This over-life-size statue of a nearly nude male figure depicts the Greek hero Meleager. Renowned for slaying the ferocious boar that was sent by Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt, to terrorize the lands of Calydon, Meleager was a popular subject in art from the archaic Greek period well into the Byzantine world. This work is one of a number of Roman sculptures in the round that is believed to be based on an earlier Greek statue of the hero. More specifically, it has been suggested that the original was created by the Greek sculptor Skopas around 340–330 B.C. and that it may have been fashioned from hollow-cast bronze.

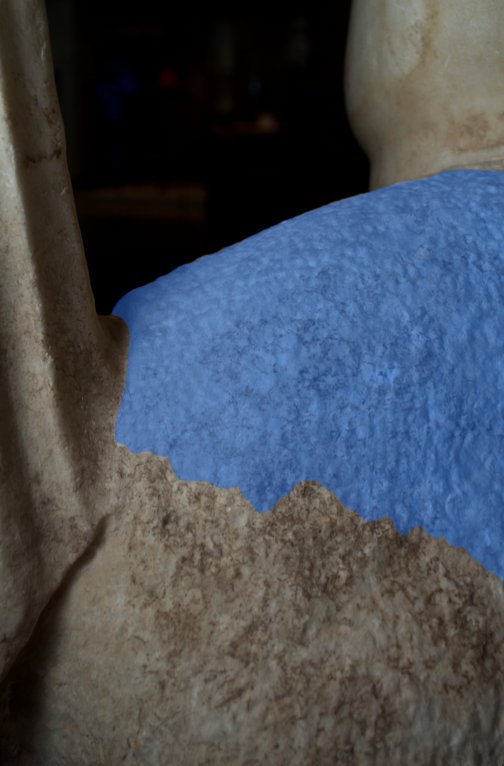

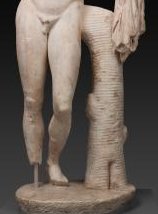

Made of Pentelic marble from Greece, the statue is fragmentary but preserves most of the body; it is missing the head, much of the proper left arm, the entire proper right arm, part of the genitalia, the proper right foot, and the front of the proper left foot. The work was carved almost entirely from a single block of stone, although the proper left arm was made separately and attached with metal pins, the remains of which can be seen in the upper arm (fig. 4.1). The back half of the base is original, but the front half is a plaster restoration that has been textured and toned to match the surrounding marble (fig. 4.2). The support, which is partially restored in the front along the break line, is identified as a tree trunk based on the small knot on the proper left side, the larger knot on the proper right side, and the deep vertical fissure at the bottom in the front. Additionally, concentric grooves on the front could suggest bark.

Shown in [glossary:heroic nudity] and in a [glossary:contrapposto] stance, the figure exhibits a softer, more subtle musculature than the Art Institute’s Fragment of a Portrait Statue of a Man (cat. 14), and the girths of his chest and thighs are suggestive of a mature male rather than a youth. The hero wears only a [glossary:chlamys] draped across his broad shoulders, pinned at his right shoulder with a now-missing [glossary:fibula], the outline of which still remains. The chlamys is wrapped over and around his left upper arm, hanging down in thick folds that connect to the tree-trunk support. In antiquity the chlamys was painted red, as indicated by the identification of lead red pigment within its folds. The red coloring is consistent with scenes depicting mythical heroes in Roman wall paintings, such as the one from the House of Gavius Rufus at Pompeii, in which the hero Theseus is shown having rescued the children intended as sacrifices to the Minotaur (fig. 4.3).

This statue, henceforth referred to as the Chicago Meleager, can be identified as a representation of the hero based on its form, style, and iconography, as evidenced most clearly by its pose and attributes. As an over-life-size, largely nude depiction of the renowned Greek hero, there are several possible contexts in which it might have been displayed during the Roman imperial period.

The Meleager Statuary Type

The mythical tale of Meleager was well known in antiquity. In one version of his legend, at Meleager’s birth the Fates decreed to his mother, Althaea, that he would die when a particular brand, which was currently aflame on the hearth, had been completely burned. She retrieved the brand from the fire and carefully hid it away. Years later, a fearsome boar was sent by Artemis to attack Calydon after Meleager’s father, King Oeneus, omitted the goddess in a sacrifice. On his father’s orders, Meleager assembled a group of hunters—including heroes from nearby cities; his maternal uncles; and his beloved, the huntress Atalanta—to take down the beast. Once the task was accomplished, Meleager awarded the hide to Atalanta, who was the first to wound the boar with an arrow. His uncles objected, and in the ensuing fight they were killed, either by accident or due to the hero’s rage. Althaea, in anger at her son for the demise of her brothers, threw the brand onto a fire, which led to his death and her suicide.

Aspects of Meleager’s tale, particularly the Calydonian boar hunt, were popularly represented in the archaic and classical periods in Greece on sculpted reliefs, in paintings (now lost), and on vases, mostly of Attic manufacture. Meleager does not appear to have been depicted in the form of large-scale sculptures until the fourth century B.C. The attribution of the Meleager statuary type to Skopas has been based largely on his role as the architect of the mid-fourth century B.C. temple of Athena Alea at Tegea in Greece, the east pediment of which featured the earliest sculpted representation of Meleager hunting the boar. Skopas’s involvement in the temple’s architectural design is thought by extension to suggest his influence in the creation of its sculptural decoration. Consequently, scholars have looked to the Tegean pedimental sculptures for signs of Skopas’s dynamic style, which is believed to have been characterized by a strong interest in three-dimensional movement, resulting in an emphasis on profile rather than frontal views, as well as a preoccupation with conveying emotion, particularly in the subject’s facial expression. However, no physical evidence has been found of the presumed original sculpture in the round depicting Meleager, nor are there references to such a statue or its sculptor in the ancient literature.

Nevertheless, a statuary type thought to represent Meleager has long been recognized by scholars, who, following the methodology of [glossary:Kopienkritik], have identified it as an image of the hero based on its iconography as well as its presumed Skopasian style. Roughly forty examples of this basic statuary type have been found, albeit with some stylistic and iconographic variations. The existence of this corpus lends support to the hypothesis that these statues are based on an earlier Greek prototype.

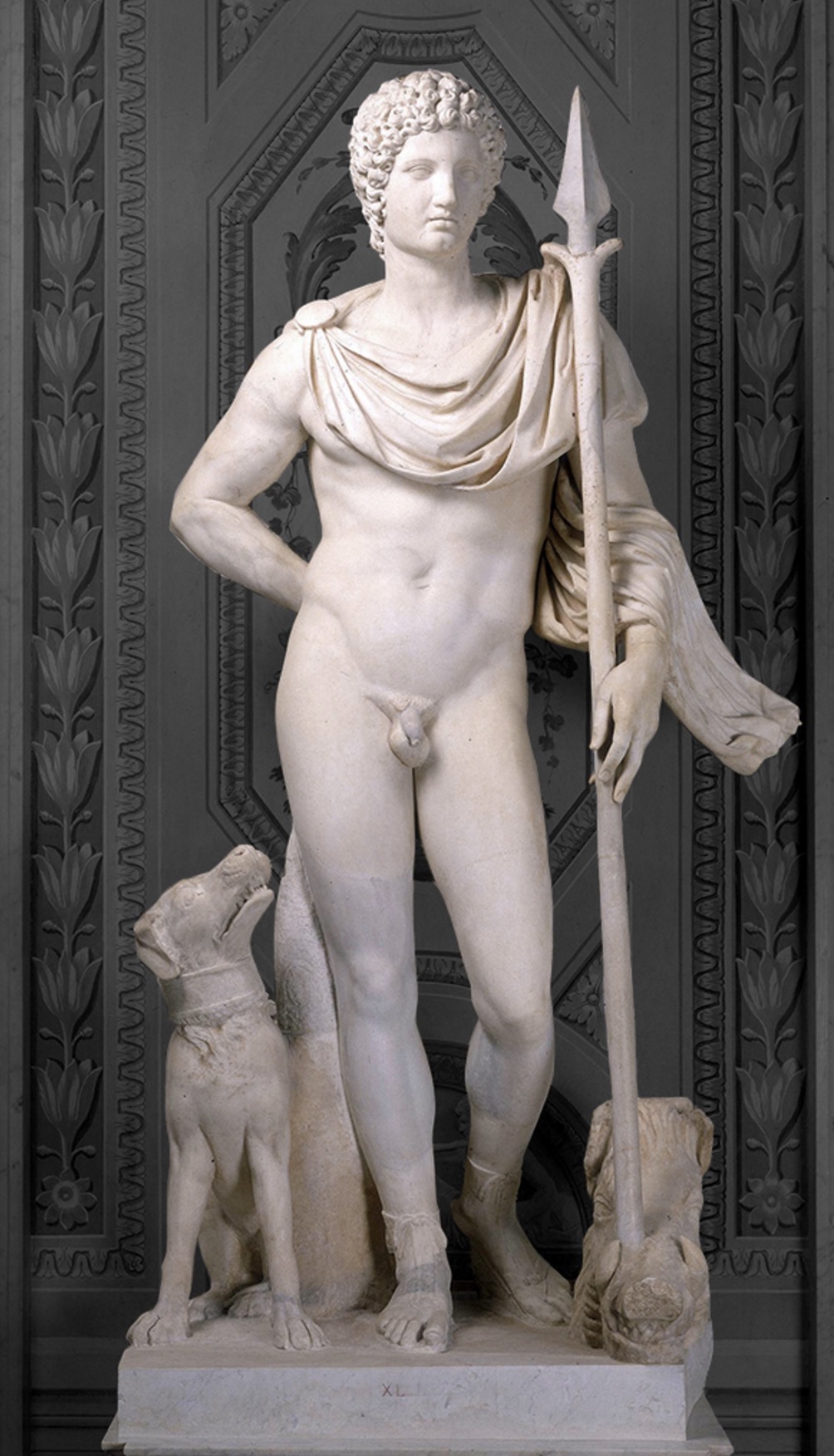

Arguably the finest example of the Meleager statuary type, which was the first sculpture in the round to be identified as an image of the hero, is a statue dated to the second century A.D. that has long been in the Museo Pio-Clementino of the Musei Vaticani in Rome (fig. 4.4). This statue, henceforth referred to as the Vatican Meleager, depicts the hero in a contrapposto stance, wearing a chlamys draped across his shoulders and around his left arm. On his right side a slender hunting dog gazes up at the hero, and on his left the boar’s head sits atop a support rendered in the form of a tall, narrow rock. While the dog is a common attribute in ancient representations of hunters, the boar is especially pertinent to the iconography of Meleager due to its place in his legend.

The identification of the Chicago statue as Meleager has been based largely on its pose and attributes. The figure’s contrapposto stance is notably similar to that which is associated with the basic Meleager statuary type. More specifically, he stands with his weight on his right leg, and his left leg is relaxed, with the knee bent and the heel raised. While this pose generally evokes that of the Doryphoros by Polykleitos (fig. 4.5), here the torso is twisted slightly toward the proper right, with the result that the figure’s subtle movement is most apparent in a three-quarter view. Because the head and neck are missing, it is not possible to determine the direction in which the head of this figure was oriented, but in other statues of this hero the head is typically turned to the proper left, as seen in the Vatican Meleager (see fig. 4.4).

The Chicago Meleager includes two attributes that appear in numerous representations of the hero. First, as in the majority of the more complete examples, this figure wears a chlamys around the shoulders and over the proper left arm. Since few statues of Meleager completely lack the chlamys, the frequency with which it appears suggests that it was a significant element in the hero’s iconography. Described aptly as “the garment of action,” the chlamys was worn in the Greek world by horsemen (particularly hunters), as well as travelers and soldiers. The motif of wrapping the chlamys around the left arm reflects its use in real life. This arrangement served the practical function of preventing the chlamys from obstructing the wearer’s movements while also providing protection in battle. In fact, Meleager often appears on Roman sarcophagi wearing the chlamys in this manner while in the midst of the hunt, as can be seen on a [glossary:sarcophagus] dated to A.D. 170/80 in the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Rome (fig. 4.6). On the Chicago Meleager, the dynamic arrangement of the chlamys contrasts with the more relaxed pose of the body, suggesting a brief moment of rest following his successful pursuit of the boar.

While the tree-trunk support in the Chicago statue undoubtedly serves a structural purpose, it might also have carried some iconographic significance (fig. 4.7). For instance, in a very literal way the tree trunk could evoke the outdoor environment in which the hunt took place. On a deeper level, it might have alluded to the brand linked to Meleager’s mortality and, more specifically, his impending death.

On the other hand, several attributes commonly seen in statues of Meleager are absent in the Chicago example, possibly due to its fragmentary state. First, the figure is lacking his presumed weapon, which was likely an upward-pointing spear, as attested in a statue in Copenhagen (fig. 4.8; henceforth referred to as the Copenhagen Meleager). The spear is critical to the identification of the subject as Meleager, for unlike the javelin, which might be used to hunt game such as stags, the spear was the weapon of choice for hunting boars.

Also missing is any indication of a hunting dog, which often appears on the figure’s right side, adjacent to the tree-trunk support, as seen in the example in the Villa Borghese in Rome (fig. 4.9), dated to A.D. 140/50. Much like the spear, the dog played an important role in hunting, as different breeds were employed in tracking and baying the quarry. Finally, the two least frequently represented attributes associated with the type, the boar’s head and the rock, are also absent in the Chicago Meleager. While it remains uncertain which of these attributes were part of the presumed original composition and which were later additions, the fact that they are not found in every example of the statuary type implies that they were not all necessary for the viewer to correctly identify the subject.

Of the missing attributes, the spear is the most likely to have been included in the Chicago Meleager, as the angle of the upper body suggests that the figure held something in his extended, now-missing left arm. A spear held in that hand could have provided extra structural support for the extended arm. In addition, the dog might have been incorporated into the base, perhaps forming a unit with the tree-trunk support, as can be seen in several other examples (e.g., the Copenhagen Meleager, see fig. 4.8). On the Chicago statue’s support, the front surface exhibits large plaster fills along the break line, raising the possibility that a dog might have appeared in this area of the base. If this was the case, the spear would have been placed so that it did not obstruct the view of the dog. Finally, the boar’s head and rock might also have been included, although this seems less likely given their infrequent occurrence. If they were part of the sculpture, they would have to have been placed on the figure’s right.

A New Meleager Type?

Despite the number of similarities that the Chicago Meleager shares with other statues depicting the hero, it also displays several minor variations that distinguish it from its peers. First, it is somewhat unusual for the tree-trunk support to appear on the proper left side. Moreover, the tree trunk is not partially hidden behind the figure’s leg as in other examples, such as the second-century A.D. statue from Salamis in the Cyprus Museum, Nicosia (fig. 4.10; henceforth referred to as the Cyprus Meleager). Rather, it stands almost independently on the proper left side, calling attention to its supportive function by means of the curved segment that connects it directly to the figure’s left hip.

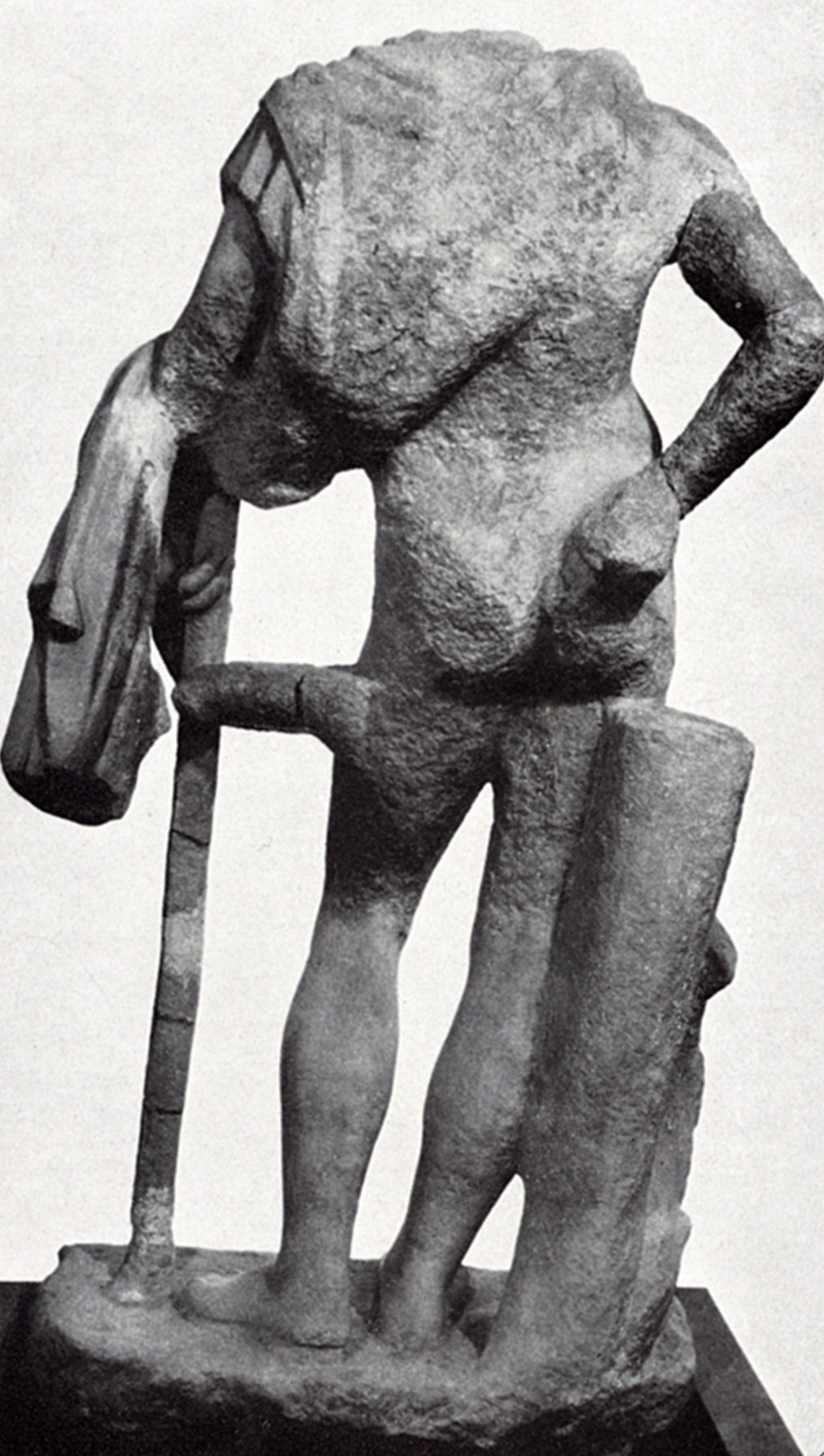

Second, both arms exhibit slightly atypical positions. The figure’s left arm extends outward and to his left, suggesting that the missing spear was probably held at a distance from the body. In other Meleager statues that retain traces of the spear, it is generally held closer to the body on the inside of the proper left arm, as in the example in Berlin (fig. 4.11; henceforth referred to as the Berlin Meleager), which is dated to the first century A.D. While it is unknown whether the proper left arm of the Chicago statue was fully extended or bent upward at the elbow, it is apparent that the horizontal orientation of the arm would have opened up the figure’s stance to a certain extent, giving him a more dynamic appearance that takes advantage of profile rather than frontal views.

With regard to the now-missing proper right arm, the remains of bridges or what might have been fingers on the figure’s right hip suggest that his right hand grasped this hip (fig. 4.12). In this way, it differs from a number of other examples, in which the right hand is placed against the right buttock with the palm out, as for instance in the Cyprus Meleager (fig. 4.13). In the Chicago statue, the positioning of the bent right arm with the hand on the hip seems intentional, perhaps to counterbalance the horizontal extension of the left arm.

A similar placement of both arms is attested in several representations of Meleager in other formats, specifically on later sarcophagi and silver plates. For example, on a late second-century A.D. sarcophagus from the necropolis under Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Meleager and Atalanta are shown standing together on a pedestal, resembling a statuary group (fig. 4.14). Meleager holds the spear erect in his left hand, which is pulled in close to his body, perhaps due to the compositional constraints of the relief format. To his left, Atalanta carries the boar’s hide in her right hand, indicating that the hero has awarded her the pelt. Meleager’s gaze is directed at his beloved, perhaps to emphasize the concept of the hunt as a metaphor for romantic pursuit.

This pose is repeated centuries later on Byzantine silver plates. On one such example in Munich, Meleager is shown alone, aside from the boar’s head at his feet. Here the long chlamys is not only draped over both shoulders, it is also wrapped around his right wrist, its end directing the viewer’s eye toward the trophy below. Moreover, on an early seventh-century silver plate in Saint Petersburg, the hero is represented in a bucolic setting, accompanied by Atalanta and a pair each of servants, horses, and hunting dogs (fig. 4.15). While the connection between hunting and love might be implied here, the scene might instead have been intended to remind the viewer of the literary tales of Meleager, which continued to be read by members of elite society as a part of [glossary:paideia].

Because the Chicago Meleager’s minor variations in pose are attested elsewhere, albeit not in large-scale statuary, it has been suggested that such modifications might speak to the existence in antiquity of a second Meleager type, which could have been produced alongside the basic type reflected in the examples cited previously. More specifically, Philip Oliver-Smith has proposed that the Chicago statue might embody an even earlier Meleager type created in the mid-fourth century B.C., perhaps as another variation on the same subject by Skopas.

While it is intriguing to consider the possibility that the Chicago Meleager might represent an entirely different sculptural type, it seems likely that its variations can be attributed to other factors. Sculptors regularly produced artworks that diverged to varying degrees from their presumed prototypes. The modern assumption that ancient collectors desired precise copies of earlier Greek statues does not appear to be substantiated by ancient literary sources, which stress the appropriate use of eclecticism to create a new artwork that emulated but also surpassed its models. As Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway has noted, “faithfulness to a model was not imperative or even desirable, and accuracy was a matter of degrees, since the prototype was not truly copied but rather rethought in contemporary forms and with a different context.”

To be sure, certain patrons might have preferred artworks that more closely adhered to earlier models, particularly in the case of famed statuary types recognized as [glossary:opera nobilia]. Indeed, ownership of such a sculpture might have not only enhanced the prestige of a collection but also identified the patron as an erudite, culturally knowledgeable connoisseur.

Nevertheless, statues frequently diverged from their presumed prototypes in their scale, iconography, materials, and quality. These variations could be attributed as much to the sculptor’s artistic initiative and creative freedom as to the patron’s desire for novelty and innovation. In some cases, distinct versions of the same basic statuary type might even have been displayed together as pendants, encouraging viewers to consider their formal and stylistic variations. Thus, while the Chicago Meleager appears to exhibit some clear differences from the presumed prototype, it seems likely that the subject would have been recognizable on the basis of the figure’s pose and attributes.

Display Contexts

While the subject of Meleager was represented in numerous contexts in Roman society, large-scale sculptures depicting the hero are primarily attested in civic settings and in private villas. Statues of Meleager may also have been employed in the funerary sphere.

Public Sphere

During roughly the first three centuries of the Roman empire, large-scale (i.e., life-size and larger) sculptures adorned the facades and interiors of major public buildings, including [glossary:thermae], gymnasia, and theaters, as well as [glossary:nymphaea], libraries, and city gates, among other structures. In such settings, statues were often combined in programmatic displays that carried a larger thematic message to communicate to the viewer how the space was used. As a result, the subject of any given artwork had to be clearly recognizable and appropriate to the locale according to the aesthetic principle of [glossary:decor] or [glossary:decorum]. A relatively limited number of statuary types whose meanings were readily apparent were widely employed, thus making them “the visual equivalent of clichés.”

Sculptures reflecting the basic Meleager statuary type have been found in several public contexts. The Copenhagen Meleager (see fig. 4.8), for instance, was discovered in a Roman theater in Monte Cassino, roughly eighty miles southeast of Rome. A statue of Meleager might have been considered appropriate for a theater because he was the subject of a play by Euripides (now lost), which introduced the love story between the hero and Atalanta.

The Cyprus Meleager (see fig. 4.10) was found at Salamis on the island of Cyprus in a gymnasium, a characteristically Greek institution associated with athletic training and philosophical discussion. It was discovered along with numerous fragmentary statues representing deities and mythological figures, as well as several possible portraits. This work, however, exhibits softer modeling and a more youthful appearance than many of the other sculptural renditions of the hero. A third example, which was found in the Hadrianic baths at Leptis Magna (in modern-day Libya) and is dated to the Hadrianic period, is now located in the Assaraya Alhamra Museum in Tripoli (fig. 4.16; henceforth referred to as the Tripoli Meleager). Roman baths similarly included spaces designed specifically for exercise, such as [glossary:palaestrae].

Based on the discovery of the Cyprus and Tripoli statues in a gymnasium and a bath complex, respectively, it is possible that both were intended to convey messages pertaining to the use of such spaces for athletic training and physical exertion. Zahra Newby has identified a diversity of idealized, athletic male bodies represented in the sculptures and mosaics of these types of buildings, which included images of gods and heroes as well as portraits. Newby has argued that such images offered the male bather and athletic participant different physical models with which he could identify himself, ranging from the slender youth to the burly, mature man.

The Chicago Meleager could similarly have been displayed in one of the aforementioned monumental public settings, where its over-life-size scale would have increased its legibility to viewers. If it appeared in a theater, it might have conveyed the various dramatic themes associated with the hero’s myth, including his bravery and courage, his romantic relationship with Atalanta, and his tragic demise. If it was installed in a bath complex or gymnasium, the figure’s heroic nudity and toned physique would have reinforced the work’s suitability for a space used for athletic engagement. Might the hero’s now-missing weapon, the spear, have evoked for the viewer the narrower, bronze-tipped form of projectile used in Greek athletics, the javelin? The depiction of Meleager in a moment of rest after slaying the Calydonian boar could certainly have offered viewers a model of physical excellence and manly courage, not unlike the statues of gods, other heroes, and athletes frequently employed in such contexts.

Private Sphere

Another possibility is that the Chicago Meleager was displayed in a well-appointed domestic setting, perhaps a component of a larger assemblage comprising wall and ceiling paintings, floor mosaics, and other furnishings. Such domestic collections were often more diverse than those in public buildings in terms of subject matter, scale, style, and medium, although they were still expected to adhere to the principle of decorum.

Large-scale statues are infrequently found in the remains of Roman houses, and where attested they appear to be associated with wealthy, elite patrons. Statues depicting Meleager are attested in at least two Roman villas. One example was discovered in a back room in a late Roman villa in Antioch, along with a larger cache of portraits and sculptures representing mythological subjects. This work, which exhibits soft modeling and a youthful appearance that resembles that of the Cyprus Meleager, has been dated to the late second century A.D.

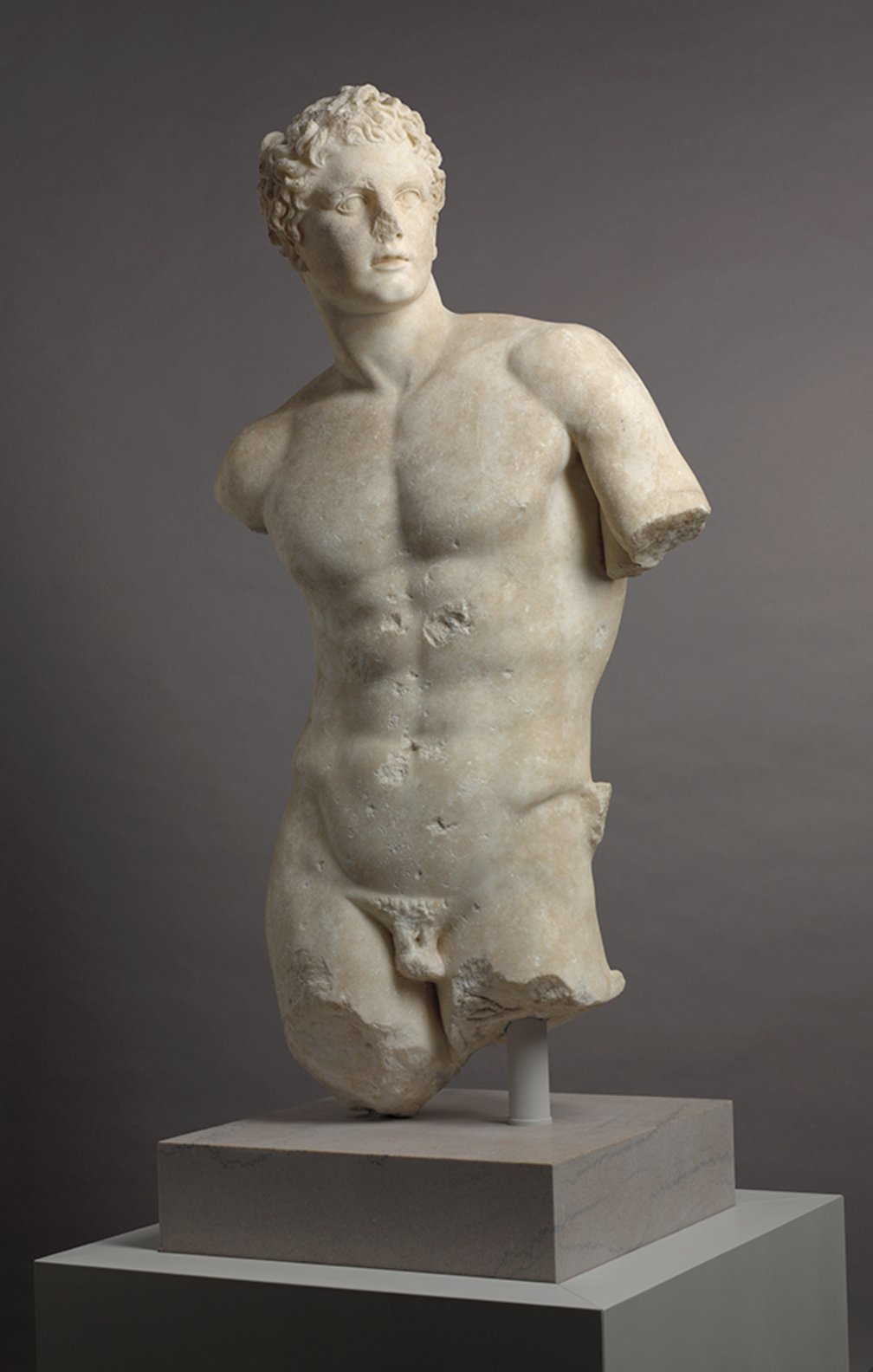

The Berlin Meleager, which is heavily restored, was discovered near the remains of a villa on a small promontory in Santa Marinella, Italy. In close proximity was later found another large-scale statue of a heroically nude male, which is in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is currently dated to the first or second century A.D. (fig. 4.17). The Harvard statue had long been identified as an image of Meleager, leading scholars to hypothesize that the two sculptures may have been commissioned jointly or that one might have been made to emulate the other, perhaps with the intent of creating a pendant group. While the Harvard statue has recently been reclassified more generally as a youthful hero or god, it is still possible that the two works could have functioned as pendants within the villa setting, as both depict muscular, youthful male figures in the costume of heroic nudity and posed in a contrapposto stance. If the Chicago Meleager was displayed in a Roman domestic context, it would likely have found a suitable home in a lavish townhouse or villa, perhaps in a [glossary:peristyle]. The peristyle of the Roman villa was frequently designed to echo the form of a Greek gymnasium, after which it could also be named. The gymnasium was a popular parallel due to its connection to Greek athletics as well as Greek philosophical instruction and discussion, one of the main activities associated with the villa lifestyle and its emphasis on [glossary:otium]. To further evoke the atmosphere of the gymnasium, statues of idealized, nude male figures, including athletes, gods, and heroes, were displayed in the peristyles and porticoes of some villas.

Funerary Sphere

Finally, it is possible that the Chicago Meleager served a funerary function. The appropriateness of the subject of Meleager for the funerary setting is suggested by the fact that, beginning in the second century A.D., episodes from his myth are represented on Roman sarcophagi more frequently than those of any other Greek hero. In this format, he rarely appears in the same pose in which he is shown in sculptures in the round; sarcophagi typically depict him slaying the boar (see fig. 4.6), although other scenes from his story are also attested.

This emphasis on the hunt and the hero’s valiant defeat of the boar is partly a result of the long-standing association of hunting with heroic excellence and military courage. Hunting for sport had been practiced for centuries prior to the Romans, not only in dynastic Egypt and in the ancient Near East, but also in archaic and classical Greece down through the Hellenistic kingdoms. By the reign of Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14), hunting for sport had become a popular pastime of elite Romans. It was not until the late first century A.D., however, that hunting came to be viewed in Roman society as a means of demonstrating one’s [glossary:virtus], which had previously been associated primarily with military prowess. In turn, the heroic connotations of hunting led to the increased popularity of hunting imagery, which was thought to reflect the virtues of manly excellence and courage that were also correlated with military experience.

Based on the popularity of hunting imagery in the imperial period, it is possible that the Meleager statuary type would have been employed as the portrait body of a deceased man who was represented in the guise of the hero. Such heroically nude portraits, which combine an individualized head with an idealized, typically youthful, nude body, are frequently associated with funerary contexts, particularly tombs.

There is a small, tentatively identified corpus of portraits in the round that might depict individuals in the guise of Meleager, as well as a similarly small number of portraits depicting individuals in the guise of unidentified hunters, which include such attributes as the hunting dog, tree-trunk support, and chlamys, all of which are associated with Meleager. In the absence of information about the contexts in which such portraits were found, however, it is not possible to say with certainty whether any served a specifically commemorative function as a funerary portrait.

With regard to the possibility that the Chicago Meleager served as the statuary body for such a portrait, one must consider the fact that its head appears to have been repaired or replaced at least twice in antiquity. While the surface of the neck suggests that the original head was unintentionally broken off, it is unknown whether it was then reattached or if a new head (depicting either the hero or the likeness of an individual) was added at a later date. In either case, the selection of the Meleager statuary type for a funerary portrait could have provided surviving family members with an appropriate means of remembering the deceased by commemorating him in the guise of a heroic exemplar of Roman male virtus. Indeed, such a selection might even have been intended to put the deceased on a par with the hero by implying that his excellence and achievements (whether in hunting or otherwise) were equivalent to Meleager’s.

Conclusion

The Chicago Meleager can be identified as a representation of the hero based on its formal and iconographic similarities to other Roman statues depicting this subject. Although it exhibits some minor variations from the basic statuary type, these can probably be attributed to the sculptor’s creative freedom or the patron’s tastes. As a large-scale sculpture, it seems most likely that the statue was displayed in a major public building, such as a bath complex or gymnasium, where its over-life-size dimensions and toned physique would have made it an appropriate subject for a space used for athletic training and physical exertion. However, it might also have appeared in a domestic setting, specifically the peristyle of an elite villa, where it would have evoked the Greek gymnasium and its associations with athletics and philosophical discussion, in order to enhance the viewer’s experience of otium. In either context, it is likely that the figure’s heroic nudity, idealized body, and now-missing attributes, which might have included some combination of the spear, the hunting dog, the boar’s head, and the rock, would not only have allowed for his identification by viewers, but would also have evoked ideas of the hero’s physical prowess, athleticism, and masculinity. Finally, it is possible, although less plausible, that the Chicago Meleager could have been employed in the funerary sphere, functioning as the statuary body for a portrait of an individual in the hero’s guise. Regardless of its ultimate function, the use of iconography associated with the hunt might have suggested that the deceased individual embodied the virtue of heroic excellence that was related to both hunting and military experience.

The Chicago Meleager has long been assigned a date of 50 B.C., yet based on its general formal and stylistic similarities to the comparative examples discussed above, a revised date in the first or second century A.D. seems reasonable. The new date that is proposed here corresponds to the dates that have been assigned to the majority of the other examples of the Meleager statuary type as well as to the broad period in which such large-scale sculptures were being produced in the Roman world, primarily for public display but also less frequently for private, typically elite consumption.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object is an over-life-size male nude depicting the Greek hero Meleager. With the exception of the proper left arm, the sculpture was carved in the round from a single block of marble (fig. 4.18). A number of features visible to the naked eye suggest that the marble is Pentelic, and technical analysis has confirmed this determination. Toolmarks are visible in abundance across the surface. The object is highly fragmentary and has sustained considerable losses, several of which have been restored with plaster. The circumstances surrounding the missing head are perplexing and raise a host of questions about the object’s history and the sequence of events leading up to its burial. Root marks, superficial staining, and excavation-related damage provide evidence of antiquity. Analysis has confirmed that the [glossary:chlamys] was once polychromed. During its time in the museum’s collection, the object has undergone only minor surface cleaning.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

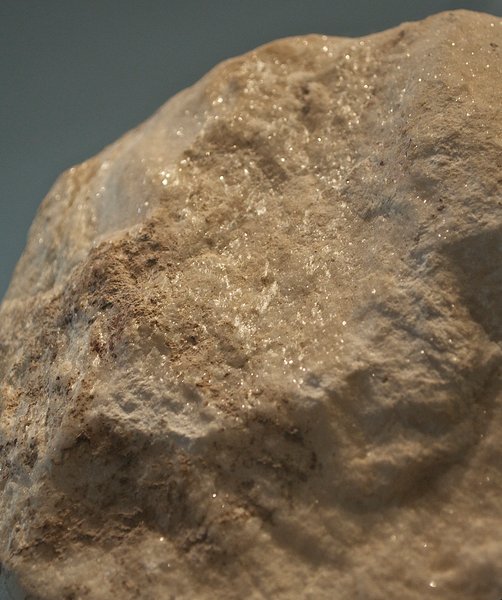

The marble is a warm, bright white with an ivory tone at the surface. The stone exhibits weak foliation corresponding to its premetamorphic bedding, in the form of dark, vertical striations that are most prominent on the legs (fig. 4.19). A large chlorite inclusion is visible on the back proper left edge of the chlamys, adjacent to the shoulder (fig. 4.20). The telltale glint of [glossary:phyllosilicates] is visible in the damaged area of the proper right shoulder (fig. 4.21).

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (very abundant); opaque minerals (traces); pyrite, FeS2 (traces); quartz, SiO2 (traces)

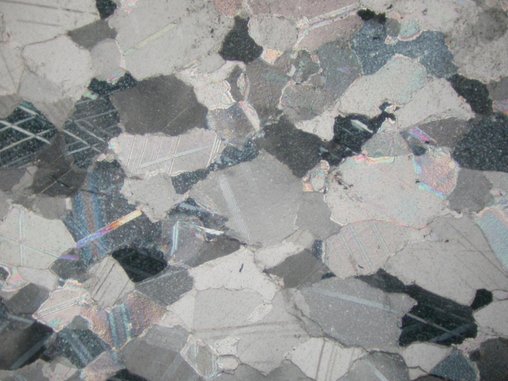

Petrographic Description

A semicircular fragment roughly 2.6 cm high by 1.4 cm wide was removed from the back of the object, from the outside edge of the base on the proper left side, approximately 5 cm from the bottom. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 1.28 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic, slightly [glossary:lineated]

Calcite boundaries: [glossary:embayed]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some inter- and intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 4.22

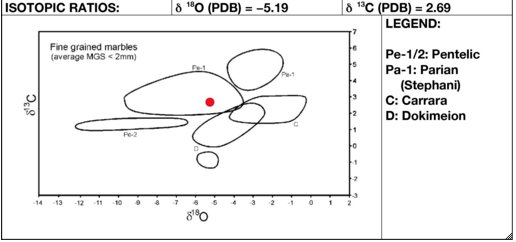

Provenance

Marble type: Pentelic (marmor pentelicum)

Quarry site: Mount Pentelikon, Athens, Greece

The determination of the marble as Pentelic was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 4.23

Fabrication

Method

The entire object, with the exception of the proper left arm, was carved in the round from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

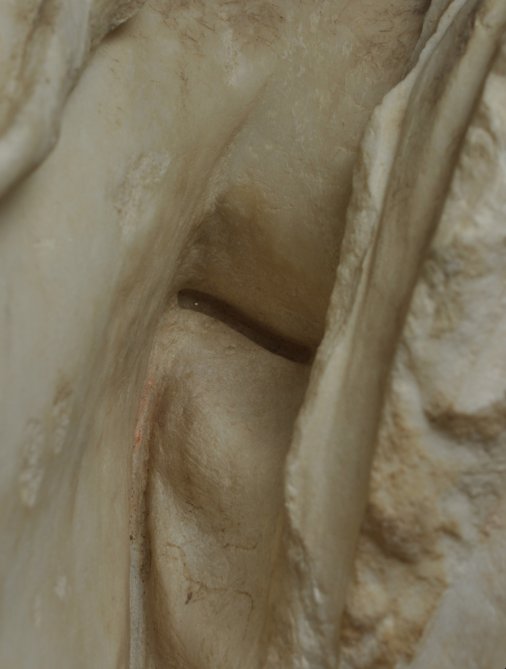

The proper left arm from the hand to just above the elbow was carved separately and attached by means of a metal pin or dowel to the upper arm of the larger sculpture. The pin used to affix and support the limb remains embedded in the stone and is square in cross section. For additional support the sculptor incorporated a cross pin, a remnant of which can also be seen (fig. 4.24).

The topography and angle of the join face on the proper left arm suggest that a straight butt join was used, forcing the metal pin to bear the weight of the arm. The portion of the chlamys that wraps around the arm and extends over the join served a limited mechanical function as a de facto recessed socket and a substantial aesthetic function in disguising the join.

[glossary:Keying] on the surface of the join, which would have provided tooth for an adhesive, indicates that the sculptor wished to reinforce the weight-bearing capacity of the pin and cross pin. Indeed, a large quantity of cementing material, protected by the overhang of the chlamys, remains adhered to the join face (fig. 4.24). The keyed surface of the join also appears to have been abraded, which raises the possibility that the arm once bore a later addition, perhaps a restoration, that is now missing.

The angle of the pin, together with the angle of the join face, indicates that the missing arm would have extended away from the body. An attribute held in the proper left hand with a point of contact on the base of the sculpture, such as a staff or spear, might have functioned as a buttress, offering extra structural support for the extended arm. No corresponding point of attachment for such an attribute has been found on the surface of the base, but, since the relevant portion of the base is a plaster restoration, it is possible that such a contact point did exist on the lost fragment of the original base.

The proper right arm is also missing, but the jagged contours around the shoulder, as well as vestiges of stone on the proper right hip that are shaped very much like fingers (fig. 4.25), suggest that this arm was carved from the same parent block of stone as the rest of the sculpture.

The evidence regarding the missing head presents a mystery. The break across the neck is reasonably flat and somewhat resembles a straight butt join. While it is difficult to discern through the encrusting rootlets, the surface of the break appears to have been keyed, albeit sparingly. Generally speaking, straight butt joins through the neck with keyed surfaces most often indicate that the head has been replaced. This break surface, however, does not appear to be flat by design but rather displays the slightly undulating topography more typical of a natural break. This suggests that the original head was unintentionally broken away from the body and was then reattached. A deep gouge extends into the break surface from the back of the neck toward the center, but as the exposed marble in this area has the same appearance as other excavation-related damage elsewhere on the sculpture, it is unlikely that this gouge was connected to any kind of intervention by a sculptor or restorer.

Two holes were drilled into the break surface of the neck, presumably for pins or dowels. Indeed, the hole on the proper left side retains an iron fitting (fig. 4.26). Although heavy incrustation of corrosion products around the metal fitting prevents a clear identification, it seems to comprise a relatively thin pin with some kind of square fastener at the top. The hole on the proper right side appears to have been excavated or cleaned out relatively recently, judging by the fresh, bright-white surface of the interior, but both holes nevertheless retain faint traces of root marks, suggesting that both were drilled before the sculpture was buried. The excavation of the hole on the proper right side raises the possibility that a replacement head may have been attached during a postdiscovery restoration campaign, perhaps at the same time as a restoration of the proper left arm.

The position of the two holes is extremely puzzling. If the original head was repaired or replaced, the expected location for a dowel hole would be in the exact center of the neck. If the head was repaired or replaced a second time, the sculptor would most likely have made use of the existing hole; if this was a technical impossibility, the second hole would have been drilled to one side of the first hole, as close as possible without compromising the structural integrity of the neck. But both of the holes are off-center.

Confounding the matter further is the presence of a bronze key that has been inserted into the back of the neck, the terminus of which appears to point toward the hole with the existing iron pin (fig. 4.27). The function of this key is not entirely clear. It could be a modified form of pin or [glossary:cramp] employed to reattach the original head or newly attach a replacement head. Or it could have been inserted at a later date in order to provide reinforcement or support to the existing pin.

Unfortunately, it is not feasible given the existing evidence to know precisely what occurred and in what sequence. The root marks across the surface of the break and in the interior of the dowel holes make it clear that the object was buried without a head attached sometime after having been drilled and pinned at least twice. Taking all the variables into account, it seems most probable that the original head was carved from the parent block of marble at the same time as the rest of the sculpture. At some point, this original head was removed, either accidentally or intentionally, and at least two campaigns of either repair or replacement were carried out.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The top of the base was heavily tooled with a claw chisel. The texture on the back of the tree trunk is also consistent with the marks left by a claw chisel (fig. 4.28). On the front of the trunk, the parallel rings appear to have been carved with a broad roundel (fig. 4.29).

The sides of the wedge under the proper left foot show marks left by a flat chisel (fig. 4.30).

Traces left by a rasp or scraper are visible along the vertical folds of the chlamys in the back (fig. 4.31).

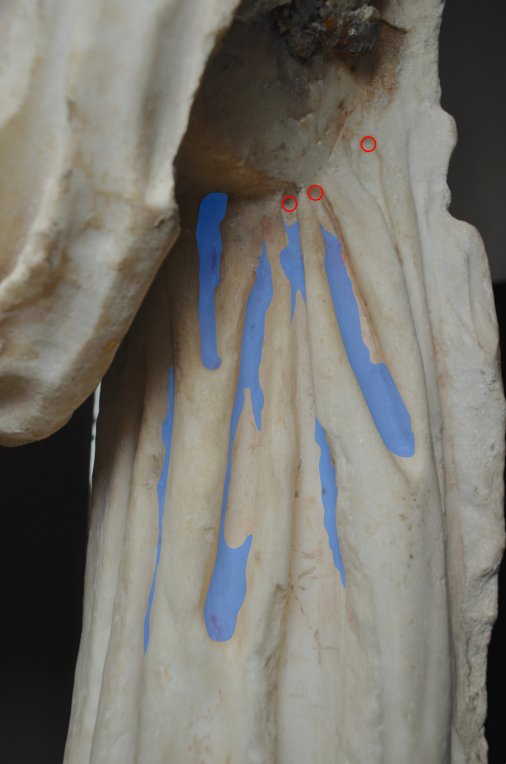

A drill 4.6 mm in diameter was used to delineate the proper left arm and the chlamys as separate from each other and the rest of the body (see fig. 4.32). A drill of the same diameter was also used to create the folds of the chlamys, as evidenced by the circular depressions at their end points (fig. 4.33).

The navel was rendered using a compass and a punch.

A burnished surface visible on the upper portion of the chlamys and on the neck suggests an original polish, which would have been realized using a slurry of an abrasive powder such as pumice.

The sculptor made use of [glossary:struts], the remains of one of which can be seen on the proper right hip (fig. 4.34).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Significant amounts of an orange-red pigment are visible to the naked eye. The pigment is concentrated in the folds of the chlamys below the proper left arm and in some protected areas in the sweep of the chlamys across the chest. These vestiges of pigment appear in the form of staining embedded within the stone along the vertical surfaces of the carved grooves, and also as discrete deposits of colored particulate matter in the folds (fig. 4.33). Samples were taken from the thicker deposits and were found to be lead red over a preparation layer of lead white. These findings indicate that the entire cloak was once painted a deep orange-red color. It is unclear whether the layer of lead white served as a priming layer or whether it was applied to modify the appearance of the overlying red.

No evidence of polychromy was detected elsewhere on the sculpture; therefore, it cannot be determined to what extent the rest of the object might have been colored.

Visual examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of gilding or other embellishment.

Condition Summary

The object is fragmentary, comprising five primary fragments: (1) the proper right portion of the back of the base and the proper left foot up to the ankle, (2) the proper left portion of the back of the base and two-thirds of the tree trunk, (3) the proper right lower leg from the ankle to the knee, (4) the proper left lower leg from the ankle to the knee, and (5) the upper portion of the sculpture, including the body from the knees to the neck, the chlamys, and the top of the tree trunk.

The primary fractures resulted in conspicuous losses, several of which have been restored with large plaster fills: the front of the proper left knee, the front of the base, the front of the tree trunk along the break line, the back of the proper right knee, and the back of the proper left knee. The plaster fills were textured and toned in an effort to emulate the surrounding stone, where necessary even matching areas of discoloration.

The object is missing the proper right foot, the proper right arm, the head, the proper left arm from just above the elbow, and the upper portion of the chlamys in the back. The front of the proper left foot is also missing, with only a small portion of the little toe remaining. Ovoid lacunae are present on the folds of the chlamys in both the front and the back. The genitals are missing, and a deep hole has been drilled where the penis should be.

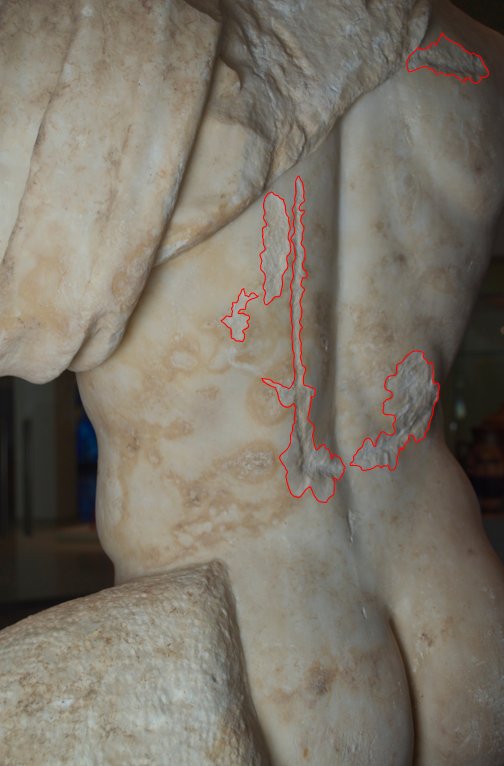

The sculpture displays other surface anomalies, including extensive [glossary:spalls] and gouges that may be related to the object’s discovery. Two particularly deep gouges are visible: one on the proper right flank, which is accompanied by deep associated losses; the second traversing the length of the back on the proper left side (fig. 4.35). Surface spalling is extensive, and scratches are present overall.

The iron pins in both the proper left arm and the neck exhibit considerable scale and corrosion, which have left prominent staining on the stone.

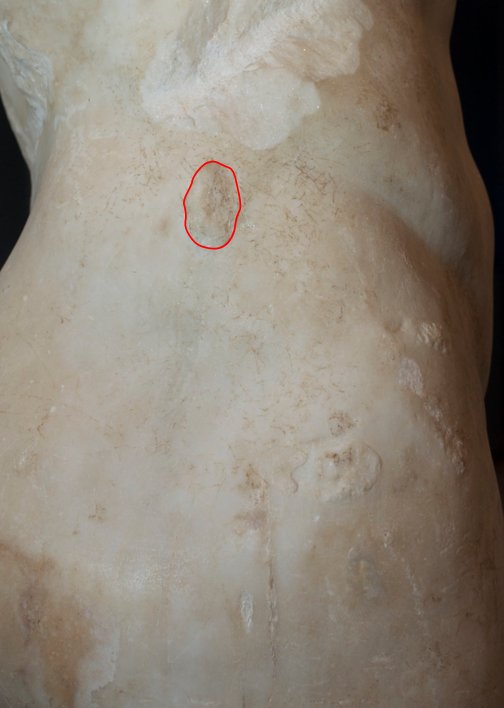

Rootlets—desirable evidence of antiquity—are present on the front of the sculpture on the lower portion of the tree trunk, on the portion of the original base around the tree trunk, along the front of the thighs, across the torso, and around the chlamys below the neck. Signs of root incrustation are sparser on the back of the object and are not seen at all on the buttocks or the backs of the legs.

Pronounced staining is visible on the proper right side of the tree trunk above the knot and on the outside of the proper left thigh. Lesser staining of a similar hue can be seen on the backs of both thighs and on the proper right buttock. Circular patches along the back of the torso are consistent with exposure during burial to groundwater containing humic acid.

Conservation History

While in the museum’s collection, the object has received one recorded treatment, in 1993, the goal of which was to prepare the object for exhibition in the galleries. The entire surface was cleaned using aqueous methods supplemented with a nonionic surfactant. Following cleaning, the surface was neutralized with deionized water.

The sculpture was most likely unearthed in its fragmentary state and reassembled immediately thereafter. It is probable that both mechanical and adhesive means were used to rejoin the fragments. A metal support is visible between the proper right ankle and the base. The appearance of the plaster fills is very much in keeping with a nineteenth-century restoration aesthetic; however, it is unknown whether they were part of the original campaign of restoration following excavation or whether they were introduced at a later date.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini