Cat. 138

Cameo Portraying Emperor Claudius as Jupiter

Cameo: Roman, A.D. 41/54; mount: Italian, late 16th century

Cameo: sardonyx; mount: gold, pearls, enamel; overall: 7.6 × 5.7 × 0.8 cm (3 × 2 1/4 × 5/16 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Marilynn B. Alsdorf, 1991.375

One of the treasures of the Art Institute is a large and exquisitely carved cameo with complex iconography. It was created from a blank of sardonyx, a variety of banded hardstone, with three layers of color. The top layer is golden brown and was used to tint the laurel wreath, some scales of the aegis, the front wing of the eagle, and the raised oval that enhances the white band that frames the composition. The lowest layer is a blue-gray so dark it seems black. The middle layer is white and was used to carve the figures, ground line, and oval frame; it appears bluish-white because the gem carver skillfully cut thick and thin areas to enhance the illusion of anatomy and depth.

At first glance, the iconography seems obvious—Jupiter or Jove, god of the sky and thunder, king of the Roman pantheon. He stands, turned to his right, supporting a long scepter-staff in his left hand and a thunderbolt in his right. His feet are bare. He is nude except for the aegis, the magical woolly hide of the goat Amalthea, who suckled him as a baby; it is wrapped loosely around his hips and looped over his left arm. The giant golden eagle that served as the god’s personal messenger looks up at him. However, the god is young—beardless—although the typical iconography for Jupiter shows a mature, bearded man. He can be identified as Jupiter Axur, also called Veiovis, the “unbearded Jupiter,” whose nature and powers are still debated by scholars. Veiovis’s cult image appears on coins struck during the late Republic (see fig. 138.1).

The pose and attributes echo a famous portrait of Alexander the Great commissioned from the master painter Apelles for the temple of Artemis at Ephesus but preserved only in later copies, including a carved gem now in the State Hermitage Museum (fig. 138.2). Called Alexander Keraunophoros (“thunderbolt-bearer”), the portrait did not represent Alexander as Zeus, king of the Greek gods, but symbolized that his power on earth was like that of Zeus, “so surpassing in excellence and power as to be like a god among men.” The pose and hip-mantle of the Chicago gem also correspond to a statue type created as a cult image for the deified Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.; see fig. 138.3). The stance and heroically nude body convey holiness, grandeur, and dignity.

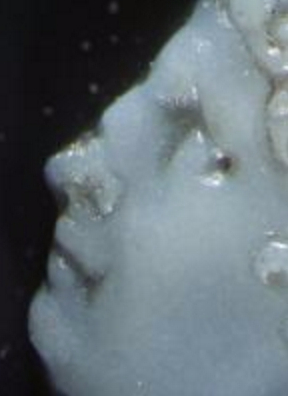

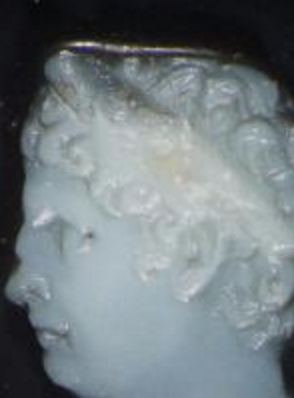

A close look at the head of the figure (fig. 138.4) reveals the likeness not of a god but of a man—Claudius, the fourth ruler of the dynasty of Julio-Claudian emperors. The flattened top of the head, the bumpy line of the profile from hairline to chin, and the roughly carved locks of hair and wreath when compared with the precise engraving of the wool of the aegis and the feathers of the eagle are all evidence that the head was recarved in antiquity, in order to cut the features of Claudius from the face of one of his predecessors—Gaius (Caligula), Tiberius, or Augustus.

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus

Claudius (10 B.C.–A.D. 54; r. A.D. 41–54) became emperor thanks to a series of improbable events. Although a grandson of Augustus’s wife Livia—hence nephew to emperor Tiberius and uncle to emperor Gaius—Claudius grew up perceived by his family as suffering from physical and mental disabilities. It was decided that he was not capable of pursuing the cursus honorum, the sequence of military and political positions that exposed young men to increasing levels of administrative responsibility. Instead he studied history and wrote books, in Latin and Greek, about the Etruscans, the Carthaginians, and Augustus—and drank and gambled to excess.

On January 24, 41, the once-popular twenty-eight-year-old emperor Gaius (who had acquired the nickname Caligula, “Little Soldier’s Boot,” in childhood) was assassinated by a conspiracy of courtiers, senators, and the Praetorian Guard. Claudius feared he was also marked for death and is said to have been discovered hiding behind a curtain by a soldier who escorted him to the Praetorian camp, where he was acclaimed as the new emperor. It was less than seventy years since the Senate had voted to give Augustus the powers that ended the Republic and unknowingly began the Roman Empire. Many senators still dreamed of restoring the liberties their families had enjoyed under the Republic, but the power of the army was overwhelming—and generously rewarded by the nervous new emperor. To the surprise of probably everyone, Claudius held on to power for almost fourteen years, maintained peace across the empire, conquered Britain as a new province, organized long-desired major projects for the city of Rome including a new harbor at Ostia, and strengthened forms of government that mirrored the traditions of the Republic but effectively centralized authority loyal to the emperor.

Imperial Iconography

Ancient Romans valued portraits not as sentimental likenesses but as edifying images of men and women. During the Republic, a realistic portrait in wax, clay, bronze, or marble memorialized a lifetime of achievements. Powerful, wealthy, and competitive families displayed portraits in their homes, paraded images of their ancestors during funeral rituals, and seized opportunities to set up their own portrait statues in public places where passersby could acknowledge their excellence. During the later years of the Republic, the old-fashioned verism of Roman portraits was increasingly affected both by the idealism of classical Greek art and by the representation of emotion and personal character of Hellenistic Greek art. The first Roman emperor, Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14) commissioned official portraits of himself and family members that show them not simply as individuals but as the youthful, heroic descendants of a god, Divus Julius. Portraits of the second and third emperors, Tiberius (see cat. 137) and Gaius, continued this dynastic theme.

Writing from firsthand accounts, the biographer Suetonius described that Claudius “had a certain majesty and dignity of presence, which showed to best advantage when he happened to be standing or seated and especially when he was in repose. This was because, though tall, well-built, with a handsome face, a fine head of white hair and a firm neck, he stumbled as he walked owing to the weakness of his knees; and because, both in his lighter moments and at serious business, he had several disagreeable traits. These included an uncontrolled laugh, a horrible habit, under stress of anger, of slobbering at the mouth and running at the nose, a stammer, and a persistent nervous tic of the head.”

Archaeologists have found inscriptions testifying to the inclusion of Claudius on earlier family monuments, but it was only after Claudius succeeded Caligula that an official accession portrait was created. The development of Claudius’s iconography can be studied on the gold and silver coins issued by the imperial bureaucracy. A gold coin probably struck to help pay the munificent accession gift to the Praetorians (see fig. 138.5) shows Claudius not as a feeble fifty-one-year-old but as a Julio-Claudian prince who resembles Augustus. A second numismatic portrait type was created in 43, when Claudius celebrated a triumph—the military, civil, and religious rituals to mark his victory over Britain (see fig. 138.6); the strongly muscled neck combines oddly with aging, wrinkled features. Claudius’s third coin portrait shows him older and more wrinkled, a return to the veristic traditions of the Republic; the type was introduced at the time of his marriage in 49 to his niece Agrippina the Younger and adoption of her son Nero in 50 (see fig. 138.7); marriage, adoption, and new portrait all emphasized the continuity of the family of Augustus in the aftermath of an averted coup. The fourth and final portrait type honored the new god, Divus Claudius, with rejuvenated features (see fig. 138.8).

The best-known portrait of Claudius is the over-life-size statue from Lanuvium, a city about twenty miles southeast of Rome (fig. 138.9). Unlike Claudius’s artificially youthful first coin portrait (see fig. 138.5), the wrinkled, squinting features reveal all of Claudius’s fifty-plus years. The heroic body, as well as the eagle, the tall scepter, and the gravity-defying mantle signal that this is an image of the emperor assimilated to Jupiter. Claudius refused divine honors while alive, and it is likely that public portraits like this are to be interpreted not as the god but as the emperor “invested with the powers” of the king of the gods. A similar statue of Claudius assimilated to Jupiter found at Olympia has rejuvenated, idealized features because it was commissioned by his successor Vespasian and represents Divus Claudius. To our eyes, the Lanuvium statue’s combination of old and new, ideal and veristic, human and divine is an uncomfortable, even laughable, combination of incompatible details. To the Romans and their subject peoples, it was the commonly accepted system of visual culture. Used for luxurious court art as well as for the humble tombstones of freedmen, the art of archaic and classical Greece was perceived as a continuum with current art. It seems likely that contemporaries understood how divine iconography and imperial portrait combined to convey a serious political message.

Complicating the study of Claudius’s surviving portraits is the fact that many of the sculptures—both statues and gems—show evidence of reworking (fig. 138.10 and fig. 138.11). Note the trimming of the hairline and arrangement of the locks of hair, as well as the way the pointed jaw and chin of Caligula have been recut to represent the heavier, lined features of Claudius. This was in part because the memory of Caligula was despised and his portraits hidden, damaged, or reused.

Imperial Cameos

Carved gems were commissioned as costly gifts for exchange within the inner court circles of the early Roman emperors. Imperial portraits on gems were created as presentation pieces—gifts that could be given to or by the emperor and his family. Following the Hellenistic traditions developed for and after Alexander the Great (see fig. 138.2), there were two ways that the first emperors of Rome could convey the fact that they were like gods among mortal men. First, the people around them invented ways to label them as special. Augustus was divi filius, “son of a god”—the adopted son of Divus Julius Caesar, who was decreed to be a god by the Senate on January 1, 42 B.C. (eighteen months after his murder). Augustus was venerated in his lifetime—the name Augustus was invented as a title for him to accompany Princeps civitatis (First Citizen). The titles were assumed by Augustus’s heirs, initially the four relatives who form the so-called Julio-Claudian dynasty, but later their successors. Second, portraits—millions of coins, painted images, statues large and small in all media, and gems—carried their likenesses, titles, and slogans. In an empire of 80 to 120 million people encompassing dozens of ethnicities, languages, and political and religious traditions, it was the person of the emperor that grew to be the unifying factor and his image that represented the central government.

The Blacas Cameo (fig. 138.12) is a powerful, posthumous portrait of Augustus carved from four flat, horizontal bands of color. The attributes of Jupiter—aegis and scepter—as well as the smooth, youthful features clearly show that Divus Augustus is one of the immortals. The portrait, probably cut down from a larger composition, shows Augustus in heroic nudity.

The closest parallel to the Art Institute’s cameo is a famous sardonyx cameo in Paris that has been known and admired in modern times at least since the fourteenth century (fig. 138.13). It represents Jupiter and his eagle in the same pose as the Chicago cameo. The Paris cameo is larger but the same shape—an oval with three horizontal layers of color, including the rare dark-blue-gray base layer. There are iconographic differences: The Paris cameo probably does not represent an emperor. Jupiter is shown as a mature man with long hair and beard; he wears an oak wreath (corona civica), a long mantle pulled over his left shoulder, and sandals. The gem carver took advantage of the bands of color so that Jupiter’s hair, mantle, and thunderbolt are golden brown and contrast brightly against the white flesh; he also varied the thickness of the brown layer around the god’s legs to give a sense of volume to the drapery. The imagery and the style of carving the figure plainly out of the layers of color echo the simple composition of the Blacas Cameo. Some scholars have recognized the features of Tiberius under the flowing hair and beard. Like Augustus, Tiberius refused to accept divine honors during his lifetime, but sophisticated flattery may have been acceptable to the man who lived in the luxurious Villa Jovis on the island of Capri for the last eleven years of his life.

At least twenty gems survive that include portraits of Claudius. One of the simplest portrait gems is shown in fig. 138.14, a three-layer sardonyx that shows the plump, middle-aged emperor wearing the corona civica and aegis. The Gemma Claudia (fig. 138.15) may have been created by the same artist. The gem carver used a five-layer sardonyx to make this allegory of parents and children, military prowess (trophies), abundance (cornucopias), and divine power (the man on the left wears the aegis and oak wreath, and the eagle of Jupiter looks up toward him). The two busts on the left have been recarved. Originally, they probably represented Caligula and one of his wives or his much-loved and deified sister Drusilla, facing his admired and deceased parents Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder. Traces of the original facial contours survive, but the woman’s hairstyle has been recut to a new fashion, and the square, furrowed, chubby features of Claudius are now clear. The cameo is sometimes called the Marriage Cameo because the updating may have been done in A.D.%nbsp;49 when Claudius married his brother Germanicus’s daughter, Julia Agrippina the Younger. The size, use of the wavy bands of color as part of the design, and complex allegory of the Gemma Claudia belong to a later stylistic period than the cameos of Augustus or Tiberius (see fig. 138.12 and fig. 138.13). The large and complex Grand Camée de France (fig. 138.16) was created in the same workshop and may have been commissioned to celebrate, allegorically, Claudius’s adoption of Agrippina’s son Nero in A.D. 50.

Whose Portrait Was on the Cameo before Claudius’s?

The Art Institute’s cameo is less complex both technically and iconographically than either the Gemma Claudia or the Grand Camée de France. The delicate carving of the horizontal layers of the sardonyx gem to model the face and body of the godlike emperor and the straightforward presentation of the figures against the plain background suggest that it was either carved earlier or by a different court workshop. What appears to be the case is that the portrait could have been changed, most likely from Caligula to Claudius.

Caligula ruled only a few years—from March 37 to January 41—and the literary accounts of his personality and actions are overwhelmingly negative. In such a brief period of time, essentially a single official portrait type was created and used for coins (see cat. 37), gems (see fig. 138.11 and fig. 138.17), and bronze and marble sculptures (see fig. 138.10). None of the ugliness of face or character attributed to Caligula in the written record can be seen in his portraits, which continue the tradition of classical youthful beauty of Augustus and Tiberius. At least fourteen cameo and intaglio portraits of Caligula survive—all of which incorporate divine attributes. These should be viewed not as evidence of Caligula’s insanity but as court art, understood on political and literary levels by insiders. Caligula’s portraits show him young and handsome, with a high, broad forehead, straight nose, small mouth, and thin lips that echo the likeness of his great-grandfather Augustus. The hairstyle is a variant of that worn by Augustus—cut low and brushed forward on the neck and arranged in locks over the forehead. On a gem in Vienna (fig. 138.17) Caligula is portrayed as Jupiter. He sits languidly on an elaborate throne decorated on the side with a sphinx with large wings, turning his head to gaze at the goddess seated beside him, who may represent Caligula’s deceased sister, deified as Diva Drusilla Panthea. The gem carver skillfully twisted his torso into three-quarter view, with his raised right arm supporting a cornucopia and his lowered left arm holding a scepter. The long, elegant, almost boneless fingers resemble those on the Art Institute’s gem.

But Caligula’s many portraits were a problem that had to be coped with by the new administration of Claudius. There was a bitter history of Romans censuring and erasing the memory of criminals and enemies of the state. “And yet, when the senate desired to dishonor Gaius, he [Claudius] personally prevented the passage of the measure, but on his own responsibility caused all his predecessor’s images to disappear by night.” So Claudius and the Senate did not officially condemn the memory of Caligula, but bronze and coin portraits could be melted down for reuse, and portraits in stone could be thriftily recycled into images of his great-grandfather Augustus or his uncle Claudius (see fig. 138.10). The portraits of Caligula on valuable gemstones could be salvaged by recarving them to depict the faces of Claudius (see fig. 138.11), Augustus, or Tiberius.

Collecting Gems in Ancient Rome

Collecting carved gemstones—in the form of jewels, vessels, and plaques—was popular in ancient Greece and Rome. They were a form of portable wealth that could not be melted into bullion. Pliny the Elder described the sources and characteristics of more than two hundred gemstones in his encyclopedic Natural History, including their magical properties to heal sickness, protect against poison or the evil eye, and guarantee success in love, athletic contests, and lawsuits. He gave accounts of famous gems, such as Julius Caesar’s gift to Servilia (the mother of Marcus Brutus, one of his assassins) of a pearl worth 60,000 gold pieces, and recorded his personal sight of the stupendously wealthy Lollia Paulina celebrating her marriage to Caligula “covered with emeralds and pearls, which shone in alternate layers upon her head, in her hair, in her wreaths, in her ears, upon her neck, in her bracelets, and on her fingers,” and were worth more than 40 million sesterces. Pliny was more approving of beautiful and valuable gems on public view, whether in military triumphs or dedicated in the museum-like settings of temples:

A collection of precious stones bears the foreign name of “dactyliotheca.” The first person who possessed one at Rome was Scaurus, the step-son of Sulla; and, for a long time, there was no other such collection there, until at length Pompeius Magnus consecrated in the Capitol, among other donations, one that had belonged to King Mithridates; and which, as M. Varro and other authors of that period assure us, was greatly superior to that of Scaurus. Following his example, the Dictator Caesar consecrated six dactyliothecae in the Temple of Venus Genetrix; and Marcellus, the son of Octavia, presented one to the Temple of the Palatine Apollo.

Carved gems made as luxurious imperial gifts reached their high point in size, technical virtuosity, and allegorical complexity during the reign of Claudius. One reason may be that during his long, self-effacing career as an antiquarian (one of his tutors had been the historian Livy) Claudius himself studied and collected gems. Another may be that the highly educated and powerful women in his life, from his grandmother Livia and mother Antonia to his wives Valeria Messalina and Agrippina the Younger, were collectors.

Collecting History

Like many cameos made of and for the imperial family—including the Art Institute’s portrait of Tiberius (cat. 137)—this gem probably survived for centuries as part of the Roman imperial treasury. It may have been transferred about 330 from Rome to the new capital, Constantinople. It could have left Constantinople as a result of either the Venetian sack of that city in 1204, or after the city was conquered by the Turks in 1453. Classical gems then began to be collected avidly by the new ruling families of Renaissance Italy, France, Germany, and Britain. As portable assets they moved from place to place as gifts, part of dowries, and collateral for loans. The Art Institute’s cameo is first attested in the collection of Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel (1586–1646), likely acquired when in 1637 he bought the famous collection of cameos and intaglios formed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by the Gonzaga Dukes of Mantua. It was inherited through a long lineage of descent in 1762 by George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough. The cameo was well known through glass, sulfur (fig. 138.18), and electrotype copies. It was sold when the collection was dispersed at auction in 1899.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s cameo is a portrait of a Roman emperor, created as a work of court art—a small-scale allegory understood and appreciated by the highly educated men and women who ruled the empire. The message—that the emperor could be depicted divinely youthful and with the attributes of the king of the gods—was a form of delicate flattery. The emperor and his powerful associates had access to the finest artists of Rome, and the luxurious works of art they commissioned and presented to each other—gold, silver, textiles, and gems—made for a dazzling court.

Claudius died at age sixty-three on October 13, A.D. 54, perhaps of the infirmities of age, perhaps poisoned by his wife Agrippina. He was given a spectacular funeral that followed the rituals created for Augustus and was officially divinized by decree of the Senate. Work began at once on the imposing temple of the Divine Claudius on the Caelian hill, supervised by Agrippina, who was very active as patron and priestess of the cult—until her son Nero arranged her murder five years later. Parallel to the years-long construction of the temple, at least one court gem was carved with the apotheosis of Claudius, wearing the aegis and flying to heaven on the back of a giant eagle (fig. 138.19). It could be the case that the Art Institute’s gem was recarved from a sycophantic image of Caligula into an image of Divus Claudius at the same time, before Nero began to disown the memories of his domineering mother and adoptive father and predecessor.

Sandra E. Knudsen

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This remarkably beautiful cameo was carved from a three-layered quartz that has been identified as sardonyx and that appears to have been treated to enhance its coloration. The uppermost stratum is brown and has been employed selectively for decorative embellishment within the composition. The figure was carved from the white stratum, which in turn appears over a blue-gray background layer. In the sixteenth century the cameo was set into a gold pendant mount adorned with pearls and enameled decoration. The cameo was carved in relief using engraving tools of different shapes combined with an abrasive slurry. After carving, the surface was highly polished. Under stereomicroscopic examination it is possible to appreciate a number of features: the paths and profiles of several of the carving tools; the delicacy and sensitivity of the carving, in particular the aegis and eagle’s feathers; idiosyncrasies of the engraving and minor mistakes; the rendering of light and shade to enhance the modeling and three-dimensionality; and the surface character of the stone. Most important, close examination suggests that the portrait may have been recarved. The object is in overall stable condition, but a number of small surface anomalies such as chips and losses are apparent. The object has received only one documented conservation treatment during its time in the museum’s collection.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

Primary material: cryptocrystalline quartz (silicon dioxide, SiO2)

The nomenclature of the quartz materials used in glyptic art can be bewildering. Confusion arises from the overlapping and sometimes conflicting vocabularies and attributions of generations of gemologists, mineralogists, archaeologists, and historians. Before the discovery of their common chemical composition in the nineteenth century, the many varieties of quartz were thought to be individual species. Today, the designation quartz groups together these many varieties and includes both the crystalline and compact forms of silica. Crystalline forms, best exemplified by rock crystal, are called macrocrystalline quartzes; the dense and compact forms are called either cryptocrystalline or microcrystalline quartzes. There is no ideal representative of the cryptocrystalline form; these varieties are subsumed under the designation chalcedony. Most often it is the environment of their genesis that is responsible for the differences between the two forms. Broadly speaking, macrocrystalline quartz is formed by the gradual addition of molecules to the crystal surface. Cryptocrystalline quartz forms from a watery solution of colloidal silica.

The cryptocrystalline forms are of two varieties, grainy or fibrous, as revealed by their appearance in thin section. Of the former, some examples are chert, flint, jasper, and heliotrope; of the latter, chalcedony, carnelian, agate, and onyx. Varieties of cryptocrystalline quartzes exhibit a waxy to dull luster, a dull luster on fracture, a refractive index of 1.53 to 1.54, a specific weight in the range of 2.4–2.7 g/cm3, nonsilica impurities of up to 20 percent, water content of up to 4 percent, and a hardness of 6.5 to 7 Mohs. These materials are not minerals in the strictest sense but are textural varieties of quartz, more akin to rocks, and their appearance is governed by the environmental conditions and the nature and amount of impurities present during formation.

The many varieties within these broader classifications can usually be differentiated by observing the colors and patterns and their orientation. Agate is a variety of chalcedony with well-defined bands of at least two colors. There are several subvarieties of agate, one of which is sardonyx. This designation, used by mineralogists, is conferred on a stone that is “distinctly and, usually, straight-banded in white and brown to red layers.” Historians, however, use the term to refer “to cameos (also occasionally to intaglios) when banding is layered or parallel to [the] engraved surface; often artificially dyed.” Both the mineralogical and historical designations apply to this cameo, which was indeed carved from sardonyx. On cursory inspection, the stone consists of at least three layers: a brown uppermost stratum; an underlying semitranslucent, cool-white stratum; and a lowermost blue-gray layer. However, in this variety of sardonyx, often called nicolo, the lowermost layer is black, and the white layer above it is polished so thinly as to make the black appear blue. Inspection of the back of the cameo visible through the open mount does indeed reveal a black substrate (fig. 138.20).

The origin of the stone used for the cameo is unknown. Ancient texts have listed such far-flung locations as Arabia and India as sources, but recent research has demonstrated that this gemstone was available in Thrace, the modern-day Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria.

Secondary materials: mount consisting of gold, pearl, and enamels

In the sixteenth century the cameo was set into a gold frame embellished with pearls and enameled flowers to be used as a pendant. The cameo is rather loose in the mount, which suggests that the mount was repurposed from another gem. The back of the mount is open, exposing the black stone.

Fabrication

Method

Little is available in the way of direct textual evidence from the ancient world regarding the technique of gem engraving. Nonetheless, it appears that over the course of history the process has remained much the same, altered only by the introduction of more modern equipment and materials such as power tools and diamond abrasives.

The metal implements used to cut or carve softer stones such as marble (3 Mohs) are not hard enough to cut gemstones. Copper is 3 Mohs and iron is 5. However, the cutting power of these materials can be greatly enhanced by the addition of a hard abrasive, which, when bound to the end of the tool with a lubricant such as olive oil, actually cuts the stone. Quartz sand is both abundant and capable of cutting a soft stone, but it is clear from the ancient sources that emery, a form of corundum (9 Mohs), from the island of Naxos, was the preferred abrasive of engravers in the ancient world.

A horizontal, bow-powered spindle appears to have been the primary tool employed in the cutting of gemstones. The bow could have been operated by the carver himself or by an assistant. The spindle could also have been operated by wheels or foot pedals for greater speed. Such power, however, would have been unnecessary since excess speed can have undesired consequences: the removal of too much abrasive by centrifugal force and the increased likelihood of losing control. Tools with tips shaped in the form of wheels, cones, or globes, like the burs used in modern dentistry, were employed. The carver applied a slurry of lubricant and abrasive onto the tip of the tool and held the gem to the rotating spindle. Often the gem was mounted onto a post or bat to improve control. Toolmarks visible on unfinished gems provide evidence that the carvers used larger tools for the initial stages of carving and smaller, finer tools for more detailed areas. After carving, the gem was polished with files, wooden implements, leather, felt, and other cloths coated with progressively finer slurries.

Unlike intaglios, which were engraved into the stone to create a negative image, cameos were carved in relief, using the colored layers of the stone to create the contrasting visual effects, such as a pale design over a dark background. Multiple colored bands in the stone could be employed to create even more sophisticated compositions of three or more colors. Rather than functional objects, cameos appear to have been used exclusively for decorative purposes.

The tools and techniques of cameo carving were the same as those used for intaglios, but it is significantly more difficult to carve a cameo. This is chiefly because the carving is done against the convex surface of the stone, so that the tool is always applied at a tangent, resulting in little surface contact. Cameo cutting is meticulous work, and the finest examples display a range of sophisticated effects, such as interplay of light and shadow or translucency in a garment. Furthermore, because the stones are not heterogeneous, their natural variations and the presence of inclusions can cause unforeseen challenges. Master carvers knew how to modify their work in response to such surprises.

Ancient recipes for intensifying or altering the colors of the stones have survived. This was done through dyeing and heating processes but also by immersion in honey, which permeates the microstructure of the stone and when heated changes the color of the stone by caramelization or carbonization.

The ancients were aware of the magnification properties of rock crystal, but no evidence supports the creation and use of lenses to aid in gem engraving. Furthermore, much of the engraving was done blind, since the abrasive slurry darkened during carving as remnants of stone and worn tools mixed with it.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The intensity of the colors, particularly that of the vivid orange-brown, strongly suggests that the stone was treated before carving. In selected areas, the carver retained the brown layer to great effect: to enhance the frame encircling the composition, to add coloration to the eagle’s front wing, and to differentiate the aegis from the body.

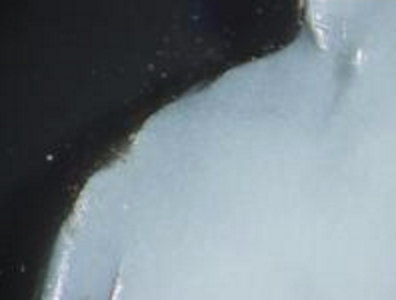

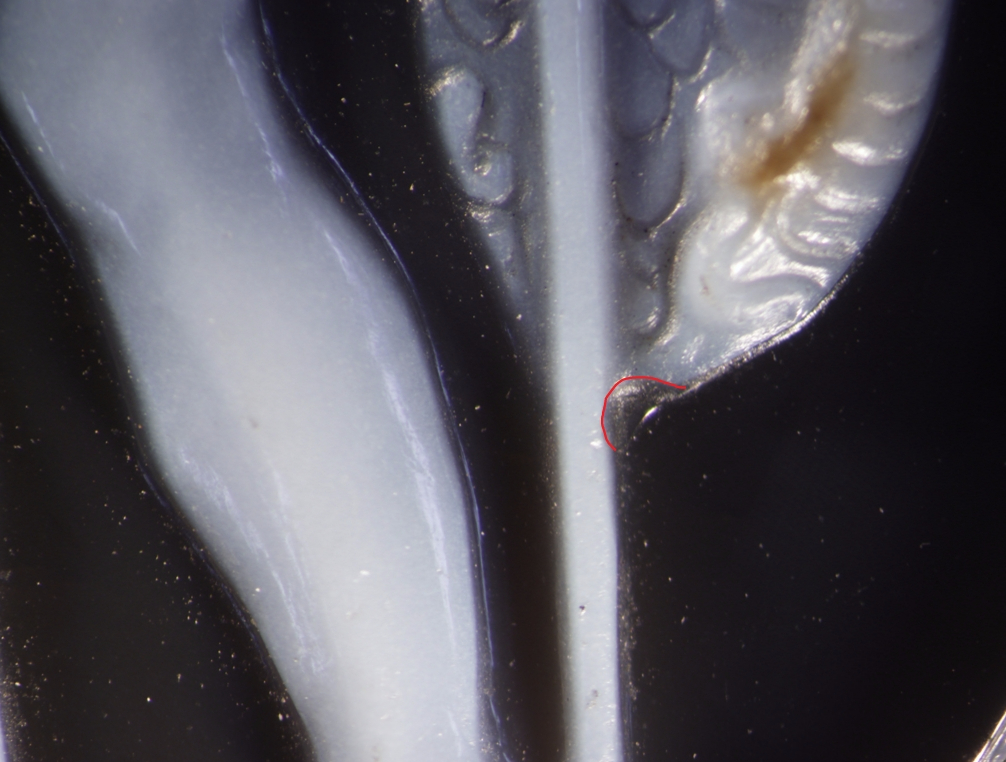

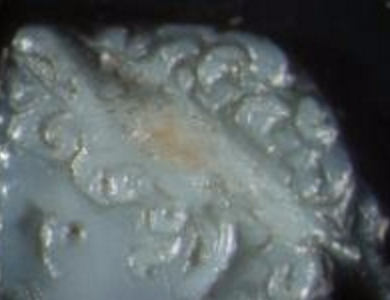

The white stratum is not level with the surface of the dark layer but is instead supported on an extremely thin shelf of it. The carver thoroughly removed the excess dark stone from around the white by running a round implement along the perimeter of the carving, undercutting the surface as he went and creating further contrast between dark and light areas (fig. 138.21).

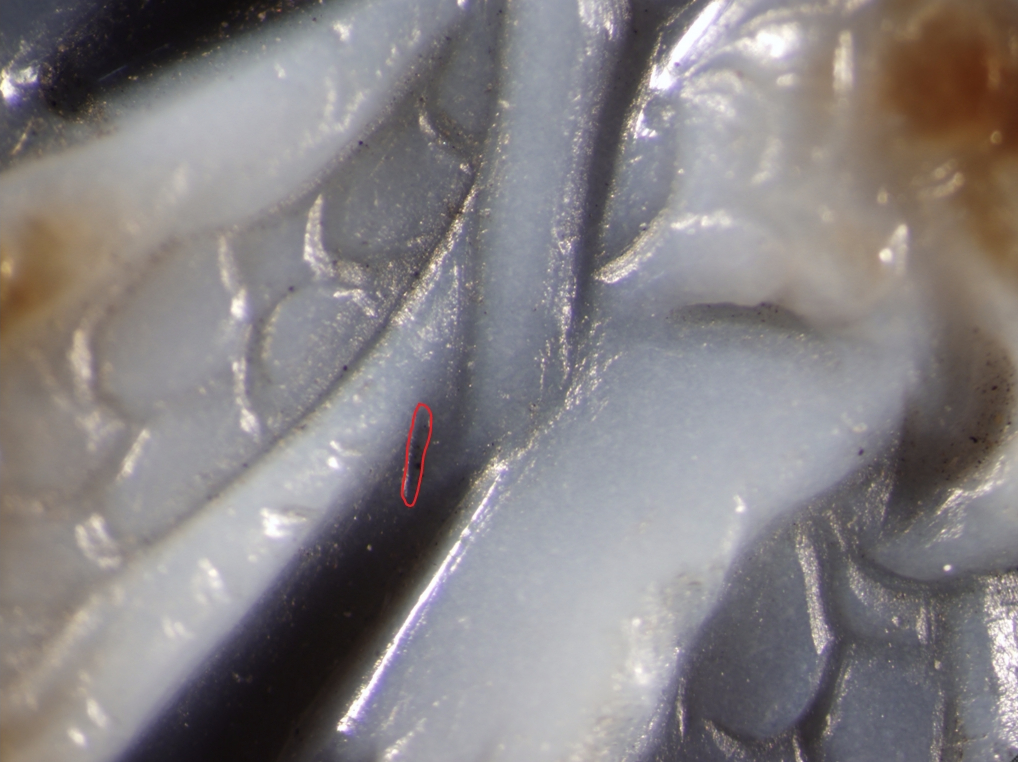

The skill with which the carver exploited the banding of dark and light stone to create strong visual effects is extraordinary. By leaving only the slightest overlay of white over dark, he not only exquisitely modeled the musculature of the torso (fig. 138.22), but also gave the composition a sense of perspective and volume. The eagle’s right wing and leg, the inner surface of the aegis, and the man’s right arm where it rests against the torso all appear to recede into the background, enhancing the three-dimensionality of the image (fig. 138.23).

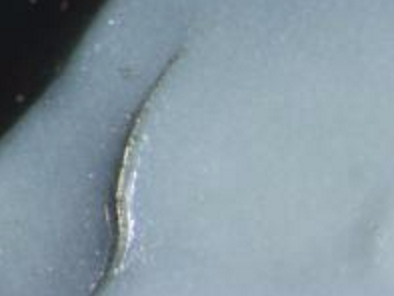

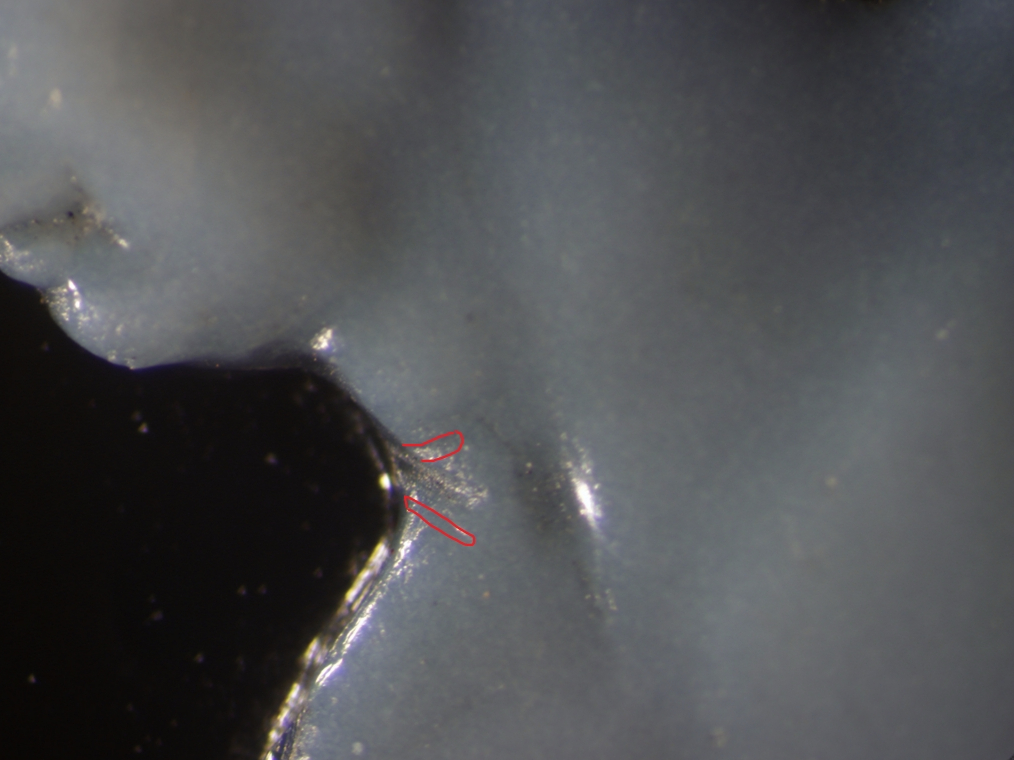

Given the scale and level of detail, a pointed implement might be expected to have been the instrument of choice. However, microscopic examination of the most detailed areas—the aegis, the locks of hair, and the eagle’s feathers—reveals the presence of concave grooves, suggesting that these areas were instead carved with an extremely small tool with a rounded tip. In several places, such as along the line demarcating the groin from the thigh (fig. 138.24), it is possible to see that a pointed tool was used. The tool was applied perpendicular to the stone to create a sharp, triangular point of entry. As the line continued, the carver angled the tool downward to broaden and widen the line toward a rounded terminus. The most clearly defined lines following the contour of the body up into the shoulder on the proper right side have a similar appearance (fig. 138.25).

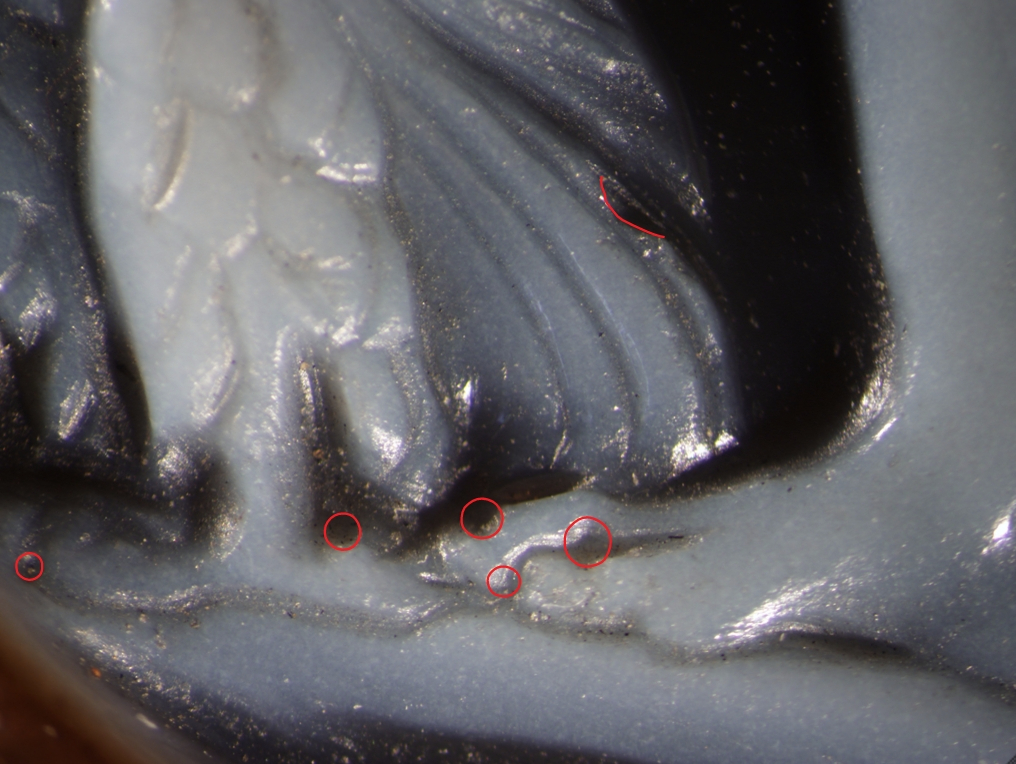

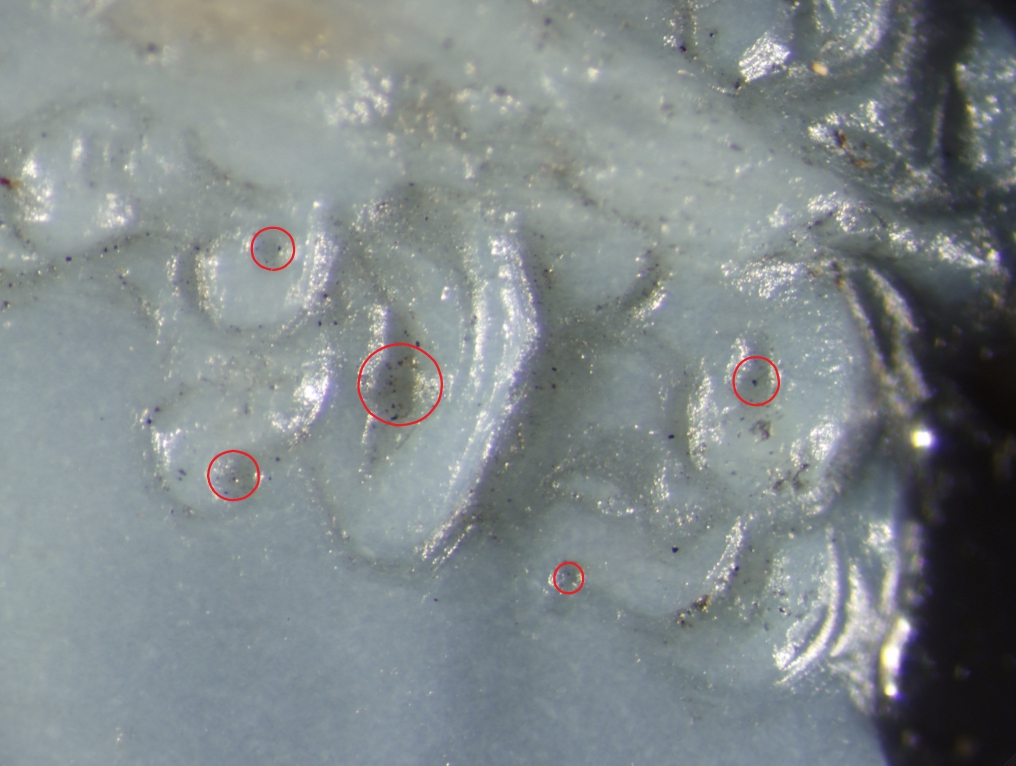

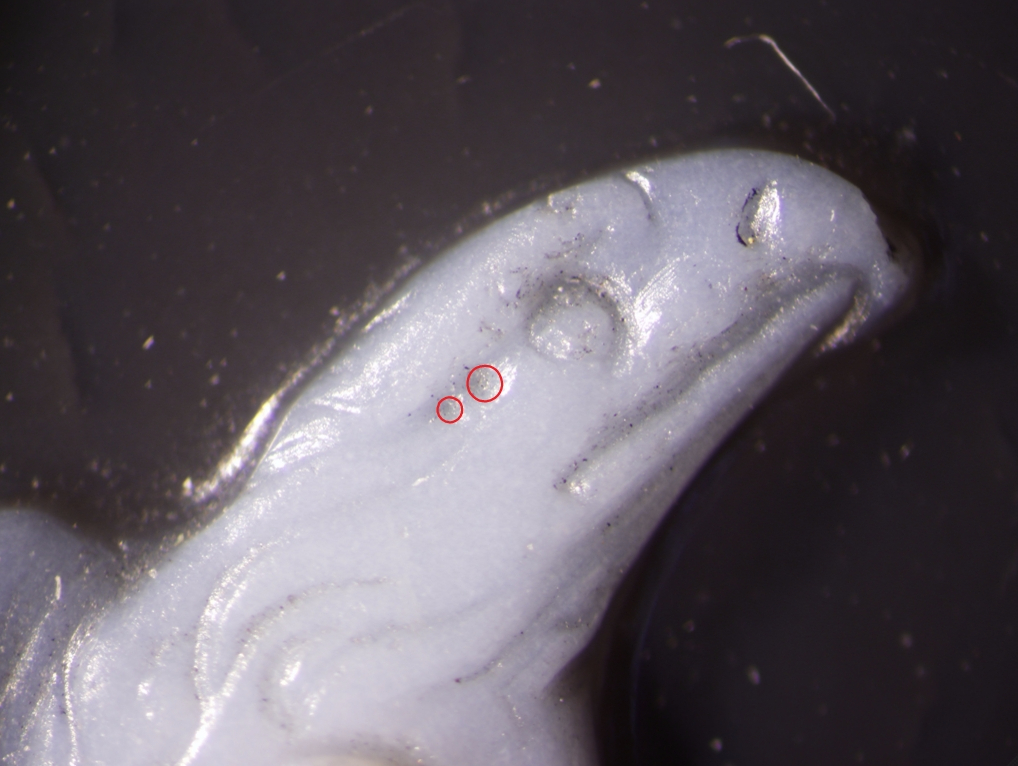

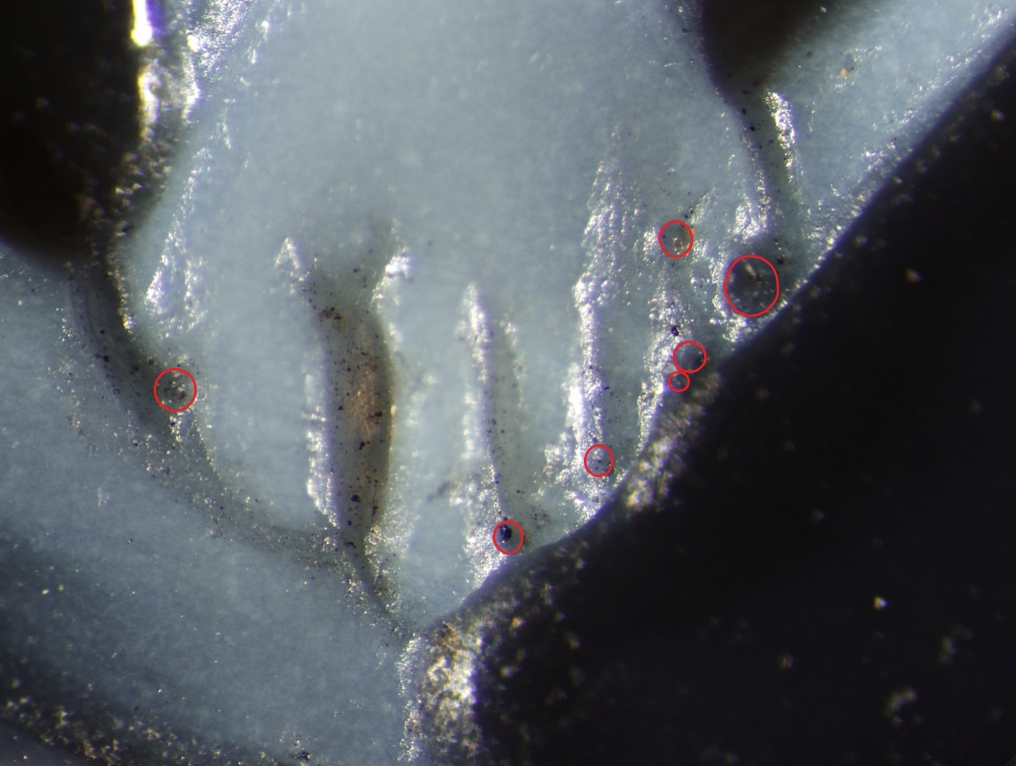

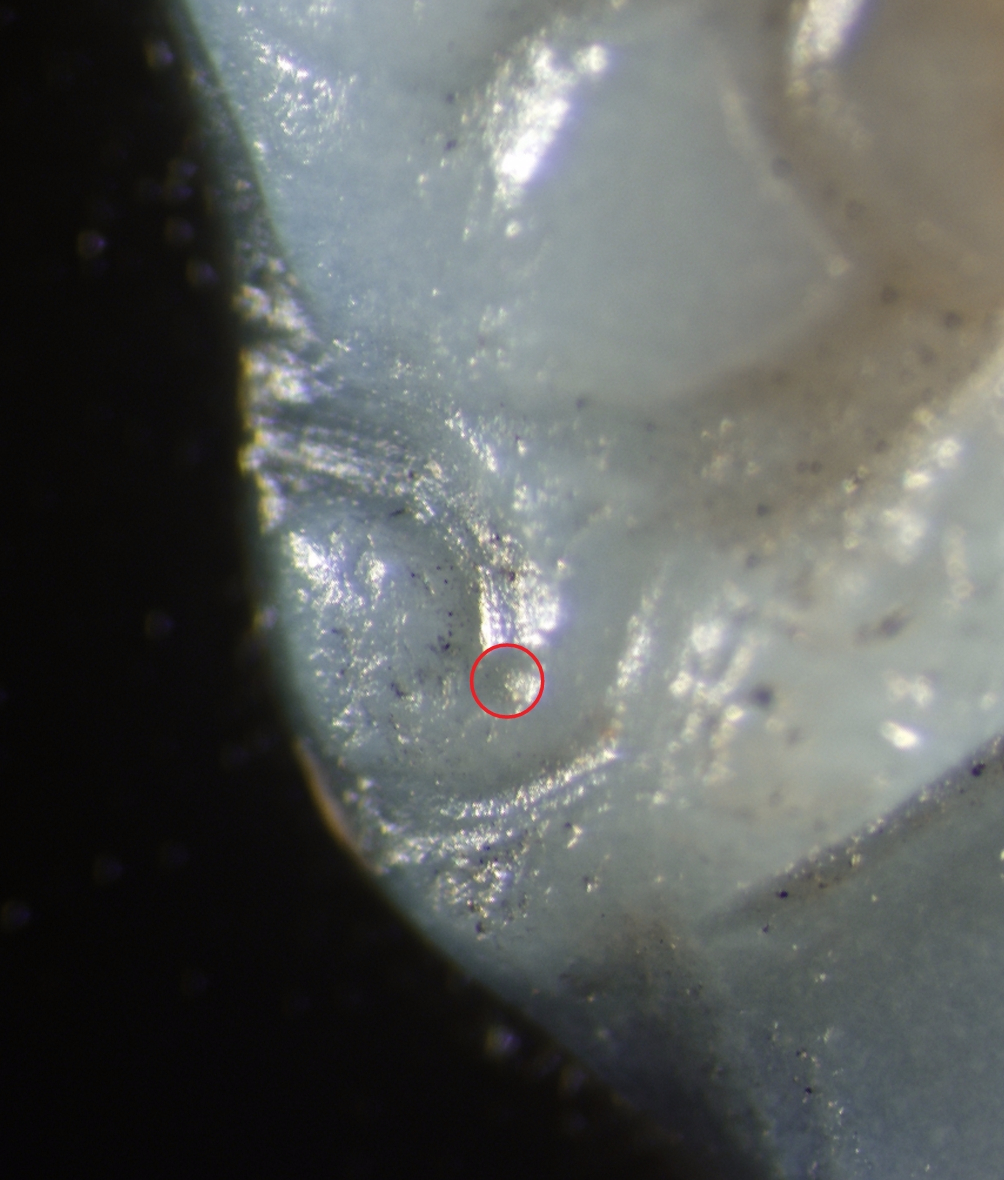

The most curious feature revealed by microscopic examination is the presence of numerous small holes, much like drill holes, throughout the composition. These appear in unusual places: inside the ear and at the ends of several tendrils of hair (fig. 138.26), behind the eagle’s eye (fig. 138.27), within the eagle’s claws and in the toes on both of the man’s feet (fig. 138.28 and fig. 138.29), and in the aegis near the groin (fig. 138.30). These perforations call to mind the techniques used by marble carvers to copy a design or plot out a composition. Perhaps an early stage of the engraving, after a shallow sketch of the general contours had been made, included punctuating the surface with small holes to serve as guide marks or reference points from a copy of another cameo. Alternatively, they may have served as a series of stops intended to alert the engraver to cease carving: as he worked along he would have felt the tool sink into such a marker. This appears to be the case with a line drawn over the kneecap whose path of travel, along which it is possible to see striated toolmarks, is higher than the depression where the line ultimately stops (fig. 138.31). These depressions are appreciable but do not detract from, and in some cases even enhance, the design.

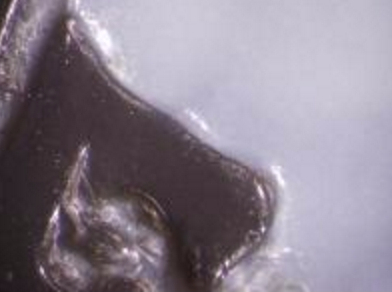

But what of the most incongruous of these perforations, in the center of the face just behind the eye (fig. 138.32)? This hole is visible to the naked eye and is indeed distracting. Surely the carver did not intend to mar the face in such a manner. Furthermore, the carving of the eye directly in front of this hole does not seem to warrant the use of such a stop, let alone one of such disproportionate size. It seems most probable that a hole drilled here for plotting purposes would have been much smaller, considering the importance of the area. Previous examiners and scholars of this cameo have theorized that the face was recarved to transform the visage of Caligula into his successor Claudius. Offered as proof of this assertion are the flattened top of the head, which seems to sit too far forward from the undercut edge (fig. 138.33); strange aspects of the profile and its inconsistent relationships of light and dark; the inharmonious appearance of the chin, jaw, and nose; and the rather coarse treatment of the locks of hair, which is at odds with the handling of the aegis and the eagle’s feathers (fig. 138.34). These are all worthy observations. However, the more compelling evidence in support of recarving is the presence of this hole behind the eye, which could be interpreted as having been a leftover plotting point from the previous engraver.

Further, the modeling of the fingers on the proper left hand is unusual; the pinkie is splayed outward and the ring finger is tucked up under the hand or around the staff (fig. 138.35). The carving of the toes is similarly exaggerated, almost fanciful. Those on the proper right foot are extremely long (fig. 138.28), and the pinkie toe of the proper left foot juts out at a rather severe angle (fig. 138.36). Rather than localized anomalies in carving, these gestures have been interpreted by some scholars as characteristic artifices of the depicted subject.

Within all the incised lines, dark inclusions can be seen (fig. 138.30). These can likely be interpreted as the ingress of carving detritus into the pores of the stone.

Idiosyncratic cutting can be seen in isolated areas. Stray cuts or false starts are present at the join between the neck and shoulder on the proper right side (fig. 138.37) and on the edge of the aegis where it meets the staff near the proper left wrist (fig. 138.38). Where the bottom edge of the hanging portion of the aegis meets the staff, there is a concave depression where the carver removed too much material (fig. 138.39). A double line of carving is present on the bottom edge of the aegis above the legs (fig. 138.40).

At the end of the carving process, the surface was brought to an extremely high polish.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

The carver did not sign the object, and no other identifying marks were observed.

Weight

41.51 g

Condition Summary

The object is in overall stable condition.

Several areas display considerable loss of the white material: the ribbon at the back of the wreath and the portion of the staff above the shoulder (fig. 138.41), the fingers and outside edge of the proper left hand and the nearby proper left edge of the aegis (fig. 138.35), and the front of the wreath (fig. 138.42). The vestiges of a slight brown coloration in this last area of loss makes it likely that the original carving had retained some overlay of brown material, as is the case with the aegis and the eagle’s wing. Brown material also appears to have been lost from the inward fold of the aegis where it hangs down on the proper left side, the result of a network of small pits and chips (fig. 138.43).

The most dramatic area of loss is around the thunderbolt grasped in the proper right hand, which has led to some speculation that the severity of the reduction presents evidence of recutting. However, microscopic examination reveals the very noticeable remains of the undercut edges, which, although jarring and surprising in their depth and appearance, clearly follow the contours of the existing attribute, suggesting that it was once more ample (fig. 138.44) and at some point suffered the same kinds of loss as did the ribbon and the staff. Curiously, this hand appears malformed. It is hard to reconcile that the carving in this area could have been executed by the same individual who so sensitively rendered the modeling of the body and meticulously wrought the delicate features of the aegis and the feathers. Perhaps this entire zone presented a challenge to the carver, either containing intractable inclusions or demonstrating sudden and pronounced changes of direction in the banding that the carver was impelled to overcome.

Lesser chips are also present on the proper right shoulder (fig. 138.45), the eagle’s beak (fig. 138.46) and uppermost tail feather (fig. 138.28), and the bridge of the man’s nose (fig. 138.47). The top edge of the brown ring around the oval frame is also punctuated with tiny chips.

A slight orange-peel texture is visible on the surface of the dark layer, despite its being highly polished. Under high magnification, short, pale, diagonal fibers or striations can be seen within this layer. The surface is uniformly covered with scratches, the majority of which are shallow and faint; others are considerably deeper. Other nicks and small gouges can also be seen overall. The black back of the cameo, visible through the mount, is heavily scratched and retains a previous identification number “73[6]” applied in the center of the cameo using white paint, which is now chipped, making the last character somewhat illegible. The Art Institute’s accession number is painted in red along the bottom edge adjacent to the mount (fig. 138.20).

Conservation History

While in the museum’s collection, the object has received only one documented treatment: a light surface cleaning using both solvent and mechanical means.

Rachel C. Sabino

Exhibition History

Art Institute of Chicago, Renaissance Jewels from the Collection of Melvin Gutman, 1951–62, no cat.

Baltimore Museum of Art, Renaissance Jewels from the Collection of Melvin Gutman, 1962–68, cat. 42 (ill.).

Martin D’Arcy Gallery of Art, Loyola University of Chicago, The Art of Jewelry 1450–1650: A Special Exhibition of Jewels and Jeweled Objects from Chicago Collections, Spring 1975, cat. 43 (ill.).

Mantua, Italy, Palazzo del Te and Palazzo Ducale, Gonzaga: La Celeste Galeria; L’Escercizio dell Collectionismo, Sept. 1–Dec. 8, 2002, no cat.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin im Alten Museum, Antikensammlung, Mythos und Macht: Erhabene Bilder in Edelstein, July 26, 2007–May 25, 2008 (cameo returned Feb. 18, 2008), no cat.

Selected References

Andrew Fountaine, The Arundel Cabinet (London, May 1731), p. 8, case D, no. 13, available at http://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/xdb/ASP/browseBooks.asp.

Rudolf Erich Raspe, A Descriptive Catalogue of a General Collection of Ancient and Modern Engraved Gems, Cameos as well as Intaglios: Taken from the Most Celebrated Cabinets in Europe; and Cast in Coloured Pastes, White Enamel, and Sulphur by James Tassie, Modeller (J. Tassie and J. Murray, 1791), pp. 88–89, no. 965.

M. H. Nevil Story-Maskelyn, The Marlborough Gems, being a Collection of Works in Cameo and Intaglio, formed by George, Third Duke of Marlborough (1870), pp. 1–2, no. 4.

Marlborough Collection, Album of Photographs of the Gems (1875), p. 1, no. 4, available at http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/gems/marlborough/default.htm.

Christie’s, London, Catalogue of the Marlborough Gems: Being a Collection of Works in Cameo and Intaglio, formed by George, Third Duke of Marlborough, sale cat. (Christie’s, London, June 28, 1875), pp. xxi, 2, no. 4.

Christie’s, London, The Marlborough Gems, sale cat. (Christie’s, London, June 26–29, 1899), lot 4.

Adolf Furtwängler, Die antiken Gemmen: Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst im klassischen Altertum (Giesecke & Devrient, 1900), vol. 1, pl. 65, no. 48; vol. 2, p. 302, no. 48 (ill.).

Christie’s, London, Catalogue of an Important Collection of Greek, Roman, and Etruscan Antiquities, and Antique and Renaissance Gems: The Property of Humphrey W. Cook, sale cat. (Christie’s, London, July 14, 1925), lot 203.

Parke-Bernet, New York, Part Two of the Notable Art Collection Belonging to the Estate of Joseph Brummer, sale cat. (Parke-Bernet, New York, May 11–14, 1949), lot 238 (ill.).

M. L. D’Otrange, “A Collection of Renaissance Jewels at the Art Institute of Chicago,” Connoisseur 130, 527 (Aug. 1952), p. 69 (ill.), p. 71.

The Complete Encyclopedia of Antiques, ed. L. G. G. Ramsey (Hawthorn Books, 1962), pp. 506–07, pl. 186, A.

Marie-Louise Vollenweider, Der Jupiter-Kameo (Kohlhammer, 1964), p. 11, n. 17.

Parker Lesley, “Pendant Cameo of an Imperial Figure with Divine Attributes in Gold, Enamel and Pearl Frame,” in Renaissance Jewels and Jeweled Objects from the Melvin Gutman Collection, exh. cat. (Baltimore Museum of Art, 1968), pp. 116–18; p. 117, cat. 42 (ill.).

Parke-Bernet, New York, Medieval and Renaissance Jewelry and Vessels of Rock Crystal and Other Semi-precious Stones: The Melvin Gutman Collection Part II, sale cat. (Parke-Bernet, New York, Oct. 17, 1969), lot 52, pp. 24–25 (ill.).

Donald F. Rowe, “Pendant of a Roman Emperor,” in The Art of Jewelry 1450–1650: A Special Exhibition of Jewels and Jeweled Objects from Chicago Collections, exh. cat. (Loyola University of Chicago, 1975), p. 60, cat. 43 (ill.), back cover (ill.).

Wolf-Rüdiger Megow, Kameen von Augustus bis Alexander Severus (De Gruyter, 1987), p. 202, no. A84, pl. 27.2.

Fulvio Canciani and Alessandra Costantini, “Iuppiter,” in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, vol. 8 (Artemis, 1997), p. 456, no. 408.

Martha McCrory, “Cameos and Intaglios,” in “Renaissance Jewelry in the Alsdorf Collection,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 25, 2 (2000), pp. 56–57, cat. 21 (ill.); pp. 94, 105–06; cover (ill.).

Elizabeth Rodini, “The Language of Stones,” in “Renaissance Jewelry in the Alsdorf Collection,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 25, 2 (2000), p. 24.

Marie-Louise Vollenweider and Mathilde Avisseau-Broustet, Camées et intailles, vol. 2, Les portraits romains du Cabinet des Médailles (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 2003), p. 79.

Gertrud Platz-Horster, “Zwei römische Kaiserkameen der Sammlung Alsdorf in Chicago,” in Mythos und Macht: Erhabene Bilder in Edelstein, ed. Gertrud Platz-Horster (Antikensammlung Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2008), pp. 24–28; p. 86, figs. 5–7.

Boardman, John, with Diana Scarisbrick, Claudia Wagner, and Erika Zwierlein-Diehl, The Marlborough Gems Formerly at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire (Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 35, no. 2 (ill.).

Karen Manchester, Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), pp. 78–79, cat. 16 (ill.), p. 112.

Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago: The Essential Guide (Art Institute of Chicago, 2013), p. 72 (ill.).

Mathilde Avisseau-Broustet, “Cameo Depicting Jupiter,” in The Berthouville Silver Treasure and Roman Luxury, ed. Kenneth Lapatin, exh. cat. (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014), pp. 134–37, fig. 83.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop

Visible Light Microscopy

Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera

Weight

Mettler-Toledo ML3002E digital balance