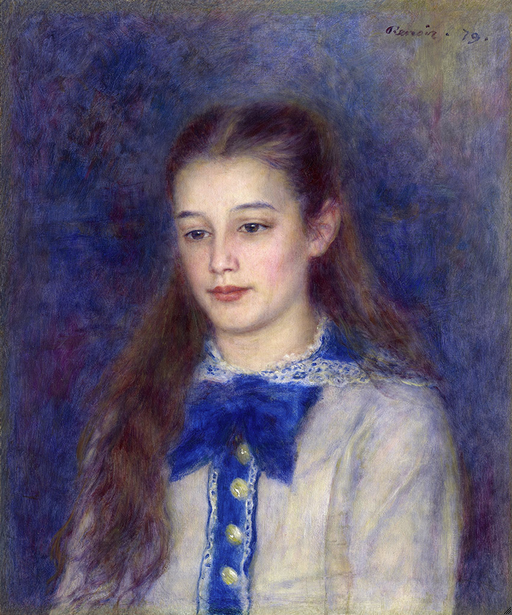

Cat. 17

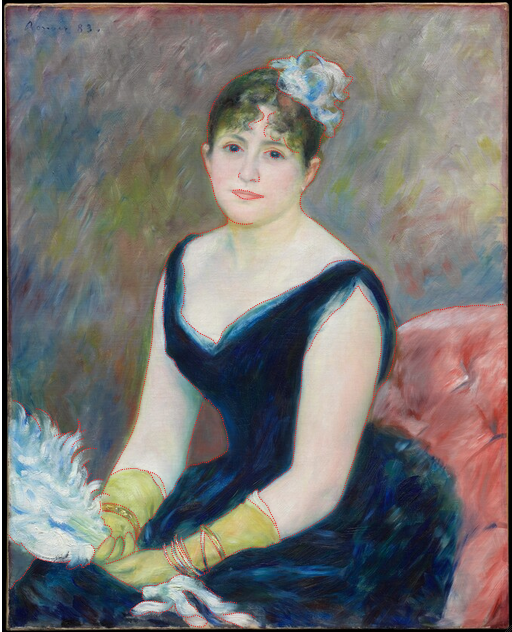

Madame Léon Clapisson

1883

Oil on canvas; 81.2 × 65.3 cm (32 × 25 3/4 in.)

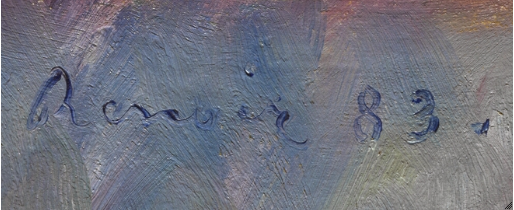

Signed and dated: Renoir 83. (upper right, in purple paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1174

Renoir and the Clapissons

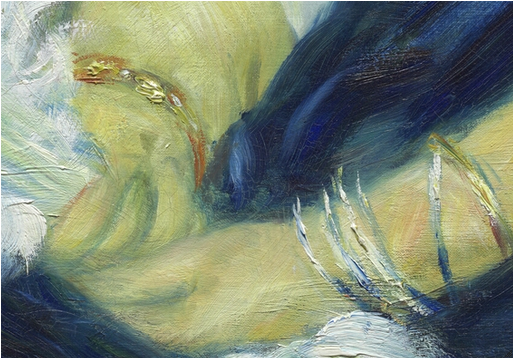

In a sleeveless gown of deep blue that complements her eye color, this confident socialite, the thirty-three-year-old Marie Henriette Valentine Clapisson, née Billet, is dressed for the ballroom. Her costume is consistent with the elongated silhouette of the ball gowns appearing in the pages of the Journal des demoiselles (fig. 17.1). Featuring a close-fitting bodice, possibly of smooth velvet, the dress strikes a formal note with its simple band of sheer trim running along the neckline and shoulders. The strong line of the bodice contrasts with the exaggerated volumes of the ruffled bustle, also dark blue but made of shimmering, pleated silk accented with translucent red and yellow. Gold, silver, and amber bracelets over gloves the color of chamois leather provide contrasting tones and reflect the light. The white feather fan Madame Clapisson holds echoes her exotic hair adornment in texture and form. As rendered by Renoir, the overall effect of her costume is subtly elegant and seems calculated to demonstrate a progressive fashion sense.

Renoir claimed to have met the Clapissons at a salon hosted by Marguerite Charpentier, wife of publisher Georges Charpentier, a collector of Impressionist art since 1875. The Charpentiers were leaders in matters of taste within their social circle. They lent a bust portrait of Marguerite (1876; Musée d’Orsay, Paris [Daulte 226; Dauberville 465]) to the third Impressionist exhibition, which opened in April 1877, and they would no doubt have alerted their circle to the article by Georges Rivière in the April 21 issue of L’impressionniste urging wives of good Republicans to let an Impressionist paint “a ravishing portrait that will capture the charm with which you are gifted.” In April 1879, Charpentier’s publishing house launched La vie moderne, a literary and social journal edited by Émile Bergerat that featured regular reviews of art exhibitions, including those of the Impressionists, and reproduced illustrations and drawings by Renoir. The gallery of La vie moderne, situated at its offices on the boulevard des Italiens, hosted the first solo exhibition of Renoir’s work (mostly pastels) in June 1879, the fifth in a series devoted to contemporary artists.

The Clapissons were typical of the readers of La vie moderne—culturally broad-minded enough to speculate in Impressionist painting but still supportive of the jury system of the annual Salon and of change from within. Léon Clapisson (fig. 17.2), son of the composer Antoine-Louis Clapisson, was a businessman who dabbled in stocks and real estate and had a passion for art collecting. As Anne Distel discovered, Léon already possessed a considerable fortune when he married Valentine (fig. 17.3), thirteen years his junior, in 1865. Clapisson began collecting seriously in 1879, and by the end of May 1882 he had acquired his first Renoir works from the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel: three paintings that the artist had brought back from a trip to Algeria in March and April. In a short period Clapisson amassed some 116 works, including works by artists of the Barbizon and Realist Schools. In addition to Renoir, Impressionist artists in his collection included Claude Monet, Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley. By 1885, however, Clapisson began selling his collection.

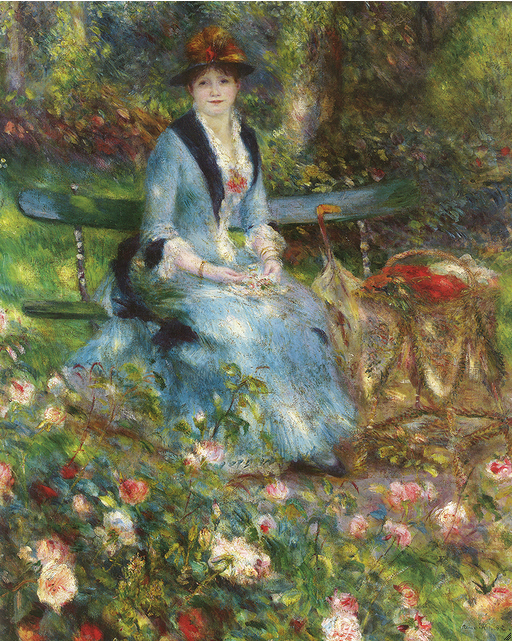

The Clapisson Commission and Renoir’s Impressionist Identity

Given the pace of Clapisson’s acquiring in the early 1880s, it seems understandable that Renoir may have mistaken this collecting activity for a commitment to the aesthetic principles of Impressionism. However, the commission to paint Madame Clapisson’s portrait proved to be one of the most frustrating of his career: the client rejected his initial attempt, now known as Among the Roses (fig. 17.4 [Daulte 428; Dauberville 1044]), and required him to paint the more conservative second version now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. This second version of Madame Clapisson’s portrait is the “city” to the first version’s “country”; the studied, sensual image of social ambition to the quintessential Impressionist female model in a garden setting—a work “full of gaiety and sunlight,” as Georges Rivière described the style of painting he recommended to potential portrait clients in 1877. Renoir painted Among the Roses in the garden of the recently built Clapisson villa on the rue Charles Laffitte, Neuilly-sur-Seine (fig. 17.5). The artist apparently brought more than one canvas from Paris and stayed in Neuilly for about two weeks. The first portrait, however, was the only painting he completed there.

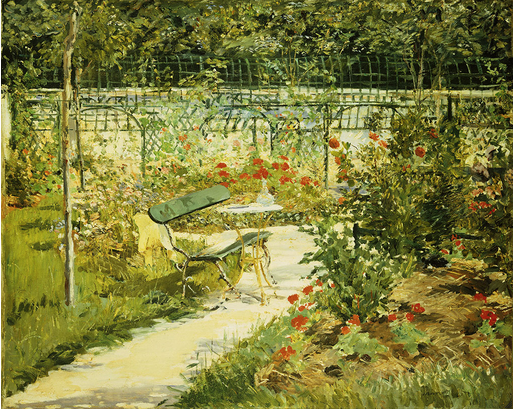

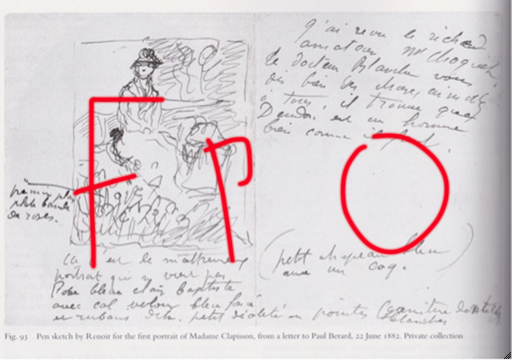

In this first version of the Clapisson portrait, Renoir’s placement of Valentine in the middle ground and his decision to portray her garden as a rustic, overgrown park in Montmartre turned out to be ill conceived. Perhaps he had in mind Édouard Manet’s melancholic late canvas The Artist’s Garden at Versailles of 1881 (fig. 17.6), just purchased by Léon Clapisson the previous month, though the two could not be further apart in mood and gestural depiction of garden elements. By June 22 his client’s patience had apparently worn thin, and Renoir realized he had taken the wrong approach. He wrote to his friend and patron Paul Berard, including in the letter a quick sketch of his work in progress (fig. 17.7): “This wretched portrait . . . will not work . . . my days are spent taking the canvas back indoors . . . after making this exquisite woman put on a spring dress . . . and every day the same thing.” The sketch reveals that Renoir was already near completion of the work, and the fact that he could describe Madame Clapisson’s costume down to the “lace trim” and “little blue hat with a rooster” indicates that he took some pride in his work, even if his client grew dissatisfied. Though the Clapissons returned the first version to the artist later in the year, it did not languish as a failed portrait but rather was reinvented and circulated in exhibitions for years as a genre painting of contemporary life.

By the autumn of 1882 the Clapissons had decided to return the first portrait with the expectation that Renoir would paint another with an indoor setting. This turn of events weighed heavily on the artist. It challenged the artistic ideals he had cultivated over the 1870s and forced him to accept the necessity of compromise if he wished to pursue portrait painting. He complained to Berard of how the commission affected his artistic license: “It’s not going well for the moment. I must begin Mme. Clapisson’s portrait all over again. It’s a big flop. . . . Well, all this takes a lot of thought, and with no exaggeration I must be careful if I don’t want to slip in the public’s esteem.” He continues, expressing with some sarcasm his bitter resignation to the more conventional approach to portraiture epitomized by the successful society portraitist Léon Bonnat: “I’m going to get back on the right path and I’m going to enlist in Bonnat’s studio. In a year or two I’ll be able to make 30,000,000,000,000 francs a year. Don’t talk to me any more about portraits in the sunlight. Nice black backgrounds, that’s the real thing. As soon as I have a minute, I’ll come and copy the portrait [by Bonnat] of M. d’Haubersart [Comte d’Haubersart, Berard’s grandfather].” While Renoir was not so richly compensated as Bonnat, he did receive the respectable sum of 3,000 francs for the Clapisson commission. Renoir’s anxiety over the portrait is perhaps partly explained by the high fee—twice as much as he reportedly earned in 1878 for the much larger Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children (1878; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [Daulte 226; Dauberville 239])—but was probably also due to his fear of alienating potential patrons within the Charpentier-Clapisson circle.

A New Style Emerges

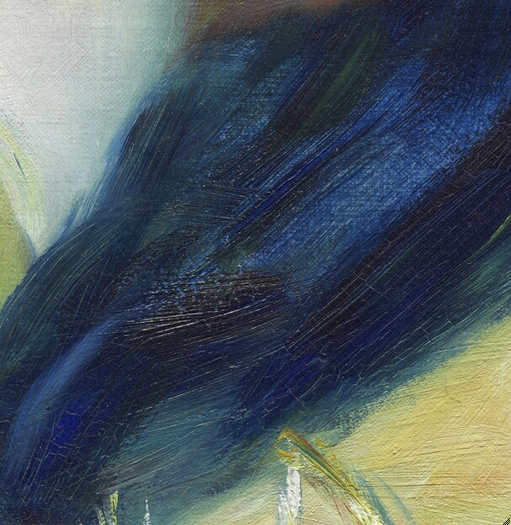

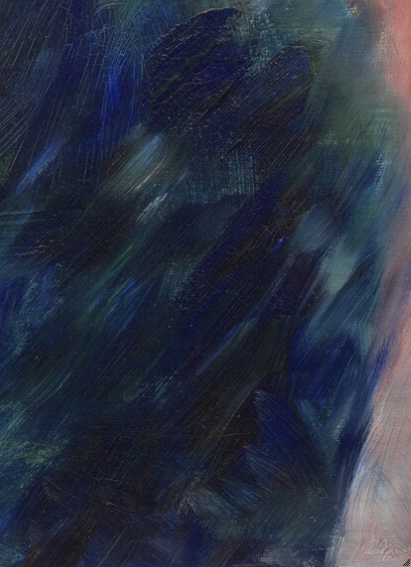

The circumstances surrounding the first version of the portrait of Madame Clapisson highlight a crisis in Renoir’s Impressionist enterprise that ultimately led to a remarkable change of technique and the emergence of his “Ingresque” manner, the so-called sour or dry style, the masterpieces of which are Children’s Afternoon at Wargemont (1884; Nationalgalerie, Berlin [Daulte 457; Dauberville 965]) and The Great Bathers (1884–87; Philadelphia Museum of Art [Daulte 514; Dauberville 1292]). To satisfy his clients, Renoir returned to the easel to paint a portrait of Madame Clapisson in a traditional setting with what the art critic Théodore Duret, in his biography of the artist, described as “tons plus sobres.” Though the firmer modeling of the second version can be compared to the academic-style portraits of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (see fig. 17.8), close examination of the brushstrokes within the dress, hair, fan, and background reveals that Renoir gave up nothing of his gestural randomness (fig. 17.9).

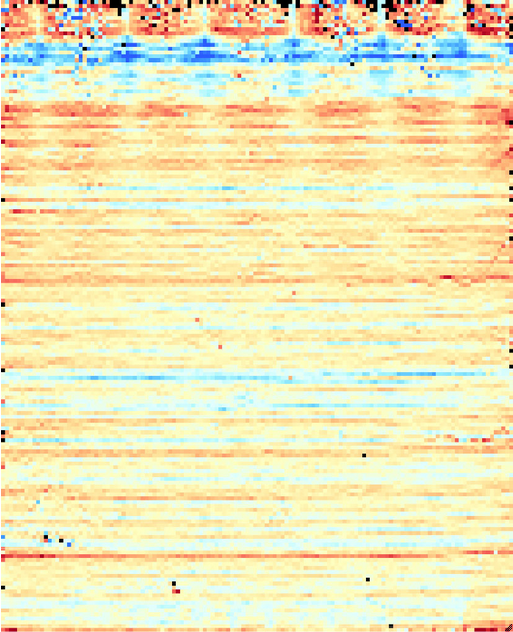

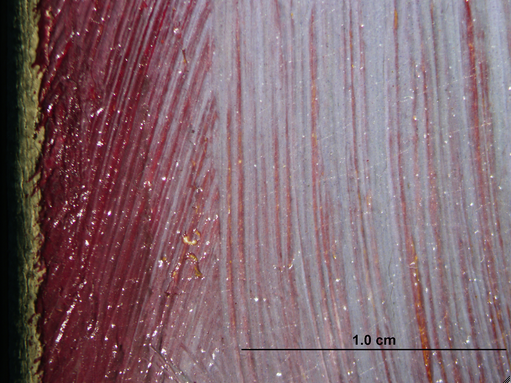

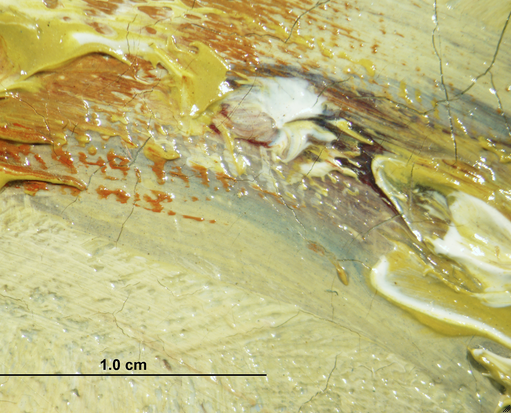

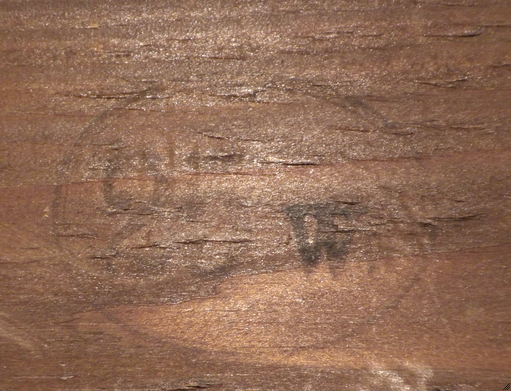

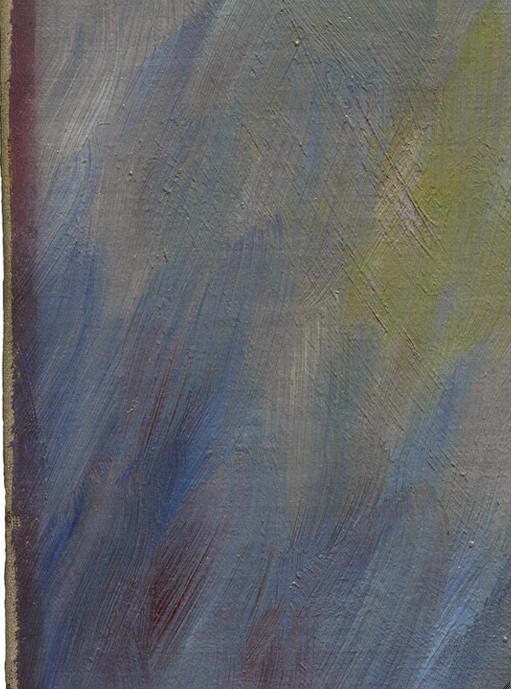

Renoir had used the dark backgrounds commonly seen in conventional society portraiture before, for example, in the series he executed of the Berard children in 1879 (see fig. 17.10 [Daulte 284; Dauberville 502]). The backgrounds of the Berard portraits contain subtle color harmonies and are visually active in their brushwork and distribution of paint. Returning to such a background for the second version of the Clapisson portrait, Renoir proceeded to create a more sober look by first diminishing the luminosity of the white ground with mossy green, rusty red, and earthy yellow colors. These initial background colors were later painted out with the current crosshatched pattern of purples, pinks, and blues. This second background finish once looked much darker than it does today. When the painting is unframed, a small margin of dark red can be seen around the edges of the canvas (fig. 17.11). These edges have been protected from fading by the frame rebate and so retain their original color. The extension of this rich burgundy tone from the margins through some or all of the canvas behind the figure of Madame Clapisson completely alters not only the modulation of color in the background but also our understanding of how Renoir intended the red tone to balance with the dark blue of her dress and the lighter flesh tones.

Despite his acceptance of this change in approach for the second version of the portrait of Madame Clapisson, it became a source of frustration for Renoir, who wrote to Berard as it was under way in early 1883: “I cannot tell whether it will turn out to look much like her, since I am no longer capable of judging for myself.” Admonished and having amended his overly bold Impressionist portrait style, the artist sent the finished canvas to the Salon exhibition that opened May 1, 1883, where it was neglected by the many critics who reviewed the show, possibly because they perceived it as a compromise of styles. In spite of this disregard, Renoir had every reason to be optimistic about his career during the first half of 1883, with the completion of his three major full-length dance paintings and the April opening of his retrospective exhibition on the boulevard de la Madeleine, part of a series of solo Impressionist exhibitions organized by Durand-Ruel. In his preface to the catalogue, Duret proclaimed Renoir the figure painter of Impressionism, especially of women, and his reputation as a portraitist seemed assured.

Perhaps it was disappointment at the meager return on his investment of time, canvas, and money that affected Renoir’s mood later in the year, but the difficulties he experienced with the Clapisson portrait commission and the cool reception the second version received at the Salon continued to haunt him. John Lewis Brown, who exhibited with the Impressionists in London in 1883, wrote to Durand-Ruel that September, noting that the Salon jury’s issues with the Clapisson portrait were only to Renoir’s credit: “The gentlemen of the jury could not help exclaiming (for the admission) that his painting was a ‘blonde’ Delacroix. What medal equals such appreciation from one’s enemies?” In December 1883 Berard, Renoir’s confidant throughout the trying period of the Clapisson portrait, remarked on the toll it had taken on his friend. Writing to collector Charles Deudon, he expressed his concern: “As far as Renoir, he is in a crisis of discouragement. His vast studio scares him and he can’t do anything there; except for the portrait of Mme Clapisson, I have seen nothing new and he has no new commissions.” While the self-doubt and uncertainty prompted by the Clapisson commission seemed insurmountable at the time, it nevertheless helped Renoir to develop as an artist and move on to further artistic accomplishment. Reflecting on these events decades later with the art dealer Ambroise Vollard, Renoir adopted a rosier perspective: “The charming Madame Clapisson, of whom I did two portraits, with what pleasure!”

The Clapisson portrait commission and the correspondence surrounding it provide a valuable case study of how the conflict between his own aspirations and his clients’ expectations played a role in Renoir’s forging of a new style in the 1880s; how he embarked on the commission with evident enthusiasm as a hardy Impressionist, ownreferencing his figures and landscapes of the 1870s by depicting Madame Clapisson in a garden setting, but ended with what John House described as “a remarkable synthesis of the conventions of Neo-Classical portraiture with a colourist palette.” The Clapissons remained cordial with Renoir, adding four more of his works to their collection. After her husband’s death in 1894, Madame Clapisson moved from the Neuilly villa and put most of the remaining Clapisson collection up for sale. The portrait remained in her possession until November 1908, when, apparently pressed for cash, she sold it to Durand-Ruel for 15,000 francs. She lived another twenty-two years, dying on August 30, 1930, two months before her eighty-first birthday.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

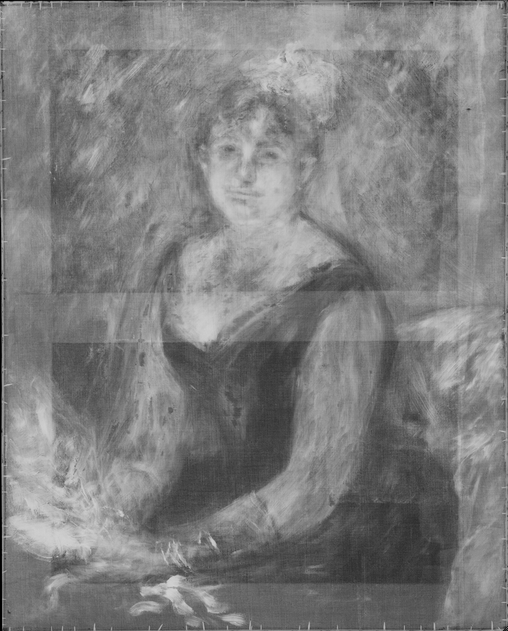

Renoir began this portrait of Madame Clapisson on a standard-size, [glossary:commercially primed] [glossary:canvas], to which a second [glossary:ground] was unevenly added over the compositional area. The artist executed a contour [glossary:underdrawing] in thin paint to establish the composition; most notably, he moved the figure’s right arm and hands at least twice during the drawing stage and possibly again during the painting stage before settling on their final position. Renoir then executed the figure, including a large feather ornament in her hair (possibly depicted in a fuller hairstyle at an earlier stage) and a feather fan that at one point took up more of the left side of the composition. These accessories are embellished with the same colors as those originally used in the background: a varied mix of olive green, rusty red, and earthy yellow. In some areas the artist blended these colors with the still-wet flesh tones; this is particularly apparent along the figure’s right arm. Evidence of these earlier colors can be seen in highlights on her skin and in the small halo visible around the figure and her hair. After trimming some previous compositional choices (including the hairstyle and ornament) by bringing in the background, Renoir repainted the hairstyle, hair ornament, and fan and adjusted the figure’s left side; the edges of these forms extend over the earlier background. Late in the process, he modified the background, using [glossary:wet-in-wet] crosshatching of cooler reds and purples with selected areas of green and yellow that recall the rusty, mossy colors underneath. The artist also may have adjusted the chair, as some of the earlier background colors can be seen immediately behind the figure above her bustle; however, the nature of this change is not entirely clear. Changing the tone of the background appears to have been one of the final steps in the painting process, as the signature was executed wet-in-wet in the fresh background paint. A small margin around the edges of the painting, usually covered by the frame, reveals that the red lake used in the background has faded, signifying that the background was probably much darker and more vibrant than it now appears. The work is currently varnished.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 17.12).

Signature

Signed and dated: Renoir 83. (upper right, in purple paint) (fig. 17.13).

The signature was painted wet-in-wet into the upper layers of the background paint (fig. 17.14).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

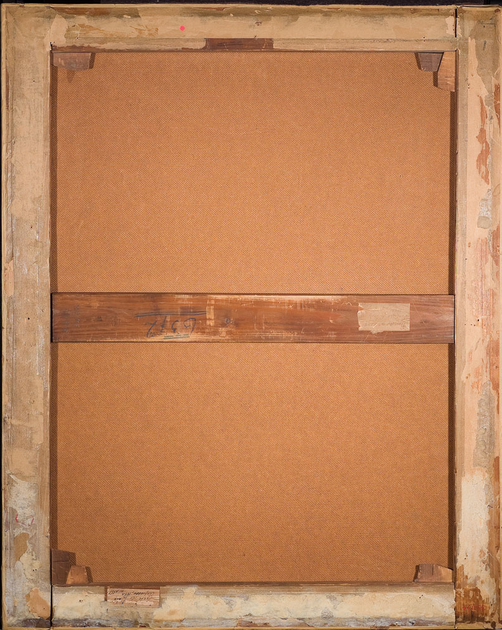

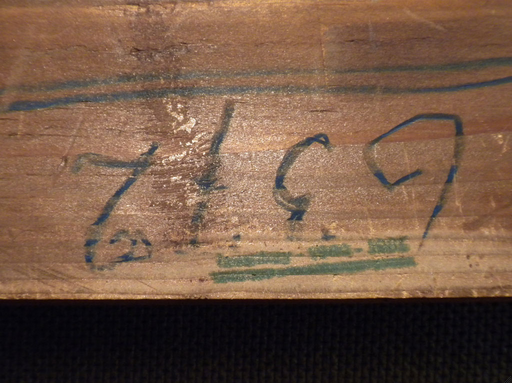

The original dimensions of the canvas were very close to its current measurements, 81.2 × 65.3 cm. This closely corresponds to a no. 25 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size (81 × 65 cm) canvas; this number is also stenciled on the verso of the [glossary:stretcher].

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 21.7V (0.8) × 21.6H (0.5) threads/cm. The horizontal threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the vertical threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

The canvas shows light [glossary:cusping] on all sides corresponding to the placement of the original tacks. The [glossary:warp-angle map] indicates that the top edge has very strong [glossary:primary cusping] associated with large-scale commercial canvas preparation (fig. 17.15). Any evidence of an unprimed edge or selvedge was probably removed from this side before or just after stretching.

Stretching

Current stretching: The work was restretched after being mounted to [glossary:hardboard] panel (see Conservation History); its dimensions were kept roughly the same.

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed approximately 3.5–5 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

The current stretcher is a five-member, keyable, blind mortise-and-tenon stretcher with a horizontal [glossary:crossbar]. Depth: Approximately 1.7 cm.

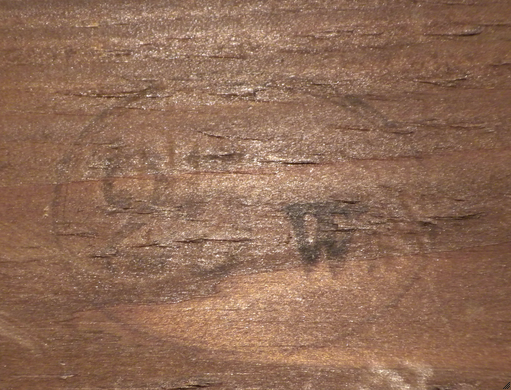

Although the painting was mounted to a hardboard panel in a previous conservation treatment, the structure and patina of the stretcher suggest that it is original (fig. 17.16). The current orientation of the stretcher—upside down—probably dates from this treatment (see Conservation History).

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black ovular stamp

Content: 25w (fig. 17.17)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

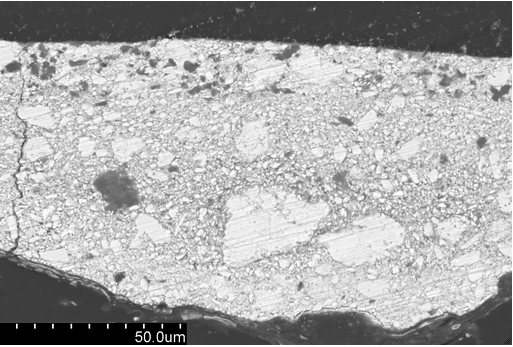

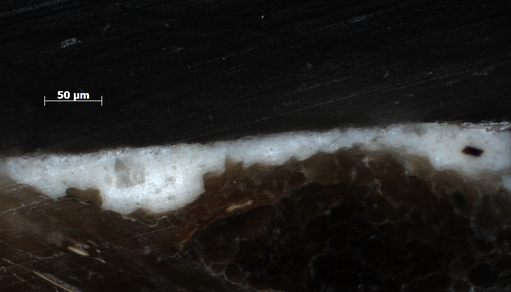

The canvas is commercially primed, with a thin, double-layer preparation extending to the edges of the [glossary:tacking margins]. The lower layer of the commercial ground is approximately 5–65 µm thick, while the very thin upper layer is approximately 3–15 µm thick. Renoir may have added an additional [glossary:priming] layer that appears rather uneven and does not cover the entire compositional area. Wide marks along more [glossary:radio-opaque] regions, perhaps from palette-knife application, are visible in the [glossary:X-ray] along the right side in a long diagonal across the area of the right stretcher bar (fig. 17.18).

Color

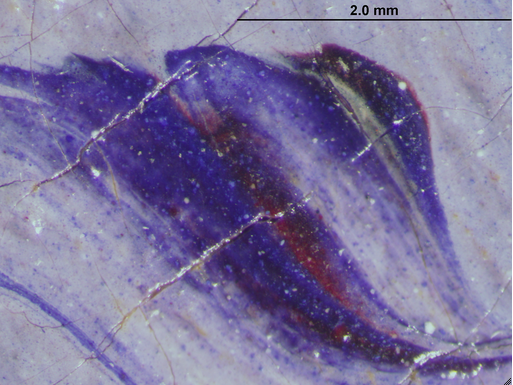

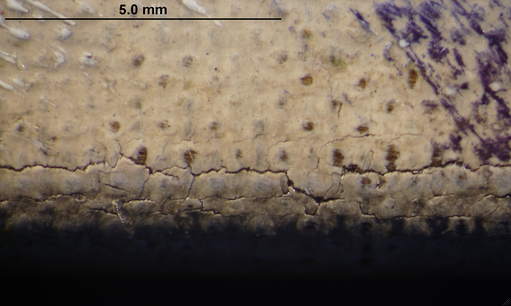

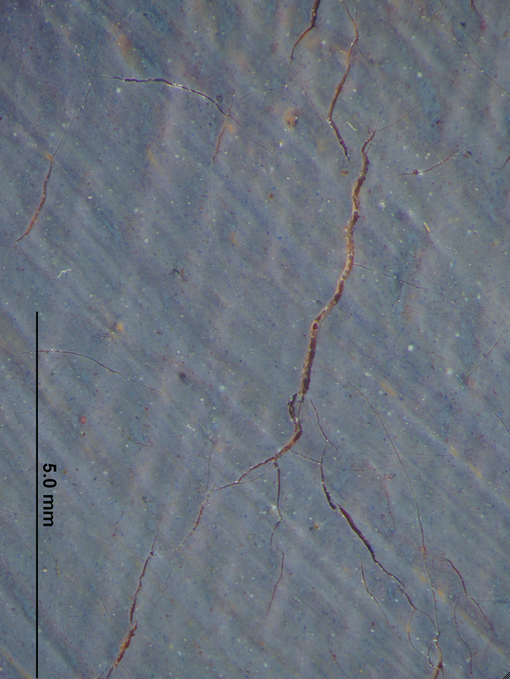

The commercial preparation appears off-white under [glossary:stereomicroscopic examination], while the additional ground layer is a slightly warmer cream color, with dark and red particles visible under stereomicroscopic examination (fig. 17.19).

Materials/composition

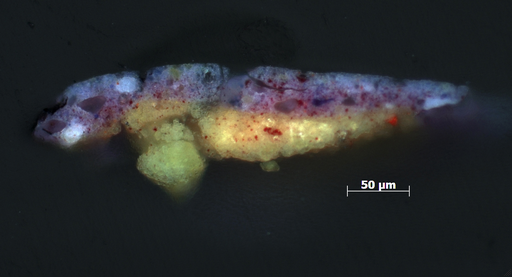

The two layers of the commercial preparation have a somewhat indistinct dividing line, primarily visible in the backscattered electron ([glossary:BSE]) image (fig. 17.20, fig. 17.21). This soft boundary may indicate that the layers were applied in quick succession as part of the commercial process. Both layers have a similar composition: predominantly lead white with some calcium carbonate, small amounts of iron oxide yellow and associated silicates, silica, and a few large carbon black particles; the upper layer of the commercial ground is distinguished by a slightly higher proportion of calcium carbonate and iron oxide. The composition of the additional preparatory layer could not be determined, as it was not captured in any of the samples taken for this study. The [glossary:binder] in all layers is estimated to be [glossary:oil].

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

Infrared examination suggests that the artist outlined the major forms and contours of the figure and costume.

Medium/technique

Infrared examination of the painting indicates that the artist executed the underdrawing in a liquid medium. The paint layer is quite thick, but the bluish shadows visible along the edges of the forms, especially the flesh and gloves, suggest that he used blue paint for the contour drawing.

Revisions

While it appears that Renoir made many of the identifiable changes in the later painting stages, [glossary:infrared reflectography] indicates that he altered the placement of the figure’s right arm and her hands during the planning stage.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

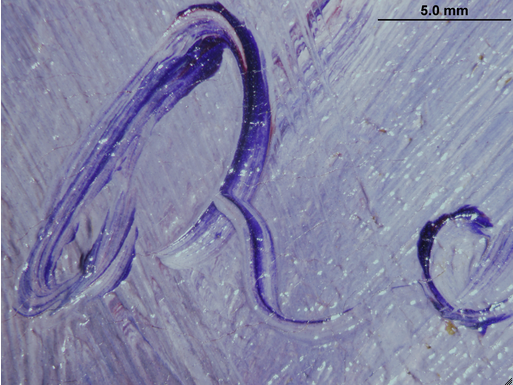

The artist first articulated the figure’s dress with a thin, wash-like layer of fluid, blue paint, which can still be seen in gaps in the translucent paint layers above where they function as highlights (fig. 17.22). Renoir applied somewhat thick, medium-rich, glaze-like layers of translucent cobalt blue and red lake with a flat brush to further articulate the dress (fig. 17.23). Hints of white and yellow provide additional highlights in areas where the thin underpaint has been obscured. Toward the bottom of the composition, beneath the ends of the feathers and the figure’s hands, the artist left a small portion of ground visible; here he brought the dress paint up to the edges of the reserve before adding heavy white paint on top to make the ribbons that trail from the end of the feather fan. The X-ray shows that an additional ribbon or stray feather once extended from the figure’s hands across her lap toward the left edge of the composition; this was painted out.

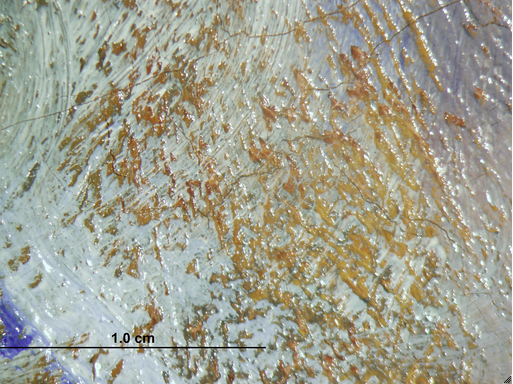

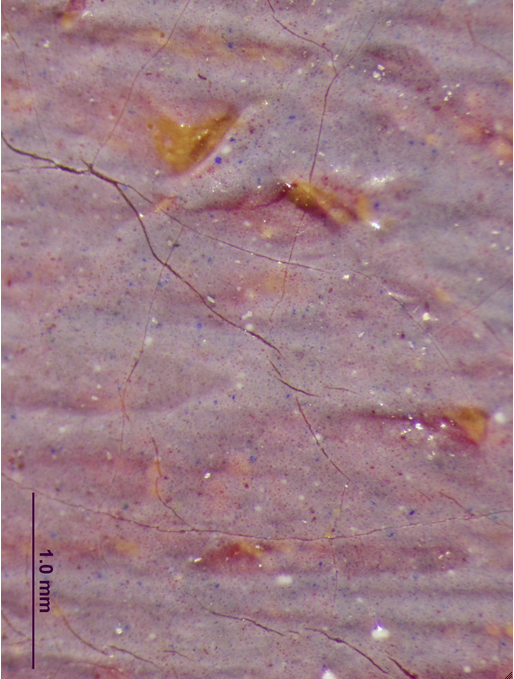

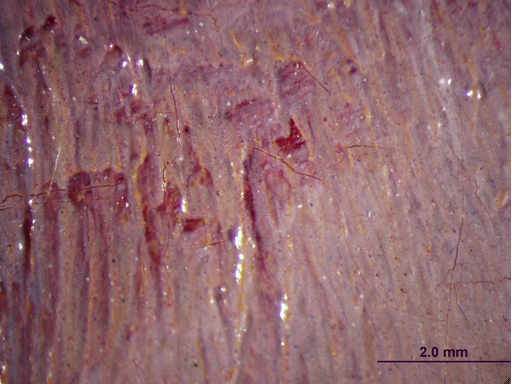

Renoir initially executed the background in shades of mossy green, rusty red, and earthy yellow that, worked wet-in-wet with one another, create a warm and vibrant backdrop still reflected in the highlights and shadows of the figure’s skin, especially at the chin, neck, and arms (fig. 17.24). This original background was brought in around the compositional forms and covers portions of the feathers in both the fan and the hair ornament. The visible, smaller feathered accents in the figure’s hair were mostly executed on top of this bold background (fig. 17.25). Later in the painting stage, the artist changed the background to its current crosshatched pattern of purples, pinks, and blues, with occasional hints of green referring to the colors underneath. The original background is still visible in many areas of the composition where the new background was not heavily worked, as well as immediately around the forms, creating a kind of halo (fig. 17.26).

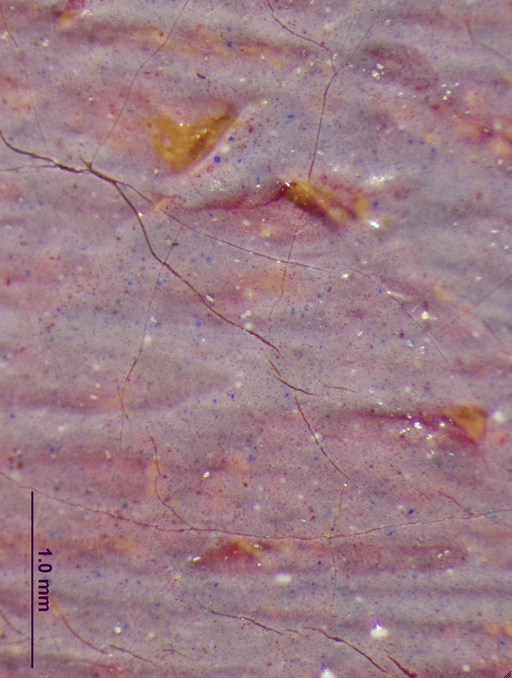

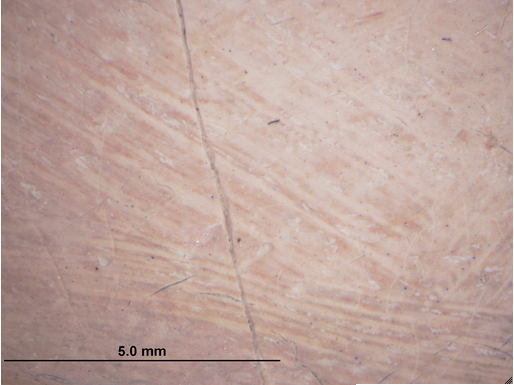

Looking at the painting out of its frame, it is apparent that the red lake in the background has faded (fig. 17.27). The intensity of the red lake in the small margins of paint usually covered by the frame and in some depressions and cracks in the paint layer (fig. 17.28) suggests that the newer background was not more muted than the earlier one, as it currently appears, but rather cooler, or less yellow in overall tone. This change in the background appears to have been made very late in the process, as it was still wet when Renoir signed the work (fig. 17.29).

The flesh tones are very smoothly modeled, and the artist used a variety of techniques to smooth the figure-to-ground transition. Along the figure’s right side, the background and flesh colors were mixed while wet, whereas along the top of the dress, he used a thin wash of blue over the flesh tone to mimic this blurred effect. Renoir mixed the early background colors directly into the figure’s hair, creating tendrils of greens and muted reds to frame the figure’s face (fig. 17.30). The X-ray and raking-light images indicate that he made changes to the figure’s arms and hand placement in the painting stage. Infrared examination shows that the waist seemed once somewhat wider, with a bit of the dress visible at the waist between the back of the figure’s left arm and the chair. The artist also moved the figure’s right arm closer to her body after some scraping and addition of more background paint. When he moved the arm closer to the body, he also adjusted the contour of the waist such that the space between the waist and the arm remained roughly the same size. The infrared images and X-ray also reveal that Renoir reduced the size of the figure’s right shoulder and upper arm, and the trim of the dress along either the sleeve or her bust. These adjustments, in combination with bringing in rusty-red background paint along the back side of her left arm, resulted in a significantly slimmer waistline and the appearance of a smaller upper body. The presence of background paint along the back side of the figure’s arm may indicate that the artist changed the placement or design of her chair (fig. 17.31). Above the bustle, wide brushstrokes that do not correspond to visible forms and additional cracking not seen elsewhere in the chair suggest changes; however, the specific nature of these changes is unclear.

Though the X-ray reveals uneven, blotchy marks throughout and alongside the figure’s right arm and through parts of her torso, indicating that Renoir scraped back these parts of the composition, there is no textural evidence of this scraping technique or the previous placement of the arm and torso on the surface. On the hands, however, thick brushstrokes from their previous position can be seen under normal viewing conditions (fig. 17.32). After he moved her right arm, the artist also adjusted the placement of the figure’s gloved hands and fingers, as well as their visibility among the folds of the dress. In the figure’s left hand, heavy strokes of blue and white from the dress and fan are clearly visible beneath the yellow. Additional faint strokes suggest that Renoir may have adjusted the placement of the bracelets early in this phase, as they were first executed in thin blue paint before the heavy yellow-and-white [glossary:impasto] was added as an almost final detail (fig. 17.33).

Painting tools

Flat and round brushes of varying hardness with strokes up to 1.2 cm wide; very fine brushes for details such as the eyes and portions of the hair; [glossary:palette knife] for scraping.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, cobalt blue, vermilion, carmine (cochineal) lake, zinc yellow, strontium yellow, a trace of emerald green, and possibly a trace of charcoal black.

Results of the most current analysis suggest that two types of red lake based on the same dyestuff (cochineal) were used in this painting: a lighter one with an aluminum-phosphorus substrate and a darker one on a tin base. The fading does not seem to be associated strictly with the [glossary:substrate] or the dyestuff; therefore, it is not entirely clear why some areas have faded while others have retained their original hue. Looking along the edges of the background, where the painting was covered by the rebate of the frame, it is clear that the level of fading is quite pronounced. The left side of the painting displays a particularly sharp boundary between the protected and unprotected areas, while the top edge shows a gradual fade, illustrating the protection not only of the frame, but of its shadow, as the painting is often lit from above. Near the top, there are areas where the undersides of the impasto and other depressions in the paint layer, as well as edges of paint visible along cracks, still retain some of their original color (fig. 17.34). Conversely, throughout these areas, numerous translucent, apparently unpigmented (but more likely faded) particles can be seen (fig. 17.35). A cross section from the faded area in the upper left quadrant of the background (fig. 17.36) shows a thin skin of faded paint, appearing pale blue from the surface (fig. 17.37), with deep, unfaded red lake particles just beneath it and throughout the rest of the sample. Based on the color revealed along the left and top edges, a digital image with the faded red color restored to the background was generated as a visualization of the painting’s original appearance (fig. 17.38).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting has a [glossary:synthetic varnish] that was applied during the 1972 treatment. This varnish replaced a discolored [glossary:natural-resin varnish] that probably dated from the 1939 treatment of the work, which itself replaced a [glossary:varnish] of unknown composition and origin. It is unclear whether the pre-1939 varnish was original to the painting.

Conservation History

The first documented treatment is associated with a letter dated May 27, 1939, which included payment details for removing varnish, revarnishing, and [glossary:retouching]. The letter also mentions that the work was to be “mounted to Masonite.” It was previously thought that the painting was probably aqueously lined to a secondary canvas and then mounted to a Masonite or similar hardboard panel; however, recent examination indicates that the painting is indeed adhered to the hardboard with no apparent [glossary:interleaf]. Labels and inscriptions, including the manufacturer’s size stamp, on the verso suggest that the painting retains its original stretcher. The current orientation of the stretcher—upside down—probably dates from this treatment. The tacking margins were preserved and the edges covered with paper tape.

The painting was treated again in 1972, and at that time it was noted to be structurally sound but with much overpaint hiding various areas of craquelure and a discolored natural-resin varnish. The painting was sampled (including areas of suspected repaint) to determine which areas were likely to be original. It was determined that repainted areas included the figure’s right arm and in and around the chin. Grime, varnish, and most of the repaint were removed, but remnants of retouching can be seen in the depressions of the paint layer throughout the chin (fig. 17.39). The work was inpainted and given a synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, inpainting, and a final coat of L-46). Paper tape was recently removed from the edges to facilitate examination.

Condition Summary

The painting is in stable condition, aqueously mounted to a Masonite or similar hardboard panel, with a slightly concave overall warp. A stretcher crease runs horizontally across the center of the picture, corresponding to the crossbar on the current stretcher. Much of the figure, dress, and areas immediately surrounding them have a general network of cracks, probably resulting from the thickness of the paint and compositional changes executed in relatively quick succession before the underlayers were completely dry. In some areas these cracks are slightly open, revealing the underpaint; in other areas they have been inpainted. A small margin usually covered by the frame indicates that the red lake used in the background has faded. [glossary:UV] examination reveals the presence of a UV-absorbing material in the figure’s face and chest that seems to correspond to slightly yellow areas in the paint layer. In some portions of the chin and face, this material has been identified as overpaint from a previous treatment, and it is possible that a thin layer of overpaint is extant on the chest as well. The work is varnished to an even sheen.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame may be original to the painting. It is a French (Paris), late-nineteenth-century, Durand-Ruel, Régence Revival, gilt ogee frame with cast foliate ornament, center and corner cartouches, and a gilt fillet liner. The frame has water and oil gilding over bole on cast plaster and gesso. The bole color varies throughout the frame: there is orange bole on the sanded frieze and fillets; red bole on the perimeter molding, sight molding, liner, and ogee face; and black-gray bole on the scotia sides. The scotia sides and liner are burnished, and the cast foliate ornament and sight molding are selectively burnished. The quadrillage bed on the ogee face has been rubbed selectively to expose the underlying plaster. The gilding was toned with a casein or gouache raw umber [glossary:wash] and gray overwash. In 1969, the frame was cleaned, removing most of the original toning and abrading the gold; the gilding on the sight edge of the liner was removed at this time. The frame has a glued pine substrate that is mitered and nailed with a cast plaster face. At some point in the frame’s history, the original verso was planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance, a back frame was added, and all back and interior surfaces were painted. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is fillet with stylized dovetail-pierced egg-and-flower outer molding; scotia side; ogee face with cast foliate and flower ornament on a quadrillage bed and center and corner foliate scroll cartouches with cabochon centers on a diamond bed; sanded front frieze bordered with fillets; ogee with stylized leaf-tip-and-shell sight molding; and an independent flat fillet liner with cove sight edge (fig. 17.40, fig. 17.41).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Commissioned from the artist by the sitter’s husband, Louis Léon Clapisson, Neuilly, for 3,000 francs.

By descent from Louis Léon Clapisson (died 1894), Neuilly, to his wife, Madame Louis Léon Clapisson (née Marie Henriette Valentine Billet), Neuilly, 1894.

Sold by Madame Louis Léon Clapisson (née Marie Henriette Valentine Billet), Neuilly, to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Nov. 12, 1908, for 15,000 francs.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, July 8, 1913, for $12,000.

Bequeathed by Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Exhibition History

Paris, Palais des Champs-Élysées, Société des Artistes Français, Salon, May 1–June, 1883, cat. 2031, as Portrait de Mme C. . . .

Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 5e exposition internationale de peinture et de sculpture, June 15–July 15, 1886, cat. 125, as Portrait de Mme C. Appartient à M. Clapisson.

Paris, Durand-Ruel, Tableaux par Monet, C. Pissarro, Renoir, et Sisley, June 1–30, 1910, cat. 43, as Portrait de Mme C. 1883.

Possibly New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 14–Mar. 16, 1912, cat. 7, as Jeune femme à l’éventail, 1883.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture for 1934, June 1–Oct. 31, 1934, cat. 229.

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, The Sources of Modern Painting: A Loan Exhibition Assembled from American Public and Private Collections, Mar. 2–Apr. 9, 1939; New York, Wildenstein, Apr. 25–May 20, 1939, cat. 5 (ill.) (New York only).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 45 (ill.).

New York, Wildenstein, Renoir: The Gentle Rebel; A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Association for Mentally Ill Children, Oct. 24–Nov. 30, 1974, cat. 26 (ill.).

London, Hayward Gallery, Renoir, Jan. 30–Apr. 21, 1985, cat. 70 (ill.); Paris, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, May 14–Sept. 2, 1985, cat. 69 (ill.); Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Oct. 9, 1985–Jan. 5, 1986.

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, June 27–Sept. 14, 1997, cat. 46 (ill.); Art Institute of Chicago, Oct. 17, 1997–Jan. 4, 1998; Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, Feb. 8–Apr. 26, 1998. (fig. 17.42)

San Diego Museum of Art, Idol of the Moderns: Pierre-Auguste Renoir and American Painting, June 29–Sept. 15, 2002, cat. 3 (ill.); El Paso (Tex.) Museum of Art, Nov. 3, 2002–Feb. 16, 2003.

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 31 (ill.).

Selected References

Catalogue illustré du Salon, under the direction of F.-G. Dumas, exh. cat. (Librairie d’Art L. Baschet, 1883), p. 44, cat. 2031.

Explication des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, architecture, gravure et lithographie des artistes vivants (Bernard, 1883), p. 185, cat. 2031.

Galerie Georges Petit, Exposition internationale de peinture et de sculpture, cinquième année, exh. cat. (Renou & Maulde, 1886), p. 23, cat. 125.

Félix Fénéon, “Ve exposition internationale,” La vogue (June 28–July 5, 1886), p. 342.

Durand-Ruel, Paris, Tableaux par Monet, C. Pissarro, Renoir, et Sisley, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1910), p. 5, cat. 43.

“Renoir at Durand-Ruel’s,” American Art News 10, 19 (Feb. 17, 1912), pp. 2, 9 (ill.).

Possibly Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1912), cat. 7.

Art Institute of Chicago, General Catalogue of Paintings Sculpture and Other Objects in the Museum (Art Institute of Chicago, 1914), p. 211, cat. 2142.

Ambroise Vollard, La vie et l’oeuvre de Pierre-Auguste Renoir, vol. 2 (A. Vollard, 1919), p. 92.

Ambroise Vollard, “Le salon de Mme Charpentier,” L’art et les artistes 1 (Jan. 1920), p. 164.

François Fosca, Renoir (F. Rieder, 1923), p. 61; pl. 19. Translated by Hubert Wellington as Renoir, Masters of Modern Art (Dodd, Mead, 1924), p. 6; pl. 24.

Théodore Duret, Renoir (Bernheim-Jeune, 1924), p. 70. Translated into English by Madeleine Boyd as Renoir (Crown, 1937), pp. 52; pl. 56.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 162, cat. 2157.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute (Continued),” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 4 (Apr. 1925), p. 48 (ill.).

Albert André, Renoir, Cahiers d’aujourd’hui (G. Crès, 1928), pl. 15.

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1929), p. 169, no. 163 (ill.).

Reginald Howard Wilenski, French Painting (Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1931), p. 262.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für Freunde und Sammler der Kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 78. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), p. 39, cat. 229.

Albert C. Barnes and Violette de Mazia, The Art of Renoir (Minton, Balch, 1935), pp. 77; 78; 455, no. 139.

Ambroise Vollard, En écoutant Cézanne, Degas, Renoir (Bernard Grasset, 1938), p. 193.

Institute of Modern Art, The Sources of Modern Painting: A Loan Exhibition Assembled from American Public and Private Collections, exh. cat. (Wildenstein and Co., 1939), p. 22, cat. 5 (ill.).

Reginald Howard Wilenski, Modern French Painters (Reynal & Hitchcook, [1940]), p. 340.

Michel Drucker, Renoir, with a preface by Germain Bazin (Pierre Tisné, 1944), p. 186.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), pp. 397–98.

François Daulte, Auguste Renoir: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, vol. 1, Figures, 1860–1890 (Durand-Ruel, 1971), pp. 298–99, cat. 433 (ill.).

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), pp. 84; 113; 114, cat. 559 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pl. 8; pp. 15; 100; 118–19, cat 45 (ill.); 182; 202; 208 (detail); 209 (detail); 211; 214.

Barbara Ehrlich White, “The Bathers of 1887 and Renoir’s Anti-Impressionism,” Art Bulletin 55, 1 (Mar. 1973), p. 122.

Wildenstein, Renoir: The Gentle Rebel; A Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Association for Mentally Ill Children, with a foreword by François Daulte, exh. cat. (Wildenstein, 1974), cat. 26 (ill.).

J. Patrice Marandel, The Art Institute of Chicago: Favorite Impressionist Paintings (Crown, 1979), pp. 74–75 (ill.).

Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et son époque: Dictionnaire international illustré, vol. 1 (Denoël, 1979), p. 138.

Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et son époque: Dictionnaire international illustré, vol. 2 (Denoël, 1979), pp. 173, 175.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism (Abbeville, 1980), pp. 256 (ill.), 438.

Diane Kelder, The Great Book of French Impressionism, Tiny Folios (Abbeville, 1980), p. 163, pl. 22.

Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (Abrams, 1984), pp. 126, 129, 132 (ill.), 298.

Hayward Gallery, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Renoir, exh. cat. (Arts Council of Great Britain, 1985), pp. 113, cat. 70 (ill.); 221; 238, cat. 70 (ill.); 301.

Hayward Gallery, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Renoir, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1985), pp. 176; 224–25, cat. 69 (ill.); 380.

Anne Distel, “Charles Deudon (1832–1914) collectionneur,” Revue de l’art 86 (1989), p. 62, n. 2.

Raffaele De Grada, Renoir (Giorgio Mondadori, 1989), p. 15.

Sophie Monneret, Renoir, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1989), p. 154, fig. 7.

Nicholas Wadley, ed., Renoir: A Retrospective (Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, 1987), pp. 158, 161, 162 (ill.).

Christie’s, New York, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, pt. 2, sale cat. (Christie’s, New York, Nov. 11, 1997), p. 44 (ill.).

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 56; 57–59; 60; 96, pl. 15 (ill.); 110.

Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 202–03, cat. 46 (ill.); 204; 316–17, cat. 46; 319, n. 10. Translated by Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, with support from Nada Kerpan for the texts by Linda Nochlin, as Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 202–03, cat. 46 (ill.); 204; 316–17, cat. 46; 319, n. 10.

Colin B. Bailey, “Portrait of the Artist as a Portrait Painter,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 8, 19. Translated as Colin B. Bailey, “Portrait de l’artiste en portraitiste,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, trans. Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 11, 19.

Anne Distel, “Léon Clapisson: Patron and Collector,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 77; 78, cat. 46 (ill.); 80; 85, n. 33. Translated as Anne Distel, “Portrait de Monsieur Clapisson en mécène,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, trans. Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), pp. 77; 78, cat. 46 (ill.); 80; 86, n. 33.

Anne Distel, “Appendix II: The Notebooks of Léon Clapisson,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. (National Gallery of Canada/Yale University Press, 1997), p. 354. Translated as Anne Distel, “Annexe II: Les carnets de Léon Clapisson,” in Colin B. Bailey, with the assistance of John B. Collins, Les portraits de Renoir: Impressions d’une époque, trans. Danielle Chaput and Julie Desgagné, exh. cat. (Gallimard/Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1997), p. 354.

Sona Johnston, with the assistance of Susan Bollendorf, Faces of Impressionism: Portraits from American Collections, exh. cat. (Baltimore Museum of Art/Rizzoli, 1999), p. 25.

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), pp. 207, 210–11 (ill.), 432.

Anne E. Dawson, Idol of the Moderns: Pierre-August Renoir and American Painting, exh. cat. (San Diego Museum of Art, 2002), pp. 22, no. 3 (ill.); 72.

Christie’s, London, Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale, sale cat. (Christie’s, London, June 24, 2003), p. 68, fig. 3.

Christie’s, London, Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale, sale cat. (Christie’s, London, Feb. 2, 2004), p. 26, fig. 1 (ill.).

Aviva Burnstock, Klaas Jan van den Berg, and John House, “Painting Techniques of Pierre-Auguste Renoir: 1868–1919,” Art Matters: Netherlandish Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005), p. 52.

Robert McDonald Parker, “Topographical Chronology 1860–1883,” in Renoir Landscapes, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London, 2007), p. 278. Translated as Robert McDonald Parker, “Chronologie,” in Les paysages de Renoir, 1865–1883, ed. Colin B. Bailey and Christopher Riopelle, trans. Marie-Françoise Dispa, Lise-Éliane Pomier, and Laura Meijer, exh. cat. (National Gallery, London/5 Continents, 2007), p. 279.

Tamar Garb, The Painted Face: Portraits of Women in France, 1814–1914 (Yale University Press, 2007), p. 32, pl. 28.

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), pp. 77; 78, cat. 31 (ill.); 83. Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 77; 78, cat. 31 (ill.); 83.

Anne Distel, Renoir (Citadelles & Mazenod, 2009), pp. 178, ill. 164; 182–83; 186; 240; 380–81.

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 2, 1882–1894 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2009), p. 242, cat. 1065 (ill.).

John House, The Genius of Renoir: Paintings from the Clark, with an essay by James A. Ganz, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Museo Nacional del Prado/Yale University Press, 2010), p. 77.

Julie L’Enfant, Pioneer Modernists: Minnesota’s First Generation of Women Artists (Afton, 2011), p. 161 (ill.).

Colin B. Bailey, Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting, exh. cat. (Frick Collection/Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 168; 170, fig. 2.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel, New York, 3422 (purchase receipt)

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel Paris 6372

Other Documents

Label (fig. 17.43)

Inscription (fig. 17.44)

Inscription (fig. 17.45)

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Inscription

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script

Content: 33.1174 Madame Clapisson—Renoir (fig. 17.46)

Number

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script (marker) on masking tape

Content: C[. . .]4 (fig. 17.47)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black ovular stamp

Content: 25w (fig. 17.48)

Inscription

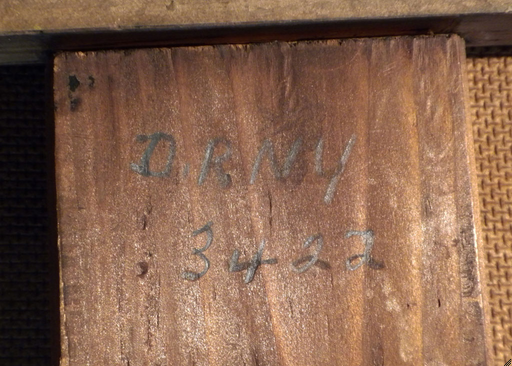

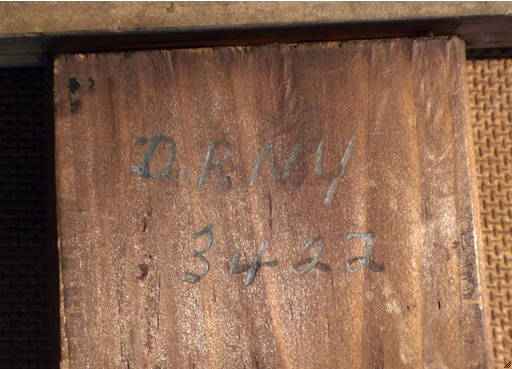

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: D.R NY / 3422 (fig. 17.49)

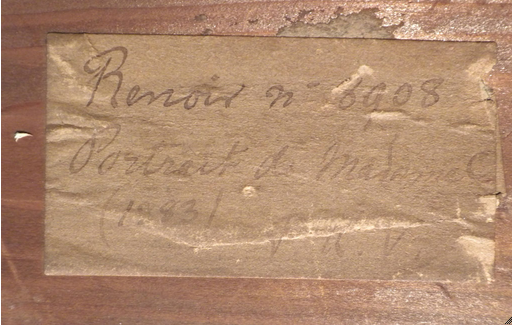

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (ink) on cream-colored label

Content: Renoir no 8908 / Portrait de Madame C / (1883 / [J. A. V.] (fig. 17.50)

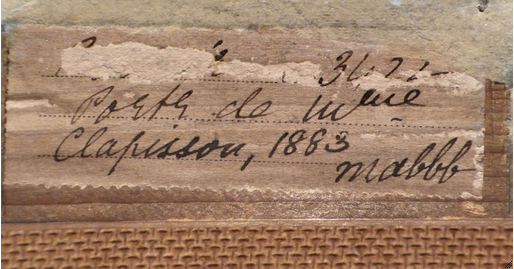

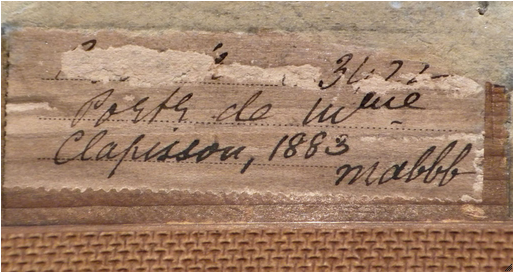

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (ink) on brown label

Content: [. . .] 34[2]2 / Portr de Mme / Clapisson, 1883 / mabbb (fig. 17.51)

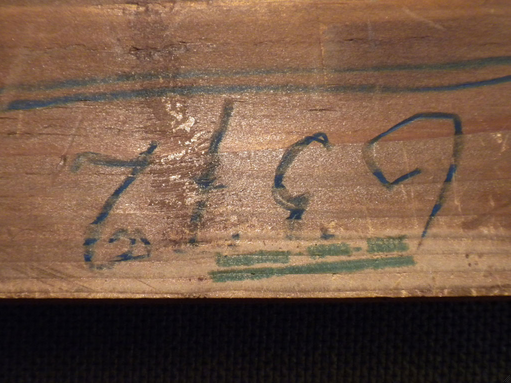

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

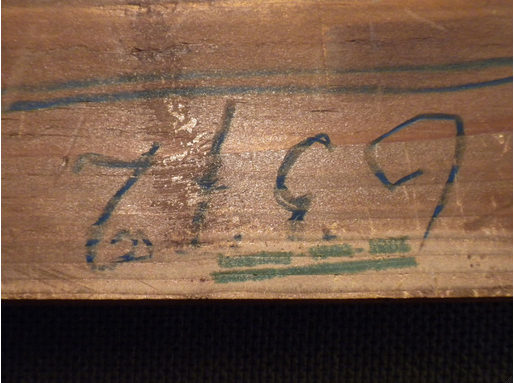

Content: [6]3[7]2 (fig. 17.52)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (red paint)

Content: 33.1174 (fig. 17.53)

Post-1980

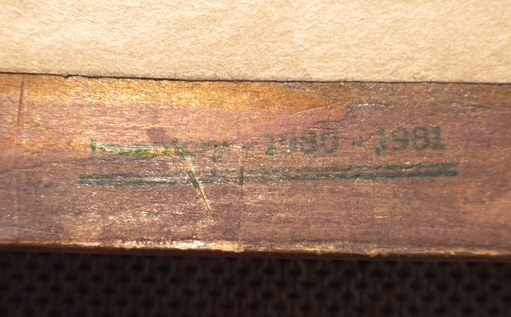

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 17.54)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 17.55)

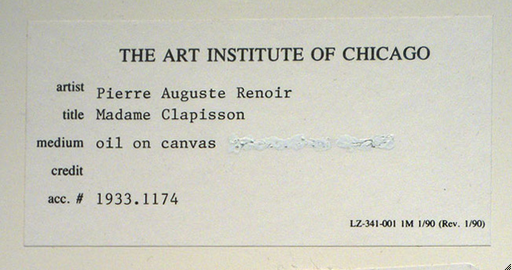

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Pierre Auguste Renoir / title Madame Clapisson / medium oil on canvas / credit / acc. # 1933.1174 / LZ-341-001 1M 1/90 (Rev. 1/90) (fig. 17.56)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age / Cat.No.: 46 / Artist: Pierre-Auguste Renoir / Title: Madame Clapisson / Owner: Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 17.57)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / “Renoir’s Portraits: Impressions of an Age” / October 17, 1997–January 4, 1998 / 46 / Pierr-Auguste [sic] Renoir / Madame Clapisson / The Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 17.58)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (X-NiteCC1 filter, Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

A Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope was used, equipped with an Andor multichannel, Peltier-cooled, open-electrode charge-coupled device detector (Andor DV420-OE322; 1024×256), an Olympus BXFM open microscope frame, a holographic notch filter, and an 1,800-grooves/mm dispersive grating.

The excitation line of an air-cooled, frequency-doubled, He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) was focused through a 20× objective onto the samples, and Raman scattering was back collected through the same microscope objective. Power at the samples was kept very low (never exceeding a few mW) by a series of neutral density filters in order to avoid any thermal damage.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 17.59).