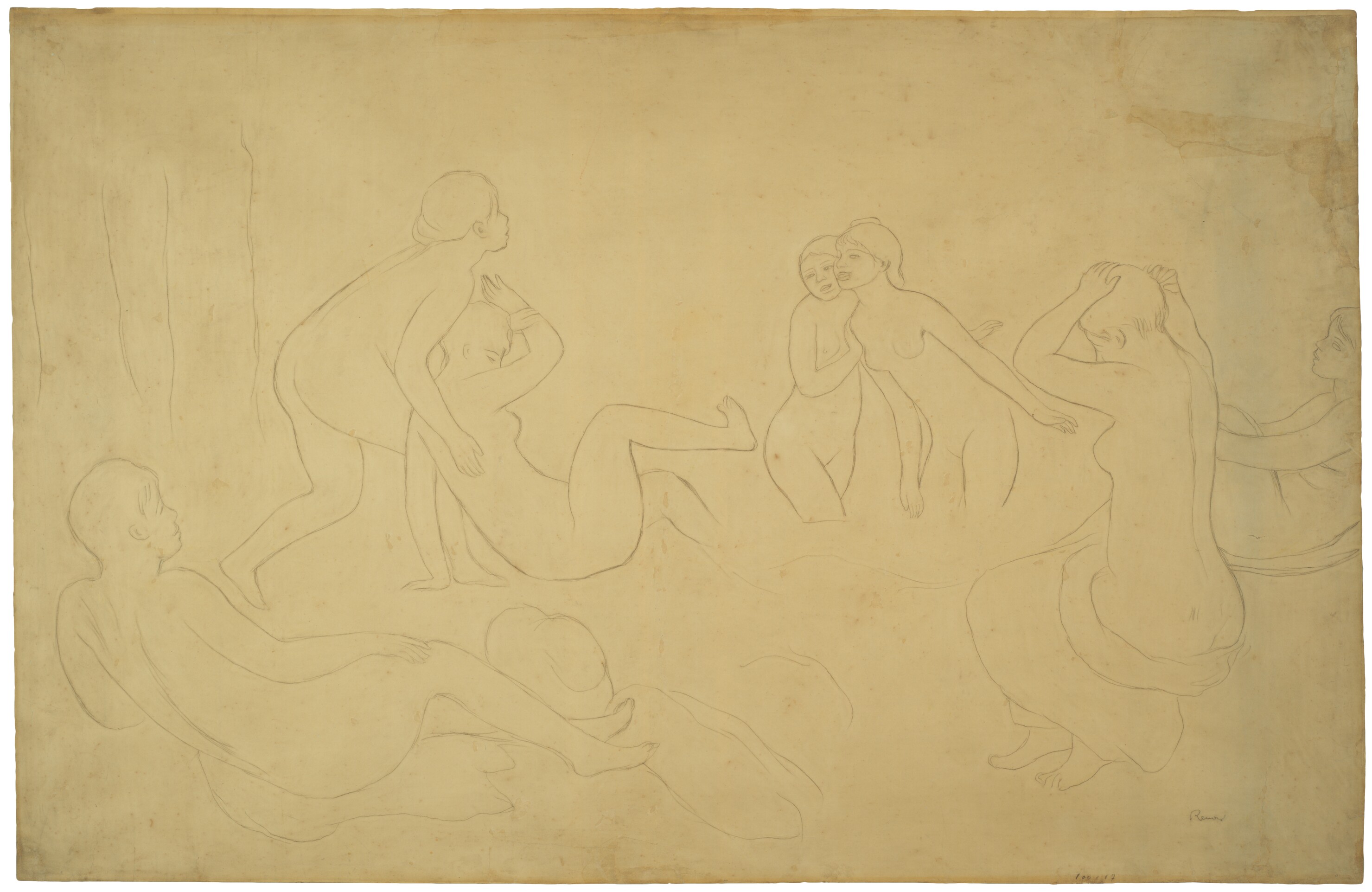

Cat. 23

Study for “Bathers in the Forest,”

1895/97

Graphite, on tan wove paper, laid down on ivory Japanese paper; 638 × 944 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Dorothy Braude Edinburg to the Harry B. and Bessie K. Braude Memorial Collection, 2013.1010

Executed on very thin paper that exhibits signs of studio wear and tear, Study for “Bathers in the Forest” is clearly one of Renoir’s working drawings. It bears a close relationship to the painting Bathers in the Forest, in the collection of the Barnes Foundation, executed around 1897 (fig. 23.1 [Dauberville 2407]). Curiously, however, the Art Institute’s sheet does not appear to have served in the genesis of that work. Instead of showing signs of alterations and edits, as would be customary for a preparatory study, its composition is almost identical. Bathers in the Forest might be a tracing from the finished painting. Art Institute paper conservator Kimberly Nichols has compared the lines of the sheet with a scaled image of the painting and found that the placement of the figures is remarkably similar (see Technical Report). The facial features are also very similar; movement of the paper during the tracing process could account for the slight degree of variation.

If the present drawing is a tracing, it might explain Renoir’s choice of graphite, which adheres to a wet support. As the sheet’s uneven surface indicates, it was wetted at some point probably before Renoir committed the image to paper. Dampening the sheet would have made it malleable enough to stretch across the canvas; it could also have offered the transparency Renoir would have needed to view the original composition through the sheet. Once dry, unlike conventional tracing paper, the page would have withstood reworking. Little patches of abrasion, tears, and pinholes at its edges offer further evidence that the thin sheet was not destined for formal display (see Technical Report).

All of this makes for an image that is idiosyncratic in Renoir’s oeuvre. More typically, in his drawings, the artist’s line was intricate (as in his Workers’ Daughters on the Outer Boulevard [cat. 5] [Dauberville 664]) or soft (as in his Splashing Figure [cat. 19] [Dauberville 1517]). Here, in contrast, the pencil marks are firm and inexpressive. This, too, suggests that the function of the drawing was primarily practical. As a record of the Barnes Foundation’s Bathers in the Forest, Renoir could have kept the Art Institute’s work as a point of reference for future variations on the theme. Given that the campaign was something of a return—the artist had made an important series of bathers some ten years previously—such a plan would seem logical. Indeed, in an article on the subject of the earlier series, Barbara Ehrlich White argued that Renoir traced works to develop compositions in the mid-1880s.

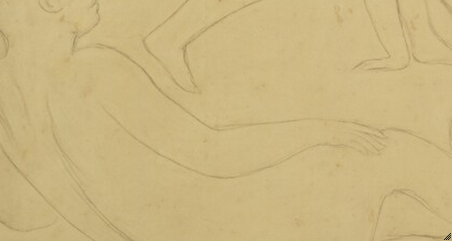

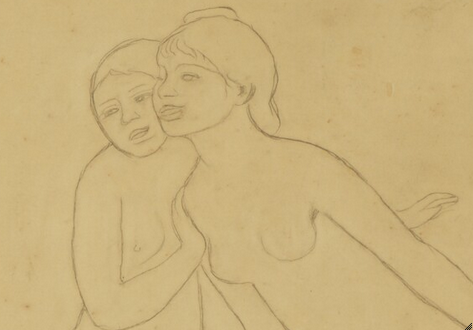

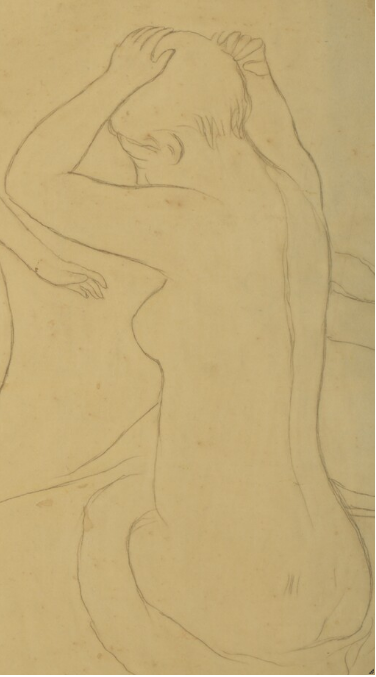

The content of the scene is rather curious. In a clearing, created by the tree trunks to the left, young women rest and play. The arrangement is highly implausible as a real-life scenario that Renoir could have observed (although he did claim that, when he traveled to Guernsey in the Channel Islands in the early 1880s, men and women bathed together in the nude). The drawing’s characters range from the woman fixing her hair at right in the foreground (seated on drapery and seemingly unaware of the viewer) to a rather androgynous youth who lounges beside the water (although, in the painting, the figure is obviously female). Two girls at center-right collude to splash their companions, and one shields her face in anticipation of the water. Even in the Barnes Foundation canvas, which clarifies the context and is unified by evenly dispersed touches of color, the relationships among the women look staged. The backs of the outlying figures, balanced by the overhanging branches, form a frame of sorts.

The poses of the recoiling woman and the companion who cups a hand over her shoulder seem to be adapted from those in the famed Diana and Actaeon that Titian painted around 1556–59 for King Phillip II of Spain (fig. 23.2). The two indications of tree trunks in the background also appear in comparable places. The figures in Renoir’s composition are reversed, however, so he probably knew the work from a print. Critics and scholars have long connected the artist with the Old Masters he admired, and in the Barnes canvas the soft, jewel-like shades, applied with a fluid virtuosity, do seem to owe something to Venetian precedents. It is worth recalling that one of Renoir’s earliest large-scale works was on the theme of Diana the huntress (fig. 23.3 [Daulte 30; Dauberville 578]).

Nonetheless, if Renoir’s choice of the bathers motif was historicizing, it did not constitute a retreat from the contemporary world. Instead, as John House has argued, it revealed Renoir’s sympathies with then-current idealizations of prerevolutionary France. The earthy, rounded models in Bathers in the Forest are the antithesis of the emaciated urban girls that had featured in Impressionist works of the 1870s (such as the Parisienne; fig. 23.4 [Daulte 102; Dauberville 299]). Similarly, at the end of the nineteenth century, the countryside itself seemed to offer an escape from the apparent depravity of the city.

House posited that Renoir’s dissatisfaction with late-nineteenth-century female emancipation is discernible in his Large Bathers (fig. 23.5 [Daulte 514; Dauberville 1292]). In an age in which women enjoyed increased social freedom, the models in that image inhabit an impossibly small space, which comes under the surveillance of the male viewer. The same seems true of Bathers in the Forest, although here Renoir set the women at a distance from the onlooker. This last observation might lend a further dimension to Renoir’s visual quotation of Diana and Actaeon. If in Ovid’s account Actaeon was seen and punished by the goddess for his voyeurism, in Renoir’s drawing the viewer observes the beauties undisturbed, shielded by the lounging figure in the foreground.

Nancy Ireson

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Study for “Bathers in the Forest,” was a drawn directly in graphite on a tan, smooth, machine-made wove paper. The uniform surface of the paper enabled the graphite to glide across in uninterrupted lines. The figures in the composition form a circular arrangement, and the drawing is virtually absent of background development. Only the slightest suggestion of water intersects the figure’s thighs in the center, and two vertical lines suggest trees at the upper left. The graphite lines are deliberate, laid down as if the forms and composition were already conceived. There is no reworking, but the lines are drawn over one another to reinforce or work over the figural contours (fig. 23.6). Faint erasure is visible on both sides of most drawn lines, and was possibly done to remove the transfer of loose graphite particles across the paper and sharpen the lines (fig. 23.7). It is unclear, however, whether the erasure is an original artistic gesture or a later restoration. There is no modeling in the figures, either from erasure or stumping; only a few lines suggest shadows along the figure’s spines and shoulder blades (fig. 23.8). Although there are no significant compositional changes, the features of the figure on the far right may have been slightly altered. The drawing exhibits extensive structural breaks and losses, as well as pinholes, evidence of its use as a working drawing.

As a digital image overlay (fig. 23.9) has shown, the composition of the drawing matches that of the painting Bathers in the Forest (c. 1897; Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia). Not only do the general figural arrangements correspond, but the figural details (such as facial features, limbs, and toes, as well as the shading along the figure’s spine at the right side) relate as well. There is a slight shift in the relative compositional relationship at the far right, but the subjects remain similar in scale and detail, and the shift can be accounted for by adjusting the overlay slightly from side to side. The almost complete correspondence between the two works and the deliberate placement of line in the drawing suggest that the drawing was either used for transfer to the canvas or made after the painting, as a tracing, possibly for documentation or technical experimentation. There is no indication of pricking or embossing to confirm that the drawing was used for transfer; nor is there clear evidence of transfer material on the verso. In addition, an infrared reflectography (IRR) capture of the oil painting reveals no evidence of graphite (in either an underdrawing or a transferred drawing) to confirm a relationship between the drawing and the painting. In fact, the infrared reflectogram identified features in the early stages of the painting composition that are present neither in the finished painting nor the drawing. It thus seems most likely that the drawing documents the finished painting composition, perhaps part of the artist’s technical process.

Signature

Renoir (lower right, in graphite) (fig. 23.10).

Media and Support

Support Characteristics

Primary paper type

Tan, medium thick, smooth wove paper.

Furnish

Uniform, without visible inclusions or colored fibers.

Formation

Even, machine made.

Other characteristics

All edges are trimmed straight.

Dimensions

638 × 984 mm.

Secondary support

Ivory, medium-thick, slightly textured Japanese paper lining. Dimensions: 69.0 × 103.0 cm.

Preparatory Layers

No artistic surface alterations or coatings are visible under normal conditions or under magnification. Under UV illumination, there is a pale-yellow visible-light fluorescence overall on the paper surface that is characteristic of a light gelatin surface sizing; the fluorescence is most pronounced around the perimeter of the paper sheet where the window mat protected it from exposure to light.

Media Characteristics

The work was drawn directly in graphite, with lines laid over one another to strengthen the figural contours. Faint erasure is visible on both sides of most of the drawn lines and was presumably done to reduce graphite migration and sharpen the lines.

Compositional Development

No significant revisions or changes to the composition are visible under normal conditions, UV illumination, or magnification. It is possible that some features in the faces of the figures at the far right and third from the right were altered slightly. Overall, the drawn lines are deliberate, as if already conceived.

Surface Treatment

No artistic surface fixatives or coatings are visible under normal conditions, UV illumination, or magnification. A light gelatin sizing is visible under UV illumination.

Condition History

The drawing support exhibits ingrained surface soiling or media that imparts a streaked appearance overall; there is a prominent dark streak that runs vertically along the left side on the verso. The soiling or grayish-blue material is faintly visible overall, although most concentrated in the upper area, and may have resulted from exposure to moisture during the artist’s use. The material is absent along the top edge, possibly due to a former attachment. A few pinholes are also present at the upper and lower sides and center bottom and top edges are likely evidence of use or artistic process.

The paper exhibits pronounced structural damage, including numerous breaks and losses throughout that may also have resulted from use. The losses vary in size and may be the result of insect damage or removal of a former mount; they are filled with wove paper of a slightly darker tone than the drawing support. These losses are most visible under UV radiation, as they strongly absorb visible light and appear dark. The upper right corner exhibits the most significant area of damage, with large losses, breaks, and possibly reattachment of a darkened fragment. The overall work is supported on the verso with a Japanese paper lining that was joined vertically through the center; the lining has delaminated in large areas through the center, and there are undulations around the perimeter of the sheet. In general, the pattern of structural damage and streaks of soiling, particularly along the right side, suggests that the work may have been stored rolled at one point, receiving its greatest damage at the outermost exposed right edge. The support is discolored overall, most visibly within the window mat (where it was exposed to light) and along the bottom edge, and there are reddish brown stains or foxing, concentrated around the perimeter.

A surface material in the upper right corner emits a faint, white visible-light fluorescence under UV illumination; this is likely a masking material that was applied over the damaged areas. The top edge also emits a yellowish-orange visible-light fluorescence, possibly due to a former adhesive layer.

Kimberly Nichols

Provenance

Sold, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, Jan. 31, 1966.

Galerie Robert Schmit, Paris, by 1985.

Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, Paris, by April 1985.

Grob Gallery, London, by September 1990.

Sold, Sotheby’s, London, Dec. 3, 1991, lot 28, to Dorothy Braude Edinburg.

Given by Dorothy Braude Edinburg to the Art Institute of Chicago, 2013.

Exhibition History

Paris, Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, Dessins et aquarelles de Renoir, Apr. 25–June 30, 1985, cat. 17; Artis Monte-Carlo, July 18–Sept. 14, 1985.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir: The Great Bathers, Sept. 3–Nov. 25, 1990, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Drawings in Dialogue: Old Master through Modern; The Harry B. and Bessie K. Braude Memorial Collection, June 3–July 30, 2006, cat. 103 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, The Thrill of the Chase: Drawings for the Harry B. and Bessie K. Braude Memorial Collection, Mar. 15–June 15, 2014, no cat.

Selected References

Ambroise Vollard, La vie et l’oeuvre de Pierre Auguste Renoir (L’auteur, 1919), p. 271 (ill.).

Paul Haesaerts, Renoir: Sculptor (Reynal & Hitchcock, 1947), pp. 11 (detail ill.), 20 (detail ill.).

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), p. 18 (ill.).

Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, Dessins et aquarelles de Renoir, exh. cat. (Galerie Hopkins-Thomas, 1985).

Françoise Daulte, “Renoir dessinateur et aquarelliste,” L’oeil 358 (May 1985), p. 64 (ill.).

Christopher Riopelle, “Renoir: The Great Bathers,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 86, 367–68 (Fall 1990), pp. 18, 20, fig. 19.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins, et aquarelles, vol. 3, 1895–1902 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2010), p. 500, no. 2570 (ill.).

Other Documentation

Inscriptions and Distinguishing Marks

Recto

Mark

Location: lower right

Method: graphite

Content: 100 × 67

Verso

It is not possible to confirm inscriptions or marks, as the visibility is obscured by the lining.

Examination Conditions and Technical Analysis

Raking Visible Light

Paper support characteristics identified.

Transmitted Visible Light

Paper mold characteristics identified.

Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Fluorescence (365 nm)

Light surface sizing detected; former restorations were revealed.

Stereomicroscopy (80–100×)

Media identified.

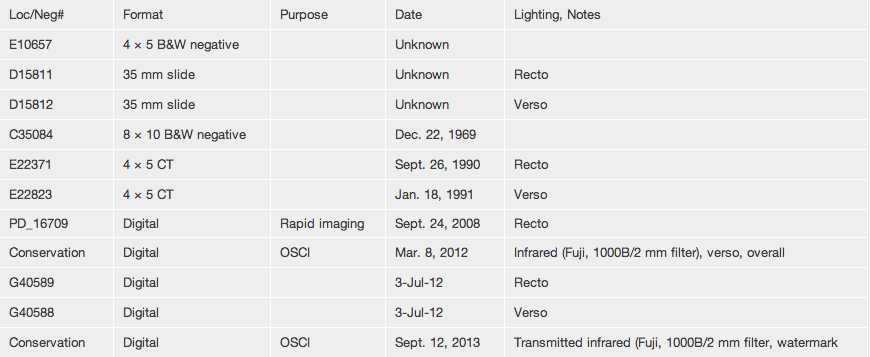

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Imaging Department and in the conservation and curatorial files in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 23.11).