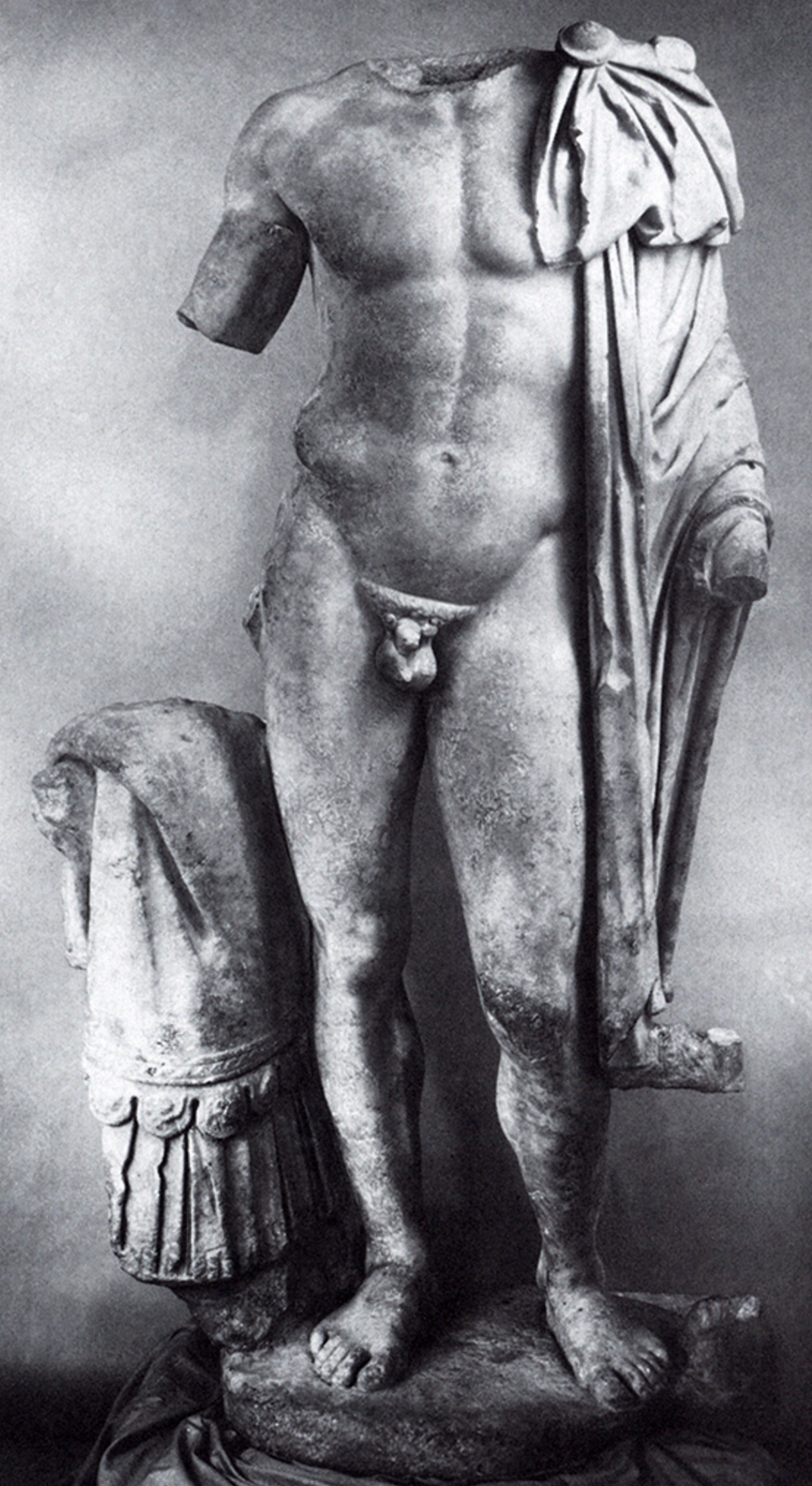

The subject of this over-life-size statue of a nearly nude male figure is unidentified. Although it is preserved in a fragmentary state, its large scale and the pronounced musculature of its broad torso convey a sense of monumentality. Made of Parian marble, it is missing its head and most of its appendages, including both arms, the proper right knee and lower leg, nearly the entire proper left leg (the thigh is a restoration), and the genitalia. At the proper right side is the upper half of an integral statuary support. Given that there are no holes for dowels, pins, or tenons, particularly in the neck or arms, it is likely that the work was carved in the round from a single block of marble (fig. 14.1).

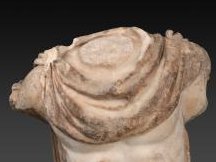

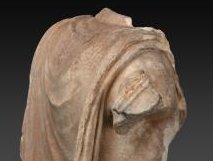

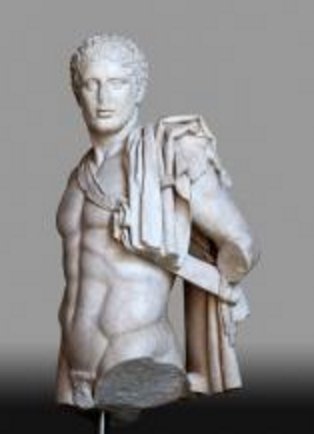

Although predominantly nude, the figure wears a [glossary:chlamys]. It is pinned at the proper right shoulder with a fragmentary round [glossary:fibula] (fig. 14.2). At the back, the folds of the chlamys cascade in shallow ridges, fully covering the back, buttocks, and thighs, except for an area of loss on the lower proper left side (fig. 14.3). Traces of a scabbard remain on the outside of the proper right shoulder (fig. 14.4), suggesting that a sheathed sword was once cradled in the figure’s right arm with its tip oriented toward the body (the so-called parade grip). The fragmentary statuary support adjacent to the proper right leg takes the form of a tree trunk covered by a leather [glossary:cuirass]. At the side and back of the support are long, flat leather straps, which were attached to the armholes of the vestlike garment worn immediately beneath the armor; here the straps of only one armhole are represented (fig. 14.5). In its complete state, this cuirass support would likely have resembled that seen in an over-life-size statue of the emperor Antoninus Pius in Rome (fig. 14.6).

The marble bears traces of iron staining from its burial context, particularly on the drape of the chlamys across the chest and on the support. The staining gives these features the appearance of being enlivened with pigment, as was probably the case when it was created.

Heroic Nudity in Roman Portraiture

The Romans held complex views about nudity and its appropriateness in different contexts. On the one hand, no respectable person appeared in public in the nude, except in specific settings, such as the baths. On the other hand, nudity was frequently the preserve of gods and heroes in art and literature. Their idealized, beautiful bodies demonstrated their extraordinary and supernatural character, a concept described broadly by modern scholars as [glossary:heroic nudity].

Both imperial and private individuals—primarily men—were also portrayed nude. Their nudity is considered by modern scholars to be a type of costume. The ancient viewer would have understood it as an artificial convention that, due to its association with the appearance of gods and heroes, could visually convey messages about the subject’s virtues and admirable qualities, “his youthful vigour, his physical courage, his dynamic personality, his charismatic leadership.” The bodies of nude portraits were often based on earlier Greek statues of gods, usually Hermes (equivalent to the Roman Mercury), Zeus (equivalent to the Roman Jupiter), and Ares (equivalent to the Roman Mars), or heroes, such as Diomedes. Thus, the nude statuary body was clearly distinct from the other body types employed in honorific portraits, which featured clothing that was worn in everyday life to highlight the subject’s role in civic life.

The body of the so-called heroically nude portrait is often partially clothed with a chlamys. From the late classical period onward this garment appeared in representations of Greek heroes, who wore it either bunched over one shoulder or wrapped around the neck and pinned on one side. The latter arrangement is reflected in a fresco from the House of the Dioscuri at Pompeii, in which the Greek hero Perseus stands in heroic nudity, with a dark-red chlamys draped across his shoulders and wrapped around his left arm (fig. 14.7). The chlamys was worn in daily life by more fully clothed soldiers, hunters, and travelers throughout the Greek world; it was also the standard garment of Hellenistic rulers. In the late republican and imperial periods, its Roman equivalent, the [glossary:paludamentum], was worn by military commanders, including generals and the emperor. By late antiquity, the chlamys had become part of the costume of the imperial court and of imperial governors, for whom its long-standing military associations signified the wearer’s power and authority.

Heroically nude portraits frequently incorporate weapons, such as the spear and the sword, the latter of which might be accompanied by a [glossary:balteus], a scabbard, or both. Such weapons were employed in images of heroes but were also used by men in military service. Numerous examples also depict an integral support carved in the form of armor, specifically a cuirass.

The artificiality of the heroically nude portrait is further emphasized by the juxtaposition of the idealized body with a seemingly individualized head. For example, in a portrait of a man from ancient Ostra, Italy, the youthful, muscular physique contrasts notably with the more mature features of the head, including the sagging cheeks, marked nasolabial folds, and wrinkled neck (fig. 14.8). While Fragment of a Portrait Statue of a Man no longer bears its head, it is likely to have followed the conventions of Roman portraiture in offering a likeness of the subject to complement the idealized, powerfully built body.

The Diomedes Statuary Type

The Chicago statue exhibits certain stylistic similarities to an earlier Greek statuary type associated with the hero Diomedes, which may have been created in the fifth century B.C. During the Trojan War, Diomedes was renowned not only as one of the shrewdest and mightiest of Greek soldiers, but also for his theft of the [glossary:Palladium].

The best known example of the statuary type was found at the Italian site of ancient Cumae and is now in Naples (fig. 14.9). It depicts the hero in a dynamic [glossary:contrapposto] stance, with his weight on his right leg and his hip thrust slightly outward. His bent left leg extends forward, as if he is shown in mid-stride, while his torso is turned slightly toward his left. Other examples suggest that the proper left arm was bent and the proper right arm lowered, possibly with a drawn sword in hand. The hero is sometimes represented with a balteus across his chest and a scabbard under his bent left arm, as in a statue in Munich (fig. 14.10). It is unclear whether certain attributes were Roman additions or were original to the prototype.

The Diomedes type was one of the most popular bodies employed in Roman heroically nude portraits, as suggested by the numerous examples that have been identified by Caterina Maderna. Portraits of this type have been recognized primarily on the basis of the characteristic pose described above. For instance, a statue of the emperor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–38) from Vaison-la-Romaine shows the same stance, with his left arm bent at the elbow and his right arm relaxed (fig. 14.11). Other examples combine this pose with attributes generally associated with statues of Diomedes—cuirass, sword, scabbard, and balteus—albeit with some variations in their appearance and placement.

The Chicago statue’s pose exhibits a dynamism comparable to that of the Diomedes type, with the proper left thigh thrust forward as if the figure were in motion. The remains of the upper arms and shoulders suggest that they might have been consistent with the type as well. The proper left upper arm is attached to the torso, but at the point of breakage it appears to angle away from the body (fig. 14.12). Conceivably, the arm could have been bent at the elbow and the forearm extended forward, perhaps supporting the chlamys, not unlike the statue of Hadrian described above. The proper right shoulder, which seems to point downward, preserves the remains of a scabbard, implying that the arm cradled a sheathed sword in a nearly vertical orientation. A similar pose can be seen in an over-life-size portrait of a young Marcus Aurelius in San Antonio (fig. 14.13). In this sculpture, the top part of the scabbard is ancient and is carved from the same block as the body, much like the Chicago work. The placement of the sheathed sword on the figure’s right side is not typical in statues of the Diomedes type; perhaps this variation is the result of the sculptor’s creative initiative.

The Cuirass Support and Its Associations

Based on their attributes—namely the chlamys, weapons, and armor—it has been suggested that heroically nude portraits may have been intended to honor individuals for their military service. While the chlamys and weapons carried general heroic and military overtones, as discussed above, the cuirass support is thought to have explicitly referenced the subject’s military career. As a form of armor, the cuirass was worn not only by Mars in his role as the god of war, but also by soldiers, military leaders, and the emperor as commander in chief of the Roman legions.

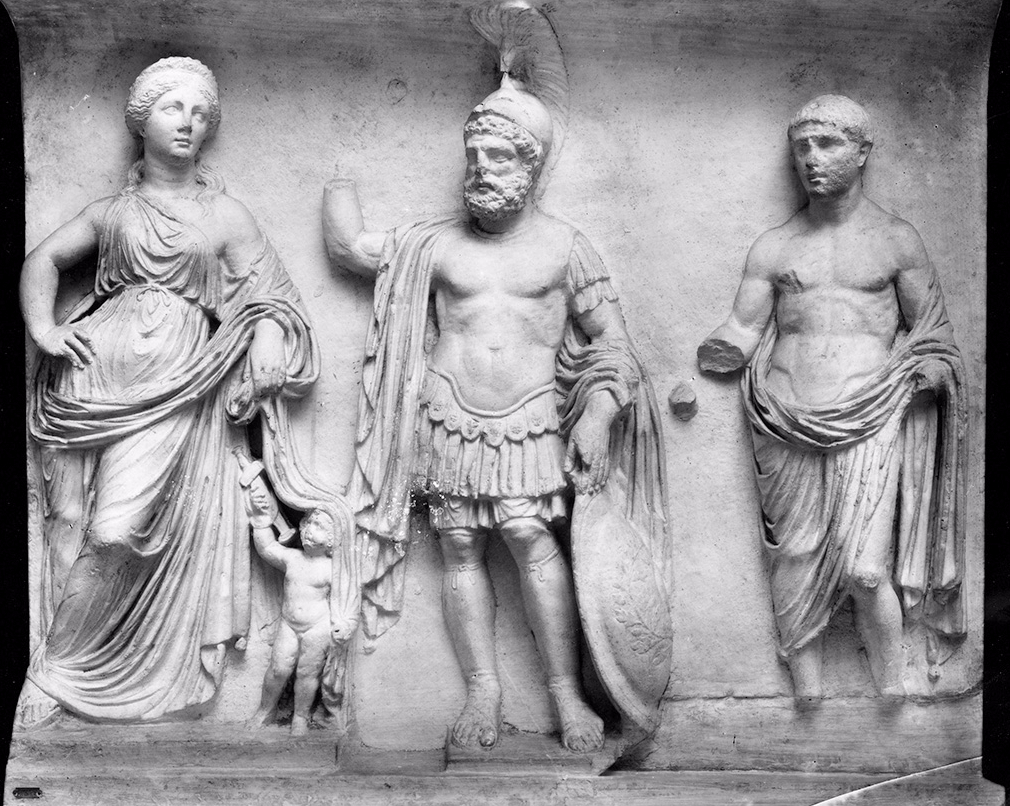

Cuirass supports in heroically nude portraits take two forms, described by modern scholars as the classical type and the Hellenistic type. The classical type features modeled breast- and backplates that imitate the musculature of a torso and a curved lower edge, with [glossary:pteryges] attached, as seen in an image of Mars on a relief from Carthage (fig. 14.14). The Hellenistic cuirass, although initially cylindrical in form, had come to resemble the classical type—with a modeled surface and a curved lower edge—by the early imperial period. It was distinguished by a row of short leather straps attached to its lower edge, which covered the longer straps of the vestlike garment. The earlier, cylindrical form of the Hellenistic cuirass appears in the support of a portrait of late republican date, known as the Tivoli General, which was found in the sanctuary of Hercules Victor at Tivoli (fig. 14.15). Two undergarments were worn beneath both cuirass types: a short-sleeved tunic and, as noted above, a vestlike garment to which leather straps were attached at the lower edge and the armholes; these straps are often visible in statuary supports.

From the late republican period through the Augustan age, only the Hellenistic cuirass was used in the supports of heroically nude portraits, and examples are known as late as the Flavian period (A.D. 69–96). In the second century, the classical type came to replace the Hellenistic type in such supports. Where it is depicted as a support, the cuirass is either draped over a tree trunk, propped up against one, or standing upright. The support in the Art Institute’s Fragment of a Portrait Statue of a Man is a classical cuirass draped over a tree trunk, making a date in the second century likely.

Both imperial portraits, such as those depicting Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius discussed above (see fig. 14.6 and fig. 14.13), and portraits of unidentified men employ the classical cuirass draped over a tree trunk. In several cases it is used in [glossary:theomorphic] portraits representing men in the guise of Mars, as seen in an example in Paris, which is paired with a statue of a woman in the guise of Venus, the Roman goddess of love and Mars’s consort. Here the male is nude, wearing only a helmet—a characteristic attribute of Mars—and a balteus with a sheathed sword; the cuirass support is on his left side (fig. 14.16). It is therefore conceivable that the Chicago statue portrayed either an imperial or a private individual, who was perhaps shown in the guise of Mars. However, in the absence of its head there is no way to know.

In portraits like the Chicago example, the presence of a cuirass might also allude broadly to military success. Its deliberate placement over a tree trunk clearly indicates the subject’s disarmament, perhaps following victory in battle. This reference to disarmament carried an additional layer of meaning in portraits assimilating the individual to Mars: in Roman imperial imagery, the war god was sometimes shown having been disarmed by Venus, suggesting the idea that success on the battlefield led to peace, abundance, and prosperity. The depiction of the sword in the parade grip—a quiescent position rather than an active one—might have reinforced the impression of disarmament in examples like the statue in San Antonio (see fig. 14.13) and probably the Chicago statue as well.

Display Contexts

The Art Institute’s Fragment of a Portrait Statue of a Man could have been displayed in several possible settings, depending in part on whether the subject was a member of the imperial family or a private individual. Nude portraits of the emperor and other imperial men have been found in a variety of contexts throughout the empire. In public settings, they likely served an honorific purpose in civic structures such as basilicas, bath complexes ([glossary:thermae]), and monumental fountains ([glossary:nymphaea]), as well as theaters and [glossary:odea]. In religious contexts, such as sanctuaries and temples, they could have functioned as honorific portraits or cult images. While the use of nudity undoubtedly signaled an imperial man’s exemplary nature, it might further have alluded to his divinity, particularly in the case of deceased, deified subjects.

In contrast, private portraits employing a nude statuary body are rarely found in public settings. This scarcity has led modern scholars to suppose that nudity was generally considered inappropriate for the depiction of living, nonimperial individuals. However, a few heroically nude portraits of private men are attested in public contexts. In some cases, the subject appears to have had a distinguished military career, such as a veteran and priest of the [glossary:imperial cult] named Gaius Sempronius Visellius, whose portrait statue was erected in the city of Panemoteichos in western Pisidia in Asia Minor. In other cases, the man might have been honored for his notable generosity and esteemed character. For example, the respected senator M. Nonius Balbus was represented in a number of statues at Herculaneum, probably including a nude portrait found in the city’s theater.

Some private portraits in heroic nudity have been linked to domestic settings, particularly Roman villas, where they presumably served as self-aggrandizing images of the owner or his family members. One example is a headless male statue, complete with a cuirass support of the classical type, which was found under the Via Cavour in Rome in the remains of a well-appointed house of imperial date (fig. 14.17). This portrait was prominently displayed in the forecourt of the house, where it was juxtaposed with sculptures of mythological subjects. Given the dual nature of the Roman house as a space for living and working, heroically nude portraits would have been seen not only by the members of the household but also by friends, business associates, and other visitors, who would have understood their intended message.

Nude statues of private individuals also come from funerary contexts, often in the form of theomorphic portraits. For example, a sculptural group depicting a nude male in the guise of Mars and a draped female in the guise of Venus was found in the Isola Sacra necropolis near Ostia. The group’s discovery in this location suggests its likely function as a double funerary portrait. In such settings, a heroically nude portrait was presumably considered appropriate for commemorating the virtues and positive qualities of the deceased, perhaps even intimating his passage to the world of gods and heroes. Indeed, “the sculptor, by giving the deceased the characteristic appearance of those heroes in Greek art—their costume, their ageless physical beauty—could visually enroll the deceased directly among their number.” The addition of a cuirass support in this context might have carried a message beyond that of the man’s military achievements, possibly referring to his death on the battlefield.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s Fragment of a Portrait Statue of a Man depicts an unidentified, heroically nude male figure. The statuary body draws upon an idealized, muscular type associated with the image of the Greek hero Diomedes, albeit with some minor variations in pose and attributes. The nude body combined with the chlamys, sheathed sword, and cuirass support promoted a message of the subject’s exemplary, if not heroic, nature, as well as his successful military career. The classical cuirass support allows for the likely dating of this portrait to the second century A.D.

Heroically nude portraits were created to honor imperial and private individuals alike, although their display contexts varied. If this sculpture portrayed an emperor or a member of his family, it might have been erected in public in a civic structure or monument, or alternatively it could have appeared in a religious setting in a sanctuary or temple. If the portrait depicted a private man, it was more likely displayed in an elite Roman home or in a funerary context.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object is a fragment of an over-life-size sculpture of a heroic male nude that, as evidenced by the lack of cavities for dowels, pins, or [glossary:tenons], was carved in the round from a single block of stone (fig. 14.18). The marble is a white, medium-grained variety that has been identified as Parian. Owing to the deteriorated condition of the stone, attributable to past environmental exposure, very few traces of toolmarks remain on the surface of the object. The proper left leg is a restoration carved from a coarse-grained, white marble that has been identified as Thasian. At some point, the entire front of the object was heavily abraded with chisels, rasps, and files to remove much of the exfoliated stone and reveal the musculature of the figure beneath. It is unclear whether this aggressive treatment occurred at the same time as the restoration of the proper left leg. Evidence of antiquity in the form of prominent oxide staining is apparent almost uniformly across the surface. No evidence of [glossary:polychromy] or gilding has been detected. In 2012, the object underwent extensive conservation treatment, in which [glossary:laser ablation] was used to remove an unsightly, uniform surface incrustation covering almost two-thirds of the figure, particularly across the back of the [glossary:chlamys].

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

Original

The marble is a warm ivory hue with readily apparent crystals, many of which display a high degree of translucency. Although surface staining from burial distracts the eye, the stone appears relatively homogeneous and free of visible veins or banding.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); iron oxides (traces)

Restored leg

The marble is uniformly bright white with a warm tone. The stone is dense and compact, but individual crystal grains can be easily distinguished on close inspection.

Primary mineral: dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2

Accessory minerals: apatite, Ca5(PO4)3(F,Cl,OH) (traces); mica, X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4 (traces); quartz, SiO2 (traces)

Petrographic Description

Two samples were taken. From the original sculpture, a triangular-shaped sample 1 cm high by 1.3 cm wide was removed from the upper portion of an area of incipient [glossary:cleavage] extending on a vertical diagonal on the proper left side of the chlamys, approximately 23.5 cm from the bottom. From the restored leg, a sample approximately 3 cm high by 1 cm wide was removed from a point of incipient cleavage on the face of the break edge, in the lower proper left quadrant. The samples were then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of each sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of each sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 μm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Original

Grain size: medium to coarse (average MGS greater than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 2.17 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: [glossary:embayed]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 14.19

Restored leg

Grain size: medium to coarse (average MGS greater than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 2.64 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic with interlocked crystals

Dolomite boundaries: [glossary:sutured]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed slight intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 14.20

Provenance

Original

Marble type: Parian (marmor parium)

Quarry site: Lakkoi, Korodaki valley, on the island of Paros, Cyclades, Greece

The determination of the marble as Parian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

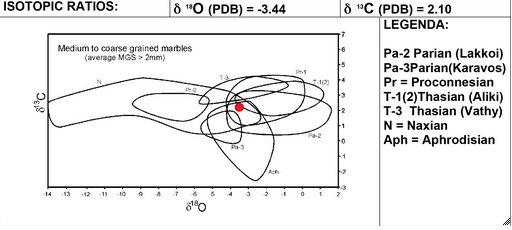

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 14.21

Restored leg

Marble type: Thasian (marmor thasium)

Quarry site: Cape Vathy, island of Thasos, Greece

The determination of the marble as Thasian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

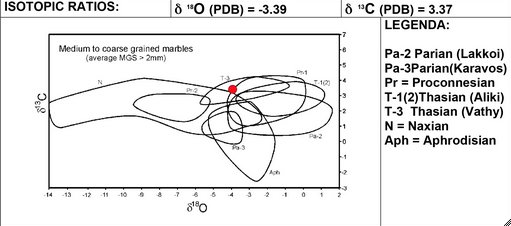

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 14.22

Fabrication

Method

The object is a fragment of a larger sculpture whose dimensions would have been over life-size. The lack of any holes for pins, dowels, or tenons in the neck or arms serves to confirm that the work was carved in the round from a single block of stone and that the missing head and appendages are the result of damage rather than intentional separation. The work was carved using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Due to the weathered condition of the stone and the intrusiveness of a previous restoration, virtually no toolmarks remain on the surface of the object.

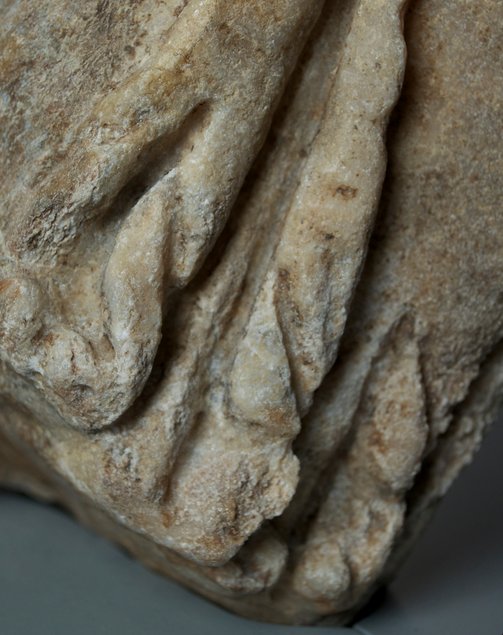

The traces that do remain are those of a running drill, as indicated by the circular depressions at the end points of the lines (see fig. 14.23). The running drill method was employed to delineate the majority of the figure’s primary contours; evidence of this can be seen between the front of the proper left arm and the rib cage, at the top of the outermost fold of the chlamys on the proper left side, at the top end of a fold of the chlamys on the proper right side of the chest, between several of the folds of the [glossary:cuirass], and between the straps of the garment worn beneath the cuirass (fig. 14.24).

A groove similar in shape to these drill holes is visible between the back of the proper left arm and the chlamys. This channel is very bright white, however, and appears to be quite new. It is most likely not antique but rather connected to the extensive previous restoration. There is another new-looking line running along the front edge of the chlamys above the chest (fig. 14.25). Superficially this line resembles that made by a flat chisel held at an oblique angle. However, the whiteness of the line, together with its proximity to the recently abraded areas, strongly suggests a modern hand.

Remains of a bridge, strut, or other point of attachment are apparent atop the stone support (fig. 14.26).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Visual examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Some blue material resembling pigment is visible on the back of the proper left side of the chlamys, but, as it overlies an area of damage, it must be considered postdiscovery contamination.

Condition Summary

The object is fragmentary: primary losses include the head and neck, most of both arms and legs, and all support structures below the end of the proper right thigh. Both arms are missing just below the shoulder. As a result of this damage, nearly all of the attribute held against the proper right arm has also been lost. The proper right leg is missing from just above the knee, and the proper left leg is missing from a point level with the hip, just below the buttocks. Significant losses to the chlamys on the proper left side may be associated with the loss of this leg; these losses extend from the bottom of the extant stone up to the waist.

There are secondary losses to the genitals, the front folds of the cuirass, and the portion of the chlamys that encircles the neck, especially in the area where a [glossary:fibula] once gathered and held the garment above the proper right clavicle. Elsewhere notable lacunae and associated chips and losses can be seen, in particular on the back and proper right side of the chlamys, along the break edges of the arms, and along the bottom edge of the extant support. Large, circular patches of [glossary:exfoliation] are present on the abdominals, on the chlamys around the neck, and in a vertical line along the proper right thigh in association with an area of prominent iron staining.

At some point, a replacement for the proper left leg was carved and attached to the figure. This addition is itself fragmentary, with the leg missing below midthigh. Associated voids and lacunae are visible around the bottom edge of the addition, as is a short but deep vertical gouge. A long, deep scratch extends diagonally forward from the groin. It is not possible to ascertain by visual inspection how the restored leg was attached to the figure, but it is reasonable to assume that a metal dowel or rod of some kind was used. As further support to the join, an adhesive was employed. This adhesive resembles a modern synthetic resin, specifically a polyester, indicating that it would have been put in place after 1940, when this material became commercially available. Where the perimeter of the join is most visible, the adhesive was sculpted close to the surface and tooled to mimic the texture of the stone on either side of the break, exposing air bubbles in some areas (fig. 14.27). The restorer also applied paint across the line of adhesive in an attempt to visually connect areas of staining on either side of the break. Where it is less visible—in the deepest part of the groin and underneath the buttock—the adhesive was spread heavily across the margins of the repair and large patches of excess adhesive were not removed.

There is no hole or visible means of attachment on the underside of the restoration, either extending up toward the body for attachment at the hip or providing a cavity to accommodate a further addition below the thigh. This suggests either that the restored leg is a fragment of a once larger, more complete restoration or that it was deliberately carved to resemble a fragment.

It is not possible to determine definitively when this restoration was added, but the available evidence yields a few possible scenarios. First, the restored leg might be a fragment of an ancient repair that was discovered in the same context as the rest of the object. Second, the fragment could be a remnant of a much later repair, possibly made during the eighteenth or nineteenth century. Third, the fragment might be an entirely modern creation contemporaneous with the synthetic resin. Fourth, a leg from another sculpture might have been adapted to fit this one.

In support of the first scenario, the use of Thasian marble, the fact that the restored section is a fragment, and the similar patterns of staining on both sides of the break lend weight to the theory that the repair dates from antiquity. In addition, the decohesion seen in thin section and the [glossary:laminar] cleavages present on the bottom surface of the leg suggest some age and exposure. There is no visible trace of a channel for the ancient technique of pouring lead to secure a pin, but this by itself does not eliminate the possibility that the repair is ancient.

In support of a later repair, however, it must be noted that Thasian marble was a stone commonly employed for restorations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, making it plausible that the leg was added shortly after the statue was unearthed, if its excavation coincided with the prodigious archaeological activity of that period. But the sensibility of that era favored completion: statues with missing appendages were usually fully restored by integrating newly carved elements. Because there are no holes in the arms and neck, it is clear that the sculpture was never completely reconstructed in this fashion. Still, the severity of the imbalance caused by the missing leg could have troubled an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century collector or restorer to the extent that a restoration resembling a fragment was added to harmonize the work.

While the asymmetry may have been equally striking to a twentieth-century dealer or restorer, the choice of stone probably rules out an addition that recent; by this period, the stone used for repairs was usually restricted to Carrara marble or another easily obtainable, workable variant. The tooling at the top edge of the restored leg does not appear ancient but instead exhibits the mechanical, punched surface created by the use of a modern bushing hammer (fig. 14.27). The evidence that such a tool may have been used to smooth over what appear to be misalignments provides some support for the hypothesis that a leg from an older sculpture, carved in Thasian marble, was adapted slightly to fit the torso. In this scenario, the reinforcing resin would also have functioned as a filler between the imperfectly aligned surfaces. The staining, which seems to be compelling evidence of antiquity, could quite easily have been added deliberately. The presence of the synthetic resin alone does not favor any of the possible scenarios over the others. It could have been added immediately after excavation, if the sculpture and the leg were discovered together in the mid-twentieth century. It could have been used to reinforce an existing repair that had become unstable, either by removing the leg entirely and resetting and bonding it, or by inserting copious amounts of the resin into the loose but still attached join. Or it could be an element of what may have been the first and only intervention, made in the latter half of the twentieth century. Without fully removing the leg to inspect the interior surface for additional clues, it is impossible to come to a sure conclusion as to the date and methodology of this restoration.

The appearance of the original sculpture is conspicuously marked by the heavy impregnation of oxides from a presumably iron-rich burial environment, resulting in discoloration so profound as to resemble actual inclusions in the stone matrix. These stains take the form of dark maroon circles on the lower and proper right abdominals and on the outer margin of the proper right thigh. Iron staining of a more orange tone can be seen following a vertical line in the center of the proper right thigh. More comprehensive and uniform iron staining of a deep red-brown color is present on the stone support on the proper right and on the drape of the chlamys across the chest. In contrast, the proper right shoulder, the remains of the [glossary:scabbard], and the back of the chlamys show a paler orange staining.

As would be expected, the same type of staining is not seen on the restored leg. While the restored leg is indeed stained, these anomalies are of a different tone and character. A pronounced yellow discoloration is visible in the front, and in several areas dark grayish-brown stains are present. Staining notwithstanding, the marble of the restored leg is in good condition, and its surface is smooth.

The same cannot be said for the main portion of the sculpture, which, aside from the front, exhibits profound decohesion resulting from the action of running water. In particular, a vertical band of stone between the proper right side of the torso and the front edge of the chlamys has taken on an extremely granular appearance, akin to that of coarse-grained sugar (fig. 14.28). In order to reveal the mass and musculature of the figure, the front and a portion of the sides were at some point heavily abraded using chisels, rasps, and files. Traces of these tools are visible throughout. In the process, the sculpture lost a significant amount of original material, up to 3 mm in some areas. The result of this treatment is a sharp contrast in color, texture, and sheen between the two zones. The neck, the center of the chlamys below the neck, and the abdomen also display a slight sheen, from either polishing or the application of a coating. It is also possible that an acid treatment was applied to the stone prior to the abrasive treatment and that this sheen is a result of that chemical intervention.

There is a small hole approximately 7 mm in diameter on the top of the scabbard (fig. 14.29). Inspection of the interior reveals that the hole is stained in the same manner as the exterior of the sculpture. It is thus reasonable to assert that the hole was present in antiquity at the time of burial. The presence of a hole in this location is somewhat puzzling, in that its function is clearly to connect two parts. Given that this is the closed end of the scabbard, presumably the missing piece would be a rather short segment. If it were carved in marble, such a small projection would have been unlikely to have required a dowel or pin. This raises the possibility that the tip of the scabbard was made of a different material, such as metal, which required a physical attachment. Alternatively, a more straightforward explanation would be that this small projection broke away at some point during the life of the sculpture and a small, marble replacement, now lost, was indeed attached with a pin.

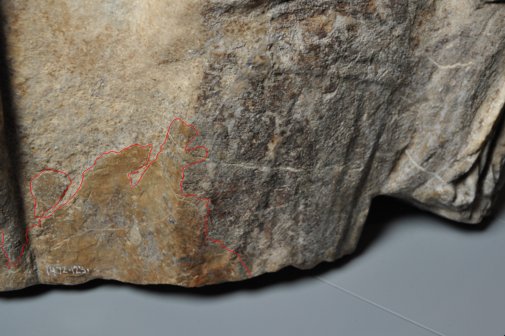

Elsewhere interesting contextual anomalies can be seen. [glossary:Pozzolana], small pebbles, and ceramic fragments remaining from the burial environment are deeply embedded in the folds of the cuirass (fig. 14.30). A lump of iron in a state of active oxidation is wedged in the groove where the drapery of the chlamys meets the torso on the proper right side (fig. 14.31). Inclusions of [glossary:protolith] are present on the back of the support (fig. 14.32). In this same location, well-adhered, hard, flat, compact layers of orange patina are apparent (fig. 14.33).

Conservation History

Prior to 2012 there is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection. At some point in the object’s history, a repair was made on the back edge of the proper left side. A detached fragment was bonded back into position using an opaque adhesive that remains visible around the margins of the repair and that has yellowed slightly. This adhesive bears a strong resemblance to the adhesive between the original sculpture and the restored leg.

In the spring of 2012, the object was treated in preparation for its reinstallation in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art, in an effort to improve its overall appearance and in particular to reduce a disfiguring gray incrustation on the back of the chlamys. This crust was removed by laser ablation employing three different Nd:YAG systems. Some areas of more intractable incrustation were first softened with a poultice of distilled water and paper pulp. Additional areas of extremely hard black crust in the chest and neck area received a poultice composed of a cationic exchange resin and polymeric adsorbent media. Unsightly rust stains were minimized with the aid of an electrolytic reducing agent applied as a poultice using paper pulp. At the close of treatment the object was further cleaned using high-pressure steam and a vacuum cleaner fitted with a HEPA filter.

In September of 2012, following the laser-cleaning treatment, preexisting gouges, scratches, abrasions, and surface anomalies, particularly around the neckline of the chlamys and along the back, were more noticeable and visually distracting than they had been prior to treatment. Smaller areas of blanching and pitting, combined with the large areas of iron staining, conferred an additional visual discontinuity not previously apparent. To harmonize the overall appearance, these areas were toned with water-soluble media.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini