Marine scenes were popular decorations on the walls and floors of ancient Roman houses. Some represent the ocean; others depict saltwater or freshwater ponds in which fish were raised as a luxurious fresh food source. This mosaic pavement panel in the Art Institute of Chicago uses small cubes of white and colored stone ([glossary:tesserae]) to represent four fish with a lobster, a scallop-shell clam, and a triton shell. The curving, irregular placement of the tesserae gives the illusion of looking through clear, rippling water.

Top left: triton snail (Charonia variegata)

Top center: gilt-head bream (Sparus aurata)

Top right: scallop (Pecten jacobaeus)

Center: bass (Decentrarchus labrax)

Center right: cod (Trisopterusluscus) or another species of white fish such as whiting (Merlangius merlangus) or pollack (Pollachius virens)

Bottom left: red mullet (Mullus barbatus)

Bottom right: spiny lobster (Palinurus vulgaris)

Mosaicists did not work from live models. Workshops used pattern books that provided a repertory of designs of mythological subjects, animals, scenes of daily life, and geometric patterns. A selection could be made by the patron—probably to complement a colorful program of wall and ceiling decorations—and assembled by a team of craftsmen to fill rooms, corridors, and courtyards. Raising fish in nearby ponds or importing them alive were spectacular forms of conspicuous consumption. Banqueters even found entertainment in observing how a red mullet changed color from purple to red to pale as it died, brought to the dinner table in a glass jar as proof that it was fresh. The general theme of water appears in a large number of floor mosaics from Antioch, echoing the praise of the fourth-century A.D. orator Libanios of the river, springs, and streams of his native city. Images of river and ocean gods, fishermen, and marine animals often appear in or near dining areas, both indoors and outdoors.

Reliance on pattern books helps to explain why marine scenes found far inland or in the mountains usually represent sea creatures, not freshwater fish. However, there are very few identical mosaics, which suggests a high degree of inventiveness in the fabrication of floors. For example, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, owns a large marine mosaic that is dated to the early third century, the same generation as the Art Institute’s mosaic, which was excavated in the courtyard of a house in Seleucia Pieria, the port city of Antioch. It includes three Erotes riding dolphins as they cast their poles into a sea abounding with specimens of twenty-five species of fish (fig. 4.22). The two geometric mosaics found on either side suggest that the complete pavement was the floor of a biclinium, or two-couch dining area.

The House of the Man of Letters

Elite families throughout the Roman Empire enjoyed country villas—homes at the seaside or in the mountains—where they could escape the bustle of city life ([glossary:negotium]) and cultivate a life of peace and leisure activities ([glossary:otium]). Antioch-on-the-Orontes was one of the great cities of the empire, the capital of the province of Syria. The city teemed with an entrepreneurial, diverse, cosmopolitan population of more than 300,000 people. Respite from civic life could be found a few miles away in the mountains near a famous sanctuary of the god Apollo. Named Daphne (“laurel”) for the tree sacred to the god, the suburb was believed to be the place where Apollo pursued the nymph Daphne and, after she rejected him, metamorphosed her into the elegant tree. Daphne (modern-day Harbiye, Turkey) was and is famous for its cool breezes, shady woods, and sparkling rivers and waterfalls. From 1932 until the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the international Committee for the Excavation of Antioch and Its Vicinity, led by Princeton University’s Department of Art and Archaeology, excavated the ancient city of Antioch and its surroundings. More than three hundred mosaic pavements were discovered and salvaged by the expedition.

The Art Institute’s mosaic was excavated in 1936 in a villa at Daphne that was given the name the House of the Man of Letters. The mosaic of marine creatures was one of several panels with different motifs that made up the border of the mosaic pavement of a room that opened onto a garden courtyard. The room’s use is uncertain, but the location and subjects of the mosaics suggest that it may have been a dining room (triclinium) or a large room used for multiple purposes, including dining (oecus). The excavation photograph (fig. 4.23) and plan (fig. 4.35) show the mosaic located next to the entrance to the room. As is often the case, the room’s pavement was composed of multiple panels oriented in different directions to provide images that could be enjoyed from all angles. The floor is dated to the later Severan period, about A.D. 200/30, based in part on the intricate border of acanthus scrolls on a black background that frames the central panel and in part on the chronology developed by the excavators. The findspot close to the surface under a field and the evidence for rebuilding over centuries of occupation make the villa’s plan uncertain, but at least two different building periods were clear to the excavators, because a geometric mosaic dated to the fifth century was laid on top of part of this floor.

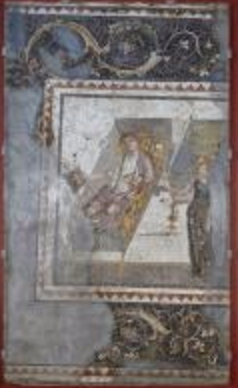

The House of the Man of Letters was named for two mosaic pavements that illustrate characters from popular novels. The mosaic emblema found in the center of the room with the marine mosaic shows a man wearing disheveled garments, reclining on a bed, and gazing at a framed portrait in his hand; a woman approaches him offering a cup of wine (fig. 4.34). A similar mosaic panel from nearby Alexandria ad Issum (modern-day Iskenderun) inscribes the name of the man as Ninus, which identifies him as an Assyrian king, the protagonist in love with his cousin Semiramis in a romantic novel written in the second century B.C. but still read in Roman times. Ninus and Semiramis are also mentioned as characters in pantomime, a popular form of theater that combined music, dance, and song. There is no iconographic connection between the marine subject and the Ninus story; and the workmanship of the marine mosaic is less fine. The framed emblema of Ninus may have been made off site and transported to the villa to be installed as the center of the floor; artisans then completed the pavement to the walls with a series of border patterns. It has been suggested that the marine mosaic panel formed the floor of a small water basin, but there is no evidence of a structure or plumbing to support this.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s marine mosaic was excavated in 1936 in the House of the Man of Letters at Daphne, the garden suburb of Antioch-on-the-Orontes. It formed one small, framed panel of the mosaic border around a larger mosaic pavement centered on a scene from a popular novel. The mosaics were laid about A.D. 200/30 and may have formed the floor of a dining room or large multipurpose room. Although some diagrams and photographs of the ruins were made at the time of discovery, archaeological context has been lost that would today be culled from meticulous study of the architectural remains, associated pottery, and other finds. However, the marine mosaic still provides a tiny souvenir of the life of an elite Roman family. With access to the culture and luxuries of both the city and the Mediterranean Sea, they could escape the heat and activity of busy Antioch and enjoy days filled with the pleasures of reading and banqueting in their home in the cool, watery suburb of Daphne.

Condition Notes

The Art Institute’s mosaic is composed of tesserae cut from white and colored stone. The stones have not been formally identified by analysis but can be presumed to consist of polishable limestones and perhaps marbles. Like many other structures at Daphne, the House of the Man of Letters was brought to the attention of the Princeton expedition’s archaeologists by a farmer, who found its foundations and pavements a few inches below his field. The surviving walls of the house were almost at ground level, exposing the mosaics to the elements. When it was uncovered, the marine mosaic showed various cracks and losses (fig. 8.40) as a result of centuries of household use and renovation, possible earthquake damage, the weight of the earth under which it was buried, and later damage from agricultural tools. No specific record of field treatment survives, but the Princeton expedition’s procedure was to insert cement fills to stabilize damaged areas prior to raising the mosaic. The upper surface was then protected with glued cloth before sawing the mosaic free from the surrounding floor. Tunnels were dug beneath the mosaic bed to facilitate the insertion of wood supports. The pavement was then lifted and turned over onto its face. Layers of exposed, ancient bedding material and mortar were chipped away from the back and new concrete supports were poured and reinforced with the addition of wire mesh and steel bars. Each pavement was then packed in sawdust and mattresses for shipment to its new home. In 2012 the Art Institute’s mosaic was treated in the conservation lab to remove grime and to replace inappropriate and aging repair materials. The expedition’s cement fills were removed and, following comprehensive consolidation of the tesserae, were replaced with a bulked acrylic resin, sculpted and tinted to mimic the missing tesserae.

Sandra E. Knudsen, with contributions by Rachel C. Sabino