During the Roman imperial period, children were widely represented in the art of both the public and private spheres. Images of both mortal and divine children appeared in the artworks and furnishings of the home, on the tomb monuments and burial containers associated with the funerary realm, and on imperial state art.

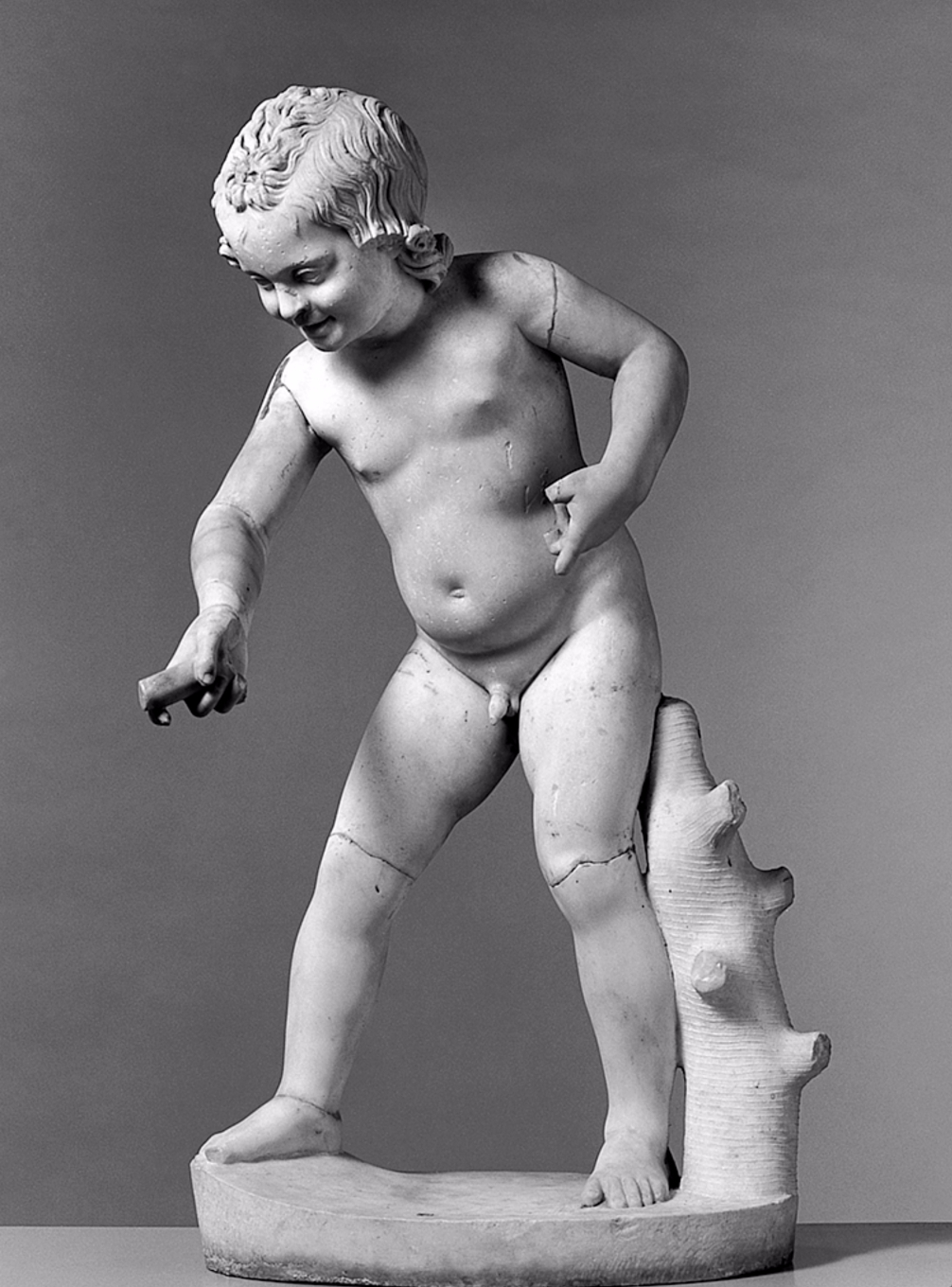

This statue of a nude young boy, which is made of Parian marble, exemplifies the Roman interest in the subject of children. The figure is largely intact and preserves the head and the majority of the body, although it is missing both arms from the upper arm downward and both legs just below the knees. He is shown in a contrapposto stance, with his left hip raised and his right leg extended slightly forward. This shift in movement is echoed in the tilt of the boy’s head downward and to his right, suggesting that he has fixed his gaze on something in this direction.

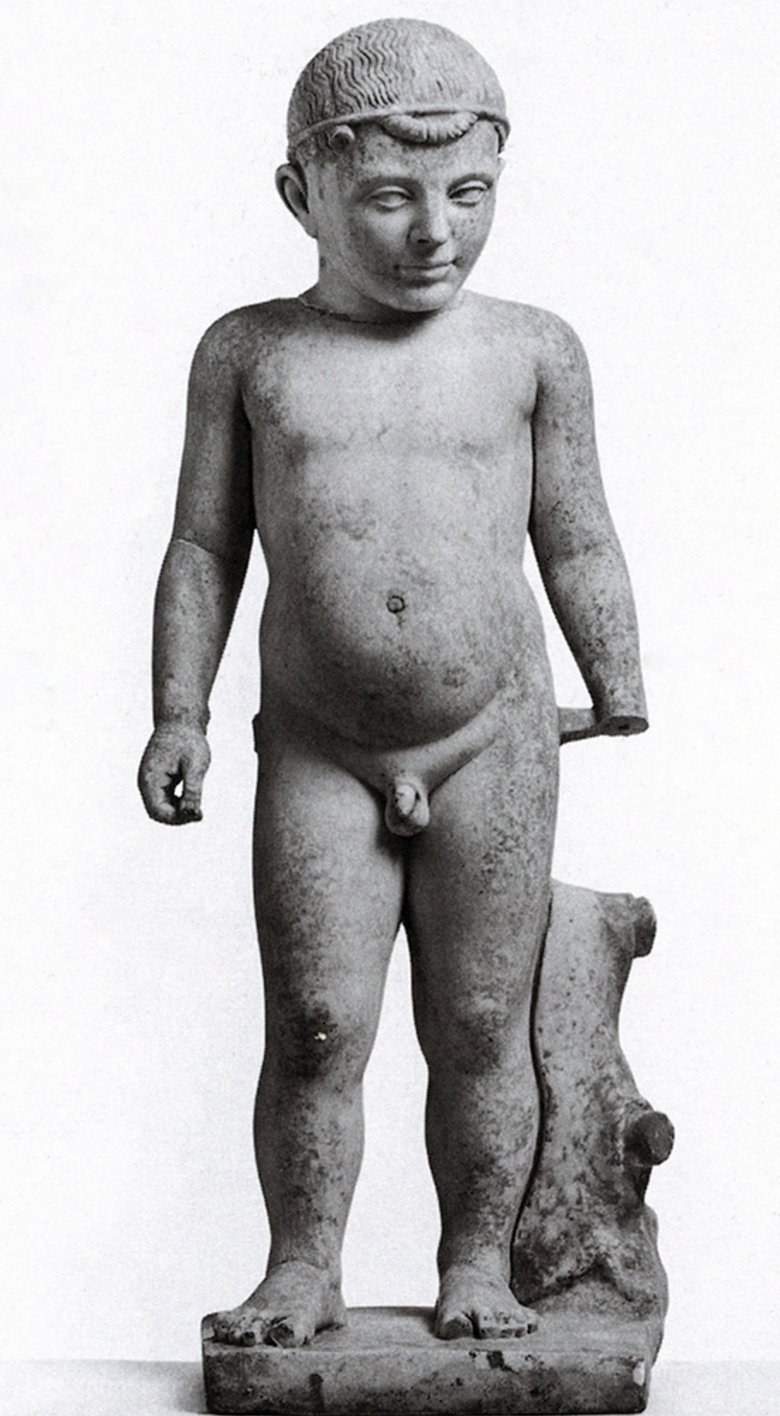

The surface of the statue on the front is marred partially by staining from the local burial context, but this does not detract from its aesthetic appeal. On the back, abrasions are located in several places, including the proper left shoulder blade, the proper right upper arm, both buttocks, and the proper left thigh (fig. 1.1). While it is possible that these abrasions could indicate lost features, it seems more likely that they reflect damage that occurred to the surface of the sculpture at a later date. On the outside of the proper right leg is a hole that extends deep into the figure’s thigh (fig. 1.2). A protrusion of marble at the edge of the hole is probably the remains of a strut or bridge used in antiquity to attach the figure to a support, not unlike the tree-trunk support in a statue of a boy in Copenhagen (fig. 1.3), or perhaps to another figure in a sculptural group.

The figure’s body reflects an interest in the naturalistic representation of the child’s anatomy. At first glance, the narrow torso and slim arms, along with the rounded belly and chubby thighs, seem to suggest an older infant (fig. 1.4). However, the height of the figure, which is nearly two feet tall even without its lower legs, suggests a young child. Additionally, the chest and upper abdomen exhibit subtle muscular definition, giving the boy an oddly athletic appearance despite the pudginess of his lower body. This strength is reinforced in the figure’s back, where the slightly muscular form around the shoulder blades seems to contradict the fleshy buttocks and thighs.

The hair is composed of thick, short locks, with some in tight curls and others in S-shaped waves (fig. 1.5), suggesting a natural hairstyle as opposed to a styled coiffure, as one frequently finds in portraits of Roman children (see fig. 1.6). The facial features, including the small chin, pudgy cheeks, and full, pursed lips, reinforce the childlike appearance (fig. 1.7) and, along with his sharp, almond-shaped eyes, are notably similar to those in other statues of young boys, particularly another example in Copenhagen (fig. 1.8). However, the crisp appearance of the eyes may be the result of recarving that occurred after a later phase of cleaning to remove surface incrustation. Based on the figure’s size and overall childlike features, it is likely that the boy is intended to be a toddler around the age of two or three.

While no traces of pigment are apparent on the statue’s surface, it seems likely that it might have been enlivened through the addition of polychromy to the hair and eyes to create a more lifelike appearance. Consequently, the figure might have more closely resembled the images of children in Roman wall paintings (see fig. 1.9).

Due to a lack of distinct physiognomic details, it seems likely that the Statue of a Young Boy was not a portrait but instead functioned primarily as a decorative image of an anonymous, presumably mortal child, who was likely engaged in some form of play.

Children as Genre Subjects in the Hellenistic World

In the Hellenistic period, artists took a new interest in a wide variety of subjects associated with daily life, many of which were previously unrepresented in the classical Greek world. Known as genre subjects, their ranks included representations of members of the lower class, such as fishermen, peasants, actors, and teachers as well as athletes, including boxers and wrestlers. Atypical body types were also frequently represented—dwarfs, hunchbacks, and grotesques—and extremes of age also took precedence, as suggested by depictions of the elderly and of children from infancy to adolescence. Lesser divinities and minor mythological figures were also popular, including satyrs, centaurs, Erotes, and hermaphrodites. Animals, too, gained significant attention and were often represented alongside human and divine subjects. The prominence of these genre subjects not only suggests Hellenistic artists’ reaction against the lofty, idealized images of gods and heroes that characterized the classical period, but also reflects the intermingling of Greek and non-Hellenic artistic traditions in the culturally diverse cities of the Hellenistic kingdoms.

The subject of children was especially popular in the art of the Hellenistic period, yet its origins lie in the art of the classical period, when children began to take on a clear pictorial identity on Attic red-figure vases, funerary monuments, and votive offerings. While their appearance on vases reflects the broad appeal of the representation of childhood and adolescence, the creation of votive offerings and costly stone monuments suggests the deep feelings held by adults for children as well as the need to commemorate them as individuals in their own right. For example, on a gravestone in the Princeton University Art Museum (fig. 1.10), a young boy named Mnesikles is shown in the nude holding the pole of his toy roller, suggesting that his family wished to commemorate him as a playful child.

Unlike classical Greek representations of children, those of the Hellenistic age treated the child’s body primarily as an aesthetic object and reflected an even greater interest in depicting children’s anatomy and behaviors. While many such images depict seemingly mortal children at play with animals, toys, and other children, they can also represent divine or heroic figures in a youthful form. For example, a bronze sleeping Eros in the Metropolitan Museum of Art accurately reflects the appearance of a chubby toddler (fig. 1.11). It is commonly assumed that these sculptures were decorative domestic works, but they might also have served funerary or religious functions, for in the Hellenistic period children continued to be represented on funerary monuments, such as grave naiskoi. Sculptures of children have also been found in religious contexts, for example in the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron, where statuettes of boys and girls likely served as votive offerings.

Genre Images of Children in Roman Art

The subject of children retained its appeal in the art of the Roman period. As the Romans began to conquer the cities of Greece and Asia Minor from the second century B.C. onward, they developed a taste for the artworks and artistic styles of classical and Hellenistic Greece. Roman patrons not only collected Greek artworks but also purchased or commissioned entirely new works that were inspired by them to varying degrees. Artworks depicting Hellenistic genre subjects, particularly children, were no exception. It is thought that some genre sculptures of children produced in the Roman period were intended to evoke specific Hellenistic prototypes noted in the literary sources, such as the type depicting a young boy strangling a goose (see fig. 1.12), which is thought to be based on an earlier bronze statuette created by Boethos of Chalcedon. Many other examples are likely to be new Roman works created in the Hellenistic style.

Examples showing children’s interaction with animals are particularly numerous and suggest the broad popularity of pet keeping. Often they depict moments of tenderness between a child and an animal, such as this statue of a boy cuddling a puppy (fig. 1.13). Some convey a more violent or aggressive tone, for example the boy strangling a goose (see fig. 1.14) or a boy pulling on a rabbit’s or hare’s ear. Children are also shown playing with toys, such as balls, knucklebones (astragaloi), or nuts (see fig. 1.14). In other examples, children are shown with fruits or a vessel, or perhaps even bearing a combination of attributes.

Many Roman genre sculptures of children appear to have been created predominantly for domestic display, as a number of statuettes of children have been found in Roman houses, particularly in gardens. However, examples are also attested in public buildings, such as bath complexes. Some genre sculptures of children could also serve a functional purpose that enhanced their overall decorative effect. For example, numerous statuettes depicting children functioned as fountains. In these statues, the stream of water from the fountain shoots either from an accompanying animal’s mouth or a vessel such as a wineskin or jug, as can be seen in a statue of a small boy holding a water jug on his shoulder in Copenhagen (fig. 1.15). Other statuettes served as table supports, perhaps offering a playful suggestion of the presence of children underfoot in the Roman household.

Representations of children also appear on Roman funerary monuments, such as funerary altars, cinerary urns, and sarcophagi. They are especially apparent on monuments dedicated to deceased children, on which the child is frequently represented in a portrait with a pet, toy, or other attribute. The lack of physiognomic distinctions in many of these “portraits” could suggest that some monuments were precarved stock pieces, although the individual’s identity might be indicated through the addition of an inscription. Regardless of the accuracy of the likeness, the selection of a funerary monument for a deceased child indicated the value that the family placed on commemorating the child’s life.

In some cases, the images of children on Roman funerary monuments appear to draw on earlier Hellenistic iconography. For example, on a sarcophagus of Trajanic date (A.D. 98–117) in Rome, the deceased boy is shown playing with a goose (fig. 1.16). Here, however, he appears to be engaging with the animal in a friendlier and less aggressive manner than represented in the (presumed) Hellenistic sculptural type discussed above.

On sarcophagi, the extended form of the decorative field frequently allowed for a more narrative representation of the subject matter of children. For example, numerous children might be shown at play, perhaps in an effort to suggest an episode of the deceased child’s life. However, in such scenes the children are often rendered in a more generic and seemingly artificial way, much like the statues of children that adorned the domestic sphere. For example, on a sarcophagus in Vienna, two groups of nearly identical boys are shown at play, each with the characteristic round face and pudgy limbs associated with freestanding sculptures of children.

It is also possible that freestanding genre sculptures of children might have served as commemorative statues in tombs. Statues of the sleeping Cupid, who closely resembles a human child in an infantile state, have been identified in funerary contexts. These have been read as idealizing, nostalgic images of deceased children.

Finally, it is important to consider the possibility that some genre statues might have served as dedications in sanctuary settings. As noted above, genre subjects depicting children were known to have served a votive function in the Hellenistic period. Moreover, Roman statues of the sleeping Cupid are also attested as dedications in the imperial period. Statues of mortal children might similarly have been dedicated as sculpted offerings by parents or relatives on behalf of their children.

Interpreting Roman Genre Images of Children

The intended meanings conveyed by Roman genre images of children are not known for certain, but they have been interpreted in a variety of ways. Above all, they have been read by modern scholars on a superficial level as whimsical, playful images that were intended to capture not only the lighthearted nature of childhood but also the qualities often associated with children, including innocence, gentleness, and childish directness. This viewpoint finds some support in the ancient literary sources, which attest to the idealized and nostalgic adult view of the period of childhood as a time characterized by leisurely play and sport.

Literary sources also shed light on the visual enjoyment of actual children, particularly slave children. For example, according to Philo of Alexandria, Romans enjoyed having attractive children serve water to their guests at banquets, an observation that is echoed in Petronius’s Satyricon in description of the wealthy freedman Trimalchio’s lavish dinner party, at which handsome Alexandrian boys poured snow-cooled water on the guests’ hands. Such slave children might be referred to as deliciae, a term popularly used to refer to pets but that also broadly referred to any person or thing that gave the viewer delight or enjoyment. While some slave children described as deliciae might have been cherished by their owners, others might have been subject to sexual exploitation in the form of pederastic relationships with their male and female owners. Thus, it is possible that statues of anonymous children suggested not the domain of carefree childhood but instead that of slave children whose appearance was intended to please the viewer.

Sculptures of children might also have offered witty, urbane commentaries on well-known myths and artworks. For example, the sculptural type of the boy strangling a goose discussed above (see fig. 1.12) might have parodied the tale of the Greek hero Herakles (for Romans, Hercules) strangling serpents as an infant, albeit in a more domesticated manner. This episode in the hero’s early life is exemplified by the statue of a young boy (possibly portraying the emperor Caracalla) in the guise of the hero (fig. 1.17).

In a similar manner, a sculptural group of a boy and a swan formerly in the collection of Ince Blundell Hall in England depicts a young boy standing next to a large swan, which extends its right wing around the boy’s back, almost as if to embrace him. In this way, the sculptural group appears to allude to the story of Jupiter and Ganymede, in which the supreme god transforms himself into an eagle in order to steal the beautiful youth away to Mount Olympus to make him the cup bearer of the gods. In its suggestion of an erotic relationship between an older male and an attractive youth, the tale also alluded to the practice of pederasty.

The Statue of a Young Boy also seems to evoke the sculptural type known as the Weary Herakles. This type, which is often thought to have been developed by the fourth-century B.C. Greek sculptor Lysippos, depicts the hero in a moment of repose after completing the last of his Twelve Labors, the retrieval of the golden apples guarded by the nymphs known as the Hesperides (see fig. 1.18). With his downcast head, relaxed contrapposto stance, and extended right upper arm, the Statue of a Young Boy appears to echo the image of the hero in repose (fig. 1.19).

Consequently, it is possible that the frequent nudity depicted in Roman genre statues of young boys offered a lighthearted evocation of the nudity that was associated not only with representations of gods and heroes but also with the exalted genre of the heroically nude male portrait. In the case of the latter, the nude, muscular male body (typically in combination with armor and weapons) suggested that the subject possessed the same physical prowess, bravery, and vigor of the Greek mythical heroes who had long been represented wearing the costume of nudity. The Statue of a Young Boy, with his similarly nude body, subtle hints of athletic musculature, and contrapposto stance, could have been viewed as an image of a young boy wearing the heroic costume.

Images of young boys and girls might also have conveyed deeper messages about the socialization and moral education of Roman children. The representation of children’s interaction with animals, particularly when showing friendly encounters with pets, could suggest the variety of educational, emotional, and social benefits that arose from pet keeping. Such benefits might include the development of personal responsibility and mastery over animals, the ability to give and receive affection, and a child’s first experiences with the life events of birth and death.

Similarly, the images of children behaving aggressively with animals could allude to the Roman child’s introduction to the various forms of bloodshed associated with adulthood. Indeed, the sacrifice of animals was an integral part of religious practice, while the violence of gladiatorial combat, wild beast hunts (venationes), and other public games (ludi) were equally present in Roman life. In particular, cockfighting appears to have been a popular activity among children, who raised cocks for fighting in a practice that was intended to introduce them to victory through death as well as the violence and pain that they would witness later in life.

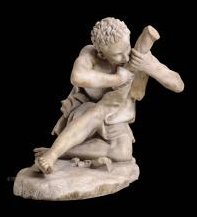

Additionally, children’s encounters with their peers through games and recreational activities were viewed as critical in the development of their social skills and moral maturity. The opportunity for children to interact without adult supervision, whether through friendly play, childish quibbling, or physical competitions, encouraged them to develop qualities associated with adult society. For example, on a funerary altar in the Musei Vaticani in Rome one finds a scene showing two boys after a cockfight, one the celebratory victor and the other the defeated, who walks away with his rooster under his arm as he wipes the tears from his face in sadness (fig. 1.20). Such a scene could signify the Roman emphasis on success in competition as a social virtue, the importance of risk taking, and life’s unpredictability. Other images reflect the subversive behaviors of children lacking proper socialization. For example, in a sculpture in the British Museum known colloquially as the Cannibal, a boy is shown violently biting into the armof a now-missing companion with whom he was playing knucklebones (fig. 1.21).

Ultimately, whatever the intended meanings might have been of the different types of images of children, one issue is clear: these images were constructed by adults and therefore offer a view of children and their behaviors that is ultimately based on an adult perspective.

Cupid: The Eternal Child

Images of mortal children, especially young boys, are often noted for their striking similarities in appearance to Cupid, the Roman god of love. To be sure, images of other mythological figures are also attested in a youthful form, which are often identifiable based on their iconography. For example, young satyrs are frequently recognized by the addition of features such as pointed ears and tails. Puerile images of gods and heroes are also attested, particularly among subjects whose mythological backgrounds incorporate episodes focusing on their infancy and childhood. For example, a bronze statue of a nude male infant in St. Louis has been identified as a possible representation of either a child god or hero, perhaps Dionysos or Herakles (fig. 1.22). Among divine and mythological figures, Cupid appeared in the form of a child the most frequently, making the parallels between representations of mortal children and those of the god the most visually compelling.

During the Hellenistic period, the representation of Eros, Cupid’s Greek counterpart, underwent a notable change. This god, who had previously been depicted as a slender, nude male youth (see fig. 1.23) was reenvisioned as a chubby, mischievous toddler (see fig. 1.11). This shift in Cupid’s form seems to run parallel to the increasing interest in the representation of children as subject matter in Hellenistic art. This notably youthful image of Eros carried over into that of Cupid in the Roman period, not only in representations of the god himself but also in mythological or genre scenes depicting multiple “cupids,” or putti.

The figures of Cupid and putti are most frequently identified in artworks by the presence of their wings, although attributes such as the bow and torch might also be present in images of the god himself. They frequently sport long locks of hair, which are at times arranged above the forehead in a small bun or topknot, a style which is also worn by mortal boys (see fig. 1.24). This hairstyle’s association with Cupid appears to be the reason for identifying some depictions of young boys as possible representations of the god, even in the absence of wings.

However, putti can also be shown wingless, depending on the practicalities of representation and the context. Indeed, winged and wingless putti are at times depicted together, even when the format does not appear to have restricted the artist’s ability to include wings. For example, on one of a pair of silver skyphoi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an image of a wingless putto or child riding a female panther next to a winged putto playing a kithara (fig. 1.25). It has been suggested that such wingless images depict putti in a more humanized and less divine form, particularly when they are shown in everyday activities associated with mortals.

The comparison between mortal boys and putti extends beyond similarities in physical appearance to that of their behaviors. In various media but particularly in Campanian wall paintings and on Roman sarcophagi, putti are often shown engaging in various human activities, including those associated with the world of childhood. They not only participate in children’s games, such as hide-and-seek and the hoop race, but they also watch cockfights and engage in athletic competitions. The comparison is made explicit in the relief decoration on the lid of a sarcophagus in the Musei Vaticani, on which one finds a rare depiction of groups of putti and boys playing together, albeit in separate groups rather than in a combined scene. Here the putti are shown on the left bowling hoops, while the mortal boys on the right play a greater variety of games, including nuts, leapfrog, a game with ropes and sticks, and an activity involving sliding balls down a sloped plane.

The physical and behavioral similarities between mortal children and putti undoubtedly encouraged viewers to make cross-connections between the subjects. However, unlike mortal children, who would eventually grow to adulthood, the god Cupid as well as putti existed perpetually in a state of childlike appearance and behavior. In this way, they might have conveyed similar ideas of a sentimentalized, idealized childhood, one that such “eternal children” would never outgrow.

This blurring of boundaries between human and divine children appears to have encouraged the representation of mortal boys in the guise of Cupid. Such theomorphic portraits are found frequently in funerary contexts and appear to be a parallel trend to the use of images of the sleeping Cupid as funerary monuments for deceased children. For the purposes of a funerary monument, the image of either Cupid or a boy in the guise of the god might have offered a compelling form of commemoration for the relatives of a deceased child, as it elevated the child out of the mortal sphere and into the realm of fantasy and the divine, where he would remain eternally in his youthful form.

While the Art Institute’s Statue of a Young Boy does not wear the long locks or topknot hairstyle characteristic of Cupid and putti, he closely resembles a figure identified as Cupid that accompanies the statue known as the Fould Satyr in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (fig. 1.26). This Cupid, whose wings are no longer preserved, stands in a strikingly similar pose, with his right leg forward and his arms and head turned downward. The attribute in his left hand, which was restored as a pedum, appears to have originally been a downturned torch, a symbol of Cupid also seen on the pair of skyphoi discussed above (see fig. 1.25). To be sure, the Statue of a Young Boy does not preserve any traces of features on his back that suggest the former presence of wings (fig. 1.27), yet the possibility cannot be entirely eliminated that he might have been a wingless Cupid or putto, whose identity was indicated based on the presence of a now-missing attribute.

Children in Roman Society

The interest in children in Roman art goes beyond that of purely aesthetic or sentimental appeal. In the imperial period, children were frequently depicted on public monuments for their ability to convey a variety of social and political connotations. This was due in part to their increased prominence in private law and in imperial policy, which took greater account of children and their well-being than ever before.

Beginning with Emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14), the child’s body was portrayed in Roman art for the first time as a political object, which could represent various dynastic, patriotic, and religious ideas. This new prominence of children in the public sphere was due to the fact that they played a central role in the moral reforms known as the Leges Iuliae. These reforms, which were enacted by Augustus in 18 B.C. following the devastation of Rome’s population after almost a century of civil war, were part of Augustus’s larger program to improve Roman society. More specifically, they were aimed at penalizing the adulterous and the celibate while rewarding married couples who produced and reared children, who were viewed as the state’s hope for the future. They were followed a year later by the Secular Games, which focused on health and fertility.

Consequently, images of boys and girls were employed soon after in coinage and public art to suggest the happiness and fecundity of the regime and the blessings of children. These ideas are exemplified in the Ara Pacis Augustae, on which mortal and mythological children are shown in numerous reliefs. Among the children (not all of whom can be conclusively identified) are Augustus’s two adopted sons (and actual grandsons) Gaius and Lucius, whose presence suggested the emperor’s hope for dynastic succession and the continuation of his line (see fig. 1.28).

The emphasis on children initiated by Augustus was extended by a number of his successors, most notably Emperor Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), who fully developed the alimenta scheme, through which the interest on loans provided to farmers on their land provided support for children in local areas. The scheme, which was represented on Trajan’s Arch at Beneventum, did not simply provide a handout but rather connected the growth and development of children and the landscape with that of the empire. In this way, children were viewed not just as blessings but also as investments in the future of the empire. Similar initiatives regarding children’s welfare were put forth under Emperor Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–38) and the Antonines (r. A.D. 138–93) and were highlighted in contemporary imperial monuments.

It has been suggested that the new legal and emotional valuation of children and the increasing depiction of them in the public sphere led to their acculturation throughout Roman society, with the result that mortal and divine children began to appear more often in domestic and funerary art than ever before. While some genre subjects representing children might have been created for decorative purposes, particularly for display within the home, it is possible that the generalized political message of children as the empire’s hope for the future might also have been suggested on some level. For example, images of wingless, childlike putti that appear in early imperial domestic art and furnishings are thought to signify the blessings of children in Augustus’s Golden Age.

This public depiction of children is also thought to have contributed to their popularity in the funerary sphere. Since children were not typically honored publicly in life with portraits, they were commemorated instead after death in monuments such as group reliefs, altars, cinerary urns, and sarcophagi. Freedpersons were often patrons of such monuments for their deceased children, who, as freeborn citizens, held a more honorable status than their parents. For parents who bore the stain of servitude and also suffered the loss of a freeborn child, the erection of a funerary monument with a child at play not only allowed them to call attention to their family’s arrival in free Roman society, but it also might have consoled the surviving relatives over the loss of a child who might have been expected to carry on the bloodline and the family’s social achievements.

Conclusion

Statue of a Young Boy likely functioned as a delightful, primarily decorative image of a small child for a Roman home, as this was the most common use and context for such genre figures of children. Alternatively, it is possible that it was displayed in a public setting, such as a bath complex, where it might have served a similar purpose. Finally—though less likely—it could have been either part of a funerary monument in a tomb context or a religious dedication in a sanctuary. However, statues known to have served such functions frequently depict Cupid rather than seemingly mortal children.

The sculpture does not appear to hearken back formally to any specific Hellenistic genre type and thus could be a distinctly Roman creation based on such styles. Its fragmentary state does not reveal the boy’s activity, but he was likely shown with a toy or another attribute, or perhaps with an animal or another figure. Through his characteristically childlike proportions, fleshy body, and puerile nudity, the figure might have conveyed a nostalgic, idealized image of the innocence and vulnerability of the life stage of childhood. This distinctly childish appearance might also have evoked the imagery of Cupid as well as putti, who, as eternal children, were characterized by their comparable appearances and behaviors. Since Statue of a Young Boy is lacking any evidence of wings, the possibility cannot be ruled out that he might have been a wingless putto, although this seems less likely due to the absence of any other attributes that support such an identification. Consequently, his interpretation as a mortal boy remains the most plausible.

Finally, given the strong emphasis on children in Roman private law and imperial policy, it is also possible that this image of a nude young boy might have suggested to viewers either specific or more generalized messages that were rooted in imperial iconography, such as the idea of the blessings of children as well as the critical role that children were expected to play in the growth and development of the empire. However he was ultimately understood by the Roman viewer, his naturalistic, youthful form bespeaks an awareness, and perhaps also an appreciation, of the distinctive appearance of children.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This object depicts a life-size, nude, young boy standing, his eyes gazing downward (fig. 1.29). The figure is fragmentary, having sustained losses to all its appendages; the remains of a point of attachment are visible on the proper right leg. The object was carved in the round from a single block of medium-grained, off-white marble that has been identified as Parian and that bears the gray veining characteristic of that stone. Traces of late-stage carving tools are visible on the surface. The sculptor employed struts and bridges, one of which remains on the genitals. No indication of polychromy or gilding has been detected. The sculpture was once heavily encrusted with rootlets embedded in a white matrix, and, despite extensive remediation, much of this evidence of antiquity remains, particularly about the head and face. The stone itself is in sound condition and is marked by prominent discolorations that are a result of the burial environment. The onetime use of plaster restorations is suggested by the presence of an opaque material on all break edges as well as a fill to a loss on the proper left hip. During its time in the museum’s collection, the object has received one campaign of surface cleaning.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble has an ivory tone overall, with crystals clearly visible within the matrix. Gray, horizontal banding runs from the base of the proper left hip up to the rib cage in the back. Another gray band begins on the rib cage under the proper left arm and branches into two discrete veins, one running across the pectoral toward the neck on the proper left side, and the other extending across the chest to the proper right shoulder. A third gray band can be seen near the dimple of the proper right buttock.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (very abundant)

Petrographic Description

A sample 0.8 cm high by 1.3 cm wide was removed from a small projection of stone on the inside bottom edge of the proper right thigh. The sample was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of 30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.

Grain size: medium to coarse (average MGS greater than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 1.58 mm

Fabric: heteroblastic mosaic, slightly strained

Calcite boundaries: curved-embayed

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed slight inter- and intracrystalline decohesion.

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 1.30

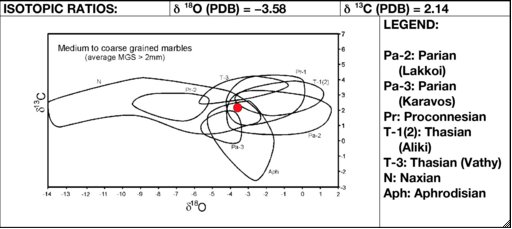

Provenance

Marble type: Parian (marmor parium)

Quarry site: Lakkoi, Korodaki valley, on the island of Paros, Cyclades, Greece

The determination of the marble as Parian was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 1.31

Fabrication

Method

The object was sculptured from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers. The statue was carved and fully finished in the round. Early stages of carving were completely removed from all areas that would have been visible in antiquity.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

A flat chisel was used to delineate the folds of the neck and the creases extending from the corners of the mouth down to the chin (fig. 1.32). The same tool was employed in the groin area to create the folds of skin at the top of the thighs, between the legs and the genitalia (fig. 1.33), and along the underside of the protruding belly. On the proper left side of the line following the curve of the belly, the sculptor flared out the terminus of the line, creating a square. This was probably achieved by angling the tool upward and outward while applying a percussive blow. In addition, the sculptor used the edge of a flat chisel to sharply demarcate the penis from the scrotum and to emphasize the umbilicus. With the exception of the philtrum, which was created with a roundel (fig. 1.34), the facial features were also rendered with a flat chisel. The appearance of the eyes, in comparison with other facial features, strongly suggests that they were recarved after excavation. The head and face were once heavily encrusted with rootlets, and, after mitigating these rootlets by mechanical means, the restorer likely would have found it necessary to ameliorate associated damage to the face by sharpening up the contours of the eyes (fig. 1.35 and fig. 1.36).

The same recarved appearance is evident on the top of the head, where the burial incrustations were once quite significant. When these growths were mechanically removed, it seems that some rendering of detail was lost in this area (fig. 1.37). The curls in the front were then resharpened with a flat chisel, while those on the back of the head did not require the same degree of intervention (fig. 1.38). As a result of this work, much of the three-dimensionality and roundness of the locks of hair was lost, rendering them flatter and more angular (fig. 1.39).

A running drill was used to create the line between the buttocks, as evidenced by the circular depression at its end point (fig. 1.40).

Drills of varying dimensions, ranging from 4.2 to 6.88 mm, were employed in rendering the curls of the hair (fig. 1.41 and fig. 1.42).

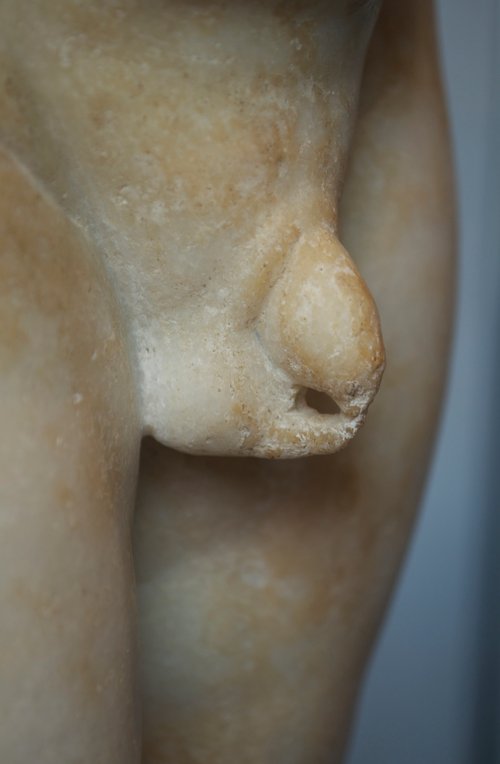

The sculptor left the penis connected to the scrotum by means of a curving, conical bridge (fig. 1.43).

There is a large hole in the outside of the proper right leg. It is 2 cm wide and extends diagonally upward for approximately 7 cm. A protuberance of marble on the outside edge is most likely the remains of a bridge or strut that once served to attach the object to another sculptural element (fig. 1.44). The hole was drilled into this projecting feature, suggesting that the figure might have broken away from this point of attachment. It is likely that the hole was used either to reattach the object to its original sculpture by means of a dowel or rod or to join it to a completely different work in a campaign of reuse. In either scenario, root marks and earthen debris in the interior of the hole confirm that it existed prior to burial.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.

Condition Summary

The sculpture has lost all of its appendages. The proper left arm is missing from just above the biceps, the proper right arm from midway between the shoulder and the elbow. There are minor associated chips and losses to the outside edges of the breaks. Neither arm has been drilled, but both break edges reveal traces of an opaque, blue-gray material that is most likely plaster, suggesting that the object may once have borne restored arms.

Both legs are missing from just below the knee, but both kneecaps remain extant. A significant associated loss is visible on the inside of the proper right leg. The same opaque, blue-gray material found on the arms is also present on the break edges of the legs, and heavy abrasions are apparent around the lowest part of both legs—in particular around the proper right knee—where the stone may have been filed down to accommodate plaster restorations.

The undersides of both legs have been drilled. The cavity in the proper left leg holds the existing metal rod that serves to affix the sculpture to the pedestal. The drill hole in the proper right leg has been filled with a cement-like material with a slightly yellow tone. Because of these interventions, it is not possible to examine the interior of the holes, but, given the scale of the figure, it is unlikely that the holes were used in antiquity to affix appendages. It is more likely that they were created to accommodate restorations. A large blister of bright-orange oxidation and a halo of dark-orange staining are visible at the perimeter of the cement-like material on the proper left leg; the presence of these stains lends weight to the theory that a plaster restoration was secured to the object by means of an iron rod or dowel. Minus the restorations, these holes would have been employed to secure the object in an upright position for display, as is now the case.

Large spalls are visible on the high points of the buttocks, on the back of the proper left thigh, and on the proper left scapula. A deep gouge extends along the outside edge of the back of the proper right arm. The exposed crystalline structure within these spalls and gouges is heavily weathered and contains embedded dirt or soiling of a claylike nature. These surface anomalies are highly suggestive of excavation-related damage.

The sculpture is marked by a pronounced patina. Deep ocher patches scattered across the front of the object are most noticeable on the upper portion of the chest and in a dramatic circle around the umbilicus (fig. 1.45). These discolorations are the result of contact with substances such as phosphates dissolved in the groundwater during burial. These areas show pitting to a degree not seen on the whiter areas of the sculpture, and the pits contain white and dark debris that gives the surface a mottled appearance. The pitting indicates that these stained sections were once thicker, more substantial concretions that were ground down by polishing.

Vivid red-orange staining is present on the back at the inner edge of the proper right thigh (fig. 1.46). This red coloration stops approximately 10 mm above the break edge, leaving a bright white ring around the bottom edge. A similar stain appears at the bottom edge of the proper left leg, adjacent to a spall and around the rod.

The object was once heavily engulfed by organic growth, and these rootlets—desirable evidence of antiquity—remain most visible in the locks of hair, where the concretions must at one time have been extremely robust (fig. 1.47). Rootlets are also in evidence where the upper thighs are pressed together; where the earlobes attach to the side of the head; along the lines between the arms and the torso; at the back of the ears, particularly on the proper left side; and in the crevice of the buttocks. The rootlets have a reddish-brown tone, indicative of an iron-rich burial environment, and are embedded in a white matrix, most likely redeposited calcium.

The surface of the marble displays a matte, dry quality overall. When the sculpture is examined under ultraviolet radiation, it appears an almost uniform violet color (fig. 1.48), suggesting that the stone was at one point subject to a comprehensive abrasive treatment or repolishing. The torso and the front of the thighs have a more burnished appearance than the rest of the object, and the areas of ocher coloration appear especially polished. The different microstructure conferred on these areas by the burial environment may have rendered them more durable and resilient and thus more capable of taking a polish.

The surface of the object is pockmarked and scratched throughout. A significant proportion of the pockmarks result from the action of rootlets penetrating the stone matrix. A notable horizontal scratch is present on the outside of the proper left hip, level with the bottom of the buttocks, and another scratch extends diagonally outward from the break edge on the back of the proper left arm. There is a small loss to the bottom of the proper right earlobe. The surface of this loss shows scattered root marks, so the loss existed prior to burial.

A large calcification is present on the back of the proper right shoulder (fig. 1.49). It is unclear why this accretion was not removed during mechanical cleaning. It may have been deliberately left in place as evidence of burial in advance of sale.

A small repair, approximately 4 cm in diameter, executed in a coarse plaster or a fine cement-like material, has been applied to a shallow loss at the top of the proper left hip. The repair is visually discordant with the surrounding stone in both tone and opacity.

Conservation History

In 2004, the object was brought to conservation with the goal of ameliorating an overall grimy appearance. Cleaning trials were carried out using aqueous cleaning methods and various synthetic and paper-pulp poultices. While each of these potential treatment methods proved successful, each also presented certain drawbacks which precluded its use. A further test was performed using a buffered aqueous solution and a nonionic surfactant applied with a soft brush. This method cleaned the surface deposits without leaving the marble looking desiccated. The whole sculpture was cleaned in this way and then rinsed again with the buffered aqueous solution. This cleaning protocol had no impact on the red staining on the interior of the thighs. Archaeological deposits of earthen material embedded in high-relief areas were left intact.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini