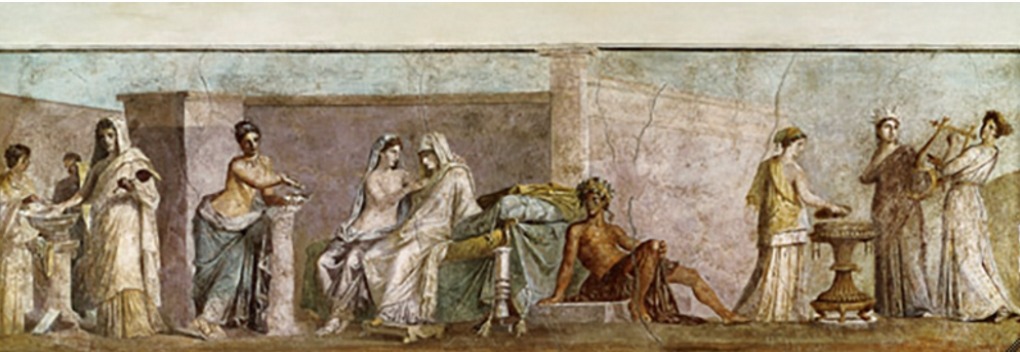

Two women kneel on either side of a three-sided lamp support (candelabrum) or incense burner (thymiaterion) that serves as a small altar. Together they lift a shallow bowl containing three triangles; the center form is a twisted flame, the other two represent offerings. With their lowered hands they twine ribbons around the altar. The large spirals around the base resemble floral scrolls, a popular symbol of abundance and fertility. The scene was modeled in low relief on a large terra-cotta plaque. The upper border is egg-and-dart molding; the lower border is scalloped, with alternating, downward-pointing lotus buds and blossoms.

At the time the relief was made, during the early years of the Roman Empire, the women would have looked both exotic and old-fashioned. Curly hair is combed to form a knot on the back of the head (see fig. 4.22, left, for a better-preserved example with dark red pigment on the hair). Each wears a long, thin garment that clings to breasts, arms, and legs; it is bloused at the waist like a classical Greek [glossary:peplos], but the long sleeves recall fashions in the Greek cities of both southern Italy and Asia Minor. The women’s bare feet and kneeling pose are unusual, even un-Roman; it has been suggested that the pose reflects the Egyptian custom of kneeling before the gods. Roman citizens, both men and women, who served as priests or conducted religious rites are always shown formally dressed and standing (see fig. 4.23); these two women may represent cult attendants, shown as hazy memories of a bygone age.

The three-legged stand is similarly old-fashioned; it resembles centuries-older Etruscan and Greek stands for lamps or incense burners that were revived as both cult and domestic furniture in the context of Augustus’s religious reforms (see fig. 4.35).

Terra-Cotta Architectural Relief Plaques

Brightly painted architectural ornaments made of terra-cotta (fired clay) had a long history in central and southern Italy, stretching back to the seventh century B.C. A new and different kind of architectural relief plaque began to be popular about the middle of the first century B.C., becoming larger and more skillfully made during the reign of Augustus. The plaques were modeled in relief, as multiples with the help of molds, to be mounted side by side to form friezes of identical or thematically related decoration. Like much ancient sculpture, the designs were enhanced with pigment. The style and subjects of many plaques reflect the same taste for neo-Attic classicism as contemporary wall painting, sculpture, Arretine pottery, and carved gems.

The first Roman emperor, Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14), famously boasted: “I found Rome built of bricks; I leave her clothed in marble.” He revived antique religious ceremonies, restored old temples, and ordered new civic structures built according to traditional designs and ornamented with art that imitated masterworks of the past. These commissions bolstered the program of moral reforms he instituted to counter the real and perceived luxury of his fellow patricians (including his own great-uncle and adopted father, Julius Caesar), which he believed had undermined traditional Roman values. What Augustus created became a new social system based on veneration of the ruler (himself and his family), splendid urban temples, and a program of festivals that created a new tradition of myth and power.

To buttress Augustus’s political aims, the art forms of both ancient Etruria and ancient Athens—and the inexpensive, old-fashioned medium of terra-cotta—were revived for a series of important buildings. Clay evoked thoughts of the painted terra-cotta sculptures that survived on the oldest and most venerated temples of Rome. One of Augustus’s most important commissions, his forum in the heart of Rome, included marble emulations of the caryatids carved about 415 B.C. to support the entablature of the Erechtheum on the Acropolis of Athens. For another important building, the temple of Apollo Palatinus erected next door to his residence on the Palatine hill, Augustus appropriated famous cult statues from Greek cities. Excavations close by the temple podium found terra-cotta wall plaques whose archaizing and Neo-Attic styles and subjects supported the emperor’s campaign to encourage traditional values (fig. 4.34). Many terra-cotta reliefs from other buildings, both imperial and private, show variations of the composition on the Chicago relief, with standing, seated, or kneeling women in archaic clothing or satyrs or erotes with exuberant acanthus scrollwork (see fig. 8.40).

Architectural terra-cotta relief friezes became popular as decoration in private villas—particularly in Latium, Etruria, and Campania, the areas within a few days’ travel of Rome. The pictorial motifs show great variety, including not only cult scenes but also stories of the gods and heroes; pastoral images of Bacchus, maenads, and satyrs; and representations of Roman life such as the circus, the theater, and allegories of victory. One of Cicero’s letters to his friend Atticus mentions, “further please get me some bas-reliefs [typos] which I can lay in the stucco of the small entrance hall,” perhaps referring to terra-cotta plaques. Examples have been excavated in private residences at Pompeii, Tusculum, Civita Lavinia, Cerveteri, Nemi, and Atri; a very few have been found outside Italy. The quality and quantity of reliefs reached a peak during the Augustan and Julio-Claudian period, and their use, size, and quality tapered off by the middle of the second century.

Technique and Style

The shallow relief sculptures are thought to have been cast in molds in order to produce series that could be affixed to walls to form friezes in temples, private houses, baths, and funerary structures. Continuing manufacture of new plaques by making new molds from existing reliefs led to two changes over time: a progressive shrinking in size, as well as softening and altering details due to touching up of the new master molds. A combined technique using both molds and some freehand modeling, particularly for the low-relief areas, is likely. First, an original relief was sculpted—or made as a copy or variation of an already existing plaque—and used to make the negative mold(s). Moist clay was pressed into the mold, allowed to dry, removed for refining, and then fired. The finished plaque would usually have been painted. Although pigment cannot be visually identified on the Art Institute relief, analysis could elucidate whether it bears any traces of pigment.

Identification of the Type

This plaque is the most complete surviving example of its type, but at least eight fragments of the same type have been identified. In addition to the kneeling women and the altar, two ornamental details characterize the type: the delicate egg-and-dart molding with eleven high-relief eggs in the upper border and the five complete and two half scallops that form the lower border. The alternating lotus buds and flowers in the scallops are unusual—palmettes are much more common—and it is important to note that they are simplified versions of the same motifs on the superb reliefs found near the temple of Apollo Palatinus (see fig. 4.34). No examples have been excavated or recorded from known findspots, so any wisps of meaning that could be gleaned from context—the type of building or the imagery of associated plaques—are unobtainable. A type of plaque that may be related—because it shares the rare lower scalloped border of interlaced lotuses—shows women wearing long-sleeved garments kneeling on either side of a huge apotropaic [glossary:gorgoneion] (see fig. 4.20); unusually, it is known that this plaque was found in Rome about 1875 during the digging of a sewer connecting the new Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II with the Via Merulana. We can imagine a frieze of these plaques side by side, perhaps alternating with related subjects, at the top of wall in the [glossary:peristyle] of a suburban villa like the one at Via Gabina, or in a lararium or a freestanding shrine.

Marchese Giampietro Campana and Collecting

This type of terra-cotta architectural relief plaque is named after the nineteenth-century art collector and archaeologist Giampietro Campana (1808–1880), Marchese di Cavelli. Beginning in 1831 Campana found hundreds of plaques as he excavated in and around Rome. Like most of the collectors and scholars who followed him, Campana was most intrigued by the types of plaques that illustrate myths, Roman life, or Nilotic landscapes. He eventually lined the walls of a room of one of his private museums with examples (fig. 4.28). In 1842 Campana presented his first scholarly catalogue to the Instituto di Correspondenza Archeologica, a two-volume monograph with 120 lithographs of this collection, thanks to which the term “Campana relief” became standard and these terra-cotta plaques began to be studied and appreciated.

Conclusion

Thousands of Campana reliefs can be seen in the galleries and storerooms of museums in Italy and other European countries, but the Art Institute’s plaque is one of only a score in American museums. Because the reliefs are made of humble fired clay and are often damaged, they are underappreciated as architectural sculptures or decorative images. However, they were popular for generations in many types of Roman buildings—baths, basilicas, theaters, temples, and forums, as well as private houses. What may be perceived as imagery that is old-fashioned, ornamental, and formulaic in fact had both political and religious symbolism, based on “an ethos that valued the lessons of tradition and exempla and the arts of emulation that paid homage to them.” The Art Institute’s architectural relief of women conducting a ritual is worthy of appreciation as an example of the revival of classical Greek art under the early Roman Empire.

Condition Notes

The plaque is fragmentary, consisting of three primary fragments and three smaller, associated fragments. These had been restored before the plaque entered the Art Institute’s collection. Six beveled holes are original—two in the upper border, two in front of the faces, and two above the ankles. They were drilled or punched through the clay before firing in order to accommodate fasteners to attach the plaque to a wall. The two bottom holes are shallow pits, not punched through to the back, perhaps the result of a previous restoration or the remains of compacted detritus from burial; perhaps incompletely perforated during original manufacture. The front surface was previously covered with a uniform layer of stucco; analysis has not been carried out to determine the presence of mineral pigments over the stucco. The back of the plaque is flat, with no definite traces of ancient mortar.

In 2000, in response to doubts expressed about the authenticity of the plaque, samples were sent to V. J. Bortolot, Daybreak/Archaeometric Laboratory Services, for thermoluminescence dating and were found to be consistent with having been last fired in ancient Roman times.

In 2012 the plaque underwent a major conservation treatment, including comprehensive surface consolidation; excavation and removal of unsightly and inappropriate [glossary:fill] materials; and a new campaign of fills, including modeling and restoration of missing surface features, more sympathetic to the surrounding ceramic fabric in texture and color.

Sandra E. Knudsen, with contributions by Rachel C. Sabino