Cat. 15

Chrysanthemums

1881/82

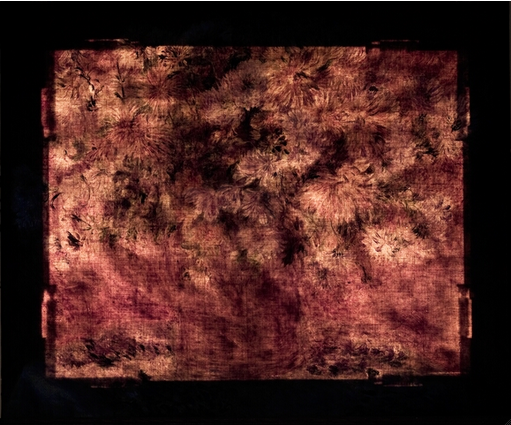

Oil on canvas; 54.8 × 65.8 cm (21 5/8 × 25 7/8 in.)

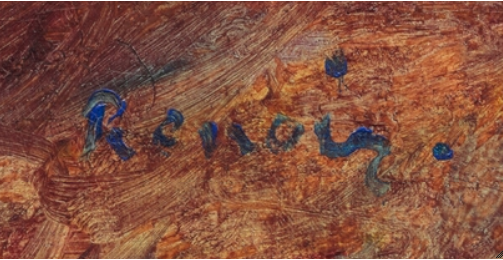

Signed: Renoir. (upper right, in dark-blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1173

Chrysanthemums in Relation to Renoir’s Floral Still Lifes

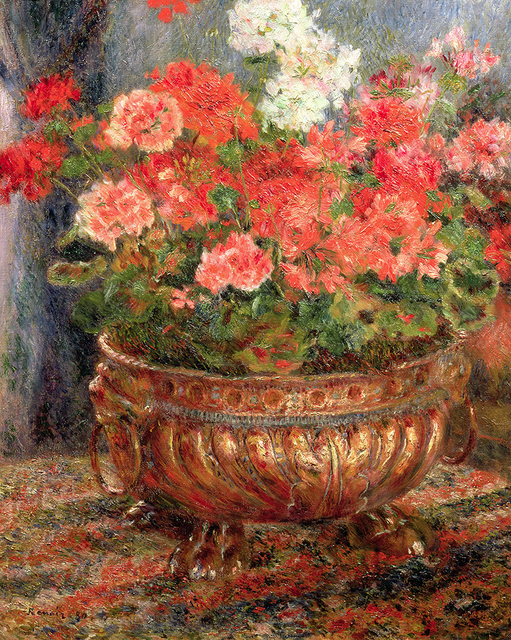

In the fall of 1881 Renoir visited Italy, and the clearer structure of Chrysanthemums reveals a classicism that emerged in his style following the trip. The bouquet is simply contained in an earthenware crock with little indication of setting. The plain design of the vessel acts as a visual pause between the colorful blossoms and the life-size floral pattern of the tablecloth. The composition exhibits an emphatic geometry: the wide oval of the bouquet fills the canvas symmetrically, is reinforced by the central position of the crock, and is echoed in the curve of the table. The painting can be understood as a transitional work between the more spontaneous Impressionism of Peonies (fig. 15.1 [Dauberville 36]), circa 1880, and floral still lifes such as Bouquet of Chrysanthemums (fig. 15.2 [Dauberville 38]), assigned to 1881.

While Renoir’s still-life work remains an under-studied aspect of his career, the sheer number of documented canvases in this genre indicates how significant a role they played in his development. The catalogue for his first retrospective exhibition, held on the boulevard de la Madeleine in April 1883, includes six still-life paintings among seventy works. The proportion of still-life paintings to work in other genres remained roughly the same in his retrospective exhibition organized by the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in 1892. Three of the still lifes in the 1883 exhibition were identified as specific varieties of flowers: Pivoines, no. 34 (likely Peonies, c. 1880 [Dauberville 36]); Géraniums, no. 55 (fig. 15.3 [Dauberville 35]); and Lilas, no. 64 (Lilacs, 1878 [Dauberville 32]). Durand-Ruel bought Chrysanthemums from Renoir in December 1882.

Chrysanthemums makes no reference to setting and may represent one of the bouquets that the artist loved to keep in his home to paint when the impulse came upon him. A light source from the left casts a blue shadow on the wall to the right. This shadow closely follows the curved line of the table suggesting it is located in a circular nook of the kind found in the entrance halls of middle class homes. The table itself is quite small relative to the vase and therefore could only be a side table. Its diameter matches almost exactly the breadth of the floral bouquet.

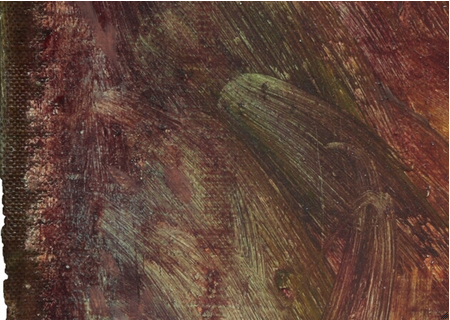

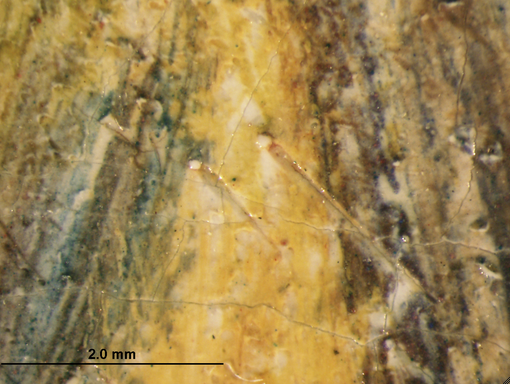

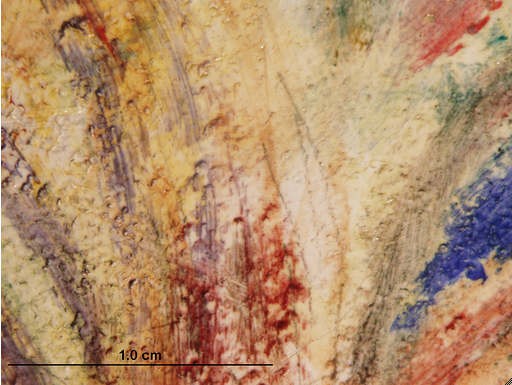

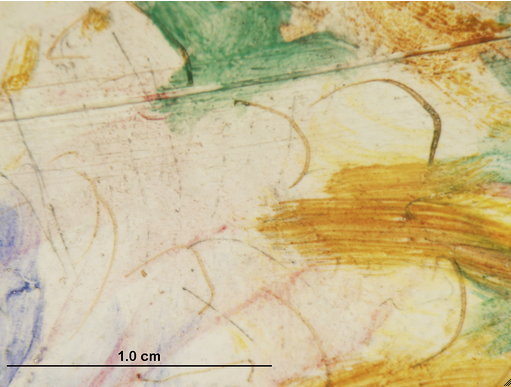

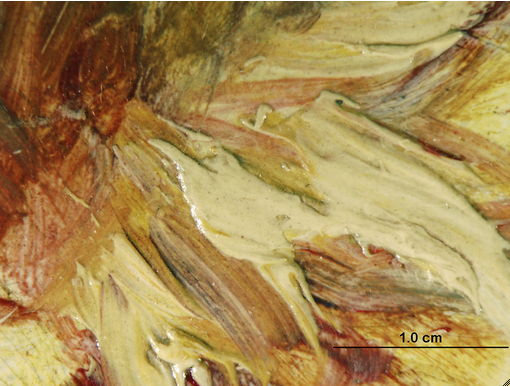

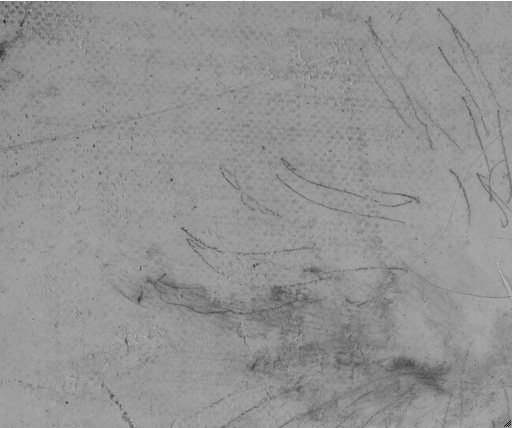

There is a balanced distribution of white and orange blossoms across the bouquet in Chrysanthemums, while the crock and the patterned tablecloth seem thoughtfully chosen for how they complement the composition. There is, however, a certain casualness about the preparation and execution of this canvas. The application of the commercial ground layer is uneven, and the palette knife used to spread it on the canvas caused lumps of already dry material to leave gouged lines in the surface (see Preparatory Layers in the technical report). A number of these are quite prominent (fig. 15.4). Renoir simply painted over them and carried on. Traces of graphite underdrawing are apparent in skips in the upper paint layers. While thin curved lines of brown underdrawing, executed directly on top of the ground, are visible in many areas; the brown lines vaguely outline the form of short, curved petals (fig. 15.5). The underdrawing is selective and Renoir’s rendering of individual blossoms appears intended to rehearse their linear rhythm and assess relative proportions directly on canvas.

Chrysanthemum: Flower of the Artist-Gardener

As Chrysanthemums attests, Renoir’s interest in the flower as an artistic subject can be dated to at least the early 1880s. He may have had the opportunity to admire paintings of the flower by Claude Monet made in 1878 and 1881. A bouquet of chrysanthemum blossoms provides an extraordinarily ebullient setting for Renoir’s painting of the red-haired model Jeanne Samary, A Girl with a Fan, circa 1881 (fig. 15.6 [Daulte 360; Dauberville 344]). In this case the flowers complement the taste for Japonisme suggested by the fan in Samary’s hand.

First imported to France from the Far East during the French Revolution, chrysanthemums are a late summer flower appreciated for their strong scent and exceptional range of color and shape. Referenced in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past), in the early twentieth century they were still considered an exotic Japanese feature of French gardens. Notably, Renoir’s Chrysanthemums includes two blossom varieties, each with different color and petal shape—the orange starburst variety with a long, straight petal and the white blossom variety with a shorter, denser petal that gives it a spherical appearance. This mixture of blossom varieties is a feature of the celebrated Japanese woodblock print by Hokusai, Chrysanthemums and Bee (fig. 15.7) and further adds to the Japonisme of Renoir’s painting. In Hokusai’s print the distinctive flat leaf of the chrysanthemum provides visual contrast with the intricate blossoms. The leaf plays an analogous role in Renoir’s Chrysanthemums, which takes full advantage of the color and textural potential of the celebrated flower to produce a still-life painting of sublime authority.

The Still Life as a Study in Color

While his floral still lifes remained popular with collectors, commercial concerns were not Renoir’s only motivation for painting them. Sympathetic critics recognized that his floral still lifes embodied a truly progressive approach to painting. As Renoir’s German biographer, Julius Meier-Graefe, wrote in 1912, Renoir’s flower paintings were like fictions of color that possessed an “immaterial completeness” quite independent from reality. Such an expressive freedom is amply demonstrated in the brushwork of the bouquet in Chrysanthemums, which is feathery and gestural. Another of his biographers, Georges Rivière, a close friend from the early 1870s, recorded the artist’s explanation for why floral still lifes afforded the opportunity for risk-taking: “Painting flowers is a form of mental relaxation. I do not need the concentration that I need when I am faced with a model. When I am painting flowers I can experiment boldly with tones and values without worrying about destroying the whole painting. I would not dare to do that with a figure because I would be afraid of spoiling everything. The experience I gain from these experiments can then be applied to my painting.”

Indeed, a bold experimental approach to floral still-life painting can be seen throughout Chrysanthemums, in the chromatic links that unify the composition and establish a tonal theme. Red, orange, and yellow predominate, with white, blue, and green acting as counterbalance. The intermingling of orange and white blossoms across the bouquet makes the unusual choice of a russet tone for the background less unsettling. Renoir draws upon the ability of the eye to mix colors near one another. Yellow is used for the blossoms, areas of dappled sunlight on the tablecloth, and to brighten the part of the vase facing the light source. Red is used for the background as well as to highlight the radiating line of petals in the yellow blossoms to give them an orange appearance (fig. 15.8). The blues of the tablecloth also appear in the deeper shadows of the bouquet as well as defining the petals of the white blossoms. Julie Manet, the daughter of Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, who was under the guardianship of Renoir and Edgar Degas after her mother died in 1895, wrote in her diary, “M. Renoir said that one should paint still lifes in order to learn to paint quickly.” If speed was a concern for the artist in painting Chrysanthemums, it was also an opportunity to demonstrate his consummate skill as a colorist.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

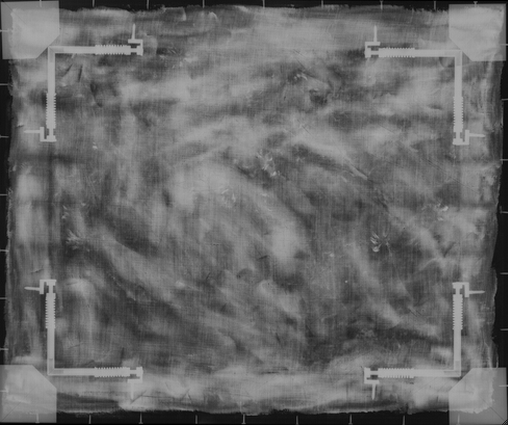

This painting is executed on a very rough, unevenly applied preparation layer on a standard-size [glossary:canvas]. The presence of a color merchant’s stamp and standard-size number on the verso of the support may indicate that the canvas was stretched by the [glossary:color merchant], but it is unclear who applied the preparation. The [glossary:ground] layer covers the compositional area only and appears very uneven in the [glossary:X-ray] and along the edges. It contains many particulates, probably clumps of dried preparation that were dragged across the surface during application with a [glossary:palette knife], resulting in large gouges; these characteristics may logically point to artist application. However, the composition of the ground, containing a moderate amount of calcium-based extenders, and the presence of the stamps on the verso argue strongly for a color merchant’s preparation. Immediately on top of the ground, Renoir drew some compositional elements in a few different types of media, including individual bloomed chrysanthemums in very fine graphite lines, curving petals of other flowers in dilute brown paint, and possibly the outline of the earthenware crock as a first step of the painting process. The artist did not follow the drawing exactly, but the forms and placement are consistent. In one white flower (above center), the brown [glossary:underdrawing] lines were left exposed on white ground and articulate individual petals. It also appears that the artist painted areas of the background before finishing the flowers, bringing in additional background colors to immediately surround the petals and adding final touches to the flowers over that background at a later stage. In other areas, the background seems to have overlapped white flowers and the artist wiped these colors away, leaving a thin shadowy film in the depressions of the canvas. Edges between major still-life elements, such as the table and pitcher/vase, were blended with the background, and paint was often applied [glossary:wet-in-wet] and mixed on the surface. The work is currently varnished, however it is unclear whether the artist would have varnished this painting.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 15.9).

Signature

Signed: Renoir. (upper right, in dark blue paint) (fig. 15.10, fig. 15.11).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

Standard format

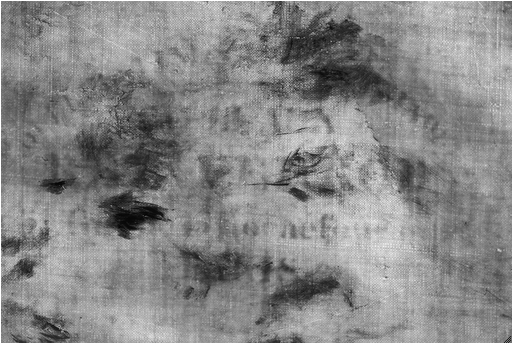

The original dimensions of the canvas were 54.5 × 65.2 cm, according to pretreatment measurements. This corresponds to a no. 15 portrait ([glossary:figure]) standard-size (65 × 54 cm) canvas, turned horizontally. The size 15 stamp visible in transmitted infrared is now behind the right side of the painting (fig. 15.12).

Weave

[glossary:Plain weave]. Average [glossary:thread count] (standard deviation): 29.7V (0.7) × 27.3H (0.9) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the [glossary:warp] and the horizontal threads to the [glossary:weft].

Canvas characteristics

There is strong [glossary:cusping] on all four sides corresponding to original tack placement. Along with the presence of [glossary:priming] only in the compositional area, the strength of this cusping suggests the canvas was stretched before it was prepared.

Stretching

Current stretching: The canvas was lined and restretched in 1972 (see Conservation History), and the dimensions were increased slightly on all sides.

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed 3–3.5 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Current stretcher: Four-member redwood [glossary:ICA spring stretcher]. Depth: 2.7 cm

Original stretcher: Description, construction and labels taken from the previous [glossary:stretcher] suggest it was original. It was a four-member, keyable, mortise-and-tenon stretcher. Depth: Approximately 1.8 cm.

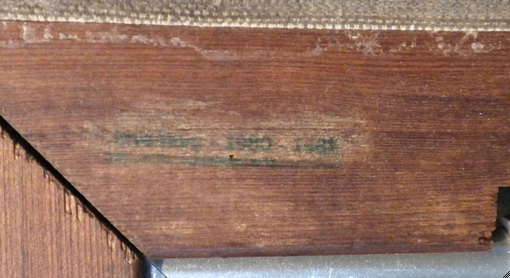

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Stamp

Location: canvas verso (covered by lining)

Method: stamp/stencil

Content: [. . .] FINES [. . .] / TABLEAUX / REY [A] PERROD / [51] Rue de la Rochefoucau[ld] / PARIS (fig. 15.13)

Stamp

Location: canvas verso (covered by lining)

Method: stamp/stencil

Content: 15 (fig. 15.14)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

Ground application/texture

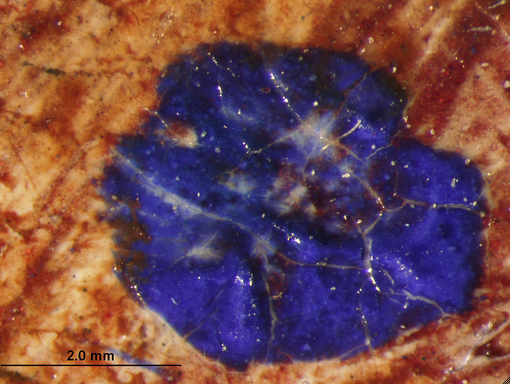

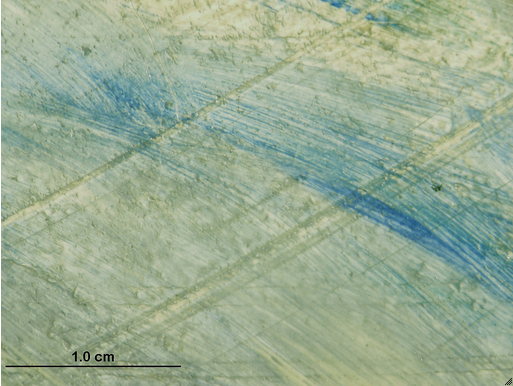

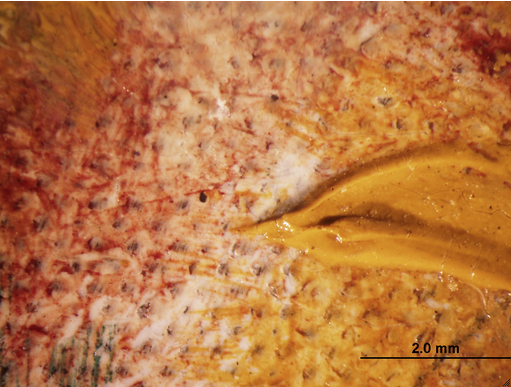

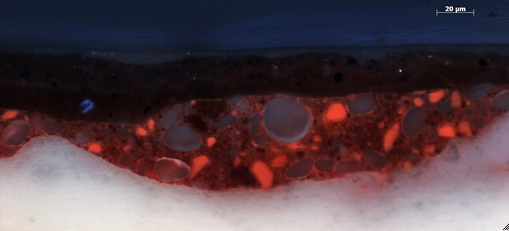

The ground is applied rather unevenly to the compositional area only; it is a single layer ranging approximately 60–220 µm in thickness. The uneven coverage and lack of priming on the [glossary:tacking margins] would tend to suggest an artist-application, however analytical evidence suggests the ground was applied by the color merchant. The nature of the rough edges around the perimeter, abrupt changes in density seen in the X-ray, and various scrape marks on the surface suggest application with a palette knife (fig. 15.15); in some areas, the initial working in with the palette knife was followed by a brush to smooth the texture and extend the priming farther toward the edges (fig. 15.16). The ground itself is granular in nature, with large, chunky white inclusions (fig. 15.17) dragged across the surface during preparation, resulting in curvilinear gouges throughout (fig. 15.18). In some areas, the X-ray indicates that these particles remain in the paint film and appear as radio-opaque spots at the ends of individual gouges. The thickness of the ground varies throughout: in some areas, it was so heavily pressed into the canvas with the palette knife that the tops of the canvas threads are exposed (fig. 15.19).

Color

[glossary:Stereomicroscopic examination] of the surface and [glossary:cross sections] confirms that the ground is white, with no additional or colored particles visible (fig. 15.20).

Materials/composition

The ground is predominantly lead white with moderate amounts of calcium carbonate (probably chalk), and traces of alumina and complex silicates (clays). The [glossary:binder] is estimated to be [glossary:oil].

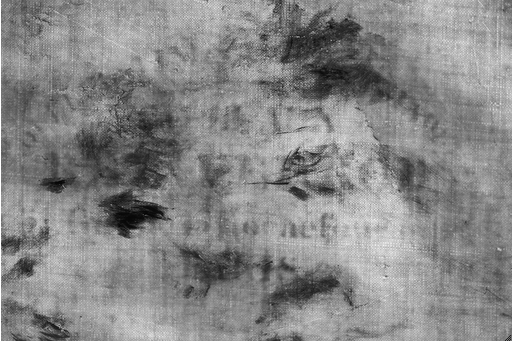

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

Microscopic and infrared examinations indicate that the artist drew a number of the individual chrysanthemums and other flowers. Examination of the work in transmitted light shows that he outlined the earthenware crock, but it is unclear whether this was a separate step in compositional planning or the beginning of the painting stage (fig. 15.21).

Medium/technique

Some of the individual yellow chrysanthemums with long, tapering petals are articulated with very fine [glossary:graphite] lines (fig. 15.22). Elsewhere the artist used graphite and thin brown paint to establish the curving edges of at least one white flower (above center) (fig. 15.23). Transmitted light indicates that Renoir also painted the outline of the crock prior to painting the full composition. However, the upper paint layers have obscured the color and texture of these lines.

Revisions

While Renoir did not follow the fine graphite lines exactly, the individual petals are quite close to the original drawing (fig. 15.24). In some areas, the brown underdrawing lines were left exposed against the white ground, and it is unclear whether they were used regularly throughout. The artist followed the initial outline of the vase/pitcher in the final composition, smoothing the transition between the object and the background as he painted.

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

It appears that the artist established, through various methods of underdrawing, the space for the still-life elements before painting them. The artist painted the background with stiff-bristle brushes and dilute paint (fig. 15.25), leaving a roughly ovular space for the flowers. He brought in the remaining background with finer strokes to meet the still life once these elements were painted; in these areas the background has a somewhat mottled appearance. In some areas, the ground was left exposed to serve as the white body of the flowers, and thin background paint was wiped away from the edges in some areas while it was still wet. This process left a thin film that settled into the depressions of the canvas weave and the gritty, gouged texture of the preparation, visually functioning as shadow (fig. 15.26). Over this, additional paint, colors, and white [glossary:impasto] were added, sometimes wet-in-wet with the background or while the background was not quite dry. In some areas, like the left side of the tablecloth, the artist added paint to the object edge when he brought the background in to create a soft, blended transition.

The paint throughout varies from very thin areas of the background and initial indications of the flowers to heavy impasto in the final stages (fig. 15.27). Individual colors were applied wet-in-wet over their surroundings, using fine brushes to create visually complicated and finely articulated flower petals (fig. 15.28).

Painting tools

Mostly fine, soft brushes for the individual flower petals and wider, stiff-bristle brushes for the background with strokes up to 1 cm wide; palette knife for ground application.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following [glossary:pigments]: lead white, cobalt blue, malachite, viridian, black, iron oxide red and/or yellow, vermilion, carmine lake, second red lake, zinc yellow, cadmium yellow and Naples yellow

[glossary:UV] examination indicates that Renoir used salmon-fluorescing red lake throughout the chrysanthemums and other flowers and in broad areas of the background (fig. 15.29). [glossary:Cross-sectional analysis] of a sample taken from the background indicates the artist also used a second, non fluorescing red lake. As the sample analyzed contained both red lakes, it is unclear whether carmine lake is the fluorescing or non fluorescing variety (fig. 15.30).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The painting has a [glossary:synthetic varnish], applied in 1972, with residues of natural resin in areas of impasto. Treatment notes from 1972 mention removal of [glossary:overpaint] and a discolored [glossary:natural-resin varnish] (see Conservation History). It is unclear if this [glossary:varnish] was original.

Conservation History

The first documented treatment occurred in 1972. At that time, the painting was described as stretched on a four-member stretcher with a [glossary:hardboard] insert between the painting and the stretcher. Pretreatment conditions also included abrasion, shrinkage cracks, and minor losses with overpaint to hide these damages. The presence of the hardboard and overpaint suggest the painting had been treated in the past. During the 1972 treatment, grime, varnish, and the hardboard mounting were removed, and the work was faced with mulberry fiber paper and starch paste in preparation for [glossary:lining]. The old six-member stretcher was discarded when the work was wax-resin lined, and the lined painting was tacked onto a four-member redwood ICA spring stretcher of slightly larger dimensions (21 1/2 × 25 3/4 in.). The work was inpainted with methacrylate paints and given three coats of synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, and a final coat of AYAA).

Condition Summary

Widespread cracking, with some associated tenting, appears to come from the ground, rather than from interlayer [glossary:cleavage] between the ground and the paint. There are minimal localized losses in areas where cracks intersect; most have been filled and inpainted. The lining is in good condition, keeping the work relatively planar and with no delamination. The wax-resin lining material has saturated the support, making the canvas appear very dark; however, the thickness of the ground and subsequent paint layers make this affect less apparent in the compositional area. The rough perimeter, resulting from uneven preparation, has been heavily retouched in an attempt to “square” the composition and compensate for the extended dimensions resulting from the 1972 treatment. The work has a glossy synthetic varnish.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

The current frame appears to be original to the painting. It is a French (Paris), late-nineteenth-century, Durand-Ruel, Régence Revival, gilt ogee frame with cast foliate ornament, center and corner cartouches, and a gilt fillet liner. The frame has water and oil gilding over bole on cast plaster and gesso. The bole color is varied throughout the frame. There is red-orange bole on the sanded frieze and fillets, and red bole on the perimeter molding, sight molding, liner, and scotia sides on the ogee face. The scotia sides and liner are burnished, and the cast foliate ornament and sight molding are selectively burnished. The quadrillage bed on the ogee face has been rubbed selectively to expose the underlying plaster. The gilding is toned with a casein or gouache raw umber [glossary:wash] and gray overwash. The frame has a glued pine substrate with a cast plaster face. At some point in the frame’s history, the original verso was planed flat, removing all construction history and provenance, a back frame was added, and all back and interior surfaces were painted. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is fillet with stylized dovetail-pierced egg-and-flower outer molding; scotia side; ogee face with cast foliate and flower ornament on a quadrillage bed, and center and corner foliate scroll cartouches with cabochon centers on a diamond bed; sanded front frieze bordered with fillets; ogee with stylized leaf-tip-and-shell sight molding; and an independent flat fillet liner with cove sight edge (fig. 15.31).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris, Dec. 14, 1882, for 600 francs.

Transferred by Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, 1897.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, Feb. 17, 1915, for $7,500.

Bequeathed by Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Exhibition History

Possibly Paris, Grand Palais, Salon d’automne, Oct. 15–Nov. 15, 1904, cat. 30, as Chrysanthèmes.

Possibly New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by Pierre Auguste Renoir, Nov. 14–Dec. 5, 1908, cat. 12, as Chrysanthèmes, 1882.

New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 7–21, 1914, cat. 1.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, May 23–Nov. 1, 1933, cat. 340. (fig. 15.32)

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress” Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture for 1934, June 1–Oct. 31, 1934, cat. 228.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 39 (ill.).

Pasadena, Calif., Norton Simon Museum of Art, Jan. 27–Oct. 31, 1978, no cat.

Tokyo, Isetan Museum of Art, Exposition Renoir, Sept. 26–Nov. 6, 1979, cat. 33 (ill.); Kyoto Municipal Museum, Nov. 10–Dec. 9, 1979.

Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, June 27–Aug. 31, 1980, cat. 22 (ill.).

Santa Barbara (Calif.) Museum of Art, Sept. 13, 1984–June 7, 1985, no cat.

Tokyo, Seibu Museum of Art, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], Oct. 18–Dec. 17, 1985, cat. 38 (ill.); Fukuoka Art Museum, Jan. 5–Feb. 2, 1986; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, Mar. 4–Apr. 13, 1986.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago’s Dream, a World’s Treasure: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1893–1993, Nov. 1, 1993–Jan. 9, 1994, not in cat.

Fort Worth, Tex., Kimbell Art Museum, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, June 29–Nov. 2, 2008, cat. 35 (ill.).

Selected References

Possibly Société du Salon d’Automne, Catalogue de peinture, dessin, sculpture, gravure, architecture et arts décoratifs, exh. cat. (Hérissey, 1904), p. 115, cat. 30.

Possibly Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings by Pierre Auguste Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1908), no. 12.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 162, cat. 2154.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute (Continued),” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 4 (Apr. 1925), pp. 47, 48 (ill.).

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für Freunde und Sammler der Kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 78. Translated by C. C. H. Drechsel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture; Lent from American Collections, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1933), p. 49, cat. 340.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), p. 39, cat. 228.

Art Institute of Chicago, An Illustrated Guide to the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1945), p. 36.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 397.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 130, pl. 118; 177.

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), p. 111; 112, cat. 505 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 74; 106–07, cat. 39 (ill.); 126; 210; 211; 214.

Isetan Museum of Art and Kyoto Municipal Museum, Exposition Renoir, exh. cat. (Isetan Museum of Art/Kyoto Municipal Museum/Yomiuri Shimbun Sha, 1979), cat. 33 (ill.).

Musée Toulouse-Lautrec and Art Institute of Chicago, Trésors impressionnistes du Musée de Chicago, exh. cat. (Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, 1980), pp. 40, no. 22 (ill.); 68.

Art Institute of Chicago, Seibu Museum of Art, Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, and Fukuoka Art Museum, Shikago bijutsukan insho-ha ten [The Impressionist tradition: Masterpieces from the Art Institute of Chicago], trans. Akihiko Inoue, Hideo Namba, Heisaku Harada, and Yoko Maeda, exh. cat. (Nihon Nippon Television Network, 1985), pp. 84, cat. 38 (ill.); 85 (detail); 148 (ill.).

Nagoya City Art Museum, Renoir Retrospective, exh. cat. (Nagoya City Art Museum/Chunichi Shimbun, 1988), pp. 72, 239.

Gerhard Gruitrooy, Renoir: A Master of Impressionism (Todtri, 1994), p. 52 (ill.).

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 56–57; 63 (detail); 95, pl. 14; 110.

M. Therese Southgate, “The Cover,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 281, 7 (Feb. 17, 1999), cover (ill.); p. 591 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), p. 76 (ill.).

Aviva Burnstock, Klaas Jan van den Berg, and John House, “Painting Techniques of Pierre-Auguste Renoir: 1868–1919,” Art Matters: Netherlandish Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005), pp. 52, 54.

Flavie Durand-Ruel, “Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) et Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922), son ami et marchand,” Renoir et les familiers des Collettes, exh. cat. (Trulli, 2008), p. 89 (ill.).

Galeries Nationales, Grand Palais, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir au XXe siècle, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2009), p. 103 (ill.).

Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Renoir in the Twentieth Century, exh. cat. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Philadelphia Museum of Art/Hatje Cantz, 2010), p. 103 (ill.).

Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Impressionists: Master Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago/Kimbell Art Museum, 2008), p. 83, cat. 35 (ill.). Simultaneously published as Gloria Groom and Douglas Druick, with the assistance of Dorota Chudzicka and Jill Shaw, The Age of Impressionism at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2008), p. 83, cat. 35 (ill.).

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins et aquarelles, vol. 2, 1882–1894 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2009), p. 15, cat. 701 (ill.).

Sylvie Patin, “De la nature morte au paysage,” in Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Claude Monet, 1840–1926, exh. cat. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Musée d’Orsay, 2010), p. 223.

Colin B. Bailey, Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting, exh. cat. (Frick Collection/Yale University Press, 2012), p. 103, fig. 19.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel, Paris, 2650, Paris stock années 1880/84

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1787

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel, New York, 1721

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel New York A 652

Other Documents

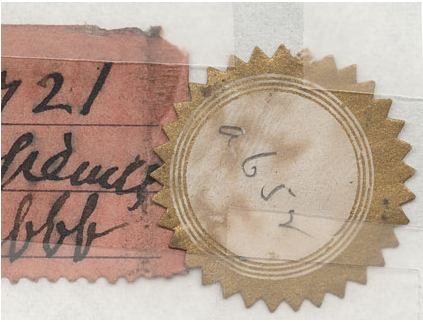

Label (New York stock no. 1721) (fig. 15.33)

Label (no. A652) (fig. 15.34)

Purchase receipt

Letter

E. C. Holston to Martin A. Ryerson, dated Chicago 11 [sic], 1915

Letter

Joseph Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel, New York, to Georges Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel, Paris, Feb. 16, 1915

Labels and Inscriptions

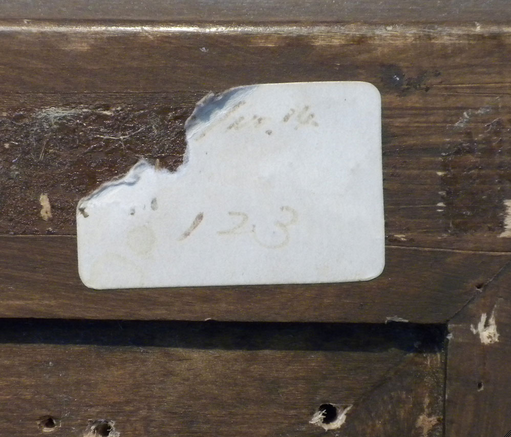

Undated

Label

Location: frame

Method: handwritten script (faded) on white label

Content: . . . [. . .] 4 . . . 123 (fig. 15.35)

Inscription

Location: frame

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: 33.1173 (fig. 15.36)

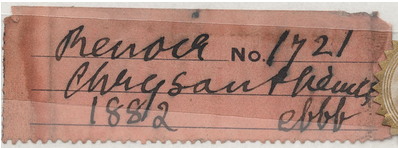

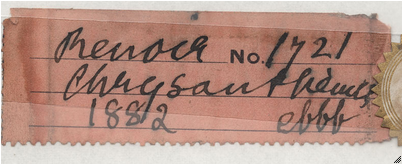

Pre-1980

Label

Location: previous stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script on brown label

Content: Renoir No. 1721 / Chrysanthèmes / 1882 ebbb (fig. 15.37)

Label

Location: previous stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: handwritten script (graphite) on white and gold label

Content: a652 (fig. 15.38)

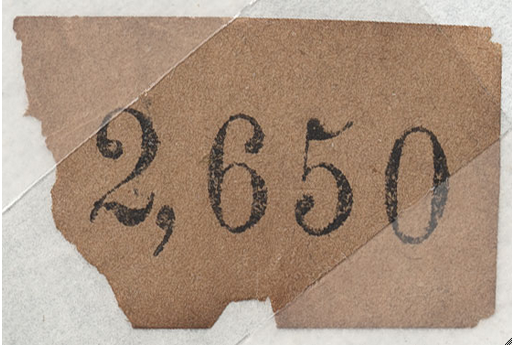

Label

Location: previous stretcher (discarded); preserved in conservation file

Method: stamped (?) number on craft paper label

Content: 2,650 (fig. 15.39)

Stamp

Location: canvas verso (covered by lining); preserved as a tracing in conservation file

Method: stamp/stencil

Content: [. . .] FINES [. . .] / TABLEAUX / REY [A] PERROD / [51] Rue de la Rochefoucau[ld] / PARIS (fig. 15.40)

Stamp

Location: canvas verso (covered by lining)

Method: stamp/stencil

Content: 15 (fig. 15.41)

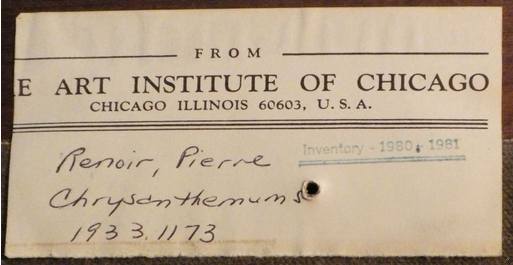

Post-1980

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script and blue stamp on printed white label

Content: FROM / [TH]E ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / Renoir, Pierre / Chrysanthemums / 1933.1173 / [right side, blue stamp] Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 15.42)

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp (partially removed)

Content: [Inventory]—1980–1981 (fig. 15.43)

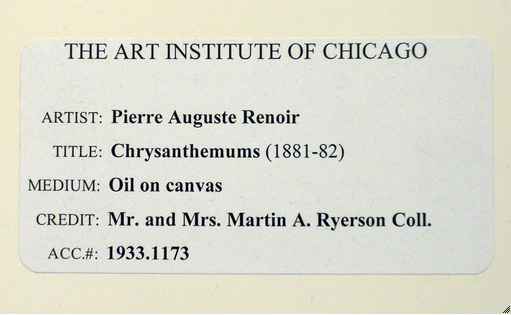

Label

Location: [glossary:backing board]

Method: printed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / ARTIST: Pierre Auguste Renoir / TITLE: Chrysanthemums (1881–82) / MEDIUM: Oil on canvas / CREDIT: Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Coll. / ACC#: 1933.1173 (fig. 15.44)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and [glossary:transmitted-light] overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (Kodak Wratten 2E filter, PECA 918 UV/IR interference cut filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and [glossary:cross-sectional analysis] were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/[glossary:UV fluorescence] and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: [glossary:darkfield], brightfield, differential interference contrast ([glossary:DIC]), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state [glossary:BSE] detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Raman Spectroscopy and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

A Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope was used, equipped with an Andor multichannel, Peltier cooled, open-electrode charge-coupled device detector (Andor DV420-OE322; 1024×256), an Olympus BXFM open microscope frame, a holographic notch filter, and an 1,800-grooves/mm dispersive grating.

The excitation line of an air-cooled, frequency-doubled, Nd:Yag solid-state laser (532 nm), He-Ne laser (632.8 nm for SERS), or solid-state diode laser (785.7 nm) was focused through a 20×, 50×, or 100× objective onto the samples, and Raman scattering was back-collected through the same microscope objective. Power at the samples was kept very low (never exceeding a few mW) by a series of neutral density filters in order to avoid any thermal damage.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

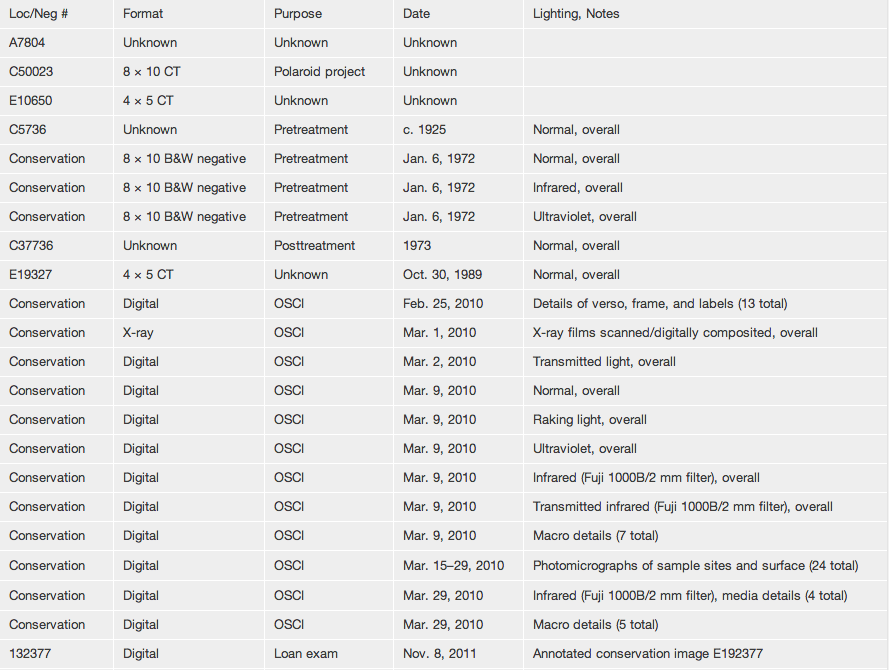

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 15.45).