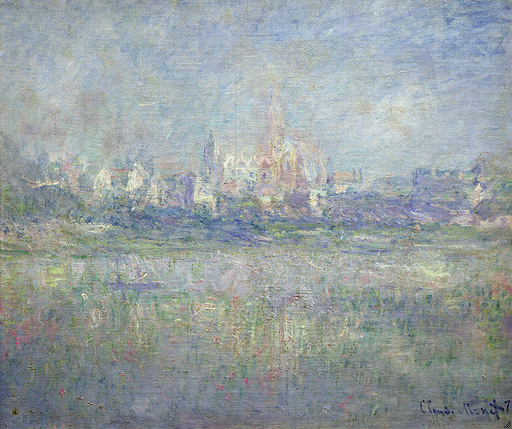

Cat. 42

Vétheuil

1901

Oil on canvas; 90.2 × 93.4 cm (35 1/2 × 36 3/4 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1901 (lower left, in light orange-red paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection, 1933.447

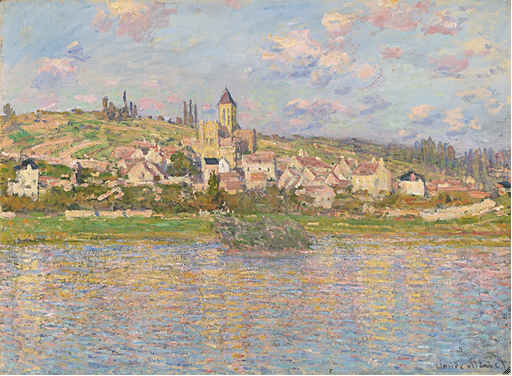

Cat. 43

Vétheuil

1901

Oil on canvas; 90 × 93 cm (36 7/16 × 36 5/8 in.)

Signed and dated: Claude Monet 1901 (lower left, in pale-pink paint)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1161

Return to Vétheuil

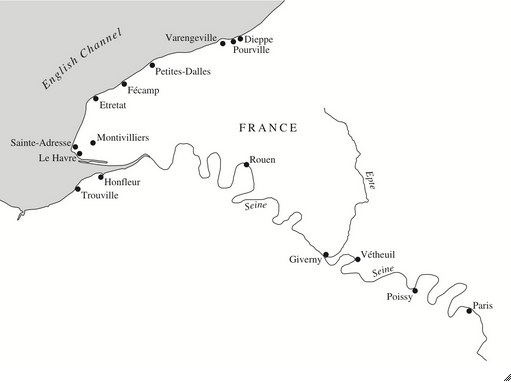

In the summer of 1901 Monet rented a modest house in Lavacourt, located just a few miles from his Giverny property, on the Seine across the river from Vétheuil (fig. 1). It was from the balcony of this rented home that Monet began fifteen paintings of Vétheuil. As exemplified by the two versions in the Art Institute’s collection—one painted in midday and one at sunset—Monet’s goal during this campaign was to depict the same, restricted view of the riverbank and the town’s commanding Church of Notre Dame, but in the differing lights of day.

Monet’s diversion up the Seine that summer—which took place soon after he returned home from his third and final trip to London to paint Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, and the Houses of Parliament (see cats. 38–41)—was likely motivated by several factors. Paul Tucker has suggested that Monet found it to be a good alternative to painting his water garden, which was soon to undergo major renovation. In May 1901, Monet had acquired additional land near his Giverny property in order to enlarge his water lily pond, which he initially had built in fall 1893; by late February or early March 1902, Monet had more than tripled its size and had added a miniature island and four flat footbridges. It has been proposed that the extreme heat of Giverny that summer also may have contributed to Monet’s daily visits to his secondary home and studio in Lavacourt. Feeling guilty that he had not sent news in so long, Monet wrote to his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, in July about his inability to work in the intense temperatures: “Considering the heat, it is impossible to work in the studio and outside. It is a year lost. I long for rain and even the cold, so I can get back to work,” Monet explained.

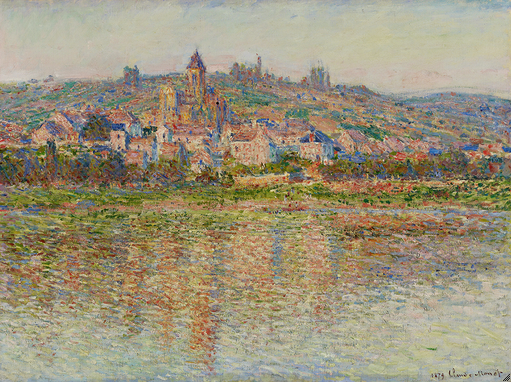

In addition to a circumstantial decision necessitated by imminent renovation, Monet’s Vétheuil paintings relate to the pursuits he had been exploring in his recent series. In the 1890s, Monet executed serial works of art dedicated to the mutable lighting and atmospheric effects on specific subjects and places—including the Stacks (see cats. 27–33), sites along the coast of Normandy (see cat. 35), the banks of the Seine (see cat. 36), and London (see cats. 38–41)—that he had treated earlier in his career; according to John House, it was “his recurrent wish to return to sites that he had painted many years before, as if to test out his art and his eye against his previous paintings and memories.” Vétheuil was indeed a location that Monet had painted before, and it was imbued with personal significance, perhaps more than any other spot to which Monet returned. It was in Vétheuil in late summer 1878 that Monet had moved with his family—his first wife Camille and their sons Jean and Michel, the latter then only a few months old—to share a house with Ernest Hoschedé (an important patron of Monet and the Impressionists until his recent bankruptcy), along with his wife, Alice, and their six children. It was also here that Camille died and was buried in 1879 and that Monet’s relationship with Alice—who would officially become his second wife in 1892—would develop. Until the end of 1881 when Monet, Alice, and their families moved to Poissy, the artist frequently painted Vétheuil, its main roadway, its church and banks, the surrounding landscape, and his own personal garden there, under varying seasons and weather conditions, and often from his studio boat. A few of his numerous canvases of the village depict nearly the same scene as the one featured in the Art Institute’s paintings twenty years later—in varying weather conditions (fig. 2 [W507], fig. 3 [W518], fig. 4 [W533], and fig. 5 [W534]).

Vétheuil: Past and Present

A notable difference between Monet’s paintings of Vétheuil from 1901 and those from around 1879 is the format of the canvas used. While the earlier pictures are typically oriented horizontally—the convention for landscapes—Monet’s paintings of Vétheuil from 1901 are all nearly square, a format he had also used in his series Mornings on the Seine (fig. 6, [cat. 36]) and Water Lily Pond (fig. 7, [cat. 37]), works that were executed closer in time. The fact that all fifteen paintings of Vétheuil from 1901 were executed on almost square canvases, which were not a standard format, indicates that Monet probably had to specially request them from his canvas supplier. In the 1901 Vétheuil works as well as his Mornings on the Seine and Water Lily Pond paintings, there is a tripartite division of space into zones of water, land, and sky, with the water—and the effect of light reflecting off of it—given primary importance. Monet seems less preoccupied, however, with the point where water converges with land or air at the horizon in the Vétheuil paintings than is evident in Branch of the Seine near Giverny (fig. 6) and Water Lily Pond (fig. 7). Despite the fact that the two examples in the Art Institute feature strong reflections of Vétheuil in the water, Monet does not explore the same kind of smooth merging of land and reflection. Some of the 1901 Vétheuil paintings, in fact, do not feature reflections of the town in the water at all, and five include indications of land on the bank of the Lavacourt side of the Seine, further breaking up any kind of smooth transition between reality and reflection (see, e.g., fig. 8 [W1636]).

Another point of interest involves the inclusion of human presence in Vétheuil’s landscape. Some of the paintings from the earlier period when Monet resided in Vétheuil, including The Church at Vétheuil (fig. 9 [W531]), show the hustle and bustle of daily existence around the village. While Monet consistently represented Vétheuil’s built environment in his paintings from 1901, he downplayed the activities of human life, even though, ironically enough, he traveled to the site—often with family and friends in tow—almost every afternoon in the Panhard-Levassor automobile that he had purchased in December 1900. Only a few of the 1901 paintings are populated, and only with passengers in single, isolated, modest-size boats. Although Monet incorporated active, flickering brushstrokes in these canvases, the lack of a human component makes them appear eerily calm and empty. Back in the vicinity of the town where Monet and Camille had spent the final years of their life together, the artist may well have been moved by old memories, which found their expression in the restrained quiet of these pictures.

Trouble in Vétheuil?

Monet possibly hoped that his break from Giverny would be productive and beneficial after the considerable difficulty he had experienced finishing the paintings in his London series that he had begun in 1899. As Monet exasperatedly complained to Alice shortly before he returned to Giverny from his final trip to London: “It’s almost impossible to continue work on a painting. I make alterations to paintings and often ones that were passable are worse for the change. No one would ever guess the trouble I’d gone through to end up with so little.” But Monet complained that the Vétheuil works, too, caused him more trouble than he anticipated. Writing to his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, that October, he expressed: “I have undertaken a series of Views of Vétheuil that I thought I would be able to finish quickly and that have taken me all summer, so all of the other things [I had been working on] remain in progress.”

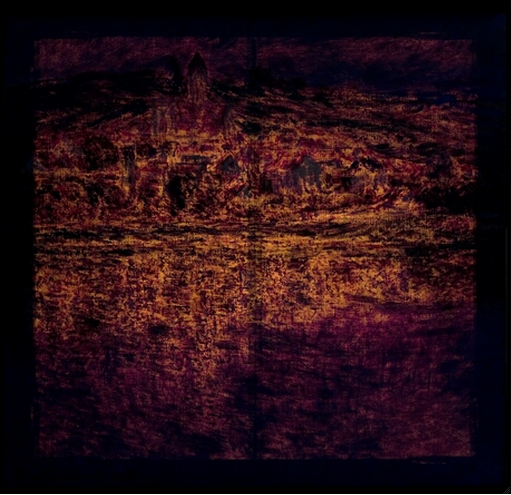

Monet’s explanation that he had to put aside other canvases in order to focus on the Vétheuil paintings seems curious, however, since technical examination of the two versions of Vétheuil in the Art Institute’s collection suggest that these paintings were by no means as labor intensive as Monet made them out to be. While both were completed in more than one session—as indicated by the presence of wet-over-dry paint application—neither exhibit any major compositional changes (see Technical Report). Furthermore, when both works are examined with transmitted light, they attest to the fact that Monet applied paint rather thinly, leaving areas of the ground layer and canvas texture exposed (fig. 10 and fig. 11), suggesting that he worked quickly and confidently in each session without having to go back and make extensive “alterations,” as necessitated in his London series.

Perhaps it was the psychological toll of revisiting Vétheuil, and the attendant memories of his deceased first wife, that made the 1901 Vétheuil paintings take longer than Monet expected. But considering that Durand-Ruel was clamoring for the eleven London canvases he had reserved from Monet back in November 1899, it is possible that Monet fabricated this excuse to justify why he was unable to hand over any of the London works owed to the dealer. In the same letter from October in which Monet complained to Durand-Ruel about the unexpected extra time needed for the Vétheuil views, Monet concluded by referring to the delinquent paintings: “Finally, next week I will take care of finishing some of the old things that you chose and will send them to you soon.” Indeed, the following month Monet was finally able to give four London paintings to Durand-Ruel, but no more would enter the dealer’s hands until their exhibition at the gallery in 1904. Although he began the 1901 Vétheuil works later than the London series, Monet relinquished them more easily. Monet was able to work up a number of them—probably including the two in the Art Institute’s collection—into a finished state by February 1902, when he included them in an exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s rival gallery Bernheim-Jeune.

Jill Shaw