Technical Report

Technical Summary

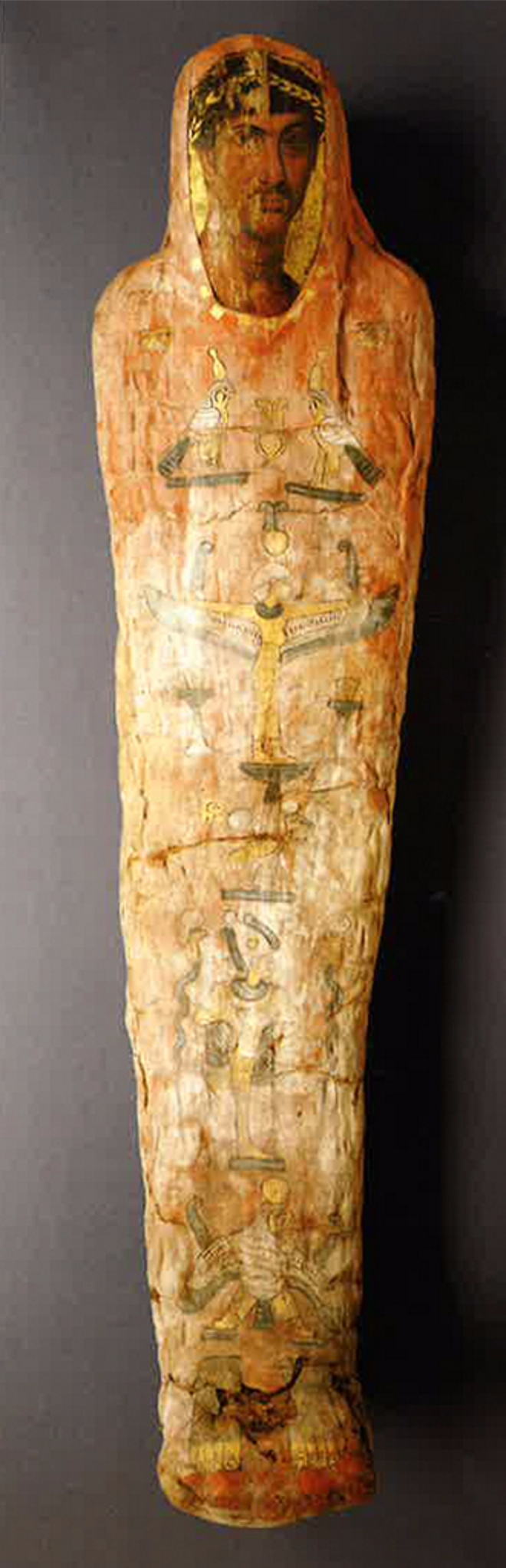

This evocative portrait was painted on a thin [glossary:panel] of fine-grained limewood (linden). The painting, slightly smaller than life-size, is oriented vertically on a rectangular panel cut down in a manner consistent with other portraits from Hawara. As with many mummy portraits, the topography of the panel is convex, with the highest relief occurring across the forehead. Analysis confirms the presence of a uniform [glossary:ground] of lead white. Losses to the paint layer make it possible to see the [glossary:underdrawing], which appears to show at least one revision. Analysis reveals a restricted four-color [glossary:palette], consistent with the Greek tradition, that is supplemented by additional [glossary:pigments]. The portrait was previously assumed to be [glossary:tempera], based on its matte appearance, the striking [glossary:tratteggio] treatment around the eyes, and the relative absence of the hallmark [glossary:impasto] of the [glossary:encaustic] technique, which dominates the oeuvre. Surprisingly, analysis proved that, to the contrary, beeswax was incorporated into the [glossary:binding medium]. This panel is one of a growing corpus of portraits assumed to be tempera based on visual appearance but proved to be encaustic upon technical investigation; this medium might better be described as wax-tempera. With the possible exception of the visual appearance of the paint, which is extremely thin, there is no analytical support for the wax’s having been modified, so it is likely to be pure beeswax. Traces of paint at the far edges of the panel confirm that it was painted in its entirety prior to insertion into the mummy wrappings. The portrait was also gilded, the most striking example being the delicate ivy wreath around the sitter’s head. Physical clues, as well as evidence of differing grades of purity in the gold used for the gilded areas, seem to confirm that the wreath was added before insertion and that the background was applied after wrapping. Considerable remnants of mummy wrappings and vestiges of resin are visible on the portrait, and their path and location, along with other diagnostic features, indicate that the opening of the window was angular rather than ovoid. This handling of the wrappings places the portrait in a subgroup of mummies with rhomboid-wrapped body fields. The relationships between the paint layer, the gilding, and the textile offer a possible sequence of events in the execution of both the painting and the funeral preparations. The painting manifests virtually all the damages and condition issues common to mummy portraits: vertical cracking, splitting, and warping of the panel; losses, cracks, and blooms in the paint layer; and surface staining, accretions, and adhered burial soil. The object is in reasonable condition with a roughly equal number of surface and structural issues, and although the latter are somewhat disfiguring, they do not diminish the aesthetic and emotional impact of the portrait. The object has undergone conservation treatments, both documented and undocumented, but has fortunately been spared major [glossary:retouching].

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the reader’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 15.47).

Structure and Technique

Support

Material

The primary [glossary:support] is a rectangular wooden panel planed to an average height of just under 2 mm. The [glossary:grain] direction runs vertically, following the height of the panel. The grain is extremely fine, barely discernible to the naked eye.

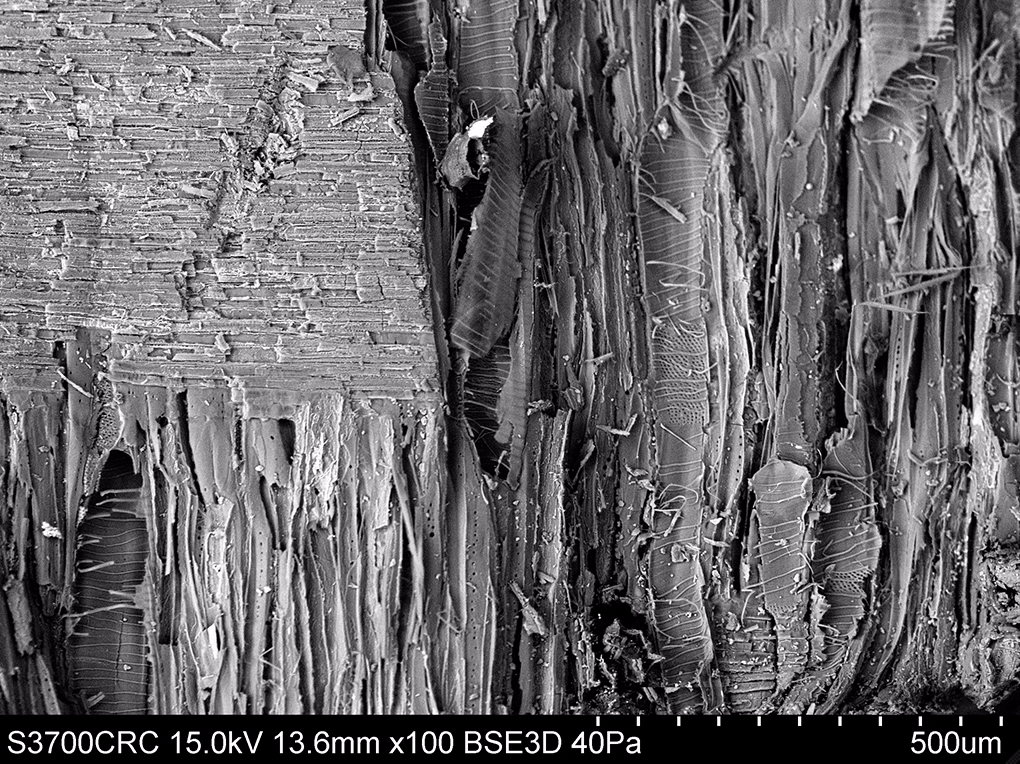

The panel was sampled to determine its composition. Three minimally invasive samples of approximately 3 mm2 were taken near existing splits and lifting areas, in portions of the panel undamaged by insects, and free of pigments, binding media, or conservation treatment materials. Although the International Association of Wood Anatomists (IAWA) requires that wood samples be cut into [glossary:transverse] (TS), [glossary:radial] longitudinal (RLS), and [glossary:tangential] longitudinal sections (TLS) for attribution, the samples from the mummy portrait were extremely brittle and delicate; rather than being cut, they were carefully broken across the TS and along the RLS and TLS. Each sectioned sample was then analyzed using [glossary:scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy] (SEM/EDX) (fig. 4.22). Analysis confirmed that the panel was constructed from Tilia europaea (European lime or linden) and showed that the wood from the samples was in fair condition. The condition of the samples reflects the overall condition of the panel.

Several characteristics of limewood made it desirable for the production of mummy portraits: the ease with which a uniform and regular surface could be achieved, and the wood’s relative impermeability, flexibility, and capacity to withstand attack by insects. The wood was capable of being planed to extreme thinness, which “has been explained as necessary for the ancient technique of encaustic; it has even been suggested that the panels must have been heated before or while the wax-based colors were being applied or worked in.” Limewood was not indigenous to Egypt and had to be imported from the northern Mediterranean, perhaps as timber or lumber or as already finished panels. It is possible that in ancient times limewood was cultivated in the Fayum, a relatively more temperate region owing to its proximity to Lake Moeris, but “current evidence suggests that there were insufficient climatic and vegetational differences (compared with the present day) for Tilia sp. to grow as native to Egypt.”

Format

The top edge of the panel is cut in a modified arch, with the center appearing almost pointed rather than rounded. The proper right edge is nearly straight and has a small outward protrusion at the bottom. The proper left side displays some undulation at the top corner adjacent to the hair. A subtle notch or shoulder has been cut into the proper left side, level with the hollow of the sitter’s throat. Along the bottom edge a slight undulation appears toward the proper left corner, and the proper right corner has been cut off at an angle of about 30 degrees.

Most mummy portraits have truncated perimeters to facilitate insertion into the mummy wrappings. The way in which the portraits are cut is broadly diagnostic of where they were made. The arched or rounded top of this portrait is common in panels from Hawara.

The panel is convex across the crown of the head and forehead and tapers down to a more flattened profile at the chin (fig. 4.23). The curvature of the panels on mummy portraits has often been said to reflect the contours of the wrapped body beneath. Whether the panels were curved initially or became curved over time is a matter of considerable debate. Some scholars believe that steam or heat was applied to curve the panels before insertion and better accommodate the profile of the mummy below without splitting. The flexibility of limewood, however, particularly when planed to such thinness, is more than sufficient for this purpose. Imaging studies of intact portrait mummies have demonstrated that there is not always a direct correlation between the curvature of the panels and the profile of the body beneath. Indeed, some mummy heads were deliberately pushed down by the embalmers to make the surface of the eventual wrappings more planar, perhaps even to act as support for the panel itself. Moreover, different species of wood with a marked disinclination to bending, such as oak, were chosen in other locations such as er-Rubayat, which may indicate that a curved profile was not the intended aesthetic. The behavior of unattached mummy portraits, particularly in response to conservation treatments or changes in environmental conditions, suggests that these curvatures were governed by more prosaic factors such as the way the timber was cut for use as a panel. Radial cuts would be expected to produce the most stable panels, whereas tangential cuts could result in severe curvatures. The manner of cutting relative to the wood anatomy is the most likely explanation for the pronounced undulations seen running perpendicular to the grain across the top edge of this portrait (fig. 4.35). These undulations are amplified throughout the rest of the panel, an effect best appreciated in [glossary:raking light] (fig. 4.34).

Scale

The overall dimensions of the panel are 39.4 × 22 cm, but the portion of the portrait that would have been visible within the wrapping measures about 31 × 17.5 cm. The dimensions of this “window” are established by the profile of the still-adhered wrappings, the placement of the gilding, and a line of demarcation created by the preferential staining of the portion of the paint layer not in direct contact with the wrappings.

Like most extant portraits, the visage on this portrait appears life-size to the viewer, but the anatomical measurements are actually somewhat smaller than life-size. Although this portrait has been removed from its original context, it is reasonable to assume that, like other examples, the portrait would have corresponded to the proportions of the mummy to which it was once attached.

Supplemental support

The panel rests on a topographic form made of a soft wood such as balsa and is secured by tacks evenly spaced around the perimeter. Two layers of wood, laminated together, were used to complete the profile. The outer edge of the support is painted matte black.

A photograph in the curatorial file shows the object with this cradle in place as early as 1962 (fig. 8.40). The topographic support was attached to a cloth-covered backing board that was surrounded by a European-style gilt-wood frame. The earliest photograph in the conservation department files from 1972, possibly a pretreatment image, shows the panel mounted onto this cradle and still attached to the backboard, but with the gilt-wood frame removed.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

The presence or absence of a [glossary:sizing] layer on the panel cannot be adequately determined. Areas of exposed wood, particularly around the perimeter of the panel, display a very faint sheen, but this is more likely attributable to materials absorbed into the wood from the mummy and its wrappings or to residues from past conservation treatment.

It is generally accepted that to seal the wood and provide a uniform surface, the panels were probably sized with an adhesive prior to painting, presumably with protein such as egg or gelatin or with gum such as acacia (Acacia spp.) or tragacanth (Astragalus spp.). Due to their fragile nature and propensity to decay or alteration, the relative paucity of their application, and their tendency to be absorbed into the wood rather than to remain adhered to the paint layer, the organic adhesives and binders used for sizing are difficult to identify even by analytical means.

Ground application/texture

The ground was laid down uniformly across the panel in an extremely lean application that imparted little to no texture to the paint layer above it.

Color

Paint losses that expose the bare wood of the underlying panel reveal remains of the ground, which appear as a chalky, white dust (fig. 4.20).

Materials/composition

The choice of material for the ground in mummy portraits was governed chiefly by the choice of painting medium, either tempera or encaustic. After sizing, panels to be painted with tempera were given a gesso coating consisting of gypsum (calcium sulfate dihydrate, CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O) dispersed in a binder. Since wax does not adhere to gesso, encaustic paintings were previously assumed to have been prepared without a ground layer. Recently published studies are finding that some encaustic paintings did receive an initial preparatory layer of some kind.

This painting appears to have been given a comprehensive ground layer composed of basic lead carbonate (PbCO3)2 ∙ Pb(OH)2, or lead white, in an unidentified binder. Previously documented examinations of other portraits, particularly from Hawara, have also revealed the presence of lead grounds.

What is less easy to explain is the pervasiveness of calcite across a significant portion of the surface, particularly in black areas where there is no apparent purpose for its addition as a colorant. Could it be that the ground layer was also bulked with calcite in addition to lead? Further analysis would be needed to answer this question and determine the extent and application method of the calcite.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

The artist appears to have sketched out most of the portrait, not only the primary outlines of the face and its features and the folds in the tunic and the mantle, but also minute details in the paint layer, such as the small patch of hair below the bottom lip where individual lines are visible (fig. 4.28). Parts of the underdrawing are visible in the beard on the proper right side (fig. 4.24), along the proper right eyebrow (fig. 4.32), at the center of the throat (fig. 4.25), along the back of the neck at proper right (fig. 4.24), and within the folds of the mantle at proper right (fig. 4.27). The drawing was executed in a black or dark-gray material, but in some areas white lines appear next to the black ones (fig. 4.21). Rather than indicating two drawings using two materials, the white lines probably represent the preferential adherence of the white ground caused by the consolidative effect of the binder in the drawing media.

Where the paint films are intact, [glossary:infrared reflectography] does not reveal additional areas of preparatory drawing (fig. 4.26), likely a result of the opacifying effect of the lead in the ground layer.

A particularly dark line at the base of the neck on the proper right side (fig. 4.33) overlies the gilding and paint layer and is not part of the underdrawing. This feature is discussed in greater detail in para. 61.

Medium/technique

The underdrawing was created using carbon black pigment.

No direct evidence shows how the artist applied the underdrawing. The character and handling of the lines gives the impression that the colorant was dispersed in a liquid medium with reasonable adhesive properties and that it was applied with a fine brush, although, given the varying thickness of the lines, the painter could have used more than one type of implement. Surviving paintbrushes from Egypt were constructed from palm fibers bound with strung fibers and frayed at one end to produce a bristle. But remains of hairs have also been found trapped within the paint films of portraits, so artists may have used brushes not unlike those used today.

The pigment may have been formed into a stick for drawing, akin to a modern pastel, but it is not likely that such a friable medium would have remained intact on the surface for so long.

Revisions

A very fine, crisp, dark-gray line paralleling the contour of the proper left lower eyelid is visible in a loss about 5 mm below the extant pigment beneath the eye (fig. 4.31). The presence of this mark so far below the lid raises the possibility that it formed part of an earlier compositional sketch in which the face was oriented further down the panel.

Paint Layer

Binding media

Mummy portraits are divided into two groups according to their binding media: tempera and, more often, encaustic. Because of the difficulty in isolating the binders used for tempera, paintings are usually classified by their surface characteristics and the handling of the paint rather than by chemical analysis. Tempera paintings have a flat, matte effect; depth and texture are achieved with outlining, layering, and [glossary:crosshatching] techniques. In this portrait, the relative lack of impasto, the matte finish, and the emphatic use of tratteggio, visible around the bridge of the nose and around the eyes (fig. 4.19), indicate tempera.

Analysis of the paint layer, however, revealed the presence of beeswax, suggesting that the painting was done using the encaustic technique. Published analyses of a number of other portraits visually identified as tempera have likewise revealed the presence of beeswax. Based on the similar results of these binding media analyses, the term “wax-tempera” has been proposed as a more accurate, comprehensive description of such portraits.

Palette

Technical examination revealed the presence of the following pigments: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3), red and yellow ocher, jarosite (a hydrous sulfate of potassium and iron, KFe3+3(OH)6(SO4)2), and carbon black.

These findings are consistent with the restricted four-color palette of Greek painters, known as tetrachromatikon. From these four colors—white, red and yellow earths, and black—it is possible to obtain a remarkable range of hues, even shades of blue.

These basic pigments were available in Egypt. More geographically distant pigments, such as lead red sourced in Spain, are nonetheless attested on other mummy portraits.

The area within the [glossary:clavus] on the proper right side fluoresces a pale pink under [glossary:ultraviolet] radiation (fig. 4.29), suggesting the use of a [glossary:lake pigment]. Scientific analysis has confirmed the presence of madder blended with Egyptian blue.

Application/technique

The precise working method of the encaustic painters has been debated for some time, including whether the artists worked the material hot or cold. Encaustic is derived from the Greek enkaio, “to burn in,” and the simplest preparation of the paint is to add pigment to molten wax. Beeswax, however, has a low melting point and thus cools extremely quickly. Paint made with beeswax would have required heat even during the painting process, although the high ambient temperatures of the region would have made it more tractable.

Alternatively, the wax might have been modified in some way. Beeswax can be mixed with an alkaline material such as [glossary:natron], and egg can then be added to produce a thick paint that dries more slowly. Indeed, Pliny the Elder described, albeit vaguely, a recipe for Punic wax, a modified beeswax that could be applied without the use of heat, like an oil paint. A number of published studies have attempted to identify intentionally modified beeswax. The natural changes that occur in beeswax through age and environment, however, have so far precluded irrefutable evidence of its modification.

If the painting process using the encaustic technique is ambiguous, even less certain is the method used in wax-tempera paintings. Modern experimentation suggests that in such paintings the background areas and the undertones of the flesh might have been applied by brush quickly and in broad strokes using a wax [glossary:emulsion]. Over this layer, the encaustic pigments would have been applied in a more subtle impasto than was the case on encaustic paintings.

Painting tools

Although the tools used with encaustic paintings are a matter of speculation, the instruments believed to have been used include the cestrum, cauterium, and pencillium. Pliny wrote of these tools, but not in the context of portrait painting. A representation of a portrait painter using similar tools has been found on the interior of a sarcophagus (see fig. 155–156.1).

The cestrum was a hard wax–working tool used cold. It was similar to an engraver, and its known purpose was to incise lines on ivory. The cauterium was a hard wax–working tool said to have the appearance of a metal spoon or hollowed-out spatula. It was hot after being heated over coals. These two tools are believed to have been used to create the heavily textured, almost sculptural impasto surfaces of encaustic paintings. The pencillium was, fundamentally, a brush; both brush marks and hairs seen on the surfaces of portraits confirm its use.

Nevertheless, modern experimentation shows that all the characteristic marks seen on encaustic paintings can be made with just a brush, particularly if the wax is allowed to harden on the bristles, creating a stiff tool.

Evidence of toolmarks and paint handling

As in other paintings identified as wax-tempera, the appearance of the paint layer in this portrait is considerably matte with little impasto. The painter’s hand can be seen most directly in the use of tratteggio around the eyes and the bridge of the nose (fig. 4.19).

Wide sections of fine parallel lines in the background are evidence of brushstrokes, which are oriented vertically in most of the panel (fig. 4.30) but at the top appear to follow its curve (fig. 4.18). Such marks indicate that the background areas were applied liberally in broad strokes with a wide, flat brush.

Where visible texture is intact, the impasto is delicate but nonetheless legible in raking light (fig. 10.41).

The gilding served to protect the paint layer below, preserving the toolmarks more comprehensively and with greater detail than in ungilded areas. The [glossary:denoising] effect of the gilding makes it possible to appreciate both the gestural quality of some of the more textured areas (fig. 4.1), with their characteristic zigzag lines, and the uniformity and regularity of the brushstrokes of the background (fig. 8.36).

To render the hair, the artist first applied a uniform midblack wash and then painted individual strands and curls.

The artist left no marks or signatures.

Additional Materials

Textile

Considerable remains of mummy wrappings are visible around the outer margins of the panel and cover about one-quarter of the bottom. Vestiges of wrappings also appear along the proper left side.

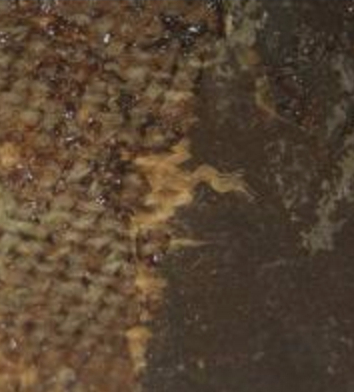

The textile remnants are likely linen, the fabric commonly associated with Egyptian funerary practices. Under magnification, linen exhibits a distinctive S-twist, and [glossary:stereomicroscopic] examination of a segment of these wrappings confirms this orientation (fig. 4.3). To the naked eye, the fabric appears to be raw, undyed linen.

The cloth appears to have at least two layers, and both seem to display an equally fine weave (fig. 8.37). It is not possible to determine how many layers of cloth the mummy was wrapped in.

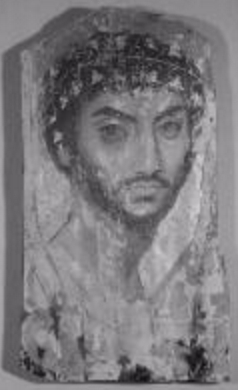

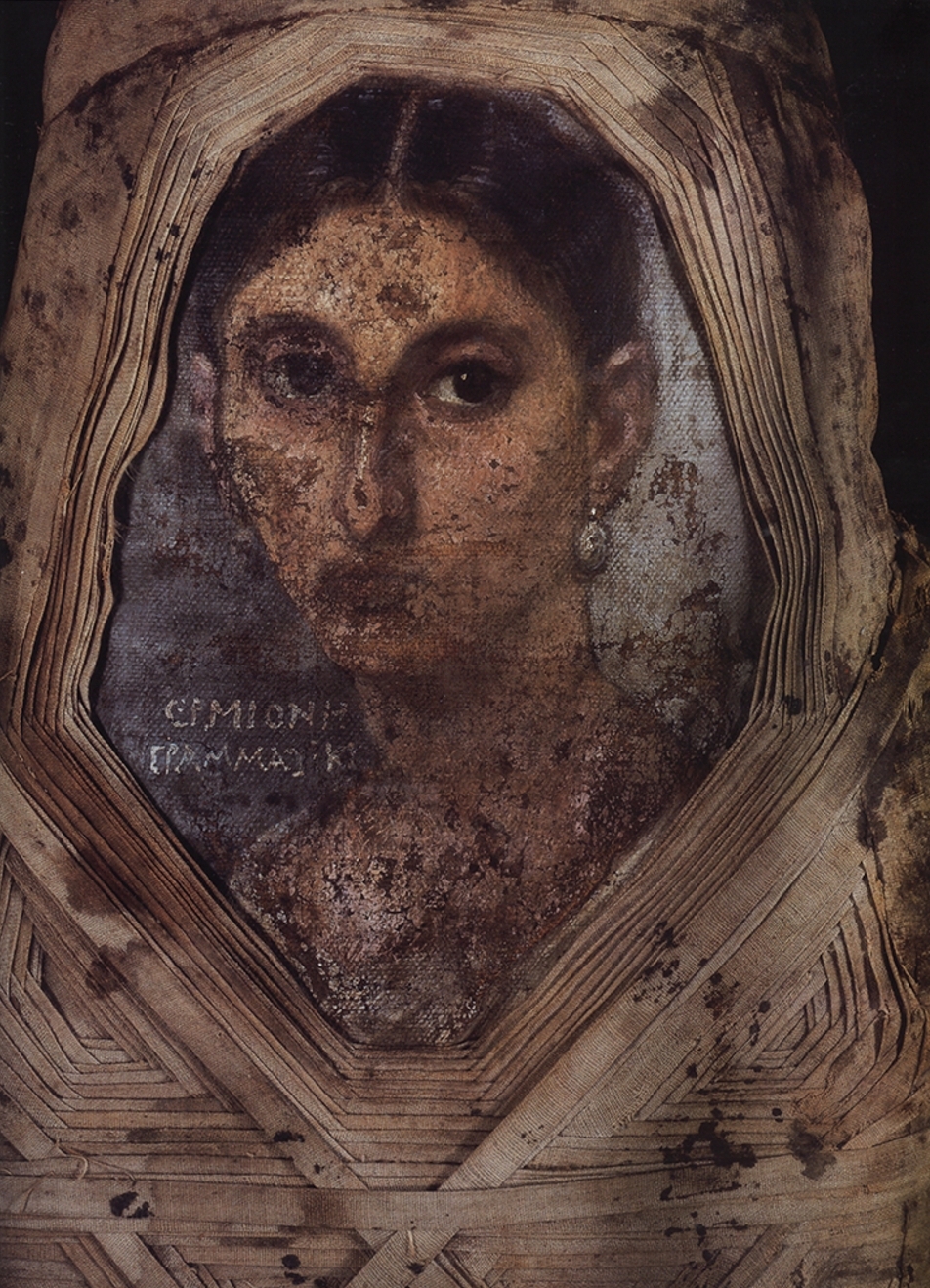

Based on the pattern of the still adhered remains, the fabric was originally placed across the shoulders in steeply plunging diagonal lines. These strips might have intersected at the center of the chest, as on a red-shroud mummy in Hildesheim (fig. 4.4). The vast majority of red-shroud mummies, however, display an ovoid opening around the portrait, such as that of the mummy of Herakleides (fig. 4.5). More probably, given the horizontal direction of the cloth between the bottom ends of the diagonals, the lower wrappings were arranged in an angular shape, resembling an upside-down trapezoid, in this case a quite acute, pinched one, similar perhaps to that of the celebrated Hermione Grammatike (fig. 8.38). The angular, rather than curved, base of the opening places the portrait within a subgroup of Roman mummies with rhomboid-wrapped body fields. These are characterized by plentiful strips of linen wrapped and arranged in overlapping patterns of diagonal squares. The tops of the portraits in this subgroup were usually wrapped with the textile folded over onto itself to follow the arch at the top of the portrait, thus creating an ovoid window, as seen on a fine example in Boston (fig. 4.2), although angular wrappings at the tops of the portraits are also attested. On the Chicago mummy portrait, this turnover is indeed visible on the proper left side (fig. 8.39).

The wrappings cover some of the decorative embellishment along the neckline, and vestiges of an unidentified material, clearly associated with the funerary preparations, extend far into the neck (fig. 4.6) and even into the face (fig. 4.7). This extension of material, along with other isolated and accreted patches of textile, notably on the proper left eye (fig. 4.8), may have adhered in dislocated places after becoming dislodged, perhaps during excavation or conservation.

The weave on the wrappings was placed diagonally to the grain of the wood.

Heavy deposits of carbon black pigment appear on the surface of the wrappings along the bottom edge of the portrait, raising the possibility that the linen was part of a painted shroud that encased the mummy wrappings.

Adhesions of a different nature can be seen along the top edge of the portrait, but they overlie one of the metal tacks securing the portrait to its cradle, so they cannot be ancient.

Traces of paint at the furthest edges of the panel indicate that the panel was originally painted in its entirety. The paint in sections that were once in contact with the wrappings, particularly at the bottom, was obliterated when the portrait was removed from the mummy upon excavation.

Resinous materials

Resinous materials appear as shiny brown deposits both within the wrappings and on bare surfaces of the panel (fig. 4.9). Analysis of samples taken from these areas confirms the presence of natural resin and tar.

Within many areas of accreted resin, the weave of the now-detached or disintegrated textile has been preserved (fig. 10.43).

Gold

Several areas of the painting have been gilded: a wreath of vegetal design, neckline ornamentation in a geometric form (squares set at angles), and the background behind the portrait. The gold used for the decorative details (the wreath and the neckline) is pure while that used on the background is of a lower quality. The varying qualities of the material notwithstanding, the abundant and sophisticated use of gold places the sitter firmly in the upper echelons of society.

The adhesive used to affix the gold had to be sufficiently strong to hold such delicate slivers in place; a protein rather than a gum was likely employed for this purpose.

The placement of the gold illustrates the sequence of events leading up to the final preparation of the mummy. A square patch of linen lies on top of the last leaf of the wreath at the proper left side (fig. 4.10), indicating that the panel was gilded before being inserted into the wrappings. The gilding in this area is quite painstaking and would have been far easier to carry out while the panel was separate from the mummy.

The gilding in the background, which alternately covers and skirts a margin around the hair (fig. 4.21), was applied after the painting was completed but not necessarily before insertion. Along the proper left edge, traces of gold appear on top of the linen (fig. 4.11), demonstrating either that the gilding was done after insertion or that it required touching up after insertion.

In some areas, the gilding was not done with complete precision. On the proper right side, gold was applied over a large portion of the top of the shoulder closest to the neck, altering the profile of the neck and necessitating its articulation with a thick line of black pigment (fig. 4.33). On the proper left side, along the edge of the neck, the gilding covers a section near the base of the throat and exposes a part of the background adjacent to the top of the neck (fig. 10.44). X-ray examination reveals that the artist made no attempt to render the top of the proper left shoulder, and instead covered it entirely with gold (fig. 10.42).

Condition Summary

The object is in reasonable condition with a roughly equal proportion of surface and structural issues. The portrait has disfiguring structural problems, but they do not diminish its aesthetic and emotional impact.

Like most mummy portraits, the painting exhibits prominent splitting and cracking along the vertical axis. These cracks are the result of the inherent instability of the thinly planed wood and varying environmental conditions, sometimes in combination with the prolonged pressure from the wrappings. Numerous small, shallow splits are visible along the top and bottom edges of the panel, in the center, and on the proper right side of the face. A network of deeper cracks extends through the proper right side of the face, bisecting the pupil of the eye; these cracks are stepped and nearly overlap (fig. 4.12). Little active movement is associated with these cracks. On the proper left side, however, a noticeable crack extends from the bottom of the panel through the gilt field to a point level with the proper left ear. Significant deformation and warping is seen along this plane of [glossary:cleavage], exposing the full thickness of the panel along the fault line (fig. 4.13). This split displays a considerable degree of active movement, causing the adjacent paint films to flex and lift.

The exposed wood on the [glossary:rip-cut] edges of the panel at left and right appears compact and sound. The exposed wood on the [glossary:crosscut] edges of the panel at top and bottom is fibrous and soft with associated splintering and minor losses. The panel is largely free of insect damage, with only one or two areas of [glossary:exit holes] visible on the bottom edge.

The paint layer appears embrittled and prone to cleavage, which has resulted in extensive losses. Patterns of [glossary:craquelure] here are consistent with those observed on other mummy portraits. Three types of cracks can be seen: one running diagonal to the grain, producing irregular quadrangles (fig. 15.48); another following the grain, producing frayed or jagged cracks and losses (fig. 4.14); and a third seemingly unrelated to grain direction, producing regular quadrangles (fig. 4.15).

A bloom can be seen in the flesh tones at the center of the face, particularly on the proper right cheek (fig. 4.16). Blooms are common to mummy portraits and are thought to be related to the degradation-linked migration of organic components from the beeswax.

A large area of paint on the front of the throat is exceptionally dark, a discoloration that could be caused by exudates from the corpse. Similarly, a dark-brown deposit is visible in the upper portion of the crack running through the proper right eye. This may also be the result of an exudate, or it may be a displaced section of wrapping, the adhesive from which remained affixed to the area.

The largest patch of linen at the bottom edge shows active movement.

Fibers of cotton wool, perhaps from a previous cleaning, are ensnared in the texture of the paint in multiple areas across the surface.

Small accretions and adhered soil appear throughout (fig. 4.17).

Cracks along the join between the wood and the support signal the presence of tension across the panel. This tension is explained by the use of tacks to hold the panel in position, which causes dimensional instability to be released not around the margins but across the center and results in considerable damage, as evidenced by the split discussed above in para. 63. As is often true of mummy portraits, the mounting method has exacerbated the portrait’s instabilities.

Conservation History

Most mummy portraits have received some kind of conservation treatment. Many of the portraits discovered by Petrie, for example, were impregnated with paraffin wax, which has become the source of numerous problems. No paraffin wax was detected during analysis, indicating that the portrait was spared this treatment.

The surface was at some point consolidated with cellulose nitrate, a treatment that has its own drawbacks. The portrait’s conservation treatment cannot be considered a success: in many places, fragments of paint are adhered to the surface with no relationship to their original position, and they are often adhered to the surface upside down (fig. 15.46). Continued lifting of the paint film signals either that the consolidation was poorly executed or that the material has reached the end of its useful life.

The panel appears to have received very little retouching.

The first documented treatment, carried out in April 1978, states that “cleavages” appear to have been consolidated with an extremely dilute, unspecified [glossary:size]. The conservation report does not specify whether these cleavages are the splits in the panel or active and incipient losses in the paint films themselves, but the very low concentration of the [glossary:consolidant] used suggests the latter.

Documentation also exists from 1982 and 1992, but it is not clear whether it refers to examinations or interventions.

Rachel C. Sabino