Cat. 137

Fragment of a Cameo Portraying Emperor Tiberius

Cameo: Roman, A.D. 14/20; mount: Italian or French, 16th century

Cameo: sardonyx; mount: gold, pearl, enamel; 8 × 4.8 × 1 cm (3 1/8 × 1 7/8 × 3/8 in.)

Inscription on mount: ΑΕΙΘΑΛΕΣ (evergreen)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Marilynn B. Alsdorf, 1992.297

Tiberius was fifty-five years old when he became the second Roman emperor, but his portraits always depict a younger man. The Art Institute’s cameo profile portrait conforms to this tradition, initiated by the divinely youthful portraits of his stepfather and predecessor Augustus. On a gold coin first minted in A.D. 14, soon after Augustus died and was deified by decree of the Senate (an honor symbolized by the star above his head), his portrait is on the obverse and a somewhat smaller portrait of the new ruler Tiberius is on the reverse (fig. 137.1). Both men wear the corona triumphalis, the gold laurel crown awarded for military victories over enemies of Rome. The inscriptions emphasize Tiberius’s relationships to two new gods, Augustus—his adoptive father—and Julius Caesar—his adoptive grandfather through Augustus. The symbolism recognizes that Tiberius owed his elevation to Augustus.

On the cameo portrait, the beak-like nose and the noticeable furrows around the nose and mouth are hints of maturity, even age. The small mouth with its protruding upper lip, pointed chin, and wide eyes are distinctive facial features. Identification as Tiberius is secured by the overlapping rows of comma-shaped locks of hair combed over the forehead and across the neck. The only part of this cameo that survives is the head and part of the neck. The portrait is of extraordinarily high quality and remarkably well preserved. It was carved from the upper white layer of a hardstone with horizontal brown and white bands so that the head stands out against the darker background. The head is a fragment, originally part of a larger cameo, perhaps a gem with only the portrait or perhaps a composition of multiple figures. It must be presumed that the Renaissance metalsmith designed the gold capsule to fit snugly around the extant fragment, but it cannot be ruled out that some of the surviving background may have been removed or modified to create a more regular, compact presentation within the setting. Based on other gem and coin portraits, the jeweler or his patron knew that the oak wreath had lost its ribbon, tied in a looped bow with streamers, so white enamel was set into the mount to complete the image—although the ribbons should trail farther down the neck. The jeweler aligned the eye and ear horizontally and the base of the throat, ear, and crown of the head vertically; the result is a somewhat downward angle of the head and gaze compared to profile portraits on coins.

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus

Tiberius Claudius Nero (42 B.C.–A.D. 37; r. A.D. 14–37) was the stepson of the first Roman emperor, Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14). He was born into the patrician Claudian family ([glossary:gens] Claudia) as the older son of Augustus’s wife, Livia Drusilla, by her first marriage. He married Augustus’s only child, Julia the Elder, in 11 B.C.; their only child died in infancy. In A.D. 4, at the age of forty-five, Tiberius was formally adopted by Augustus into the Julian family (gens Iulia), becoming Tiberius Julius Caesar and heir to sole rule of the empire.

Pliny the Elder, who was born in A.D. 23, so young enough to know people who remembered Tiberius, called him “the gloomiest of men” (tristissimus hominum). The epithet was based on a personality apparently paralyzed by anxiety of doing the wrong thing as he endeavored to continue the policies of Augustus. Despair and fear of assassination drove him to leave Rome in A.D. 26 and never return. The paucity of monuments from his more than twenty-two years of rule is notable—Tiberius completed buildings begun by Augustus, but the only new commission was the grand temple of Divus Augustus in Rome, which was not dedicated until after his own death. Moving from villa to luxurious villa on the island of Capri for the last eleven years of his life, he surrounded himself with a few close friends, philosophers, and soldiers. The rumors of drunkenness and debauchery that make sensational reading in the later Annals of Tacitus and biographies of Suetonius have been somewhat discredited. Willfully forgotten during the brief reign of his young nephew Gaius (Caligula; r. 37–41), Tiberius was rehabilitated by the next emperor, Claudius (r. A.D. 41–54), as his uncle and the successor of Augustus.

Imperial Portraits

After he assumed power as the first emperor, Augustus employed artists to promote political and social goals by commissioning idealized portraits of himself and his family that show them not simply as living people but as the inspired descendants of a god, Divus Julius. Portraits had always been important to ancient Romans as enduring images of not just the likeness but also the individual essence of a man or woman. The intention was educational, to model behavioral virtues for family, friends, and clients. During the reign of Tiberius, Valerius Maximus wrote how “the effigies of a man’s ancestors [effigies maiorum] with their labels [titulis] are placed in the first part of the house in order that their descendants should not only read of their virtues but imitate them.”

Writing a century later, the biographer Suetonius recorded this physical description of Tiberius, whom he did not greatly admire:

Tiberius was strongly and heavily built, and above average height. His shoulders and chest were broad, and his body perfectly proportioned from top to toe. . . . He had a handsome, fresh-complexioned face, though subject to occasional rashes of pimples. The letting his back hair grow down over the nape seems to have been a family habit of the Claudii. Tiberius’s eyes were remarkably large and possessed the unusual power of seeing at night and in the dark, when he first opened them after sleep; but this phenomenon disappeared after a minute or two. His gait was a stiff stride, with the neck poked forward, and if ever he broke his usual stern silence to address those walking with him, he spoke with great deliberation and eloquent movements of the fingers.

A sequence of several portrait types has been identified as Tiberius’s official portrait iconography. Art historians argue about the precise occasions, but the changes reflect not his aging (as a photograph would today) but a series of key events in his public life, including his military career, his marriage to Augustus’s daughter Julia in 11 B.C., and his adoption as Augustus’s son and investiture with increased authority in A.D. 4. All portraits show him with the soft features and full head of hair of a younger man, like Augustus, although Tiberius’s forehead and skull are broader, his eyes rounder (like those of his mother, Livia), his nose more aquiline, his upper lip protruding slightly, and his chin delicately rounded. The hair is combed in comma-shaped locks across his forehead in manner similar to that of Augustus, but the precise arrangement and layering of the forks of hair over his eyes change from type to type. Variations in coin portraits include the heavier features of the portrait on the gold coin shown in fig. 137.2. On this and most coins, Tiberius wears the laurel wreath. The neckline indicates that he is shown in [glossary:heroic nudity], wearing neither civil nor military garb. First struck by the mint of Lugdunum (Lyon) soon after March A.D. 15, the inscription on the reverse gives his new title, PONTIF MAXIM ([glossary:pontifex maximus]) around an image of the goddess Pax (peace) that some scholars identify as a portrait of his mother (see, e.g., cat. 36, Aureus (Coin) Portraying Emperor Tiberius).

The Art Institute’s cameo portrait of Tiberius is small (hairline at forehead to chin: 18.5 mm), and both the profile and the presence of the oak wreath make it difficult to be certain about the exact arrangement of locks of hair over the forehead. However, the carving is very precise and there are definitely two layers of hair, a shorter fringe resting lightly on top of the curved locks touching the forehead. This characterizes a portrait type created either shortly before or soon after Tiberius became emperor. The best-preserved marble example gives the type its name: the Copenhagen 624 type (fig. 137.3).

A slightly different portrait type—called the Chiaramonti type after a statue in the Musei Vaticani (fig. 137.4)—was created late in the reign of Tiberius and continued to be used for posthumous portraits, sometimes wearing the oak wreath. Tiberius was never deified by his successors—perhaps because the ceremony was so new for Augustus or perhaps because Tiberius died much maligned by his subjects—but images of him filled out statuary groups dedicated to the goddess Roma and the imperial family in civic centers, theaters, and temples. His immediate successors Caligula and Claudius piously included him in dynastic monuments large and small.

Imperial Cameo Portraits

Cameo gems were carved in low relief and served as small, portable sculptures, sometimes set in rings or brooches or larger mounts. Many portraits of living and deceased emperors must have existed and been displayed or worn as symbols of loyalty. The practice could be carried to extremes, both positive and negative. In the later years of the reign of Tiberius, a person could be accused and tried for a crime subject to the death penalty if seen wearing a ring or carrying a coin with the image of the deified Augustus or of the living Tiberius into an impure place like a toilet or a brothel. Such an event is described by the Stoic philosopher Seneca, who served as tutor and later adviser to the emperor Nero (r. 54–68). Written between A.D. 56 and 62, the essay On Benefits mentions a portrait of Tiberius on a gem in the context of the noble deed of a slave to help his master:

In the reign of Tiberius Caesar, there was a common and almost universal frenzy for informing. . . . One Paulus, of the Praetorian guard, was at an entertainment, wearing a portrait of Tiberius Caesar engraved in relief upon a gem. It would be absurd for me to beat about the bush for some delicate way of explaining that he took up a chamber-pot, an action which was at once noticed by Maro, one of the most notorious informers of that time, and the slave of the man who was about to fall into the trap, who drew the ring from the finger of his drunken master. When Maro called the guests to witness that Paulus had dishonored the portrait of the emperor, and was already drawing up an act of accusation, the slave showed the ring upon his own finger. Such a man no more deserves to be called a slave than Maro deserved to be called a guest.

In addition to the Art Institute’s cameo, carved hardstone portraits of Tiberius have been identified in collections in Berlin, Florence, Naples, New York, Vienna, and Paris. Among the examples carved early in his reign, the Berlin gem (fig. 137.5) shows Tiberius wearing a laurel wreath, carved in low relief on amazonite (green feldspar); the arrangement of the hair closely resembles the Copenhagen 624 type. Tiberius and his mother, Livia Drusilla (adopted into the imperial family as Julia Augusta after the death of Augustus), appear together carved in a double, or jugate, portrait, at about the same time, certainly before Livia’s death in A.D. 29 (fig. 137.6). Tiberius wears a laurel wreath; Livia wears a crown of poppies and wheat ears, associating her with Ceres, goddess of agriculture. The gem carver emphasized the relationship of mother and son with the parallel contours of the profiles.

In addition to the low-relief cameos, profile portraits of Tiberius were carved in intaglio (fig. 137.7). Several types of glass gems show frontal or profile portraits of Tiberius, including the phalera (glass medallion) shown in fig. 137.8. Phalerae with single and multiple portraits of members of the imperial family were inexpensive to reproduce and awarded as badges to be worn on uniforms to reward and encourage loyalty to the emperor as leader of the Roman army. Other glass gems imitated hardstone cameos.

Date

It is unusual that on the Art Institute cameo Tiberius wears the [glossary:corona civica], a wreath of oak leaves, with their characteristic irregular-lobed margins, and acorns. The oak wreath was one of the highest military honors of ancient Rome, awarded for having saved the life of a fellow citizen on the battlefield, killed the enemy, and held the line of battle. In 27 B.C., when the Roman Senate formally invested Augustus with the powers that made him the first emperor, he was voted the corona civica as a symbol of having saved the lives of all citizens by ending the civil wars—although he declined the honor until 2 B.C., and he insisted that it had been conferred not only by the Senate but also by the [glossary:equestrian] order and the people. Many portraits show Augustus wearing the oak crown. Tiberius was voted all of the same honors at the time he succeeded Augustus in A.D. 14, but he refused the corona civica—and many other extraordinary privileges and titles—when he accepted the powers and responsibilities of government. As a long-serving army commander, Tiberius may have refused the crown because unlike some courageous Romans—including Julius Caesar—he had not earned the honor in battle. The presence of the oak wreath suggests that this cameo was carved soon after the death of Augustus, before Tiberius’s intentions were made known. Posthumous portraits of Tiberius often wear the corona civica, honoring him as the savior of Roman citizens, including the seated statue in the Claudian dynastic group set up about A.D. 45–50 in the theater at Cerveteri, but the cameo portrait’s arrangement of locks of hair in the early imperial hairstyle and the delicate wrinkles around the nose and mouth are those of a living middle-aged man and not the youthful, idealized features of the posthumous portrait type.

Always Prized . . . Never Buried: Collecting Gemstones in Antiquity and After

In his encyclopedic Natural History, published about A.D. 77, Pliny the Elder described more than two hundred gemstones, including their ability to heal sickness, protect against poison, or guarantee success in love, athletic contests, or lawsuits. He identified the development of the Roman passion for collecting carved gemstones:

A collection of precious stones bears the foreign name of “[glossary:dactyliotheca].” The first person who possessed one at Rome was Scaurus, the step-son of Sulla; and, for a long time, there was no other such collection there, until at length Pompeius Magnus consecrated in the Capitol, among other donations, one that had belonged to King Mithridates; and which, as M. Varro and other authors of that period assure us, was greatly superior to that of Scaurus. Following his example, the dictator Caesar consecrated six dactyliothecae in the Temple of Venus Genetrix; and Marcellus, the son of Octavia, presented one to the Temple of the Palatine Apollo.

Like many surviving cameos made of and for the Julio-Claudian imperial family—including the intact cameo of the emperor Claudius as the god Jupiter (cat. 138)—the Art Institute’s cameo portrait of Tiberius probably survived by being moved from one treasury to another. It may have been transferred about A.D. 330 from the palace of the emperors in Rome to the new capital Constantinople. It could have left Constantinople as a result either of the Venetian sack in 1204 and subsequent Latin Empire of Constantinople, or after the city fell to the Turks in 1453. Carved gemstones began to be prized by the new ruling families of Italy, France, Germany, and Britain. Some entered church collections, like the famous Treasury of San Marco, Venice. Others moved from place to place as gifts, part of dowries, and collateral for loans.

A Renaissance Jewel

From the Renaissance through the eighteenth century, wealthy, educated people collected, copied, studied, published, and argued about ancient gems. Unlike architecture, painting, and sculpture, these miniature works of art and coins had often survived intact and in large numbers. They could be collected in several forms—as costly originals but also as reproductions, casts, or impressions in wax, plaster, sulfur, or colored glass paste—although this cameo is not documented in any of the published collections. Gem images were recognized by antiquarians and artists as primary sources of information to supplement the literary record of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian myths, portraits, and history.

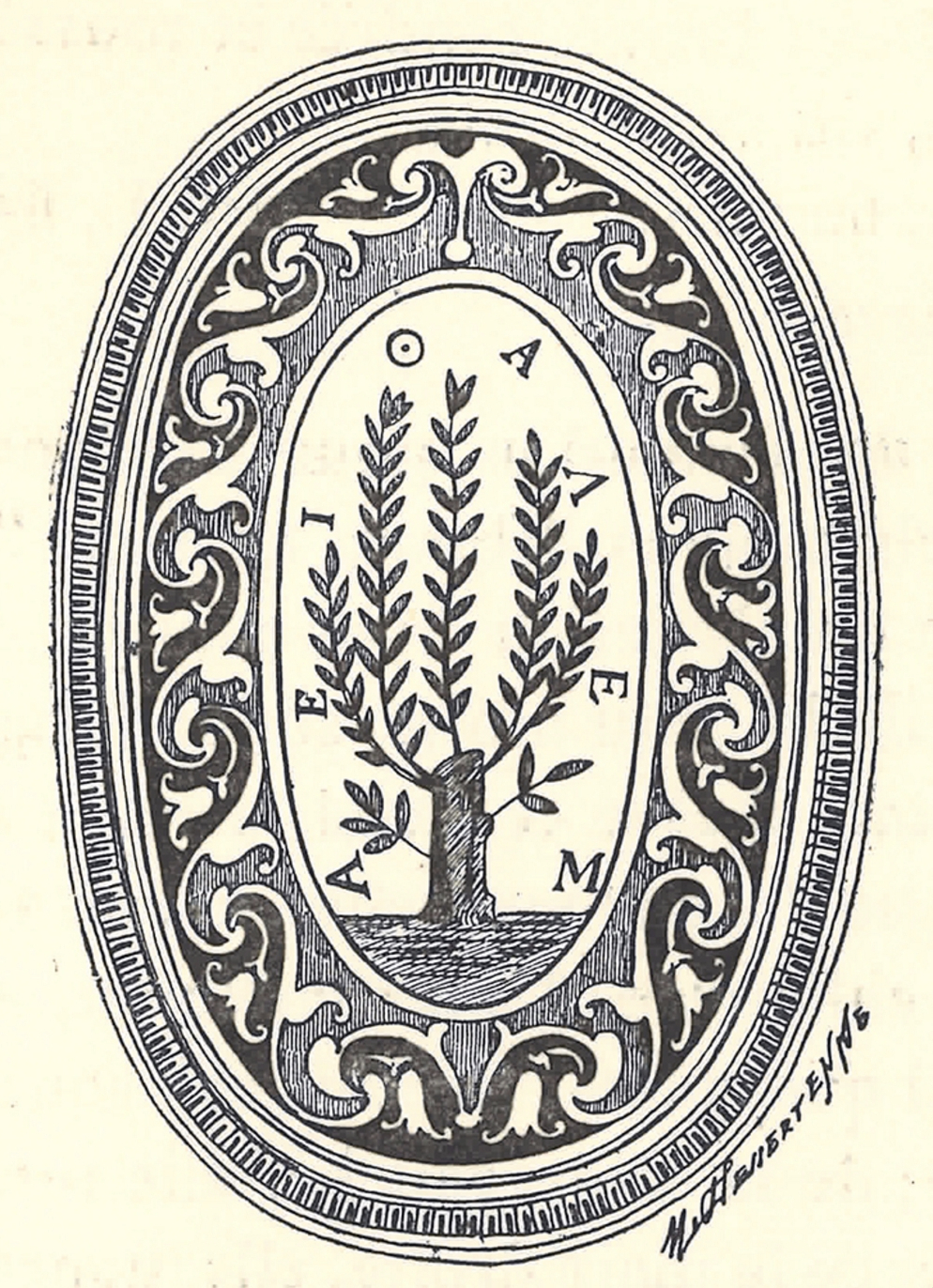

About 1550 this fragmentary cameo portrait was encased in a gold mount called a [glossary:commesso], named for the challenging technique by which hardstones, metal, and enamels are “committed,” or joined like a jigsaw puzzle. The commesso technique flourished in the luxurious atmosphere of the sixteenth-century courts of François I and Henri II, where Italian and French artists collaborated. The front and side of the capsule are decorated with gold moresque tendrils surrounded by dark blue enamel. On the back of the capsule is the cut stump of a laurel tree sprouting new branches, an emblem called a broncone, and the Greek word ΑΕΙΘΑΛΕΣ (evergreen, ever-flourishing), a loose translation of the Latin motto semper viret (it always flourishes), known to have been used by the Florentine statesman Lorenzo I de’ Medici (fig. 137.9). The laurel tree (in Latin, laurus) was one of the personal emblems of Lorenzo (Laurentius) “the Magnificent” (1449–1492)—a personal echo of the laurel wreaths and branches that honored ancient Romans—but Lorenzo used several different mottos, including the French le temps revient (time returns).

Lorenzo ardently collected classical gems (including the greatest of all surviving carved hardstone jewels, the Hellenistic Greek Tazza Farnese, which he acquired in 1471 and which is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Naples) and enticed gem carvers to move to Florence and teach the techniques. He proudly marked many gems and hardstone vases he owned with an incised symbol—LAV.R.MED. His descendants continued to collect gems. According to the sixteenth-century historian Giorgio Vasari, Lorenzo II di Piero de’ Medici (1492–1519) “had for his device a Broncone—that is, a dried trunk of laurel growing green again with leaves, as it were to signify that he was reviving and restoring the name of his grandfather.” Three more cameos have been identified mounted as pendants with the reverse showing variations on images of a laurel with new growth together with the classical Greek motto ΑΕΙΘΑΛΕΣ (fig. 137.10, fig. 137.11, and fig. 137.12). It is generally disputed whether any of these pendants could have been made as early as the time of Lorenzo the Magnificent. In the next generation of the Medici family, truncating dynastic hopes, Lorenzo II died a few days after the birth of his only child, Catherine de’ Medici (1519–1589); at age fourteen she married Henri, the heir of François I, reigning as queen of France from 1547 to 1559 and, after her husband’s death, as regent (and, briefly, mother-in-law of Mary Queen of Scots). Catherine adopted the rainbow as her personal emblem, but she inherited and brought to France a collection of intaglios and cameos. The French style of the commesso and the documentation of one of the Medici pendants in the former French royal collection together suggest a French provenance for the Chicago cameo mount. However, the cameo is not documented until it was acquired by Alexander Hamilton (1767–1852), the future 10th Duke of Hamilton, while he was Marquess of Douglas and serving as British ambassador to the court of Tsar Alexander I in Saint Petersburg in 1807–08.

Conclusion

The Art Institute’s cameo is a portrait of the emperor Tiberius, a small-scale, luxurious work of art made to display within the court circles of the Roman Empire. The fragment preserves only the head, so it is impossible to know whether it was originally a small portrait gem or part of a larger, allegorical composition. The unusual oak wreath suggests that the portrait gem was carved very soon after Tiberius succeeded Augustus in September A.D. 14, before Tiberius made it clear that he did not wish to be awarded this high military decoration or other honorary titles held by Augustus. What the cameo preserves is an expertly carved and multilayered political statement: Experienced and divinely inspired, Tiberius is the worthy successor of the god Augustus.

Sandra E. Knudsen

Appendix

A Note on the Inscription

ΑΕΙΘΑΛΕΣ (AEITHALES) “evergreen,” literally, “ever-flourishing”

Although so very brief, the Greek inscription in Renaissance enamel that appears on the reverse of this cameo (as well as on the mounts of three others like it), has long proved a source of some confusion—apparently from the very time of its commissioning (see fig. 137.9). The word intended is ΑΕΙΘΑΛΕΣ (AEITHALES): a not particularly common ancient Greek adjective, taken from the verb θάλλω (thallō), “to flourish, bloom, or thrive,” in conjunction with the adverb ἀεί (aei), “always.” It is a term used in Greek to denote evergreen plants. These gems, with their image of the cut-back laurel stump that thrives again, have long been connected with the ruling Florentine Medici family. This is both because the laurel was an impresa (an emblem or device with a motto) of Lorenzo de' Medici and his descendants, and also because the Greek motto accompanying it is an approximate translation of the Latin phrase semper viret, “it always flourishes”—a phrase known to have been associated with Lorenzo I. In fact, the Greek adjective offers a still more direct translation of two other versions of the Medici Latin motto that are attested on the ceiling tiles of the Via Lata palace: semper virens, “ever-flourishing, ever-green,” and semper florens, “ever-flourishing, ever-flowering,” both of which senses are captured by the Greek.

Created at a time when the final fall of Constantinople had made Greek learning accessible in the Latin West after a hiatus of centuries, this Greek motto may have been designed as an erudite alternative to the Latin, calculated to impress. Indeed, as the ending of the adjective here is given in the neuter case, to agree with the thing represented—τό δένδρον (to dendron), “the tree”—this Greek inscription was evidently designed by a person who had a reasonable facility with the language and its workings. Whether the Medici servant who oversaw the creation of the exquisite painted backing to this Roman cameo—or even the powerful Medici patron himself—knew quite so much of the exotic, highly cultured language to which this gem made its claim, however, is a matter much more in doubt.

Just Enough Greek to Be Dangerous (or at Least Wrong)

The spacing of the letters in this inscription is decidedly peculiar. Inserting a break into the middle of a word in order to better arrange the characters around a central visual device was a common enough practice from the ancient world on, and is widely attested on Roman coins. Indeed, the cameo bearing this inscription in Florence is arranged in just this manner (see fig. 137.12). The other two examples—in Paris and Munich—present the adjective as a single word (see fig. 137.10 and fig. 137.11). Thus the Chicago example is unusual, both for the genre, and for this group, in interrupting the flow of the letters, and even of the syllables—entirely preventing their orderly progression around the circumference of the mount.

This arrangement of the inscription has caused sufficient confusion that in two mid-twentieth-century publications of this cameo, the text is mistakenly transcribed backward as THALES AEI. More commonly, accounts of this gem and its peers have been correct in their ordering of the letters, but have often still erred by introducing a break in the word, giving AEI THALES—perhaps in an analogy with the Latin semper viret. Indeed, this may even have been the mistake of whichever Medici administrator was overseeing the penning of the inscription on the back of the cameo. The mistake seems to be rooted in the Renaissance itself.

Taken as a group, the four cameo mounts with the Greek motto together point to a Medici servant who had some facility with the ancient languages, but not enough to be certain that what was being inscribed on these sister cameos was in fact correct. The inscription on the Munich cameo ΑΙΕΙΘΑΛΕΣ (AIEITHALES) is particularly interesting in this regard, as it conflates the Greek spelling of ἀειθᾰλές (aeithales) with that of the Latin plant name that is derived from it—aithales (evergreen house leek). The inscription in Munich thus gained an extra letter I, as it included this letter from both the Latin and Greek terms! The inscription of the Florence cameo is also interesting for the enamel dots that clearly appear over the letters A, I, and the final E; these appear to be attempts at sophistication in including the breathing and accent marks of the Greek ἀειθᾰλές, but, if so, they are set over the wrong vowels. There is some creative inaccuracy in this group of Greek devices.

In light of this, it could be supposed that the servant overseeing the inscription of the mount for the Chicago gem had facility enough to recognize AEI (always) as the commonly occurring Greek word it is, and inaccurately assumed that THALES was a verb that should stand alone to accompany it. Arguably, he read the final letters “ES” in analogy with the Latin second person future ending of the third conjugation, and so imagined that a promise “You will always flourish” was intended; alternatively he may have interpreted it in line with the Latin first conjugation subjunctive, and so read the inscription as a wish: “May you always flourish!” Though Greek was newly fashionable as the hallmark of high culture, these gems from a collection as prominent as that of the ruling family of Florence clearly show that real facility with the language remained the preserve of only a very few.

What is most significant about the mistakes in the Greek in this group of inscriptions, however, is that they reaffirm the accuracy of a Renaissance dating for the mounts as a whole, and so disavow the claim made by certain scholars that the settings held in Munich and Chicago are eighteenth-century creations, inspired by the gem mount still in Florence. While the front enameling and the edge frame with the hanging pearl of the Chicago gem may be accepted as a sixteenth-century French addition, the interior backing plate with the impresa and motto, I would argue, surely stems from an even earlier, Italian Renaissance context. There could be little motivation for an eighteenth-century copyist of a Renaissance gem setting to veer from his model by introducing new errors and idiosyncrasies into the Greek—particularly as this was a time when the language was vastly more widely studied and known. Moreover, the oddities of these simple Greek inscriptions argue for their comparatively early date, in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries when the language was newly appreciated—and considered impressive—but few had great mastery over it. I suggest that the rear inscription plates should together be assigned to an Italian Renaissance context.

The question remains: did no one in the Medici family object to these creative peculiarities in their motto, or know enough Greek to detect them? It seems probable that it did not matter. The Greek was evidently part of the gilding of these jewel settings. Just enough to impress was the order of the day; accuracy was optional.

Nicola Barham

Technical Report

Technical Summary

This splendid cameo portrait is a fragment of a once-larger gem carved from a layered quartz that has been identified as sardonyx. The laureate head faces to the proper right and was carved from the white stratum; the brown stratum served as the ground. In the sixteenth century the existing fragment was fashioned into a [glossary:commesso] pendant, at which time its missing features were reinstated in enamel. The mount fully encases the stone fragment, obscuring a view of the back of the stone. The fragmentary nature of the original cameo, coupled with how it was obscured by the later mount, also makes it difficult to ascertain whether or not the color of the stone was altered before engraving. The cameo was carved in relief using engraving tools of different shapes combined with an abrasive slurry. After carving, the surface was highly polished. Under [glossary:stereomicroscopic] examination it is possible to appreciate a number of features: the paths and profiles of several of the carving tools; the delicacy and sensitivity of the carving, in particular the hair and oak wreath; idiosyncrasies of the engraving and minor flaws in cutting; and the surface character of the stone. The object is in overall stable condition, but a number of minor surface anomalies such as cracks, chips, and losses are present. The object has received only one documented conservation treatment during its time in the museum’s collection.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

Primary material: cryptocrystalline quartz (silicon dioxide, SiO2)

The nomenclature of the quartz materials used in [glossary:glyptic] art can be bewildering. Confusion arises from the overlapping and sometimes conflicting vocabularies and attributions of generations of gemologists, mineralogists, archaeologists, and historians. Before the discovery of their common chemical composition in the nineteenth century, the many varieties of quartz were thought to be individual species. Today, the designation quartz groups together these many varieties and includes both the crystalline and compact forms of silica. Crystalline forms, best exemplified by rock crystal, are called macrocrystalline quartzes; the dense and compact forms are called either cryptocrystalline or microcrystalline quartzes. There is no ideal representative of the cryptocrystalline form; these varieties are subsumed under the designation chalcedony. Most often it is the environment of their genesis that is responsible for the differences between the two forms. Broadly speaking, macrocrystalline quartz is formed by the gradual addition of molecules to the crystal surface. Cryptocrystalline quartz forms from a watery solution of colloidal silica.

The cryptocrystalline forms are of two varieties, grainy or fibrous, as revealed by their appearance in thin section. Of the former, some examples are chert, flint, jasper, and heliotrope; of the latter, chalcedony, carnelian, agate, and onyx. Varieties of cryptocrystalline quartzes exhibit a waxy to dull luster, a dull luster on fracture, a refractive index of 1.53 to 1.54, a specific weight in the range of 2.4–2.7 g/cm3, nonsilica impurities of up to 20 percent, water content of up to 4 percent, and a hardness of 6.5 to 7 Mohs. These materials are not minerals in the strictest sense but are textural varieties of quartz, more akin to rocks, and their appearance is governed by the environmental conditions and the nature and amount of impurities present during formation.

The many varieties within these broader classifications can usually be differentiated by observing the colors and patterns and their orientation. Agate is a variety of chalcedony with well-defined bands of at least two colors. There are several subvarieties of agate, one of which is sardonyx. This designation, used by mineralogists, is conferred on a stone that is “distinctly and, usually, straight-banded in white and brown to red layers.” Historians, however, use the term to refer “to cameos (also occasionally to intaglios) when banding is layered or parallel to [the] engraved surface; often artificially dyed.” Both the mineralogical and historical designations apply to this cameo, which was indeed carved from sardonyx. The stone consists of two layers: an ivory-white upper stratum over a seemingly semitranslucent warm-brown stratum. Little of the brown layer is actually visible, and considerable interference from the mount makes it difficult to elucidate its true color and character.

The origin of the stone used for the cameo is unknown. Ancient texts have listed such far-flung locations as Arabia and India as sources, but recent research has demonstrated that this gemstone was available in Thrace, the modern-day Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria.

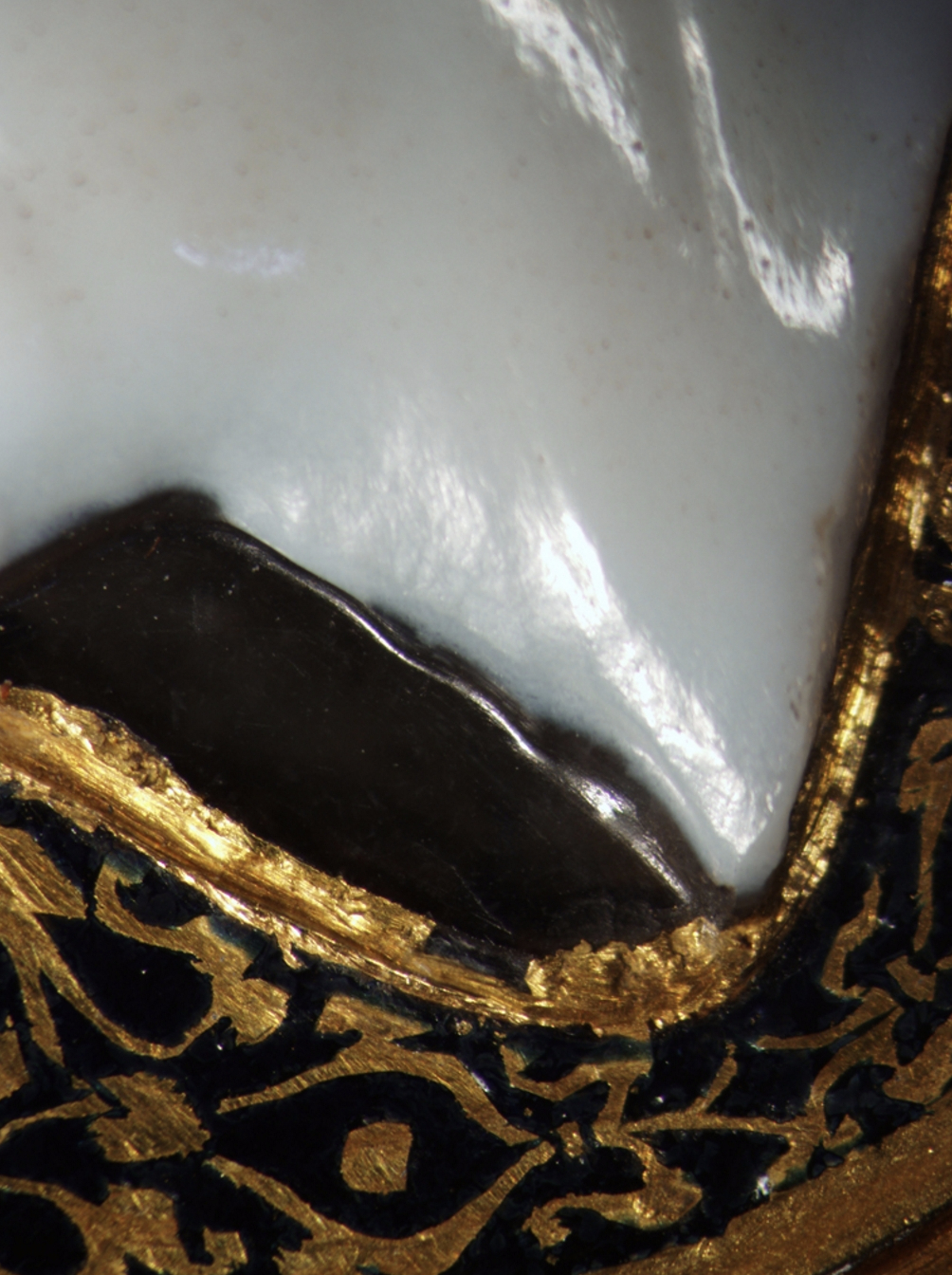

Secondary materials: mount consisting of gold, pearl, and enamels

In the sixteenth century the cameo was fully encased in a gold mount with blue moresque enamel decoration on the front and the enameled Medici broncone (a truncated but still verdant laurel tree) on the reverse, and fashioned into a pendant. This combination of gold and stone is known as a commesso jewel, a typology with French origins. At the time of this modification, the ribbon at the back of the oak wreath, which had broken away, was reinstated with enamel (fig. 137.13).

Fabrication

Method

Little is available in the way of direct textual evidence from the ancient world regarding the technique of gem engraving. Nonetheless, it appears that over the course of history the process has remained much the same, altered only by the introduction of more modern equipment and materials such as power tools and diamond abrasives.

The metal implements used to cut or carve softer stones such as marble (3 Mohs) are not hard enough to cut gemstones. Copper is 3 Mohs and iron is 5. However, the cutting power of these materials can be greatly enhanced by the addition of a hard abrasive, which, when bound to the end of the tool with a lubricant such as olive oil, actually cuts the stone. Quartz sand is both abundant and capable of cutting a soft stone, but it is clear from the ancient sources that emery, a form of corundum (9 Mohs), from the island of Naxos, was the preferred abrasive of engravers in the ancient world.

A horizontal, bow-powered spindle appears to have been the primary tool employed in the cutting of gemstones. The bow could have been operated by the carver himself or by an assistant. The spindle could also have been operated by wheels or foot pedals for greater speed. Such power, however, would have been unnecessary since excess speed can have undesired consequences: the removal of too much abrasive by centrifugal force and the increased likelihood of losing control. Tools with tips shaped in the form of wheels, cones, or globes, like the burs used in modern dentistry, were employed. The carver applied a slurry of lubricant and abrasive onto the tip of the tool and held the gem to the rotating spindle. Often the gem was mounted onto a post or bat to improve control. Toolmarks visible on unfinished gems provide evidence that the carvers used larger tools for the initial stages of carving and smaller, finer tools for more detailed areas. After carving, the gem was polished with files, wooden implements, leather, felt, and other cloths coated with progressively finer slurries.

Unlike intaglios, which were engraved into the stone to create a negative image, cameos were carved in relief, using the colored layers of the stone to create the contrasting visual effects, such as a pale design over a dark background. Multiple colored bands in the stone could be employed to create even more sophisticated compositions of three or more colors. Rather than functional objects, cameos appear to have been used exclusively for decorative purposes.

The tools and techniques of cameo carving were the same as those used for intaglios, but it is significantly more difficult to carve a cameo. This is chiefly because the carving is done against the convex surface of the stone, so that the tool is always applied at a tangent, resulting in little surface contact. Cameo cutting is meticulous work, and the finest examples display a range of sophisticated effects, such as interplay of light and shadow or translucency in a garment. Furthermore, because the stones are not heterogeneous, their natural variations and the presence of inclusions can cause unforeseen challenges. Master carvers knew how to modify their work in response to such surprises.

Ancient recipes for intensifying or altering the colors of the stones have survived. This was done through dyeing and heating processes but also by immersion in honey, which permeates the microstructure of the stone and when heated changes the color of the stone by caramelization or carbonization.

The ancients were aware of the magnification properties of rock crystal, but no evidence supports the creation and use of lenses to aid in gem engraving. Furthermore, much of the engraving was done blind, since the abrasive slurry darkened during carving as remnants of stone and worn tools mixed with it.

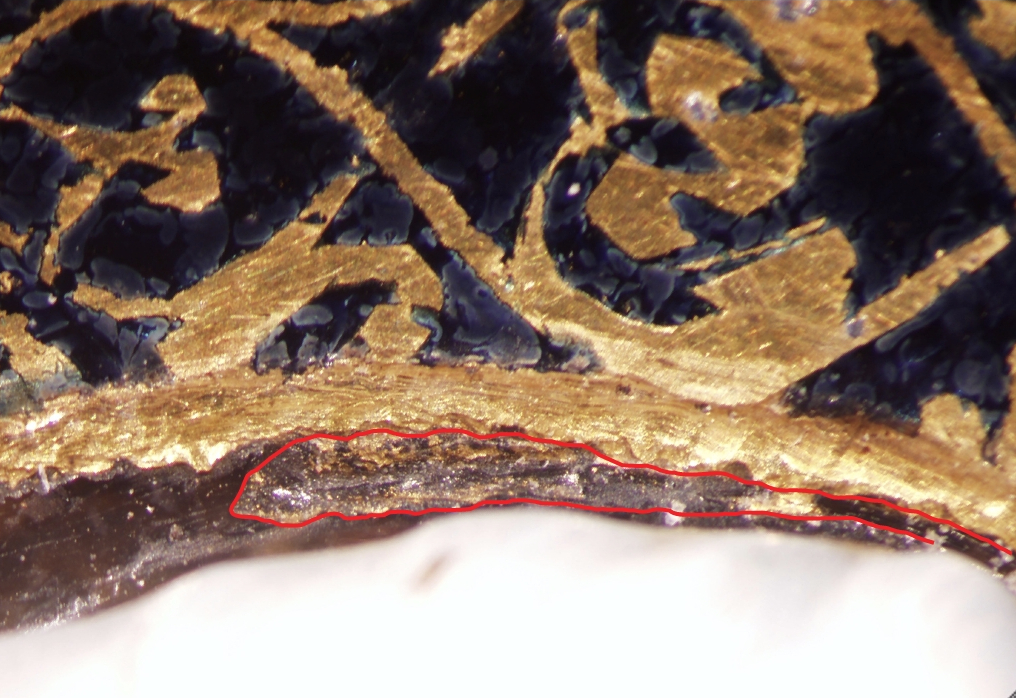

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

The loss of much of the brown layer as well as the obscuring mount makes it difficult to ascertain whether the stone was heat treated before carving. The portrait, facing proper right, was carved from the white stratum of the stone; the brown stratum served as the ground. The white layer does not rest directly against the flat brown background surface of the cameo but is instead raised approximately one millimeter above it (fig. 137.14), apparently to enhance the three-dimensionality and effect of high relief. The carver undercut the majority of this extra material below the white layer using a round tool; a semicircular depression follows the contour of the portrait, and striations from the tool are evident in some places along the depression (fig. 137.15). Interestingly, however, in some areas the carver appears not to have cleared away the excess stone, leaving a small shelf or projecting ledge. This is particularly noticeable in a line extending from under the nostril, along the philtrum, and around the lips to the chin (fig. 137.16). Perhaps the carver chose not to risk undercutting these delicate features lest the profile be damaged. Alternately, it could be that he did not realize that this excess material remained, as a considerable degree of magnification is required to appreciate this feature.

In some places along the neckline there is not a crisp demarcation between light and dark areas, causing the edge of the profile to seem more amorphous (fig. 137.17). Given the evident skill of the carver, these areas should not be construed as missteps but rather as his compensatory reaction to features of the stone exposed in the course of carving.

The handling of the fine detail such as the hair and oak leaves is exquisite in its painstaking exactitude. The individual strands of hair were fashioned with a pointed tool (fig. 137.18 and fig. 137.19), and the oak leaves were rendered with a very small, round implement (fig. 137.20). In the hollow of the nose the carver cut the overlying white stone so thinly as to create the illusion of shadow, heightening the naturalism of the portrait (fig. 137.21).

Under high magnification it is surprising to see the gestural manner with which the carver employed the tools. These expressive shapes and lines, sometimes seemingly unrelated to the final design, coalesce to create a detailed impression when viewed with the naked eye. A sharp downward curve was added to the top of the chin using a pointed tool. The addition of a small sphere carved into the end of the upper lip actually serves to make the lips appear more defined. The line delineating the top of the nostril is very fine and was also made with a pointed tool. This sharp line widens as it continues downward, which was accomplished either with a round tool or with the same pointed tool set on edge, to create the hollows behind the nostrils and to separate the cheek from the tendon at the side of the mouth (fig. 137.22).

Dark inclusions are pervasive across the surface of the stone (fig. 137.23); these can be interpreted as the ingress of carving detritus into the pores of the stone.

At the end of the carving process, the surface was brought to an extremely high polish.

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

The extant portion of the cameo bears no signature or other identifying mark; whether or not a signature was applied to the now-lost portion of the cameo cannot be known.

Weight

63.46 g

Condition Summary

The object is in overall stable condition.

The cameo is a fragment of a once-larger object, and its present contours are roughly rhomboid around the profile of the face and bottom of the neck and circular around the back of the head. It is possible that the lower portion of the fragment is a natural break, but the possibility cannot be discounted that the perimeter was knapped or shaped in some way so as to make the presentation within the enameled mount more pleasing.

There is a hairline crack with secondary staining extending from the bridge of the nose to the nape of the neck (fig. 137.23). A series of small chips are present on the bottom edge of the neck, and a large ovoid spall is visible at the back of the neck below the ribbon (fig. 137.18). Lesser chips and pinhole losses are visible on the tips of the oak leaves at the front of the crown (fig. 137.24). There are conspicuous losses to the helix and lobe of the ear (fig. 137.25). A flat band of abrasion is discernible on the oak wreath, and faint scratches are present overall.

Adhesive or wax residues are visible along the interface between the stone and the mount. Where the ancient cameo meets the Renaissance mount, ovoid lacunae reflective of the inherent [glossary:conchoidal] fracture of the quartz can be seen along the break edges of the stone.

During the sixteenth-century mounting, a deep groove or channel was made around the perimeter, between the stone and the mount, apparently to demarcate the two components. In some places this groove was facilitated by the natural break in the edge of the stone. In other places the stone appears to have been tooled away or cut back. Above the crown of the head, it appears that the lapidarist or jeweler lost control of the tool, resulting in a deep gouge in the stone (fig. 137.26). This channel was then gilded. A good deal of gold encroaches upon the break edges of the stone in places (fig. 137.27), and several of the aforementioned lacunae can be seen beneath the gilding. The cameo fragment was not set level into the mount, causing the proper right side and the section of stone above the crown of the head to protrude slightly. The proper left side is slightly sunken, but the adjacent gilding and enamel ribbon camouflage the discrepancy.

The Art Institute’s accession number is painted in red along the lower proper left edge of the verso of the mount.

Conservation History

While in the museum’s collection, the object has received only one documented treatment: a light surface cleaning using both solvent and mechanical means.

Rachel C. Sabino

Exhibition History

Norfolk (Va.) Museum of Arts and Sciences, The Melvin Gutman Collection of Antique Jewelry, 1964–68, cat. 30.

Martin D’Arcy Gallery of Art, Loyola University of Chicago, The Art of Jewelry 1450–1650: A Special Exhibition of Jewels and Jeweled Objects from Chicago Collections, Spring 1975, cat. 44 (ill.)

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin im Alten Museum, Antikensammlung, Mythos und Macht: Erhabene Bilder in Edelstein, July 26, 2007–May 25, 2008 (cameo returned Feb. 18, 2008), no cat.

Selected References

Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, The Hamilton Palace Collection, sale cat. (Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, June 17–July 20, 1882), p. 231, no. 2164.

Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, The Hamilton Palace Collection: Illustrated Priced Catalogue (Librarie de l’Art / Remington, 1882), p. 237, no. 2164.

William Roberts, Memorials of Christie’s: A Record of Art Sales from 1766 to 1896, vol. 2 (G. Bell, 1897), pp. 44–45.

The Melvin Gutman Collection of Antique Jewelry, exh. cat (Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1966), p. 32, cat. 30 (ill.).

Parke-Bernet, New York, Medieval and Renaissance Jewelry and Vessels of Rock Crystal and Other Semi-precious Stones: The Melvin Gutman Collection Part II, sale cat. (Parke-Bernet, New York, Oct. 17, 1969), lot 53.

Donald F. Rowe, “Pendant of a Roman Emperor,” in The Art of Jewelry 1450–1650: A Special Exhibition of Jewels and Jeweled Objects from Chicago Collections, exh. cat. (Loyola University of Chicago, 1975), p. 61, cat. 44 (ill.), cover (ill.).

Yvonne Hackenbroch, Renaissance Jewellery (Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1979), pp. 70, 73, pl. 8, figs. 165A, B.

Ingrid Weber, “Review of Y. Hackenbroch, Renaissance Jewellery,” Das Munster 33, 4 (1981), p. 374.

John Hayward, “A Renaissance Jewel from the Gutman Collection,” in The Society of Jewellery Historians Newsletter 2, 2 (1982), pp. 13–14.

Ingrid Weber, “Ein Brustbild der Athena in emaillierter Goldfassung zu einem Achatkameo in der Staatlichen Münzsammlung München,” in Münchner Jahrbuch der Bildenden Kunst, 3rd ser., 34 (1983), pp. 101–16, figs. 9, 10.

Martha McCrory, “Cameos and Intaglios,” in “Renaissance Jewelry in the Alsdorf Collection,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 25, 2 (2000), pp. 60–62, cat. 25 (ill.); pp. 95, 105–06; cover (ill.).

Gertrud Platz-Horster, “Zwei römische Kaiserkameen der Sammlung Alsdorf in Chicago,” in Mythos und Macht: Erhabene Bilder in Edelstein, ed. Gertrud Platz-Horster (Antikensammlung Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2008), pp. 22–28; pp. 85–86, figs. 1–3.

Karen Manchester, Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 78, fig. 16.1.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe Photoshop.

Visible Light Microscopy

Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera

Weight

Mettler-Toledo ML3002E digital balance