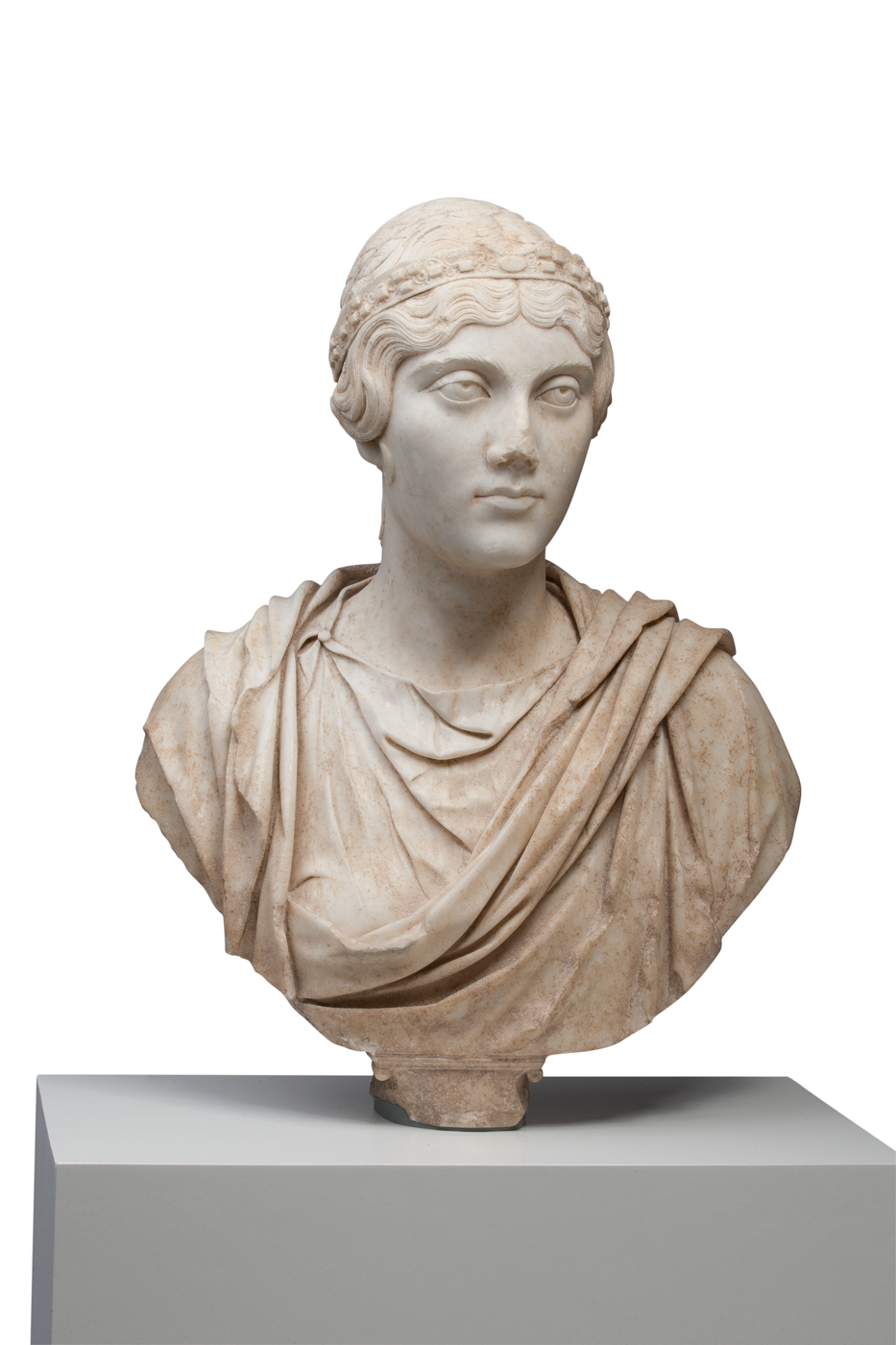

Cat. 8

Portrait Bust of a Woman

Mid-2nd century A.D.

Marble; 64.8 × 47.6 × 27.3 cm (25 1/2 × 18 3/4 × 10 3/4 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, restricted gifts of the Antiquarian Society in honor of Ian Wardropper, the Classical Art Society, Mr. and Mrs. Isak V. Gerson, James and Bonnie Pritchard and Mrs. Hugo Sonnenschein; Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Bro Fund; Katherine K. Adler, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Alexander in honor of Ian Wardropper, David Earle III, William A. and Renda H. Lederer Family, Chester D. Tripp and Jane B. Tripp Endowments, 2002.11

The icon of the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection of ancient art is a detail of this beautiful Roman portrait bust that captures two locks of hair curling sensuously on a young lady’s neck (fig. 4.30). Nothing is known about either the artist or the subject except for what the sculpture itself reveals: that the former was exceptionally talented, and the latter, with her elaborate hairstyle, luxurious garments, and bejeweled [glossary:diadem], was a woman of wealth and distinction.

The work was cut from a single block of finely grained, brightly sparkling white marble, which gradually developed a warm patina on its undisturbed surfaces. It depicts the sitter’s head, neck, shoulders, truncated upper arms, and thorax. Her upper body is clothed in a [glossary:chiton] and wrapped in a [glossary:himation], the latter’s surface retaining a high shine in places. Presumably some parts of the sculpture were painted. Below is a blank nameplate that once had volutes at its four corners; the lower two are now missing.

The back of the torso has been cut away save for a central vertical pillar with squared edges to support the weight of the head. Widest at the top, it tapers along its length and gradually broadens toward the base. Like others of its type, this bust was once raised on a flaring cylindrical foot known as a [glossary:socle]; separately carved, it is now missing. In the classification of Roman statuary, this type of sculpture is known as a freestanding portrait bust.

The front is remarkably well preserved except for the upper edge of the woman’s headdress, the tip of her nose, and the bottom of the nameplate. Additional areas of minimal and moderate loss include chips missing from the hair above her eyes, part of her right eyebrow, and edges of her clothing’s folds. However, the reverse is more extensively disfigured: there is an old break along the lower right edge, and significant damage along the left edge of the subject’s upper back and to the lower portion of the support pillar. This suggests that the bust fell face down, its nose probably damaged in the process, and that it laid largely undisturbed in a protected setting for centuries until an unfortunate encounter with modern tools or equipment marred the surface with fresh gashes and gouges.

The sculptor portrayed an individual with a solemn expression and aristocratic bearing. She has a smooth complexion, slender face, high cheekbones, and an elegant nose. Nascent folds extend from the outer edges of her hollowed nostrils to the deep corners of her closed mouth. A wide, shallow groove runs vertically from the base of her nose to the middle of her upper lip, which projects slightly over the lower, fuller one. Her chin is firm, the line of her jaw is taut, and three very subtle rolls of flesh encircle her slender neck. Although hair covers most of her ears, their visible rims, lobes, and bowls were sculpted with considerable attention to anatomical accuracy.

The subject turns her head slightly left. Incised brows follow the contour of her upper eye sockets, joining at the top of her nose in an asymmetrical cluster. The heavy, almost sleepy upper lids of her large, slightly protruding eyes overlap the upper rim of her incised irises, and the lines of their outer edges and deep creases extend well beyond the join of the lower lids. The pupils are round except for a very shallow semicircle of stone suspended from their top edges, perhaps to grant a lifelike glint; the rest of the pupil may have been painted in black. Incision separates the eyeballs from the soft tissue of their inner corners. A narrow space between the irises and lower eyelids indicates that the woman’s gaze is directed slightly upward, away from the viewer.

Together with her almond-shaped eyes and individually incised brows, the subject’s heavy upper eyelids are an immediately recognizable feature of many portraits carved during the Antonine Period (A.D. 138–193), and especially of those depicting Faustina the Elder (A.D. c. 97–140), her daughter Faustina the Younger (A.D. 130–175), her nephew and son-in-law Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 121–180), and her grandson Commodus (A.D. 161–192). Yet despite a strong resemblance to three generations of the Antonine dynasty (see fig. 8.36, fig. 4.3, fig. 8.37, fig. 4.4), the woman depicted here has not been recognized in other marbles or on coins; although she may have been a member of the extended imperial family, for now she remains nameless.

Regardless, the date of her portrait can be determined by her coiffure; apparently a keen observer of imperial trends, the subject devoted considerable time and resources to ensuring that her hair was arranged in a fashionable way. The turn of her head provides a tantalizing glimpse of an extravagant hairstyle. Framing her face are wavy locks meticulously incised to evoke individual strands. Flowing tresses are combed to the back, where they are woven into a number of long flat braids of varying widths. All of the plaits except for one are wound into a heavy, five-tiered bun that extends from the crown down the back of her head. Just above the hairs finely incised into the nape of the neck rises a long, similarly flat plait, its tip tucked into the bun’s top coil. To either side, shorter locks have slipped loose; carved in a combination of incision and low relief, they curl freely along the woman’s neck.

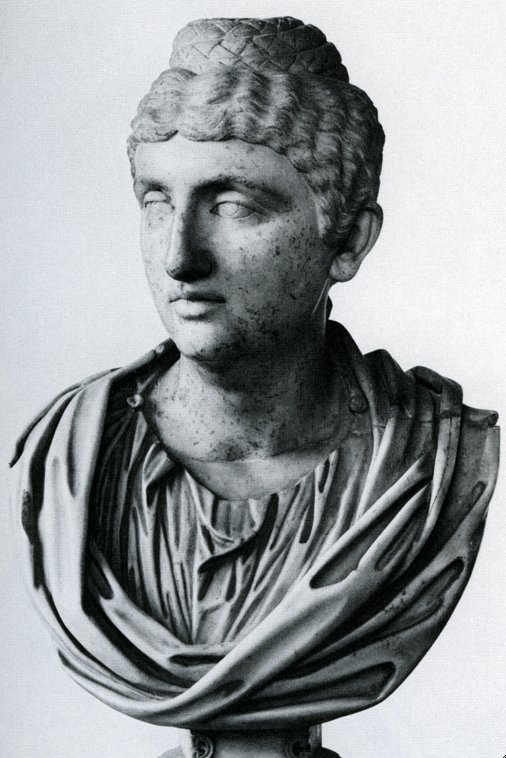

The inspiration for this particular hairstyle is the so-called Schlichten Bildnistypus, or “simple portrait type,” of the matronly Faustina the Elder, which is featured on portraits that were probably carved during her short time as empress and [glossary:Augusta] (A.D. 138–140). In these portrayals her long locks are brushed back, gathered in two thick bundles of braids, and raised to the top of her head, where they are wound into a bun. When viewed from the front, the formation of braids has a conical shape that has earned it the nickname the “tower coiffure.” This simple portrait type is especially well represented by a bust in the Capitoline Museum, Rome (fig. 8.38) and another in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (fig. 8.36).

Royal trendsetters inspired private women, whose portraits of varying quality and size reveal that they adapted, rather than merely copied, imperial hairstyles to suit their individual circumstances. For example, a variant of the tower coiffure is found on a somewhat later portrait of an anonymous girl in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, which features two long locks of twisted hair encircling the base of her high mound of braids (fig. 4.5). Another modified version of the hairstyle appears on a portrait in the Capitoline Museum, again depicting an unidentified woman. Her hair is similarly parted in the center and drawn to the back, although it is unclear how her tresses came to be plaited into the braids coiled on the top of her head. However, a single braid here again rises from her neck to the top of the bun in a manner analogous to that seen on the Art Institute’s sculpture. In both of these portraits, the front edge of the tower formation does not extend as far forward as it does in the simple portrait type of Faustina the Elder.

Yet, in terms of its overall form, the Art Institute’s bust has more in common with its Hadrianic antecedents than with other busts of the Antonine period. A pair of portrait busts currently loaned by the Dubroff family to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York—the one depicting Sabina (A.D. 83–136/7), wife of Emperor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117—138), and the other perhaps Sabina’s older sister Matidia the Younger (A.D. 85–after 161)—together illustrate the trend toward representing a more expansive section of the subject’s upper body, which began during Hadrian’s reign in the late first to early second centuries (fig. 8.39, fig. 4.6) and which is subsequently also seen on the Art Institute’s portrait bust. Although covered by a himation, the shoulders, truncated upper arms, and lower chest of these busts retain a strong physical presence and together create the impression that the work is actually a section of a draped, full-length statue. Furthermore, by the height of the Antonine period in the mid-second century, the style of female portrait bust took yet another novel turn: the naturalistic drapery characteristic of the late Hadrianic and early Antonine periods was largely replaced by a swirling mantle that at times completely obscures the body beneath it. That the Art Institute’s example features the earlier style of drapery suggests that it was made before this new trend was widely accepted. Certainly it is the heir of the aesthetic standards of the Hadrianic period.

Although female members of affluent Roman families attired themselves in a variety of fabrics and colors, their position in society governed their dress code, which limited their freedom to explore new styles of clothing in the same way that they did coiffures. For this reason, this subject’s dress provides clues about her status. As mentioned earlier, she wears a lightly pleated Greek chiton, or type of [glossary:tunic]. This is represented as being made from diaphanous cloth—perhaps very fine linen, exorbitantly expensive imported silk, or a luxurious blend of the two; to emphasize its sheerness, the neckline is so thinly carved that light transmits through the marble by her throat. Below, delicately curving folds zigzag down the center of her chest, while others emanate from the single fastener of her gap-sleeved garment, which is positioned near the right collarbone. Draped around her shoulders is a wide rectangular himation with thick, deeply cut folds suggesting plush fabric, perhaps wool or imported cotton. One end of the garment emerges from under her right arm, drops down to expose the gentle swell of her breast, and rises diagonally across her body; there it covers her left shoulder, wraps around her neck, and cascades in thick folds in front of her right shoulder. Mantles of the same style appear in a similar way in two late Hadrianic busts: a portrait of Sabina in the Museo Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome, and a portrait (probably depicting Matidia the Younger) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Such luxurious garments, together with the woman’s elaborate hairstyle, suggest that the sitter was the wife or relative of a member of the ruling elite—whether from the imperial family itself or from an aristocratic clan. She no doubt had at her disposal highly competent cosmeticians, hairdressers, jewelers, and seamstresses to ensure that when she appeared in public she looked the part, exemplifying the virtues of dignity, integrity, and moral restraint expected of upper-class Roman women.

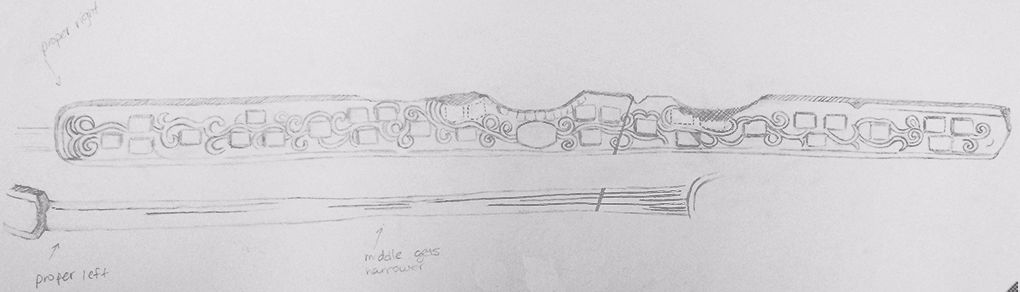

The most fascinating feature of this portrait bust is the striking gem-encrusted diadem encircling the subject’s head. Careful examination suggests that the piece on which it was based comprised two distinct parts that joined behind the ears. The first, seen around the back of her head, is a tubular element scored along its length with parallel lines, perhaps emulating the texture of cord or fabric. The second, the forepart of the headband, is a long flat rectangular strap with raised edges suggesting a frame. The upper edge widens ever so slightly above the wearer’s eyes and then curves downward, its contour embellished with a dozen or so round-edged elements, possibly representing pearls or a length of beaded wire.

Within the frame, the surface of the stone is slightly concave. It is uncertain whether this was an actual feature of the original diadem or the result of the sculptor reducing the height of the marble in order to fashion the low-relief decoration. At the very center is an ellipse with slightly truncated ends and a flat upper surface, which probably depicts a cabochon garnet. It appears to be threaded onto fine-gauge metal wire formed into coiling tendrils that trail along the band’s surface until they terminate at each end in pairs of outwardly turned spirals. The wires curve among thirty rectangles clustered in groups of three alternating with a single one, fifteen to a side, except for two now missing above the subject’s right eye. Their shape suggests that they represent emeralds, which were commonly set in this manner in antiquity (fig. 4.8).

Depictions of headbands made of precious metal with inlaid or bezel-set jewels and filigree decoration are well attested on sculptures of women from the ancient Mediterranean region. However, the paucity of surviving examples with elaborate decoration makes it difficult to draw conclusions about their appearance. For example, did the headband depicted in this portrait feature wires and gems—perhaps box set—attached to a backdrop of sheet gold that was affixed within its frame? Or was it an airy openwork piece, one without a backdrop, showcasing colorful gemstones threaded onto meandering gold filaments that were anchored to the frame at various points?

A rare piece of jewelry fashioned in such an openwork technique has been on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago since 2005 (fig. 4.9). Reportedly discovered in Syria, this impressive bracelet has on both sides a border formed from three thick strands of gold. Between them is a serpentine vine of gold wires interspersed with clusters of grapes or berries and box-set leaves of red and green glass (or semiprecious stones) that are affixed to the frame in several places. Although this work is thought to have been made around 200–150 B.C., several centuries before the Art Institute’s portrait bust was carved, it provides an impression of the visual impact of the glittering gold and bejeweled diadem that the sculptor was presumably attempting to represent. This marble version may have been painted yellow to imitate gold, with other colors added for the gemstones.

The role of jewelry as a symbol of rank and status in antiquity is well established, and this subject’s diadem provides a crucial clue to her social identity. Although portraits of empresses and their female relatives sometimes include various types of headdress, private citizens of the Latin West were less likely to wear these than their contemporaries in the prosperous Greek East (including modern Greece, Turkey, Syria, the Levant, and Egypt), where the tradition of civic benefaction conferred special honors for men and women. If this lady funded a major municipal project or underwrote costly entertainment for her community, for instance, she might have been rewarded for her largesse with the right to wear such a magnificent diadem while officiating at the dedication of her project or presiding over athletic or other contests. Perhaps members of her family also commissioned a master sculptor to create this magnificent portrait for display alongside those of other relatives in their home’s atrium or the family mausoleum.

In addition to the style of her clothing and the diadem, other reasons to think this portrait comes from the Greek East range from such subjective elements as the appearance of the marble, the shape of the bust supports, and the articulation of the eyes to another that is speculative but nevertheless worth mentioning. When the Art Institute acquired the work in 2002, this author was informed that, according to a former seller, it had belonged to the late Hans von Aulock during the 1950s and 1960s. Director of the Istanbul branch of Dresdner Bank when Turkey broke relations with the Third Reich in 1944, Aulock was interned in the small central Anatolian town of Eskişehir. There, with time on his hands, he visited the local bazaars, where he was introduced to—and developed an all-consuming passion for—ancient coins. The seller reported that Aulock owned other sculptures. It is interesting, but perhaps coincidental, that one of them, a portrait head of a male, is likewise Antonine in date and wears an honorary wreath. If, in fact, Aulock did once own this portrait bust, one wonders if the two works are related.

This fascinating work presents numerous avenues of investigation, a few of which have been briefly explored here. In bringing to the public’s attention the foundational research conducted by Klaus Fittschen well over a decade ago, it is this author’s intention to pay homage to that renowned scholar of Roman portraiture and his mastery of the subject, his breadth of knowledge, and his passion for sharing both.

Karen Manchester

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This portrait bust of a noblewoman exemplifies the height of workmanship in marble statuary of the Antonine period (fig. 4.29). Meticulously carved from a single block of fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Carrara, the portrait demonstrates virtuoso handling in the minute rendering of each strand of hair, in the high degree of surface polish across the front of the [glossary:chiton], and in the elaborate swirl of drapery in the [glossary:himation]. The level of finish, together with the heavy incrustation of rootlets from burial, makes it almost impossible to discern any traces of the tools used to fabricate the bust. The stone itself is in exceptional condition, exhibiting noticeable losses only on the verso. There are smaller losses on the recto, particularly to the end of the nose, but they do not detract from the portrait’s regal and imposing countenance. Examination of the surface has revealed some traces of what was likely a highly nuanced and painterly style of [glossary:polychromy]. Traces of earth pigments were found in numerous areas on the head and face, but it is in the sheltered groove behind the [glossary:diadem] that the most compelling evidence of decorative embellishment remains. The object was extensively examined at the time of its acquisition, and the present study constitutes both an expansion and a refinement of those efforts. While in the collection of the Art Institute, the object has received one documented treatment to ameliorate some of the heavier, more unsightly burial incrustations and to refine a preexisting [glossary:fill] at the front of the himation.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The exterior surface of the marble exhibits a warm, ivory tone overall, but the interior is bright white. Heavy root incrustation gives the stone a reddish-brown aspect. In scattered locations across the surface, small black particles or inclusions are visible.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant)

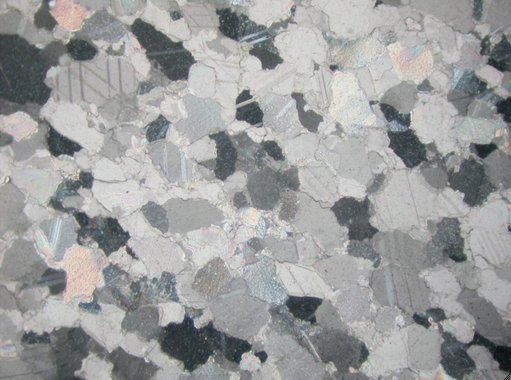

Petrographic Description

A sample roughly 0.8 cm high by 2 cm wide was removed from an area of damage on the verso, at the bottom proper right corner of the pillar, approximately 1.9 cm up from the bottom edge. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.72 mm

Fabric: quasi-homeoblastic mosaic, slightly [glossary:lineated]

Calcite boundaries: curved

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 4.22

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed little to no decohesion and confirmed the presence of a brown patina of [glossary:micritic] composition.

Provenance

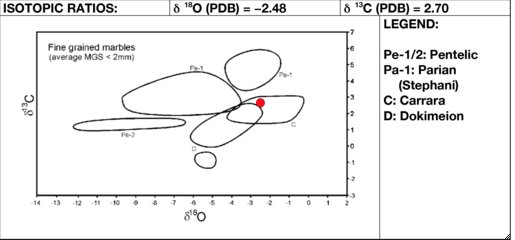

Marble type: Carrara (marmor lunense)

Quarry site: Carrara region, Apuan Alps, Italy

The determination of the marble as Carrara was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 4.23

Fabrication

Method

The object was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Owing to the high degree of surface finish and the heavy incrustation of rootlets, very few traces of toolmarks are visible.

In some places, such as on the top edge of the chiton below the neck and along the folds of the himation surrounding the proper right breast, the surface has been polished to such a degree that the stone appears almost translucent (fig. 4.35). This level of polish would have been realized with a slurry of an abrasive powder such as pumice.

On the verso, the undercut areas behind the chest and shoulders adjacent to the central pillar are uniformly covered with earth and rootlets. Nevertheless, marks left by a fine claw chisel or a coarse scraper are visible through this coating, particularly on the proper left side (fig. 4.34). The fact that the pillar and adjacent areas were not finished to the same degree as the rest of the sculpture suggests that, although the object was intended to be viewed in the round, this area was not an immediate focal point.

Many details were painstakingly rendered with the edge of a flat chisel held at an oblique angle to the stone, such as the strands of hair around the face and neck (fig. 8.40 and fig. 4.20), the braided hair on top of the head (fig. 4.28), the diadem, the line between the lips, and the eyebrows and irises (fig. 4.24). The lines emphasizing the outer margins of the nameplate were also made using a flat chisel.

Where the diadem is free of root incrustation, traces of a very fine rasp can be seen on the faces and sides of the gems (fig. 4.32). Traces of a fine rasp are also visible in the crevice behind the diadem where it meets the head on the proper right side. The fact that this crevice was left more unfinished than the surrounding area suggests that the bust was intended to be presented at slightly higher than eye level.

The presence of small crescents at the tops of the pupils indicates that they were carved with a roundel, rather than having been drilled (see fig. 4.25).

In contrast, a small drill, approximately 2.5 mm in diameter, was used to render the inside corners of the eyes (see fig. 4.27) and to pierce the volutes at the corners of the nameplate. A drill of indeterminate diameter would have been used to create the nostrils and the holes in the ears.

While the root incrustation has obscured the telltale circular depressions at the ends of the lines of carving in the drapery, examination of other Roman sculpture suggests that the primary contours would have been delineated with a drill and fully finished with a roundel or channeling tool.

The philtrum would have been made with a roundel.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed some traces of polychromy.

Red ocher was identified in numerous areas: at the proper right corner of the mouth, between the lips on the proper right side, on the third braid from the top on the proper right side of the head, and within the crevice behind the diadem. Red ocher was a particularly common pigment in the Roman era, but, since it is an iron-rich earth pigment, its presence could also be attributable to the burial environment. To conclude that the figure was polychromed based on the presence of a single earth pigment, without evidence of a corresponding binding medium, would be unduly optimistic.

However, the sample taken from the channel behind the diadem also contained yellow ocher and carbon black. The presence of multiple pigments, all of which were staples of the Roman palette, lends greater weight to the theory that the bust was once painted. Recent developments in the examination and analysis of ancient sculpture and the results of countless technical studies on the subject have begun to shed light on the tremendous skill and finesse employed by artists in this medium. Rather than the flat areas of monochrome paint assumed to have colored Greek sculptures, multilayered applications of paint seem to have been standard practice at least since Hellenistic times and were employed in an endeavor to impart the greatest possible three-dimensionality to the surface. The use of multiple pigments, including yellow and red, to enhance the carving of the hair has been observed on several Roman portraits. Black has also been found painted directly onto the surface of marbles as an underlayer to enhance the impression of depth and to assist in demarcating areas of transition, such as between the face and the hair.

The high degree of polish sometimes found on ancient marbles, such as that seen on this bust, has been presented as an argument against polychromy. Why would the sculptor go to such lengths to polish the stone surface, only to have it obscured by paint? Behind this position is a long-standing belief in some scholarly circles, originating in the eighteenth century, that the desired aesthetic in antiquity was a stark white, shiny surface. A further assumption has been that marbles were colored using single layers of paint, yielding a flat, opaque, monochrome finish. Increasing evidence of more complex uses of polychromy now makes clear that sculptors and painters worked in concert to create a sophisticated impression. A delicate application of paint to a highly polished, almost translucent surface would have the capacity to transmit light so as to imbue the portrait with an almost ethereal quality.

Examination and analysis also revealed traces of modern pigments and binders around the eyes. Along the bottom lid of the proper right eye, close to the tear duct, a blue-green coloration was found, along with a synthetic adhesive. This pigment was identified as Pigment Green 7, and the adhesive was identified as polyvinyl acetate. On the proper right eye, within the crease of the upper eyelid and on the outer edge of the fleshy portion of the eye below the brow, a red-orange pigment and trace elements of an organic material, possibly an adhesive, were found. This color was identified as Pigment Orange 34.

No traces of gilding were found.

Condition Summary

The stone itself is in a remarkable state of preservation, and the object is for the most part free of structural damage.

There are, however, significant losses on the verso: at the top edge of the himation and the central portion of the back edge, as well as on the lower portion of the central pillar. A line of deep gouges indicative of excavation-related impact connects these two areas of damage and suggests that the object was face down during burial (fig. 4.21). Additional large [glossary:spalls] and lacunae are visible on the verso along the bottom edge of the undercut area behind the chest on the proper left side.

Damage to the recto is not as severe. Noticeable spalls and losses are present throughout the folds of the himation, particularly in the lower section on the proper left side and along the vertical fold on the proper right side. A rather conspicuous loss to the primary sweep of fabric below the proper right breast has been restored at least twice. The current repair is extremely well camouflaged and is apparent only under ultraviolet radiation (fig. 4.31 and fig. 4.19). A crack extending vertically above a loss to the himation adjacent to the proper left collarbone appears stable. The tip of the figure’s nose is missing, although the nostrils remain visible. On the proper right side, the diadem has been marred somewhat by abrasion and chipping, resulting in a loss of textural detail.

The object was broken between the nameplate and the [glossary:socle], resulting in a truncated edge at the bottom around which numerous associated losses are apparent, particularly at the bottom proper right corner. The lower volutes of the nameplate were also casualties of this damage. Along the proper left side, the volute appears to have broken off cleanly—the break edge in that area corresponds closely to what would have been the original outline of the volute at that point. The upper volutes of the nameplate remain intact. Damage to the nameplate notwithstanding, it is clear that the bust was carved separately from the socle. The bottom surface of the object is finished rather than broken and displays some evidence of what appears to be [glossary:keying]. This suggests that the bust and the socle were intended to be joined by means of a mortar, although a mechanical fitting such as a pin might also have been employed. The burial deposits present on this bottom surface, identical in character to those on the rest of the marble, confirm that the bust was buried without the socle attached.

Other minor losses to the face include chips on the proper right eyelid and brow and a shallow spall on the skin between the two. Two chips with associated [glossary:exfoliation] and granularity are present on either side of the bottom edges of the hair framing the forehead. Another chip exists at the center of the chiton along the top edge; surprisingly, perhaps owing to the high polish in this area, this flaw is barely noticeable. Elsewhere both deep and shallow scratches are evident; some of these appear recent when examined under ultraviolet radiation, and some have been toned with watercolor. The face also exhibits various superficial pits and small holes with associated [glossary:bruising].

The object is heavily encrusted with rootlets and earth—providing desirable evidence of antiquity—predominantly in a uniform, heavy distribution on the verso but also on the himation on the proper left side of the recto. The braids at the back of the head and the strands of hair at the nape of the neck also show heavy coverage. There has been no attempt to reduce the incrustation via mechanical or chemical means. This is fortunate, because such efforts could have obliterated fine details, such as the exquisite carving of the hair. The rootlets have a strong, red-brown coloration, suggesting a very iron-rich burial environment. Indeed, small accretions that are presumed to be iron oxide can be seen on the undercut areas of the verso, particularly on the proper right side (fig. 4.26).

Within deep folds and crevices, especially at the bottom edge of the proper right side and along the folds of the himation against the back of the neck, the rootlets are embedded in a white, chalky matrix (fig. 4.33). Several of these areas were sampled, and analysis revealed the presence of calcite, gypsum, quartz, and silicates. There are at least two possible explanations for the presence of this material.

When buried, marble artifacts are subject to slightly acidic groundwater. The moisture surrounds the object and leaches calcium ions into solution. During cyclical changes in the moisture level within the soil, the calcium ions are reprecipitated on the surface of the stone. This redeposited calcium, often described as a micritic calcite layer, has an opaque, floury appearance and is much less dense than the original stone. It is often subtly shaded in accordance with the character and constituents of the soil. In this case, the silicates and gypsum would be constituents of the burial environment.

A second possibility, given that the bust appears to have borne some amount of polychromy, is that the painter applied a substratum in selected areas in preparation for applying the colorants. The material used for this purpose would presumably have been a lime-based gesso or plaster composed of [glossary:lime] putty and various aggregates, in particular silicates, such as quartz sand, or fine marble dust. The painter could also have used a traditional gesso made of calcium carbonate bound with a protein-based adhesive such as a hide glue.

The sample removed from the channel behind the diadem also contained traces of oxalates. Some researchers attribute the presence of oxalates on ancient sculpture to human intervention, through the application either of polychromy or of coatings intended to protect and preserve the stone.

Conservation History

After an exhaustive examination upon acquisition in 2002, the bust underwent treatment with the goal of making minor aesthetic improvements, particularly to the incrustations of rootlets in the lower part of the himation. The bust was swab cleaned under a stereomicroscope using aqueous methods in order to remove superficial grime; particular attention was paid to the nostrils and ears, which contained a great deal of earth. Excessive and unsightly rootlets and earth were reduced mechanically with the aid of buffered aqueous poultices. At this time, the earlier repair to the front fold of the himation was reversed by mechanical action with the aid of successive solvent poultices. The loss was newly restored using a synthetic acrylic filler that was then retouched with acrylic resin paints.

Prior to its arrival at the museum, it is likely that the object received some degree of cleaning, if cursory, as evidenced by the slightly dull sheen of the face. While it does not, strictly speaking, appear overcleaned, the face retains very little of the compact, somewhat more burnished surface seen on the lower half of the bust.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini

Selected References

Art Institute of Chicago, “Acquisitions,” Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 2001–2002 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2002), p. 11.

“Handsome Acquisitions,” Antiquarian Society Newsletter (2002), p. 5 (ill.).

Ghenete Zelleke, “David Adler, Benefactor and Trustee,” in David Adler, Architect: The Elements of Style, ed. Martha Thorne (Yale University Press, 2002), pp. 54–55 (ill.), 66.

Ghenete Zelleke, “An Embarrassment of Riches: Fifteen Years of European Decorative Arts,” in “Gifts Beyond Measure: The Antiquarian Society and European Decorative Arts, 1987–2002,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 28, 2 (2002), pp. 87–89, cat. 55 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “New Acquisition,” News and Events: The Art Institute of Chicago (Jan.–Feb. 2003), p. 5 (ill.).

Karen Manchester, “Bust of a Woman,” in “Notable Acquisitions at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 29, 2 (2003), pp. 54–55 (ill.), 95.

Karen Manchester, Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), pp. 11; 33; 39, n. 134; 96–97, cat. 22 (ill.); 113.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago: Pocketguide (Art Institute of Chicago, 2013), p. 19, fig. 36.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

Visible Light

Normal-light and raking-light overalls: Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens

Normal-light and raking-light macrophotography: Nikon D5000 with an AF Micro NIKKOR 60 mm 1:2.8 D lens

Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens and a Kodak Wratten 2E filter

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

High-Resolution Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Canon EOS1D with a PECA 918 lens and a B+W 420 (2E) filter pack. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Visible light microscopy: Zeiss OPMI-6 stereomicroscope fitted with a Nikon D5000 camera body

Petrographic and thin-section analysis: Leitz DMRXP polarizing microscope equipped with a Leica Wild MPS-52 camera head

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry

Finnigan MAT 5000 mass spectrometer

X-Ray Diffraction

PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with vertical goniometer (CuKα/Ni at 40 kV, 20 mA)

Fourier Transform Infrared Microspectroscopy (FTIR)

Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrophotometer with a Hyperion 2000 Automated FTIR microscope fitted with a nitrogen-cooled MCT detector

Raman Microspectroscopy

Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope (laser excitation lines λ0 = 532 nm, 632.8 nm, 785.7 nm)