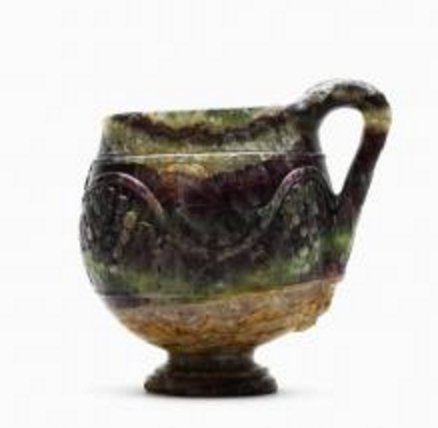

Description

Transparent blue, amethyst, and opaque white and yellow glass. Mosaic glass technique, cast or sagged, tooled, and polished. The vertical rim is rounded by grinding. The vessel wall bends down and in to form a shallow dish with convex sides and a slightly flattened bottom. The mosaic pattern is created from round sections and square segments of five canes: the first in an amethyst ground with a white spiral and a central blue rod; the second in a blue ground with a white spiral and a central amethyst rod; the third, in short, rectangular segments or strips of amethyst equally divided by two white lines; the fourth and fifth, roughly square segments of white and yellow. A cane of amethyst spirally wound with a white trail was applied at the rim. The interior pattern consists of roughly equal numbers of blue and amethyst spiral canes with some twenty-seven rectangular segments of amethyst and white stripes randomly placed about the interior along with some eighteen square segments of white and sixteen of yellow. While the spiral and striped canes can be seen on both the interior and exterior surfaces, the monochrome segments can only be seen on the interior. The interior was rotary ground, and the exterior was fire polished. The exterior shows mainly spirally wound canes of blue and amethyst, but there are several long, muddy amethyst sections and one area of green and yellow glass.

Technique

The mosaic glass technique is the same method used to produce complex designs such as those found in antique and modern paperweights (fig. 71.1). It is a technique of great antiquity: examples of mosaic glass vessels are known from both Near Eastern and Egyptian sites in the later second millennium B.C. They were contemporaneous with vessels that were manufactured by casting and by core forming. In the mosaic glass manufacturing process, glass was drawn out into rods or canes and strips of various colors and banded together to create patterns such as spirals or rosettes. This bundle was heated and marvered to make a bar, then pulled out like taffy to form a cane of diminishing size with the design preserved throughout its length. Complex designs such as the two inlays depicting theater masks (cat. 78 and cat. 79) would be created the same way but by repeating the process dozens of times to make up the various elements of the face and hair. These processes are discussed more extensively under Method in the technical report.

Canes were cut either crosswise in short sections or lengthwise into strips. A vessel could have been created in several ways; we cannot confirm what technique was used in antiquity. If a two-part mold was used, the sections and strips would have been arranged on the interior of an open mold and the top with its corresponding solid interior shape would have held the sections in place while both were slowly heated. As the sections of cane softened and compacted, the top edge would have become uneven; a long cane would have been applied to this uneven rim to fill in the irregularities. Both sides would have been ground and polished. Sagging or slumping may have also been used. In this method the sections of cane would have been heated on a flat surface and squeezed together to eliminate any space between them as they softened in the furnace. The contrasting long cane would be applied to the outer edge of the flat disk. The disk would have been placed over a former mold in the shape of the vessel. While the disk and mold were slowly heated, the disk would have been tooled and manipulated over the former mold to create the dish. Sagged vessels may have been polished on the interior where the glass touched the mold, but the exterior was often left unpolished, as it retained a fire polish from the furnace. These processes are discussed more extensively in the Technical Report.

Related Material in the Art Institute of Chicago’s Collection

The Art Institute of Chicago has in its ancient glass collection a number of important objects and fragments that relate to this dish. They represent a series of manufacturing techniques producing stunning, colorful forms that were variations of the mosaic glass technique. They illustrate the range of forms and patterns that were popular during this incredibly prolific period in late Hellenistic and Roman glassmaking.

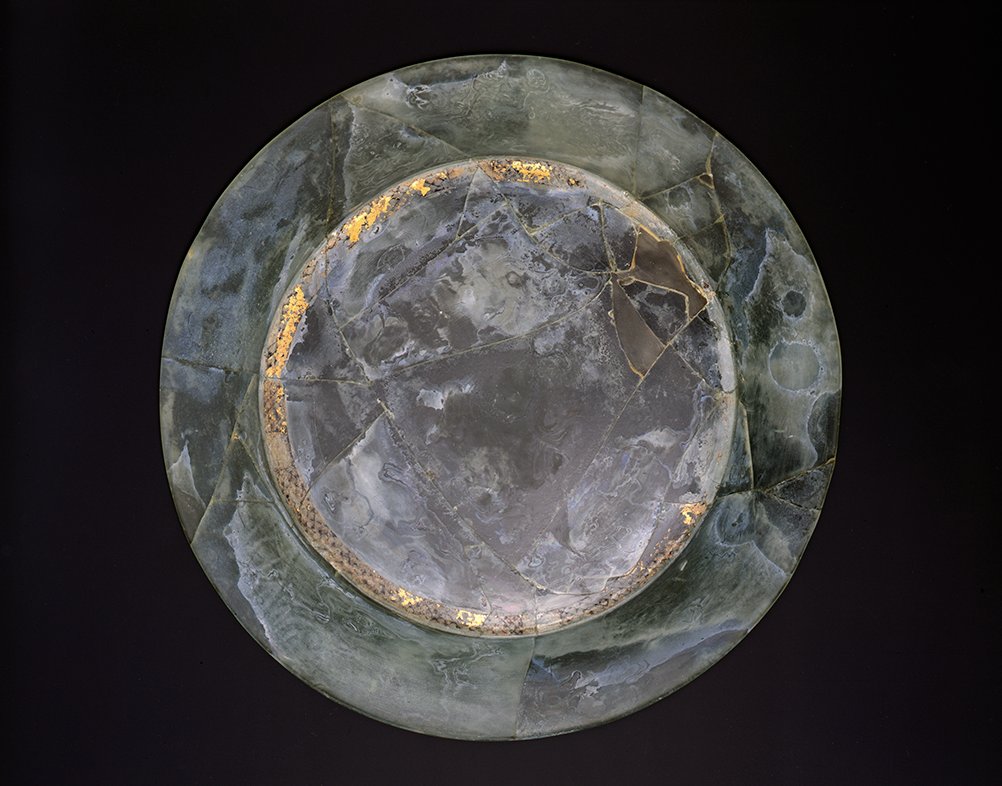

Band or ribbon glass manufacture, a variation of the mosaic glass technique, involved grouping together colored strips or flattened rods to be cased in colorless glass and manipulated into a series of forms. The Alabastron (Container for Scented Oil) (cat. 73) is a rare example of band glass that takes the variation in mosaic glass manufacture to unparalleled luxury. In addition to the undulating patterns so characteristic of these glasses, there were two colorless bands that have gold leaf trapped between them. When the surface was manipulated and shaped, the leaf shattered and stretched following the movement of the glass. The results are among the richest surfaces and color combinations found in ancient glass.

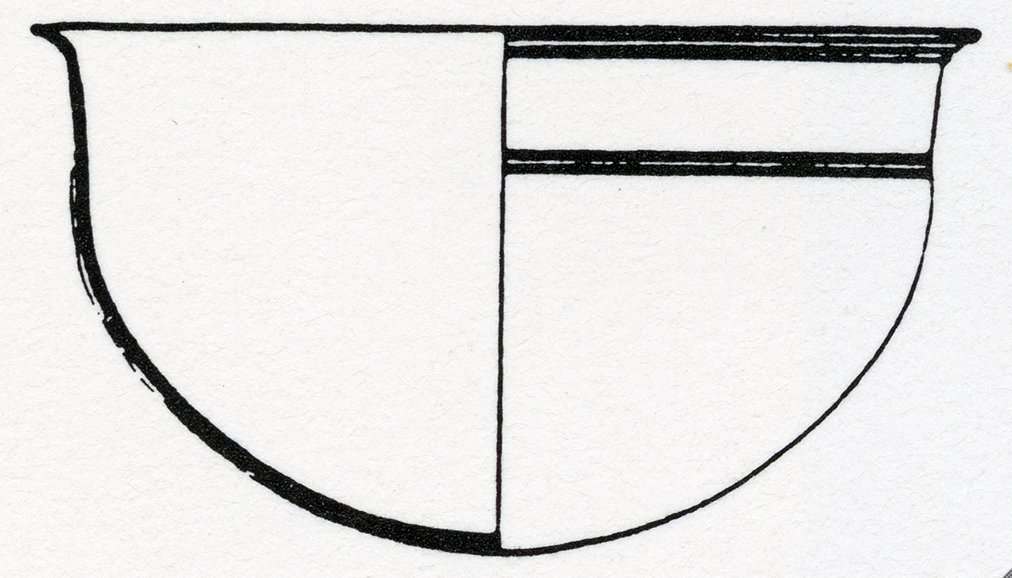

A second related object is a bowl (cat. 74) made by assembling colorless canes spirally wrapped with a white trail into a flat disk, then sagging the disk over a former mold in the furnace. Recalling delicate lace, the vessel has a completely different aesthetic from both the rich, carpet-like pattern of the amethyst dish and the jewel-like quality of the gold-band alabastron, yet all are made by a variation of the same technique.

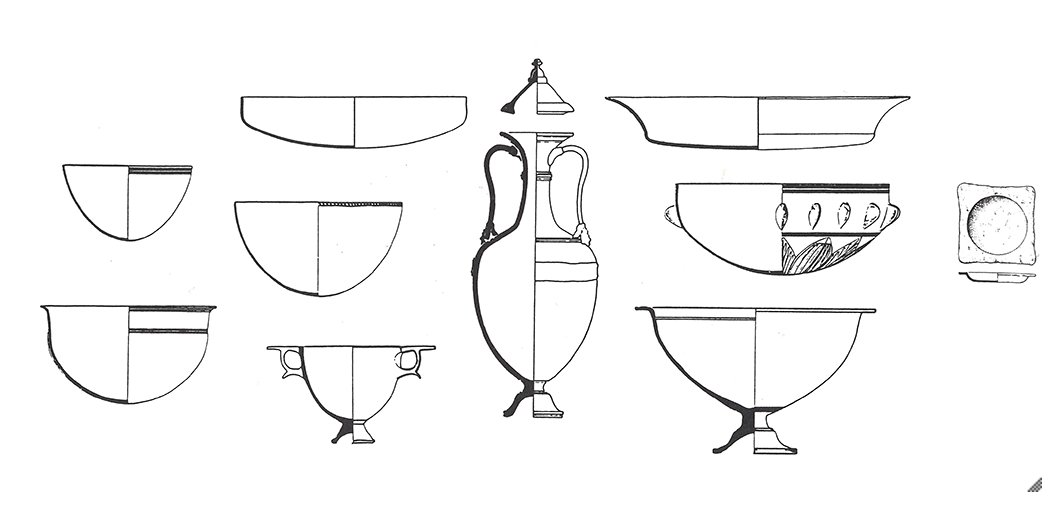

A small bowl (cat. 83) and a series of four related fragments of cups (cat. 84, cat. 85, cat. 86, and cat. 87) offer examples of the endless variety of patterns used to produce these vessels. The bowl replicates an extremely popular ceramic form that glassmakers fashioned by casting and lathe cutting in monochrome vessels as well as mosaic glass. The numbers of these intact vessels and fragments are astounding. Glass production seems to have eclipsed this shape in ceramics such as terra sigillata or Samian ware. Both ceramic and glass forms were, in turn, probably based on precious metal counterparts.

Related Examples

This dish belongs to a select group of mosaic glass vessels that were first studied and published in 1968 by Andrew Oliver, Jr. The group consists of shallow dishes that have a predominantly amethyst ground, a series of bands of alternating amethyst and white, and roughly square segments of monochrome colors dispersed throughout the design. These segments can be seen on the interior but not on the exterior of the vessel. The dishes are rotary ground on the interior and fire polished on the exterior, leaving the surface a bit uneven. There is no stable, flattened base, and the rims are always finished with a cane, usually of amethyst glass spirally twisted with a white trail. The vessels have a consistent diameter between 11.5 and 14.4 cm; the Art Institute’s dish is 13.3 cm in diameter. Oliver notes that several examples, such as the dish in the Corning Museum of Glass (fig. 71.2), have two holes drilled in the body just below the applied trail at the rim. The holes are exactly opposite each other on the vessel, and there is no satisfactory explanation for them. As he noted, one hole would suffice if the vessel were being hung when not in use; it is unclear how the holes might be used to attach handles. There is no evidence that holes were drilled in the rim of the Chicago dish, partly because of restoration. The common elements suggest that all of these vessels were made in the same workshop, and this dish, formerly in the Oppenheimer collection, would be another member of the group.

Two additional complete examples have been published recently, one in the Miho Museum, Shiga, Japan (fig. 71.3), and one in the National Museums Scotland (fig. 71.4). A plate with a flat bottom and flared sides, excavated in the Roman town of Mariana, on the island of Corsica, France, has the same mosaic glass pattern as this group of dishes; its diameter, 12.5 cm, falls within the range of the group as well. It was probably made in the same workshop. Oliver mentioned an extraordinary related example but did not illustrate it; that dish was recently published by the Musée du Louvre (fig. 71.5). The Louvre dish is identical in both height and diameter to the one in Chicago, but the design is unique: laid out in parallel strips of amethyst divided by four white lines, in between are two spiral sections alternating with one square segment. These mosaic glass dishes would soon be supplemented and then replaced by different luxury glassware offered by the new technology of glassblowing.

Hellenistic or Roman?

One might question whether this dish was a product of the early Roman luxury industry or if it belonged to the Hellenistic world. Was it a visual delight on the table of a wealthy Roman whose equally privileged guests might not be easily impressed, or was it a simple vessel form on a continuum from the spectacular technique of the third century B.C.? The mosaic glass canes that compose the bulk of the design have a contrasting central rod around which the spiral is formed. According to some scholars, that is a hallmark of Hellenistic glass manufacture. On the other hand, the use of less-expensive yellow square glass segments to imitate Hellenistic gold glass elements may be a later Roman cost-saving measure. Ultimately, we do not know the manufacturing locations of this early material, and the lack of provenance for the dish denies us any possibility of attributing a more accurate date or confirming a region that might have been under Roman control. We do know that by the first century B.C. these simple mosaic glass dishes were a favorite product of the Romano-Italic factories.

The dish may be Hellenistic or Roman—we cannot say—but it is a highlight of ancient glassmaking in the Art Institute of Chicago. In technique it bridges the centuries from Hellenistic to later Roman production and provides a basis of comparison for other glass in the collection.

Archaeological Material

Ancient authors described gold glasses with parallels in archaeological contexts that relate to mosaic glass dishes. There were several large tomb groups discovered outside Canosa di Puglia in southeastern Italy. Known in antiquity as Canusium, it was located on the Ofanto River about ten miles from the Adriatic Sea; its wealth was based on the production and sale of wool. Lucilla Burn gave a brief description of the glass found in the tombs and highlighted the two well-known Hellenistic gold glass bowls in the British Museum (fig. 71.6). David Grose reproduced a profile of one of these bowls (fig. 71.7) and illustrated a cast plate from Cumae with a flared rim that relates in profile to the plates from Canosa. The Cumae plate is decorated with painted and gold-leaf designs. Grose defined the growth of the glass industry in the Hellenistic period as a renaissance that occurred in stages and in various areas from the late third century B.C. into the Roman period. Among the vessel forms are both deep hemispherical mosaic glass bowls (fig. 71.8) and shallow mosaic glass plates (fig. 71.9). The Chicago dish relates to this early material but is later in date. In addition to the mosaic glass and gold glass, most of the vessels from Canosa and those related to them are monochrome cast, cut, and polished forms (fig. 71.10). A number of groups have come to light somewhat recently without context; one such group, formerly in the Ernesto Wolf collection (fig. 71.11 and fig. 71.12), is now in the Landesmuseum Württemberg. In publishing this group, Marianne Stern documented others known at the time and included one in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (fig. 71.13).

These tomb groups provide a hint of the quantity and quality of luxury glass in the late third and second centuries B.C. The Canosa tombs excavated in the nineteenth century contained far more than glass; they held great wealth in jewelry (fig. 71.14) and other materials. Despite the limited amount of existing archaeological evidence, the objects that do survive, combined with the ancient descriptions of treasured possessions and an overview of some of the surviving material in other precious media, allow us to form an impression of the esteem in which these rarities were held.

Historical Context

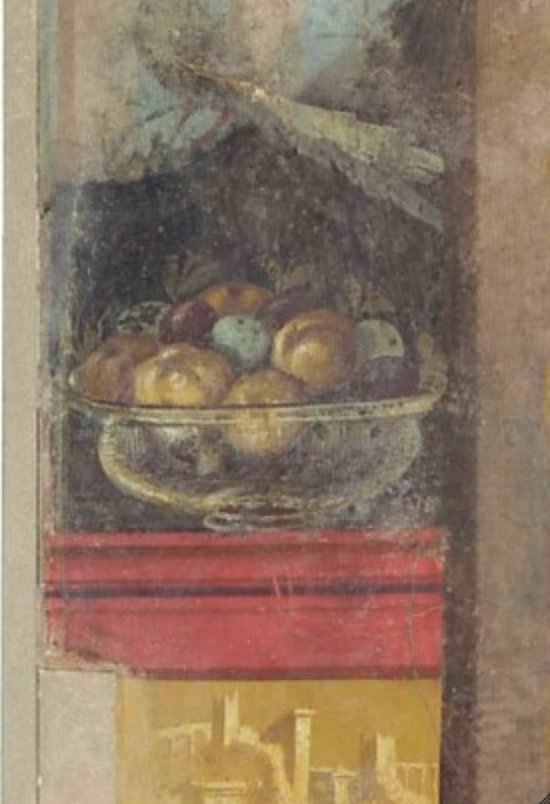

Placing these complex and costly glass objects in context is actually quite difficult. To date, there are no contemporary wall or panel paintings that illustrate the use of glass vessels, despite their popularity, which is evident from the number of existing objects and fragments. Ancient sources that can offer some level of insight about wealth and excess describe vessels of silver and other precious materials but contain little about mosaic glass. There are exotic scenes of interest in the famous Nile mosaic (fig. 71.15) from the area of the sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina (ancient Praeneste) east and slightly south of Rome. Both the subject matter and dating of the mosaic are subjects of scholarly debate, but the scenes focus on the Nile, the Mediterranean, and the Roman fascination with all things Egyptian around 100 B.C. Paul Meyboom suggested that the mosaic depicts rituals connected with Isis and Osiris and the annual Nile flood.

The rituals and celebrations depicted in the mosaic (fig. 71.16 and fig. 71.17) offer a glimpse of the use of silver and gold vessels in dining and celebrations. In the first scene a figure in a group raises a silver rhyton, or drinking horn, acknowledging three figures across the water who drink from silver bowls that have parallels in contemporary monochrome and mosaic glass vessels. In the second detail, soldiers participate in a ritual, with one lifting a silver rhyton in a group near a table where three more rhyta sit next to a huge gold krater (a large wine container) on the ground. The number of costly vessels in these scenes seems sparse compared to the tens of thousands of silver and gold vessels described by ancient authors that poured into Rome from the third century B.C. onward. While almost continuous wars abroad brought vast wealth to the Romans, later civil wars of the first century B.C. stoked their constant fears of property confiscation, flight, or death. Shortly after the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra by Octavian in 30 B.C., for the first time in more than two hundred years the doors of the Temple of Janus were closed as a sign of peace; the prosperity and stability that followed were unprecedented. While the Nile mosaic offers one glimpse of costly vessels in the period roughly contemporary with this mosaic glass dish, to date there are no known representations of glass until after the development of glassblowing in the late first century B.C. By this time, the elegant Roman table was provided with precious metal vessels and blown glass decorated in different styles. Mosaic glass had fallen out of fashion, replaced by a taste for colorless glass with cut decoration. Blown vessels can be seen in dining scenes painted on interior Roman walls (fig. 71.18). Here one could admire not only the skill of the artist in rendering the curve and highlight of the glass vessel but also the beauty of the fruit that this wondrous material allowed one to see (fig. 71.19).

Ancient Authors

The ancient authors who described the military conquests and their resulting riches had conflicting reviews of their effect on the people of Rome. When Scipio brought 1,400 pounds of engraved silverware and gold vases weighing 1,500 pounds into the city from his Asian triumphs in the early second century B.C., the Roman historian Pliny the Elder lamented that Rome learned not just to admire foreign opulence but to love it.

The orations of Cicero against Gaius Verres, the propraetor of Sicily in 73–70 B.C., are famous for exposing the excesses of his egregious conduct in the pursuit of wealth. His actions were so outrageous that the Roman Senate honored the Sicilians’ request to bring Verres to trial for misconduct and extortion. Cicero was the brilliant prosecuting attorney and Verres went into voluntary exile. According to Cicero, and this is just one accusation, “After he [Verres] collected such a huge amount of tableware decorated with relief . . . he established an extremely large workshop in the royal residence in Syracuse. Then he publicly ordered that all artists, engravers, and metalworkers be assembled . . . the work assigned [them] . . . required eight straight months to complete, even though nothing was made but gold vases. For those ornaments which he had torn off plates and censors, he now had tastefully attached to gold drinking cups and so appropriately inlaid in golden bowls that you would have said that they were created for just this purpose.”

Livy, like Pliny, complained about this vast wealth pouring into Rome and how it would forever change the rustic and stoic Roman life. His comments are attributed to a speech by Cato. “You have often heard me complaining about . . . how the state suffers from two diverse vices, avarice and luxury . . . I come to fear these even more as the fortune of the Republic becomes greater . . . for I fear these things will make prisoners of us rather than we of them.”

Only a short passage from a late second-century A.D. author, Athenaeus of Naucratis, mentions luxury glass, and he actually references an earlier work of the second century B.C. The passage describes a third-century B.C. procession of Ptolemy II Philadelphus: “Next in the procession were four large three-legged tables of gold, and a golden jewel-encrusted chest for gold objects . . . two cup stands, two gilded glass vessels, two golden stands for vessels which were six feet high.” We do not know the source that Kallixenos of Rhodes consulted, so we cannot know whether it was describing a glass with gilt decoration or a gold glass vessel; an observer at a triumph would probably not have been able to make such a distinction.

Luxury Goods: Rock Crystal, Vasa Murana, and Silver

The ancient passages noted here provide a glimpse of the greed of some unpopular Romans and the lengths to which they would go to secure a prized possession. Glass imitated many of these precious materials, from rock crystal to veined stone, but none achieved legendary renown until the invention of glassblowing.

Throughout antiquity, vessels of rock crystal were a coveted commodity of the very wealthy. Pliny described Nero’s last moments “when he received the news that things were hopeless, broke, in a last fit of rage, two crystal goblets by dashing them on the ground. This was the revenge of a man who . . . made sure that no one else could drink from them.”

Stories of vasa murana show even more excess. As Pliny related: “An ex-consul drank from a murrhine cup for which he had given 70,000 sesterces . . . He was so fond of it that he would gnaw its rim; and yet the damage . . . only enhanced its value.” Nero confiscated all of the consul’s goods, including his vast murrhine vessel collection, and exhibited them in the private theater where the emperor rehearsed his musical performances. The fragments of one vessel particularly revered by Nero were placed in an urn in order to emphasize the loss of this rare object. Pliny saw this installation and likened the display of the fragments to the veneration of the body of Alexander the Great.

There have been many theories about vasa murana, or murrhine vases. Some believed that they were actually mosaic glass. Most recently, Alain Tressaud and Michael Vickers discussed the material in a comprehensive article. Pliny had already described its properties; it is fluorite, also called fluorspar—a soft, multicolored, veined stone that was found in small chunks. It was difficult to carve, owing to its often heavily fractured composition. In antiquity, fluorite was mined in Parthia (modern Iran) and may have been coated with a resin and heated to keep it stable while carving; that resin may account for the flavor such vessels were said to impart to wine. Tressaud and Vickers pointed out that fluorite is slightly softer than tooth enamel, while other popular ancient gemstones such as quartz, onyx, and agate are all harder. Even dismissing the ex-consul’s habit as apocryphal, the vessel was fluorite. Until recently there was only one fluorite vessel known from antiquity. It is a kantharos, or two-handled cup, in the British Museum, known as the Crawford Cup (fig. 71.20); it has veining of green, purple, and cream with a waxlike surface. In 2004, the British Museum added a second fluorite vessel, the Barber Cup (fig. 71.21), said to have been found in the same tomb as the Crawford Cup by an Austro-Croatian officer near the border between Syria and Turkey during World War I. This one-handled cup has more translucent veining but similar coloring. The globular body is decorated with a low-relief panel of vine leaves, grapes, and tendrils; under the handle is a bearded head, probably Dionysos or one of his companions. The notion that a craftsman would have attempted to add wheel-cut decoration to such a fragile object must have increased its value significantly.

As early as 1949, A. I. Lowenthal and D. B. Harden had convincingly shown that vasa murana could not be mosaic glass, although Pliny did mention a glass imitation of the costly material. So the mosaic glass technique was used to imitate various complex marbles, semiprecious stones, and even this rarest banded mineral. One wonders how many guests were impressed nonetheless by such clever and costly replications.

We have a better impression of silver vessels used in this early period owing to the richer archaeological record. The Hellenistic silver hoards from Nihawand (fig. 71.22) in Iran spanning the fourth through the second centuries B.C. and the Rogozan treasure (fig. 71.23) in Bulgaria composed primarily of fourth-century B.C. vessels exemplify the diversity of cultural and artistic tradition as objects were traded throughout the region. The Republican and early imperial Roman silver from Tivoli (fig. 71.24), some examples of which are currently on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago from the Field Museum of Natural History, and the treasure from Hildesheim (fig. 71.25 and fig. 71.26) manifest the quality and quantity that begin to match the descriptions provided by ancient authors. Such elegant silver vessels would have been displayed on the Roman table among glass and precious stone containers, the finest tableware a Roman host could afford.

Sidney Goldstein

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This shallow dish is made of soda-lime glass and was fabricated using the mosaic glass technique (fig. 71.27). Four separate colored glasses, both opaque and transparent, were chosen for the components of the canes, which were cut in both disk and ribbon form. Evidence of manufacture is seen in tooling around the rim and in the fire-polished surface of the exterior. The object is fragmentary with considerable losses and has undergone extensive restoration of an extremely high quality.

Structure

Chemical Composition

Primary material: silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2)

Secondary materials: soda (sodium oxide, Na2O); lime (calcium oxide, CaO)

Trace materials: manganese, Mn (colorant); cobalt, Co (colorant; presumed); opacifiers

Glass consists of three basic ingredients: a bulk material, or former; a modifier or fluxing agent to reduce the temperature of the former; and a stabilizer.

Silica is the major component of glass; in ancient glasses it is present at levels of between 65 and 70 percent. The primary source of the silica used for glassmaking is the product of the geological weathering of silicate minerals found in the earth’s crust, typically sand. The precise composition and grain size of the sand, as well as the degree and nature of the impurities it contains, are determined by the constituents of the parent rock and the distance traveled from the parent material. Sands generally considered optimal for glassmaking have a consistent grain size and contain a large percentage of quartz.

The melting point of silica is between 1710°C and 1730°C. Sodium, as a fluxing agent, lowers the melting point to between 1100°C and 1200°C. Most early Roman glasses are referred to as natron glasses, implying that the sodium source was the mineral natron, an evaporate with the chemical formula Na2CO3·10H2O. In fact, natron is quite rare; the more probable source was trona, a sodium sesquicarbonate with the chemical formula Na2CO3·NaHCO3·2H2O. Soda makes up roughly 25 to 30 percent of ancient glasses.

Without a stabilizer, glass composed solely of silica and soda would dissolve in water. The addition of approximately 5 percent calcium, in the form of lime, is therefore necessary to make the glass durable. Shell fragments are the most likely source of the lime used in ancient glass.

Fabrication

Method

The dish was created using the mosaic glass technique. In the mosaic glass manufacturing process, lengths of variously colored glasses were assembled to create a design, such as a spiral, a rosette, or even a face. The bundle was then heated, marvered together, and pulled from both ends to form a thinner cane with the design preserved along its entire length. That cane was cooled and cut into manageable pieces, possibly one or two feet long. These shorter pieces in turn were cut either crosswise or lengthwise to form small sections or segments.

In broad outline, the next step in the process was to arrange and assemble the glass elements and slowly heat them in order to fuse them into a solid mass of glass that would then be shaped into a dish. There is no surviving evidence of the specifics of this procedure, but modern scholars and glass artists have proposed various ways that these shapes might have been made. On visual inspection, many mosaic glass dishes appear to have been cast in multiple-part molds, then finished by grinding and rotary polishing. This was a process first proposed by Frederic Schuler in the 1950s. More recently, scholars and glassmakers have theorized that the glass might have been sagged or slumped.

Sagging and slumping are techniques long known in the Venetian tradition of glassmaking, and both are still used today. Slices of canes are arranged in a circle and heated together to form a flat blank or disk. While the disk is heated, it is squeezed from the sides to compress the elements and eliminate any space between them. The disk usually requires several rounds of heating, tooling, and reheating to accomplish the finished blank. Then the disk can be placed over a raised form or into a concave mold in the desired shape of the vessel and heated and tooled to take the shape of the form.

On the other hand, there are mosaic glass forms whose unfinished, uneven rims appear to have been supplemented by the addition of segments of cane beneath the single continuous cane that creates the finished rim. The presence of these filler elements suggests that the irregular top edge of the object is the result of fusing the glass elements in a two-part mold. Inside a mold, the glass could not have been manipulated as it was heated, so the glassmaker could not have compressed the edge into an even shape. The artist would not have ground down this costly material but would instead have added a contrasting trail in several layers to build up an even rim. Presumably these layers could have been added while the unfinished blank was still in the mold.

As a final step, almost all glass objects need some amount of finishing or polishing to remove imperfections left by fabrication processes. Generally speaking, vessels made using the sagging or slumping technique only require finishing on the side that was in contact with the mold, because the applied heat from the annealing furnace causes a shiny surface known as a fire polish on the exposed side.

For this dish, the glassmaker used canes circular in cross section, created by winding transparent amethyst and opaque white glass around a transparent blue round center, and by winding transparent blue and opaque white glass around a transparent amethyst round center. These were cut crosswise to form circular sections with spiral designs. There is one section that was cut from a cane made by winding transparent blue and opaque white glass around a transparent amber round center (fig. 71.28). Canes rectangular in cross section were made by layering strips of transparent amethyst and opaque white glass. These were cut crosswise to form rectangular segments of amethyst glass separated by two bands of white glass. One segment was cut from a cane made by layering strips of transparent blue and opaque white glass (fig. 71.29). Additional square segments were cut from marvered rods of opaque yellow and white glass.

The glassmaker arranged the elements such that the pattern on the interior is markedly different from that on the exterior. The interior consists of roughly equal numbers of blue and amethyst spirals interspersed with 27 of the rectangular amethyst and white segments. These are placed randomly about the interior with the addition of 18 of the opaque white square segments and 16 of the opaque yellow square segments. While the spiral and banded canes can be seen on both the interior and exterior surfaces, the monochrome segments can be seen only on the interior. This indicates that the dish was fabricated using two layers of assembled elements.

This vessel demonstrates a relatively level top rim around which was wrapped a single cane of amethyst glass spirally wound with opaque white. The evenness of the rim and the absence of any supplementary filler elements below the spirally wound cane lend some weight to the theory that the object was sagged or slumped rather than molded. The final form is a shallow dish with convex sides and a slightly flattened bottom. The interior of the vessel was rotary ground on a lathe, and the rim was rounded and polished with abrasives.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The rim of the dish is slightly everted on one side with a lathe-cut groove on the outside edge.

Distortion and stretching during the fabrication process moved the canes off axis, and as a result, some of the design was rendered slightly less legible. This effect is more pronounced on the exterior of the dish, which also shows a large amorphously shaped patch of yellow and green glass (fig. 71.30). This degree of warping suggests that the glassmaker actively pressed or manipulated the glass with an implement, as might have been the case if the vessel was sagged over a convex form and worked from the back. The discordant splash of yellow and green could be supplemental pieces of glass added during the shaping and smoothing process.

A few entrained air bubbles are visible throughout but are generally free of distortion and have not formed striae.

A glossy sheen, the result of fire polishing, is visible on the exterior bottom face.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the surface revealed no traces of polychromy, gilding, or other embellishments.

Many dishes of this type have two holes drilled into the body just below the applied trail at the rim. The relevant areas of the side walls have been restored on this dish, so it cannot be determined whether or not they were drilled.

Condition Summary

The dish is fragmentary and is missing a considerable amount of its original fabric.

Some of the fragments appear to be in excellent condition, while others show significant erosion, particularly along the break edges. Overall the surface of the glass exhibits a great deal of pitting. Areas of long parallel scratches as well as deep gouges are present throughout and are most noticeable in raking light. These marks are consistent with the removal of a weathering crust by abrasive action; it is therefore possible that the glass once bore a layer of corrosion that obscured the design. Small traces of silver iridescence on the outside of the dish support this hypothesis, as does the presence of numerous exposed air bubbles in the form of small holes filled with white material.

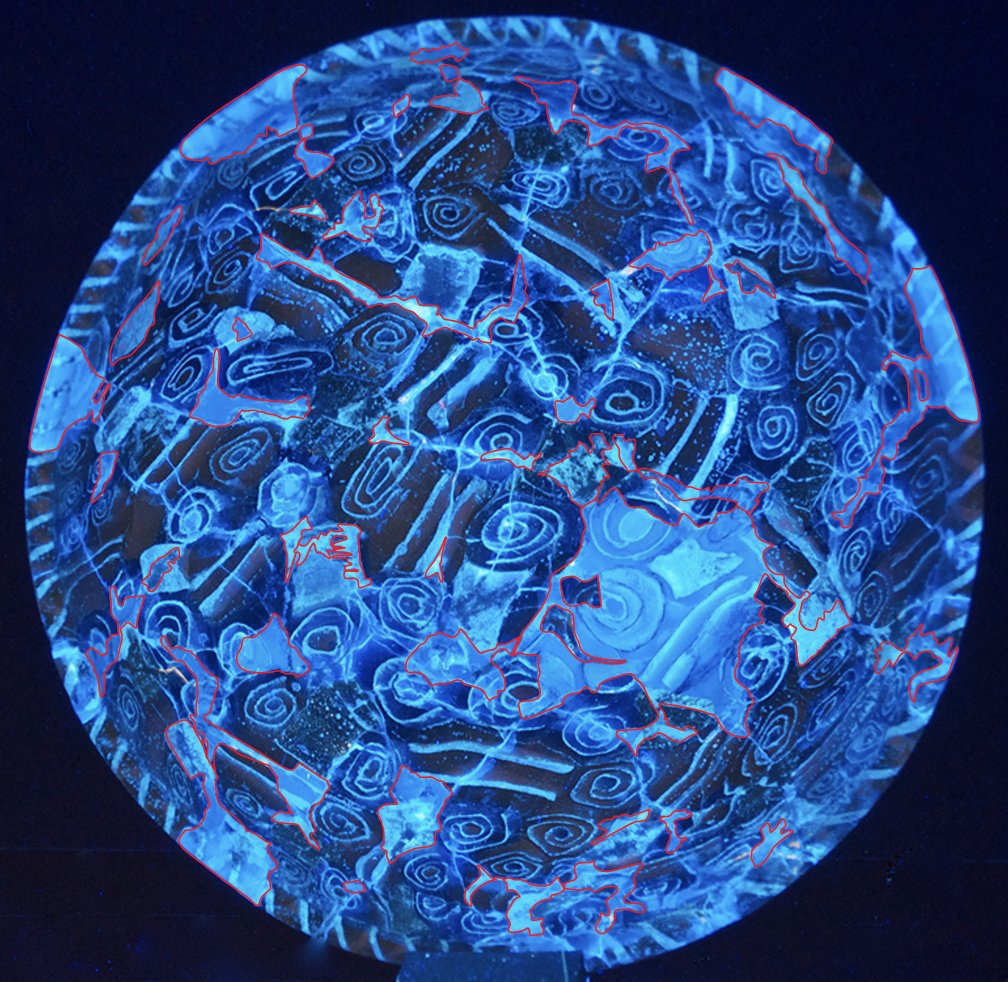

When viewed in normal light or against a solid backdrop, the object looks opaque and the canes have a flat appearance. When viewed in transmitted light, the vessel looks transparent, and the arrangement of the glass elements in two layers is quite clearly visible (fig. 71.31).

Conservation History

There is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection.

Prior to acquisition, the object was heavily and quite skillfully restored. After bonding the fragments, the restorer used a tinted resin, most likely an epoxy but possibly a polyester, to create fills mimicking the appearance of the canes, several of which cannot be detected without the aid of ultraviolet radiation (fig. 71.32). In one area of restoration, two fragments of real glass were inserted into the fill material (fig. 71.33). Presumably the restorer noticed the correct profile of the fragments and was able to place them in their original positions despite the absence of the immediately adjacent fragments. Fills to the rim do not appear to be inlaid with resin as the fabricated canes are, but rather overpainted to match the relevant design. Some overpainting is also visible in opaque areas and in the areas of white striping in the banded segments. No effort was made to camouflage the break edges between the fragments. Some of the fills, notably around the rim, exhibit yellowing (fig. 71.34). It is not certain whether these particular fills were tinted and have now faded or if they were initially colorless.

Based on photographic evidence in the Christie’s auction catalogue for the collection of the late Henry Oppenheimer, the vessel had been restored by a different hand sometime prior to the date of sale, July 22–23, 1936.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Sidney Goldstein

Selected References

Christie’s, London, The Collection of Egyptian, Greek and Roman Antiquities, Cameos and Intaglios Formed by the Late Henry Oppenheimer, sale cat. (Christie’s, July 22–23, 1936), pp. 38–39 (ill.), lot 114.

Andrew Oliver, Jr., “Millefiori Glass in Classical Antiquity,” Journal of Glass Studies 10 (1968), p. 65, no. 6.

Christie’s, London, Ancient Egyptian Glass and Faience, pt. 3, sale cat. (Christie’s, Dec. 8, 1993), pp. 22–23 (ill.), lot 27.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Acquisitions: July 1, 2004–June 30, 2005,” Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 2004–2005 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2005), pp. 20 (ill.), 30.

Corning Museum of Glass, “Recent Important Acquisitions,” Journal of Glass Studies 47 (2005), p. 215, cat. 1 (ill.).

Karen Manchester, “Mosaic Glass Dish,” in “Notable Acquisitions at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 32, 1 (2006), pp. 46–47 (ill.), 95.

Karen Manchester, Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), pp. 66–67, cat. 12 (ill.), fig. 12.1; 111.