In some ways this is among the last coins of the classical age of Rome. In words and images it harks back to the glory days of the Roman Empire, introducing no obvious innovations in iconography or titulature. That was just about to change. The main novelty of this coin lies in the denomination, which reflects the restructuring of the coinage in the face of extreme inflation. We will look at that first, then note several subtle clues to deeper messages in this coin.

Constantine began his rule while the Tetrarchy, established by Diocletian in A.D. 293, was still in place. In order to better defend Rome’s far-flung borders, Diocletian had first appointed a co-augustus in 286. Diocletian then created the Tetrarchy to expand on that success and to regularize the succession. He set up two senior emperors (augusti, of which he was one) and two junior colleagues (caesars), forming a college of four rulers who ruled, theoretically, as one. The idea was that at an opportune time, Diocletian and his co-augustus Maximianus would retire, the two caesars would step up and become augusti in their turn, and two new caesars would be appointed, eliminating the bloody scrambles for power that had been the norm since midcentury. Diocletian and Maximianus retired in 305, succeeded by their caesars (now augusti) Galerius and Constantius I Chlorus; the new caesars were Valerius Severus and Maximinus Daia. But when in A.D. 306 the augustus Constantius died after a successful campaign in Britain, his caesar, Severus, was snubbed by the army. Constantius’s troops (in good late-imperial fashion) acclaimed his son Constantine imperator. This upset the careful and tenuous balance of power among the remaining augustus Galerius and the two junior caesars, Severus and Maximinus Daia; and before long the retired Augustus Maximianus, his disaffected son Maxentius, and a few newcomers like Licinius were also up in arms.

The critical moment, in retrospect, was the defeat on October 28, A.D. 312, of Maxentius by Constantine at the Milvian Bridge, where the Via Cassia enters the city of Rome from the north. At that battle, Constantine’s army fought under a new standard (the labarum) marked with the chi-rho monogram as a talisman of the favor promised to them by the Christian God. Constantine attributed his victory over Maxentius’s superior forces to the help of Christ, and he immediately began public declarations of his benevolence toward the forbidden religion. The Edict of Milan promulgated by Constantine and (reluctantly) Licinius in 313 ended the persecution of Christians across the empire. He split the empire with Licinius, who married Constantine’s sister and became augustus of the East (after fighting his own rivals there). However, territorial aggression by Constantine, and Licinius’s retraction of the toleration he had been forced to offer Christians, soon undermined this détente. In A.D. 324 Constantine defeated Licinius at the battle of Chrysopolis (modern Scutari, directly east of what was to become Constantinople). By this action he reunited the whole empire under a sole ruler for the first time since Diocletian had shared the role of augustus with his colleague Maximianus in A.D. 286.

Even before becoming sole ruler, Constantine attempted to address the soaring inflation that had plagued the empire since the crises of the third century. Aurelian in the 270s and Diocletian in the 290s had both attempted to restore the gold and silver coinage to earlier standards of purity, if not weight, and to stabilize the silvered bronze and bronze coins (nummi) of various denominations that served as the actual money in circulation for everyday transactions. Due to the scarcity and rise in price of precious metals, however, the restored silver coinage of Diocletian (the argenteus) was discontinued by around A.D. 310–13, and by 309 Constantine was constrained to lower the weight of the gold coinage, creating the solidus (“solid bit,” minting 72 coins to the pound) that we have here. (The heavier aureus continued to be struck at 60 to the pound in the wealthier East by Licinius; its career and Licinius’s ended at the same time.)

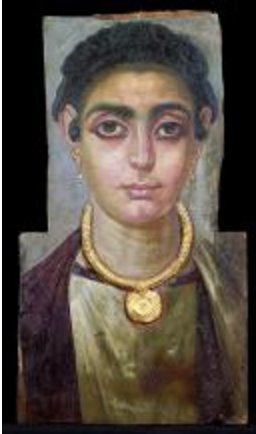

Gold coinage and silver medallions in this period seem to have been used primarily for donatives and congiaria (ceremonial distributions of coins to the legions and to the urban plebeians, respectively). By the time of Constantine, donatives were more restricted and modest than in the heyday of imperial expansion, a mere five solidi per person. The recipients would generally not spend these coins as currency: since the skyrocketing rate of inflation meant that a single silver argenteus of Diocletian would already have been worth large bags full of nummi, any silver or gold would be banked, buried, and kept for emergencies. Hoards of gold and silver from the late third to early fourth century illustrate this fact. The lack of circulation helps explain the remarkable absence of wear on gold coins and silver medallions of the era. Another way to safeguard or to bequeath a donative was to eventually incorporate coins into jewelry for men and women, such as pendants or belts (see fig. 24.1, fig. 24.2, and fig. 24.3); this coin shows signs that it may once have been so mounted. The value of this coin, in terms of the economy of the period, gives a breathtaking sense of what it meant to receive one as a donative. Given the ratio in commodity price of silver to gold, this solidus would have equaled roughly 1,389 denarii communes. Despite its apparent lack of useful correspondence to the other coinage of the era, Constantine’s solidus seems to have been “right-sized” for the needs of the era, since it remained the standard gold coin in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) until the eleventh century. Indeed, Constantine’s solidus has been called the most important evolution in the monetary system of late antiquity, providing a stable model for gold coinage used not only for military pay and imperial gift-giving but eventually for general civilian mercantile purposes as well, especially in the Mediterranean area.

The iconography of this coin holds some surprises. One would expect the first Christian emperor’s coins to illustrate his religious adherence after the Edict of Milan, but Constantine’s coinage displays only indirect allusions to Christianity, and only in areas he directly controlled. Licinius, despite his grudging acceptance of the Edict of Milan, used only traditional Roman images on his coins, while Constantine’s mints after A.D. 313 experimented with ways to incorporate the symbolic language of both pagan and Christian culture. Not only was Christianity a minority religion, but many of Constantine’s important supporters were pagans, and early in his career he could not afford to offend. Examples of convincingly Christian symbols are few and extremely timid: the use of the chi-rho or a cross as part of a mint mark, for example. On a rare silver medallion (minted in A.D. 315 at Ticinum/Pavia as a donative, probably for his decennalia) the chi-rho appears at the base of the plume on Constantine’s helmet—barely visible to the naked eye—and he carries a cruciform standard. What may be the boldest Christian symbol appears only in A.D. 327, well after the defeat of Licinius, on a rare bronze coin from Constantinople itself—from a new mint in a new city that was founded by Constantine as a Christian city, in direct contrast to Rome. It shows the labarum transfixing a supine serpent, just as described by Eusebius in his Life of Constantine. Also sometimes interpreted as indicative of the emperor’s religiosity is the “heavenward gaze,” described by Eusebius regarding the famous colossal portrait of Constantine from the Basilica of Maxentius. He specifies that after the Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325), Constantine directed that his image in this “posture of prayer” be put on the gold coins. Despite Eusebius’s comments, the “heavenward gaze” was not a novelty. It was already to be seen in portraits of the tetrarchs, of contemporary philosophers, and even of some earlier rulers such as Commodus, and ultimately derived from Hellenistic portraits of Alexander the Great. At any rate, that gaze does not appear on this coin.

Constantine’s reverses, for the most part, are carefully neutral regarding religious allegiance, even after 324. We must keep in mind that although Constantine made it legal to be Christian, he did not and could not make it mandatory; it would be nearly a century before a Roman emperor dared to order the pagan temples closed and the ancient sacrifices abandoned. Scholars disagree over the degree to which Constantine tolerated the survival of pagan religious practice, but it seems clear that while he deplored and probably forbade blood sacrifice, it was nearly impossible and definitely impolitic to enforce this. He did confiscate some temple treasuries, but recognized the social and traditional utility of other pagan establishments. On Constantine’s coins, references to providence, victory, and the glory of the army take the place of specific deities. Mars and Jupiter are indeed invoked as protective figures (e.g., Iovi conservatori) until A.D. 324, and Sol Invictus, the unconquered sun (to which cult Constantine was drawn early in his life), remains on the coins until at least A.D. 317. But the latter was already widely assimilated to Christian symbolism, and the former could be interpreted more as allegories of martial valor than of actual pagan gods. Besides, it is not at all clear what Christian symbols he could have put on the coins. Since early Christianity had developed under the shadow of outlawry, visual manifestations of the new religion were safely ambiguous, sharing pictorial conventions with long-established pagan usage. An explicitly Christian iconography had yet to evolve. The chi-rho, labarum, and heavenward gaze could all be interpreted in non-Christian ways.

The most suggestive evidence regarding Constantine’s religious leanings may be what is not on his coins. Shortly after this coin was minted, the conventional headgear of the rulers, the laurel wreath, was suddenly replaced by the plain or rosette diadem. This happened in A.D. 325, that is, after the Council of Nicaea called by Constantine to address the unrest occasioned by the heresy of Arius. The laurel wreath of victory had decked the brows of Greco-Roman gods, goddesses, heroes, and emperors on coins for at least 800 years; it may have carried too strong an association with pagan rulers and gods to be comfortable on the head of the emperor who could convene an ecumenical council. Negatives are hard to prove, however, and the absence of the laurel wreath, like the absence of the usual array of deities, is only suggestive. Like the heavenward gaze, it may just as well have signaled Constantine’s assimilation to Alexander the Great who, like himself, had conquered the East. (Interestingly, the Romans had shunned the diadem until then, since it connoted abhorred ideas of kingship or tyranny.) Constantine’s sons and successors would make free use of the labarum, the upward gaze, and eventually a whole panoply of Christian symbols on their coins, but the issues of Constantine himself do not offer much evidence of this pivotal moment in Western history.

Constantine’s victory over Licinius at Chrysopolis in September A.D. 324 inaugurated a number of changes, in the empire and in the coinage. As the sole ruler of the empire, Constantine prepared to celebrate his vicennalia, his twentieth year of reign, which would begin on July 26, 325. Before that, he raised his sons Crispus and Constantine (II) to the rank of augustus, and his youngest, Constantius, to the rank of caesar, while conferring the honor of augusta on his wife, Fausta, and his mother, Helena. With new access to the greater wealth of the East he not only struck coins such as this solidus, but also restored the churches destroyed by Licinius and began the reconstruction of the ancient city of Byzantium, renaming it after himself: Constantinople. He spent most of the year in the vicinity, except perhaps for a brief spell of time in Antioch, which this coin suggests he visited late in the year A.D. 324 to early in 325; the mark SMAN* in the exergue (beneath the image) identifies the mint of Antioch.

The reverse of this coin proclaims A[D]VENTVS AVGVSTI N[ostri], “the coming of our Augustus,” and suggests that this issue—one of the first to be minted after the defeat of Licinius—was to be used as a donative to the victorious troops. The adventus type was already quite old; typically, it represented the arrival of the emperor on horseback to the city in question, wearing armor, cape fluttering, arm raised in a gesture of greeting or benediction. In this instance, the emperor carries a scepter rather than the spear seen on some other issues; along with the fact that Constantine wears no armor on the obverse portrait, the military aspect is downplayed and an emphasis put on his imperial dignity. It should be noted that in 2006, an imperial scepter and other regalia were found carefully buried on the slope of the Palatine Hill near the Arch of Constantine. It is theorized that these are the regalia of Maxentius, hidden before Constantine’s victorious entry into Rome in 312. It is the only surviving scepter from the era (fig. 24.4). The adventus type would later find new life in Christian art, in scenes such as the entry of Christ into Jerusalem; in this example, it is more of a throwback to Trajan and other emperors of Rome’s golden age whose coinage reflected their beneficent entries into fortunate cities of their realm, which basked in the imperial presence. Adventus ceremonies were important as signifying that a city was a vital and appreciated part of the empire, and in turn that the emperor was a welcome and legitimate ruler.

The obverse portrait and inscription are fairly conventional; most of the excitement lies in knowing of the transformations that will reshape Rome (and the coinage) in the coming months. Still, a careful reading of the image is revealing. The coin presents a simple head of Constantine, facing right. He still wears the laurel wreath that had been the hallmark of Roman imperial coinage for nearly 350 years, but that would cease appearing on coins in just a few months. There is no indication of military or ceremonial garb; the cord of his wreath rests on the hint of a bare shoulder, suggestive of a heroic nude statue. His head is level and his eyes do not yet gaze heavenward, but rather look straight forward, with the military precision and no-nonsense mien that are so familiar from the third-century “barracks emperors.”

However, unlike the barracks emperors who preceded him and even unlike Diocletian, Constantine is clean-shaven and his visage is ageless and serene; he is the first emperor to so present himself in more than half a century. While his profile may appear quite stylized, art historians have been able to trace Constantine’s genuine physiognomy over his long career. His long nose, hint of a receding chin, and slightly fleshy jaw are apparent on this coin, as on other coin issues and in sculpture, such as the “Boar hunt” medallion on the Arch of Constantine, dedicated in A.D. 315. Significantly, they have also discerned in his coin portraits visual allusions not only to Alexander the Great but probably to Trajan and certainly to the first emperor, Augustus. The eternally youthful, idealized, and heroic features of the founder of the Pax Romana have clearly influenced Constantine’s portrait on this coin, especially compared to the scowling, stubbled, and (arguably) realistic faces of his third-century predecessors, and to the indistinguishable faces of the Tetrarchs. The evocation of the Augustan Golden Age is carefully calculated for political ends, and is supported by the revival of classical style in Constantine’s building programs. This deliberate manipulation of his portrait to look like himself while also reminding the viewer of Augustus can be seen as early as his victory over Maxentius in 312, while the Alexander-like details appear shortly after Constantine reunites the empire in 324, though not yet on this coin. The Roman tradition of realistic portraiture has its last great fling under Constantine. His sons and successors would adopt a more hieratic and schematic technique for their public images.

Besides the bare bones of his cognomen, Constantinus, the obverse inscription includes the initials P F, standing for pius et felix (dutiful and happy), typical of the inscriptions of the later Roman emperors (who were, generally speaking, neither). These names had been closely associated with the religious duties of the emperor as pontifex maximus, the “chief builder of bridges” between the Romans and the gods. As his convocation of the Council of Nicaea attests, Constantine still bore that duty, though he may have seen it rather differently than his predecessors had. AVG[ustus], the final part of the inscription, had been part of the official names of the emperors since it was first voted to Octavian Caesar by a grateful but cowed Senate in 27 B.C. However, since Diocletian’s radical reimagining of the title in A.D. 293, it had another connotation. As late as A.D. 310 there had been four augusti circling each other warily, while the coinage urged the providentia (foresight) of the multiple augusti; this coin, on the other hand, seems serenely to dismiss the possibility of rivals.

After this coin was minted, Constantine continued his preparations for his vicennalia. He provided Constantinople with a mint, convoked the ecumenical Council of Nicaea to settle the questions of heresy that had troubled the region, and headed off to Rome to wrap up a year of celebration. It was to be a terrible year, during which his son Crispus, his wife Fausta, his former colleague Licinius, and Licinius’s son would all be executed on his orders, on obscure charges. He would break with the Roman aristocracy and turn his back on the Eternal City, making Constantinople his new home and the new capital of a very different Roman world. It would endure as such until 1453.

Theresa Gross-Diaz

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This coin is made of relatively pure gold; trace amounts of other elements are also present. It was struck with a free-floating reverse, resulting in a die axis of 11:00. The carving on the dies was fantastically detailed and well executed; nonetheless, several visible flaws indicate that the dies were not new at the time of striking. The coin is in good condition overall, marred only by scratches on both the obverse and the reverse. Visual examination of the outside edges strongly suggests that the coin was at one time incorporated into a metal mount, possibly for use as a pendant. No written records of treatment accompany the object in either the conservation or the curatorial files.

Structure

Chemical Composition

Primary material: gold, Au

Secondary materials: copper, Cu (trace amounts); iron, Fe (trace amounts); silver, Ag (trace amounts)

Ancient coins were typically fabricated using gold, silver, electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver), and copper alloys. Bullion for the production of coins was obtained principally through mining operations and the collection of surface deposits. The Romans sourced silver and gold from the plentiful veins in Spain, but also used mines in Gaul, Dalmatia, Dacia (in the Carpathian mountains), Britain, the Near East, and Africa. Ores were not the only source of bullion, however: war booty, tariffs paid by other states, stored wealth in the state treasury, and existing coinage could all be melted down and reminted.

The purity of the metal used for minting was highly regulated and carefully overseen. Throughout the Greek and Roman periods, gold coins were particularly refined, usually containing more than 95 percent pure gold. Silver coins had a somewhat smaller but nonetheless impressive degree of purity. For most of Roman history, the purity of the coinage seldom wavered. By the late Imperial period, silver coins had been significantly debased, containing as little as 2.5 percent silver. Even the debasement of coins, however, was closely monitored.

Determining the precise composition of ancient coins is difficult. For a variety of reasons, the surface of a coin is unlikely to be representative of the composition of its interior. While qualitative information can be obtained using minimally invasive methods that analyze the surface of a coin, quantitative results require abrading or removing the surface in order to analyze material closer to the heart metal at the center, an approach that is generally unacceptable in a museum context.

Fabrication

Method

The coin was struck by hand.

Hand striking a coin is performed in three distinct operations: the creation of a flan (or blank), which is the plain lump or disk of metal that receives the image; the creation of a die, which is the stamp used to impress an image on the flan; and the striking of the coin itself.

In order to create flans of a consistent weight and composition, it was first necessary to smelt and refine the bullion. Surviving coins attest to the fact that Roman metalsmiths possessed sufficient knowledge and skill to obtain a high degree of purity and to adjust the alloys to precise specifications. The refined, molten metal was poured into open or two-part clay molds. Gold and silver coins may have been cast in individual molds, but coins could also be cast en chapelet, using open or closed molds connected by channels.

Metal dies were used to impress an image onto the flan. Few ancient official dies survive today: when a die reached the end of its useful life, because of wear or the discontinuation of the design, it was typically destroyed to prevent unauthorized use. Nonetheless, enough evidence remains to conclude that the dies were usually made of a bronze alloy containing a relatively high percentage of tin that could be made sufficiently hard to strike even bronze coins. The vast majority of images on ancient coins are in relief. This means that the images on the dies were carved in intaglio, as a negative image below the metal surface of the die, similar to the way stone seals were cut or engraved, giving a mirror image of what would be displayed on the coin. Also as with stone engraving, the tools were made of iron and would have included punches, burins, chisels, and drills.

Two dies were usually employed in striking a coin. The obverse (lower) die was fixed in position, usually into an anvil or a block of wood. The reverse (upper) die was loose; the image could be engraved directly into the base of a cylindrical or pyramidal piece of metal or, more commonly, into a bronze disk that was fitted into an iron punch or collar. The obverse die was used to stamp the more important side of the coin, which often displayed deeper or more intricate images. Its protected position in the anvil gave a better chance of a clean impression.

The life-span of a die depended on a number of factors: the composition of the metal, the size of the die, the depth of the relief, and the number of coins made. The obverse die wore down less quickly than the reverse die, which was struck repeatedly with a hammer. Dies were sometimes recut or altered for the purpose of changing the inscriptions but also to make repairs to cracks or flaws.

To strike a coin, the minter would put a hot flan (either just cast or reheated) on the lower die, place the upper die above it, and strike the upper die with a hammer, transferring both designs onto the softened metal. A single strike was usually sufficient, but minters sometimes used two strikes. Occasionally a coin will show evidence of multiple strikes in the form of a double or “ghost” image. This is the result of the coin shifting between strikes or the die vibrating out of position.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The flan was reasonably well centered on the dies during the strike, as evidenced by the degree of completeness of the edge beading. The beading on the obverse, however, demonstrates a considerable loss of articulation all around the proper left side, particularly at the bottom, where the edge detail is completely missing and the beading is distorted on either side of the missing area (fig. 24.5). On the reverse the beaded edge is complete, with some distortion and loss of detail concentrated in the bottom proper right quadrant (fig. 24.6).

Excess metal from the flan squeezed from between the dies to produce a flange along one edge (the proper left edge, when looking at the reverse face) (fig. 24.7).

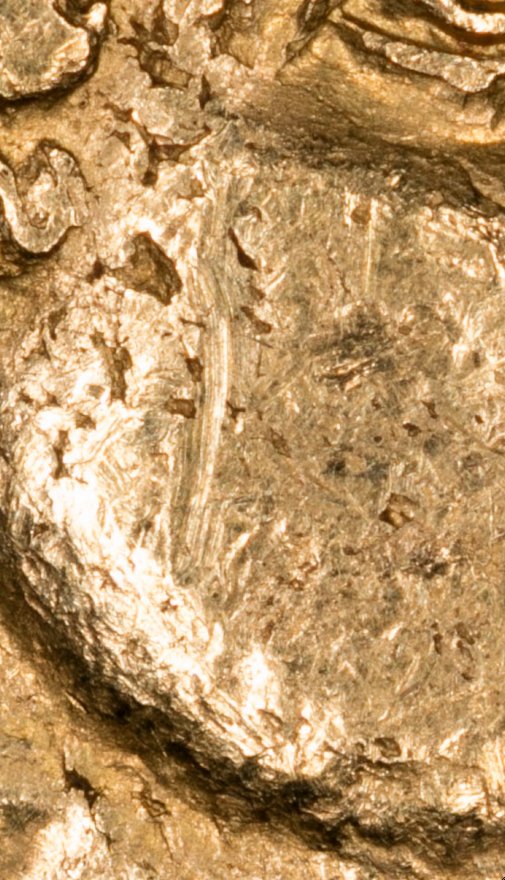

The dies were extremely well carved and produced an exquisite level of detail, notably in the horse trappings on the reverse (fig. 24.8), the pupil of Constantine’s eye (fig. 24.9), and the outside edge of his nose (fig. 24.10). Notwithstanding this fine workmanship, several flaws on the coin indicate that the dies had sustained damage during use. There are nicks and dents in a number of letters in the inscriptions on both obverse and reverse. On the obverse, at the end of the longer cord that hangs from the laurel wreath and extends forward along the emperor’s neck, the decorative spheres were not precisely rendered (fig. 24.11). On the reverse, there is a raised flaw between the V and the S in the inscription in the top proper right quadrant (fig. 24.12).

Pronounced radial strike marks are visible in the area of missing edge detail at the bottom center of the obverse (fig. 24.11). Elsewhere the crystalline appearance of the metal surface and the apparently large grain size hint at the thermal conditions of the flan just prior to striking.

Die Axis

The coin has a die axis of 11:00.

The earliest coins display considerable variation in the orientation of the obverse relative to the reverse, because the dies were unconnected and the reverse could be rotated freely in the punch. The die axes of very early coins seem to be essentially random. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, specific die axes appear to have been applied more consistently, with some mints generating coins on which both faces are upright and others producing coins with one face inverted (although misalignments occurred even when a definite orientation was intended). To assist the minters in achieving the correct alignment, dies may have been notched or had protruding elements; it was only late in the Roman period that dies began to be hinged, making the alignment regular.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

SMAN*, signifying Sacra Moneta (sacred money) Antioch. This mint mark appears on the reverse in high relief in the exergue. The mark was carved directly into the die and was impressed upon striking.

Numismatic Data

Dimensions

Top to bottom: 19.17 mm

Left to right: 18.85 mm

Top proper left to bottom proper right: 19.19 mm

Top proper right to bottom proper left: 19.46 mm

Thickness at widest point: 1.53 mm

Weight

4.48 g

Condition Summary

Two large semicircles of granular copper are visible on the obverse at the top edge of the coin, corresponding roughly to 10:00 and 2:00 (see fig. 24.13). There is an additional accretion of copper at the bottom edge, corresponding roughly to 6:00. Just above this accretion, a deep punch or gouge, rectangular in profile with a triangular depression, and accompanied by dark discoloration, intersects the cord extending from the wreath (fig. 24.11). Flecks of green material are present on the interior of this gouge. Taken together, these surface anomalies constitute strong evidence that the coin was at one time mounted into a pronged setting for a pendant made from a copper-rich alloy.

The surface of the coin displays prominent undulation. This distortion could have occurred during the insertion of the soft gold into the jewelry mount. The outside edge of the coin shows wear, possibly also due to contact with the mount.

There are a number of noticeable scratches on the obverse, the largest of which extends vertically along the side of the emperor’s cheek (fig. 24.14). Another scratch appears beneath the terminal letter of the inscription on the proper left side of the obverse (fig. 24.15). Other anomalies are visible on the reverse, most notably a long, broad strip of abrasion between the horse’s mouth and the nearby E in the inscription (fig. 24.16).

Several deep gouges can be seen on Constantine’s neck, particularly near the nape (fig. 24.17).

Pitting in the form of sharply angular voids is visible in the high-relief areas of the emperor’s temple and upper jaw (fig. 24.18). A number of factors could explain this surface texture. Flans were usually reheated prior to being struck; the texture might be a result of the semimolten state of the metal as it came into contact with the cold die. Alternatively, the texture might have been caused by surface depletion of copper during minting or burial. The pitting could also be a product of the injudicious use of a harsh agent, such as a strong acid or an electrochemical treatment, to remove burial deposits (although it is unlikely to have been caused by chemical cleaning of secondary corrosion that might have occurred subsequent to excavation).

A substance with a reddish coloration is present in many areas of low relief: at the front of the laurel wreath and in the back of the hair below the wreath on the obverse, and around the outline of the horse and rider as well as in the inscription on the reverse. This red coloration is presumably related to the copper compounds present in the alloy, but analysis would be required to conclusively identify this material.

Conservation History

There is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection.

Rachel C. Sabino