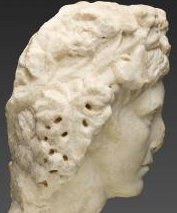

Fashioned in marble from Aphrodisias, this life-size portrait head depicts an unidentified male (fig. 4.35). The subject has a youthful, unlined face that tapers toward the chin and a bow-shaped mouth. The deep-set eyes, which gaze upward and to the figure’s left, have lightly incised irises and bean-shaped pupils composed of three shallow circles (fig. 8.40). The eyelids are noticeably puffy, with the lower lids somewhat swollen. Over the subject’s forehead are thick, wavy locks of hair parted slightly off center. The upper part of the head is encircled with a wreath of ivy, vine leaves, and berries, from which a large cluster of grapes hangs on the proper right side, almost entirely obscuring the ear (fig. 4.22). This type of wreath is often associated with Dionysos, the Greek god of wine, theater, revelry, and agricultural fertility. Known to the Romans as Bacchus, he was also identified with the native Italian god Liber or Liber Pater.

The back of the head is generally flat and angled slightly forward (fig. 4.20). The surface is [glossary:keyed] and includes a large circular socket just to the right of center, indicating that the head was not carved from a single block of marble but rather was once pieced together from two separately worked segments. At the nape of the neck is a horizontal ledge that would have provided additional support for the second piece; below this ledge on the proper right side is a triangular projection of stone (fig. 4.23). The preservation of this mass of material at the back, as well as the fact that the neck does not end in a tenon, seems to rule out the possibility that the portrait was carved for insertion into a larger work. Rather, it was likely part of a [glossary:herm], a bust, or a full-length statue.

Anomalies of form and proportion reveal that this head was altered from its original appearance, the subject of which is unknown. The narrow, triangular face, which is disproportionately small in relation to the thick neck and the sizable wreath, suggests that the face was reworked at some point, thereby reducing its volume, whereas the neck and the wreath were preserved from the head’s initial phase. Furthermore, the rough, unfinished surface on the sides of the face and the underside of the jaw might indicate that the earlier subject wore a beard that was incompletely removed. Likewise, short, vertical strokes carved on the proper left upper lip appear to reflect the deepest cuts of a prior moustache that was also intentionally eliminated (fig. 4.34).

A Portrait of Emperor Gallienus as Bacchus?

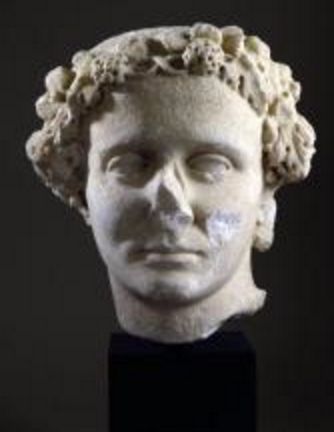

When this head entered the Art Institute’s collection, it was identified as a portrait of the emperor Gallienus (coruler with his father, Valerian, A.D. 253–60; sole ruler, A.D. 260–68). This identification appears to have been based on the general stylistic similarities between this figure’s facial features and those of the “type 1” portraits of Gallienus (as they have been categorized by modern scholars), which were produced during his years as coruler. Although there are variations among the examples of this type, its basic features include a triangular face that tapers toward the chin, distinct locks of hair arranged over the forehead, wide eyes that gaze upward and to the side, and a small, rounded mouth, as exemplified by a portrait in Berlin (fig. 4.28). The type also includes a closely cropped, plastically rendered beard that extends from the underside of the chin onto the neck, as well as a subtle, neatly trimmed moustache, features that likewise appear in his later portrait types.

The portraits of Gallienus were rendered in a classicizing style that distinguished him from the “soldier emperors” who immediately preceded him in the second quarter of the third century, with their cropped hair, short beards, and hardened facial expressions. This style also connected him to earlier, lauded predecessors, such as Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14) and Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–38), who were similarly represented in idealized likenesses. A noted philhellene, Gallienus is thought to have brought about a renewed interest in classicism, which has been described by some modern scholars as the “Gallienic renaissance.”

Recently, numerous portraits of Gallienus have been identified as works that were recarved from existing portraits of other individuals, including the portrait in Berlin illustrated above (see fig. 4.28). According to Marina Prusac, there are more recarved portraits of Gallienus than any other third-century emperor. The Romans had a long history of reworking earlier stone likenesses for a variety of reasons. But in the third century—a period plagued by political and economic crises—this practice occurred on an even greater scale. In fact, several portraits of Gallienus seem to have been created from portraits of Julio-Claudian emperors and Hadrian, perhaps suggesting that he wished to associate himself with their positive reputations. Theoretically, the Chicago head could have been a portrait of one of these earlier and much admired rulers.

Despite its stylistic similarities to type 1 portraits of Gallienus, the Chicago head exhibits some significant differences. Especially noteworthy is the complete absence of facial hair; Gallienus is typically depicted with a shallow beard and a wispy moustache, so the erasure of these features suggests that in its present form, the subject is someone other than the emperor.

The portrait’s Bacchic wreath of ivy has led to the subject’s further identification as “the emperor Gallienus as Dionysos.” If this were so, the head would likely have belonged to a [glossary:theomorphic] portrait that assimilated Gallienus to Dionysos/Bacchus, equating the ruler’s positive qualities with the virtues of the god. However, representations of the emperor in the guise of Bacchus are rare.

The infrequent choice of Bacchus for theomorphic imperial portraits might have been due to the Romans’ emphasis on the value of moderation, which contrasted sharply with the god’s associations with revelry, excess, and luxury. Political and moral factors, including early opposition to the practice of Bacchic mystery cults in Rome and Italy, as well as concerns about the identification of Hellenistic rulers with the god, contributed to the problematic nature of depictions of Bacchus in imperial art. However, images of the god and his retinue had enjoyed popularity since the late republican period in Roman domestic contexts, where they evoked the pleasures of life and helped to create an ambience of Greek culture and leisure ([glossary:otium]). Over the course of the imperial period, the imagery of Bacchus became appropriate for use in official images to broadly signify such concepts as happiness, abundance, fertility, and the good life.

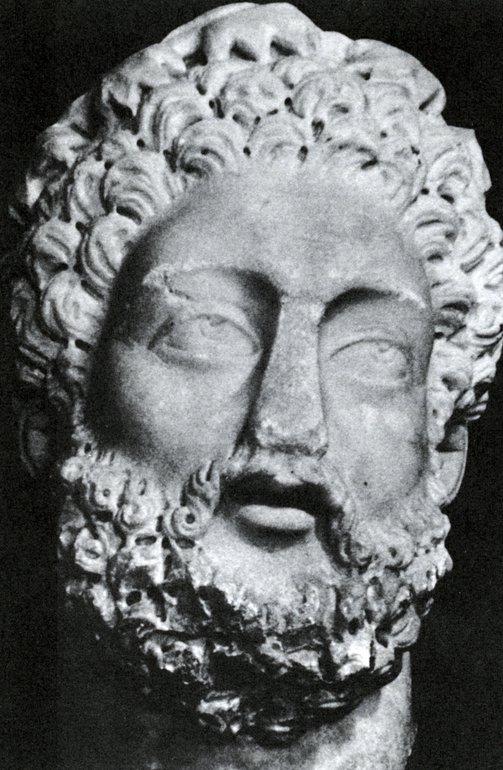

At least one portrait of an emperor wearing a Bacchic wreath is known: a portrait head of the emperor Commodus (r. A.D. 177–92) crowned with an ivy wreath, found in front of the Great Gate at Tralles in Asia Minor (modern-day Aydın, Turkey) (fig. 4.21). Cornelius C. Vermeule interpreted this head as an image of Commodus as Neos Dionysos (New Dionysos). Such “New God” titles, which were initially used for Hellenistic rulers, were employed primarily in the eastern Greek-speaking parts of the empire as a means of celebrating members of the imperial family. Epigraphic evidence indicates that Commodus, Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), and Hadrian were awarded the title of Neos Dionysos by their subjects. However, it is unclear whether they were honored as such with portraits that incorporated Bacchic attributes.

Emperors were more frequently shown in the guise of other major gods, including Mars, the god of war and ancestor of the Roman people, and Jupiter, the supreme god of the pantheon. An example of the latter is seen in a cameo in the Art Institute’s collection that represents the emperor Claudius (r. A.D. 41–54) with several of the god’s characteristic attributes, including the thunderbolt, the scepter, the aegis (goatskin), and the eagle (fig. 4.32; see cat. 138).

For these reasons, it is unlikely that the Chicago portrait portrays the emperor Gallienus in the guise of Bacchus. Instead, it probably depicts a private man wearing a Bacchic wreath, since portraits of private individuals often emulated the physiognomy, hairstyle, and facial expression of imperial images. This phenomenon, known as the Zeitgesicht (“period-face”), has been attributed in part to the desire of private individuals to follow the ideologies and styles of the emperor. It might also be due to the practices of sculptural workshops, as portrait sculptors might have simultaneously produced both imperial and private likenesses, resulting in the use of period-specific stylistic features in both types of portraits. Therefore, a date in the mid-third century A.D. seems likely for the Chicago head.

The Bacchic Wreath in Private Roman Portraits

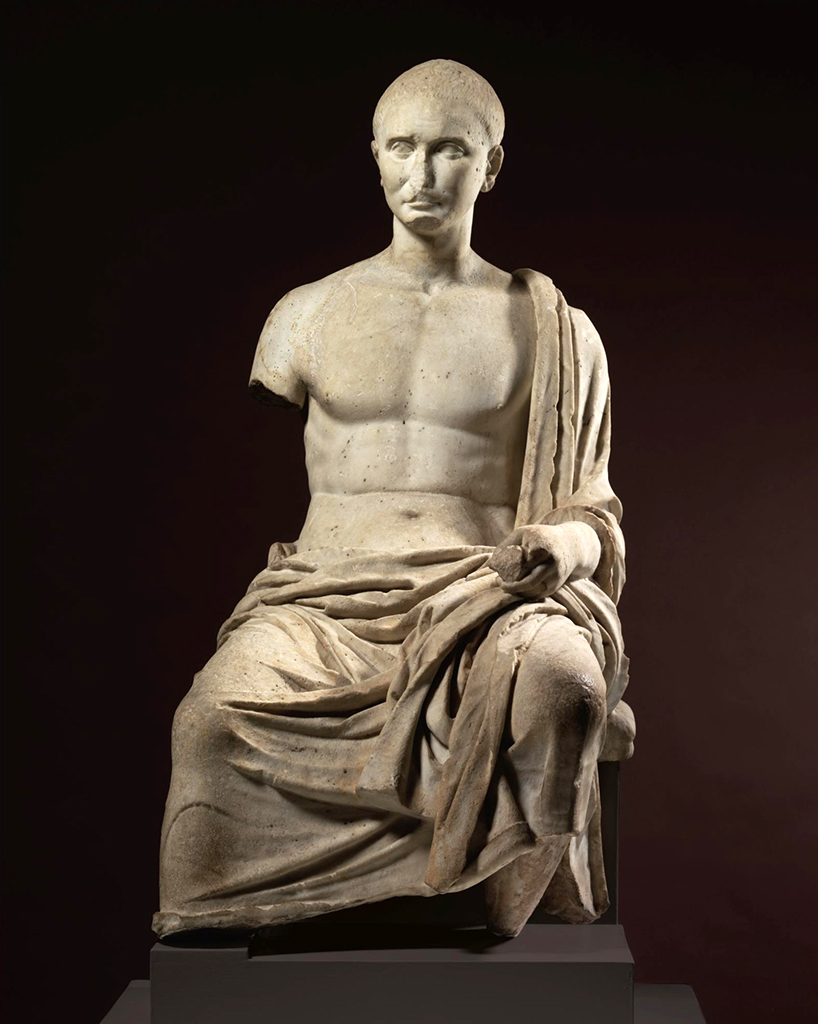

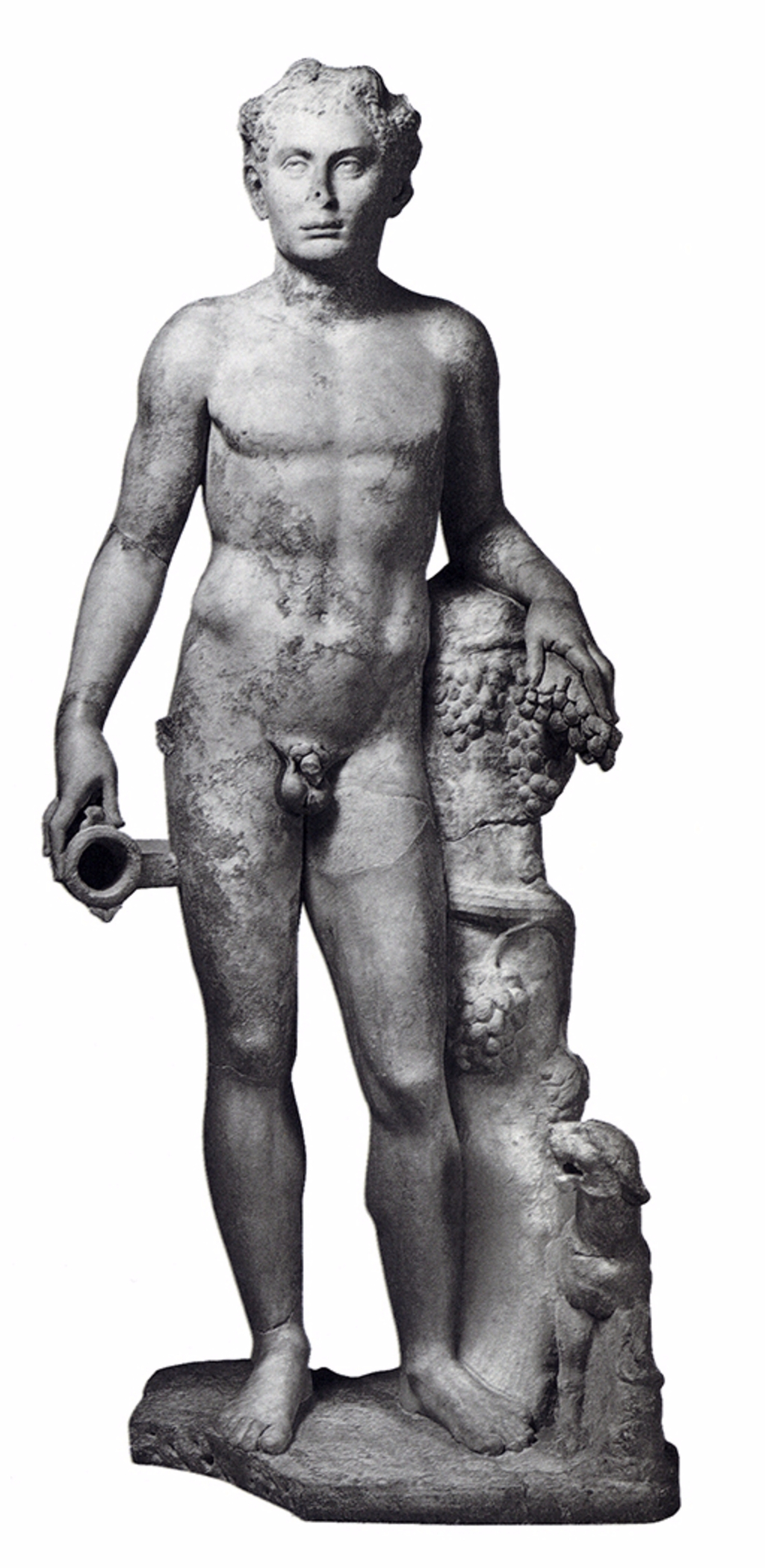

A number of private portraits in the round and on reliefs depict individuals crowned with a Bacchic wreath of ivy and, in some cases, with additional attributes associated with the god, including the [glossary:nebris], grape clusters, and the [glossary:kantharos] or other type of drinking vessel, as well as animals that were sacred to him, such as the panther and the goat. In addition, where the subject’s body is shown it frequently resembles that of the god in his youthful state: fully or partially nude and featuring a soft physique with subtle hints of muscular definition. There are several reasons these attributes—particularly the wreath—and this body type could have been chosen.

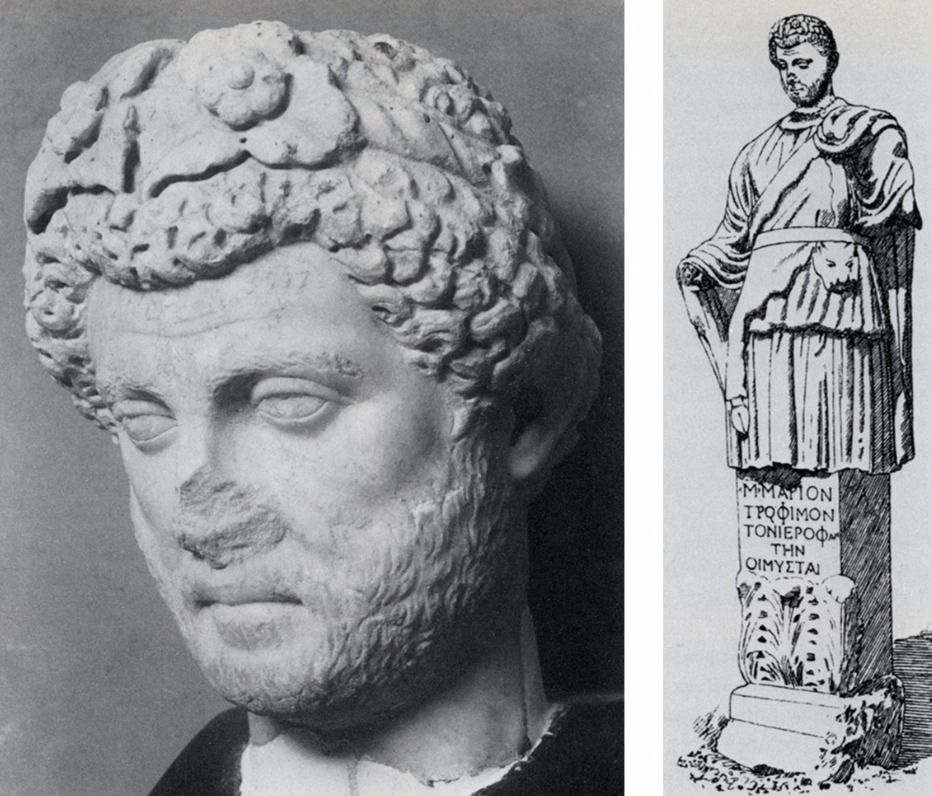

First, private portraits incorporating Bacchic attributes might be theomorphic images assimilating the subject to the god. Numerous examples depict boys and young men, perhaps due to their similarities in terms of youthful physical appearance. However, examples portraying mature men are also known. Some of these portraits of individuals in Bacchus’s guise are known from funerary contexts, no doubt due to the god’s association not only with the pleasures of life but also with the transcendence of boundaries between death and rebirth. For example, in a portrait of a youth found in the necropolis of Gytheion, Greece, the subject’s assimilation to Bacchus is indicated by his fully nude body and the incorporation of several of the god’s attributes, namely a wreath of ivy and berries, a nebris, a kantharos, bunches of grapes, and a panther (fig. 4.18).

Second, a wreathed image might represent a religious official or devotee of the god. For example, a sculpture in Cedar Rapids of a mature male wearing a wreath of ivy leaves and berries is thought to portray a priest of Bacchus (fig. 4.26). A more explicit reference to the subject’s religious occupation and dedication to the god is apparent in a male portrait herm in Athens, which was found in the so-called Hall of the Mystae (initiates or priests) of Dionysos Trieterikos on the island of Melos (modern-day Milos) (fig. 4.33). Dated to the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93), the portrait head depicts a mature male with a closely cropped beard, a coiffure of thick curls, and a wreath comprising enormous ivy leaves and berries. The herm body, now missing but known from a drawing, was clothed in a [glossary:chiton], a mantle, and a nebris in the form of a panther skin. An inscription on the base identifies the man as a hierophant—a priest or interpreter of sacred religious mysteries—thereby explaining the purpose of his divine costume.

Finally, wreathed portraits sometimes depicted poets. As one of the dramatic arts, poetry fell under the purview of Bacchus, who was thought to inspire poetic verses. Wreaths had long been awarded to poets who were successful in poetry contests, which had their origins in the Panhellenic Games and other local festivals of the Greek world. Known as agones, these formal competitions were typically held in honor of a god or local hero and took place among various athletic, equestrian, and musical events. New games in the Greek style were founded in the Hellenistic and Roman imperial periods, with some festivals surviving into late antiquity, suggesting the significant role that such competitions played in Roman cultural life.

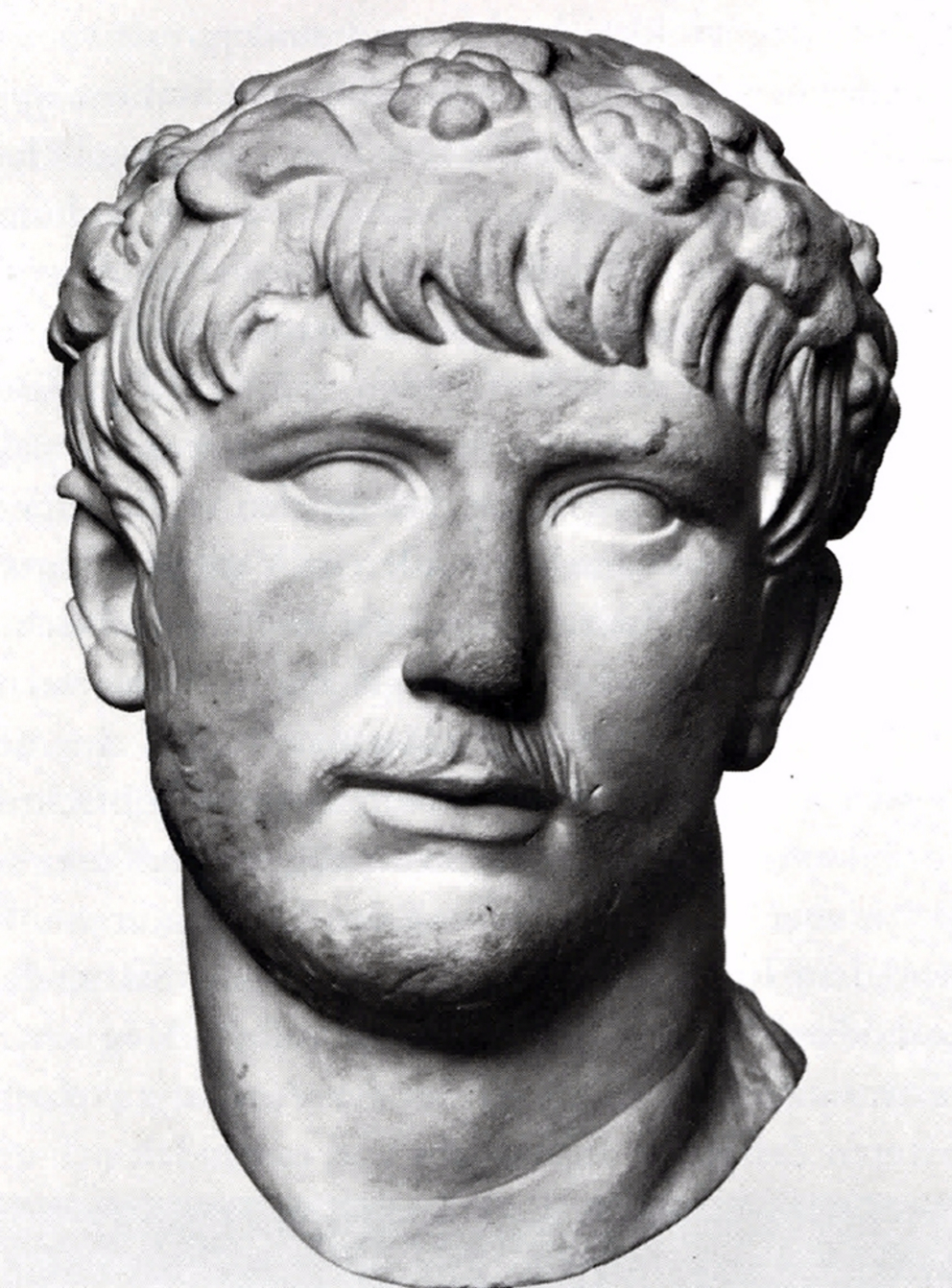

According to the Roman lyric poet Horace, a crown of ivy was “the reward of poetic brows,” which connected a successful poet to the gods on high. In addition, Martial, another Roman poet, identified the ivy wreath as the symbol of his profession, its “civic crown.” Some portraits of poets incorporate an ivy wreath. For example, in a portrait head in Munich that probably depicts a poet, the subject wears a wreath of ivy and berries over a coiffure of forward-combed locks, along with a closely cropped beard and moustache (fig. 4.29). While some portraits might have been created during the subject’s lifetime, perhaps to honor a poet for his victories in competitions or his successful career, others might have served to commemorate a deceased poet.

Conclusion

Portrait Head of a Man was undoubtedly recarved from an earlier sculpture of a bearded man wearing an elaborate Bacchic wreath. Although the head was previously identified as a portrait of the emperor Gallienus in the guise of Bacchus, this is unlikely given that the facial features bear only general stylistic similarities to those seen in images of the emperor, and—more important—that his characteristic facial hair is notably absent. The work probably depicts a private individual, who was most likely represented with this wreath for one of several reasons: to assimilate him to the god in the funerary sphere, to honor his priestly office or religious devotion to the god, or to celebrate his successes as a poet.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This intriguing portrait was carved from a single block of fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Aphrodisian (fig. 4.5). The object is the front portion of a fragment from a larger sculpture, the original format of which is unclear. The front of the portrait was joined to the now-missing back portion by means of a large, circular socket and tenon. Why such small pieces would have been joined in this way during a period of relative abundance in the eastern quarries is also unknown. Adding further to the mystery are indications of incomplete or interrupted recarving along the jawline, where original facial hair has been partially removed. Other aspects of the portrait, such as the depth of the eyes and lips, as well as the thickness of the neck relative to the face, provide additional clues that the sculpture was reworked. The sculptor’s deft handling of the drill is manifest in the rendering of the vegetal elements of the garland. The presence of rootlets on the surface provides evidence of the burial environment; the root marks are confined primarily to the verso of the object, although close examination reveals that the root incrustation on the front was once heavier. No traces of [glossary:polychromy] or gilding have been detected. The stone exhibits a degree of decohesion attributable to past environmental exposure, and the fragility of the matrix has contributed to an overall softening and loss of detail throughout. Only one recent treatment has been documented during the object’s time in the museum’s collection.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is a cool, bright white with a blue-gray tone. Calcite crystals are visible to the naked eye (fig. 10.43). Prominent, dark-brown veins run through the face diagonally from the top proper left to the bottom proper right. These veins are particularly visible when the object is examined under ultraviolet radiation, especially around the nose, the proper right eye, and the neck beneath the chin (fig. 4.2).

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (present)

Petrographic Description

A triangular sample roughly 2.5 cm high by 1.5 cm wide was removed from an area of incipient [glossary:cleavage] on the verso, in the [glossary:keyed] area behind a projection at the outside edge of the garland on the proper left side. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 2.08 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: [glossary:sutured]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some inter- and intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 4.11

Provenance

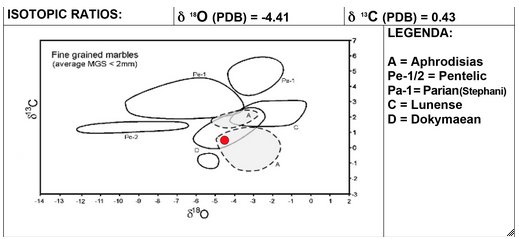

Marble type: Aphrodisian (marmor aphrodisiense)

Quarry site: Aphrodisias, near modern-day Geyre, Aydın Province, Turkey

The determination of the marble as Aphrodisian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 4.10

Fabrication

Method

The object was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

The head was fashioned in two parts that were joined by means of a socket and tenon. The circular shape of the socket, while not common, is not exceptional either. The interface between the front and back sections is angled slightly forward, which supplemented the tenon in alleviating the shear forces acting on the join. The projecting ledge at the nape of the neck gave the join additional support (fig. 15.45). The join face was sharply keyed in order to provide tooth for an adhesive; however, no traces of the adhesive remain in the keyed area.

Aspects of the format, construction, and carving are deeply perplexing, and attempts to determine the original appearance and function of this portrait have proved unsatisfactory. The object is definitely a fragment, but the nature of the sculpture to which it originally belonged remains a mystery. The absence of any hallmark diagnostic feature common to portrait busts or freestanding sculpture, such as a tenon worked for insertion, together with the pieced assembly at the back of the head, makes it difficult to propose a theory. The triangular projection of stone on the proper right side of the verso, which bears traces of early-stage stoneworking, and the flat profile of the projecting ledge at the nape of the neck are equally confounding.

Certain aspects of the portrait suggest that it may have been recarved, although there is some question as to whether the secondary portrait is complete. The carving of the back of the garland on the proper right side is extremely rough and unfinished (fig. 4.9). Elements of the face appear to be at odds with the components surrounding it. In many recut portraits that feature wreaths or garlands, the foliage could not be altered because of the extent of the undercutting or drilling, often resulting in a face that looks disproportionate to the headdress. While the relationship between the garland and the face of this portrait head does not present a glaring discordance, the neck and the underside of the jaw seem excessively thick relative to the delicate proportions of the cheeks and chin. Furthermore, the chin itself, when viewed in profile, appears somewhat recessed compared to the nose and forehead (fig. 15.46). The eyes, while spaced in a proper ratio with respect to the rest of the face, look overly large (fig. 10.42) and also somewhat sunken, particularly when viewed from the side. In addition, the features seem to be pulled to the center of the face, and the inner corners of the eyes appear unusually deep.

The part in the hair is off-center in relation to the eyes and nose. The corners of the lips look far too deep when compared to the line carved between them (fig. 4.6). The proper right ear seems unfinished, and the proper left ear is missing entirely, perhaps a casualty of recutting or maybe just obscured by the overhanging garland. Above the lip on the proper left side, short vertical lines may be the vestiges of the deepest cuts of an original moustache (fig. 4.13).

The presence of truncated facial hair at the base of the jaw and on the sides of the face offers the most compelling evidence that the youthful face seen at present was chiseled from a once-hirsute visage (see fig. 4.16). This rough, unfinished surface extends all the way along the underside of the jaw and is especially prominent in front of the ear on the proper left side. These anomalies suggest a modification that has not been fully realized.

When the object is examined under ultraviolet radiation, a deeper violet coloration is visible at the sides of the face and along the jaw as well as around the eyes and mouth, corroborating the theory that these are areas of more recent carving (fig. 15.47).

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Owing to the weathered condition of the stone, few toolmarks remain on the surface.

The keying on the flat surface of the verso was done with single sharp blows of a point chisel. In this same area, traces of a rasp or scraper are also visible (fig. 4.14).

Extensive use was made of the drill. In the garland in particular, drills of varying diameters (ranging from 3.82 to 7.28 mm) were employed in a number of ways, not merely to create circular perforations on the surface but also to render complex shapes. The sculptor’s handling of the tool to describe the grapes on the proper right side is especially impressive. The artist used different drill diameters to build up layers of depth, inserting deeper holes within shallower lines or perforating the surface at intervals in a circle in order to raise up a mound of stone (fig. 4.8). Frequently two holes were drilled next to one another to create a larger opening or longer perforation (fig. 8.39). The same technique was used to create long, lozenge-shaped perforations (fig. 4.12).

The running drill method was used to separate the edges of the face from the adjacent masses of the garland and hair, as evidenced by the circular depressions at the ends of the lines (fig. 4.15).

The irises were incised with the edge of a flat chisel held at an angle to the stone, and the bean-shaped pupils were carved with a roundel. A flat chisel was also used to create the line between the lips and to demarcate the triangular corners of the mouth.

On the projection of stone at the lower proper right corner of the verso, despite the heavily weathered surface, traces of a flat chisel are still visible (fig. 15.48).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The object is complete with no extant fragments; however, there are notable losses to the end of the nose and to several of the larger elements in the garland. The damage to the nose extends halfway up the nasal ridge and includes the tip as well as the flesh encircling the nostrils.

The crystal matrix appears to have been somewhat compromised either by an outdoor exposure in antiquity or by the burial environment, with the result that in some areas the stone is actively exfoliating. A zone encompassing the forehead, the eyebrows, the nose, and the proper left side of the face exhibits particularly severe grain loss (see fig. 4.7). The net effect of this deterioration is an overall softening and loss of detail throughout.

A large chip with associated orange staining is visible on the proper left side of the chin.

Abundant traces of root marks from the burial environment survive, although they are confined to the top; the verso; the garland, especially on a broken edge on the proper left side; and the outermost margins of the face. The root marks on the sides and verso—particularly within the circular cavity—are longer and more fibrous, appearing as a genuine network of vegetal growth (see fig. 10.44). On the front of the sculpture, the root marks look more like scattered dots than fibers; it is likely that they were at one point mitigated, likely by mechanical means.

Various superficial anomalies resulting from the burial environment are apparent. Orange staining, possibly iron oxide, is present on the projection of stone at the lower proper right corner of the verso. Staining of a lighter orange hue is visible on the top of the object and within the negative spaces of the garland. The heaviest of the orange staining, manifest as a discrete, opaque coating, is present on the surface below the ledge of stone at the nape of the neck (fig. 4.17). On the verso, a large portion of the keyed area to the proper left of the circular cavity has a dark-gray coloration. The upper part of this surface bears a waxy, yellow patina. The face shows a slightly mottled, yellow tone overall.

Conservation History

In 2012, in preparation for its reinstallation in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art, the object was given a general surface cleaning using high-pressure steam. Unsightly spots of blanching and scratches were then lightly tinted so as to harmonize the overall tone of the marble.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini