“A Chicago Boy”: The Second City Meets James McNeill Whistler

Sarah Kelly Oehler

On October 12 and October 13, 1886, the Chicago Tribune published two brief pieces on James McNeill Whistler. The first reported, “The English artist, James McNeill Whistler, is making speedy preparations to come to this country,” a trip that never occurred (fig. 1). The following day the newspaper published a response from Joseph P. Roles, the rector of St. Mary’s Church, the oldest Catholic church in Chicago. Roles argued that the Tribune had “decided the question of his nationality too hastily” by describing him as English. Roles was correct; although an expatriate who had spent his career in England and France, Whistler was in fact American, having been born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1834. But the rector then proceeded to make additional claims that directly connected Whistler to the city of Chicago. He offered evidence from church records that “Maj. Whistler’s family, about six,” had been among a group of local Catholics who petitioned the bishop of St. Louis, Missouri, in 1833 to establish St. Mary’s as the first parish in Chicago and became its founding members. He explained that Major Whistler was at that time commander of Fort Dearborn—the United States fort that led to the founding of the city of Chicago—and the father of George Washington Whistler, and thus the grandfather of James McNeill Whistler. He therefore concluded of James McNeill Whistler, “I consider him, until I am better informed, a Chicago boy and a grandson of one of the old parishioners of St. Mary’s.”

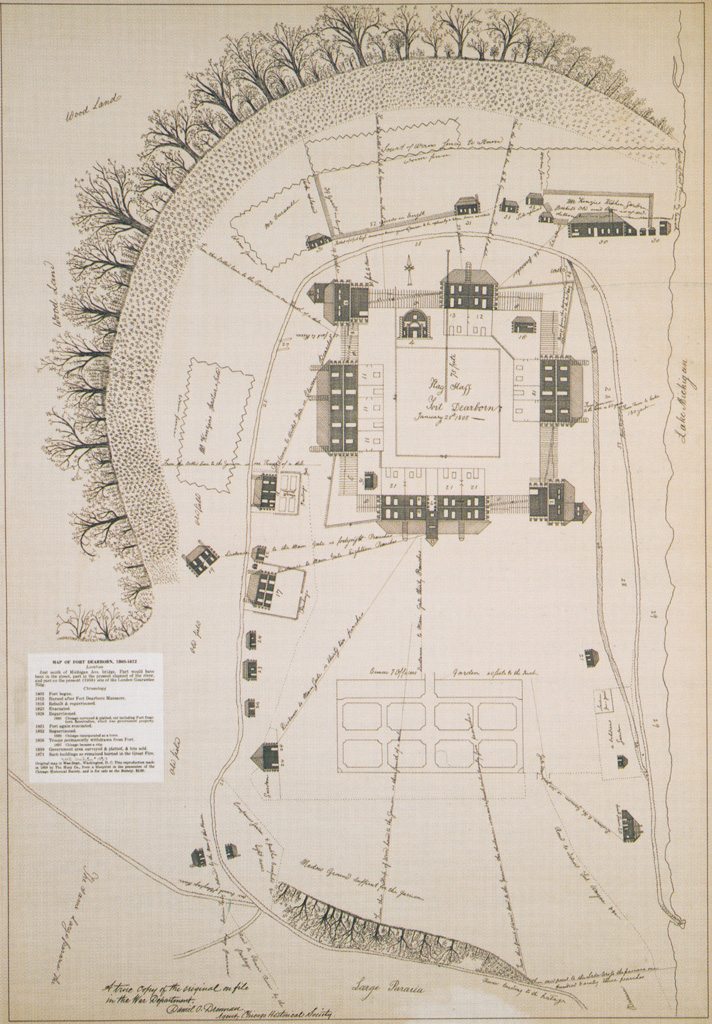

The rector was mistaken in some of the details; in particular, Whistler’s grandfather John Whistler could not have been one of the first parishioners of St. Mary’s, as he had died in 1829. But the basic premise was correct: the artist Whistler had longstanding familial connections to Chicago and his grandfather was in fact crucial to the establishment of the city. While a captain in the US Army, John Whistler built the original Fort Dearborn in 1803 on the Chicago River at what is now the intersection of Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive—the core of the future city (fig. 2). At the time of Captain Whistler’s arrival, the region was home to Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe peoples, along with British- and French-born traders such as John Kinzie. Settlement of the fort was key to US goals of expanding the nation through military conquests and treaties, which violated Native American nations’ sovereignty and decimated their populations. During the War of 1812, US troops evacuated Fort Dearborn and began to withdraw from the area. Angered by broken promises made by the retreating commander, Captain Nathan Heald, Potawatomi warriors defeated the soldiers and burned down the fort.

John Whistler’s command of the fort had ended two years earlier, when he was moved by the army to another posting and Heald took control. During his tenure at Fort Dearborn between 1803 and 1810, over a dozen Whistler family members lived on site, including the artist’s father, George Washington Whistler, who had been born in 1800 and was thus a young boy at the time. John’s son William Whistler (James McNeill Whistler’s uncle) served under his father during the construction of Fort Dearborn and, from 1832 to 1833, was commandant of the second Fort Dearborn, reconstructed on the same site in 1816. Holding the rank of major in the US Army in 1833, he was indeed the “Maj. Whistler” who joined the petition to establish St. Mary’s. He had six children, several of whom maintained ties to Chicago and the parish during the city’s formative years. For example, his son John Harrison Whistler, one of the first Anglo children born in Chicago, later baptized his own children at St. Mary’s. Major Whistler’s daughter Gwenthlean Harriet Whistler married John Kinzie’s son Robert Allen Kinzie in 1834, and their first daughter was likewise baptized at St. Mary’s.

Their cousin James McNeill Whistler never set foot in the city of Chicago. But the rector’s wishful description of Whistler as a “Chicago boy” sets the stage for investigating the foundational role that Chicago’s patrons, exhibitions, and institutions played in the development of Whistler’s American market. Indeed, the rise of the modern city of Chicago is firmly intertwined with Whistler’s career, as local art critics and collectors embraced him as someone whose art and personality would elevate the city’s stature. In turn, Whistler was keenly aware of his family’s importance in the history of the city, and at key moments sought to utilize those links to further his own ambitions. It has long been thought that the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition introduced Whistler’s art to Chicago, along with French Impressionism more broadly. But his paintings, drawings, prints, and personality had a notable public presence in the city prior to the fair, a fact that has been almost entirely overlooked in the Whistler literature.

This essay explores the early history of Whistler in Chicago, looking in particular at the years before the 1893 Exposition. Chicago loved “Whistler’s audacity”—his fiery personality went over well in the rough-and-tumble city—while his poetic sensitivity to nature appealed to those seeking refinement and cultural worldliness. It is this duality, perhaps, that made Whistler so popular in the city, for he represented an elusive and desirable combination: on the one hand, he was a brash American with local ties, while on the other, he had an international reputation and ties to the most progressive art movements of the period.

———— ❖ ————

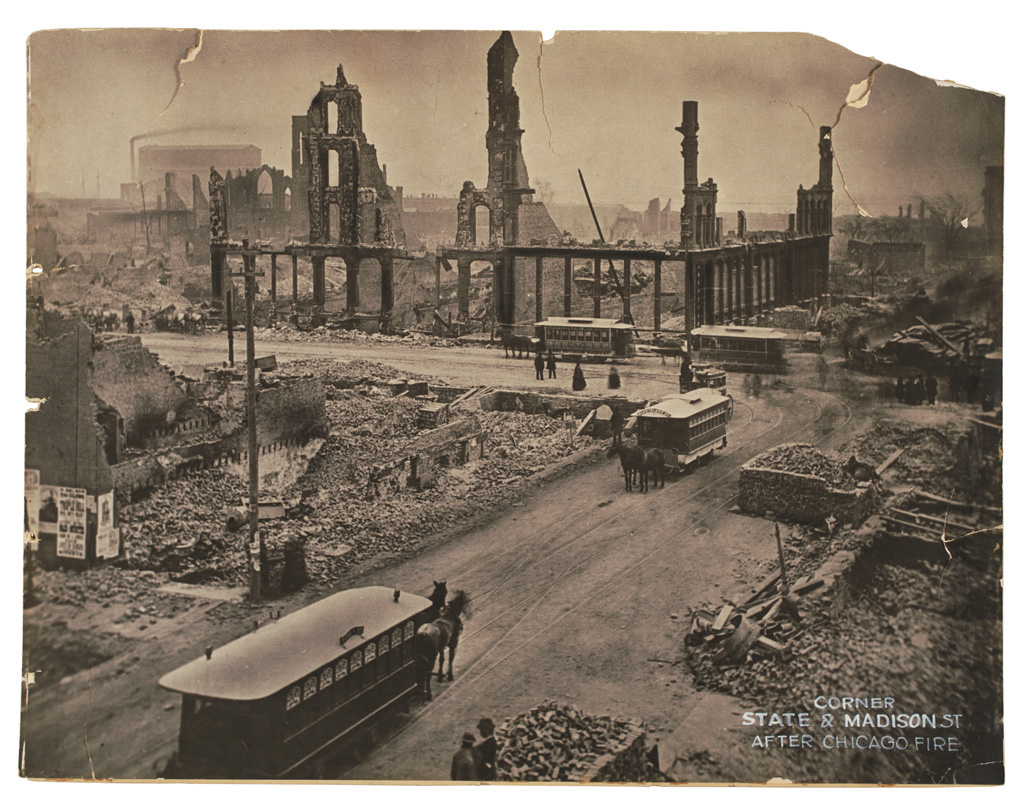

Whistler’s increasing international prominence as an artist in the 1870s and beyond paralleled the rise of Chicago, phoenixlike, from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871. Formally incorporated in 1837, just a few years after Major William Whistler held his post at Fort Dearborn, Chicago established itself as the center of the nation’s network of railroads by the 1850s, enabling goods and people to move throughout the country. But in October 1871, fire swept through the business district of the city, destroying an estimated 17,000 buildings across an area measuring nearly five square miles (see fig. 3). Three hundred people lost their lives, and some 100,000 others—nearly one third of the population—were left homeless. Chicago had been dealt a catastrophic blow. But it was a setback that city leaders vowed to overcome. The ensuing boom in construction and population transformed the frontier city into a major hub of commerce, transportation, and industry. Between 1880 and 1890 Chicago doubled in size, surpassing Philadelphia in the 1890 census as the second most populous city of the United States. Its only American rival was New York, and Chicago acquired the moniker the “second city” as a result. As the city flourished, so did the fortunes of businessmen such as the meat baron Philip Armour, the retailer Potter Palmer, and many others who became important civic advocates in Chicago’s Gilded Age.

The arts played a crucial role in the development of the city from its founding, as local businessmen and cultural figures sought to promote Chicago as a cosmopolitan center worthy of comparison to New York or European capitals. Even before the Great Fire, the city’s support of artistic institutions was notable. The Chicago Academy of Design was founded in 1866, and two fine-arts periodicals, Art Journal and Art Review (1867–70; 1870–71), were published locally. The devastation of the fire only spurred further investment in the arts in the 1870s and 1880s. The goal of Chicago’s philanthropic community was to promote the city as a cultural and business hub; as one commentator noted, “a development of artistic knowledge and taste as will ere long give to this great metropolis the same prominence as an art centre that she has reached in matters purely commercial.” The community believed it could accomplish this objective by bringing art to the city—to ensure that “Chicago people need not go away from home in order to buy good pictures . . . good pictures can be brought here and sold at good prices.” Although the transactional language of this particular commentary foregrounds the economic benefits of being a significant art center, the city’s forays into the art world were also intended to counter Chicago’s reputation as a city of nouveau riche meatpackers and railroad magnates—an opinion certainly held by tastemakers on the East Coast.

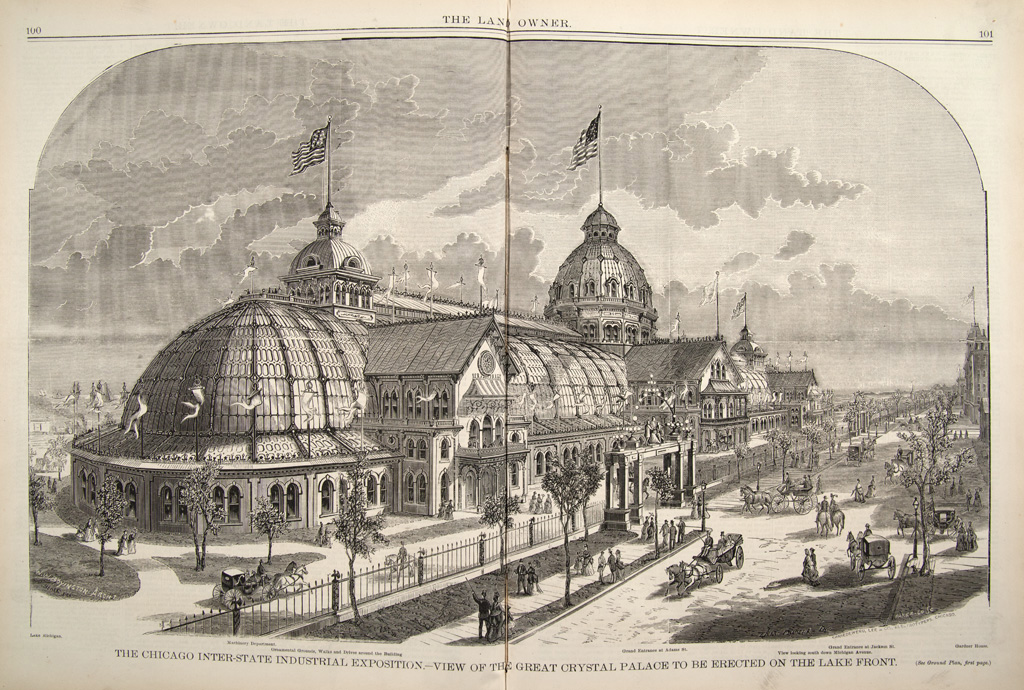

The city’s first major commercial and artistic endeavor was the Chicago Interstate Industrial Exposition, launched in 1873. This annual six-week fair, located in the heart of the newly rebuilt city at Michigan Avenue and Adams Street, began as a means of showcasing Chicago’s recovery just two years after the Great Fire (fig. 4). The powerful businessman Potter Palmer proposed developing the fair, undoubtedly aware of how his hotel and retail businesses would thrive as a result. The vast majority of the displays were industrial in nature and focused on manufacturing and trade. Significantly, however, the Interstate Industrial Exposition also included an art gallery that was intended to compete with other national exhibitions and enable prominent East Coast artists to exhibit and sell their work in the city. Within a decade, the Exposition Art Gallery was regarded as one of the top venues in the country—a leader in progressive art exhibitions. This became its international reputation as well; in 1885, for example, the London press wrote that the Interstate Exposition gave “a truer and more comprehensive idea of the best American art of the day than any other annual exhibition in America. . . . American art can best be seen and studied in Chicago [where] it is best appreciated.”

The venue soon became so popular with expatriate American artists living in Europe that it was described as “the American Salon.” This was largely thanks to the work of one woman: Sara Tyson Hallowell, who in 1879 was appointed the Assistant Secretary of the Exposition Art Gallery (fig. 5). Hallowell was instrumental in transforming the annual exhibitions into major showcases for a broad cross section of American art, including the work of more cosmopolitan painters living or working abroad, such as Whistler. Works by Whistler were exhibited in the 1882 and 1889 exhibitions, as shall be discussed shortly. However, even when his art was not on view, his aesthetic influence was still manifest in the paintings of other artists, among them William Merritt Chase and John Henry Twachtman. The exposition ended its run and the building was demolished in 1890, in part because the city was ramping up its plans for the World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1893 the site became the permanent home of the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 6).

Although the Interstate Industrial Exposition appreciably bolstered Chicago’s civic and cultural standing immediately after the Great Fire, the Art Institute was the city’s most substantial and lasting artistic undertaking, one that would help solidify Whistler’s presence in Chicago through both temporary exhibitions and the permanent collection. Founded in 1879 as the Chicago Academy of the Fine Arts, the museum was renamed in 1882 and held its first exhibitions in 1883. In 1888 it launched an annual exhibition series on American art that was expressly intended to rival major New York presentations; Whistler debuted in the second annual, held the following year. A comprehensive display of his etchings and lithographs in 1900 inaugurated what has become a sustained solo exhibition program focused on the artist: since then the museum has organized over twenty Whistler shows and featured his works extensively in many other major exhibitions, such as the Century of Progress International Exposition of 1933–34.

The Art Institute’s high regard for Whistler is also evident in the extensive collection of nearly fifty paintings, drawings, watercolors, and pastels by Whistler that are the subject of this catalogue—many of which first came to the city in the decades bracketing 1900. That year the museum purchased Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Southampton Water (cat. 16), the first of the artist’s Nocturnes to enter any museum collection. Another notable early acquisition is The Artist in His Studio (cat. 8), acquired in 1912 by the Friends of American Art, a patron group formed in 1910 to purchase significant historic and contemporary paintings for the museum. Other works were purchased by Chicagoans such as Arthur Jerome Eddy, John Lynch, and Bertha Honoré Palmer and later entered the museum’s permanent collection. Most of these patrons began acquiring Whistler’s paintings and drawings works in the 1890s—Lynch, for example, purchased Violet and Silver—The Deep Sea (cat. 34) in 1894, although it did not enter the Art Institute’s collection until 1955. Between the 1880s and the 1920s, early Chicago patrons also amassed significant holdings of his prints, which they likewise often gave to the museum. For instance, businessman Bryan Lathrop acquired an extensive and well-rounded collection prior to his death in 1916; 230 prints were bequeathed to the museum in 1917, followed by another 140 in 1934. Other early print collectors included Charles Deering, whose family would donate 150 works in 1927; Walter Brewster, who gave his extensive Whistleriana collection in 1933; and Clarence Buckingham, whose collection of 100 Whistlers arrived in 1938. Now, with the museum’s holdings numbering approximately 600 etchings and drypoints, 430 lithographs and lithotints, and 27 cancelled etching plates, the collection is a testament to Whistler’s extensive appeal in Chicago in the years after the Great Fire.

———— ❖ ————

Whistler’s rise to fame in Chicago was initially propelled by journalistic interest. He made his local newspaper debut in April 1876, when the Chicago Tribune featured a lengthy piece on the artist. Penned by a special correspondent then in London, the article introduced Whistler as “the most distinguished of our American artists.” It outlined the major tenets of Whistler’s art-for-art’s-sake aesthetic, from his theories on beauty to his use of musical titles, calling out his “perception of the harmonies and subtleties of color such as few painters have been endowed with.” Whistler’s etchings were also lauded briefly: “It is said that no such etchings have been produced since Rembrandt.” The author concluded that he “is a true poet, and the soul of poetry is in his paintings.” With this glowing introduction, the pump had been primed; Chicagoans had been given the tools with which to understand and appreciate the subtle beauty and delicacy of his paintings. Moreover, by positioning Whistler as the foremost American artist working abroad, the article also gave him international validation. Over the next few years, the Tribune eagerly reported on Whistler, from further discussions of his aesthetics to descriptions of his breakfasts and his dining room. The artist’s libel lawsuit against the English critic John Ruskin was followed at particular length, with the Chicago press weighing in on the merits of Whistler’s case. The commentary cast Whistler as pugnacious yet admirable: one author wrote, “If Mr. Whistler had put a nocturne in black and blue over Mr. Ruskin’s eye he would have treated him no worse than he deserved.” Such notices projected an image of Whistler as charmingly bold and brash.

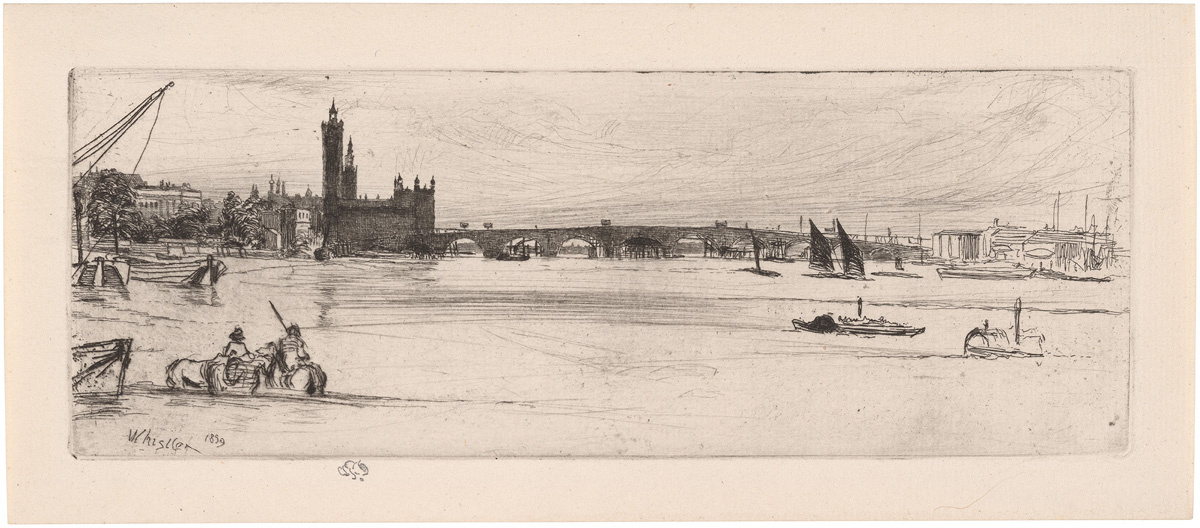

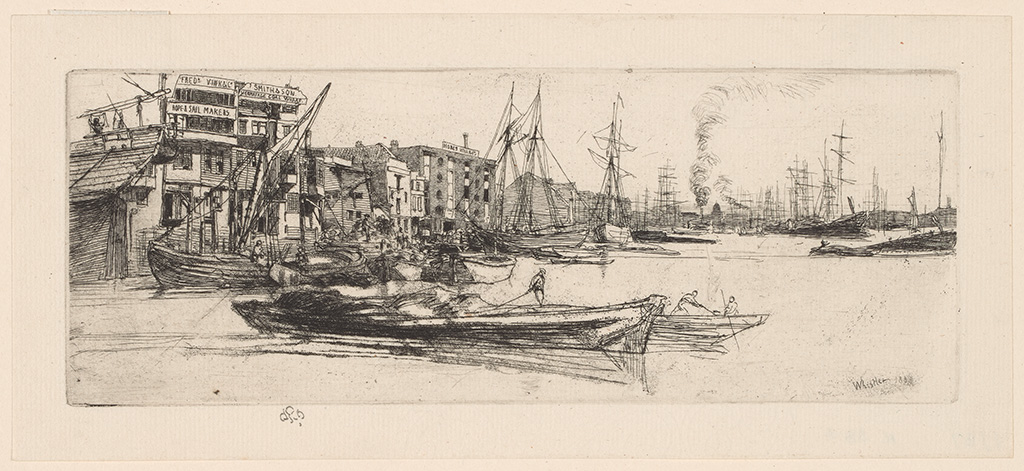

However, despite his attractiveness to Chicagoans, when the first works by Whistler were shown publicly in the city, at the Interstate Industrial Exposition of 1882, they went unremarked. The Art Gallery displayed a large group of prints owned by collector James Claghorn of Philadelphia, including five etchings by Whistler: two from the 1859 “Thames Set,” Old Westminster Bridge and Thames Warehouses (for similar examples see fig. 7, [L 42]; and fig. 8 [L 41]), and three more recent prints that the catalogue described only as “Scenes of Venice.” As just five etchings among over three hundred works on paper in the show, with an additional four hundred paintings rounding out the exhibition, Whistler’s small etchings certainly did not have much visibility; indeed, critics complained about the excessive size and tight hanging of the show. Despite this lack of journalistic notice for Whistler specifically, the 1882 exhibition marked a well-received moment of transition toward increased internationalism at the Exposition, with a significant number of entries by Paris-based American artists and a notable appreciation for cosmopolitan stylistic choices.

Chicagoans had their first large-scale introduction to Whistler’s groundbreaking art and exhibition practices in 1885 at W. Scott Thurber’s commercial art gallery on Wabash Avenue. The display at Thurber’s was a re-creation of the artist-designed exhibition Whistler had dubbed Arrangement in White and Yellow. It had made its first appearance at London’s Fine Art Society in February 1883, and consisted largely of etchings made during Whistler’s sojourn in Venice between 1879 and 1880. After closing in London, Arrangement in White and Yellow traveled to New York, Baltimore, Boston, and Detroit before arriving in Chicago at Thurber’s gallery in April 1885. At the time, only a few fine-art galleries existed in Chicago. Thurber had opened his eponymous gallery in 1880, and he sought to position it as a space for art connoisseurs of refinement and taste. As was noted in the press in 1882, Thurber “intends to exhibit a superior class of pictures,” such that “all lovers of the beautiful visit it.” He accordingly worked with H. Wunderlich & Company in New York to bring the Whistler show to Chicago.

As numerous scholars have discussed, Arrangement in White and Yellow was the sensation of the London season in 1883 for its daring approach to exhibition design. The walls were covered with white felt, banded at top and bottom by bright-yellow wood molding. The etchings were widely spaced and appeared in custom white frames decorated by two stripes of reddish-brown paint. The interior space, glowing with yellow and white, was intended to showcase Whistler’s recent Venetian etchings to their best advantage, creating a unified display that exemplified Whistler’s interest in harmonious color on a large scale. It also revealed Whistler’s flair for showmanship; not only did he encourage guests to wear harmonizing outfits, he outfitted a young gallery attendant in a uniform of yellow and white that critics derisively likened to a poached egg.

Although Whistler was not involved in the American tour of Arrangement in White and Yellow, the show was critical in promoting his art and theories on exhibition design in his country of origin. In Chicago the exhibition drew attention from the Tribune primarily for its décor, which attempted to emulate the original display through an abundant use of white and yellow. Thurber’s gallery was described as “admirably adapted” for the exhibition, with “the same appointments with which the ‘White and Yellow Study’ was presented in London.” To help its readers visualize the space, the article described it at length: “The walls are draped with white billiard-cloth . . . the floor is covered with yellow Japanese matting, and the deep frieze is a sateen of the same color. On one wall, placed quite near the ceiling, is a long strip of yellow velvet. A few yellow chairs, and two or three lemon-colored stands, supporting each a piece of pottery of the same hue, are arranged around the room. The light is admitted through a canopy of cheese-cloth which covers the whole area. From the doorways hang long draperies of yellow velvet.” No mention is made of a gallery attendant outfitted in yellow and white, which suggests that this aspect did not figure in the Chicago iteration of the show.

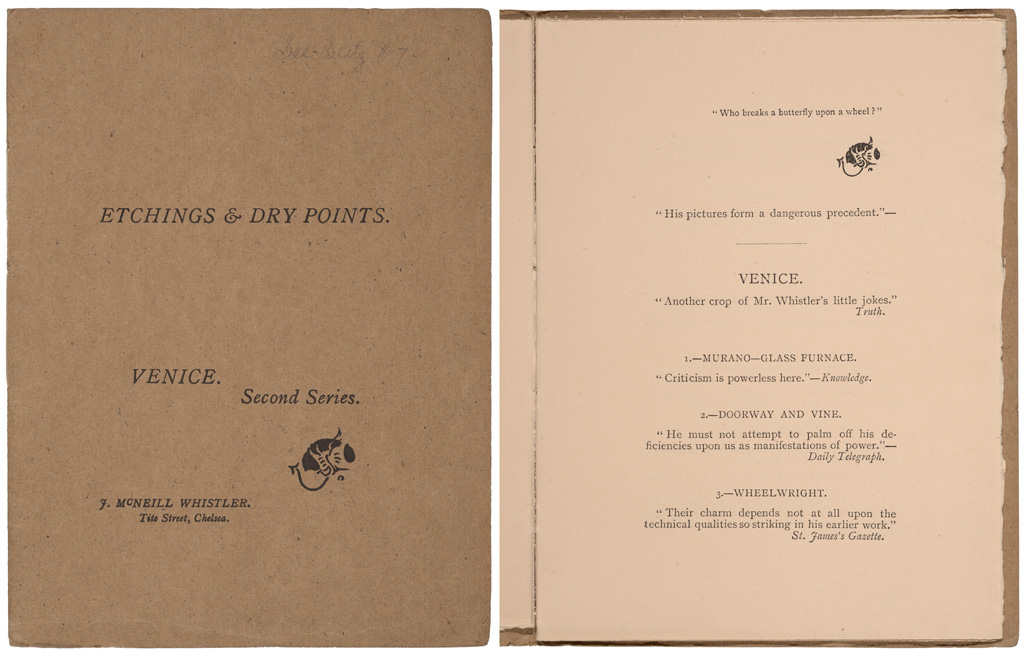

The catalogue, titled Etchings & Drypoints: Venice, Second Series, also received significant consideration in the Tribune (see fig. 9). Subtitling it Mr. Whistler and His Critics, Whistler had compiled, manipulated, and misquoted critical responses to his art, which he further annotated with his own scathing asides, to undermine the legitimacy of his critics. While English critics saw the catalogue as evidence of poor taste, or Whistler’s “American gall,” the Tribune deemed it a “literary curiosity.” The Chicago reviewer framed Whistler’s use of quoted commentary as evidence of the artist’s eccentricity carried to an extreme degree, yet bemusedly noted the “zeal with which all favorable criticism has been ignored.” This statement suggests that the Tribune writer had sufficient awareness of the artist’s reputation to know that Whistler had overlooked positive commentary in his belligerent challenge to London critics.

Despite the appreciation for the decoration, the art itself—“small etchings with expansive white mats and narrow yellow frames,” as the Tribune writer put it—was not well received. The author critiqued the etchings’ “insufficiency of detail and incompleteness of finish,” and found them particularly lacking in contrast to earlier works: “That he is possessed of poetic feeling, artistic appreciation, and the ability to execute with skill and force the works of former years offer abundant proof.” The fact that the writer’s language parallels that of British critics invites speculation as to the source of his knowledge. The author does not indicate what types of works he preferred, but given that this was the first noteworthy show of Whistler works in Chicago, any firsthand experience must have come from seeing the artist’s etchings elsewhere. The “Thames Set” had circulated robustly, so the author’s response to the Venetian etchings could well have been negative by virtue of their contrast to Whistler’s earlier, more finished works in that medium. It is also possible that the author was taking his cues directly from earlier reviews of the Venetian prints when they were seen in London, New York, and other American cities, for such copy was picked up by many papers and circulated widely. But the novelty of the exhibition, combined with Whistler’s reputation, was sufficient to warrant a lengthy and detailed article, attesting to an elevated sense of Chicago’s affinity for the artist.

The cool reception of Arrangement in White and Yellow notwithstanding, the media’s fascination with Whistler only increased over the next several years, spurred by his daring approach to gallery installation and audacious rhetoric. Subsequent articles highlighted his eccentricities and consistently referenced the unusual nature of his exhibition design. Indeed, the “American gall” that so irked the English may have offered Chicagoans a satisfying parallel to how they saw themselves. The city’s formerly frontier status and rebirth from the fire had created a citizenry that prided itself on its upstart, plucky ways, and Whistler’s cheekiness made him a ready match for Chicago’s aspirations.

———— ❖ ————

In 1889, as his star rose in Europe and the United States, Whistler’s works became increasingly visible in the city. In June of that year, the Art Institute included Lady in Gray (fig. 10, [M 933]) in the Second Annual Exhibition of American Oil Paintings. Critics used the opportunity to link his fiery personality to the aesthetics of his art. The Tribune admired the sitter’s pose, likening it to Whistler himself: “She is there to be impertinent, and no one can be as delightfully impertinent as Whistler—always intrusive and always welcome. . . . We feel like embracing him—and getting pricked for our pains—for his intrepid arrogance.” Once again, the perception of Whistler’s audacity contributed to the reception of his art, and although Lady in Gray is a watercolor small in scale, it nonetheless compared favorably in power and attention-grabbing charisma to large oil portraits. The Tribune writer further reported, “the little picture has been snapped up of course, and thus our supercilious English girl is destined to frown upon Chicago during the rest of her immortal youth.” Yet this prediction did not bear out; although the Chicago newspaper advertiser Charles K. Miller purchased the watercolor for $250, it remained in the city only until 1906, when Miller sold it to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

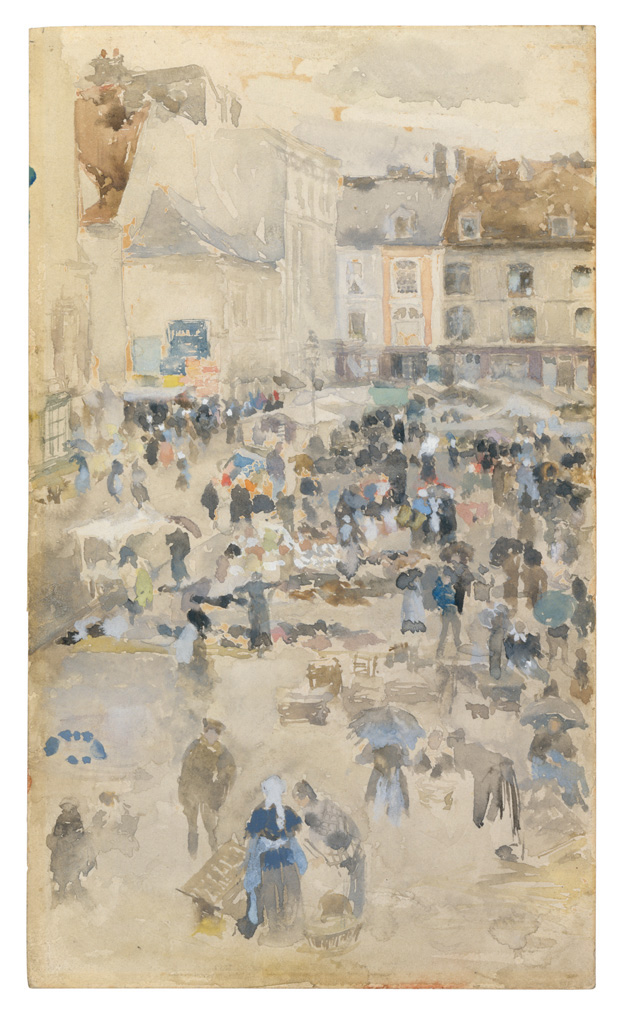

The Art Gallery of the Interstate Industrial Exposition also prominently displayed Whistler’s works in September 1889: five watercolors and two oil paintings comprising a wide range of subjects, among them Arrangement in Black and Gold; Note in Grey and Green—Holland; and Variations in Violet and Grey—Market Place, Dieppe (fig. 11, [M 932]; fig. 12, [M 963]; and fig. 13, [M 1024]). The works had all been exhibited in Whistler’s larger solo show “Notes”—“Harmonies”—“Nocturnes,” which was held in London in 1886 at Dowdeswell’s Gallery, and was later partially reprised in New York in March 1889 at H. Wunderlich & Company. The Tribune critic had seen the show at Wunderlich’s gallery and urged Chicagoans to bring some of the works to the city for exhibition. Sara Tyson Hallowell then arranged for their display at the Interstate Industrial Exposition. Whistler was informed by Wunderlich’s that in Chicago, “flattering representation [has] been made as to the interest the pictures would excite, with excellent prospects of sales,” and it seems possible that Hallowell was responsible for these assurances. However, none of the seven works were sold to Chicago patrons.

The critical reception was, however, quite positive. For example, the display inspired the astute critic for the Tribune to pen a lengthy article about Whistler that drew an explicit link between Whistler’s personality and the depth and quality of his work across many media: “The audacious but fascinating personality of James McNeill Whistler is manifested as convincingly through one of his tiny ‘Notes’ in color, through the merest knowing scratch of his etching-needle, even through the enigmatical butterfly which he uses instead of a signature, as through his largest and most elaborate works.” He then glowingly lauded the poetic qualities of the small paintings: “No analytical treatise could unfold so faithfully the venturesome recklessness of the man, the delicacy of his sense of humor, the sureness of his sense of harmony, as do the seven little color essays now at the exposition.” With artistry and personality firmly linked, Whistler’s art was seen as the ultimate means of separating the cognoscenti from the philistines—a theme that would have resonated tremendously with a Chicago audience seeking to prove their sophistication and embrace of cosmopolitan behaviors. The author further expounded on this divide, noting, “He who likes them feels a quickening of his sense to emotions of delight and laughter; he receives a pure, succinct, impression of force and knowledge exerted to achieve subtle and delicate effects of beauty. He who does not like them misses this enlivening sensation, and . . . all the reason in the world will not give it to him.” Appreciation of Whistler was thus positioned as the aesthetic validation Chicago needed to enhance its cultural cachet.

If the 1880s saw the rise of Whistler’s reputation in Chicago, the 1890s inaugurated a mutually beneficial period of exchange between the artist and the city. Local collectors, largely members of Chicago’s business community, began acquiring works by Whistler in greater numbers. In turn, Whistler himself became keenly aware of the buying power in Chicago and began actively courting the city’s cultural elite in pursuit of sales. By way of example is the dry-goods merchandiser Levi Ziegler Leiter, who with Marshall Field and Potter Palmer helped found Field, Palmer, Leiter and Company (which later became the iconic Marshall Field’s department store). Among other civic responsibilities, Leiter served as president of the Art Institute from 1880 to 1882 (when it was known as the Chicago Academy of the Fine Arts), thus helping build the city’s major cultural institution. Leiter came to Whistler’s attention in 1891, presumably during a trip to Europe where the two men met. Whistler tried to interest Leiter in two Nocturnes and instructed the dealer David Croal Thomson to show them to the visiting American, with the advice that since Leiter was an “archimillionaire” from Chicago, Thomson would not have “the vexation of haggling over the proper prices.” Leiter did not opt for the Nocturnes, but he did purchase two other works by Whistler: the etching Zaandam and the watercolor Rosy Silver—The Pink Porch (fig. 14).

A crucial figure for Whistler in Chicago was Bertha Honoré Palmer, the wife of businessman Potter Palmer (fig. 15). After parting with Leiter and Field, Potter Palmer opened the Palmer House hotel in September 1871, only to have the building burn down thirteen days later in the Great Fire. He rebuilt the edifice on a grander scale and became one of the city’s greatest philanthropists, with his wife becoming one of Chicago’s most acclaimed art patrons. She had begun collecting works by Whistler in earnest by May 1892, when on a trip to France she purchased Mother and Child (fig. 16) for 3,000 francs—a sum that Whistler described as a “pretty big price for Paris.” As he had with Leiter, Whistler urged Thomson to show her specific works available for purchase: “She is the most important lady in the Chicago Exhibition matters—You must find her and show her ‘La Dame au brodequin jaune’—Also Falling Rocket” (fig. 17, [YMSM 242]; and fig. 18, [YMSM 170]). Palmer did not, however, purchase either.

Whistler’s letter demonstrates his awareness that Palmer was closely involved in the planning of the World’s Columbian Exposition; she was the president of the fair’s Board of Lady Managers, a prestigious and influential position. Whistler in fact sent her his book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies with the note, “You will find, as I promised you should in this book, the Presidential experiences of a short, brilliant & despotic caree[r]. I trust that the inspiriting account of the same will only urge you on to splendid tyranny and further triumphs in your own irresistible & enduring reign!” Courting her served two purposes for Whistler: he could help ensure a good representation of his art at the Exposition, and he could continue to encourage her to collect his works. Indeed, Palmer next acquired Grey and Silver: Old Battersea Reach, an early painting from 1863 (cat. 7), for 450 guineas. She purchased Trouville (Grey and Green, the Silver Sea) (cat. 9) from the critic Théodore Duret several years later; both paintings would come to the Art Institute in 1922.

———— ❖ ————

The World’s Columbian Exposition was a crowning moment for Chicago, with its civic ambitions playing out on an international stage (fig. 19). This was also the moment when Whistler was most actively engaged with the city and its artistic culture, looking to parlay Chicago’s already developed goodwill into further career successes. Whistler’s acknowledgment of Palmer’s central role in the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and his attempts to woo her comprised only one way that the artist positioned himself relative to the fair.

His interest in Chicago and the exposition related directly to his growing awareness of his family’s personal history in the city. In March 1892, Whistler corresponded with his relative Francis Bloodgood of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The cousins had met in Paris in 1891 or early 1892, and Bloodgood promised Whistler he would help research the artist’s Chicago heritage. Bloodgood sent him “facts connecting the Whistlers with the early history of Chicago,” including obituaries, biographies, newspaper articles, and other historical ephemera, particularly relating to the construction of Fort Dearborn by Whistler’s grandfather, which was to be honored at the Columbian Exposition. Bloodgood also noted that contemporary newspapers “have suggested the propriety of his descendant, the artist, contributing something to mark an event recognized as the foundation of Chicago.”

Whistler became intrigued with the idea that he might be offered a commission for a commemorative painting of the fair. Concurrent with his correspondence with Bloodgood, his wife Beatrix asked his patron Charles Lang Freer of Detroit to investigate: “What is this that we see in a Glasgow paper, that there has been some talk in Chicago of commissioning Mr Whistler to paint a picture in commemoration of the Chicago Exhibition as it was his Grandfather who selected the site of the city.” Freer inquired about the possibility among fair organizers in Chicago and New York, but no such commission came to pass. The organizers of World’s Columbian Exposition did, however, invite Whistler to visit Chicago to lecture on Impressionism at the World’s Congress Auxiliary; he declined.

Whistler was initially invited to exhibit with the British section of fine arts, as he had at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889. English landscape painter John W. Beck made overtures to Whistler in July 1892, but Whistler was annoyed by past slights by Beck and other members of the English selection committee and rejected their invitation. Representatives from the American section also reached out over the summer. However, believing he was committed to showing with the British, they did not formally invite him until October 1892, when Halsey C. Ives, chief of the fair’s Fine Arts Department, appealed to him directly: “We are exceedingly anxious to have a group of your works placed in our section. . . . I shall be pleased to do everything in my power to place them in a manner in keeping with the dignity, knowledge and artistic feeling which they possess.” Whistler was flattered, describing it to Edward Guthrie Kennedy, the New York representative for Wunderlich, as a “most charming and excellent letter,” adding, “You will see from the warmth of his manner that we will be well received and that it would be folly indeed to miss having a fine show in the place.” Thus persuaded to join the American section, Whistler accepted Ives’s invitation and conveyed his enthusiasm: “I am greatly interested in the Chicago Exposition, and most anxious to be well represented there.”

Over the summer of 1892 Whistler strategized about which pictures to send to the fair, writing to Kennedy that “really we are most anxious to have a good show over there.”Although it has been suggested that Whistler invested little effort in preparing for the Exposition, his correspondence repeatedly attests to his eagerness to participate. While he asked Kennedy to represent him in this effort and manage many of the logistics, Whistler remained attentive and demanding throughout the process. He instructed Kennedy to write to a number of major collectors in Britain and America, including Charles Lang Freer, Bertha Palmer, and Isabella Stewart Gardner of Boston. He also corresponded with several patrons himself in the hopes of persuading them to lend specific works. This included Samuel Untermyer, who had recently purchased Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (fig. 18): “If you will consent to do this I shall be greatly gratified, as the work has achieved a certain historical reputation and I should much regret its absence.” Untermyer was willing to lend, yet arrangements to ship The Falling Rocket were not made in a timely fashion, and it was ultimately not shown in Chicago.

Whistler was more successful in obtaining the loan of The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (fig. 20; [YMSM 50]), which had just been sold to the Glasgow dealer Alexander Reid. Whistler had an ulterior motive in encouraging Reid to exhibit this painting in Chicago, along with two others owned by the dealer: he wanted Bertha Palmer to acquire it. As preparations for the exposition got underway in 1892, Whistler mounted a campaign urging Reid to offer it to her. In this vein, Beatrix Whistler wrote to Reid, “Mr Whistler says you must ask £2000 guineas for her, and why dont you try the Potter Palmers, the rich Chicago people.” Whistler himself later enticed Reid further: “I hope you will finally send her over to Chicago—There is where all the thousands will come to you for these pictures of mine—and I do want them to be got out of England!” Chicago’s fortunes, along with the opportunity of the Columbian Exposition, gave Whistler the means to spite the English art establishment and promote his art to receptive patrons.

In the end, Whistler showed six paintings and fifty prints at the Exposition—one of the largest displays by a single artist—and won awards in both categories. In addition to The Princess from the Land of Porcelain, Reid lent two other large paintings: Arrangement in Black and Brown: The Fur Jacket and Arrangement in Black (The Lady in the Yellow Buskin) (fig. 21; [YMSM 181]; and fig. 17). A. J. Cassatt, the brother of artist Mary Cassatt, lent The Chelsea Girl (fig. 22; [YMSM 314]). The other two loans were both landscapes: Blue and Silver: Trouville, owned by American expatriate artist Sir James Jebusa Shannon, and Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Valparaiso Bay, owned by Sir John Charles Day, a London judge (fig. 23, [YMSM 66]; and fig. 24, [YMSM 76]). Howard Mansfield, a major print collector in New York, organized the display of Whistler’s etchings. However, the installation of the American section did not proceed on schedule nor as anticipated by the organizers. Mansfield reported that when the show opened, only four of the six paintings were installed, and he had to intervene to get the prints positioned in a better location. In a letter now lost Kennedy as well must have hinted at some uneasiness about the installation, for Whistler responded: “it is very clear that you have glided gently over the difficulties of the situation as far as I am concerned . . . Then from What you say in a sort of apologetic way, it is evident that the hanging of the paintings themselves has been abominable.” This might or might not have been the case, especially given Whistler’s famous sensitivity to perceived slights. Photographs of the display show Whistler’s paintings hanging in prime locations at comfortable heights, not relegated to side rooms or positioned high above eye level (fig. 25).

After nearly two decades of primarily hearing about Whistler rather than seeing his art firsthand, Chicago critics were eager to examine his works more closely at the Exposition. George Inness and Winslow Homer garnered praise as the most “American” painters, but Whistler and his fellow expatriate John Singer Sargent received the most attention overall from the press, both local and national. Although a few East Coast magazines, among them Art Amateur, expressed reservations, Chicago reviews were generally favorable, despite some concern that fairgoers unfamiliar with his style would find the paintings mystifying. The Chicago Inter-Ocean sought to tutor its readers on how to understand and appreciate Whistler’s technique, instructing: “In looking at a Whistler it must be remembered that the artist never goes into detail. . . . When he has developed his idea he adds not one touch more lest the effect be destroyed, and the result is a most fascinating blue, from which something stands boldly out.” Most other Chicago critics reviewed his paintings in glowing terms, including a full-column article on Whistler in the Chicago Evening Journal that effusively detailed each painting. One notice of the Chelsea Girl (fig. 22), for example, cherished it as a “marvel of broadness and audacious treatment,” while another raved, “impertinence pure and simple is all the picture expresses,” having already made note of Whistler’s audacity as an artist. However, reviewers largely admired the subtlety of Whistler’s paintings, especially in comparison to the brilliant boldness evident in Sargent’s works. The Evening Journal article described Arrangement in Black (The Lady in the Yellow Buskin) (see fig. 17) as having a “certain elusive charm,” while praising the “mysterious space” of the background. The critic also rhapsodized about his personal response: “each time that I approach this painting I feel a repetition of that first thrill of pleasure in its spontaneity and in the indescribably beautiful color-harmony. . . . It will forever be a joy.” The language implicitly suggests the critic possessed a high level of sensitivity to which others should aspire, recalling earlier suggestions that only the sophisticated could enjoy Whistler’s art.

Whistler’s patron Freer also praised the selection of paintings in a letter to Whistler, remarking, “Your work of course, completely overshadowed everything in the Fine Arts Department, and gave pleasure and inspiration to many more people than you imagine.” One of those inspired by Whistler was the young Chicago lawyer Arthur Jerome Eddy. He greatly admired the six paintings on view at the Columbian Exposition and determined to visit Whistler in Paris to commission a portrait. Over the course of six weeks in the autumn of 1894, Eddy posed for Whistler, developing a close relationship with the artist as well as a deep understanding of his working methods. The resulting portrait, Arrangement in Flesh Color and Brown: Portrait of Arthur Jerome Eddy (cat. 35), is one of Whistler’s finest from this period. Anxious about Whistler’s known habit of retaining and reworking paintings endlessly and often to their detriment, Eddy doggedly pursued the portrait after his departure from Paris. In November 1894, he evidently commiserated with Chicagoan John Lynch, who was likewise waiting for Violet and Silver—The Deep Sea (cat. 34), purchased by Lynch the month before. Eddy wrote to Whistler about his concerns, “Within the last two or three days, we [Eddy and Lynch] have had some misgivings lest your critical eye should find some flaw in the pictures, and you should conclude to keep them by you.” Eddy’s efforts were successful, and the two paintings arrived together in Chicago by early December 1894. Eddy admired his portrait greatly, and even derived pleasure from the fact that some of his Chicago friends held conflicting opinions: “If everybody liked it on first sight, I should argue feel it is not a Whistler. The quality of a picture is inversely [proportionate] to the number of those who propose to admire it.”

Eddy quickly became one of the artist’s greatest champions in the city. He attempted to organize a solo exhibition of his works, connected the artist to other Chicago patrons, and sought to entice Whistler to Chicago: “Do not disappoint us—do not let anything interfere with the proposed journey. Our art institute is wild over the prospect of having your pictures and they will make the Exhibition the event of the year—of many years—and as for yourself, well no one believes for a moment you will come to America so here is a rare opportunity to again prove that people in general know nothing.” Eddy’s determination was fruitless in this instance, although, as noted earlier, the Art Institute has in fact repeatedly exhibited Whistler’s art throughout its history. Eddy’s most lasting contribution as Whistler’s advocate was as the author of Recollections and Impressions of James A. McNeill Whistler, which he published in 1903, the year of the artist’s death. Drawing on his time spent posing for Whistler in 1894, Eddy wrote the book as “a tribute to the great painter.” In addition to offering biographical details and personal anecdotes, his observations about Whistler’s painting techniques are astute (see cat. 35). His experience with Whistler inspired Eddy to learn more about modern art, and he soon was the authority on the subject in Chicago. His groundbreaking study, Cubism and Post-Impressionism (1914), was highly influential, and Eddy developed an extraordinary collection that ranged from Whistler and Winslow Homer to Vasily Kandinsky and Constantin Brancusi, much of it now at the Art Institute (see fig. 26).

In the two decades between the Great Fire of 1871 and the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, Chicagoans were thus increasingly aware of and ready to embrace Whistler’s art. After the Great Fire, as the city attempted to transform itself into a world-class metropolis rivaling New York despite its reputation as the home of hardheaded and uncultured businessmen, Whistler’s headstrong personality made him a local favorite even as his delicate approach to painting was seen as offering a necessary civilizing influence. His international reputation—as an American with European connections and aesthetics—only strengthened his cosmopolitan appeal as Chicago worked both nationally and internationally to transcend its “second city” status. Likewise, Whistler understood what Chicago could offer him. Although interest in Whistler ran high in cities across the United States—Detroit, for example, was home to Charles Freer, whose Whistler collection outpaced all others—Chicago’s broad base of institutions and wealthy collectors was significant. As a savvy self-promoter with a keen interest in attracting wealthy patrons, Whistler knew this was an ideal place to market himself through exhibitions such as the world’s fair, or to collectors such as Levi Leiter and Bertha Palmer. That he had historical familial connections to Chicago only made the city more attractive for the expatriate artist. Indeed, although not in fact “a Chicago boy,” Whistler once said to a visitor from Chicago (probably Eddy): “Chicago, dear me, what a wonderful place! I really ought to visit it some day—for, you know, my grandfather founded the city and my uncle was the last commander of Fort Dearborn!”