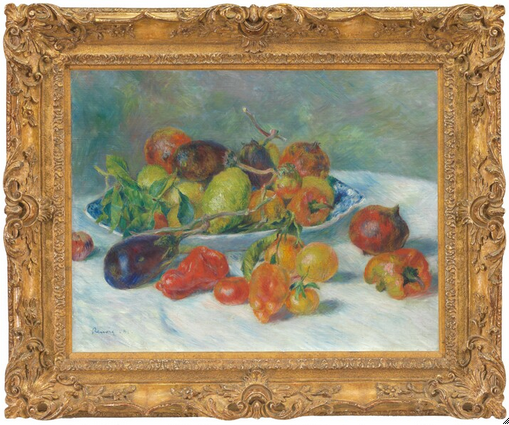

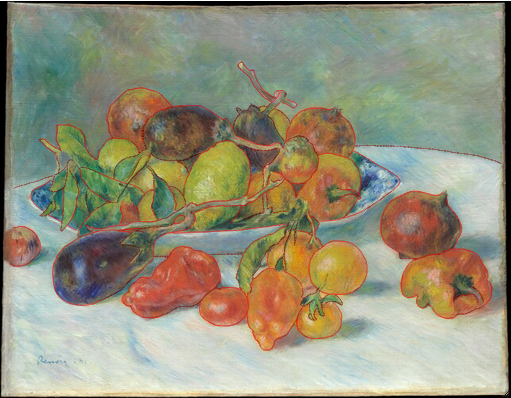

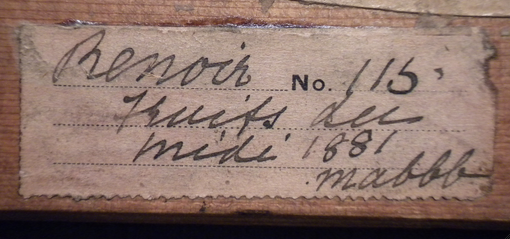

Cat. 14

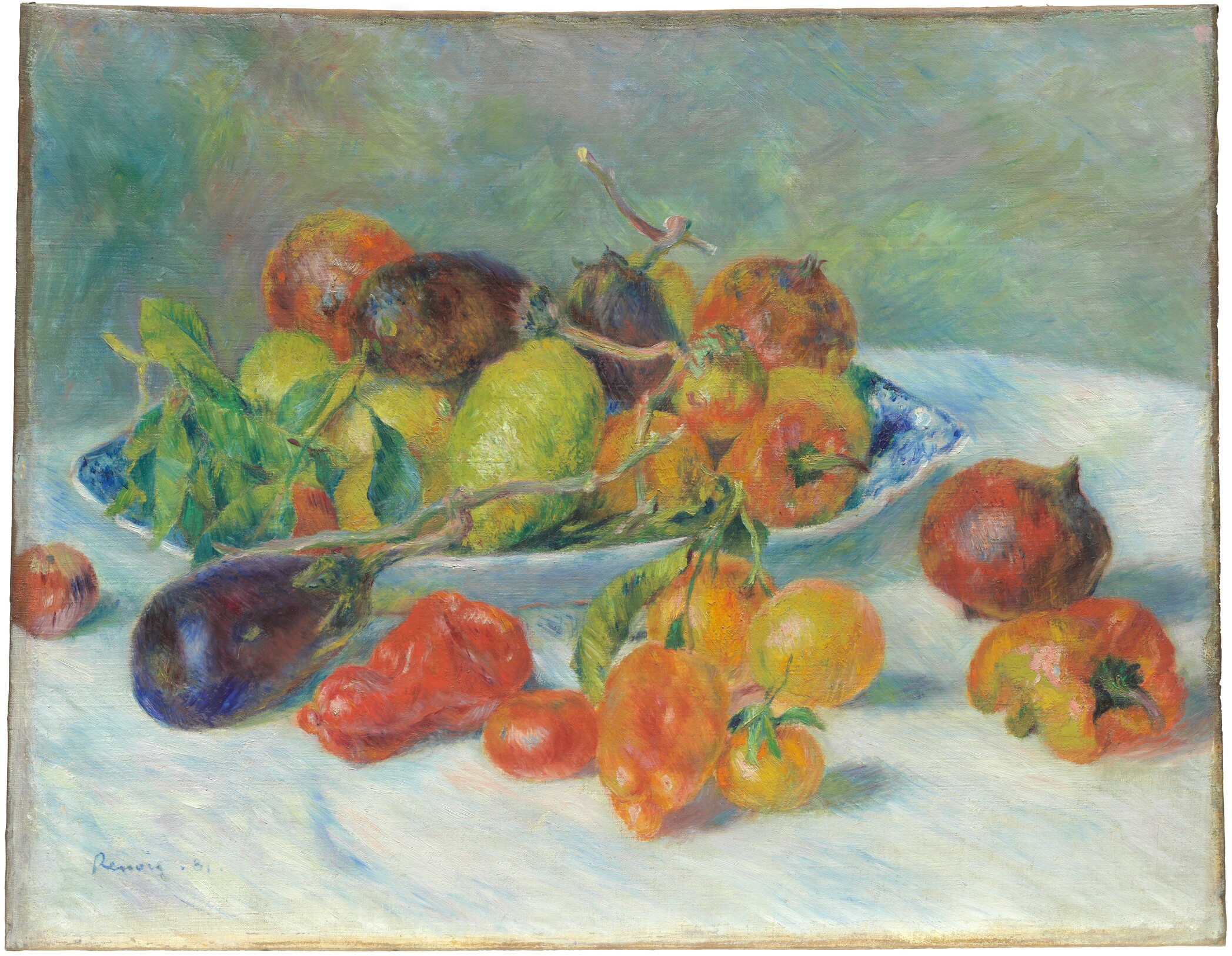

Fruits of the Midi

1881

Oil on canvas; 51 × 65 cm (20 1/16 × 25 5/8 in.)

Signed and dated: Renoir. 81. (lower left, in dark-blue paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1176

Renoir in Southern Italy

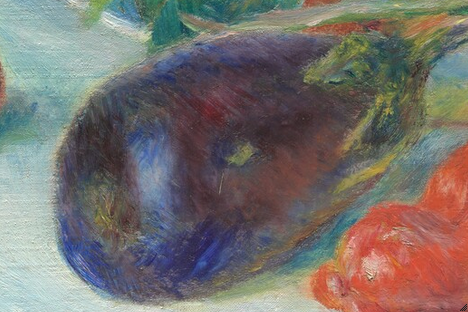

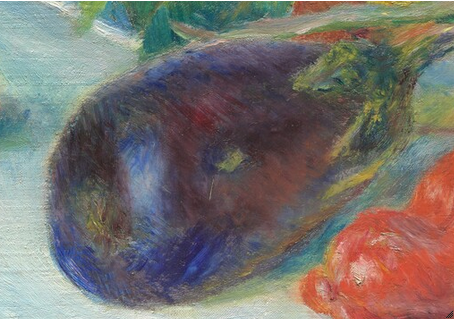

Writing in late November 1881 from Naples to his friend and patron Paul Berard, Renoir revealed a fondness for Italian food: “I’m eating cooking with garlic, which I adore.” Part of his enjoyment of travel was learning about local culture: the distinctive art and architecture but also the cuisine of the region. In Fruits of the Midi the artist paid tribute to the culture of Italy, composing a still life that features the bounty of the warm Mediterranean climate: peppers, eggplants, tomatoes, pomegranates, citrons, lemons, and oranges.

In Italy Renoir was as much captivated by everyday life and the effects of light on the landscape as he was with the Old Master and Renaissance treasures that were the primary objective of the trip. It was probably his interest in experiencing the everyday that led him to visit the region of Calabria, located at the toe of the boot, then one of the most impoverished and undeveloped parts of the country. Renoir found “wonders” in this little-visited destination, with its age-old traditions and an economy unspoiled by modern industry.

Though the Chicago still life is rustic in subject, Douglas Druick has suggested that it reflects the classical sense of calm and monumentality that Renoir encountered in the Old Master paintings he saw in Rome. “There is an austerity here that is new in the art of Renoir, signaled by the relative plainness of both tablecloth and background.”

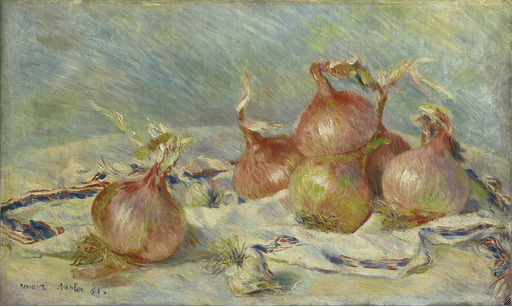

Still-Life Companions

Barbara White was the first scholar to identify Fruits of the Midi as one of the two still lifes that Renoir mentioned in a letter to his friend and patron Charles Deudon, written in Naples in late November or early December 1881: “I am going to send in a few days one or two still lifes; there is one that is good.” The other painting is undoubtedly Onions (fig. 14.1 [Dauberville 58]), inscribed and dated “Naples. 81.” The two are closely related in subject matter, handling, use of color, and compositional arrangement. Both were purchased by the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in May 1882 as part of a group of seventeen works produced during 1881–82. The Chicago still life was almost certainly the work in this group titled Fruits du midi.

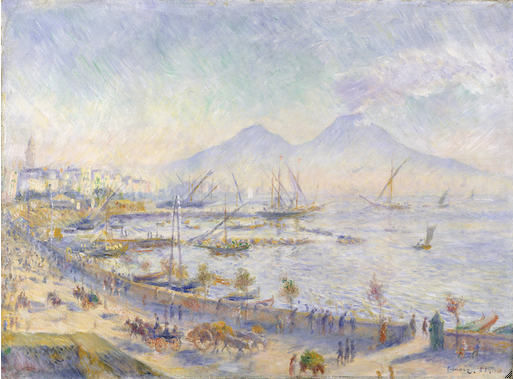

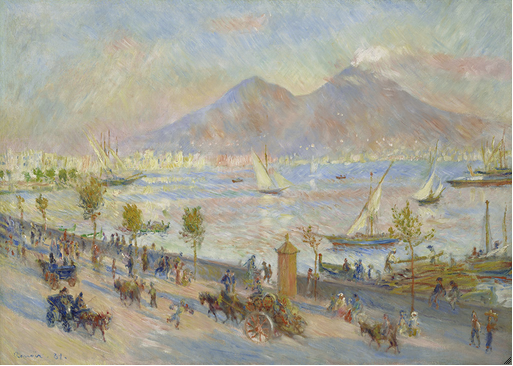

These two paintings could be pendants, if not for the difference in size and format: Fruits of the Midi corresponds to a no. 15 landscape (paysage) standard-size canvas (65 × 50 cm), and Onions to a slightly smaller no. 12 seascape (marine) standard-size canvas (60 × 38 cm). Both works reflect a firm, carefully delineated modeling of the still-life elements with generous amounts of paint applied with a controlled brush—quite distinct from the loose handling seen in works of the 1870s or even in the landscapes he was painting at about the same time, The Bay of Naples (Morning) (fig. 14.2 [Dauberville 166]) and The Bay of Naples (Evening) (fig. 14.3 [Dauberville 167]). In both still lifes, Renoir contrasted textures and colors: the papery skins of the onions topped with the crinkled line of dried roots are as convincingly portrayed as the deep aubergine of the eggplant and the brilliant sheen of the buckled and seamed red pepper next to it. In each painting, the arrangement is set on a round table covered with a pristine white cloth. The natural light reflecting off the objects suggests that they are near a window receiving plenty of sunlight. Both backgrounds were built up with longer, directional brushwork more in keeping with a looser style of Impressionism and provide little clue as to setting.

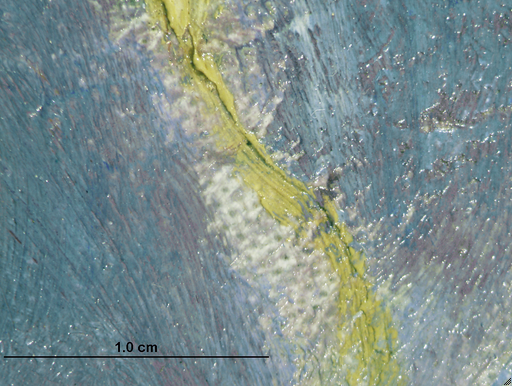

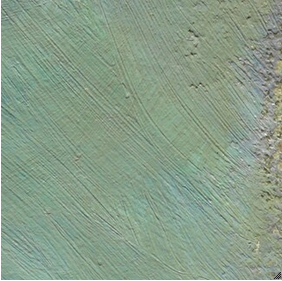

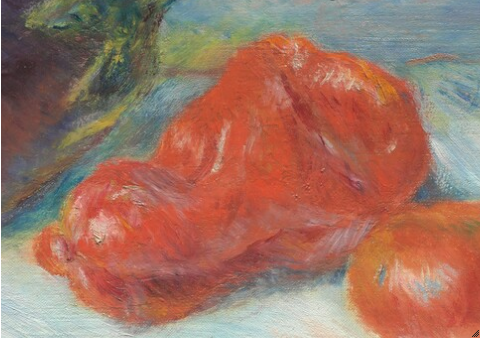

The backgrounds and tablecloths in both paintings are also chromatically harmonized with the still-life objects depicted. The golden yellows of the onions can be seen in muted form throughout the background of Onions, in the same way that the green, mauve, blue, and even red in the background of Fruits of the Midi reflect the richer tones in the eggplant, citron, leaves, and pomegranates. The body and weight of the tablecloth in Fruits of the Midi are suggested by the blending of blue, pink, and mauve, colors found in the still-life objects. Many of the fruits are set upon a platter of traditional design with blue decoration; the onions in turn are collected on a napkin with blue and red trim, while the tablecloth beneath contains yellow highlights that harmonize with the onion skins. Perhaps Renoir was thinking about how Onions and Fruits of the Midi might complement each other when he painted over the original blue, lavender, and mauve in the background of Fruits of the Midi (still visible at the edges of the painting; fig. 14.4) with lighter green and yellow.

Finally, Onions and Fruits of the Midi exhibit a complementary compositional asymmetry. In Onions the main group of bulbs is gathered to the right, with a stray having fallen free of the group to the left. This grouping is mirrored in Fruits of the Midi, where the platter is placed off-center to the left, with a stray pomegranate and pepper to the right.

Fruits of the Midi was probably included in Renoir’s retrospective exhibition of seventy works organized by Durand-Ruel in April 1883, along with Onions and the two views of the Bay of Naples. While there is no work titled Fruits du midi in the 1883 exhibition catalogue, critical commentary suggests that a still life resembling it was on display. The reviewer for the Journal des artistes wrote of a still life “gathered together, in a jumble, gherkins and peppers in hard and garish colors”—likely mistaking the citrons in Fruits of the Midi for gherkins. These comments were immediately followed by a detailed description of and glowing praise for Onions. Such a disparate critical reaction to the two still lifes may shed light on why Onions was purchased by Durand-Ruel for 700 francs while the larger Fruits of the Midi garnered only 600 francs—the brilliant colors used in the latter painting may have been too unsettling.

Fruits of the Midi and Renoir’s Crisis of Impressionism

In reporting on his crisis of the 1880s to Ambroise Vollard, Renoir recalled that it was in 1883, the year of his retrospective exhibition, that he realized he had reached a dead end with Impressionism and “did not know how to paint or draw.” Two years before that, however, when he set out for Italy in the fall of 1881, Renoir was undertaking a pilgrimage that, while a tradition for generations of French artists, was unusual for an Impressionist and may indicate that he was experiencing uncertainty about his artistic direction. In many letters written during the trip, Renoir conveyed self-consciousness about embarking on such a journey at the age of forty, well into the middle of his career. In one such missive to Madame Georges Charpentier from Venice in October, there is a subtext of wanting to fulfill expectations of new patrons about his artistic education: “I have suddenly become a traveler, seized by the feverish desire to see the Raphaels. I am therefore in the process of taking in my Italy. Now I shall be able to reply firmly, yes, sir, I have seen the Raphaels. I have seen Venise la belle, etc., etc.” As his travels through Italy progressed, Renoir reported that Raphael’s frescoes were “wonderful for simplicity and grandeur,” and he was especially enthusiastic about his discovery of the archaeological museum in Naples and its collection of Roman mural painting.

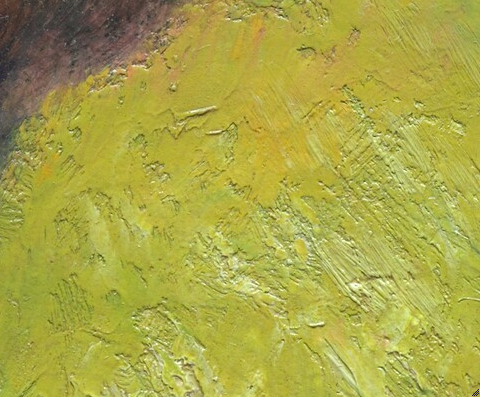

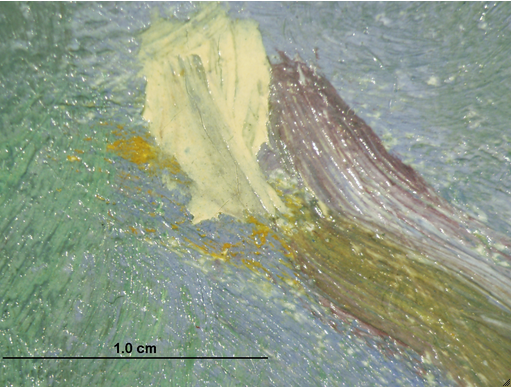

It is tempting to see in the brushwork of Fruits of the Midi and in the solidity of its still-life elements the “progress” that Renoir professed to have made after a long period of searching. A pronounced linear style is evident in how he modeled the still-life forms with a fine brush, following the contours with a pattern of crosshatching and layering to create highlights of pure color, for example, along the curving top of the red pepper in the foreground, just to the left of center (fig. 14.5). In other areas, he blended his colors to convincingly convey light falling on the surfaces of the objects. The varied textures in Fruits of the Midi establish the painting as a brilliantly conceived study in contrasts: the indented and buckled bodies of the peppers; the smooth, tight skins of the bright-red tomatoes; the yellow and green rind of the citron with its realistically nubby appearance. Renoir built up the glistening skin of the eggplant by layering deep translucent reds and blues over a foundation of brilliant mauves and bright reds (fig. 14.6). So carefully did Renoir model his fruits and vegetables within the initial drawing that radiotransparent “outlines” can be seen in the X-ray around the edges of the forms (fig. 14.7). While these still-life elements convey a sculptural presence, the background and tablecloth revert to an Impressionist style with longer strokes from a wider brush.

Fruits of the Midi may well have inspired the following comment by the American artist Marsden Hartley: “I think of Renoir as a great painter of fruit. It always seems like the journey through the sensuous orchard of the aesthetic soul in Renoir. His flesh is eatable—and his vistas and still lifes so strokable.” It is revealing that Renoir’s still life, the colors of which were found to be “garish” in 1883, could inspire a modernist of a younger generation at the turn of the century. While Renoir’s still lifes are often thought of as secondary compared to his figures and landscapes, Fruits of the Midi is clearly the result of careful consideration and amply demonstrates his mastery of color.

John Collins

Technical Report

Technical Summary

Using a standard-size canvas that he probably stretched and primed himself, Renoir began painting the still-life elements in this composition by outlining the major contours in very fluid, thin red paint. He established the still-life elements and largely finished them before adding the background. These forms are marked by their strong edges, both coloristically and sculpturally separated from their surroundings. In some areas, especially in the foreground, a small margin of unpainted ground is left around the objects, where the underdrawing is revealed. The ground itself appears to have been applied with a brush and then heavily worked into the canvas with a palette knife, leaving the thread tops exposed in many areas. The smaller, finer strokes used to build up the still-life elements contrast with the broader, longer diagonals and cross-hatched patterns in the background.

Multilayer Interactive Image Viewer

The multilayer interactive image viewer is designed to facilitate the viewer’s exploration and comparison of the technical images (fig. 14.8).

Signature

Signed and dated: Renoir. 81. (lower left, in dark-blue paint) (fig. 14.9).

The signature was applied in very fluid paint over a dry, heavily textured background and primarily fills the depressions of the brushstrokes (fig. 14.10).

Structure and Technique

Support

Canvas

Flax (commonly known as linen).

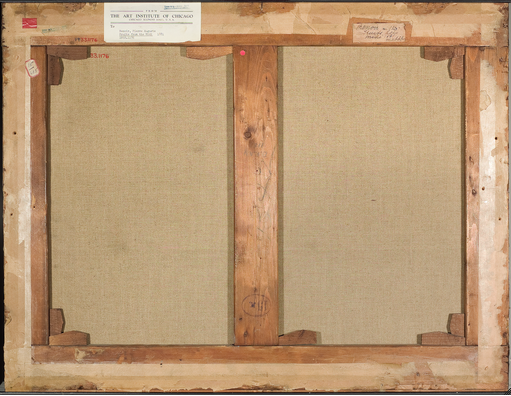

Standard format

The primed area of the canvas is approximately 50 × 64 cm. This closely corresponds to a no. 15 landscape (paysage) standard-size (65 × 50 cm) canvas; this is also the number stamped on the verso of the stretcher (fig. 14.11).

Weave

Plain weave. Average thread count (standard deviation): 22.8V (0.7) × 23.0H (1.1) threads/cm. The vertical threads were determined to correspond to the warp and the horizontal threads to the weft.

Canvas characteristics

The canvas has very strong cusping on all sides, consistent with deformations seen when the canvas is stretched before the ground is applied.

Stretching

Current stretching: The work was lined and restretched at an unknown date, at which time the dimensions were increased slightly on all sides.

Original stretching: Based on cusping visible in the X-ray, the original tacks were placed approximately 6–8 cm apart.

Stretcher/strainer

Though the painting was lined and restretched as part of a previous, undocumented conservation treatment, the patina and standard size stamp suggest that the stretcher is original to the painting (fig. 14.12). It is a five-member, keyable, mortise-and-tenon stretcher with a vertical crossbar. Depth: 1.5 cm.

Manufacturer’s/supplier’s marks

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black ovular stamp

Content: 15 w (fig. 14.11)

Preparatory Layers

Sizing

Not determined (probably glue).

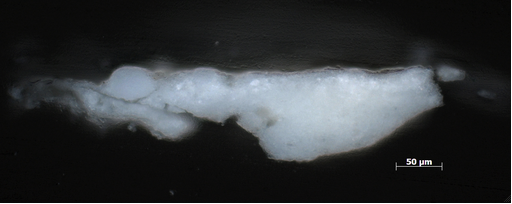

Ground application/texture

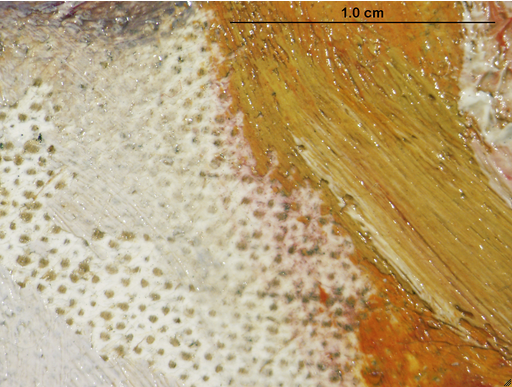

The ground was applied to the compositional area only after the canvas was stretched. It is a single layer with variable thickness ranging approximately 20–90 µm, partially fills the weave, and appears to have been heavily worked into the canvas with a palette knife, leaving the tops of the threads exposed in many areas. The edges are soft and uneven, suggesting that a brush was used to spread the ground after the initial application; the excess was likely removed and the layer smoothed with a palette knife. As the ground contains relatively few extenders and covers only the compositional area, it is possible that it was applied by the artist.

Color

The ground is white; no additional, colored particles were observed under stereomicroscopic examination or cross-sectional analysis (fig. 14.13).

Materials/composition

The ground is lead white with traces of alumina, complex silicates, and some calcium-based white. The binder is estimated to be oil.

Compositional Planning/Underdrawing/Painted Sketch

Extent/character

No underdrawing is observed with infrared reflectography; however, careful stereomicroscopic examination suggests that Renoir may have outlined the major forms in very thin, fluid paint.

Medium/technique

Evidence of underdrawing is visible only microscopically along the edges of forms and suggests that the artist used a very thin red lake (fig. 14.14).

Revisions

As the underdrawing is seen only along the edges of forms and is not seen in infrared reflectography, subsequent paint layers hide any possible changes in this stage of the composition (see Paint Layer).

Paint Layer

Application/technique and artist’s revisions

Renoir painted the still-life elements almost to completion before he brought the background in around them. Instead of blending the edges with the background and moving fluidly between the objects and their environment, Renoir gave each object an accentuated edge, in many cases using both color and texture to do so (fig. 14.15). In some areas, especially the foreground tablecloth and the rising stem in the center, the artist left a small margin of unpainted ground around the objects, increasing the sculptural nature of their edges (fig. 14.16). The light color of the tablecloth atop the white ground allowed these unpainted sections to visually blend with the surroundings. Even many of the smaller elements—the various protruding stems and leaves—appear to have been painted in large part before the background was added. This method of painting makes compositional changes more obvious, especially in the X-ray; these were limited to the possibility of a stem, leaves, or a fold in the tablecloth near the pomegranate on the far right; slight alterations to curve of the foreground eggplant near the stem; and the undersides of the peppers on the far right and to the left of center (fig. 14.17).

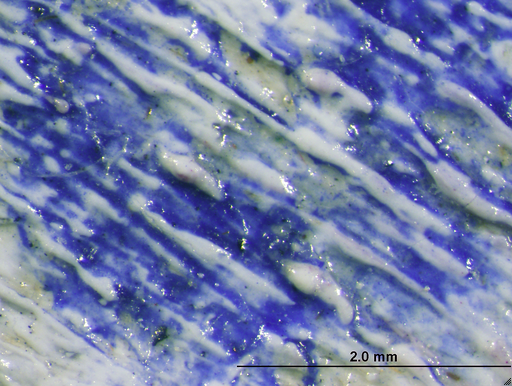

The still-life objects themselves were worked up in a series of paint layers, often incorporating vivid underpainting and wet-in-wet modeling. The appearance of certain objects under normal viewing conditions belies the intricacy of Renoir’s working methods. Looking at the foreground eggplant and the pepper to its right, for example, specifically at the thin, glaze-like layers most evident on the surface, there is little visible information to explain the radio-opacity of these forms in the X-ray, where they appear to be the most heavily painted objects in the composition. The eggplant just left of center atop the pile of fruits appears as expected in the X-ray, indicating that it was probably painted primarily with the glaze-like layers most apparent in the foreground example. Closer inspection reveals that the latter was initially painted in mauves and reds, incorporating radio-opaque vermilion and lead white. These tones acted as an underlayer, over which Renoir applied thin layers of translucent pigments such as red lake and cobalt blue to partially expose the initial colors and give the vegetable’s skin depth and coloristic complexity (fig. 14.18). Elsewhere, Renoir embraced a more heavy-handed approach, using a palette knife, as well as a brush, to spread thick paint containing opaque pigments across the surface, as in the somewhat bumpy surface of the citron in the center (fig. 14.19).

The background is marked by relatively long, directional brushstrokes, which contrast with the short, discrete strokes used in the still-life elements. Renoir changed the tonality of the background, first executing this space in an array of cool blue, lavender, and mauve tones that are still visible along the edges of forms and near the perimeter (fig. 14.20). Looking closely at the stem extending upward near the center, it is possible to see the back-and-forth between the objects and their surroundings: first, the initial paint layers of the stem were laid down, including a bright-yellow highlight; then the cool blue and lavender background colors were brought in around the stem; next the chunky white highlight was daubed atop the stem; and finally the new, greener background was applied (fig. 14.21). The tablecloth is largely made up of diagonal strokes of white, with hints of blue and red lake drawn in wet-in-wet to create soft shadows and folds. The vivid colors used in the still life are reflected in the muted tones of the broadly cross-hatched background.

Painting tools

Soft and medium, round and flat brushes with strokes up to 1 cm wide; palette knife.

Palette

Analysis indicates the presence of the following pigments: lead white, cobalt blue, emerald green, bone black, vermilion, red lake, iron oxide red and/or yellow, zinc yellow, cadmium yellow, and possibly Naples yellow and chrome yellow.

The observation of a characteristic salmon-colored fluorescence under UV light indicates that Renoir used fluorescing red lake on some of the red and purple fruits, as well as in the underdrawing and limited portions of the background (fig. 14.22).

Binding media

Oil (estimated).

Surface Finish

Varnish layer/media

The current synthetic varnish was applied during the 1968 treatment and replaced an oil-resin varnish. There are residues of this earlier varnish around areas of impasto (especially the signature). In 1968, residues of an even older, more discolored resin varnish were noted; it is unclear whether this early varnish was original to the painting (see Conservation History).

Conservation History

The painting’s first documented treatment occurred in 1967 and included consolidation of flaking paint and retouching. A more substantial treatment was undertaken the following year, and pretreatment notes indicate that the painting was already aqueously lined, with a natural-resin varnish and evidence of older, more discolored varnish in areas of impasto. As the work seemed in stable structural condition, this treatment was primarily aesthetic and included removal of grime and discolored varnishes. Losses were inpainted with methacrylate paints, and the painting was given a synthetic varnish (an isolating layer of polyvinyl acetate [PVA] AYAA, followed by methacrylate resin L-46, inpainting, and a final coat of AYAA).

Condition Summary

The painting is in good condition, with a stable aqueous lining, and appears to retain its original stretcher. There are slight corner draws, but the work is well tensioned and otherwise planar. The canvas has discolored with age and saturation of the lining material, causing the tacking margins and exposed thread tops to appear much darker. Past cleaning and treatment have also exacerbated the abrasion and visibility of the thread tops in areas of exposed ground. There are a few local paint losses, and there is abrasion on the lower left. The stretcher was slightly keyed out and the perimeter expanded during the 1968 treatment; these edges have largely been retouched. This retouching is discolored but largely covered by the frame. The synthetic varnish imparts some saturation and an even gloss to the work and further saturates areas of exposed bare canvas.

Kelly Keegan

Frame

Current frame (probably installed mid-1960s): The frame is not original to the painting. It is an American (APF Master Frame Makers, New York), mid-twentieth-century, Louis XV reproduction, gilt scotia frame with swept, pointed sides; carved foliate ornament, foliate center cartouches, and foliate-and-acanthus corner cartouches; and a gilt fillet liner. The the frame has water and oil gilding over red bole on gesso, heavily rubbed and toned with a casein or gouache umber wash, gray overwash, and dark flecking. The high points of the ornament are particularly distressed. The ornament and sight molding are selectively burnished. The basswood molding is mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, is ovolo with leaf-tip outer molding; scotia side; scotia face with swept, pointed sides and carved foliate ornament, foliate center cartouches, and foliate-and-anthemion corner cartouches, quirked at the frieze; sanded front frieze; ogee sight molding with acanthus leaves on a recut bed; and an independent flat fillet liner with beveled sight edge (fig. 14.23).

Previous frame (installed by 1933, removed mid-1960s): The painting was previously housed in a late-nineteenth–early-twentieth-century, Louis XIV reproduction, ogee frame with alternating fleur-de-lis and pendent bellflower ornament bracketed by foliate scrolls and cabling and anthemion corner cartouches. The frame had water and oil gilding over gesso and cast plaster. The sides were burnished and the ornament was selectively burnished. The molding was mitered and nailed. The molding, from the perimeter to the interior, was ovolo with leaf-tip ornament; scotia side; convex face with alternating fleur-de-lis and pendent bellflower ornament bracketed by foliate scrolls and cabling and anthemia corner cartouches; fillet; sanded frieze; ogee with leaf-tip-and-flower ornament; cove; and fillet with a cove sight edge (fig. 14.24).

Kirk Vuillemot

Provenance

Probably sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel, Paris, May 23, 1882, for 600 francs.

Possibly sold at Moore’s Art Galleries, New York, May 6, 1887, lot 92.

Acquired by Durand-Ruel, New York, by Nov. 14, 1908.

Sold by Durand-Ruel, New York, to Martin A. Ryerson, Chicago, Dec. 18, 1915, for $10,200.

Bequeathed by Martin A. Ryerson (died 1932), Chicago, to the Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.

Exhibition History

Probably Paris, Durand-Ruel, Exposition des oeuvres de P.-A. Renoir, Apr. 1–25, 1883, cat. 27, as Nature morte (Naples).

Possibly New York, National Academy of Design, Celebrated Paintings by Great French Masters, May 25–June 30, 1887, not in cat.

Possibly New York, Durand-Ruel, Paintings by Claude Monet and Pierre August Renoir, Apr. 1900, cat. 29, as Fruits du midi.

New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings by Pierre Auguste Renoir, Nov. 14–Dec. 5, 1908, cat. 8, as Fruits du midi, 1881.

Possibly New York, Durand-Ruel, Exhibition of Paintings Representing Still Life and Flowers by Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, André d’Espagnat, Dec. 20, 1913–Jan. 8, 1914, cat. 14, as Fruits du midi.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, May 23–Nov. 1, 1933, cat. 343. (fig. 14.25)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Manet and Renoir, Nov. 29, 1933–Jan. 1, 1934, no cat. no.

Art Institute of Chicago, “A Century of Progress”: Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture for 1934, June 1–Oct. 31, 1934, cat. 232.

Cambridge, Mass., Fogg Art Museum, Loan Exhibition of Paintings of Still Life, Apr. 28–May 24, 1947, no cat.

New York, Acquavella Galleries, Four Masters of Impressionism, Oct. 24–Nov. 30, 1968, cat. 29 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, Feb. 3–Apr. 1, 1973, cat. 36 (ill.).

Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), State Hermitage Museum, Ot Delakrua do Matissa: Shedevry frantsuzskoi zhivopisi XIX–nachala XX veka, iz Muzeia Metropoliten v N’iu-Iorke i Khudozhestvennogo Instituta v Chikago [From Delacroix to Matisse: Great masterpieces of French painting of the nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago], Mar. 15–May 16, 1988, cat. 22 (ill.); Moscow, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, May 30–July 30, 1988.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago’s Dream, a World’s Treasure: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1893–1993, Nov. 1, 1993–Jan. 9, 1994, not in cat.

Selected References

Possibly Durand-Ruel, Paris, Catalogue de l’exposition des oeuvres de P.-A. Renoir, exh. cat. (Pillet & Dumoulin, 1883), p. 12, cat. 27.

Possibly Edmond Jacques [Edmond Bazire], “Beaux-arts: Exposition de M. P.-A. Renoir,” L’intransigeant, Apr. 11, 1883, p. 2.

Possibly Paul Gilbert, “Exposition de M. P.-A. Renoir,” Journal des artistes, Apr. 13, 1883, p. 1.

Possibly Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings by Claude Monet and Pierre Auguste Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1900), no. 29.

Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings by Pierre Auguste Renoir, exh. cat. (Durand-Ruel, New York, 1908), no. 8.

Possibly Durand-Ruel, New York, Exhibition of Paintings Representing Still Life and Flowers by Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, André d’Espagnat, exh. cat. (Durand Ruel, New York, [1913]), cat. 14.

Art Institute of Chicago, A Guide to the Paintings in the Permanent Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1925), p. 162, cat. 2155.

M. C., “Renoirs in the Institute (Continued),” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 19, 4 (Apr. 1925), pp. 47, 49 (ill.).

Ambroise Vollard, Renoir: An Intimate Record, trans. Harold L. Van Doren and Randolph T. Weaver (Knopf, 1925), p. 240.

Julius Meier-Graefe, Renoir (Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1929), p. 153, no. 134.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture; Lent from American Collections, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1933), p. 49, cat. 343.

Daniel Catton Rich, “The Paintings of Martin A. Ryerson,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 27, 1 (Jan. 1933), p. 9.

Daniel Catton Rich, “Französische Impressionisten im Art Institute zu Chicago,” Pantheon: Monatsschrift für Freunde und Sammler der Kunst 11, 3 (Mar. 1933), p. 78. Translated by C. C. H. Dreschel as “French Impressionists in the Art Institute of Chicago,” Pantheon/Cicerone (Mar. 1933), p. 18.

Pennsylvania Museum of Art, “Manet and Renoir,” Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin 29, 158 (Dec. 1933), p. 19.

Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, 1934, ed. Daniel Catton Rich, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1934), p. 39, cat. 232.

Albert C. Barnes and Violette de Mazia, The Art of Renoir (Minton, Balch, 1935), pp. 77; 79; 88; 132; 453, no. 115.

Henry McBride, “The Renoirs of America: An Appreciation of the Metropolitan Museum’s Exhibition,” Art News 35, 31 (May 1, 1937), p. 60.

Rosamund Frost, Pierre August Renoir, Hyperion Art Monographs, ed. Aimèe Crane (Hyperion/Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1944), p. 43 (ill.).

“Chicago Perfects Its Renoir Group,” Art News 44, 16, pt. 1 (Dec. 1–14, 1945), p. 18 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, An Illustrated Guide to the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1945), p. 36.

Walter Pach, Pierre-August Renoir, Library of Great Painters (Abrams, 1950), pp. 72–73 (ill.). Translated as Auguste Renoir: Leben und Werk (M. DuMont Schauberg, 1976), pp. 109, pl. 13; 116; 168.

Dorothy Bridaham, Renoir in the Art Institute of Chicago (Conzett & Huber, 1954), pl. 6.

Michel Drucker, Renoir (Pierre Tisné, 1955), pl. 74; p. 154.

Bruno F. Schneider, Renoir (Safari, [1957]), pp. 61 (ill.), 68, 86. Translated into English by Desmond and Camille Clayton as Renoir (Crown, 1978), pp. 61 (ill.), 68, 86.

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Picture Collection (Art Institute of Chicago, 1961), p. 397.

Acquavella Galleries, Four Master of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Acquavella Galleries, 1968), cat. 29 (ill.).

Barbara Ehrlich White, “Renoir’s Trip to Italy,” Art Bulletin 51, 4 (Dec. 1969), pp. 338; 339; 341; fig. 26; 346, no. 20.

Charles C. Cunningham and Satoshi Takahashi, Shikago bijutsukan [Art Institute of Chicago], Museums of the World 32 (Kodansha, 1970), pp. 52, pl. 38; 160.

Elda Fezzi, L’opera completa di Renoir: Nel periodo impressionista, 1869–1883, Classici dell’arte 59 (Rizzoli, 1972), pp. 72, pl. 56; 110, cat. 486 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Paintings by Renoir, exh. cat. (Art Institute of Chicago, 1973), pp. 100–01, cat. 36 (ill.); 210; 211.

Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et son époque: Dictionnaire international illustré, vol. 2 (Denoël, 1979), p. 178 (ill.).

Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (Abrams, 1984), p. 166.

Richard R. Brettell, French Impressionists (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1987), pp. 66–67 (detail), 69 (ill.), 119.

Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), State Hermitage Museum, Ot Delakrua do Matissa: Shedevry frantsuzskoi zhivopisi XIX–nachala XX veka, iz Muzeia Metropoliten v N’iu-Iorke i Khudozhestvennogo Instituta v Chikago [From Delacroix to Matisse: Great masterpieces of French painting of the nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago], exh. cat. (Avrora, 1988), cat. 22 (ill.).

Sophie Monneret, Renoir, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1989), p. 98, no. 1 (ill.).

Gilles Plazy, Cézanne, Profils de l’art (Chêne, 1991), p. 100, no. 2 (ill.).

Lesley Stevenson, Renoir (Bison, 1991), p. 119 (ill.).

Richard Verdi, Cézanne (Thames & Hudson, 1992), pp. 11, ill. 5; 211.

James Yood, Feasting: A Celebration of Food in Art; Paintings from the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago/Universe, 1992), pp. 56–57, pl. 19 (ill. and detail).

Art Institute of Chicago, Treasures of 19th- and 20th-Century Painting: The Art Institute of Chicago, with an introduction by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Abbeville, 1993), p. 85 (ill.).

Gerhard Gruitrooy, Renoir: A Master of Impressionism (Todtri, 1994), pp. 56–57 (detail), 65 (ill.).

Natalia Brodskaïa, Auguste Renoir: He Made Colour Sing, trans. Paul Williams, Great Painters (Parkstone/Aurora Art, 1996), pp. 134–135, no. 29.

Francesca Castellani, Pierre-Auguste Renoir: La vita e l’opera (Mondadori, 1996), p. 156 (ill.).

Douglas W. Druick, Renoir, Artists in Focus (Art Institute of Chicago/Abrams, 1997), pp. 53 (detail); 54–55; 57; 94, pl. 13; 110.

Pamela Todd, The Impressionists’ Table: A Celebration of Regional French Food through the Palettes of the Great Impressionists (Pavilion, 1997), pp. 156 (ill.), 192.

Art Institute of Chicago, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the Art Institute of Chicago, selected by James N. Wood (Art Institute of Chicago/Hudson Hills, 2000), p. 65 (ill.).

Gilles Néret, Renoir: Painter of Happiness, 1841–1919, trans. Josephine Bacon (Taschen, 2001), p. 146 (ill.)

Katsumi Miyazaki, “The Formal Elements of Renoir’s Art and His Relationship with Cézanne,” in Bridgestone Museum of Art and Nagoya City Art Museum, Renoir: From Outsider to Old Master, 1870–1892, trans. Yumiko Yamazaki, exh. cat. (Bridgestone Museum of Art/Nagoya City Art Museum/Chunichi Shimbun, 2001), pp. 183, fig. 64; 184; 237, fig. 64; 238.

Bruce Weber, The Heart of the Matter: The Still Lifes of Marsden Hartley, exh. cat. (Berry-Hill Galleries, 2003), p. 15, fig. 6.

Aviva Burnstock, Klaas Jan van den Berg, and John House, “Painting Techniques of Pierre-Auguste Renoir: 1868–1919,” Art Matters: Netherlandish Technical Studies in Art 3 (2005), p. 52.

Kyoko Kagawa, Runowaru [Pierre-Auguste Renoir], Seiyo Kaiga no Kyosho [Great masters of Western art] 4 (Shogakukan, 2006), p. 97 (ill.).

Guy-Patrice Dauberville and Michel Dauberville, with the collaboration of Camille Frémontier-Murphy, Renoir: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, pastels, dessins, et aquarelles, vol. 1, 1858–1881 (Bernheim-Jeune, 2007), p. 135, cat. 44 (ill.).

John House, The Genius of Renoir: Paintings from the Clark, with an essay by James A. Ganz, exh. cat. (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute/Museo Nacional del Prado/Yale University Press, 2010), p. 96.

Other Documentation

Documentation from the Durand-Ruel Archives

Inventory number

Probably stock Durand-Ruel, Paris, 2394

Inventory number

Stock Durand-Ruel, New York, 115

Photograph number

Photo Durand-Ruel, New York, A915

Other Documents

Label (fig. 14.26)

Inscription (fig. 14.27)

Purchase Receipt

Labels and Inscriptions

Undated

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script on red-and-white label

Content: 15 / 605 (fig. 14.28)

Number

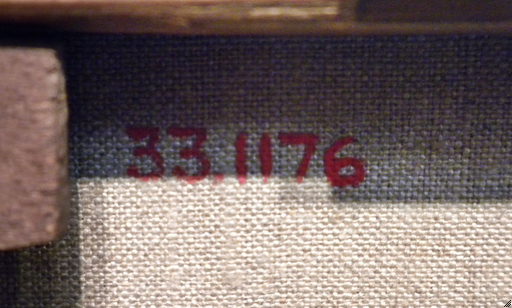

Location: canvas verso (lining canvas)

Method: handwritten script (red paint)

Content: 33.1176 (fig. 14.29)

Pre-1980

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: black ovular stamp

Content: 15 w (fig. 14.30)

Inscription

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: D.R.N.Y / 115 (fig. 14.27)

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script on printed label

Content: Renoir / No. 115 / Fruits du / midi 1881 / mabbb (fig. 14.26)

Post-1980

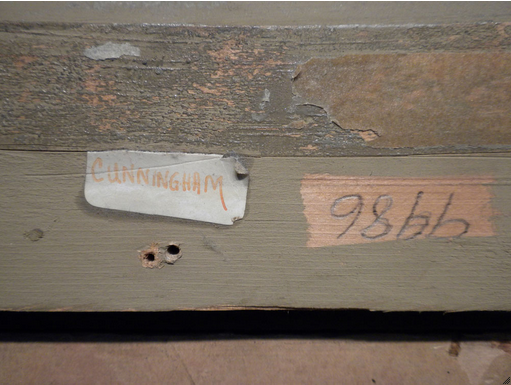

Number

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: 9986 [upside down] (fig. 14.31)

Label

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script (red) on white label

Content: CUNNINGHAM (fig. 14.31)

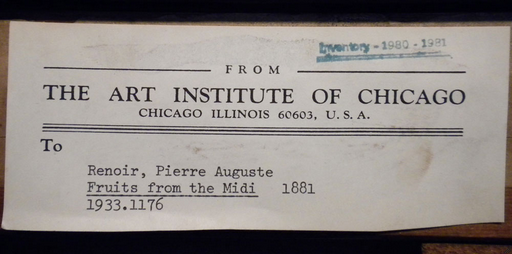

Label

Location: stretcher

Method: printed and typed label with blue stamp

Content: [blue stamp] Inventory—1980–1981 / FROM / THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / CHICAGO ILLINOIS 60603, U. S. A. / To / Renoir, Pierre Auguste / Fruits from the Midi 1881 / 1933.1176 (fig. 14.32)

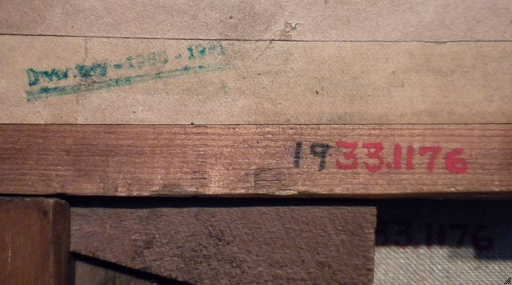

Stamp

Location: stretcher

Method: blue stamp

Content: Inventory—1980–1981 (fig. 14.33)

Number

Location: stretcher

Method: handwritten script

Content: 1933.1176 (fig. 14.33)

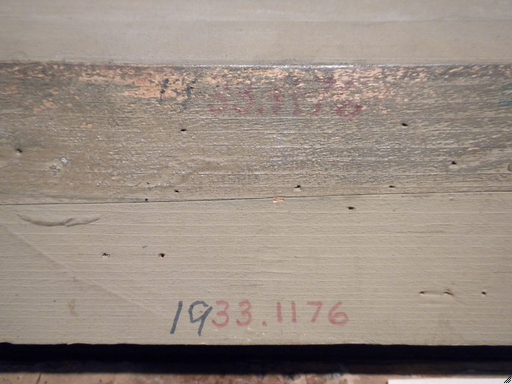

Number

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script

Content: 1933.1176 (fig. 14.34)

Number

Location: frame verso

Method: handwritten script

Content: 33.1176 (fig. 14.34)

Label

Location: backing board

Method: printed and typed label

Content: THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO / artist Auguste Renoir / title Fruits from the Midi. 1881 / medium oil on canvas / credit M/M Martin A. Ryerson Collection / acct. # 1933.1176 (fig. 14.35)

Inscription

Location: backing board

Method: handwritten script (graphite)

Content: Fruits 33.1176 (fig. 14.35)

Examination and Analysis Techniques

X-radiography

Westinghouse X-ray unit, scanned on Epson Expressions 10000XL flatbed scanner. Scans were digitally composited by Robert G. Erdmann, University of Arizona.

Infrared Reflectography

Inframetrics Infracam with 1.5–1.73 µm filter; Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm); Goodrich/Sensors Unlimited SU640SDV-1.7RT with H filter (1.1–1.4 µm) and J filter (1.5–1.7 µm).

Transmitted Infrared

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-Nite 1000B/2 mm filter (1.0–1.1 µm).

Visible Light

Natural-light, raking-light, and transmitted-light overalls and macrophotography: Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter.

Ultraviolet

Fujifilm S5 Pro with X-NiteCC1 filter and Kodak Wratten 2E filter.

High-Resolution Visible Light (and Ultraviolet)

Sinar P3 camera with Sinarback eVolution 75 H (X-NiteCC1 filter, Kodak Wratten 2E filter).

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Sample and cross-sectional analysis were performed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 research microscope equipped with reflected light/UV fluorescence and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. Types of illumination used: darkfield, brightfield, differential interference contrast (DIC), and UV. In situ photomicrographs were taken with a Wild Heerbrugg M7A StereoZoom microscope fitted with an Olympus DP71 microscope digital camera.

X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

Several spots on the painting were analyzed in situ with a Bruker/Keymaster TRACeR III-V with rhodium tube.

Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM)

Zeiss Universal research microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDX)

Cross sections were analyzed after carbon coating with a Hitachi S-3400N-II VPSEM with an Oxford EDS and a Hitachi solid-state BSE detector. Analysis was performed at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental (NUANCE) Center, Electron Probe Instrumentation Center (EPIC) facility.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

A Jobin Yvon Horiba LabRAM 300 confocal Raman microscope was used, equipped with an Andor multichannel, Peltier-cooled, open-electrode charge-coupled device detector (Andor DV420-OE322; 1024×256), an Olympus BXFM open microscope frame, a holographic notch filter, and an 1,800-grooves/mm dispersive grating.

The excitation line of an air-cooled, frequency-doubled, He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) was focused through a 20× objective onto the samples, and Raman scattering was back collected through the same microscope objective. Power at the samples was kept very low (never exceeding a few mW) by a series of neutral density filters in order to avoid any thermal damage.

Automated Thread Counting

Thread count and weave information were determined by Thread Count Automation Project software.

Image Registration Software

Overlay images were registered using a novel image-based algorithm developed by Damon M. Conover (GW), Dr. John K. Delaney (GW, NGA), and Murray H. Loew (GW) of the George Washington University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Image Inventory

The image inventory compiles records of all known images of the artwork on file in the Conservation Department, the Imaging Department, and the Department of Medieval to Modern European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago (fig. 14.36).