These eight mosaic panels depicting a variety of figural subjects were once part of a much larger pavement in a well-appointed Roman home. Noteworthy for their bold designs, three-dimensional effects, and subtle use of color, the panels were expertly fashioned with minute tesserae using a combination of techniques. Since their discovery in the nineteenth century, they have been restored to varying degrees.

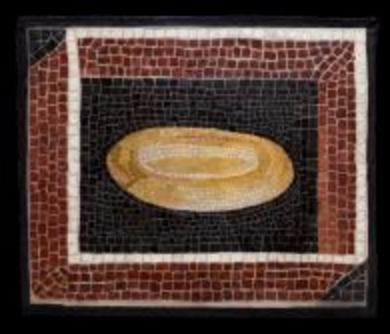

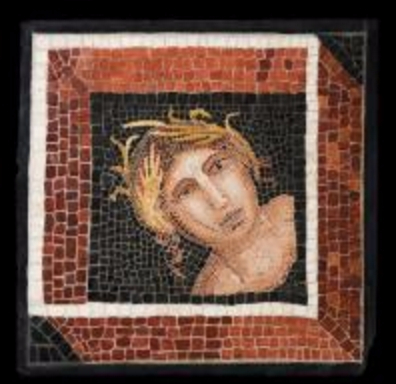

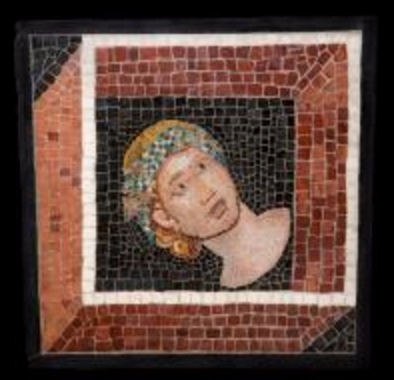

Six of the panels depict food or objects associated with dining and hospitality and include the following: a multihued fish laid out on a golden platter (fig. 146–153.1); a live white rooster whose legs are bound (fig. 146–153.2); a round almond cake on a footed stand (fig. 146–153.3); a yellow oval object, perhaps representing either a loaf of bread or a platter (fig. 146–153.4); a brazier (a metal device used for heating and cooking) on a low platform, with flames licking upward (fig. 146–153.5); and a closed sack (fig. 146–153.6). The remaining two panels have female heads depicting personifications of seasons. The dark-haired figure wearing a delicate crown of grain stalks might represent Autumn (fig. 146–153.7), while the fair-haired figure wearing a broad wreath might depict either Spring or Summer (fig. 146–153.8).

In each panel, the motif is represented against a plain black background. It is framed by a wide red band and an intersecting narrow white band, which combine to produce an illusion of three-dimensionality. Such framing devices suggest that these panels might have been fashioned as emblemata, which were created independently and then set into the floor during its assembly.

Discovery and Modern History of the Panels

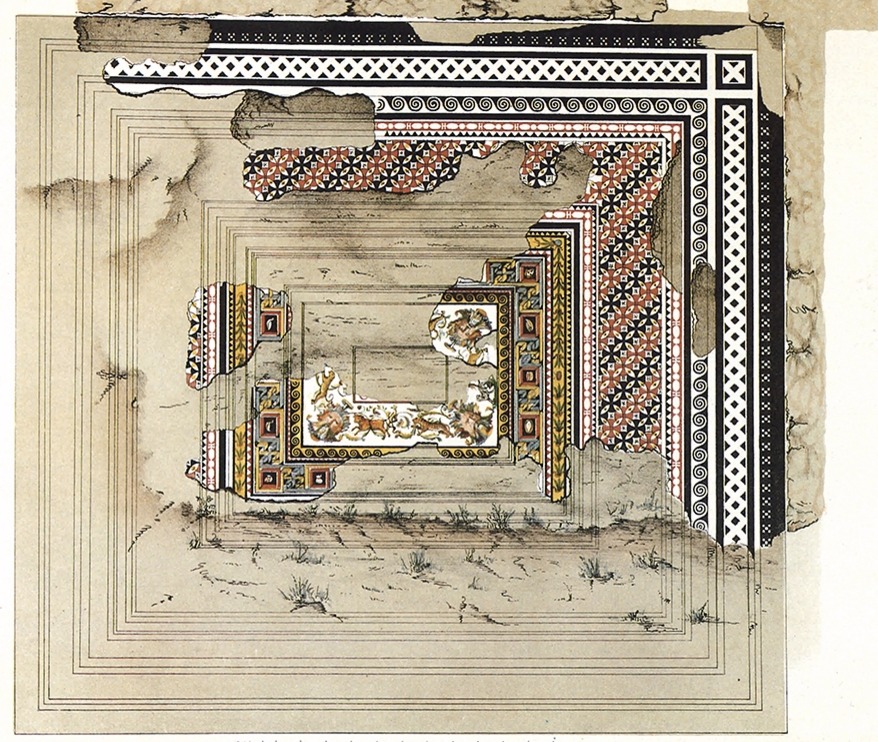

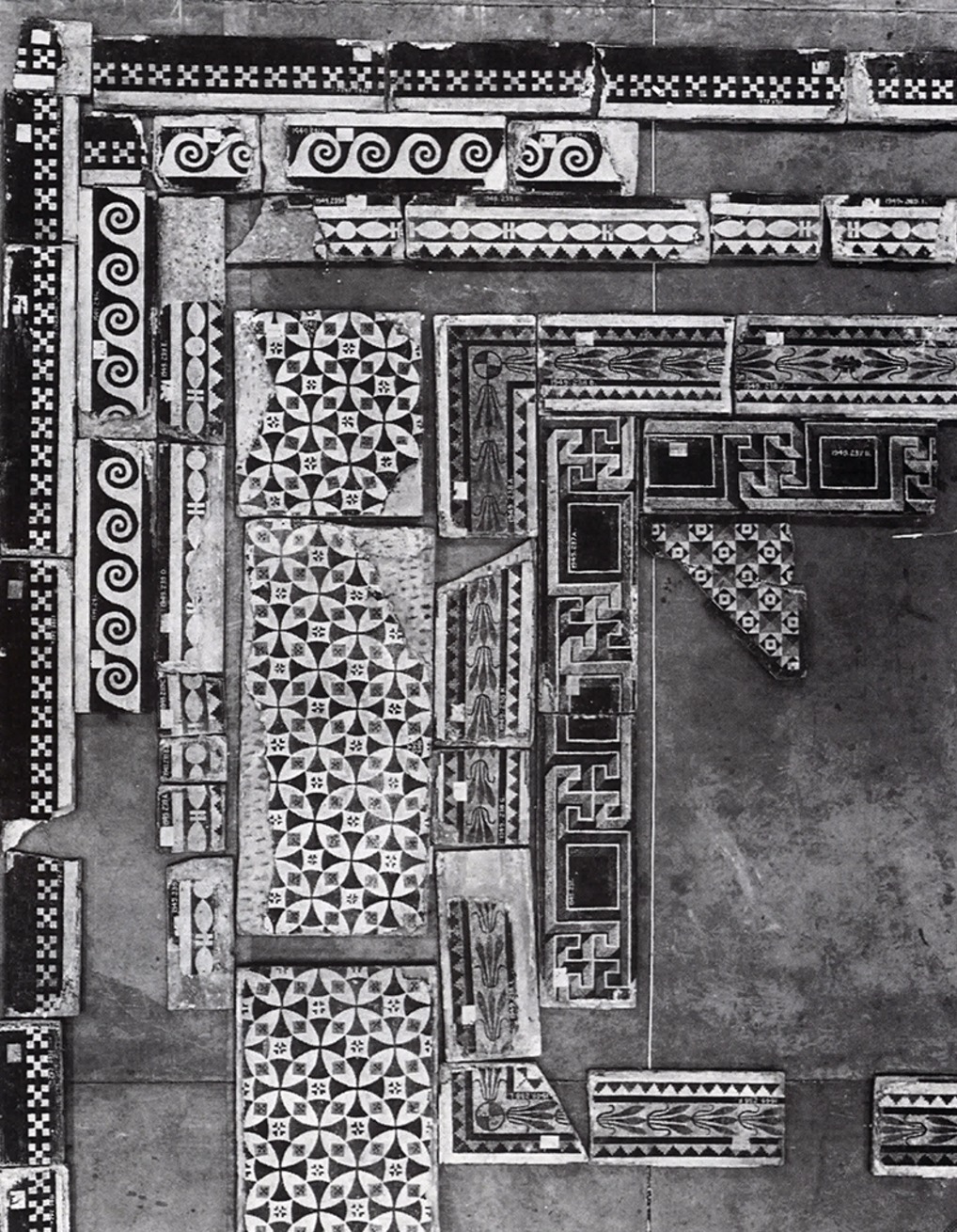

In 1822, during their visit to Rome while on the Grand Tour, Lord Charles Kinnaird (1780–1826) and Lord George William Russell (1790–1846) viewed the remains of a large Roman mosaic pavement that had recently been discovered on the west side of the Tiber River. Its findspot is unknown, but nineteenth-century accounts suggest that it was the Vigna della Missione, “about half a mile beyond the Porta Portuensis” (the Porta Portese gate), within the modern neighborhood of Monteverde. Lords Kinnaird and Russell promptly purchased the pavement and divided the finds between them. A drawing produced at the time of its discovery documents the mosaic’s original appearance as well as its approximate dimensions of 29 by 28 feet (fig. 146–153.9).

Description of the Pavement

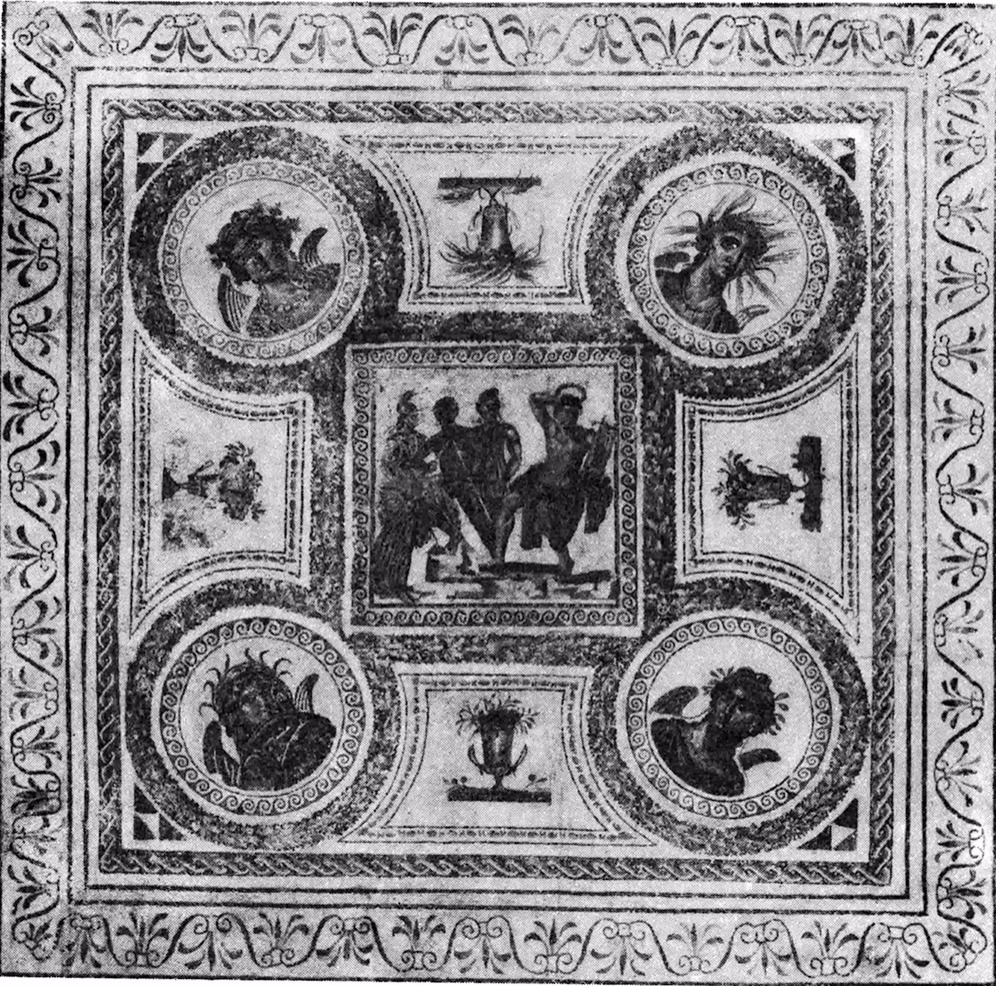

The entire pavement comprised numerous concentric bands of ornamental and figural decoration. At its center was a wide rectangular band—parts of which were already destroyed at the time of its discovery—featuring intricate figural motifs that exhibited a nuanced use of color and shading against a white background. Three of its preserved corners included sensitively modeled heads of Oceanus, the river encircling the entire world and endpoint of all streams, who was personified as a bearded, mature god. Between these heads appeared images of wild beasts charging and frolicking through scrolls of delicate foliage.

The remaining parts of the pavement incorporated a variety of ornamental patterns created in a limited palette of colors. The outermost bands were fashioned in black and white tesserae and included a cruciform pattern, a lattice pattern formed by diamonds, and a circular wave pattern. The next several bands included some colored tesserae and depicted patterns featuring bead-and-reel motifs, crowstep motifs (stepped triangles), intersecting circles forming saltires (diagonal cross motifs) and squares with concave sides, and stylized laurel leaves and berries. One of the innermost ornamental bands included a meander pattern rendered three-dimensionally, which alternated with panels featuring figural motifs set within illusionistic frames. The panels now in Chicago belonged to this band. The complexity and richness of the pavement’s design as well as the exceptional quality of its workmanship suggest that it was created by a team of highly skilled mosaicists.

From Rome to Scotland to Chicago

Following their discovery, the fragments of the mosaic pavement were restored in Rome by Giuseppe Baseggio under the supervision of Lord Kinnaird. The panels that he obtained were shipped to his stately family mansion, Rossie Priory, in Perthshire, Scotland. These included the eight panels mentioned above, two heads of Oceanus (see fig. 146–153.10), and several fragments depicting animals cavorting through foliage (see fig. 146–153.11 and fig. 146–153.12), which were displayed on the south wall of the cloister, as well as numerous segments of the ornamental bands (see fig. 146–153.13), which were installed in the stables.

Following their exportation to Scotland in 1826, the Kinnaird panels remained largely out of the public eye until 1987, when the fragments of the ornamental bands were sold at auction. Three years later, the eight panels considered here were lent to the National Galleries of Scotland. In 2009, the panels were sold at auction, where they were purchased by a Chicago couple. The owners lent the mosaics to the Art Institute of Chicago for exhibition in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Galleries of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Art, where they have been displayed since November 2012. Subsequently the couple generously promised to give them to the museum at a future date.

Xenia Mosaics

The six mosaic panels in Chicago depicting food and objects related to dining are of a type described by modern scholars as xenia. This term originated in the ancient Greek world, where it referred broadly to the concept of hospitality, with hosts providing food, shelter, and protection for their guests. According to the Roman architect Vitruvius, this practice of providing gifts of food inspired the use of the term xenia to refer to artistic representations of such items. These images appeared in wall paintings and mosaic pavements and typically took the form of small, framed compositions, in which the items were depicted either in groups resembling modern still-lifes or as individual motifs.

The foods depicted in xenia mosaics vary considerably, from locally grown produce to rare and exotic animals from the farthest reaches of the empire. Popular items include fruits and vegetables, sometimes arranged in bundles, baskets, or other vessels; breads and cakes; various edible birds, such as poultry, peacocks, and songbirds (see fig. 146–153.14); wild game (see fig. 146–153.15); and fish and other marine life, both from the sea and from freshwater sources. Tableware and vessels made of precious metals and glass are represented both as containers for food and as luxury items (see fig. 146–153.16). This diversity of motifs can be seen in a pair of mosaic pavements from Toragnola on the Via Prenestina in Rome (fig. 146–153.17 and fig. 146–153.18), where each item or group of items is similarly framed by ornamental patterns.

Xenia mosaics are attested from the second century A.D. onward, particularly in Italy and North Africa. They usually appear in domestic contexts and typically adorned reception spaces, including dining rooms, or triclinia. This room was the setting of the banquet, or convivium (Latin for “living together”), an important event at which socially prominent hosts would entertain their friends, clients, and business partners within their lavishly adorned homes. It was of special interest to Roman authors, who described the convivium as a veritable feast for the senses that featured exotic cuisine, impressive displays of expensive tableware, and lively entertainment. In such settings, xenia mosaics communicated messages to visitors about the owner’s hospitality and affluence. They also suggested the abundance and variety of foods, whether imported from a great distance or raised on the host’s estate, which might be enjoyed at a banquet within the home.

The fish shown in one panel likely depicts a red mullet (Mullus barbatus) (see fig. 146–153.1), a type of fish that was commonly consumed at Roman dinner parties and was on occasion raised by the wealthy in private fishponds for pleasure and entertainment. The platter on which it lies presumably alluded to the host’s wealth: the broad white band along the lower edge indicates a reflection, suggesting that the tableware was made of precious metal. The live, trussed rooster gazing back at the viewer in another panel (see fig. 146–153.2) might have referred to the abundant livestock that was available on the host’s estate, which could be consumed at a meal or sold for a profit.

The panel depicting the cake (see fig. 146–153.3), with its careful arrangement of almonds on the top, probably suggested that a skilled baker worked in the home. A similar message could have been intended in the panel showing the item that might be a loaf of bread (see fig. 146–153.4). Equally, given its formal similarity to the platter in the fish panel, it may represent an empty platter that was likewise made of a precious metal. The small white sack tied with a brown cord (see fig. 146–153.6), the contents of which are indeterminable, might have contained ingredients used in cooking. Finally, the brazier with its open flames alluded to heating or roasting food (see fig. 146–153.5).

Like the images of food and other items, the two female heads depicting personifications of seasons (see fig. 146–153.7 and fig. 146–153.8) can also be connected broadly with the themes of abundance and prosperity, as they were thought to evoke such concepts as fertility, regeneration, and felicitas temporum. The Seasons were widely popular subjects in Roman art and frequently appeared in the corners of mosaic pavements, as seen in an example from Thysdrus (modern-day El Djem), Tunisia (fig. 146–153.19). When combined with panels depicting xenia motifs, images of the Seasons suggested the cyclical nature of time and agricultural regeneration, which resulted in the bounty of nature that was ultimately enjoyed at the Roman table.

Date

Given the modern restorations carried out on this group of eight panels, it is difficult to assign a precise date to them, yet several features suggest that they were created in the second century A.D. First, as noted above, xenia motifs were employed in mosaics from the second century A.D. onward. Second, the use of polychrome tesserae reflects the revival of interest in richly colored mosaics in this period, in contrast to the austere black and white (bichrome) mosaics that had been predominant in Italy since the Augustan period (27 B.C.–A.D. 14). This revival of color went hand in hand with a new fashion that emerged in the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93) for highly decorative compositions combining complex ornamental patterns and figural motifs that were often set in panels or compartments. These stylistic developments are seen in a mosaic of Antonine date from a villa in Genazzano, Italy, which is composed of simple geometric motifs and curvilinear ornamental bands, the latter of which frame colorful medallions featuring naturalistic busts of Dionysiac subjects (fig. 146–153.20). Therefore, a date in the second century A.D. seems likely for the Chicago panels.

Conclusion

These eight mosaic panels once belonged to a large mosaic pavement featuring an elaborate combination of ornamental and figural motifs that adorned a luxurious home. Based on their depictions of xenia motifs and personified seasons, the panels conveyed a message of the hospitality and the prosperity of the household. The use of polychrome tesserae, as well as the overall opulent design of the original pavement, points to a likely date in the second century A.D.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

Technical Summary

The mosaics were created with the opus vermiculatum and opus tesselatum techniques and exhibit outstanding workmanship; whether they were originally prepared as emblemata is uncertain. An impressive array of stones was used for the central motifs. Differences in the size, shape, and alignment of the tesserae indicate varying skill levels of the original craftsmen or point toward intervention by later restorers. Traces of what might be original or early mortars are visible in isolated areas. The mosaics are sound but have been heavily restored, both upon excavation and in later campaigns. The mosaics display two layers of backing material: a resin of varying thickness and concrete. Most fragments retain the backings that were applied in the nineteenth century during their lifting and restoration in Rome after their discovery.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

Primary material: stone, probably limestone

Secondary materials: glass, mortar

The uniformity, minute size, and compact nature of the tesserae made sampling a virtual impossibility. In the absence of formal analysis, stone has been identified, where possible, by visual examination, a method not without pitfalls. For instance, if the stone is cut across a diagnostic feature such as a vein, it will have a speckled rather than a banded appearance, and if the parent stone is cut into small pieces, diagnostic features may be eliminated entirely. Furthermore, mosaicists did not always employ slabs of stone from known quarries. They often used random pebbles or worn stones found in stream beds or other uncatalogued or undocumented sources. This is especially the case for the most unusual stones or those with the most striking coloration. Moreover, the fabrication process itself can contribute to variations in the stone, such as preferential staining or banding in areas of greater porosity. To complicate matters still further, mosaicists could supplement the palette provided from natural stones by exploiting the different oxidation states of the compounds in the stones. They did this by applying heat to alter the stone’s colors. Stones in shades of yellow especially lent themselves to this kind of alteration.

The possible attribution of limestone rather than marble is supported by comparative studies of other mosaics and by the properties known to be preferred by craftsmen. Stone used in mosaics must have good workability: when struck, it should not crumble, produce splinters, or result in conchoidal break edges. The stone should also be hard enough to take a polish. And it should be durable—able to withstand long-term use as well as the effects of heat, cold, and rain. Polishable limestone meets or exceeds all these criteria.

On each mosaic, a central motif is surrounded by a quadrilinear or rectilinear field of black tesserae. From a distance these tesserae look uniform, but on close examination they appear highly variegated (fig. 146–153.21). The blue-gray or olive-green inclusions confound a solid attribution, but based on their large grain size, the stone might be of Italian origin. The black field is in turn surrounded by a white square or rectangle flanked by alternating bands of either dark- or pale-red-brown tesserae. The white stones have a variable appearance (ranging from translucent to opaque; warm to cool; and with and without inclusions, veins, and bands) and are extremely difficult to identify given the lack of significant diagnostic features. Their lack of crystallinity, however, suggests that they are limestone rather than marble. The dark-red tesserae also have a variable appearance but possess diagnostic features such as prominent bands (both dark and light) (fig. 146–153.22) and inclusions (ocher, orange, ivory, and brown) (fig. 146–153.23), making Rosso Francia a possible attribution. Like the white stones, the pale-red stone eludes attribution, but the nature of its crystalline structure indicates that it too might be limestone.

The central elements of the mosaics exhibit an astonishing variety of stones, many of which show lively banding, marbling, or inclusions. Some resemble those used for opus sectile and raise the possibility that mosaicists employed fragments or leftovers from these workshops. Stones with banding or veins are placed next to each other in such a way that bands run in different directions, some vertically, some horizontally. Stones showing variations in a color family, such as multiple shades and types of yellow, likely reflect differences in a single type of stone rather than different types of stones.

Cat. 146, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Fish on a Platter

The palette used to create the fish includes the following colors:

Yellow (eight types): two are dark mustard either with or without black inclusions; a third is a pale, translucent yellow free of inclusions; the fourth is yellow-orange with brown and white inclusions; the fifth is a dull yellow with dark-green inclusions. Three other types assigned to the yellow family have more of a brown coloration, much like a raw sienna. Of these, one is free from inclusions, another shows white banding, and the last is strongly marbled with russet.

Orange (five types): a bright orange with yellow-orange lines, strongly resembling a breccia; another bright orange with red banding; a pale orange with orange inclusions; and a dull orange with white and brown inclusions. The fifth type—stones with a bright-orange tone, no inclusions, and distinctly planar surface—have been tentatively identified as glass.

Purple (five types): a pale red-lavender free of inclusions; a lavender with more of a blue tonality and dark inclusions; a darker blue-lavender without inclusions; and a darker red-lavender with heavy inclusions of white and pale pink. The fifth type, and the most interesting of the purple stones, is dark maroon heavily banded with russet, ocher, and black (fig. 146–153.24).

Pink (five types): two are pale and translucent either with or without white inclusions; a third is a dusty mauve with white veins and dark red-brown inclusions; a fourth is a pale pink with orange inclusions; and the fifth is a deep coral with dark-red veins.

Olive (four types): three bear a more yellow tonality, and, of those, one bears yellow inclusions, a second has black inclusions, and a third has white inclusions. The fourth type has more of a green coloration with some white banding.

Green and blue (eight types): three are seafoam green, and, of those, one has amber marbling and blue inclusions, a second has green inclusions, and a third has large white inclusions; a fourth type is turquoise with large white inclusions; a fifth is sky blue with dark-blue inclusions; a sixth is blue-green with dark-blue inclusions; a seventh is a uniform, pale blue free of inclusions or striations; and the eighth is dark green-gray with dark-gray specks. The seafoam-green varieties resemble marl, an argillaceous limestone.

Cat. 147, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Bound Rooster

The palette of stones used to create the rooster includes the following colors:

Orange (five types): two are a peach color either with or without orange inclusions; two are a bright orange either with or without yellow and orange inclusions; a fifth is a deeper tone free of inclusions but showing a slight marbling.

Pink (three types): one with orange inclusions, another with heavy marbling, and the third a dusty gray-pink. The first two pinks are possibly Rosso Verona.

Yellow (two types): pale with white and yellow inclusions and a dark yellow with dark-yellow specks. The latter type may be Giallo Antico.

Maroon: deep coloration with purple banding.

Olive (two types): one with inclusions of white and another with ocher and pale-green marbling. The provenance of this stone may be the Apennine range in central Italy.

White (two types): one translucent and one opaque, both free of inclusions.

Buff (five types): one with an orange tonality and orange inclusions; a second with a pink tone and dark inclusions; the third a deep ivory with white inclusions; the fourth a pale sandy-brown with white inclusions; and the fifth a darker gray-brown with white inclusions.

Cat. 148, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting an Almond Cake

The palette of stones used to create the cake includes the following colors:

Buff (three types): one a pale yellow, the second a darker yellow, and the third a pale tan with large tan inclusions.

Gray (two types): one with an olive-green tonality, and the other with a slightly purple tonality.

Red (two types): a uniform, oxblood red and a dark maroon with ocher inclusions.

Orange (two types): a bright orange with white and orange circular inclusions and a brownish orange with dark-brown inclusions.

Yellow (three types): one peach-colored yellow with green inclusions, and two mustard yellow with either translucent banding or white inclusions.

White: The absence of crystallinity suggests that these are limestone rather than marble.

The dark-red stone of the side walls differs from the stone used in the rest of the mosaics and is characterized by prominent ocher-colored inclusions.

Cat. 149, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Loaf of Bread or a Platter

The palette of stones used to create the loaf of bread or platter includes the following colors:

Yellow (seven types): one pale with white marbling and black specks; one a deeper yellow with ocher inclusions; another pale, almost white, with lemon-yellow inclusions; another with salmon-pink inclusions; a pale ocher with no inclusions; a buttery yellow with no inclusions; and a mustard with ocher inclusions.

Pink (four types): two are a dusty pink either without inclusions or with ocher inclusions and pink and orange specks; a third has vivid orange and white inclusions; and a fourth is pale pink with orange veins. This last is highly unusual, seen only in opus sectile work (fig. 146–153.25).

Sienna (three types): one is an even, dark mustard-brown with ocher inclusions; two are a pale sienna either with or without dark-sienna inclusions.

White (three types): a cream color, a buff color, and an ivory color, all without inclusions.

Cat. 150, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Brazier

The palette of stones used to create the brazier includes the following colors:

Red: a deep maroon with no inclusions and a granular surface.

Pink (two types): one showing prominent maroon inclusions and another with white veins.

Orange (three types): one with more of a coral tonality, another of a medium hue with isolated orange and white inclusions, and the third a dark orange-red with few inclusions.

Yellow (three types): all have a mustard color, one with more of a brown tone; one a paler mustard with some banding of white and ocher; and a third with red veins, likely Giallo Antico.

Blue (two types): one tessera has a slightly purple tonality; the others have a dark bluish-gray color with dark-gray veins. The latter stone strongly resembles marble, but the resemblance could be explained by grouts or mortars that have become impregnated within fractures and flaws.

Purple: a very unusual stone with inclusions of dark pink.

Gray: a green tonality with prominent inclusions of white and ocher.

Olive: a pale earth-green with dark bands. It is likely that these stones were sourced in a river.

Cat. 151, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Sack

The palette of stones used to create the sack consists primarily of earth tones and includes the following colors:

Brown (four types): one with numerous inclusions resembling granite; another strongly banded; a third with turquoise inclusions; and the last a pink-brown body with dark-red specks. Several of these have the appearance of sandstones, varieties of which can be polished.

Ocher (two types): a uniform tone with scattered dark inclusions and another with red veins. Giallo Antico is a possible attribution for the latter stone.

Green: a seafoam coloration with green and white inclusions.

Buff: with white inclusions.

White (two types): one opaque and the other translucent, both with no inclusions.

Gray: with a purple tonality.

Fabrication

Method

The mosaics were created using a combination of opus tesselatum and opus vermiculatum techniques.

The design of the mosaics uses white boxes or frames with red walls to provide depth and perspective. Many of the boxes have two dark-red walls, one on the interior, one on the exterior, and two pale-red walls, again one on the interior and on the exterior, highlighting the relief effect. The central decorative elements are located within these walls.

The original workmanship is of extremely high quality, and many of the details, such as the decorative triangular border around the plate beneath the fish, show an impressive command of the medium (fig. 146–153.26).

The process of creating a mosaic did not begin with the arrangement of stones on the surface. First, an entire substructure below the tesserae had to be prepared and laid down. In On Architecture, Vitruvius described the ideal foundation as being made of four layers. The bottom layer was the statumen, a bedding of fist-sized stones set into the floor. Next came the rudus, a mixture of rubble and lime beaten solid to a thickness of about nine inches. The third layer, the nucleus, was made of fine mortar mixed with crushed terra-cotta tiles or potsherds and lime and was about six inches thick. Finally there was the setting bed, a fine layer of mortar just a few millimeters thick into which the tesserae were placed.

Before spreading out the setting bed, the mosaicist set down guidelines to indicate the layout and placement of the tesserae. These guidelines were either scored into the still-damp nucleus with string, nails, compasses, and possibly calipers or painted, usually in red or black, on the dry surface. Archaeological evidence confirms the use of both techniques. Once the guidelines were laid, the setting bed was troweled on, covering only as much space as the mosaicist could complete before it dried.

To create the tesserae, the mosaicist broke a large piece of stone into smaller stones by striking it with a marteline against a chisel-like blade (a “bolster blade” or a “knapping blade”) set in a block of wood. For a long-term project, mosaicists stockpiled tesserae in a central location. Most mosaicists, however, were itinerant and cut stones as they worked. In either case, supply and demand was a perpetual concern.

After the setting bed was laid, the tesserae were pressed hard into it, allowing the mortar to squeeze up through the spaces between the stones. The stones were then leveled, and the floor was ground down to eliminate unevenness. A thin wash of plaster, sometimes colored, was spread over the floor to fill up the interstices between the tesserae.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The restorations and interventions performed since excavation have rendered the objects mostly devoid of signs of original workmanship.

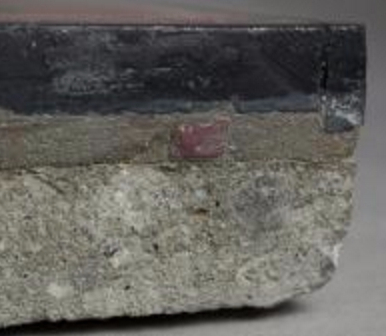

Traces of what appear to be original mortar, notable for the appearance of the aggregates contained therein, can be seen in isolated areas (fig. 146–153.27, fig. 146–153.28).

In several areas, red specks can be seen on many of the white tesserae within the border. These specks may have been introduced at the polishing stage, when stone that was being ground down was sometimes stained by tinted grouts and mortars or by a slurry containing a red abrasive.

Mosaics were created by craftsmen of varying skill levels, and division of labor was a standard practice. Hallmarks of this variety can often be detected within a mosaic. The variation in handling of the black tesserae above and below the fish, for example, reveals the work of two craftsmen. In the top portion, which has been rendered more skillfully, the black field seamlessly fills in the space between the fish and the upper border, and there is no need for a contour line around the fish. In the bottom section, however, a double line surrounds the fish, with tesserae gradually giving way to the lower border (fig. 146–153.29). Similar distinctions appear in the other mosaics and are addressed below in the condition summaries.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Condition Summary

Overall the surfaces of the mosaics are heavily abraded with very fine networks of lines and scratches. Isolated, deeper scratches also appear throughout, and chips and losses are visible on many corners and edges of the tesserae.

Cat. 146, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Fish on a Platter

The frame surrounding the fish is meant to project upward to the viewer’s left with the dark walls on the short sides. There is a significant lack of homogeneity along these walls with light and dark tesserae interspersed at random. The interior wall on the short side is uniform in color, but the top proper right corner has been rendered almost entirely of dark tesserae, diminishing the depth perception and suggesting reintegration (fig. 146–153.30). The decorative border does not continue around the entire perimeter of the plate but instead gives way to rows of square tesserae on the proper left side (fig. 146–153.31); this may also be a restoration. The tesserae comprising the bottom black triangle at proper right are far too large relative to the rest of the composition. This section of the mosaic could have been completed by a mosaicist of lesser skill, but the differences in color along the edges suggest a later reintegration. The tesserae, particularly those in the white section of the plate, have been heavily retouched with an opaque paint that does not always correspond to the color of the underlying stone.

Cat. 147, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Bound Rooster

Based on the position of the white tesserae, the frame is meant to project downward to the viewer’s right with the dark walls on the short sides. The composition is missing its black triangles at the top proper left and the bottom proper right, making the three-dimensionality hard to parse. Furthermore, the coloration of the uppermost wall, which should be pale, is vague with dark and light tesserae interchanging at random along the length. The proper right corner has been indicated not by the transition from light to dark but by the insertion of a much darker line (fig. 146–153.32). Taken together, these features constitute reasonably strong evidence that much of this is reintegration. Along the bottom wall near the proper left side, the pale tesserae have been punctuated by a vertical line of three dark tesserae and a single tessera appears randomly in the bottommost row at center. Within the black field, the harsh transition of small tesserae to a double row of large tesserae at the outermost edges is highly unusual and raises the possibility that this area was restored or reintegrated (fig. 146–153.33). Correspondingly, a bisected line of tesserae along the proper right edge is also anomalous (fig. 146–153.34). In other areas, strange choices appear to have been made in the placement of tesserae, which do not flow together well (fig. 146–153.35 and fig. 146–153.36). Minor surface undulation can be felt above the rooster’s back, and an associated crack that has been filled and retouched extends diagonally downward through the cockerel’s breast and into the black field opposite. Another crack bisects the tail feathers. Numerous small damages and chips, many of which have been filled and overpainted, are visible at the tips of the tail feathers. Many of the black tesserae are in poor condition and are heavily pitted with flaws and eroded areas; several of the most prominent pits are unfilled. A great deal of opaque retouching has been done in the white and buff areas.

Cat. 148, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting an Almond Cake

The frame surrounding the cake is meant to project upward to the viewer’s left with the dark walls on the lateral sides of the composition. There is considerable homogeneity along these walls and only a few light and dark tesserae scattered randomly, indicating very little restoration or reintegration. Indeed, the top proper left corner has been executed in textbook fashion (fig. 146–153.37). The insertion of triangular tesserae around the proper left side of the foot of the cake pedestal, however, is unusual and not in accordance with the accepted method of laying out and arranging tesserae within the composition (fig. 146–153.38). Equally unorthodox are the very large tesserae at the outer margin of the black field (fig. 146–153.39). Given the few signs of reintegration elsewhere, these areas are likely the work of a less skilled craftsman. There is some surface undulation above the cake at center.

Cat. 149, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Loaf of Bread or a Platter

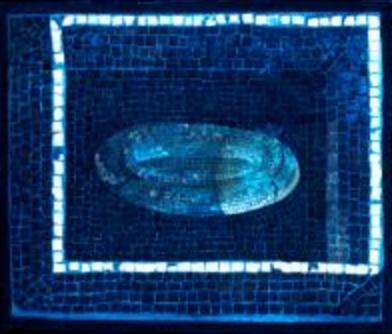

The composition extends up and to the viewer’s right. The contrast between light and dark areas is very poor, suggesting that much of the surrounding frame has been reassembled, possibly with scavenged tesserae from the site. The bottom proper right corner is deeply flawed and curves around the outer edge rather than being at right angles, surely the work of a later restorer (fig. 146–153.40). A large area of replacement tesserae on the proper left wall has been filled with a coral-colored stone (fig. 146–153.41). The band of tesserae immediately surrounding the object of bread or platter changes halfway around, going from thick to thin (fig. 146–153.42), and a row of poorly placed triangles appears just above the object on the proper right side (fig. 146–153.43). A prominent crack bisects the center of the bread, and the tesserae on the proper left side are slightly raised, lending the panel a “humped” appearance. There is no preferential wear on any one side of the crack, indicating that it may have formed during settling and burial as opposed to during the lifetime of the floor. Under ultraviolet illumination, the half of the loaf of bread or platter to the proper left of the crack fluoresces differently from the other half (fig. 146–153.44). Although the reason for this discrepancy is unknown, it is clear that the proper left half of the object has a markedly different quality from the other half. UV examination also reveals the presence of a large crack on the proper right side of the object, signifying that this area has been filled and retouched with some success, considering its imperceptibility in visible light. There is also a prominent step across the top line just above the first row of black tesserae. At the bottom proper left corner, three tesserae are set slightly below the plane of the rest of the mosaic. They have been machine polished and must have been inserted later. The top proper right corner is also slightly stepped, and the new mortar overlays the stone, resulting in several submerged tesserae. Large inclusions that look like the ocher stones in the bread are interspersed in the mortar between the black tesserae on the lower proper left quadrant (fig. 146–153.45). These inclusions are not typical for a lime mortar and may have been introduced during a restoration after excavation. A significant portion of the surface, especially the paler tesserae, has been heavily overpainted.

Cat. 150, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Brazier

The composition projects upward to the viewer’s right, but there is virtually no contrast between the walls, which may have been created after excavation. The black tesserae are of different sizes, raising the possibility of two craftsmen at work, one on the central motif and another on the background. A small inclusion of an orange stone appears within the black field on the proper left side (fig. 146–153.46). The presence of horizontal, oblong tesserae within several of the rows is unusual and may have been a later integration (fig. 146–153.47). The diagonals at the top proper left (fig. 146–153.48) and bottom proper right have been executed in a pale stone, at odds with the treatment of the corners of the other mosaics. Several tesserae along the proper right side of the top wall are deeply pitted. A deep abrasion about 4 cm long is visible in the center of the bottom wall. The small undercuts below the outermost edges of the table may have been made to provide perspective to the composition, lighten the composition overall, or lend emphasis to the brazier itself (fig. 146–153.49).

Cat. 151, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Sack

The composition projects downward to the viewer’s left, with the dark walls at the top and bottom of the composition. The top proper right corner is not articulated, and the tesserae in the bottom proper right corner look as though they were placed and scored rather than cut and placed (fig. 146–153.50). The treatment of this corner is not in keeping with the corners on the other mosaics. The tesserae comprising the black triangle at the top proper right are far too large and have been cut simply to fill the space as expediently as possible (fig. 146–153.51). This clearly betrays the original handling and strongly suggests a subsequent integration. There is a large unfilled pit between the ocher tesserae at the proper right shoulder of the sack.

Conservation History

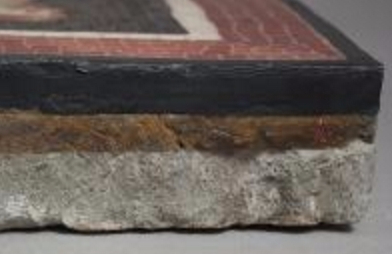

The mosaics were conserved by Giuseppe Baseggio in Rome just after their discovery in 1822. The mosaics were lifted, that is to say, the tesserae were separated from the bedding layers and rebedded outside of their original context, a very common nineteenth-century practice. No known documentation details the steps and materials used in this intervention, but based on existing protocol, the tesserae were likely covered with a facing to keep them in place during the violent process of lifting. The mosaic was then likely cut out of the mortar bed from the sides and back and, once excavated, placed facedown into wooden frames.

It is possible that these small mosaic panels, like emblemata, were prefabricated and then inserted as separate units during the assembly of the rest of the floor. If so, their extraction would have been less difficult and their treatment less aggressive and traumatic than the lifting procedure that would have been used on the surrounding floor. The lifting method had tremendous potential for damage, even disaster. At best, it risked disturbing the surface plane and introducing warps or distortions to the tesserae. This may well have happened to cat. 149, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Loaf of Bread or a Platter.

In nineteenth-century restorations, the bedding mortar was often completely removed, exposing the undersides of the tesserae. This is no doubt what occurred during the treatment of these six mosaics, given the lack of original mortar remaining between the tesserae. While an effort to retain the original mortar between the tesserae may have been made, it is likely that during the subsequent steps of restoration or during movement, these delicate slivers of material, without benefit of adhesion to the original mortar bed, fell away.

After the tesserae were extracted and the bedding mortar removed, the mosaics were rebacked. Tesserae that were missing were replaced by either dislodged stones scavenged from the site or new tesserae cut from stones with a similar appearance.

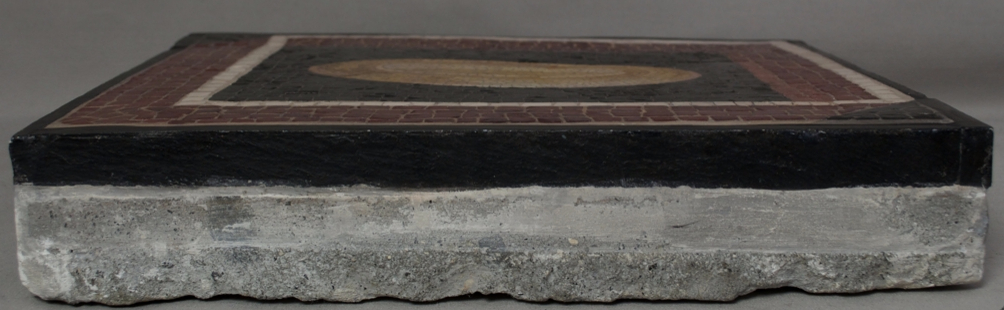

The rebacked Chicago mosaics were squared off and framed with bespoke slabs of black stone. A hard, dark-brown material with extensive craquelure is visible between the bottom edges of the frames and the backing material below (fig. 146–153.52). This material has been identified as beeswax; it was presumably used as an adhesive to affix the stone frames in place and flowed out from behind the stone prior to setting. The last phase of the restoration involved grinding and polishing the surface of the tesserae, which gave the mosaic an appearance more akin to a decorative pietre dure than to a mosaic from antiquity.

By the mid-nineteenth century, concrete made from Portland cement was the material of choice for both rebacking and resetting. These six mosaics are backed with concrete and with a layer of ocher-colored resinous material, ranging in thickness from 1 to 15 mm, that appears between the backs of the mosaics and the fronts of the concrete slabs (fig. 146–153.53). This resin has been identified as colophony bulked with calcite, an adhesive widely employed in restoration during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Strewn tesserae are embedded in the uppermost backing layer on cat. 147, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Bound Rooster (fig. 146–153.54 and fig. 146–153.55), suggesting that this layer is intimately associated with the site work done by Baseggio just after excavation. The thickness of the colophony is tremendously variable not only across all the mosaics but within each mosaic. For example, on the proper left side of cat. 150, Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Brazier, the back of the mosaic appears to be in direct contact with the concrete without benefit of adhesive, while on the opposing side the colophony is 7 mm thick. This layer has sometimes been painted gray to blend with the concrete.

Often the overflow of resin is visible on the concrete and the stone frames, and other times the resin appears to have been cut or sawn. In still other cases, the concrete has overflown the resin.

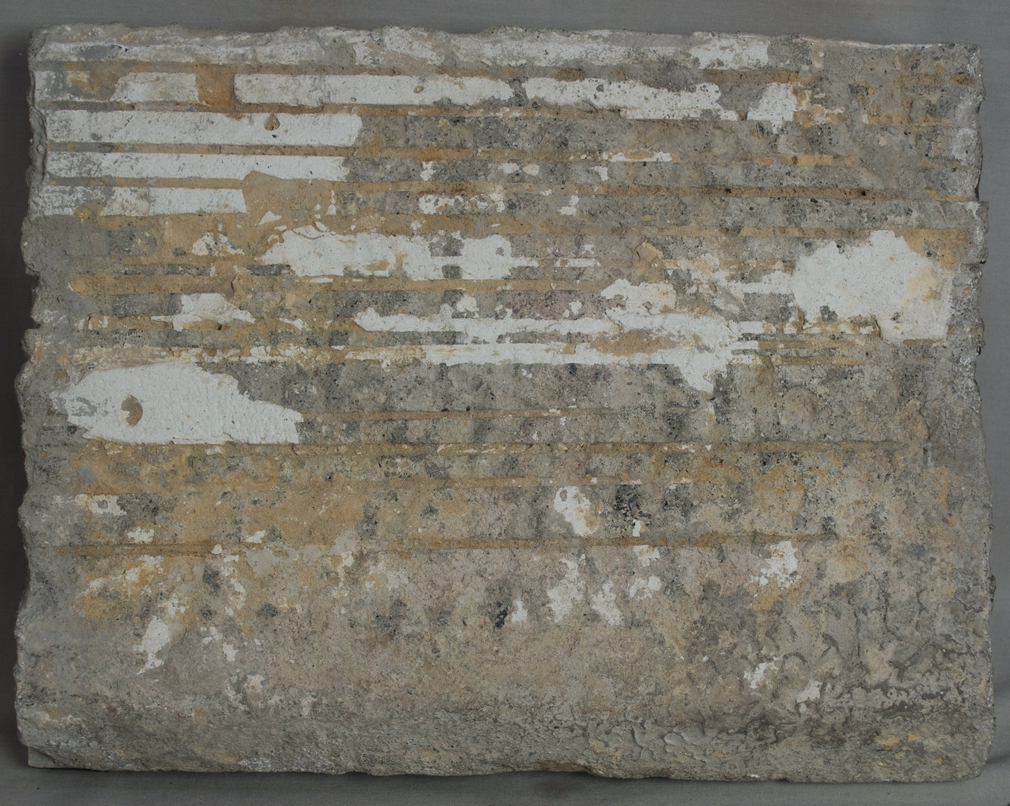

Some of the mosaics display misalignments between the frame edges and the backings (fig. 146–153.56), and elsewhere, the straightedges used to construct the molds for pouring the concrete have occasionally left imprints on the concrete (fig. 146–153.57). The concrete is highly variable in composition, ranging from relatively homogeneous to highly irregular with abundant inclusions, one of which is a sizable mass of what appears to be granite (fig. 146–153.52). The mosaics with concrete backings containing large aggregates display crisp rectilinear borders and sharp corners, and the versos are smooth. The mosaics with backings consisting of more finely graded concrete display irregular or underrun edges (fig. 146–153.58), damaged corners, and regular horizontal cuts in the back of the concrete that indicate the use of a wire saw (fig. 146–153.59). Plaster accretions can also be seen on the versos of a number of mosaics. Viewing these disparate conditions together, it is possible to construct a theoretical narrative. The mosaics were assembled, backed with colophony, and mounted onto backings consisting of relatively fine, homogeneous concrete in Rome after their excavation. After being shipped to their destination, they were embedded into a wall that included some amount of plaster surround. They were later removed with a wire saw; this process sometimes caused damage, which was repaired either by supplementing the backs with additional concrete or recasting the backings with a coarser grade of concrete.

In the intervening years, the fronts of the mosaics were coated with a variety of substances, including pigmented waxes. Photographs in Sotheby’s 2009 Old Master Sculpture and Works of Art sale catalogue show that the pigmented wax covered not only the tesserae but also the mortar, rendering considerable homogeneity to the objects. In addition, the stone perimeters of each mosaic were painted, some in black, some in white. Many of the corners were also painted in a terra-cotta color, obscuring the tesserae in those areas.

In 2010 the panels were treated by a Chicago-based conservation firm. The paint and wax on the surface of the mosaics were removed with successive poultices of solvent gels. Wax that remained adhered onto the mortar after poulticing was mechanically removed with a variety of hand tools. After cleaning, only a few tesserae appeared to be missing, and these were replaced with reproduction tesserae made from tinted epoxy resin. A bespoke tinted mortar was skimmed across the surface of each mosaic, in accordance with the varying topography of the tesserae, uniformly covering the original restoration mortar. The mortar mix contained no sand so that it would not scratch the surface during application or removal. The new mortar was then toned with water-soluble media, which were also used to square off or paint in missing areas.

In some of the mosaics, the paler stones were covered in opaque paint, completely obscuring the underlying stone. Such treatment is not mentioned in the treatment record from 2010, so it is unknown when the intervention occurred and why it was not removed in 2010.

Rachel C. Sabino