The Roman god Mars (generally equated with the Greek Ares) is commonly viewed as a god of war, yet his domain was significantly broader and far more complex. In his martial role, Mars was not only a warrior but also a guardian, who had long provided protection to the Italic peoples. Although the earliest sanctuaries of Mars were commonly situated on the edges of civilization, where enemies lurked, his cult was also found within Rome itself from its beginnings. Mars also appears to have been a god of agriculture and vegetation, associated with purifying the land, warding off illness, and protecting crops, livestock, and the household. Thus, for the Romans, whose lives centered on agricultural work and military service from early times, Mars was one of the oldest and “most authentically Roman” of all of the deities of their pantheon, and he held a central position in Roman religion.

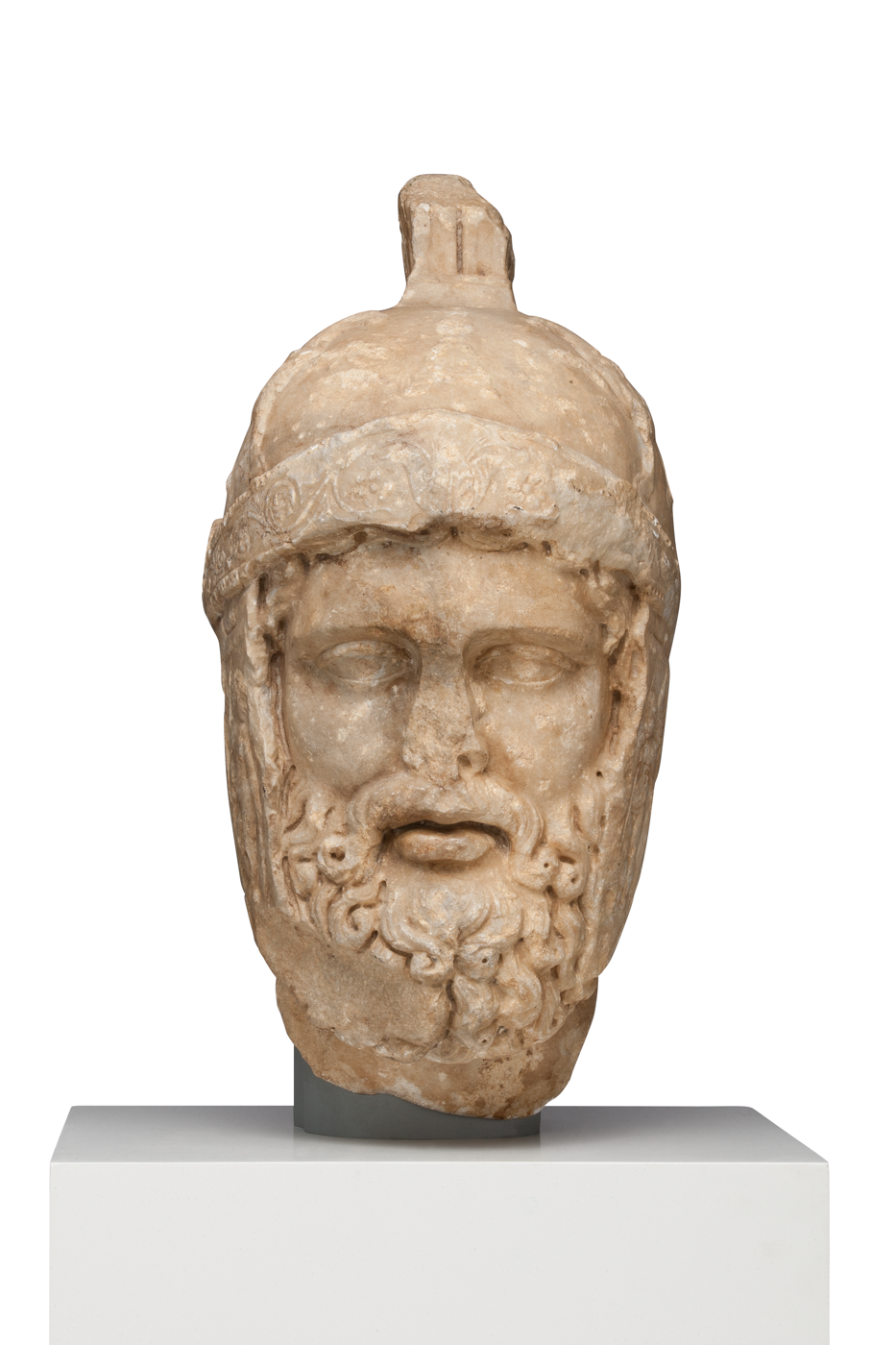

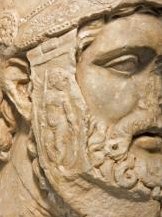

This over-life-size head, which is made of Parian marble from Lakkoi, on the island of Paros, once belonged to a much larger statue of Mars. Based on the dimensions of the head, the original statue is estimated to have measured approximately 4.5 meters (14 feet 9 inches) in height. Here Mars is shown with a broad, idealized face, which is unlined except for the pronounced nasolabial folds that suggest his maturity. The large eyes, set below a sharply defined brow bone, would have looked down at the viewer below (fig. 4.18). The full lips are slightly parted—a characteristic feature of Mars’s iconography. A beard covering the lower half of the face is formed of waves that terminate in small curls with drilled centers. Over the forehead and at the temples are traces of similarly thick locks of hair that peek out from below the helmet.

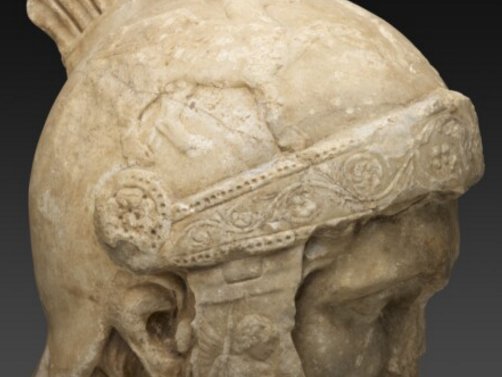

The helmet is a critical iconographic element in the representation of Mars as the god of war, and thus it is nearly always incorporated into his image. While he is frequently shown wearing a Corinthian helmet (see fig. 10.10 below), here his helmet is of the Attic type and includes a crest composed of either feathers or hair, a frontlet, and hinged cheekpieces (bucculae). The Attic crested helmet is worn by Roman soldiers in numerous historical reliefs, such as one example that might depict members of the [glossary:Praetorian Guard] (fig. 10.41); it is also included in images of Mars.

Rich relief carvings adorn the helmet. A striding griffin appears in profile on each side of the bowl, with its wings and innermost front paw raised (fig. 8.36). The griffin is a companion of Nemesis (the goddess of vengeance), as well as the god Apollo (the patron deity of Emperor Augustus [r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14]); it is also employed in the iconography of Mars to evoke his avenging nature. The griffins flank a [glossary:thymiaterion], perhaps alluding to the eternal flame of Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth. This flame was protected by priestesses known as the Vestal Virgins, one of whom (Rhea Silvia) became the mother of Romulus, the founder and first king of Rome, through her union with Mars.

The frontlet, which is bordered on the top and bottom by a row of small, shallowly drilled holes, is decorated with an acanthus scroll (fig. 4.3), a motif occurring widely in Augustan art that suggests earthly abundance and the divine blessings of the gods who bestowed such prosperity. At either end of the frontlet is a rosette motif that sits just above the ear.

Finally, each of the hinged cheekpieces displays an image of Cupid, the god of love, carrying a spear and shield—two of the main attributes of Mars (fig. 8.37). Here they might refer to Mars’s sacred shields ([glossary:ancilia]) and spear (hasta)—the latter was often used as an aniconic representation of the god himself—which were housed at the shrine known as the sacrarium Martis in the Regia. In addition, the appearance of Cupid brings to mind Mars’s connection with Cupid’s mother, Venus, the Roman goddess of erotic love and sexuality (equivalent to the Greek Aphrodite), who was also associated with warfare and military victory. In contrast to the relief decoration on the front of the helmet, the back was left plain (fig. 4.4). This may mean that the statue was not intended to be seen from behind, and that it was placed in a niche or against a wall.

Mars Ultor: The Avenger

This type of hirsute, mature Mars, which is distinct from the often clean-shaven, youthful images of the god that were popular in the republican and imperial periods, was employed beginning in the Augustan period and was likely intended to emphasize two of the god’s most significant titles, the first of which is Ultor, “avenger.”

Mars’s importance increased considerably under Emperor Augustus, who sought to revitalize the old cults and restore existing temples that had declined throughout the Republic, while also founding priesthoods and constructing new temples. Mars gained further significance due to Augustus’s emphasis on the idea that the peace and tranquility of his [glossary:saeculum aureum] was made possible through dominance, war, and victory. This connection between war and peace was most prominently asserted in the monumental temple of Mars Ultor, the preeminent structure of the newly built Forum of Augustus. In 42 B.C., on the eve of the battle of Philippi, Augustus (at the time still known as Octavian) had vowed to build a temple to Mars Ultor in the event of his triumph, which would avenge the assassination of Julius Caesar, his great-uncle and adoptive father. The lavish, marble-clad—albeit incomplete—temple was dedicated in 2 B.C., providing the god with a home befitting his value to both the emperor and the empire.

Within the [glossary:cella] of the temple of Mars Ultor stood its cult statue. Although the statue is no longer extant, its appearance is evidenced through representations of the god in a variety of media, including marble statues and reliefs, bronze statuettes, coins, and terra-cotta lamps, as well as mosaics and wall paintings. The materials of the original statue are not known, but the sculpture could have been made of marble, multiple types of stone, gilt bronze, or even [glossary:chryselephantine], following the tradition of earlier Greek cult statues.

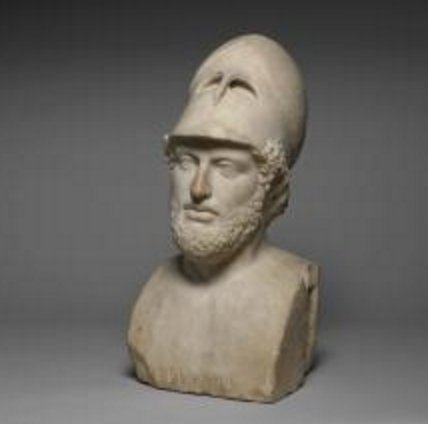

The prototype for the Roman cult statue of Mars Ultor—if one existed—is unknown. It has been suggested that the statue might have been inspired in part by an earlier Greek cult statue of Ares, but there is no material evidence to support this hypothesis. It has also been argued that its model might have been a statuary type depicting a bearded male subject wearing an Attic helmet, which might reflect either an earlier image of Mars or a Greek [glossary:strategos] (see fig. 10.42). Alternatively, it has been proposed that the Mars Ultor statuary type was a classicizing creation—evoking both Pheidian and late classical models—that was developed anew during the Augustan age. Regardless of the origins of the cult statue, the surviving images that are believed to allude to its appearance typically show the god in full armor, including a [glossary:cuirass], greaves (shin armor), and Corinthian helmet. He carries a spear in his upraised right hand and a shield at his left side. His thick, curly hair and similarly voluminous beard endow him with a mature visage.

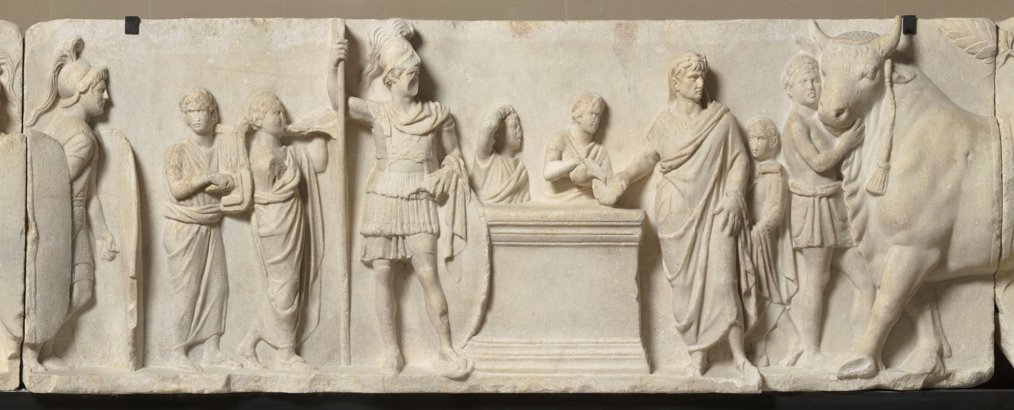

Bearded images of Mars are attested prior to the Augustan period, but they are rare. Mars was more frequently shown with a beardless, youthful face. For example, on the so-called altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus from the late second century B.C., a relief portraying the taking of the census depicts a clean-shaven, cuirassed Mars receiving the sacrifice performed at the conclusion of the event (fig. 4.6). In other cases, a beardless Mars appears with a nude (or largely nude) body—seen, for example, on the denarii issued to commemorate the return of the Parthian standards to Rome (see fig. 8.38).

Arguably the best surviving large-scale representation of Mars Ultor is found in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (fig. 4.7). Most often dated to the end of the first century A.D., this colossal sculpture (henceforth referred to as the Capitoline Mars) is thought to be a marble copy of the original Augustan cult statue. It was found in the Forum of Nerva (also known as the Forum Transitorium), where it might have served as a companion to the statue of Minerva (the Roman equivalent of the Greek Athena) in the forum’s temple to the goddess. Alternatively, it might have been a later replacement for the original Augustan statue in the temple of Mars Ultor. While it contains significant restorations to the body, certain features of the head, cuirass, and parts of the helmet are preserved and help to shed light on the iconography of the god in his role as avenger, military conqueror, and bringer of peace.

The head of the Capitoline Mars is distinguished by its full beard of luxuriant corkscrew curls, which are echoed in the locks that emerge from beneath his Corinthian helmet. The rich texture of the hair and beard provides a notable contrast to the generally smooth face, with its fixed expression and slightly open mouth. On the helmet, a [glossary:Pegasus] is depicted on each side of the bowl, alluding to the sacred horses of Mars, and perhaps also to the flying horses that are known to have adorned the pilaster capitals in the cella of the god’s temple. Additional imagery that could communicate the god’s avenging nature is found on the cuirass, which features a [glossary:gorgoneion] and pendant griffins flanking a thymiaterion. The motifs on the helmet and cuirass of the Capitoline Mars are found to varying degrees on both large- and small-scale representations of the god in his role as Ultor, although on smaller-scale objects the selection of motifs is often reduced or simplified.

The Chicago Mars differs from other images of Mars Ultor in terms of its helmet type and the motifs depicted. Moreover, among the examples that employ the Attic helmet, it is also unusual for cheekpieces to be included. However, the griffins on the helmet, the figure of Cupid carrying the spear and shield on the cheekpieces, and the dense, curly beard and thick, wavy hair together provide sufficient iconographic evidence to support the identification as a representation of the god in this guise.

Mars Pater: Progenitor and Protector

Mars’s hirsute appearance was also associated with the god’s second major title under Augustus, Pater, “father”—in the sense of progenitor and guardian—of the Romans. One of Rome’s main foundation myths held that Mars was the father of the twins Romulus and Remus—the former of whom became the city’s founder. The boys were born following the god’s union with Rhea Silvia, a Vestal Virgin and daughter of King Numitor of Alba Longa. According to one version of the myth, a prophecy foretold that Romulus and Remus would depose their great-uncle Amulius, who had gained power by overthrowing their grandfather, Numitor. Consequently, the infants were set on a litter in the flooding Tiber River and abandoned. After the waters miraculously receded, they were nursed by a she-wolf until their discovery by the shepherd Faustulus, who raised the boys with his wife. Upon reaching adulthood, Romulus and Remus learned of their origins and sought revenge by killing Amulius, after which they restored Numitor to power and set out to establish a city at the site of their salvation on the Tiber. Their conflicting opinions on where to locate their city led to a quarrel that resulted in Remus’s death at the hands of Romulus, who then founded Rome and became its first king. Mars, as the father of Romulus, became by extension the father and protector of the state.

In surviving Roman imagery, Mars’s paternal role is depicted most clearly in the relief panel on the northwest side of the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace). This monument commemorating Augustus’s pacification of the Roman Empire was voted by the Senate following his return from Gaul and Spain in 13 B.C. and was completed in 9 B.C. The relief panel incorporating Mars is generally thought to represent the moment at which the god and the shepherd Faustulus discover the she-wolf suckling the twins. Despite the poor preservation of the panel, Mars’s head has largely survived and exhibits notable similarities to the Chicago Mars (fig. 4.9). For example, the Ara Pacis Mars wears an Attic helmet, complete with a striding griffin on the bowl. He has a comparably idealized yet mature face that bears a calm expression, and a full beard of thick, albeit more simplified, curls surrounds his slightly open mouth. In the Ara Pacis relief, these facial features, in the context of the scene showing Mars guarding his sons, could allude to the god’s role as both father and protector.

This relief seems to have preceded the hirsute image of the god in the cult statue of the temple of Mars Ultor, which was dedicated seven years later, in 2 B.C. This suggests that the bearded, mature visage was viewed as a significant iconographic component in the representation of Mars as both Ultor and Pater during Augustus’s reign. In both roles, after all, he served as a guardian: first protecting his infant sons from harm, and thus allowing for the foundation of Rome, and thereafter preserving the state and the new Augustan order. For Augustus, this emphasis on Mars as Pater served an additional purpose: it legitimized his title of [glossary:pater patriae], which was granted by the Senate in 2 B.C. and highlighted his role as the protector and leader of the Roman state.

The bearded image of Mars (particularly with the Attic helmet) continued to be employed in the first and second centuries A.D. on other monumental reliefs, perhaps indicating its efficacy at conveying messages of protection and preservation. For example, a head of Mars wearing an Attic helmet, likely from an unknown monumental relief, resembles the Chicago head in some aspects (fig. 4.10). His beard comprises wavy locks ending in small curls, while his face, although unlined, exhibits a somewhat more intense expression due to his noticeably larger eyes. The Attic helmet is likewise adorned with heraldic griffins on either side of the bowl, and the frontlet similarly includes an acanthus scroll motif and is bordered by rows of small holes. The crest holder, however, takes the form of Romulus and Remus suckling from the she-wolf, directly referencing the god’s paternity and emphasizing his role as Pater.

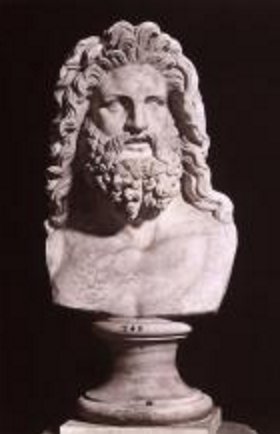

More broadly, the representation of Mars as a bearded god invites a comparison to the imagery of Jupiter (equivalent to the Greek Zeus), the supreme god of the Roman pantheon. Indeed, if shown without his helmet, the mature, hirsute Mars would bear a striking resemblance to the traditionally bearded, stern visage of Jupiter, as can be seen in a bust of Jupiter in Naples (fig. 10.43). While Mars was typically considered the second most important Roman god next to Jupiter, their growing visual similarities during the Augustan age were likely intended to impart a clear message of Mars’s increasing religious and political significance. Many of the key political, military, and social activities previously carried out at Rome’s oldest temple, the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, seem to have been shifted to the temple of Mars Ultor (or more broadly to the Forum of Augustus) during this period. For instance, the temple of Mars became the venue where the Senate met to declare war and to grant triumphs and where captured military standards were placed and dedicated to the god, demonstrating its centrality in Roman foreign affairs, particularly those related to war. As Mars surpassed Jupiter and assumed the role of sovereign god (at least to some degree), he in effect became pater omnipotens (almighty father) as well as divine avenger.

Mars and Venus as Divine Ancestors

Mars and Venus were viewed as consorts, much like their Greek counterparts, Ares and Aphrodite. They were also considered to be the divine ancestors of the Roman people—but through separate foundation myths. While Mars was the father of Romulus, Venus was held to be the mother of Aeneas, the Trojan hero who, following the destruction of Troy, led a small group of followers to settle in Italy. His son, Ascanius (also known as Iulus), founded and ruled the city of Alba Longa, where Romulus and Remus were later born, thus making Venus an ancestor of Rome’s royal line, and by extension of the Roman people. Moreover, the [glossary:gens] Iulia (Julian family), one of the oldest and most distinguished patrician families in Rome, also claimed their direct descent from Ascanius/Iulus (from whom they derived the name of their clan), making Venus their direct ancestor. The two myths were linked through the figure of Rhea Silvia: as the daughter of King Numitor of Alba Longa, she was the descendant of Aeneas and a member of the Julian family, but she was also mother to Mars’s twin sons. Hence, through these intertwined foundation stories, Mars and Venus were seen as the divine ancestors of all Romans, and they were believed to protect and sustain the Roman people as a whole. More specifically, “Mars guaranteed the Romans [glossary:virtus], while Venus granted fertility and prosperity.”

Under Augustus, significant emphasis was placed on the divine couple. As a member of the Julian line through his adoption by Julius Caesar, Augustus was able to claim descent from Venus and Mars. Such assertions helped to legitimize his rule by suggesting that his family line was favored by the gods. Consequently, Mars and Venus were featured prominently in some religious settings.

Following a remark by the Augustan poet Ovid, the two gods are thought to have been represented together in the temple of Mars Ultor. An early imperial relief from a public altar at Carthage may offer evidence of their appearance (fig. 4.5). Here a bearded Mars wearing a Corinthian helmet and cuirass is accompanied by a draped Venus; the infant Cupid stands at her feet and hands her a sword (presumably that of Mars). To the right of Mars is a partially nude male figure wearing a mantle wrapped about his hips, likely depicting the deified Julius Caesar. It has been argued that these figures were intended to portray statues (perhaps even the cult statues) from the temple’s sculptural program, rather than the deities themselves. Such statues would have complemented the others said to have been displayed in the temple and on its facade that highlighted the origins of Rome and the divine lineage of the Romans.

In the Carthage relief, the grouping of Mars, Venus, and Cupid is particularly significant, as it allegorically suggests the disarming of the war god and perhaps celebrates the period of peace that ensues after victory in battle, when weapons are no longer necessary. On the helmet of the Chicago Mars, the image of Cupid holding Mars’s weapons on the cheekpieces—a feature that is not attested in other comparable depictions of the god—conveys much the same message of victory, disarmament, and peace (fig. 10.44).

Display Contexts

The Art Institute’s Head of Mars was in all likelihood attached to a large-scale statuary body of the cuirassed type, as seen in the many other bearded, helmeted representations of the god. It is not known where this statue was displayed in antiquity. It might have been located in a religious sanctuary dedicated to the worship of Mars. If this was the case, it could have functioned either as a dedication placed within a sanctuary precinct, or perhaps as a cult statue erected in a temple’s cella. The motivation behind statuary dedications is rarely epigraphically or iconographically attested, but such works appear to have been offered following specific ritualized practices, such as making vows to the gods. Thus, statuary dedications were brought into the temple as part of a series of rites, subsequently functioning as points of focus for religious observances. Cult statues, which were placed within a temple’s cella and typically dedicated with the building itself, were simultaneously participants in cult and the central recipients of it—images to which all other dedications responded.

Among statues of gods placed within sanctuaries, no aesthetic parameters seem to have differentiated dedications from cult statues. Cult statues thus were not required to be over-life-size works made of extravagant materials, yet this was often the case. With regard to Head of Mars, the over-life-size proportions, along with the selection of fine Parian marble, support the possibility that the head might have belonged to a cult statue, although epigraphic and contextual evidence of such a function is lacking.

Alternatively, it is possible that the Chicago Mars appeared in a civic context in the sculptural assemblage of a major public building or monument. Large-scale structures including [glossary:thermae], gymnasia, and theaters, as well as [glossary:nymphaea], libraries, and city gates, frequently employed statues of deities, heroes, and mythological subjects in programmatic displays in order to convey a specific thematic message about the function of the space. In many cases, the connection between a statue and its context is readily apparent. In other cases, the motive for choosing a particular subject cannot be easily inferred on the basis of how the space was used. A large-scale statue of Mars reflecting the Ultor/Pater type is attested in a theater in Vicenza in northern Italy, indicating that the type was considered appropriate for placement in major civic structures, although the thematic link is unclear.

Regardless of the statue’s function and display context, based on the motifs of the helmet and the bearded visage—features that are suggestive of Mars’s appearance when represented as Ultor and Pater—it seems quite likely that it could have been located in or near Rome. As previously noted, these titles were emphasized initially under Augustus and were reflected in monuments such as the temple of Mars Ultor and the Ara Pacis. Comparable images of Mars have also been found on numerous monumental reliefs from Rome dated to the first and second centuries A.D., an indication of the basic type’s significance to the way Mars was portrayed in the capital.

To be sure, large-scale marble statues thought to depict a cuirassed Mars with weapons have been found outside of Rome as well, albeit infrequently. For example, a marble statue in Cherchell in northern Algeria has been identified as an image of the god because it includes his characteristic armor, weapons, and pose, raising the possibility that Head of Mars might have belonged to an over-life-size statue in a provincial setting. Indeed, Mars was venerated widely in the provinces, in part due to the dissemination of his cult through the Roman army. In the Cherchell example, however, the ancient head is missing, making it impossible to compare facial features or helmet iconography. Thus, while Head of Mars could have been sited in the provinces, the greater number of large-scale marble representations of the bearded, helmeted Mars in Rome and its environs—complete with iconography alluding to his titles of Ultor and Pater—supports the likelihood that it was displayed in or around the capital.

Conclusion

This over-life-size Head of Mars, with its bearded visage and Attic helmet, probably belonged to a larger (presumably cuirassed) statue that showed the god in his dual roles as Ultor and Pater. The iconography of his helmet, namely the heraldic griffins and the traditional shield and spear, evokes his title Ultor by suggesting his avenging nature. His thick and curly beard, combined with his calm expression, gives the god a mature, arguably more paternal appearance that evokes his title Pater. The remaining imagery on the helmet also reinforces this fatherly role, first through the motif of the thymiaterion, which could refer to Mars’s union with the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia, through which he became the progenitor of the Roman people, and second through the presence of Cupid, who clearly alludes to Venus, Mars’s consort and another divine ancestor of the Romans. While the iconography of the Chicago Mars closely resembles that of other images of the god as Ultor and Pater, it also diverges in some aspects, including the Attic helmet, which occurs less frequently than the Corinthian helmet, as well as the cheekpieces, which are typically omitted from examples that incorporate the Attic helmet. Yet, despite these variations, the subject is still clearly recognizable.

Given its over-life-size dimensions and creation in fine Parian marble, it is possible that the original statue was erected either in a religious sanctuary dedicated to Mars or in a civic context, where it could have been included in the sculptural assemblage of a large-scale building or monument. Since this head alone clearly emphasizes the god’s dual roles of Ultor and Pater, which were especially significant to the worship of Mars in the city of Rome, it seems reasonable to surmise that the full-length statue might have been displayed in or around the capital, offering a commanding image of one of the most important deities of the Roman pantheon.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object is a fragment of a monumental sculpture depicting the Roman god Mars (fig. 4.29). The fragment itself was carved from a single block of medium-grained, white marble that has been identified as Parian. The surface of the object is covered with toolmarks. The condition of and degree of loss to the neck preclude a full understanding of the means by which the head was connected to the rest of the sculpture in antiquity. No evidence of [glossary:polychromy] or gilding has been detected. Burial conditions have given the stone an overall red-orange tone, and further evidence of antiquity can be found in the abundance of root marks and earthen incrustations scattered across the surface, particularly in undercuts and deep recesses. Overall, the head is in stable condition; however, the object is fragmentary and was at some point, likely upon excavation, assembled and bonded. A number of lesser anomalies, together with a layer of surface soiling, give the object a somewhat compromised appearance, but despite this, even several conspicuous losses do little to detract from the figure’s imposing countenance. No written records of treatment accompany the object in either the conservation or the curatorial files.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The interior of the marble is a warm, bright white with several large crystal faces visible. Burial in a presumably iron-rich soil has given the exterior of the object an overall red-orange tone.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); apatite, Ca5(PO4)3(F,Cl,OH) (traces)

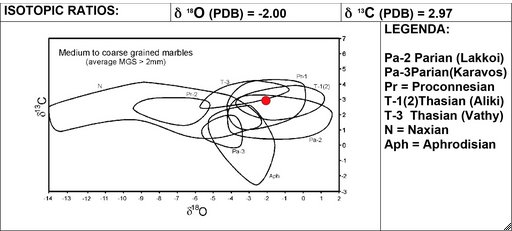

Petrographic Description

In order to obtain sufficient material for study, two samples were taken: the first, a chip roughly 0.6 cm square, was removed from an area of incipient [glossary:cleavage] on the back of the helmet on the proper right side, approximately 14.5 cm from the bottom; the second, a chip 0.9 cm high by 1.9 cm wide, was removed from the bottom edge of the front of the neck on the proper left side, approximately 7 cm from the center. The samples were then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the material was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining material was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: medium to coarse (average MGS greater than 2 fmm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 1.70 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic, slightly [glossary:strained]

Calcite boundaries: [glossary:embayed]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed average inter- and intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 4.31

Provenance

Marble type: Parian (marmor parium)

Quarry site: Lakkoi, Korodaki valley, on the island of Paros, Cyclades, Greece

The determination of the marble as Parian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 4.19

Fabrication

Method

The object is a fragment of a monumental sculpture. The existing fragment was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

The break edge along the neck has an irregular profile, and the simplest explanation for this is that the head was broken away without intent from a larger mass of stone. If the figure was carved from a single block of stone, the neck would have been a point of particular vulnerability and prone to damage or fracture. If the head was carved separately, it would have included a projection made up of the neck and possibly the collarbone, and it would in all probability have been finished with a [glossary:keyed] terminus or tenon meant for insertion into a cavity or socket. This extension of stone would also have been highly susceptible to impact and damage.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

In some areas, traces of early-stage carving can still be seen. Marks left by a very fine claw chisel are visible along the back and proper left side of the helmet (fig. 4.23). This is an area that, because of its position at the back of the sculpture and its height relative to the viewer, would not have been visible in antiquity and therefore did not require a pristine surface. The sculptor heightened the contrast in the areas of relief decoration on the surface of the helmet by incising lines around their perimeters with a flat chisel. Because of the distribution of losses in the relief carving, it is not always clear whether the sculptor incised the lines first before refining the design within them, or whether the lines were applied after the relief carving was complete. The shape of the relief and the incised line do not always correspond exactly, and in some instances the carving betrays a slip of the hand (see fig. 4.24). Fine rasp marks are visible over the rest of the helmet’s surface.

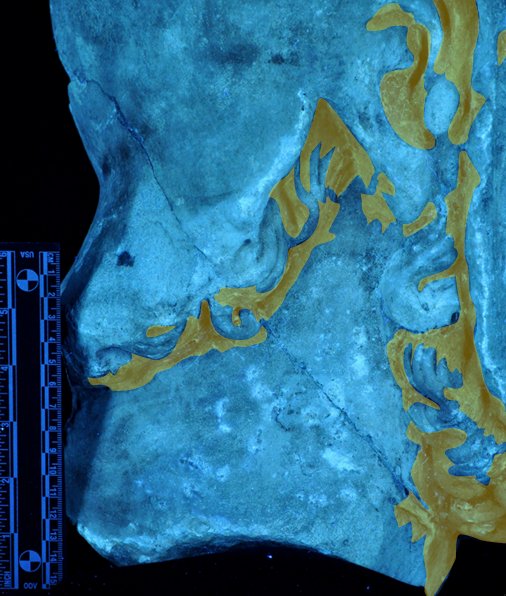

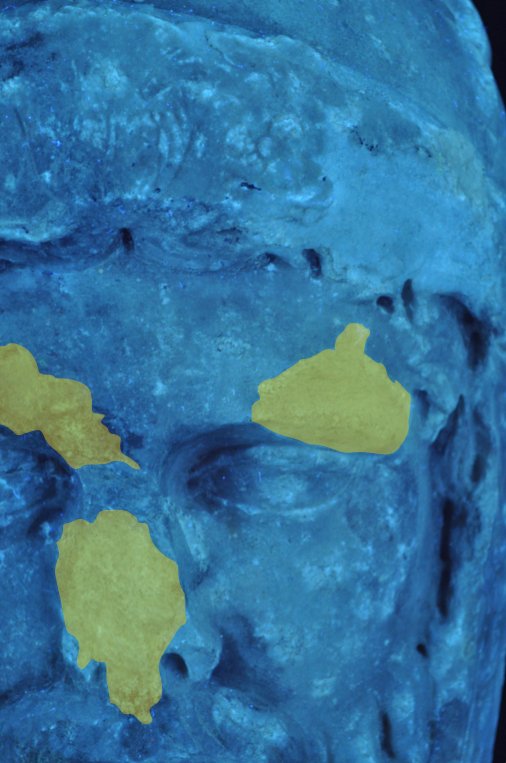

Extensive drill work can be seen in the execution of the beard, where the curls were delineated using a drill approximately 4.3 mm in diameter. Within a number of these features, particularly those in sheltered locations that would not have been readily apparent to the viewer, telltale holes following the line of carving reveal that the sculptor used a drill to pierce the stone at short intervals along the line of the shape he wished to render (see fig. 4.28). This network of pierced holes was then excavated by various means, using either a roundel or a channeling tool. To further emphasize the curls, the terminus of each was punctured with a drill approximately 2.9 mm in diameter (see fig. 4.35). A drill approximately 3.4 mm in diameter was used to create an elaborate pierced decoration around the frontlet of the helmet (fig. 4.20).

The crest on the helmet was also carved with a drill. But unlike the linear sequence of holes in the lines of the beard, the holes in the carved channels of the crest appear stacked or concentric (fig. 4.21). This topography suggests that the sculptor made use of the same 4.3 mm drill but employed the running drill technique. Traces of a rasp are also visible on the outer surfaces of the crest.

A pronounced, burnished surface on the lower lip suggests an original polish, which would have been applied using a slurry of an abrasive powder such as pumice. This area is in close proximity to a stone-based [glossary:fill], however, so it is also possible that the restorer’s polishing efforts carried over onto the original surface.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed remains of what appear to be deliberate black lines around the eyelids (fig. 4.22). A sample was taken from the area and analyzed, but the results were inconclusive.

No signs of gilding or other embellishments were observed.

Condition Summary

The object is fragmentary, with the primary break running diagonally down from the back edge of the helmet through the neck and terminating at the base of the chin. A network of additional breaks is visible throughout the crown of the head and the frontlet of the helmet. The crest of the helmet was at one point completely detached and has suffered marked associated losses of its own, visible at angles along the top surface, particularly in the front. The crest was detached from the helmet in a large wedge, as evidenced by the network of break edges extending diagonally away from the crest. Associated with this break is an additional crack on the proper right side of the helmet that extends diagonally down from the bottom edge of the crest to the top edge of the frontlet just above the temple. Most of the break lines show associated losses, some with significant associated fragments that have been readhered. On the back of the helmet, for instance, an ovoid fragment has been bonded into its correct position along the primary break edge, with losses still extant on either side of the fragment.

Additional cracks not associated with fracture are evident on the object’s surface. On the proper left side, a secondary crack is visible traveling through the neck below the primary break. Another crack exists on the back of the helmet running below the crest.

The sculpture has suffered several conspicuous losses. The nose is missing, with only the remains of the proper left nostril intact. Approximately one third of the beard on the proper right side of the face is missing; this loss extends into the bottom portion of the cheekpiece of the helmet. The bottom edge of the helmet has sustained losses along its entire length, with those in the back being the most severe. The topography of the bottom edge of the neck is highly irregular, with major losses evident along the entire circumference, also especially in the back. Much of the relief carving on the helmet exhibits losses: the griffin on the proper right side is missing a large portion of its body; losses are apparent on the griffin on the proper left side; and much of the relief decoration on the proper left side of the frontlet is no longer extant.

Lesser [glossary:spalls], lacunae, and scratches are distributed uniformly across the surface, along with many pits that exhibit a rough, granular texture. Numerous abrasions, which appear stark white in contrast with the red-orange surface coloration, are visible on the proper left side. Surface dirt and soiling are particularly prominent on the proper right side of the face.

Residues from the burial environment are apparent on the object’s surface, notably the uniform red-orange coloration, which often indicates an iron-rich soil. Clumps of earth are visible in many undercuts, and there are heavy root incrustations in the beard near the join with the neck (fig. 4.34). Root marks with a branching habit can be seen on the broken surface at the back of the neck (fig. 4.27). Scattered brown accretions are present throughout. Redeposited calcium with a reddish tinge can be found in the drilled decoration of the helmet (fig. 4.25).

Conservation History

There is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection.

At one point in the object’s history, likely upon excavation, the fragments were assembled and bonded with an unidentified adhesive that, where it is visible on the surface of the break edges, appears dark brown and to which dirt and dust have preferentially adhered. A second adhesive with a more modern appearance, like that of an [glossary:acrylic emulsion], seems to have been used on the breaks around the frontlet. This adhesive had slight gap-filling properties and can be seen proud of the surface in many areas along the break edges. Many of these adhesive fills have since become detached from the surface and in the process have removed the red-orange surface coloration below, leaving white highlights around the area of repair (see fig. 4.32).

At some point, the object was restored rather skillfully using fills made of stone. These repairs were inserted in the nose, extending up into the brow of the proper right eye; along the brow above the proper left eye; and on the top surface of the bottom lip on the proper right side. With the exception of the restorations above the proper left eye and on the bottom lip, which remain in situ, these restorations have been removed. Remnants of the nose fill, however, remain adhered in what is likely a concavity behind the repair, and the portion of the nose fill that extended up into the brow also remains. The restorer chose a stone with a texture much finer than that of the original stone, and the carving process left behind a slightly open network of pores. Despite this difference in texture, the color match of the chosen stone, together with the high level of workmanship, renders these repairs almost invisible. The restorations are not readily apparent to the naked eye but are easily seen with the aid of ultraviolet radiation (fig. 4.33). Repairs were also made to surprisingly delicate areas: a small disk of stone can be seen overlying what is presumably a shallow spall on the proper right eyeball (fig. 8.40).

When the object is examined under ultraviolet radiation, the surface appears primarily a greenish yellow. The proper right side of the face, however, has a more purple appearance, suggesting that this side was exposed during burial or underwent a more aggressive surface cleaning at some point. Deep purple in the recesses of the beard indicates that whatever steps were taken to mitigate the earth and rootlets on that side of the face exposed quite a bit of new surface (fig. 4.26).

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini