Cat. 7

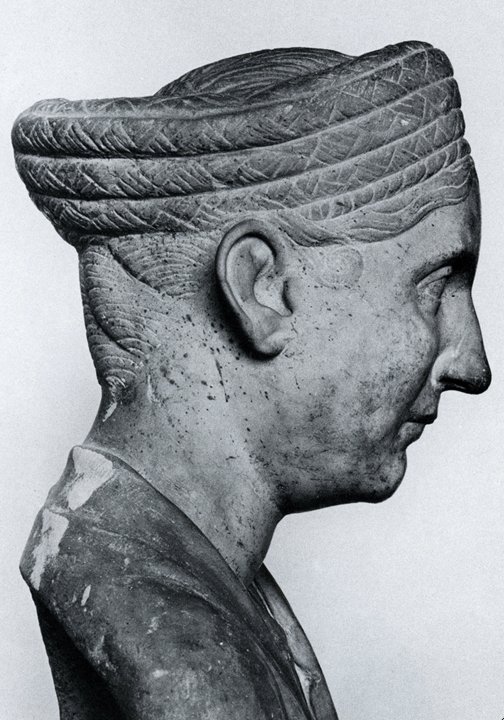

Portrait Head of a Young Woman

A.D. 130/40

Roman

Marble; 22 × 18 × 20.6 cm (8 7/8 × 7 × 8 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Edward E. Ayer Endowment in memory of Charles L. Hutchinson, 1960.64

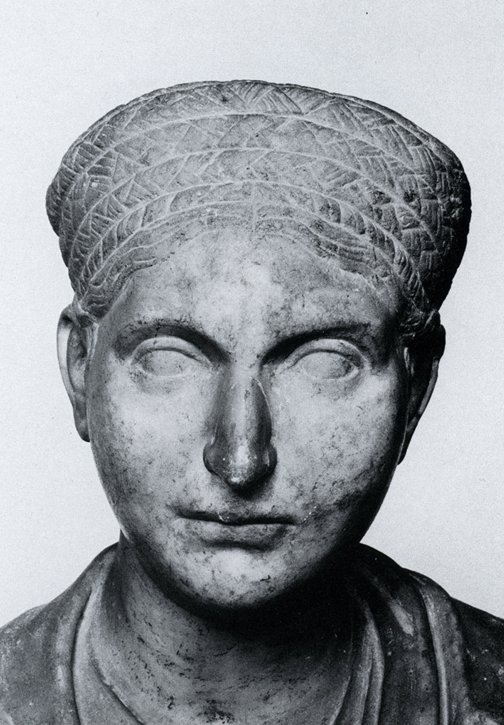

Made of creamy white Dokimeion marble from ancient Phrygia in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), this slightly under life-size portrait depicts an elegant young woman, perhaps in her late teens or early twenties. Although her face is idealized, her youth is emphasized by the sensitive modeling of her smooth, rounded face and high cheekbones. The wide-set, almond-shaped eyes with heavy lids have incised irises truncated at the top by the upper eyelids, as well as shallowly drilled, round pupils (fig. 7.1). The subject’s forward gaze contributes to her serene, remote expression. The lightly incised eyebrows stand out from the supraorbital ridges, and the small, bow-shaped mouth and rounded chin were sculpted with exquisite skill. The lower part of the nose is partially broken away.

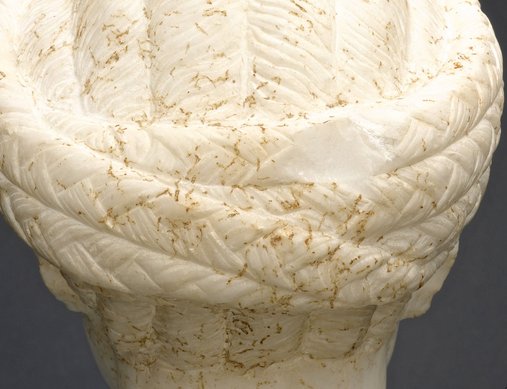

The subject’s smooth facial features contrast with the painstakingly textured carving of the elaborate hairstyle. Over the forehead, wavy locks are parted at the center and pulled back, leaving the ears uncovered (fig. 7.2). Above these locks is a narrow, twisted band of fabric or hair that extends to the back of the head. Three tiers of delicately carved plaits encircle the top of the head and tuck into one another in the front and back (fig. 7.3). This hairstyle, which was popular in the early to mid-second century A.D., has been described by scholars as the “turban coiffure.” Here it is completed with rows of waves arranged in equal segments that cover the crown of the head and the base of the skull. These waves evoke the so-called melon coiffure, a style developed in the early Hellenistic period that involved segments of hair running from the front to the back of the head, as seen in an early fourth-century B.C. grave monument in Los Angeles (fig. 7.4). In the Chicago portrait, the segments are carved in a heavier, more cursory fashion than the strands of hair within the braids, suggesting that the back of the head might not have been intended to be clearly visible to the viewer (fig. 7.5). Below the head are the remains of the neck, an indication that the portrait was once part of a statuary body or bust.

Since its arrival at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1960, scholars have debated the date of Portrait Head of a Young Woman. Exhibiting sculptural elements that were employed initially in the second century A.D. and again in the fourth, the portrait has been assigned to dates in both centuries. Stylistic analyses of the subject’s hairstyle and, to a lesser extent, her facial features have been the focus of the arguments regarding the date of this work. A review of the evidence that has been marshaled in support each of these positions, along with some new observations, has led to the current dating of the sculpture to approximately A.D. 130/40.

A Second-Century Date

Since the 1960s, roughly half of the scholars who have studied this portrait head have argued for a date in the second-century A.D. These claims have been based primarily on the hairstyle, which, as previously noted, has been identified as an example of the second-century turban coiffure. Characterized by a series of narrow braids that encircle the upper part of the head, this style is thought to have developed in part out of the elaborate female hairstyles of the Flavian (A.D. 69–96) and Trajanic (A.D. 98–117) periods, which frequently included a coil of braids at the back of the head. Whereas this braided feature often took the form of a small bun in the Flavian period, it expanded into a much larger “nest” in the Trajanic period, as seen in a portrait that might depict the deified Matidia (A.D. 68–119) (fig. 7.6), the mother of the empress Sabina. The turban coiffure was worn by private women in the Trajanic period and was especially popular in the Hadrianic period (A.D. 117–38), but it might have been worn into the early part of the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93). Although imperial women are known to have worn variations on the style, there are no extant portraits that clearly represent an empress wearing it.

The hairstyle depicted in Portrait Head of a Young Woman bears a clear resemblance to the turban coiffures represented in a number of second-century female portraits. Significant attention was paid to the accurate representation of women’s hairstyles in Roman portraiture, no doubt in part due to the association of artfully styled hair with cultus. Numerous variations on this basic coiffure have been identified, perhaps resulting from sitters’ individual preferences.

A close comparison to the hairstyle of the Chicago portrait is found in an early Hadrianic bust of a woman in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (fig. 7.7). The subject wears an arrangement of neatly parted waves over the forehead, surmounted by a thin, twisted band of hair or fabric marked by short, diagonal lines, above which sits a turban comprising several rows of braids. Additionally, the hair on the top and back of the head displays melon-coiffure-like waves similar to those of the Chicago portrait (fig. 7.8). In both sculptures the crown of the head is clearly visible above the turban, although in the Chicago work a larger portion of it is seen due to the slightly lower placement of the braids at the back of the head. Despite the similarities of the two hairstyles, the carving of the Chicago portrait’s coiffure is of notably higher quality, as evidenced by the graceful rendering of the individual strands of hair in the braids and locks over the forehead. In contrast, the details of the Capitoline portrait’s coiffure are substantially harder and more linear throughout.

The Chicago portrait’s facial features, especially the eyes and eyebrows, are also thought to lend some support to a second-century date. In Roman portraits, the articulation of the eyes through the drilling of the pupils and the incising of the irises appeared as a stylistic feature in the Hadrianic period, around A.D. 130, after which it became a common component of the sculptural repertoire, thus offering a terminus post quem for this work. It has been suggested that the treatment of the eyes in the Chicago portrait, with their nearly circular irises that terminate at the lower edge of the upper eyelid, along with the drilled pupils, is characteristic of the second century. Moreover, the heavy upper eyelids that extend past the outside corners of the lower lids are associated particularly with Antonine portraiture. Finally, the eyebrows, which are distinguished by prominent supraorbital ridges, reflect a slightly softened version of the more sharply faceted treatment of the eyebrows that appears in numerous Trajanic and Hadrianic examples, a feature that is thought to have died out during the Antonine period.

Comparable elements are found in a portrait bust of a woman named Bilia from the ancient city of Apollonia in the Roman province of Macedonia (in modern-day Albania) (fig. 7.9). Much like the subject of the Chicago portrait, this young woman, who also wears an elaborate turban coiffure, is shown with heavy-lidded, deep-set, almond-shaped eyes; large pupils that appear to be nearly circular in form; and prominent eyebrows, complete with delicately incised hairs. Although the subject gazes to her right rather than to the front, both likenesses are characterized by a calm, somewhat distant gaze.

Although the findspot of the Chicago portrait is unknown, certain aspects of the eyes, in particular the round pupils, might be evidence for an origin in the Greek East. This, when considered in light of the marble’s origin in Asia Minor, makes it tempting to speculate that the work might have been created in the eastern part of the Roman Empire. On the other hand, is also possible that the marble was exported and carved elsewhere; indeed, Dokimeion marble was known to be exported to Rome for use in statuary.

Regardless of where the portrait was created, the rendering of the eyes and other facial features appears to support a second-century date, specifically after A.D. 130, when the articulation of the pupils and irises became a common feature, and likely by the early part of the Antonine period, given the association of the heavy upper lids with the portraits of this era. Taking into account the additional evidence of the turban hairstyle, which was most popular during the Hadrianic period but is not widely attested in Antonine portraiture, it seems probable that this portrait was created between A.D. 130 and 140.

A Fourth-Century Date

Portrait Head of a Young Woman has also been dated to the fourth century A.D., albeit to different imperial reigns within that epoch. Scholars who have taken this position have suggested that, like a number of other female portraits assigned to the same period, the Chicago work is a product of a late antique revival, in which Emperor Constantine (r. A.D. 306–37) and his successors looked to the styles of earlier, favored dynasties for inspiration. However, many of the stylistically closest examples that have been assigned to the fourth (and in some cases fifth) century are marked by debates analogous to that about the dating of the Chicago portrait. Consequently, such portraits in fact offer no secure grounds in support of a late antique date. While comparisons might be made to more firmly dated portraits from the fourth century, this endeavor is complicated by two factors: a considerably smaller number of portraits was produced in late antiquity, and extant examples have been infrequently found in securely datable contexts. Nevertheless, based on the limited parallels that do remain, there seem to be notable differences between the turban coiffures favored in the second century and the version of the hairstyle that was popular two centuries later.

In support of an early Constantinian date for the Chicago portrait, Cornelius C. Vermeule argued that the hairstyle of this sculpture resembles that worn by Constantia (after A.D. 293–c. 330), the half sister of Emperor Constantine, in her posthumous numismatic portrait of A.D. 330. Although the details are difficult to discern due to its small scale, this commemorative coin type clearly depicts Constantia wearing a thick braid that encircles her head but does not fully cover it (see fig. 7.10). In this regard, it is similar to the turban coiffure of the Chicago portrait, although the latter comprises three narrow braids rather than one thick one. The comparison to this coin type was the sole support for Vermeule’s identification of the subject of the Chicago portrait as Constantia in 1960. His interpretation was accepted soon after by Michael Milkovich, George M. A. Hanfmann, and James D. Breckenridge; subsequently the subject was identified more generally as a woman of the Constantinian court.

Constantia’s coiffure in her numismatic portrait more closely resembles a hairstyle seen in some securely dated fourth-century portraits in the round that is formed by one or two thick plaits encircling the head, often extending down to the nape of the neck. Described as the “Zopfkranzfrisur” (braided crown hairstyle), this coiffure is seen in a seated statue with a fourth-century portrait that is thought to depict Helena (c. A.D. 250–330), the mother of Emperor Constantine, in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (fig. 7.11). Here the turban is composed of two wide braids, the individual strands of which are cursorily worked, in contrast to the finely carved individual hairs of the braids in the Chicago portrait.

An even closer comparison to the numismatic portrait of Constantia, which illustrates the clear distinction between late antique examples of the turban coiffure and those of the second century, is found in an early fourth-century portrait of a woman from Fulda, Germany, in the Museum Schloss Fasanerie (fig. 7.12). In this sculpture, three thick braids encircle the head, wrapping from the top of the head to the base of the skull in a nearly vertical orientation rather than horizontally around the crown. Tongue-shaped locks formed by flattened ringlets cover the forehead, fully conceal the ears, and extend relatively low on the back of the neck, creating a heavy, almost helmetlike style.

Based on these comparisons, it is evident that such late antique hairstyles, although incorporating one or more braids encircling the head, are nevertheless distinct from the second-century turban coiffure as represented in numerous portraits dated securely to that period. The delicate and elegant hairstyle of the Chicago portrait clearly has more in common with the second-century than the fourth-century examples. While it is unclear whether the late antique coiffures intentionally evoked this earlier style, the fact that the basic form of a turban of braids was repeatedly used in numerous portraits in both centuries seems to suggest that it might have held some general significance, as will be addressed below.

Scholars arguing for a fourth-century date have also called attention to certain aspects of the portrait’s facial features, namely the size of the eyes and the subject’s fixed, forward gaze. In late antique portraiture, the eyes are often enlarged, at times unnaturally so. When combined with an intense gaze, such eyes are thought to convey a sense of greater expressivity.

The eyes of the Chicago portrait have frequently been described as “large.” On closer inspection, however, it is apparent that they are proportional to the face as a whole; rather, it is the pupils that appear somewhat generously sized. It is perhaps due to the size of the pupils that the subject has been described as having a “visionary gaze” or a “heavenward glance” of the type often associated with late antique portraits. Still, the eyes are not characterized by the same enlarged proportions seen in some fourth-century examples, such as a portrait thought to depict Fausta (A.D. 289–326), the wife of Constantine, in the Musée du Louvre (fig. 7.13). In this sculpture, the subject’s heavy eyebrows, which nearly meet at the bridge of the nose, frame oversize, wide-set eyes. Although the eyes similarly include nearly circular irises and large, shallowly drilled pupils, here the large size of the eyes as a whole clearly distinguishes them from those of Portrait Head of a Young Woman. The “late antique gaze” that some have read into the latter may therefore owe more to a subjective interpretation of the emotional communication of the work than to the sculptor’s treatment of the facial features.

Bente Kiilerich argued that the face of the Chicago portrait might have been reworked in late antiquity, given what she saw as the fourth-century rendering of the eyes, along with the soft treatment of the surface and the precision of the carving. If the face was recarved, one might expect the hairstyle (provided that it was preserved) to be disproportionately large. However, examination of the portrait suggests that the proportions of the face are appropriate to the head as a whole. Furthermore, recarved eyes often appear very deeply set and unnaturally large, which is not the case here. It therefore seems most probable that the entire portrait, including the eyes, the rest of the facial features, and the hairstyle, were carved in the second century.

The Turban Coiffure as a Symbol of Virtue

As noted above, the turban coiffure’s characteristic arrangement of plaits encircling the head appears to have developed in part out of the smaller bun or the more sizable nest of braids at the back of the head that was featured in earlier Flavian and Trajanic hairstyles, which also included diadem-like toupets or crests of hair over the forehead (see fig. 7.6). It has been argued that, rather than being simply an elaboration upon the braided features of these earlier styles, the turban coiffure might have been intentionally created to communicate a distinct message.

Numerous scholars have observed that the turban coiffure resembles the hairstyle depicted in portraits of Roman priestesses, particularly the headdresses of the Vestal Virgins, the high-ranking priestesses of Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth. Recently, Molly M. Lindner has explored this connection, arguing that private women in Italy of nonelite status developed the turban coiffure to emulate the infula that the Vestals wrapped around their heads (see fig. 7.14). Viewed as a sign of sanctitas (holiness, inviolability, and sacredness), the infula was also worn by other Roman priests and priestesses, suppliants seeking pardon or protection, and sacrificial victims. According to Lindner, following the increased emphasis on morality (especially that of women) under the emperors Domitian (r. A.D. 81–96) and Trajan, nonelite women sought to imitate the Vestals in order to demonstrate their own adherence to moral standards, devotion to the gods, and embodiment of sanctitas (by the second century, sanctitas had become synonymous with the virtue of castitas—chastity, viewed broadly in the context of purity). To a lesser extent, the turban coiffure might also have evoked the distinctive hairstyle the Vestals wore beneath the infula, known as the seni crines (generally translated as “six tressed”), which involved rows of braids wrapped around the head. This style was worn by both Vestals and Roman brides as a symbol of their castitas, here specifically referring to their virginity. For Roman matrons, the allusion to the seni crines might instead have suggested the associations of castitas with marital fidelity.

Lindner further proposed that the turban coiffure was soon adopted by Roman women of elite (but not imperial) status, some of whom were priestesses of other cults. Priestesses gained considerable prominence in their local communities, and in some cases they were honored with portraits in life and in death, which might have incorporated the turban coiffure in order to suggest the infula of the Vestals. The association of this hairstyle with portraits of women of priestly (but non-Vestal) status is evident in an over-life-size, second-century portrait of an elderly priestess in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which shows her wearing a turban of five braids that decrease in width as they proceed from her forehead upward; below, the locks over the forehead are parted in the center and brushed to the sides of the head (fig. 7.15). The subject’s engagement in a religious act is implied by the palla drawn over her head as a veil; she is identified as a priestess because she is depicted in the act of burning incense, a rare occurrence in Roman portraiture. This portrait, which was the only sculpture found in a vaulted tomb in Pozzuoli in Campania, Italy, was undoubtedly a lavish and costly commemoration that alluded to the subject’s elevated status and presumably also her significant public role.

Based on the use of the turban coiffure in the Chicago portrait, Evelyn B. Harrison hypothesized that it might represent a priestess. This hypothesis cannot be verified, due to the absence of the portrait’s statuary body or bust and any accompanying inscription, as well as a lack of information regarding the context in which it was found. Regardless of the subject’s social standing or potential priestly role, it seems reasonable to suppose that her hairstyle of neatly wrapped braids helped communicate a message about her character. Although the motivations behind the development and popularity of the turban coiffure are still not entirely clear, its associations with the headdresses and hairstyles of esteemed women of high virtue, most notably the Vestal Virgins, suggest that it may have been intended to convey specific ideas about the subject, perhaps emphasizing her morality, modesty, and chastity.

Conclusion

Portrait Head of a Young Woman is characterized by a hairstyle and facial features that have long been thought to support a date in either the second or the fourth century A.D. Based on the evidence examined here, the work most likely dates to the second century A.D., specifically to A.D. 130/40. The turban hairstyle can be confidently dated to the second century on the basis of its resemblance to the coiffures of numerous portraits made in the Hadrianic period, many of which have been dated according to other stylistic features, including the articulation (or lack thereof) of the eyes. The drilled pupils and incised irises of the Chicago portrait indicate a date after around A.D. 130, while other aspects of the eyes, such as the heavy eyelids, are characteristic of Antonine portraiture, suggesting that it was made during the transition from the Hadrianic to the Antonine style. Given the general similarities between the turban coiffure and the headdresses and hairstyles worn by women known for their virtue, particularly the Vestal Virgins, it is possible that the subject’s elegantly braided tresses projected a comparable image of her virtuous nature.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object is a fragment of a portrait bust or statue depicting a young woman. The fragment was carved from a single block of exceedingly fine-grained, white marble, marked by exceptional translucency and brilliance, that has been identified as Dokimeion (fig. 7.16). A variety of toolmarks are visible across the surface. No evidence of polychromy or gilding has been detected. Burial conditions have given the stone a slight ocher tone overall, and further evidence of antiquity can be found in the abundance of root marks distributed over the surface, particularly in the braids on the back of the head. As a whole the head is in stable condition; however, it has suffered a number of noticeable losses. Documentation in the curatorial and conservation files indicates that the object has undergone various surface treatments, generally of an aesthetic nature, in particular to mitigate a once-heavier incrustation of rootlets.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is a warm, bright white with a slightly ocher hue that is due to the presence of surface deposits in carved areas. In highly polished areas, the translucency of the marble is readily apparent. Vertical striations and veins are visible throughout.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (traces)

Petrographic Description

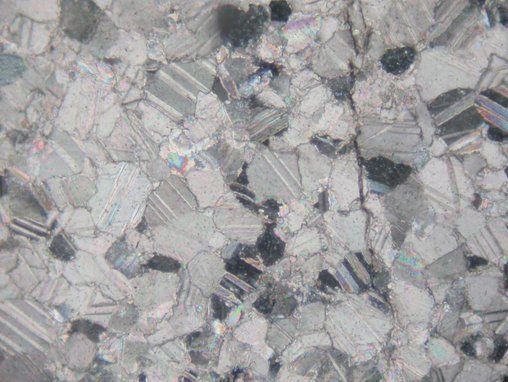

A sample roughly 2.1 cm high by 1.6 cm wide was removed from an area of existing loss at the base of the neck on the proper right side. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.24 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: embayed

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some intercrystalline decohesion and confirmed the presence of traces of micritic protolith.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 7.17

Provenance

Marble type: Dokimeion (marmor docimenum)

Quarry site: Dokimeion, near modern-day İscehisar, Afyonkarahisar Province, Turkey

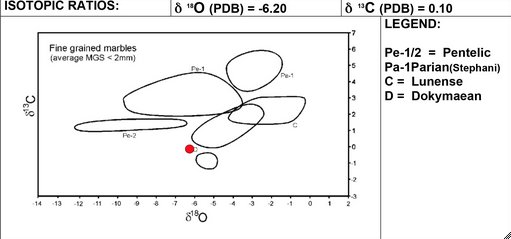

The determination of the marble as Dokimeion was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 7.18

Fabrication

Method

The head is a fragment of a portrait bust or statue. The existing fragment was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

The break edge along the neck has a somewhat flat but nonetheless irregular profile, and the simplest explanation for its topography is that the head was broken away without intent from a larger mass of stone. If the portrait was originally a bust, it was in all probability carved from a single block of stone, and the neck would have been a point of particular vulnerability, prone to damage or fracture. If the head was carved separately to be included in a larger sculpture, it would likely have included a projection made up of the neck and perhaps the collarbone, and it would have been finished with a keyed terminus or tenon meant for insertion into a cavity or socket. This extension of stone would also have been highly susceptible to impact and damage. It is also possible that the head was removed purposefully. A deep gouge extends across the surface of the break edge from the front of the neck toward the back on the proper right side, near an area of damage toward the front of the neck. It is possible that this gouge is the result of a percussive blow intended to separate the head from the stone below. While it is impossible to say for certain exactly what happened to the head, it is clear, based on the presence of rootlets on the break edge of the neck, that it was broken prior to burial.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Drills of varying sizes were used to create the nostrils, vestiges of which remain visible in the damaged end of the nose; the pupils of the eyes; and the front edge of the proper left ear, as evidenced by the circular depressions at the ends of the carved line (fig. 7.19). At the inside corners of the eyes, a drill approximately 1.75 mm in diameter was used to make tear ducts, increasing the naturalism of the portrait and drawing attention to the eyes.

The sculptor used a flat chisel to carve the irises. The proper left iris is somewhat irregular in shape, which may betray a slip of the sculptor’s hand (fig. 7.20). A very fine flat chisel was employed to delineate the many strands of hair and the braids that are wound around the head. To achieve this fine detail, the sculptor used the edge of the tool, held at an angle to the stone. The sculptor appears to have taken much less care in the execution of the waves of hair below the turban at the nape of the neck. This more perfunctory handling of the carving is particularly noticeable directly behind the ears (see fig. 7.21). This suggests that, although the object was intended to be viewed in the round, this area was not a particular focal point.

Traces of a rasp are visible on the back of the neck (fig. 7.22), a roughness that contrasts with the high level of finish on the face. This provides further evidence that this area of the sculpture was not expected to be noticed. Encrusting rootlets overlying the rasp marks indicate their presence prior to burial.

The philtrum was carved with a roundel (fig. 7.23).

The marble on the face is highly polished, an effect that would have been realized using a slurry of an abrasive powder such as pumice.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The sculpture has sustained several conspicuous losses. Most notably, the end of the nose is missing, and laminar cleavage, vertically oriented in line with the veins, is visible in association with the fracture. The back halves of both ears are also missing. There is a large, ovoid spall, with a smaller lacuna adjacent to it, on the bottom proper right edge of the neck. A lesser but still significant area of damage can be seen on the front edge of the neck. Residues from the burial environment in the form of red-brown material are present on the surface of this loss. There is a sizable loss to the topmost braid on the back of the head.

Elsewhere minor chips, spalls, and lacunae are in evidence, particularly throughout the hair. There is a gouge with associated bruising and friable material on the middle braid on the proper left side of the head. A small chip is present on the outside edge of the bottom proper left eyelid. A spall is visible nearby on the proper left cheekbone.

Root incrustation—desirable evidence of antiquity—can be seen overall, particularly in the braids on the back of the head and in the hair at the nape of the neck (fig. 7.24).

Extremely fine scratches and abrasions are present across the surface of the face. These may be the result of efforts to remove burial incrustations. When the object is examined under ultraviolet radiation, the extent of this scratching is all the more apparent (fig. 7.25).

A white, chalky material, likely the remains of a plaster support, is present on the surface of the break edge of the neck. A shiny substance, perhaps from a previous intervention, is visible on the face of the large spall at the base of the neck on the proper right side.

Conservation History

A 1964 condition report in the Conservation Department files, documenting the application of a spray coating of a synthetic resin consolidant, references a previous cleaning, although no date or details of the prior intervention are supplied. Additional documentation in the curatorial object file reveals that the object was cleaned again in 1976 using an aqueous solution with added detergent. In 1981 further refinements to these cleaning efforts were performed, this time with some amount of mechanical cleaning of the encrusting rootlets. Undated collection photographs in the curatorial object file demonstrate that the head was previously much more heavily encrusted with rootlets and that the base of the neck once bore a plaster support, but it is difficult to construct a time line for the removal of these features based on the existing documentation.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini

Exhibition History

Worcester (Mass.) Art Museum, Roman Portraits: A Loan Exhibition of Roman Sculpture and Coins from the First Century B.C. through the Fourth Century A.D., Apr. 6–May 14, 1961, cat. 34 (ill.).

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Roman and Barbarians, Dec. 17, 1976–Feb. 27, 1977, cat. 118 (ill.).

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century, Nov. 19, 1977–Feb. 12, 1978, cat. 268 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Featuring Faces, May 23, 1986–Mar. 25, 1987, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Sculpture from the Classical Collection, Sept. 1, 1987–Aug. 31, 1988, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Classical Art from the Permanent Collection, Feb. 1989–Feb. 17, 1990, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Private Taste in Ancient Rome: Selections from Chicago Collections, Mar. 3, 1990–Sept. 16, 1990, cat. 7.

New Haven, Conn., Yale University Art Gallery, I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, June 6–Dec. 1, 1996; San Antonio Museum of Art, Jan. 3–Mar. 2, 1997; Raleigh, North Carolina Museum of Art, Apr. 6–June 15, 1997, cat. 128 (ill.).

Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture, Everyday Life in Byzantium, Oct. 21, 2001–Jan. 10, 2002, cat. 464.

Selected References

John Maxon, “Report of the Director of Fine Arts,” in Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 1959–1960 (Art Institute of Chicago, 1960), p. 14.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Two Masterpieces of Athenian Sculpture,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 54, 5 (Dec. 1960), pp. 6–10; p. 8 (ill.).

Michael Milkovich, Roman Portraits: A Loan Exhibition of Roman Sculpture and Coins from the First Century B.C. through the Fourth Century A.D., April 6–May 14, 1961, exh. cat. (Worcester Art Museum, 1961), pp. 76–77, cat. 34 (ill.).

George Maxim Anossov Hanfmann, Roman Art: A Modern Survey of the Art of Imperial Rome (New York Graphic Society, 1964), pp. 103; 187; cat. 98 (ill.).

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Greek and Roman Portraits in North American Collections Open to the Public: A Survey of Important Monumental Likenesses in Marble and Bronze which Have Not Been Published Extensively,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 108 (1964), p. 103.

Evelyn B. Harrison, “The Constantinian Portrait,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 21 (1967), pp. 79–96, fig. 31.

James D. Breckenridge, Likeness: A Conceptual History of Ancient Portraiture (Northwestern University Press, 1968), pp. 247–48, fig. 131.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor (Harvard University Press, 1968), pp. 58; 356; 364–65, fig. 179.

Wilhelm Von Sydow, Zur Kunstgeschichte des spätantiken Porträts im 4. Jahrhundert n. Chr. (Habelt, 1969), p. 152.

Helga Von Heintze, “Ein spatantikes Madchenportrat in Bonn: zur stilistischen Entwicklung des Frauenbildnisses,” Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 14 (1971), pp. 78–83.

Raissa Calza, Iconografia Romana Imperiale da Carausio a Giuliano (L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1972), pp. 268–69, cat. 181, pl. 94, figs. 331–32.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Roman and Barbarians, exh. cat. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1976), pp. 110–11, cat. 118 (ill.).

Sandra Knudsen Morgan, “Letter From Boston: Romans and Barbarians,” Apollo 184 (June 1977), p. 499, fig. 8.

Kurt Weitzmann, Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century, exh. cat. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979), pp. 289–90, cat. 268 (ill.).

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, Greek and Roman Sculpture in America: Masterpieces in Public Collections in the United States and Canada (University of California Press/J. Paul Getty Museum, 1981), pp. 372–73 (ill.), fig. 323.

Klaus Fittschen and Paul Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts in den Capitolinischen Museen und den anderen kommunalen Sammlungen der Stadt Rom, vol. 3, Kaiserinnen- und Prinzessinnenbildnisse, Frauenporträts (Zabern, 1983), pp. 65–66, cat. 86, item o.

Karen Alexander and Mary Greuel, Private Taste in Ancient Rome. Selections from Chicago Collections, exh. brochure (Art Institute of Chicago, 1990), cat. 7.

Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson, I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, exh. cat. (Yale University Press, 1990), p. 173, cat. 128 (ill.).

Bente Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism in the Plastic Arts: Studies in the So-Called Theodosian Renaissance (Odense University Press, 1993), p. 117.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Roman Art,” in “Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 1 (1994), pp. 73–74, cat. 51 (ill.).

Demetra Papanikola-Bakirtzi, Everyday Life in Byzantium, exh. cat. (Hellenic Ministry of Culture, 2002), pp. 379–80, cat. 464.

Ioli Kalavrezou, Byzantine Women and Their World, exh. cat. (Harvard University Art Museums/Yale University Press, 2003), p. 83, n. 1.

Karen B. Alexander, “From Plaster to Stone: Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Karen Manchester (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 32.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

Visible Light

Normal-light and raking-light overalls: Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens

Normal-light and raking-light macrophotography: Nikon D5000 with an AF Micro NIKKOR 60 mm 1:2.8 D lens

Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens and a Kodak Wratten 2E filter

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

High-Resolution Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Canon EOS1D with a PECA 918 lens and a B+W 420 (2E) filter pack. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Visible-light microscopy: Zeiss OPMI-6 stereomicroscope fitted with a Nikon D5000 camera body

Petrographic and thin-section analysis: Leitz DMRXP polarizing microscope equipped with a Leica Wild MPS-52 camera head

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry

Finnigan MAT 5000 mass spectrometer

X-Ray Diffraction

PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with vertical goniometer (CuKα/Ni at 40 kV, 20 mA)