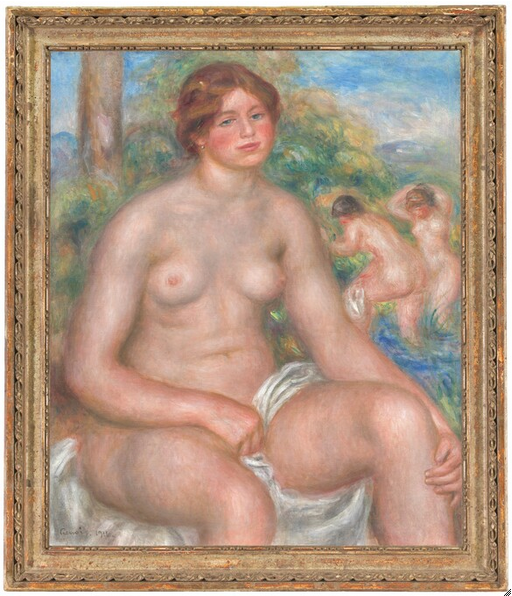

Cat. 25

Seated Bather

1914

Oil on canvas; 81.1 × 67.2 cm (31 7/8 × 26 7/8 in.)

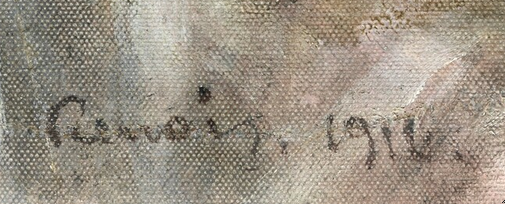

Signed and dated: Renoir. 1914. (lower left, in black or brown paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Endowment; through prior bequest of Annie Swan Coburn to the Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Fund; through prior acquisition of the R. A. Waller Fund, 1945.27

Seated Bather and the Polemic of Renoir’s Late Nudes

Following a visit to Renoir’s Paris studio in January 1886, Berthe Morisot noted in her journal: “Two drawings of nude women going into the sea delight me as much as those of Ingres. He said that nudes seemed to him to be one of the essential forms of art.” Indeed, the nude would come to dominate Renoir’s work for the next three decades and define his late period style. Later in life the artist was candid about his obsession with the theme. As he told his son Jean shortly before he died: “Perhaps I have painted the same three or four pictures all my life. But one thing is certain: ever since my trip to Italy I have been concentrating on the same problems.”

The pneumatic form of the model in Seated Bather, characteristic of Renoir’s late figure paintings, verges on the surreal. During the artist’s lifetime these late nudes, whose rhythmic contours follow no prescribed canon of beauty, provoked extreme reactions, and it is hard to believe that Renoir remained unaware of the controversy surrounding them. Mary Cassatt, who exhibited with the Impressionists, visited Renoir in Cagnes several times in 1913 and early 1914 and became alarmed by his increasing frailty and apparent isolation. In a letter to the American collector Louisine Havemeyer, Cassatt wrote scathingly: “He is doing the most awful pictures or rather studies of enormously fat red women with very small heads. Vollard persuades himself that they are fine. J[oseph] Durand-Ruel knows better.”

If the Durand-Ruel family held any reservations about this work, it did not stop them from actively buying from Renoir. Between 1908 and 1914 they acquired nearly two hundred paintings from the artist (presumably most were recent) for a total of nearly 500,000 francs, a sum that does not include additional purchases made by collectors and other art dealers such as Ambroise Vollard. The deposit of Seated Bather with Durand-Ruel in August 1914, likely not long after it was painted, reflects an unabated demand for Renoir’s latest interpretation of the nude.

The most passionate aficionados of late Renoir nudes were leading artists of the avant-garde working in Paris. In July 1919 the art dealer Paul Rosenberg wrote Renoir that Pablo Picasso desired to meet with him during a planned visit to Paris the following month, though it is assumed that Renoir’s poor health prevented this rendezvous from taking place. After Picasso made a trip to Italy in 1917, he entered a classical period of his own and was especially attracted to Renoir’s late bathers. Picasso’s Large Bather of 1921 (Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris) openly confesses admiration of the elder artist and seems to emulate Seated Bather in the pose and the model’s voluminous shoulders, arms, and legs. The poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire wrote glowingly of how Renoir “uses his last days to paint these fabulous, voluptuous nudes which will be admired in years to come.” Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard were among the many visitors the artist welcomed in Cagnes in the later years of his life, and they came to see the work, not to pay homage to an Impressionist pioneer. The ubiquity of the bather theme in the work of these two younger artists owes as much to Renoir’s example as to Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres or Paul Cézanne.

Endorsement by collectors and these luminaries of Modernism transformed late Renoir paintings in the eyes of critics. His late work came to represent a new beginning for twentieth century art, rather than a final flourishing of nineteenth century naturalism. When Seated Bather appeared in a benefit exhibition organized by Durand-Ruel, New York, in April 1942, the New York Times wrote: “Renoir’s final effort at its very best, the magnificent nude called ‘Baigneuse Assise,’ dated 1914. This is one of the greatest paintings created in our time.” Not all were convinced, however. A frequent visitor to the Durand-Ruel gallery in New York at the time of the exhibition, Robert Sterling Clark, grandson of the business partner of Isaac Singer, refused to add a late nude to his collection of about thirty Renoirs, most dating to before 1900. When Clark learned in June 1944 that the Art Institute of Chicago was interested in acquiring Seated Bather, he dismissed it as “a great big mushy gelatinous fat woman with a sad face strawberry tint, has no bones only fat.” Indeed, by the time Clark was writing, this response typified attitudes toward the late nudes.

Renoir’s Model for Seated Bather

The model for Seated Bather is probably Madeleine Bruno, a young girl from Cagnes, who began working for Renoir in early 1914 and assisted in his care as he grew more infirm. She appears quite petite and slim in a photograph taken in the garden of Renoir’s home at Les Collettes in April or May 1914 (fig. 25.1). Renoir’s regular model, Gabrielle Renard, had joined the Renoir household a month before the birth of Jean Renoir in September 1894 and had been posing nude for Renoir since 1900. She left in late 1913 after quarrelling with Renoir’s wife, Aline. Madeleine continued to work for Renoir until at least 1916, when she posed as a standing bather of equally large scale (The Bathers, 1916; private collection [Dauberville 4281]). When asked about her role as a Renoir model in the 1970s, Madeleine found it difficult to recognize herself in the curvilinear forms of his figures.

Renoir’s Classicism

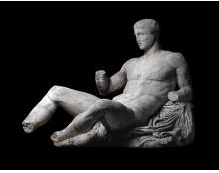

Renoir’s interest in and admiration for the art of Ancient Greece is clearly articulated in the preface he prepared in 1909–10 for the reprinting of Cennino Cennini’s Renaissance treatise on painting. As Robert Herbert has pointed out, Renoir’s long draft for the Cennini preface, which was edited for publication in the Catholic journal L’Occident, refers continually to how the power of Greek art is derived from religion: “Conscious of their weakness, ancient peoples felt the need to shelter themselves behind divine power.” The year the Cennini treatise was published, the Thurneyssen family of Munich commissioned from Renoir a portrait of their son Alexander as an Arcadian shepherd (fig. 25.2 [Dauberville 4267]), completed the next year in a pose that makes explicit reference to the figure of Dionysus on the east pediment of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens (fig. 25.3).

The monumental gods of the Parthenon pediment may also be a source for the pose in Seated Bather, painted three years after the Thurneyssen portrait. The figure’s massive scale can be compared with the formidable proportions of the three goddesses (Hestia, Dione, and Aphrodite), who observe the birth of Athena on the east pediment (fig. 25.4). As Kenneth Clark observed of Renoir’s late nudes: “In the unselfconscious acceptance of their nudity they are perhaps more Greek than any nudes painted since the Renaissance, and come closest to attaining the antique balance between truth and ideal.” Clark reproduces Seated Bather to illustrate his point that in the early part of the twentieth century Renoir developed “a new race of women, massive, ruddy, unseductive but with the weight and unity of great sculpture.”

While Renoir liked to think of his art as rooted in nature and not based in art theory of any kind, the exaggerated proportions of these late nudes raise the question of whether they are simply erotic fantasies or reflect a complex artistic goal in tune with the times. In particular, Renoir’s late nudes can be understood in the context of a psychology of style, part of a broader movement toward spirituality and a definition of the beautiful that lay outside accepted academic practice. In his emulation of the solid proportions of ancient Greek sculpture, Renoir sought a path to the mystical source of the southern classical tradition. Just as the artist endeavored in the 1870s to find universal truths in the popular culture of bohemian youth, in these late nudes he pursued a timeless classicism that he imagined to originate with the inhabitants of an earthly paradise at the “primitive” beginning of the Western tradition. Toward the end of his life Renoir marveled: “What admirable beings those Greeks. Their existence was so happy that they imagined that the gods, to find their paradise and to love, descended to the earth. . . . Yes, the earth was the paradise of the gods. There, that is what I wish to paint.”

Renoir’s Late Impressionist Style and Seated Bather

The Parisian artist Albert André first visited Renoir in the south of France about 1902 and became a devoted promoter of the artist’s work and one of the most observant of his late biographers. His book on Renoir appeared about May 1919, the month he sent a copy to the artist. In it he describes the artist’s working procedures:

He launches into his canvas, when the subject is simple, by tracing with the brush, generally with reddish brown [Jean Renoir refers to burnt sienna], a few very quick guidelines to see the proportions of the elements that will constitute his painting. “Les volumes . . .”, he says a little sarcastically. Then immediately, in pure colors diluted with spirit, as if he were working in watercolor, he rapidly rubs the canvas and one sees something imprecise and iridescent appear, the tones flowing into each other, something that delights you even before it is clear how the image will appear.

What André describes is Renoir’s habit of working quickly with a long handled, fine brush soaked in color thinned with spirits, the way one might use a crayon or pencil. Once the artist applied an initial paint layer, he ended his first session at the canvas. After the underpaint had dried a little, according to André, Renoir returned with more color and applied pure white to the areas he wanted to be luminous. The thin, transparent tones that resulted were the envy of Henri Matisse.

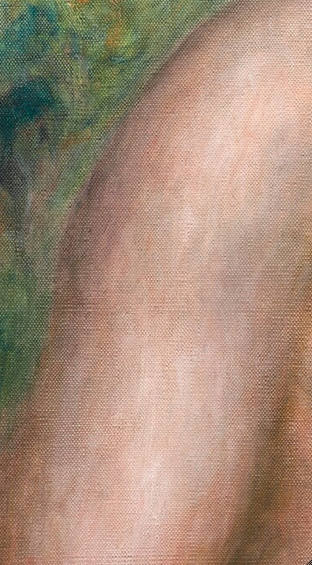

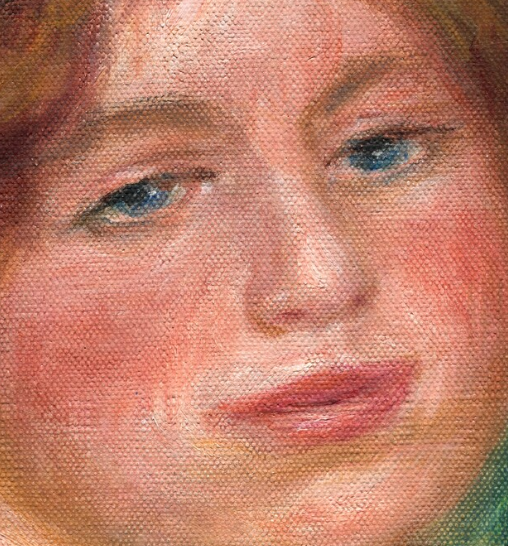

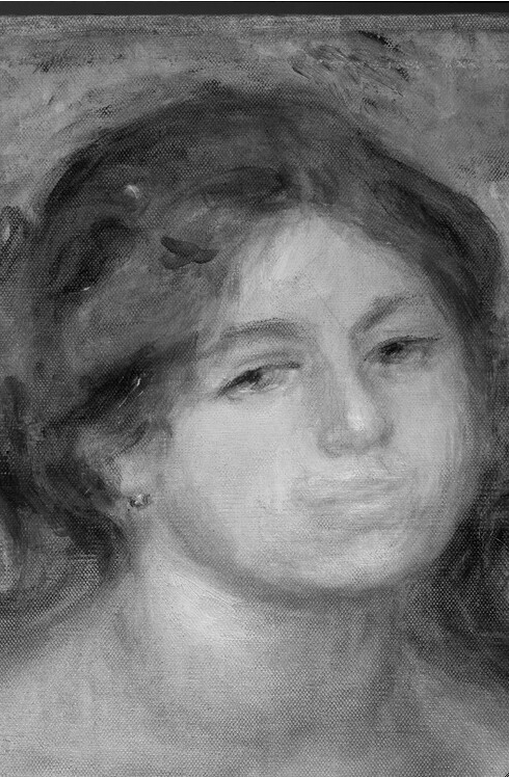

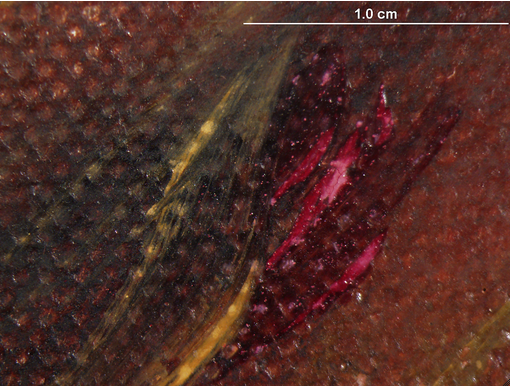

Renoir executed Seated Bather in a manner consistent with André’s description of his working procedure. The paint is quite translucent overall. The flesh tones were blended while they were still in a liquid state. That resulting surface appears to exhibit endless variation in tone. Renoir explained to the American artist and critic Walter Pach his goal as a colorist in painting flesh tones: “I look at a nude; there are myriads of tiny tints. I must find the ones that will make the flesh on my canvas live and quiver.” Additional white highlights in the flesh tones of Seated Bather were also added at a late stage to increase the luminosity (fig. 25.5). Renoir’s extensive use of thin layers of color throughout the painting is further exemplified in the blending of the background foliage. He dragged thin, liquid yellow and green across existing textured strokes in yellow and white; the thinner paint sank into the depressions (fig. 25.6). Areas of layered impasto are evident in the face and hair and are especially conspicuous in the application of yellow over the reddish-brown hair color (fig. 25.7).

While alluding to Greek sculpture with his principal figure in Seated Bather, Renoir placed the painting in a contemporary context by showing the model wearing tiny earrings and with her hair pulled back into a bun, as well as by adding two nudes in the background who appear engaged in typical post-bath activities: drying off with a towel and adjusting one’s hair. The rugged mountainous landscape setting is reminiscent of Provence, the region in the south of France where Renoir lived out his days. The area’s plentiful reminders of a Greco-Roman heritage cannot be underestimated as a potent source for Renoir’s updated vision of antiquity. Although the late style of Renoir is more controlled and classical in its expression of form, Seated Bather demonstrates that, in these last years, he lost nothing of the ingenious blending of color and luminosity that characterizes his earlier Impressionist painting.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Renoir began this work by lightly sketching this composition in graphite on a commercially prepared, standard-size, relatively coarse canvas. The artist reinforced the outlines in some areas several times, and the repeated contours of the figures at the right make specific changes to their placements less obvious. The central figure’s face was lightly sketched prior to painting, unlike the rest of the figure, and Renoir shifted the gaze, lifting her right eye and adjusting her mouth in the final painting. There may also be discrete sketched elements between the paint layers functioning almost like shading, as in the center-right figure. The central figure is largely outlined in reddish-brown paint; it is unclear, however, whether this was an initial planning step or executed later in the painting stage. The paint layer is quite translucent overall, making use of paint thinned with additional oil and turpentine to achieve a very liquid state. The artist also appears to have rubbed areas of the painting with a cloth or his hand, both to wipe back areas of change, as in the figure’s left arm, and to blend the transition between figure and ground. The flesh tones of the central figure appear largely blended via wiping, and the sense of individual brushstrokes seen in the face and the two figures at the right is muted by this method. The painting appears to have been worked up as a whole, with no discrete sequence of execution, and it is currently unvarnished.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 25.8).

Signature

Signed and dated: Renoir. 1914. (lower left, in black or brown paint) (fig. 25.9, fig. 25.10).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

The earliest documented dimensions of the painting are inscribed on the verso of an undated Durand-Ruel photograph of the work: 32 × 26 5/8 in. [81.28 × 67.63 cm]; it is unclear whether these measurements predate the lining. Measuring from the apparent foldovers on all four sides, the original dimensions appear to be approximately 80 × 66.5 cm. This probably corresponds to a no. 25 portrait (figure) standard-size (81 × 65 cm) canvas.

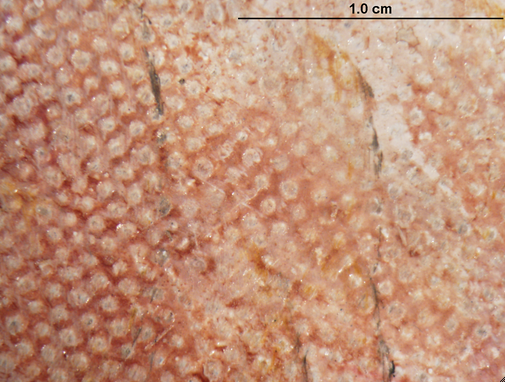

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 16.8V (0.3) × 12.0H (0.5) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft.

Canvas characteristics

Cusping is most visible in the X-ray and it present only on the sides, where it is relatively pronounced; it appears to correspond to tack holes along the foldover placed approximately 5–7cm apart. Tacks along the edges of the compositional space would not have functioned to attach the work to a stretcher and may indicate the work was removed from its stretcher, or had another secondary support such as a board (fig. 25.11).

Stretching

Current stretching: The work was restretched as part of the 1953 lining, and the perimeter was extended on all sides.

Original stretching: Uncertain; may have been tacked to a board or on the face of a stretcher during or immediately after execution.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Five-member keyable stretcher with horizontal crossbar. Depth: 2.3 cm.

Original stretcher: Unknown.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

No manufacturer’s or supplier’s marks were observed during the current examination or documented in previous examinations.

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

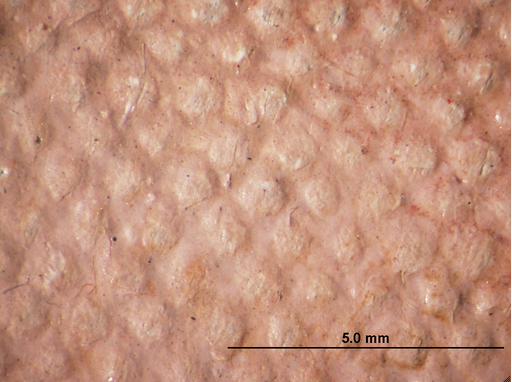

Ground application/texture

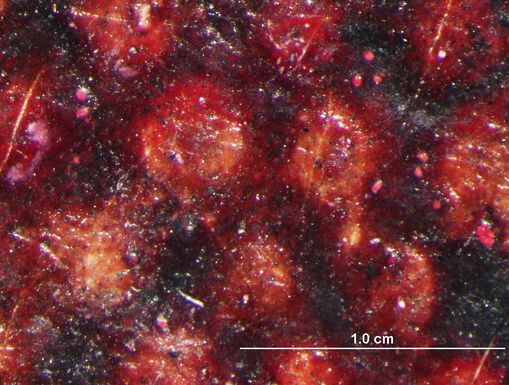

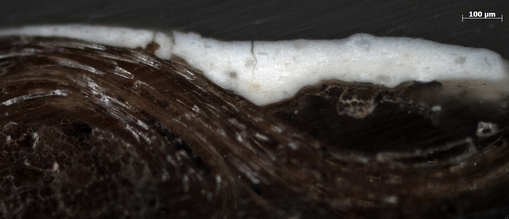

A single-layer commercial preparation extends to the edges of the tacking margins, is relatively smooth, and ranges approximately 25–160 µm in thickness. Interestingly, the ground appears very thin across the tops of the canvas threads, in some cases not coating the threads enough to mask the sense of individual fibers within the thread even under additional paint (fig. 25.12). The thinness of the ground in combination with the artist’s rubbing and wiping of the paint layer left thread tops exposed in many areas; these are especially sensitive and prone to additional abrasion.

Color

The ground appears to be a dull white in stereomicroscopic examination, however cross-sectional analysis revealed no colored pigments to be present (see Materials/composition). Also, the pigment and medium content do not suggest the ground to be a translucent or semi-translucent layer easily affected by treatments such as lining (fig. 25.13). With these facts in mind, it is not entirely clear whether this current appearance is due to the quality or manufacture of the ground materials themselves or possible discoloration from another unknown source. As the painting is currently unvarnished and was recently cleaned, these visual affects cannot be attributed to surface coatings or grime (see Conservation History) (fig. 25.14).

Materials/composition

The ground is predominantly lead white with trace amounts of alumina, silica, calcium carbonate and various complex silicates, some containing iron. The binder is estimated to be oil.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

There is a very sketchy underdrawing of the figures at right and of the face of the central figure, marked by a lack of fine detail and executed with an unsteady hand. The nature of the drawing suggests broad movement of the artist’s arm, with sweeping contours and repeated movements, especially for the figures on the right (fig. 25.15). Limited drawing of the central figure’s face is more distinct, though these lines also show a lack of fine detail. The lines themselves were lightly applied, and their direction is often affected by the canvas weave; in some places, the graphite only skimmed the thread tops or was thrown in a different direction by the bumpy texture of the weave. There are periodically stray graphite lines that do not appear to correspond to specific forms, such as the diagonal across the central figure’s forehead.

Medium/technique

Graphite.

Revisions

The roughness and uncertain quality of the sketch make smaller changes less discernable; however, it does appear that Renoir shifted the level of the eyes and modified the placement of the figures at the right (fig. 25.16).

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

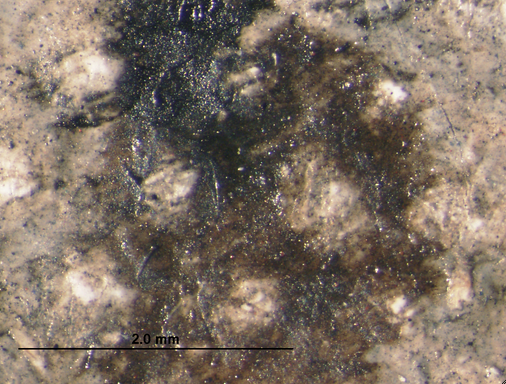

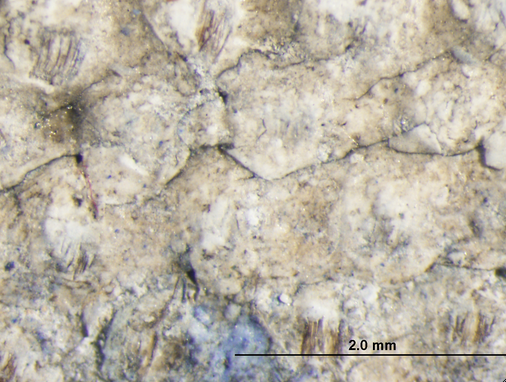

This painting is executed in a series of layered washes and semi-glazes with limited impasto. It appears that Renoir’s paint was quite fluid, thinned with solvent or a solvent/oil mixture and often rubbed back with a cloth or possibly his hand so that the color sits mostly in the interstices of the canvas with the appearance of a stain. The X-ray shows very little of the visible composition, as the paint is so thin in most areas that only the overall ground and lighter, thicker highlights register. In some areas, the artist layered this rubbing over an existing color. In the background, for example, a thin layer of green was applied and allowed to dry, over which the artist applied thin reds and yellows, wiping them back to reveal the green painted thread tops (fig. 25.17). In other areas, the underlying paint was quite thick and textured when he added a thin veil of contrasting color (fig. 25.18). Renoir also dragged thicker paint of a pastelike consistency across thin underpaint so that only the crests of the weave are coated creating a kind of contrast effect (fig. 25.19). The artist reserved oil-rich glazes for specific sections of the figure’s hair and upper eyelids, combining red lake with black to create deep-crimson shadows (fig. 25.20); a slight saturation and gloss is still present in these shadows despite a lack of varnish.

Renoir’s most prominent use of rubbing or wiping appears in his modeling of the central figure. Comparing her flesh tones to those of the figures at right, the central figure appears smoother, with many tones indistinctly blended and an earthy, reddish-brown outline. The artist applied many colors side by side throughout this figure’s flesh, and wiped or rubbed them in their still-liquid state to create smooth modeling and to blur the figure-ground transition. Some distinct brushwork is still visible in the thicker paint of this figure’s face.

This fluid technique yielded a painting that appears to have been worked up as a whole, with the transitions between figure and ground very smooth and sometimes rubbed; the sequence of forms is indistinct. Once the general elements were articulated, the artist went back into specific areas to add details. He also wiped back the paint to make subtle compositional changes, such as the outer edge of the figure’s right arm (fig. 25.21). Layers of translucent washes and glazes make up the hair, while a fine brush with thicker paint was employed for final details such as the eyes (fig. 25.22). In some areas, it appears that Renoir sketched additional lines between and above painted layers; the lines along the back of the center-right figure function almost like hatched shading (fig. 25.23). The presence of impasto in some of the lower layers indicates Renoir executed the painting in multiple sessions, allowing the earlier layers to dry between campaigns. While limited impasto is visible beneath the surface, in many areas it was added as a final touch, as in the white highlights in the drapery.

Painting tools

Fine, soft-bristle brushes; limited stiff-bristle, flat brushes (strokes up to 1 cm wide); possible cloth for rubbing; graphite.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, zinc white, red lake, vermilion, bone black, viridian, terre verte, cobalt blue, Naples yellow, yellow ochre, and possibly zinc yellow.

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting is currently unvarnished with no residues of previous varnish layers.

Conservation History

The painting was damaged while on loan in 1952 and cut from its stretcher; it was subsequently lined in 1953. In 1972 the painting was noted as being abraded and having a heavy, discolored natural resin varnish. The work was cleaned of grime and given a synthetic varnish of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) AYAA. In 2004–05 the work was cleaned and all varnish layers and retouching was removed. The tear and some additional abrasion were minimally retouched, and after examination of related paintings, the painting was left unvarnished.

Condition Summary

The work is in stable condition, planar and aqueously lined and unvarnished. During the lining process, it was attached to the stretcher slightly askew, so that a small amount of compositional paint is bent over the bottom edge at left. There is a series of small holes in the canvas along the foldovers on both sides. Retouching is limited to areas of abrasion and the tear resulting from the 1952 damage. The work has an overall abraded appearance due to age, previous treatments and the artist’s rubbing technique. There are a few localized superficial creases at the lower left and over the figure’s right hand.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

Current frame (installed after 1975): The frame is not original to the painting. It is an American (APF Master Frame Makers, New York), mid-twentieth-century, Louis VI reproduction, architrave frame with carved rolled-leaf-and-stave ornament and a lozenge-and-bead sight molding. The frame has oil and water gilding over red bole on gesso with induced craquelure. The white gold gilding is burnished selectively on the ornament and fillet. The gilding is heavily rubbed and toned with washes of oil paint and casein or gouache with dark flecking overall. The basswood molding is mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is fillet; torus with carved rolled-leaf-and-stave ornament; fillet; and lozenge-and-bead sight molding (fig. 25.24).

Previous frame (installed by 1975, removed at an unknown date): The work was previously housed in an American, mid-twentieth-century, L-shaped narrow frame with a gilded face on a mahogany molding with exposed splines at the miters (fig. 25.25). The frame may have been a design by James L. Speyer.

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Placed on deposit by the artist with Durand-Ruel, Paris, Aug. 1914.

Sold by the artist jointly to Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, Ambroise Vollard, Paris, and Durand-Ruel, Paris, Aug. 2, 1917.

All shares transferred from Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, and Ambroise Vollard, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Oct. 2, 1917.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to the Art Institute of Chicago, Feb. 23, 1945.

Exhibition History

New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 19–Mar. 9, 1918, cat. 16, as Baigneuse assise, 1914.

Possibly New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by the Master Impressionists, Oct. 15–Nov. 10, 1934, cat. 27.

Museum of Modern Art Gallery of Washington (D.C.), Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Renoir, Van Gogh, Nov. 15–Dec. 5, 1937, cat. 19.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Renoir: Later Phases, Apr. 16–May 29, 1938, no cat.

Worcester (Mass.) Art Museum, The Art of the Third Republic: French Painting, 1870–1940, Feb. 22–Mar. 16, 1941, cat. 11 (ill.).

New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Masterpieces by Renoir after 1900: For the Benefit of Children’s Aid Society, Apr. 1–25, 1942, cat. 10 (ill.).

New York, Museum of Modern Art, Art in Progress: Painting, Prints, Sculpture, May 24–Oct. 15, 1944, no cat. no. (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpiece of the Month, Feb. 1946, no cat.

Cincinnati Art Museum, Paintings: 1900–1925, Feb. 2–Mar. 4, 1951, cat. 4 (ill.).

Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, French Painting, 1110–1900, Oct. 18–Dec. 2, 1951, cat. 118 (ill.).

Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne, L’oeuvre du XXe siecle, May–June 1952, cat. 93 (ill.); London, Tate Gallery, as Twentieth Century Masterpieces: An Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, July 15–Aug. 17, 1952 (Paris only).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 84 (ill.).

London, Hayward Gallery, Renoir, Jan. 30–Apr. 21, 1985, cat. 121 (ill.); Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, May 14–Sept. 2, 1985, cat. 119 (ill.); Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Oct. 9, 1985–Jan. 5, 1986.

Atlanta, High Museum of Art, Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, Oct. 16, 2007–Jan. 13, 2008, cat. 90 (ill.); Denver Art Museum, Feb. 23–May 25, 2008; Seattle Art Museum, June 19–Sept. 21, 2008.

Paris, Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Renoir au XXe siècle, Sept. 23, 2009–Jan. 4, 2010, cat. 62 (ill.); Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as Renoir in the 20th Century, Feb. 14–May 9, 2010; Philadelphia Museum of Art, as Late Renoir, June 17–Sept. 6, 2010.

Selected References

Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1918), p. 3, cat. 16.

Gustave Coquiot, Renoir (A. Michel, 1925), opp. p. 216 (ill.).

Possibly Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings by the Master Impressionists, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1934), cat. 27.

Edward Alden Jewell, “Gallery to Open in Capital Today,” New York Times, Nov. 14, 1937, p. 51.

Museum of Modern Art Gallery of Washington (D.C.), Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Renoir, Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Museum of Modern Art Gallery of Washington, [1937]), no. 19.

Martha Davidson, “Poetic View of the Late Renoir,” Art News 36, 31 (Apr. 30, 1938), p. 22.

Worcester Art Museum, Art of the Third Republic: French Painting, 1870–1940, exh. cat. (Worcester Art Museum, 1941), cat. 11 (ill.).

Edward Alden Jewell, “21 Renoir Works Shown as Benefit,” New York Times, Apr. 2, 1942, p. 28.

Edward Alden Jewell, “The Last Two Decades of Renoir,” New York Times, Apr. 5, 1942, p. X5 (ill.).

Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Masterpieces by Renoir after 1900: For the Benefit of Children’s Aid Society, with an essay by Lionello Venturi, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1942), no. 10 (ill.).

Museum of Modern Art, New York, Art in Progress: A Survey Prepared for the Fifteenth Anniversary of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, exh. cat. (Museum of Modern Art, 1944), pp. 23 (ill.), 223.

“Chicago Perfects Its Renoir Group,” Art News 44, 16, pt. 1 (Dec. 1–14, 1945), pp. 18, 19 (ill.).

“Famous Renoir Nude Goes to Chicago.” Art Digest 20, 6 (Dec. 15, 1945), p. 6 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, An Illustrated Guide to the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1945), p. 36 (ill.).

Florence Hope, “A Late Renoir Recently Added to the Institute’s Collection,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 39, 7 (Dec. 1945), front cover (ill.), pp. 99, 100 (detail), 101.

John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (Museum of Modern Art/Simon & Schuster, 1946), p. 429 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, “Exhibitions,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 40, 1 (Jan. 1946), p. 2.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Exhibitions,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 40, 2, pt. 2 (Feb. 1946), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Do You Know,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 40, 3 (Mar. 1946), p. 32.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Great Drawings and Paintings Added in 1945,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago: The Year 1945 40, 4, pt. 3 (Apr.–May 1946), p. 6 (ill.).

“Vernissage,” Art News 44, 18 (Jan. 1–14, 1946), p. 11.

“Art News of the Year,” in “Art News Annual 1946–47,” special issue, Art News 45, 10, section 2 (Dec. 1946), p. 161 (ill.).

Carnegie Institute, French Painting, 1110–1900, exh. cat. (Carnegie Institute, 1951), pl. 118.

Cincinnati Art Museum, Paintings: 1900–1925, exh. cat. (Cincinnati Art Museum, 1951), cat. 4 (ill.).

Musée National d’Art Moderne, L’oeuvre du XXe siècle, exh. cat. (Musée National d’Art Moderne, 1952), cat. 93/pl. 8.

“Youths Caught Stealing Famous Paintings in Paris,” New York Times, June 28, 1952, p. 11.

Marcelle Berr de Turique, Renoir (Phaidon, [1953]), pl. 98.

Dorothy Bridaham, Renoir in the Art Institute of Chicago (Conzett & Huber, 1954), pl. 9.

Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study of Ideal Art (John Murray, 1957), pp. 159; 160, ill. 123.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 398.

George Heard Hamilton, Painting and Sculpture in Europe: 1880–1940, Pelican History of Art, ed. Nikolaus Pevsner (Penguin, 1967), pp. xi; 14; pl. 4B.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World, 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 128, pl. 116; 177.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 27; 194–95, cat. 84 (ill.); 202; 211; 214.

A. James Speyer and Courtney Graham Donnell, Twentieth-Century European Paintings (University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp. 12, 66, cat. 3E11; microfiche 3, no. E10 (ill.).

Hayward Gallery, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Renoir, exh. cat. (Arts Council of Great Britain, 1985), pp. 173, cat. 121 (ill.); 285; 286, cat. 121 (ill.); 288; 289.

Hayward Gallery, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Renoir, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), pp. 348; 350–53, cat. 119 (ill. and detail); 360.

Rachel Barnes, ed., Renoir by Renoir, Artists by Themselves (Webb & Bower, 1990), pp. 72–73 (ill.). Translated into Japanese by Reiko Kokatsu as Runowaru (Renoir), Nikkei Pocket Gallery (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 1991), pp. 78–79 (ill.), 88.

Martha Kapos, ed., The Impressionists: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, 1991), p. 232, pl. 72.

Romy Golan, Modernity and Nostalgia: Art and Politics in France between the Wars (Yale University Press, 1995), pp. 19, 20–21 (ill.).

Steven Kern, “A Passion for Renoir,” in A Passion for Renoir: Sterling and Francine Clark Collect, 1916–1951, ed. Margaret Donovan, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Institute/ Abrams, 1996), p. 24.

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 13; 74; 77–79; 107, pl. 26; 111.

Renaud Temperini, “Estetiche della modernità,” in La pittura Francese, vol. 3, ed. Pierre Rosenberg, trans. Cosima Campagnolo, Valentina Palombi, and Stefano Salpietro (Electra, 1999), p. 821.

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), pp. 340 (ill.), 341 (detail), 342.

Aviva Burnstock, Klass Jan van den Berg, and John House, “Painting Techniques of Pierre-Auguste Renoir: 1868–1919,” Art Matters: Netherlandish Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005), p. 52.

Markus Schöb, “Femme s’essuyant,” in Kunstmuseum Winterthur: Katalog der Gemälde und Skulpturen, vol. 2, ed. Dieter Schwarz (Kunstmuseum Wintherthur/Richter, 2008), pp. 60, 61 (ill.)

Ann Dumas, “Old Art into New: The Impressionists and the Reinvention of Tradition,” in Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, ed. Ann Dumas, exh. cat. (Denver Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 71; 74–75, cat. 90 (ill.).

Ann Dumas, ed., Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, exh. cat. (Denver Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2007), p. 261.

Jon Kear, The Treasures of the Impressionists (Andre Deutch/Carlton Books, 2008), p. 56 (ill.).

Anne Distel, Renoir (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2009), p. 366, ill. 324.

Adrien Goetz, Comment Regarder . . . Renoir (Hazan, 2009), pp. 168–69 (ill).

Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir au XXe siècle, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2009), pp. 296–97; 301, cat. 62 (ill.).

Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir in the 20th Century, with essays by Roger Benjamin, Guy Cogeval, Claudia Einecke, Isabelle Gaëtan, et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Philadelphia Museum of Art/Hatje Cantz, 2010), pp. 296–97; 301, cat. 62 (ill.).

Laurence Madeline, “Picasso 1917–1924: Une crise ‘renoirienne,’” in Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir au XXe siècle, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2009), p. 128.

Laurence Madeline, “Picasso 1917 to 1924: A ‘Renoirian’ Crisis,” in Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir in the 20th Century, with essays by Roger Benjamin, Guy Cogeval, Claudia Einecke, Isabelle Gaëtan, et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Philadelphia Museum of Art/Hatje Cantz, 2010), p. 128.

Sylvie Patry, “‘On doit faire la peinture de son temps,’” in Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir au XXe siècle, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2009), p. 360.

Sylvie Patry, “‘One Must Do the Painting of One’s Time,’” in Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir in the 20th Century, with essays by Roger Benjamin, Guy Cogeval, Claudia Einecke, Isabelle Gaëtan, et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Philadelphia Museum of Art/Hatje Cantz, 2010), p. 360.

Sylvie Patry, “Renoir et la décoration, ‘un plaisir sans pareil,’” in Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir au XXe siècle, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2009), pp. 55.

Sylvie Patry, “Renoir and Decorative Art: ‘A Pleasure without Compare,’” in Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir in the 20th Century, with essays by Roger Benjamin, Guy Cogeval, Claudia Einecke, Isabelle Gaëtan, et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Philadelphia Museum of Art/Hatje Cantz, 2010), p. 56.

Thomas Schlesser, “Renoir et sa dernière manière, les figures,” in “Renoir au XXe siècle: Exposition aux Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais,” ed. Jeanne Faton-Boyancé, special issue, L’estampille l’object d’art 46 (2009), p. 48 (ill.).

Martha Lucy and John House, Renoir in the Barnes Foundation (Barnes Foundation/Yale University Press, 2012), p. 181, fig. 1.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 5, 1911–1919 & Ier supplément (Bernheim-Jeune, 2014), pp. 387–88, cat. 4280 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Bernheim-Jeune Documentation

Inventory number

Bernheim-Jeune stock no. 20940

Photograph number

Photo Berhnheim-Jeune no. 1846

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel, New York, 4107

Photograph number

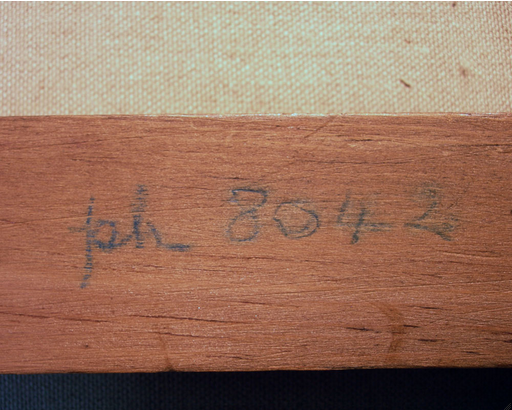

Photo Durand-Ruel New York 8042

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel New York a1636

Other Documents

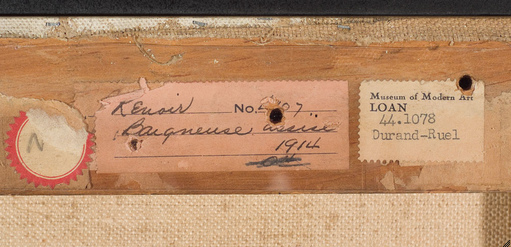

Inscription (fig. 25.26)

Inscription (fig. 25.27)

Label (fig. 25.28)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Number

Location: original canvas tacking margin

Method: hand-painted script (black)

Content: 45.27 (fig. 25.29)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite) on red and white circular label

Content: N [. . .] (fig. 25.30)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

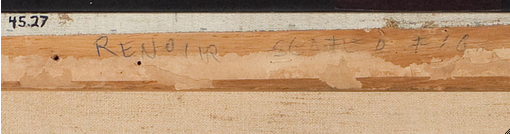

Content: RENOIR SEATED FIG (fig. 25.31)

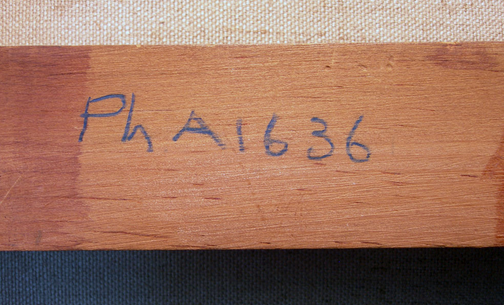

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue pencil)

Content: PhA1636 (fig. 25.32)

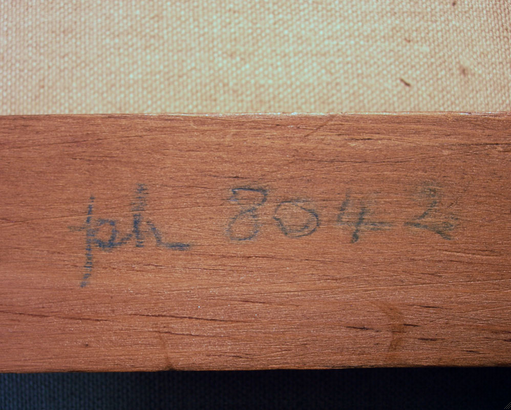

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (blue pencil)

Content: Ph 8042 (fig. 25.33)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: red stamp

Content: Ä [superimposed]• (fig. 25.34)

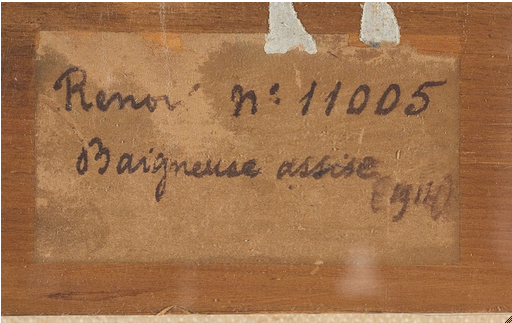

Pre-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (ink) on brown paper label

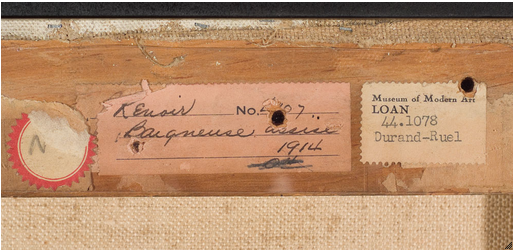

Content: Renoir no. 11005 / Baigneuse assise / (1914) (fig. 25.35)

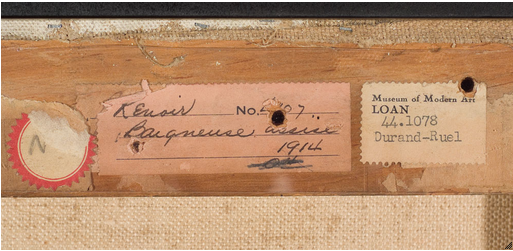

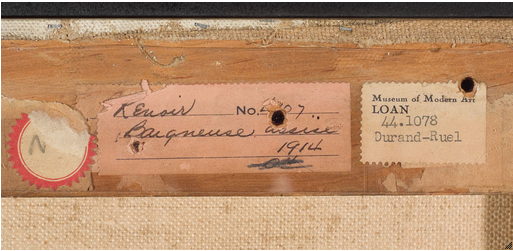

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: typed label

Content: Museum of Modern Art / LOAN / 44.1078 / Durand-Ruel (fig. 25.36)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script on printed label

Content: Renoir No. [ ] 07 / Baigneuse assise / 1914 / [crossed-out script] (fig. 25.37)

Post-1980

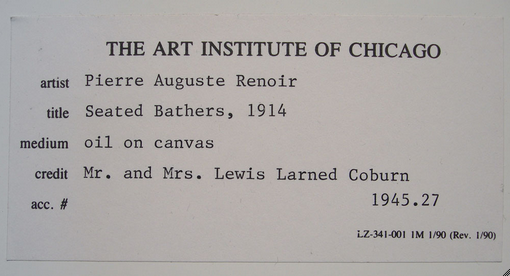

Label

Location: backing board

Method: typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Pierre Auguste Renoir / title Seated Bathers, 1914 / medium oil on canvas / credit Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn / acc. # 1945.27 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 25.38)

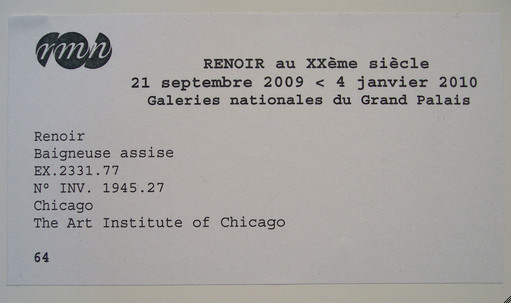

Label

Location: backing board

Method: digitally printed label

Content: rmn [logo] / RENOIR au XXème siècle / 21 septembre 2009 < 4 janvier 2010 / Galeries nationales du Grand Palais / Renoir / Beigneuse assise / EX. 2331.77 / No INV. 1945.27 / Chicago / The Art Institute of Chicago / 64 (fig. 25.39)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (Kodak Wratten 2E filter and PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter)

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

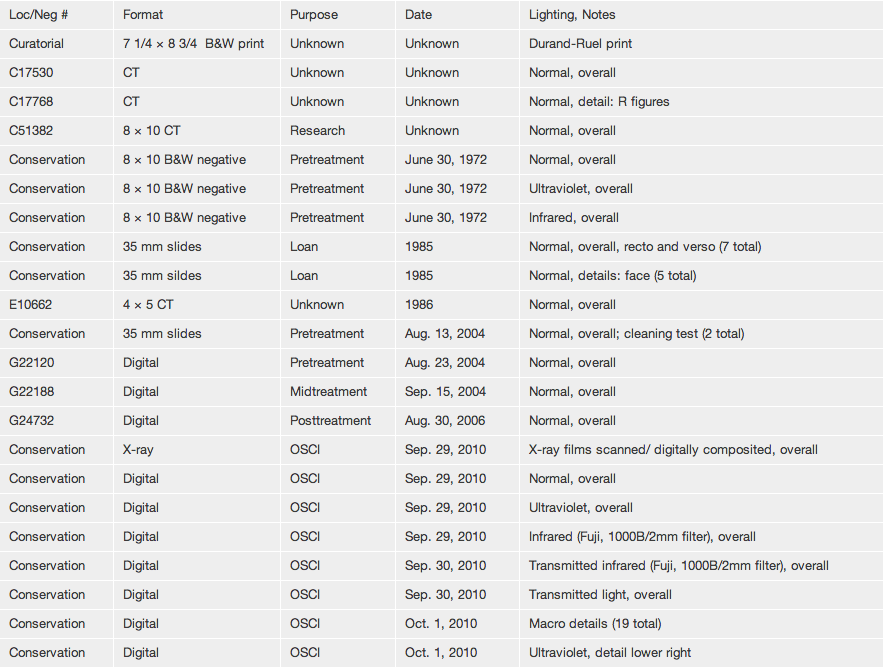

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 25.40).