Cat. 15

Woman Mending

1895

Oil on canvas; 64.6 × 54 cm (25 7/16 × 21 1/4 in.)

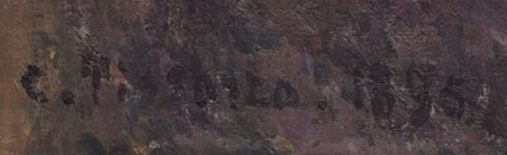

Signed and dated: C. Pissarro 1895. (lower right, in dark blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mrs. Leigh B. Block, 1959.636

Pissarro refers specifically to this imposing figure picture in a letter to his eldest son, Lucien, written from Paris on Tuesday, December 4, 1895:

I’ve almost finished my large figure paintings. Finished meaning I have left them in the studio to simmer before adding in the final touches, that final sensation which will give them life. Alas, until I can work out this last point, nothing can really be considered finished!! . . . While I wait for this sensation to direct my final touches, I am doing some figure studies of Rosa. I am moving along with more confidence and am actually quite satisfied with a canvas size fifteen that I’ve finished, entitled Woman Mending. It has a lot in common with my figure paintings from 1882–83 but rendered with a brighter glow.

Then, a little more than a month later, on Tuesday, January 15, 1896, this time from his farm in Éragny just before departing for a painting campaign in Rouen, Pissarro again wrote to Lucien about these figure pictures. “I’ve completed four size ten and fifteen canvases depicting Rosa. I’ve also finished my three size thirty canvases of nudes. With all that I still have in terms of older works[,] the total amount of figure paintings should amount to about fifteen.”

Rosa was the Pissarro family’s maid at the time, and she appears in several of the artist’s figure paintings, namely Woman Called “La Rosa,” Pulling up Her Stocking (1895; fig. 1.1 [PDRS 1099]); The Little Housemaid, Called “La Rosa” (1896; fig. 1.2 [PDRS 1111]); The Little Flemish Housemaid, Called “La Rosa” (1896; fig. 1.3 [PDRS 1112]); and Head of a Young Girl, Called “La Rosa,” in Profile (1896 [PDRS 1113]). According to the 1939 Pissarro catalogue raisonné, the title of number 1112 (The Little Flemish Housemaid, Called “La Rosa”) was Little Flemish Housemaid, suggesting that Pissarro’s maid was of Belgian origin. Although the artist’s other paintings featuring Rosa do not specify her ethnicity, it is not improbable that she was Flemish. Pissarro had spent several months in Belgium from late June through early October 1894. He had gone with Julie and their son Félix, but they were forced to stay longer because of the arrest of anarchists in Paris, including many of his friends, on the very day he arrived. Although he doesn’t mention anything about it in his numerous letters to friends and family members, it is likely that Julie engaged the services of a maid to help her with domestic affairs and returned to Éragny with the young woman, whom the family called by the utterly un-Flemish name of “Rosa.”

Whereas the identity of the maid is uncertain, from the letters he wrote while in Belgium, it is clear that Pissarro’s decision to stay there for such a long period of time was motivated by his fear of being linked to anarchist activities. In a letter to Lucien dated July 30, 1894, he described an excursion to the province of Zeeland accompanied by his friends and anarchist sympathizers Élisée Reclus and Théo van Rysselberghe (a Belgian Neo-Impressionist painter). Pissarro had become extremely nervous and apprehensive about returning to France, especially in light of President Sadi Carnot’s recent assassination by an anarchist on June 24 in Lyon. He lamented to Lucien:

When one thinks of the repercussions of a [hotel] caretaker allowed to open mail and that a simple act of exposure can land someone in front of a firing squad or even in jail without being able to defend oneself! One by one, our friends are leaving France: [Octave] Mirbeau, Paul Adam, Bernard Lazare, [Théophile Alexandre] Steinlen, and [Jean-Louis] Hamon were supposed to be arrested but were able to escape in the nick of time. Poor Masximilien Luce was apprehended; someone probably reported him. Since I am mistrustful of certain people in Éragny who have it in for us I too will keep my distance.

It seems clear from the letters to Lucien that the Rosa picture mentioned so specifically in 1895 was begun—and possibly completed—in Éragny, between Pissarro’s various trips to Paris in the latter months of the year. A careful reading of his numerous epistles from Paris makes it clear that he used his time in the city for business and to reflect on work done in Éragny and elsewhere. Like its smaller, dated companion, Woman Called “La Rosa,” Pulling Up Her Stocking (fig. 1.1), it was probably painted in the artist’s second-floor studio in the barn of the family farm, while two of the pictures referenced in the second letter and dated 1896 were presumably painted in the Pissarros’ Éragny house itself. It is likely that these latter paintings are those entitled The Little Housemaid, Called “La Rosa” (fig. 1.2) and The Little Flemish Housemaid, Called “La Rosa” (fig. 1.3) as the pictures include double doors and parquetry flooring. Rosa also appears slightly disoriented in both pictures, perhaps due to the last-minute commotion of Pissarro’s impending travel to Paris and then Rouen, where he arrived on January 20, 1896. As his correspondence attests, the artist was back in Éragny by mid-December 1895, returned to Paris near the end of December, and was back in Éragny again right after New Year’s 1896, staying until January 15. This means that after being in Paris in December 1895, Pissarro stayed in the small town for a few uninterrupted weeks before leaving for the capital again on January 15, 1896. This indicates that he may have painted the 1896 pictures of Rosa in stages. They are also among the very rare glimpses into Pissarro’s domestic life because he, like Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet, usually kept his art and family life separate.

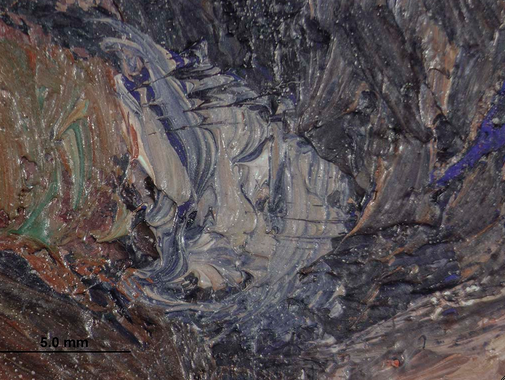

The 1895 pictures of Rosa (including Woman Mending and Woman Called “La Rosa,” Pulling up Her Stocking display Pissarro’s preoccupation with pattern—particularly the interplay of various striped fabrics. Although he does not mention Édouard Vuillard’s work in his letters until later, this suggests that Pissarro had seen and was responding to the pattern-obsessed aesthetic of the young artist, whose paintings for Misia Godebski Natanson and Thadée Natanson he saw in an exhibition at Siegfried Bing’s gallery, the Maison de l’Art Nouveau (see fig. 1.4). In many ways, the stripes almost become the principal subject of the painting, which contrasts their direction, width, hue, and character in the sitter’s blouse and in the table covering, which looks almost like it could have been a gift from Paul Gauguin (see fig. 1.5). Recent technical examination conclusively proves that Pissarro fiddled with the stripe patterns as much as he did with the woman’s pose, and that he seems to have reveled in the striped visual rhythm of her fingers as it contrasts with the striped fabric she wears (fig. 1.8; see Paint Layer in the technical report). Interestingly, the other two paintings of Rosa (fig. 1.2 and fig. 1.3) show her in plain cotton clothing in a relatively bare room with off-white paneled walls and doors—what remains to this day a “correct” bourgeois interior. Although Pissarro shunned middle-class values and always complained about lacking money, he and his family lived in a home that was much more substantial and “bourgeois” than the rural farmhouse of their far-richer friend, Claude Monet. And the fact that Pissarro painted several works using the family maid as a model suggests that he was affected by his newfound prosperity and status as a homeowner (he purchased the Éragny property in 1892).

In Woman Mending, Pissarro elected to use a conventional three-quarter pose, perhaps to undercut the “portraiture” quality that the picture otherwise possesses. He himself related it to several of his so-called peasant portraits of the early 1880s, which include the Art Institute’s own Young Peasant Having Her Coffee (1881; cat. 10) and two other paintings featuring rural women in striped attire from the same period (fig. 1.6 and fig. 1.7 [PDRS 640 and 661]). Detailed technical analysis of Woman Mending reveals that it was executed in several sessions separated by enough time that the paint could dry between them. This analysis is confirmed by Pissarro’s movements in the last months of 1895, when he seems virtually to have oscillated between the Hôtel de Rome, his favorite Paris hotel, and his Éragny studio, where Rosa posed for him before it became too cold for him to leave the house—prompting the last two paintings of her (see fig. 1.2 and fig. 1.3) to be made there instead.

Richard R. Brettell

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Pissarro executed this portrait on a no. 15 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size, [glossary:commercially primed] [glossary:canvas] beginning with a preparatory sketch in dry media, perhaps charcoal or black chalk. After reinforcing the basic sketched contours with fluid blue paint, he added additional, isolated folds and details in blue paint before adding heavier paint. The work was executed in a limited number of [glossary:wet-in-wet] campaigns with paint of an almost paste-like consistency; each campaign was allowed to dry before additional paint was added. The stiff consistency of the paint in combination with the use of small brushes led to a heavily textured surface, a texture that was reinforced with successive campaigns for a variety of effects.

The artist made several small changes to the figure’s posture and selected areas of the background throughout the painting process. The thickness of the paint layers in earlier stages leaves some previous compositional choices still visible under normal viewing conditions, such as along the outer edge of the figure’s left sleeve. The artist changed the angle of this arm, successively trimming the upper arm and moving it closer to the body; as a result, changes were also made to the forearm, elbow, and fingers. Along the figure’s right side, the shoulder, elbow, bottom edge of the forearm, and thimbled finger were all adjusted. Pissarro altered the stripes of the figure’s costume throughout (in part along with the alterations to the posture and placement of the arms) and adjusted the hanging fabric, which now falls more heavily into the sitter’s lap, creating a depression in the skirt. He also slightly changed the placement of the figure’s left knee, moving it apart from her right knee and further toward the edge of the picture. Smaller changes to the work include adjustments to the figure’s bun, changes to the table covering both behind the chair at left and in the pattern and angle in the right foreground, and the transition in the background at the upper right from dark to light.

The heavily painted work was executed with medium to small brushes, both round and flat, using a variety of colors both straight from the tube, as in the deep-blue accents on the fabric, and mixed on the [glossary:palette], as exemplified by the base flesh-tone color and the muted tones in the hair. Some wet-in-wet details, such as the flowers at the upper right, appear to comprise some of the final touches. The heavily textured work was recently cleaned and remains unvarnished.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 1.9).

Signature

Signed and dated: C. Pissarro 1895. (lower right, in dark-blue paint) (fig. 1.10 and fig. 1.12).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax, commonly known as linen.

Standard format

The original size of the canvas was very close to its current size, 64.6 × 54 cm. This corresponds to a no. 15 portrait (figure) standard-size (65 × 54 cm) canvas.

Weave

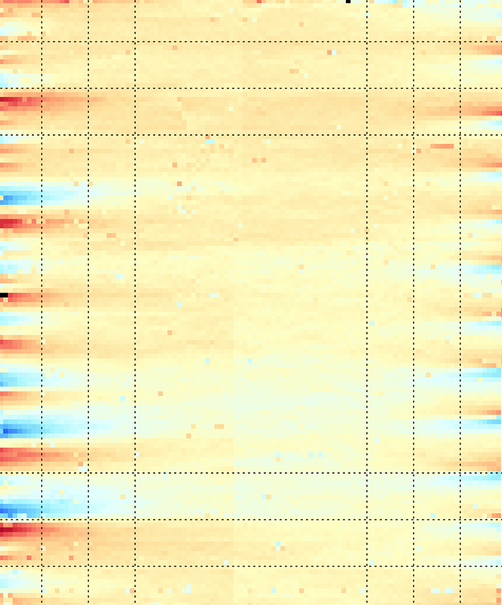

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 34.5V (0.8) × 32.6H (1.1) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

The canvas is a very fine [glossary:weave] with [glossary:cusping] corresponding to the original tack placement. Strong [glossary:primary cusping] along the left side, seen in the [glossary:thread-angle map], relates to commercial preparation (fig. 1.11).

Stretching

Current stretching: The work was restretched after it was lined; the lining canvas was nailed to the [glossary:stretcher] first, followed by the original canvas above.

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the [glossary:X-ray], the original tacks were placed approximately 5–8 cm apart.

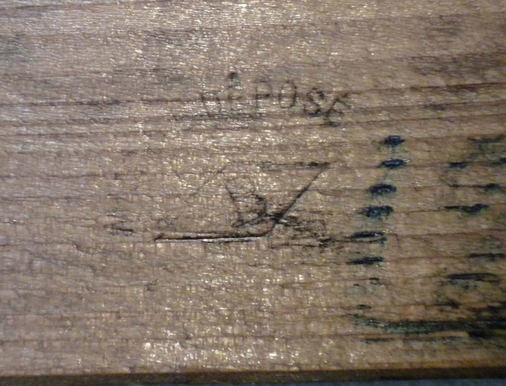

Stretcher/strainer

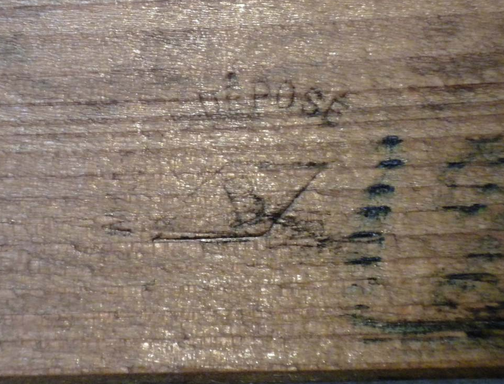

Current stretcher: The painting appears to have retained its original stretcher. The work has a five-member mortise and tenon, keyable stretcher with a horizontal [glossary:crossbar], or a chassis à clés. The modèle déposé B stamp on the crossbar is the registered trademark of Bourgeois Ainé (fig. 1.13). Depth: 1.6 cm.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black stamp

Content: MODÈLE DÉPOSÉ / <B> (fig. 1.13)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined.

Ground application/texture

The [glossary:ground] appears to be a single layer, is commercially applied, and extends to the edges of the [glossary:tacking margins]. It is relatively thin and appears somewhat powdery and prone to cracking and flaking along the turnover.

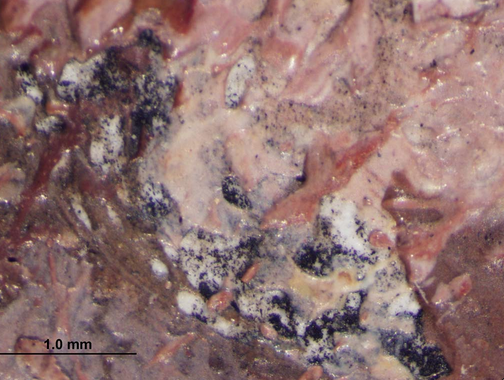

Color

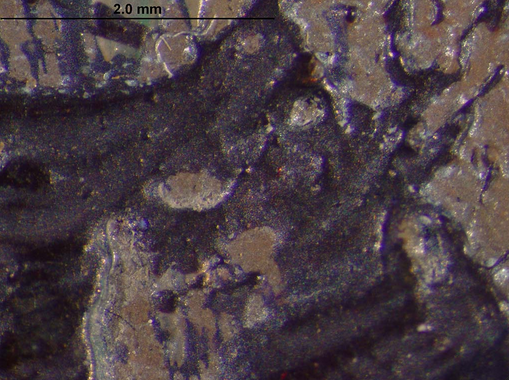

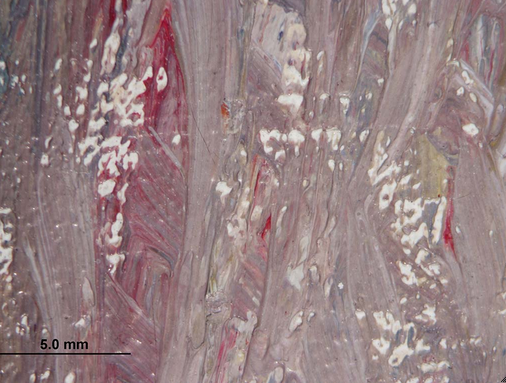

The ground appears white in [glossary:stereomicroscopic examination], with no visible colored particles (fig. 2.24). Visual examination of [glossary:cross sections] revealed traces of dark brownish-black and yellow particles.

Materials/composition

[glossary:XRF] analysis suggested that the ground is composed of predominantly lead white with iron oxides and calcium compounds, such as calcium carbonate and/or calcium sulfate. The [glossary:binder] is estimated to be [glossary:oil].

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

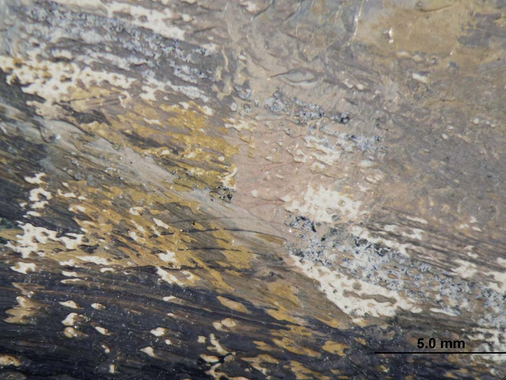

Pissarro outlined the major features of the composition including the figure, her facial features, and the table in long, sweeping lines. In some areas, he left the interface between features exposed and the underdrawing is visible under normal viewing conditions, as, for example, along the top of the table at right (fig. 2.15).

Medium/technique

Pissarro appears to have first outlined the major contours in charcoal before fixing the [glossary:underdrawing] in a more permanent dilute, dark-blue paint. Some areas, such as the figure’s nose, show evidence only of the initial black sketch (fig. 2.16), which may suggest that the artist drew in greater detail with dry media and only set more important features with a blue painted line. In many areas the subsequent paint has picked up excess charcoal particles, resulting in the appearance of a single drawn line (fig. 2.17).

Revisions

In many areas, parallel lines suggest the artist was slightly modifying contours throughout the drawing process. Due to the large amount of black particles in the paint layer in some areas, it is likely that the original drawing, in dry media, featured numerous changes and perhaps more detailed features that were not transcribed with blue paint and therefore were swept into the paint layer during execution (fig. 2.18). Most discernible compositional changes appear in the paint stages (see Paint Layer).

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revision

Pissarro executed this work in a limited number of campaigns, applying thick, paste-like paint in dabs and cross-hatched patterns, and dragging successive strokes over the texture of the dry paint beneath, giving the work a heavily textured quality. The artist began reinforcing and expanding upon his contour sketch with wider strokes in dilute blue paint to indicate some additional folds and the pattern of the figure’s clothing. In some areas evidence of these early strokes can be seen in skips in the upper paint layers; this is especially evident at the figure’s right shoulder (fig. 2.19). Each subsequent campaign was applied thickly and apparently allowed to dry before the next layers were added, a technique which leaves some of the artist’s changes visible under normal viewing conditions, including the figure’s left arm (fig. 2.20). Much of the work is thickly painted, and, in some areas, the interface between areas is thinly veiled, revealing underdrawing, [glossary:underpainting], and the bright white ground. Throughout the composition Pissarro’s use of thick, paste-like paint and short strokes results in a number of skips, giving much of the painting an almost deceptively open quality despite its heavy texture. One of the most heavily worked areas is the face, where successive layers of slightly more liquid paint have reinforced the dabbing texture to such a degree that only small dimples remain between strokes. In some areas, like the spot between the eyes and cheeks, this effect is contrasted with the finer texture of the canvas weave, revealed in a more thinly painted area (fig. 7.59). Each campaign was applied wet-in-wet with a selection of colors both mixed and unmixed on the palette, resulting in subtle modulations of color throughout. Looking closely at the hair and flesh tones, especially throughout the hands and fingers, the extent of the color variation is clear (fig. 2.22). In specific areas the artist employed a deep blue, almost entirely unmixed, to add a coloristic richness; see, for example, the fabric the woman holds.

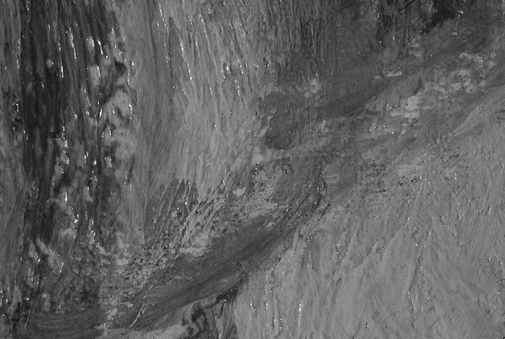

Pissarro made many changes to the figure’s posture and clothing throughout the painting process. Transmitted and reflected infrared images, as well as the X-ray, indicate that the artist first placed the figure’s left sleeve further to the right, as if the arm were further away from the body or bent at a slightly different angle. The outer edge of this sleeve shows evidence of multiple changes, some visible under normal viewing conditions, as the artist successively slimmed the sleeve until reaching the current profile. These images also indicate that the angle of the forearm and the placement of the elbow were adjusted along with the slimming or moving of the sleeve; originally the artist indicated a slight space between the figure’s lap and elbow, as if the elbow were slightly raised. The current placement is a slightly more relaxed one and reveals more of the table covering in the background. The X-ray and infrared images also indicate slight changes to the figure’s right arm, including the slope of the shoulder near the neck, the outside edge of the elbow, and the upper edge of the cuff and arm. The movements in both sleeves also required slight adjustments to the striped pattern along the arms; minor changes to the striped pattern are also seen above the figure’s waistband, near her collarbones, and on the upper part of her right arm. Infrared examination also shows that Pissarro changed the placement of the figure’s left knee. He originally painted a space between her lap and the edge of the picture frame, but then he altered her pose so that her skirt now abuts the side and appears to almost extend off the canvas, making her legs appear longer, with knees slightly apart. A contour visible in the X-ray may indicate that the slope of the skirt from the figure’s arm to the lower right was more of a diagonal and may correspond with this early placement of the knee.

Smaller changes to the work surround the figure’s hands and are mostly visible in the infrared images: the placement of the fabric, her left fingers, the thimble on her right hand, and the placement of the thimbled finger were all adjusted. At left, a contour in the infrared appears to extend from the chair back diagonally back into space. It is unclear whether this contour is associated with the chair or is the initial indication of the table covering. Other alterations to the background include the right arm of the vase and the break in space behind it. To the left of the vase, the green-gray and dark mauves of the rest of the background appear to extend to the edge of the vase and were later painted with a wet-in-wet transition between colored areas; remains of the dark-grayish background are seen immediately to the left of the vase and above and behind the flowers at the very top of the composition. The upper slope of the table near the right edge was modified, and the striped pattern of the table covering hanging down near the front was muted. The artist appears to have established the figure’s face and hair early in the process; the only apparent change is seen in the infrared image, showing slightly more volume at the crown of the head.

Pissarro appears to have worked over the entire canvas at once. Having first drawn his basic composition in a combination of media, he often painted up to the edges of forms, leaving a slight gap between them. In other areas there is a sense of back and forth: he established the basic placement of the figure, as drawn, and then began the background; as new contours were established and heavier paint added to the figure, more background paint was brought up to the edges of the figure, covering previous choices and in some cases overlapping the outer edges. In the figure’s hair the upper layers and wavy tendrils were added on top of the already dry background. The flowers at the upper right seem to be among the last things painted, and are executed largely wet-in-wet with small, flat brushes (fig. 2.23).

Painting tools

Mostly small, soft-bristle round and flat brushes, with strokes up to 0.5 cm.

Palette

XRF analysis suggests the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, vermilion, iron-oxide red and/or yellow, emerald green, chromium-containing pigment such as chrome yellow and/or viridian, and possibly ultramarine and Prussian blue.

Stereomicroscopic examination suggests the presence of red lake throughout the composition (fig. 2.24).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The work is currently unvarnished, with minor residues of [glossary:natural-resin varnish] in areas of heavy [glossary:impasto]. A natural resin varnish was applied prior to 1961 and removed, along with a subsequent [glossary:synthetic varnish], in 2013. It is unclear whether the [glossary:varnish] noted in 1961 was original to the painting.

Conservation History

The work was examined in 1961, when it was noted to have an [glossary:aqueous lining] and heavy varnish and grime layers. Subsequent treatment included aqueous cleaning to remove grime and a spray application of L-46 varnish. The painting was treated in 2012, when synthetic and natural-resin varnish layers were removed. Previous [glossary:retouching] was present around the edges, extending well into the composition in some areas, and was removed where possible. Consolidation of losses around the edges and minimal retouching and filling were undertaken, and the work was left unvarnished.

Condition Summary

The work is in good condition, unvarnished with some residues of natural-resin varnish in areas of impasto and old retouching around the perimeter. The work is aqueously lined to a second canvas but seems to have retained its original stretcher; it is well stretched and planar. There is an old loss in the figure’s hair above the ear that has been filled and inpainted. Flaking along the turnover has been consolidated and appears stable at this time.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame is not original to the painting. It is an American, 1950/60 reproduction of a Louis XV frame with swept sides and pierced rocaille corner and center cartouches and an independent fillet and cove liner. The frame has water and oil gilding over red bole on gesso. The rails are highly burnished, as are portions of the ornament, and the rails are also heavily toned with an overall umber and white wash. The liner is coarsely gilded and asymmetric to accommodate the frame to the painting. The carved basswood moldings are mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is ovolo with running ovate; scotia side; torus swept rails; quirked scotia face with pierced rocaille shell center and pierced rocaille foliate corner cartouches with trailing flowers on a plain bed; flat, bed-level frieze; ogee with leaf-tip ornament on a straight-lined bed; and independent fillet and cove liner (fig. 2.41).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

By descent from the artist (died 1903) to his son, Ludovic-Rodolph (Rodo) Pisssarro, Paris, 1904.

Sold by Ludovic-Rodolph (Rodo) Pissarro, Paris, to Sam Salz, New York, by Dec. 1950.

Sold by Sam Salz, New York, to Mrs. Leigh B. (Mary Lasker) Block, Chicago, Dec. 1950.

Given by Mrs. Leigh B. (Mary Lasker) Block, Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, beginning in 1959.

Exhibition History

Copenhagen, Valdemar Kleis, Katalog over Martsudstillingen (1886–1911), Mar. 1911, cat. 34.

London, Stafford Gallery, Pictures by Camille Pissarro, from Oct. 13, 1911, cat. 11.

Zurich, Switzerland, Moderne Galerie, Camille Pissarro, July 11–Aug. 31, 1913, cat. 7.

Paris, Galerie de l’Élysée, C. Pissarro: Des peintures et des pastels de 1880 à 1900 environ, Apr. 23–May 5, 1948, no cat.

Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Leigh Block, Oct. 19, 1976–May 20, 1977, no cat.

Tokyo, Seibu Museum of Art, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], Oct. 18–Dec. 17, 1985, cat. 49 (ill.); Fukuoka Art Museum, Jan. 5–Feb. 2, 1986; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Mar. 4–Apr. 13, 1986.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Camille Pissarro, Nov 19, 2005–Feb. 19, 2006, cat. 98 (ill.); Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, Mar. 4–May 28, 2006.

Selected References

Katalog over Martsudstillingen, 58 Vesterbrogade, exh. cat. (1911), p. 2, cat. 34.

Stafford Gallery, Exhibition of Pictures by Camille Pissarro, 1830–1903, exh. cat. (Stafford Gallery, 1911), p. 10, cat. 11.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son art—son oeuvre, vol. 1, Texte (P. Rosenberg, 1939), p. 210, cat. 934.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son art—son oeuvre, vol. 2, Planche (P. Rosenberg, 1939), pl. 189, cat. 934.

John Rewald, Pissarro (Braun & Cie, [1940]), cat. 48 (ill.).

Frederick A. Sweet, “Pissarro’s Young Woman Mending,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 54, 2 (Apr. 1960), pp. 17–19 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 359.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 48 (ill.), 162–63.

John Maxon, The Art Institute of Chicago (Abrams, 1970), pp. 268 (ill.), 285.

Raymond Cogniat, Pissarro (Flammarion, 1974), p. 73 (ill.).

Christopher Lloyd, Pissarro (Phaidon, 1979), p. 15, pl. 34.

Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro: His Life and Work (Horizon, 1980), p. 291 (ill.).

Christopher Lloyd, Camille Pissarro (Skira/Rizzoli, 1981), p. 98 (ill.).

Christopher Lloyd, “Camille Pissarro: Towards a Reassessment,” Art International 25, 1–2 (Jan. 1982), p. 64 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Seibu Museum of Art, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, and Fukuoka Art Museum, eds., Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], trans. Akihiko Inoue, Hideo Namba, Heisaku Harada, and Yoko Maeda, exh. cat. (Nihon Nippon Television Network, 1985), pp. 104, cat. 49 (ill.); 105 (detail); 154, cat. 49 (ill.).

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, ed., Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, vol. 4, 1895–1898 (Valhermeil, 1989), pp. 127 (letter 1181); 129, n. 2; 149 (letter 1199).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 126 (ill.).

Joachim Pissarro, Camille Pissarro (Abrams, 1993), p. 169, cat. 179 (ill.).

Joachim Pissarro and Stephanie Rachum, Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Innovator, exh. cat. (Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1994), p. 56 (ill.).

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, with the collaboration of Alexia de Buffévent and Annie Champié, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, vol. 1, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Skira/Wildenstein Institute, 2005), pp. 368, 369, 370, 386, 409.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, with the collaboration of Alexia de Buffévent and Annie Champié, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures/Critical Catalogue of Paintings, vol. 3, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Skira/Wildenstein Institute, 2005), p. 694, cat. 1098 (ill.).

Terence Maloon, ed., Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2005), pp. 207; 208, cat. 98 (ill.); 254.

Richard Shiff, “The Restless Worker,” in Terence Maloon, ed., Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2005), p. 38.

Richard Brettell, Pissarro’s People, exh. cat. (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Prestel, 2011), pp. 34–35, fig. 16; 190; 192–93, fig. 147; 268–69, fig. 230.

Other Documentation

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

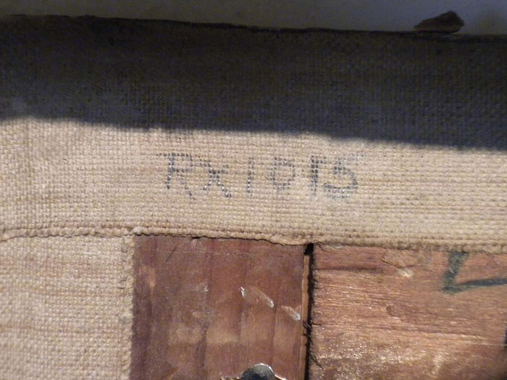

Inscription

Location: canvas [glossary:foldover] (verso)

Method: handwritten script ([glossary:graphite])

Content: RX1015 (fig. 2.25)

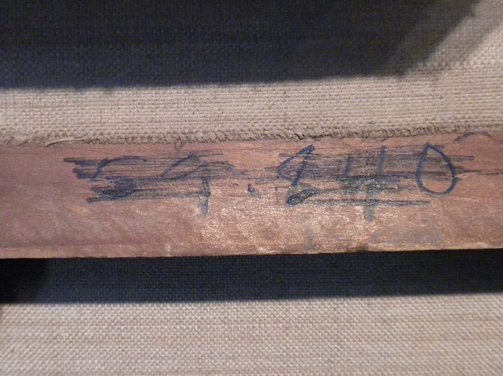

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue crayon/chalk) crossed out

Content: 59.840 (fig. 2.26)

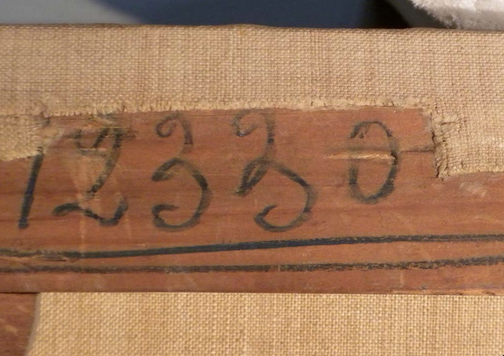

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue crayon/chalk)

Content: 12330 (fig. 2.27)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue crayon/chalk)

Content: 12330 (fig. 2.28)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (red crayon/chalk)

Content: 2 (fig. 2.29)

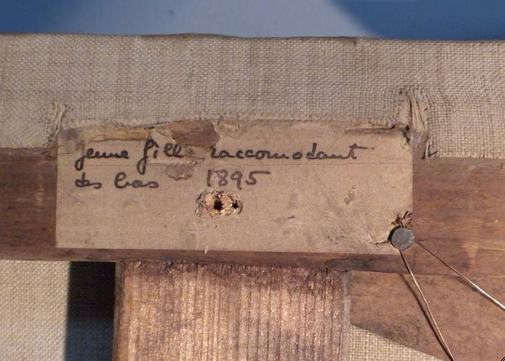

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (black ink) on light brown label

Content: Jeune fille [. . .] raccomodant [sic] / des bas 1895 (fig. 3.57)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (dark ink and graphite) on brown label

Content: S. S. / 73 – New York / [Eas]t Wall, No. 2 (fig. 2.39)

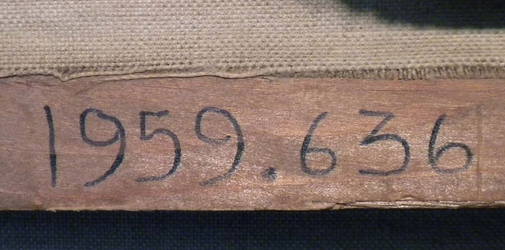

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (black marker)

Content: 1959.636 (fig. 3.58)

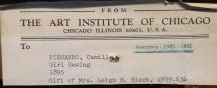

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed and typed label with blue stamp

Content: FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / To / PISSARRO, Camill[e] / Girl Sewing / 1895 / Gift of Mrs. Leigh B. Block, 1959.636 / [at right] Inventory 1980-1981 (fig. 2.30)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black circular stamp

Content: DOU … (fig. 2.34)

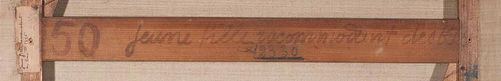

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 50 Jeune fille racommodant [sic] des bas (fig. 2.35)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black stamp

Content: MODÈLE DÉPOSÉ / <B> (fig. 2.36)

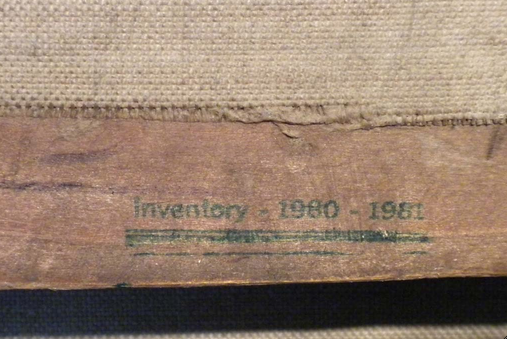

Post-1980

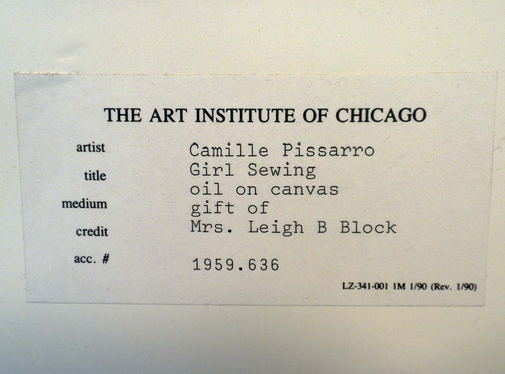

Label

Location: [glossary:backing board]

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Camille Pissarro / title Girl Sewing / medium / oil on canvas / credit / gift of / Mrs. Leigh B Block / acc. # 1959.636 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 2.37)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory – 1980 - 1981 (fig. 2.38)

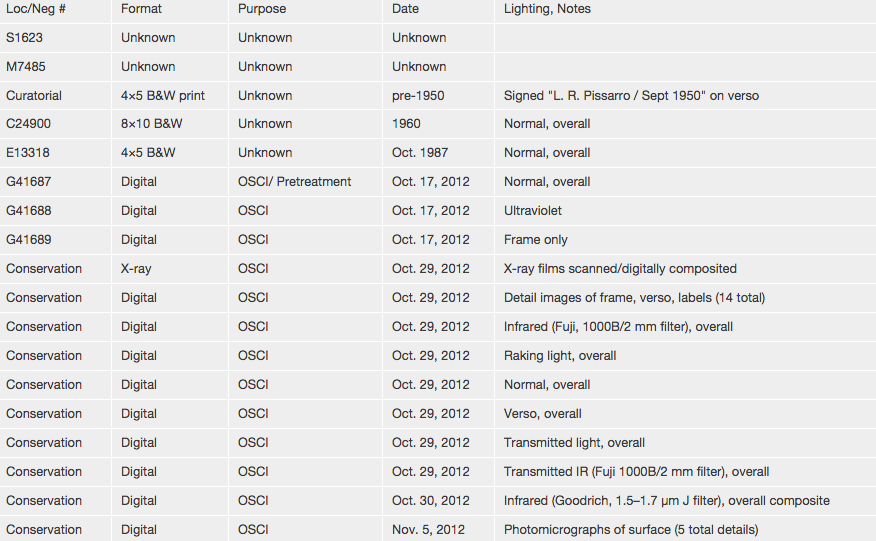

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, and Radboud University, Nijmegen, Neth.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/ Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm), J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Normal-light, raking-light, and [glossary:transmitted-light] overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (B+W UV 010 MRC F-Pro filter and PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and [glossary:cross-sectional analysis] using Zeiss Axioplan2 Research Microscope equipped with reflected light/[glossary:UV fluorescence] and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. (Types of illumination used: [glossary:darkfield], differential interference contrast [[glossary:DIC]], and [glossary:UV].) In situ photomicrographs with Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom Microscope fitted with Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy

Zeiss Universal Research Microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

[glossary:Cross sections] analyzed after carbon coating with Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with Oxford EDS and Hitachi solid-state [glossary:BSE]. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility, Evanston, Ill.

Automated Thread Counting

[glossary:Thread count] and [glossary:weave] information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the George Washington University, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 2.40).