Images of a Roman empress can be remarkably difficult to distinguish from those of other women (either ladies of the imperial court or private individuals). This phenomenon can be attributed, first, to a general interest in depicting idealized physical beauty, and, second, to an emphasis on the representation of elaborate, fashionable hairstyles, frequently of the type worn by the reigning empress. Consequently, when examining an unidentified female portrait that resembles a specific empress, scholars are confronted with a puzzle. Is it a new likeness of the empress, perhaps marked by variations not seen elsewhere? Is it a portrait of another woman of the court, maybe a sister, daughter, or other relative? Or finally, is it an image of a private individual, created in the predominating style of the time?

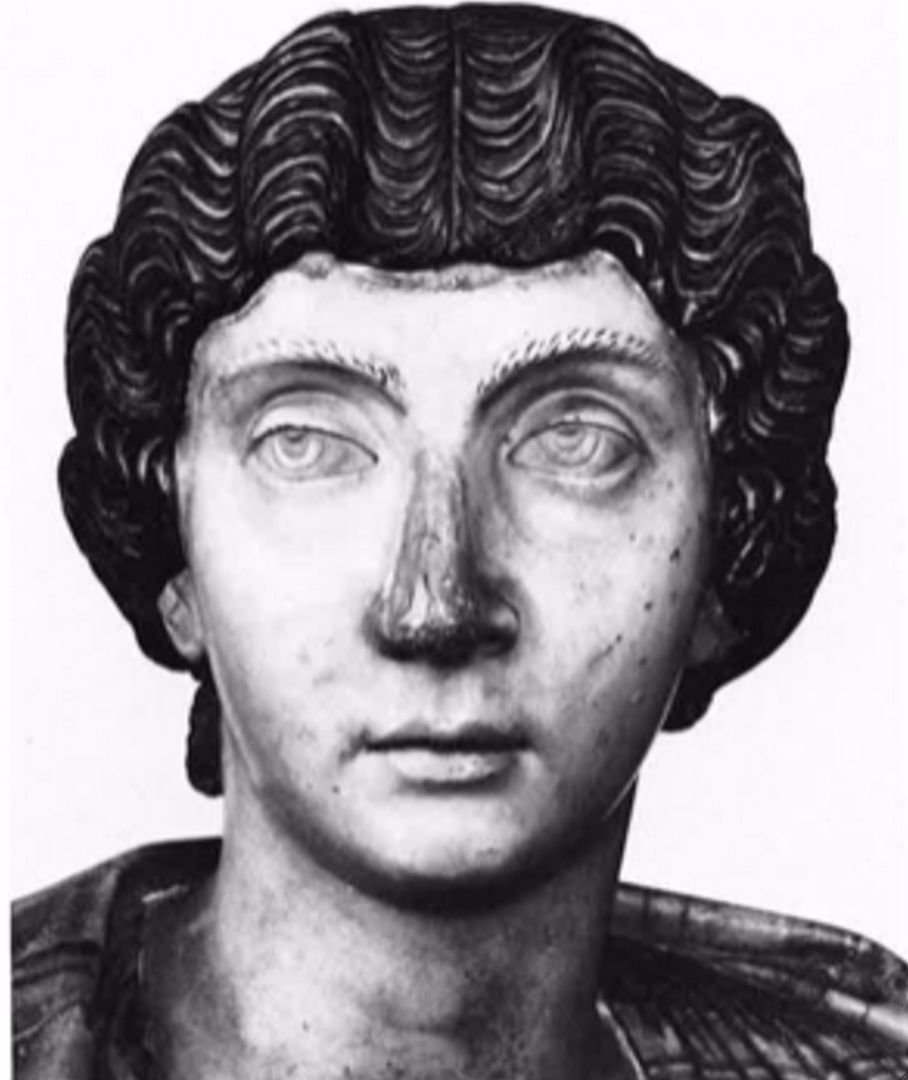

Just such a mystery is posed by this slightly over life-size portrait of a woman carved of Carrara marble. The woman’s smooth face, with its fleshy cheeks and rounded chin, shows no obvious signs of age. Her calm gaze and lightly pursed mouth, however, convey a serenity and dignity worthy of a proper Roman matron. The large, heavy-lidded eyes are smooth and lack any traces of incising of the irises or drilling of the pupils, suggesting the work’s creation before or near the time of the introduction of these stylistic features around A.D. 130. The depth of the carving of the eyes is tempered by the lightly incised eyebrows, which extend nearly to the bridge of the now-missing nose. The lips, although small, are thoughtfully modeled and impart a certain degree of individuality, as the upper lip projects just slightly over the bottom lip.

Atop the woman’s head is a tall, lunate diadem, below which are three horizontal bands marked by short, diagonal lines incised at regular intervals. It is unclear precisely what these bands depict, but they are probably meant to be either twisted locks of hair or strips of fabric or ribbon. If the former, they resemble in their stacked arrangement the braids that formed part of the so-called turban coiffure, a hairstyle worn in the Trajanic period (A.D. 98–117) and particularly in the Hadrianic period (A.D. 117–38) in which the hair was gathered into long plaits that were wrapped around the upper part of the head, often leaving the crown visible (see, e.g., cat. 7, Portrait Head of a Young Woman). If the latter, they might have been used as a means of attaching either the diadem or a separately created hairpiece or wig to the sitter’s head. They might also evoke the fabric bands known as infulae that were worn by various individuals as a mark of sanctitas (holiness, inviolability, and sacredness), including Roman priests and priestesses, suppliants seeking pardon or protection, and sacrificial victims.

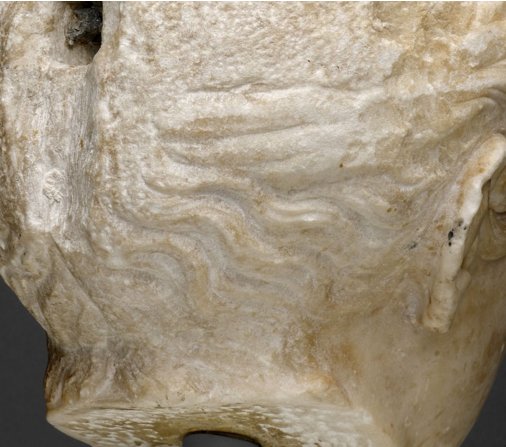

The remainder of the subject’s carefully coiffed hair is parted in the center and arranged on each side into seven scallop-like waves, which are formed by two alternating locks woven into the lower and middle horizontal bands (fig. 5.1). Within each wave, individual hairs are defined with narrow, incised lines, which are more subtly rendered than the diagonal lines carved into the horizontal bands.

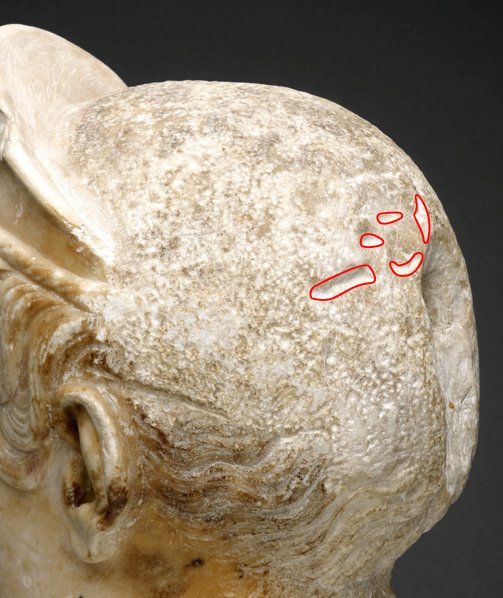

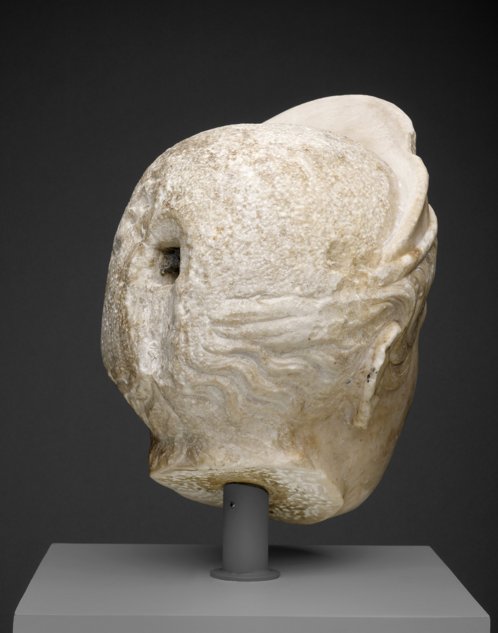

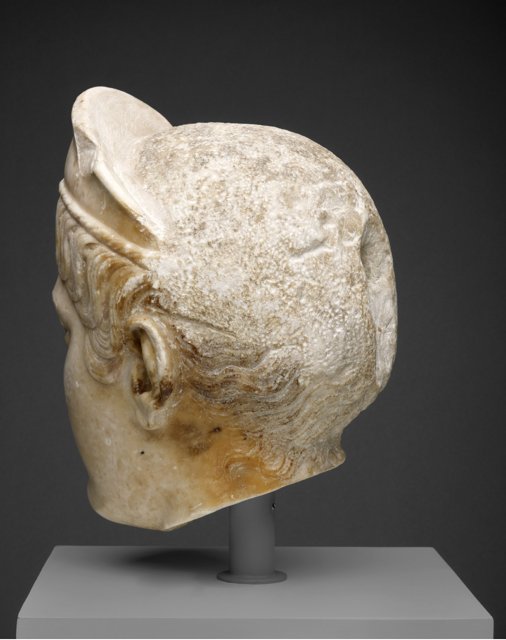

On the back of the head, very little of the original hairstyle remains. The surface of the upper part of the head is heavily keyed, and a square cavity at the center appears to have provided support for a separately carved hairstyle or attribute (fig. 5.2). On the lower part of the head there are traces of the three horizontal bands extending behind the proper right ear, along with loose waves running from behind both ears toward the center of the back of the head (fig. 5.3). Short, wispy curls at the nape of the neck reach as far as the break edge (fig. 5.4). Taken together, this evidence indicates that the original coiffure in the back was removed in antiquity to make way for a new hairstyle or attribute. The shortness of the neck, which terminates directly under the chin, and the largely flat join face suggest that this head might have been removed from its original statuary body or bust in antiquity and attached to a new one at a later date.

Roman Female Portraiture

To the Romans, physical beauty (particularly in women) was thought to convey an individual’s virtues and positive qualities. In a female portrait head, beauty (both natural and artificial) was manifest not only in the facial features but also in the hairstyle. The idealized, often youthful features exhibited in many images of both imperial and private women, such as rounded faces, small mouths, and wide eyes, were commonly associated with the representation of goddesses. Distinct likenesses were sometimes suggested through the depiction of strong physiognomies; less frequently clear signs of age and maturity were incorporated.

On the other hand, considerable attention was paid to the accurate representation of women’s hairstyles, due in part to the association of carefully coiffed hair with cultus. A sophisticated, refined woman’s hairstyle, much like her dress and behavior in the public sphere, was an outward sign of her gender, wealth, and social position. A luxurious coiffure signaled that a woman had at least one servant or slave proficient in hairdressing, as well as the leisure time to have her hair done. Moreover, the physical control exerted over a woman’s natural hair to create an elaborate style was an indication of her civilized nature.

Many Roman women wore styles resembling the coiffure favored by the reigning empress, which was widely known through its representation in sculpted portraits and on coins. Consequently, the empress’s hairstyle is often thought to have set the fashion for the imperial circle and private women alike. However, styles that developed in the private sphere also appear to have attained some popularity. Particular styles do not seem to have been restricted to the members of certain social orders, as both freedwomen and aristocratic women are known to have worn some of the same coiffures. To be sure, some women continued to wear styles associated with earlier periods, whether as a sign of cultural identity, as a generational marker, or based on individual taste.

Even when conforming to the prevailing style of the period, women’s hairstyles (particularly those of private women) varied considerably in terms of the number and arrangement of waves, curls, and braids, as well as the use of artificial hair and jewelry, all of which could be employed to create a particular look. As Elizabeth Bartman has suggested, “women seem to have avoided looking just like their neighbors.” In fact, it has been argued that a woman’s hairstyle as represented in her portrait might have been the only feature that truly resembled her actual appearance. Nevertheless, women’s portraits seem to have been characterized by a certain degree of uniformity that blurred status distinctions and made the subjects appear (at least superficially) more similar than not.

A New Portrait of Sabina?

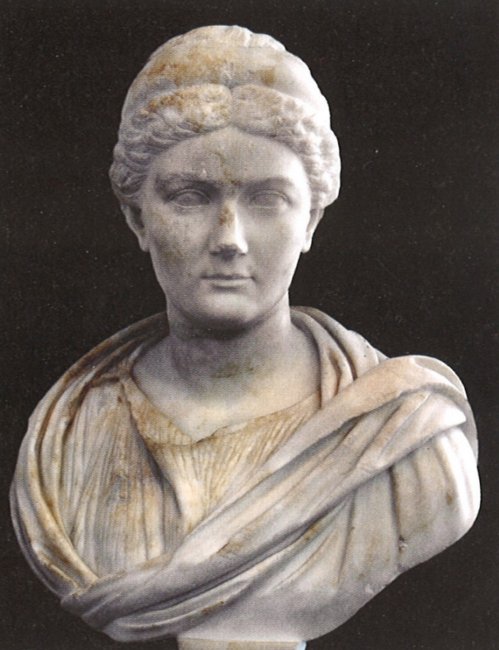

It has been suggested that Portrait Head of a Woman might represent Vibia Sabina (A.D. 83/86–136/137), the wife of Emperor Hadrian. Although the work does not coincide precisely with any of Sabina’s four known portrait types, its facial features bear a general resemblance to her physiognomy as portrayed on coins and in sculptures in the round, as can be seen in a bust of the empress in Rome reflecting her most widespread portrait type (fig. 5.5). The Chicago portrait, like many images of Sabina, includes a rounded, idealized face, a small mouth, and a hairstyle parted in the center. The eyes of the Chicago portrait lack incised irises and drilled pupils, also similar to sculptures of the empress produced during her lifetime. Additionally, the diadem was an attribute of this portrait type. Finally, the slightly over life-size dimensions could indicate the subject’s elevated social standing, perhaps as a woman of imperial rank.

This identification, however, seems unlikely for several reasons. First, the subject’s facial features exhibit minor differences from Sabina’s as represented in portraits and on coins. In particular, the eyes of the Chicago portrait appear to be slightly larger than those commonly found in images of the empress, but they also look more heavy-lidded. In addition, while both figures have small mouths, the upper lip of the Chicago portrait protrudes noticeably over the lower lip.

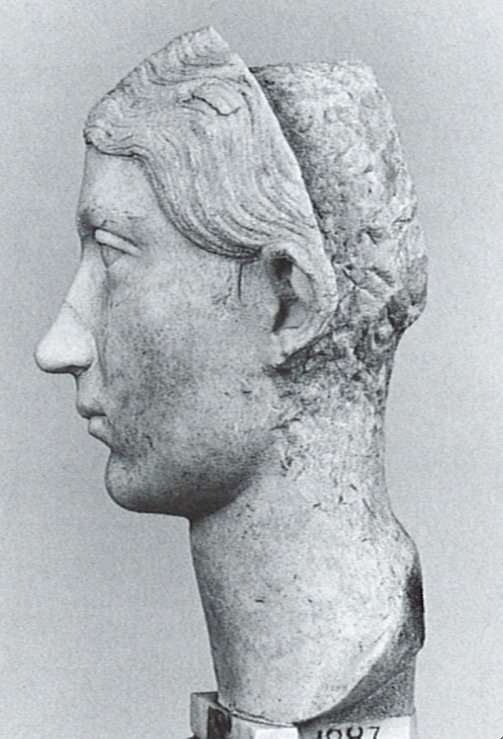

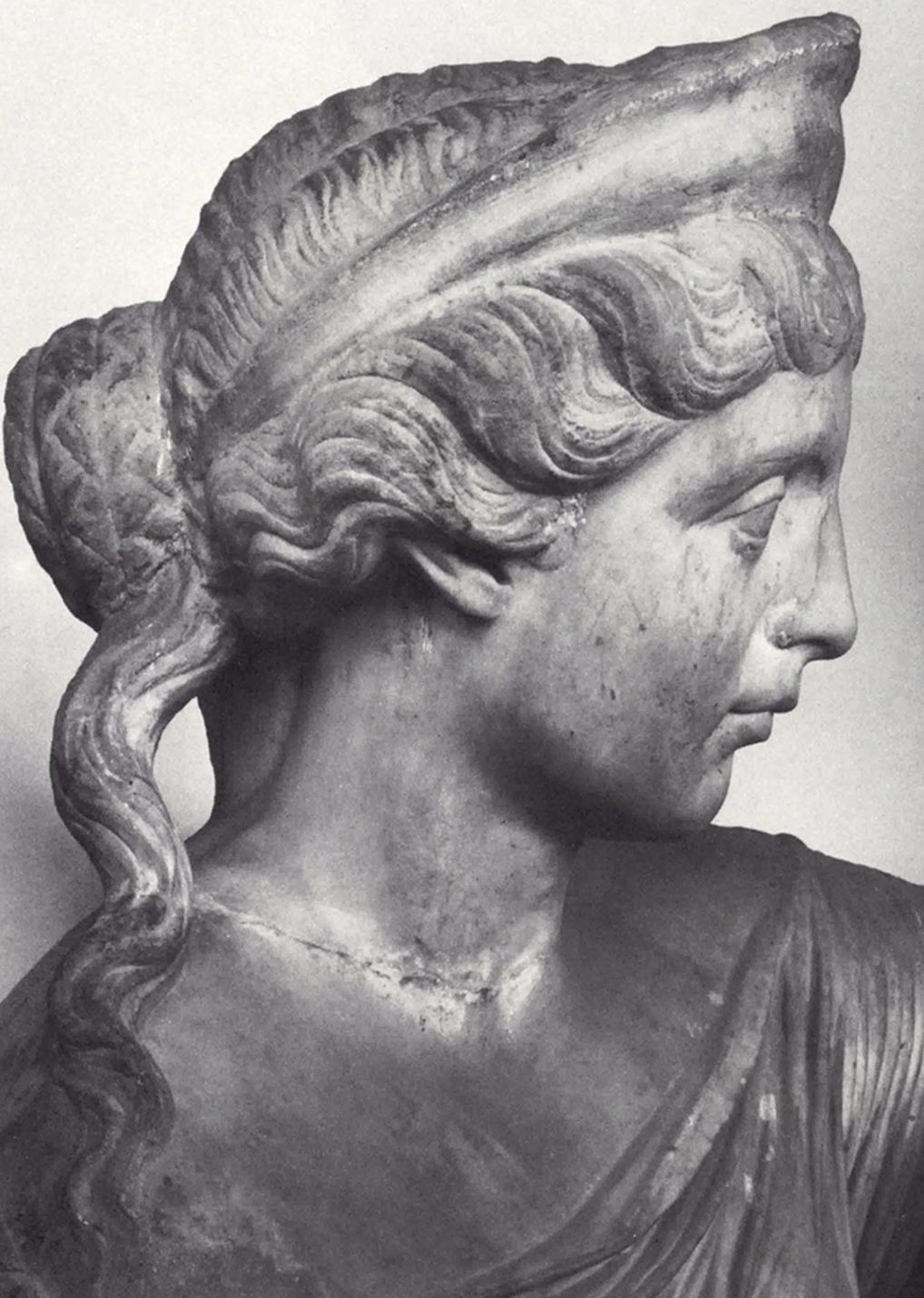

Second, the hairstyle of the Chicago work is rather unusual and is not represented in any confirmed portraits of the empress. Sabina’s earliest portrait type shows her with a row of what appear to be flattened, S-shaped locks across her forehead, above which projects a fanlike arrangement of hair (fig. 5.6). Although generally similar to the scalloped waves of the Chicago portrait, they are by no means identical.

Third, although in early Roman artworks the diadem was the privilege of goddesses, by the reign of Emperor Caligula (r. A.D. 37–41) it was included in images of deceased imperial women, and in the reign of Emperor Nero (r. A.D. 54–68) it began to appear in lifetime portraits. By the end of the first century A.D. it was incorporated in portraits of private women, frequently those employed in the funerary sphere. At this point it might have lost some of its connotations of authority and privilege, yet it still endowed the individual with an air of respectability and piety.

Finally, although over-life-size portraits were undoubtedly costly and lavish commissions, they were not limited to members of the imperial family, as they are attested in representations of private individuals, including women.

The Chicago portrait therefore probably does not depict Sabina wearing a hairstyle that is otherwise unattested in her portrait types. It more likely represents an unidentified woman of at least moderate if not considerable wealth and social standing, who perhaps even belonged to the court. While the interest in an idealized, youthful appearance is a common stylistic feature of female portraiture, the distinctiveness of the hairstyle as it is preserved and the evidence of a later phase of intervention raise questions about the portrait’s original and updated appearances.

Recarved and Pieced Hairstyles in Roman Portraits

Recent scholarship has revealed the frequency with which portraits in the imperial period were recarved and the varying degrees to which they were altered. While some portraits might have been reworked for aesthetic purposes—to update the original subject’s appearance or to make repairs to a damaged likeness—others were changed for political reasons, including damnatio memoriae. However, recarving was most often undertaken for economic reasons, particularly in order to reuse marbles when commissioning a new work was financially prohibitive.

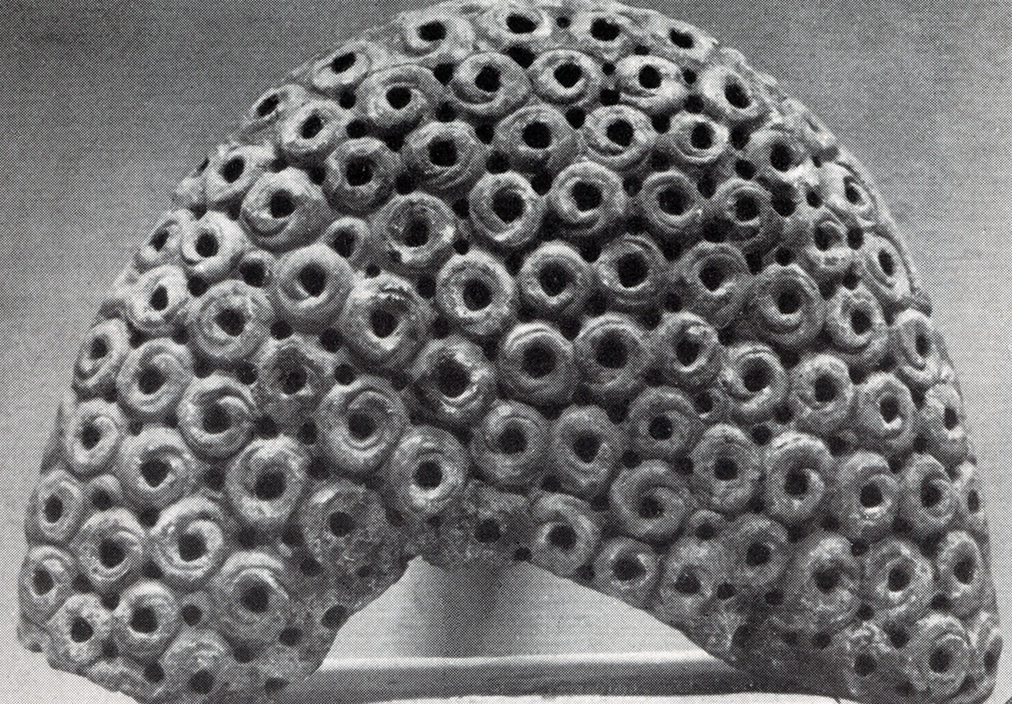

Reworked portraits of both imperial and private women from the first and second centuries A.D. are attested, although the practice was more common in late antiquity. Among recarved portraits in which the subject’s identity was not changed, minor alterations might have been made to the subject’s physiognomy, but in many examples the facial features were left untouched. While aspects of the original coiffure might be preserved, the hair was usually the focus of the revision, whether it was simply modified or removed altogether and replaced with a new attachment. For example, in a portrait in Boston with a tiered, Trajanic hairstyle, the subject appears to have initially worn a late Flavian toupet coiffure involving curls piled high over the forehead, as suggested by the remains of the drill holes employed to depict the curls (fig. 5.7). While the back of the head appears to have been modified to include a larger, now-missing nest of braids, the face was not altered.

Some hairstyles (whether in the original or the reworked state) seem to have been intentionally pieced rather than carved from the same block of stone as the rest of the head. The decision to piece a new sculpture might have been made based on economic concerns, as it might have allowed the sculptor to use a smaller block of marble for the head, particularly if the hairstyle incorporated a projecting feature. In both new and recarved portraits, piecing allowed separate hairpieces to be produced from marble scraps, such as those remaining from larger sculptures or irregular pieces that were not suitable for other uses.

Not only was the piecing of hairstyles a practical means of creating a complicated coiffure out of marble, it also mirrored the real-life practice of wearing wigs and hairpieces. Full and partial wigs, typically created with human hair, were worn by men and women, not only to cover baldness or thinning hair but also to augment a person’s natural appearance. Numerous Roman poets and satirists offered critical commentaries on such false locks, attesting to their popularity in elite circles.

In some recarved portraits, sections of the original head or hairstyle were completely removed to accommodate the addition of new, separately carved pieces. In one example in the Musei Vaticani in Rome, only the locks of hair over the forehead were retained from the original coiffure (fig. 5.8). The additions, which could be made of marble or stucco, do not often survive with the heads. Examples are attested, however, such as a separately carved Flavian toupet of curls that would have been attached above the forehead (fig. 5.9).

A number of female portraits produced in the late second and early third centuries A.D. clearly depict their subjects wearing full wigs. Some bewigged portrait heads were carved in one piece and intentionally include elements of the subject’s natural hair peeking out beneath the wig’s edge. Other wigs were carved separately from the head and in marble of a different color, as seen in a portrait in Rome (fig. 5.10). Such separately carved wigs simultaneously called attention to their artificiality and provided a more lifelike image of the individual. A few marble wigs, like the aforementioned hairpieces, survive without their heads.

While the motives behind recarving undoubtedly varied depending on the circumstances and the subject, some scholars have suggested that the primary purpose was to keep up with current fashions. Following this line of thought, it has been argued that separately carved marble hairpieces and wigs were created so that a portrait’s hairstyle could easily be altered to correspond with a woman’s changing appearance. Such modern assumptions, which presume that women were (and perhaps still are) preoccupied with maintaining an up-to-date image, are clearly problematic. Beyond any fashion-related concerns, it is reasonable to suppose that hairstyles were sometimes updated to communicate social or political messages. Indeed, in resembling the current empress, a woman’s portrait might have conveyed not only her support of the virtues and values for which the empress was honored but also more broadly her or her family’s endorsement of the emperor’s policies.

The majority of female portraits that incorporate a new hairstyle appear to have been reworked soon after their original creation. Some might have been recarved during the subject’s lifetime for any of the reasons noted above, while others might have been altered upon her death. Regardless of the reasons for recarving, it was clearly a practical response to the need for an appropriate likeness of a changing subject.

As noted above, the back of the head of the Chicago portrait is heavily keyed and includes a cavity that was used to support a separately carved hairpiece or attribute. Although the work might have been pieced initially, in this case it seems more likely that it was recarved at some point after its creation. As in many reworked female portraits of the first and second centuries A.D., the facial features of the Chicago portrait were largely preserved and the hairstyle was significantly altered, with some parts of the original coiffure remaining.

Evidence of the Original Hairstyle and Questions of Date

The features of the portrait that reflect its original state shed some light on when it was created. A date during Hadrian’s reign seems reasonable based on the subject’s general similarity to images of Sabina. Furthermore, the eyes provide compelling evidence regarding the portrait’s date, given that they lack the drilled pupils and incised irises that became common components of the Roman sculptural repertoire around A.D. 130 (fig. 5.11). It therefore seems likely that the portrait was made before or close to this date.

Elements of the original hairstyle that remain include the scalloped locks and horizontal bands in the front and the loose waves and wispy curls in the back. It can safely be assumed that these aspects were part of the initial carving because they were incompletely removed during the reworking. For example, the three horizontal bands, still visible behind the proper right ear, were almost entirely eliminated on the proper left side of the head (fig. 5.3 and fig. 5.4). Since the horizontal bands play an integral role in the arrangement of the scalloped waves over the forehead, the two elements must have been carved together. Similarly, the curls near the base of the neck are more fully preserved on the proper left side than on the proper right.

The scalloped waves and bands of the original coiffure provide additional support for a Hadrianic date. Although these features are presented in a somewhat unusual combination that is not matched precisely in any other examples of Roman female portraiture known to this author, general stylistic parallels can be identified in a limited number of late Trajanic and Hadrianic female portraits, which foreshadow certain stylistic developments in the female hairstyles of the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93).

For example, the shallowness of the relief, along with the superficial carving of the strands of hair, is similar to numerous Trajanic and early Hadrianic coiffures incorporating a row of flattened locks or curls arranged over the forehead (see fig. 5.6). The distinctive scalloped waves over the forehead, although infrequently represented during this period, are attested in several examples. For instance, an early Hadrianic portrait head of a veiled woman from the villa of the Volusii Saturnini at Lucus Feroniae (located approximately twenty-five miles northwest of Rome) shows the subject wearing a hairstyle composed of similarly shallow, scalloped locks placed across the forehead (fig. 5.12). This head, which has been interpreted as a portrait either of Sabina or of an unidentified woman, includes two narrow horizontal bands similar to those of the Chicago portrait, above which additional locks are shaped into a diadem-like formation. Another comparison is found in a Hadrianic grave relief from Ostia, which depicts the busts of a husband, wife, and son (fig. 5.13). The female subject, whose facial features call attention to her maturity, is shown wearing a hairstyle of wavy locks in overlapping scallops over the forehead. Above these locks runs a single, horizontal band, surmounted by a turban coiffure atop the head.

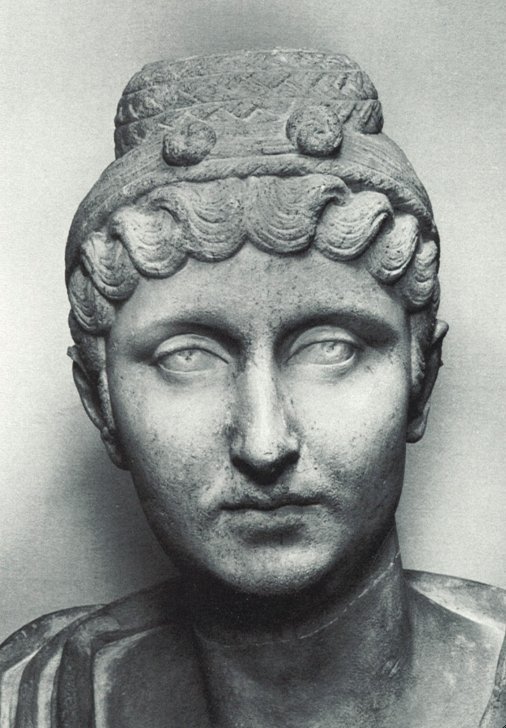

This style of scalloped locks over the forehead seems to have been more frequently employed in the Antonine period, albeit with a greater plasticity that distinguishes it from earlier examples. A portrait of Faustina the Elder, which is of a type that might have been created following her elevation to Augusta in A.D. 138, shows similarly interwoven, although clearly more voluminous, locks (fig. 5.14). Much like the Chicago portrait, here the scalloped locks sit below a horizontal band encircling the head and extend outward from a central part. This style also appears to have been embraced by private women in the Antonine period, as can be seen in a portrait in Los Angeles that features wide, shallow waves over the forehead, surmounted by a second tier of looser, undulating locks (fig. 5.15). A small section of a horizontal band is revealed at the center of the second tier, similar to the arrangement on the Chicago portrait.

On the back of the Chicago work, the hairstyle comprises loose waves and small, tendril-like curls at the nape of the neck. Although these elements are not indicative of a specific hairstyle or period, they are comparable to examples seen in numerous elaborate coiffures from the first and second centuries A.D. involving various toupets, crests, turbans, nests, and towers of hair.

While the full appearance of the back of this portrait’s original hairstyle is unknown, it seems reasonable to surmise that it might have incorporated a coil of braids, as is found in a number of late Trajanic and Hadrianic hairstyles. For example, in a Hadrianic portrait of Marciana (A.D. 48–112/14), the sister of Emperor Trajan, a slightly sunken nest of braids sits atop the upper part of the back of the head, while a diadem-like, multitiered crest of flattened curls forms the front part of the coiffure (fig. 5.16). Alternatively, it could have resembled the short, turban-like arrangement of braids seen in a portrait in New York depicting Matidia Minor (also known as Mindia Matidia), Sabina’s half sister (fig. 5.17). Here the braids encircle nearly the entire skull but do not extend to the forehead, which is surmounted by rows of tight waves that form scallop-like curls near the face. In the Chicago portrait, the inclusion of the diadem, much like the crest and the front locks in the portraits of Marciana and Matidia Minor, respectively, would have restricted the placement of an initial nest or turban of braids to the upper part of the back of the head.

On the basis of the Chicago portrait’s facial features and hairstyle, it seems reasonable to assign its initial phase of carving to the Hadrianic period. Although the scalloped locks over the forehead have some Antonine parallels, the lack of articulation of the eyes supports the likelihood that it was created in the Hadrianic era, with a terminus ante quem of A.D. 130. The continued popularity in the Antonine period of this basic style of front locks suggests that they were retained in the Chicago portrait in part because they complemented the appearance of the reworked coiffure in the back.

The Later Phase of Recarving and the Possible Form of the Attachment

The form of the later attachment is not known, although it is likely that it depicted either a hairstyle or an attribute, such as a veil. If the former, it could have reflected one of two possible coiffures represented in Antonine portraiture. A “tower” coiffure would have involved one or more braids coiled atop the head into a rounded stack, perhaps resembling the short bun seen in the portraiture of Faustina the Elder (see fig. 5.14). Alternatively, the attachment might have taken the form of a more voluminous, cap-like arrangement, such as that represented in another sculpture in the Art Institute’s collection, where it is combined with a delicate, bejeweled diadem (see cat. 8, Portrait Bust of a Woman). The new hairstyle may even have been a more dramatically vertical tower, as seen in a portrait bust of a woman from Cyrene, Libya, now in the British Museum (fig. 5.18). However, the lunate diadem was not regularly combined with the tower coiffure in Roman female portraiture, making it somewhat unlikely that it was employed here.

It is perhaps more likely that the attachment took the form of a heavy bun at the back of the head, with loose waves covering the crown. When combined with the diadem and scalloped waves in front, and possibly one or two long locks hanging from the back of the neck and falling onto the shoulders, it might have resembled the coiffure found in several portraits depicting women in the guise of Venus, the Roman goddess of erotic love and sexuality. In such theomorphic portraits, an individualized head was combined with the body of a deity or mythological figure, including his or her dress, attributes, and gestures. Venus was especially popular among imperial and private matrons for her associations with sexuality and maternity. Images incorporating both nude and draped statuary types of Venus and her Greek counterpart, Aphrodite, highlighted the idealized female form as a sign of fertility and beauty. Among private women, such Venus portraits are more frequently connected with the funerary realm, where they served a commemorative function, although they might also have been displayed in elite domestic contexts.

One such portrait is found in a sculptural group of early Antonine date in the Musei Capitolini in Rome that depicts a man and a woman with the bodies of Mars and Venus. The female subject wears her hair in scalloped waves over the forehead (albeit more voluminous ones than those in the Chicago portrait), above which is placed a diadem (fig. 5.19). In the Capitoline statue, the wavy locks on the back of the head appear to follow its contours closely, while the bun sits just above the nape of the neck. The reworked Chicago portrait may have looked similar to this.

Among the examples of portraits that include the hairstyle with a bun and a diadem, the statuary body or bust is typically either fully or partially nude, or clothed but with a revealing neckline. If the Chicago portrait was joined with such a sculpture in a phase of reworking, it is possible that the artist intentionally employed a straight butt join below the chin in order to make the join at the neck less obvious.

On the basis of stylistic considerations, the Venus portraits that incorporate a version of this hairstyle and a diadem have generally been dated to the Antonine period. If the attachment to the Chicago portrait did in fact resemble this style, it seems likely that it would have been added during that period. If this was the case, the sculpture might have been updated following the subject’s death. After all, many examples of theomorphic portraits seem to have been created for the funerary sphere. The addition of a Venus-like hairstyle might have suggested the subject’s assimilation to the goddess, which would have been further reinforced by the existing attribute of the diadem, here perhaps taking on divine connotations. While the hair might have been updated to reflect an Antonine style, the eyes were not altered to include the articulation of the pupils and irises that was common during this period.

Another possibility is that the portrait was modified to receive a separately carved veil. When worn by women, the veil bespoke modesty, chastity, and status: it was worn by brides on their wedding day and by matrons when out in public, although in the latter case this does not seem to have been a requirement. A married woman would typically have formed a veil by drawing her palla over her head. One of the characteristic elements of the Roman matron’s costume, the palla was typically not pinned in any way but rather required one hand to keep it in position, thus making it unsuitable for manual labor and signifying the wearer’s elevated social status. The veil also carried connotations of traditionalism and piety, as it had long been worn by both sexes when performing religious rites or sacrifices; in such contexts the wearer was referred to as capite velato. Indeed, portraits of women wearing veils are at times identified as images of priestesses, particularly when they include other attributes with sacred associations, such as the diadem or the infula, or when they depict the subject engaged in a religious action, as in an example in Boston portraying a veiled, elderly woman burning incense (fig. 5.20).

In portraits of veiled subjects, the head and veil were often carved in one piece, as in a veiled, diademed image of Sabina in Rome, another example of her most widespread portrait type (fig. 5.21). At times the head might have been created separately from the veil, however, as seen in a sculpture of a woman (perhaps Faustina the Younger) found in Athens. Part of the back of the head was omitted, likely because the head was intended to be set into the hollow hood of the veil or veiled body. Separately carved veils rarely survive, probably due to their undoubtedly fragile forms, but that does not rule out the possibility that the Chicago portrait was adorned with this type of attachment. Since the shape of the head is largely preserved in the back, a separate veil would likely have been made of a very thin piece of marble that would have followed the contours of the head. If this was the case, the artist may have been relying on the features of the hairstyle that are preserved from the original carving, namely the diadem and the horizontal bands resembling the infula that are woven into the scalloped locks over the forehead, to evoke a priestly appearance when combined with a veil.

Conclusion

The identity of the subject of Portrait Head of a Woman remains a mystery, yet the elegant carving of her likeness, combined with the slightly over life-size scale and the use of fine Carrara marble, suggests that she was a person of considerable wealth and social standing. While the portrait’s sensitively rendered, idealized features bestowed the appearance of natural physical beauty, the sophisticated coiffure celebrated the subject’s cultus and designated her as a civilized and refined Roman matron. The form of the updated hairstyle or attribute is not known; it might have been a tower coiffure, although it seems more likely that it was a cap-like covering of waves over the head with a bun at the nape of the neck, resembling the styles seen in portraits of women in the guise of Venus. In the latter case, the new hairstyle might have been attached after the subject’s death in order to suggest her divine assimilation. Alternatively, the attachment could have taken the form of a veil, evoking the subject’s piety, modesty, and matronly virtues and perhaps also conveying a priestly aspect. Regardless of the motives behind the recarving, it is apparent that such alterations were made with the intent of maintaining an appropriately idealized and cultivated likeness of the subject following the conventions of contemporary Roman portraiture.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This over-life-size portrait head of a stately woman, carved from a deep ivory marble that has been identified as Carrara, tells an interesting story (fig. 5.22). Toolmarks on the back of the head reveal that the woman’s appearance was once different, and that the original marble was later reworked to accommodate the addition of a new hairstyle or attribute that was subsequently lost. The addition was fitted onto the existing head through mechanical action, by way of both the keying and a metal cramp. The overall shape of the reworked area, which largely preserves the form of the back of the head, could also have provided some structural support for the attachment. No indication of polychromy or gilding has been detected. Patinas caused by the burial environment are present on the surface of the stone, but little else remains in the way of contextual evidence. The stone itself is in an excellent state of preservation. The legibility of the portrait is somewhat marred by conspicuous losses to the nose and diadem, but the visage is impressive nonetheless. The object once bore restorations to the nose and neck. More recent conservation treatments performed since the object entered the museum’s collection have been carried out to improve areas of previous restoration and to stabilize damaged areas.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is a deep ivory tone overall, with prominent, ocher-colored and translucent inclusions dispersed throughout the matrix.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); limonite, FeO(OH)·H2O (traces)

Petrographic Description

A sample 0.9 cm high by 1.9 cm wide was removed from the keyed surface in the back, approximately 4 cm above and 0.5 cm to the proper left of the large square cavity at the center of the head. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.95 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic with some triple points

Calcite boundaries: straight-embayed

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed little to no decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 5.23

Provenance

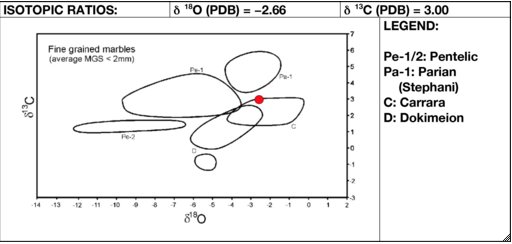

Marble type: Carrara (marmor lunense)

Quarry site: Carrara region, Apuan Alps, Italy

The determination of the marble as Carrara was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 5.24

Fabrication

Method

The object was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

The head once formed part of a portrait statue or bust. With the exception of a section of the proper right side that undulates upward, the break through the neck is almost completely flat (fig. 5.25). The topography of this join is consistent with what is referred to as a straight butt join. Straight butt joins through the neck most often indicate replacement heads, which are secured to the adjoining stone using dowels or pins, often supplemented by a mortar or adhesive.

The surfaces of straight butt joins are often keyed to provide extra tooth for the mortar or adhesive. Such is the case with this portrait head, which shows keying that may have been made with a point chisel applied in sharp, successive blows. However, the character and aspect of this keyed surface do not appear ancient. The inner surfaces of the struck marks are bright white and show no evidence of burial, soiling, or even handling. Furthermore, the marks overlie a liberally applied patch of a dark, ocher-colored material that, given its appearance and location, is presumably an adhesive. An image of the object bearing a restoration of the neck and collarbone appears in a 1928 collection catalogue (fig. 5.26). Despite the limited quality of the photograph, it is evident that the restoration followed the present neckline and contained some amount of intermediary fill material, for either bonding or leveling purposes. It seems plausible that the current condition of the underside of the neck is the result of the removal of this intervention at some point after 1928. Alternatively, the extant keying may be an artifice, added by a later restorer to confer a greater sense of authenticity.

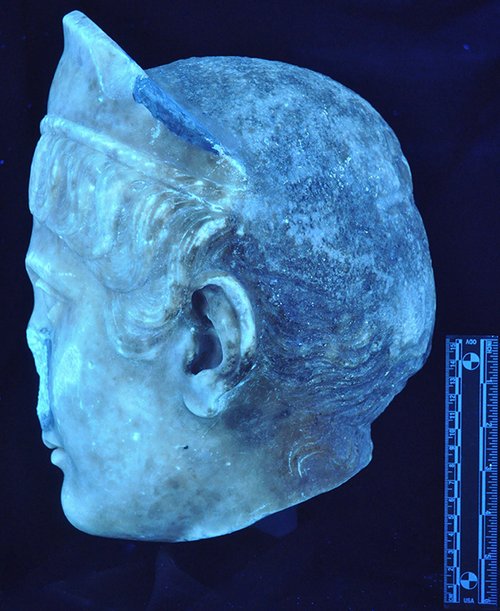

Examination under ultraviolet radiation reveals the stone along the break edge of the neck to be somewhat violet compared to the rest of the face, which appears more yellow-green. This suggests that this surface was indeed cut or worked subsequent to the original carving of the portrait and lends some weight to the theory that the head was removed from its original bust or statue in antiquity. The cut was made directly under the chin, implying that the sculptor shortened the neck from a presumably longer section of stone in order to fit it onto a sculpture that included the full length of the neck and possibly some of the collarbone and chest. It seems most probable that the sculptor who carried out this reworking left the surface quite plain and used only a dowel and a very strong adhesive. Without removing the existing pin affixing the object to its pedestal, it is impossible to know more about the original pin that might have been used, such as its diameter, the depth of its penetration, or the material from which it was made.

The uncertain aspects of the method of attachment notwithstanding, what is abundantly clear is that the portrait once bore a different hairstyle or other feature and was later reworked to accommodate a new one. The back of the head has been heavily keyed, and, although the general contour of the head has been retained, much of the stone at the nape of the neck has been cleared away, resulting in a slightly squared-off protrusion. Examination of the object under ultraviolet radiation reveals a significantly more violet coloration in this recut area compared to the face and diadem, which appear more yellow-green (fig. 5.27). Some of the original curls and waves of hair remain visible on the back of the head. Those on the proper left side, in particular those in direct contact with the neck, are still quite sharply defined, but those on the proper right side have been almost entirely obliterated (fig. 5.28 and fig. 5.29). Such treatment may indicate that the curls from the original sculpture were not meant to be seen in the later revision.

The attachment was further reinforced by means of an iron cramp fitted into a square cavity in the back of the head and affixed with lead. A vertical channel just below the cavity accommodated the cramp. Iron staining is visible around the square cavity and along the channel, and a considerable quantity of lead remains embedded in the cavity (fig. 5.30). The location and angle of the cramp suggest that its function was either to support a projecting or pendulous element directly on the back of the head or to redistribute the weight of an addition that extended vertically above or below the attachment point. To the upper left of the cavity, five extremely hard percussive blows were applied to the stone with a point chisel (fig. 5.31). Whether these deep depressions served any mechanical function, for either keying or providing tooth for a mortar, is unclear. A shallow channel was carved along the back of the diadem and behind the ears that would also have assisted in securing the new addition in place.

A flat band of wear runs along the proper left side of the back of the head, indicating a particularly close point of contact between the keyed surface and the overlying addition (fig. 5.32).

The contour of the reworked area, so close in form to a real head, is a curiosity. It is possible that this spheroid shape bore a direct relationship to the profile of the new addition, for example, if it consisted of a veil or a hairstyle that lay close to the head. At the same time, the sizable cramp seems to contraindicate a thin or subtle overlay of marble and instead suggests that the addition required significant support, as would be true for a large, upthrust coiffure or a strongly projecting gathering of hair. If that was the case, however, why did the sculptor not cut away more of the original head in order to accommodate a more substantial base for the attachment? Perhaps economic considerations came into play, either for the sculptor or the patron, and it was necessary to use the smallest quantity of stone possible to realize the modification.

Because this head is a private portrait, it might well have been removed from an earlier statuary body or bust and joined to a new one, perhaps to follow changing fashions or to mark an important life event. It may have been during this same phase of reuse that the back of the head was modified to receive the new attribute.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The original stone surface at the back of the head was cleared away using both a point and a claw chisel. The claw chisel was used first, followed by additional keying with the point chisel.

Because the back of the diadem was not meant to be seen, traces of the scraper used to finalize its shape, most probably by the original sculptor, remain visible. They are somewhat difficult to discern, however, beneath overlying heavy scratching that is presumably modern.

A rasp was used to create the channel that runs behind the diadem and the ears (fig. 5.33).

The deep groove between the lips was rendered using a drill and a channeling tool. The proper right corner of the mouth terminates in a circular depression, indicating the starting or finishing point of the drill. In the proper left corner, straight lines extending outward from the groove show the path of the channeling tool (fig. 5.34).

A flat chisel set at a sharp angle was employed to articulate the contours of the eyes and to create the locks of hair and the twisted bands below the diadem.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding. Some powdery red material resembling pigment is visible on the back of the neck, but as this overlies a recut area that was not meant to be seen, it must be considered postdiscovery contamination.

Condition Summary

The nose is missing entirely, although a small fragment of the bridge remains adhered on the proper right side. Abrasions in association with a previous restoration are visible around the perimeter of the loss. Remnants of overpaint are apparent upon close inspection and are unmistakable when viewed under ultraviolet radiation (fig. 5.35).

Significant losses in the form of large lacunae are present along the top of the diadem at the outer ends. There are smaller losses on the front of the diadem and the back of the proper left earlobe. Minor chips and losses are in evidence on the eyelids, and flat spalls are visible at the outer ends of the eyebrows, which are themselves much eroded. Much of the carving in the hair and in the bands below the diadem is heavily eroded, resulting in an inconsistent level of relief and lending the treatment of the hair a somewhat flattened appearance. The surface is heavily pockmarked, with associated bruising, in particular on the proper right cheek. Minor scratches and gouges are visible on the front of the diadem and on the forehead. A large spall is present on the proper left cheek. Minor chips and losses are apparent around the outside edges of the earlobes.

Very little evidence of burial can be seen on the surface of the object, and that which does remain is in the form of localized staining from the burial environment. A pronounced orange patina, possibly related to environmental phosphate, runs from the base of the neck on the proper left side up into the diadem. Within this band of orange coloration, dark brown areas are visible on the back of the proper left ear and in the adjacent section of hair (fig. 5.36). Black stains are present on the back of the proper right ear and at the top of the proper left jawline.

A waxy sheen strongly reminiscent of an acid-cleaned surface can be seen, notably inside the ears and around the mouth. However, the appearance of the rest of the face when examined under ultraviolet radiation seems to contraindicate the use of such a treatment. The sheen may instead be attributable to the undocumented application of a coating.

Conservation History

The first recorded treatment took place in 1989, when a portion of the diadem on the proper left side was broken. This impact affected an area of previous damage, where an existing plaster fill disintegrated and several new losses occurred. The broken fragments were reattached in their correct positions using an acrylic resin. New losses were filled with an adhesive bulked with aggregates. The fill was retouched using acrylic paints and matte acrylic varnish.

The object was treated again in 1993 with the goal of making aesthetic improvements to the area of loss around the nose. The original nose, which had been broken off, was at one time replaced with a stone restoration that was held in position with a rectilinear tenon. To accommodate this replacement nose, the upper lip was cut at a rather severe angle. The restored nose, as well as the previous repair to the diadem, was in place by 1928 (see fig. 5.26). This nose was removed prior to the object’s entry into the museum’s collection. In 1993, the new fill at the nose was made with an acrylic resin bulked with aggregates and pigments. The treatment served to disguise the disfiguring cut across the upper lip and to make the nose appear more naturally broken.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini