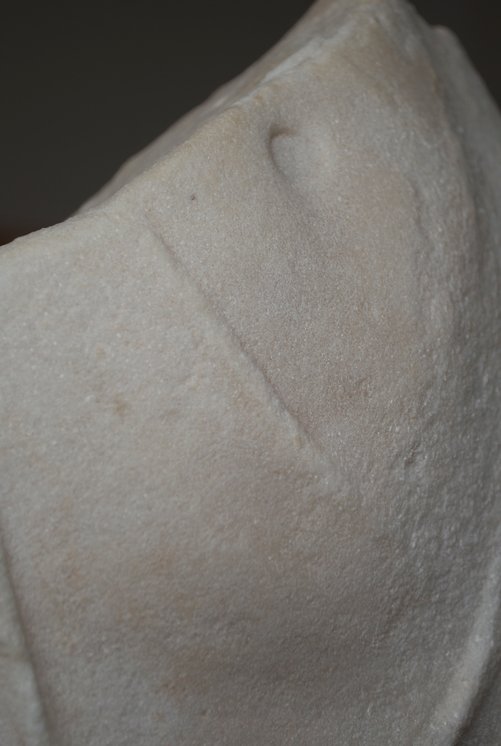

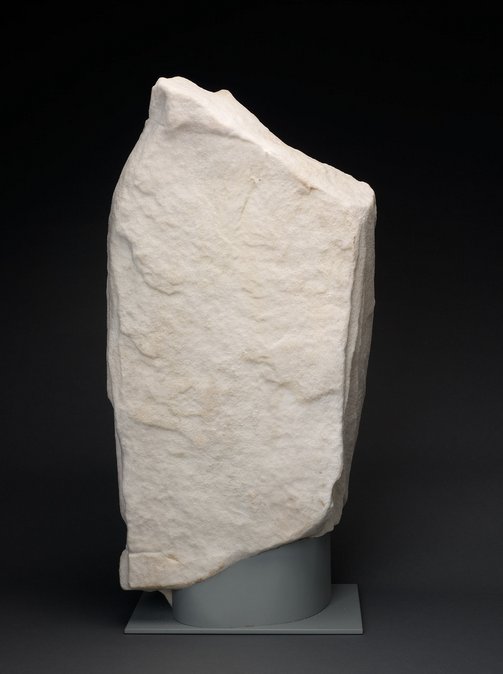

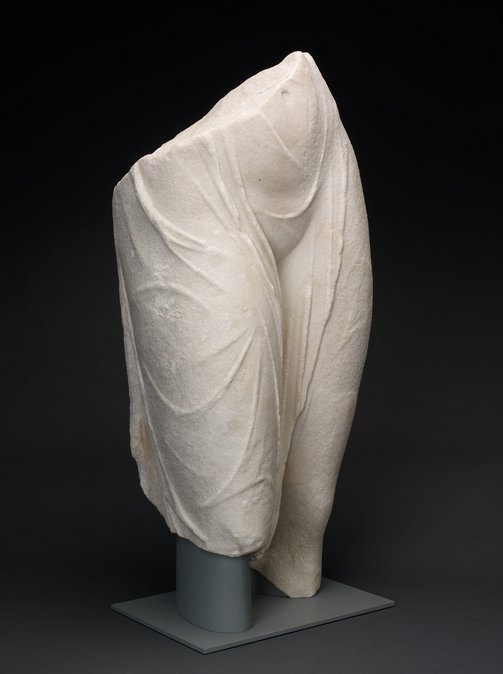

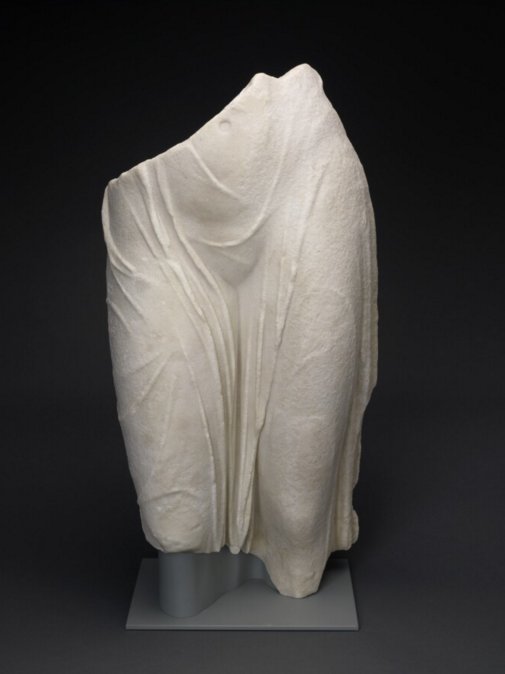

This delicately carved fragment of a female figure, with its clinging drapery and sensuous pose, reflects a statuary type that was used frequently in the Roman world to represent Venus, the Roman goddess of love, sexuality, and beauty (equivalent to the Greek Aphrodite). The over-life-size fragment preserves part of the torso and the lower body, including the thighs, the knees, and the upper part of the proper left lower leg. The verso of the figure is largely flat and cursorily worked, perhaps left incomplete for the purposes of display in a setting in which it would not be seen entirely in the round, such as in a niche (fig. 3.1). The work was carved from fine Parian marble, which today has a sugary, crystalline appearance that is particularly apparent in the areas of breakage.

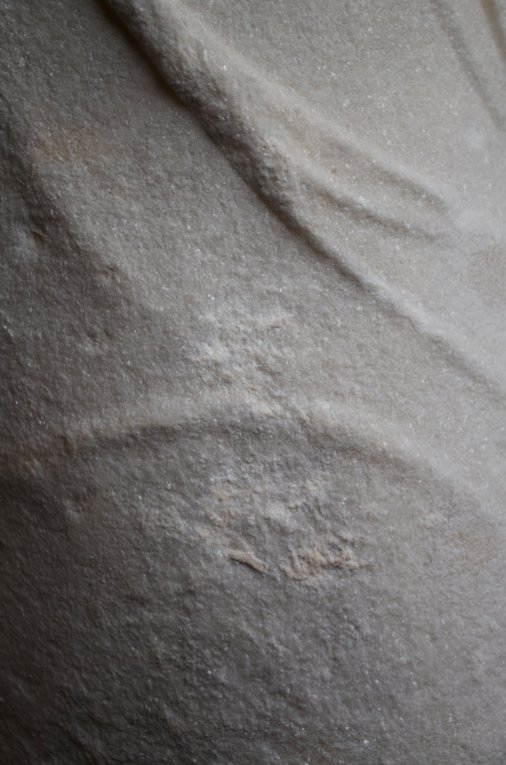

The masterfully sculpted figure wears a sheer [glossary:chiton] that leaves little to the imagination as it defines the body while calling attention to the figure’s curves. The thighs seem to press against the diaphanous fabric, which is indicated only by shallow, ridged folds forming quasi-[glossary:catenaries] (fig. 3.2). The subtle swelling of the abdomen and genitalia is similarly highlighted by the taut fabric, which also reveals the navel. The chiton itself is made apparent by the more voluminous, vertical folds of fabric that fall between the legs. In its [glossary:contrapposto] stance, with the proper right leg extended forward and the proper left hip raised, the figure exudes a sense of graceful, controlled movement appropriate to an image of the goddess.

Based on the figure’s [glossary:chiastic] pose and the representation of the sheer, clinging chiton, it can be concluded that this statue is an example of the type known as the Louvre-Naples Aphrodite, also known as the Louvre-Fréjus type. It is named after the location of the best-known example, which is currently in the collection of the Musée du Louvre in Paris, and its findspot, which was previously thought to be Fréjus, France, but is now believed to be Naples, Italy (fig. 3.3).

In this statuary type, Aphrodite is typically shown in a sleeveless, ungirt chiton, standing in a hipshot pose. In her raised right hand, the goddess gently holds the corner of a [glossary:himation] that is draped across her back, either lifting it to cover herself or letting it fall behind her. This movement appears to cause the chiton to slip from her left shoulder, revealing the left breast. In numerous cases, however, the left breast remains covered, a variation that might have been introduced in the Roman period. The left arm, which is usually lowered and extended forward, might have held an apple. This attribute alluded to the goddess’s prize following her victory in the Judgment of Paris, the contest which ultimately led to the outbreak of the Trojan War and the eventual founding of Rome. The head, although not preserved in most examples, appears to have been gazing slightly downward and toward the figure’s left, given the positioning of the neck and upper body.

On the basis of the numerous surviving examples of this statuary type, it is generally thought to be modeled on a now-missing, earlier Greek statue of the goddess that was well known in antiquity. Although the identity of its sculptor is unknown, the extant examples generally reflect features associated with the classical Greek style of the fifth century B.C., including the contrapposto stance and the depiction of sheer drapery. In particular, the delicate rendering of the chiton is thought to evoke the work of Master E of the Nike parapet at the temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis in Athens, who is associated with the relief of Nike (the Greek personified goddess of victory) adjusting her sandal (fig. 3.4). Most frequently, the late fifth-century B.C. sculptor Kallimachos, who was renowned for his sensitive carving of sheer drapery, has been identified as the possible sculptor of the prototype, which might have been cast in bronze. Despite the assumptions regarding the possible Kallimachean attribution of the statuary type, attempts at identifying the artist and date of the original statue remain inconclusive.

Examples of this statuary type, including Fragment of a Statue of Venus (henceforth referred to as the Chicago Venus), are often associated with the representation of Venus in her role as [glossary:Genetrix], or mother, specifically of the Roman people and the imperial family. With its voluptuous form and diaphanous drapery, this statuary type offered an attractive image of the goddess that alluded to her associations with fecundity, sexuality, and maternity and that was suitable in a variety of contexts.

The Origins of Venus Genetrix

Venus had long been worshipped in Italy as a native goddess, and by the early third century B.C. she was venerated in the city of Rome. Although Venus was worshipped under numerous guises, including those associated with her domain of fertility, beauty, and seduction, by the first century B.C. she was viewed especially as a goddess of warfare and provider of military victory. In this aspect, she was venerated and honored by successful generals, such as Sulla (138–79 B.C.), Pompey the Great (106–48 B.C.), and Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.), who claimed the goddess as their patron deity and protector. This emphasis on the goddess’s martial functions distinguished her from the Greek goddess Aphrodite, who, although associated to a certain extent with war, was seen primarily as a goddess of erotic love and female sexuality. Additionally, the martial role linked her to Mars (equivalent to the Greek Ares), the Roman god of warfare and agriculture, with whom she shared an erotic relationship.

Despite these distinctions, over time Venus was assimilated to Aphrodite and absorbed aspects of the Greek goddess’s background. In particular, Aphrodite was considered to be the mother of the Trojan hero Aeneas, who settled in Italy following the fall of Troy, and so was the grandmother of Ascanius (also known as Iulus), the founder of the city of Alba Longa. This made her an ancestor of the royal line of Alba Longa, and thereby of Romulus and Remus, the twins associated with the mythical founding of the city of Rome. Consequently, Aphrodite was viewed as an ancestor of the Romans, a role that also came to be associated with Venus, who was described as the Aeneadum Genetrix, or mother of the Aeneadae (Romans).

Moreover, the [glossary:gens] Iulia (Julian family), one of the oldest and most distinguished patrician families in Rome, also claimed their direct descent from Ascanius/Iulus (from whom they derived the name of their clan), thus making Venus their direct ancestor. Indeed, the Julian clan’s most famous member, Julius Caesar, prominently asserted his divine ancestry in a massive building project known as the Forum Iulium, which contained a temple to Venus Genetrix. Although it is presumed that Caesar’s forum was initially intended to function as a [glossary:monumentum] to his conquests in Gaul, it appears to have taken on new meaning following his victory in 48 B.C. at the battle of Pharsalus over his former ally Pompey the Great. Prior to this battle, Caesar is said to have vowed to build a temple to Venus Victrix (Venus the Victorious) in the event of his success. However, in 46 B.C., Caesar’s still-unfinished temple to Venus was dedicated not to Venus Victrix but rather to Venus Genetrix, a new epithet not previously assigned to the goddess. The appellation Genetrix not only retained the references to military victory associated with her epithet Victrix, but it also emphasized the goddess’s genealogical ties to both the Roman people and the Julian family.

The Images of Venus Genetrix

According to Pliny the Elder, the Greek sculptor Arkesilaos was commissioned to create the statue of Venus Genetrix displayed in Caesar’s forum, which is generally understood by scholars to refer to the cult statue erected in the temple. Although the appearance of the republican cult statue is not known, it was previously thought that it might have resembled the Louvre-Naples statuary type. This identification was based on the appearance of a comparable image of Venus on coins and medallions carrying the inscription VENERI GENETRICI. However, numismatic evidence linking this statuary type to the epithet Genetrix is not contemporary with Caesar’s temple. Consequently, evidence of the Arkesilaon statue has been sought in late republican and early imperial images, particularly on coins and monuments. It has been suggested that the republican cult statue might have been fully and modestly clothed, with her son Cupid on her shoulder to indicate her role as Genetrix. A similar image is found on a relief, perhaps from a nonextant altar or other monument of Julio-Claudian date, depicting Venus in the pediment of the Augustan temple of Mars Ultor, where she is shown immediately to the left of Mars in the center (fig. 3.5). Alternatively, it might have resembled the image of Venus appearing on coins minted by Julius Caesar shortly after the temple’s dedication, which depict the goddess holding a diminutive, winged Victoria (the Roman personified goddess of victory) in her right hand and a scepter in her raised left hand (see fig. 3.6), thus alluding to the goddess’s dual roles as Caesar’s ancestor and patron deity, particularly in warfare.

While the Louvre-Naples type cannot be associated with the republican cult statue of Venus Genetrix, it is possible that the cult image was later changed to a different statuary type after a fire destroyed the temple (and presumably also the statue) in the last quarter of the first century A.D. Following the temple’s restoration, perhaps by Emperor Domitian (r. A.D. 81–96), it was rededicated in A.D. 113 by Emperor Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), an act that might have involved the dedication of a new cult statue. Although evidence is similarly lacking for the appearance of a possible new Flavian or Trajanic cult statue, the work might have been updated at this time to a form more suited to the sensibilities of the period.

Under Emperor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–38), the cult of Venus enjoyed increased prominence. On imperial coins produced during his reign, the Louvre-Naples statuary type was selected to depict Venus in her role as Genetrix. For example, on a denarius portraying Empress Sabina (A.D. 83/86–136/37), Venus is depicted on the reverse, where she is identified as Genetrix in the inscription (VENERI GENETRICI) (fig. 3.7). More important, she is shown wearing the diaphanous drapery and standing in the hipshot pose characteristic of the Louvre-Naples type. The identification of this type is further reinforced by the depiction of an apple, the goddess’s prize in the Judgment of Paris, in her left hand. Here, however, both breasts are covered, perhaps in order to portray a more modest image suitable for suggesting a correlation between the empress shown on the obverse and the goddess on the reverse.

The Louvre-Naples type continued to be employed on coins produced in the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93) to emphasize themes of fecundity and abundance. For instance, on an aureus depicting Empress Faustina the Elder (A.D. 100–140/41), the reverse includes an image of Venus that clearly reflects the Louvre-Naples type, including the diaphanous chiton, the himation held in the elevated right hand, and the apple in the extended left hand (fig. 3.8). The inscription on the obverse (FAVSTINA AVGVSTA) is echoed in the inscription on the reverse (VENERI AVGVSTAE), suggesting an intended association between the empress and Venus as divine ancestor of Rome. Although the goddess is not explicitly identified here with the epithet Genetrix, the message of fertility and maternity is still evident due to her attractive feminine form.

Display Contexts

The Louvre-Naples type was widely employed during the imperial period in sculptures of Venus produced in diverse sizes and media. While statuettes in marble, bronze, and terra-cotta might have been created for use in household shrines, life-size and larger marble statues might have adorned a variety of religious, civic, and domestic spaces.

The specific display context of the over-life-size Chicago Venus is unknown, but its condition and form shed some light on issues related to its possible setting in antiquity. As addressed under Condition Summary in the technical report, the surface of the stone exhibits a granular texture suggestive of prolonged exposure to sunlight, which might indicate an outdoor location. An interior site cannot be entirely discounted, however. The flat profile of the verso suggests that the work was created for a setting in which it would not have been visible in the round, perhaps within a niche or a colonnade or against a wall. Taking these factors into account, there are several potential contexts in which the Chicago Venus might have appeared.

One possibility is that the sculpture was displayed in a religious setting. As noted above, numerous temples dedicated to Venus are attested in Rome, where the goddess was venerated from at least the third century B.C. onward. Although the Louvre-Naples statuary type cannot be identified with any cult images depicting Venus, it nevertheless seems reasonable that examples of the type could have appeared in a temple or sanctuary of Venus, perhaps functioning as a dedication or votive offering.

Sculptures reflecting this type might also have been employed in temples and sanctuaries dedicated to deities associated with Venus. For example, five statuettes of the Louvre-Naples type (see fig. 3.9) were found at Ostia in the sanctuary of Attis (a Phrygian solar deity), which was incorporated into the larger sanctuary of his consort, Magna Mater (the Roman equivalent of the Phrygian mother goddess Cybele). The choice of statues of this type appears to have been deliberate, given Venus’s shared domains with Cybele, who was associated not only with Troy and the Trojan origins of the city but also with military triumph. Similarly, a statue of the Louvre-Naples type was found in the temple of Magna Mater on the Palatine hill in Rome. Thus, Venus’s role as Genetrix of the Romans might have allowed for her association with Cybele/Magna Mater, who had been venerated in Rome since the republican period.

Second, it is possible that the Chicago Venus was displayed in a public setting in a large-scale building or monument. Aphrodite and Venus were considered appropriate for a variety of such structures, particularly those involving water, like monumental fountains ([glossary:nymphaea]) and bath complexes ([glossary:thermae]), due in part to the former’s origins in the sea as well as both goddesses’ associations with bathing and the cultivation of the female body. Moreover, this image of Venus’s voluptuous body revealingly clad might also have conveyed a distinctly imperial message by correlating her associations with fertility, sexuality, and motherhood with the continuation of the Roman populace and state.

Third, the Chicago Venus could have been located in a domestic context in a well-appointed villa or townhouse. Images of Venus found in Roman homes typically depict the goddess either wholly or partially nude; this statuary type, with its revealing chiton, might have functioned as a slightly more modest, albeit still alluring, representation of the goddess. Over-life-size versions of renowned statues were a rarity, however, appearing only in the most well-to-do residences; it would therefore be somewhat surprising for a patron who could afford a large-scale sculpture of fine Parian marble to have chosen or commissioned an example with an unfinished back. Nevertheless, if it were displayed in a domestic setting, it seems likely that the Chicago Venus would have adorned the [glossary:peristyle] of an elite home, where it would have enhanced the experience of pleasure, leisure, and physical enjoyment.

Finally, the flat verso suggests the possibility that the Chicago Venus was once part of a relief from a monument or other structure, from which it was detached in antiquity. Although Venus is occasionally represented on large-scale reliefs, to this author’s knowledge none of the extant examples include the Louvre-Naples type. Consequently, this seems to be the least plausible scenario.

Roman Matrons in the Guise of Venus

The image of Venus was also employed in the medium of portraiture, specifically in [glossary:theomorphic] portraits, which combined individualized heads with idealized bodies of deities, heroes, and mythical figures. By the late first century A.D., both imperial and private women were honored in portraits that depicted them in the guise of the goddess. The body of Venus was an especially potent and patriotic symbol when paired with the likeness of an empress or other imperial woman, assimilating the goddess to the subject as the new mother of the Roman people and the imperial line. Imperial examples, which were produced in formats including full-length statues, reliefs, gems, and coins, were created not only for honorific purposes in public contexts but also for more intimate settings, in which they might be viewed primarily by members of the imperial circle. In contrast, Venus portraits of private women appear to have correlated the individual’s personal characteristics with the feminine virtues of the goddess. Frequently, such private portraits (whether depicting fully draped or wholly or partially nude bodies) are associated with the funerary sphere.

Among the extant Venus portraits, many make subtle references to the goddess through motifs such as the chiton slipping from the shoulder, long locks of hair extending onto the shoulders, or an accompanying Cupid. For example, subtle suggestions of the Louvre-Naples type can be seen in a turquoise cameo at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, that depicts Empress Livia (58 B.C.–A.D. 29) wearing a diaphanous chiton that slips from her left shoulder, albeit still covering the breast, perhaps to suggest a more appropriately modest representation of the empress (fig. 3.10). This cameo, which was probably made in the years following the death of Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14), might also have alluded to Livia’s adoption into the Julian family by Augustus in his will, thereby creating a direct genealogical connection between the empress and Venus.

A relatively small number of portraits incorporate recognizable versions of statuary bodies associated with Aphrodite and Venus, several of which include a version of the Louvre-Naples type. One such example, a slightly over life-size portrait, was found at Ostia in the so-called headquarters of the [glossary:Augustales] (fig. 3.11). Although previously thought to depict Sabina, in part due to the representation of Venus Genetrix on coins featuring the empress’s likeness, this sculpture has more recently been identified as the image of a private individual that was likely a funerary portrait.

Given the limited number of Venus portraits, particularly those incorporating the Louvre-Naples type, it seems less plausible that the Chicago Venus functioned as a statuary body. If it did serve this purpose, its context would have depended in part on whether it depicted an imperial or a private woman. The former might have been displayed in a civic setting, perhaps on a major public building or monument; the latter would probably have appeared in a funerary context as a commemorative portrait. In either case, it is likely that the portrait would have been positioned so that its unfinished verso would not have been visible to the viewer.

Conclusion

The Chicago Venus is undoubtedly an example of the Louvre-Naples statuary type, as evidenced by its sheer, clinging drapery, sensuous curves, and characteristic pose. Although the type cannot be correlated with the late republican cult statue of Venus Genetrix created for Julius Caesar’s temple to the goddess, it was adopted for the representation of Venus in her role as Genetrix by the second century A.D., as evidenced by coins issued during the reign of Hadrian. Her attractive, feminine form highlighted the goddess’s fertility, sexuality, and maternity while also suggesting the importance of those characteristics to the growth and continuation of Roman society.

The tremendous significance of Venus in Roman religious, political, and social life means that the Chicago Venus could have been employed in a variety of contexts. The condition of this particular sculpture suggests that it might have been located outdoors, and it was probably placed in a niche or other setting in which it could not be seen from behind. If it was displayed in a religious context, such as a temple or sanctuary dedicated to Venus or a related deity, it might have functioned as a dedication or votive offering. If it was connected with a civic building or monument, it would likely have adorned a structure involving water, such as a bath complex or monumental fountain. If it appeared in a domestic setting, it would probably have belonged to the sculptural assemblage of an elite villa or townhouse, perhaps sited in a peristyle garden, where the sculpture’s alluring figure would have enhanced the atmosphere of enjoyment and leisure. Finally, there is a slight possibility that the Chicago Venus was part of a portrait of a woman in the guise of the goddess. In this case, while the context would have depended in part on whether an imperial or private subject was depicted, the choice of a distinctly Venusian statuary body would have identified the individual as an exemplary Roman matron who was worthy of comparison to the goddess.

Regardless of the statue’s original function, it remains a strikingly beautiful and skillfully carved representation of the divine female form, which, despite its fragmentary state, continues to command attention and inspire admiration among viewers today.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object is a fragment of an over-life-size sculpture depicting a female figure in a [glossary:contrapposto] stance clothed in a diaphanous garment (fig. 3.12). The extant fragment was carved from a single block of fine-grained, white marble that has been identified as Parian. In its present condition, the stone shows little evidence of toolmarks; in isolated areas, however, traces of carving can be identified. No indication of [glossary:polychromy] or gilding has been detected. The granular appearance of the stone suggests an exposed or outdoor location in antiquity. Although the surface is quite fragile and prone to [glossary:exfoliation], the object is in reasonably sound condition overall. Despite the presence of several minor losses and various surface anomalies, the fluidity and masterful handling of the carving and the legibility of the drapery are clearly evident. No signs of previous restoration have been found on the object itself, but a conservation treatment was performed in the autumn of 2011 to make aesthetic improvements and to remove an intrusive and unsightly mount.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is a cool, bright white with subtle patches of brownish-red coloration in isolated areas across the surface. On the outside of the proper right thigh, a gray coloration is visible.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant)

Petrographic Description

A sample roughly 0.9 cm high by 0.6 cm wide was removed from an area of loss to the drapery at the bottom edge of the proper right side, approximately 1.5 cm below an overhang of stone at the top edge of the loss. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using [glossary:X-ray diffraction] to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 1.62 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: curved-[glossary:embayed]

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed strong decohesion.

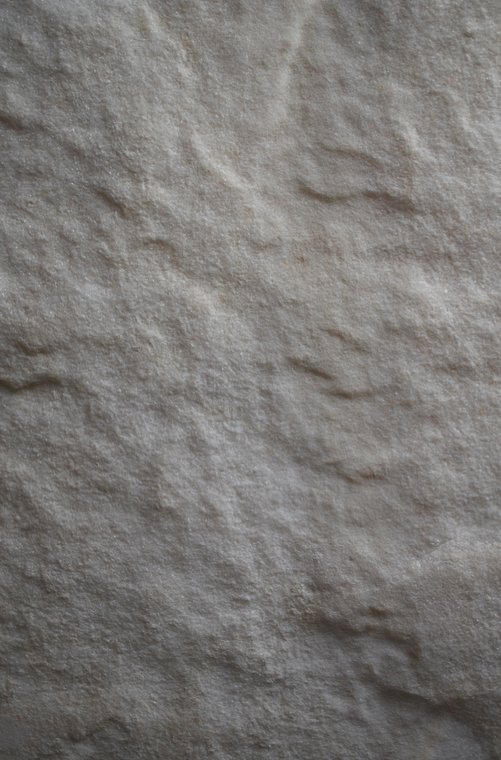

Thin-section [glossary:photomicrograph]: fig. 3.13

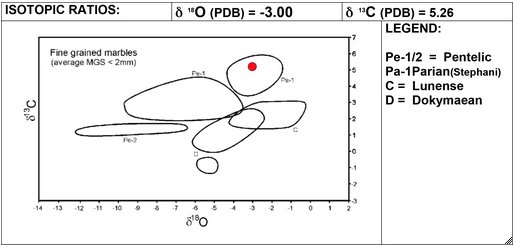

Provenance

Marble type: Parian (marmor parium)

Quarry site: Stephani, on the island of Paros, Cyclades, Greece

The determination of the marble as Parian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 3.14

Fabrication

Method

The object is a fragment of a larger sculpture whose dimensions would have been over life-size. The existing fragment itself was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

The flat profile of the verso could indicate that the sculpture was intentionally carved only on its front half, suggesting that it was created for display in a setting in which it would not have been visible from all sides. If this was the case, the sculptor might have deliberately chosen a slender slab of marble to make efficient use of the available materials. Alternatively, it is possible that the sculpture was originally part of a relief from which it was detached in antiquity.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

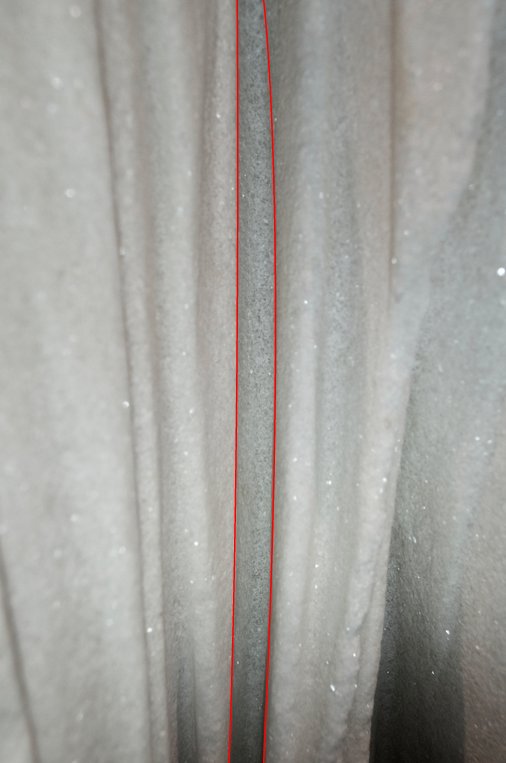

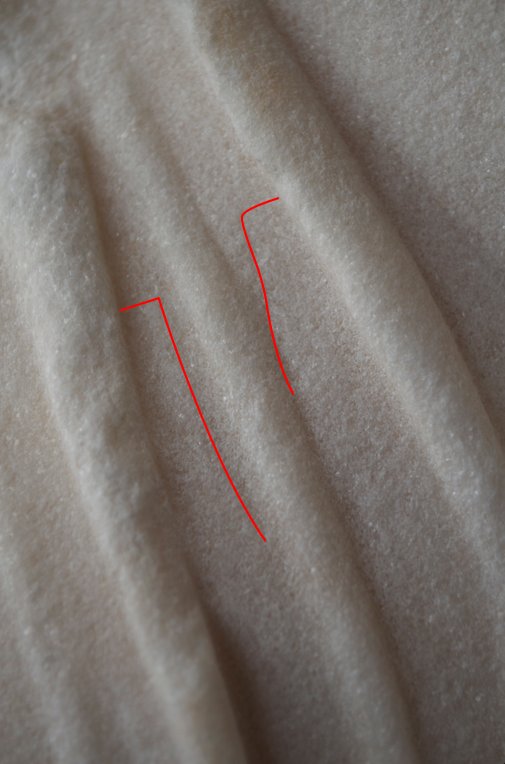

Owing to the weathered condition of the stone, very little evidence of toolmarks remains on the surface. There are, however, two intact areas of original carving: one between the drapery and the outside edge of the proper left leg and another in the centermost folds of drapery between the legs (fig. 3.15). In these areas the deep grooves carved into the stone with a roundel or channeling tool are sharply articulated, and the marble grains are flat, compact, and smooth, although the appearance of the marble in these areas is matte, not polished. These deeper areas were more sheltered from sunlight and likely more protected during burial, hence their current state of preservation. The merest hint of traces of a flat chisel can also be seen between the folds of drapery on the proper right inner thigh (fig. 3.16).

An explanation for the texture visible on the verso must be intimately connected with the fact that the surface is flat (fig. 3.17). What is unclear, owing to the degree of weathering, is how the marble came to be flat in the first place. Perhaps the back of the stone was left in its natural state, and its present appearance reflects the intrinsic [glossary:cleavage] planes of the metamorphic fabric, whose features became muted through time and exposure. Alternatively, this could be the surface as quarried, in which case the stepped surface would constitute the eroded remains of first-stage stoneworking equipment such as a pitching tool. If the sculpture was indeed removed from a relief, this texture could also be the eroded remains of the tool used to detach it.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The surface of the stone exhibits a high degree of decohesion due to prolonged exposure to sunlight and is accordingly prone to exfoliation and [glossary:dissociation] of the marble grains. The resulting granular appearance is evident overall but is most profound along the front of the proper left thigh and on the drapery hanging alongside it (see fig. 3.18). This particular texture is less pronounced along the front of the proper right thigh and in the channel carved between the legs. In contrast, the surface of the stone around the abdomen appears somewhat more dense and compact and bears a slightly waxy appearance with a light reddish-brown tone (fig. 3.19). The difference in texture around the abdomen might be attributable to the consolidative effect of repeated handling and contact during the lifetime of the sculpture. Alternatively, the difference might be explained by the presence of a weathering crust or patina.

A sizable ovoid loss is present at the outer bottom edge of the drapery on the proper left side. An associated crack emanates from the bottom edge of this loss approximately 9 cm up from the bottom and runs horizontally across the sculpture. In the front, the crack is not visible across the proper left knee but appears within the drapery between the legs. Along the side edge, the crack is quite deep. On the verso, the crack extends horizontally for approximately 4 cm before traveling diagonally down toward the bottom edge. Associated red-orange staining is apparent at the terminus of this crack. There is a second ovoid loss to the drapery at the bottom edge of the proper right side. Numerous other small losses and lacunae are present throughout, particularly in the high-relief areas of the drapery.

A variety of other surface anomalies are also in evidence. There are heavy, chalky adhesions, possibly redeposited calcium in association with organic material or roots from burial, at the outside of the proper right hip (fig. 3.20). Dark accretions are scattered uniformly across the marble, particularly at the high points of the stepped surface on the verso. A disk of what appears to be incipient [glossary:cleavage] is visible on the top edge, toward the front, near the navel (fig. 3.21). Whether this cleavage is indicative of the bedding plane of the parent sedimentary rock is not clear. There is a pronounced red-orange bloom, strongly resembling an iron stain, inside the fold of drapery at the bottom edge on the proper right side (fig. 3.22). A somewhat new-looking abrasion is present on the verso at one of the high points of the stepped surfaces. Prominent, dark particulate deposits, likely associated with the previous mounting method, are present around the bottom edge of the object and uniformly across the underside of the object.

Long drip marks indicating the movement of an unidentified fluid, invisible to the naked eye, become apparent on the verso when it is viewed under ultraviolet radiation (fig. 3.23). These marks may corroborate an exterior location of the sculpture in antiquity, or they may be evidence of a previous conservation effort.

Conservation History

Prior to 2011 there is no record of treatment for this object while in the museum’s collection.

In the autumn of 2011, the object was treated in preparation for its reinstallation in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art, in an effort to improve its overall appearance and in particular to reduce the once-heavy, circular patches of staining along the proper right thigh. Dry cleaning methods were employed, along with aqueous methods using reducing, oxidizing, and chelating agents as well as high-pressure steam. Residual staining was minimized using dry mica powders applied directly onto the affected areas.

The object was previously mounted onto a stone pedestal using brass rods, with molten lead as a fixing agent. During the course of the 2011 treatment, the object was detached from its base, and the brass rods and lead were mechanically excavated from the interior of the drill holes. The object was then given a new, removable mount consisting of a stainless-steel rod secured in an epoxy-resin cast that follows the topography of the base of the object.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini