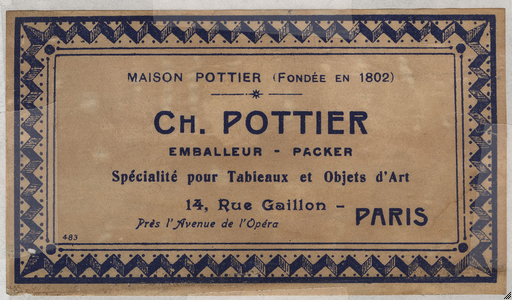

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label

Content: MAISON POTTIER (FONDÉE EN 1802) / CH. POTTIER / EMBALLEUR—PACKER / Spécialité pour Tableaux et Objets d’Art / 14, Rue Gaillon— / PARIS / Près l’Avenue de l’Opéra / 483 (fig. 4.46)

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: typed label

Content: 2677 (fig. 4.47)

Stamp

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: stamp?

Content: Cahier / [. . .]onze / [. . .] / [. . .] (fig. 4.48)

Inscription

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: portrait du peintre / Sisley—[par] Renoir (fig. 4.49)

Number

Location: original stretcher (discarded); 1972 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 9 × 1[6] (fig. 4.50)

Label

Location: original stretcher (discarded); fragment preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label

Content: EXPOSITION D’[. . .] / 1[. . .]17—BARCE[. . .] (fig. 4.51)

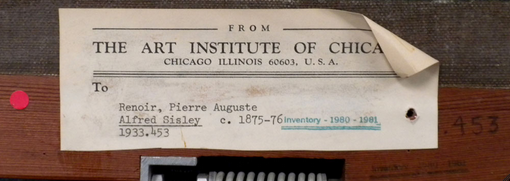

Post-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed and typed label with blue stamp

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / To / Renoir, Pierre Auguste / Alfred Sisley c. 1875–76 / 1933.453 [blue stamp, lower right] Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 4.52)

Label

Location: previous backing board (discarded); preserved in curatorial file

Method: printed and typed label with handwritten script

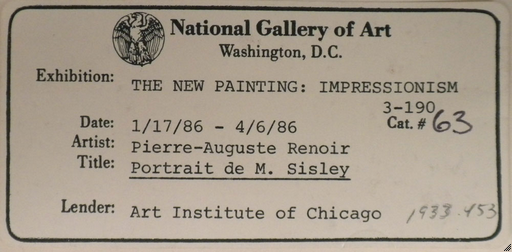

Content: [logo] National Gallery of Art / Washington, D.C. / Exhibition: THE NEW PAINTING: IMPRESSIONISM / 3-190 / Date: 1/17/86–4/6/86 / Cat. # 63 / Artist: Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Title: Portrait de M. Sisley / Lender: Art Institute of Chicago 1933.453 (fig. 4.53)

Label

Location: previous backing board (discarded); preserved in curatorial file

Method: typed label with handwritten script

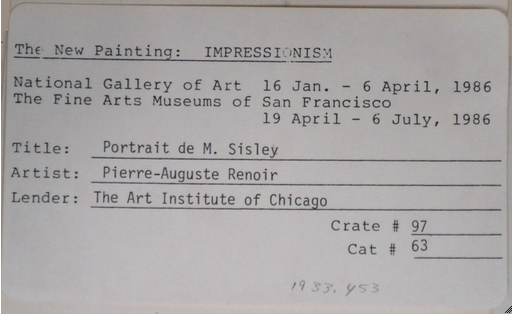

Content: The New Painting: IMPRESSIONISM / National Gallery of Art 16 Jan.–6 April, 1986 / The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco / 19 April–6 July, 1986 / Title: Portrait de M. Sisley / Artist: Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Lender: The Art Institute of Chicago / Crate # 97 / Cat # 63 / 1933.453 (fig. 4.54)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label with handwritten script (red marker, graphite)

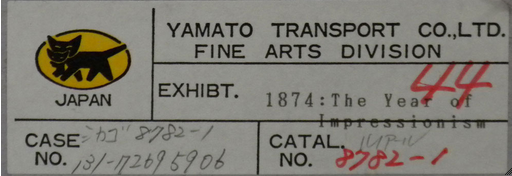

Content: [logo] Japan / YAMATO TRANSPORT CO.,LTD. / FINE ARTS DIVISION / EXHIBT. 1874: The Year of / Impressionism / 44 / CASE [Japanese characters] 8782-1 / NO. 131-[7?]2695906 / CATAL. IUP-IV/ NO. 8782-1 (fig. 4.55)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

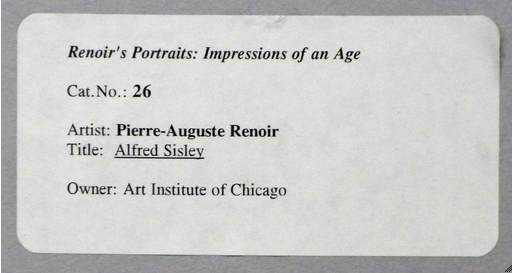

Content: Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age / Cat.No.: 26 / Artist: Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Title: Alfred Sisley / Owner: Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 4.56)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Renoir, Pierre Auguste / title Portrait of Alfred Sisley / medium oil on canvas / credit / acc. # 1933.453 (fig. 4.57)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / “Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age” / October 17, 1997–January 4, 1998 / 26 / Pierr-Auguste [sic] Renoir / Alfred Sisley / The Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 4.58)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

A Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope was used, equipped with an Andor multichannel, Peltier-cooled, open-electrode charge-coupled device detector (Andor DV420-OE322; 1024×256), an Olympus BXFM open microscope frame, a holographic notch filter, and an 1,800-grooves/mm dispersive grating.

The excitation line of an air-cooled, frequency-doubled, He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) was focused through a 20× objective onto the samples, and Raman scattering was back collected through the same microscope objective. Power at the samples was kept very low (never exceeding a few mW) by a series of neutral density filters in order to avoid any thermal damage.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

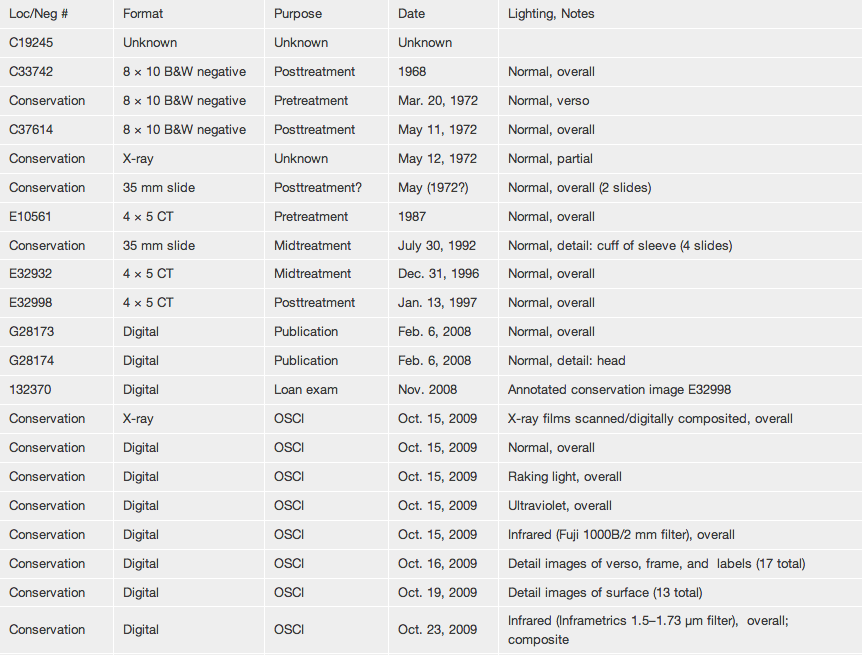

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 4.59).