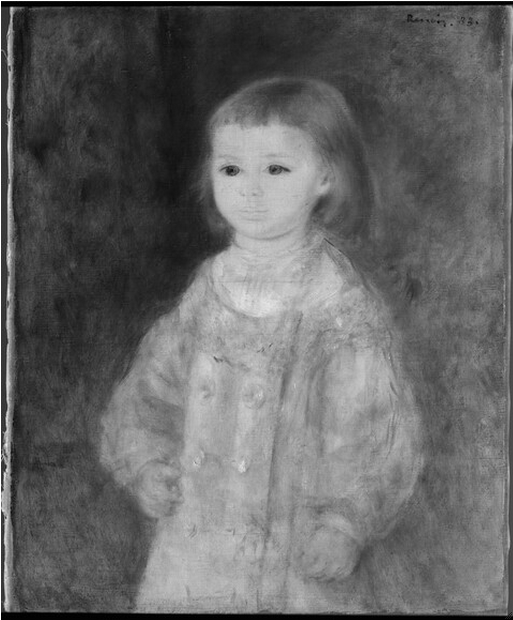

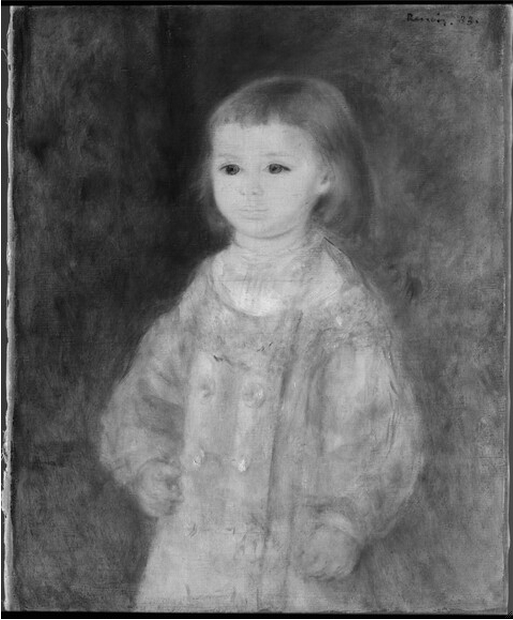

Cat. 16

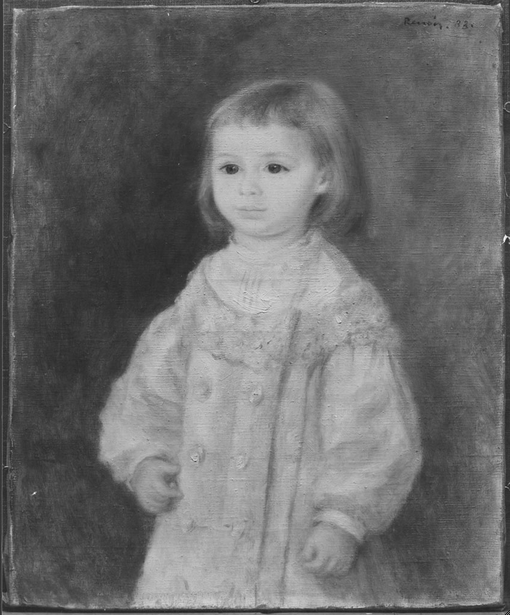

Lucie Berard (Child in White)

1883

Oil on canvas; 61.3 × 49.8 cm (24 3/8 × 19 5/8 in.)

Signed and dated: Renoir. 83. (upper right, in blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1172

1883: A Watershed Year in Renoir’s Career

The first few months of 1883 were a busy time for Renoir. He was working on his portrait of Madame Clapisson (cat. 17), his sole submission to the Salon that year, requiring approval by its patron and shippment to the jury by the second week of March. At the same time, he was preparing for a solo exhibition that was to open April 1 in galleries specially renovated by the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel on the boulevard de la Madeleine, near the busy traffic hub of the place de la Madeleine. Soon after he began Madame Léon Clapisson, Renoir anticipated painting a portrait of two-and-a-half-year-old Lucie Berard. As he wrote to her father, Paul, as early as January or February 1883: “I have begun the second ‘edition’ of Madame Clapisson. . . . This will allow me to get my hand back so that I can start on Lucie as soon as you arrive.” It seems certain the portrait of Lucie would have been included in the retrospective exhibition if it had been ready. Colin Bailey has suggested that its execution followed the exhibition and occurred sometime before Renoir’s trip to Guernsey in September, possibly on a quick visit to Wargemont for Lucie’s third birthday on July 10, on his way to nearby Yport that summer.

In the preface to the catalogue for Renoir’s 1883 retrospective, the art critic Théodore Duret proclaimed the artist to be the figure painter of Impressionism, who portrayed women with delicacy and excelled in portraiture. Two full-length dance paintings included in the exhibition, Dance in the City and Dance in the Country (both 1883; Musée d’Orsay, Paris [Daulte 440 and 441; Dauberville 1000 and 999]) were ambitious demonstrations of this particular gift. Duret might also have added that Renoir was a skilled painter of childhood, a specialization highlighted in the first gallery of the exhibition, which opened the retrospective with an installation of some twenty-one images and portraits of children. As Edmond Jacques of L’intransigeant commented, “Is it possible to push further the expression of childhood grace than in the series of paintings that fill the first gallery to the left of the entrance?” The children featured in this section tended to be very young, such as the subject of the first work in the catalogue, Gypsy Girl (La petite bohémienne) (1879; private collection [Daulte 291; Dauberville 505]), or of the fourth, six-year-old Jeanne Durand-Ruel (1876; Barnes Collection, Philadelphia [Daulte 179; Dauberville 500]). Paul Berard lent generously to the exhibition, contributing, among others, four portraits of his children to the first gallery: no. 11, Sketches of Heads (The Berard Children) (Croquis de têtes) (fig. 2.21 [Daulte 365; Dauberville 282]); no. 19, a portrait of Margot (fig. 2.59 [Daulte 286; Dauberville 503]); no. 17, the unidentified Tête d’enfants, possibly a pastel; and no. 20, another unidentified work, simply titled Portrait.

The year 1883 proved to be a decisive one for Renoir and indeed for the commercial success of the Impressionist movement as a whole. In addition to his retrospective of seventy works—one of a series of exhibitions that included Eugène Boudin, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley—he was represented in Impressionist exhibitions organized by Durand-Ruel in London, Boston, and Berlin. These exhibitions provided unprecedented exposure for the Impressionists and required considerable capital investment, but resistance to their style persisted, and the press reviews remained predominantly negative and uncomprehending. Despite Durand-Ruel’s promotion of his work, Renoir began to experience self-doubt after he moved into a larger studio yet failed to gain a wider clientele for portraits. Paul Berard and his wife adored their portrait of Lucie but had difficulty convincing others of its merits. In December 1883 Berard confided his concerns to a mutual friend, the collector Charles Deudon: “As far as Renoir, he is having a crisis of confidence. His vast studio horrifies him and he can do nothing about it; except for the portrait of Mme Clapisson, I have seen nothing new and he has no new commissions. . . . I am overwhelmed by the difficulty one encounters trying to have his painting accepted. . . . Unfortunately for Renoir, we cannot get others to derive the pleasure that we do from his work, and this portrait [Lucie Berard (Child in White)], so different from the type that [Jean-Jacques] Henner paints, simply frightens people away.”

Lucie Berard: A Favorite Model of Renoir’s

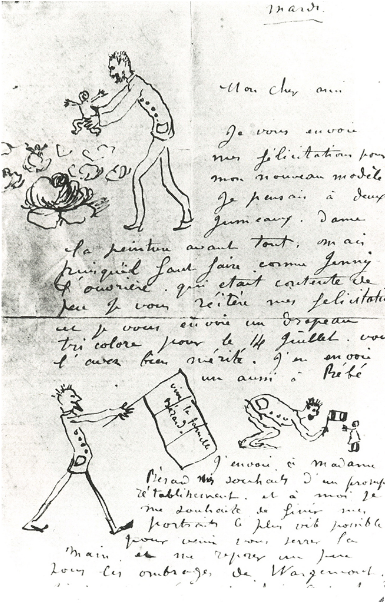

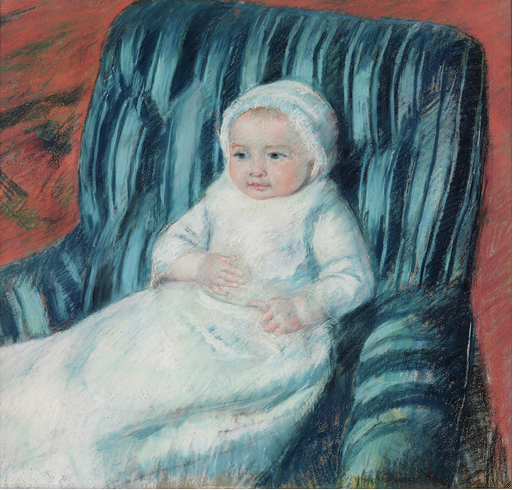

Renoir and Paul Berard had been close friends since 1878, when they probably met at the salon of Marguerite Charpentier. The artist soon took on the role of family portraitist, as he had for the Charpentiers prior to that. As a member of a Protestant banking family and a former diplomat, Berard had deep pockets and a more open mind than many of his station. By the time of his death on March 31, 1905, he had amassed a large collection that included works by Renoir as well as Monet, Sisley, Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and other participants in the Impressionist exhibitions. Beginning in the summer of 1879, Renoir made frequent visits to the Berard estate in Normandy, near the village of Wargemont, where Lucie and her sister Margot were born. In addition to portraits of the Berard family, Renoir painted landscapes and genre paintings and decorated the dining room and salon of the chateau with still lifes. Of the four Berard children, Lucie would become the most beloved of Renoir. After her birth on July 10, 1880, he portrayed the newborn in a sketch accompanying a letter congratulating Berard for giving him a “nouveau modèle” (fig. 10.67). Mary Cassatt also knew the family and made her own pastel likeness of baby Lucie propped uncomfortably in an armchair, dressed in a long presentation gown (fig. 10.65). Family legend has it that Renoir frightened the Berard girls with his teasing and once amused himself by letting the canaries out of their cage, much to girls’ dismay.

The little girl in the Chicago portrait, Lucie Louise Berard, who evoked for Douglas Druick the “personification of attentive innocence,” would grow up during a tumultuous period in European history, living through both world wars and the rise and fall of Charles de Gaulle, and dying in 1977 at the age of ninety-six. In a photograph taken about 1888 (fig. 10.64), she still has the large eyes and unsmiling expression captured in her portrait, but she is now a determined and strong-willed young girl. In April 1905, when she was twenty-four, Lucie wed Jules Edmond David Pieyre Lacombe de Mandiargues, a civil engineer who died at the front in August 1916. She never remarried. One of her two sons, André, became a prominent novelist and poet. Lucie’s husband bought Renoir’s 1883 portrait of her at the sale of the collection of Paul Berard in May 1905—a perfect wedding present and a memento of her father—but the couple did not own it long. During the financially difficult period leading up to World War I, the painting was sold, and by February 1913 it was in the collection of Martin A. Ryerson (see Provenance).

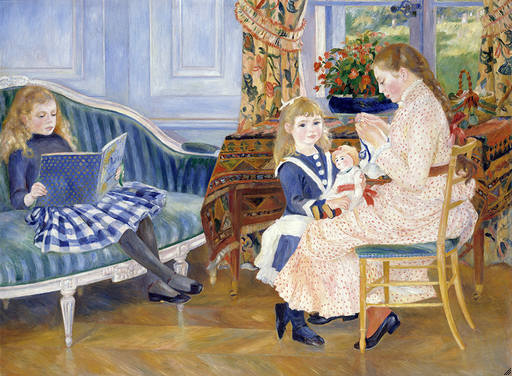

A small bust portrait of Lucie wearing a white pinafore, painted in early 1884 (fig. 10.63 [Daulte 456; Dauberville 1231]), marked a significant turning point in Renoir’s career following his crise de découragement in 1883. With its emphasis on line, smooth modeling, and controlled brushwork, this portrait is a dramatic departure from the one executed just a year earlier. Writing to inform Berard that it was finished in his “new manner” and would be the “last word in art,” Renoir provided important insight into the resolution of his crisis: “One always thinks one has invented the locomotive until the day when one realizes that it doesn’t work. . . . I’m beginning a little late to know how to wait, having had enough failures like this.” This second portrait of Lucie would prove preliminary to Renoir’s valedictory portrait of the Berard sisters, one of the masterpieces of his so-called Ingresque style, Children’s Afternoon at Wargemont (fig. 10.62 [Daulte 457; Dauberville 965]). In his final portrayal of Lucie, Renoir shows her standing with a doll looking warily out at the viewer, a child whose innocence derives from her inability to read or embroider, activities with which her sisters are engaged. She can only draw upon imagination to amuse herself. While family friend Jacques-Émile Blanche described the Berard sisters as “unruly savages who refused to write or spell,” here the girls appear quietly absorbed in their activities. Thus Renoir ended his series of portraits of the family with a painting that commemorates the graciousness of childhood.

Renoir and the Old Masters

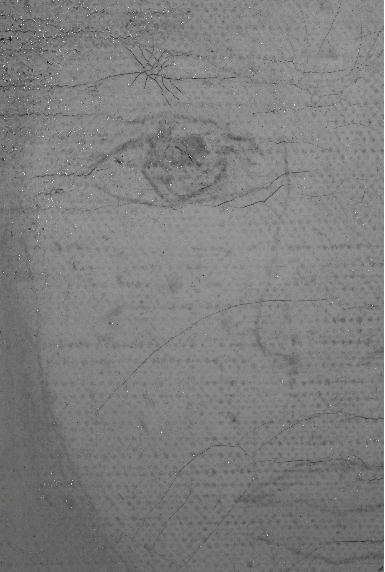

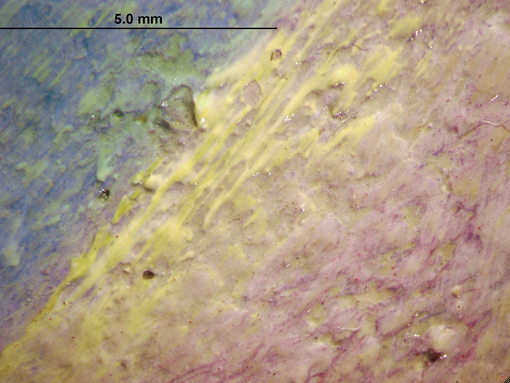

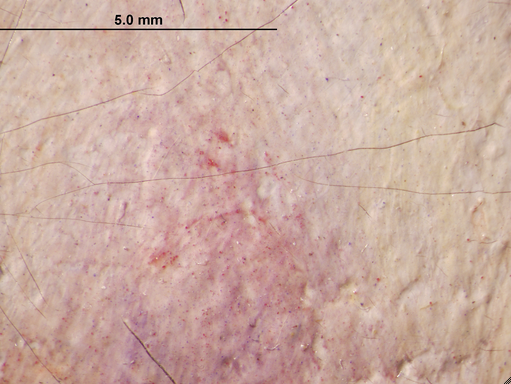

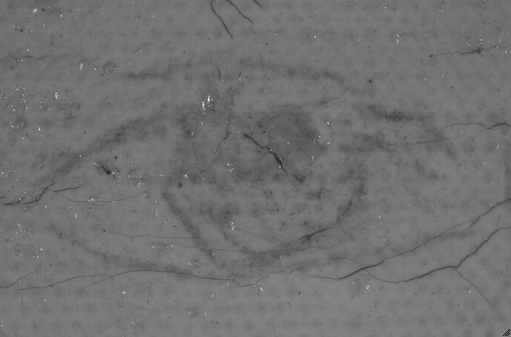

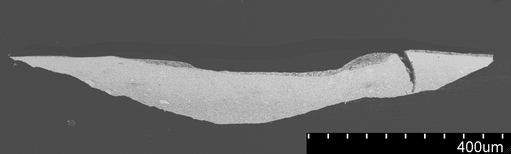

While the audacious Impressionist execution of Lucie’s portrait may have frightened members of the Berards’ social circle, it was not a completely radical break with tradition. In fact the portrait reflects Renoir’s close attention to the art of the past. In choosing to show Lucie alone in a half-length format, turned slightly to her right, without any of the usual accessories of childhood, Renoir was inspired by an old master painting: Infanta Margarita (fig. 10.68), from the workshop of seventeenth-century Spanish painter Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez. In the nineteenth century, this small portrait was considered a highlight of the collection of the Musée du Louvre. It shows Velázquez at the height of his power for rendering the soft glow of natural light. For Renoir this painting represented all the ideals he wished to capture in his own painting. Describing it in the early twentieth century to the art dealer Ambroise Vollard, he declared: “What I love so much is that aristocratic quality that you find over and over again in Velázquez, in the smallest detail, the simplest ribbon. . . . The whole of painting is in the little pink bow of Infanta Margarita in the Louvre! How lovely the eyes are and the flesh tones near the eyes! There is not the slightest shadow of sentimentality, of mawkishness!” As Lucie shares with the Infanta a pose of graceful serenity, it is clear that childhood innocence without sentimentality was Renoir’s goal as well in the Chicago portrait. Renoir also took on the challenge of the Spanish master’s innovative flesh tones with a colorist’s bravado. Care was taken with finer brushes in the modeling of Lucie’s face in soft pinks and whites; an iridescent, pale yellow is used for shading below her chin and over her neck, possibly in emulation of the glowing flesh tones of the Infanta (see fig. 10.61). Two underdrawing campaigns, the first in black chalk or charcoal and the second in blue paint, hint at changes Renoir might have made to echo Infanta Margarita. The black underdrawing appears to show Lucie’s left forearm raised as if she were holding a doll or toy, but in the blue-painted underdrawing, her arm was moved to hang by her side, closer to the formal pose of the Infanta (fig. 10.66; see Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch in the technical report).

Renoir’s earlier portrayal of Lucie, in the painting Sketches of Heads (The Berard Children) (fig. 2.21), dated 1881, also references the art of the past. The painting is an exceptional example of collage portraiture, a format that Renoir adopted from the study drawings of eighteenth-century French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau. Here Lucie is portrayed as a sleeping baby (upper left), and awake and looking to her right (just to the right of center). In addition to Lucie, the work also depicts her older brother André (born 1868; lower left); Marthe (born 1870; center, holding a book, and bottom right); and Margot (born 1874; just to the left of center, reading, and upper right).

Renoir’s Choice of Materials

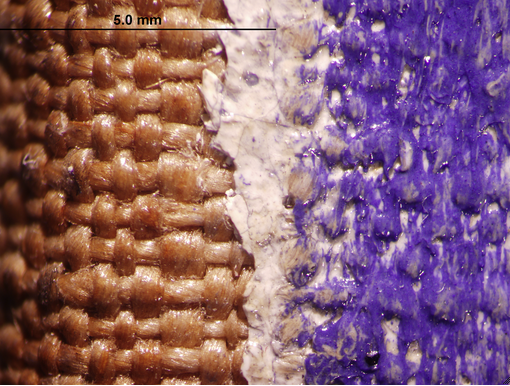

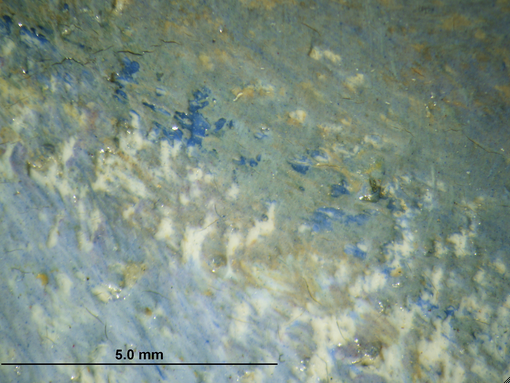

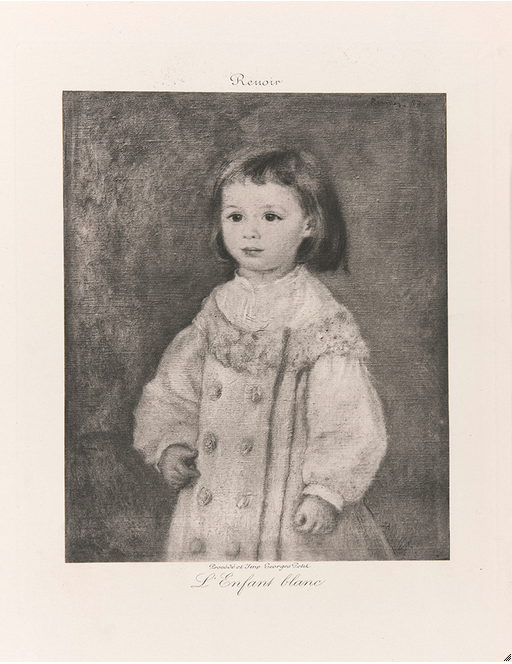

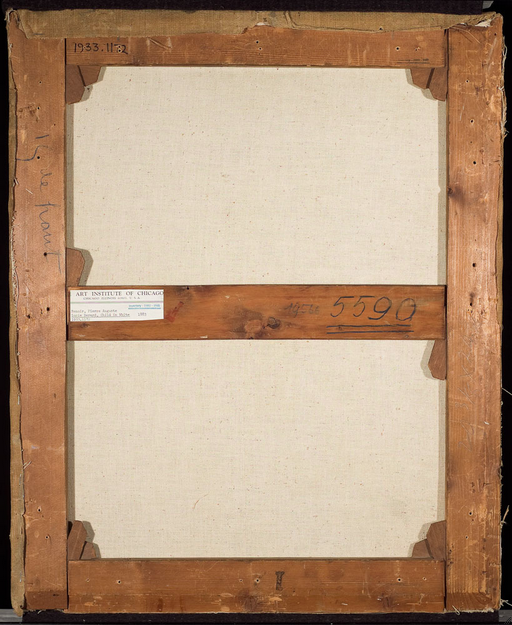

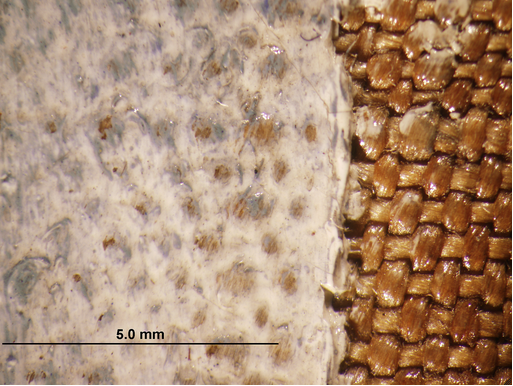

Compared to the portrait of Madame Clapisson, Renoir’s 1883 Salon submission, there is an informality about the preparation of Lucie Berard (Child in White) that suggests the circumstances of the commission were quite different. This may have something to do with his payment (the amount he received for the painting of Lucie is not known, though he probably asked much less for a child’s portrait than for an adult’s), but it more likely reflects the Berards’ familiarity with the artist and their level of comfort with the Impressionist technique of broken brushwork and color harmonizations. One remarkable aspect of the work is how the texture of the canvas weave is clearly visible to the naked eye (fig. 16.69). The weave can be seen in the reproduction of the portrait in the 1905 sale catalogue (fig. 16.70), so it was likely apparent early in the history of the painting. The weave of this canvas is much looser and coarser than that of the canvas of Madame Léon Clapisson, which reveals how easily Renoir could adapt his technique to different canvas types. The canvas edges visible on the back of the stretcher of Lucie’s portrait appear unevenly cut (fig. 16.71), which would be unusual in a canvas prepared by a professional art supplier. The ground layer is pure lead white, does not contain the common additives and extenders found in commercially applied preparations, and was applied only to the compositional area (fig. 16.72; see Preparatory Layers in the technical report). These factors suggest that the artist may have prepared the canvas himself.

Renoir’s use of color in the painting reflects an innovative harmonization. The background progresses from lighter yellows and greens on the right to a deep blue on the left. These background colors resonate with those the artist chose for modeling the figure of Lucie. Could he have intended to suggest an outdoor setting? Following the rejection of his first version of the portrait of Madame Clapisson, he vowed never again to paint portraits en plein air; yet he could only have achieved the intense coloration of Lucie’s portrait by placing her under natural light. For the Berards, the portrait of Lucie was eminently satisfying. After hanging it in the best spot in his study in a beautiful new frame he had specially made for it, Berard wrote to Deudon that he and his wife, Marguerite, “swoon with pleasure in front of it.”

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

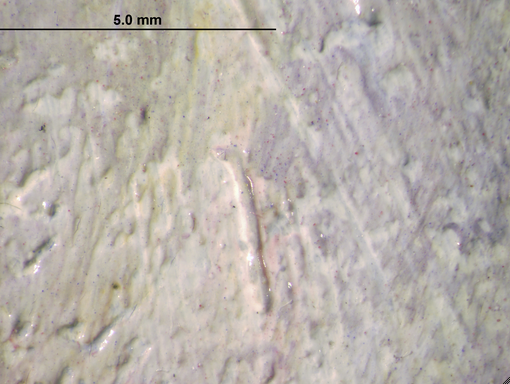

Renoir began this portrait with a standard-size [glossary:canvas] that he may have prepared himself. The raw, stretched canvas has a heavy [glossary:ground] layer, initially applied with a [glossary:palette knife] and then worked into the canvas to the edges of the compositional area with a brush. The thickness of the ground varies throughout and does not hide the canvas texture or its many imperfections, nubs, and varying thread thicknesses. Once the canvas was prepared, the artist made a contour sketch using fine lines in a soft, dry medium, such as natural charcoal or black chalk, to indicate the basic shapes and establish the figure. An additional set of [glossary:underdrawing] lines in fluid blue paint reinforces some of the contours of the head, while changing the arms and the outline of the costume. Renoir moved back and forth between the drawing and painting stages, partially fleshing out at least one earlier position for the arms before returning to establish a new set of contours in blue paint. Parallel to the figure’s right arm, evidence of its previous position—more bent and farther from the body—is visible under normal viewing conditions. This arm was then placed closer to the body, and perhaps pushed backward in space or given a less voluminous sleeve. The figure’s left arm was initially articulated in charcoal farther from the body and bent at the elbow, while a second underdrawing in blue paint places it closer to the body or more forward in space; the artist here settled for a final position between these two earlier placements.

Renoir also made small changes to other areas of the composition, perhaps altering the figure’s hairstyle and raising her eyes from their initial placement in the charcoal drawing. The volume and possibly the shape of the garment near the bottom of the composition were also altered. After establishing the figure, the artist brought in pale background colors immediately around it, perhaps to cover previous compositional choices and underdrawing. These pale colors were then overlaid with heavier paint in tinted blues, making the background appear denser toward the center of the picture.

The paint is generally full-bodied and paste-like, retaining the mark of the brush and an overall sense of stiff, individual strokes that were applied wet-in-wet and minimally mixed on the canvas, contrasted locally with the smooth, well-blended paint used in the flesh and hair. White impasto highlights for the decorative collar and buttons on the child’s costume appear as final touches to the work.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 2.19).

Signature

Signed and dated: Renoir. 83. (upper right, in blue paint) (fig. 1.2, fig. 2.50).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions of the canvas, measuring the primed compositional area, were approximately 60.5 × 49 cm. This corresponds to a no. 12 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size (60 × 50 cm) canvas; this number is also stenciled on the verso of the [glossary:stretcher] (fig. 2.35).

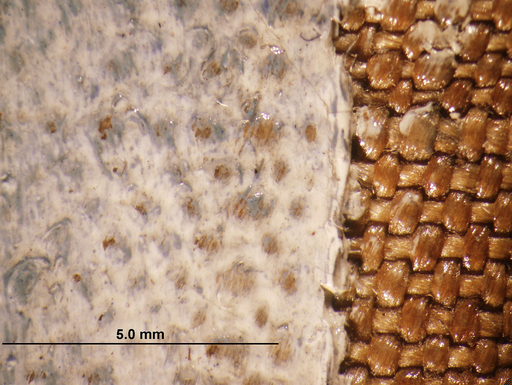

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 19.8V (0.5) × 15.3H (0.7) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

The canvas texture is characterized by threads of uneven thickness and numerous nubs and imperfections. Strong [glossary:cusping] around the edges corresponds to the placement of the original tacks. Along with the presence of priming only in the compositional area, the strength of this cusping suggests that the canvas was stretched before it was primed. The [glossary:tacking margins] do not appear to have been trimmed flush with the back edge of the stretcher and bend around to the verso, especially at the top.

Stretching

Current stretching: The painting was lined and restretched at an unknown date prior to 1968. The dimensions appear to have been increased on all sides and the stretcher tapped out accordingly. The painting was mounted slightly askew, so that paint along the top edge on the right is bent at the foldover. An undated photograph, presumably taken before this lining was applied, shows the painting correctly mounted on its stretcher with no unprimed margin of canvas visible around the edges of the compositional area (see Conservation History) (fig. 2.58).

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed approximately 5.5–7.0 cm apart.

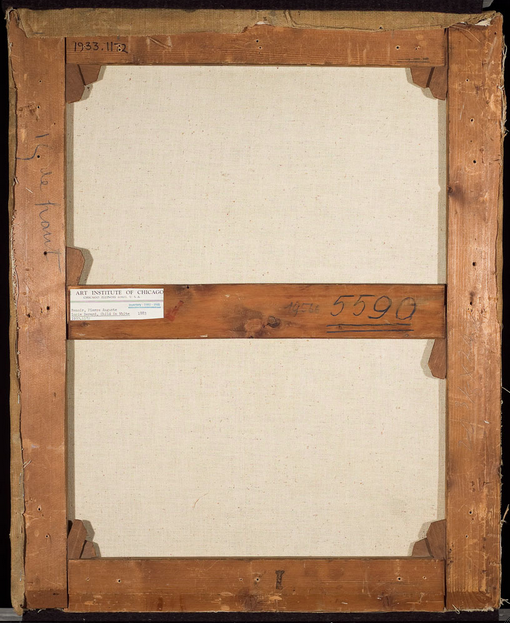

Stretcher/strainer

Though the painting was lined and restretched as part of a previous, undocumented conservation treatment, it appears to have retained its original stretcher (see Conservation History). The canvas is tacked to a five-member, blind mortise-and-tenon stretcher with a horizontal [glossary:crossbar] (fig. 1.1). Depth: 2.2 cm.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: black stamp/stencil

Content: 12 (fig. 2.35)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

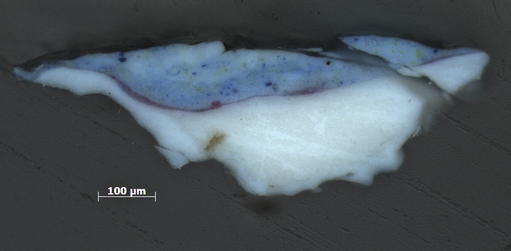

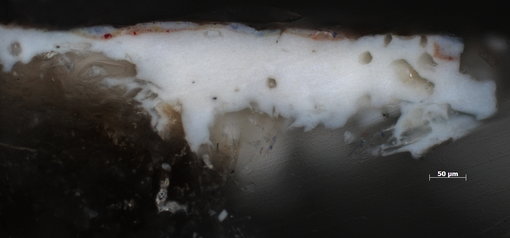

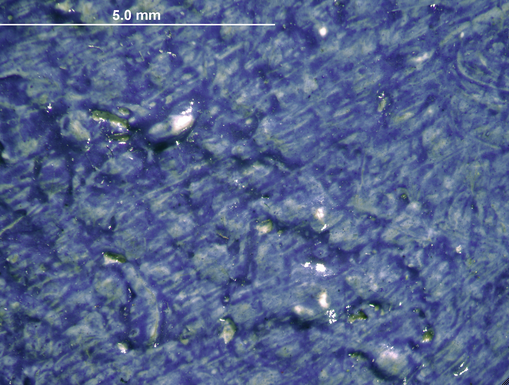

Ground application/texture

Renoir applied the ground to the compositional area after the canvas was stretched. The ground is thicker in the center, tapering out toward the perimeter, and may have been applied in successive layers (fig. 16.73). Cross-sectional analysis suggests the ground is generally approximately 10–160 µm thick, and as much as 300 µm thick in some areas. Sharp marks in the [glossary:X-ray] suggest that the thicker areas of the ground were worked into the canvas with a palette knife, but the softness of the perimeter suggests brush application. It is likely that the bulk of the preparation was applied with a palette knife, and then a brush was used to smooth the ground out to the edges and around the various canvas imperfections. Despite the apparent thickness of the ground in some areas, the preparation layer often leaves the canvas texture visible (fig. 2.47).

Color

The ground is white; no colored particles were observed under [glossary:stereomicroscopic examination] or [glossary:cross-sectional analysis].

Materials/composition

The ground is lead white with traces of alumina, calcium-based white, and complex silicates (fig. 1.3). The [glossary:binder] is estimated to be [glossary:oil].

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

The artist seems to have outlined the major features of the figure, including the most prominent elements of the face and parts of the costume, directly on top of the ground before painting.

Medium/technique

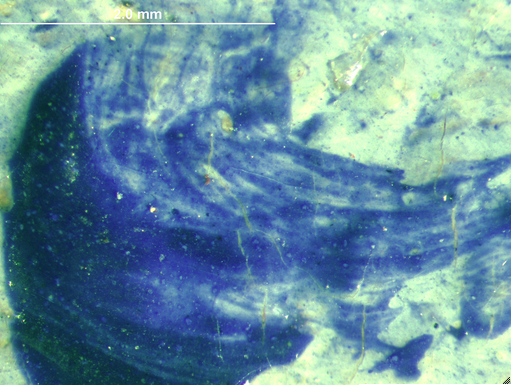

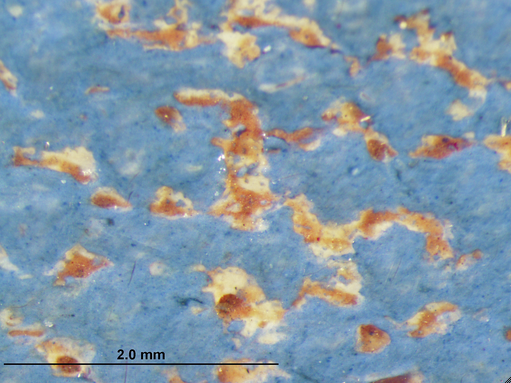

Infrared examination shows that Renoir loosely established the major contours of the figure and costume with long, sweeping, somewhat sketchy lines. Faint lines intermittently outlining the basic shapes are extremely fine and appear wider in some areas where they were reinforced by the artist. This initial set of underdrawing lines appears to have been done in a soft, dry medium, possibly charcoal or chalk (fig. 1.4). This medium contains large black pigment particles that were brought into subsequent paint layers and can be seen microscopically in the whites of the figure’s eyes under normal viewing conditions (fig. 2.48). In some places, the drawing material appears to catch only the thread tops, but in most areas, the softness of the medium allowed it to reach both the high and the low points in the canvas weave.

Elsewhere, and likely after the initial sketch, Renoir outlined some of the features in dark-blue paint, including the contours of the costume. It is unclear, however, whether these outlines were a separate compositional planning stage or the beginning of the painting stage, and therefore less visible in some areas because they were brought into the upper paint layers. At the figure’s left shoulder, a blue outline remains visible through the translucent upper paint layers and can be seen under normal viewing conditions (fig. 2.52).

Revisions

Renoir seems to have altered the pose of the figure at least twice before settling on the visible arrangement of the arms. After making a very general sketch that established the placement of the figure, the artist continued with thin charcoal or black-chalk lines to define the head and hair, the facial features, and the general outline of the body. The second set of apparent underdrawing lines, in blue paint, seems to indicate a different position of the child’s arms and sleeves. There are also summary lines, both painted and drawn, indicating changes in the volume and shape of the bottom of the child’s garment, though their exact compositional impact is not entirely clear.

After establishing the composition with black lines, Renoir painted the eyes slightly higher than in the drawing, farther away from the nose and mouth (fig. 2.8). Additionally, the positions of both arms appear to have been altered between the drawing and painting stages. Black charcoal or chalk lines indicating the figure’s left arm suggest that it was originally bent, with the hand even higher than the right one. The artist abandoned this choice between the first and second drawing campaigns, as the subsequent sketch in blue paint shows the child’s left arm extended, as in the final composition.

Renoir used blue paint to outline some of the features of the clothing and to alter the positions of the sleeves while leaving the head unchanged. Blue painted lines indicating the figure’s left arm show it both in its current position and farther toward the center of the picture. The figure’s right arm appears to have been articulated at least twice before the artist established its current placement. In one version, the right shoulder appears raised, with the elbow bent so that the arm is farther away from the body and the hand slightly higher than in the final composition. In another version, the shoulder is in the same position as in the final composition, while the sleeve curves and tapers toward the body below the elbow, somewhat mirroring the final orientation of the left arm; compared to this sketch, the final version of the right arm appears to have been pushed backward in space, with less volume in the sleeve (fig. 2.9).

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

Renoir seems to have moved back and forth between compositional planning and painting throughout the execution of this work, since many of the changes associated with painted lines visible in infrared images and under microscopic examination reveal at least limited heavier brushstrokes in raking and specular light. Additionally, the final placement of the arms has a corresponding underdrawing in thin blue paint. The X-ray, though visually complicated by the vigorous application of the ground, indicates that the artist may initially have parted the child’s hair in the center and swept it off to either side in the front. As a result, the front sections of the hair may have rested farther down on the forehead. The initial set of black underdrawing lines indicates that the eyes were once lower as well. Aside from the possible change in hairstyle and the position of the eyes for the finished composition, there appear to have been no other changes to the head and face.

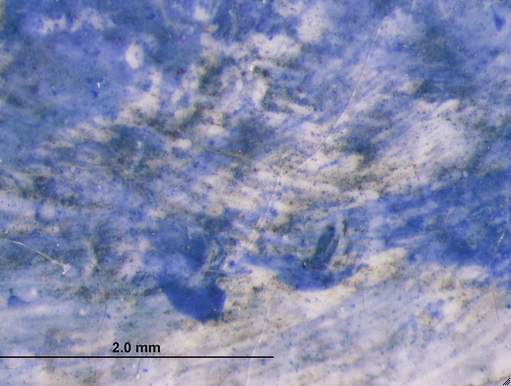

While Renoir began by sketching in black charcoal or chalk, it appears he reinforced and revised the composition with thin lines in blue paint, some of which appear to have been partially fleshed out in heavier paint before further alteration. Echoes of the earlier placement of the figure’s right shoulder can still be seen running parallel to its final location, despite the addition of background paint in this area. After establishing the figure, the artist probably began the background in thinner, almost wash-like layers of blue, pink, and possibly yellow in a kind of aureole immediately surrounding the figure, before adding heavier layers of darker, tinted blues (fig. 2.20). This initial application of the background may have served to cover varying earlier compositional choices, and as a result, the background appears denser toward the center of the picture (fig. 2.22).

In many areas, the paint is of a paste-like consistency that retains brush marks and accentuates the underlying textures of canvas and previous brushstrokes (fig. 2.53). Various colors appear for the most part to have been blended on the canvas rather than on the artist’s palette (fig. 2.54). Renoir complemented the individual strokes seen throughout much of the costume and background with the smoothly blended painting of the flesh tones and the hair (fig. 2.55). Final touches of thick white [glossary:impasto] indicate the decorative collar and buttons on the figure’s garment and the highlights in her eyes (fig. 2.23).

Painting tools

Small to medium brushes, round and flat, with strokes up to about 1 cm wide; palette knife for ground application.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, vermilion, two red lakes, cobalt blue, ultramarine blue, bone black, zinc yellow,, and iron oxide yellow and/or red and possibly burnt sienna.

The observation of a characteristic salmon-colored [glossary:fluorescence] under [glossary:UV] light suggests the presence of a fluorescing red lake in the hair, flesh tones, and parts of the figure’s dress (fig. 2.10).

Polarized light microscopy ([glossary:PLM]) indicates that the background blue is composed of predominantly cobalt blue with some ultramarine blue (fig. 2.56).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The work was cleaned of a previous [glossary:natural-resin varnish] and coated with its current [glossary:synthetic varnish] during the 1972 treatment (see Conservation History). It is unknown whether the removed natural-resin varnish was original to the painting.

Conservation History

The painting’s first documented treatment occurred in 1968, when it was recorded as having an [glossary:aqueous lining] with a [glossary:hardboard] interleaf and a secondary canvas backing. At this time the painting also had widespread cracking and abrasion; abraded areas were overpainted, and the entire painting was coated in a heavy, discolored natural-resin varnish (fig. 2.57). During this treatment, grime was removed and the surface coating was thinned. The work was inpainted with methacrylate paints and given a synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, inpainting, and a final coat of L-46). In 1972 the painting was treated again, and all [glossary:varnish] coatings were removed. The work was inpainted and varnished using the same materials as in the 1968 treatment.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition, with a secure aqueous lining and hardboard interleaf; deformation of the board over time has caused the painting to have a slight overall concave warp. The lining process accentuated nubs, uneven thread thicknesses, and other canvas imperfections, in addition to increasing the weave impression, especially in the horizontal direction. There also appear to be localized lumps of lining adhesive throughout. The pressure of the lining process caused stress microcracking along the threads, visible under microscopic examination. There are stretcher-bar creases across the center with associated cracking, and there is localized cracking in the figure’s face and costume. The painting has a glossy synthetic varnish that was applied during the 1972 treatment, with residues of a very discolored natural-resin or oil-resin varnish in the depressions of the canvas weave. The effect of this discoloration is especially noticeable in the background, where large areas appear to have a yellow cast. This darkening, combined with underpainting in the background immediately surrounding the figure, gives a false sense of space because the side margins appear more lightly painted than the center. The [glossary:inpainting] is limited to localized losses and abrasions.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame may be original to the painting. It is a French (Paris), late-nineteenth-century, Louis XIV reproduction, gilt ogee frame with cast foliate ornament, center and corner fleur-de-lis cartouches linked by foliate scrolls and strapwork, and pendent bellflowers on a diamond bed. The frame has oil and water gilding over red bole on cast plaster and gesso. The ornament and sight molding are selectively burnished, and the gilding has been heavily rubbed, exposing the bole. The gilding is toned with a casein or gouache raw umber [glossary:wash] with a gray overwash. The pine molding is mitered and nailed. At some point in the frame’s history, the original verso was planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance, a back frame was added, and all back and interior surfaces were painted. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is torus with leaf-tip outer molding; scotia side; ogee face with cast center and corner fleur-de-lis cartouches on a diamond bed, linked by foliate scrolls and strapwork on a quadrillage bed, and pendent bellflowers on a diamond bed; sanded front frieze bordered with fillets; and ogee sight molding with strapped, linked foliate scrolls and bellflowers on a recut bed (fig. 2.11, fig. 2.6).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Commissioned from the artist by the sitter’s father, Paul Berard (1833–1905), Wargemont and Paris.

Sold at the Paul Berard sale, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 8, 1905, lot 20, to the sitter’s husband, J. E. D. Pieyre Lacombe de Mandiargues (1879–1916), for 10,030 francs.

Acquired by André Schoeller, Paris, by May 25, 1912.

Sold by André Schoeller, Paris, to Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, May 25, 1912, for 11,000 francs.

Sold by Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, Feb. 26, 1913, for 23,500 francs.

Bequeathed by Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Exhibition History

Possibly Paris, Durand-Ruel, Exposition des oeuvres de P.-A. Renoir, Apr. 1–25, 1883, cat. 20, as Portrait. Appartenant à M. Berard.

Paris, Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, Salon d’automne, Oct. 18–Nov. 25, 1905, cat. 1322, as Portrait d’enfant en robe blanche.

Paris, Bernheim-Jeune, Exposition Renoir, Mar. 10–29, 1913, cat. 25, as L’enfant en robe blanche. App. à M. R.

Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, Paintings: Édouard Manet, Pierre Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Oct. 15–Dec. 1, 1924, cat. 20.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, May 23–Nov. 1, 1933, cat. 339. (fig. 2.7)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Manet and Renoir, Nov. 29, 1933–Jan. 1, 1934, no cat. no.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture for 1934, June 1–Oct. 31, 1934, cat. 227.

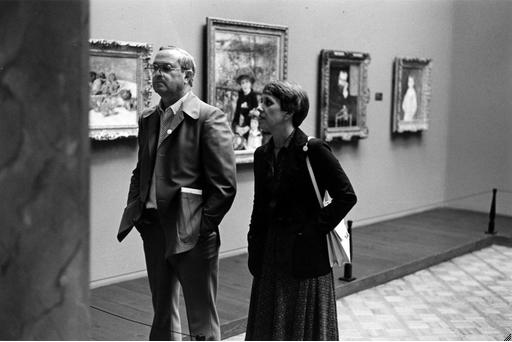

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 46 (ill.).

Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Modern Masters, Manet to Matisse, Apr. 10–May 11, 1975, cat. 96 (ill.); Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, May 28–June 22, 1975; New York, Museum of Modern Art, Aug. 4–Sept. 28, 1975.

Tokyo, Seibu Museum of Art, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], Oct. 18–Dec. 17, 1985, cat. 37 (ill.); Fukuoka Art Museum, Jan. 5–Feb. 2, 1986; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Mar. 4–Apr. 13, 1986.

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, June 27–Sept. 14, 1997, cat. 47 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 17, 1997–Jan. 4, 1998; Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, Feb. 8–Apr. 26, 1998. (fig. 2.18)

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Aug. 21, 2001–Jan. 23, 2002.

Columbia (S.C.) Museum of Art, Renoir!, Apr. 25–Oct. 1, 2007, no cat.

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 30 (ill.).

Selected References

Possibly Durand-Ruel, Paris, Catalogue de l’exposition des oeuvres de P.-A. Renoir, exh. cat. (Pillet et Dumoulin, 1883), p. 11, cat. 20.

Société du Salon d’Automne, Catalogue de peinture, dessin, sculpture, gravure, architecture et art décoratif, exh. cat. (Cie Français des Papiers-Monnaie, 1905), p. 146, cat. 1322.

Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, Exposition Renoir, exh. cat. (Bernheim-Jeune, 1913), cat. 25.

Bernheim-Jeune, Renoir, with a preface by Octave Mirbeau (Bernheim-Jeune, 1913), opp. p. 22 (ill.), p. 58.

Art Institute of Chicago, General Catalogue of Paintings, Sculpture, and Other Objects in the Museum (Art Institute of Chicago, 1914), p. 211, cat. 2144.

Guillaume Janneau, “Impressions d’Amérique,” Le bulletin de la vie artistique 2, 8 (Apr. 15, 1921), p. 237 (ill.).

Carnegie Institute, Exhibition of Paintings: Edouard Manet, Pierre Renoir, Berthe Morisot, exh. cat. (Carnegie Institute, [1924]), no. 20.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 162, cat. 2153.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute (Continued),” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 4 (Apr. 1925), pp. 48, 49 (ill.).

Ambroise Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record, trans. Harold L. Van Doren and Randolph T. Weaver (Knopf, 1925), p. 241.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für Freunde und Sammler der Kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 78. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture; Lent from American Collections, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1933), p. 48, cat. 339.

Pennsylvania Museum of Art, “Manet and Renoir,” Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin 29, 158 (Dec. 1933), p. 19.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), p. 38, cat. 227.

Albert C. Barnes and Violette de Mazia, The Art of Renoir (Minton, Balch, 1935), pp. 77; 78; 271, no. 134 (ill.); 455, no. 134.

Maurice Bérard, Une famille du Dauphiné: Les Bérard, notice historique et généalogique (Laroze, 1937), fig. 35.

Maurice Bérard, Renoir à Wargemont, Maîtres du XIXe siècle (Larose, [1938]), (ill.).

Reginald Howard Wilenski, Modern French Painters (Reynal & Hitchcook, [1940]), p. 338.

Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpieces in the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1952), (ill.).

Dorothy Bridaham, Renoir in the Art Institute of Chicago (Conzett & Huber, 1954), pl. 7.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 397.

John Maxon, The Art Institute of Chicago (Abrams, 1970), pp. 267 (ill.), 285.

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1, Figures, 1860–1890 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), pp. 306–07, cat. 449 (ill.).

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), pp. 113, cat. 564; 114, cat. 564 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 120–21, cat. 46 (ill.); 210; 211.

François Daulte, “Renoir et la famille Berard,” L’oeil 223 (Feb. 1974), p. 5, fig. 7.

William S. Lieberman, ed., Modern Masterpieces: Manet to Matisse, exh. cat. (Museum of Modern Art, 1975), pp. 206–07 (ill.); 267, cat. 96.

Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (Abrams, 1984), pp. 129, 132 (ill.), 150.

Art Institute of Chicago, Seibu Museum of Art, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, and Fukuoka Art Museum, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], trans. Akihiko Inoue, Hideo Namba, Heisaku Harada, and Yoko Maeda, exh. cat. (Nippon Television Network, 1985), pp. 83, cat. 37 (ill.); 148, cat 37 (ill.).

Anne Distel, “Charles Deudon (1832–1914) collectionneur,” Revue de l’art 86 (1989), p. 62, n. 3.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 91 (ill.).

Götz Adriani, Renoir, exh. cat. (Kunsthalle Tübinger/DuMont, 1996), p. 227, n. 6.

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 59–60; 97, pl. 16; 110.

Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 184; 204–05, cat. 47 (ill.); 317, cat. 47. Translated by Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, with support from Nada Kerpan for the texts by Linda Nochlin, as Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 184; 204–05, cat. 47 (ill.); 317, cat. 47.

Colin B. Bailey, “Portrait of the Artist as a Portrait Painter,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), p. 19. Translated as Colin B. Bailey, “Portrait de l’artiste en portraitiste,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, trans. Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), p. 19.

John B. Collins, “Seeking l’Esprit Gaulois: Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette and Aspects of French Social History and Popular Culture” (Ph.D. diss., McGill University, 2001), p. 86.

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), pp. 246 (ill.), 264.

Sotheby’s, Impressionists and Modern Art Evening Sale, sale cat. (Sotheby’s, London, June 23, 2003), pp. 16, fig. 2; 17.

Robert McDonald Parker, “Topographical Chronology 1860–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), p. 279. Translated as Robert McDonald Parker, “Chronologie,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), p. 279.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), p. 77, cat. 30 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), p. 77, cat. 30 (ill.).

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 2, 1882–1894 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2009), p. 335, cat. 1229 (ill.).

Anne Distel, Renoir (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2009), pp. 228–29, ill. 211.

Colin B. Bailey, Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting, exh. cat. (Frick Collection/Yale University Press, 2012), p. 199.

Other Documentation

Bernheim-Jeune Documentation

Inventory number

Bernheim-Jeune no. 19566

Photograph number

Photo Bernheim-Jeune no. 10751

Other Documents

Label (fig. 2.46)

Purchase receipt

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Number

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: 12 3/4 / 57 / 69 3/4 (fig. 2.24)

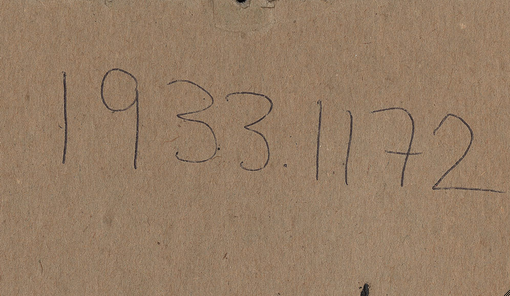

Number

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: handwritten script (pen)

Content: 1933.1172 (fig. 2.31)

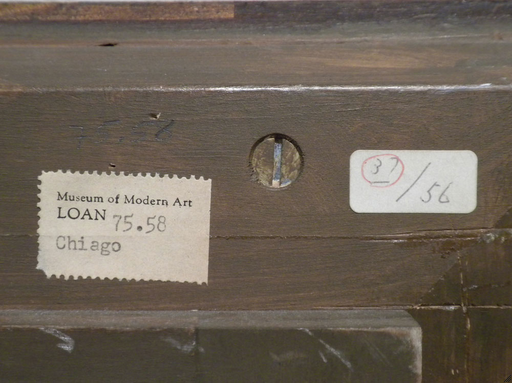

Number

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script on white label

Content: 37 / 56 (fig. 2.26)

Number

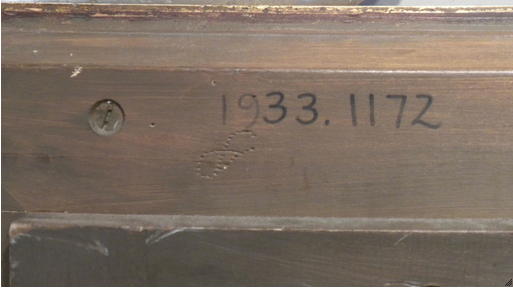

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script (black marker)

Content: 1933.1172 (fig. 2.27)

Label

Location: frame verso

Method: printed label (partial)

Content: cornice (fig. 2.28)

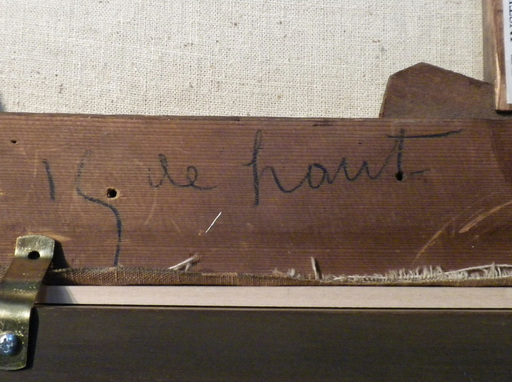

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: [15] de haut (fig. 2.29)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: red stamp

Content: F (fig. 2.30)

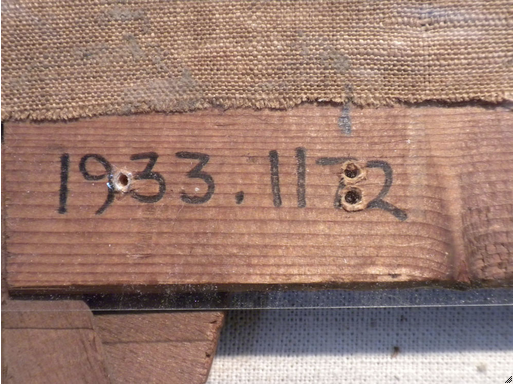

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: 2840 (fig. 2.32)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 35 [. . .] (fig. 2.33)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: 20 3/8 × 24 5/16 (fig. 2.44)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue pencil)

Content: 19566 (fig. 2.34)

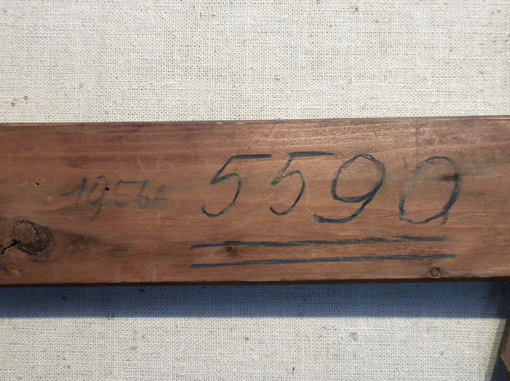

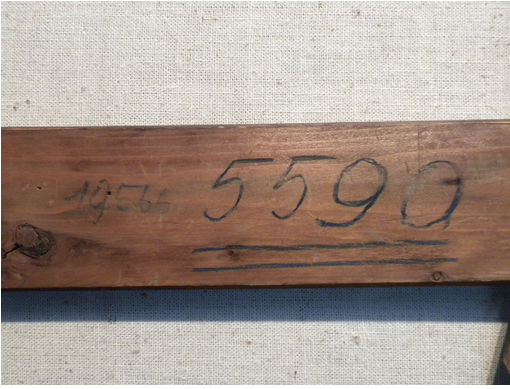

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue pencil)

Content: 5590 (fig. 2.16)

Pre-1980

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: black stamp or stencil

Content: 12 (fig. 3.60)

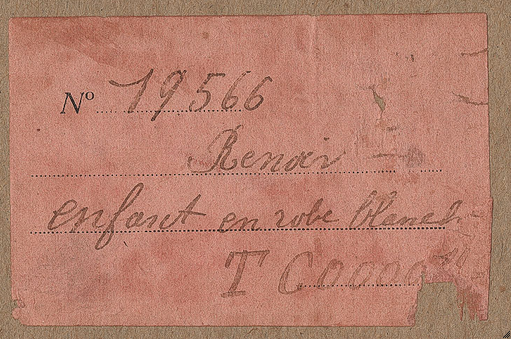

Label

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: handwritten script (ink) on pink label

Content: No 19566 / Renoir / enfant en robe blanch[e] / TC0000[. . .] (fig. 2.45)

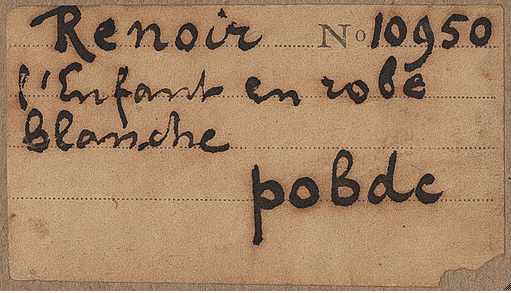

Label

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: handwritten script (ink) on brown label

Content: Renoir No 10950 / l’Enfant en robe / blanche / pobdc (fig. 2.36)

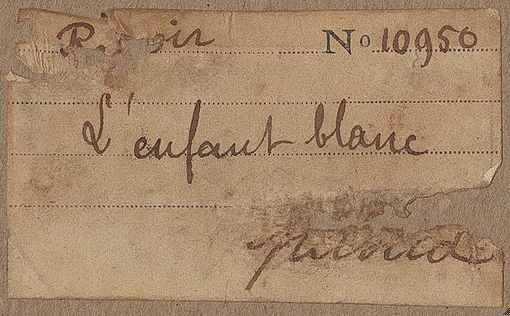

Label

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: handwritten script (ink) on brown label

Content: R[en]oir No 19050 / L’enfant blanc / [p . . . d] (fig. 2.37)

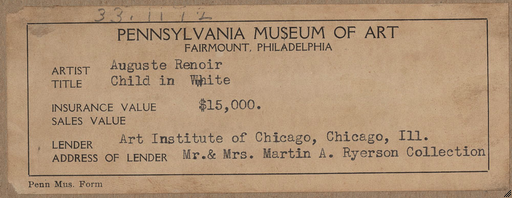

Label

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: handwritten script (graphite) on printed and typed label

Content: [handwritten] 33.1172 / PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ART / FAIRMOUNT, PHILADELPHIA / ARTIST Auguste Renoir / TITLE Child in White / INSURANCE VALUE $15,000. / SALES VALUE / LENDER Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. / ADDRESS OF LENDER Mr.& Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection / Penn Mus. Form (fig. 2.38)

Label

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: printed and typed label

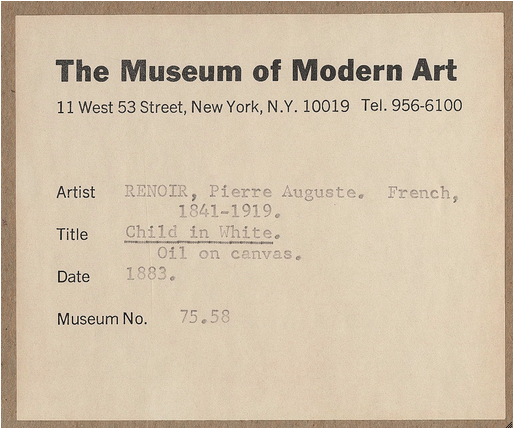

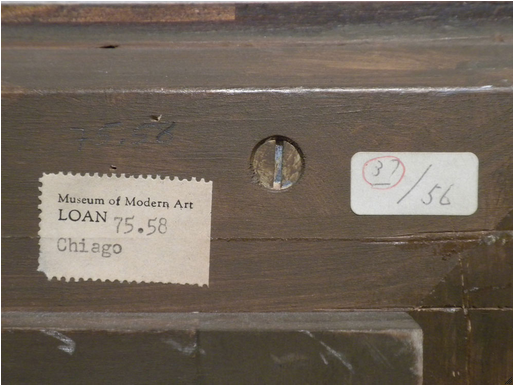

Content: The Museum of Modern Art / 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 / Artist RENOIR, Pierre Auguste. French, / 1841–1919. / Title Child in White. / Oil on canvas. / Date 1883. / Museum No. 75.58 (fig. 2.39)

Label

Location: frame

Method: printed and typed label

Content: Museum of Modern Art / LOAN 75.58 / Chiago [sic] (fig. 2.26)

Post-1980

Stamp

Location: previous backing board (preserved in conservation file)

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory 1980–1981 (fig. 2.13)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 2.40)

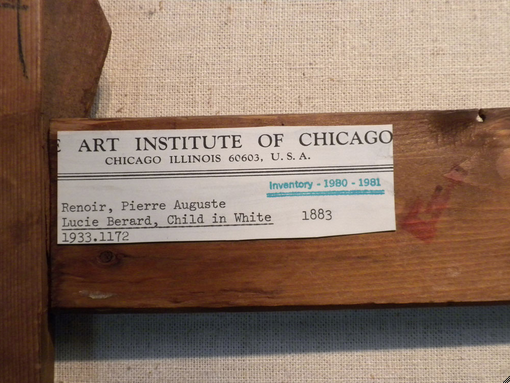

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed and typed label with blue stamp

Content: ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / [blue stamp, center right] Inventory—1980–1981 / Renoir, Pierre Auguste / Lucie Berard, Child in White 1883 / 1933.1172 (fig. 2.30)

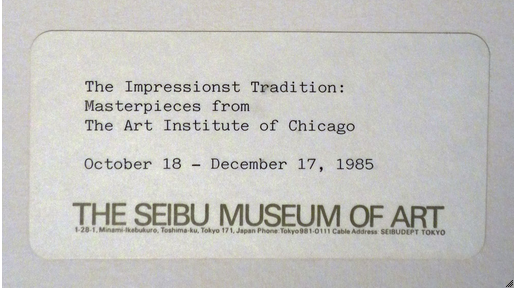

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: The Impressionist Tradition: / Masterpieces from / The Art Institute of Chicago / October 18–December 17, 1985 / THE SEIBU MUSEUM OF ART / 1-28-1, Minami-Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku, Tokyo 171, Japan Phone: Toyko981-0111 Cable Address: SEIBUDEPT TOKYO (fig. 2.41)

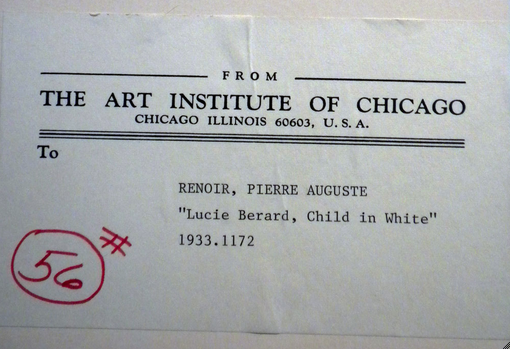

Label

Location: backing board

Method: handwritten script (red pen) on printed and typed label

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / To / RENOIR, PIERRE AUGUSTE / “Lucie Berard, Child in White” / 1933.1172 / [handwritten, lower left] 56# (fig. 2.42)

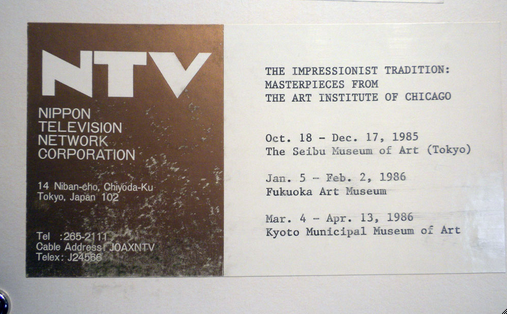

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: [left] NTV / NIPPON / TELEVISION / NETWORK / CORPORATION / 14 Niban-cho, Chiyoda-Ku / Tokyo, Japan 102 / Tel :265-2111 / Cable Address: JOAXNTV / Telex: J24566 / [right] THE IMPRESSIONIST TRADITION: / MASTERPIECES FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / Oct. 18–Dec. 17, 1985 / The Seibu Museum of Art (Tokyo) / Jan. 5–Feb. 2, 1986 / Fukuoka Art Museum / Mar. 4–Apr. 13, 1986 / Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art (fig. 2.43)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age / Cat.No.: 47 / Artist: Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Title: Child in a White Dress (Lucie Berard) / Owner: Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 2.49)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / “Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age” / October 17, 1997–January 4, 1998 / 47 / Pierr-Auguste Renoir [sic] / Child in a White Dress (Lucie Berard) / The Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 2.15)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (X-NiteCC1 filter, Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Electron Microprobe

Applied Research Laboratories (ARL) electron microprobe analyzer. Analysis was carried out at McCrone Associates, Chicago, Illinois.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 16.74).