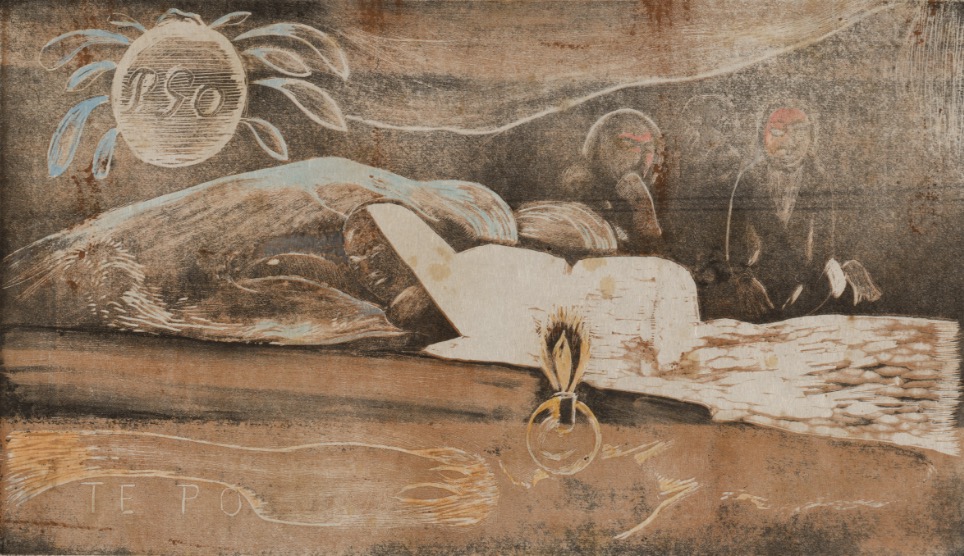

Cat. 52.1

Te po (The Night), from the Noa Noa Suite

1893/94

Third state of four

Wood-block print, printed twice in brown and black inks, with selective wiping, and hand-applied red, two tones of orange, yellow, two tones of blue, silver-gray, and black watercolor, on cream laid Japanese paper laid down on cream wove Japanese paper (a laminate made by the artist); 204 × 355 mm (image); 207 ×358 mm (sheets)

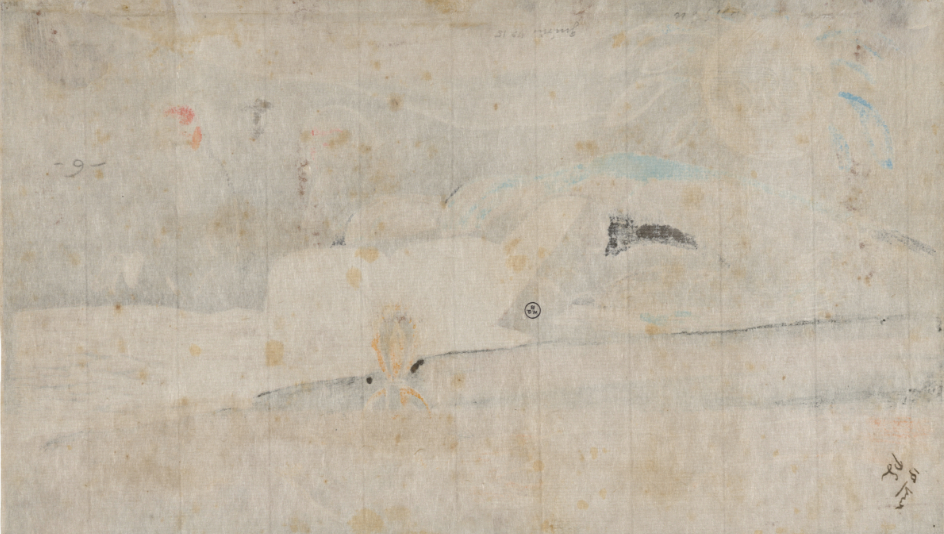

Inscribed in the artist’s hand verso, lower right, in pen and brownish-black ink: 10 Mars / PG [0 changed to 5 in the same ink; upside down]

The Art Institute of Chicago, Clarence Buckingham Collection, 1948.253

[glossary:Guérin] 15, [glossary:Kornfeld] 21 III/IV

For the verso, see fig. 1.10

Technical Study

Overview

One of the most inventive printing campaigns of the late nineteenth century, Gauguin’s Noa Noa Suite distinguishes itself as an enterprise in which the artist worked freely and experimentally with a wide range of papers, disparate media, and unconventional printing and transfer techniques to produce a multitude of impressions. Having purchased ten end-grain boxwood blocks of the highest quality, suitable for both wood engraving with a needle and wood carving with variously shaped gouges and knives, the artist printed all ten blocks as a group at several distinct moments in the block-carving process. He did so in a series of working campaigns in which he would print the blocks, then revise them, then print them again using different methods and materials in each campaign. These include applications of transparent watercolor washed over printed images; site-specific transfer of opaque, resinous, and waxy media from sheets of glass onto the paper before printing; and multiple, deliberately off-register printings in various inks on single sheets of paper. Close examination of a large number of examples has led to a chronology of print production that chronicles the artist’s more rudimentary printing methods as well as his unconventional printing techniques in which atypical materials were used at different moments in the evolution of the suite.

This hand-colored, third-state impression of Te po (The Night) is among a number that were printed in a later phase of the carving and compositional development of the block in which the artist adhered two sheets of absorbent [glossary:Japanese paper] together to obtain a surface that accommodated applications of transparent watercolor brushed over printing ink. It is very similar in palette and execution to impressions of Noa Noa (Fragrant) (cat. 51.2), L’univers est créé (The Universe Is Being Created) (cat. 54.2), and Maruru (Offerings of Gratitude) (cat. 55.2) in the Art Institute’s collection.

Overall, the hand-colored impressions have a more luminous quality, which is enhanced by the translucency of the Japanese papers. It is this very quality that likely appealed to Gauguin when working with delicate washes of color. The end results are certainly aesthetically quite different from other impressions in which transferred opaque media predominate. By comparison, impressions colored by the transfer of waxy, resinous media were printed on much sturdier papers.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 1.1).

Media

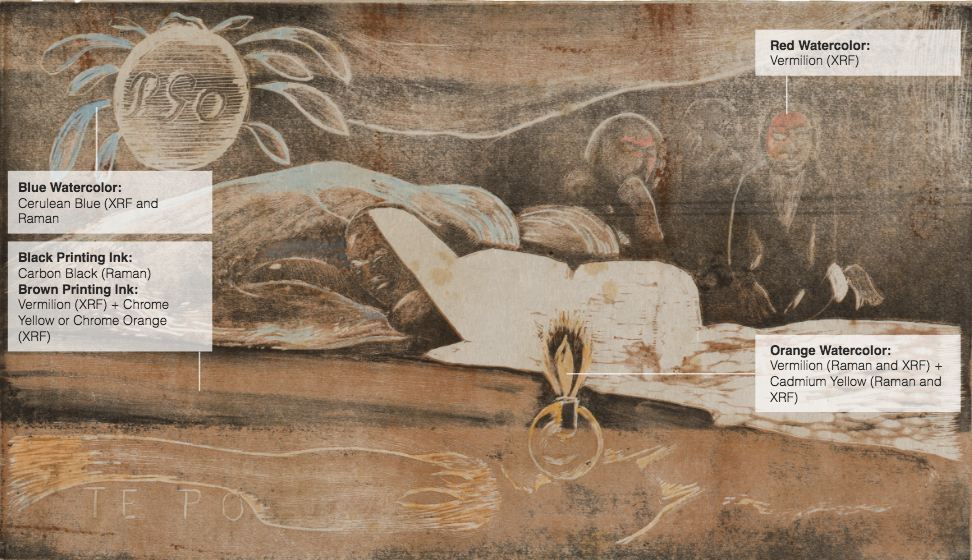

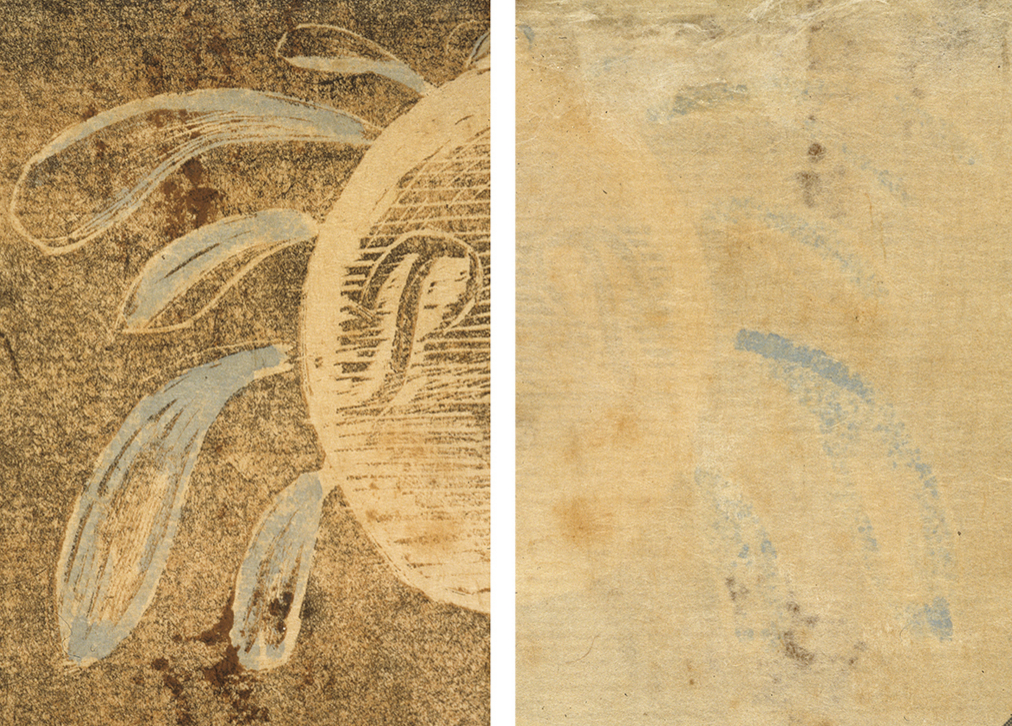

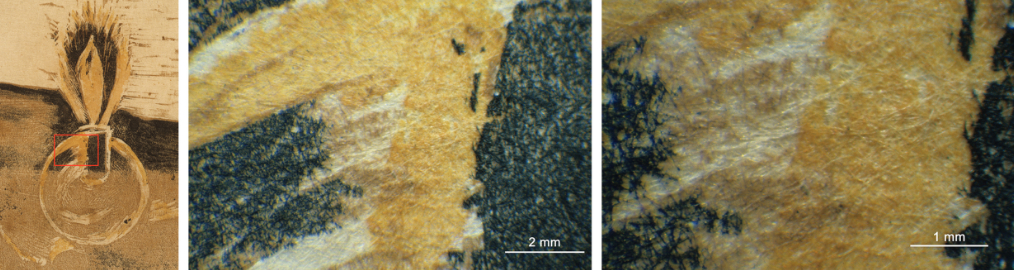

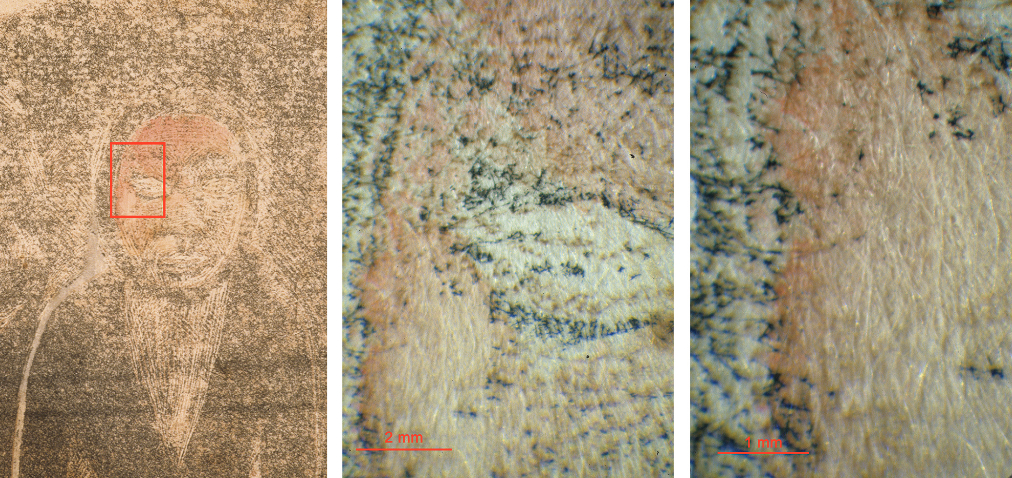

For this print, the wood block was printed twice, first in brown ink and then in black ink. Gauguin then selectively wiped the black ink from the block so that, when printed over the brown ink layer, much of that tone would be visible. The carbon black ink was applied over brown ink that is a mixture of carbon black, vermilion, and chrome yellow or chrome orange. Once satisfied with his printed impression of Te po, Gauguin returned to it with brush in hand to add color. Red, two tones of orange, yellow, two tones of blue, silver-gray, and black watercolor were applied over the off-register double printing of the brown and black inks (fig. 1.2). The aqueous medium was readily absorbed into the Japanese paper and bled through to the verso. Examination of the verso reveals that more vibrant colors were initially used and have faded with overexposure to light (fig. 1.3). Passages of red and orange were especially affected. In the foreground, a spirit-like form extends horizontally into the composition from the left. It was hand colored with a bright orange composed of vermilion and cadmium yellow that has dulled in appearance with fading. The devil-like shadow to its right has additions of golden yellow. [glossary:XRF] and [glossary:Raman microspectroscopy] confirm that these golden yellow washes contain degraded cadmium yellow pigment that was originally bright yellow instead of the more gold-to-brown tone that exists in this impression, as well as others from the Noa Noa Suite, today. The oil lamp was toned with a second orange and more of the same golden cadmium yellow (fig. 1.4). The blanket that envelops the central figure was once washed with what might have been a pale-orange or pink tone. A silver-gray wash was used below and to the left of the figure’s extended right arm. A more intense application of the same silver-gray was added above her arm; on the verso this same passage is more intensely black (fig. 1.5). To her left, cerulean-blue washes were added to the rolling forms around and above her. The silver-gray appears again to the far left and in the rolling form in the middle ground. Among the three looming figures to the right, vermilion red washes appear in those at left and right, while the central figure is toned with gray (fig. 1.6).

Support

Gauguin adhered two sheets of thin, cream Japanese paper to each other to make a [glossary:laminate]. By laminating two sheets of Japanese paper together, he strengthened the support for printing and for applications of watercolor washes. A thinner [glossary:wove] paper layer lies beneath a slightly heavier [glossary:laid] paper layer. The paper fibers are distributed evenly and the paper is of a uniform color. In transmitted light the two sheets of Japanese paper, one laid and the other wove, can be seen more readily. The edges of the sheet are straight cut, although slightly irregular. The paper has been trimmed close to the printed image. Approximately 1–2 mm of paper margin remains around the image on all sides.

Gauguin selected fibrous, cream-toned Japanese papers for this and a number of other hand-colored impressions but not without modifying the papers in some way. Often Gauguin would laminate two distinctly different Japanese papers together, one with a laid pattern from the shu (mold) and the other wove, as in Maruru (cat. 55.2) and L’univers est créé (cat. 54.2). Fine vertical creases are visible in all of the laminated sheets examined for this study. The creases formed as a result of sheet expansion and manipulation as the artist brush applied a dilute, water-soluble adhesive (perhaps starch-based) onto the sheets to adhere them to each other. Where Gauguin applied pressure to the papers with the brush to assure adhesion between them, he pulled and distorted the long paper fibers. On the verso of this print, fiber disruption and brush marks resulting from the lamination process are visible in [glossary:raking light], as are the series of creases described above (fig. 1.10).

The chain line interval found in the laid paper top sheet is 35 mm wide with one irregular interval of 32 mm in the center of the sheet. Two additional hand-colored impressions created on laminated sheets are in the Art Institute’s collection. In these impressions, Maruru (cat. 55.2) and L’univers est créé (cat. 54.2), the laid paper is pasted beneath the wove paper; however, the overall visual effect remains the same. The chain line intervals in Maruru and L’univers est créé are identical to those in Te po—all are 35 mm wide, with the exception of one on the right side of the sheet that is 32 mm wide. Visually, the papers are all nearly identical to each other when weight, color, and surface texture are compared. In Te po, the wove paper used as the underlying sheet is of a lighter weight and tone than the wove paper used in these other impressions.

Dimensions

204 × 355 mm (image); 207 × 358 mm (sheets)

Compositional Development

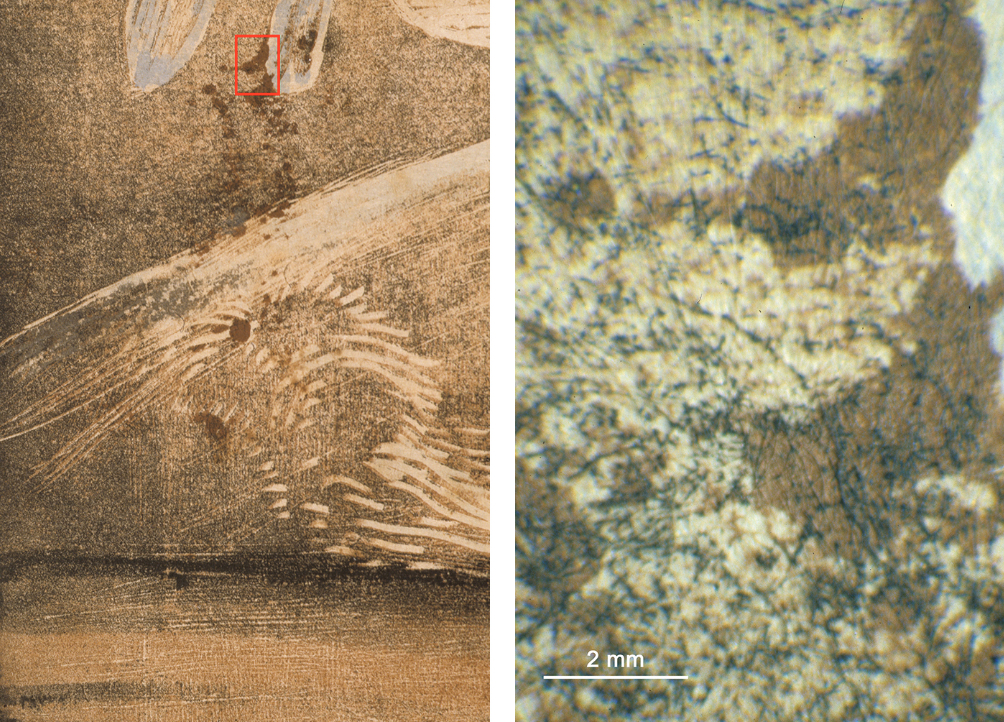

Gauguin created this impression of Te po in several steps. First, he inked the wood block in brown. The first layer of ink was thinly applied overall. Pools of brown ink present on the paper are not the result of deliberate wiping or a transfer process but of an initial uneven distribution of printing ink onto the surface of the [glossary:roller]. This caused irregular striations of brown printing ink to appear on the block as ink was rolled out onto it from the roller, repeated at four-inch intervals across the length of the sheet (fig. 1.7). The artist made a second pass with the roller across the bottom half of the block and after printing, the bottom half of the impression appears darker and there is more ink present than in the upper half.

Gauguin then inked the block in black using lesser amounts of ink and selectively wiped away some of the black ink. As a result, the brown underlayer of ink predominates in the foreground, although Gauguin did go back with brush and black watercolor to reinforce a single line between foreground and middle ground. Two distinct horizontal black lines intersect the three figures on the right (fig. 1.8). These lines may be intentional, but it is more likely that in applying differential pressure to the tool used to facilitate the transfer of ink, this particular back-and-forth stroke resulted in the transfer of more ink than the artist intended.

Gauguin’s choice of a fibrous ivory-toned Japanese paper to print this impression of Te po was quite intentional; he knew that the fibrous paper was absorbent and would readily accept the watercolor medium. Against the light paper tone the colors would have appeared quite vibrant. Over time, with exposure to light, the watercolor passages on the front of the print have faded significantly. The vibrancy of the colors selected by the artist is still evident on the verso, where the watercolor remains less faded in some areas and totally unfaded in others.

Conservation Examination and Treatment History

The hand-colored print was conserved in anticipation of this publication. When discoloration was removed from the sheet, its tone brightened significantly and the colors now appear more vibrant, as Gauguin would have intended. Comparison with watercolor passages in pristine impressions from the Noa Noa Suite (see, for example, Auti te pape [Women at the River] [cat. 59.2]), and especially within the pages of Gauguin’s Noa Noa, Voyage de Tahiti, reveals an intensely bright and colorful palette on papers with an ivory hue rather than a golden tone (fig. 1.9).

Condition Summary

The thin, supple, laminated sheet displayed significant undulation throughout, especially vertically through the center. There are several pronounced creases that probably formed during printing. These include a strong vertical crease that runs from the top to the bottom of the sheet, 78 mm in from the left edge; a second strong vertical crease that runs from the bottom of the sheet through the center and then meanders to the left and right; and a third, very hard diagonal crease that appears to the right of center and measures 90 mm. The remaining fine vertical creases throughout are a result of sheet expansion and manipulation during the lamination process and probably formed when Gauguin brushed his water-soluble adhesive onto the papers to adhere the two sheets together. Using a coarse brush to apply pressure to assure adhesion, he disrupted the long, delicate Japanese paper fibers on the verso, as is readily visible in raking light.

Before conservation treatment, there were numerous dark-brown stains, especially in the reclining figure, that were very pronounced. There was also extensive [glossary:foxing] that was quite dark. The staining and foxing were much more evident in the margins and on the verso where printing inks did not obscure them. Under ultraviolet light the stains remain visible and fluoresce golden brown; white halos around them are indicative of oil (see fig. 1.1). It is quite likely that the staining occurred well after Gauguin printed this impression, since darkening of oil in this manner occurs over time. Staining from foxing fluoresces to a much lesser degree. At some point in the past the sheet was water damaged, as evidence by a pronounced tide line in the lower left that is much more visible on the back than it is on the front of the sheet. Under ultraviolet light, tide lines from water staining are very pronounced.

Harriet K. Stratis with the assistance of Mary Broadway

Provenance

From the artist to Francisco “Paco” Durrio (1868–1940), Paris, between 1893 and 1895.

Left by Francisco “Paco” Durrio at Kunsthalle Basel for exhibition in 1928.

Walther Geiser (1897–1993), Basel, by Jan. 18, 1931.

Consigned by Walther Geiser to Lucas Lichtenhan (1897–1969), Basel, on Jan. 18, 1931.

Returned by Lucas Lichtenhan to Walther Geiser in 1936.

Sold by Walther Geiser to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1948.

Exhibition History

Paris, Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, Salon d’automne: 4me exposition, 1906, cat. 141.

Association Paris–Amerique Latine, Exposition rétrospective: Hommage au génial artiste franco-péruvien Gauguin, Dec. 17, 1926, cat. 44.

Musée du Luxembourg, Gauguin: Sculpteur et graveur, Jan.–Feb. 1928, cat. 57.

Kunsthalle Basel, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, July–Sept. 9, 1928, cat. 111 and cat. 221.

Berlin, Galerien Thannhauser, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, Oct. 1928, cat. 197.

London, Leicester Galleries, Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Durrio Collection of Works by Paul Gauguin, May–June 1931, cat. 4.

New York, Bignou Gallery, Gauguin: First Trip to Tahiti, Jan. 3–14, 1939, cat. 3.

New York, Wildenstein & Co., Gauguin: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York City, Inc., Apr. 5–May 5, 1956, cat. 78.

Art Institute of Chicago, Gauguin: Paintings, Drawings, Prints, Sculpture, Feb. 12–Mar. 29, 1959, cat. 141; New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Apr. 21–May 31, 1959.

Munich, Haus der Kunst, Paul Gauguin, Apr. 1–May 29, 1960, cat. 173, pl. 84.

Vienna, Österreichische Galerie im Oberen Belvedere, Paul Gauguin, June 7–July 31, 1960, cat. 87.

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, The Art of Paul Gauguin, May 1–July 31, 1988, cat. 168 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Sept. 17–Dec. 11, 1988; Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, as Gauguin, Jan. 10–Apr. 20, 1989 (Washington, D.C., and Chicago only).

Selected References

Société du Salon d’Automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif, exh. cat. (Compagnie Française des Papiers-Monnaie, 1906), cat. 141.

Association Paris–Amerique Latine, Exposition rétrospective: Hommage au génial artiste franco-péruvien Gauguin, with introductions by F. Cossio del Pomar and G. Daniel de Monfreid, exh. cat. (n.p., 1926), cat. 44.

Marcel Guérin, L’oeuvre gravé de Gauguin (H. Floury, 1927; Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1980), cat. 15 (ill.).

Musée du Luxembourg, Gauguin: Sculpteur et graveur, exh. cat. (Musée du Luxembourg, 1928), p. 11, cat. 57.

Kunsthalle Basel, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, exh. cat. (Kunsthalle Basel, 1928), p. 25, cat. 111.

Kunsthalle Basel, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, exh. cat., 2nd ed. (Kunsthalle Basel, 1928), p. 30, cat. 221.

Galerien Thannhauser, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, introduction by W. Barth, exh. cat. (Galerien Thannhauser, 1928), p. 15, cat. 197.

Leicester Galleries, Catalogue of an Exhibition of the Durrio Collection of Works by Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Ernest Brown & Phillips, 1931), p. 5, cat. 4.

Bignou Gallery, Gauguin: First Trip to Tahiti, foreword by Carl O. Schniewind, exh. cat. (Bignou Gallery, 1939), n.pag., cat. 3.

Carl O. Schniewind, “Paul Gauguin,” special issue, Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 43, no. 3 (Sept. 1949), p. 49 (ill.).

Robert Goldwater and Carl O. Schniewind, Gauguin: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York City, Inc., exh. cat. (Wildenstein & Co., 1956), p. 22, cat. 78.

Art Institute of Chicago and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gauguin: Paintings, Drawings, Prints, Sculpture, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1959), p. 81, cat. 141.

Haus der Kunst, Paul Gauguin, with essays by Germain Bazin and Harold Joachim, exh. cat. (Ausstellungsleitung München e.V. Haus der Kunst, 1960), p. 31, cat. 173, pl. 84

Oberes Belvedere, Paul Gauguin, 1848–1903, exh. cat. (Österreichische Galerie im Oberen Belvedere, 1960), p. 45, cat. 87, pl. 32.

Alfred Langer, Paul Gauguin (VEB E.A. Seemann, Buch- und Kunstverlag, 1965), pp. 58, 60, 87, pl. 20.

Richard R. Brettell, Françoise Cachin, Claire Frèches-Thory, and Charles F. Stuckey, The Art of Paul Gauguin, with assistance from Peter Zegers, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C./Art Institute of Chicago/New York Graphic Society Books, 1988), p. 81, cat. 141.

Paul Gauguin, Noa Noa, transcription, ed. Pierre Petit, commentary by Bronwen Nicholson (J.-J. Pauvert, 1988), p. 135–36 (ill.).

Elizabeth Mongan, Eberhard W. Kornfeld, and Harold Joachim, Paul Gauguin: Catalogue Raisonné of His Prints, with assistance of Christine E. Stauffer (Galerie Kornfeld, 1988), pp. 104–05, cat. 21 (ill.).

Adam Biro, Gauguin: La bibliothèque des expositions (A. Biro, 1988), p. 66, fig. 40e.

Anna Maria Damigella, Paul Gauguin: La vita e l’opera (Mondadori, 1997), p. 188 (ill.).

Javier González de Durana, Miriam Alzuri, and María Amezaga, Francisco Durrio (1868–1940): Sobre las huellas de Gauguin, exh. cat. (Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, 2013), p. 220, no. 11.

Other Documentation

Inscriptions and Distinguishing Marks

Recto

Inscribed in wood block, lower left, printed in [glossary:white-line manner]: TE PO

Signed in wood block, upper left, in black printing ink: PGO

Verso

Inscribed upper right, upside down in graphite: Guerin No. 15

Inscribed upper right, in graphite: No. 5160

Inscribed upper left, upside down in graphite: – 6 –

Collector’s stamp center, encircled and upside down in black ink: W.G.B

Inscribed in the artist’s hand, lower right, in pen and brownish-black ink: 10 Mars / PG [0 changed to 5 in the same ink; upside down]

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

The media and their application, as well as the condition of the artwork, were assessed through visual examination using normal, transmitted, and raking light; microscope magnification (8–10×), and ultraviolet-light examination (254 and 365 nm). The pigments in the printing inks and watercolors were identified by [glossary:XRF] and [glossary:Raman microspectroscopy].