Technical Report

Technical Summary

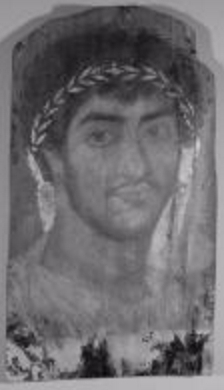

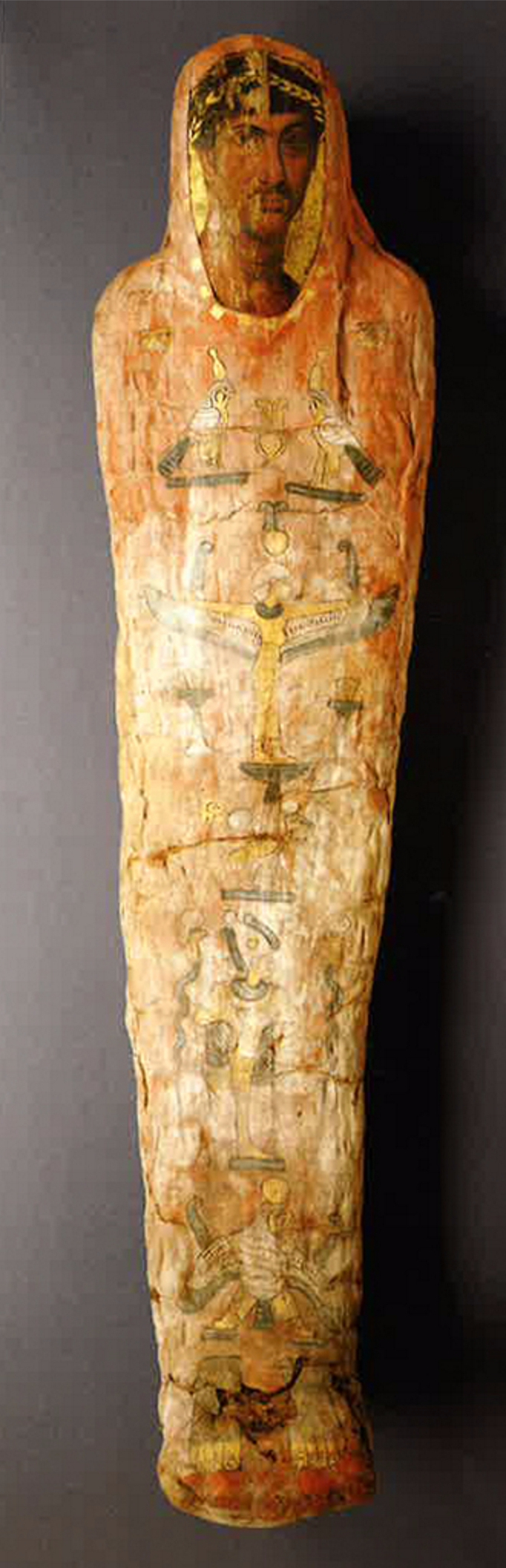

This imposing portrait was painted on a thin [glossary:panel] of fine-grained limewood (linden). The painting, roughly life-size in scale, is oriented vertically on a rectangular panel cut down in a manner consistent with other portraits from Hawara. As with many mummy portraits, the topography of the panel is convex, with the highest relief occurring across the forehead. Analysis confirms the presence of a uniform [glossary:ground] of lead white and the use of a restricted four-color [glossary:palette], consistent with the Greek tradition. The losses and thinly applied layers of paint make it possible to see traces of what appears to be an [glossary:underdrawing], done in a dark sepia-colored wash. Visual inspection suggests that the portrait was done in the [glossary:encaustic] technique and analysis confirms that the [glossary:binding medium] is pure beeswax. Traces of lead soaps were detected, but the absence of an alkali seems to indicate that their presence is attributable to the interaction of the lead ground with the beeswax and not to the use of a modified beeswax. Traces of paint at the far edges of the panel reveal that it had been painted in its entirety prior to insertion into a mummy. The portrait was also gilded with gold that is of very high quality. The relationships and overlaps between the paint layers and the gilding help somewhat in formulating a possible sequence of events in the execution of the painting. Vestiges of mummy wrappings and resin are visible on the portrait, and their path and location, along with other diagnostic features, seem to confirm that the opening of the window was angular rather than ovoid. This handling of the wrappings places the portrait in a subgroup of mummies with rhomboid-wrapped body fields. The object is in reasonable condition: the panel is structurally sound, but the painting has suffered considerable surface losses in conspicuous and important places, the attempted restoration of which has diminished somewhat the aesthetic quality of the portrait. The painting manifests virtually all the damages and condition issues associated with mummy portraits: vertical cracking, splitting, and warping of the panel; losses, cracks, and blooms in the paint layer; and surface staining, accretions, and adhered burial soil. The panel has received various conservation treatments, both documented and undocumented, including a comprehensive campaign of modern [glossary:retouching].

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the reader’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 15.47).

Structure and Technique

Support

Material

The primary [glossary:support] is a rectangular wooden panel planed to an average height of just under 2 mm. The [glossary:grain] direction runs vertically, following the height of the panel. The grain is extremely fine, barely discernible to the naked eye.

The panel was sampled to determine its composition. A microsample roughly 5 mm high and 1.5 mm wide was removed near an area of incipient cleavage, in a portion of the panel undamaged by insects, and free of [glossary:pigments], binding media, or conservation treatment materials. Although the International Association of Wood Anatomists (IAWA) requires that wood samples be cut into [glossary:transverse] (TS), [glossary:radial] longitudinal (RLS), and [glossary:tangential] longitudinal sections (TLS) for attribution, the sample from the mummy portrait was extremely brittle and delicate; rather than being cut, it was carefully broken across the TS and along the RLS and TLS. The sectioned sample was then analyzed using [glossary:scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy] (SEM/EDX) (fig. 4.22). Analysis confirmed that the panel was constructed from Tilia europaea (European lime or linden) and showed that the wood from the samples was in good condition. The condition of the samples reflects the overall condition of the panel.

Several characteristics of limewood made it desirable for the production of mummy portraits: the ease with which a uniform and regular surface could be achieved, and the wood’s relative impermeability, flexibility, and capacity to withstand attack by insects. The wood was capable of being planed to extreme thinness, which “has been explained as necessary for the ancient technique of encaustic; it has even been suggested that the panels must have been heated before or while the wax-based colors were being applied or worked in.” Limewood was not indigenous to Egypt and had to be imported from the northern Mediterranean, perhaps as timber or lumber or as already finished panels. It is possible that in ancient times, limewood was cultivated in the Fayum, a relatively more temperate region owing to its proximity to Lake Moeris, but “current evidence suggests that there were insufficient climatic and vegetational differences (compared with the present day) for Tilia sp. to grow as native to Egypt.”

Format

The top edge of the panel is cut in a broad, flat arch with some irregularities in the form of isolated high spots along the profile. A distinct notch of about 120 degrees has been cut into the top proper left corner. A slight, barely perceptible indentation appears on the proper left side, about level with the sitter’s cheekbone. The bottom edge of the panel is not planar but tapers down to the proper left, making the proper right corner appear higher.

Most mummy portraits have truncated perimeters to facilitate insertion into the mummy wrappings. The way in which the portraits are cut is broadly diagnostic of where they were made. The arched or rounded top of this portrait is common in panels from Hawara.

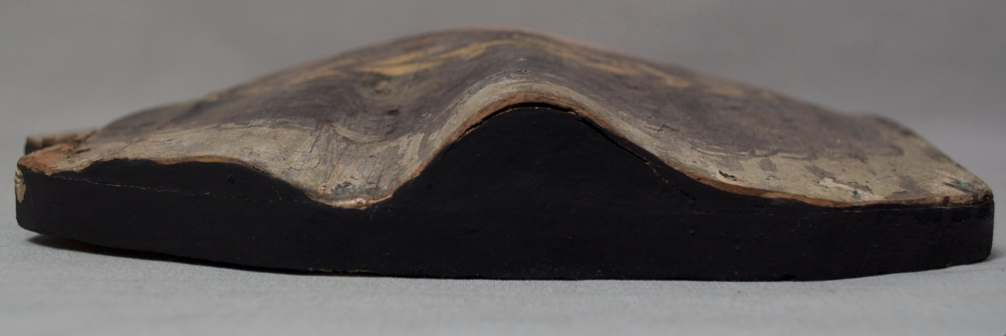

The panel is convex in shape across the crown of the head and forehead and tapers down to a more flattened profile at the neck (fig. 4.23). The curvature of the panels on mummy portraits has often been said to reflect the contours of the wrapped body beneath. Whether the panels were curved initially or became curved over time is a matter of considerable debate. Some scholars believe that steam or heat was applied to curve the panels before insertion and better accommodate the profile of the mummy without splitting. The flexibility of limewood, however, particularly when planed to such thinness, is more than sufficient for this purpose. Imaging studies of intact portrait mummies have demonstrated that there is not always a direct correlation between the curvature of the panels and the profile of the body beneath. Indeed, some mummy heads were deliberately pushed down by the embalmers to make the surface of the eventual wrappings more planar, perhaps even to act as support for the panel itself. Moreover, different species of wood with a marked disinclination to bending, such as oak, were chosen in other locations such as er-Rubayat, which may indicate that a curved profile was not the intended aesthetic. The behavior of unattached mummy portraits, particularly in response to conservation treatments or changes in environmental conditions, suggests that these curvatures were governed by more prosaic factors such as the way the timber was cut for use as a panel. Radial cuts would be expected to produce the most stable panels, whereas tangential cuts could result in severe curvatures. The manner of cutting relative to the wood anatomy is the most likely explanation for the pronounced undulations seen running perpendicular to the grain across the top edge of this portrait (fig. 4.35). These undulations are amplified throughout the rest of the panel, an effect best appreciated in [glossary:raking light] (fig. 4.34).

Scale

The overall dimensions of the panel are 41.9 × 24.1 cm, but the portion of the portrait that would have been visible within the wrapping measures 35 × 21.5 cm. The dimensions of this “window” are established by a combination of the location of the still-adhered wrappings and the placement of the gilding.

The anatomical measurements on this portrait appear to be life-size, contrary to many other portraits, which, although appearing life-size, are actually smaller. Although this portrait has been removed from its original context, it is reasonable to assume that, like most other examples, the portrait would have corresponded to the proportions of the mummy to which it had been attached.

Supplemental support

The panel rests on a topographic form made of a soft wood such as balsa and is secured by tacks evenly spaced around the perimeter. Two layers of wood, laminated together, were used to complete the profile. The outer edge of the support is painted matte black.

A photograph in the curatorial files shows the object with this cradle in place as early as 1962 (fig. 8.40). The topographic support was attached directly onto a cloth-covered backing board that was surrounded by a European-style gilt-wood frame. The earliest photograph in the conservation department files from 1972, possibly a pretreatment image, shows the panel mounted onto this cradle and still attached to the backboard, but with the gilt-wood frame removed.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

The presence or absence of a [glossary:sizing] layer on the panel cannot be adequately determined. Areas of exposed wood, particularly around the perimeter of the panel, display a very faint sheen, but this is more likely attributable to materials absorbed into the wood from the mummy and its wrappings or to residues from past conservation treatment.

It is generally accepted that to seal the wood and provide a uniform surface, the panels were probably sized with an adhesive prior to painting, presumably with protein such as egg or gelatin or with gum such as acacia (Acacia spp.) or tragacanth (Astragalus spp.). Due to their fragile nature and propensity to decay or alteration, the relative paucity of their application, and their tendency to be absorbed into the wood rather than to remain adhered to the paint layer, the organic adhesives and binders used for sizing are difficult to identify even by analytical means.

Ground application/texture

The ground was laid down uniformly across the panel in an extremely lean application that imparted little to no texture to the paint layer above it.

Color

Paint losses that expose the bare wood of the underlying panel reveal remains of the ground, which appear as a chalky, white dust (fig. 4.20).

Materials/composition

The choice of material for the ground in mummy portraits was governed chiefly by the choice of painting medium, either [glossary:tempera] or encaustic. After sizing, panels to be painted with tempera were given a gesso coating consisting of gypsum (calcium sulfate dihydrate, CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O) dispersed in a binder. Since wax does not adhere to gesso, encaustic paintings were previously assumed to have been prepared without a ground layer. Recently published studies are finding that some encaustic paintings did receive an initial preparatory layer of some kind.

This painting appears to have been given a comprehensive ground layer composed of basic lead carbonate (PbCO3)2 ∙ Pb(OH)2, or lead white, in an unidentified binder. Previously documented examinations of other portraits, particularly from Hawara, have also revealed the presence of lead grounds.

What is less easy to explain is the pervasiveness of calcite and gypsum across a significant portion of the surface, particularly in black areas where there is no apparent purpose for its addition as a colorant. Could it be that the ground layer was also bulked with calcite and gypsum in addition to lead? Further analysis would be needed to answer this question and determine the extent and application method of the calcite.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

While evidence of a comprehensive underdrawing is not abundant, within areas of loss and through thinly applied areas of paint around the tunic and mantle, it is possible to discern the presence of fine lines following the trajectory of the folds of drapery. These are particularly notable below the proper left shoulder (fig. 4.28). The lines are a deep-sepia color and, where applied, appear to have readily saturated the wood.

Within an area of loss on the proper right side of the neck, just below the jawline, several gray diagonal lines, clearly some kind of preparatory mark, are visible (fig. 4.24). Their placement within an essentially featureless area is curious. Perhaps they were added to indicate the placement of different colors for shading and modulating the otherwise uniform flesh tones.

Examination with [glossary:infrared reflectography] did not reveal additional areas of preparatory drawing beyond those visible to the naked eye (fig. 4.32), likely a result of the opacifying effect of the lead in the ground layer.

Dark-gray lines on the proper left appear at first to be related to an underdrawing but, on closer inspection, are actually final embellishments to the folds of drapery. This feature is discussed in greater detail in para. 64.

Medium/technique

The underdrawing was not subject to analysis, but it is reasonable to posit that the palette of pigments used to create the painting could have also served as the material for the underdrawing.

No direct evidence indicates how the artist applied the underdrawing. The character and handling of the lines as well as the way the marks saturated the wood gives the impression that the colorant was dispersed in a liquid medium with reasonable adhesive properties and that it was applied with a fine brush. Surviving paintbrushes from Egypt were constructed from palm fibers bound with strung fibers and frayed at one end to produce a bristle. But remains of hairs have also been found trapped within the paint films of portraits, so artists may have used brushes not unlike those used today.

The pigment may have been formed into a stick for drawing, akin to a modern pastel, but it is not likely that such a friable medium would have remained intact on the surface for so long.

Revisions

No revisions are discernible on visual examination.

Further examination with X-radiography also failed to demonstrate the presence of any reworked areas or overpainted sections (fig. 4.25). The lead ground likely hinders the imaging capabilities of the instrument.

Paint Layer

Binding media

Mummy portraits are divided into two groups according to their binding media: tempera and, more often, encaustic.

Analysis of the paint layer revealed the presence of beeswax, suggesting that this portrait was done using the encaustic technique, not surprising when considering the heavy [glossary:impasto] on the surface.

Palette

Technical examination revealed the presence of the following pigments: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3), gypsum (calcium sulfate dihydrite, CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O), red and yellow ocher, jarosite (a hydrous sulfate of potassium and iron, KFe3+3(OH)6(SO4)2), and carbon black.

These findings are consistent with the restricted four-color palette of Greek painters, known as tetrachromatikon. From just these four colors—white, red and yellow earths, and black—it is possible to obtain a remarkable range of hues, even shades of blue.

These basic pigments were available in Egypt. More geographically distant pigments, such as lead red sourced in Spain, are nonetheless attested on other mummy portraits.

The vivid, deep-purple coloration of the [glossary:clavus] suggested the use of supplemental pigments beyond those prescribed in the tetrachromatikon. Examination under [glossary:ultraviolet] light did not reveal any fluorescence in this area, making the presence of a [glossary:lake pigment] such as madder unlikely (fig. 4.27). In the hopes of detecting Tyrian purple, the area was subjected to analysis, but the absence of bromine contraindicated its use. Instead, iron oxides appear to have been used to color this area.

Application/technique

The precise working method of the encaustic painters has been debated for some time, including whether the artists worked the material hot or cold. Encaustic is derived from the Greek enkaio, “to burn in,” and the simplest preparation of the paint is to add pigment to molten wax. Beeswax, however, has a low melting point and thus cools extremely quickly. Paint made with beeswax would have required heat even during the painting process, although the high ambient temperatures of the region would have made it more tractable.

Alternatively, the wax might have been modified in some way. Beeswax can be mixed with an alkaline material such as [glossary:natron], and egg can then be added to produce a thick paint that dries more slowly. Indeed, Pliny the Elder described, albeit vaguely, a recipe for Punic wax, a modified beeswax that could be applied without the use of heat, like an oil paint. A number of published studies have attempted to identify intentionally modified beeswax. The natural changes that occur in beeswax through age and environment, however, have so far precluded irrefutable evidence of its modification.

Analysis of this portrait did reveal the presence of lead soaps, specifically lead stearate. In this instance, however, the lead soap (or salt) is attributable to the interaction of the lead white pigment with the free fatty acids of the beeswax. The absence of an alkaline component, such as sodium, seems to confirm that the wax was not deliberately [glossary:saponified] and that the medium is pure beeswax, not Punic wax.

Painting tools

Although the tools used with encaustic paintings are a matter of speculation, the instruments believed to have been used include the cestrum, cauterium, and pencillium. Pliny wrote of these tools, but not in the context of portrait painting. A representation of a portrait painter using similar tools has been found on the interior of a sarcophagus (see fig. 155–156.1).

The cestrum was a hard wax–working tool used cold. It was similar to an engraver, and its known purpose was to incise lines on ivory. The cauterium was a hard wax–working tool said to have the appearance of a metal spoon or hollowed-out spatula. It was used hot after being heated over coals. These two tools are believed to have been used to create the heavily textured, almost sculptural impasto surfaces of encaustic paintings. The pencillium was, fundamentally, a brush; both brush marks and hairs seen on the surfaces of portraits confirm its use.

Nevertheless, modern experimentation shows that all the characteristic marks seen on encaustic paintings can be made with just a brush, particularly if the wax is allowed to harden on the bristles, creating a stiff tool.

Evidence of toolmarks and paint handling

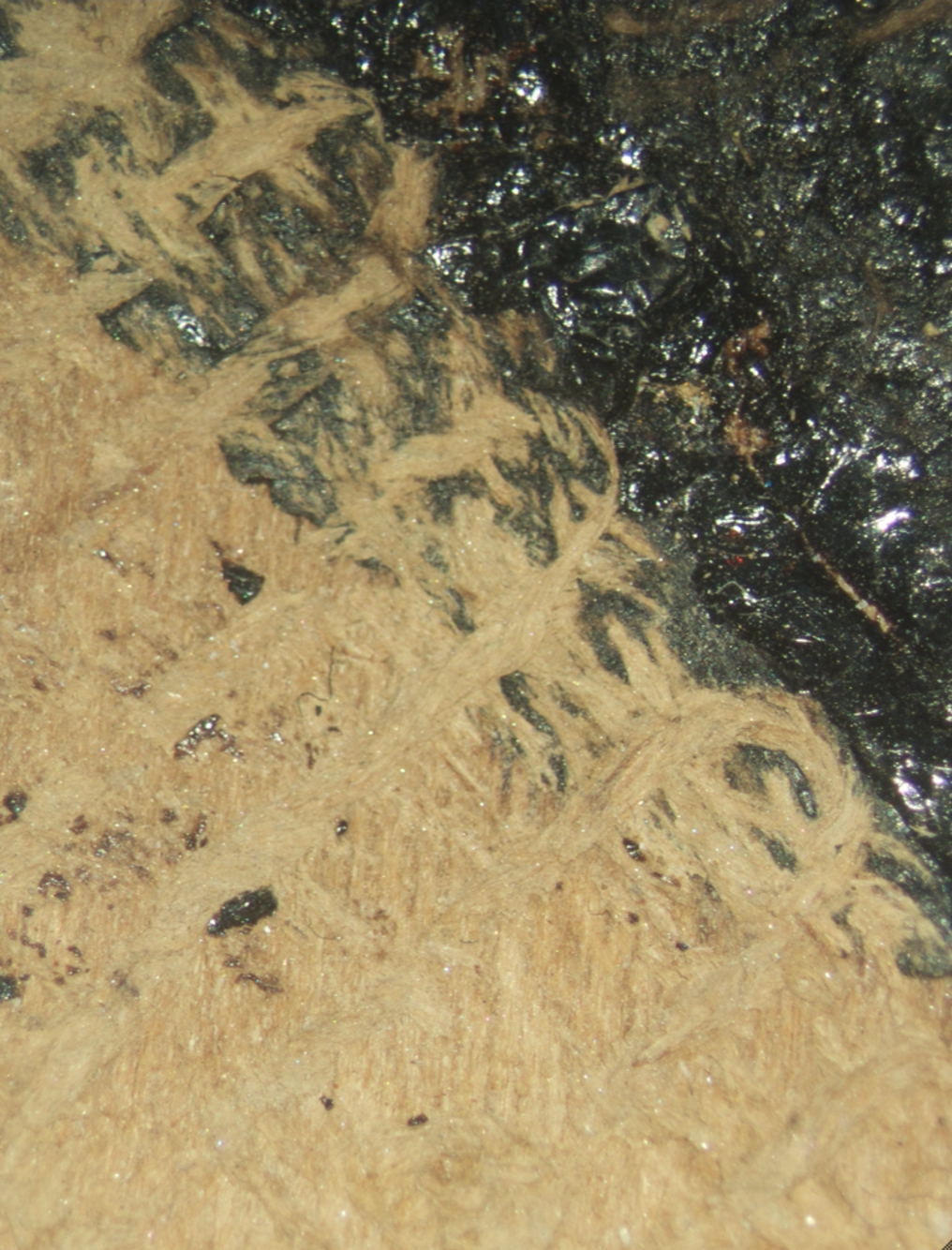

Traces of wax-working tools are in evidence uniformly across the panel, the texture of which is apparent in plain light but even better appreciated in raking light (fig. 4.21).

In the background, the textural areas have a gestural quality, with the zigzag lines typical of the encaustic technique (fig. 4.26 and fig. 4.33). These paint strokes are thin and evenly spaced, suggesting a rapid brushstroke with a rather small, likely pointed, tool. The handling of the paint closest to the neck is different from the more peripheral areas of the background. It has been applied with the same tool but in thinner, flatter, predominantly vertical strokes rather than high-relief diagonals (fig. 4.31). Perhaps the relative flatness of the background was a deliberate effect to focus the viewer’s attention to the face. Or perhaps it reflects the more measured approach necessary when painting so close to the already finished face as opposed to the peripheral areas, which could be handled more freely. The paint directly against the neck was applied in a single line following its exact contour (fig. 4.31). This could also have been done to emphasize the face, or it might simply reflect the ease of rendering the line thus. Despite the care taken to bring the two compositional elements into alignment, gaps can be seen along the interfaces of the proper left side (fig. 4.19).

On the neck and on the gather of fabric adjacent to the clavus, the wax was also applied on a diagonal, but in much thicker strokes, with what appears to be a broader, flatter implement (fig. 4.29).

The artist painted the eyebrows with delicate lines that follow the natural growth of the hair, using what appears to be the same tool employed in the background (fig. 4.30). This technique lends a heightened sense of naturalism to the portrait.

To render the hair, the artist first applied a uniform midbrown wash, then painted individual strands and curls in high relief in dark brown. The individual hairs were painted in a circular motion with a broad tool, possibly the same one employed on the tunic and on the neck (fig. 4.18). Although two brown tones were used, there appears to have been little intent to modulate the three-dimensionality of the hair using color. Instead, this illusion was achieved through the interplay of light and dark caused by the modeled surface of the wax.

A small triangular void appears between the bottom of the neck and the adjacent fabric of the mantle, and the topography of the curve used to render the bottom of the neck is visible beneath the paint film of the top of the tunic (fig. 10.41). A similar sequence of gaps and overlaps can be seen along the join between the neck and the background on the proper left side (fig. 4.19). Meanwhile, the heavier impasto used to render the mantle over the proper left shoulder appears to overlap the finer texture of the background (fig. 4.1). The relationships between these compositional elements suggest that the face and neck were painted first, the background next, and the tunic and mantle last. At the very least, some further reinforcement of the proper left shoulder was added after the background was laid down.

The artist left no marks or signatures.

Additional Materials

Textile

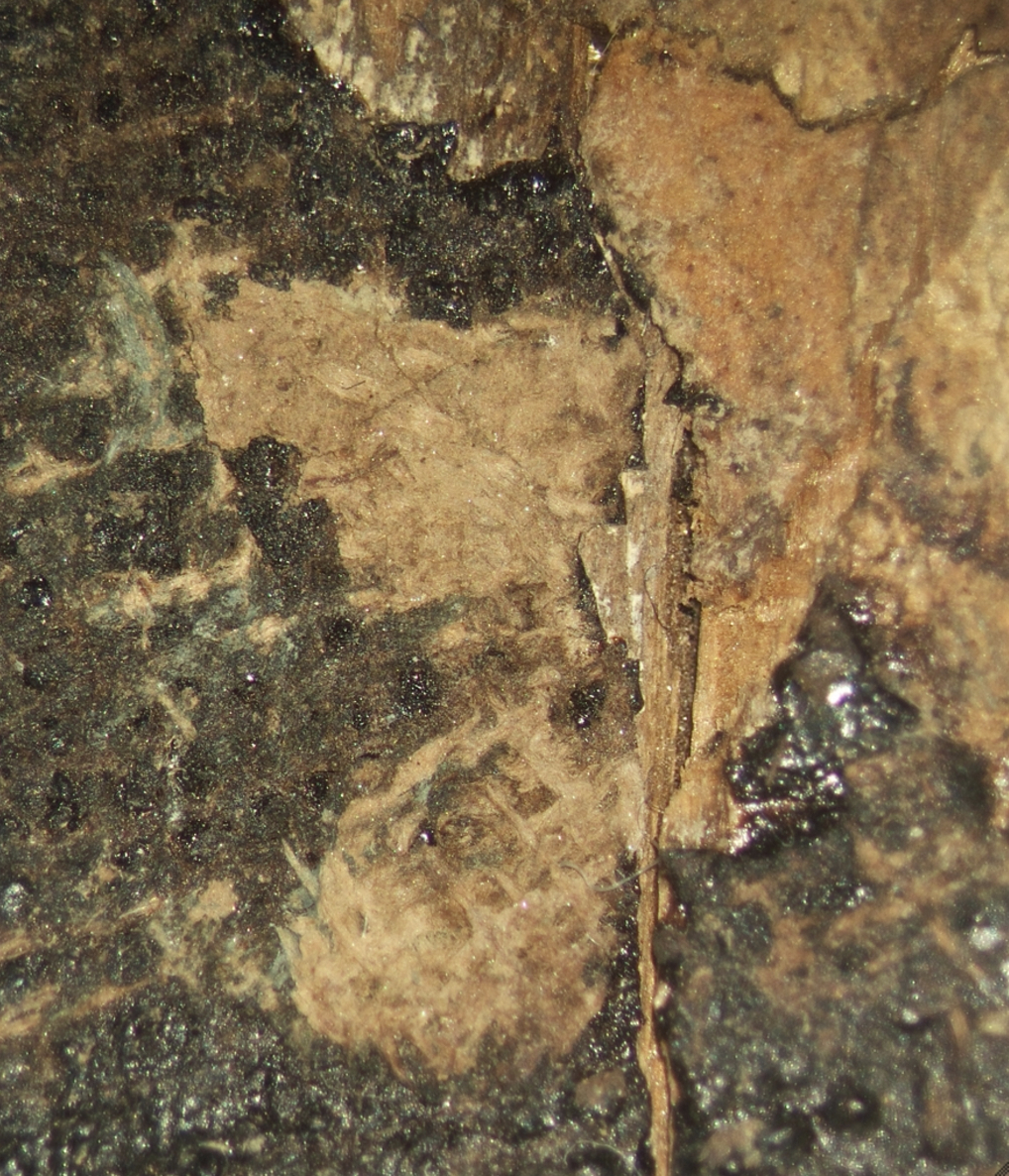

Remains of mummy wrappings are visible around the outer margins of the panel, particularly along the lower portion. Smaller vestiges of wrappings can be seen along the proper right side.

A visual inspection of the minor amounts of intact textile remaining on the surface of the portrait shows that at least two types of wrappings were used (fig. 8.36): one with a dense weave of small fibers (fig. 4.3) and another with a larger, more open weave of thicker fibers (fig. 8.37). In some places the remains of the coarser textile are only barely discernible on the surface of the panel (fig. 4.4). While it is unknown how many layers of wrappings the mummy would have had, the finer weave was clearly superimposed on the coarser one. The aesthetic implications of placing the more delicate textile closer to the surface seem obvious. The economic motivations for placing the presumably lower quality and less expensive cloth closer to the interior also seem obvious. But perhaps there was some relative difference in utility between the two fabrics. The coarser textile may have been more pliable and thus the preferred cloth for wrapping the body tightly, or it may have had other qualities that facilitated the mummification process.

The textile remnants are likely linen, the fabric commonly associated with Egyptian funerary practices. To the naked eye, the textile appears to be raw, undyed linen.

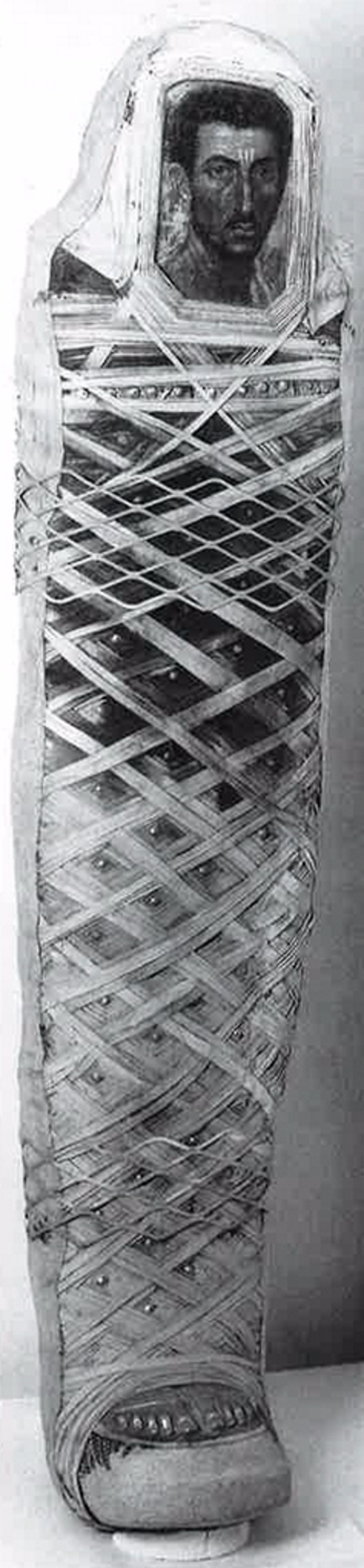

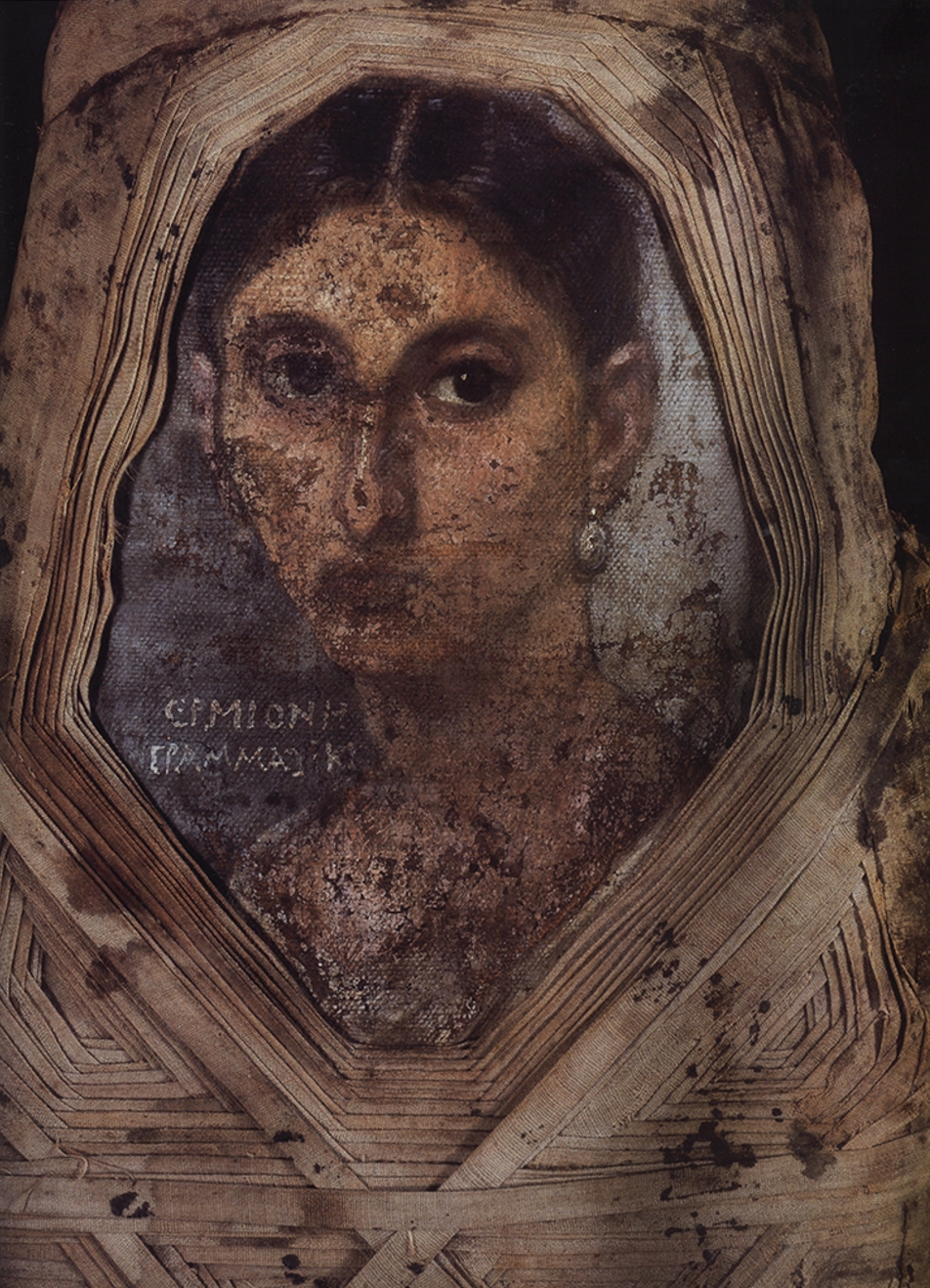

Based on the pattern of the still adhered textiles, the fabric was originally placed across the shoulders in two diagonal lines. The path of the wrappings is relatively unambiguous, and no remains of textile can be seen connecting or overlapping the lower ends of the two diagonals. These strips might have intersected at the center of the chest, as on a red-shroud mummy in Hildesheim (fig. 8.38). The vast majority of red-shroud mummies, however, display an ovoid opening around the portrait, such as that of the mummy of Herakleides (fig. 4.5). The lower portion of the mummy in the Chicago portrait was not wrapped in an ovoid format, so it most likely belongs in the subgroup of Roman mummies with rhomboid-wrapped body fields. These are characterized by plentiful strips of linen arranged in overlapping patterns of diagonal squares. These portraits often terminate in an angular base, either quite broad (fig. 8.39) or quite constricted (fig. 4.6) and resembling an upside-down trapezoid, although some have intersecting wrappings (fig. 4.7). The tops of the portraits in this subgroup were usually wrapped with the linen following the arch of the portrait, as seen on a fine example in Boston (fig. 4.8).

The weave on all the wrappings was placed diagonal to the grain of the wood.

Heavy black deposits appear on the surface of the wrappings along the bottom edge of the portrait. The composition and purpose of these deposits are unknown.

Vestiges of an unidentified ocher-colored material, likely associated with the funerary preparations, can be seen in various places on the portrait, particularly on the proper right side. A large accretion appears near the notch at the top corner, and two large lines appear along the splits, on the proper left side (fig. 4.9).

Traces of paint at the furthest edges of the panel indicate that the panel was originally painted in its entirety. The paint in sections that were once in contact with the wrappings, particularly at the bottom, was obliterated when the portrait was removed from the mummy upon excavation.

Resinous materials

Remains of the adhesives used to wrap the mummy are visible on the portrait. These accretions are heaviest along the bottom portion of the panel; they are also heavy along the sides of the panel, although their presence there is not continuous and looks more like discrete islands of material. These mummification materials appear as shiny brown deposits both within the wrappings and on bare surfaces of the panel (fig. 10.43). Analysis of samples taken from these areas confirms the presence of natural resin and tar.

Within many areas of the accreted resin, the weave of now-detached or disintegrated textile has been preserved in a negative impression (fig. 4.10). In other areas where the coarser textile has disintegrated, regularly spaced accretions of resin pushed through the weave and formed a lattice of sorts on the surface (fig. 4.4).

Gold

Two areas of the portrait have been gilded: a garland of rhomboid design and the background that is visible within the wrappings, a rather modest oval that does not cover a significant portion of the panel. The gold used for the wreath and the background is of the same high degree of purity, constituting a level of expenditure that perhaps might explain its restrained use in the background. The reserved application of gold in the background notwithstanding, the use of real gold places the sitter firmly in the upper echelons of society.

The adhesive used to affix the gold has not been identified, but the still-crisp edges of the rhomboids in the wreath indicate that this material was reasonably robust, likely made with a protein as opposed to a gum.

An accretion of wrapping overlying a segment of the laurel wreath (fig. 4.11) indicates that the wreath might have been gilded before the panel was inserted into the wrappings. The gilding in the wreath is quite painstaking and would have been far easier to carry out while the panel was separate from the mummy.

The gilding in the background, which alternately covers and skirts a margin around the hair (fig. 4.11), was obviously applied after the painting was completed but not necessarily before insertion. The irregular edge of the gilding on the proper left side (fig. 10.44) seems to confirm that the portrait was gilded after insertion. The placement of the background gilding indicates the path of the wrappings, and they appear to have been placed in a very tight oval around the sitter.

Aside from minor discordances along the interface between the figure and the gold, the gilding seems to have been done with considerable precision (fig. 10.42).

On the proper right shoulder, the artist further reinforced or demarcated the contours of the drapery with dark-gray lines. This was done after the gilding was applied, as evidenced by the superimposition of the topmost dark line over the gold (fig. 4.12).

Condition Summary

The object is in reasonable condition. The panel is structurally sound, but the painting has suffered considerable surface loss in conspicuous and important places, the attempted restoration of which has diminished somewhat the aesthetic quality of the portrait.

Like most mummy portraits, the painting exhibits splitting and cracking along the vertical axis. These cracks are the result of the inherent instability of the thinly planed wood and varying environmental conditions, sometimes in combination with the prolonged pressure from the wrappings. Numerous small, shallow splits are visible along the bottom edge of the panel and around the face. Several deeper cracks with accompanying undulation and deformation are present on the proper left side. Little active movement is noted in association with these features.

The exposed wood on the [glossary:rip-cut] edges of the panel at left and right appears compact and sound. The exposed wood on the [glossary:crosscut] edges of the panel at top and bottom is fibrous and soft with associated splintering and minor losses. A large area in the center of the panel near the bottom edge appears to have been weakened by insect damage. The wood in this area is torn, and traces of [glossary:exit holes] punctuate the perimeter of the tear.

The paint layer appears embrittled and prone to [glossary:cleavage], with resultant losses that are extensive and disfiguring. Patterns of [glossary:craquelure] are consistent with those observed on other mummy portraits. Two types of cracks can be seen: one runs diagonal to the grain, producing irregular quadrangles (fig. 4.13), and another follows the grain, producing frayed or jagged cracks (fig. 15.48).

A bloom can be seen in the flesh tones at the back of the neck (fig. 4.14). Blooms are common to mummy portraits and are thought to be related to the degradation-linked migration of organic components from the beeswax.

A dark-brown deposit appears in the hair on the proper left side. This may be connected to the mummy wrappings, which may have become dislodged after burial and stained the area. But many mummy portraits display stains caused by exudates from the corpse itself, and this dark area could be an example of such discoloration.

Fibers of cotton wool, perhaps from a previous cleaning, are trapped in the paint at intervals across the surface.

Small accretions and adhered soil appear throughout (fig. 4.15).

The noticeable delamination of the panel from the support along the proper right side indicates that the panel was held in some tension (fig. 4.16). Fortunately, this dimensional instability was released along the join between the panel and the support rather than through the panel itself.

Conservation History

Most mummy portraits have received some kind of conservation treatment. Many of the portraits discovered by Petrie, for example, were impregnated with paraffin wax, which has become the source of numerous problems. No paraffin wax was detected during analysis, indicating that the portrait was spared this treatment.

The surface was at some point, however, comprehensively consolidated with cellulose nitrate, a treatment that has its own drawbacks. The portrait’s conservation treatment cannot be considered a success: in many places fragments of paint are adhered to the surface with no relationship to their original position, and they are often adhered to the surface upside down (fig. 4.17). Continued lifting of the paint films further suggests either that the consolidation was poorly executed or that the material has reached the end of its useful life.

In addition to having been consolidated, the portrait was also heavily retouched with colors that either aged poorly or did not blend with the surrounding colors of the original. Matte-purple retouching is visible above the proper left eye, in the lower portion of the proper right cheek, on the throat, and on the proper right side of the neck (fig. 4.30). Very heavy opaque-white overpaint with a pronounced yellow tone is visible above the proper right cheek, within the bottom lip, around the chin, and above the proper right eye between the eyebrows and into the nose. Attempts were apparently made to retouch the gold using ocher-colored paint with some amount of mica or gold powder (fig. 15.46). It is unknown when these interventions occurred. A zinc-barium compound, likely lithopone, was detected pervasively in these restored areas. The first commercial production of lithopone occurred around 1874, placing the restoration sometime between that year and 1962, the date of the earliest known photo in which the restorations can be seen.

The first documented treatment was carried out in April 1978, which states that “cleavages” appear to have been consolidated with an extremely dilute, unspecified [glossary:size]. The conservation report does not specify whether these refer to the splits in the panel or to active and incipient losses in the paint films themselves, but the very low concentration of the [glossary:consolidant] used suggests the latter.

Documentation also exists from 1982, but it is not clear whether it refers to an examination or an intervention.

The most recently recorded treatment was carried out in 2004 to address the separation between the support and the panel at proper right as well as the lifting paint. A dilute acrylic resin was used to consolidate the areas of lifting paint that showed greatest movement.

Rachel C. Sabino