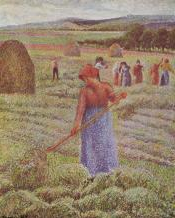

Cat. 12

Haymaking at Éragny

1892

Oil on canvas; 65 × 80.9 cm (25 5/8 × 31 7/8 in.)

Signed and dated: C. Pissarro 1892 (lower left, in blue paint)

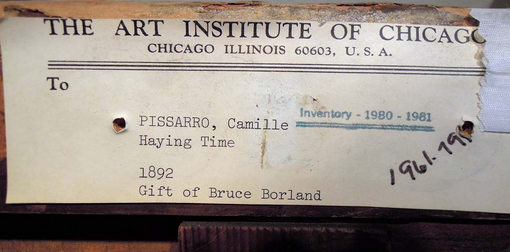

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Bruce Borland, 1961.791

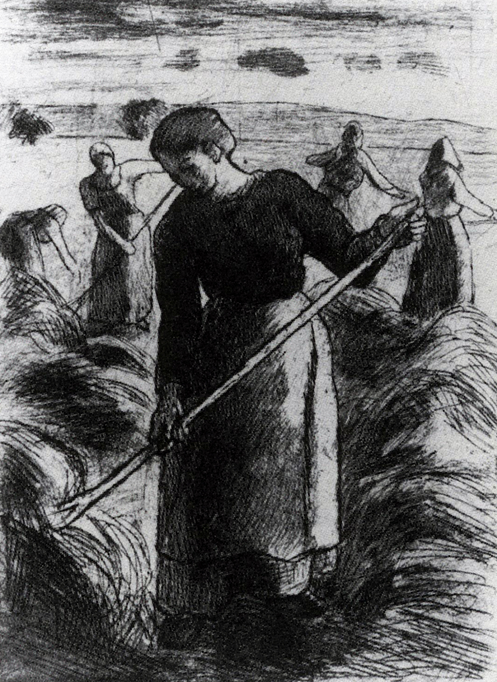

In the last two weeks of March 1893, the gallery owner Paul Durand-Ruel put on a solo show of recent work by Pissarro, just over a year after the artist’s 1892 exhibition. At no other time in the long history of the painter and dealer’s relationship were market conditions sufficiently strong to sustain two such large displays: the 1892 retrospective featured fifty works and the 1893 exhibition forty-six. In 1894 the dealer again organized another monographic Pissarro show, but this one included a mere thirty pieces. Even the artist’s solo exhibition in 1896 did not equal the size of either his 1892 or 1893 shows, with only thirty-five works. The next big monographic shows of comparable size only took place in 1901 and 1903—sadly, however, this last exhibition opened in New York a few weeks after he died. It is safe to say then, that Pissarro’s 1892 and 1893 solo shows were of monumental importance. Haymaking at Éragny was one of the paintings featured (as no. 38) in the 1893 exhibition, which included virtually all of the finished oil paintings Pissarro made that year as well as six works from the 1880s, including one from 1889 (fig. 12.1 [PDRS 866]) that shares the same principal figure of a woman raking.

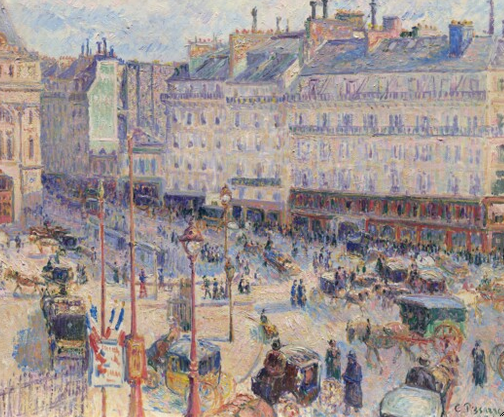

Unlike many earlier Pissarro exhibitions, this one offered neither works on paper, nor any paintings in tempera or gouache. Clearly Durand-Ruel felt that the recent oils were more marketable than the rest of the artist’s output—a complete reversal of his stance in the second half of the 1880s. The exhibition in 1893 was, essentially, divided into groups of paintings with related themes or works made in series, including two series representing the annual floods of the Epte River in Éragny (in 1891 and 1892), a series made in Kew Gardens outside London, a series of winter landscapes of Éragny, and a few other landscapes, also executed in Éragny, representing the area immediately surrounding Pissarro’s house. It is evident that the artist had been moved—and influenced by—the exhibition of Claude Monet’s series of grain stacks (see cats. 27–33 in Monet Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago) presented the year before at Durand-Ruel, Paris; although Pissarro’s own sense of series differed profoundly from Monet’s, he paid his friend the ultimate compliment by arranging his recent works into what one might call a “series of series.” The exhibition ended with Pissarro’s most recently finished urban paintings, which were barely dry when it opened (see fig. 12.2 [PDRS 986]; cat. 13).

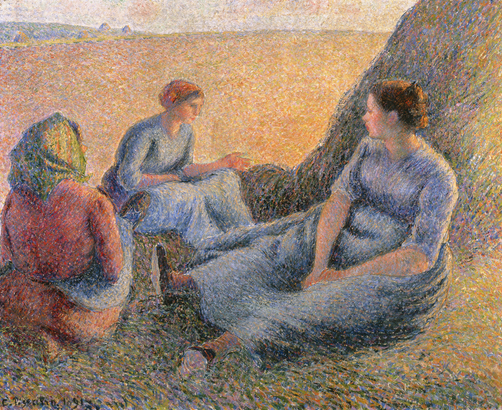

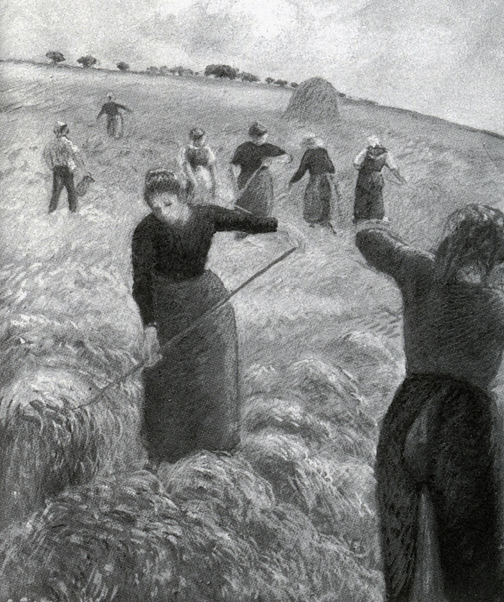

The present work is one of a handful of important, large-scale pictorial investigations of the hay harvest made over the course of Pissarro’s career. The first was his representation of Summer for the cycle of four seasons commissioned by Achille Arosa in 1872 (fig. 12.3 [PDRS 240]). There is also one of his most important large paintings on silk, The Harvest (1882 [PV 1358]; fig. 12.4). A little later Pissarro continued with an important group of Neo-Impressionist harvest pictures, including Haymaking, Éragny (1887; fig. 12.5 [PDRS 848])—from which the figure of the raking woman in the present work ultimately derives—and Haymakers Resting (1891; fig. 12.6 [PDRS 920]). Because Pissarro spent most of the summer of 1892 in London, where he painted the series of works representing Kew Gardens shown in the 1893 exhibition, the vivid scene portrayed in the present work could only have been painted once he returned to Éragny on August 15.

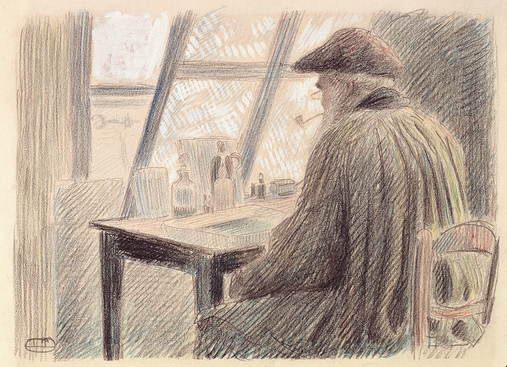

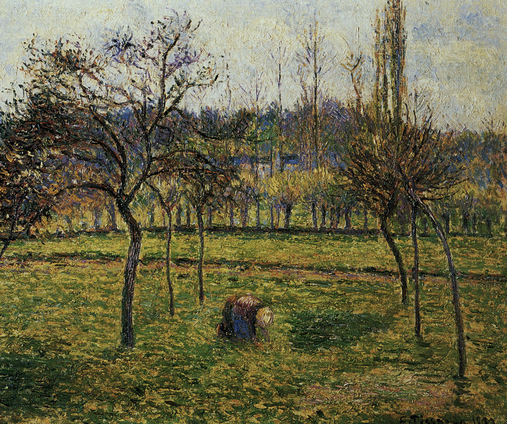

Like most of the Éragny landscapes in the 1893 exhibition at Durand-Ruel, Haymaking at Éragny was painted from the west-facing window on the second floor of the barn that Pissarro had converted into a studio. He chose this space largely because the eye condition from which he suffered made it difficult to paint outdoors; the new arrangement, however, forced him to look down on the landscape rather than stand in the open air, as he had for decades (see fig. 12.7, fig. 12.8, and fig. 12.9). This indirectness is felt in the majority of the Éragny landscapes of 1891–92 and was made permanent in 1893, when, most likely with the proceeds from the Durand-Ruel exhibition, he was able to enhance this studio space significantly, creating a large north-facing window. Pissarro retained the smaller west-facing window, and its view of the alluvial plain of the Epte River toward the village of Bazincourt became a staple of his oeuvre.

What is particularly interesting about Haymaking at Éragny is that Pissarro made it after he returned from London as the new owner of the farm that he had rented since 1883. His wife, Julie, having learned that the property would be sold, had taken advantage of his absence in England to visit Monet, asking him to lend them the money to buy it. Monet complied, forcing the proud—and anarchist—Pissarro to be a landowner, which was completely against anarchist principles: “Property is theft!” famously declared Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whom Pissarro had avidly read. Of even greater personal concern was the fact that the artist now found himself owing money to his old friend, a notion that almost terrified him. The letter he wrote to his wife when he learned of the purchase mixes anger, complaint, resentment, and love in equal measure. Nonetheless, Pissarro had little choice but to accept the situation, particularly after Monet himself intervened by writing to his old friend. Hence, when Pissarro returned to Éragny on August 15, he returned as the owner of a substantial farm with a large house, a barn, and several acres of fields and gardens. The slice of nature that he painted was, for the first time in his life, his own.

Although made from his studio window, Haymaking at Éragny is startlingly accurate. Its surface suggests that the work was completed in two major phases with ample drying time in between; the landscape was done during the first phase, and in the second stage Pissarro added the hay in the foreground and the figure, which he likely borrowed from another work in the studio and, quite possibly, from a lost drawing. This woman also appears in a gouache and a print of 1889 (fig. 12.10 and fig. 12.11), suggesting that it was, by 1892, a stock type that Pissarro could borrow when he needed a plausible, large-scale female harvester to anchor what was one of his largest canvases of the year. The painting represents both a grain field and a small, recently planted orchard just down the hill from his barn. He represented the orchard often later in the year, and a careful examination of the various pictures indicates that he played with the curved forms of the various trees according to the pictorial demands of the particular composition and format. Sometimes he depicted two rows of trees, as in a canvas painted in the fall of the same year (fig. 12.12 [PDRS 963]). On other occasions, the trees seem not to be in rows at all (see fig. 12.13 [PDRS 962]), instead twisting to the right or the left as required compositionally, and to create a curvilinear pattern that relaxes the picture’s planar surface.

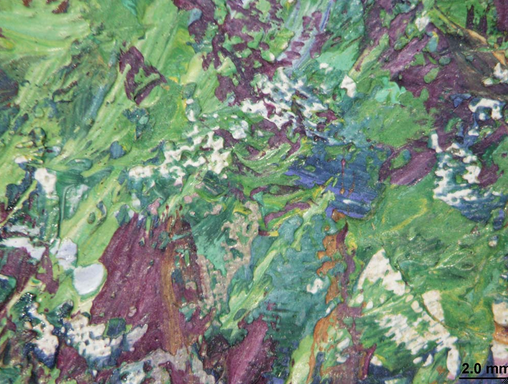

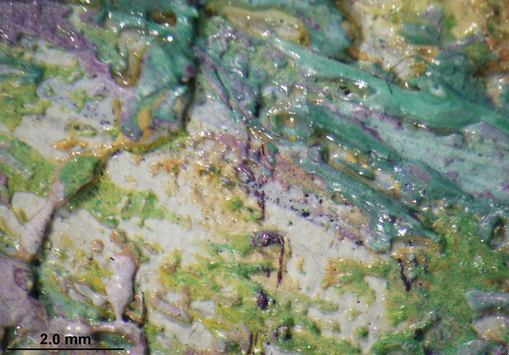

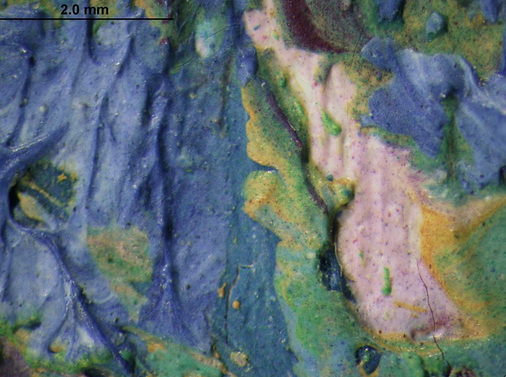

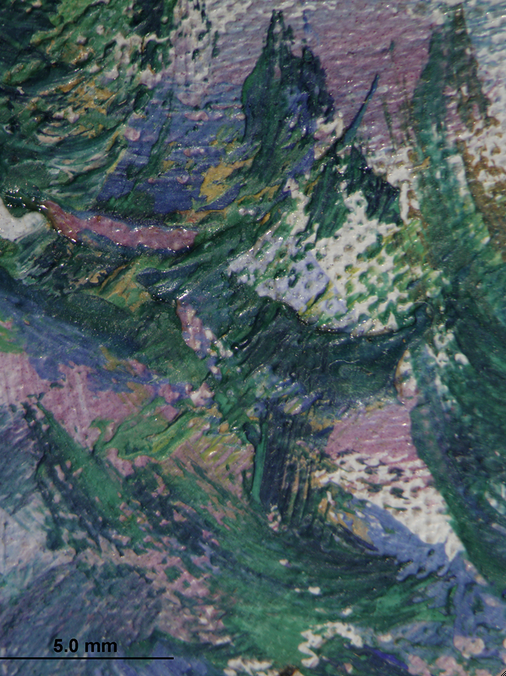

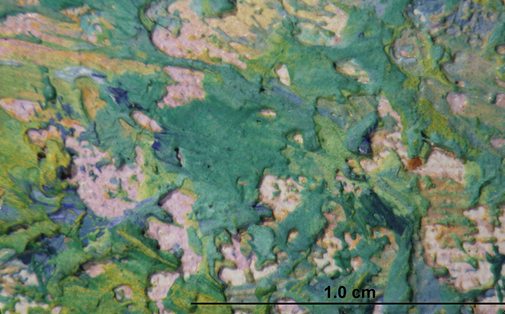

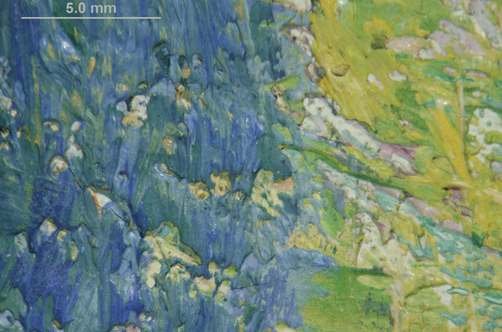

Like all of Pissarro’s canvases from 1892, Haymaking at Éragny exhibits a luscious and chromatically varied pictorial surface, likely the product of his experimentation with various techniques throughout the 1880s. One of the earliest descriptions of Pissarro’s facture was made by C. André in a review in Le français of the 1882 Impressionist exhibition. He observed the unusual effect of what he termed Pissarro’s peinture en relief (relief painting) approach, and characterized the appearance of Pissarro’s canvas surface as a topographical map with peaks and valleys. This deeply furrowed, textured surface—which André considered three-dimensional—was a technique that Pissarro had developed by 1877. The artist used a wide spectrum of hues in relatively small areas on his canvas, which tend toward gray as the colors combine at a distance (fig. 12.14). Therefore, André’s description of these surfaces as “relief painting”—although made as a criticism—was in fact accurate and important. In the latter half of the 1880s Pissarro had learned additional lessons about this kind of multicolored technique through his experimentation with the Neo-Impressionist aesthetic. Since giving up this approach, his entire attitude toward the picture and its surface had relaxed, and the 1893 exhibition, with its small group of earlier works, must have made this clear. Pissarro, the so-called father of Impressionism, had become an Impressionist again—but this time, he had formulated his own approach to picture making: his handling is freer and looser and seems almost effortlessly graceful. Indeed, he even wrote critically about “the Neos,” as he called them, in letters of 1892 and 1893.

The canvas is masterful largely because it is so simply composed, so quickly painted, and so confident in its chromatic explorations. After trying to keep up with the younger generation of artists and experimenting with a new technique in the late 1880s, Pissarro reassessed his artistic approach and stuck to what he knew best.

Richard R. Brettell

Technical Report

Technical Summary

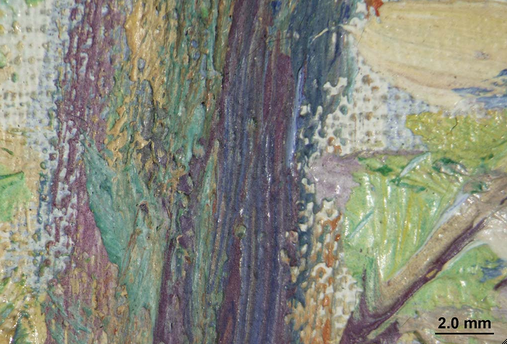

Pissarro began this composition on a commercially primed no. 25 (figure) standard-size canvas. Above the almost-white ground he first executed a contour sketch of the landscape elements, including the thinner trees, in a combination of charcoal or black chalk and very dilute blue paint. Roughly following the contours of this sketch, the artist articulated the individual trees and striations of the landscape in low impasto and a limited palette before moving in with heavier impasto in a wider array of colors. There were minor changes to some of the trees; Pissarro slimmed, straightened, and slightly moved trunks and branches, and he also painted out a large outcropping of foliage that extended into the sky from the tree in the right foreground. The landscape elements and the sky appear to have been built up more or less simultaneously and allowed to dry before the artist added the figures, including the large female figure at the right, and the heaps of hay in the foreground. Pissarro’s handling and manipulation of the paint in the foreground created long, sweeping, ribbonlike lines of wet-in-wet impasto that give the work an almost sculptural quality. The painting is currently unvarnished.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 12.15).

Signature

Signed and dated: C. Pissarro 1892 (lower left, in blue paint) (fig. 12.16). Stereomicroscopic examination suggests that the signature was executed when the upper layers of the ground were still soft (see fig. 12.17).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax, commonly known as linen.

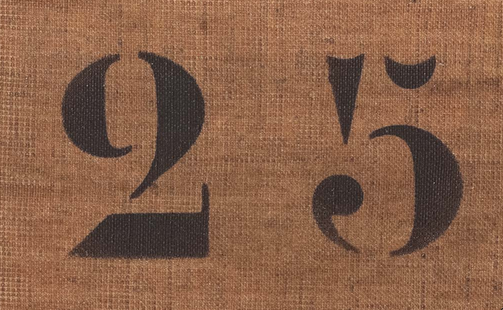

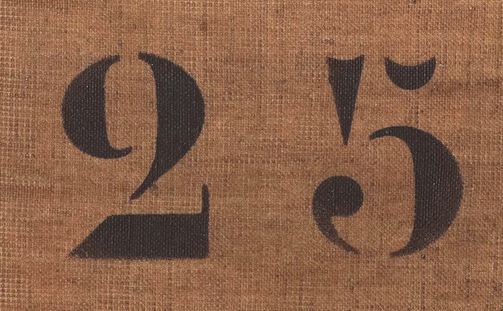

Standard format

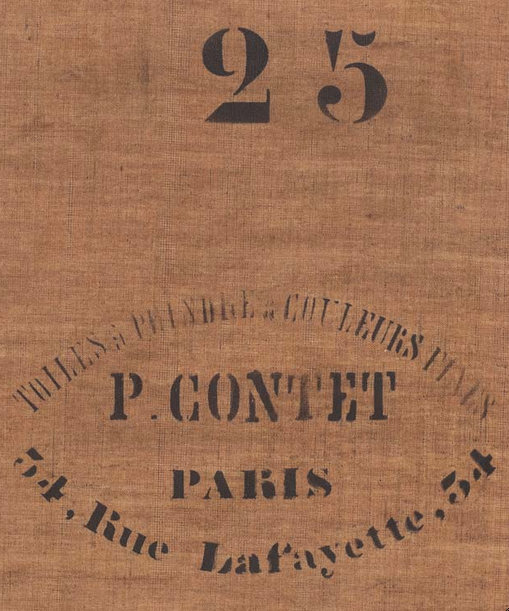

The original size of the canvas was very close to its current size, 65 × 80.9 cm. This corresponds to a no. 25 portrait (figure) standard-size (81 × 65 cm) canvas turned horizontally; this is also the standard size stamped on the verso of the canvas (fig. 12.18).

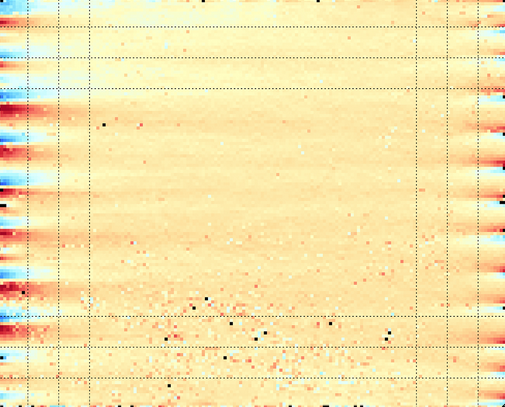

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 34.3V (0.8) × 33.5 H (1.0) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft.

Canvas characteristics

The canvas is of a very fine weave with scalloping corresponding to the placement of the original tacks. Strong primary scalloping along the left side, seen in the thread-angle map, may relate to commercial preparation (fig. 12.19). Close examination of the left edge also reveals that at least some of this edge was originally unprimed; this may be the margin of unprimed canvas along the edge of a larger section in commercial preparation (fig. 12.20).

Stretching

Current stretching: The work was locally restretched at the top, corners, and sections of the right and left sides during a 2006 local edge-lining treatment; although some tacks were added to create more even tension, previous tacks and tackholes were used wherever possible. Elsewhere, the painting seems to have retained its original stretching (fig. 12.21), with hand-wrought tacks placed approximately 3.5–6.5 cm apart and corresponding with cusping seen in the X-ray.

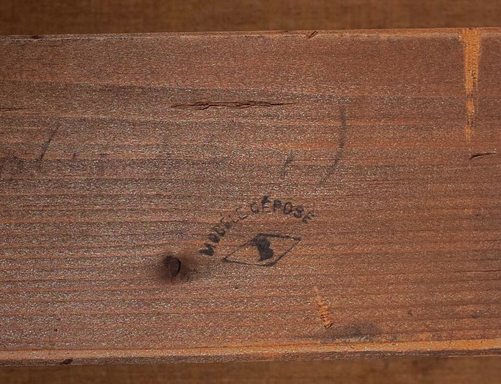

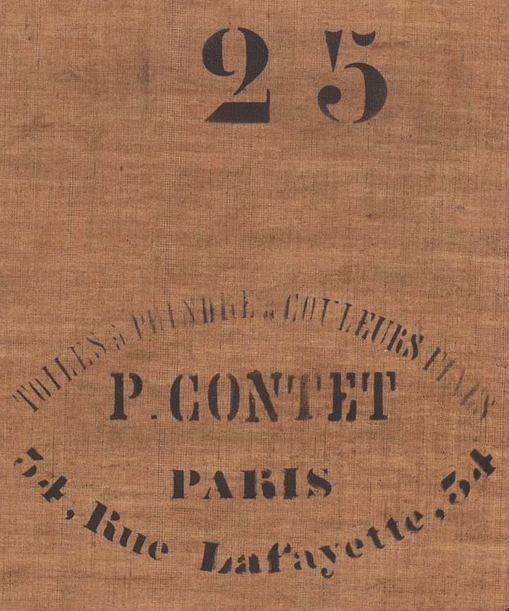

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: The painting appears to have retained its original stretcher (fig. 12.22). The work has a five-member, keyable, mortise-and-tenon stretcher with a vertical crossbar, or a chassis à clés. The modèle déposé B stamp on the crossbar is the registered trademark of Bourgeois Aîné (fig. 12.23). Depth: 1.9 cm.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Number

Location: canvas verso

Method: black stencil/stamp

Content: 25 (fig. 12.24)

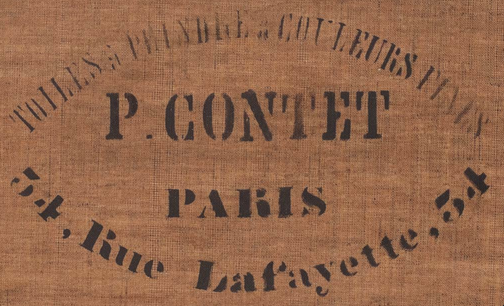

Stamp

Location: canvas verso

Method: black stencil/stamp

Content: TOILES á PEINDRE á COULEURS FINES / P. CONTET / PARIS / 34 , Rue Lafayette , 34 (fig. 12.25)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black stamp

Content: MODÈLE DÉPOSÉ / <B> (fig. 12.26)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

The ground appears to be a relatively thin, smooth, single-layer commercial preparation that somewhat fills the fine canvas weave.A small unprimed margin along the edge of the lower third of the left tacking margin may indicate that this canvas was along the edge of a larger pre-primed section in commercial preparation (fig. 12.27). The edges of this preparatory layer suggest the priming was applied with a brush. The ground is left visible in skips and lacunae throughout the work.

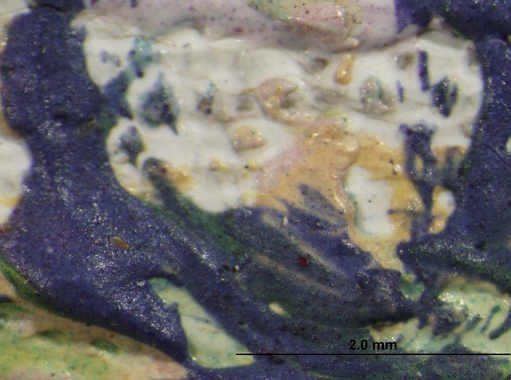

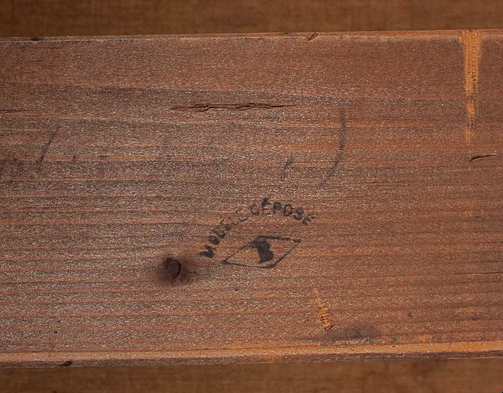

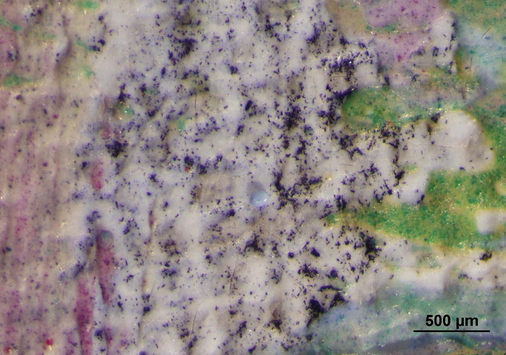

Color

The ground appears almost white, with some dark particles visible under stereomicroscopic examination (fig. 12.28). These particles may be on the surface, as visual examination of a cross section of the ground and canvas did not reveal any colored particles in the layer.

Materials/composition

XRF analysis suggests that the ground is composed of predominantly lead white with iron oxides, calcium compounds such as calcium carbonate and/or calcium sulfate, and barium sulfate. The binder is estimated to be oil.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

Stereomicroscopic examination suggests that the artist sketched the basic forms of the trees, including the thinnest ones, and some of the basic delineations of the landscape before painting (fig. 12.29). The figures, however, including the large foreground figure, are executed directly over the thickly painted background without evidence of underdrawing. Due to the thinness of the underdrawing and the thickness of subsequent paint layers, the full extent of the underdrawing is not entirely clear.

Medium/technique

The underdrawing is executed in a combination of black chalk or charcoal and very thin, fluid blue paint (fig. 12.30). It is unclear if the artist first executed a light sketch in dry media and applied the paint over it in an attempt to set it before painting, or whether the underdrawing media was a mixture of chalk or charcoal particles in thin blue paint. The underdrawing varies in thickness from semitranslucent to almost transparent (fig. 12.31).

Revisions

The artist appears to have generally followed his underdrawing without adhering to the lines exactly (fig. 12.32). No changes were noted in the planning/drawing stage (see Paint Layer).

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revision

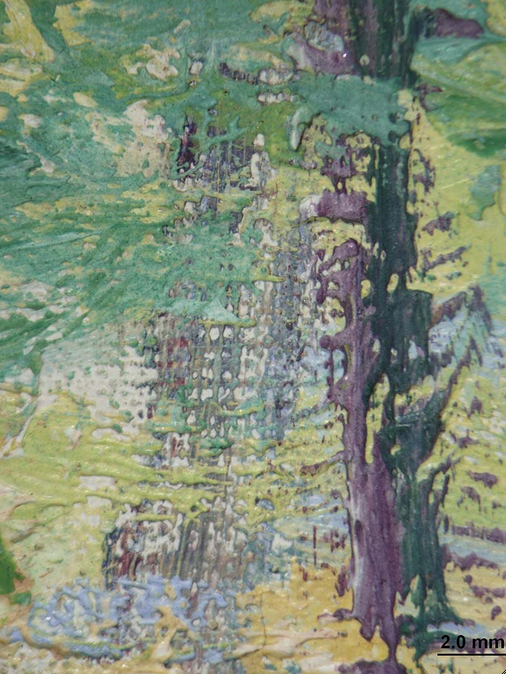

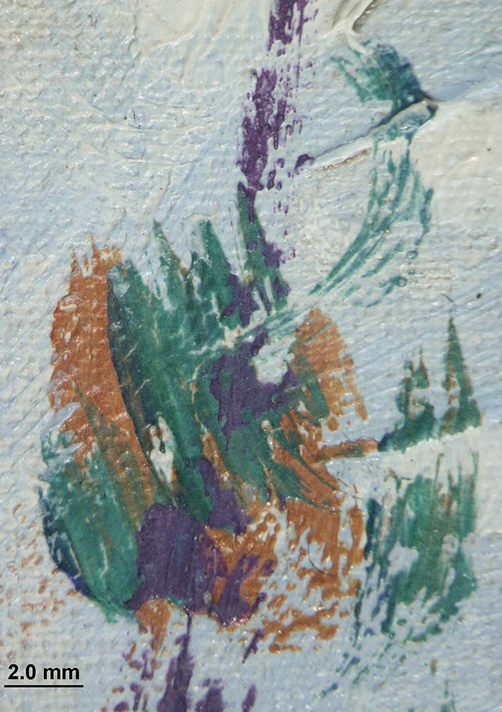

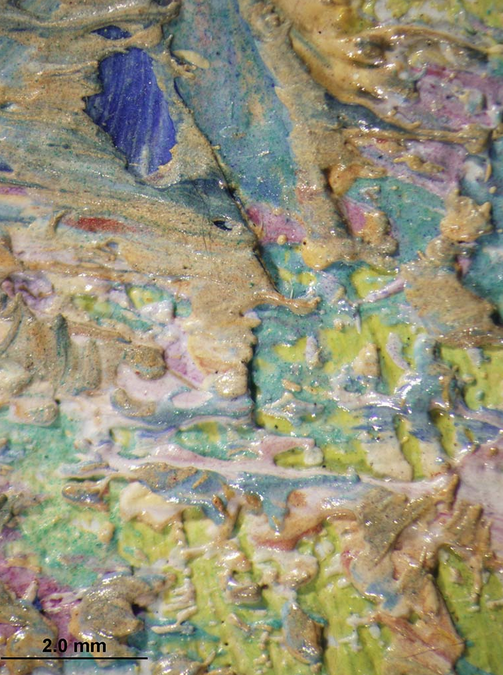

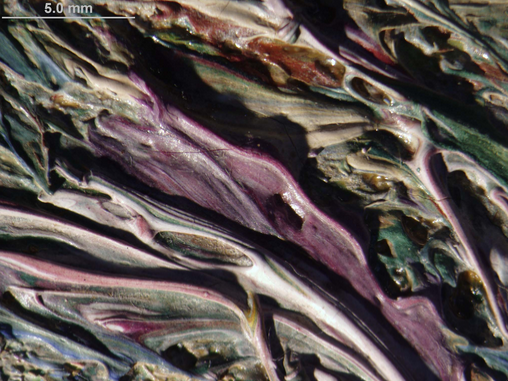

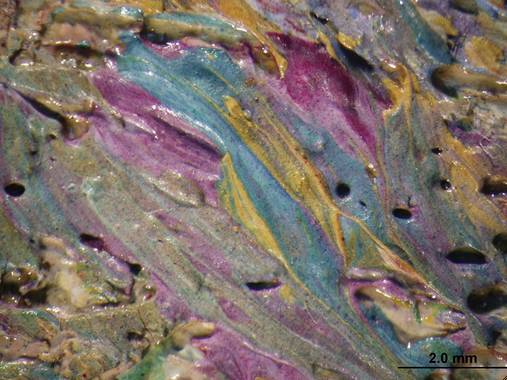

The composition and technique of the painting indicate the work was completed in stages: the first concentrated on the general landscape elements, and the second focused on adding the figures and building up heavily textured hay in the foreground. After executing a faint underdrawing to denote the trees and the striations of the landscape, Pissarro started laying in flat planes of color. Beginning with the trees he loosely followed the underdrawing, sometimes slimming and altering the curves of the tree trunks as he painted. These are predominantly underpainted in numerous shades of pale pink and purple, with great modulation in tone throughout and many colors mixed directly on the canvas rather than on the palette. The tree at the far right in the foreground, for example, is underpainted in a very pale cool pink (fig. 12.33), while the large tree at the left has visible underpainting throughout the branches and foliage in bright pinkish-purple (fig. 12.34). In some cases, evidence of the artist’s compositional changes is more visible due to the underpainting rather than the underdrawing, as in the thin tree second from the right. Here, Pissarro first executed the trunk with a small, flat brush carrying as many as three different colors at once, including deep blue, red lake, and white (fig. 12.35). The first indication of this tree, in which the bottom bows to the left rather than straight down, is still visible with careful examination of the surface under normal viewing conditions, and is more clear in the infrared images. At the far right the presence of light pink visible under the green grass, in addition to a faint form visible in the X-ray, suggests the trunk of this tree may have been further to the right, curving in from the right edge (fig. 12.36). Other forms, such as a low-hanging branch on the far right tree (visible in the X-ray), seem less resolved and appear to have been abandoned relatively early in the painting process. In the transmitted-light and X-ray images an outcropping of leaves can be seen jutting out from the group of trees at the right; this cluster of leaves and extended branches likely corresponded to the thinner tree slightly to the left and in front of the wider tree. With this asymmetric leafy outcropping this tree would have somewhat mirrored the foreground tree at the left. Smaller alterations to the trees, such as slimming or slightly straightening the trunks and moving the branches, as Pissarro did with the right fork of the second tree from the left (visible in the infrared image), may have been made slightly later in the painting process. In most cases the artist covered these changes heavily with subsequent layers, and only hints of these earlier compositional ideas are still visible on the surface (fig. 12.30).

After the trees were initially established Pissarro brought in the yellows and greens of the striated landscape, underpainted the foliage between the trees and the architectural elements at the center of the composition in muted, earthy yellows and pale greens, and laid in the sky in shades of pale blue. In the next painting stage he included more textured strokes and a wider variety of colors. Where the trees extend into the sky, the artist moved back and forth between the foliage and the background, covering some of the previously underpainted branches and leaves with the directional strokes for the clouds and sky; he then executed the finer and more specific details of the trees on top and in between the directional strokes in the sky (fig. 12.37). The result is that the taller, darker trees on either side of the foreground each have discrete, discernible branches and a distinct, individual shape compared to the more generalized, round-topped trees behind them.

After working up the sky and basic landscape elements Pissarro appears to have halted the painting and allowed the work to dry. The X-ray indicates that all four figures, including the large female figure at the right, were executed on top of the dry landscape (fig. 12.38). The large figure also shows no evidence of underdrawing, and her features appear rather generalized; evidence of the light greens and yellows of the underlying grasses from the landscape can be seen in lacunae throughout her clothing (fig. 12.39). Close examination of the foreground indicates the bright grasses extended all the way to the bottom edge of the picture, and the heavily textured mounds of hay were added later (fig. 12.40 and fig. 12.41). The hay itself was executed with paint of a paste-like consistency and fine, soft brushes that impart very little of their texture to the paint but rather dragged the paint across the surface, creating ribbons of heavily textured, wet-in-wet impasto (fig. 12.42 and fig. 12.43). The artist’s technique in the foreground manifests an intimate awareness of his medium; Pissarro knew the precise consistency of paint, the size and softness of the brush, and how often to rinse it to achieve particular results, and he combined this knowledge with sure-handed, directional movements to achieve these ribbon-like effects and an exact degree of wet-in-wet blending of colors on the picture surface (fig. 12.44).

Painting tools

Predominantly small, round and flat brushes of varying softness, with strokes up to 0.4 cm.

Palette

Analysis suggests the presence of the following pigments: lead white, zinc white, vermilion, madder lake, iron-oxide red and/or yellow, chrome yellow, cobalt blue, cobalt violet, emerald green, and possibly viridian.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The work is currently unvarnished, with some residues of older natural-resin varnish in areas of heavy impasto. A natural-resin varnish was removed in 2006; a verso image from 1984 shows evidence of prior cleaning or a varnish application after the work had aged and cracked, suggesting this varnish was not original.

Conservation History

The painting was treated in 2006 when a thick natural resin varnish was removed. Tearing at all four corners was mended with local bandages of fine-weave polyester fabric and Beva 371 film. Along the right edge and the left half of the top edge, as well as two spots along the left side, tacks had rusted and pulled through the canvas, causing the canvas to pull away from the stretcher; these areas were locally edge-lined like the corners. A padded insert backing was added to help support the unlined canvas. The work required little retouching and was left unvarnished.

Condition Summary

The work is adequately tensioned on its stretcher, with some minor buckling along the top and dips at the upper corners, seen in the raking light image. Aside from local edge-lining, the painting maintains its original stretcher and stretching. The canvas itself is in good condition, still largely flexible with few damages; small, somewhat evenly placed punctures along the edges just inside the foldover appear as small nail or tack holes and may be evidence that a strip frame was once attached to the front of the painting; flattened paint along the edges near these holes suggests contact with a frame or similar structure while the paint was still soft. The foldover edges, except at left, remain largely uncracked, and the corner and local edge-linings applied during the 2006 treatment appear stable. The tacking margins, aside from large holes sustained from tacks pulling through, also exhibit a number of smaller holes similar to those seen on the front, but more closely placed; these may also relate to former framing elements. There are multiple layers of paper tape intermittently along the edges, and the verso shows signs of previous cleaning or wiping before the 2006 treatment.

The ground and paint layers are in good condition with few losses or accretions. Aside from losses relating to support loss at the corners and the punctures along the edges, there are a few losses in the sky, a small vertical loss near the left edge by the lower tree branches, a small loss of upper paint layers in the hem of the skirt on the woman at the right, and a similar loss on the tree trunk at the left. There is fine age and microcracking in many of the thickly painted areas, most of which cannot be seen easily with the naked eye and appear to be stable. The painting is unvarnished, with some residues of natural-resin varnish in areas of high impasto.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame is not original to the painting. It is an American, 1960/70 reproduction of a Louis XVI fluted scotia frame with acanthus leaves at the miters and lamb’s-tongue sight molding with an independent fillet and cove liner. The frame has water and oil gilding over red bole on sprayed gesso. The rails are burnished, as are portions of the lamb’s-tongue ornament, and the gilding has been heavily rubbed and toned. The carved basswood moldings are mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is astragal chaplet with bead-and-barrel ornament; scotia side; fillet; fillet rail; fillet; scotia, fluted with acanthus leaves at the miters; flat frieze; ogee with lamb’s-tongue ornament; and an independent fillet and cove liner (fig. 12.45).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Dec. 3, 1892.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Jan. 15, 1894.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Mrs. John Jay (Harriet Blair) Borland, Chicago, Oct. 19, 1899.

By descent from Mrs. John Jay (Harriet Blair) Borland (died 1933), Chicago, to her son, Bruce Borland, Chicago.

Given by Bruce Borland, Chicago, to the Art Institute, beginning in 1961.

Exhibition History

Paris, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Exposition d’oeuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro, Mar. 15–30, 1893, cat. 38, as Fenaison à Eragny, 1892.

New York, Durand-Ruel Galleries, Paintings by Camille Pissarro, Views of Rouen, Mar.–Apr., 1897, cat. 33, as Fenaison à Eragny, 1892.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of Chicago Collectors, Apr. 15–May 7, 1961, no cat. no.

Tokyo, Isetan Museum of Art, Retrospective Camille Pissarro, Mar. 9–Apr. 9, 1984, cat. 43 (ill.); Fukuoka Art Museum, Apr. 25–May 20, 1984; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, May 26–July 1, 1984.

Art Institute of Chicago, Art Inside Out: Exploring Art and Culture through Time, Sept. 19, 1992–June 16, 1996, no cat (fig. 12.46).

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Claude Monet: Effet de soleil—Felder im Frühling, May 20–Sept. 24, 2006, cat. 44 (ill.).

Selected References

Galeries Durand-Ruel, Exposition d’oeuvres récentes de Camille Pissarro, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, 1893), cat. 38.

Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York, Paintings by Camille Pissarro: Views of Rouen, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, 1897), cat. 33.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son art—son oeuvre, vol. 1, Texte (P. Rosenberg, 1939), p. 192, no. 789.

Ludovic Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pissarro: Son art—son oeuvre, vol. 2, Planche (P. Rosenberg, 1939), pl. 162, no. 789 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of Chicago Collectors, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), n.p.

Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro: His Life and Work (Horizon, 1980), p. 299.

Isetan Museum of Art, Fukuoka Art Museum, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Retrospective Camille Pissarro, international ed., exh. cat. (Art Life, 1984), pp. 67, cat. 43 (ill.); 135.

Ralph E. Shikes, “Pissarro’s Political Philosophy and His Art,” in Christopher Lloyd, ed., Studies on Camille Pissarro (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 50.

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 111, 114 (ill.), 118.

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, vol. 3, 1891–1894 (Valhermeil, 1988), p. 270, letter 828.

Charles Harrison, “Art & Language Paints a Landscape,” Critical Inquiry 21, 3 (Spring 1995), pp. 632, fig. 21; 634.

Alan G. Artner, “Provenance: The ‘Secret Life’ of Art,” Chicago Tribune, Apr. 23, 2000, p. 7.1 (ill.).

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, with the collaboration of Alexia de Buffévent and Annie Champié, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings, vol. 1, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Skira/Wildenstein Institute, 2005), pp. 363, 364, 394, 408.

Joachim Pissarro and Claire Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, with the collaboration of Alexia de Buffévent and Annie Champié, Pissarro: Catalogue critique des peintures/Critical Catalogue of Paintings, vol. 3, trans. Mark Hutchinson and Michael Taylor (Skira/Wildenstein Institute, 2005), p. 623, cat. 951 (ill.).

Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad, with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Effet de soleil–Felder im Frühling, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz), p. 158. Translated as Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Fields in Spring, trans. John S. Southard, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz, 2006), p. 158.

Christofer Conrad, “Von der Impression zur Ordnung des Bildes,” in Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad, with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Effet de soleil–Felder im Frühling, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz), pp. 94–95, fig. 65 (cat. 44). Translated as Christofer Conrad, “From Impression to Organization of the Picture,” in Christian von Holst and Christofer Conrad, with contributions by Roman Zieglgänsberger and Katja Matauschek, Claude Monet: Fields in Spring, trans. John S. Southard, exh. cat. (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart/Hatje Cantz, 2006), pp. 94–95, fig. 65 (cat. 44).

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory Number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 2509

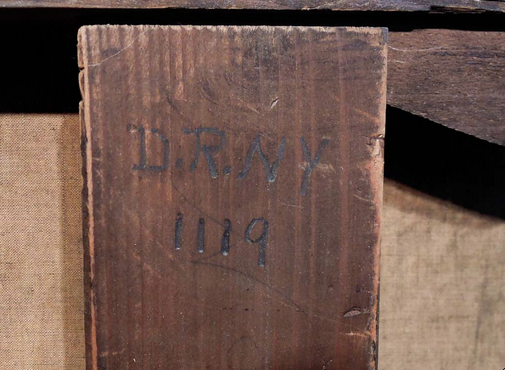

Inventory Number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 1119

Photograph

Photo Durand-Ruel 432

Other Documents

Inscription (fig. 12.47)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

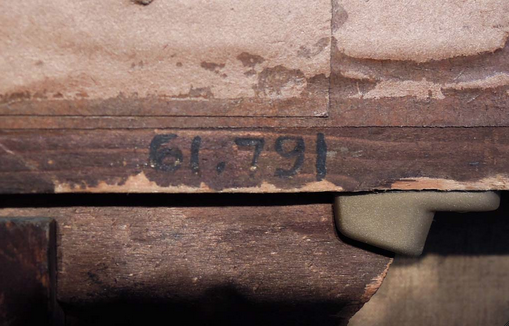

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (black)

Content: 61.791 (fig. 12.48)

Pre-1980

Number

Location: canvas verso

Method: black stencil/stamp

Content: 25 (fig. 12.49)

Stamp

Location: canvas verso

Method: black stencil/stamp

Content: TOILES á PEINDRE á COULEURS FINES / P. CONTET / PARIS / 34 , Rue Lafayette , 34 (fig. 12.50)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black stamp

Content: MODÈLE DÉPOSÉ / <B> (fig. 12.51)

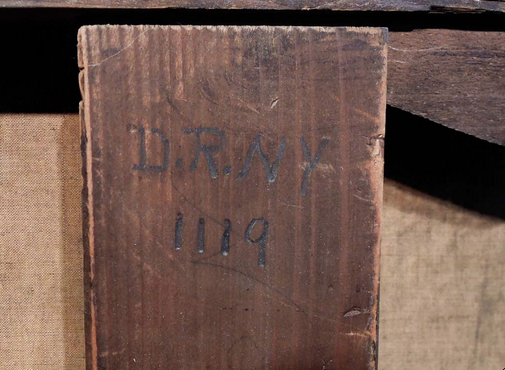

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: D.R.NY / 1119 (fig. 12.52)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (black) and blue stamp on printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / PISSARRO, Camille / Haying Time / 1892 / Gift of Bruce Borland / [stamp at right] Inventory – 1980 – 1981 / [handwriting at right] 1961.791 (fig. 12.53)

Post-1980

Label

Location: backing board

Method: handwritten script (graphite) on printed label

Content: PANEL INSERT / installation date / 5/3/06 (fig. 12.54)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: handwritten script (graphite) on printed label

Content: PANEL INSERT / installation date / 5/3/06 (fig. 12.55)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Camille Pissarro / title Haying Time, 1892 / medium oil on canvas / credit Gift of Bruce Borland / acc. # 1961.791 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 12.56)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, and Radboud University, Nijmegen, Neth.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/ Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm), J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Normal-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (B+W UV 010 MRC F-Pro filter and PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using Zeiss Axioplan2 Research Microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. (Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast [DIC], and UV.) In situ photomicrographs with Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom Microscope fitted with Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with Oxford EDS and Hitachi solid-state BSE. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility, Evanston, Ill.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Raman Spectroscopy

A Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope was used, equipped with an Andor multichannel, Peltier-cooled, open-electrode charge-coupled device detector (Andor DV420-OE322; 1024×256), an Olympus BXFM open microscope frame, a holographic notch filter, and an 1,800-grooves/mm dispersive grating. The excitation line of an air-cooled, frequency-doubled, He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) was focused through a 20× objective onto the samples, and Raman scattering was back-collected through the same microscope objective. Power at the samples was kept very low (never exceeding a few mW) by a series of neutral density filters in order to avoid any thermal damage.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the George Washington University, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

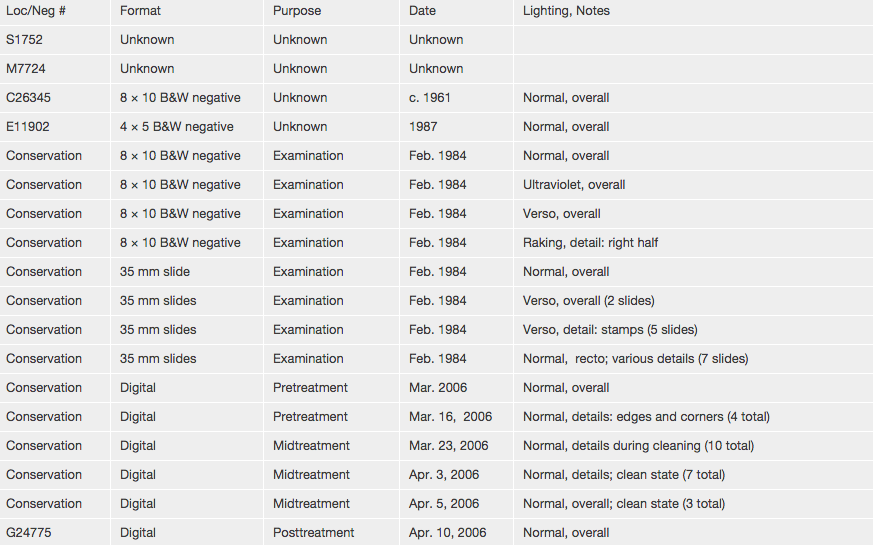

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 12.57).