Two portraits of young men from ancient Roman Egypt were given to the Art Institute in 1922. Painted using the [glossary:encaustic] technique, their vivid likenesses are rare survivals of the classical Greek and Roman art of [glossary:panel] painting. The portraits belong to a group called mummy portraits, or Fayum portraits, because most were found in the Roman-period cemeteries of the Fayum Oasis southwest of Cairo, attached to the mummified bodies of the dead. Although damaged by centuries of burial and presumably also by removal from their mummies when found, the portraits are important as images of individuals and as works of art that fuse the millennia-old funerary traditions of pharaonic Egypt with the representational art of Greece and Rome.

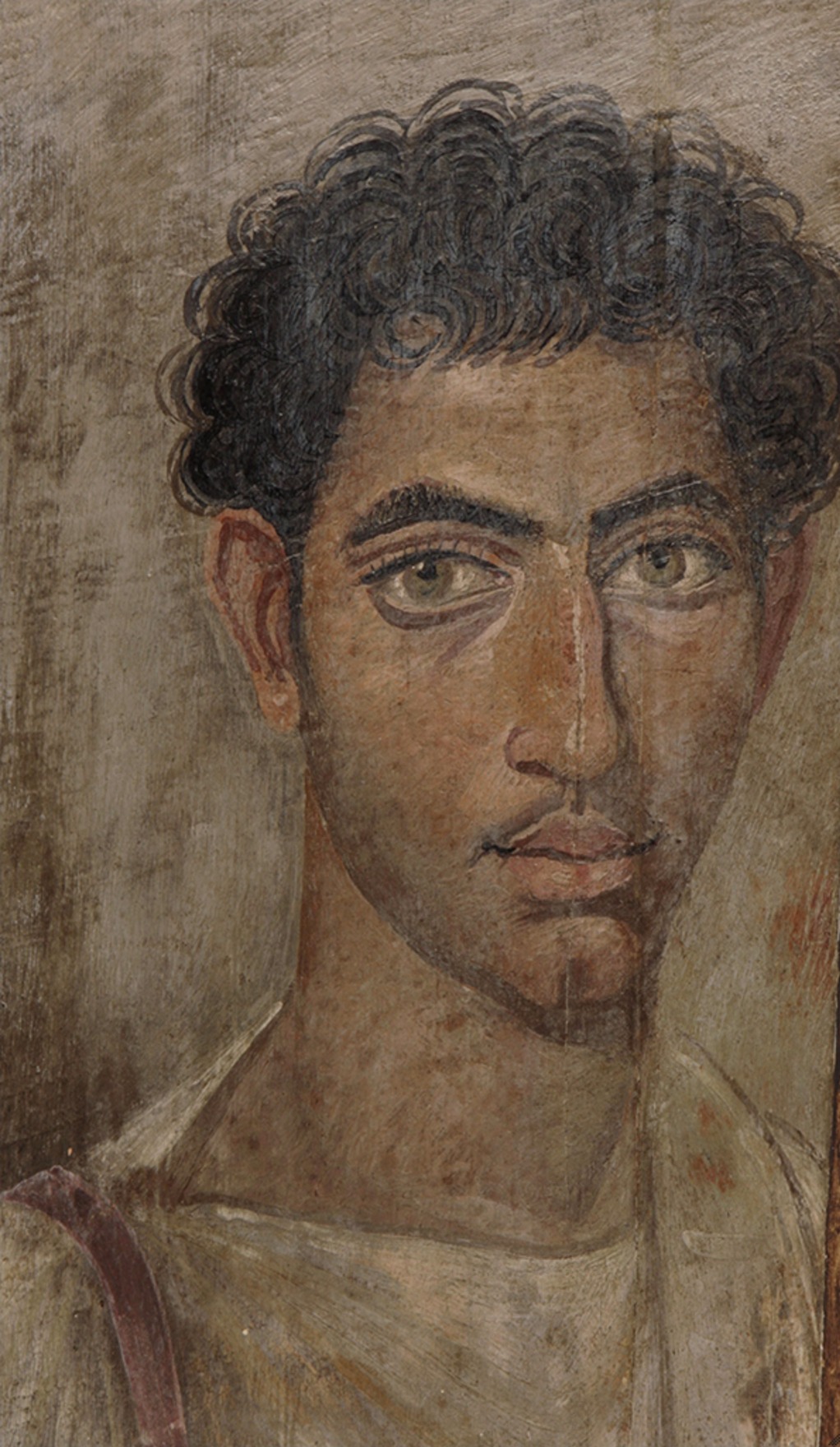

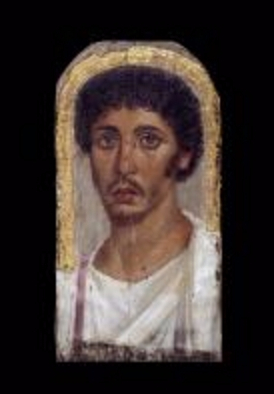

The three-quarter poses of the portraits give an illusion of movement and informality as the men turn to face the viewer. Their eyes gleam as they make contact, and their ruddy lips seem about to part and speak. They wear their best clothes—a white [glossary:tunic] with a dark reddish-purple [glossary:clavus] visible on the right shoulder and a white [glossary:toga]-like mantle draped over the left shoulder—formal dress for a banquet or for civic or religious duties. The thick, curly hair; arched eyebrows; and light beards mark them as young adults. They are members of the rich, educated, upper class—landowners, administrative officials. They may have been Roman citizens.

Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath (cat. 155) shows a thin face, pointed chin, and high cheekbones. Expressive eyebrows arch above elegantly curved and thickly lashed dark brown eyes. Wiry curls of hair cover his head. A short beard clings to the line of his chin, and a thin moustache smudges his upper lip. His curved lips are smooth, pink, and full. The impression is of an intense personality, focused on the painter and viewer.

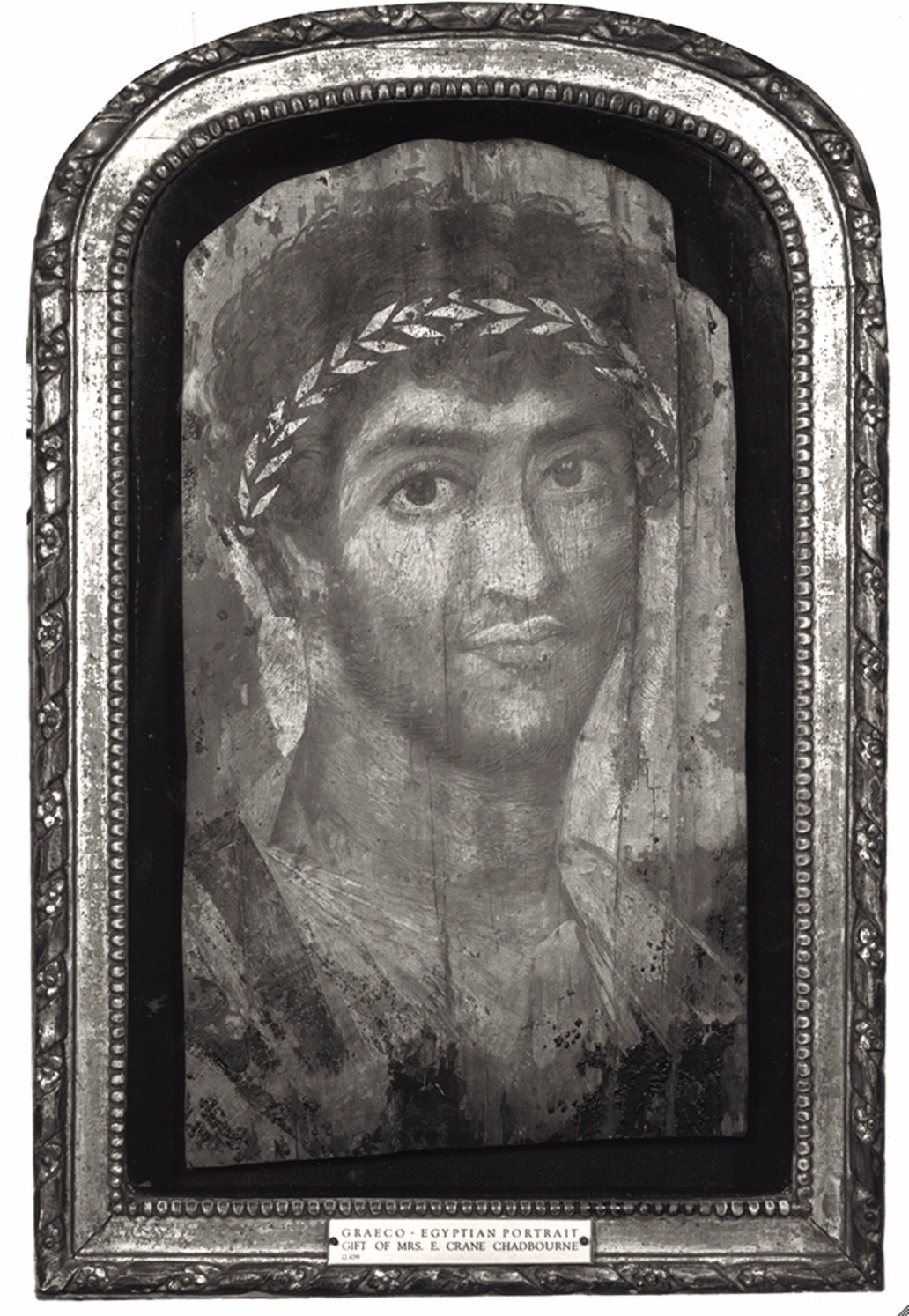

The face of Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing a Laurel Wreath (cat. 156) is broad, with a rounded chin. The eyes are lighter brown, set under thick eyebrows that almost form a bar above the bridge of the nose. Soft, feathery curls of hair form a dark halo, with three thick curls drooping over the center of the forehead. The short beard is so light and downy that it blurs the line of the chin, emphasizing the illusion of youth and a gentle, dreamy temperament. As described in the technical report, the center of this portrait is difficult to appreciate because of losses—particularly to the cheeks, nose, lips, and chin—as well as because earlier efforts to consolidate and retouch the surface are no longer stable.

The wood panels were trimmed to fit on top of the linen wrappings of a mummy and were bound with resin and linen strips above the face of the mummified corpse of the owner. Over time the panels warped, and both panels now have a convex profile that thrusts forehead, nose, and cheeks toward the viewer. They display both surface and structural damage, including losses to the paint layer and the gold leaf as well as splitting of the panels themselves. Some of this damage is a result of the portraits’ having been removed from their mummies, exposing traces of the original background paint in the process. Remains of textiles and resin are visible on both portraits.

Painting the Art Institute Portraits

The first step in painting a portrait was the preparation of a thin panel of wood large enough for a life-size head. Like most panels used for mummy portraits, the Art Institute’s are of lime (linden) wood (Tilia sp.), probably imported from Europe. The panels were likely sized, most probably with protein (egg or gelatin) or gum, but it is extremely difficult to determine the presence of a [glossary:sizing] layer by analytical means. Grounds were generally applied prior to painting Fayum portraits. In the case of the Art Institute’s portraits, analysis has demonstrated that a [glossary:ground] of lead white appears to have been used. Apart from the analysis, where paint losses expose the surface, chalky white dust—remains of the thin coating of lead white—is visible.

Underdrawings or preparatory sketches are often noted on the portraits, and the two Art Institute portraits are no exception. On Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath the underdrawing was done in black; the underdrawing on Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing a Laurel Wreath was done in a dark-brown wash.

Both portraits were painted using the encaustic technique. The method was first used by Greek painters during the fifth century B.C. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History lists masterpieces by encaustic painters of the past. In comparison with these famous paintings, mummy portraits must have been the work of modest artists. Called zographoi (literally, “he who paints life”) or enkaustai (painters, literally “burners in”) or technitai (people who practice a techne, or skill), some painters may have traveled from place to place. Others probably found enough work to live comfortably in a town or city. A late papyrus from Oxyrhynchos authorizes payment in kind to a painter: “Zoilos to Agathodaimon, estate-steward, greetings. Deliver to Herakleides, painter, as payment for a picture one artaba of wheat [0.8 bushel, worth about 65 silver drachmae at the time], and two Knidian jars of wine only. Year 38, Tybi 23.”

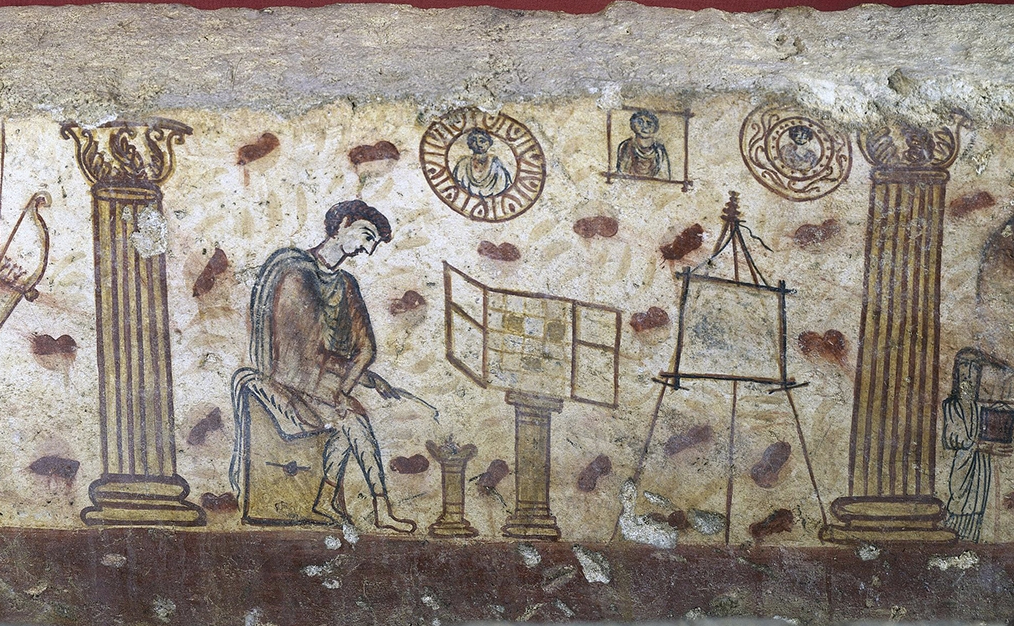

A remarkable painting survives on the interior of a first-century A.D. [glossary:sarcophagus] found at Kerch (ancient Panticapaeum) in Crimea. It shows a painter at work in a colonnaded space (his studio?), warming a tool over a brazier as he works on a painting resting on an easel (fig. 155–156.1). The box in the center with many compartments and cover flaps holds raw and ground [glossary:pigments] and other materials. On the wall hang three completed portraits, one in a simple square frame, the other two mounted as shield portraits, clipeatae imagines—a deliberate presentation of the subjects, whether living or deceased, as godlike. A contemporary writer was impressed with the skill and speed of encaustic painters: “The painter chooses with great speed between his colors, which he has placed in front of him in great quantity and variety of hues, in order to portray faithfully the naturalness of a scene, and he goes backwards and forwards with the eyes and with the hands between the waxes and the picture.”

The encaustic medium employs powdered mineral or organic pigments mixed with molten beeswax—a challenging technique. The paint could be applied either hot or cold. Hot paint was applied quickly with long, smooth brushstrokes. As the wax cooled, a hard tool was used to blend and even carve the skin tones of face and neck. To apply the wax cold, modification with an alkaline substance, a process known as saponification, was required; the result of this treatment is called Punic wax. No evidence supporting the use of Punic wax was found on either of the Art Institute portraits, but it is admittedly challenging to identify this material by analytical means. Most frequently, Fayum portraits display a thin layer of paint applied with a wide, flat brush for the background and for large areas of clothing, while a thicker, paste-like mixture was used for the face and hair to create a luminous, almost sculptural, textured surface. This approach is certainly appreciable on Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing a Laurel Wreath.

It used to be thought that mummy portraits were painted using two mutually exclusive techniques—[glossary:tempera] or encaustic. Recent examination of large numbers of mummy portraits has revealed a more nuanced picture: many portraits that visibly resemble tempera paintings demonstrate the presence of beeswax on analysis, indicating perhaps the use of a combined technique. The term wax-tempera is being proposed as a classification for such portraits. Indeed, Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath is one such example.

Analysis of the Art Institute paintings revealed the use of only four basic pigments: black, red, yellow, and white. This four-color palette corresponds to the ancient Greek system called tetrachromatikon.

The Art Institute’s two portraits were painted by different artists. On Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath, the hand of the painter can be seen most clearly around the eyes, where delicate [glossary:crosshatching] in subtle tints models the nose and orbits of the eyes, and deeper red strokes outline the eyes. The red curves of the lips are emphasized by the thin wash of black that outlines the shape of the moustache and the quick, irregular lines that define moustache hairs and tiny nest of beard under the lips. Short, thick strokes of paint define eyelashes and brows. A thin white line traces the line of the nose, uniting the bright highlights of eyes and lips. By contrast, the eyes of Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing a Laurel Wreath are strong evidence of the work of a different painter—layers of short strokes of [glossary:impasto] swirl and abut each other to create the gaze. The brows are soft and feathery. A large, pale area of damage centered on the nose and mouth lessens the impact of the portrait, but long, smooth brushstrokes shape the muscles of the powerful neck.

The final ornament added to both portraits was gold leaf for the wreaths and background, probably after the panels were attached to the mummy, because the gold was not concealed under the final layer of wrappings intricately interwoven to frame the faces and in some instances was superimposed on the wrappings. This makes sense because gold was expensive, a perquisite of the elite. Six squares of gold leaf can be seen along the base of the man’s neck of Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath; it is possible that this line of squares continued along the edge of the lost linen wrappings that framed the portrait, as this type of ornament survives on several intact mummies.

In ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt, wreaths of leaves and flowers were worn on many occasions—participation in a religious ritual, victory in an athletic contest or military campaign, and dining at a banquet, as well as elevation after death to the realm of the immortals. A laurel wreath formed of rhombic-shaped bits of gold leaf was applied over the hair of Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing a Laurel Wreath. The thin, curved lines of the wreath of ivy leaves and berries worn in Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath is unique among surviving mummy portraits. The ivy crown was the attribute of the god Dionysos, worshipped as Bacchus by the Romans and identified with the Egyptian Osiris, god of the dead and rebirth. It might have been added to the portrait in life as a symbol of initiation.

Date

Examples of Fayum portraits toured Europe and America at the end of the nineteenth century in an exhibition arranged by Theodor Graf (1840–1903), one of the first dealers to collect antiquities from Egypt’s Roman, Byzantine, and early Islamic periods. Graf optimistically touted them as products of the Ptolemaic dynasty, arguing that only Greek painters were skilled enough to have made them and that the few associated names and inscriptions were all in Greek. The renowned Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie (1853–1942) and other archaeologists quickly pointed out that finds associated with the portraits must date to the Roman period, including tombstones, papyri, and mummy tags, noting that the elite of the multicultural society of Egypt spoke Greek. It is now clear that the portraits were first painted in the early first century A.D. and continued for more than three hundred years.

Within these three centuries, the portraits can be dated using two methods. First, portraits of the first century A.D. often share the skillful technique, delicate details, and naturalism that compare well with the finest mural painting that survives in Rome and in the cities buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. Second, the rapidly changing fashionable hairstyles worn by the men and women of the imperial families that ruled Rome were copied throughout the empire, even in the faraway province of Egypt; these are well known, thanks to coin portraits and sculptures.

The Art Institute’s two portraits were probably painted in the first or second quarter of the second century A.D., when men throughout the Roman Empire began to wear beards with greater frequency. The strength of the new fashion is closely associated with the emperor Hadrian (r. 117–38) and his fondness for Greek culture and philosophy.

Mummy portraits of two other young men are good comparisons that bracket the time when the Art Institute’s portraits were painted. Both were excavated by Petrie during his 1887/88 season at Hawara. The portrait of a young man with a long face and cleft chin (fig. 155–156.2) was painted on a panel that was neither trimmed nor bent to attach to a mummy; the unpainted strips along the sides suggest it was displayed in a frame. It may have been found in one of the tombs. The smooth-shaven face indicates that it was painted in the late first or early second century, before beards became the fashion; the delicate crosshatching and the treatment of the eyes suggest a relationship with the painter or workshop of Mummy Portrait of a Man Wearing an Ivy Wreath. The second portrait shows a young man (fig. 155–156.3) with a slight resemblance to the emperor Lucius Verus (r. A.D. 161–69). The sketchier painting with fewer, thick strokes of paint and the gilded stucco frame also suggest a date toward the middle years of the second century.

Mummy Portraits and Romano-Egyptian Society

Portraits were vitally important to both Egyptian and Roman society, but in different ways. To the Romans, portraits—including images made for tombs and sarcophagi—were not cult objects. They were important as a reminder to the family and its children of the personal virtues and career successes of the deceased. In the Roman Republic, portrait likenesses of ancestors—painted, bronze, marble, wax—were displayed in the homes of important families and carried in funeral processions, sometimes “worn” by actors dressed as if the men and women were still alive. Pliny the Elder claimed that the tradition was falling into disuse, but the thousands of Roman portraits that survive suggest otherwise and that the custom spread into the growing classes of merchants and [glossary:freedmen]: “Correct portraits of individuals were formerly transmitted to future ages by painting; but this has now completely fallen into desuetude. . . . It is my opinion, that nothing can be a greater proof of having achieved success in life, than a lasting desire on the part of one’s fellow-men, to know what one’s features were.”

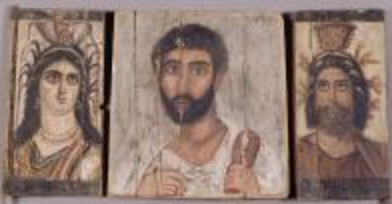

Portraits were also made for the pleasure of family and friends or lovers, “the object of decoration, then, being not piety to the dead but pleasure to the living.” A rare example is illustrated on a mosaic from the House of the Man of Letters at Daphne, the suburb of Antioch-on-the-Orontes (fig. 155–156.4). It shows a man reclining on a bed and gazing at a framed portrait in his hand. A similar mosaic from nearby Alexandria ad Issum (modern-day Iskenderun) is labeled with the name Ninus, which identifies the man as the Assyrian king, who is the protagonist in love with his cousin Semiramis in a novel written in the second century B.C. but still popular in Roman times. Petrie excavated a small-scale, framed portrait at Hawara (fig. 155–156.5) that seems to have been deliberately left as a gift beside a mummy. A handful of other framed portraits are known, including a triptych with a portrait of a man flanked by images of the gods Isis and Serapis (fig. 155–156.6).

Unlike contemporaries elsewhere in the empire, the people who lived in Roman Egypt continued to believe that rebirth into the afterlife depended on preservation of the body (mummification), although an image of the deceased or the name of the deceased could also serve as a substitute. The face of the deceased was a divine or magical image, because through mummification and rituals he was united with the god Osiris. Royal “portraits” could be of precious metal, as is well known from the surviving gold masks of the Dynasty 18 pharaoh Tutankhamun and the Dynasty 21 pharaoh Psusennes I. Carved and painted portraits of scribes—the administrators who ran the government, estates, and temples for the pharaohs and for their Ptolemaic and Roman successors—have been found not only in tombs but also in temple precincts, with inscriptions offering perpetual prayers and offerings to the gods. Painted panel portraits for mummies first appear about the same time that private portrait statues ceased to be made for Egyptian temples, and written sources prove that painted portraits were hung in public places such as temples. Modeled and painted masks of wood, plaster, linen, and cartonnage (fig. 155–156.7) were attached to the coffins and mummies of important but less exalted Egyptians through the centuries of rule by the Ptolemaic Greek kings and the Roman emperors. In the 1990s, dozens of Graeco-Roman richly painted and gilded mummies were found in tombs at the Bahariah Oasis in the Western Desert.

No ancient texts about Romano-Egyptian portrait mummies survive—although a number of papyri mention painters, painting materials, and mummification. Portraits may have been commissioned in life. The mummy wrappings attaching some panels concealed painted borders and evidence of old wear or damage, so they may have originally been hung elsewhere. Petrie observed that none of the portraits found on mummies had been painted on panels that were precut to the required shape. Most portraits represent young or mature adults—few children or seniors—and Petrie and other scholars noticed that the portraits sometimes do not match the age of the deceased, as the face of a young man or woman was found attached to the mummified remains of an older person. Petrie also recorded that several of the mummies excavated at Hawara “had been much injured by exposure during a long period before burial . . . knocked about, the stucco chipped off . . . dirtied, fly-marked, caked with dust which was bound on by rain” while on the foot cases of some “the wrappings had been used by children who scribbled caricatures upon it.” He was puzzled that many of the mummies had not been carefully buried in tombs but stuffed carelessly, sometimes in pieces, into disused tomb shafts or pits dug in the desert sand, and conjectured that these were reburials.

Only one or two in one hundred mummies excavated at Hawara had portrait panels inserted in the wrappings. Petrie hypothesized that these are the bodies of the elite. In recent years, mummies with painted portraits have been excavated at Aswan, Thebes, El-Hibeh, Fag el-Hamus, Sheikh Abada, Akhmim, Antinoopolis, Tanis, and Marina al-Alamein, proving that portraits were part of Romano-Egyptian funerary practice in places other than the towns of the Fayum. The new tradition may not have been common throughout the Roman province of Egypt—but it was clearly meaningful to at least some families of the upper classes. Greek and Roman writers who toured Egypt wrote with astonishment of the Egyptian habit of “dining with the dead.” Commemorating ancestors in family funeral processions and at family tombs was a tradition in Rome, but the Egyptian ritual of ancestor cult in the presence of the embalmed bodies seemed shocking to travelers accustomed to cremating their dead. However, veneration of the deceased had a millennia-long history in Egypt; architectural evidence includes tomb chapels and garden courtyards where large-scale painted or sculpted portraits of the dead became part of the regular festivals and banquets and where the family left letters to the dead as well as baskets and pottery as banquet supplies.

It has been suggested that painted panel portraits were carried in the funerary procession (a ritual called in Greek the ekphora) that escorted the corpse from the home, through the town, and by boat or donkey to the village of the embalmers. Only at the close of the long rituals of mummification would such a portrait receive costly gold ornament and be trimmed to insert in the wrappings.

Hawara: The Necropolis of Arsinoe

It is not known where the Art Institute’s portraits were found in Egypt, but some hypotheses can be put forth based on observation. The sides of both portraits were cut away, perhaps substantially if the original shape was a square, and the tops were trimmed to an arched shape. This curved top has been identified as characteristic of the work of the embalmers at Hawara, the cemetery of the nome capital, Arsinoe. A similar shape is also known on some panels found at er-Rubayat and Kerke, the necropoles of Philadelphia in the Fayum, and at Antinoopolis, hundreds of miles up the Nile.

Petrie came to Hawara in Egypt’s Fayum region for the 1887/88 excavation season in order to explore the ancient Labyrinth, the huge mortuary temple attached to the pyramid of the Dynasty 12 pharaoh Amenemhat III. Petrie’s first trenches uncovered a sprawling cemetery of Roman date. He was about to shift work to another spot when the first panel portrait was found, still attached to its mummy: “a beautifully drawn head of a girl, in soft grey tints, entirely classical in its style and mode,” and he later wrote “though I came for the pyramid, I soon found a mine of interest in the portraits on the mummies.”

Petrie was one of the first archaeologists to record the circumstances of his finds, so his observations about the locations and condition of the eighty-one portraits found during the 1887/88 and 1888/89 seasons and the sixty-five found when he returned to Hawara in 1910/11 still provide the fullest information known about a large number of portraits. Petrie realized that Hawara was the cemetery of Arsinoe, which lies about six miles to the northwest. It was also the “place of purification,” both workplace and home of the mortuary workers—embalmers and priests, but also gravediggers, tomb builders, and possibly painters.

The Fayum, about one hundred miles up the Nile from the Mediterranean, is a low-lying basin centered on Lake Moeris. During the third century B.C. the Ptolemaic kings organized the building of canals in order to provide soldiers and civilian immigrants with new, fertile land. The settlers were mostly Greeks, but intermarriage and time created a prosperous, multicultural society. The towns and villages were recolonized by Roman army veterans after Augustus conquered Egypt in 29 B.C. Greek remained the primary language, suggesting that the new citizens were also from the Greek-speaking eastern areas of the empire. During the Roman period (29 B.C.–A.D. 642)—the centuries that produced the hybrid of Egyptian mummification, Greek inscriptions, and Roman portraits—the privileged Greek-speaking citizens of the Fayum perceived themselves as simultaneously Roman, Greek, and Egyptian, a cosmopolitan identity that was not unusual in other Greek regions of the empire.

In the later second century, after generations of peace and prosperity, the Roman Empire began to suffer from a series of border invasions, plagues, natural disasters, and civil wars. Egypt was hurt disproportionately as the breadbasket of the empire, burdened by old and new taxes. The misery was reflected in falling population, fewer and poorer quality mummies, and a decline in the number and excellence of portraits. The people who lived in the Fayum, farmers and townsmen, were rich, but they paid the highest taxes in Egypt. Social, political, and military woes led to mass emigration to avoid taxes—and depopulation meant that the complex system of canals that made the Fayum fertile began to collapse. Throughout the fourth century, towns like Karanis, Philadelphia, and Bacchias were gradually abandoned to the desert. When in 391–92 the Christian emperor Theodosius I banned pagan sacrifices, prohibited divination, and ordered the destruction of temples, he may also have prohibited mummification, ending the tradition of painted mummy portraits.

The Discovery and Collecting of Fayum Portraits

Close to a thousand mummy portraits are known, about 150 in North America. With a handful of exceptions, the portraits were found—a few in controlled excavations like Petrie’s but mostly by grave robbers—in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the 1880s, Bedouin mining in the hills of the Fayum for sebakh (decomposed ancient mud brick used as fertilizer) found mummies with panel portraits inserted in the wrappings. Already known as an eager purchaser of old textiles, Theodor Graf bought any and all of the portraits brought to him. A canny businessman, Graf displayed the panels in an exhibition that traveled around Europe and then to New York and to the 1893 Columbian Exposition and World’s Fair at Chicago. In the years between 1887 and his death in 1903, Graf handled more than 350 portraits—at least a third of the known examples. Petrie also rushed to display his new treasures from Hawara a few months after their discovery (fig. 155–156.8). The excitement generated by the mummy portraits meant that most were snapped up by museums and collectors, some of them willing to pay dearly for seriously warped examples or pastiches.

Most mummy portraits are now in museums, and on the rare occasion that a well-preserved, high-quality portrait with sound ownership history enters the art market, it can attract much attention and high prices. Most portraits were separated from their mummies by the finders, usually because the mummies were damaged or poorly preserved, but also because it is easier to transport a small panel than a body. In the enthusiasm that greeted the discovery of painted portraits, illegal diggers and archaeologists alike ripped them out of the wrappings.

Study of mummy portraits was hampered for a long time because Egyptologists ignored them as late creations of the Roman period, classical archaeologists dismissed them as Egyptian, and art historians regarded them as curiosities that could provide only minor information about ancient hairstyles, jewelry, and clothing. Fortunately, a few experts became fascinated, notably Klaus Parlasca of the Archäologisches Institut der Universität Erlangen, who compiled images and descriptions to publish a four-volume catalogue of all the portraits he could locate. More recently, interdisciplinary work by research scientists, conservators, museum curators, and archaeologists has begun to weave new facts into an appreciation of the portraits in the context of the far-flung Roman Empire.

Collecting Note

The Art Institute’s two portraits were gifts in 1922 from Emily Crane Chadbourne (1871–1964). Mrs. Chadbourne was a daughter of Richard Teller Crane, who built the hugely successful Crane Co. pipe and plumbing company (now part of American Standard Brands). As a young woman moving in elite Chicago circles, Emily Crane undoubtedly frequented the 1893 Columbian Exposition and Chicago World’s Fair, where one of the many exhibits was Graf’s display of seventy-five “Greek portrait panels found in the Fayum.” After divorcing her husband, attorney Thomas Lincoln Chadbourne, in 1905, Emily moved to Europe, where she became part of the avant-garde art circles of Paris and London and a friend to famous collectors Gertrud Stein and Isabella Stewart Gardner and to art historians/archaeologists Matthew Stewart Prichard and Thomas Whittemore. There is no proof, but the two portraits might have been acquired as early as 1908, when she was furnishing her London and Paris homes. In May 1922 the Chicago Tribune reported that Mrs. Chadbourne “had given the furnishings of her Paris apartment to the Chicago Art Institute. For years she has been devoting herself to making what is now a choice and unusual collection of rare and beautiful things for this apartment. She is a real connoisseur, one of the class who has had time, money, and a cultivated taste to bring to her hobby.”

When accessioned by the Art Institute, the portraits had matching carved and gilded wood frames (fig. 155–156.9 and fig. 155–156.10), which have since been removed. The frames could have been added by the dealer or by Emily Chadbourne. The small metal labels attached to the frames describe each painting as a “Graeco-Egyptian Portrait,” indicating that Mrs. Chadbourne or the Art Institute staff thought at the time that Fayum portraits were not Roman in date but Ptolemaic Greek.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s two portraits have been together for nearly a century. The portraits show the men young and vigorous, their images adorned with wreaths and gilding by grieving family members. They were painted at about the same time, by different artists, using similar techniques and following the fashionable styles of the time, so it is tempting to wonder if the men knew each other in life. Without archaeological context, we can only speculate.

Naturalistic portrait painting declined in Egypt after about A.D. 300, perhaps hurried by the disapproval of the increasingly powerful Christian church. But portraits and painting techniques were not forgotten. The new tradition of “Byzantine” icons of saints began no later than the fifth or sixth century A.D., the date of three encaustic icons that survive in the monastery of Saint Catherine in Mount Sinai, and continues today in the orthodox religious paintings in Greece, Russia, and other nations.

Sandra E. Knudsen, with contributions by Rachel C. Sabino

Selected References

Thomas George Allen, A Handbook of the Egyptian Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 1923), pp. 160–62 (ill.).

Eugen Fischer and Gerhard Kittel, Das antike Weltjudentum, Forschungen zur Judenfrage 7 (Hanseatisch, 1943), p. 150–51, fig. 138 (1922.4799).

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Greek and Roman Portraits in North American Collections Open to the Public: A Survey of Important Monumental Likenesses in Marble and Bronze Which Have Not Been Published Extensively,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 108, 2 (1964), p. 103.

Klaus Parlasca, Mumienporträts und verwandte Denkmäler (Steiner, 1966), pp. 42, 176n.

David L. Thompson, “Four ‘Fayum’ Portraits in the Getty Museum,” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 2 (1975), p. 92.

Klaus Parlasca, Ritratti di mummie, Repertorio d’arte dell’Egitto greco-romano, series B, ed. A. Adriani (L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1977), vol. 2, p. 61, no. 373 (1922.4799), pl. 90, fig. 4; p. 61, no. 374 (1922.4798), pl. 90, fig. 3; vol. 4 (2003), p. 160.

Louise Berge, “Two ‘Fayum’ Portraits,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 72, 6 (Nov.–Dec. 1978), pp. 1–4, cover (ill.) (1922.4798); p. 2 (ill.) (1922.4799).

Emily Teeter, “Egyptian Art,” in “Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 1 (1994), pp. 30–31, cat. 16 (ill.) (1922.4798).

Barbara Borg, Mumienporträts: Chronologie und kultureller Kontext (Zabern, 1996), pp. 92, 102, 107, 122, 186, pl. 24 (1922.4798).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures from the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood, commentaries by Debra N. Mancoff (Art Institute of Chicago, 2000), p. 69 (ill.) (1922.4798).

Karen B. Alexander, “From Plaster to Stone: Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Karen Manchester (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 29, fig. 14 (1922.4799).