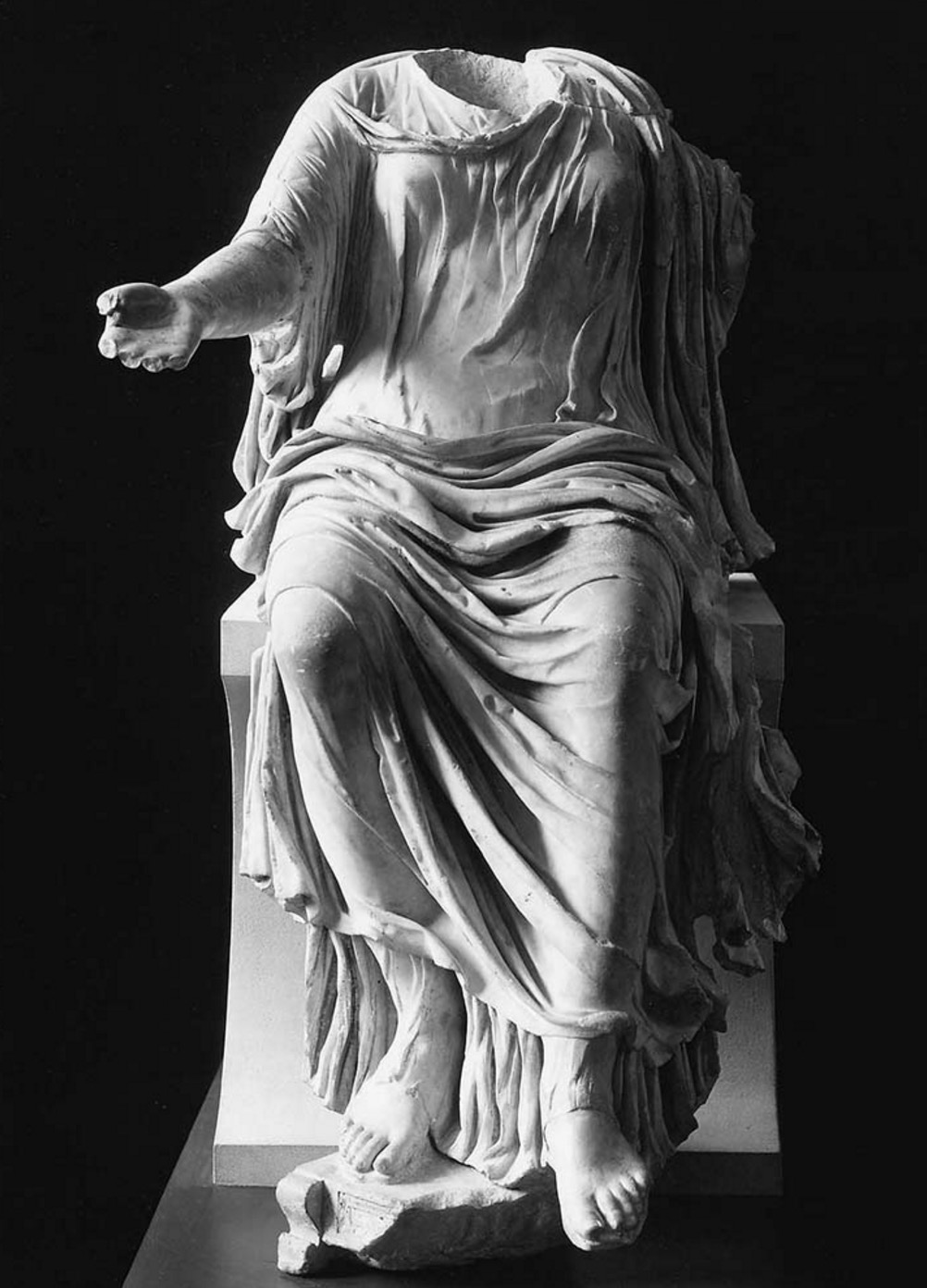

This under-life-size statue depicts a female figure seated on a rocky outcrop. The sculpture conveys a sense of grandeur and authority despite its reduced dimensions. Carved of fine Parian marble, the figure wears a full-length [glossary:chiton] with short sleeves, the identification of which is affected by losses to the proper left arm and near the proper right shoulder. This garment was typically held together by pins running down each sleeve, and the gatherings of drapery along the proper right arm imply that this was the case here. The chiton clings to the figure’s breasts and is girt at the waist to form a [glossary:kolpos] (fig. 10.41). The garment gathers in heavy, vertical folds between the lower legs, yet it is incredibly sheer where it drapes over the proper left leg. Over the chiton the figure wears a thicker [glossary:himation] that drapes over her left shoulder and across her back, where it hangs in diagonal ridges that draw the viewer’s eye down toward her seat (fig. 4.1). The himation then wraps around to the front, covering the lap in voluminous folds that contrast with the taut appearance of the section hugging the proper right leg. The feet are clad in sandals (fig. 8.36), the straps of which may have been added in paint.

The figure is missing its head, neck, and arms. A large, slightly conical socket with a [glossary:keyed] surface located between the shoulders accommodated the separately carved head and neck (fig. 4.3). The arms were also carved separately and joined by means of metal pins, traces of which are still visible in the front part of the hole for the proper right arm. Based on the position of the shoulders, the proper left arm appears to have been extended outward and might have been raised. In contrast, the proper right arm would have been lowered and perhaps held slightly away from the body, much like a bronze statuette of an enthroned figure in the Art Institute’s collection (fig. 8.37; see cat. 141). It is likely that the head and the arms would have incorporated one or more attributes that would have informed the viewer of the subject’s identity and, if relevant, her divine realm.

Without the head, arms, and accompanying attributes, the subject of Statue of a Seated Woman cannot be confidently identified. However, formal and stylistic features allow for a consideration of the sculpture’s possible functions. In particular, the heavy drapery and dignified pose, when combined with the reduced scale, suggest that it was used in one of several ways. If it depicted a goddess, it might have been a statuary dedication in a sanctuary or an architectural sculpture that adorned a temple, shrine, or other religious structure. Alternatively, it might have been a portrait of a mortal woman, whose exemplary nature, if not her divine assimilation, would have been suggested by the selection of this stately body type.

Seated Goddesses: Greek Precursors

Roman images of seated goddesses seem to have been inspired in large part by earlier Greek representations of female deities, particularly those produced during the classical period. Such Greek works served predominantly religious functions, both as cult statues and dedications and as architectural sculptures adorning the exteriors of temples and other sanctuary buildings.

The classical [glossary:chryselephantine] cult statue of Hera in her fifth-century B.C. temple at Argos, Greece seems to have served as the model for many of the seated cult statues of goddesses in imperial Rome. Although the work does not survive, its appearance has been inferred from a number of Roman coin issues and from several other statues. In these images, an enthroned goddess grasps a scepter in her raised left hand; her right arm is outstretched with an attribute in hand (see fig. 4.5). The Art Institute’s Statue of a Seated Woman evokes this type in a very general way.

Arguably the most renowned representations of seated Greek goddesses that still exist today are the statues from the pediments of the Parthenon in Athens, which were designed by the famed Greek sculptor Pheidias and completed in 433 or 432 B.C. The east [glossary:pediment] illustrating the birth of Athena preserves fragmentary statues of four seated goddesses, two of which, in the north (i.e., right) corner, offer formal precursors for the Art Institute’s Statue of a Seated Woman: K, commonly identified as Hestia, and L, identified as Dione, a consort of Zeus (fig. 8.38). Dione is carved in a single block with another, reclining figure—M—who is identified as her daughter, Aphrodite. Like the Chicago sculpture, the goddesses K and L wear a chiton with pinned sleeves and the thicker, more voluminous himation over their laps. Figure K (Hestia) sits on a rock, which might allude to the home of the gods on Mount Olympos. The Chicago statue is likewise seated on a rock in a somewhat comparable pose, with her upper body turned forward and her legs angled to one side, perhaps to accommodate a placement in one of the triangular corners of a pediment. Based on its scale, pose, and subject matter, the Chicago work may have been formally inspired by this type of statue.

Seated Goddesses in the Roman World

The seated pose was employed in images of a variety of Roman goddesses, who were typically identified in part through the addition of specific attributes that indicated their spheres of influence. It was used primarily in depictions of the mature female deities of the Roman pantheon, including Juno, the goddess of marriage and political organization (identified with the Greek Hera); Ceres, the goddess of agriculture and grain (identified with the Greek Demeter); and Magna Mater, the goddess of fertility and wild nature (identified with the Phrygian Cybele). For example, a statue of Cybele in San Antonio shows the goddess with her characteristic attributes, the [glossary:mural crown], the [glossary:tympanum], and the lions, along with a [glossary:patera] (fig. 4.8). The pose also appears in representations of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and warfare (identified with the Greek Athena); Vesta, the goddess of the hearth (the Roman equivalent of Hestia); Venus, the goddess of erotic love and sexuality (the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite); Fortuna, the goddess of chance or luck (identified with the Greek Tyche); and Hygieia, the goddess of health. The virtues that were associated variously with these goddesses, such as fertility, chastity, beauty, grace, and maternity, were largely connected with the female roles of wife and mother and with the domain of the household. The pose was also used in images of personified virtues, including Felicitas (happiness or good luck), Pietas (dutiful conduct or piety), Pax (peace), and Concordia (concord), particularly on imperial coins (see fig. 8.39). Thus, the seated pose conveyed the maturity, dignity, and gravity of a number of divine female subjects. The Chicago sculpture might therefore represent any of these deities.

Much like their Greek counterparts, images of Roman goddesses were produced for a variety of purposes that were all, on some level, religious in nature. They were created in an assortment of materials and sizes, ranging from colossal cult statues made of richly colored marbles and other precious materials to statuettes in marble, bronze (see fig. 8.37), or terra-cotta. Seated statues of female deities (both large and small) are attested in religious sanctuaries in the Roman world. Whether they had a cultic or dedicatory function remains unclear, as there seems to have been no defined aesthetic differentiation among such images. Although cult statues were not necessarily over life-size or made of extravagant materials, this was often the case. Smaller-scale statues of deities were probably sculpted dedications within sanctuary contexts.

The under-life-size scale of Statue of a Seated Woman suggests that it might have functioned as a dedication in a religious sanctuary, perhaps as an offering to one of the goddesses who were frequently represented in this type of seated pose. Moreover, its creation in high-quality Parian marble might have signaled a significant investment on the part of the dedicant, perhaps meriting a prominent placement in a sanctuary.

Small-scale statues of seated goddesses also functioned as architectural sculpture, often in religious contexts, where they adorned temples, shrines, and other related structures. For example, at Eleusis in Greece, a small treasury of Antonine date (A.D. 138–93) featured statuettes of at least two seated goddesses in its pediment. The statuettes are preserved in a fragmentary state: the first shows the lower body of a goddess seated on a rock, her lap covered by a thick himation (fig. 4.6), while the second includes the majority of a seated, similarly draped female with a fragmentary child on her lap (fig. 4.7). The latter figure also retains traces of a dowel in its right arm, indicating that it had at least one separately carved appendage, much like the Chicago statue. With their seated poses and classicizing drapery, the figures from Eleusis seem to draw formally on prototypes from the Parthenon, yet they are only one-third the size. Statue of a Seated Woman is noticeably larger than these statuettes and therefore could have been part of the pedimental sculpture for a comparable structure.

Seated Portraits of Roman Women

Statue of a Seated Woman could instead have been the statuary body in a portrait of a woman, which might have served either an honorific purpose in a civic setting or a commemorative function in a funerary context.

While men were honored publicly with portrait statues that celebrated their military triumphs, brave deeds, and other forms of service to the state, women were represented far less frequently. They were typically recognized for their civic benefactions—financial sponsorship of games and festivals, buildings, public feasts, and distributions of money, food, and wine—or their role as priestesses. Additionally, women of noble backgrounds could be portrayed in family statuary groups to highlight their dynastic connection to a prominent male figure, often for propagandist purposes.

This distinction between men and women in public life was visually reinforced in honorific portraits through the choice of statuary bodies. While men were generally depicted wearing the clothing associated with their role in society, such as the [glossary:toga] of the Roman citizen or the [glossary:cuirass] of the military leader, women were typically represented in their characteristic dress of the [glossary:tunic] and [glossary:palla] (the Roman equivalent of the Greek chiton and himation, respectively). However, their clothing seems to have intentionally evoked the thinner and more revealing drapery worn by female deities. In this way, the godess-like statuary bodies employed in portraits of Roman women “served to maintain their absence” from public life.

Seated portraits of women were rarely displayed in public contexts, but they were sometimes used to honor private women for their civic benefactions. Women of widely acknowledged exemplary character and virtue, particularly those from aristocratic and imperial families, were also represented in this way. For example, Cornelia (190–100 B.C.), the mother of the renowned politicians and reformers known as the Gracchi, is said to have been recognized as an ideal mother and matron in a seated portrait exhibited publicly in Rome. This now-missing sculpture, which was created posthumously in the late republican or early Augustan period, is thought to have incorporated a statuary body evoking a Pheidian type known as the Aphrodite Olympias. This type is exemplified by a second-century statuary body to which has been added a fourth-century portrait head that might depict Helena (c. A.D. 250–330), the mother of the emperor Constantine (fig. 4.9), herself a respected matron.

Yet overall, seated portraits of women seem to have been considered more appropriate for funerary contexts, where they might have conveyed specific messages about the virtues of the deceased. For example, in a portrait of Severan date (A.D. 193–235), a heavily draped woman is seated on a stool that includes an image of a seated philosopher on the proper right side, highlighting her scholarly pursuits, a sign of her elevated status. This emphasis on the subject’s intellectual interests might not have been considered appropriate for public display, suggesting that the portrait was instead displayed in a funerary setting.

The seated pose was also employed in [glossary:theomorphic] portraiture. In this type of portrait, a mythological body—including its dress, attributes, and gestures—served as a costume through which the virtues and positive qualities of the divinity were correlated with the subject. In theomorphic portraits of both imperial and private women, the goddesses selected for assimilation usually exemplified women’s domestic roles as wives and mothers. Ceres was a popular choice due to her associations with chastity and motherhood, while Venus was esteemed for her beauty, grace, and fecundity, qualities that led to marriage and its ultimate fulfillment, the production of children. Magna Mater/Cybele was similarly honored for her role as protector and mother as well as for her associations with pudicitia (chaste modesty), and Fortuna symbolized prosperity. Juno seems to have been reserved primarily for the empress’s use, likely due to the goddess’s role as Jupiter’s consort, a relationship that was echoed by that of the imperial couple.

Among portraits of private individuals, examples showing women clearly in the guise of seated goddesses with their attributes surviving are infrequently attested. One such statue in the J. Paul Getty Museum depicts a Roman matron who has been assimilated to Cybele (fig. 10.43). The connection is made evident by the presence of numerous attributes associated with the goddess, including the mural crown atop her head, the bunches of wheat and poppies in her right hand, the cornucopia and rudder under her left arm, and the lion sitting attentively at her feet. However, she is distinguished as a mortal by her individualized portrait head: she has a broad face; narrow eyes; a small, tightly closed mouth; and distinct nasolabial folds that indicate her maturity. It is evident that the subject, who would almost certainly have been a woman of elevated wealth and status, had a strong interest in the cult of Cybele, and might even have been a priestess of the goddess.

Although seated portraits of both imperial and private women are rare, it is possible that Statue of a Seated Woman could have been the statuary body in a portrait of an esteemed matron. However, if it did in fact serve such a purpose, this pose would have conveyed the subject’s feminine virtues and her exemplary character—qualities for which the goddesses represented in this form were also clearly celebrated.

Conclusion

Statue of a Seated Woman, with its classicizing drapery and seated pose, presents a headless image of a female of considerable dignity. It is most likely that it depicted a goddess venerated for her feminine virtues. Given its reduced scale, the statue might have functioned as a dedication in a sanctuary, or it might have been an architectural sculpture, perhaps displayed in the pediment of a small temple, shrine, or other religious structure. Alternatively, although perhaps less likely, the work may have been the statuary body in a portrait of a Roman matron, which could have served an honorific purpose in a civic setting or a commemorative function in a funerary context.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This sculpture depicts a female figure, roughly two-thirds life-size, seated on a rocky outcrop (fig. 4.18). The object was carved in the round from a single block of medium-grained, white marble that has been identified as Parian. The head and arms of the figure, which were carved separately and affixed to the sculpture by mechanical means, are no longer extant. The surface of the marble displays a broad range of toolmarks. No evidence of [glossary:polychromy] or gilding has been detected. A pronounced yellow patina is visible in several areas. Other areas display a granular appearance, suggesting an exposed or outdoor location in antiquity. Burial evidence is found in the abundance of rootlets across the surface and in the presence of a reddish-brown coloration in selected areas. The object is in sound condition overall, and despite a great many losses, both major and minor, the fluidity and masterful handling of the carving and the legibility of the drapery are clearly evident. No signs of previous restoration or other interventions, save the thinning of the abundant root growth following excavation, have been found on the object itself, and no written records of treatment accompany the object in either the conservation or the curatorial files.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The exterior surface of the marble exhibits a warm, ivory tone overall, but the interior is bright white.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant)

Petrographic Description

A sample roughly 1.2 cm square was removed from the highly textured surface on the proper left back corner, approximately 10 cm up from the bottom and 20 cm in from the proper left edge. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

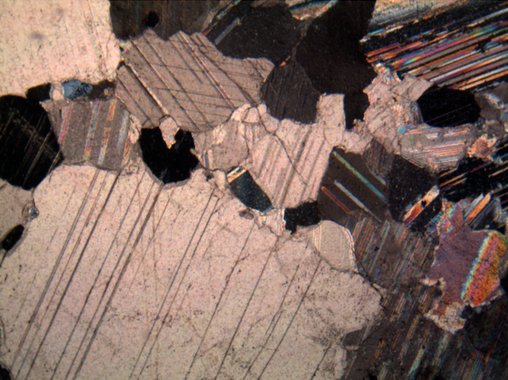

Grain size: medium to coarse (average MGS greater than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 1.68 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: [glossary:embayed]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed slight decohesion.

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 4.30

Provenance

Marble type: Parian (marmor parium)

Quarry site: Lakkoi, Korodaki valley, on the island of Paros, Cyclades, Greece

The determination of the marble as Parian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

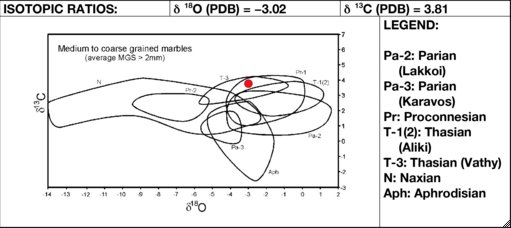

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 4.22

Fabrication

Method

The figure is roughly two-thirds life-size. The body was carved in the round from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

A separately carved head, now missing, was once attached to the body by means of a socket and tenon reinforced with an adhesive. The profile of the socket into which the head was fitted suggests that the head also included the neck and the collarbone. The tenon would have been rather broad, spanning the entire diameter of the neckline of the [glossary:chiton], and, based on the interior shape of the socket, would have been worked for insertion with a [glossary:keyed] surface in a slightly conical form.

Separately carved arms, now missing, were inserted into the body by means of metal pins. Sockets were carved into the body at the points of attachment of both arms; that for the proper right arm is slightly deeper than that for the proper left. The sockets are recessed for both mechanical and aesthetic purposes. The topography of the join face for the proper left arm suggests that a simple butt join was used, allowing the metal pin to bear the weight of the join. Half of the socket on the proper right arm is missing; however, what remains of its profile suggests a more concave shape, which may mean that this arm was carved with a tenon at its end. It is unclear by what means the pins in the arms were further reinforced. No keying is present on either of the join faces, which suggests that the pins might have been fixed with lead. However, the surface preparation of arm joins does not necessarily testify to whether lead alone, lead in combination with a cement or adhesive, or an adhesive alone was used to reinforce the pinning.

In the socket for the proper left arm, the angle of the pin, together with the angle of the join face, indicates that the missing arm would have been held away from the body, perhaps extended to the side or aloft. On the proper right side, the position of the drapery and the angle of the pin, combined with the profile of the socket, suggest that the arm was positioned so as to be elevated slightly above the thigh and either pointed in the same direction or extended some small degree to the outside.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The surface of the rocky base upon which the figure sits, particularly in the back, shows marks left by a point chisel (fig. 4.23) and a flat chisel (fig. 4.35).

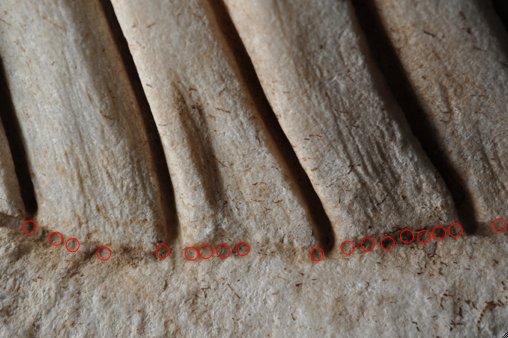

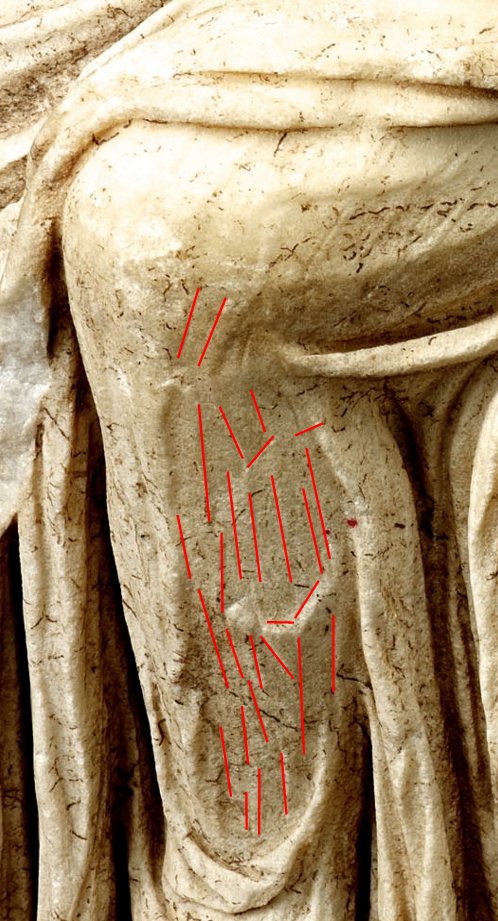

The folds of the chiton and [glossary:himation] are a fantastically complex array of swirling grooves and channels. Close inspection reveals that the sculptor used a wide variety of tools to render these forms. The artist began with a drill, piercing the stone at intervals to create deep tunnels. Along the demarcation between the hem of the chiton and the base, a drill 2.9 mm in diameter was used (fig. 4.34). In the larger folds, drills up to 4.15 mm were used (fig. 8.40). This network of pierced holes was then excavated with a roundel or channeling tool. The drill holes of the original perforations remain visible along many of the lines of carving (fig. 4.20). Deep inside the folds of the drapery in the front, between the proper left side of the chiton and the part of the himation that hangs from the proper left arm, a crosshatched pattern characteristic of a claw chisel is apparent (fig. 4.28). Elsewhere in the drapery, broad, shallow folds were made using a bullnose chisel or roundel (fig. 4.24), while deep, narrow channels were made using a channeling tool.

Along the length of the proper left leg, where the carving is meant to suggest diaphanous fabric clinging to the limb, a flat chisel was used (fig. 4.32).

Marks from a scraper are visible in numerous places across the surface but are particularly noticeable running lengthwise along the folds of the himation in the back (fig. 4.25).

The interior of the neck cavity was sharply keyed with single, percussive blows of a point chisel to provide extra tooth for an adhesive (fig. 4.27). Within the deepest of these cuts, traces of a white material were found. A sample was taken from the area and analyzed, but the results were inconclusive.

The pins used to affix and support the arms were made of iron and were bar or lozenge shaped, as evidenced by the profiles of the holes drilled to receive them (fig. 4.21). Both cavities show orange staining characteristic of oxidized iron, and, at the front portion of the hole for the proper right arm, traces of oxidized iron remain encrusted on the surface of the stone (fig. 4.26).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The marble itself is in stable condition, although surface dirt and soiling are evident throughout.

A pronounced yellow patina is visible in isolated areas: along the proper left thigh, across the middle sweep of the himation on the lap, and in the textured area atop the columnar portion of rock on the proper left side. The surface of these patinated areas is dense, with a waxy appearance. When examined under ultraviolet radiation, these areas have a pale greenish-yellow appearance, in contrast to much of the rest of the sculpture, which appears more violet overall. This indicates that these patinated areas constitute the oldest surfaces on the sculpture (fig. 4.33).

It is clear that the composition of the patinated surface protected the stone to some degree, because outside of the patinated areas, the marble is much whiter and brighter in color and has a granular, porous, sugary texture. This sugary appearance, a sign of decohesion and [glossary:exfoliation] of the stone’s surface, is particularly evident on the swath of the himation hanging down between the legs and on the columnar rock on the proper left side (fig. 4.31). The decohesion was caused by prolonged exposure to sunlight, suggesting a possible outdoor location in antiquity.

The gathering around the waist of the chiton displays a more reddish-brown color than the rest of the stone. Presumably this coloration is a result of contact with iron-rich burial sediments. Under ultraviolet radiation, this portion of the chiton appears the same pale greenish-yellow as the areas of yellow patina.

The object has sustained numerous losses. Major losses are evident in the area of the proper right shoulder and breast. The part of the himation that covered the front of the proper left arm is also missing, as are significant portions of the himation in the back on the proper right side, between the back of the thigh and the ankle. There are also noticeable losses in the sweep of the himation in the front between the proper left knee and the proper right ankle. Under ultraviolet radiation, these areas appear bright purple, which reveals that this damage is quite recent. Losses to the feet include a large missing area on the top and side of the proper right foot as well as half of the second toe. The outside corner of the proper left big toe is also missing. A large spall is present on the front corner of the base on the proper right side, directly below the proper right foot. Moderate though extensive losses, gouges, and [glossary:spalls] are in evidence on the folds on the back of the himation. There are further losses in the upper portion of the chiton, particularly in the center between the breasts. Minor scratches and gouges are distributed uniformly across the surface of the object.

The surface of recent breaks is bright white, densely compact, and crystalline in texture. These surfaces are marked at intervals with prominent, opaque extrusions of an ocher-colored secondary material with a [glossary:laminar] structure.

The object is heavily encrusted with rootlets. The roots have been somewhat thinned but are still visible within the folds and on the undersides of the drapery (fig. 4.29). The remaining roots are very well adhered to the stone matrix.

During the current examination, a resinous, amber-colored accretion was observed on the back, behind the proper right shoulder. This accretion was removed and found to be a proteinaceous material, most likely glue. Several ocher-colored accretions are present on the base.

Conservation History

There is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini