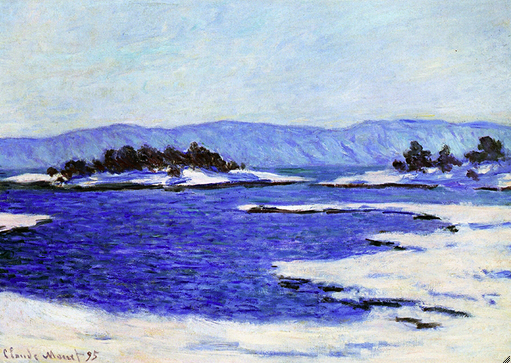

Cat. 34

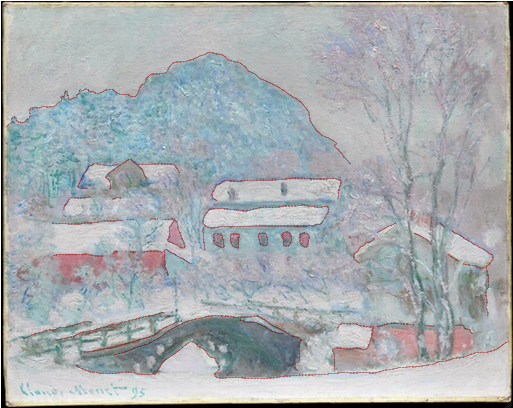

Sandvika, Norway

1895

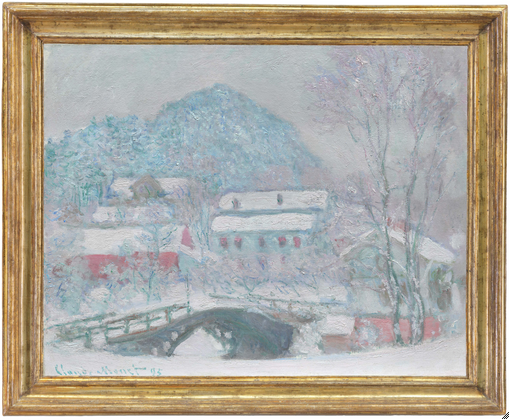

Oil on canvas; 73.4 × 92.5 cm (28 7/8 × 36 3/8 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 95 (lower left, in greenish-blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Bruce Borland, 1961.790

Norwegian Adventure

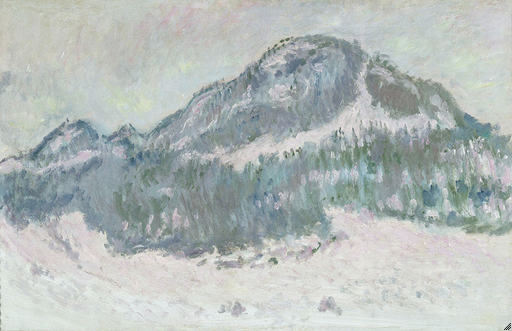

In Claude Monet’s painterly quest to depict the seasonal variations of nature under differing atmospheric conditions, even the dormant winter was filled with promise. Snow was something he had treated since the 1860s, but his painting Sandvika, Norway, depicting the Norwegian village of that name near Christiania (now Oslo), was particularly meaningful. It was one of over two dozen that were begun during the artist’s two-month visit to Norway in early 1895. Monet focused on six motifs there: in addition to six, nearly identical, views of Sandvika, Monet painted local wooden houses (fig. 15.28 [W1393], fig. 15.21 [W1394], and fig. 15.49 [W1404]), the Christiana fjord (fig. 15.50 [W1402]), and Mount Kolsaas (fig. 15.51 [W1415]), the last of which he painted at least a dozen times. Monet treasured the paintings that he had made during his voyage to Norway, even though none sold after they were first exhibited at Durand-Ruel in May 1895.

In 1899, however, Monet personally donated Sandvika, Norway, now in the Art Institute’s collection, to the sale organized to benefit the children of Impressionist painter Alfred Sisley after his death. Aside from this painting, which was aquired by Durand-Ruel at that sale, as well as eight additional Norwegian works that the dealer purchased in 1900–01, Monet held on to most of the Norway paintings until his death. But despite the fact that Monet depicted Sandvika as a peaceful winter wonderland, the circumstances under which the series was painted were far from idyllic for him.

Why Norway?

The precise reason for Monet’s trip is unknown; however, it was likely instigated by a combination of factors. The general cultural climate may have played a part: Norwegian literature, theater, and music were fashionable in France in the early 1890s, perhaps piquing Monet’s interest in exploring a country in which his work had been warmly received since 1883. It is also possible that Fritz Thaulow, the Norwegian painter who was an acquaintance of Monet, may have encouraged him to visit. Most compelling, perhaps, was that Monet’s stepson, Jacques Hoschedé, had moved to Christiania in 1894, and the family was eager for an eyewitness report. Painting was certainly also a priority, for Monet brought with him canvases from home. Sandvika, Norway bears no canvas stamp, but it has been found to have a warp-thread match with seven other Monet paintings in the Art Institute’s collection (dating from before and after his Norway trip), suggesting that the canvas on which it is painted was purchased from the Paris supplier Troisgros Frères (see Technical Report).

Monet was not initially impressed with Norway. Getting there required a long and difficult journey via multiple trains and ferries that were delayed by the harsh winter weather; he departed Giverny on January 28 and did not arrive until February 1. Upon his arrival in Christiania, he was dismayed to find the fjords icy and covered in snow. A multiday trip by sleigh to scope out sites and motifs with his stepson changed his outlook completely. The mountains and the frozen waterfalls he saw captivated him, and within two weeks after his arrival, he was writing home about his intention to begin painting. Many of the potential sites were not accessible by train or sleigh, only on skis, however, which limited his choices.

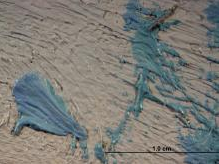

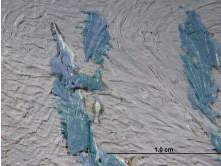

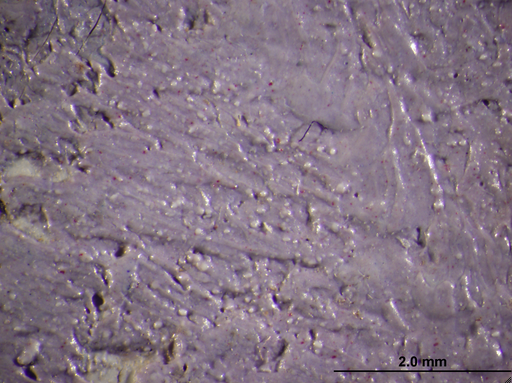

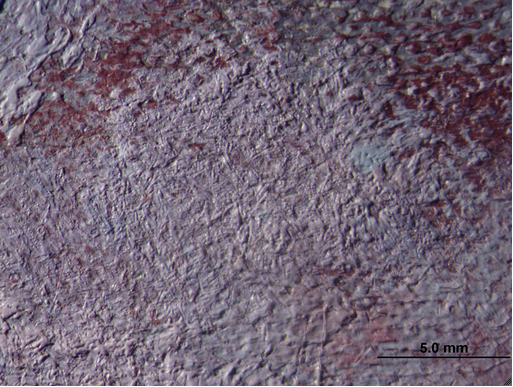

Having selected what to paint, Monet experienced further logistical difficulties. He was frustrated over the time he had to spend traveling to and from the motifs he had selected, as well as the trouble it took to set up his painting equipment once he got there. He also had to adapt to the extreme weather in Norway, but this was an accomplishment that filled him with pride. “I have bought equipment, shoes, hats, clothes, etc., and it will have to be very cold before I start to freeze,” Monet wrote to his wife. “But I am coping well with it, to the considerable amazement of the people here, who are themselves rather sensitive to the cold.” Having to travel by sled simply to get to the sites exposed him to the bitter winter weather. It is tempting to think that the areas found in Sandvika, Norway where soft paint appears to have been pressed by a fibrous material were the result of Monet's having to transport his canvases and extra equipment by sleigh while wearing all of his additional clothing (fig. 15.23; see Technical Report).

The Challenges of Norway

The ups and downs Monet experienced in Norway were typical of most of his painting expeditions from the 1880s onward: momentary frustration would lead him to question the campaign, but by the end of his trip, he would regret that he did not have more time to paint his carefully selected subjects (see, e.g., cats. 38–41 and cat. 45). By February 15, Monet at last revealed that his trip could be productive. As he explained to Alice, “It has been two days since I wrote to you, because although still feeling very low and on the point of taking the boat for Le Havre [to come home], I wished nonetheless to try to find myself a little corner, where I could work without having to go everywhere by sleigh or by train. And after my walk, which I still find enchanting, I believe I have finally found it. I have just settled in, three quarters of an hour away from Christiania.” The “little corner” he had found for himself was Sandvika, the subject of the Art Institute’s painting.

Monet’s troubles did not end once he found his motifs. He soon discovered the complications posed by moments of intense sunshine. “I am trying to summon all my courage and all my willpower so as to begin my week tomorrow morning,” he wrote Alice on February 24. “My canvases are prepared, I know where I ought to be at various times of the day, weather permitting, for there are places which I have seen in cloudy weather which are impossible in sunshine, the snow is so brilliant and blinding to the eyes.” Furthermore, the changing condition of the snow caused by the sun’s rays was an additional source of aggravation. Writing about the marvelous sight of freshly fallen snow on fir trees, Monet expressed his frustration: “I am even more furious because this will not last,” he wrote to his stepdaughter on March 1. “One hour of sunshine or a little wind and it will all fall off.”

Norway and Japan

In that same letter to his stepdaughter, Monet curiously described one of his chosen Norwegian motifs by referencing an even more foreign land—Japan: “I have begun painting a view of Sandviken which resembles a Japanese village, and I am also painting a mountain which is visible from all directions here and which makes me think of Fuji-Yama.” Numerous scholars have commented upon the influence of Japanese woodblock prints on Monet’s work, and Monet’s comment here is often cited to support that. Joel Isaacson has noted the compositional similarities between the Sandvika series and prints by Utagawa Hiroshige such as Kanbara, Evening Snow (fig. 15.17) and The Compound of the Tenman Shrine at Kameido in the Snow (fig. 15.18). Indeed, elements of the Chicago picture bear a strong resemblance to these prints: Monet’s depiction of the village is nestled between the curved frame of snow in the foreground and the rising mountain in the background; the angular roofs of the snow-topped houses—made from thick strokes of stiff white paint—punctuate the landscape of icy trees; and the foreshortened Lökke Bridge creates a distinct diagonal line that leads the viewer into the painting in a zigzag fashion.

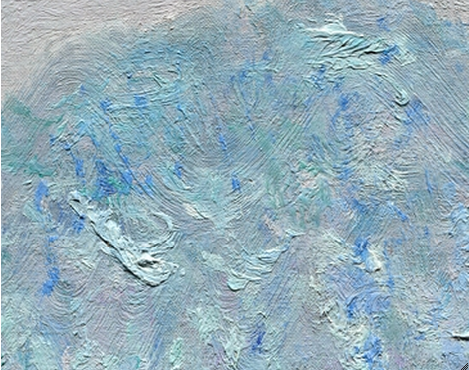

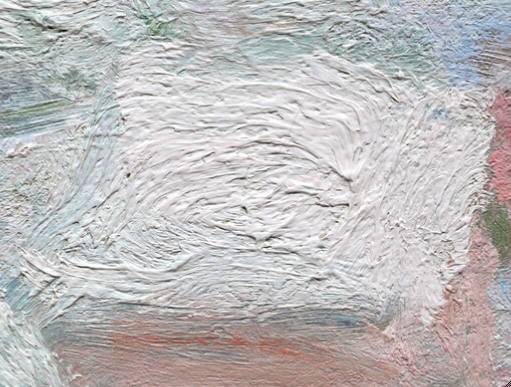

The similarities between Monet’s paintings and Japanese prints notwithstanding, the Sandvika pictures include many features that highlight his grounding in Western artistic practice, as noted by Paul Tucker. In particular, this is apparent in Monet’s attempts to capture environmental effects by using textured surfaces and modulated color. Tucker pinpoints a difference in the treatment of mountains by the two artists: “[U]nlike Mount Fuji, Monet’s mountain does more than rise and fall. It expands and contracts, trembles and hovers, pushes and strains . . . the mountain refuses to be restrained by a kind of rationale or graphic clarity that characterizes Hokusai’s Mount Fuji.” Although Tucker’s statement here is specific to Monet’s paintings of Mount Kolsaas (see fig. 15.51), the observation holds true for the Art Institute’s painting of Sandvika. In order to capture the “vast whiteness” of the environment, Monet’s palette consisted of mostly lead white, which he used to subdue and vary his rather limited use of color (see Technical Report). Furthermore, texture abounds in Monet’s depiction of the mountain in Sandvika: he built up the surface with thick, wavy strokes that were painted over but still remain visible; he applied short, textured strokes of low impasto; and he added final touches of more intense blues and greens to further complicate the network of brushstrokes he had already laid in (fig. 15.22). These variously applied paint layers create the shimmering and glistening effect of snow, a concern that is not shared by Japanese printmakers like Hiroshige or Hokusai when treating similar themes.

Creating Sandvika

The complex textured surface of the Art Institute’s Sandvika was the result of multiple work sessions, which is evident from the presence of wet-over-dry brushwork at various stages of the painting process (see Technical Report). A few of the more colorful touches, including some of the blue- and rose-toned strokes scattered throughout the landscape, were among the last additions to the picture. The application of finishing touches in the studio is in keeping with Monet’s practice of the 1890s, as we now know that he spent much time on his series paintings back in his Giverny studio (e.g., Stacks of Wheat cats. 27–32), delaying their exhibition so he could continue perfecting their color harmonies (e.g., London [cats. 38–41]). This was not the case with the Norwegian pictures: Monet exhibited eight of them, including the Chicago painting, at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in May 1895, shortly upon his return to France. The show, which was scheduled rather hastily, also featured works from Monet’s series of paintings of Rouen Cathedral, which he had long postponed exhibiting, as well as a selection of pieces from his previous series, making it a kind of mini-retrospective. The inclusion of the Norway paintings in this show, as argued by Paul Tucker, suggests that Monet wanted to advance his reputation as a painter with an international dimension.

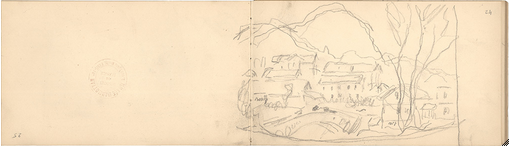

It is impossible to know whether Monet completed Sandvika during his trip, finished it in the month or so prior to the exhibition, or retouched it after the show but before placing it in the sale to benefit Sisley’s family. Regardless of when Monet applied his final brushstrokes to Sandvika, he held to the claim he made during an interview in Norway: “I am pursuing the impossible. Other painters paint a bridge, a house, a boat . . . I want to paint the air in which the bridge, the house, and the boat are to be found—the beauty of the air around them, and that is nothing less than the impossible.” Indeed, Monet was not especially concerned with modifying forms in this painting, for the bridge, the houses, and the other features included in the picture differ little from those seen in the related drawing (fig. 15.52 [D399]), perhaps the most elaborate of the thirty sketches he brought back in his carnet. Furthermore, technical examination of the Art Institute’s canvas indicates that Monet did not make any significant compositional changes to it during the course of its execution.

Jill Shaw

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Claude Monet’s Sandvika, Norway was painted on a [glossary:pre-primed], no. 30 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size linen [glossary:canvas]. The work appears to retain its original [glossary:stretcher]. A [glossary:warp-thread match] was detected with seven other Monet paintings from the Art Institute's collection: The Petite Creuse River (1889; 1922.432 [W1231]) (cat. 25), Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) (1890/91; 1985.1103 [W1269]) (cat. 27), Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn) (1890/91; 1933.444 [W1270]) (cat. 28), Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) (1890/91; 1922.431 [W1278]) (cat. 29), Stack of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset) (1890/91; 1983.166 [W1284]) (cat. 32), Branch of the Seine near Giverny (Mist) (1897; 1933.1156 [W1475]) (cat. 36), and Water Lily Pond (1900; 1933.441 [W1628]) (cat. 37), suggesting that the fabric from these paintings came from the same [glossary:bolt] of material. The [glossary:ground] consists of a single, off-white layer. Charcoal was detected in one small area at the top edge of the painting; however, there was insufficient material to be able to suggest that this could relate to preparatory drawing. The painting has a textured surface with dense applications of paint used in the snow-covered areas and more open, textural brushstrokes used to build up the mountain, trees, and bridge. The presence of [glossary:wet-over-dry] paint applications throughout the composition indicates that the painting was carried out in more than one session. Most of the surface brushwork, on the other hand, was applied [glossary:wet-in-wet]. In general, the paint has a thick, viscous consistency. No changes to the composition as the painting was built up were detected.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 15.66).

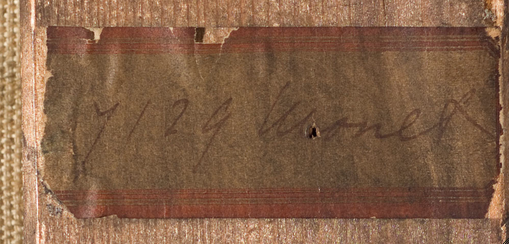

Signature

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 95 (lower left, in greenish-blue paint) (fig. 1). The signature and date were applied when the underlying paint layers were dry (fig. 2).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The original dimensions were approximately 72 × 91 cm. This corresponds closely to a no. 30 portrait (figure) standard-size canvas (90 × 73 cm), turned horizontally.

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 23.4V (0.6) × 21.4H (0.6) threads/cm; the vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft]. A warp-thread match was found with seven other Monet paintings in the Art Institute’s collection: The Petite Creuse River (1889; 1922.432 [W1231]) (cat. 25), Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) (1890/91; 1985.1103 [W1269]) (cat. 27), Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn) (1890/91; 1933.444 [W1270]) (cat. 28), Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) (1890/91; 1922.431 [W1278]) (cat. 29), Stack of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset) (1890/91; 1983.166 [W1284]) (cat. 32), Branch of the Seine near Giverny (Mist) (1897; 1933.1156 [W1475]) (cat. 36), and Water Lily Pond (1900; 1933.441 [W1628]) (cat. 37).

Canvas characteristics

There is moderate [glossary:cusping] on the left and right sides, and milder and more even cusping along the top and bottom edges.

Stretching

Current stretching: Dates to [glossary:aqueous lining] applied prior to acquisition in 1961 (see Conservation History); tacks spaced 3–5 cm apart. It appears that some of the original tack holes were reused when the painting was restretched after [glossary:lining]; not all of the edges could be fully examined, however, due to the presence of paper edge strips.

Original stretching: The majority of the original tack holes are spaced 4–5 cm apart. The cusping appears to correspond to the placement of the original tack holes.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: The current stretcher may be the original stretcher. It is a keyable wooden stretcher consisting of five members, with a vertical [glossary:crossbar], and [glossary:mortise and tenon joints] (fig. 15.20). Depth: 2 cm.

Original stretcher: See above.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

None observed in current examination or documented in previous examinations.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

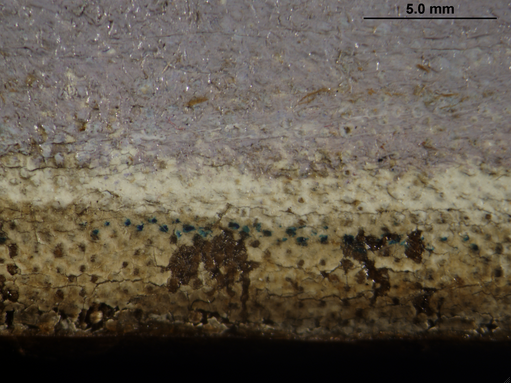

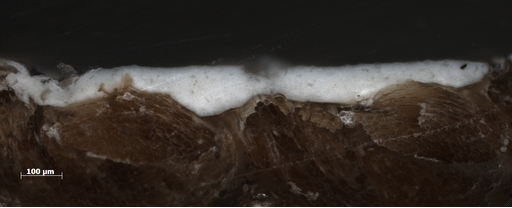

The ground extends to the edges of all four [glossary:tacking margins], suggesting that the canvas was cut from a larger piece of primed fabric, which was probably commercially prepared. The ground consists of a single layer that measures 20 to 120 µm in thickness (fig. 15.67).

Color

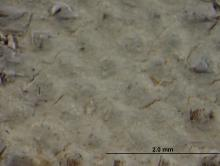

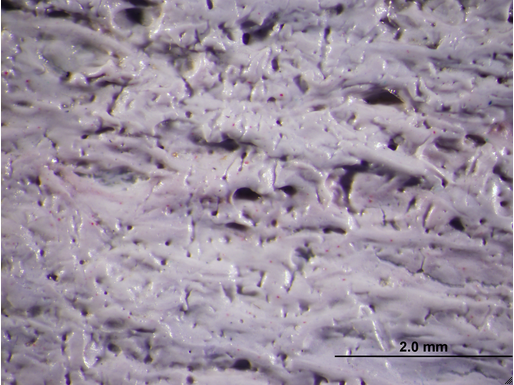

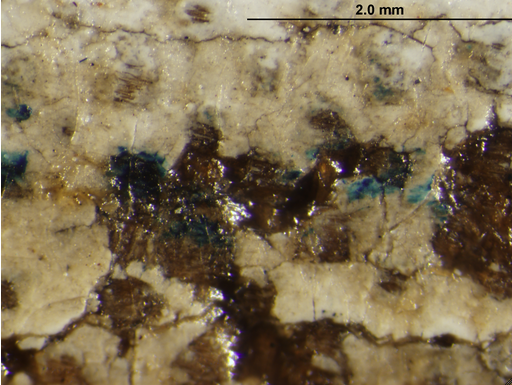

The ground layer is off-white with some red and dark, possibly black, particles visible under magnification (fig. 3).

Materials/composition

Analysis indicates that the ground contains lead white and calcium carbonate (chalk) with traces of bone black, iron oxide, alumina, silica, and various silicates. Binder: [glossary:Oil] (estimated).

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No [glossary:underdrawing] was observed with [glossary:infrared reflectography] (IRR). One localized area of black particulate material, however, was observed microscopically near the top edge of the painting (fig. 4). The black particles lie directly over the ground layer and are partially covered by paint.

Medium/technique

Charcoal.

Revisions

Insufficient material was detected to be able to confirm whether the charcoal is part of an underdrawing campaign or whether it is an incidental accretion.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

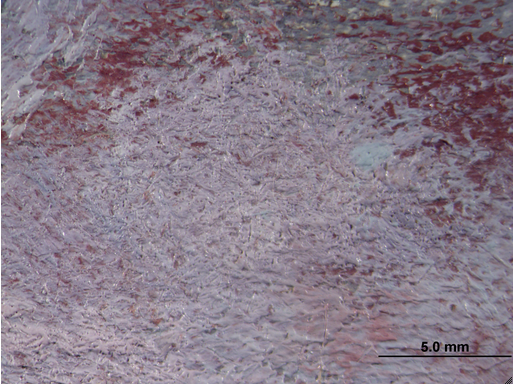

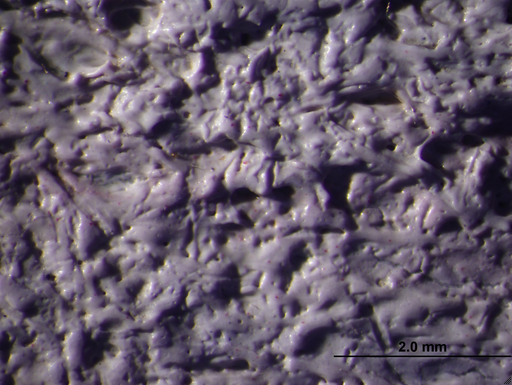

The painting was densely built up with thick, textural brushwork that often completely obscures the texture of the canvas [glossary:weave] (fig. 5, fig. 6). In localized areas—mainly along the borders of compositional forms—however, the ground layer remains visible (fig. 8). The painting is somewhat sketchy at the edges and the upper-left corner, where ground was also left exposed (fig. 10). At the upper-right corner, it appears that the artist applied some final touches of pale-pink to finish the edges (fig. 9). Although the thickly painted surface makes it difficult to gain a full sense of the buildup of the painting, it seems that the composition was laid in using gray and brownish tones that were thinly applied and show the texture of the canvas weave. These earliest paint layers remain visible occasionally on the surface and can be seen, for example, in the gray underlayer of the bridge (fig. 7). In this area, and elsewhere on the painting, it appears that the artist may have wiped the thin, fluid paint, removing it from the peaks of the canvas weave in places, before building up the painting. Bluish-gray tones were used to lay in the sky, and greenish-gray underlayers were observed in areas of foliage. For the initial painting, the artist used broader strokes and possibly also slightly wider brushes. This can be seen, for example, in the upper-right corner of the sky underneath the tree branches (fig. 12.12) and also in the undulating, zigzag strokes used near the peak of the mountain (fig. 12.13). The texture of these underlying strokes remains visible on the surface of the painting; they appear to have been dry when subsequent paint layers were applied on top, indicating that the painting was carried out in more than one session (fig. 12.14, fig. 15.30). The artist made no apparent alterations to the composition as the painting was worked up.

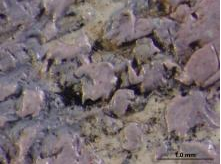

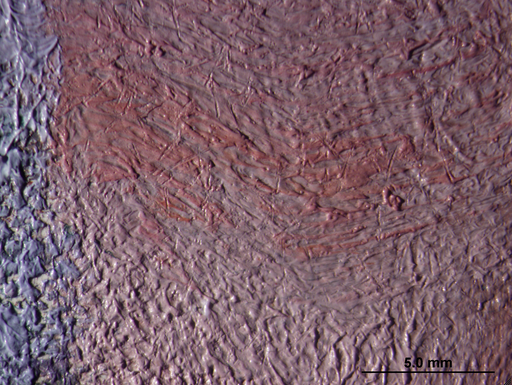

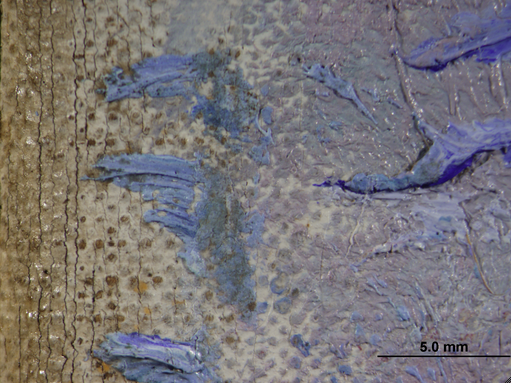

Most of the surface brushwork was applied wet-in-wet and consists of discrete, textured strokes and low [glossary:impasto]. For example, the mountain, which was built up from an initial [glossary:lay-in] of thinly applied strokes in various tones of gray, consists of an open network of short strokes of lead white–rich impasto applied wet-in-wet, with final touches of blue and green added when those thick brushstrokes were still wet (fig. 15.31). In the trees just below, similar blue and green strokes were used to delineate the branches (fig. 17.71). The heavy snow-covered areas in the foreground and on the roofs of the buildings consist of thicker, more-continuous paint layers with strokes worked wet-into-wet (fig. 15.32). The consistency of the paint seems quite viscous, almost stiff, particularly in these thickly applied areas (fig. 17.72). This is most evident in places where the paint has been drawn up by the brush in low peaks (fig. 15.34). In some of these thickly painted areas, numerous bubble holes were often observed (fig. 15.35). In several places, the surface of the painting looks like it has been pressed with a fibrous material (fig. 15.36, fig. 15.33); the resulting marks were made in the paint when it was still soft (fig. 15.37). It is difficult to say whether this was done intentionally (for example, to rough up the surface) or whether it is the result of a fabric having been pressed against the paint surface (e.g., from transporting or storing the work). It must have occurred at some point during the painting process since subsequent, higher-relief strokes adjacent to these areas were not affected (fig. 15.38).

There is a narrow band of disturbed paint along the bottom edge of the painting, caused from something having been pressed against the paint while it was still wet. The area is approximately 1.0 cm wide and 50 cm long and is located approximately 1.0 cm from the bottom edge. Such a mark could be from an easel or some kind of transport case (fig. 15.40). The affected area of paint was dry when the date was applied on top. In several places around the edges of the composition, the paint looks flattened, as if the work had been framed while the paint was still soft (fig. 15.41, fig. 15.42).

Traces of a thin, dark-blue line are visible intermittently around the edges of the painting. The line appears to have been executed with paint, which was very lightly applied and deposited only on the high points of the canvas weave (fig. 15.43). It is present, at least intermittently, on all four sides. It seems to lie directly on top of the ground layer just outside the borders of the painted composition. In one place it appears to continue over an area of loss in the ground layer (fig. 15.44). It is uncertain when the line was applied and what its function was.

Painting tools

Brushes, including 0.5 and 1.0–1.5 cm wide, flat ferrule (based on width and shape of brushstrokes). Many brush hairs are embedded in the paint surface.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, chrome yellow, vermilion, red lake, emerald green, viridian, cobalt blue, and ultramarine blue. The presence of a pale-to-bright-pink [glossary:fluorescence] under ultraviolet light indicates that the artist used red lake throughout the work. Small white clusters were observed in some lead white–rich areas of the painting (fig. 18.74).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting was cleaned in 2007 and left unvarnished (see Conservation History). The painting has a soft, relatively matte surface. There are some yellowed [glossary:varnish] residues in the recesses of the paint texture.

Conservation History

A 1962 examination report states that the painting was already lined with an aqueous adhesive at that point and had a yellowed [glossary:varnish] layer. The report also mentions the presence of “toning” in areas where glue adhesive had collected on the paint surface.

In 1962, the painting was cleaned to remove yellowed varnish. A spray coat of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA and methacrylate L-46 was applied. The painting was reframed, and the back was sealed with Mylar.

In 2007, the AYAA/methacrylate coating and surface grime were removed. Minor [glossary:inpainting] was carried out at the lower right corner. The painting was left unvarnished.

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition. The canvas is lined with an aqueous adhesive and is stretched taut on the stretcher. There are some light undulations at the lower-left and lower-right corners. There is general wear and abrasion on the tacking edges, which are partially covered with paper strips. The adhesive used to attach the paper strips has contracted and pulled up the ground layer in places. The [glossary:tacking edges] are dirty and yellowed from the adhesive used to attach the paper edge strips. The paint layer is secure with only a few tiny, old losses down to the canvas. Cracking is minimal and, where present, is very fine. It is mainly limited to a few areas of thickly applied, lead white–rich paint. There is some [glossary:retouching] around the edges and at a few small areas of loss within the composition. The retouching is slightly mismatched. The painting is currently unvarnished. There are a few areas of yellowed varnish residues in the recesses of the paint texture.

Kimberley Muir

Frame

Current frame (installed in 2008): The frame is not original to the painting. It is an Italian, second-half-of-the-seventeenth-century, Salvator Rosa, cavetto frame with a stepped ogee sight. The frame is gilded with silver leaf over yellowish–raw sienna bole on gesso. The gilding is slightly burnished and retains its original Mecca varnish finish and glue [glossary:size]. The back flat edge of the frame was not gilded and is painted with raw sienna. The frame is made of poplar, with applied mitered back, front, and sight moldings on a half-lapped cassetta base. The molding, from perimeter to interior, is fillet; scotia; fillet; torus; stepped ogee; and cove (fig. 15.45).

Previous frame (installed by 1975; removed in 2008): The work was previously housed in an American, mid-twentieth-century reproduction of a seventeenth-century, Spanish, gilt, architrave frame with stylized-leaf molding and bead-and-bobbin sight molding with an independent linen-covered liner (APF Inc., New York) (fig. 15.53).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Donated by the artist to the Alfred Sisley Sale, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 1, 1899, lot 65.

Sold at the Alfred Sisley Sale, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 1, 1899, lot 65, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, for 6,300 francs.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, Oct. 24 or Nov. 13, 1900.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Mrs. John Jay (Harriet Blair) Borland, Chicago, Feb. 13, 1901, for $3,500.

By descent from Mrs. John Jay (Harriet Blair) Borland (died 1933), Chicago, to her son, Bruce Borland.

Given by Bruce Borland, Chicago, to the Art Institute, beginning in 1961.

Exhibition History

Paris, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Exposition de tableaux de Claude Monet, May 10–31, 1895, cat. 29, as Village de Sandviken (Temps de neige) or cat. 30, as Village de Sandviken.

Boston, Copley Society, Loan Collection of Paintings by Claude Monet and Eleven Sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Mar. 1905, cat. 90, as Village de Sandriken [sic], Pres [sic] Christiania, 1895, lent by Mrs. John Jay Borland.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of Chicago Collectors, Apr. 15–May 7, 1961, no cat. no.

Høvikodden, Norway, Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Impresjonismen 100 år, Nov. 1974–Jan. 1975, cat. 10 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Monet, Mar. 15–May 11, 1975, cat. 94 (ill.). (fig. 17.70)

Paris, Centre Culturel du Marais, Claude Monet au temps de Giverny, Apr. 6–July 17, 1983, cat. 30 (ill.).

Tokyo, Seibu Museum of Art, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago],Oct. 18–Dec. 17, 1985, cat. 60 (ill.); Fukuoka Art Museum, Jan. 5–Feb. 2, 1986; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Mar. 4–Apr. 13, 1986.

Nagaoka, Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Shikago bijutsukan ten: Kindai kaiga no 100-nen [Masterworks of modern art from the Art Institute of Chicago], Apr. 20–May 29, 1994, cat. 17 (ill.); Nagoya, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, June 10–July 24, 1994; Yokohama Museum of Art, Aug. 6–Sept. 25, 1994.

Art Institute of Chicago, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, July 22–Nov. 26, 1995, cat. 107 (ill.). (fig. 15.16)

Copenhagen, Ordrupgaard, Monet in Norway, Jan. 26–Apr. 8, 1996, no cat. no. (ill.).

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, Impressionism and the North: Late 19th Century French Avant-Garde Art and Art in the Nordic Countries, 1870–1920, Sept. 25, 2002–Jan. 19, 2003, cat. 149 (ill.); Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, Feb. 21–May 25, 2003.

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 84 (ill.).

Selected References

Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, Exposition de tableaux de Claude Monet, exh. cat. (E. Moreau, 1895), cat. 29 or cat. 30.

“Atelier Alfred Sisley,” La chronique des arts et de la curiosité, 19 (May 13, 1899), p. 172.

Copley Society, Boston, Loan Collection of Paintings by Claude Monet and Eleven Sculptures by August Rodin, exh. cat. (Copley Society, 1905), p. 27, cat. 90.

Oscar Reuterswärd, Monet: En konstnärshistorik (Bonniers, 1948), p. 207, fig. 97.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of Chicago Collectors, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), n. pag.

Karin Hellandsjø, ed., Monet i Norge/Monet in Norway; 1. Februar–1. April 1895, trans. C. Wood (Sonja Henies og Niels Onstads Stiftelse, 1974), p. 17 (ill.).

Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Impresjonismen 100 år, with a foreword by Ole Henrik Moe, exh. cat. (Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, 1974), front cover (ill.), p. 4, cat. 10.

Grace Seiberling, “The Evolution of an Impressionist,” in Paintings by Monet, ed. Susan Wise, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 35.

Susan Wise, ed., Paintings by Monet, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1975), p. 151, cat. 94.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 3, Peintures, 1887–1989 (Bibliothèque des Arts, 1979), pp. 184; 185, cat. 1397 (ill.); 282, letter 1276; 300, pièce justificative 131.

Joel Isaacson, Claude Monet: Observation and Reflection (Phaidon/Dutton, 1978), pp. 9; 42; 159, pl. 114; 224–25, no. 114.

J. Patrice Marandel, The Art Institute of Chicago: Favorite Impressionists Paintings (Crown, 1979), pp. 62–63 (ill.).

Jacqueline Guillaud and Maurice Guillaud, Claude Monet au temps de Giverny, exh. cat. (Centre Culturel du Marais, [1983]), pp. 110–12, fig. 60/cat. 30. Translated as Claude Monet at the Time of Giverny, exh. cat. (Centre Culturel du Marais, [1983]), pp. 110–12, fig. 60/cat. 30.

Art Institute of Chicago, Seibu Museum of Art, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, and Fukuoka Art Museum, eds., Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], trans. Akihiko Inoue, Hideo Namba, Heisaku Harada, and Yoko Maeda, exh. cat. (Nihon Nippon Television Network, 1985), pp. 120, cat. 60 (ill.); 121, cat. 60 (detail); 159, cat. 60 (ill.).

Charles F. Stuckey, ed., Monet: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin, 1985), p. 214, pl. 86.

Michael Howard, Monet (Brompton, 1989), pp. 119, 161 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 5, Supplément aux peintures: Dessins; Pastels; Index (Wildenstein Institute, 1991), pp. 50, 117.

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 124 (ill.).

Marianne Alphant, Claude Monet in Norway, trans. Maev de la Guardia (Hazan, 1994), pp. 39 (ill.), 42.

Art Institute of Chicago and Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Shikago bijutsukan ten: Kindai kaiga no 100-nen [Masterworks of modern art from the Art Institute of Chicago],exh. cat. (Asahi Shinbunsha, 1994), pp. 76–77, cat. 17 (ill.).

Edward Hirsch, “Illuminations: Four Writers Visit the Art Institute and Transform Paintings into Poetry and Prose,” Chicago Tribune Magazine, Sept. 25, 1994, p. 26 (ill.).

Russell Ash, ed., Impressionists’ Seasons (Pavillion, 1995), p. 79 (ill.).

Andrew Forge, Monet, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), pp. 49–50; 92, pl. 21.

Charles F. Stuckey, with the assistance of Sophia Shaw, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Thames & Hudson, 1995), pp. 128, cat. 107 (ill.); 227; 231; 237.

Sylvie Patin, “‘Some Absolutely Amazing Snow Effects, but Exceptionally Difficult to Capture,’” in Monet i Norge/Monet en Norvege/Monet in Norway, ed. Karin Hellandsjø, exh. cat. (Rogaland Kunstmuseum/Musée Rodin, 1995), pp. 76, 179 (ill.).

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet, or The Triumph of Impressionism, cat. rais., vol. 1 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 300 (ill.), 306.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue raisonné/Werkverzeichnis, vol. 3, Nos. 969–1595 (Taschen/Wildenstein Institute, 1996), pp. 578–80, cat. 1397 (ill.).

Ordrupgaard, Monet in Norway, trans. James Manley and Joan Fuglesang, exh. cat. (Ordrupgaard, 1996), p. 38 (ill.).

Paul Hayes Tucker, “A Frenchman in the Fjords: Monet’s Norwegian Campaign in 1895,” in Ordrupgaard, Monet in Norway, trans. James Manley and Joan Fuglesang, exh. cat. (Ordrupgaard, 1996), p. 29, n2.

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), p. 152 (ill.).

Norio Shimada and Keiko Sakagami, Kurōdo Mone meigashū: Hikari to kaze no kiseki [Claude Monet: 1881–1926], vol. 2 (Nihon Bijutsu Kyōiku Sentā, 2001), pp. 94, no. 222 (ill.); 190.

Karin Hellandsjø, “Monet and Norway,” in Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, and Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Impressionism and the North: Late 19th Century French Avant-Garde Art and the Art in the Nordic Countries, 1870–1920, ed. Torsten Gunnarsson and Per Hedström, exh. cat. (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, 2002), pp. 253, cat. 149 (ill.); 259.

James A. Ganz and Richard Kendall, The Unknown Monet: Pastels and Drawings (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Yale University Press, 2007), p. 167, fig. 146.

Joseph Baillio and Cora Michael, “Chronological and Pictorial Survey of The Life and Career of Claude Monet,” in Wildenstein and Co., Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 2007), p. 168.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 164 (detail); 165, cat. 84 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 164 (detail); 165, cat. 84 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel Paris 5186

Paris Stock Book 1891–1901

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel Paris 1341

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel New York 2391

New York Stock Book 1894–1905

Other Documents

Label (fig. 15.68)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten label

Content: 7129 Monet (fig. 15.46)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten label

Content: No 4 [?] Village de Sandviken / pres Christiania (fig. 17.73)

Inscription

Location: stretcher (written on paper strip, with other paper remnants on top)

Method: handwritten script

Content: Borland 5 [encircled] [. . .]19[. . .] (fig. 15.54)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 1961.790 (fig. 15.59)

Label

Location: frame

Method: printed label

Content: Arnold Wiggins & Sons / Limited / 4 Bury Street / St. James’s / London SW1 / Picture Frame Makers / Carvers and Gilders / [emblem at left] BY APPOINTMENT / TO H. M. QUEEN ELIZABETH II / PICTURE FRAME MAKERS / [emblem at right] BY APPOINTMENT / TO H. M. QUEEN ELIZABETH / THE QUEEN MOTHER / PICTURE FRAME MAKERS (fig. 15.60)

Label

Location: [glossary:backing board]

Method: printed label with typewritten script

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Claude Monet / title Sandvika Norway / medium cat # 13 / credit crate # 20 / acc. # 1961.790 (fig. 15.61)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script and green-ink inventory stamp

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U.S.A. / To Monet, Claude / Sandvika, Norway / 1961.790

Stamp: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 15.62)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: “Impressionismen og Norden” / 34 / Claude Monet / Sandviken, Norge / 73,4 × 92,5 cm / The Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 15.55)

Pre-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: Please fill in and stick on the back of picture. / Title. Sandviken, Norway / Name and address of owner. / Mrs. John Jay Borland / 2027 Prairie Ave / Chicago / Where to be sent for. / [blank] / Where to be returned to. / Dr. Brien [Pa . . . ? (or) Fa. . .?] / [. . .] Wabash Ave. Chicag[o] / [. . .] state as nearly as possible when the pictur[e . . .] (fig. 15.56)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: DURAND-RUEL / PARIS, 16, Rue Laffitte / NEW-YORK, 389, Fifth avenue / C. Monet No 5186[?] / Sandviken pres / Christiania / mosss. (fig. 15.57)

Post-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: green-ink stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 15.58)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label with green sticker

Content: [Logo] JAPAN / YAMATO TRANSPORT CO.,LTD. / FINE ARTS DIVISION / EXHIBT. JAPAN 94’ / シカゴ美術館展 [Shikago (Chicago) Bijutsukan ten] / CASE NO. 20 / CATAL. NO. [green sticker] 17 (fig. 15.63)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: The Art Institute of Chicago / “Claude Monet: 1840–1926” / July 14, 1995–November 26, 1995 / Catalog: 107 / Sandvika, Norway / Village de Sandviken sous la neige / The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Bruce Borland / (1961.790) (fig. 15.64)

Label

Location: frame

Method: printed label with handwritten script

Content: Arnold Wiggins & Sons / Treated for woodworm / Method: Thermo Lignum / Date: 29.2.08 (fig. 15.65)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75H (PECA 918 [glossary:UV]/IR interference cut filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and [glossary:cross-sectional analysis] using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/[glossary:UV fluorescence] and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: [glossary:darkfield], differential interference contrast ([glossary:DIC]), and UV. In situ photomicrographs with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

[glossary:Cross sections] analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VP-SEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state [glossary:BSE] detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation (EPIC) Center facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

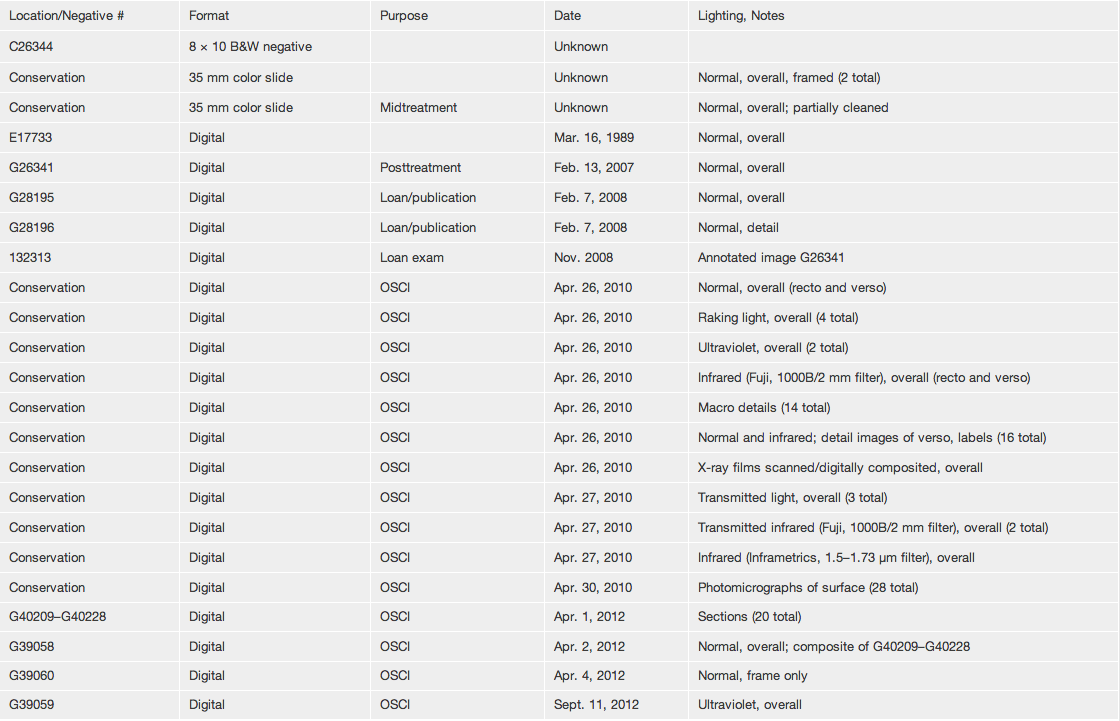

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 15.24).