Let it make no difference to thee whether thou art cold or warm, if thou art doing thy duty; and whether thou art drowsy or satisfied with sleep; and whether ill-spoken of or praised; and whether dying or doing something else. For it is one of the acts of life, this act by which we die: it is sufficient then in this act also to do well what we have in hand.

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, book 6

Philosopher, ruler, general: Marcus Aurelius is a complex figure in the history of Rome, and one of the easiest to admire. This excerpt from his Meditations suggests how his studies of Stoic philosophy helped him shoulder the burdens of a challenging reign.

This coin represents Emperor Marcus Aurelius laureate and bearded. While the laurel wreath of victory had long ago become a standard iconography for the obverse portrait of Rome’s rulers, indicating their military role in protecting Rome, this beard was something new. It is true that the philhellene emperor Hadrian had inspired this tonsorial trend decades earlier, but the beards he and his successor Antoninus Pius sported were trim and elegant. This beard is one of a philosopher: unfussy, a bit scraggly, seemingly there more because he hadn’t bothered to shave than to convey rank or style. Indeed in the days when this coin was minted, Marcus Aurelius had more on his mind than an appointment with his barber.

The obverse inscription suggests the nature of that distraction: M[arcus Aurelius] Antoninus was not only Aug[ustus] but also Arm[eniacus] Parth[icus] Max[imus]—the great victor of Armenia and Parthia. Long and costly wars on the borders of Rome made it necessary for this quiet and introspective man to spend a large percentage of his years as ruler in the army camps rather than in his study, dying abroad in the military base of Vindobona (Vienna) on the Danube in A.D. 180.

An emperor’s name as indicated on his coinage can vary from issue to issue, but it usually clearly positions the ruler within the dynasty of the Caesars. Ever since Julius Caesar had adopted Octavian to succeed him, it was customary for the ruling monarch, if he had no adult sons to inherit the throne, to adopt a close male relative or friend who would become “Caesar” in turn. These adopted sons would inherit not only their new father’s material wealth but also his clients, his influence, and often his honors—in short, political power. They would consolidate the dynastic connections by marrying into the extended imperial family. Few of the emperors before Marcus Aurelius had had sons survive to adulthood. (The exceptions were Vespasian, of whose two sons Titus was a success and Domitian rather less so; and of course Marcus Aurelius himself, whose son Commodus would be the most notorious emperor since Nero.) Hadrian’s first choice for a successor predeceased him, and just months before his own death he adopted T. Aurelius Antoninus, soon to be known as Pius. Possibly due to anxiety over the succession after his experience of losing his first heir, Hadrian required Antoninus to adopt two heirs: Lucius Verus, the son of his first choice; and Marcus Aurelius, Antoninus’s nephew. Marcus’s original name (Marcus Annius Verus) was changed to Marcus Aelius Aurelius when he was adopted by his uncle in A.D. 138; on becoming emperor in A.D. 161 he added the name Antoninus in his honor, a name which appears regularly on his coinage, as we see here. Marcus’s marriage to Faustina the Younger, the daughter of Antoninus Pius and Faustina I (and his own first cousin), was arranged shortly after his adoption. It is noteworthy that although (or because) the dynasty was established through adoption and marriage, the whole imperial family was emphasized in the coinage of the Antonines, where the caesars (or coemperors) as well as the wives and mothers of the rulers (honored with the title Augusta) are very visible.

Marcus Aurelius was associated in rule as Caesar for the whole of Antoninus Pius’s reign, having been made consul designate as soon as he became Caesar, immediately upon his adoption by Antoninus in A.D. 138. The legitimacy of his succession was made clear from the start, not least on the provincial coinage: more than half of the provincial mints portrayed Marcus Aurelius as Caesar on coins during Antoninus’s reign. On the reverse of this coin, it is noted (TR P XXII) that Marcus Aurelius was already in the twenty-second year of his tribunician power (Tr[ibunicia] P[otestas]); he had been invested with that dignity since A.D. 147. This civilian power, which under the Republic had been held by the annually elected tribunes of the plebeians, had been in the hands of the emperors since Augustus’s “Second Settlement” of 23 B.C. Among other things, it gave the holder the right to veto any decision of the Senate. (It also, incidentally, marked the end of any real political power of the plebeians.) The tribunician power was granted at the accession of the new ruler, or sometimes earlier (as in this case, while Marcus Aurelius was still Caesar), and was normally renewed annually. This is obviously helpful for dating imperial coinage. The designation COS III (consul for the third time) is less helpful for dating, but tells us something about Marcus Aurelius’s governing style. Under the Republic two consuls had been elected annually; this was the highest elected office in Republican Rome and it included power over the army. Under the Roman Empire the office rapidly lost its independence, often being bestowed by the emperor, who frequently held one of the consulships himself. Marcus Aurelius’s predecessor Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), as a mark of modesty and respect for the Senate and the traditional ruling nobility of Rome, had accepted the consular power but rarely. M. Aurelius continued in that tradition; this coin marks his third and final consulship.

On his accession as emperor upon the death of Antoninus in A.D. 161, Marcus Aurelius immediately insisted that his coheir Lucius Verus be granted the exact same authority and honors as he had, rather than operating as second in command. The younger man seems to have been as devil-may-care as Marcus Aurelius was serious, but they had little time to worry about their differences of style. The same year that they became coemperors, the borders that had been pushed outward by Trajan and held firm by Hadrian and Antoninus started to give way. The Parthian king Vologases IV invaded Armenia, flouting his peace treaty with Rome. Lucius Verus was dispatched in A.D. 163 to take care of it. The campaign was a success, though Verus’s main contribution seems to have been that he was good at delegating: he spent the better part of three years in Antioch while his efficient generals imposed order on Parthia and Armenia. By A.D. 166 Verus and the soldiers had returned to Rome. They brought back a victory—and the plague.

The victory celebration posed a dilemma for Marcus Aurelius. As a coemperor who himself had insisted that all honors and powers be shared, he was pressed to accept the titles of Armeniacus and Parthicus along with Verus, though he felt they were not his; if he refused them, however, it might be taken as a slight to his august colleague. The salutations are therefore present on the obverse of this coin, though it may be remarked that the title Imperator (IMP IIII) is not on the obverse, and not used as the ruler’s praenomen, as he had the right to do. Instead, it is relegated to the reverse of the coin, among the other powers and honors conferred by the Senate. The effect is to suggest that Marcus Aurelius regarded power over the legions as a necessary adjunct to his job rather than as a part of his identity, and to acknowledge the Senate’s role in the conferral of that power.

The plague was another, more serious problem. Scholars are not sure what this plague was; it may have been smallpox, though measles or anthrax are both possibilities. Whatever it was, it was deadly. Between A.D. 165 and 180, an estimated five million people in Europe died of it. The repercussions for Marcus Aurelius were serious: it was already difficult enough to maintain the legions spread out over vast distances, policing Rome’s extensive borders. Trying to replace the soldiers who died of the disease proved difficult and costly. To make matters worse, another military challenge confronted Rome in A.D. 166. The Marcomanni, Goths who had maintained reasonably friendly relations with Rome for a century, suddenly took refuge from pressures farther east by crossing the Danube in large numbers. Once south of the border, they joined up with another restless Germanic tribe, the Quadi, and the nomadic Iranian-speaking Iazyges, and kept rolling southward, nearly to Aquileia at the head of the Adriatic Sea. In order to raise the legions necessary to face this threat to Italy itself, Marcus Aurelius accepted into the army even former slaves, gladiators, criminals, and resident barbarians, sold off treasures from the imperial vaults, and added another 5 percent base alloy to the already debased silver denarius. Production of gold coinage was limited, though this present aureus maintains its weight and purity. From A.D. 168 to 169 Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus were in Aquileia, until the immediate threat was averted; on the way home, Verus died, possibly of the plague. From that point on, Marcus Aurelius dropped Armeniacus and Parthicus from his titles; this coin was minted shortly before this grim event.

The Victory on the reverse is an appropriate symbol of the hard-won successes against the threats from the east, but it was also a traditional reverse type. Roman coinage was unusual for its variety of types; contemporaries even remarked on this fact. It was more conventional among ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern societies to maintain a constant, distinctive imagery on their coins in order to advertise continuity and encourage confidence in the currency. This psychologically astute approach was, however, also used at times by the Romans, such as when Trajan recalled silver denarii and reminted them at a purity 8 to 10 percent lower, but with types that recalled early imperial days and even the glory days of the Roman Republic. Because of the currency crisis of the Marcomannic Wars, Marcus Aurelius’s coinage sticks to reassuring and familiar reverse types. Though the aureus was not debased, there was no point drawing attention to changes elsewhere in the coinage by using novel types. This Victory type was even more popular under Marcus Aurelius’s successors, precisely when military victory became an ever more elusive goal for Rome.

Along with the reassuring Victory on the reverse, the obverse portrait would presumably further calm anxiety, invoking as it does the portraits of his immediate predecessors and the halcyon days of their reigns (see cat. 49, Denarius (Coin) Portraying Emperor Hadrian; cat. 50, Aureus (Coin) Portraying Emperor Hadrian; and cat. 53, Aureus (Coin) Portraying Emperor Antoninus Pius). However, although a family resemblance is stressed, this portrait begins to deviate a bit from earlier examples. Marcus Aurelius’s surviving sculpted portraits are divided into four types, dated primarily through numismatic evidence: style I, the earliest portraits during his youth, from circa 140, as on the reverse of an aureus with the head of Antoninus Pius (fig. 23.1); II, from circa 147, with a slight beard (see cat. 54, Aureus (Coin) Portraying Marcus Aurelius); III, from his accession to full power in 161, showing the emperor as more mature and with a longer philosopher’s beard, as in the influential Capitoline equestrian monument (fig. 23.2); and IV, dating roughly from the death of Lucius Verus, in which the beard is even longer and more scraggly and ends in twin curling locks. While early portraits of Marcus Aurelius (types I–II) stress more strongly the resemblance to Antoninus and to Lucius Verus, on this coin the ruler seems to be more comfortable asserting his individuality. One might expect that a philosopher’s beard might evoke some hesitation in the average Roman regarding the emperor’s martial qualities. However, the general message of confidence is subtly reinforced by the lack of armor: the heroic nudity suggested by the wisp of mantle on his left shoulder implies not ongoing struggle but near-divine control of the situation.

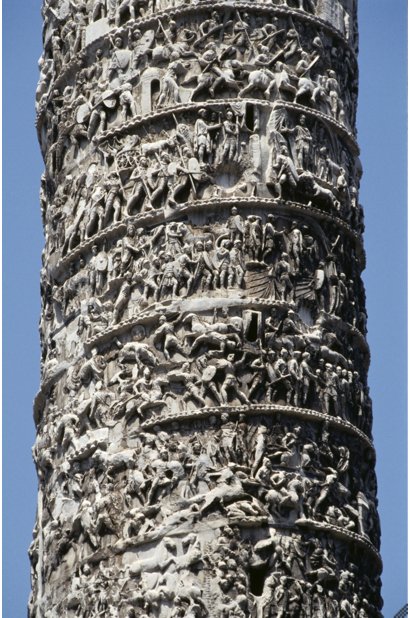

Between A.D. 169 and 174, after this coin was minted, Marcus Aurelius directed military affairs on the Danube, spending three whole years in the military base of Carnuntum (between Vienna and Bratislava), where he wrote part of his Meditations. The Danube border was brought under control by his efforts by A.D. 174; already in 172 a grateful Senate offered him the title Germanicus. The Iazyges took longer to deal with, causing trouble for Rome until the reign of Commodus, but Marcus Aurelius had settled them sufficiently by 175 to garner the title Sarmaticus as well. The column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome celebrates the castigation of the unruly tribes by Marcus and his son Commodus, by then assisting him in rule (see fig. 23.3 and fig. 23.4). The remainder of his years as emperor were spent protecting the borders while trying to maintain the benefits of the Roman state at home. Marcus Aurelius’s financial policy was marked by a reluctance to raise taxes at the expense of the average Roman citizen, by a determination to continue the alimentary institutions for the needy, and to support necessary building and capital developments. These preferences were made difficult to implement due to the expenses of the wars. At the same time, he could hardly rein in drastically the panem et circenses (bread and circuses) that the Roman population had come to expect. Traditional donatives to the army (unwise to omit) and congiaria (ceremonial largesse to the plebeian population) had already depleted the 675 million–denarius surplus that Antoninus Pius had left him with; numismatist Kenneth Harl reports that at their accession Aurelius and Verus “bestowed 30 million denarii to 150,000 urban plebeians, 43.5 million denarii to their 29 legions, and 76.6 million denarii to the Praetorian and Urban cohorts.” Even had they known of the imminent eruption of troubles on all frontiers at once, the rulers may not have curtailed their generosity, since in times of crisis the goodwill of the people and the army had to be assured—at any price.

To “do well what we have in hand”—a fitting motto for an emperor who ruled not as he wanted to, but as well as he could.

Theresa Gross-Diaz

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This coin is made of relatively pure gold; trace amounts of other elements are also present. It was struck with a free-floating reverse, resulting in a die axis of 5:00. A number of surface features indicate that the dies used to make the coin had become quite worn by the time of striking. The coin is in excellent condition, and its state of preservation suggests a relatively sheltered archaeological context. Prior to 2012, there are no written records of treatment of the object in either the conservation or the curatorial files.

Structure

Chemical Composition

Primary material: gold, Au

Secondary materials: copper, Cu (trace amounts); iron, Fe (trace amounts); silver, Ag (trace amounts)

Ancient coins were typically fabricated using gold, silver, electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver), and copper alloys. Bullion for the production of coins was obtained principally through mining operations and the collection of surface deposits. The Romans sourced silver and gold from the plentiful veins in Spain, but also used mines in Gaul, Dalmatia, Dacia (in the Carpathian mountains), Britain, the Near East, and Africa. Ores were not the only source of bullion, however: war booty, tariffs paid by other states, stored wealth in the state treasury, and existing coinage could all be melted down and reminted.

The purity of the metal used for minting was highly regulated and carefully overseen. Throughout the Greek and Roman periods, gold coins were particularly refined, usually containing more than 95 percent pure gold. Silver coins had a somewhat smaller but nonetheless impressive degree of purity. For most of Roman history, the purity of the coinage seldom wavered. By the late Imperial period, silver coins had been significantly debased, containing as little as 2.5 percent silver. Even the debasement of coins, however, was closely monitored.

Determining the precise composition of ancient coins is difficult. For a variety of reasons, the surface of a coin is unlikely to be representative of the composition of its interior. While qualitative information can be obtained using minimally invasive methods that analyze the surface of a coin, quantitative results require abrading or removing the surface in order to analyze material closer to the heart metal at the center, an approach that is generally unacceptable in a museum context.

Fabrication

Method

The coin was struck by hand.

Hand striking a coin is performed in three distinct operations: the creation of a flan (or blank), which is the plain lump or disk of metal that receives the image; the creation of a die, which is the stamp used to impress an image on the flan; and the striking of the coin itself.

In order to create flans of a consistent weight and composition, it was first necessary to smelt and refine the bullion. Surviving coins attest to the fact that Roman metalsmiths possessed sufficient knowledge and skill to obtain a high degree of purity and to adjust the alloys to precise specifications. The refined, molten metal was poured into open or two-part clay molds. Gold and silver coins may have been cast in individual molds, but coins could also be cast en chapelet, using open or closed molds connected by channels.

Metal dies were used to impress an image onto the flan. Few ancient official dies survive today: when a die reached the end of its useful life, because of wear or the discontinuation of the design, it was typically destroyed to prevent unauthorized use. Nonetheless, enough evidence remains to conclude that the dies were usually made of a bronze alloy containing a relatively high percentage of tin that could be made sufficiently hard to strike even bronze coins. The vast majority of images on ancient coins are in relief. This means that the images on the dies were carved in intaglio, as a negative image below the metal surface of the die, similar to the way stone seals were cut or engraved, giving a mirror image of what would be displayed on the coin. Also as with stone engraving, the tools were made of iron and would have included punches, burins, chisels, and drills.

Two dies were usually employed in striking a coin. The obverse (lower) die was fixed in position, usually into an anvil or a block of wood. The reverse (upper) die was loose; the image could be engraved directly into the base of a cylindrical or pyramidal piece of metal or, more commonly, into a bronze disk that was fitted into an iron punch or collar. The obverse die was used to stamp the more important side of the coin, which often displayed deeper or more intricate images. Its protected position in the anvil gave a better chance of a clean impression.

The life-span of a die depended on a number of factors: the composition of the metal, the size of the die, the depth of the relief, and the number of coins made. The obverse die wore down less quickly than the reverse die, which was struck repeatedly with a hammer. Dies were sometimes recut or altered for the purpose of changing the inscriptions but also to make repairs to cracks or flaws.

To strike a coin, the minter would put a hot flan (either just cast or reheated) on the lower die, place the upper die above it, and strike the upper die with a hammer, transferring both designs onto the softened metal. A single strike was usually sufficient, but minters sometimes used two strikes. Occasionally a coin will show evidence of multiple strikes in the form of a double or “ghost” image. This is the result of the coin shifting between strikes or the die vibrating out of position.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The strike is slightly off-center on both the obverse and the reverse, rendering the beaded edge incomplete on both sides. On the obverse the beading is missing on the proper right side. The extant beading has a crimped appearance in the top proper left quadrant and trails off into a serpentine pattern in the bottom proper right quadrant (fig. 23.5). On the reverse the beaded edge is only visible in the top proper right quadrant. Elsewhere around the perimeter, slight undulations are visible, as well as faint suggestions of a serpentine pattern.

Radial strike marks can be seen within the surface on both faces of the coin, emanating from the center. These marks are particularly noticeable around the inscription on the proper left side of the obverse (fig. 23.6) and around the inscription at the top of the reverse. Overall the texture on the reverse is quite dendritic (treelike) in appearance, which could be an indicator of the microstructure of the alloy or of the thermal conditions of the flan during striking.

Minor casting flaws on both sides of the coin suggest that at the time of minting the dies were quite worn. On the obverse, a raised lump is present just below the front edge of the bust, and the tip of the bust itself is flawed, appearing not as a clearly defined point but as a series of irregular, granular accretions with a significant void present along the top edge (fig. 23.7). Another raised lump appears in the circular field between the beard and the A in the inscription in the bottom proper left quadrant (fig. 23.8). In that same quadrant, there is a flaw at the terminal point of the M in the inscription. A third lump is visible beneath the S in the inscription in the top proper right quadrant. The lack of a specific point of attachment between the back of the head and the ribbon on the emperor’s laurel wreath is further evidence of loss of detail in the die (fig. 23.9). Similarly, the front portion of the emperor’s mantle does not appear to be fully articulated (fig. 23.7).

On the reverse, the loss of detail in the feet and ankles of the figure is particularly noticeable in the lack of a connection between the top of the limb and the bottom of the garment (fig. 23.10). The wings on the figure have an irregular texture, and there is a lack of articulation of the laurel wreath in the figure’s proper right hand (fig. 23.11). There are also nicks and dents in a number of letters in the inscription.

Die Axis

The coin has a die axis of 5:00.

The earliest coins display considerable variation in the orientation of the obverse relative to the reverse, because the dies were unconnected and the reverse could be rotated freely in the punch. The die axes of very early coins seem to be essentially random. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, specific die axes appear to have been applied more consistently, with some mints generating coins on which both faces are upright and others producing coins with one face inverted (although misalignments occurred even when a definite orientation was intended). To assist the minters in achieving the correct alignment, dies may have been notched or had protruding elements; it was only late in the Roman period that dies began to be hinged, making the alignment regular.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No mint mark is present on this coin.

Numismatic Data

Dimensions

Top to bottom: 20.13 mm

Left to right: 19.16 mm

Top proper left to bottom proper right: 19.68 mm

Top proper right to bottom proper left: 19.71 mm

Thickness at widest point: 2.76 mm

Weight

7.26 g

Condition Summary

The coin is in exceptional condition, suggesting that it was not widely circulated or that it remained undisturbed in a well-protected burial context in antiquity, such as a coin hoard. It is relatively flat with only minor undulations, and no scratches mar the surface. Despite the very high relief on the obverse, it shows little wear. What wear does exist is concentrated around the laurel leaves. Considerably more wear can be seen on the high points of the reverse. On both sides of the coin, isolated dark areas appear within the strike marks, and slightly dark halos are visible around many of the letters (see fig. 23.12). These discolorations are most likely related to the preferential corrosion of the less-noble copper. Microscopic examination reveals a remnant of red paint once used to mark the object with an accession number on the proper right side of the reverse.

Conservation History

There is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection before 2012. In that year, in preparation for catalogue photography, an accession number painted in red on the reverse was removed using aqueous cleaning methods. In 2015, the object was cleaned again; dark residues and accretions present within several of the closed letters of the inscriptions (i.e., O, P, R) on both the obverse and the reverse were removed.

Rachel C. Sabino