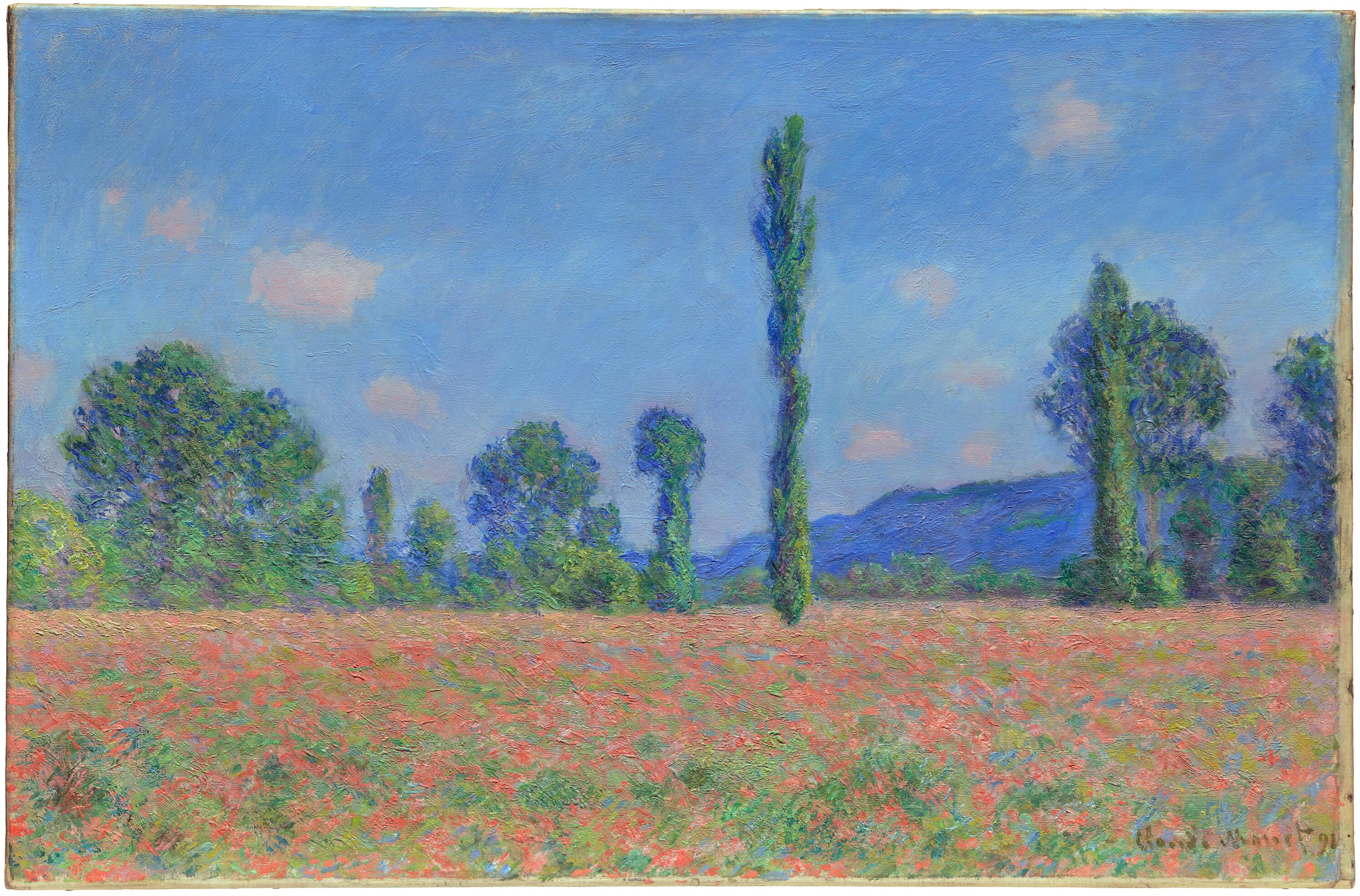

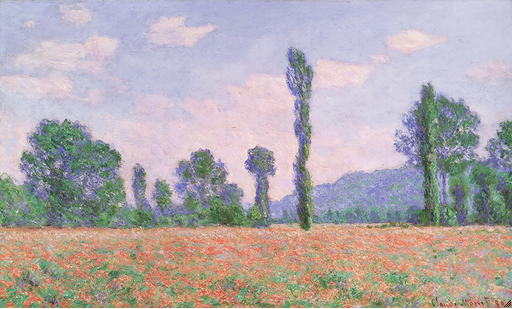

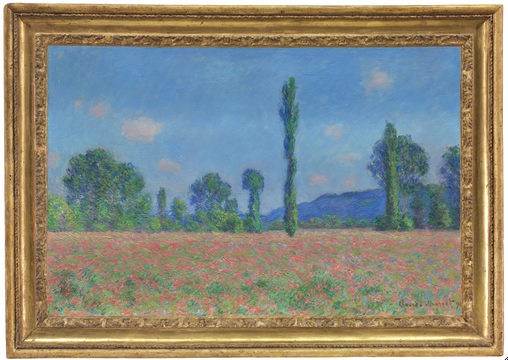

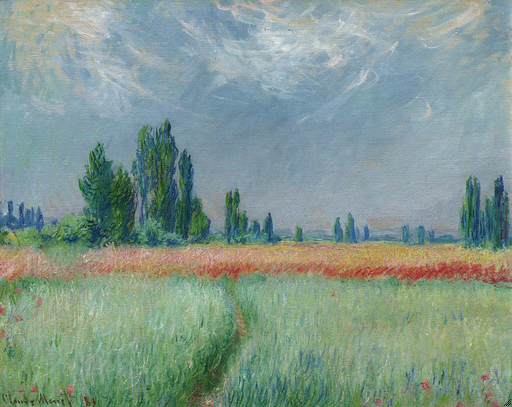

Cat. 26

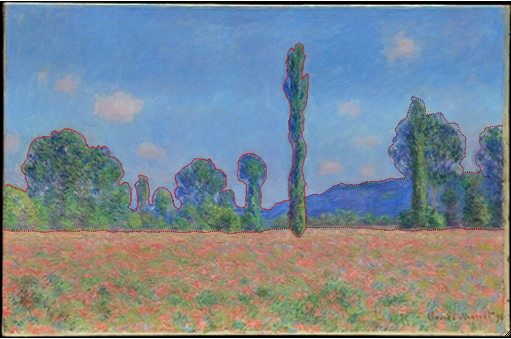

Poppy Field (Giverny)

1890–91

Oil on canvas; 61.2 × 93.1 cm (24 1/16 × 36 5/8 in.)

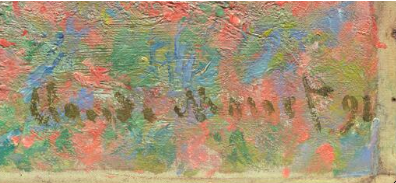

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower right, in dull, yellowish-green paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Kimball Collection, 1922.4465

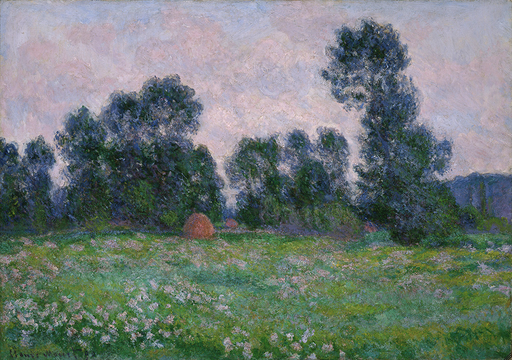

The Fields of Les Essarts: The Miniseries

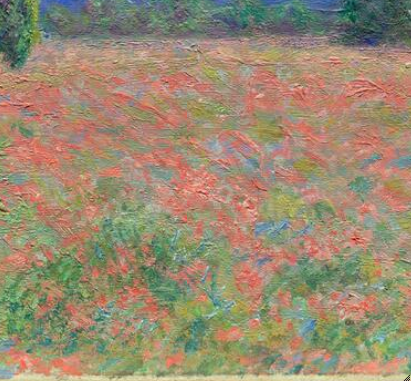

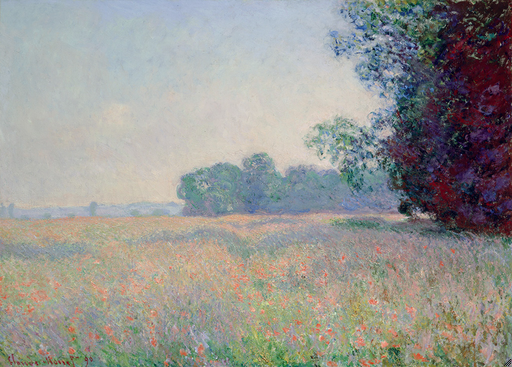

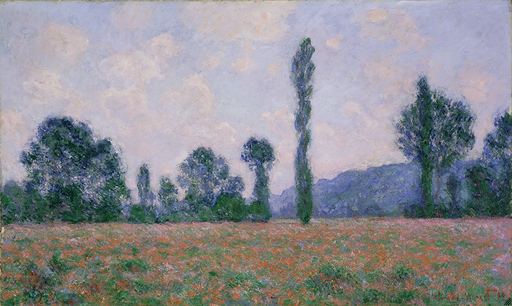

Claude Monet’s important joint exhibition with Auguste Rodin at Galerie Georges Petit (June–Sept. 1889) was followed by an extended period during which Monet did not paint a single picture. Beginning in June 1889 and lasting until the summer of 1890, Monet was thoroughly focused on helping to raise money for the purchase of Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) from the artist’s widow on behalf of the French nation. The Art Institute’s Poppy Field (Giverny) is one of four nearly identical pictures undertaken in July 1890 (fig. 26.1 [W1251], fig. 26.2 [W1252], and Poppies, 1890/91; private collection [W1254]) that together mark his return to work. The poppy group is one of three groups of paintings with similar subjects from this period. Showing fields of poppies, oats, or hay (e.g., fig. 26.3 [W1247] and fig. 26.4 [W1259]) behind Monet’s house at Giverny, these groups, each made up of four or five canvases, are linked not only by the nearly identical subject matter but also by a similar chromatic scheme and handling of paint. After traveling for much of the 1880s, Monet seemed to have been revitalized by the wealth of possibilities offered by the landscape elements in the immediate surroundings at Giverny.

Monet, early in his career, used the term series in a general way to refer to groups of paintings that were in progress at the same time, such as the works he did while at Argenteuil. By the 1890s, however, he applied the word more specifically in reference to “tightly integrated groups of paintings.” For these series, starting around 1889–90, Monet consciously set out to paint a whole sequence of works depicting the same elements in different atmospheric conditions rather than merely versions of the same motif, as was the case at Argenteuil or the Gare Saint-Lazare works.

Monet’s group of paintings from his Creuse River valley campaign in early 1889, especially the twelve canvases showing the same massive rocks at the rivers’ confluence in varying times of day and seasons of the year, can be said to constitute the artist’s first series. While smaller in number, the field compositions that followed the Creuse campaign can be seen as direct precursors to the Stacks of Wheat series (1890–91). Of the four canvases from the poppy group, three are dated—Field of Poppies (fig. 26.1) and Field of Poppies near Giverny (fig. 26.2), both dated 1890, and the Art Institute’s canvas, dated 1891—suggesting that the poppy field paintings, and others from the Giverny field groups, were conceived in the summer of 1890 and put aside by the end of August–beginning of September when Monet became engrossed with the Stacks of Wheat series. That Monet chose at least one representative from each of these small field groups to accompany the fifteen Stacks exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in May 1891 indicates that he recognized their significant role in the conceptual development of what was to be an artistic breakthrough.

Painting the Poppies

The hay, oat, and poppy field compositions were not painted on Monet’s immediate property but in the “area known as Les Essarts, a tract of land that lay between the Epte and the Bras de Limetz, a ten minute walk south of Monet’s water lily pond.” The hills in the background, which rose up in Monet’s backyard, and the fields in and around his property are relatively similar, distinguished by the crops or by invasive wildflowers (fig. 26.5). Only the trees, which connect sky to field and offer a break in the horizontal zones, provide information on Monet’s exact vantage point. For the poppy field canvases (e.g. fig. 26.2), for example, the prominence of the poplar trees and the closer-in view of the hills suggests the area slightly west of Monet’s Giverny pond, looking toward the village of Vernon.

In July 1890 Monet’s future biographer, the politician and journalist Georges Clemenceau, visited the artist while he was at work on these field canvases. In “Révolution de cathédrales,” first published in 1895, Clemenceau’s description of Monet “with his three canvases in front of his poppy field, changing his palette as the sun ran its course,” is contradicted by the nearly identical palette used in the four poppy field paintings. Furthermore, when Clemenceau republished the article in 1928, he changed the details somewhat, relating how the artist worked on “four easels on the banks of the Epte river, in front of the poppy fields bordered by poplar trees.” Although the notion that Monet set up four separate easels has been disputed by many, including Monet’s stepson Jacques Hoschedé, Clemenceau’s eyewitness account and emphasis on the “truth” resulting from Monet’s “four canvases in full light” set the stage for thinking about how these canvases, and the revolutionary “series” that would follow, were painted.

The Landscape Beneath

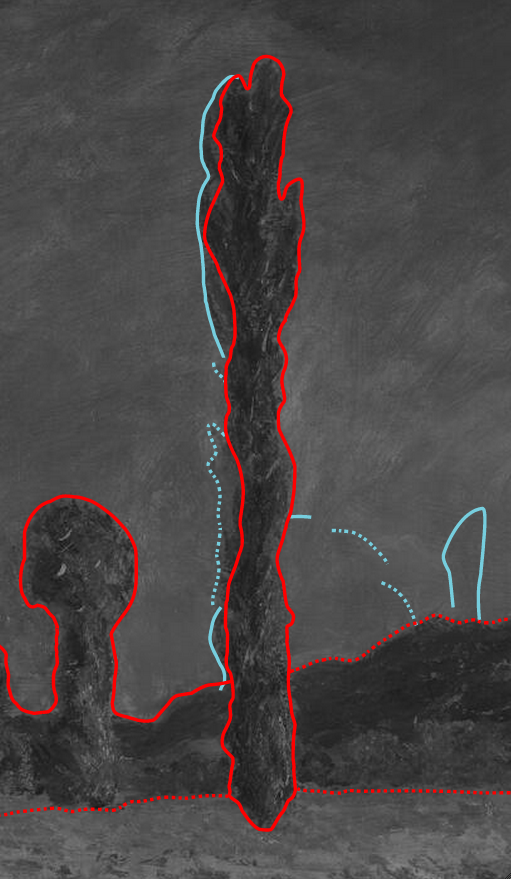

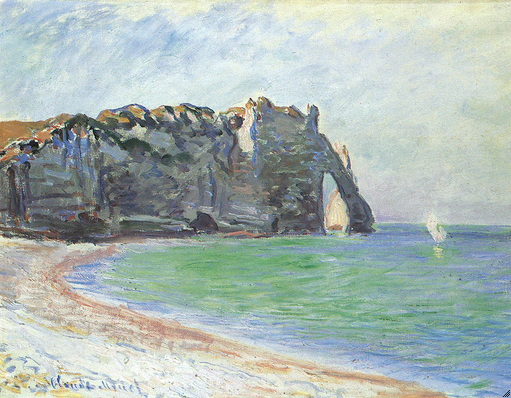

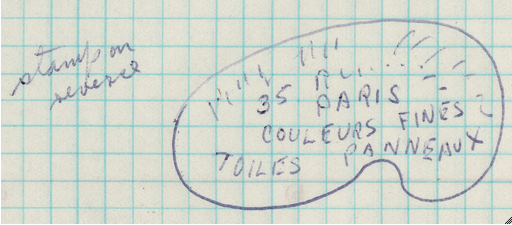

The scale, composition, and surface of the Art Institute’s Poppy Field are very similar to the three other poppy canvases. However, transmitted-infrared and X-ray images show that the Chicago painting was executed over a previous landscape (fig. 26.6). The outlines of what appears to be a cliff are clearly visible in X-ray, as is the active brushwork filling in this large shape, which rises nearly to the top of the canvas. It seems plausible that the composition relates to the Étretat paintings of cliffs from Monet’s campaigns in 1883 and 1885 (e.g., fig. 26.7). In a letter to his companion, Alice Hoschedé, written during his 1885 stay at Étretat, Monet complained that the changing conditions of the sea and the variable weather were causing him great difficulty. This tantalizing and all-too-familiar complaint certainly speaks to the level of frustration Monet experienced in his struggle to put nature onto canvas, but could it also suggest that he abandoned a canvas to be reused several years later? A palette-shaped stamp, once visible on the verso of the original canvas of the Art Institute picture, which has been lined, indicates that it was purchased from Vieille & Troisgros, one of Monet’s preferred suppliers (fig. 26.8). Located on the rue de Laval, Vieille & Troisgros were in partnership between 1879 and 1883. Although not a weave match with the Art Institute’s Étretat pictures from the 1885 campaign (see cat. 21 and cats. 22–23), the canvases for these paintings do exhibit a thread count match to Poppy Field (Giverny); furthermore, because the ground layer is similar to the grounds on the Art Institute’s Étretat works, along with an underlying composition that is strikingly similar to others from the Étretat campaigns, it seems possible that the canvas may have been left in the studio after one of Monet’s trips to Étretat and reused many years later for this series.

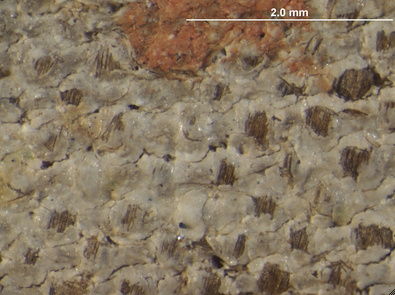

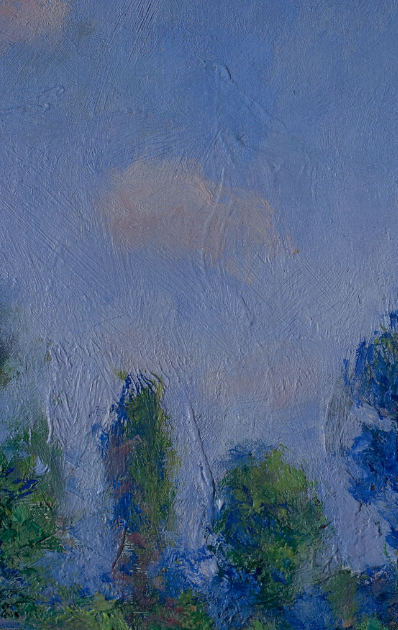

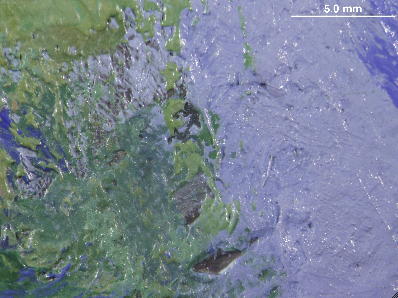

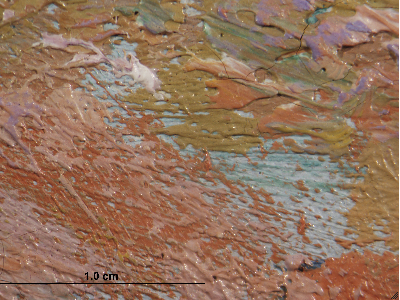

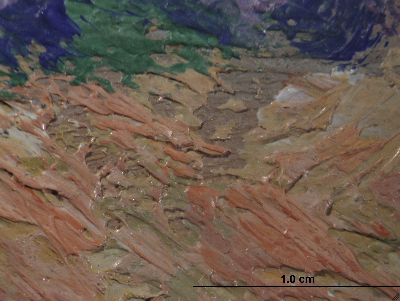

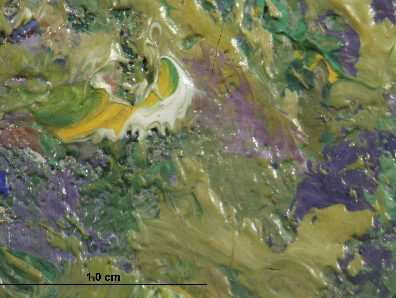

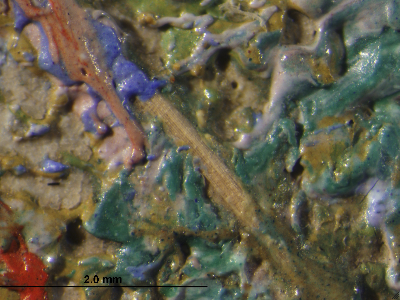

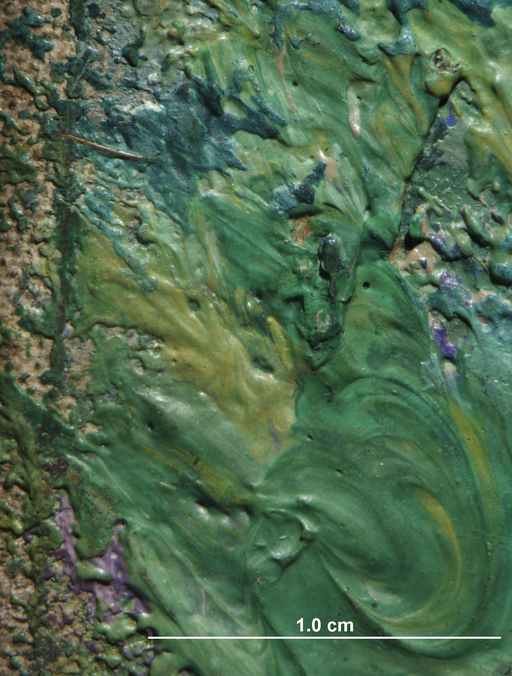

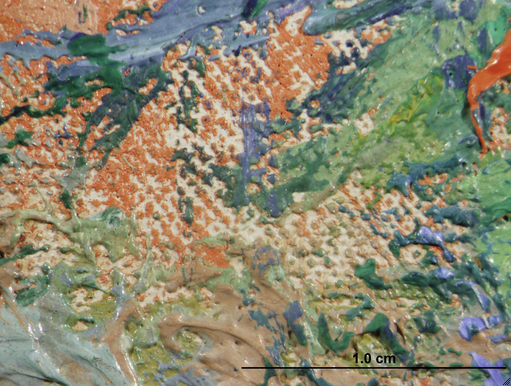

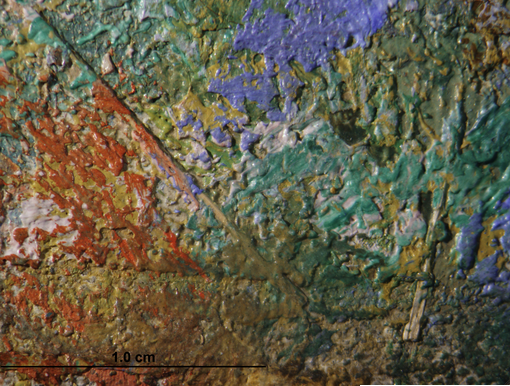

Whatever the circumstances surrounding the reuse of the canvas, the previous composition was not thoroughly scraped off. Areas of the initial landscape, though not entirely resolved, seem to have been painted broadly and rather thickly (fig. 26.9). This brushwork is still visible to the unaided eye, especially in the sky area, where horizontal as well as contour strokes from the earlier painting can be discerned (fig. 26.10). It is clear that Monet also made a few modifications to the final composition, especially the area in the center around the tree: he brought the sky over the green of the foliage and slimmed down the tree’s trunk, in particular on the left-hand side (see Technical Report). Elsewhere, such as in the foreground, where there appears to be no trace of the underlying landscape, there are a few areas where one can see the original primed canvas through the paint layer (fig. 26.11).

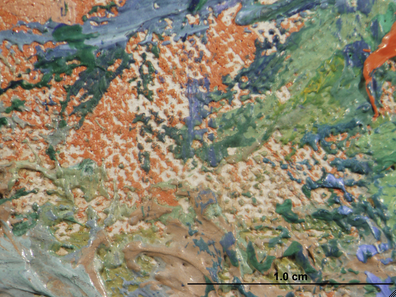

In the Chicago painting and the other near-identical versions, Monet used long, horizontal strokes for grass, to which he added small flicks of colored pigments to evoke poppies bending in the wind (fig. 26.12), a technique similar to his use of blue-white daubs of pigments in the Creuse paintings to suggest rippling water (see cat. 25). This recalls also his depiction of the poppies in full blossom in an earlier painting of a field (fig. 26.13 [W1000]), whose construction, with its deep foreground, high horizon line, and rectangle of poppies receding toward a curving ravine, is entirely different from the gentle, horizontally balanced and decoratively framed poppy fields of the early 1890s. Another earlier composition, Field of Corn (fig. 26.14 [W676]), painted at Vétheuil and dated 1881, features the same compositional division of field, trees, and sky with windswept grasses and billowing clouds that imparts a sense of the momentary, of the on-the-spot execution. The Chicago composition could have been generated in a similar way; bits of plant or grass embedded in the surface (fig. 26.15) confirm that it was at least partially painted en plein air, and indentations and pressure points, noted along the edges of the canvas, moreover, suggest that the artist moved the canvas before it was completely dry and perhaps put it in some kind of traveling case (see Technical Report). The final surface, however, is a combination of densely applied strokes, sometimes wet-in-wet and sometimes wet-over-dry, encrusted with daubs of variegated pigments suggesting work done both outdoors and in the studio. Deceptively simple at first glance, the surface is the result of a complicated technique that in a way calls to mind Georges Seurat’s experiments with divided color in the mid-1880s (e.g., fig. 26.16).

Monet’s attraction to fields of grasses, flowers, and poppies dates to his residence at Argenteuil (e.g., fig. 26.17 [W274]) and would reappear in 1880 and 1881 near Vétheuil (e.g., fig. 26.14) and in 1885 and 1887 near Giverny (e.g., fig. 26.13). But it was the group of poppy canvases that Clemenceau singled out as launching Monet’s “révolution.” In many ways Clemenceau’s statement is an accurate assessment of what would be Monet’s next chapter. Indeed, for the next four years, the artist painted in the vicinity of Giverny, exploring the possibilities of depicting a simple motif in varying degrees of surface complexity, which would be his signature for his major series Stacks of Wheat, Poplars, and Cathedrals.

Gloria Groom

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Claude Monet’s Poppy Field (Giverny) was painted on a pre-primed, no. 30 seascape (marine) standard-size linen canvas. A supplier’s stamp from Vieille & Troisgros was documented on the back of the original canvas. There is a single, off-white ground layer. Technical examination revealed that a different composition was initially painted on the canvas, one in which a large hill or cliff occupied most of the upper left side of the painting. Texture from the brushwork of the earlier composition remains visible on the surface of the painting. It appears that the artist applied a thin, light-hued, intermediate layer over much of the upper part of the canvas before beginning the final painting. The final composition was painted using both wet-over-dry and wet-in-wet paint applications. The sky, hill, and trees in the final composition consist of fairly thick, continuous paint layers, whereas the poppy field was built up using an open network of individual strokes with small passages of exposed ground visible in places and earlier brushstrokes contributing both texture and color to the final surface. In many areas, the paint has a very fluid appearance, suggesting that Monet modified his tube paints with added medium. The artist made some minor adjustments around the edges of some of the trees; the most significant change involved the tallest tree, which was made narrower along its left edge. Some plant matter was found embedded in the paint layer, possible evidence of the artist having worked outdoors.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 26.18).

Signature

Signature/Stamp

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 91 (lower right, in dull, yellowish-green paint) (fig. 26.19). Some of the underlying brushstrokes were still wet when the painting was signed (fig. 26.20).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions were approximately 60 × 92 cm. This corresponds to a no. 30 seascape (marine) standard-size canvas.

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 28.6V (0.7) × 27.6H (0.9) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft. No weave matches were detected with other Monet paintings analyzed for this project.

Canvas characteristics

There is mild, relatively even cusping on the top, bottom, and right edges and more pronounced cusping on the left edge, which is also an unprimed edge (see Ground application/texture).

Stretching

Current stretching: Dates to the 1963 treatment (see Conservation History). Copper tacks are spaced 8–10 cm apart.

Original stretching: Tack holes are spaced approximately 5–8 cm apart. The original tack holes correspond to the cusping pattern on all sides.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: ICA spring stretcher dates to 1963 treatment (see Conservation History). Depth: 2.5 cm.

Original stretcher: Discarded. The pre-1963-treatment stretcher was probably the original stretcher. The 1963 examination report describes it as a five-piece stretcher with a vertical crossbar, mitred joints, and keys (see Conservation History). Depth: Not documented. Based on intermittent creases along the tacking edges, where it appears that excess fabric may have been folded over the back edge of the original stretcher, the depth appears to have been 1.5–2 cm.

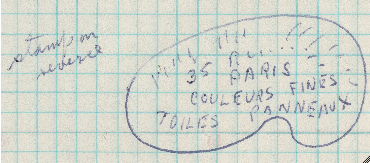

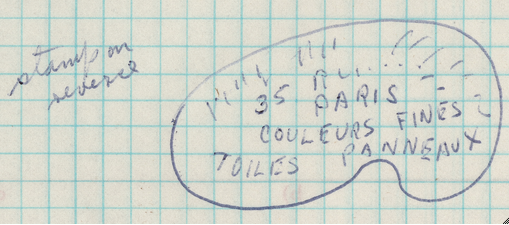

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

A stamp on the back of the original canvas was transcribed before the painting was lined in 1963 (see Conservation History) (text within palette-shaped frame): [. . .] 35 R[UE] [. . .] / PARIS / COULEURS FINES / TOILES PANNEAUX (fig. 26.21).

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

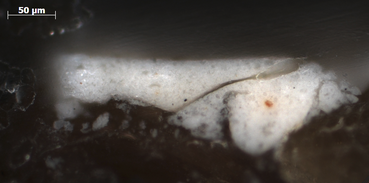

The ground layer extends to the edges of the top, bottom, and right tacking margins but stops short of the left edge where the unprimed canvas is visible (fig. 26.22). This indicates that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed fabric on three sides; the left edge probably corresponds to the edge of the larger roll of canvas that was attached to the commercial priming frame. The ground consists of a single layer that ranges from approximately 15 to 100 µm in thickness (fig. 26.23). Several tiny bubble holes were observed in the ground layer.

Color

The ground is off-white with fine black particles and possibly a few red particles visible microscopically (fig. 26.24, fig. 26.25).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the ground contains lead white and calcium carbonate (chalk) with traces of iron oxide, silica, and various silicates. Binder: Oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR) or microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

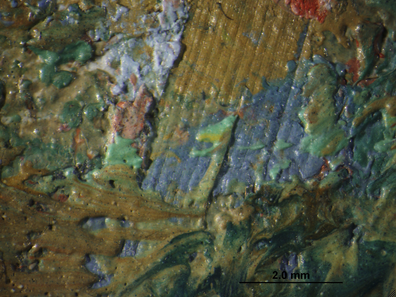

Overall, the painting was heavily worked up, as evidenced by the relative density of the paint layers in the X-ray, which also shows extensive brushwork in the central and upper left areas that is unrelated to the final composition (fig. 26.26). The nature of this brushwork is clarified somewhat by the transmitted-infrared image, which clearly shows a much higher horizon line, possibly related to a hill or a cliff, in the upper left half of the painting in the earlier composition (fig. 26.27). The horizon line extends up to 15 cm from the top edge of the canvas at its highest point. The texture of the brushstrokes used to delineate the upper edge of this landform remains visible on the surface of the painting (fig. 26.28). Near the central area of the canvas, there are some arch-shaped and vertical forms that could be related to contours in this form (fig. 26.29). In some places, the brushwork of the underlying composition was quite thickly applied, which may indicate that the earlier painting was developed beyond simply an initial lay-in of the composition (fig. 26.30); however, no features from the earlier composition were visible on the right side or in the foreground of the canvas. The paint in the sky is fairly continuous and obscures any view of underlying paint colors or brushstrokes related to the first painting. In a few places, a warm off-white-colored layer is visible in the area of the painted-out forms in the upper left, but this seems to be a broadly applied layer, perhaps used to cover the earlier forms or to provide a general tone before beginning the final composition. Only in a few small places, through gaps in the upper brushwork, some darker tones are visible, which may be related to the first composition; for example, the dark-brownish-gray paint underneath the foliage and sky on the right side of the third tree from the left (fig. 26.31).

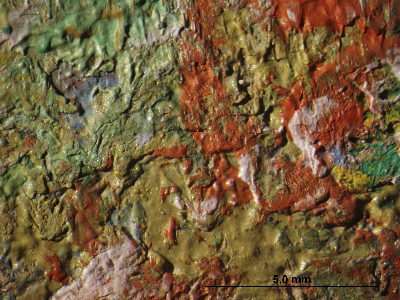

As mentioned above, the final composition appears to have been painted on top of a broadly applied intermediate layer. The mainly horizontal brushstrokes of this layer can be seen in the X-ray, in the area of the painted-out forms and underneath the trees of the final painting (fig. 26.32). The texture of these brushstrokes is visible on the surface of the painting and, in a few places, where it was not completely covered by subsequent paint applications, the layer appears to be light in tone: a warm, off-white color (fig. 26.33). In the poppy field composition, the brushwork in the sky is rather vigorous compared with the calm appearance of the sky in the final painting. This is due mainly to highly brushmarked underlayers, including some quickly applied, textural zigzag strokes, which may be related to the earlier composition since they seem to be concentrated outside the area occupied by the landform in the earlier composition. These brushmarks were dry when the blue of the sky was built up over top (fig. 26.34). The warm, pinkish-gray paint of the clouds was applied last, when the underlying blue paint was already dry. The clouds on the left side consist of fairly thickly applied strokes that mostly conceal the blue paint of the sky (fig. 26.35); on the right side, the paint of the clouds is thinly applied and appears to have been wiped or otherwise partially removed, revealing the peaks of the ridges of the blue strokes underneath (fig. 26.36). In the poppy field, an underlayer consisting of thinly applied, mainly horizontal strokes of pale-green paint covers a large portion of the foreground and appears to have been applied directly over the ground layer (fig. 26.37, fig. 26.38). Ground remains visible in places due to the open brushwork, especially in the lower left corner (fig. 26.39). Texture throughout the poppy field was built up using relatively long, diagonal and zigzag strokes of thick paint (often mixtures of lead white and vermilion), which appear radio-opaque (fig. 26.40). At the same time, a relatively solid horizontal band of brushstrokes was applied along the far edge of the field (fig. 26.41, fig. 26.42). The thick brushstrokes and narrow tonal range used in this area blur together when viewed from a distance, providing a sense of recession into space (fig. 26.43). The rest of the surface of the field was then broken up with more discrete touches of green, red, yellow, and blue, which become increasingly intense toward the foreground.

In general, the upper paint layers were worked up wet-in-wet, using paint that had a rather fluid consistency. The individual strokes do not hold the peaks of the brush ridges, resulting in relatively smooth surfaces, which suggest that the artist added medium or thinner to his tube paints to adjust the consistency (fig. 26.44). In some places, the fluidity of the paint has caused colors to swirl together on the canvas (fig. 26.45). Much of the crisp, brush-marked texture visible on the surface of the painting, which is accentuated when the work is viewed in raking light, was built up from the underlying layers that were allowed to dry before subsequent layers of more fluid paint were applied on top. Where the more fluid paint is thickly applied, it can obscure the underlying texture; where it is thinly applied, it often conforms to the ridges of the strokes underneath, creating a varied surface (fig. 26.46). In spite of the relatively thick buildup of paint overall, the texture of the canvas weave remains evident in some places where the paint is more thinly applied, throughout the sky and the field (fig. 26.47). The trees and hill, on the other hand, are more thickly built up, which largely obscures the canvas texture (fig. 26.48).

A few changes were made around the edges of some of the trees late in the painting process. In these areas, the artist reduced the foliage by extending blue paint from the sky over the blue and green strokes of the leaves, which still remain faintly visible on the surface (fig. 26.49). This is most evident along the left edge of the tallest tree (fig. 26.50). The infrared reflectogram shows that this tree was originally significantly wider, especially near the top (fig. 26.51).

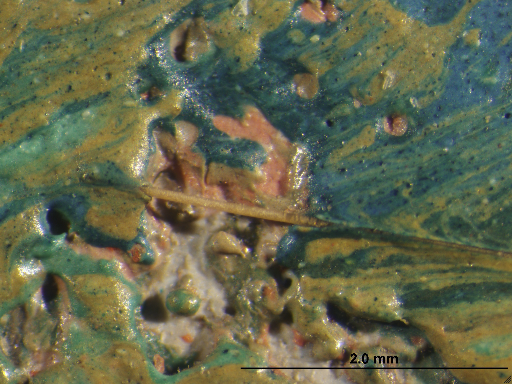

Some plant matter was observed embedded in the paint layer, along the lower edge of the painting (fig. 26.52, fig. 26.53). In some places, only the impression of the material in the once soft paint remains, either having fallen from the surface or been plucked out by the artist. These accretions occurred during the painting process, since subsequent brushstrokes were observed to pass over both the material (fig. 26.54) and the impressions (fig. 26.55). Several gouges and areas of topped impasto, which occurred when the paint was still soft, were observed under magnification throughout the field. Along the bottom edge, areas of flattened paint were also seen (fig. 26.56). These are probably accidents from handling and/or transporting the painting before it was completely dry.

Painting tools

Brushes including 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 cm width, flat ferrule (based on width and shape of brushstrokes). Several brush hairs are embedded in the paint layers (fig. 26.57).

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cadmium yellow, chrome yellow, vermilion, red lake, emerald green, viridian, cobalt blue, and ultramarine blue. UV fluorescence suggests that the artist used red lake throughout the poppy field.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting is currently unvarnished. In 1997, the synthetic varnish applied in 1963 was removed. The 1963 examination report states that the painting was unvarnished at that time. (see Conservation History). The painting has a soft, relatively matte appearance with subtle variations in gloss depending on the qualities of the paint.

Conservation History

In 1963, the canvas was wax-resin lined and mounted on an ICA spring stretcher. The treatment report states that “the new stretcher was made a bit larger than the painting so that all parts of the painting would be exposed.” Surface grime was removed. A spray coat of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA was applied. Retouching was carried out along the right edge where a significant border of unpainted ground was exposed after restretching. A final spray coat of methacrylate resin L-46 was applied.

In 1997, the synthetic varnish applied in 1963 was removed.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition. The canvas is wax-resin lined and stretched taut on an ICA spring stretcher. The tacking edges are deteriorated from wear and handling with moderate associated loss of ground on the edges and foldovers. There are a few tiny paint losses, mainly along the bottom edge. Small areas of flattened and abraded paint appear to be due to handling when the paint was still soft. There is some flattened paint and wood fibers around the edges, probably caused by framing while the paint was still soft. Cracking is minimal and, where present, is very fine. There are very light stretcher-bar cracks in the area of the original vertical crossbar, as well as some microscopic drying cracks specific to the paint of the signature and date (fig. 26.58). Some retouching residues are visible around the edges. There are a few tiny accretions in the sky and some gold from the frame around the edges. The painting is currently unvarnished.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

Current frame: The frame is not original to the painting. It is an Italian, eighteenth-century, Salvator Rosa, scotia frame with carved and applied ribbon and reel at the top of the scotia and carved ogee acanthus-leaf-and-shield sight molding. The frame is water gilded over a thin, yellowish-raw sienna colored bole. Only the top convex molding is burnished; the other gilded surfaces are matte. The sides and back fillet edge are not gilded and are painted in raw sienna. The frame retains the original glue size. The mitered face and sight moldings are poplar and are applied to a half-lapped cassetta of poplar and sweet chestnut. The ribbon-and-reel ornament was carved and gilded independently and pinned to the fillet top of the scotia. The molding, from perimeter to interior, is scotia side; convex molding with treacle back; fillet with applied three-quarter-round ribbon-and-reel molding; scotia; and ogee with acanthus-leaf-and-shield motif (fig. 26.59).

Previous frame (installed by 1975): The work was previously housed in a mid-twentieth- century, American, silver-gilt, cushion-shaped molding frame with a ribbon and reel on the outer edge and an independent liner (fig. 26.60). By 1995, the frame was reduced in size and the linen liner removed.

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Possibly sold by the artist to Hamman, Paris, as agent for Knoedler and Company, New York, Sept. 1891.

Acquired by Potter Palmer, Chicago, by Jan. 24, 1893.

On deposit from Potter Palmer, Chicago, to Durand-Ruel, New York, by Jan. 24, 1893.

Sold by Potter Palmer, Chicago, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Jan. 24, 1893, for 5,000 francs.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to William W. Kimball, Chicago, Apr. 16, 1901, for $3,200.

By descent from William W. Kimball (died 1904), Chicago, to his wife, Mrs. William W. (Evaline M. Cone) Kimball, Chicago.

Bequeathed by Mrs. William W. (Evaline M. Cone) Kimball (died 1921), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1922.

Exhibition History

New York, Fine Arts Society Building, Loan Exhibition, Feb. 1893, cat. 40, as Champ des Coquelicots, Lent by Mr. Durand-Ruel.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Exposition of Forty Paintings by Claude Monet, Jan. 12–27, 1895, cat. 3, as Coquelicots. 1891.

Possibly Boston, St. Botolph Club, Exhibition of Paintings by Claude Monet, Feb. 4–16, 1895, cat. 25, as Coquelicots. 1891.

Buffalo (N.Y.), Library Building, Buffalo Society of Artists, Fifth Annual Exhibition, Mar. 23–Apr. 11, 1896, cat. 57 (ill.), as Landscape, Durand-Ruel.

Possibly Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, Second Annual Exhibition, Nov. 4, 1897–Jan. 1, 1898, cat. 156, as Red Poppies.

Possibly Omaha, Neb., Trans–Mississippi and International Exposition, Fine Arts Exhibit, June 1–Nov. 1, 1898, cat. 378, as Coquelicots. Loaned by Durand–Ruel, Paris.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Paintings of Claude Monet, Apr. 1–June 15, 1957, no cat. no.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 84 (ill.). (fig. 26.61)

Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, June 27–Aug. 31, 1980, cat. 13 (ill.).

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, June 28–Sept. 16, 1984, cat. 103 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 23, 1984–Jan. 6, 1985; Paris, Galeries Nationales d’Exposition du Grand Palais, as L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, Feb. 4–Apr. 22, 1985, cat. 102 (ill.).

Auckland City Art Gallery, Claude Monet: Painter of Light, Apr. 29–June 9, 1985, cat. 20 (ill.); Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, June 21–Aug. 4, 1985; Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, Aug. 14–Sept. 29, 1985.

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Monet in the ’90s: The Series Paintings, Feb. 7–Apr. 29, 1990, cat 12 (ill.); Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, May 19–Aug. 12, 1990; London, Royal Academy of Arts, Sept. 7–Dec. 9, 1990. (fig. 26.62)

Art Institute of Chicago, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, July 22–Nov. 26, 1995, cat. 95 (ill.). (fig. 26.63)

Omaha, Neb., Joslyn Art Museum, On View to the World: Paintings at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition, 1898, May 30–Aug. 16, 1998, no cat.

Florence, Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti, Claude Monet: La poesia della luce; Sette capolavori dell’Art Institute di Chicago a Palazzo Pitti, June 2–Aug. 29, 1999, no cat. no. (ill.).

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Claude Monet: Effet de soleil—Felder im Frühling, May 20–Sept. 24, 2006, cat. 30 (ill.).

Musée d’Art Américain Giverny/Terra Foundation for American Art, Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915, Apr. 1–July 1, 2007, no. cat. no. (ill.); San Diego Museum of Art, July 22–Oct. 1, 2007 (Giverny only).

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 74 (ill.).

Selected References

American Fine Arts Society, Catalogue: Loan Exhibition, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Society Building, 1893), p. 39, cat. 40.

Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, Exposition of Forty Paintings by Claude Monet, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, 1895), cat. 3.

Possibly St. Botolph Club, Exhibition of Paintings by Claude Monet, exh. cat. (St. Botolph Club, 1895), cat. 25.

Georges Clemenceau, “Révolution de cathédrales,” La justice, May 20, 1895, p. 1.

Georges Clemenceau, Le grand Pan (Charpentier, 1896), p. 431.

Buffalo, N.Y., Society of Artists, Catalogue of the Fifth Annual Exhibition, exh. cat. (Buffalo Society of Artists, 1896), p. 15, cat. 57 (ill.).

Possibly Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, Second Annual Exhibition, exh. cat. (Carnegie Art Galleries, 1898), cat. 156.

Possibly Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, Official Catalogue of Fine Arts Exhibit, Illustrated, exh. cat. (Klopp & Bartlett Co., 1898), p. 88, cat. 378.

Art Institute of Chicago, Handbook of Sculpture, Architecture, Paintings, and Drawings, pt. 2, Paintings and Drawings (Art Institute of Chicago, 1920), p. 60, cat. 762.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Accessions and Loans,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 16, 7 (Dec. 1922), p. 98.

M. C., “Monets in the Art Institute,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago19, 2 (Feb. 1925), p. 19.

Georges Clemenceau, Claude Monet, les Nympheas (Librairie Plon, 1928), p. 85.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1932), p. 164, cat. 22.4465.

Oscar Reuterswärd, Monet: En konstnärshistorik (Bonniers, 1948), p. 289.

Art Institute of Chicago,“Catalogue,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), pp. 33.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 321.

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 141, cat. 84 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 3, Peintures, 1887–1898 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1979), p. 132; 133, cat. 1253 (ill.).

Robert Herbert, “Method and Meaning in Monet,” Art in America 67, 5 (Sept. 1979), pp. 98, 102.

Musée Toulouse-Lautrec and Art Institute of Chicago, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, exh. cat. (Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, 1980), pp. 33, cat. 12 (ill.); 67.

Andrea P. A. Belloli, ed., A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), p. 365.

Richard Brettell, “The Fields of France,” in A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, ed. Andrea P. A. Belloli, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 256; 260; 261, no. 103 (ill.).

Richard Brettell, “La champagne française,” in Réunion des Musées Nationaux, L’impressionnisme et le paysage français, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), pp. 276; 278; 279, no. 102 (ill.).

Charles F. Stuckey, ed., Monet: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1985), pp. 176; 192, pl. 80.

Auckland City Art Gallery, Claude Monet: Painter of Light, exh. cat. (Auckland City Art Gallery/NZI, 1985), pp. 80–81, cat. 30 (ill.).

John House, Monet: Nature into Art (Yale University Press, 1986), pp. 197–98; 199, fig. 251.

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 82 (ill.), 83, 118.

Paul Hayes Tucker, Monet in the ’90s: The Series Paintings, exh. cat. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Yale University Press, 1989), pp. 71; 76, pl. 19; 273, n. 12; 295, cat. 12.

Anna Barskaïa and Evguenia Gueorguievskaïa, Claude Monet: Tableaux des musées d’URSS, introduction by Nina Kalitina, trans. Dominique Maliarevitch-Millot and Olga Mandryka (Cercle d’Art, 1990), p. 112.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 5, Supplément aux peintures: Dessins; Pastels; Index (Wildenstein Institute, 1991), p. 200, letter 2837.

Sylvie Patin, Monet: “Un oeil . . . mais, bon Dieu, quel oeil!” (Gallimard/Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1991), pp. 102 (ill.), 103 (detail), 172. Translated by Anthony Roberts as Monet: The Ultimate Impressionist (Abrams, 1993), pp. 102 (ill.), 103 (detail), 171.

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 43–44; 85, pl. 14; 108.

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 116, cat. 95 (ill.); 226; 227.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism, cat. rais., vol. 1 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 262 (ill.), 273.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 3, Nos. 969–1595 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 477, cat. 1253 (ill.); 478.

Heide Michels, Monet’s House: An Impressionist Interior, trans. Helen Ivor (Clarkson Potter, 1997), pp. 80–81 (ill.).

Christopher Burbach, “Joslyn Show: Art of 1898 Expo,” Morning World-Herald, June 2, 1998, pp. 35, 37.

Simonella Condemi and Andrew Forge, Claude Monet: La poesia della luce; Sette capolavori dell’Art Institute di Chicago a Palazzo Pitti, exh. cat. (Giunti Gruppo, 1999), pp. 32, 33 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), p. 131 (ill.).

Susan G. Larkin, American Impressionism: The Beauty of Work, with entries by Susan G. Larkin and Arlene Katz Nichols, exh. cat. (Bruce Museum of Arts and Science, 2005), p. 46, fig. 37.

Christofer Conrad, “From Impression to Organization of the Picture,” in Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad, with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Fields in Spring, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz, 2006), pp. 96–97, fig. 70; 100.

Christian von Holst, “Travel Impressions,” in Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad, with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Fields in Spring, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz, 2006), pp. 38; 41, fig. 18.

Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad, with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Fields in Spring, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz, 2006), pp. 116–17 (detail); 157, cat. 30; 163.

Katherine M. Bourguignon, ed., Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915, exh. cat. (Terra Foundation for American Art/Musée d’Art Américain Giverny/University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 77, 89 (ill).

Margaret Werth, “‘A Long Entwined Effort’: Colonizing Giverny,” in Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915, ed. Katherine M. Bourguignon, exh. cat. (Terra Foundation for American Art/Musée d’Art Américain Giverny/University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 59.

Eric M. Zafran, “Monet in America,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein and Co., 2007), p. 104.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 22; 154 (detail); 155, cat. 74 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 22; 154 (detail); 155, cat. 74 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Deposit Durand-Ruel New York 5041

New York Deposit Book 1888–1893

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 1015

New York Stock Book 1894–1905

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Label

Location: stretcher

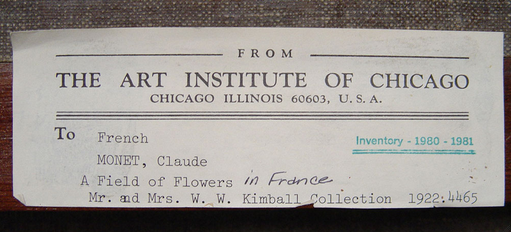

Method: printed label with typewritten and handwritten script and green-ink inventory stamp

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / To / French / MONET, Claude / A Field of Flowers in France / Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Kimball Collection 1922.4465

Stamp: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 26.64)

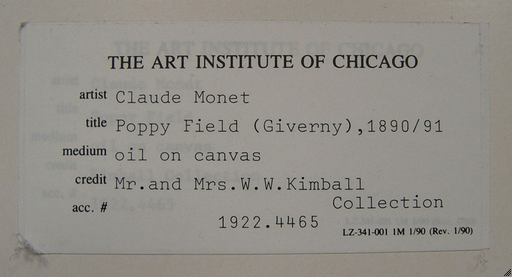

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Claude Monet / title Poppy Field (Giverny), 1890/91 / medium oil on canvas / credit Mr. and Mrs. W.W. Kimball / Collection / acc.# 1922.4465 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 26.65)

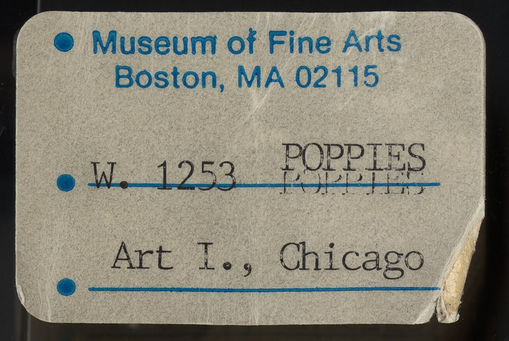

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: Museum of Fine Arts / Boston, MA 02115 / W. 1253 POPPIES / Art I., Chicago (fig. 26.66)

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: Museum of Fine Arts / Boston, MA 02115 / W. 1253 POPPIES / Art I., Chicago (fig. 26.67)

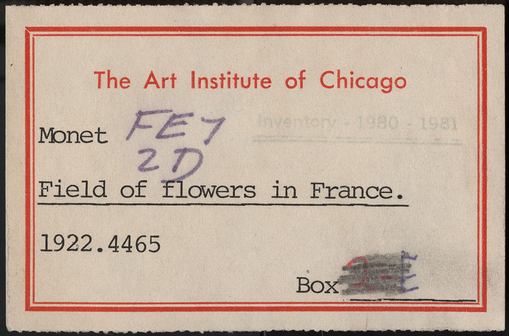

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with typewritten and handwritten script and green-ink inventory stamp

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / Monet FE7 / 2D / Field of flowers in France. / 1922.4465 / Box 2-E [2-E crossed out]

Stamp: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 26.68)

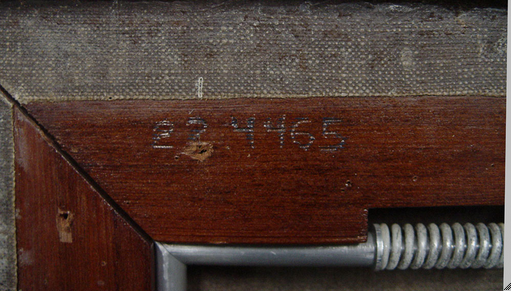

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 22.4465 (fig. 26.69)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: canvas; transcription in conservation file

Method: not documented, text within palette-shaped frame

Content: [. . .] / 35 R[UE] . . . / PARIS / COULEURS FINES / TOILES PANNEAUX (fig. 26.70)

Post-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: green-ink stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 26.71)

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with typewritten script

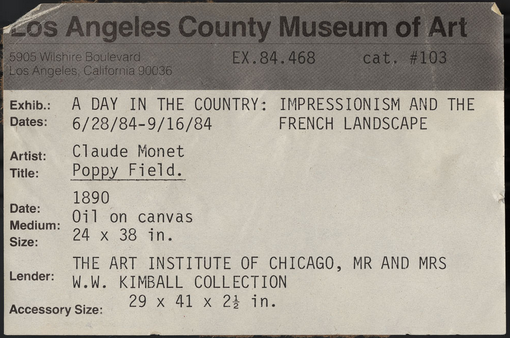

Content: Los Angeles County Museum of Art / 5905 Wilshire Boulevard / Los Angeles, California 90036 / EX. 84.468 / cat. #103 / Exhib.: A DAY IN THE COUNTRY: IMPRESSIONISM AND THE / FRENCH LANDSCAPE / Dates: 6/28/84–9/16/84 / Artist: Claude Monet / Title: Poppy Field. / Date: 1890 / Medium: Oil on canvas / Size: 24 × 38 in. / Lender: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, MR AND MRS / W.W. KIMBALL COLLECTION / Accessory Size: 29 × 41 × 2 1/2 in. (fig. 26.72)

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

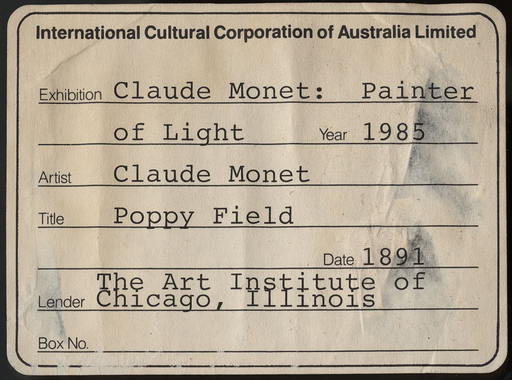

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: International Cultural Corporation of Australia Limited / Exhibition Claude Monet: Painter / of Light Year 1985 / Artist Claude Monet / Title Poppy Field / Date 1891 / Lender The Art Institute of / Chicago, Illinois / Box No. [blank] (fig. 26.73)

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with stamped and handwritten script

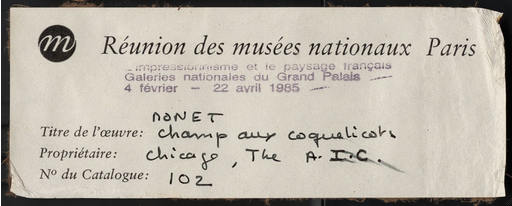

Content: [Logo] Réunion des musées nationaux Paris / L’Impressionnisme et le paysage français / Galeries nationales du Grand Palais / 4 février–22 avril 1985 / MONET / Titre de l’oeuvre: champ aux coquelicots / Propriétaire: Chicago, The A.I.C. / No du Catalogue: 102 (fig. 26.74)

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label

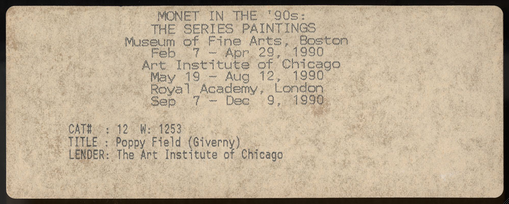

Content: MONET IN THE ’90s: / THE SERIES PAINTINGS / Museum of Fine Arts, Boston / Feb 7–Apr 29, 1990 / Art Institute of Chicago / May 19–Aug 12, 1990 / Royal Academy, London / Sep 7–Dec 9, 1990 / CAT#: 12 W: 1253 / TITLE: Poppy Field (Giverny) / LENDER: The Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 26.75)

Label

Location: not documented; preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / “Claude Monet: 1840–1926” / July 14, 1995–November 26, 1995 / Catalog: 95 / Poppy Field (Giverny) / Champs aux coquelicots / The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. W. W. / Kimball Collection (1922.4465) (fig. 26.76)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: Giverny Impressionniste: une colonie d’artistes, / 1885–1915/Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915 / Musée d’art Américain Giverny, April 1–June 30, 2007 / San Diego Museum of Art, July 21–Sept. 30, 2007 / TR.2007.1.1 / Monet, Claude / Poppy Fields / Oil on canvas (fig. 26.77)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm); Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; and Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75H (PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

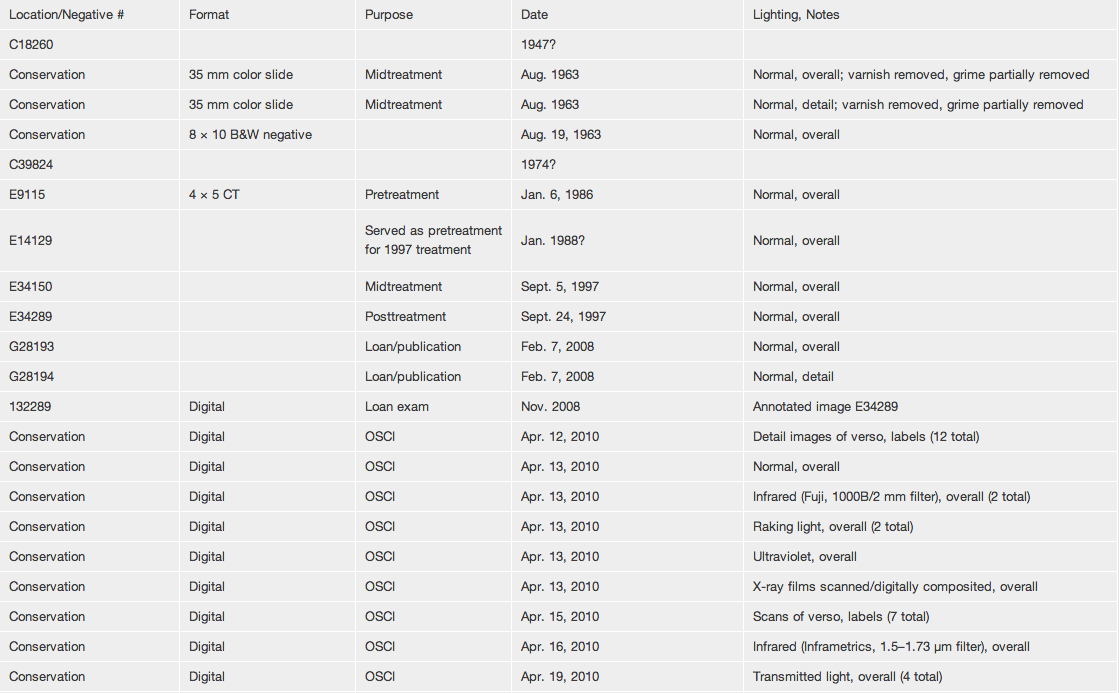

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 26.78).