James Ensor: The Temptation of Saint Anthony

Ensor’s Panache:

Army and Empire in “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” and in Belgium, 1887

Debora Silverman

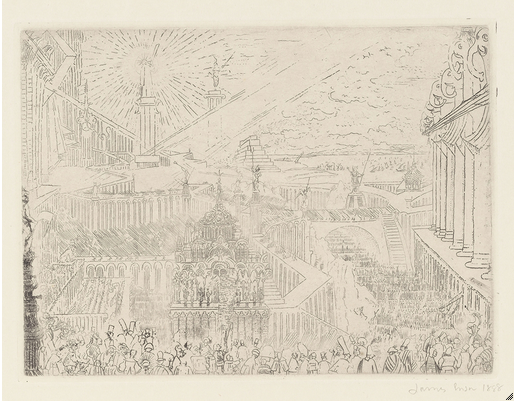

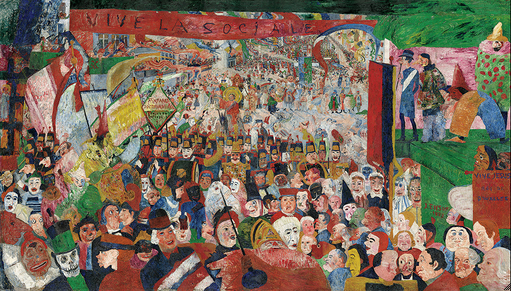

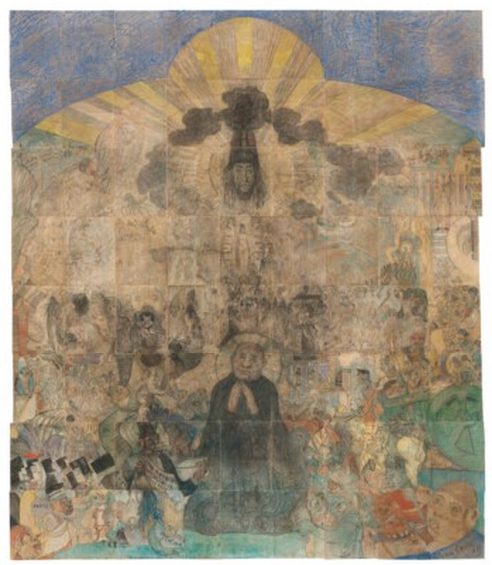

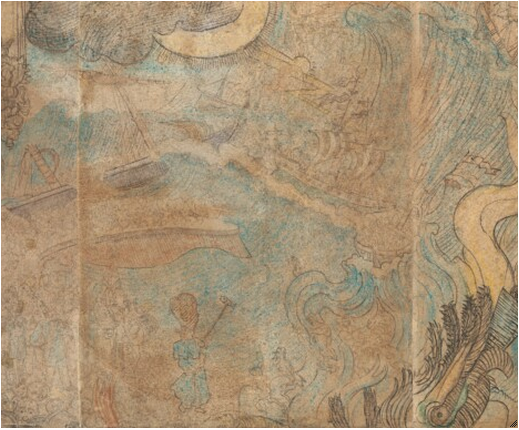

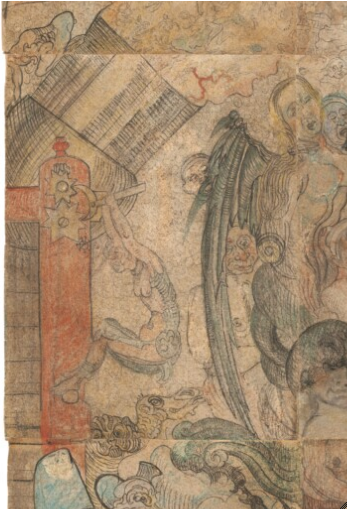

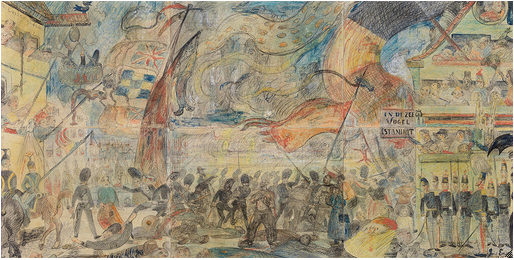

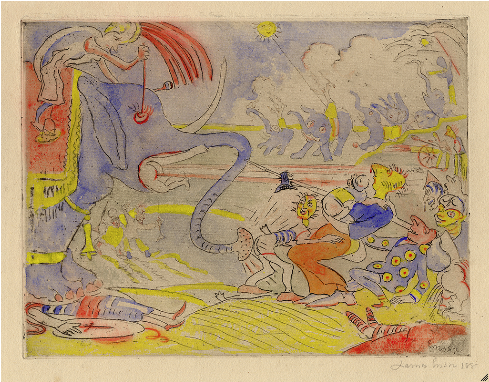

Like a modern Pandora’s box, James Ensor’s Temptation of Saint Anthony releases a torrent of psychological pressures and historical materials (fig. 7). Now, as then, the giant mural drawing challenges viewers with its disruptions of legibility, goading us to seek coherence amid the seemingly chaotic mix. Divergent scales and spaces collide; wildly varied stylistic techniques compete to lure the viewer. Ensor brings together dissonant themes and motifs: the comic and the demonic, sorrow and horror, the carnivalesque and carnage.

Like a modern Pandora’s box, James Ensor’s Temptation of Saint Anthony releases a torrent of psychological pressures and historical materials (fig. 7). Now, as then, the giant mural drawing challenges viewers with its disruptions of legibility, goading us to seek coherence amid the seemingly chaotic mix. Divergent scales and spaces collide; wildly varied stylistic techniques compete to lure the viewer. Ensor brings together dissonant themes and motifs: the comic and the demonic, sorrow and horror, the carnivalesque and carnage.

The fifty-one sheets that Ensor joined to make The Temptation cohered in part as the artist’s vehement riposte to Georges Seurat’s success with A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884, shown in 1887 at the annual exhibition of Les XX (Les Vingt; 1883–93), the Brussels artists’ collective of which Ensor was part.93 As one of the leaders of the group, Ensor felt blindsided by the Seurat sweep; just at the cusp of his own success, he was abruptly eclipsed. The Temptation forms a vigorous counteroffensive against pointillism and its seamless accord of individual microdots in a composite whole. Ensor’s individual sheets blend and meld, but they also emphatically show their seams, and the spectacle of humanity they present is not Seurat’s static frieze of utopian harmony but an expressive cacophony of aggression, possibility, and grief.

Explicit evidence indicates that an 1874 text by Gustave Flaubert, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, partly inspired Ensor’s drawing.94 Flaubert’s text is a dialogue and a journey, imagining Saint Anthony’s discussions and temptations through time and space with characters ranging from the Buddha to the Queen of Sheba. In the last scene Saint Anthony, lying on the ground, experiences an epiphany about the unity and continuity of all matter, as “day is dawning, . . . golden clouds” unfurl across the sky, and “the face of Jesus Christ” appears, radiant, “inside the very disc of the sun.”95

The vision of the radiant face of Christ in dawning golden skies indeed evokes Ensor’s drawing and has been connected to it.96 But there are striking, and significant, differences from Flaubert’s upbeat ending. Ensor’s corpulent saint—imagined as a kind of Buddha meets Friar Tuck—kneels, prays, and weeps below the impassive but tearful face of Christ, whose hair and elaborate headdress extend beyond the solar disc. Flaubert’s evocation of a face as generalized radiance is here particularized, less resplendent, and still set in gloom: rather than dissipate to reveal Christ, dark clouds surround him. Most importantly, while Flaubert’s Saint Anthony gains comfort from the presence of Christ and endures, Ensor’s mourns his ordeals. Christ above cries with him, intensifying his lamentation.

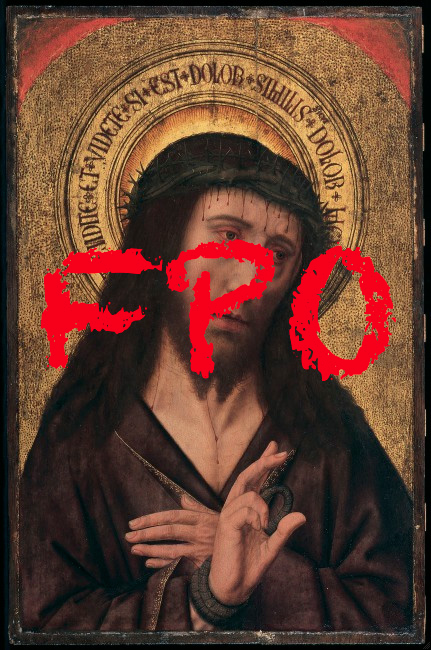

Ensor modeled his head of a tormented Christ on a painting by the early Flemish master Albert Bouts (fig. 25).97 This was an act of cultural reclamation: like many of his avant-garde contemporaries, Ensor used sources from the Flemish past as building blocks for a new, modern Belgian tradition.98 But sometime before he completed his large-scale drawing, Ensor replaced the crown of thorns with a tall, red-feathered army helmet. By doing so, he shifted his sights from cultural reclamation to political provocation, as he now drew attention to a problem of vital significance in Belgium during the very decade of the drawing’s evolution: the role and function of the country’s army. This article identifies specific forms, figures, and themes in The Temptation that show Ensor’s engagement with two central issues in Belgium in 1877–87: the crisis of the army at home; and expansionism in Africa.

My study of Ensor’s Temptation began and unfolded from a two-step process: observing motifs and figures in front of the actual drawing, remarkably restored by Kimberly J. Nichols of the Art Institute of Chicago, and returning to discrete areas with the magic of the zoom function and other tools of the online research platform.99 The zoom function accords extremely well with Ensor’s wildly varied scale and spaces, and is especially useful for close looking at areas with active, tiny figures; I ask readers to use it as they read, just as I did as I wrote.100 Clues, patterns, and visual shorthand fill even small sections of the drawing with larger historical meaning and resonance; the zoom function reveals the cultural logic animating some of the visual scramble.101 It also facilitates an uncanny meeting of optics across time: this new technology allows us to partially recreate the perceptual habits Ensor cultivated by looking at items under the microscope, which he did with his close friend the mycologist Mariette Rousseau.102

Ensor’s Shakoed Christ, Belgian Neutrality, and the Military Crisis of the 1880s

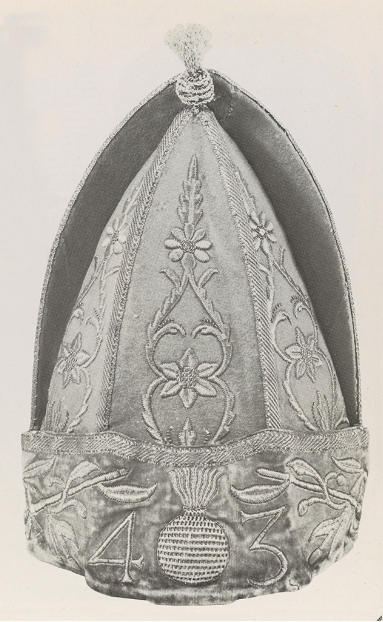

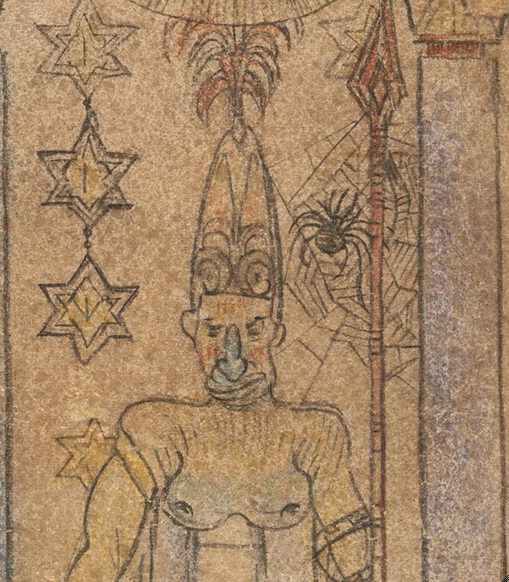

The most arresting element of Ensor’s drawing is the floating head of Christ, centered above Saint Anthony, in sheets 2D/E, 2F/G, and 3D–F (fig. 22). As mentioned previously, Ensor replaced the spiky crown of thorns with the tall, red-feathered army helmet known as the shako. A V-shaped site for a mount on the top of the hat holds the feather, plumes splayed, suggesting a ludicrous theatricality. Curiously missing from the military helmet are the brass or metal plaques that typically identify the unit, regiment, or company. Ensor left this space above the brim empty, and he also omitted the icon seen on army headgear of this type since the birth of the nation in 1830: the rampant lion, the symbol of Belgium (fig. 18). The placement of Ensor’s “Man of Sorrows” is similarly strange. Usually, the heavenly canopy hosts Christ as king, in majesty, or, as Ensor’s contemporary Ary Scheffer presented him, as Christus Consolator (fig. 13).103 But Ensor instead depicts an injured, bleeding, and teary Christ, implying that suffering is ascendant and eternal.

Why the tall red-feathered shako? And why at this moment? It is a very particular type of army helmet in a very particular context, and Ensor’s choices are neither casual nor incidental. Made during a period of divisive national controversy about the army in Belgium, and completed the same year the crisis ended in defeat for the reformers, The Temptation shows how debates and conflicts over the reorganization of the military infiltrated Ensor’s social circles and creative consciousness. By planting a military helmet on Christ’s head, Ensor alighted on a conspicuous symbol of the army’s sorry state. In a vexed condition since independence, the Belgian army had been disabled from the outset by the requirement of neutrality. By the 1870s, the dilemmas facing this neutral army prompted a campaign for reform that dominated public discussion in 1886–87 just as much as the labor uprisings and social unrest that have received the bulk of scholarly attention.104

After an improbable victory against the Dutch army by civilian militias in 1830, the new nation of Belgium was crafted by the Great Powers, who set its borders, chose its ruler, and imposed a state of neutrality on the young country, relegating it to perpetual dependence on outsiders for its territorial integrity. King Leopold I, a distinguished soldier and decorated war hero who fought against Napoleon, consolidated the new army along these terms, which were so restrictive that even simulated battles and training maneuvers had to be observed by international monitors. This neutral army was defined by four features, unique in Europe, that persisted throughout the period Ensor made The Temptation: an officer corps dedicated to defensive strategy, a non-conscription rank and file, a civic guard of “Sunday soldiers,” and a limited constitutional monarch deemed commander-in-chief but unable to command (he was beholden to Parliament for military funding and organization). Service in the army was, until 1909, nonobligatory and it worked by the remplacement (substitution or preemption) system, which meant that only the very poor had no option but to enlist.105

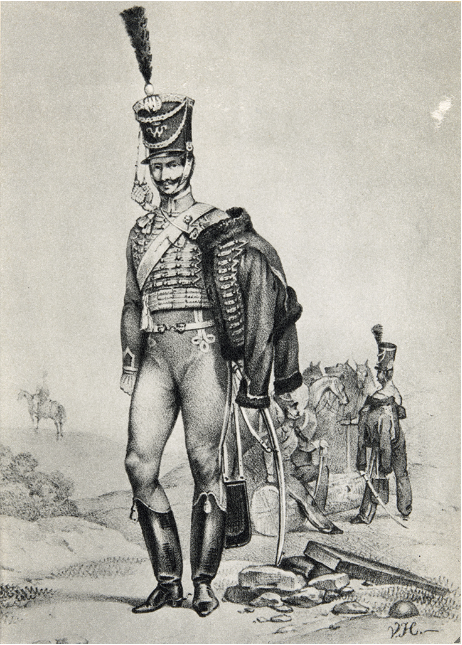

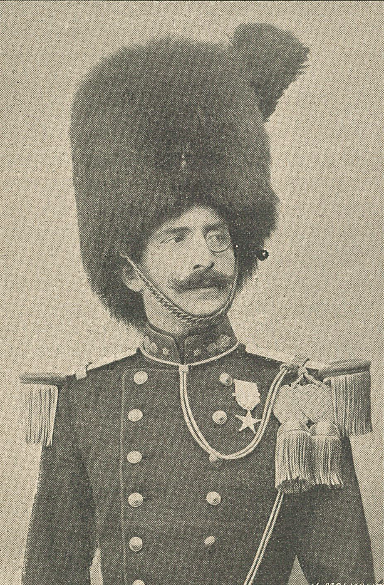

Leopold’s reign also saw the systematization of uniforms. The tall shako, which adapted the type worn by Belgian dragoons, hussars, and artillery at Waterloo, was used through 1862 (fig. 26); shako plaques, buttons, epaulettes, braiding, cords, and colors were stipulated and standardized for each grade and rank. The red shako with white, red, or black flamme, or feather, was assigned after 1830 to officers in the chasseurs à cheval or light cavalry (fig. 10); the shapska for the lancers (fig. 9); and the bearskin for the grenadiers (fig. 12). Feathers, whether ostrich, rooster, or vulture, were draped or planted upright and called the panache. The erect feather mount was the sign of the highest commanding officer; the rest cascaded (fig. 27).106

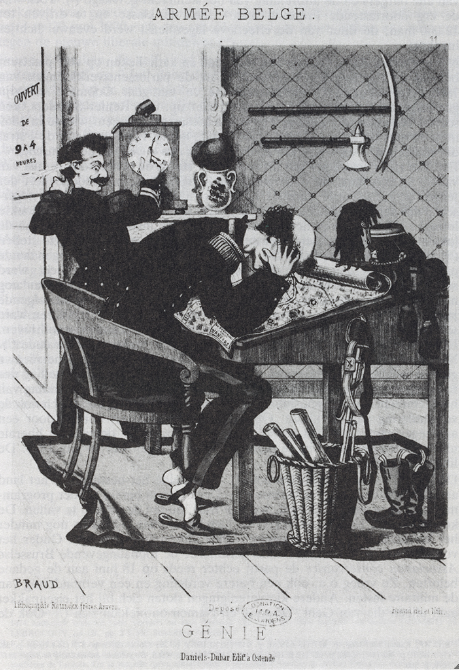

Under Leopold I, the army secured an honorable position in the new nation and won praise across Europe. But a number of changes after 1865, during the reign of his son, King Leopold II, made the army the center of controversy. The crisis culminated in 1887, when Ensor depicted his tearful Christ in a shako. In the years following the Franco-Prussian War, fearful of German military prowess, Belgian campaigners called on Parliament for wide-ranging changes. A brief look at the key elements of the platform and their presentation in the press suggests the distinctive and historically specific associations of Ensor’s Christ. They reveal the pressure points of a Belgian national culture beset in 1877–87 by dilemmas of militancy, masculinity, sacrifice, and injustice, which rippled through Ensor's social circles and inner world as well. These derived from the deep structural problems of the anomalous Belgian army: an elite, well-trained officer corps languishing without a mission and subject to ridicule, a civic guard of “operetta soldiers” who dabbled in war as musical theater, and “an army of the poor” composed of uneducated and mistreated conscripts.107

Professors of a modernized military curriculum included Ensor’s surrogate father, Ernest Rousseau, who taught applied physics at the École Militaire, and Lieutenant General Gérard Leman, whom Ensor met at the Rousseaus’ home, and who added new engineering sciences, cartography, and advanced mathematics to the curriculum.108 But once the officers graduated, morale quickly deteriorated; they faced low pay, slow promotion, threadbare uniforms, and terrible barracks conditions.109 Officers lived apart from the troops and frequented hotels and restaurants. They passed off some of their duties of discipline and drilling to the sous-offs, or junior officers. Army reformers and other contemporary critics emphasized that this system bred an unstable mix of apathy and contempt: they noted the tendencies to “tyranny,” harsh punishment, and even excess cruelty to the recruits, powerless and easy targets.110

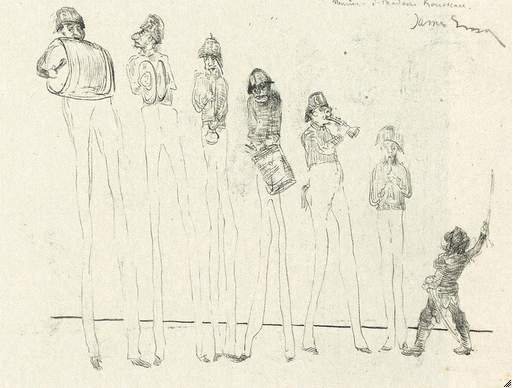

The officers did, however, dedicate inordinate amounts of time and effort to cultivating their role as performers in an army “made to go on parade”—a paradox at the heart of the neutral army in Ensor’s world. Belgian public life frequently featured the military’s marching bands and processions; numerous festive, civic, religious, and national occasions drew crowds to the flourish of visual and musical fanfares of the regiments.111 The drum major leader of the bands usually sported a tall upright feather on a bearskin or grenadier hat much like that on the shako of Ensor’s Christ. By the 1880s a venerable tradition of army musical skill thrived in Belgium (fig. 28).112 Whereas before independence the drums and trumpets advanced and roused troops to action on the battlefield, in Ensor’s world they occupied pride of place in a battle of the bands (fig. 19 and fig. 17).

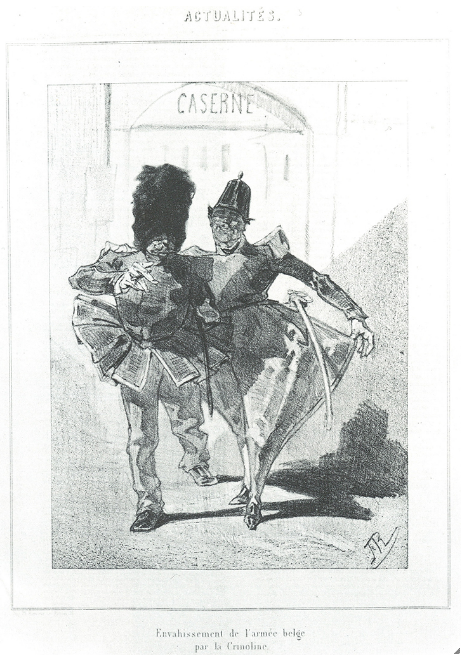

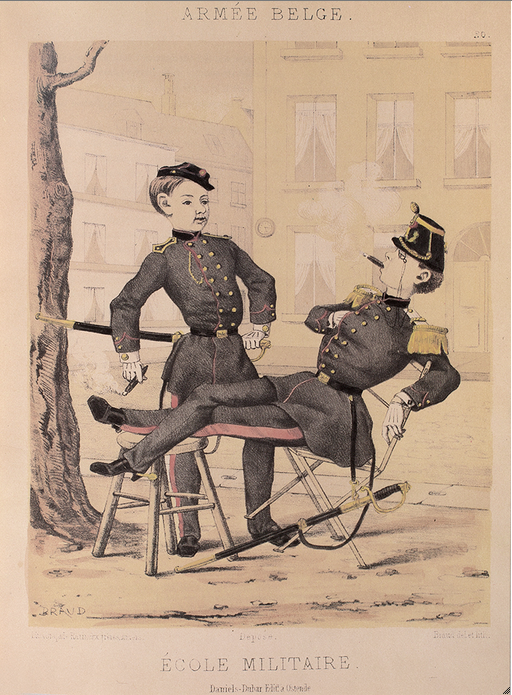

Artists and army reformers alike lampooned the overattention to preening and appearances, raising concerns about a more serious problem: the decline of martial spirit and the advent of a so-called effeminate military. Ensor’s friend and mentor artist Félicien Rops made a caricature in 1856 of two prancing officers called The Invasion of the Belgian Army by Crinoline (fig. 29). The high waist and ample skirt of this feminizing fashion plate did derive from some features of the officers’ uniforms, which continued into the 1900s to consist of an overcoat “tightened at the waist by a belt,” thus “giving the impression of being rather delicate” (fig. 30).113 Another print by Ensor’s Ostend teacher, Dubar, from the series Armée belge, shows students at the École Militaire in the tight, high-waisted, short-skirted uniforms worn by officer cadets, with one lounging, with delicate waist, feet, and hands like a woman’s (fig. 31). These representations had corrosive effects on the army’s reputation and morale. The diaries of Captain Charles Lemaire, a talented but disillusioned graduate of the École Militaire, record the army’s state of “moral torpor” and the public’s low esteem for both the institution and its officers, derided as “old women, saber-rattlers, coffee-house heroes, and leathernecks.”114

Moreover, decorative and dishonored officers competed in public life with a rival organization that spurred Ensor’s satirical imagination: the civic guard. These local citizens’ militias, descended from medieval associations, became in the new Belgium weekly clubs for target practice and socializing. They were composed of those sufficiently well-off to buy their own uniforms and rifles; they elected their own leaders from the community (fig. 32). Military reformers derided the guards as untrained hobbyists who were better equipped than the army itself.115 Ensor and others found them ridiculous. Cartoons and caricatures of the period show the typical civil guard leader as a full-bellied poor shot who landed in the pub buying beer for all at the end of the exercises (fig. 33). Ensor’s large colored drawing The Strike (The Slaughter of the Ostend Fisherman [August 1887]) (fig. 34) evokes this type exactly: as a violent battle rages with army grenadiers and lancers attacking civilians in the center of the composition, a group of civic guardsmen stands around fatuously on the right. A dog on a leash; a commander at attention shown in profile; and a woman cut off at the far corner recall the corner group with the leashed monkey in Seurat’s Grande Jatte. Here Ensor reverses the fashionable Parisian woman’s lavish bustle and turns it into the swollen belly of the officer in profile, whose flamboyant helmet and corpulence are the telltale signs of a dress-up soldier with deep pockets.

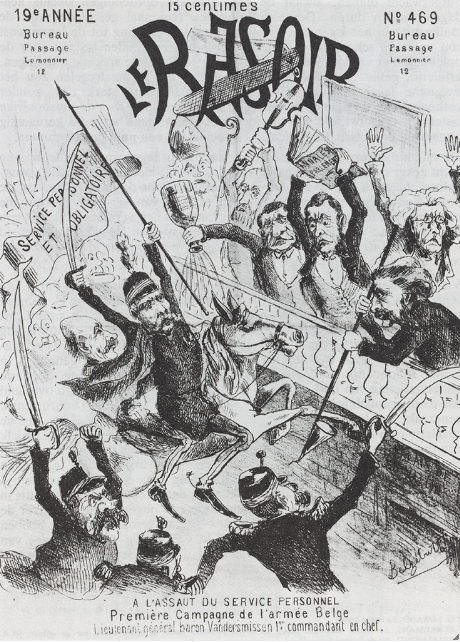

Already, however, popular uprisings in 1886 had forced the drafting of a Parliamentary bill for military reform in 1887, with key provisions including universal obligatory service and expanding army funding. Despite intense lobbying by King Leopold himself, the bill was narrowly defeated.116 This prompted further mockery of the already embattled military brass. One cartoon showed the aging General Vandersmissen charging the halls of Parliament on his horse, sword and banner flashing. Parliamentarians at the ramparts are seen drenching him with water and throwing the book of procedures and minutes at him; one is about to smash down a violin near him as well. Like Ensor’s Christ, the general wears the shako with the commander’s upright feather (fig. 20).

A Modern Crown of Thorns

The head of a tearful and wounded Christ in a feathered shako thus provided a dramatic visual icon for the ordeals of the Belgian army and the debacle of military reform in 1886–87. When Ensor switched Christ’s crown of thorns to a helmet, he relocated the suffering of the Man of Sorrows from a generalized Flemish past to a very particular divisive present. This shakoed Christ is laden with specific cultural meanings and tribulations. The color, shape, and upright feather connote the highest officer in a period before the army’s decline; the missing plaque and absent rampant lion evoke the plight of the officer without a mission. The failed attempt to revitalize the army consigned the officer of 1887 to a stock figure in a military masquerade; the helmet as a prop or empty shell signaled the condition of undervalued professionals reduced to ceremonial functions, frustrated by neutrality, and obliged to compete with a risible civic guard.

Ensor’s shakoed Christ also alludes to the distinctive predicament of the “army of the poor” in 1880s Belgium. The 1887 defeat of the reform bill prevented the nation from redressing the flagrant injustice of the “blood tax” of the remplacement system. As an infantry of “indigents,” recruits were despised and rejected by locals as “pariahs” and mistreated by brutalizing superiors.117 The effect of Christ’s crown of thorns—cutting his skin—remains visible in The Temptation. According to the New Testament, the injurious crown mocked and tormented Christ, the king humiliated, as captive. In the work of another artist Ensor admired, Hieronymus Bosch, a soldier places the crown of thorns on Christ’s head (fig. 2). In Ensor’s Temptation, Christ is not mocked by a soldier, Christ is mocked as a soldier. The red shako is the modern crown of thorns.

Military Maneuvers and Army Ridicule

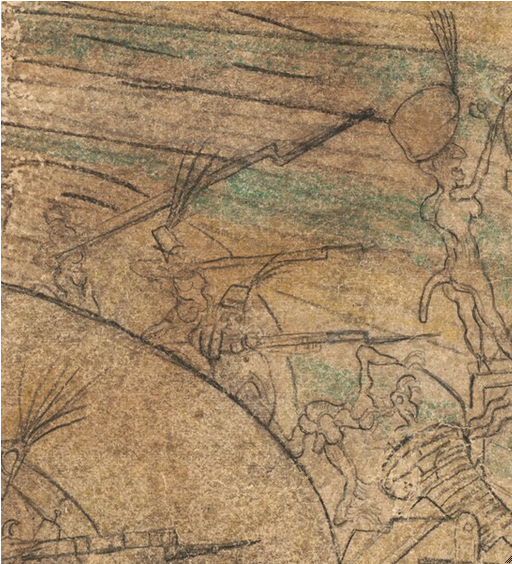

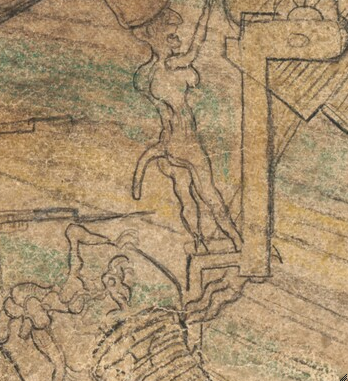

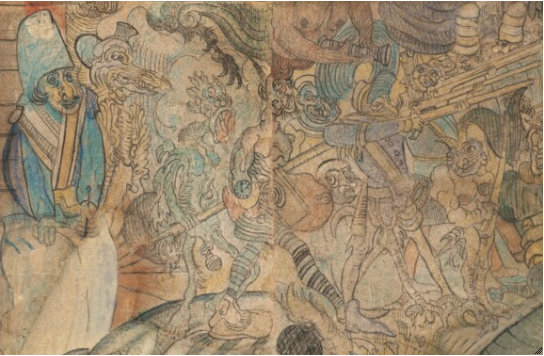

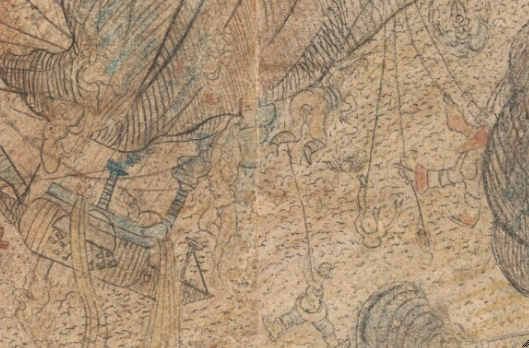

Christ’s sorry state is echoed in miniature in a spectacle of his fellow soldiers. Just below and to the left of Christ’s head, Ensor depicted clusters of tiny soldiers scrambling for position (fig. 23; sheets 3F, 3G, 4F, and 4G). They jostle in turreted towers shown partly crumbling. Two sets of figures aim their weapons from on high while a third group peers out from a covered overlook. Seven cartoonish soldiers appear on the first elevation, and Ensor has taken care to mark the signature parts of their military headgear: shakos with pompons for the infantrymen, and upright feathers on the tall shako reserved for the officer (fig. 24). Turning earnestly and clumsily in different directions and bearing silly smiles, the men point and shoot; Ensor sketched in the zigzag shapes of their long rifles, with bayonets attached (fig. 35). Across the way, in the second turret, three more soldiers ready their arms, with one staggering to hoist the extreme length of his bladed rifle (fig. 36).

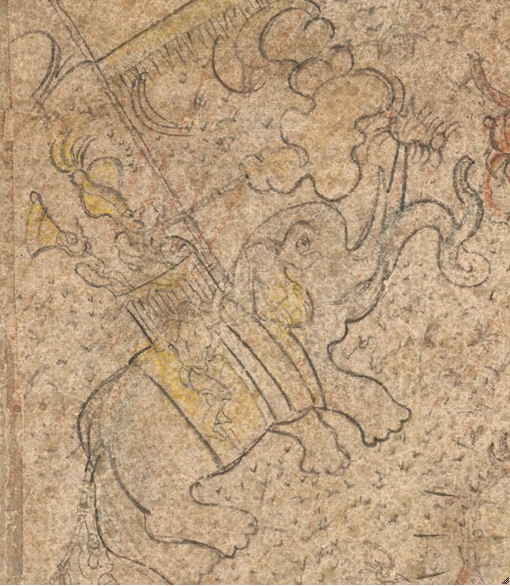

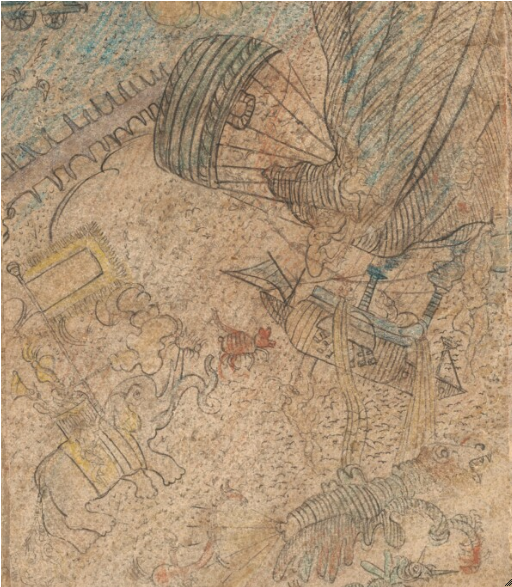

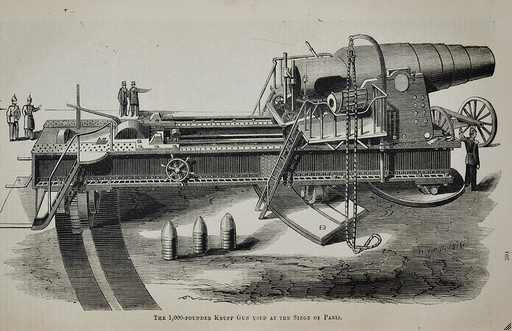

Here Ensor quite literally brought out the big guns: he drew two different types of cannons (fig. 37). The first, tipping over its fitted base, is archaic, lit at the breech by the beak of a strange erect bird. A much heavier and more modern cannon operates just above. Visible in Ensor’s careful rendering is an elaborate mount with extending platform and adjustable gear wheel that sets the cannon to target from its high elevation. Ensor depicted the formidable iron cone in the process of firing, indicated visually as a shaft of light. A pair of overturning tea mugs, liquid spilling, suggests the path of the blast, but no cannonball appears and no terminus emerges. A plume of blue smoke trails upward as the cannon fires, melding at the top with the black cloud that flows from Christ’s giant feather. The miniature cannon master sports his own large shako with another of Ensor’s precisely drawn flammes and mounts; his facial features, in profile, bear a striking resemblance to Leman’s, but the officer is naked. Ensor rendered him as ludicrous and gross. Although the path of the cannonball is nowhere to be seen, the officer conspicuously discharges a more phallic than fecal pellet from his backside. Ensor positioned the large turd carefully, just about to drop on to the tip of the bayonet steadied earnestly by one of the soldiers on the turret (fig. 38).

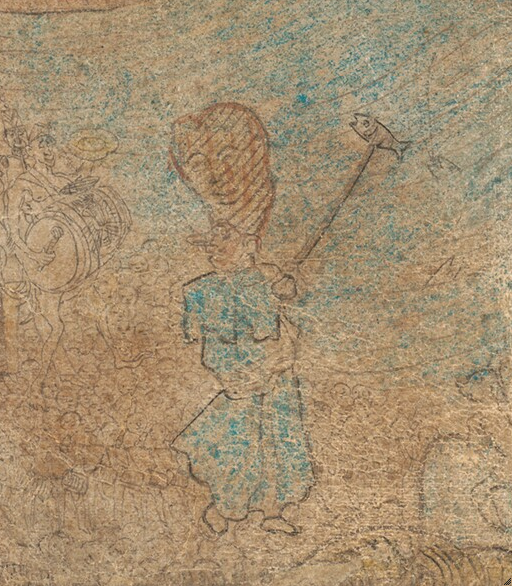

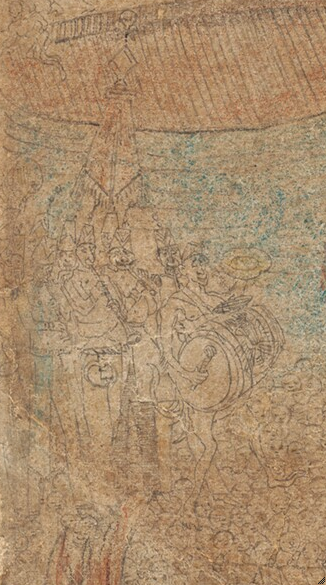

A second set of military men also appears in this section of the drawing. Below the fragmented towers and their dubious defenders, the sea roils, and ships of varied types ply the waves (fig. 39). By the shore (sheets 4F and 4G), Ensor drew groups of military marching bands on parade; clustered near the largest ship and port, they could be convened for a musical send-off overseas. High hats and drums are detectable in the swarm of tiny figures, and a comical drum major in an aqua tunic hoists a speared fish on the edge of his baton (fig. 40). He looks to his right where another drummer in blue stands in front of an officer with shako and plume holding the company standard, as well as yet another band marching in formation, this one with the triangular banner typical of a civil guard (fig. 41). Clarinet players are led by a smiling, naked bass drummer who wears his instrument across his chest. These stripped-down army music men evoke Ensor’s later comment that when he saw formal military band processions he imagined the soldiers “in their shirttails” (fig. 42).118

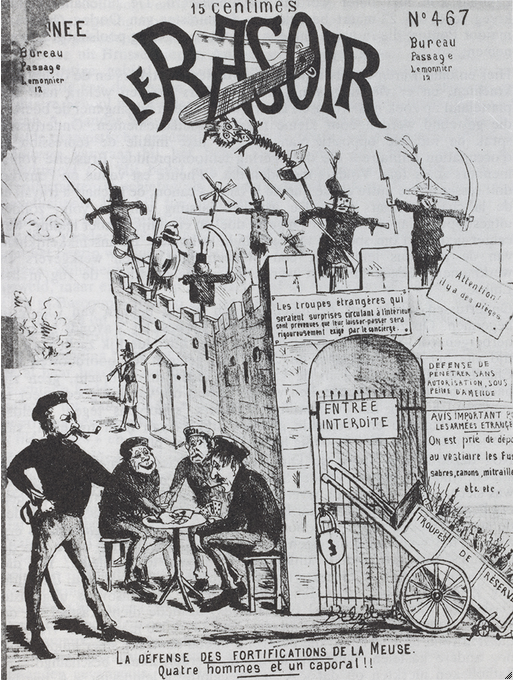

Marching bands in states of undress, a platoon of buffoons led by a defecating bombardier—these motifs are laced with Ensor’s particular brand of satirical and scatological humor. But the choice of subjects also reflects and expresses broader patterns of the crisis of the army in 1880s Belgium and its culmination in the debates around national army reform in 1886–87. The scene of bumbling defenders shooting from the towers is set in the central and distinguishing space of the Belgian neutral army: the fort system. Decades of criticism and calls for military reform had yielded only grudging appropriations for fortresses, the only essential for the country’s defensive army guaranteed by the Great Powers (fig. 21). Concentrated in and around Antwerp, the new forts were only partly completed by 1885, and many of the old ones remained dilapidated. When the 1886 campaign to end remplacement in favor of universal conscription failed, “palliative” measures came again in the form of fortress building, this time near Liège and Namur, underway in 1887. Ensor’s image offers visual testimony for the common charge of army critics of the period that “the Belgian Parliament agreed to provide the bricks required for national defense, but it has resolutely declined to furnish the men.”119 Leman was himself part of the military engineering establishment responsible for fort construction and improvements.

The equipment handled by Ensor’s army men reveals one of the underfunded Belgian military’s widely publicized problems: the inadequacy of materiel. The very long rifles with extender edge bayonets visible in the drawing are of the type still used in 1887 and derided by contemporaries as antiquated and cumbersome compared to the sleeker and more efficient Mausers used by other European armies. Furthermore, the concentration on siege defense and artilleries had led to an oversupply of certain weapons, especially cannons. Ensor’s tower battle juxtaposes two cannons, as if drawn from the racks of the overcrowded army storerooms: an archaic one with slender funnel, and a modern one, heavier and architecturally structured with platform, levers, and gears. But, as General Émile Wanty suggested, the newer one is of a type that was already obsolete: in 1887, seventeen years had passed since the Prussians had unleashed the astonishing power of the Krupp cannon and irrevocably changed modern warfare (fig. 43).120 The inadequacy of forts, manpower, and weaponry evoked in Ensor’s drawing form part of a broader visual iconography of military ridicule. In the same year of the army controversy, for example, a Le rasoir cartoon shows men “defending” Belgian forts as card-playing dolts commanded by an effeminate corporal (fig. 5). A shakoed watch guard with long bayoneted rifle and scarecrow puppet warriors staked on flimsy ramparts complete this popular counterpart to Ensor’s harebrained miniature soldiers in The Temptation.

While Ensor’s fort troops shoot to nowhere and marching bands swarm the shore, women warriors unleash lethal cruelty. Below the fort and the drum major in the aqua tunic are scenes of what Ensor called “horrible tortures [by] young and beautiful women” who pitilessly “bludgeon, beat, and burn” (sheet 5F and folio 5G/H).121 The contrast with the playful and vulgar uniformed fighting forces is extreme. Ensor depicted one woman smiling as she concentrates on slicing through the skin of her victim; red colored pencil indicates the blood flowing from the man’s throat (fig. 44). Adjacent to this, a blond woman is intent on yanking off, in one fell swoop, a man’s entire peeled skin cover (folio 5G/H).

These ghastly scenes oppress and torment Saint Anthony, as Ensor himself described.122 But they also operate in another register, representing spatially the dramatic divergence between the state of military manhood and female powers. Ample evidence exists, both visual and textual, that Ensor had a troubled relationship with women and may have suffered from sexual anxieties.123 But the particular form of Ensor’s personal crisis converged with a historically specific crisis of militancy and masculinity in 1880s Belgium. Dishonored, as Captain Charles Lemaire lamented, as “old women and saber rattlers,” and cast in 1886 in the popular press as useless and “neutered,” the Belgian army concentrated a complex of quandaries.124 Ensor’s Temptation draws out a number of these shared dilemmas in his depiction of military figures and militant women.

The “Cowardly Belgians” Controversy and Ensor’s Napoleon and Chicken Soldiers

The tribulations of the military men in The Temptation are deepened by the presence in Ensor’s drawing of another site of contemporary dishonor for the Belgian army of the 1880s. The suffering, shakoed Christ floats over a sequence of sheets (6A and 6B/C) that may allude to the late-nineteenth-century debate over the alleged misconduct of Belgian troops at the decisive battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo. In the corner of the section, Napoleon in his uniform and bicorne, marks a plan, pen in hand. His papers rest on the naked backside of an otherwise unseen person (fig. 45). Nearby are monsters and a figure wearing a nose ring and striped stockings; he carries part of a spear and moves forward. His arm is severed, with a dial or clock showing at the stump. Next is a row of uniformed soldiers lined up with their rifles drawn in the “ready, aim, fire” position. The soldier closest to the viewers presents an upturned cap and the face and legs of a chicken (fig. 46).

The backside as tabletop and resting surface recalls the man on all fours on the left of Bosch’s Temptation of Saint Anthony triptych (fig. 4), and the striped stockings of the warrior resemble the Spanish mercenaries’ hosiery in The Massacre of the Innocents by another of Ensor’s favorite Flemish artists, Peter Breugel I. But the inclusion of Napoleon and the chicken soldiers expresses themes and motifs of history, memory, and the military particular to Ensor’s world. The artist shared with many in Belgium a fascination with and ambivalence toward Napoleon. Despite onerous conscription and taxes during the occupation of the Low Countries, the French ruler was nonetheless admired for reviving the prosperity of Antwerp and reopening the port; the Bonaparte Dock still formed a hub of the expanding city harbor in the 1880s.125 The physical fabric of Ensor’s native Ostend centered on the Napoleonic fortifications, which began to be dismantled as he was growing up.

Ensor, like many artists of his time, had a broad interest in the leader and his legacies.126 But The Temptation relates specifically to an allegation circulated in the European press and political culture: that Belgian troops had run away at the Battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo. The controversy began with the publications of military historian Captain William Siborne in 1844, was enflamed by a parliamentary speech given by Lord Liverpool rejecting what he called the “cowardly Belgians” as possible allies in the Crimean War, and found its way into William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848) and Baedecker tour guides (1900). Despite decades of refutation and indisputable evidence to the contrary, Belgian soldiers were still cast as “poltroons” or chickens at the front lines of 1815.127 Thus national military crisis and international military denigration were intertwined in the 1880s. It is no wonder that Ensor’s shakoed Christ sheds tears with Saint Anthony.

A few years after making the drawing, Ensor acted out some of the antics of his miniature army in The Temptation. In 1890 he was photographed with his friends, all in costume; the artist wears the garb of a military grenadier in command of a Pyramid of Clowns (fig. 47). During the Napoleonic era, the grenadiers composed the fiercest front ranks who led the charge in battle; their size and fury were known to inspire terror in the enemy. Like the shako in the drawing, Ensor’s bearskin grenadier’s hat signals both comic theatricality and the former glory of an earlier fighting army.

The Congo Free State and Ensor’s African Figure

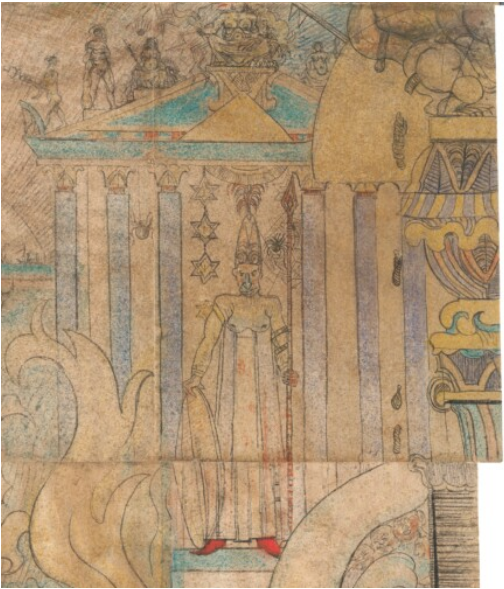

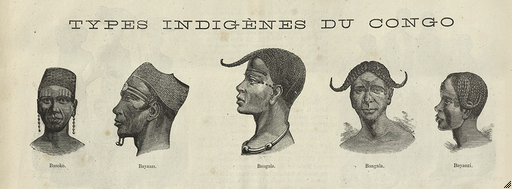

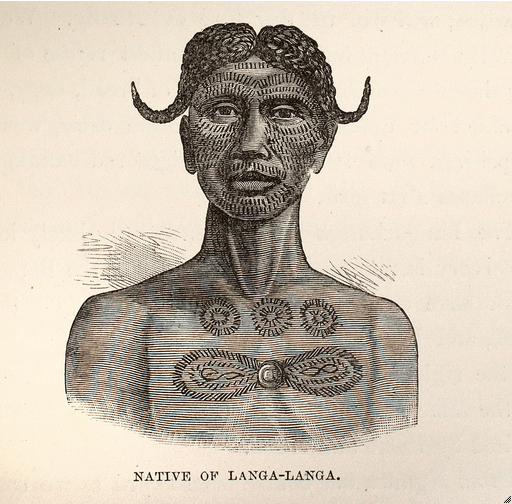

The right side of The Temptation displays a columned classical temple (fig. 48; folio 3H/I). In the center stands a tall African figure holding a spear and shield and wearing a high-feathered conical headdress, a robe below a bared chest, and bright red shoes. Zooming in reveals orange-red pencil streaks on the figure’s forehead and cheeks. This African—or more particularly Congolese—presence in The Temptation suggests some specifically imperial contexts and associations that took shape in Belgium during the first decade of exploration and foundation of the Congo Free State (1878–88). The Congo emerged not only as a site of territorial expansion for Belgium, but as a space for the reclamation of military honor. Undervalued at home, officers found opportunities for initiative and daring overseas.128 Ensor’s drawing demonstrates a visual imagination marked by the traces of this distant new world flowing back to Belgium.

One of the earliest and most enthusiastic supporters of the new Congo state was A.-J. Wauters, a progressive art critic and foundational scholar of Flemish art history who wrote early studies of Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling, celebrated Bruegel and Peter Paul Rubens, and provided the first synthetic view of their art for a new Belgium in his 1883 book, The Flemish School of Painting. Wauters, who was appointed a professor at the Brussels Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1887, is an important touchtone of Ensor studies, as he reviewed the exhibitions of Les XX in the press and was one of the earliest consistent supporters of the artist. In his letters Ensor places Wauters in his pantheon of writers who bolstered his early career when few were noticing or rising to defend him.129 At the very moment that Wauters was taking note of Ensor’s talent and defining a canon for Flemish primitives, he was also widely publicizing King Leopold II’s expansion in Africa. Beginning in 1878, Wauters published numerous books on Africa and the Congo, and from 1884 he edited the two premier magazines of the imperial period: Le mouvement géographique and Le Congo illustré.130

Iconography of the Congo in “The Temptation”

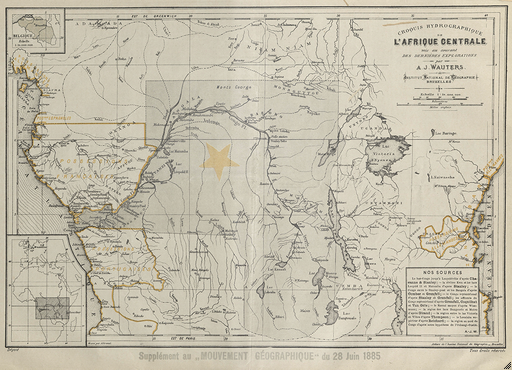

Motifs of the Congo appear in numerous ways in The Temptation. The four yellow stars near the African figure (three to his right, and one just at his shoulder) allude to the flag of the Congo Free State—a yellow or gold star on a blue ground—made official in 1885.131 The proliferation of books, images, magazines, photographs, and exhibitions about the Congo in Belgium seized on the new symbol. It can be seen in the yellow star stamped on the fold-out map of Central Africa in Wauters’s 1885 Mouvement géographique (fig. 49), which claimed indelibly for Belgium (whose own map appears, to scale, at upper left) what Wauters referred to as “the last great white space” on the so-called dark continent. Maps like these formed murals decorating the Antwerp Bourse in 1885, while the Congo Free State flag was prominently featured at the Antwerp World’s Fair that same year, and in the event’s press coverage.132 Ensor’s framing of his African figure with the four yellow stars is thus provocative and resonant.

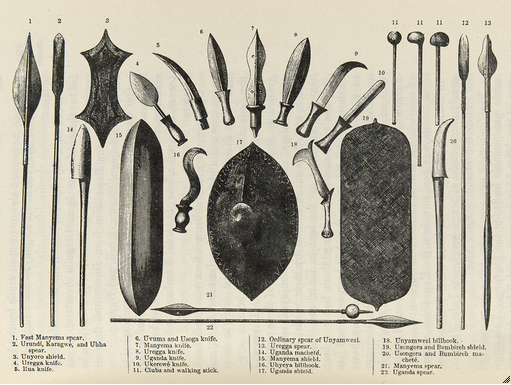

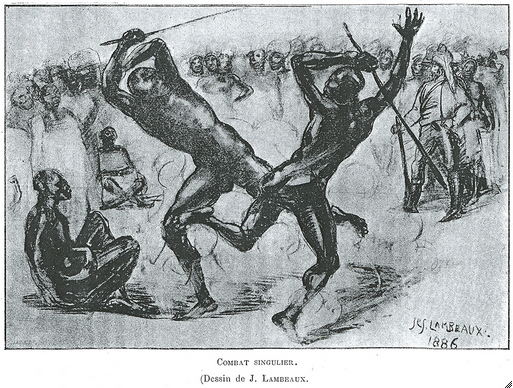

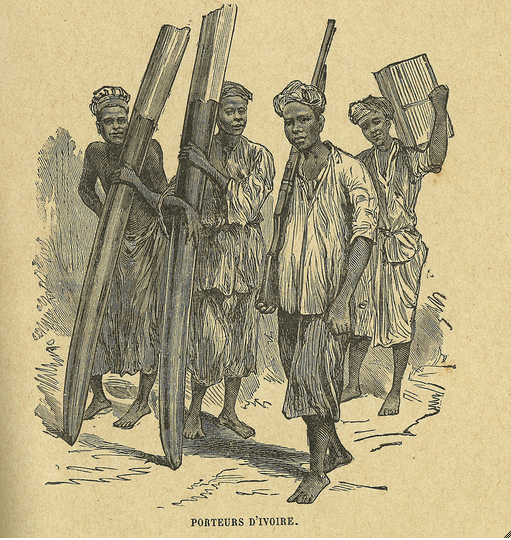

Depicting the figure with spear and shield evokes another set of references available in 1880s Belgium. Objects from the Congo began trickling into Belgium, brought by returning officers and explorers, at an accelerating pace starting in 1885. The artifacts assembled for the Antwerp World’s Fair were transferred to the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels in 1885.133 Native weapons—spears, hatchets, arrows, shields, knives, swords, and clubs—particularly fascinated the Belgian public. Widely read books by Georg August Schweinfuth (1874) and Henry Morton Stanley (1878; 1885) included discussions and plates illustrating the arms of groups such as the “Niam-Niam,” the “Vouanyamouési,” and the “Ougannda” (fig. 50). The simple conical projection seen in the Stanley engraving of the “Manyémas shield” is echoed in the shape that Ensor penciled in to give rudimentary depth to the shield of the African man in The Temptation. Ensor’s contemporary and fellow Les XX member, the sculptor Jef Lambeaux, made a drawing in 1886 imagining Congo warriors with lances aloft entitled Combat singulier (Man-to-Man Combat). This drawing was published as an illustration in the two-volume book La vie en Afrique (Life in Africa) by Lieutenant Jérôme Becker, an early Belgian officer in Central Africa (fig. 51).134

Collecting and showcasing native weapons from the Congo had a very different meaning for 1880s Belgium than for other European imperial powers: it attested to the strength of an army that could not wage war at home. Ensor had often visited the Institute of Natural Science in Brussels to study shells, fossils, and minerals in the company of Ernest Rousseau junior and Mariette Rousseau. Ernest Rousseau senior’s teaching position at the École Militaire, and the presence of Leman at the Rousseaus’ salons, which Ensor also attended, would have placed the artist at the center of the military world, for which the Congo Free State offered the best hope for frustrated young officers.135

In an 1898 letter, Ensor recounts an early source for his interest in masks. He recalls his grandparents’ Ostend shop, a “confused mass” of masks and curios that included “savage native weapons.”136 Patricia Berman has discovered that the shop offered West African artifacts for sale, and these likely inspired the evocative and identifiable Congolese masks that Ensor depicted among the crowd in Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (fig. 16).137 In his memories of the shop, Ensor may also have conflated these earlier objects with Congolese materials such as weapons, ivory tusks, latex, and palm oil that flowed into Belgium in the 1880s.

The face, clothes, and tall hat of the African figure also summon up associations to the Congo. The orange-red streaks on the forehead and along the cheekbones (fig. 52) suggest that Ensor may have absorbed the new fascination with scarification in 1880s Belgium (fig. 53 and fig. 54).138 Similarly, the figure’s robe, with its push-up garment and arm bangles, recalls features of the most well-known plate from the early explorer literature circulating in Belgium: King Munza in Full Dress in Schweinfurth’s The Heart of Africa (fig. 55).139 Additionally, the red shoes may respond to accounts in travel literature that natives were particularly enthralled by the color. Wauters’s imaginary 1881 account of meeting Chief “Baba Panza” recounts how a gift of red gloves secured land and the title of chief for the European visitor.140 And at the Antwerp World’s Fair of 1885 the Congolese chief, Masala, was given a red silk umbrella, among other gifts.141

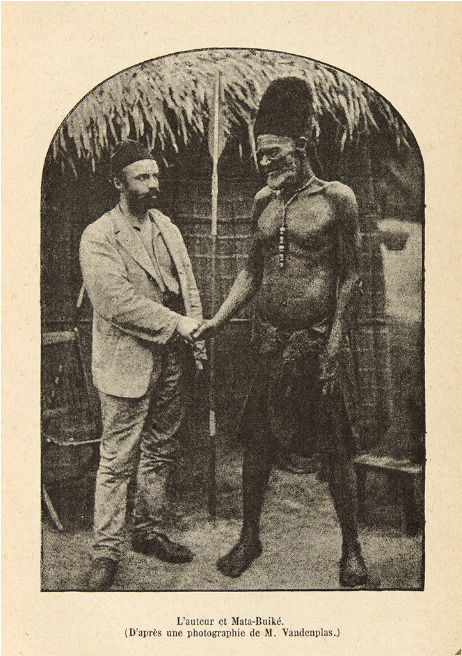

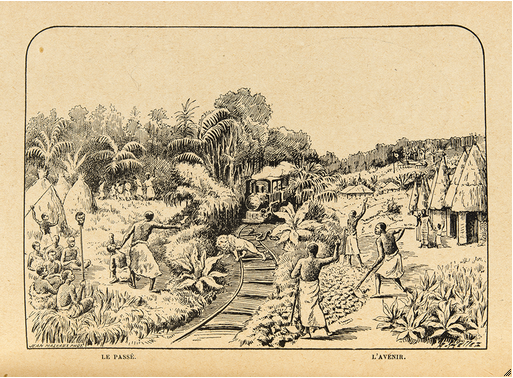

The flamboyant hat of Ensor’s standing figure bears some affinity to the high conical headdresses from the Congo depicted in 1880s Belgium, from King Munza’s stack and drape to Coquilhat’s Mata-Buiké’s elevated nose cone (fig. 55 and fig. 56). But it also corresponds visually to the tall red-feathered shako on the head of Ensor’s Christ (fig. 57 and fig. 58). The African hat, with its clearly rendered mount as feather perch and arcing red plumes on either side, echoes the similar shapes and splay on Christ’s hat. Ensor thus drew attention to the military and imperial contexts of the drawing, and the connections between them. Both hats were outdated; the African’s is a miter and of a type that had been worn by European army grenadiers through the end of the eighteenth century (fig. 6).142 Such antiquated parts of military uniforms were routinely used by explorers as items of trade in the Congo; Stanley and King Leopold discussed a plan to market army “hand-me-downs” (vieux habits) in the new Free State.143 Congolese people brought to the 1885 Antwerp World’s Fair were also dressed in a hodgepodge of outmoded uniforms.144 The appearance of an African figure with a feathered miter thus gave Ensor’s drawing new meaning and resonance, uncannily depicting living people cajoled into accepting the “high hats” of armies of the past in exchange for loyalty to new masters in the present.

Imperialism, Technology, and Industry

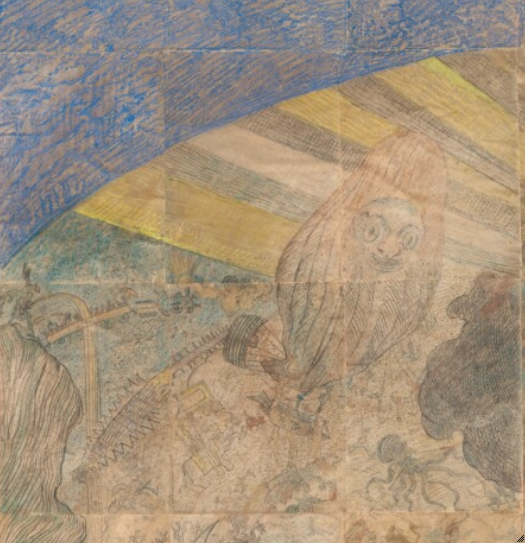

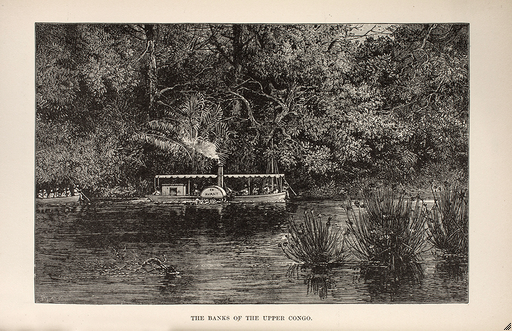

Like grace notes in a musical score, a final field of imperial meanings reverberates in The Temptation. A section at the upper left, on the same plane as the standing African figure and Christ’s floating head, and diagonally aligned with Anthony’s head, shows four motifs of technology and transport (fig. 59; folio 2B/C and sheets 3A, 3B, and 3C). A miniature train moves through the sky, its locomotive puffing as it pulls open carriages loaded with passengers. Below it appears an aerial trio: a hot-air balloon being tethered by small figures; a steamboat with two stovepipe funnels; and a wide-eyed elephant bearing two mounted riders (fig. 60). Ensor presented the elephant’s longer tusk as a spear, with a creature stabbed on the end of it. The balloon, steamer, and elephant are propelled upward by an explosion issued not by a cannon but a furnace (fig. 61) very much like the ones that cooked coke for fuel in the Belgian coalfields of Charleroi and Hainaut since 1850 (fig. 62). There is a cultural logic to this apparent visual scramble that has not previously been noted: all these motifs allude to the technologies, treasures, and ordeals of Belgium’s overseas expansion.

While Ensor’s “little engine that could” may recall a similar motif in Honoré Daumier’s prints, the evocative form has references closer to home in Belgium.145 The railway formed the centerpiece of Belgium’s economic production from the 1830s and continued to do so during its Second Industrial Revolution in the 1880s. The railroad transformed all the spaces and places of Ensor’s physical environment in his formative years, especially in Ostend and Brussels, and was celebrated with festivals and pageants.146

But trains floating across the skies had other implications. Ensor composed his drawing after two decades of Belgian investment in and exporting of its vaunted railroad system across the globe to countries as diverse as Persia (now Iran), Egypt, Brazil, China, Peru, and Russia. Global railway expansionism reached the heart of Les XX itself in 1887. At a time when Ensor was arguing about his exhibits with one leader of the group, Octave Maus, the other, Edmond Picard, volunteered for a travel and diplomatic mission to Morocco in December 1887, with the goal of soliciting investments in railway technology from the sultan. Ensor’s colleague and fellow Les XX member Théo van Rhysselberghe accompanied Picard on the three-month trip, which yielded an 1888 illustrated book entitled El Moghreb al Aksa: Une mission belge au Maroc (The Farthest West: A Belgian Mission in Morocco).147

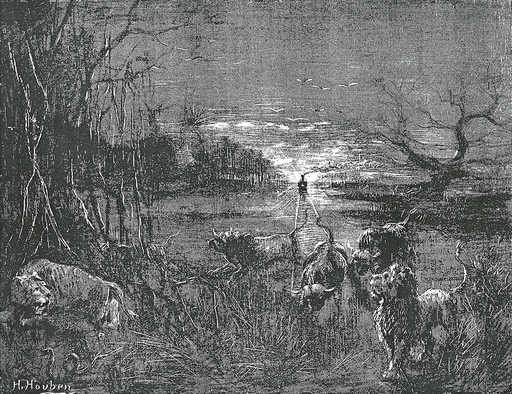

Picard’s travels and Ensor’s Temptation coincided with the ratification of the planned project for a Congo railroad, the cornerstone of Leopold II’s African venture. In February 1887 Parliament authorized government backing of 150,000,000 francs’ worth of loans to float the Sociéte Anonyme du Chemin de Fer du Haut-Congo (Upper Congo Railway Company).148 Work on the railway began only in 1890 and quickly encountered a reality far different from the optimistic predictions of the project plans.149 Nonetheless, during the period Ensor created The Temptation, Belgium witnessed an efflorescence of images projecting the landing of its trains in faraway Africa (fig. 63, fig. 64, and fig. 65). Below the railroad Ensor showed a melee of vehicles: a capsizing hot-air balloon collides with a steamer as an elephant runs toward them (fig. 66). Zooming in we can see multiple figures actively engage with all three, variously pulling, climbing, clambering, and hoisting.150 Here Ensor traced a startling visual archeology of empire and its inevitable discontents.The ivory-bearing elephant below the railroad invites further imperial associations. By 1887, when Ensor joined Henry van de Velde’s exhibition of L’art indépendant in Antwerp, the word “ivory” rang in the air as elephant tusks were disgorged from cargo ships to sheds at the bustling port. Stanley’s early books of 1879 publicized his astonishment at finding ivory tusks as “abundant as fuel” in Africa and discovering an entire temple composed of tusks along the Aruwimi River.151 Imperial books and images circulating in Belgium in the 1880s, including those by Wauters, Jérôme Becker, M.-G. Alexis, and Camille Coquilhat, echoed Stanley’s fascination with the idea of a limitless supply of the material (fig. 67).

Previous Ensor scholars have described the elephant riders as mahouts and identified the animal as an Indian elephant, largely based on the high mounted seat. But the rifle-shooting figure on the elephant, the prominent tusks, the pole-up flag and banner, and a vaulting side figure challenge this interpretation: Africa, indeed, may be hinted at here as well (fig. 68). In the first decade of exploration and foundation of a state in the Congo, Asian and African elephants were discussed together as part of fantastical plans for the overseas enterprise. Wauters in particular published pamphlets, books, and articles from 1880 to 1886 in which he proposed importing Asian elephants to Africa and using them there as horses, hunters, and carriers; Asian handlers could also be brought to tame them. Wauters envisioned this as a little colony within a colony and the animals as loyal protectors of their European masters. In an 1880 text he projected an image of compliant giant elephants transporting small steamer ships on their backs, the “precursors” of the civilizing forces of the tram and railway.152

Ensor produced two other elephant works that deepen the Congo allusions in The Temptation: The Capture of a Strange Town (fig. 11) and The Elephant’s Rage (fig. 69). Comments on the latter colored print describe it as “the elephant’s joke,” but the title and the image itself express the elephant’s wrath as it is attacked.153 A battle commander on the far right carries a banner reminiscent of the Congolese flag. The warriors here are aided by a small ambulatory cannon being ignited on the right, another signature weapon of Belgium’s scramble for Africa. In The Temptation the elephant in the sky in sheet 3B moves toward a paddle steamer quite unlike anything Ensor could have seen in the harbors of Ostend or Antwerp. But it corresponds very closely to the paddle steamers that plied the mighty Congo River, illustrated abundantly in 1880s Belgium. Indeed, Stanley’s own, widely publicized vessel, called the En Avant, was a half-circle side-wheeler much like the one Ensor so carefully rendered (fig. 70 and fig. 71).

In sheets 3B and 3C (fig. 66), activity near the steamer suggests another imperial element in Ensor’s mix. Below the tub a figure pulls on what initially looks like two cords under the steamer; on closer inspection, part of a rope line is legible, indicating he is trying to board (fig. 72). The figure’s feathers and ankle bands suggest allusions to a Native American. This confluence recalls how the dramatic arrival of Western steamships in Africa provoked terror and flight among local peoples, or aggression and skirmishes with the Europeans. Battles between Western ships and the Bangalas and other tribes appeared in Stanley’s 1885 Congo books, excerpted by Wauters, and in Coquilhat’s 1888 Upper Congo volume, among others.

In sheets 3B and 3C, the combination of the steamer with a descending hot-air balloon amplifies the imperial resonances in the cluster of transport. As others have noted, hot-air balloons strongly appealed to Ensor, but they also had specific military and imperial meanings in his world.154 General Emile Wanty, in a section of his book tracing the appeal of the Congo to young officers languishing at home in the neutral army, described an epic dramatization at the Cirque Royale de Bruxelles in 1892. As Wanty reported it, crowds sat breathless and “flabbergasted” in the vast twenty-sided hall as an actor playing Stanley landed a hot-air balloon in the midst of a Congolese native village under attack by Arab slavers. This was followed by scenes of combat, drawing up a peace treaty, saluting the flag, and—for the grand finale—an “apotheosis for Civilization.” Theatrical simulations such as these, Wanty noted, expressed and deepened public longing for heroism and daring.155 Ensor’s visions puncture this bravura, upend technological hubris, and spill over from carnival to carnage. But the pile-up in the skies of The Temptation—where clowns appear tethering a careening balloon—converges uncannily with the circus spectacle (fig. 73). Whether or not Ensor might have seen this performance is less important than what the convergence tells us about collective fantasies in 1880s Belgium, when a fictitious state, owned by the king, was run from Brussels and manned by military officers who could not wage war at home.

Ensor’s Militancy and Empire beyond “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”

In a penetrating commentary, writer Emile Verhaeren noted how the sprawling and teeming forms of Ensor’s Temptation joined, without mediation, the mythic and the specific, the metaphysical and the particulate, the most ancient and timeless and the most up-to-date and contemporary.156 My essay has emphasized the salience of two such “up-to-date and contemporary” contexts of 1880s Belgium, and the ways Ensor gave them visual form in 1887–88: the crisis of the army and the defeat of efforts to reform it; and Belgium’s expansion into Africa. Both the army and the empire had long-term effects on Ensor’s imagination and artistic output.

Although Ensor did not present Christ as a military man before or after The Temptation, the military marching band dominating Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 extends the drawing’s lampooning of the army.157 In the painting, a group of blowhards puff diligently on their horns to strike up the music (fig. 74). They are led by General Charles Pontus, minister of war, a staunch defender of the status quo, shown with a mustache, a feathered shako, and a pince-nez over empty eye sockets. Like the blind leading the blind, Pontus moves ever forward, “en avant,” his torso laden with medals, flamboyantly honorific. Indeed, Ensor depicted the general from the chest up, as not so much wearing medals but as a medal, the embodiment of an army confined to ornamental functions and parades.

In The Temptation, Ensor addressed the military by satirizing Leman, the professor and lieutenant general whom he knew from the Rousseau family salon. (As mentioned above, the ribald profile in the drawing of the cannon-igniting commander, who expels a giant turd, resembles Leman.) The artist’s Baths at Ostend also includes a recognizable portrait of Leman among the shoreline crowd shown scrutinizing the raised naked buttocks, amorous couples, and lewd behavior of those in the water (fig. 3). And Leman appears in an 1890 painting as Ensor’s debating partner. The artist faces off with the officer, who has lit a fuse to detonate a miniature toy cannon. Ensor, armed with an oversize palette and a giant brush, stops the charge by squeezing his forefinger into the cannon barrel (fig. 15).158

Ensor’s Temptation percolates with signs and motifs from the Congo. Traces of the Congo appear again in Christ’s Entry, with the Central African masks among the parading crowd. This mélange indicates how the first decade of Congo discovery and foundation infiltrated Ensor’s visual imagination while offering Belgium the possibility of distant military adventure and conquest. In the decades after 1890, profits from the Congo Free State transformed the economy and culture of Belgium, while revelations of violence against the natives there sparked controversy and national and international criticism.

The Congo Free State also had a long-term impact on Ensor personally. His native town became a hub of imperial modernization, transformed from a sleepy fishing village into an opulent center for international tourism.159 King Leopold II took Ostend as one of his pet projects, not only expanding his own mansion there but also cajoling city councilors to create parks, hotels, and modern conveniences. Less well known, but well documented, is that Ostend became a boomtown for Congo investors. The savvy king and two key financiers of the Congo wild rubber companies used their new revenue to buy up and develop beachfront properties in large parcels.160 These real estate ventures of the late 1890s flattened many of Ensor’s beloved dunescapes, which he lamented. The physical world of Ensor’s Ostend was thus permanently marked by the financial proceeds from the Congo. Ensor grew up as the vestiges of Napoleon’s empire, the Ostend fortifications, were dismantled. As he grew older, Ostend was further reconfigured by the monies accruing from Belgium’s African empire and its sovereign, King Leopold.

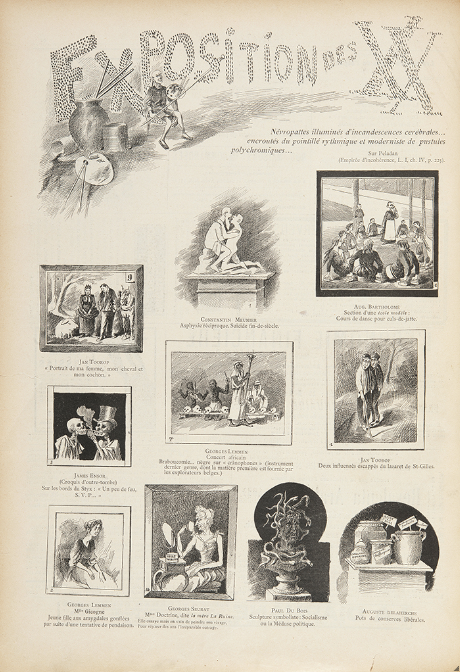

In addition, the critical reception of Les XX’s exhibitions became increasingly marked by language and imagery about the Congo after 1889, signs of a cultural imaginary filling up with Africa. In 1889, for example, a caricature of the Les XX exhibit in Le patriote illustré called L’art décadent à l’exposition des XX (Decadent Art at Les XX) showed an image, purportedly by “C. Monet,” where “a native from the Congo” experiences the “marvels of shaving with glycerin soap”: the African discovers his white skin underneath.161 A hostile review in La fédération artistique of the 1891 Les XX exhibition that featured Gauguin’s wood sculptures derided Gauguin as a “Congoiste” and a “Congolese sculptor tout court.” These works would “sell like hot cakes” “among the savages of Stanley Falls” the critic wrote.162 Finally, a broadside of 1892 reviewing Les XX mocked various aspects of the entries of Ensor, Jan Toorop, and Constantin Meunier, among others. In the middle of the sheet was a cartoon attributed facetiously to Les XX artist Georges Lemmen called Concert africain, showing Congolese figures playing the Braboucomie alluding to the Brabançonne, the national anthem of Belgium (fig. 75).163

As Ensor’s life and career progressed, and his critical reception improved, the venom and rage of 1887–89 subsided. He tempered the sorrow and fury of The Temptation and Christ’s Entry, although his biting satire and blending of humor and aggression persisted. His work could still cause scandal: commentators derided The Baths at Ostend, for example, as lewd and crude. But King Leopold II, a frequent visitor to Ostend who maintained a grand chalet at the beach and helped transform the seaside town, admired Ensor and this work.164 In 1903, the king awarded the artist the title of Chevalier of the Order of King Leopold.165

Less marginalized and aggrieved than in the late 1880s, Ensor nonetheless continued to resist all authority. Describing his intense oppositional outlook three decades later, Ensor invoked the language of combat. Where earlier he had masqueraded as a costumed grenadier among clowns, he now assumed the grenadier’s role as artist-bombardier. “Cannoniers to your guns! Brace at your batteries! . . . Blast night and day. Light bursts out from the shock of bombs. . . . Let us salute art’s renewal, art’s freedom. . . . Art clears a path by means of cannon shots.”166