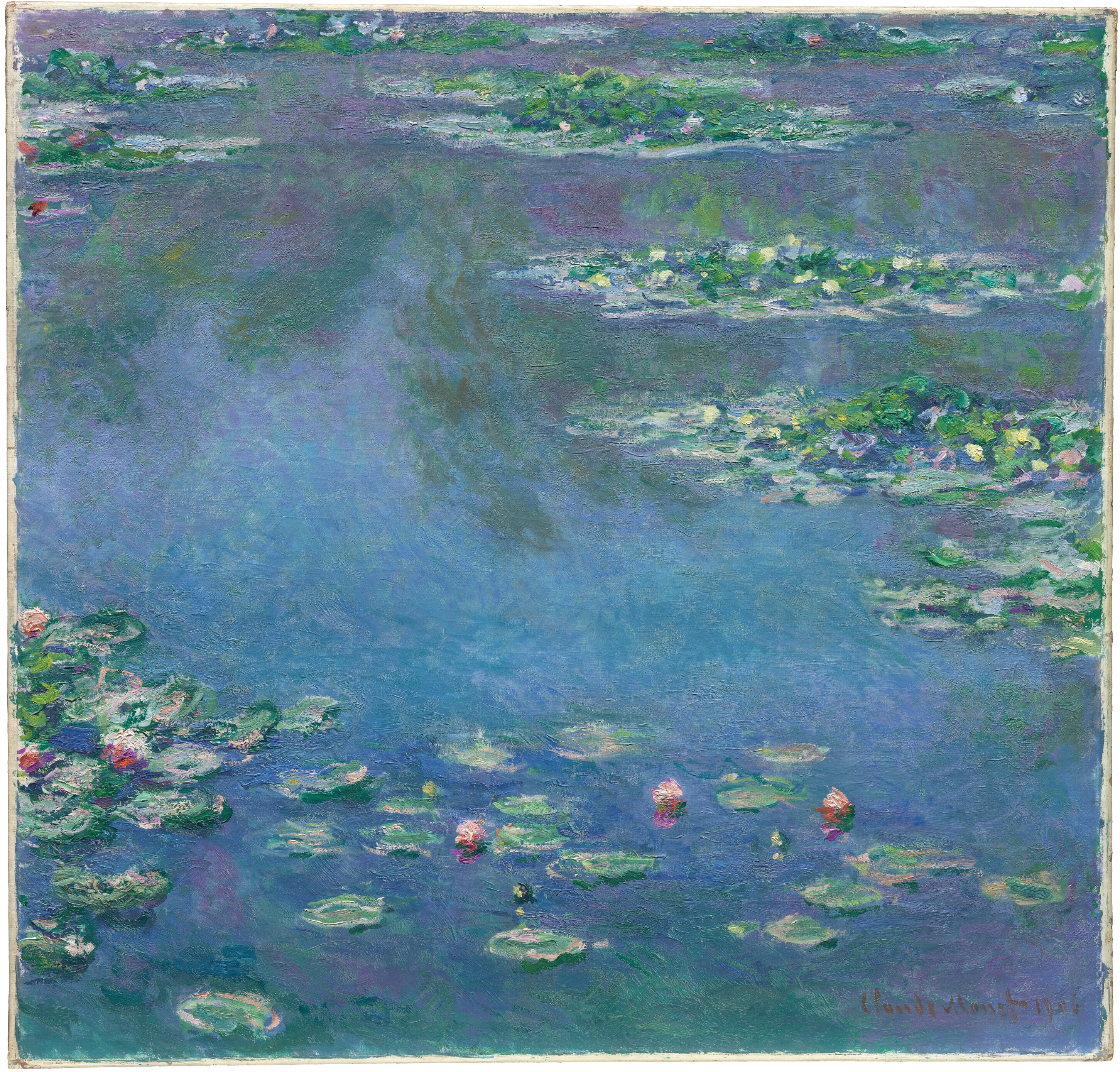

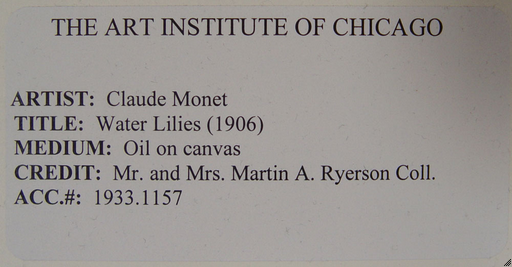

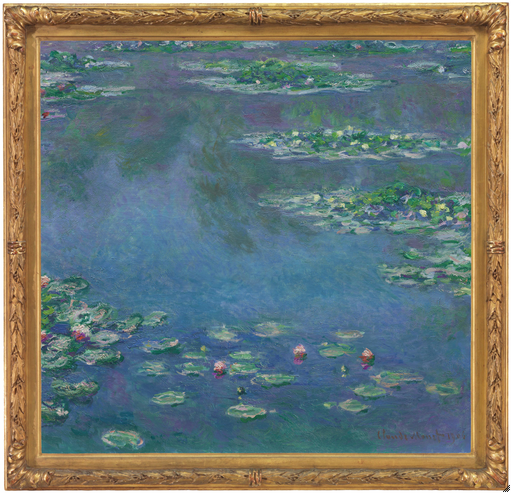

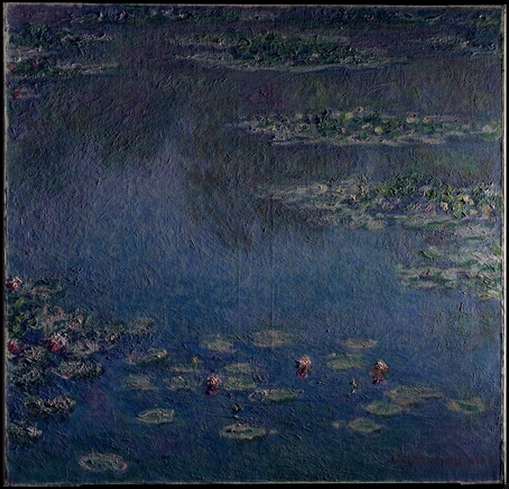

Cat. 44

Water Lilies

1906

Oil on canvas; 89.9 × 94.1 cm (35 3/8 × 37 1/16 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1906 (lower right, in reddish-brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1157

Water Lilies: An Obsession

In August 1908—less than one year before Claude Monet exhibited the Art Institute’s Water Lilies at the Durand-Ruel gallery in Paris along with almost fifty other paintings of the same motif—the artist was experiencing anxiety about the series. “Know that I am absorbed by my work,” he wrote to his friend the art critic Gustave Geffroy. “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession. It is beyond my powers as an old man, and yet I want to arrive at rendering what I feel. I have destroyed some . . . Some I recommence . . . and I hope that after so many efforts, something will come out.” These struggles had already forced Monet to twice postpone exhibiting this series of works. But after a trip to Venice in late 1908 (see cat. 45)—one that allowed him to look at his paintings of water lilies with “a clearer eye”—Monet was finally ready to pronounce them finished.

The exhibition, which eventually opened on May 6, 1909, and was scheduled to run until June 5, proved to be a great success, so much so that Durand-Ruel wanted to send the show on to London and Berlin; although Monet would not agree to this, the Paris show was extended by a week. Monet called the group of paintings on view Les nymphéas, series de paysages d’eau (Water Lilies: Series of Water Landscapes). The series, begun in 1903 following a significant renovation of the water garden at his Giverny home, affirmed Monet’s commitment to innovation and his desire to challenge the conventional definition of landscape painting.

Water Lilies Transformed

The Water Lilies series that Monet undertook between 1903 and 1908 was not his first engagement with the subject. Nonetheless, they were radically different from his previous depictions of the motif (see Water Lily Pond, cat. 37 [W1628], fig. 44.1). In his earlier treatment of the subject, Monet retained the traditional components of a landscape painting, representing the horizontal zones of water and land, and provided glimpses of the sky above. In each of these works, he grounded the viewer by including the Japanese bridge he had built on the property over the pond, as well as the plantings around its bank.

From 1903 onward, however, Monet’s treatment of the motif was much more experimental. Shifting viewpoints, the artist played with the relative proportion of water, land, and sky that remained visible, and in the majority of the works, he altogether eliminated the sky in the upper reaches of the canvas, leaving it discernible only as a reflection in the water (fig. 44.2 [W1656]). As Monet continued with these works, he became increasingly preoccupied with the reflection of the sky in the water, but he retained geographically specific elements that help orient the viewer. For example, in Le bassin des nympheas, at the Denver Art Museum (fig. 44.3 [W1666]), Monet included a sliver of the bank at the top of the canvas. The work in the Dayton Art Institute (fig. 44.4 [W1657]), however, shows no indication of a horizon line; it is Monet’s addition of foliage hanging from overhead that helps to position the viewer on a bank near which the tree or stalk must be rooted.

But over the course of creating his water lily pond paintings in the period 1903–08, Monet included fewer and fewer elements of (nonreflected) reality aside from the water itself. In the Art Institute’s painting, the sky and foliage surrounding the pond are only visible as amorphous and barely decipherable reflected forms. Monet also used canvases that were unconventional for the depiction of landscapes. The close-to-square format used in Water Lilies was not unusual for the artist (he had also used it for the earlier Water Lily Pond [cat. 37]), but the division of the canvas into irregular sections—the water lilies are unconventionally concentrated in the upper right and lower left corners and are divided by a diagonal swath of water in between—creates an otherworldly quality that defies any expectation of axial orientation. Monet pushed this concept even further by making a number of decorative, circular canvases (fig. 44.5 [W1729]).

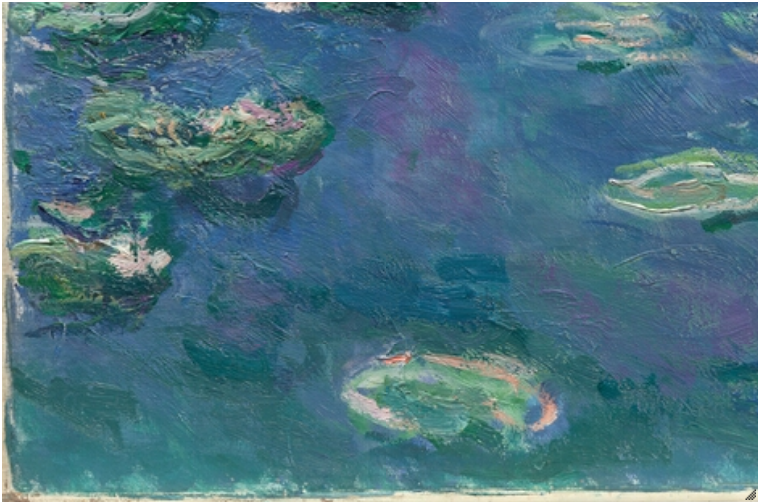

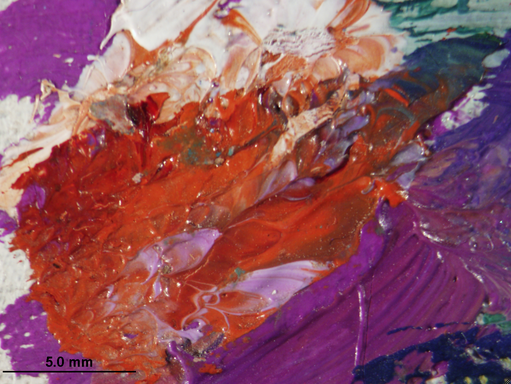

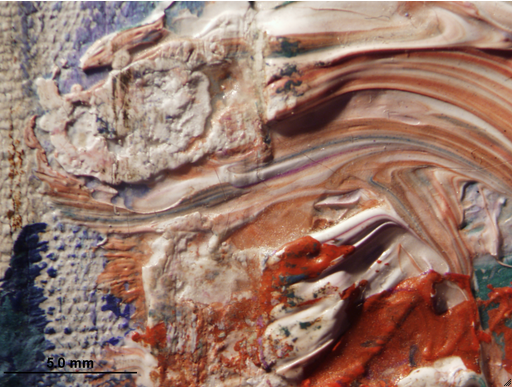

Creating Water Lilies

The incredible variation of Monet’s viewpoints and the airy quality he incorporated into his water landscapes from 1903–08 make them appear effortless. But, as noted above, this belies the fact that Monet struggled intensely with these paintings, something suggested by an account published in 1908 that claimed “all those who saw the pictures in February and March considered them ‘overworked,’ that is, they showed too plainly how long they had stood on the easel.” Indeed, technical examination reveals that Monet worked on Water Lilies over several sessions (see Technical Report). He built up the painting by superimposing layer upon layer of gestural brushwork on the canvas. In raking light, many of these underlying brushstrokes that do not correspond to forms in the final composition are quite evident (fig. 44.6). In the upper right corner of the canvas, it is also apparent that Monet applied at least eight or nine layers of paint in some areas, further revealing the extent of the artist’s complex painting process (fig. 44.7).

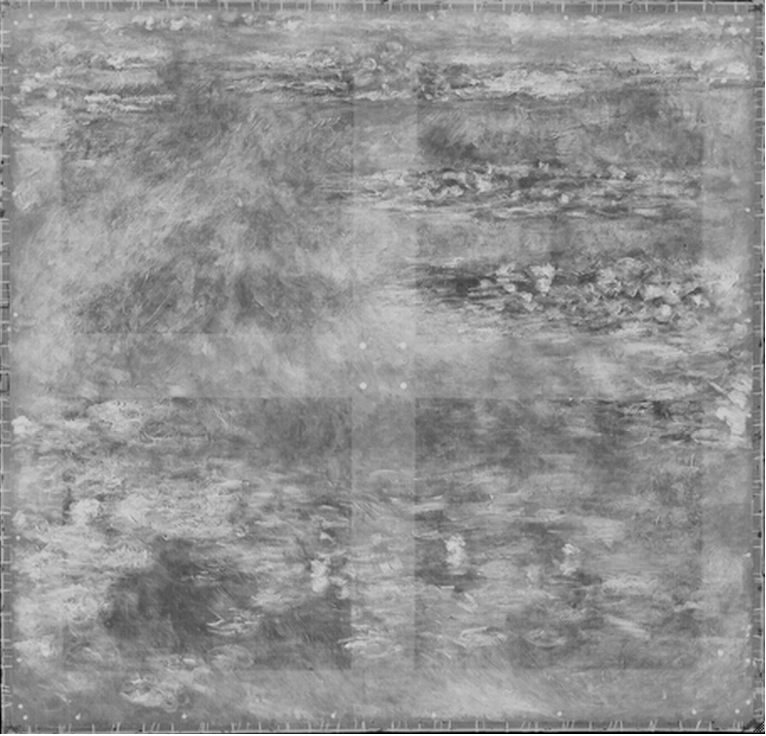

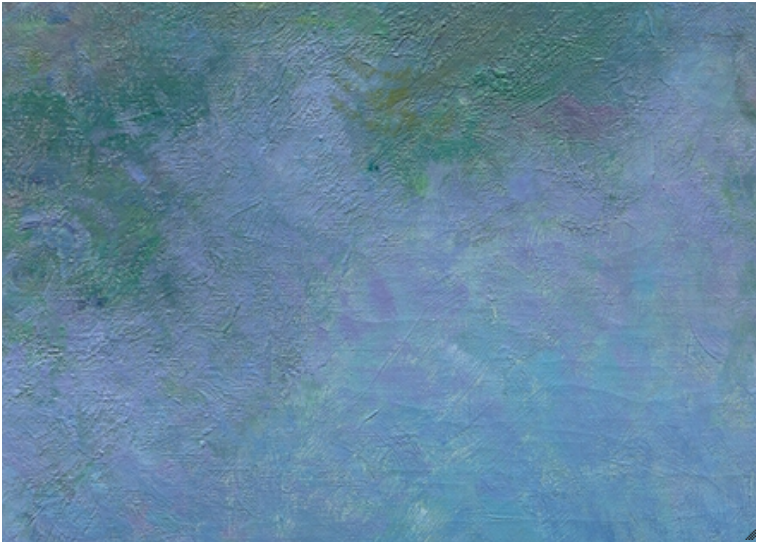

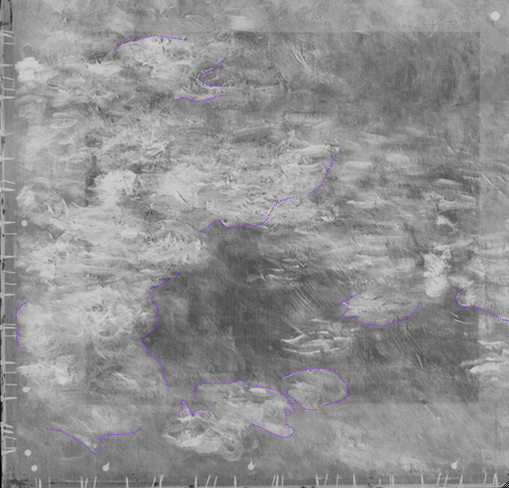

Monet’s changing technique and the tremendous effort he expended on the 1903–08 series of water lilies is particularly evident when compared to the Art Institute’s earlier Water Lily Pond (cat. 37). Although Water Lilies and other works from the 1903–08 group give the impression of being more fleeting and ephemeral than those he created in 1899–1900, transmitted-light images show the opposite to be true: in the earlier canvas, Monet left significantly more ground exposed (fig. 44.8). By exploiting the reflection of light off the ground layer, he suggested the transparency of water. In Water Lilies, however, only a very small portion of the ground layer has been left uncovered (fig. 44.9). The semblance of reflective light in the painting was a result of the paint that Monet had applied rather than ground left bare. A comparison of the palette used in these two paintings confirms this observation as well. While at first glance, the 1906 painting—in which the artist incorporated cool blues, purples, and greens over the entire canvas—appears more monochromatic and less flamboyantly colored than the 1900 painting, Monet actually used a similar range of pigments in both. In sum, the painting that appears more planned and even garish—Water Lily Pond, from 1900—was less worked; the one that seems more momentary—Water Lilies, from 1906—was far more labor intensive.

Instruments of Reflection

Despite differences in execution and composition, there is a constant in the Art Institute’s paintings of Monet’s water garden from 1900 and 1906: the water lilies, those organisms that symbolize the merging of the aquatic and terrestrial worlds. At times, Monet downplayed the importance of the flora in his water garden paintings, claiming that his true subjects were the light and the weather conditions. As he mentioned in a posthumously published interview: “The effect does change, constantly, not only from one season to another, but from one minute to the next as well, for the water flowers are far from being the whole spectacle; indeed, they are only its accompaniment. The basic element of the motif is the mirror of water, whose appearance changes at every instant because of the way bits of the sky are reflected in it, giving it life and movement.” Although the water lilies may have been, according to Monet, “just the accompaniment,” the art historian Paul Tucker has noted that in the Art Institute’s Water Lilies painting, they critically “perform their part by keeping the whole picture buoyant.” Indeed, they play the critical role of designating the transition between that which is above and below the water’s surface.

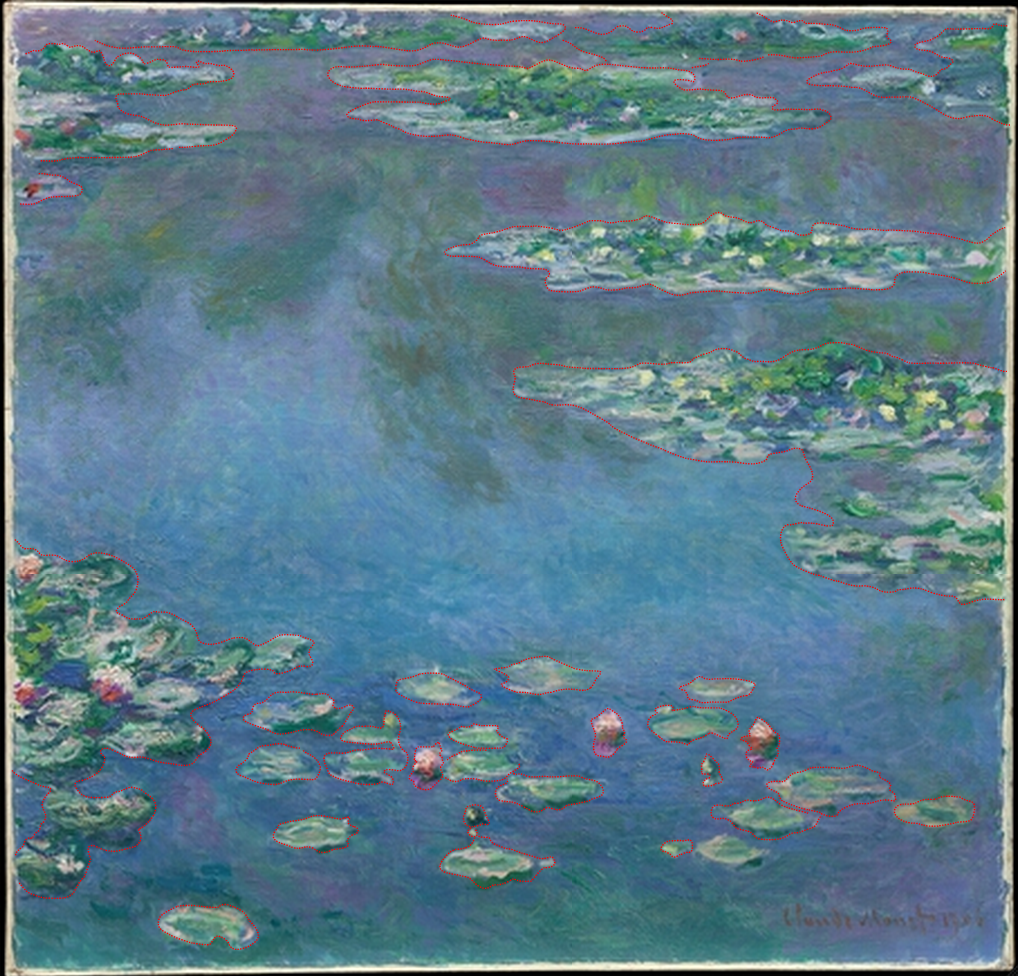

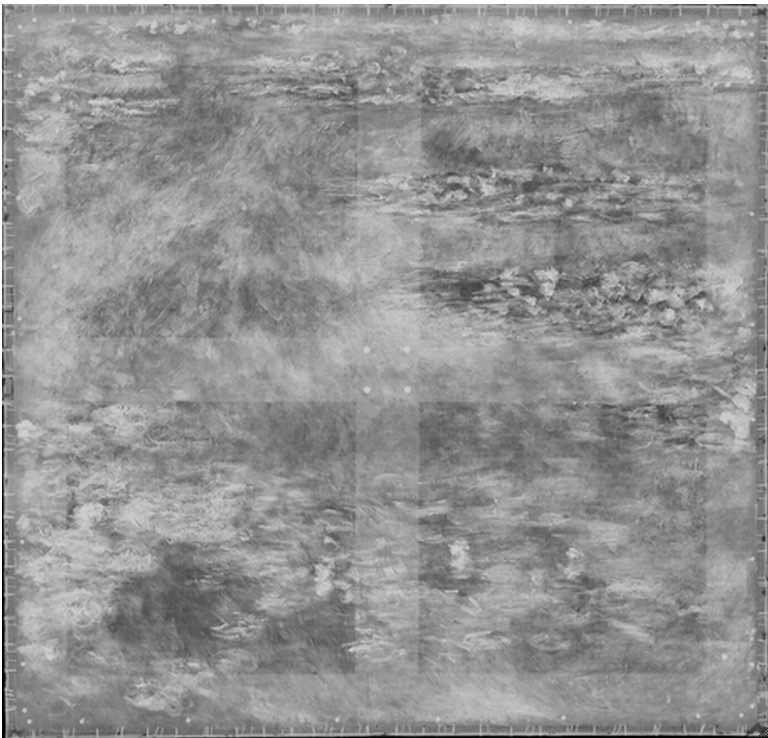

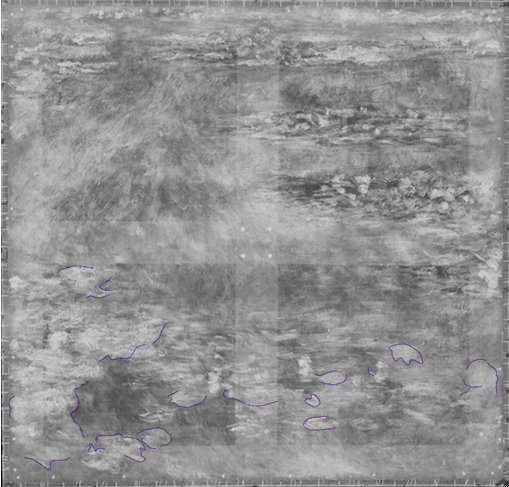

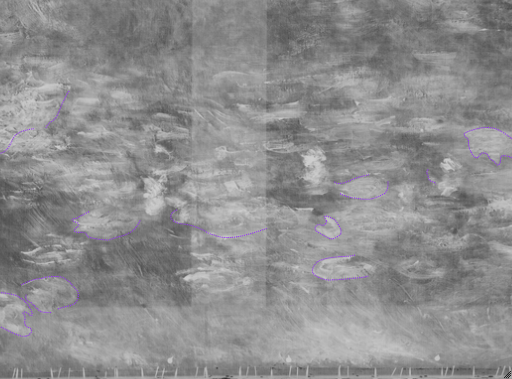

Despite Monet’s later recollection, Water Lilies demonstrates that the plants were crucial to the way in which he mapped out this canvas. As revealed by the X-ray of the painting, Monet planned a number of the water lily groupings very early on in the compositional process, sometimes directly over the ground layer (see Technical Report). There is also evidence that Monet built up the water around most of the plant groupings, indicating the fundamental role they played in the composition (fig. 44.10). In addition, the water lilies were details that Monet fussed over. In the Art Institute’s painting, there is evidence that Monet initially planned a denser grouping of the plants in the foreground, but that he went back and edited out some of them in order to achieve just the right balance (fig. 44.11).

A period photograph showing a hatted individual’s shadow looming over a water lily pond documents the stance that Monet must have taken when producing works like Water Lilies (fig. 44.12). For the art historian Victor Stoichita, who believes this figure to be Monet, this photograph was “the symbolic creation of an artistic confession.” By revealing only his shadow in the photograph, Monet was able to “express what was intrinsic to his final paintings: the shadow of the gaze, the instigator of painting.” Monet indeed left his autobiographical trace in the Chicago painting. Technical examination of Water Lilies reveals the extent to which Monet acted as the medium and interpreter of nature on this canvas. The touch of his flickering brush on the painting’s surface professes his everlasting artistic presence.

Jill Shaw

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Claude Monet’s Water Lilies was painted on a pre-primed, non-standard-size, linen canvas. The ground is off-white and consists of two layers. It has a distinct brush-marked surface, which is only visible at the unpainted edges, since the thick buildup of paint obscures the texture of the ground. The painting was carried out in several sessions, working from a rough lay-in of the main water lily groupings and a strongly brush-marked underpainting that was broadly applied throughout the water. The individual lily pads and flowers in the foreground of the composition were painted on top of the water. It appears that the artist originally planned a more dense coverage of water lilies in the foreground area, and then later painted out or partially covered several of the plants. The painting was densely built up in a network of thick, textural strokes and low impasto, with as many as nine distinct paint layers observed in one area.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 44.13).

Signature

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1906 (lower right, in reddish-brown paint) (fig. 44.14). The painting was dry when the signature and date were applied.

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions were approximately 89 × 92 cm. This does not correspond to a standard-size stretcher; both dimensions do, however, correspond to standard stretcher-bar lengths. The stretcher was probably custom ordered.

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 27.3V (0.5) × 27.4H (1.0) threads/cm; the vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft. No weave matches were found with other Monet paintings analyzed for this project.

Canvas characteristics

There is mild cusping along the top, bottom, and right sides of the canvas and pronounced cusping along the left edge. Cusping on the top, right, and bottom edges corresponds to the placement of the original tack holes. The strong cusping on the left side does not correspond to the original tack holes and extends beyond the cut edge of the canvas in places.

Stretching

Current stretching: Dates to 1990 conservation treatment (see Conservation History). Copper tacks spaced 3–4 cm apart.

Original stretching: Original tack holes spaced 4.5–6.5 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Dates to 1990 treatment (see Conservation History). It is a tongue-and-groove, keyable, wooden stretcher with six members including vertical and horizontal crossbars. Depth: 2.8 cm.

Original stretcher: Discarded. The pre-1974-treatment stretcher was probably the original stretcher. A 1974 photograph of the stretcher and an examination report in the conservation file record that the stretcher was a Buck type 2, consisting of six members, including a horizontal and a vertical crossbar, with keyable mortise and tenon joints. The report gives the following dimensions: height, 93 cm; width, 89 cm; stretcher-bar width, 6.5 cm; outside depth, 1.5 cm; inside depth, 2 cm; distance from canvas position, 0.5 cm; length of mortise, 6.5 cm (fig. 44.15).

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

None observed in current examination or documented in previous examinations.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

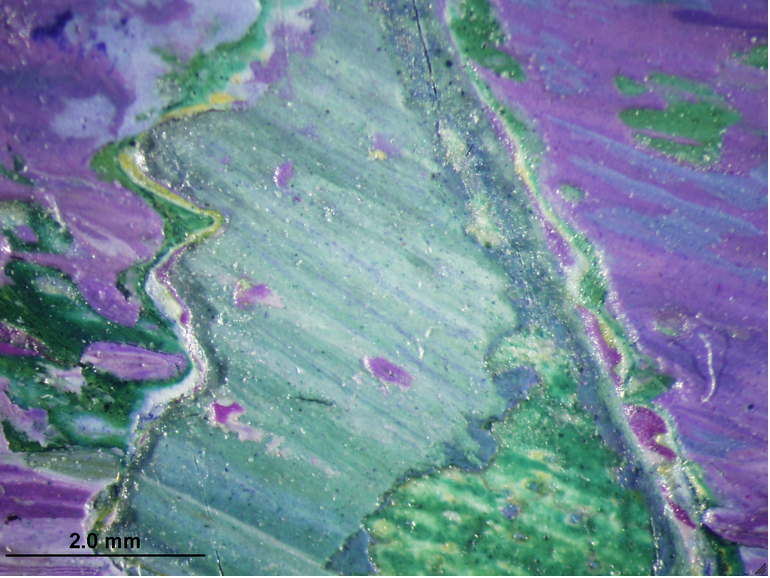

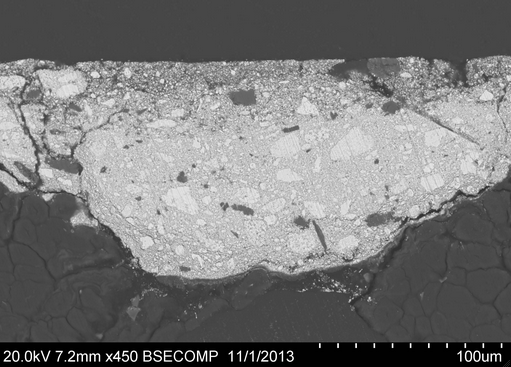

The ground layer extends to the edges of all four tacking margins, indicating that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed fabric, which was probably commercially prepared. The ground is relatively thick, filling up the canvas weave to some extent. Around the edges, where a border of unpainted ground from the tacking margins was incorporated into the picture plane when the lined painting was restretched onto a slightly larger stretcher (see Conservation History), the ground layer has a visibly brush-marked surface. The brush marking continues underneath the paint layer and to the cut edges of the tacking margins (fig. 44.16). Cross-sectional analysis indicates that the ground consists of two layers. The lower layer ranges from approximately 20 to 100 µm in thickness. The upper layer ranges from approximately 10 to 35 µm in thickness (fig. 44.17, fig. 44.18).

Color

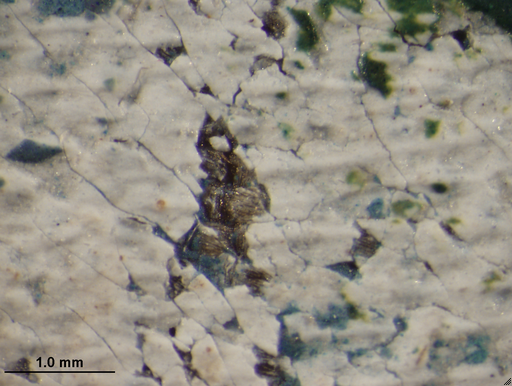

The ground is off-white, with some dark (possibly black and red or brown) particles visible under magnification (fig. 44.19).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the lower layer contains lead white with minor amounts of calcium sulfate and calcium carbonate (chalk), and traces of zinc white, various silicates, silica and alumina. The upper layer contains lead white with minor amounts of calcium sulfate, calcium carbonate (chalk), zinc white, and traces of iron oxide, silica, and various silicates. Binder: Oil (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing was observed with infrared reflectography (IRR) or microscopic examination.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

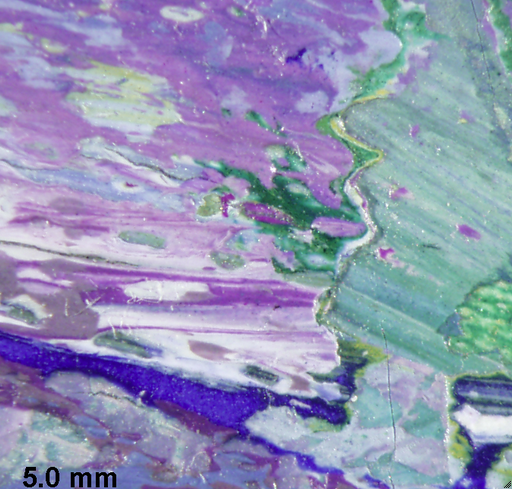

The painting was densely worked up using thick, opaque brushstrokes. The X-ray shows that the canvas was almost completely covered by a thick buildup of relatively radio opaque brushwork (fig. 44.20). As the transmitted-light image reveals, there are only a few translucent areas near the center of the painting where the light passes through the canvas (fig. 44.21). These are areas where the ground or thin underlayers of paint were left exposed through breaks in the brushwork. Over most of the surface, however, the buildup of brushwork obscures the initial layers of painting and much of the canvas and ground textures (fig. 44.22). A small damage near the upper right corner, which seems to have occurred early on, when the paint was still somewhat soft, provides a cross-sectional view of the paint layers in that area (fig. 44.23). At the edges of the loss, one can see a complex buildup of brushstrokes consisting of at least eight or nine layers of different colors including (from bottom up): green, blue, green, purple, yellow, white, green, purple, and blue.

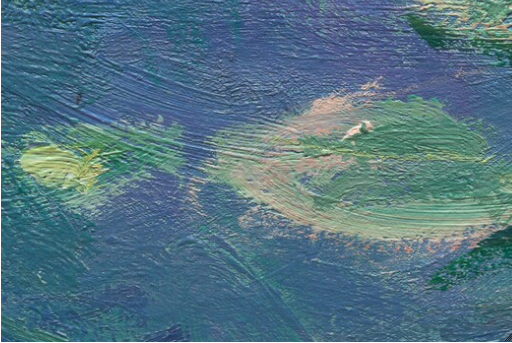

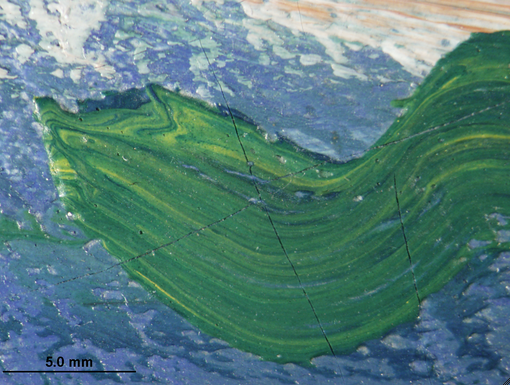

The thick buildup of paint makes it difficult to see how the composition was laid in, but throughout the work, where views are permitted, various shades of green paint are visible, lightly brushed directly over the ground layer. This can be seen in areas of open brushwork among the clusters of water lilies (fig. 44.24) and at the edges of the composition (fig. 44.25). In addition to these thinly applied strokes of paint, the artist also laid down some thicker, brush-marked strokes, which, despite being covered by subsequent paint layers, contribute much of the surface texture to the final painting. These strokes were broadly applied throughout the upper two-thirds of the composition (fig. 44.26, fig. 44.27). The texture of the underlying paint is often emphasized by subsequent strokes of relatively flat, solid color, which catch on and accentuate the ridges of the brushstrokes below. This is particularly evident in the areas of reflected foliage in the upper part of the water (fig. 44.28). The fact that the earlier brushstrokes were not disturbed by the later paint applications indicates that they were at least surface dry when the composition was built up.

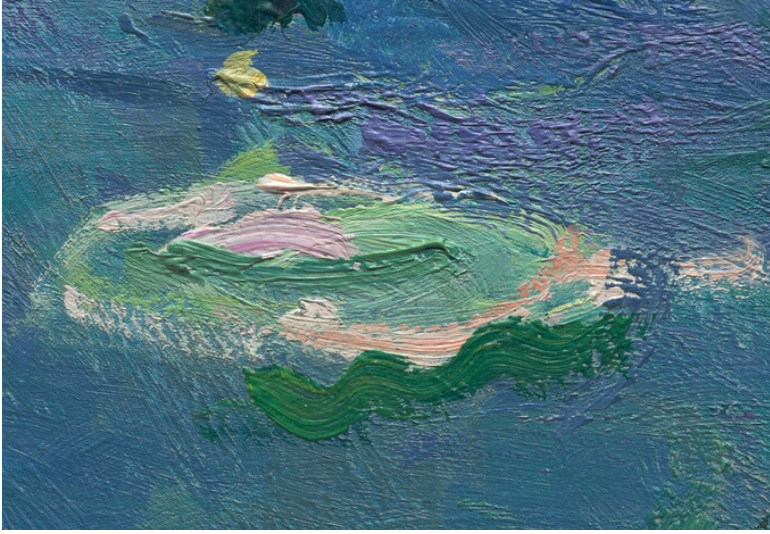

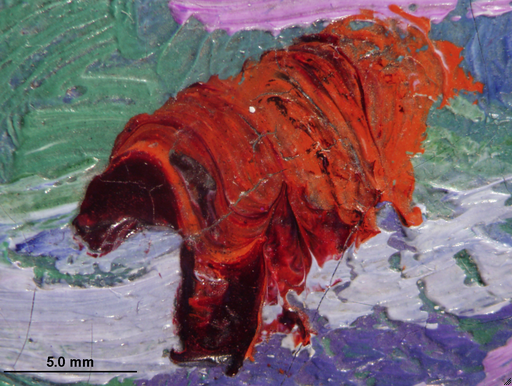

The groupings of water lilies in the upper part of the painting and down the right side were planned from early on. As mentioned above, these areas were painted directly over the ground layer or the thin underpainting, and in the X-ray, the paint buildup is less dense since the water was painted around the plants (fig. 44.29). The water lilies in the lower third of the painting were more haphazardly composed, with some parts built up directly over the ground or thin lay-in (fig. 44.30), and others applied on top of the thick, impasted brushwork of the water (fig. 44.31). It seems that Monet was experimenting with the degree to which the foreground surface of the water would be covered with water lilies, as some plants were later painted out of the composition while others were added in the final painting stages. The X-ray shows that this area of the composition was densely built up over a broader area, and although some of the brushwork could be related to the textural underpainting used throughout the work, distinct ovoid shapes suggest that more plants (i.e., individual water lily pads) were painted in at an earlier stage (fig. 44.32). The large grouping at the lower left edge, for example, was initially painted as a larger mass that extended further into the water at the upper right edge (fig. 44.33). Thick blue paint from the water was then applied on top to cover parts of the plants and create breaks in the grouping. Green paint from the painted-over foliage remains visible in a few places (fig. 44.34). Further to the right, where the water lilies are more dispersed, additional ovoid shapes visible in the X-ray suggest that a few more lily pads were initially painted in this area (fig. 44.35). These isolated water lilies all appear to have been painted on top of the thick, textural paint of the water after it was surface dry. Some of the plants were worked up in bright greens with some pink and red strokes, presumably related to the petals of the flowers (fig. 44.36). In one case, the lily pad was only partially painted out, such that the right edge was left exposed; the yellow flower was then added on top (fig. 44.37).

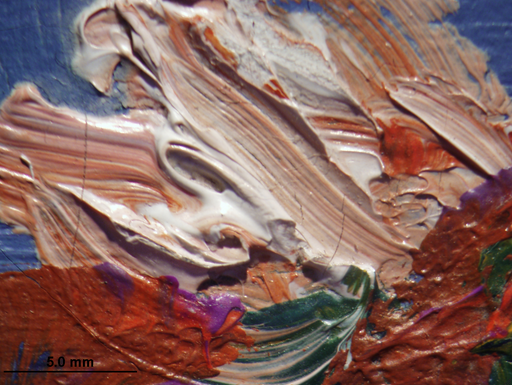

The water lilies were built up in multiple, superimposed strokes of thick paint applied using both wet-on-wet and wet-over-dry layering, which indicates that the painting was carried out in multiple sessions (fig. 44.38). Where brushstrokes were drawn through wet paint, there is no blending and each stroke retains its distinct form (fig. 44.39). The artist varied the consistency of his paints, using stiffer paint to create thick impasto (fig. 44.40) and soft peaks (fig. 44.41, fig. 44.42), and more fluid applications where colors have swirled together and settled to a smoother surface (fig. 44.43, fig. 44.44). For the flowers, the artist used touches of brilliant color (fig. 44.45) and sometimes picked up multiple unmixed colors on his brush (fig. 44.46, fig. 44.47). There are areas of flattened paint around the edges, suggesting that the work was framed when the paint was still soft. In one area on the left edge, a thick stroke of impasto was squashed when the paint was still wet (fig. 44.48).

Painting tools

Brushes, including 1.0 and 1.5 cm width, flat ferrule (based on width and shape of brushstrokes). Several coarse brush hairs are embedded in the paint layer.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cadmium yellow, chrome yellow, vermilion, red lake, viridian, malachite, cobalt blue, ultramarine blue, and cobalt violet.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

In 1990, the synthetic varnish layers applied in 1974 were removed; traces of residual varnish were retained in places, however, and a thin retouching varnish was rubbed in locally where blanching had occurred (see Conservation History). Overall, the paint surface has a soft sheen with subtle variations from low gloss to matte depending on the qualities of the paint.

Conservation History

In 1956, the painting was described as unvarnished and a surface coating was recommended. The pre-1974-treatment-notes mention the presence of a thin, natural-resin varnish, which suggests that varnish was applied some time between 1956 and 1974; the 1974 treatment report mentions only grime removal, however, creating some uncertainty as to the presence of a varnish layer prior to 1974.

In 1974, surface grime was removed. The canvas was wax-resin lined and restretched on an ICA spring stretcher. A layer of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA was applied. Inpainting was carried out. A layer of methacrylate resin L-46 was applied, followed by a final layer of AYAA.

In 1990, the synthetic varnish layers were partially removed; a residual trace of varnish was retained because complete removal resulted in blanching of the paint surface. Some blanching formed in the paint interstices in an area approximately five inches in diameter located in the upper left quadrant. Attempts to remove the blanched material were ineffective, so a thin retouching varnish was rubbed into the areas of blanching. The painting was removed from the ICA spring stretcher and remounted on a keyed tongue and groove stretcher prepared with a loose lining fabric.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition. It is wax-resin lined and loose lined. The canvas is stretched taut, and there are no planar deformations. The tacking edges are moderately worn, especially around the original tack holes, and there is some loss and abrasion of the ground layer, especially along the original foldovers. There are old paper and glue residues on the edges. The paint layer is in good condition. There are a few very small paint losses, including a series of roughly circular losses of paint and ground at intervals along the bottom edge. There are also some localized areas of interlayer cleavage. Some areas of crushed impasto are probably due to the lining procedure, but for the most part the impasto remains intact. There are fine cracks throughout the work, especially spanning thick brushstrokes, as well as stretcher-bar cracks, which are especially prominent in the area of the original vertical crossbar. Some of the cracks have slightly raised edges, but the paint layer is secure. There are some starch-paste residues from the lining procedure in the recesses of the paint texture and facing-paper residues in the upper left corner. There are remnants of old retouching around the edges, although this was mainly removed in the 1990 cleaning. The painting is currently unvarnished.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

Current frame (installed 2008): The frame is not original to the painting. It is a reproduction of a French (Parisian), late-nineteenth-century, architrave frame with cast imbricated and centered laurel-leaf ornament with acanthus-leaf miters. The frame was modeled on a Monet frame from 1881. This frame type also appears in studio photographs framing other water lily paintings. The frame is water gilded over red bole on gesso and cast plaster ornament. The sight molding is burnished, with selective burnishing on the laurel leaf ornament, all other gilding is matte. The gilding is lightly toned and has a glue size. The jelutong-wood molding is mitered and nailed. The molding, from perimeter to interior, is cove; fillet; torus with cast imbricated and centered laurel-leaf ornament with acanthus-leaf miters; fillet; and cove (fig. 44.49).

Previous frame (installed 1991; removed 2008): The work was previously housed in an American, carved reproduction of a French, late-nineteenth-century, architrave frame with a centered guilloche ornament (APF Inc., New York, 1991) (fig. 44.50).

Previous frame (installed by 1975; removed 1991): The work was previously housed in an American, mid-twentieth-century, L-shaped, narrow frame with a gilded face on a mahogany molding with exposed splines at the miters. The frame may be a design by James L. Speyer (fig. 44.51).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris (3/4 interest), and Bernheim-Jeune, Paris (1/4 interest), June 3, 1909, for 14,000 francs.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Henri Bernstein, Paris, May 29, 1909, for 20,000 francs.

Sold by Henri Bernstein, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Aug. 9, 1909, for 20,000 francs.

On deposit from Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Apr. 1911.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Feb. 10, 1914.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, Feb. 10, 1914, for $5,000.

Bequeathed by Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Exhibition History

Paris, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Les nymphéas: Séries de paysages d’eau par Claude Monet, May 6–June 5, 1909, cat. 15, as Série 1906.

Saint Louis, Noonan-Kocian Gallery, Tableaux Durand-Ruel (circuit exhibition, held Oct. 1911–Jan. 1912); Chicago, Auditorium Hotel; Cincinnati, no cat. no.

Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art, Paintings by French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, Nov. 7–Dec. 12, 1937, cat. 16 (ill.).

Bloomington, Ill., Scottish Rite Temple, Central Illinois Art Exposition, Mar. 19–Apr. 8, 1939, cat. 26.

Chicago, Arts Club of Chicago, Origins of Modern Art, Apr. 2–30, 1940, cat. 63.

Sioux City (Iowa) Art Center, Three Old Masters from Art Institute of Chicago, Sept. 4–end Sept. 1949, no cat.

Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, An Experimental Gallery Featuring the Art Historical Background to Impressionism, Oct. 12, 1953–Mar. 31, 1954, no cat.

Wichita (Kans.) Art Museum, Three Centuries of French Painting, May 9–23, 1954, cat. 17.

University of Chicago, Renaissance Society, Painters in Color, Oct. 14–Nov. 14, 1956, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, The Paintings of Claude Monet, Apr. 1–June 15, 1957, no cat. no.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 110 (ill.). (fig. 44.52)

Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, June 27–Aug. 31, 1980, cat. 15 (ill.).

Highland Park, Ill., Neison Harris, July 12–Dec. 19, 1984, no cat.

Tokyo, Seibu Museum of Art, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], Oct. 18–Dec. 17, 1985, cat. 64 (ill.); Fukuoka Art Museum, Jan. 5–Feb. 2, 1986; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Mar. 4–Apr. 13, 1986.

Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel, Claude Monet: Nymphéas, July 20–Oct. 19, 1986, cat. 22 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago’s Dream, a World’s Treasure: The Art Institute of Chicago 1893–1993, Nov. 1–Jan. 9, 1994, no cat. no.

Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, Claude Monet 1840–1926, July 22–Nov. 26, 1995, cat. 130 (ill.). (fig. 44.53)

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Monet in the 20th Century, Sept. 20–Dec. 27, 1998, cat. 32 (ill.); London, Royal Academy of Arts, Jan. 23–Apr. 18, 1999.

Paris, Musée National de l’Orangerie, Monet: Le cycle des Nymphéas, May 6–Aug. 2, 1999, cat. 15 (ill.).

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 91 (ill.).

Selected References

Galeries Durand-Ruel, Les nymphéas, séries de paysages d’eau par Claude Monet, exh. cat. (Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1909), cat. 15.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 162, cat. 2139.

Gustave Geffroy, “Claude Monet,” L’art et les artistes 2, 11 (Nov. 1920), p. 73 (ill.).

M. C., “Monets in the Art Institute,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 2 (Feb. 1925), p. 20.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für freunde und sammler der kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 77. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Toledo Museum of Art, Catalogue: Paintings by French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists (Toledo Museum of Art, 1937), cat. 16 (ill.).

George Slocombe, “Giver of Light,” Coronet (Mar. 1938), p. 26 (ill.).

Scottish Rite Temple, Central Illinois Art Exposition, exh. cat. (Scottish Rite Temple, 1939), p. 13, cat. 26.

Arts Club of Chicago, Origins of Modern Art, exh. cat. (Arts Club of Chicago, 1940), p. 15, cat. 63.

Oscar Reuterswärd, Monet: En konstnärshistorik (Bonniers, 1948), p. 288.

Wichita Art Museum, Three Centuries of French Painting, exh cat. (Wichita Art Museum, 1954), p. 3, cat. 17.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Catalogue,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 51, 2 (Apr. 1, 1957), p. 34.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 322.

A. James Speyer, “Twentieth-Century European Paintings and Sculpture,” Apollo 84, no. 55 (Sept. 1966), p. 222.

Denis Rouart and Jean-Dominique Rey, Monet, nymphéas, ou Les miroirs du temps, with a cat. rais. by Robert Maillard (Hazan, 1972), p. 159 (ill.). Translated by David RadzinowiczasMonet, Water Lilies: The Complete Series, rev. ed., with a cat. rais. by Julie Rouart with Camille Sourisse (Flammarion/Rizzoli, 2008), p. 124 (ill.).

Grace Seiberling, “The Evolution of an Impressionist,” in Paintings by Monet, ed. Susan Wise, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), pp. 37, 38.

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 167, cat. 110 (ill.).

Grace Seiberling, Monet’s Series (Garland, 1981), pp. 228; 407, no. 33; fig. 33.

A. James Speyer and Courtney Graham Donnell, Twentieth-Century European Paintings (University of Chicago Press, 1980), p. 59, cat. 3B3; microfiche 3, no. B3 (ill.).

Musée Toulouse-Lautrec and Art Institute of Chicago, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, exh. cat. (Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, 1980), p. 35, no. 15 (ill.); 67.

Art Institute of Chicago, Seibu Museum of Art, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, and Fukuoka Art Museum, eds., Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], exh. cat. (Nippon Television Network, 1985), pp. 126, cat. 64 (ill.); 127 (detail); 161.

Charles F. Stuckey, ed., Monet: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1985), pp. 255; 263, pl. 103.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 4, Peintures, 1899–1926 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1985), pp. 214; 215, cat. 1683 (ill.); 376, letters 1885, 1887, 1888, 1890, 1891; 377, letter 1897; 429, piéces justificative 213, 215.

Christian Geelhaar, et al., Claude Monet: Nymphéas, Impression, Vision, exh. cat. (Kunstmuseum Basel, 1986), pp. 52, cat. 22 (ill.); 173.

Richard R. Brettell, Post-Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 111; 115 (ill.); 118.

Charles F. Stuckey, Monet, Water Lilies (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1988), p. 37, pl. 12.

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 63 (detail); 65; 102, pl. 31; 109.

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 152, cat. 130 (ill.); 241; 243.

Paul Hayes Tucker, “Passion and Patriotism in Monet’s Late Work,” in New Orleans Museum of Art and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Monet: Late Paintings of Giverny from the Musée Marmottan, exh. cat. (New Orleans Museum of Art/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/Abrams, 1995), pp. 37, fig. 10; 40.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism, cat. rais., vol. 1 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), p. 358, cat. 1683 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 4, Nos. 1596–1983 et les grandes décorations (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), p. 764, cat. 1638 (ill.); 765.

James N. Wood and Teri J. Edelstein, The Art Institute of Chicago: Twentieth-Century Painting and Sculpture (Art Institute of Chicago, 1996), p. 11 (ill.).

Lynn Gamwell, “Arcadian Impulses in Avant-Garde Art,” in Donald Kuspit and Lynn Gamwell, Health and Happiness in 20th-Century Avant-Garde Art, exh. cat. (Cornell University Press/Binghamton University Art Museum, State University of New York, 1996), pp. 52; 55, fig. 37.

Donald Kuspit, “Happiness, Health, and Related Anomalies of Avant-Garde Art,” in Donald Kuspit and Lynn Gamwell, Health and Happiness in 20th-Century Avant-Garde Art, exh. cat. (Cornell University Press/Binghamton University Art Museum, State University of New York, 1996), p. 44.

Genevieve Morgan, ed., Monet: The Artist Speaks (Collins, 1996), pp. 81 (ill.), 95.

Meyer Schapiro, Impressionism: Reflections and Perceptions (Braziller, 1997), pp. 198–99, fig. 98; 220.

Victor I. Stoichita, A Short History of the Shadow (Reaktion, 1997), pp. 107–08, ill. 36; 109; 208

Warren Adelson, “In the Modernist Camp,” in Sargent Abroad: Figures and Landscapes, by Warren Adelson, Donna Seldin Janis, Elaine Kilmurray, Richard Ormond, and Elizabeth Oustinoff (Abbeville, 1997), pp. 28; 29, pl. 16; 39.

Richard Ormond, “In the Alps,” in Warren Adelson, Donna Seldin Janis, Elaine Kilmurray, Richard Ormond, and Elizabeth Oustinoff, Sargent Abroad: Figures and Landscapes (Abbeville, 1997), p. 100.

Vivian Russell, Monet’s Water Lilies (Little, Brown/Frances Lincoln, 1998), pp. 64–65 (ill.), 93.

George T. M. Shackelford and MaryAnne Stevens, “Water Lilies (Series of Water Landscapes), 1903–1909,” in Paul Hayes Tucker, with George T. M. Shackelford and MaryAnne Stevens, Monet in the 20th Century, exh. cat. (Royal Academy of Arts, London/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Yale University Press, 1998), pp. 148; 158 (detail); 159, cat. 32 (ill.).

Paul Hayes Tucker, “The Revolution in the Garden: Monet in the Twentieth Century,” in Paul Hayes Tucker, with George T. M. Shackelford and MaryAnne Stevens, Monet in the 20th Century, exh. cat. (Royal Academy of Arts, London/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Yale University Press, 1998), pp. 44–45.

Connaissance des Arts and Pierre Georgel, “Monet: L’art de la métaphore,” Connaissance des arts 561 (May 1999), pp. 44–45, fig. 2.

“Monet, les nymphéas: L’exposition,” special issue, Connaissance des arts, 137 (Société Française de Promotion Artistique, 1999), pp. 14–15, ill. 13.

Pierre Geogel, with the assistance of Chantal Georgel and Jacqueline Séjourné, Monet: Le cycle des Nymphéas, Catalogue sommaire, exh. cat. (Musée National de l’Orangerie/Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), pp. 38; 92, cat. 15 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), p. 163 (ill.).

Debra N. Mancoff, Monet’s Garden in Art (Viking Studio, 2001), pp. 60 (detail), 66–67 (detail), 143.

Karin Sagner-Düchting, “Monet’s Late Work from the Vantage Point of Modernism,” in Monet and Modernism, ed. Karin Sagner-Düchting, exh. cat. (Prestel, 2001), p. 25.

Karin Sagner-Düchting, “The Waterlilies in Giverny and the Grande Décoration,” in Monet and Modernism, ed. Karin Sagner-Düchting, exh. cat. (Prestel, 2001), pp. 68, 76 (ill.).

James Tanaka, Daniel Weiskopf, and Pepper Williams, “The Role of Color in High-Level Vision,” TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences 5, 5 (May 2001), p. 213, fig. 1.

Sothebys, New York, Impressionist and Modern Art, Part One, sale cat. (Sotheby’s, Nov. 5, 2002), pp. 45, fig. 3; 46.

Debra N. Mancoff, Monet: Nature into Art (Publications International, 2003), pp. 103, 111 (ill.).

Lisa Stein, “Seeing Beyond the Must-Sees,” Chicago Tribune, Apr. 18, 2003, section 7, p. 1 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, The Essential Guide,rev. ed., selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago, 2003), p. 246 (ill.)

Margaret Werth, “‘A Long Entwined Effort’: Colonizing Giverny,” in Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915, ed. Katherine M. Bourguignon, exh. cat. (Terra Foundation for American Art/Musée d’Art Américain Giverny/University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 70, fig. 13.

Eric M. Zafran, “Monet in America,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), p. 113.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 161; 163; 174–75, cat. 91 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 161; 163; 174–75, cat. 91 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, The Essential Guide (Art Institute of Chicago, 2009), p. 232 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Archival Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 9082, Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock book 1901–13

Inventory number

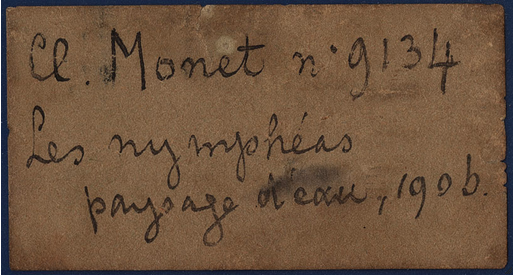

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 9134, Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock book 1901–13

Inventory number

Deposit Durand-Ruel New York 7606, Durand-Ruel, New York deposit book 1894–1925

Inventory number

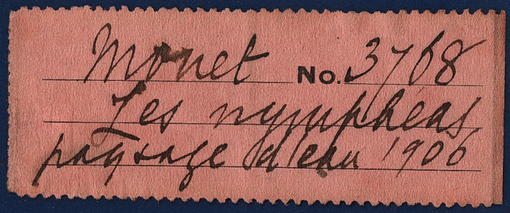

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 3768, Durand-Ruel, New York, stock book 1904–1924

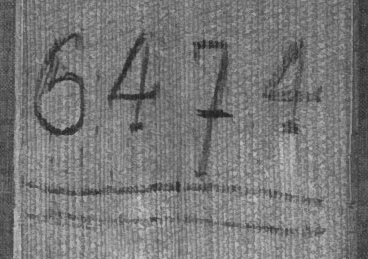

Photograph number

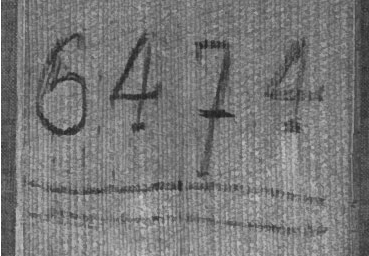

Photo Durand-Ruel, Paris no. 6474

Other Documents

Label (fig. 44.54)

Label (fig. 44.55)

Inscription (fig. 44.56)

Inscription (fig. 44.57)

Inscription (fig. 44.58)

Inscription (fig. 44.59)

Purchase receipt, Feb. 10, 1914

Labels and Inscriptions

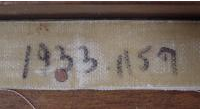

Undated

Number

Location: lining canvas

Method: handwritten script

Content: 1933.1157 (fig. 44.60)

Inscription

Location: frame

Method: handwritten script

Content: TOP (fig. 44.61)

Pre-1980

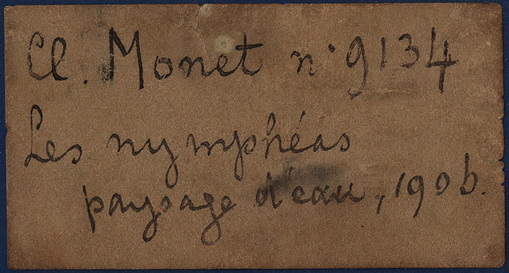

Label

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: Cl. Monet no 9134 / Les nymphéas / paysage d’eau, 1906. (fig. 44.62)

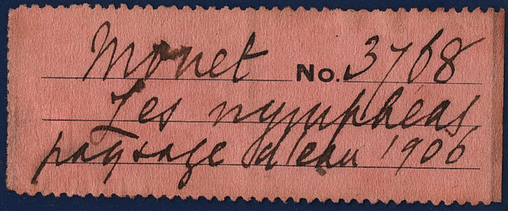

Label

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: Monet No. 3768 / Les nymphéas / paysage d’eau 1906 (fig. 44.63)

Label

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on label with red border

Content: 1827 / 1 (fig. 44.64)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 6474 (fig. 44.65)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 15 (fig. 44.66)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: D-R [90?]82 (fig. 44.67)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: D-R 9134 (fig. 44.68)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: DR 9134 (fig. 44.69)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 17596 (fig. 44.70)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 33.1157 (fig. 44.71)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 35 1/4 × 36 1/2 (fig. 44.72)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 35 1/4 × 36 1/2 (fig. 44.73)

Number

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: 39 – 20 7/8 (fig. 44.74)

Inscription

Location: pre-1974-treatment stretcher (discarded); 1974 photograph in conservation file

Method: handwritten script

Content: Box 4[?] (fig. 44.75)

Label

Location: 1974 stretcher (discarded); transcription in conservation file

Method: not documented

Content: I.C.A. SPRING STRETCHERS / OBERLIN, OHIO 44074 (fig. 44.76)

Post-1980

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / ARTIST: Claude Monet / TITLE: Water Lilies (1906) / MEDIUM: Oil on canvas / CREDIT: Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Coll. / ACC.#: 1933.1157 (fig. 44.77)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / “Claude Monet: 1840–1926” / July 14, 1995–November 26, 1995 / Catalog: 130 / Water Lilies / Nymphéas / The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. / Ryerson Collection (1933.1157) (fig. 44.78)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: MONET IN THE 20TH CENTURY / Museum of Fine Arts, Boston / September 20-December 27, 1998 / Royal Academy of Arts, London / January 21–April 18, 1999 / Cat. 32 W. 1683 / Nymphéas; Water Lilies, 1906 / The Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 44.79)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter.

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75H (B+W 486 UV IR cut MRC filter, X-NiteCC1 filter, and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Electron Microprobe

Applied Research Laboratories (ARL) electron microprobe analyzer. Analysis was carried out at McCrone Associates.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

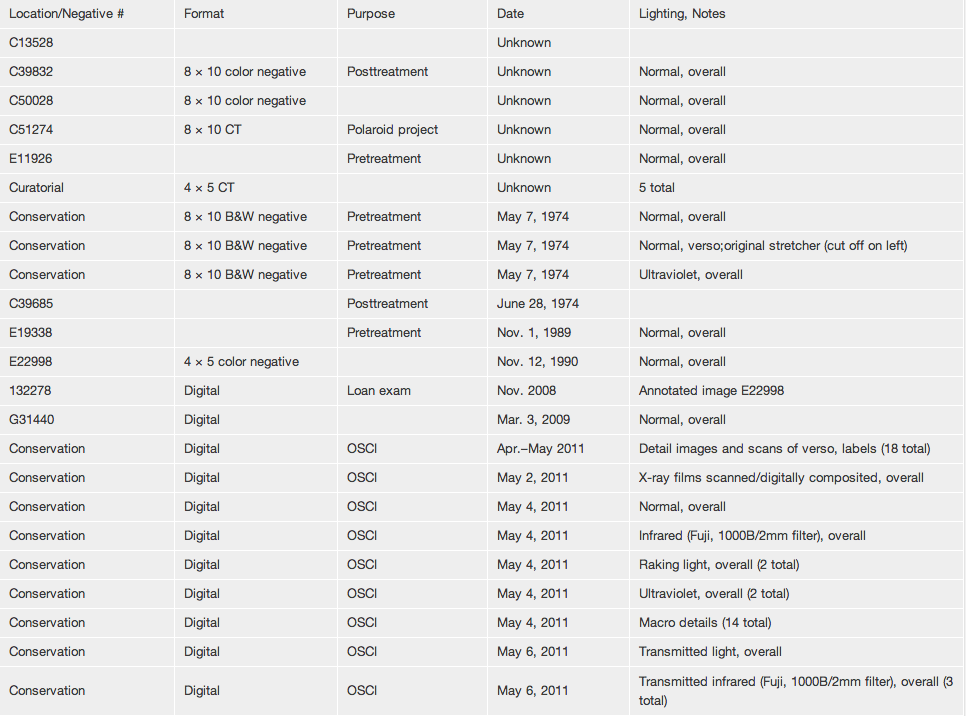

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 44.80).