In the early days of Rome, two forms of burial were practiced: inhumation and cremation. However, by the republican period (perhaps as early as 400 B.C.), cremation appears to have become the preferred method of handling the remains of the deceased, so much so that it was described by the senator and historian Tacitus as the “Romanus mos,” or Roman custom. While cremated remains had long been placed in simple terra-cotta urns (ollae), in the Augustan period (27 B.C.–A.D. 14), a taste for elaborately carved marble cinerary (ash) urns developed. The popularity of marble urns increased through the first century, reaching its peak during the Flavian dynasty (A.D. 69–96) and continuing on through the second century, during which time inhumation had begun to replace cremation as the primary mode of burial. This shift in practice appears to coincide with the decline in the use of urns and their replacement with richly carved sarcophagi.

Approximately 700 marble urns are known from the roughly two centuries in which they were created and employed, the majority of which were produced in metropolitan workshops in Rome. As a whole, the marble urns exhibit basic similarities in their forms and decorative motifs, yet there are considerable differences in the ways in which the motifs are employed.

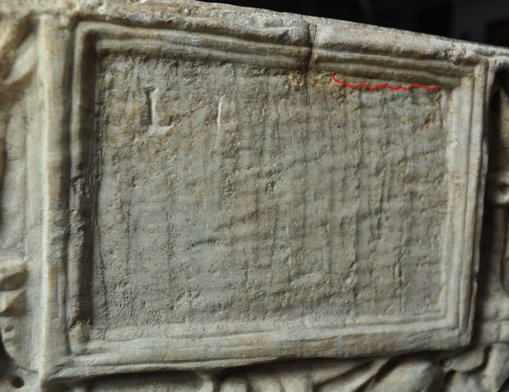

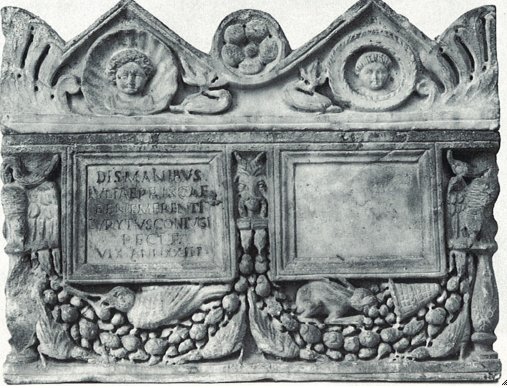

This lidded marble urn was intended to hold the cremated remains of two individuals. Containing two, similarly sized cavities in its interior, it is of a type known as a double urn. On the front of the urn decorative motifs are placed around two tabulae, or panels, each enclosed within a molded frame. Urn panels could be left blank or inscribed or painted with an epitaph. It appears that these panels were cut back or altered at some point, since there is a notable drop of material from the inner edges of the frame, suggesting their reuse and possibly the removal of a previous inscription. The proper right panel contains the beginning of an inscribed letter, perhaps a U (fig. 2.1); it is unclear whether it was carved in antiquity or in more recent times. The proper left panel shows no trace of an inscription.

Below the tabulae hangs a garland of rounded fruits (perhaps pomegranates), flowers, and pinecones, suspended from the two front corners by swans perched atop balusters, which crane their necks upward as they grasp the ends of the garland in their beaks (fig. 2.2). The garland is suspended in the center from a bucranium, a motif depicting an ox skull that alludes to the sacrifice of oxen during religious rites (fig. 2.3).

The small spaces between the garland swags provide additional space for figural motifs. In the lunette-like space between each tabula and garland swag is a hare eating from a cylindrical basket (perhaps a situla) of spilled fruit (fig. 2.4). This theme of an animal eating is echoed in the lower left and right spandrels, where a bird seems to be poking for insects or ripe fruit in the garland (fig. 2.5). Finally, a crouching sphinx with wings raised at attention fills the triangular space just below the bucranium (fig. 2.6).

The short sides of the urn preserve more cursory decoration in the form of simple palmette motifs carved in low relief and framed within a rectangular molding (fig. 2.7). Above each of these motifs is a circular cavity that corresponds roughly in size and placement to a cavity on either side of the lid. They likely accommodated the metal cramps used to seal the urn shut. The back and underside of the urn are roughly worked, which suggests that they were not meant to be seen.

The interior of the urn, also roughly worked, is carved into two equally sized, cube-shaped receptacles, divided by an interior wall, intended for the remains of two individuals (fig. 2.8). Around the top of the urn is an inner, raised lip, which corresponds to a channel carved into the underside of the lid, as seen at the broken back corner of the lid on the proper left side of the urn (fig. 2.9).

The front of the lid is similarly rich with imagery. With its double pediment and acroterion-like mask motifs on the left and right corners (fig. 2.10), the front resembles the roof of a temple or house. However, unlike many urns of a similar shape that incorporate a gabled form throughout the entirety of the lid (see fig. 2.11), the remainder of this lid takes the form of a flat, horizontal slab. Between the two pediments is a rosette formed by six heart-shaped petals enclosed in a circle, evoking the foliage of the garland and palmettes on the urn below (fig. 2.12).

Within the two pediments are what appear to be simplified portraits of a male and a female. Representations of the deceased (or possibly also those of the living) appear less frequently on cinerary urns, but they are attested. It is possible that these portraits depict (or at least suggest the appearance of) the deceased. The male head is surrounded by a wreath (perhaps of oak or laurel) supported by winged putti, whose rounded bodies fill the lower edges of the pediment (fig. 2.13); the female portrait is framed by a shell supported by two inward-facing dolphins, whose tails extend into the upper space of the pediment (fig. 2.14). While the female portrait could be described as a bust since it continues to the beginning of her left shoulder, the male portrait contains only a hint of a neck just below the chin. It is possible that the urn was intended to hold the remains of a married couple, who need not have passed away at the same time.

Although the busts are cursorily worked, their hairstyles suggest those associated with the Flavian period and the Trajanic period (A.D. 98–117). The pile of curls—indicated by small drill holes—is reminiscent of the so-called toupet coiffure worn in the Flavian era (see fig. 2.15), although it has been suggested that the style also continued to be worn in the following decades. The man’s forward-combed locks evoke a slightly later hairstyle, worn by Emperor Trajan (see fig. 2.16). Such features suggest a date in the late first to early second century A.D.

In the modern era, dealers and restorers frequently combined mismatched lids and urns in an effort to create a “complete” urn. However, it seems likely the lid and urn of the Art Institute’s Cinerary Urn were made as a pair. First, the motifs on both pieces exhibit general similarities in the quality of the carving: they are roughly carved and in fairly low relief, almost giving the impression of being unfinished. Second, the lid and urn bear a comparable width and depth, in addition to the raised lip on the top of the urn and the channel on the underside of the lid that allow the two pieces to fit together. Finally, both the urn and the lid were made of Carrara marble. While they were created from different parent blocks, this discrepancy could be attributed to the economical use of different pieces of marble in the workshop. Carrara marble was widely used by craftsmen in Rome during the imperial period and has been associated with a number of urns produced in Roman metropolitan workshops; perhaps the Art Institute’s urn was created in or around the capital.

Tomb Contexts and Commemoration

In the imperial period, the ashes of the deceased were typically placed in some form of a tomb structure, which by law (for public health concerns and fear of defilement) was required to be outside of the city gates. This symbolic act of inhumation appears to have been necessary in order to view the funerary rites as complete and fully effective, allowing the soul to pass into the next world.

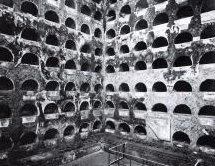

Cinerary urns were commonly placed either in a familial tomb, which housed the remains of a nuclear family or of an extended household (i.e., the patron’s freedpersons and their descendants), or in a columbarium, a type of tomb structure that was characterized by its dovecote-like interior configuration, which included rows of niches placed from floor to ceiling that were intended to hold cinerary urns (see fig. 2.17). Columbaria could accommodate much larger and more diverse groups of individuals who were not necessarily related through kinship but who were connected in other ways. While marble urns are attested in both types of tombs, their popularity is especially linked to the development of the columbarium tomb in the first century A.D.

Columbaria appear to have been largely distinct to Rome and its port cities of Ostia and Puteoli, which were characterized by similarly diverse, upwardly mobile populations. They were primarily created for and used by a predominantly nonelite population, as suggested by funerary inscriptions indicating individuals who varied in age, profession, and legal and familial status. Numerous columbaria were built and administered by collegia (organizations or interest groups with a professional, religious, domestic, or social focus), as well as by private burial clubs, which were created solely for the purpose of providing an individual (perhaps one with no descendants) with a decent burial and the necessary funerary rites. The largest columbaria were built (or at least provided for) by imperial or aristocratic houses in order to offer the members of their extended households, many of whom were slaves or freedpersons, the opportunity for burial and perpetual inclusion within a privileged community.

Familial tombs and columbaria were not static spaces, as the family of the deceased would return frequently on important dates such as the individual’s birthday, anniversary of death, and other festivals associated with the cult of the dead. At such gatherings, the family might hold feasts at the tomb, present flowers and food as offerings to the dead, and light lamps, where the urns would be on view. In the larger columbaria, it was likely that multiple birthdays, death anniversaries, and the like would fall on any given day; the tombs would be especially crowded during commemorative festivals, increasing the likelihood that one’s urn would be seen by a large number of relatives and nonrelatives. The marble urn was then also a clear sign of the family’s wealth and status, which reflected on the surviving family members.

Interpretation of Motifs

The corpus of Roman marble cinerary urns displays a common repertoire of decorative motifs derived from diverse sources. The meaning of each of these motifs to their contemporary Roman audience (which undoubtedly varied depending on the context and the viewer) is by no means clear to us today, given the lack of general ancient literary sources describing not only basic beliefs about the afterlife but also Roman funerary practices. Nevertheless, this uncertainty has not prevented modern scholars from attempting to interpret the motifs in an effort to better understand what they might have signified to the ancient viewer.

Numerous scholars have suggested that the motifs might symbolize beliefs about or hopes for the afterlife, with particular motifs alluding to such concepts as the deceased’s apotheosis or victory over death, the journey of the soul to the Isles of the Blessed, or the practice of banqueting in the afterlife. Others have argued that the motifs instead served a retrospective, commemorative function, looking back on the individual’s life and accomplishments. Additionally, the association of some motifs with the paraphernalia of funerary rites and religious offerings could allude to the sacred nature of the tomb.

The origin of a number of the motifs in the political iconography of Augustan art and architecture has also been noted. According to Paul Zanker, the ubiquity of the motifs that adorned public monuments in Rome, such as the garland, the bucranium, and the corona civica, led to their internalization by patrons and artists alike. This “subliminal absorption” also caused some of these motifs to lose much of their original political significance, and in turn they were incorporated largely as decorative motifs into the art and furnishings of the domestic and funerary spheres.

Over the past several decades, there has been greater emphasis on the multivalency of the motifs. Since most were employed in both sacred and secular contexts, it is possible that they were not understood to carry a distinctly funerary meaning when viewed on their own. Rather, they might only have been imbued with a specifically funerary message when combined with other motifs and placed in a tomb context.

Reading the Art Institute’s Cinerary Urn

While it is not possible to know how an ancient viewer would have understood the Art Institute’s Cinerary Urn, it is nevertheless important to consider the variety of meanings that its numerous motifs might have conveyed. Two of the most prominent motifs, the garland and the bucranium, are most likely derived in part from the imagery of Augustan public monuments, such as the Ara Pacis Augustae. This altar, which is arguably the most significant public monument of the Augustan age, reflected not only the emperor’s vision for a revival of the state religion but also his social policies and dynastic ambitions. For example, images of religious paraphernalia, such as garlands, bucrania, and paterae are depicted on the inside of the walled precinct around the altar, where sacrifices such as that depicted on the altar itself would have occurred (fig. 2.18 and fig. 2.19). On cinerary urns, this combination of motifs might have carried religious overtones, perhaps alluding to the funerary rites carried out at the tomb for the dead.

Similarly, the motif of the garland, along with the motif of the rosette in the lid, might have functioned as permanent offerings to the deceased, suggesting the real garlands and flowers that were laid upon the grave following the Roman custom. Roses, in particular, which are one of the most frequently listed offerings in funerary inscriptions, might have suggested the idea of a never-ending spring season in the afterlife.

Additionally, the garland and rosette, along with the palmette motif on the short sides of the urn, might allude to the attractive and blissful setting of the tomb within a funerary garden. While small tomb plots might have included simple plantings such as evergreen shrubs, cypress trees, or flowers, the largest examples could include diverse fruits, vegetables, and flowers, which could even be sold to raise the income necessary for the maintenance of the tomb itself. More broadly, the rosette and lush garland could suggest the pleasures of nature in the afterlife.

The animal motifs on the front of the urn, namely the hare eating fruit from a basket and the bird nibbling at the garland, might similarly have alluded to the joys of nature, either on earth in the setting of the tomb garden or in the hereafter. They might also be read more simply as genre motifs or perhaps even as xenia. In the domestic setting, xenia are commonly thought to reflect the abundance of the household, so it is possible that such images would have conveyed similar ideas about the life of the deceased.

Other figural motifs, such as the swans and the sphinx, appear to be derived from the Augustan political sphere due to their connection to Apollo, Augustus’s patron deity. Additionally, the motif of the swan could reference the domain of Venus (the Roman goddess of love and sexuality as well as the mother of both the Roman people and the Julian line), as they are occasionally found accompanying her at her toilette. It is likely that these motifs were chosen not to advertise the saeculum aureum of the princeps but instead based on their new, decorative function.

Turning to the lid, in the pediment on the proper right the wreath surrounding the male portrait might have suggested the corona civica, which was commonly made of oak leaves. Although initially reserved for the emperor’s use, the motif of the oak wreath was later employed by freedmen of the imperial house to advertise their newly attained free status. In funerary art, the oak and laurel wreaths eventually became general symbols of achievement and past successes. Alternatively, the wreath could also suggest the wreathing of the dead, as the deceased was sometimes crowned with a wreath prior to the lying-in-state that occurred before burial.

Flanking the male portrait are winged putti, which could suggest the deceased’s soul and perhaps its ascent to the heavens above. However, it seems more likely that they alluded to the sphere of Venus, whose imagery is also apparent in the portrait of a woman in the pediment on the proper left. Here the female portrait is set within a shell that is supported by two dolphins, both symbols of Venus and her associations with water.

It is possible that such Venusian symbols were intended to suggest the deceased woman’s feminine virtues, such as beauty and fertility. A similar type of divine assimilation is found in contemporary theomorphic portraits that combine individualized portrait heads of Roman matrons with idealized, frequently nude body types associated with statues of Venus (see fig. 2.20). More broadly, the use of Venusian imagery in both portraits might suggest conjugal love and the possibility that this couple was married.

On the corners of the lid are theatrical masks, which, as noted above, resemble the acroteria that crown a building, perhaps in order to identify the urn as a literal house of or temple to the deceased. They might also suggest the individual’s participation in the “comedy of life.” Perhaps the masks even reflected a connection to the god Bacchus (the Roman equivalent of the Greek Dionysos), who was associated with rebirth, regeneration, and the transcendence of boundaries. More broadly, they might have alluded to the idea of an afterlife full of the joys associated with the god.

Workshops and Cinerary Urn Production

It seems reasonable to surmise that most individuals who purchased urns for their deceased did not commission custom designs. When faced with an unexpected passing in the family, a suitable urn had to be acquired in a timely manner to accommodate the remains of the deceased prior to burial. Given the formal and stylistic similarities that can be identified among different urns, it has been suggested that the majority were prefabricated by workshops, which might have employed their own distinct repertoires of images in particular arrangements.

None of the motifs on the Art Institute’s Cinerary Urn is entirely unique, and while the addition of portraits is less common, the urn nevertheless displays some notable formal and stylistic similarities to several other double urns that might have been created in the same workshop. The closest example, an urn inscribed to Iulia Prisca that is now in the collection of the Museo Nazionale Romano in Rome (fig. 2.21), bears a striking resemblance to the Chicago urn in choice and distribution of motifs, although it appears to have been carved by a more skilled sculptor.

Both urns are adorned on the front with two tabulae, along with a lush garland of fruit and flowers hanging in two swags, below which are placed two small garden birds in the lower outer spandrels. While the Chicago urn includes a bucranium at its center, the urn from Rome bears the head of a goat. In the lunettes created in the space below the tabulae, each urn includes at least one hare eating from a spilled basket of fruit. While the Chicago urn incorporates a crouching sphinx with raised wings below the bucranium, on the urn of Iulia Prisca this triangular area is filled instead with two crouching birds with their backs turned to one another and their tail feathers pointed upward. At the front corners of both urns are swans standing upon balusters, with their necks craned to support the edges of the garlands.

The lids also bear some notable similarities, particularly in the representation of the portraits. The lid of the urn of Iulia Prisca also includes a male and female portrait in each of the pediments, which are similarly framed in a wreath and a shell, respectively, although their placement is opposite that on the Chicago urn. Additionally, these portraits were clearly intended to be busts, as traces of the figures’ shoulders are evident in both cases (fig. 2.22).

On both urns, the figures’ faces are fairly rounded (with those on the Chicago urn tapering slightly at the chin), and they exhibit almost identical, somewhat generic facial features (see fig. 2.13 and fig. 2.14). However, the female figure in the urn of Iulia Prisca also includes what appears to be a wart near her right eye, which could suggest that the sculptor was attempting to incorporate at least one identifying feature. The hairstyles of the figures on the urn of Iulia Prisca also resemble those on the Chicago urn, with the male figure similarly wearing a Trajanic style of locks combed over the forehead and the female figure wearing the toupet coiffure. In fact, the hairstyles are more legible on the urn of Iulia Prisca, which assists in its dating to the late first or early second century A.D., the same date that is assigned to the Chicago urn.

The formal and stylistic similarities between these two urns suggest that they might have been created in the same workshop, which was likely in Rome, given the discovery of the urn of Iulia Prisca in the Vigna Codini columbaria, located near the Via Appia. While the more skilled carving of the urn of Iulia Prisca suggests that it might have been carved by a different sculptor, the repeated use of the same motifs and their placement in the same general locations suggests that a comparable approach was taken with the design of both urns. Moreover, the addition of portraits to each could indicate that they were created as private commissions, though one must question the extent to which these small, generalized images were understood as distinct representations of individuals. The notably similar appearance of the portraits on each urn could suggest that they were prefabricated, with the necessary identification being provided by the epitaphs added to the tabulae.

Conclusion

While the identities of the individuals whose remains were contained within the Art Institute’s Cinerary Urn are a mystery, it seems likely that they might have been of moderate wealth and status, given the presumably higher cost of a double urn made of Carrara marble than that of a simple terra-cotta olla or glass urn. Moreover, the deliberate selection of an urn adorned with figural motifs and miniature portraits suggests additional care on the part of the surviving family members, whether to emphasize claims of elevated social status or to create a more individualized funerary monument within a communal burial context. Given the association of familial tombs and columbaria with freedpersons and slaves, it is possible that the individuals whose remains it contained were either currently or formerly of imperial servile status, although they might instead have been freeborn nonelites. Although it is not possible to say whether the numerous motifs that adorn the urn were intended to convey specific messages, they likely offered some suggestion of the sacred nature of the tomb setting while providing an attractive and respectable burial.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This lidded urn was fashioned with two cavities to accommodate two separate sets of cremated remains (fig. 2.23). Both lid and body were carved from single blocks of fine-grained, white marble that have been identified as Carrara. Examination of the lid and the body reveals that, although the same variety of marble was used, the two components were not carved from the same parent block. The lid was affixed to the body by means of a cramp, probably made of lead. The marble bears a broad range of toolmarks, and evidence suggests that the tabulae have been recut. No traces of polychromy or gilding have been detected. During its time in the museum’s collection, the object has received only minor surface cleaning.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is a warm white, almost ivory, with an overall reddish, ocher tone. Veins and bands of gray are present throughout. On the proper right side of the urn body, the marble has a very dense, desiccated appearance, more like limestone than marble.

Lid

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); K-mica, X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4 (present); quartz, SiO2 (present)

Body

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (abundant); K-mica, X2Y4–6Z8O20(OH,F)4 (traces); quartz, SiO2 (traces)

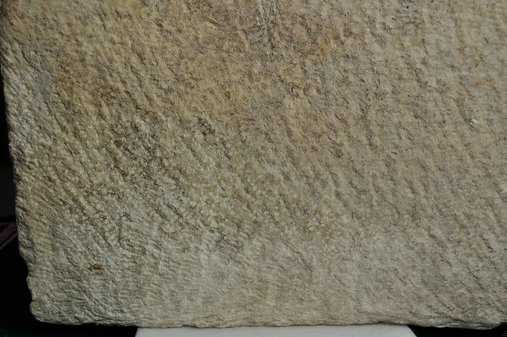

Petrographic Description

Two samples were taken. The first sample, 1.9 cm high by 4.8 cm wide, was removed from the lid, profiting from an area of incipient cleavage on the edge of the proper left side, approximately 13 cm from the front edge, adjacent to a large area of loss. The second sample, 1.8 cm high by 2.9 cm wide, was removed from an area of loss on the proper right side of the inner dividing wall of the urn. The samples were then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of each sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of each sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Lid

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 1.84 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic, almost polygonal with triple points

Calcite boundaries: straight-curved

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some intercrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 2.24

Body

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.48 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic, almost polygonal with triple points

Calcite boundaries: straight-curved

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some inter- and intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 2.25

Because the maximum grain sizes and types of decohesion seen in the two samples are different, it can be deduced that the sculptor used two different blocks of Carrara marble.

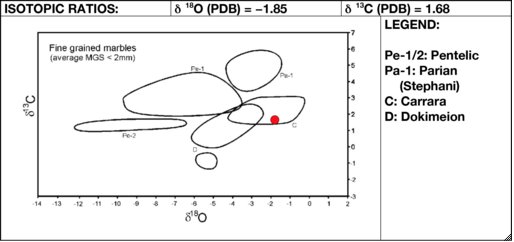

Provenance

Marble type: Carrara (marmor lunense)

Quarry site: Carrara region, Apuan Alps, Italy

The determination of the marble as Carrara was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram for lid: fig. 2.26

Isotopic ratio diagram for body: fig. 2.27

Fabrication

Method

Each of the two parts of the object was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.

On both the proper left and proper right sides, circular cavities were hollowed out of both the lid and the body of the urn. These holes vertically align with one another and were created to accommodate a cramp or fastener of some kind (fig. 2.28). On the proper right side, the hole in the body contains traces of a dark-gray material, possibly remnants of lead.

There is a conspicuous circular hole on the front of the urn body in the bottom proper right corner, the purpose of which is uncertain (fig. 2.29). There is no corresponding hole in the opposite corner.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Toolmarks can be found in abundance across the surface of the object. Much of the carving is quite rough, but it is unclear whether this is because the urn is partially unfinished or because it is the product of a less-experienced hand.

The remains of first-stage carving are visible on the interior of the urn, where the sculptor cleared away the stone diagonally from the top proper left to the bottom proper right using a point chisel (fig. 2.30).

Traces of first-stage carving also remain on the top of the lid and on the back of the body. Marks left by a claw chisel indicate that the sculptor applied the tool in a lateral direction across the top of the lid on the proper right side. This pattern devolves into random, circular motions through the center and toward the proper left side. Along the high points of this surface, abrasion has preferentially worn away the toolmarks. On the back of the urn, a claw chisel was used to clear the stone in a roughly semicircular direction; the resulting marks appear to run predominantly clockwise (fig. 2.31). A small section in the bottom proper left corner shows evidence of a more horizontal stroke, while in the top proper right corner, the marks appear more vertical.

A scraper was used to level off the top surface of the inner, raised lip of the urn body; those traces remain prominent, likely due to their relatively sheltered location under the lid (fig. 2.32).

To create the rich three-dimensionality of the vegetal and animal forms below the tabulae, the sculptor began by using a drill to pierce the stone at intervals, creating deep tunnels in accordance with the shapes he wished to render. This network of pierced holes was then excavated using either a roundel or the drill itself. Although the stone has been cleared away, the drill holes of the original perforations remain visible along many of the lines (see fig. 2.33).

The presence of a small, drilled hole at the base of the baluster on the proper left side, which seems not to correspond to any of the design elements, is an interesting curiosity, perhaps betraying the sculptor’s carelessness in drilling the initial outlining holes (fig. 2.34).

Drills of varying diameters were also used to create details in the garland and the bucranium on the urn body (fig. 2.35) and in the rosette on the lid (fig. 2.36).

For much of the rest of the carving, a flat chisel was the sculptor’s tool of choice. Marks made by the broad edge of this tool can be seen in the modeling of the hares (see fig. 2.37). The chisel was held at an angle to carve the tiered frames surrounding the tabulae, the recessed areas in the pediments on the lid, incised details in the garland, the diagonal lines on the balusters at either end of the urn, the undulating lines on the top and bottom edges of the urn, and the palmette motifs on the proper left and proper right sides, among other details.

The tabulae appear to have been altered or cut back at some point. Marks left by a flat chisel within the tabulae offer tangible proof that these surfaces were coarsely taken down, perhaps to remove the original inscription. The marks are particularly noticeable in the proper right tabula, where rough, unfinished vertical grooves can be seen within the frame. A vestige of smooth stone indicating the level of the original surface remains visible against the upper edge of the frame near the center (fig. 2.38). Furthermore, the framed edges do not seem to follow a consistent or logical pattern. The top edge of each frame, for example, comprises three tiers, while the sides show either one or two, and the bottom tier is very ill defined. Interestingly, in the proper right tabula, a deep gouge very strongly resembles the initial carving of a letter, possibly a U. The mark is incomplete, and next to it is a deep scratch (fig. 2.39). Whether this was the beginning of a new inscription is unknown.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

Superficial abrasions are present throughout on both the lid and the body. White calcareous accretions are visible overall, particularly along the bottom edges and within deep recesses and undercuts (see fig. 2.40). Chips, losses, and lacunae of varying degrees are apparent on all corners and edges of both the body and the lid. The presence of root marks provides desirable evidence of antiquity.

Of the four holes that were drilled to accommodate cramps, that on the proper right side of the lid has a noticeable loss to its top edge; that on the proper right side of the body shows a large crack extending from above the hole approximately 3.6 cm downward into and beyond the hole, and also across the entire top surface of the interior edge of the body; that on the proper left side of the lid has largely broken away in association with the primary loss to the back corner, but the bottom end of the cavity remains visible; and that on the proper left side of the body shows some spalling and a short crack around its perimeter.

The surface of the marble is heavily stained with both ocher-colored and brown discolorations. Dark, red-brown accretions can be seen throughout in areas of high relief. The staining is particularly prominent on the proper left side of the body and on the back of the body on the proper right side. Staining on the proper right side of the body shows clear, hard edges and may have resulted when irregular burial deposits that sheltered the underlying marble were removed, exposing the white surface underneath (fig. 2.41).

When the object is viewed under ultraviolet radiation, the lid appears more amber colored than the body (fig. 2.42). This suggests the possibility that the surface patina of the lid is intact to a greater degree than that of the body. The body of the urn, particularly the proper right side, has been heavily abraded, a fact that is especially noticeable when the object is seen under UV radiation and that may account for its more violet appearance.

The urn itself is unlevel, with the proper right side being higher than the left by approximately 2 cm.

Lid

The lid is quite clean compared to the body. The back proper left corner is missing, and two pins made of iron are present in association with this loss, indicating the existence of a previous repair that is now lost (fig. 2.43). White cementing material is visible around the perimeter of each pin. The appreciable corrosion of the iron suggests that these repairs may be ancient. There is a notable loss to the top of the pediment on the proper right side. The mask on the proper right corner is missing the top of its head, and there is a moderate spall on the mask on the proper left corner. Along the proper left side, the majority of the bottom edge is missing.

Body

On the proper left side of the urn, several pits and small holes are visible across the surface. The proper right side of the urn is heavily marked with deep and conspicuous scratches.

Several cracks are present. One extends approximately 1.6 cm down from the top edge into the proper right tabula. A second extends approximately 5 cm down from the top edge between the swan and the edge of the proper left tabula, in association with a large chip.

The interior surface of the urn is heavily stained, and the inner lip of the proper right top edge bears a heavy, resinous coating, perhaps from a material originally used to seal the lid to the body (fig. 2.44). A large, triangular fragment is missing from the back portion of the central dividing wall inside the body of the urn. A prominent, reddish-brown stain is visible on the front surface of the proper right compartment (fig. 2.45).

Conservation History

In 2011, the object was treated in preparation for its reinstallation in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art, in an effort to improve its overall appearance. The exterior surface was cleaned using bristle brushes along with a vacuum and a HEPA filter. A large quantity of loose particulate matter inside the urn, including soil, dust, and fibers, was collected and placed in zip-closure polyethylene bags. The object was then further cleaned by the application of high-pressure steam. Where steam was insufficient to remove more-prominent staining, various solvents and poultices were applied, with limited success.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini