These Roman architectural relief fragments, which are arranged in the form of two panels, were donated to the Art Institute in 1922. They belonged to the donor’s father and were reported to have come from the imperial palace called the Domus Aurea. Rich blue pigment provides the background for miniature, low-relief figures of white stucco, enhanced with touches of gold leaf. Both are heavily restored. In one panel a seated woman reclines in a chair with curved, tapered legs and offers a shallow bowl to a standing griffin. The figures probably formed part of the same composition—their feet touch—but part of the woman’s head and all of her left arm, as well as the tops of the griffin’s wings, are restored. The deer panel is composed of two main fragments—the right fragment includes the upper part of a stag and a winged woman pouring a libation from a jug into a shallow bowl, while the left fragment has a second stag that may not have been part of the original composition. The deer panel is framed by new stucco moldings, but on the griffin panel the upper right corner and most of the left side, including part of a foliate outer border, are original moldings.

The panels were created in or near the city of Rome in the early first century A.D. to decorate the wall or ceiling of a room. The room may have been opened sometime in the later nineteenth century, and the fragments of figures and frames were put together with the help of plaster restorations to look like small ornamental paintings, probably in order to be sold to an appreciative collector.

Visual Imagery

Without information about the findspot, interpretation of the two panels must be based on visual examination: considering the identity of the figures but also attempting to interpret the context. Based on the similar style, size, blue background, and ornamental framing, it is likely that the two panels come from one and the same location. The figures are easily identified within the repertoire of early imperial art of the reign of the first emperor, Augustus, and his successor, Tiberius: a winged woman between two deer and a seated woman with a griffin. The women have sometimes been tentatively identified as maenads, fitting within the ambiguous but sacred imagery of the entourage of the god Dionysos/Bacchus, but this seems unlikely because of the animals and the poses and attributes of the women.

Naked except for filmy drapery around her thighs, the languidly seated woman in cat. 157 is unusual for three reasons. She sits on a klismos, an elegant but old-fashioned Greek chair, signifying that she is a figure of the distant, probably mythological, past and that she is indoors—not reclining on the ground like a sleeping maenad or on a rocky throne like Ariadne, the bride of Dionysos. Her left hand rests improbably on a burning, downward-facing torch, symbolizing death—but this is due to the nineteenth-century restorer’s imagination; given her frontal torso, the original composition probably showed her left elbow resting on the chair back. With her right hand she extends a gilded bowl (patera) decorated with wispy ribbons toward a griffin, a mythological monster with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle.

Like sphinxes, Victories, and candelabra, griffins appear frequently in Augustan and Julio-Claudian art as symbols of the new golden age (saeculum aureum). Greek and Roman writers report that griffins both guarded and quarried gold far to the east, and that both gold and griffins are sacred to the Sun—Apollo was one of the gods most honored by Augustus. More generally, griffins are guardian figures and appear in public spaces like the Underground Basilica (fig. 157–158.1), as well as in tombs, including the columbarium of Lucius Arruntius (fig. 157–158.2), and private rooms, such as the bedrooms of the Villa Farnesina. They also appear on a small group of sarcophagi associated with children.

Although she could be mistaken for the goddess Nike/Victoria, the winged woman in cat. 158 is purely decorative because her immodest drapery and profile pose—as well as the fact that she does not hold an attribute such as an orb, laurel branch, helmet, or wreath—do not correspond to formal Augustan images of Victoria on coins, sculpture, or architecture. Clothed in a wisp of fluttering drapery, the woman poses in profile and pours a libation from a gilded pitcher into a gilded bowl, watched attentively by a stag. Her legs below the knees and the foliage scroll on which she perches are reconstructed imaginatively but likely based on other fragments known to the restorer. Traces of gilding on her wings, hair, and pitcher suggest the wealth of the patron and, perhaps, the sacredness of the imagery.

In ancient Greek and Roman art, when deer are not portrayed being mauled by hunting dogs, they most often appear with the goddess Artemis/Diana. The two stags in cat. 158, however, move without fear, as if they are pets. The antlers of the deer on the left are gilded. Their poses are reminiscent of the bronze deer excavated in the peristyle of the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum, where they served as pastoral decorations. Tame deer were kept as pets, for example the deer that came when called by a musician’s horn in the walled park of Quintus Hortensius near Laurentum, or Sylvia’s pet stag, who was shot by Aeneas’s son Ascanius, setting off the war between the Latins and the Trojans. A compliant deer also appears as a willing sacrifice to take the place of Iphigenia, as in the small frieze from the House of the Vettii, Pompeii (fig. 157–158.3).

It is significant that Apollo riding a griffin and Diana riding a stag appear together on one of the most important works of art that survives from the Augustan period: the cuirass of the Augustus of Prima Porta (fig. 157–158.4). The statue is now believed to be a copy of a portrait statue commissioned about 20 B.C., perhaps with some alterations to the cuirass ornaments in order to personalize it as a gift from Tiberius to his mother, Livia, Augustus’s widow. If commissioned after Augustus’s death in A.D. 14, the images of Apollo/griffin and Diana/stag provide a fixed date worth considering in relation to the Art Institute’s two panels.

Blue and White Cameo Sculpture

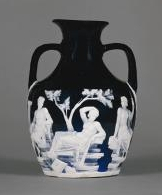

The combination of elegant white figures on a blue ground brings to mind blue and white cameo glass. Carved cameo glass vessels were some of the most luxurious, aristocratic objects of the early Roman Empire. Colored glass—most often blue—was cased with opaque white glass; the white layer was then partially cut away to reveal the colored background, and the white areas were carved in relief using the same tools and techniques as for hardstone gems. The most famous example is the Portland Vase (fig. 157–158.5). The simple arrangement of the figures on the Art Institute’s panels, as if they were cutouts set against a plain background, may be stylistically related to the “cool, calculated rationality” of artists during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, who for both public and private art “invariably tried to create the simplest and most lucid compositions and thus evoke a meditative mood. . . . Lack of narrative and an intellectualized symbolism lend classicistic imagery a remarkable ‘openness’ of interpretation.” For a large, early imperial cameo gem designed with this same symbol-laden clarity, see cat. 138, Cameo Portraying Emperor Claudius as Jupiter.

A few examples of white stucco architectural relief sculpture on a blue background suggest deliberate use of the striking color combination for important or sacred spaces. One of the earliest is the band of painted and stuccoed reliefs along the top of the wall painted with a garden in the underground dining room (triclinium) of the imperial villa of Livia at Prima Porta (fig. 157–158.6). Artistically more modest but eye-catching stucco reliefs of animals and of the centaur Chiron teaching Achilles to play the lyre decorate the pediment of an aedicula in the columbarium of Pomponius Hylas (fig. 157–158.7). The columbarium is named from a mosaic inscription of the later first century A.D., but it was built and this aedicula erected no later than the reign of Tiberius (A.D. 14–37). A space for family rituals is the lararium of the House of the Lararium of Achilles, Pompeii (fig. 157–158.8). The original vault of the small room, which opens off the atrium, did not survive the earthquake of A.D. 62. It was replaced between that date and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 with a stucco-decorated coffered ceiling and a cove molding with white stucco figures on a blue background illustrating scenes from the Trojan War.

Painted Rooms

In ancient Rome, the walls, floors, and ceilings of temples, public buildings, houses, and tombs were decorated. Grand public structures, such as palaces, temples, theaters, and basilicas, were often embellished with costly columns and panels of imported stone, glass, or gilded metal. Paintings—often inspired by famous masterpieces, probably via copybooks—were executed in fresco directly on the plaster surfaces that covered the walls of middle-class homes and of less important or less public buildings.

In ancient Roman architecture, the term stucco refers to two different materials and techniques. A lime-based plaster was applied to walls in several layers to yield a plain, hard, durable, slow-setting surface. A gypsum-based substance was used for sculpting and modeling architectural elements and details, often with the assistance of molds. The Art Institute’s fragments were probably part of the decoration of the upper part of a wall or a ceiling vault that used both techniques and possibly both materials, either singly or in combination.

Close examination of the surfaces and of the losses shows that the backgrounds of the Art Institute’s panels were painted blue before the stucco reliefs were added on top. The intensely blue paint of the background is probably Egyptian blue, sometimes called the first synthetic pigment. Originally imported and costly, availability increased and the price plummeted after the pigment began to be manufactured in Italy. A fresco wall fragment from the House of Augustus, Rome (fig. 157–158.9), is a useful example—Apollo reclines in much the same relaxed pose as the woman in cat. 157; the background is painted with blue pigment that has been analyzed as Egyptian blue; and gold leaf enhances the god’s hair as well as his quiver and lyre.

The stuccoist followed the painter immediately. He began by painting a ground line as guide. The figures and delicate details—billowing draperies, ribbons, horns, hair—were created using a brush loaded with thin stucco. The result is spontaneous and lively. Thicker stucco was then applied, pushed into position with tools and fingers, and finished with rapid cuts and incisions to produce the bold dark shadows of feathers, flowers, and contours.

The Four Pompeian Painting Styles and Stuccowork

Stucco ornament needs to be appreciated in tandem with painted decoration, because in addition to its use to create elaborate vault and ceiling moldings, it could be combined with painted imagery. Some decorators enhanced the illusion that painted walls “dissolved” the architecture by adding frames—painted or molded of stucco—around scenes as if they were panel paintings or windows, or by adding low-relief figures on top of painted drapery (see fig. 157–158.10).

Study of Roman painted wall decoration is based on two particulars: the styles of painting described by Vitruvius and the paintings that have survived, particularly those in the many buildings buried around the Bay of Naples by the volcanic eruption in A.D. 79, which preserved houses as much as two hundred years old as well as walls that were in the process of being painted and stuccoed at the moment of the catastrophe. Pompeii was a middle-class city, surrounded by the seaside villas of some patricians, so few paintings rise to the high level of quality of the paintings and stucco reliefs in the handful of imperial buildings that have survived in Rome and elsewhere. With some modifications, the four Pompeian painting styles classified by the nineteenth-century German scholar August Mau remain standard vocabulary.

The Pompeian First Style—Mau’s Incrustation Style—began about 200 B.C. and used paint and modeled stucco to imitate the costly slabs of stone used to line the walls of temples, public buildings, and the houses of the rich.

The Second Style—called the Architectural Style—began about 80 B.C. Painters still made imitations of colored stone panels, and stucco was used to model three-dimensional ceiling decorations that resembled the geometric coffer panels carved in stone or wood for monumental architecture. The coffers could include simple stucco ornaments like rosettes that imitated expensive decorations of carved stone or metal or even glass inserts. But the stucco architectural elements were secondary to the walls, where patron and painter collaborated to create a kind of picture gallery, with images of popular or famous panel paintings that could be visited in temple sanctuaries and other public spaces. Painters decorated other walls with the illusion of space on the other side of the wall, sometimes depicting architectural fantasies of nonexistent rooms, sometimes vistas of cities or countryside through false doors and windows.

Transition to the Third Style—Mau’s Ornate Style, sometimes called the Candelabra Style because of the frequent use of this semisacred motif—began about 20 B.C., around the time Augustus brought an end to civil war and nurtured peace and prosperity in Rome and Italy. Augustus encouraged cultural renewal—in architecture and painting as well as literature, drama, and sculpture—to support his political goal to create a future based on the best and most moral attainments of the Roman and Greek past. Artists and their patrons responded to this official art by adopting cool colors and strong compositions (see fig. 157–158.9)—inside which they escaped into images of other worlds, with minute, almost calligraphic depiction of scenes and ornament. Painters surrounded these elements with fantastic columns and pediments that could only exist in imaginary space. A serious military architect and engineer, Vitruvius scorned the extravagant visions of late Second and Third Style painting because the painters represented “things that do not exist nor can they exist nor have they ever existed . . . how can a reed really sustain a roof, or a candelabrum the decorations of a pediment, or an acanthus shoot, so soft and slender, loft a tiny statue perched upon it, or can flowers be produced from roots and shoots on the one hand and figures on the other?” Small vignettes—framed as if they were panel paintings—were placed in the center of walls; some such as bucolic landscapes featuring healthy livestock, shepherds, rustic shrines, and rocky hillsides.

Some stucco relief decoration from this transitional period, when craftsmen combined elements of the Second and Third Styles, about 20 to 10 B.C., could be dazzlingly pictorial, notably the fluidly “painted” stucco vignettes and landscapes from the patrician house discovered in 1879 under the grounds of the Villa Farnesina, Rome (see fig. 157–158.11). In the nineteenth century, the archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani admired these relief sculptures: “The artist might have modeled them by breathing over the stucco, they are so light and delicate.” Another, slightly later example is the frieze of panels with winged Victories perched on candelabra that framed the upper part of the wall painted with the famous garden fresco of the underground dining room in the villa of Livia at Prima Porta (see fig. 157–158.6). Rooms in both villas included low-relief stucco panels painted with blue grounds—a new experiment—the blue color suggesting the radiant blue sky and likely related to the development of a new and fashionable type of structure in the late first century B.C.: the subterranean grotto or nymphaeum designed as a transitional space between the rooms of the villa and its garden.

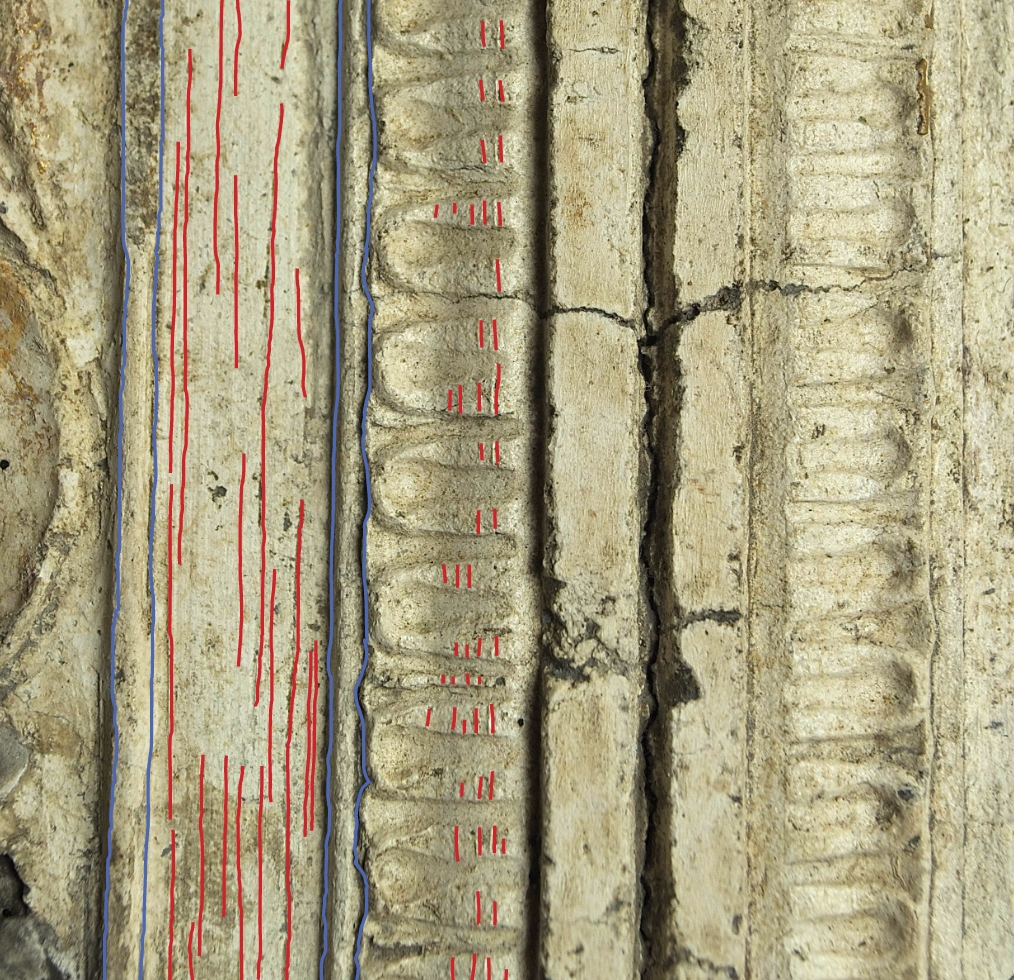

The ceiling of the Underground Basilica outside the Porta Maggiore (see fig. 157–158.1)—now recognized as a ritual space for neo-Pythagoreans that may have been suppressed by the emperor Claudius (r. A.D. 41–54) after less than a generation of use—is remarkably complete and recently benefited from a conservation campaign. Mariette de Vos recognized that its stucco decorations are similar in style and artistic quality to the Chicago panels, noting that the grid of stucco frames shares the same design. The Chicago frames have a flat line with a furrow on its axis, flanked by tongues; the Underground Basilica frames have eggs instead of tongues. The Chicago panels cannot have come from the Underground Basilica, because its decoration is intact—and because it was found only in 1917. There was, however, an extensive necropolis with rich tombs in this area, and the same stucco workshop could have worked on many of them.

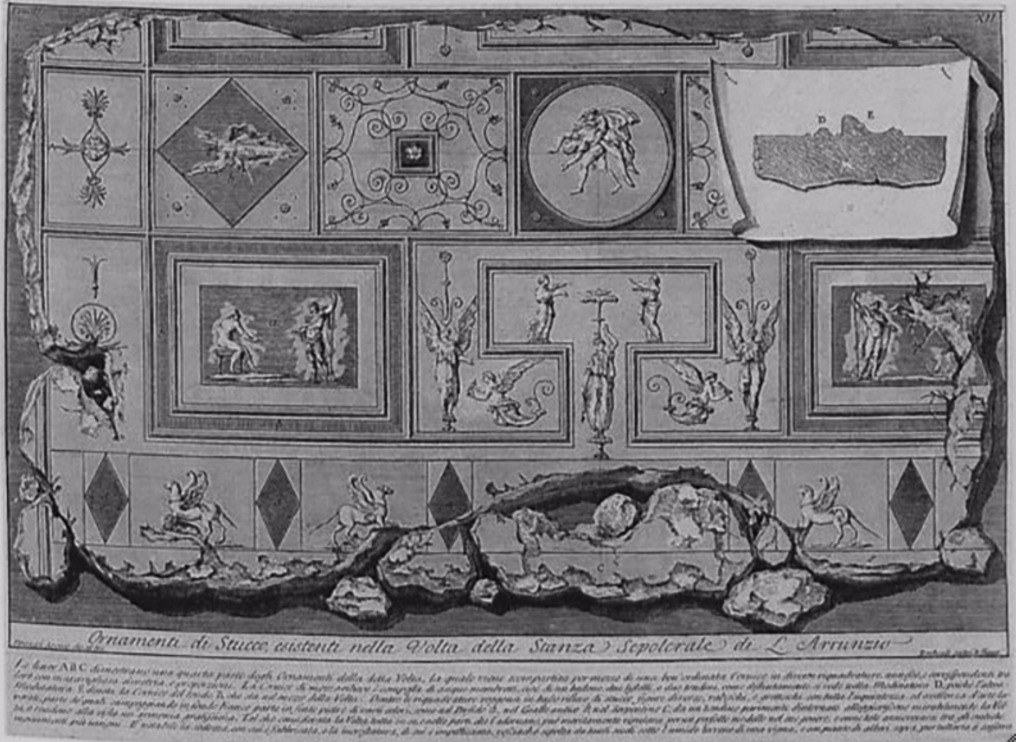

Similar stuccowork was used in the columbarium tomb built on the Esquiline hill, north of the Via Labicana, by Lucius Arruntius the Younger (before 27 B.C.–A.D. 36). Praised for his “blameless life,” Arruntius was Augustus’s coconsul in A.D. 6; after Augustus’s death in A.D. 14 he became an outspoken member of the Senate until forced to commit suicide under the political persecutions of Tiberius. A son and a grandson are also known, with careers that extended through the reign of Claudius; thus the columbarium continued in use for the freedmen and household of Lucius Arruntius until at least the middle of the century. The entrance and vault used painted grounds and frames in some of the panels, drawing attention to the delicate relief sculptures with what Roger Ling has called “characteristic Third Style restraint.” Stucco reliefs of winged women, seated figures, and griffins decorated the vaulted ceiling of the columbarium, which was destroyed at the turn of the twentieth century but had been recorded more than a century earlier in a series of engravings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (see fig. 157–158.2)..

The Fourth Pompeian Style—Mau’s Intricate Style—began about A.D. 20 and is the final style of interior decoration represented in the cities of Vesuvius. Its beginnings as the eclectic combination of elements from the earlier styles can be discerned as early as the 40s, during the reign of Claudius, and the style continued to be popular through the reign of Trajan (A.D. 98–117). Images of mythological stories and panoramic vistas combine with the architectural details of the Third Style. Some walls are painted in overall patterns as if a textile hanging (see fig. 157–158.10), and on others growing tendrils twine wildly. Ceiling designs combine paint and stucco in geometric patterns that combine rectangles and circles, straight and curved frames.

The alleged provenance of the Art Institute’s panels is the Domus Aurea. Augustus built the first imperial residence in Rome on the southwest corner of the Palatine hill in the 30s and 20s of the first century B.C. It was enlarged by his successors, adding spaces for receptions and ceremonies as well as offices and living quarters for the growing bureaucracy. The great-nephew of Augustus, Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (Nero) became emperor in A.D. 54 at the age of seventeen. He immediately built a new palace, but the Great Fire of Rome in A.D. 64 destroyed huge areas in the valleys between the Palatine, Oppian, and Caelian hills and gave him the opportunity to combine the imperial houses on those hills into a complex that he named the Domus Aurea (Golden House). Buried and overgrown, the Domus Aurea was lost and forgotten until the Renaissance, when its painted, stuccoed, and gilded decoration inspired Raphael and his contemporaries to design grottesche, named after the Fourth Style wall decorations of these buried grottoes. Recent close study by Paul Meyboom and Eric Moormann of the spaces and of the drawings, prints, and watercolors made since their discovery has demonstrated that the Domus Aurea was built and decorated in the four years between the Great Fire and Nero’s suicide in June A.D. 68. The grand public rooms were decorated primarily with colored stone revetments—in front of which the imperial collection of sculptures and panel paintings could be displayed. Painting, stucco ornament, and gilding were used on the high vaulted ceilings and in less important rooms. In the so-called Volta Dorata (gilded vault), in room 80 of the Domus Aurea, all of the panels and coffers with single figures and bucolic or Bacchic friezes have backgrounds painted red or blue (fig. 157–158.12).

Although some rooms of the Domus Aurea display cameo-like stuccowork, the delicate modeling and restrained use of color of the Chicago fragments argue against their having come from Nero’s palace. Eric Moormann has confirmed that the Chicago panels do not come from any Domus Aurea space that he knows either from personal examination or from the library of prints and photographs of lost or faded paintings.

Collecting Note

At the time of her donation, Edith Healy Hill (1849–1936) explained that the two panels had been brought by her family from Rome to Chicago some fifty years earlier. They were acquired by her father, well-known Chicago painter George P. A. Healy (1813–1894), when he and his family lived in Rome from 1868 to 1873. When Rome became the capital of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy in 1870, the population expanded and construction tried to keep pace. New residential quarters were terraced and constructed, especially on the Esquiline hill, destroying nearby tombs like the columbarium of Lucius Arruntius. At the same time, the antiquities market in Rome was thriving and virtually unregulated. Scavengers and dealers’ agents eagerly bought finds that building contractors were happy to sell. George Healy’s source told him that the reliefs were “found in Nero’s palace on the Palatine Hill—the Domus Aurea.” The dealer may have invented the Domus Aurea provenance on the basis of the delicate figures, Egyptian blue background, and gilding, in order to ask a higher price.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s two Roman relief panels are genuine but puzzling antiquities. They were assembled from ancient fragments and modern plaster about 1870 and sold to an American expatriate artist. Today it is wishful thinking to hope for precise information about their findspot or to identify additional architectural fragments from the same structure. Close examination makes it possible to date the reliefs to the early first century A.D., during the reign of Augustus or Tiberius. They are remnants of a skilled workshop’s decorations for the wall or ceiling of a room, very likely in a tomb. The images—griffins, stags, and winged women—belong to the visual language of political, mythological, and cultural renewal of the Golden Age of Augustus.

Sandra E. Knudsen

Technical Report

Technical Summary

These objects are fragments of stucco reliefs, embellished with pigment and gilding. The fragments have been arranged in two framed compositions, and significant restorations have been made to compensate for missing areas. Of the two groups, cat. 157, Relief Fragments Depicting a Seated Woman and a Griffin, is the more complete, and only the fragments of this group are definitively related to each other. Cat. 158, Relief Fragments Depicting a Winged Woman and Two Deer, could have been created from an assemblage of disparate fragments. On both sets of fragments, the stucco figures were applied over a blue background in two layers, resulting in contrasting low- and high-relief areas. Abundant evidence of fabrication such as toolmarks and—most compellingly—fingerprints are visible in both groups of fragments. Damages and areas of wear reveal the nature and extent of the preparation layer, which deviated markedly from what the ancients recommended as best practice. Significant traces of root marks, valuable evidence of antiquity, are present on all the fragments. The condition of the fragments varies widely and in some areas is somewhat compromised, but this does little to detract from the aesthetic impact or historical significance of the objects. In recent years, these two objects have received a considerable amount of conservation, primarily for aesthetic purposes.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

Primary material: stucco (presumed to be lime plaster)

The word stucco carries with it some confusion. It is used in different contexts, sometimes at cross purposes and with little consistency, and can refer to two separate processes and materials. The term can be used to describe plasterwork employed for architectural surfacing or decoration as opposed to that used for structural work. It can also be used to differentiate between plasters composed of lime (calcium oxide, CaO) and those composed of gypsum (calcium sulfate dehydrate, CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O).

In ancient Rome, lime plaster was used for architectural surfaces; it sets slowly and produces a very hard, long-lasting material. Gypsum plaster was preferred for molding and casting applications, such as for columns, pilasters, and cornices; it sets more quickly and produces crisp detail, but it tends to powder and decompose in moist environments.

This division in usage was not sacrosanct, however. Lime plaster was sometimes used for statuary. Gypsum plaster was used for architectural work in Egypt, particularly before the Greek conquest in 332 B.C. Moreover, as confirmed by both Vitruvius and Pliny, gypsum was often added to lime plaster in Greece and Italy. The broadest and most accurate definition for stucco, therefore, is a hard, slow-setting plaster based on lime and normally used for architectural work.

Lime is produced by the calcination, or burning, of calcium carbonates (CaCO3) such as limestone, marble, and chalk. When heated, carbon dioxide is driven off, leaving behind what is known as quicklime (calcium oxide, CaO). When powdered quicklime is combined with water and an aggregate such as sand or marble dust, a mortar or plaster is formed. Upon drying, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CaO2) combines with the mortar or plaster, turning it back into calcium carbonate via the carbonization process.

Secondary materials: gold, pigment

Gilding: Traces of a material resembling gold leaf are visible on the surface of the lamp held aloft by the woman in cat. 157 (fig. 157–158.13). In cat. 158, the same material can be seen on the pitcher, patera, and hair and wings of the woman (fig. 157–158.14) and on the antlers of the proper left deer (fig. 157–158.15). This material was not subjected to analysis but is presumed to be gold based on visual examination.

Paint: The planar surfaces of the panels were painted, creating a blue background around the white figures. The color is an intense blue-green, and individual particles or grains of the pigment itself are visible to the naked eye (fig. 157–158.16). The blue pigment was not sampled, but given its slightly green tonality, it may be a copper-based pigment such as Egyptian blue, a double silicate of copper and calcium (CaO ∙ CuO ∙ 4SiO2). This pigment was a staple of the Roman palette, and its use is becoming more readily identifiable with advances in multispectral imaging. According to ancient sources, blue pigments were expensive compared to other pigments and were thus regulated by law and used at the discretion of the client, as opposed to the artist. The ample use of blue pigment on these objects may reflect the considerable wealth of their patrons.

An ocher-colored pigment appears to have been used to draw a ground or level line under the figures (fig. 157–158.17 and fig. 157–158.18).

Without scientific analysis, it is difficult to determine whether the dark accretions and discoloration (fig. 157–158.19) constitute pigmented areas or contextual evidence. The extension of these accretions into the background (fig. 157–158.20) on cat. 158 contraindicate their function as a decorative embellishment, and their presence between the joins of the fragments on cat. 157 suggests that they are residues of the adhesive used to assemble the fragments.

Fabrication

Method

As with mosaics, the surface of a stucco relief belies the extent of the preparation below. Considerable information on the preparation of a flat stucco surface can be gleaned from ancient sources. To begin, a lattice of reeds was attached to a wooden frame. Plaster was applied over the reeds in successive layers to build up the wall. Vitruvius recommended six layers, three of mortar using coarse aggregates such as sand or crushed ceramic and three of mortar with finer aggregates such as marble dust. Pliny advised at least five coats, three of sand and two of marble. Each layer was applied while the previous layer was still damp, and each layer was smoothed and compacted. The surface was then burnished to a high polish.

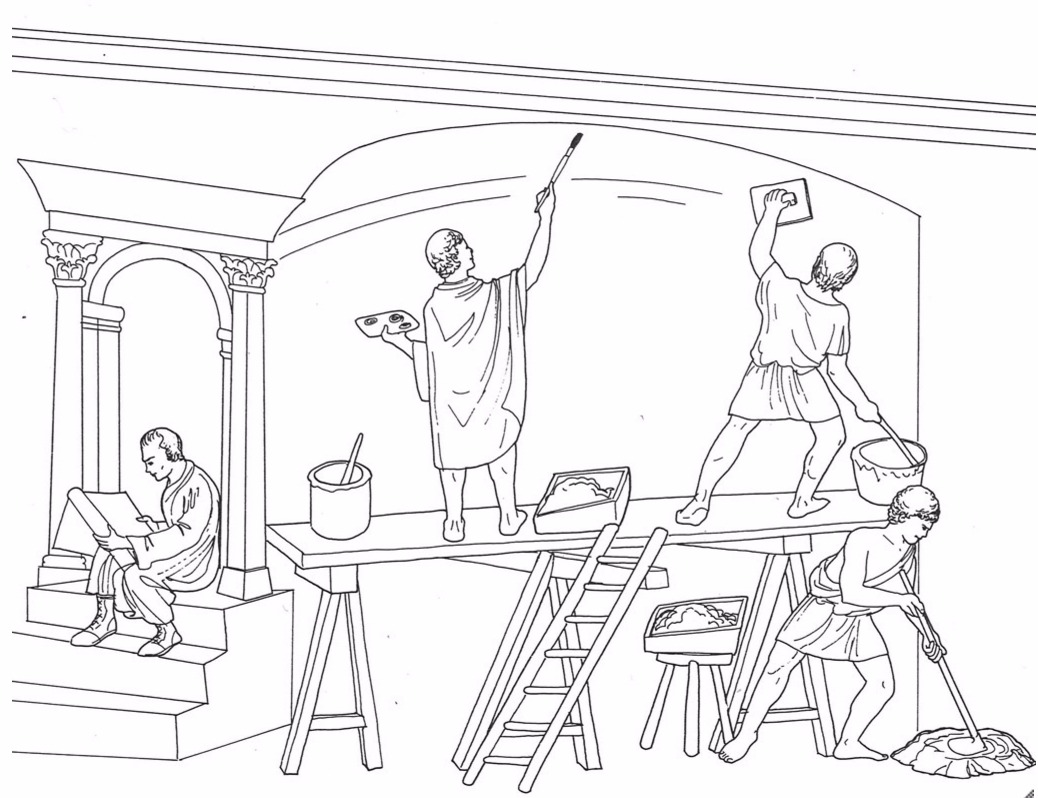

With the completed uppermost layer still damp, pigment was added using water as a vehicle, an approach validated both in the literature and in surviving funerary reliefs (fig. 157–158.21). The aqueous pigment solution combined chemically with the lime in the plaster and was bound to the surface during the carbonization process, producing a very durable painted surface. This method is, effectively, the fresco technique, the mainstay of Roman painting.

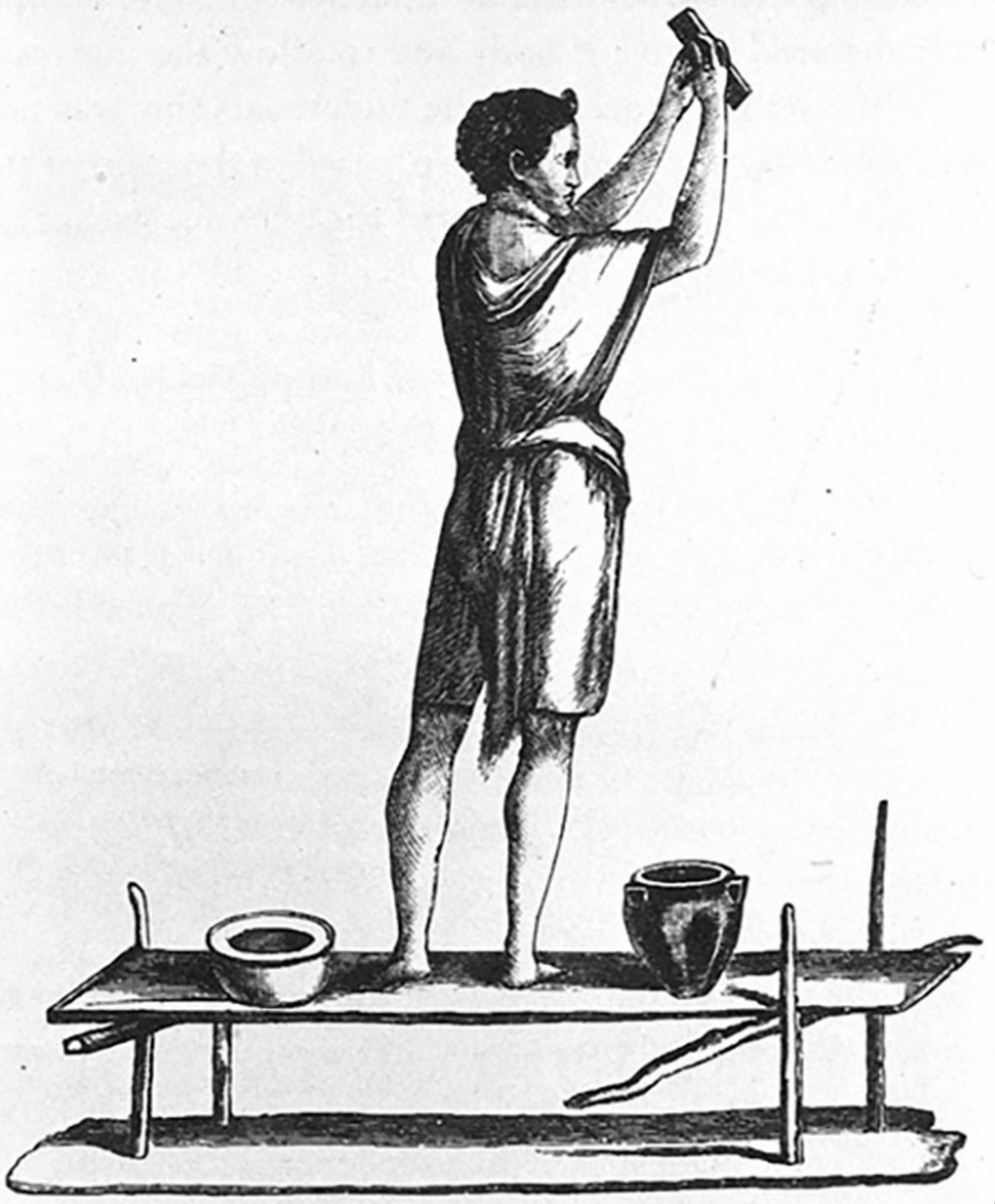

Before the painted wall had fully dried, the stuccoist applied the relief ornament. The method for this step, unlike the preparation of the underlayers, is not detailed in ancient sources. Traces of preliminary sketches appear on extant wall paintings as do keyed or roughened surfaces below the applied reliefs. The damp plaster was apparently applied to the prepared wall and modeled in situ with various tools. Craftsmen had to be extremely swift in their execution and, thus, extremely skilled, since errors had to be scraped off and plastered anew.

The amount of wall surface the craftsmen could complete in a given workday was limited. Consequently, differences between work carried out on different days, demarcated by fine lines and subtle variations in color, are often visible. These zones are termed giornate, after the Italian word for “day.”

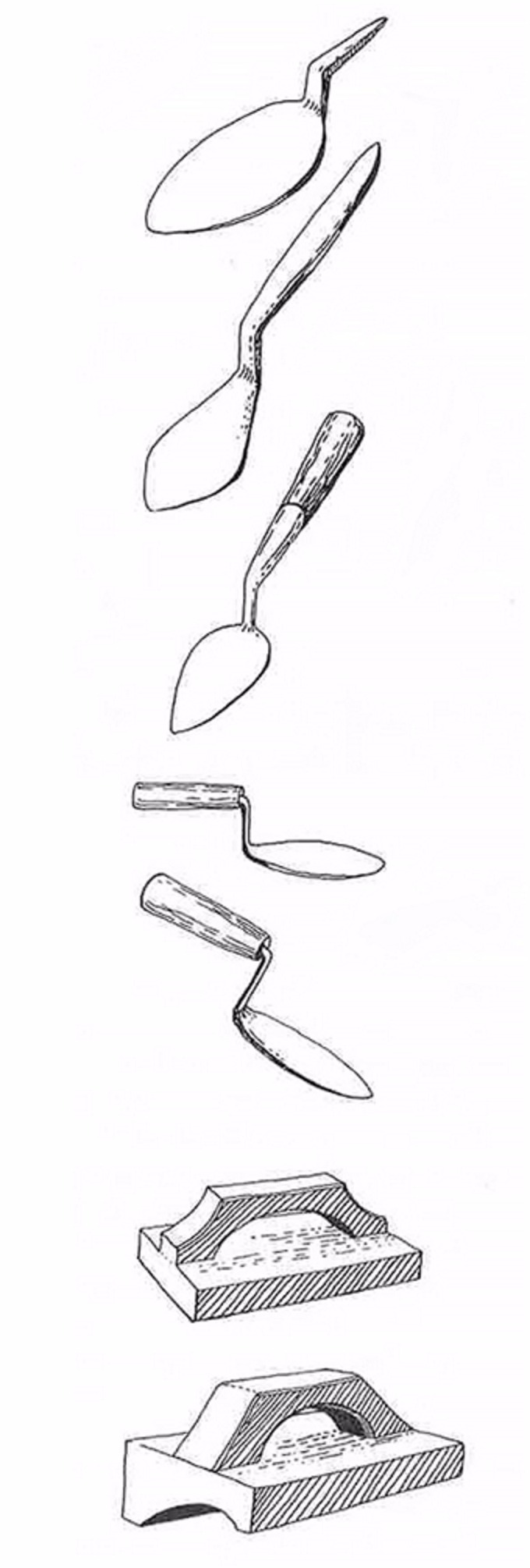

The tools used for creating stucco reliefs are very much like those employed by plasterers today. To prepare the wall, the trulla (an iron trowel resembling a modern pointing trowel) was used to apply masses of plaster to the bare surface. This tool had a flat, pointed blade that was attached by an offset neck to a short wooden handle. Evidence of its use exists on a number of carved funerary reliefs, and specimens, not always with the wooden handles preserved, are housed in several museums. To spread and smooth the plaster across the wall, the liaculum, or float, was used. This tool consisted of a flat wooden plate with a handle in the middle meant to be grasped from the back. Pictorial representations of craftsmen using the float are known (fig. 157–158.22 and fig. 157–158.21). Floats were also shaped to render moldings (fig. 157–158.23).

No visual representations exist by which to identify the tools used for the modeling of the reliefs themselves. Based on visual examination of surviving objects of the period, Roger Ling has posited the use of “various forms of spatula for shaping and indenting, of knives for cutting, and of a sharp instrument like a burin for incising, much the same tools, presumably, as were employed by modellers in clay.” Tools made of organic materials like wood or bone did not survive, but those made of metal, similar perhaps to a bronze implement with an upwardly curving blade (fig. 157–158.24), an example of which was found in a painters’ workshop in Aphrodisias, may have been used by stuccoists. The use of such tools in numerous trades and occupations, however, makes it difficult to identify those that were used expressly for stucco modeling. No conclusive evidence exists to support the use of molds or stamps to create reliefs of this type.

After both the paint and plaster dried, the gilding was applied. An adhesive, most likely a protein such as egg (or a gum or plant resin), was likely applied by brush to the selected areas of the stucco. The gold was then added to the prepared surface, and any gold that did not adhere to the adhesive was brushed away.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Several deep gouges extend into the preparatory layers. Visual examination of the interior of these gouges betrays the extent to which the execution of the preparatory layers falls short of Vitruvius’s ideal: the uppermost stratum is exceedingly thin and appears to have been spread directly upon a very coarse substratum (fig. 157–158.25). On cat. 157, a gouge extending from the griffin’s mouth to the woman’s right knee reveals extremely coarse aggregates resembling crushed ceramic or tile (fig. 157–158.26). In other areas, the rough particulates were dislodged, leaving only impressions of their size and shape. Similar gouges with fallen-away aggregates are also visible on cat. 158 (fig. 157–158.27). Even without the telltale evidence provided by the gouges, gradual erosion and abrasion of the top layer reveals the relatively large size of the aggregates beneath a thin surface coating (fig. 157–158.28). On cat. 158, an especially large aggregate, surprisingly close to the surface, is visible near the muzzle of the proper right deer (fig. 157–158.29).

The presence of blue pigment beneath a loss in the tail of the griffin confirms that the background was painted blue before the stucco embellishments were applied (fig. 157–158.30). Within this gap, a shallow incision mirrors the curvature of the tail. It is tempting to think of this line as evidence of a rudimentary sketch used by the stuccoist to guide application of the plaster. Close examination, however, reveals that the line extends over and through encrusting rootlets and is more likely to have been made by the restorer in aligning the fragments. Blue pigment is also visible within smaller voids, further confirming the uniform application of pigment to the background (fig. 157–158.31).

Examination of the figures, particularly the animals, reveals that the artist created the figures in two stages. First, a flat, fluid slurry of stucco was applied in low relief, likely with a brush. The watery consistency of the slurry is confirmed by air bubbles in the admixture that look like small pits and holes, exposed through age-related surface abrasion and weathering (fig. 157–158.15). Next, a thicker, creamier preparation of stucco was spatulated on in higher relief with a hard tool, as can be seen in the crisp edges surrounding and within the figures (fig. 157–158.32). The higher relief rendered elements closer to the foreground, and the lower relief provided contrast, an effect particularly noticeable in the opposing sets of legs on the animals (fig. 157–158.19 and fig. 157–158.18). Observation of the hindmost leg of the griffin reveals an apparent discrepancy between the first version in low relief and the ultimate rendition in high relief (fig. 157–158.33). Alternately, the profile of this leg, originally thicker, has been reduced by loss.

The evidence of use of a small tool or spatula with a sharp edge is conclusive on the jaw of the proper left deer, where a distinct gestural quality is rendered with a bold, rightward stroke (fig. 157–158.16). A strongly beveled cut made by a decisive upward sweep of the tool set at a 45-degree angle forms the throatlatch of the deer. The pointed tip of the tool was pressed against the base of the skull below the antlers with such force that it made a depression far into the substratum. The antlers were rendered by a swift series of alternating crimps at the top and bottom of the applied line of stucco. In the proper right deer, the blunt, flattened end of the tool made a depression in the stucco near the flank (fig. 157–158.34).

The stuccoist brandished the tool with considerable flourish, as evidenced by the robust modeling of the woman’s hair and face in cat. 158 (fig. 157–158.32). Despite this confidence, the composition was rendered in more than one decisive pass, as indicated by the double lines under the arm. A drop of stucco above the woman’s waist became somewhat flattened during the work but was never removed (fig. 157–158.35). A similar accretion of stucco that appears on the woman’s hip may represent either another drop or the remains of high-relief modeling of the drapery, which extends in low relief to the proper right of the figure.

In cat. 158, a faint, horizontal, shallow impression extending onto the background in line with and to the left of the ear on the proper left deer (fig. 157–158.36) seems to confirm that the surface of the background was still somewhat damp when the relief was applied, an approach supported by the literature. Faint lines around the figures also suggest that use of the tool removed the still-drying paint layer (fig. 157–158.32). A considerable amount of pigment visible along the edge of the high relief carving at the back of the woman indicates that the still-wet paint was transferred onto the stucco during the modeling process. Only analysis would be able to confirm whether the blue areas on the shoulder are the result of the same phenomenon or of the careless application of paint used during restoration.

For the frames, a broad tool or specially designed float was apparently dragged across the surface to produce flat bands, judging by the vertical striations within the depressions (fig. 157–158.37), and helped form the raised relief lines on either side of the bands. Scribing tools or rules were used to deeply score the centermost high-relief band. The egg-and-dart-like pattern overlapping the rectilinear forms was likely placed last. These embellishments also have vertical striations across their surfaces, but since the striations appear only on the crests of the high-relief areas, they were likely made by the tool that was used to apply and shape the primary contour. The detail was impressed by hand with a tool, and this step removed the striations from the tooled areas. Had the decorative strip been cast in a mold or made by impressing the surface with a carved or tooled mold, there would likely be no difference in texture or appearance between the high- and low-relief areas. The outermost vegetal decoration visible on the proper right side also appears to have been made freehand.

The varying appearances of the two deer, while perhaps indicating disparate compositional elements, may also be the product of a team of stuccoists. Confirmation of this working practice can be found in the fourth-century mausoleum below the basilica of Saint Sebastian outside Rome, which houses stuccowork bearing an inscription with five names. Other extant stuccos demonstrate the work of many hands.

Fingerprints made during the course of work are visible in many places (fig. 157–158.38, fig. 157–158.39, and fig. 157–158.40).

Three small incisions appear on the withers of the proper right deer on cat. 158 (fig. 157–158.41).

The gold on cat. 157 appears to have been applied in leaf as opposed to powder form, based on its hard edges and on the way it has adhered to the stucco’s surface (fig. 157–158.13). The physical condition of the gold in this area, particularly along the edges, lends weight to the theory that a more robust material, such as egg, was used as an adhesive. The gold used on cat. 158 is more ephemeral in nature and is appreciably worn away, suggesting that it was applied with a weaker, more fragile adhesive or perhaps in a looser form similar to shell gold (fig. 157–158.15). Where the gold has been lost, a tinted undercoat can be seen, perhaps a custom-made surface preparation to aid in gilding (fig. 157–158.15).

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No signature or other identifying marks were found, probably because of the fragmentary nature of the objects.

Condition Summary

Cat. 157 is composed of seven fragments (fig. 157–158.42). The back of the neck and the upper portion of the wing on the griffin are restorations (fig. 157–158.43). Given the angle of the head and the excess of material under the throat, it is unclear whether the shape of the arch on the griffin’s neck has been restored correctly, and liberties appear to have been taken with the abrupt transition in the angle of the feathers on the restored wing. As to the woman, the entire head, the left shoulder and arm, and most of the left side of the torso are restorations. Several cracks appear within intact fragments; some have been filled, but others have not. Similarly, some of the gaps between the fragments have been filled and retouched while others have not. The fragment of original frame on the top proper left corner is considerably darker than the fragment along the proper right side. The point of contact between the feet of the two figural elements on the central fragment proves that they are from the same composition. The other two related fragments, consisting of the posterior and the tail of the griffin, are likely from the same composition as well. But because considerable gaps separate the fragments, and the break edges cannot be examined, it is not possible to ascertain exactly how the fragments are related.

Cat. 158 consists of two large fragments floating like islands in a large surround of painted plaster fill (fig. 157–158.44). The lower legs of the woman below the knee are restorations, as are the legs and a considerable portion of the body of the proper left deer. None of the surrounding frame is original. As discussed in Evidence of Construction/Fabrication, the remarkable difference in the appearances of the two deer raises the possibility that they are not from the same composition. Another possibility is that the fragments do belong together but that the proper left deer was modeled by a different artist. Although the fragments are conspicuously separate from each other, the character and modeling of the woman and the proper left deer make it more plausible that the two fragments are related.

Abrasion is prominent on the painted surfaces of both sets of fragments, particularly in the top proper right corner of cat. 157. Cracks, voids, and pits are visible on the surfaces of the modeled stucco figures, along with isolated discolorations, stains, and irregular coloration. The irregular coloration is especially evident on cat. 157.

The intact original surfaces of the stucco decoration bear a burnished skin, a consolidative effect of the tooling and polishing. The intact surfaces also bear a slightly umber tone. Where the skin is compromised, the stucco beneath is much whiter and is friable and powdery. This effect is most evident in cat. 158 on the face of the proper right deer (fig. 157–158.29). Varying environmental conditions or the methodology of a different artist may have caused the accelerated deterioration.

The remains of overlying root marks are visible on the surfaces of the fragments, providing valuable evidence of antiquity (fig. 157–158.45 and fig. 157–158.46). These encrusting roots are not necessarily evidence of burial; if the wall was discovered in an intact structure, the rootlets may have been the anchors of climbing vegetation.

Conservation History

Presumably, the fragments’ first undocumented intervention was their current embedding in plaster. Being fragmentary, the stucco pieces were likely bonded together where edge contact made such action possible. The joined fragments were then floated in a surround of stained or painted plaster, backed, and framed. It is unknown whether at that time a consolidant or coating was applied to the fragments.

Treatment was first recorded in 1968, when the reliefs were cleaned with a solvent to remove grime and disturbing losses were inpainted. The entire surface was then coated with a solvent-borne acrylic resin.

In 1993, curatorial staff decided to display only cat. 157 in the galleries because of its more complete nature. Therefore, to better distinguish original areas from restorations, overpaint was removed from the panel with solvent. During this treatment, the subsequent discovery of additional fills made it clear that the relief panel was even more fragmentary than had originally been believed. Based on this new information, the plaster surround was once again inpainted, this time more articulately to demarcate more clearly the areas of original material and restoration.

For the opening of the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art in 2012, both sets of stucco fragments were displayed, necessitating a new campaign of treatment to harmonize the retouching in both sets of fragments. The original retouching on the more fragmentary cat. 158 (left untreated in 1993) varied widely in color and texture, making it difficult to discern original areas from restoration. Before applying new retouching, the original fragments were masked off with a thin film of latex. The most attractive section of the original painting scheme was identified, and the appearance of this area was replicated and extended across the relief by brush with acrylic paints using a variety of stippling and speckling techniques. Cat. 157 then required some modification so that it would more closely agree in color and texture with the newly retouched cat. 158. A similar procedure was followed: the figures were masked with latex, and elements of the color and texture of the retouching on cat. 158 were then selectively introduced, also by brush using acrylic paint in a stippling application, across the surface.

Rachel C. Sabino